Introduction

Lower urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a significant health concern globally, impacting individuals of all ages and backgrounds, particularly in outpatient clinics [

1]. These infections, often caused by bacteria, sometimes antibiotic-resistant due to recurrent or suboptimal treatments, can result in discomfort, pain, and, if left untreated, severe complications such as kidney infections [

2,

3]. Among those most vulnerable to UTIs are individuals diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, a population particularly susceptible to these infections. Diabetes mellitus, characterized by elevated blood glucose levels resulting from impaired insulin production or response, has emerged as a major public health challenge [

2,

3,

4]. As of 2019, an estimated 463 million people worldwide are affected, with numbers projected to rise steadily [

5].

The connection between diabetes and UTIs is both multifactorial and complex. Diabetes compromises the immune system, reducing the body's ability to fight infections effectively. Furthermore, the altered urinary environment in diabetic patients—often high in glucose—creates ideal conditions for bacterial growth, further increasing the likelihood of infection. Additionally, diabetes-related complications such as neuropathy and impaired bladder function can lead to urinary stasis and incomplete bladder emptying, making diabetic individuals more prone to recurrent UTIs [

1,

3,

6].

Despite increasing awareness of this relationship, there remains a significant gap in the research specifically addressing lower UTIs in diabetic patients. While studies have examined UTIs in the general population and diabetes-related complications, few have focused on the unique challenges that diabetic individuals face concerning lower UTIs. This lack of research hinders the development of targeted preventive strategies and optimized treatments for this high-risk group.

This paper seeks to fill this gap by conducting a thorough retrospective analysis of a six-year outpatient clinic study, alongside a comprehensive review of existing literature. Our aim is to clarify the mechanisms underlying the heightened susceptibility of diabetic patients to lower UTIs and to evaluate current preventive and therapeutic approaches, with a focus on their effectiveness within the diabetic population.

The discovery of the urinary microbiome has further revolutionized our understanding of UTI pathogenesis, particularly in diabetic patients [

6]. In the following sections, we will explore epidemiological trends, assess the impact of diabetes-related complications on urinary tract health, evaluate current diagnostic methods and their limitations, and investigate emerging research and interventions. Through this exploration, we hope to provide healthcare professionals and researchers with valuable insights that will drive advancements in both clinical practice and research. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of the specific risk factors and challenges associated with lower UTIs in diabetic patients will pave the way for the development of more effective, evidence-based guidelines, patient education initiatives, and innovative treatment approaches [

7,

8,

9].

Methods

This retrospective study evaluated anonymized medical records of 350 patients from January 2017 to December 2023, who were followed-up at our outpatient clinic for recurrent, uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections (L-UTIs). The cohort was divided into two groups: 155 patients with diabetes (Group A) and 195 without diabetes (Group B, control group). These patients were referred to the clinic by general practitioners for urine culture or microscopy based on recurrent L-UTI episodes.

All patients in Group A had a history of diabetes for at least five years. Uncontrolled diabetes was defined as a persistent elevation of HbA1c >7% in at least three separate clinical evaluations over a one-year period, with assessments conducted every three months. In Group A, we investigated potential factors associated with recurrent L-UTI episodes, including urine test results, the presence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) as per the ROMA criteria [

6], serum glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and blood glucose levels prior to their first visit.

For all patients who underwent antibiotic treatment based on culture results, we assessed antibiotic regimens, prophylactic treatments, and recurrence of L-UTI episodes. Positive microbiological samples were classified as Gram-negative or Gram-positive organisms, with no further subclassification.

To assess the effectiveness of treatment, we compared the frequency of L-UTI episodes before and after initiation of a treatment protocol. The treatment consisted of Rifaximin 200 mg, administered twice daily (bid) for the first seven days of each month, followed by VSL#3 (a probiotic preparation containing approximately 112 billion viable lyophilized bacteria, including four strains of

Lactobacillus and three strains of

Streptococcus salivarius subsp.

thermophilus) from the 8th to the 18th day of the month. The rationale for using a high-concentration probiotic was based on the concept of restoring microbiota, which has been previously associated with infection onset [

3,

4,

5].

Recurrent L-UTIs were defined as the occurrence of at least six episodes per year at the time of enrollment. Asymptomatic bacteriuria was identified in patients who had positive urine cultures in at least three visits within a three-month period but without any corresponding symptoms. Additionally, we evaluated comorbidities such as benign prostatic hyperplasia, cystocele, and anatomical abnormalities of the genitourinary system.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between groups were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test for categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test or the Kruskal–Wallis test. Both univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify factors associated with recurrent L-UTIs. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad software for Mac OS X.

No patients or members of the public were involved in the research, as this was a retrospective analysis of anonymized data.

Results

A total of 350 patients were included in this retrospective analysis, with 155 patients in the diabetes group (Group A) and 195 patients in the non-diabetic control group (Group B). The baseline characteristics and clinical findings are summarized in

Table 1.

The average age of patients in Group A was 58 years (±4), which was slightly older than the average age of 55 years (±3) in Group B. Both groups had a predominance of male patients, with 87 males in Group A and 76 males in Group B. The slightly younger average age in Group B suggests that lower urinary tract infections (L-UTIs) may be more prevalent among younger individuals without diabetes in this regional population. This finding could have implications for age-targeted UTI prevention strategies.

Glycemic Control and Diabetes Management

In Group A, all patients had Type 2 diabetes, and the mean HbA1c level was 7.5% (±0.4), indicating suboptimal glycemic control over the follow-up period. In contrast, Group B, consisting of non-diabetic patients, had a normal average glucose level of 88 mg/dL (±9), and HbA1c data was not applicable. Notably, 83% of diabetic patients with recurrent L-UTIs in Group A had elevated HbA1c levels, consistent with previous research linking poor glycemic control to higher infection risks, such as those seen in post- infections [

11]. This finding highlights the importance of strict glycemic management in reducing the risk of UTIs in diabetic patients.

Within Group A, 46.7% of patients required insulin therapy, while 53.3% were managed with oral hypoglycemic agents. The heterogeneity in diabetes management within Group A suggests that different diabetes treatment strategies may influence susceptibility to L-UTIs, although further analysis is required to explore the relationship between insulin use and UTI risk.

Incidence of UTIs

The overall incidence of UTIs differed significantly between the groups. Group A experienced a higher lifetime incidence of UTIs compared to Group B, with a particularly higher frequency of "1 or 2 times" UTI episodes (

Table 1). This increased predisposition to UTIs among diabetic patients underscores the role of diabetes in increasing susceptibility to infections, potentially due to factors such as impaired immune function, glycemic control, and microbiota alterations.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Microbiota

Interestingly, both Group A and Group B had a notable proportion of patients with a history of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) as defined by the ROMA criteria (

Table 1). This observation suggests that IBS-related microbiota imbalances may contribute to the development of recurrent L-UTIs, a hypothesis supported by previous studies linking altered gut microbiota to UTI risk [

7]. No significant differences were observed between groups in terms of the microbiological isolates, with both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria being equally prevalent across groups (

Table 1).

Comorbidities and Anatomical Abnormalities

A small number of patients in both groups were identified with comorbidities such as benign prostatic hypertrophy, cystocele, or anatomical malformations of the genitourinary system. These factors did not significantly affect the incidence or recurrence of L-UTIs, nor did they influence the response to treatment in either group (

Table 2).

Prophylaxis and Treatment Outcomes

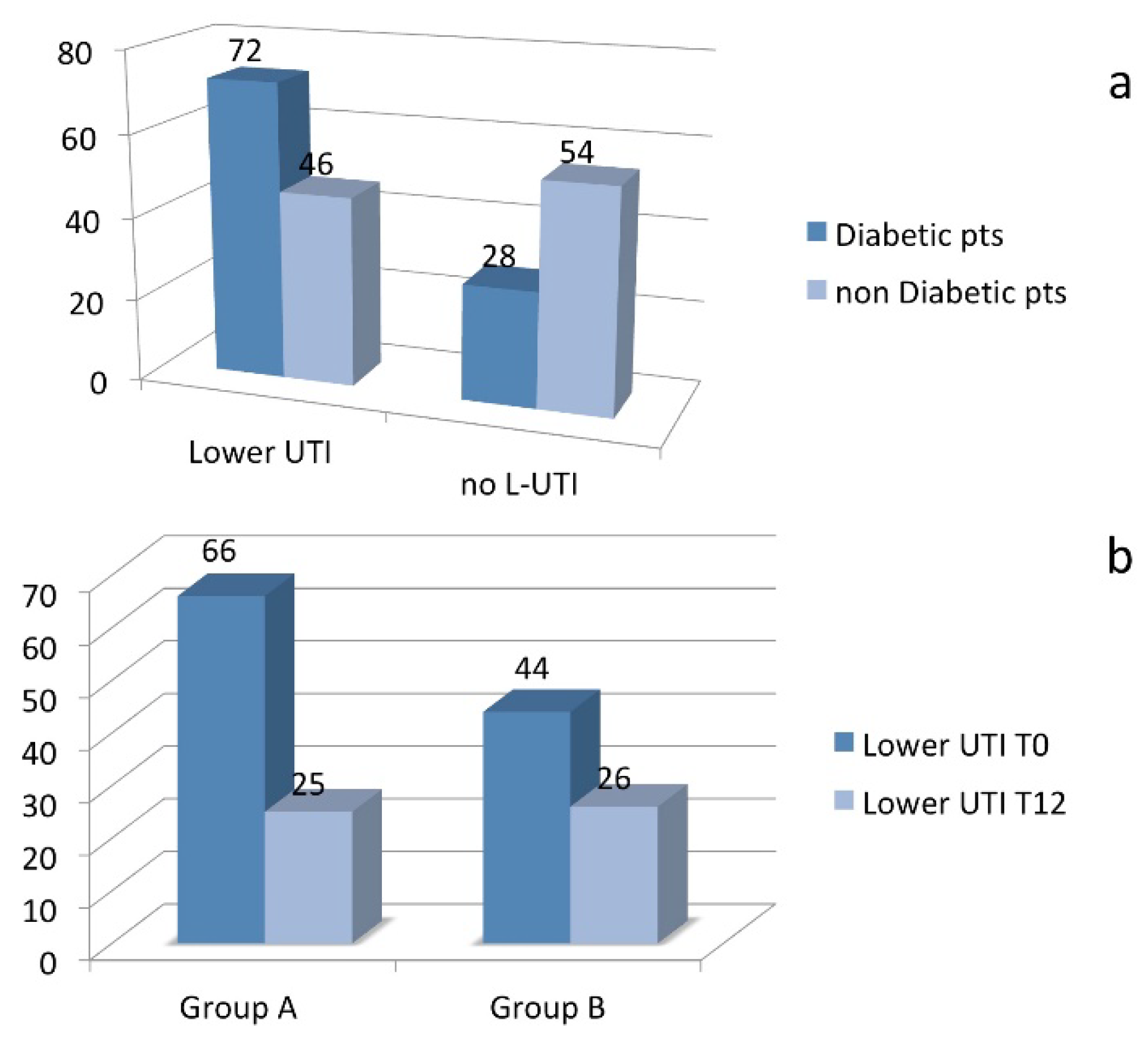

The prophylactic treatment regimen, evaluated over an 18-month follow-up period, was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the recurrence of L-UTIs in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients. In Group A, the recurrence rate decreased from 66% before treatment to 25% after treatment. Similarly, in Group B, the recurrence rate dropped from 44% to 26% following the prophylaxis regimen (

Figure 1b). The reduction in UTI recurrence was statistically significant in both groups (Mann-Whitney U test, p < 0.05). These findings highlight the efficacy of the combined antibiotic and probiotic treatment strategy in reducing recurrent L-UTIs, particularly in diabetic patients who are at a higher risk of infection.

Discussion

The increase of glycated hemoglobin seems to be a risk factor being present in higher percentage of those with recurrent lower UTI with diabetes diagnosis. This evidence clearly suggests the potential role of the reduction of oxidative burst of neutrophils in patients with uncontrolled diabetes as previously suggested [

2,

5]. Interestingly, all patients presenting lower UTI had a history of IBS and this is an independent factor according to the presence of diabetes. More interestingly we also found a significant percentage of patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria being previously treated and referred to our specialistic outpatients clinic. Those patients could be a significant challenge of public health for a antimicrobialstrategy in community settings, receiving not required antibiotics. Concerning the prophylaxis, we found that our schedule based on Rifaximin plus VSL-3 was associated to statistical significant reduction of lower UTI episodes during 18 months follow-up in both group, particularly in those with diabetes. This, again, could be related to gastrointestinal microbiota alteration occurring in all individuals, particularly in those with glucose metabolism alterations. This microbiota alteration seems to be reverted with a six months schedule treatment. These results are interesting for two main reasons, the first is related to the need to have a controlled diabetes not only to avoid the well known cardiovascular morbidity but also to reduce the risk of infections [

3,

4,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The second reason is mostly related to the fact that our prophylaxis schedule, based on local antibiotics and probiotics, may be useful to prevent lower UTI avoiding systemic antibiotics. This strategy in the Era of antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial stewardship would seem to be a valid and winning choice [

17,

18]. Further studies are required to better assess the role of probiotics in the prevention of lower UTI in a larger population and its possible role also in patients with rectal colonization and its role in microbiota restoration.

Conclusions

In summary, our findings emphasize the complex interactions between age, gender, metabolic control, and diabetes management in influencing UTI incidence. Recognizing these intricate relationships is essential for developing more effective, personalized healthcare strategies. The lower UTI incidence in Group B, associated with younger age, highlights the importance of age-specific and individualized approaches to UTI management in diabetic populations. Further research exploring the dynamics between these factors could lead to more targeted interventions in a personalized medicine, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for those at risk of UTIs within diabetic communities.

Funding

No financial to disclose.

Acknowledgments

In beloved memory of my father O. Perrella, my mentor and great clinician.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest of any authors to declare.

References

- Foxman, B. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Am J Med. 2002, 113 (Suppl. 1A), 5S–13S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilke, T.; Böttger, B.; Berg, B.; Groth, A.; Botteman, M.; Yu, S.; Fuchs, A.; Maywald, U. Healthcare Burden and Costs Associated with Urinary Tract Infections in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients: An Analysis Based on a Large Sample of 456,586 German Patients. Nephron. 2016, 132, 215–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/urological-infections/chapter/the-guideline.

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 9th ed.; Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: www.diabetesatlas.org.

- Boyko, E.J.; et al. Risk of urinary tract infection and asymptomatic bacteriuria among diabetic and nondiabetic postmenopausal women. American Journal of Epidemiology 2005, 155, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.; et al. Urinary tract infections in type 2 diabetic patients: Risk factors and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council 2015, 13, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Kang, Y.; Yu, J.; Ren, L. Human pharyngeal microbiome may play a protective role in respiratory tract infections. Genomics Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2014, 12, 144–50. [Google Scholar]

- Drossman, D.A. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 1377–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringel, Y.; Ringel-Kulka, T. The Intestinal Microbiota and Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015, 49 (Suppl. 1), S56–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, M.Y.; Lee, K.; Yoon, S.S. Protective role of gut commensal microbes against intestinal infections. J Microbiol. 2014, 52, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancienne, J.M.; Werner, B.C.; Browne, J.A. Is There a Threshold Value of Hemoglobin A1c That Predicts Risk of Infection Following Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2017, 32, S236–S240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.; Williams, J.; Johnson, C. Complications of Untreated Urinary Tract Infections: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 2017, 49, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, K.; Hooton, T.M.; Naber, K.G.; et al. International Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis and Pyelonephritis in Women: A 2010 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2011, 52, e103–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronald, A. The etiology of urinary tract infection: traditional and emerging pathogens. The American Journal of Medicine 2002, 113, 14S–19S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolle, L.E. Urinary tract infections in patients with diabetes. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2005, 7, 324–329. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, L.M.A.J.; et al. Increased risk of common infections in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2005, 41, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitzan, O.; Elias, M.; Chazan, B.; Saliba, W. Urinary tract infections in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Review of prevalence, diagnosis, and management. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy 2015, 8, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, N.; et al. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus. The New England Journal of Medicine 1999, 341, 1906–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).