1. Introduction

As an organ distributed on the body surface, the skin plays a vital role in maintaining the integrity of the body structure, protecting the body and regulating metabolism [

1,

2,

3]. Statistically, in the United States alone, millions of people reportedly suffer skin damage,the economic losses due to skin damage exceed tens of billions of dollars every year, and this figure is expected to increase with the increase in the global population[

4] . Therefore, it is extremely important to accelerate skin wound healing, which is conducive to the proper repair of the local tissue structure and the physical and mental health of patients, while reducing the economic burden on individuals and society [

5,

6,

7].

The mechanism of skin wound healing is an extremely complex and dynamic process[

8,

9,

10], which can be divided into four stages: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [

11,

12]. At each stage, a cascade of disorders may lead to abnormal wound proliferation, scar formation, and compromised appearance or function, which may lead to delayed wound healing or even non-healing, resulting in the need for amputation or the development of life-threatening conditions. Studies have shown that the dual effects of local injury and oxidative stress give rise to excessive generation of ROS and overexpression of inflammatory factors [

13], thus affecting cell proliferation and collagen formation, especially the regeneration and repair of fibroblasts in the wound tissues, preventing the transition from inflammation to proliferation, and then causing slow wound healing. On the contrary, biomaterials with good antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity can remove excessive oxidative free radicals, reduce the continuous stimulation of inflammatory factors, and thus accelerate the healing of wound tissue.

Compared with synthetic materials, food-borne drugs are favored by researchers owing to their convenience, low research and development costs, good biocompatibility, safety, and efficacy, and no obvious toxic and side effects. In this study, curcumin is a purified compound extracted from the herb turmeric, it has attracted much attention in recent years due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties[

14,

15], and has been widely used in wound tissue regeneration[

16,

17,

18]. We took curcumin as a comparative experimental study to further verify the good antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of ginger extract (Ginger E) and its regenerative ability to promote wound healing. Ginger, as a commonly used medicine in traditional Chinese medicine, has also been proved to have good anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects[

19]. It is reported that ginger contains polyphenols[

20], flavonoids[

21], ginger polysaccharide[

22] and other biological active ingredients. In order to make full use of the above components in ginger, we prepared Ginger E as a dressing to promote wound healing, and compared its effect with curcumin. To our knowledge, no systematic comparative study of the use in wound healing has been reported.

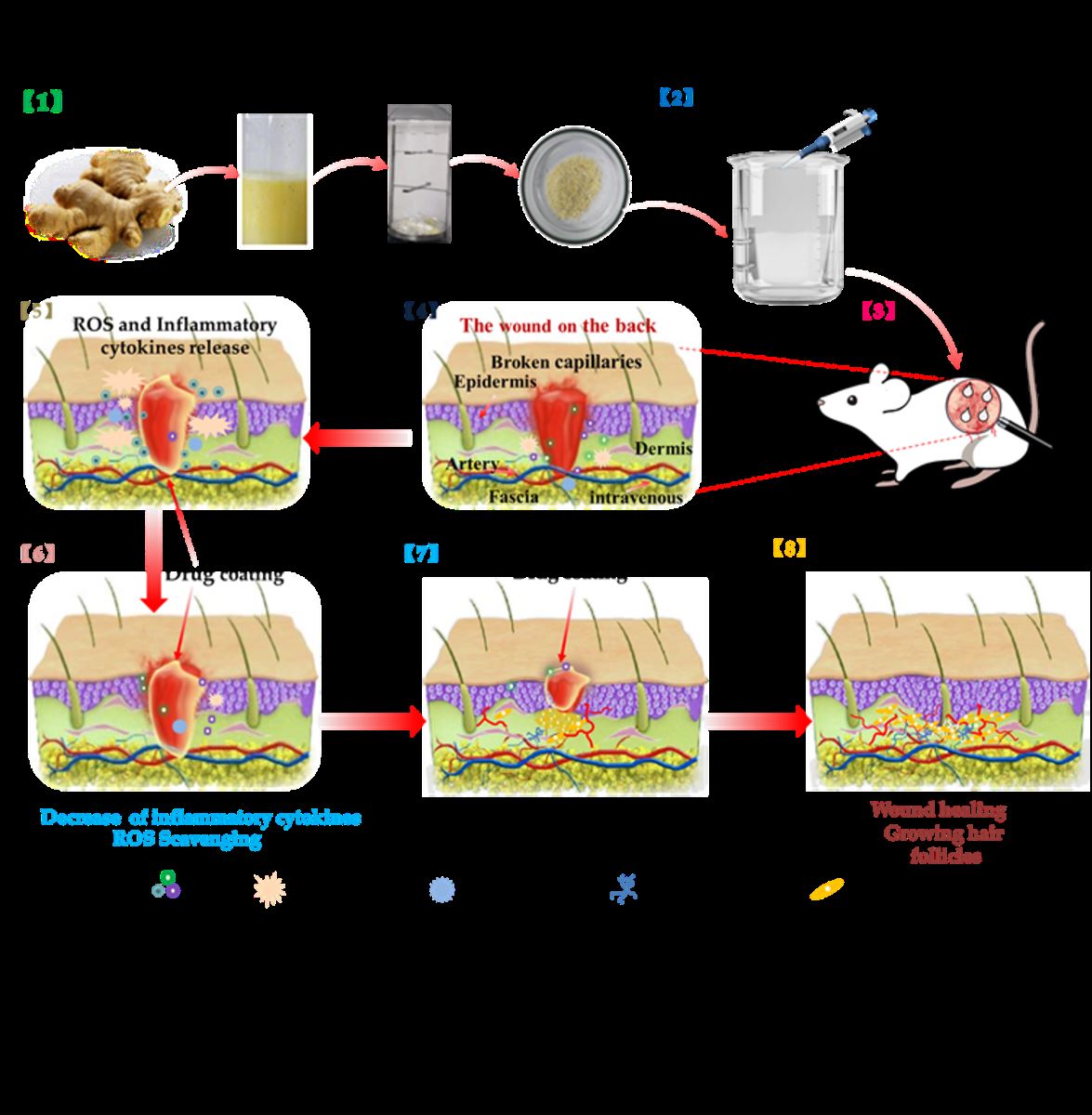

In this work, we prepared Ginger E and curcumin wound dressings (

Figure 1). They had good biocompatibility. Both of them could promote cell migration and angiogenesis, and Ginger E's effect was more obvious. At the same time, they both had excellent antioxidant effect, but Ginger E showed stronger scavenging ability of intracellular ROS. The results of the full-thickness skin defect wound model showed that Ginger E could promote the wound healing better than curcumin, it can promote the formation of new capillaries and increase the deposition of collagen, regulate the expression of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, and ultimately promote wound healing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Ginger was sourced from Guangdong province in South China, curcumin was bought from McLean Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). DPPH was purchased from Aladdin Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). PBS and DMEM (4.5g/L D-Glucose) were acquired from Sevier Biotechnology Co. Ltd (Wuhan, China). MTT, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin / streptomycin were provided by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The Live/Dead Cell staining kit and DCFH-DA were obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, PRC). The NIH3T3 cells used in the experiments were purchased from Sun Yat-sen University (Guangdong, China).

2.2. Preparation of Ginger E

Ginger was washed, cut into small pieces, and crushed in a juicer. The juice was filtered using a screen filter membrane to remove any residue. The filtrate was filtered a further three times, collected, and centrifuged on a centrifuge at a speed of 4000 r/min for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and frozen and stored overnight in a refrigerator maintained at −20°C. Subsequently, the supernatant was freeze-dried and stored for experimental use.

2.3. Cell Viability Assay

NIH3T3 cells growing in the logarithmic phase diluted by a culture medium were inoculated on a 96-pore plate, with 5000–10000 cells/pore. Each group was provided with five duplicate holes. The cells were incubated overnight at 37℃. The following day, a certain volume of DMEM were added to the NIH3T3 cell solution to create the control group, whereas the same volume of DMEM extract was added to the solution to create the Ginger E and curcumin groups. The Ginger E was diluted to different concentrations after filtration and incubated with NIH3T3 cells for 24 h; The NIH3T3 cells were incubated with different concentrations of curcumin for 24 h. Then, 1 mL MTT was added to each well and incubated for 4 h. And then, the culture medium was taken away and washed with PBS thrice. In the end, a certain volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added and the shaker was shaken for 10 min. The absorbance value at 490nm was measured to calculate the cytotoxicity of each group of materials. At the same time, the cell viability of each group was calculated; the calculation formula is:

where OD

sample indicates the light absorption value of the experimental group, OD

control represents the light absorption value of the control group.

2.4. Hemolysis Test

A hemolysis experiment was performed using Ginger E and curcumin with concentrations of 12.5 µg/mL. The specific method was as follows. A certain volume of Ginger E and curcumin were added to an SD rat erythrocyte suspension, with 0.9% sodium chloride injection was negative group, deionized water was positive group. The erythrocyte suspension was centrifuged at 1200 r/min for 2 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured by UV spectrophotometry at 545nm, and the hemolysis rate was calculated. The hemolytic ratio was calculated as:

where A

sample is the sample absorbance, A

blank is light absorption value of negative group, and A

control is light absorption value of positive group.

2.5. Live and Dead Staining

NIH3T3 cells growing in a logarithmic phase were plated in 12-well plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The old liquid was removed and Ginger E was added after centrifugal filtration. Similarly, curcumin DMEM leaching liquid was added as well. The concentrations of the Ginger E and curcumin were 12.5 µg/mL. As a control group, 1 mL of DMEM was added to each well. The cells were incubated at a constant temperature for 24 h. Subsequently, Calcein-AM/PI staining reagent was added to the solution in a dark environment. The more green fluorescence, the more viable cells. Red, on the other hand, represents dead cells. and the fluorescence images were used to qualitatively evaluate the biocompatibility of the cells.

2.6. Cell Migration Assay

NIH3T3 cells implanted in 6-well plates were adherent overnight. A 20 µL gun tip was used to score the cells perpendicular to the bottom surface of the plate hole, such that the score line intersected the marking links. The scored cells were washed thrice with PBS. The scratches were visible to the naked eye. The Ginger E and curcumin groups were diluted with medium to 12.5µg/mL. A control group with only the serum-free culture medium was created as well. The media were cultured at 37℃ in a 5% CO

2 incubator. The migration of the cells was observed from microscopic images captured in the initial condition and after 12 h and 24 h. The cell migration rate was calculated as:

where A

0 is the original scratch area and A

t is the scratch area at the measured time point.

2.7. Vascularization Experiment

10µL of matrix Gel was added to each well after thawing at 4℃. A cell suspension of HUVEC cells in a logarithmic growth phase in a 5000–10000/50 µL serum-free culture medium was incubated at 37℃ for 30 min. Subsequently, 50 µL of the cell suspension was added to each well. The cells were precipitated on the Matrix Gel, the old liquid was discarded, and Ginger E and curcumin with concentrations of 12.5 µg/mL diluted by a serum-free culture medium were added. The serum-free culture medium was also used to create a control group. Pictures were captured over regular intervals to observe and measure the formation of blood vessels.

2.8. DCFH-DA Staining

To evaluate the antioxidant effect of Ginger E, NIH3T3 cells in logarithmic phase were seeded on cell culture plates. Ginger E, curcumin, positive, and negative groups were created, each group was co-cultured with NIH3T3 cells and adherent overnight. The following day, the test materials and hydrogen peroxide were added. The concentrations of Ginger E and curcumin were 12.5 µg/mL, the positive group contained hydrogen peroxide, and the negative group did not contain any hydrogen peroxide. NIH3T3 cells incubated for 24 h were stained with the fluorescent probe DCFH-DA. Green fluorescence indicates the presence of ROS in cells, and the amount of fluorescence is proportional to the degree of oxidative damage in cells. The antioxidant activity was evaluated based on the amount of fluorescence.

2.9. Quantitative Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity

A negative group cells + DCFH-DA, positive group cells + H2O2 + DCFH-DA, and two experimental groups composed of cells + H2O2 + Ginger E and cells + H2O2 + curcumin, respectively, were created using NIH3T3 cells spread in a 6-well plate. Each group was set up in two wells, with a total of 5–10 million cells, and left to adhere overnight. The test materials were added to the aged solution, 2 mL of the Ginger E and curcumin were added per hole and 2 mL of the culture medium was added for the positive and negative control groups. The samples were incubated for 24 h. After removing the old fluid, 2 mL DMEM was added to the negative group, H2O2 (final concentration of 100 µM) and the serum culture medium were added to the Ginger E and curcumin groups, respectively, H2O2 (final concentration of 100 µM) and serum culture medium were added to the positive group. These mixtures were incubated for 24 h. Subsequently, the old solution was removed, 400 µL trypsin was added to each well, and the culture was added in a ratio of 1:2. Finally, 800 µL serum-free medium was used to stop digestion. The samples were aspirated in a flow-type centrifuge, spun at 1000 r/min, and the supernatant is sucked away. 1000 µL of DCFH-DA was added and incubated for 0.5 h at 4°C. The reaction tubes were shaken every 10 min to ensure that the cells and antibodies reacted fully. Subsequently, after the removed supernatant was discarded, PBS was added and centrifuged at 1000 r/min for 5 min, after that blot the supernatant and rinse twice. The supernatant was discarded, and this process was repeated twice. After shaking, dark flow cytometry was performed to quantitatively analyze intracellular ROS levels.

2.10. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

DPPH solution was dissolved in absolute ethanol, and Ginger E and curcumin with concentrations of 12.5 µg/mL were mixed with DPPH as the experimental groups. The negative group consisted of material and absolute ethanol, and the positive group was composed of pure water and DPPH in a ratio of 1:1, then leave it in the dark for 30 min. 200 µL of the incubated solutions was added into a 96-hole plate, with three duplicate holes. The absorption value at 517 nm was used to calculate the clearance rate.

where A

control is the negative group, A

sample is the material group, and A

blank is the positive group.

2.11. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Assay

A material solution was prepared using deionized water, 8 mmol FeSO

4 (dissolved in deionized water), 2 mmol H

2O

2 (diluted using deionized water), and 4 mmol sodium salicylate solution (dissolved in absolute alcohol). The experimental group was composed of FeSO

4 solution, the material solution, H

2O

2 solution, and sodium salicylate solution; the control group was composed of FeSO

4 added to the material solution, deionized water, and sodium salicylate solution, the background group was composed of FeSO

4 solution added to ultrapure water, H

2O

2 solution, and sodium salicylate solution. These solutions were combined in the same mixing ratio, and the mixture was vibrated and left to stand for 30 min. 200 µL of the supernatant from each well was put into a 96-well plate with 3 duplicate wells, and the absorbance value at 510 nm was read and the clearance rate was calculated.

where A

control is the negative group, A

sample is the material group, and A

blank is the positive group.

2.12. Study on the Model of Skin Wound in Rats

To study the repair ability of Ginger E on skin wound in SD rat model in vivo. The rats were randomly assigned to three groups—the Ginger E, curcumin, and control groups—with four rats in each group (n = 4). In the control group, PBS was applied to the wounds. Adult SD female rats (weighing about 200 g) were anesthetized using sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg) and their back fur was shaved. After sterilizing the skin with iodophor and alcohol, the rat was laid down on a towel, a circular wound of about 10 mm in diameter was cut on the back of rats with sterile surgical scissors. Subsequently, ginger extract and curcumin with concentrations of 12.5 µg/mL and PBS were applied to the wounds, with a single wound dose of 100 µL twice a day. The rats were euthanized after 16 days of treatment. Full-thickness skin grafts were removed from the wounds and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Immunohistochemical analyses were performed using Masson’s trichrome and HE staining.

2.13. Histological Evaluation

As discussed in Section 4.12, the skin tissue from the back wounds of the rats were removed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Subsequently, sections of approximately 5 µm were cut using the paraffin embedding technique. Masson’s trichrome and HE staining were performed to evaluate the healing and regeneration of the skin wound tissue. Col-1, IL-6, IL-10, and CD31 immunohistochemical analyses were performed on the sections. The sections were scanned using the Pannoramic P250 (3DHISTECH) and evaluated.

2.14. Statistical Analysis

The sample mean ± standard deviation was used for data statistics, and one-way analysis of variance was used for comparison between groups. GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (San Diego, CA, USA) was served as quantitative statistical analysis.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Preparation of Ginger E

Fresh ginger was cleaned, juiced, and filtered through a filter mesh. The ginger extract was weighed in accordance with the required dosage during the experiment, by applying the method of liquid extraction. The preparation process is shown in

Figure 1 [

1].

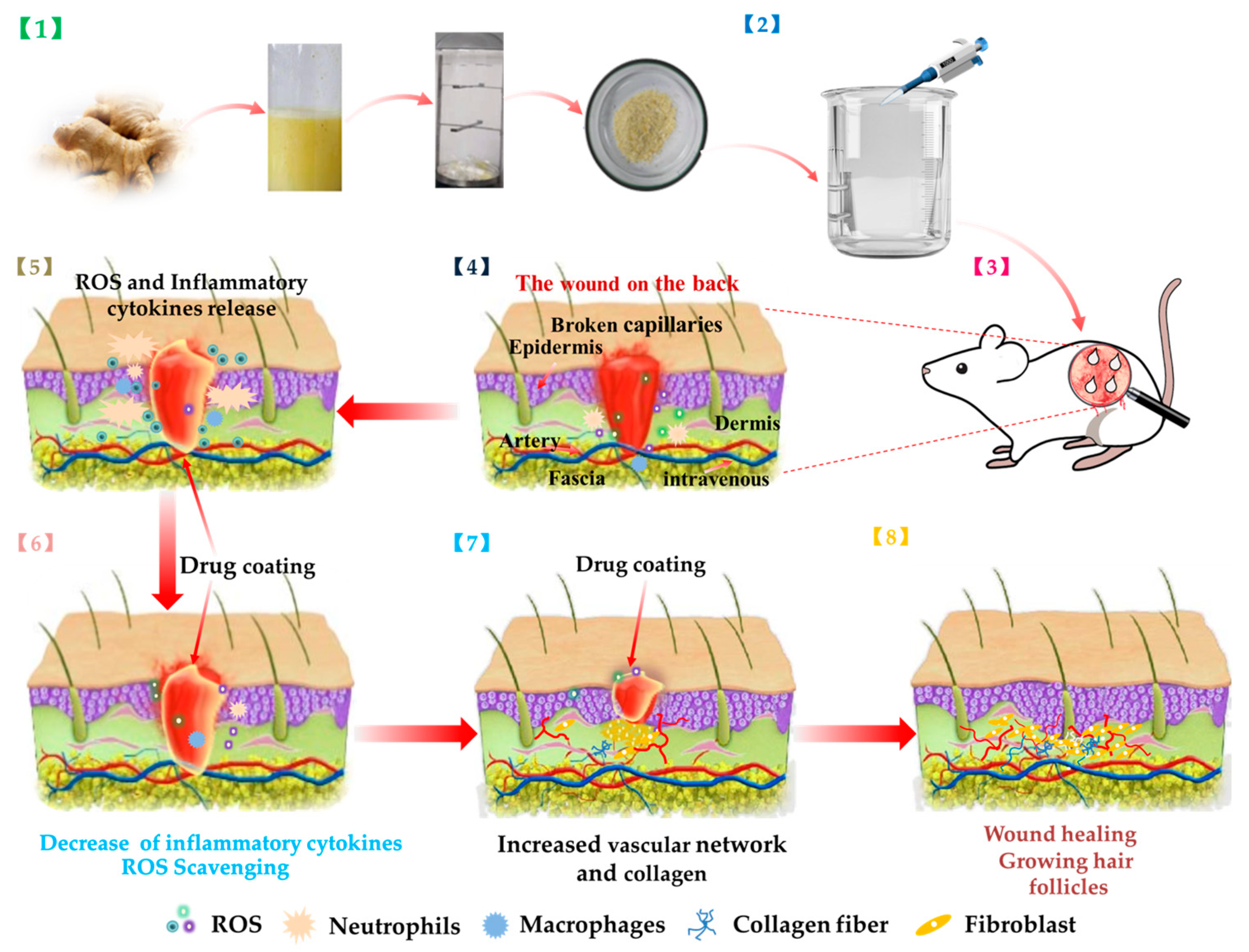

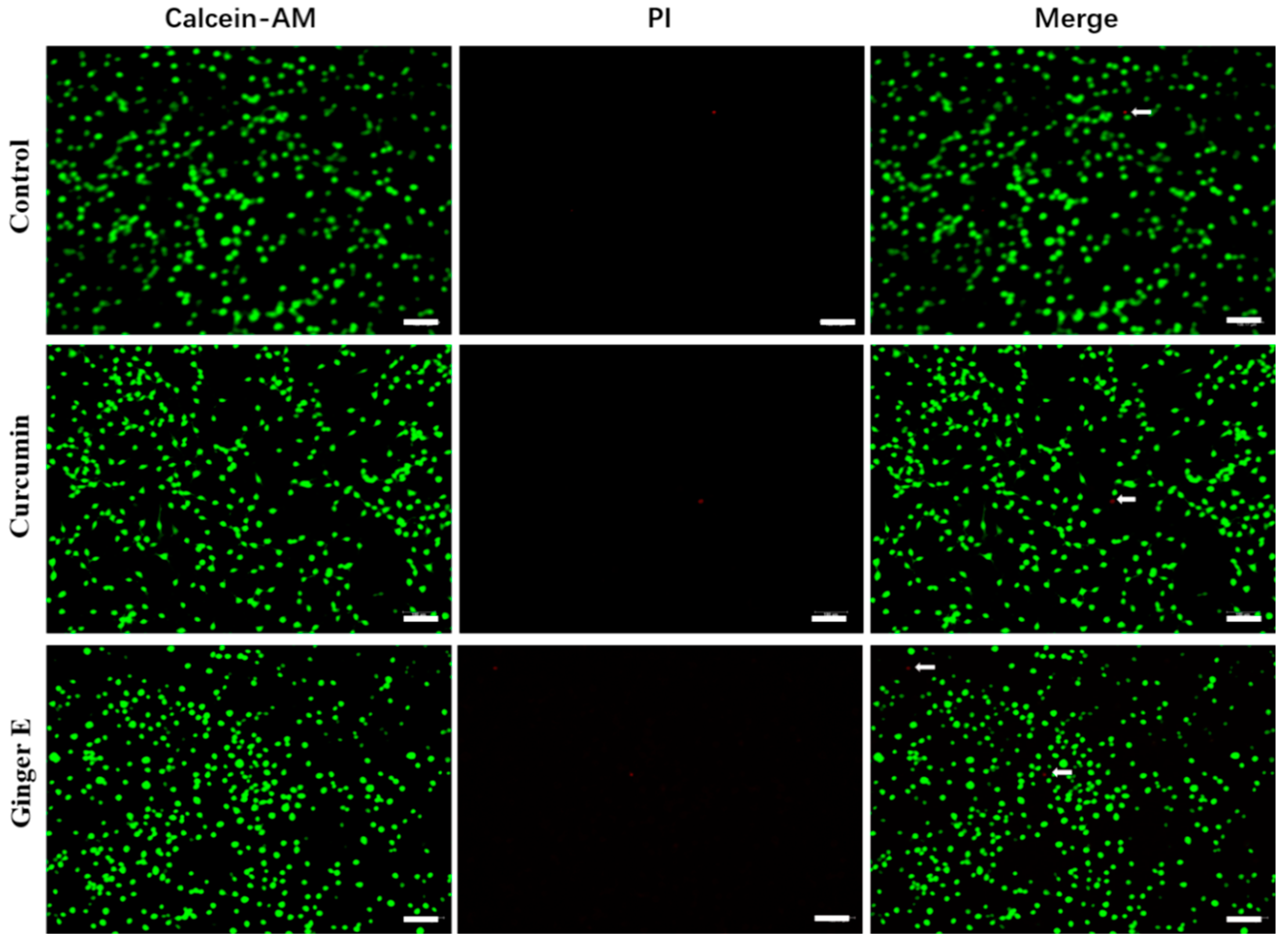

3.2. Cell Viability Assay

The cell viability test was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity and biocompatibility of the crude extract of Ginger E. Conventionally, the toxicity of materials to cells and the proliferation of cells are detected using the methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) method to evaluate the vitality of the cells[

23,

24,

25]. This analysis method comprises the following steps: action of MTT on the mitochondria of living cells, generation of blue crystals under the action of cytochrome C and succinate dehydrogenase, and reduction of MTT into blue crystals by succinate dehydrogenase from the living cells, wherein the more blue crystals there are, the more living cells there are. The optical density (OD) values at 490nm were used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of each group[

26]. Different concentrations of Ginger E were extracted using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM); curcumin was dissolved in absolute ethyl alcohol, and then diluted with DMEM to different concentrations; a control group was co-cultured with NIH3T3 cells in DMEM. As shown in

Figure 2 (A), after incubating NIH3T3 cells with different concentrations of Ginger E for 24 h, the cell viability was basically above 90%, indicating that it had good cell viability. The results showed that Ginger E had good biocompatibility. As shown in

Figure 2 (B), curcumin had obvious cytotoxicity at concentrations exceeding 12.5 µg/mL after 24 h, and the cell viability gradually decreased. Curcumin concentration below 12.5µg/mL, the cell viability was more than 80%, indicating that it has good biocompatibility at this concentration. Therefore, 12.5 µg/mL of curcumin was used as the control concentration in this study. At the same concentration (12.5 µg/mL), Ginger E also had good cell viability and biocompatibility. Therefore, a concentration of 12.5µg/mL was used as the experimental dose for both Ginger E and curcumin.

3.3. Hemolysis Experiment

Hemolysis experiments were performed to estimate the cytocompatibility of every group by the rupture and dissolution of red blood cells. Cytocompatibility is the basis for the use of biomedical materials[

27,

28]. The direct contact method was used to evaluate the biocompatibility of Ginger E[

29]. Hemolytic tests were performed using Ginger E and curcumin with concentrations of 12.5 µg/mL. Deionized water was used in positive group, and 0.9% sodium chloride injection was used as the negative group. These solutions were added to a Sprague–Dawley (SD) rat erythrocyte suspension. The absorbance value at 545 nm was detected by ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometry, and the hemolytic ratio was determined and analyzed[

30]. As shown in

Figure 2 (C-D), no obvious hemolysis was observed with the Ginger E, curcumin, and negative groups, and there was no significant difference between them in their hemolysis rates. In contrast, the hemolysis rate of each group was significantly different (

p < 0.05) from that of the positive group, which had a hemolysis rate that was far lower than the upper limit value of 5%. Therefore, the Ginger E, curcumin, and negative groups had better cell compatibility than the positive group.

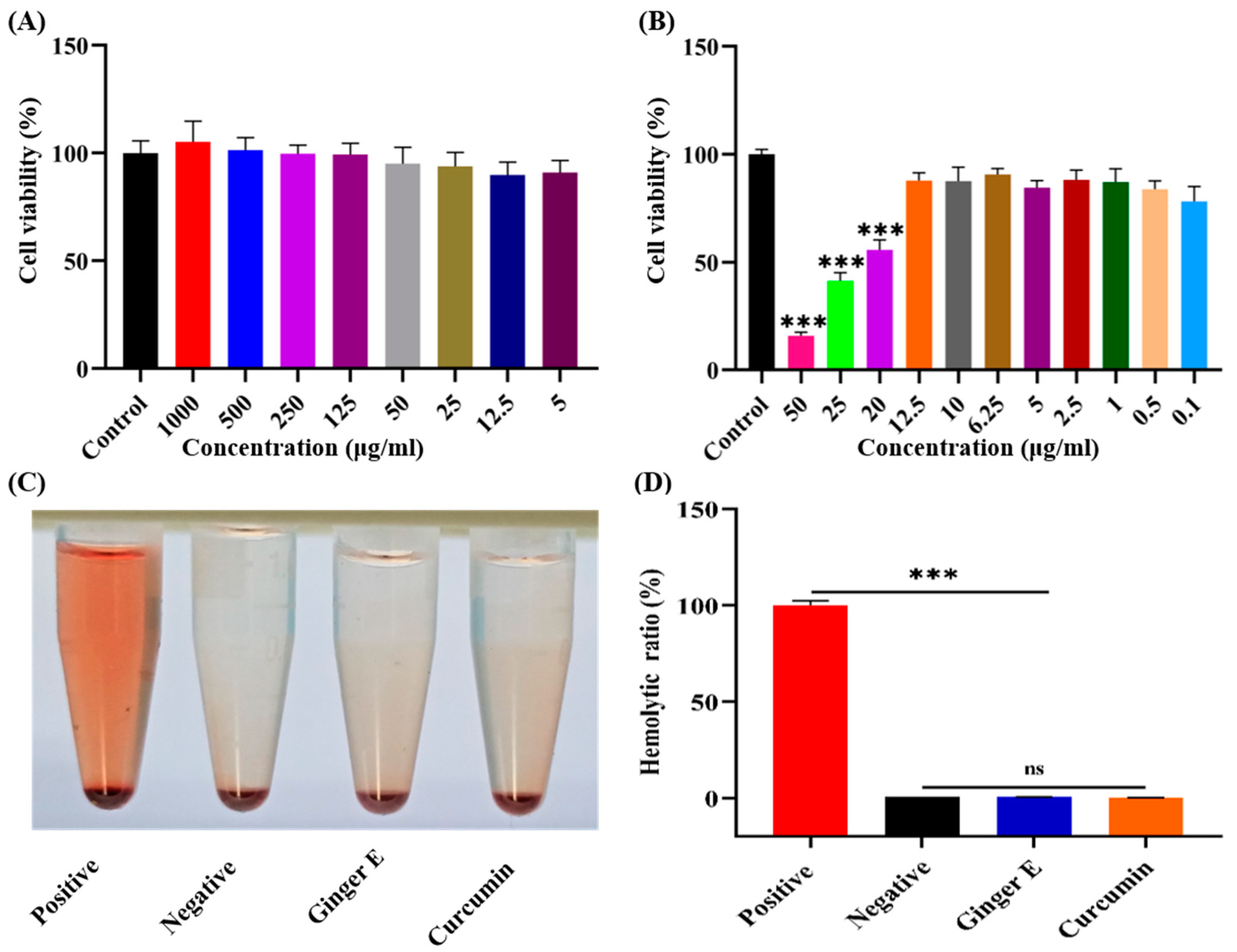

3.4. Live and Dead Staining

To further evaluate biocompatibility, Calcein-AM and propidium iodide (PI) staining was performed in the dark[

31,

32]. Ginger E and curcumin with concentrations of 12.5 µg/mL were cultured with NIH3T3 cells for 24 h; Pure DMEM and cell culture were used as control group. Green fluorescence indicates cells with good growth and red fluorescence indicates dead cells. As shown in

Figure 3, several living cells can be seen in the three groups. The cell morphology is normal, and no obvious dead cells exist, indicating that Ginger E and curcumin have good biocompatibility.

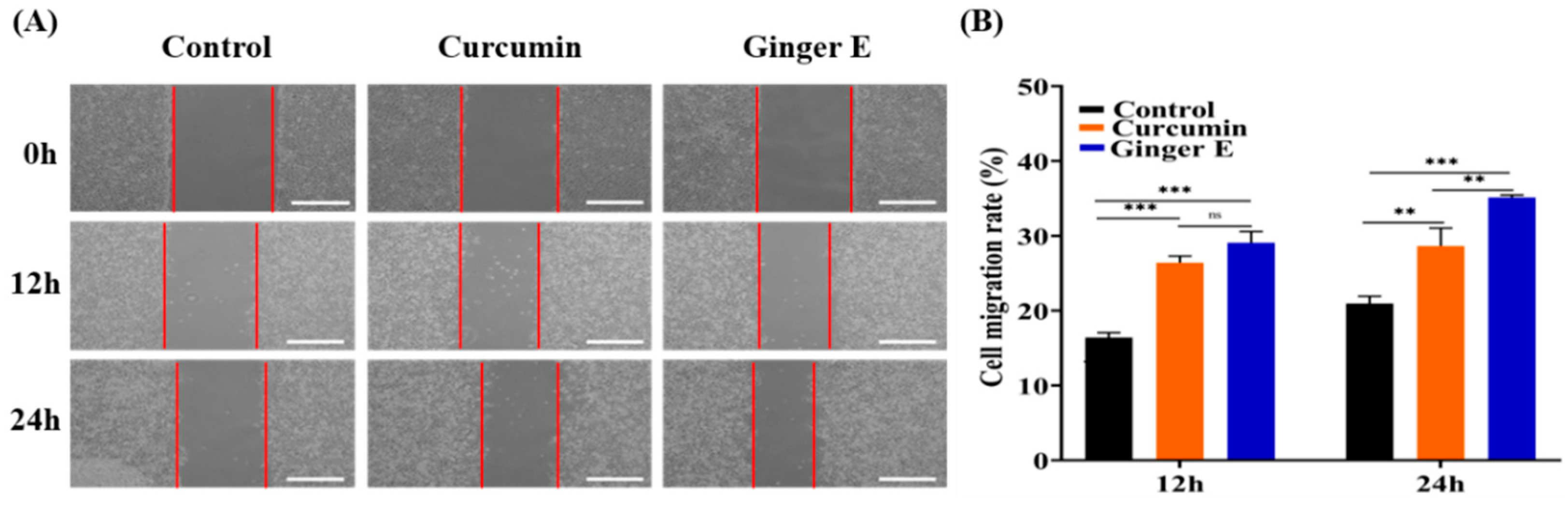

3.5. Cell Migration Assay

The scratch test is an important standard for detecting cell migration and wound healing, and it can be quantitatively evaluated based on the percentage of the wound healing area[

33,

34]. Ginger E and curcumin with concentrations of 12.5 µg/mL were added to a serum-free medium, and a control group containing the serum-free medium was prepared as well. NIH3T3 cells were cultured in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO

2 concentration. As shown in

Figure 4 (A), microscopic images of the cells were captured at the beginning of the incubation process and after 12 h and 24 h. As shown in

Figure 4 (B), after 12 h, the cell migration rates of the control, curcumin, and Ginger E groups were 16.41% ± 0.65%, 26.38% ± 0.96%, and 29.08% ± 1.5%, respectively. There was no difference in the mobility between Ginger E group and curcumin group. After 24 h, the cell migration rates of the control, curcumin, and Ginger E groups were 20.95% ± 0.98%, 28.62% ± 2.41%, and 35.12% ± 0.34%, respectively. Ginger E showed good cell compatibility and cell migration activity, and was superior to curcumin progenitor and control group (

p < 0.05). Therefore, Ginger E has good cell migration effect. These results are consistent with those of the cell viability tests. The good migration effect may be attributed to various nutrients in ginger.

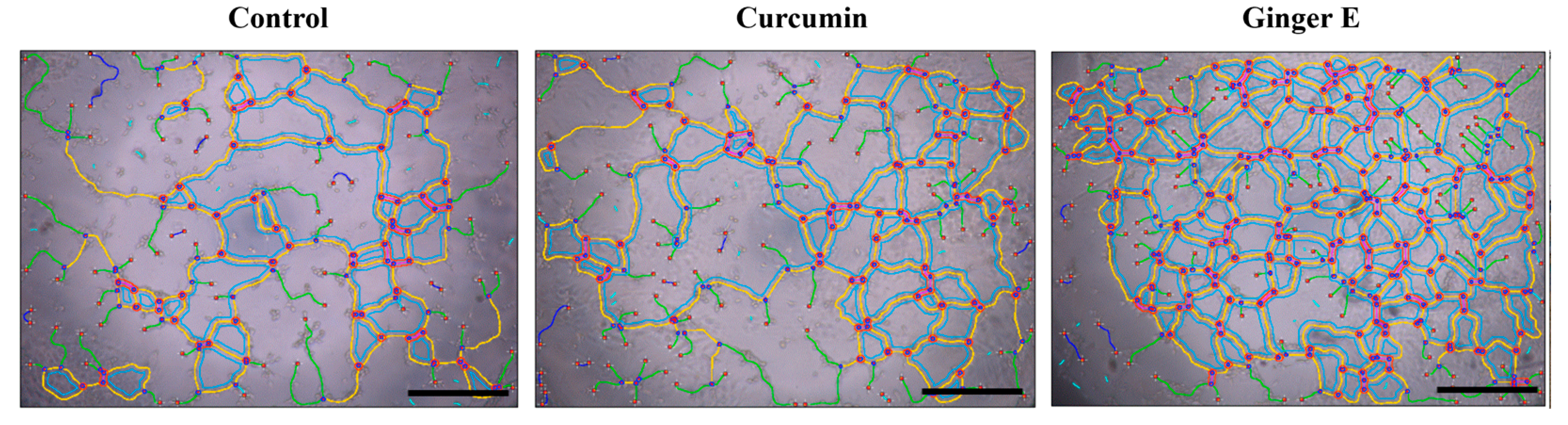

3.6. Angiogenesis Experiment

An angiogenesis experiment was used to evaluate the ability of the Ginger E to promote blood vessel growth. It also indirectly reflects the mechanism of tissue and cell growth. Ginger E and curcumin with concentrations of 12.5 µg/mL and a control group (serum-free culture medium) were co-precipitated with a human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) suspension and cultured on Matrix-Gel using the serum-free DMEM extraction method. As shown in

Figure 5, the Ginger E group was superior to the curcumin and control groups in terms of the number, length, node, mesh number, and density of blood vessels. Therefore, Ginger E can promote angiogenesis.

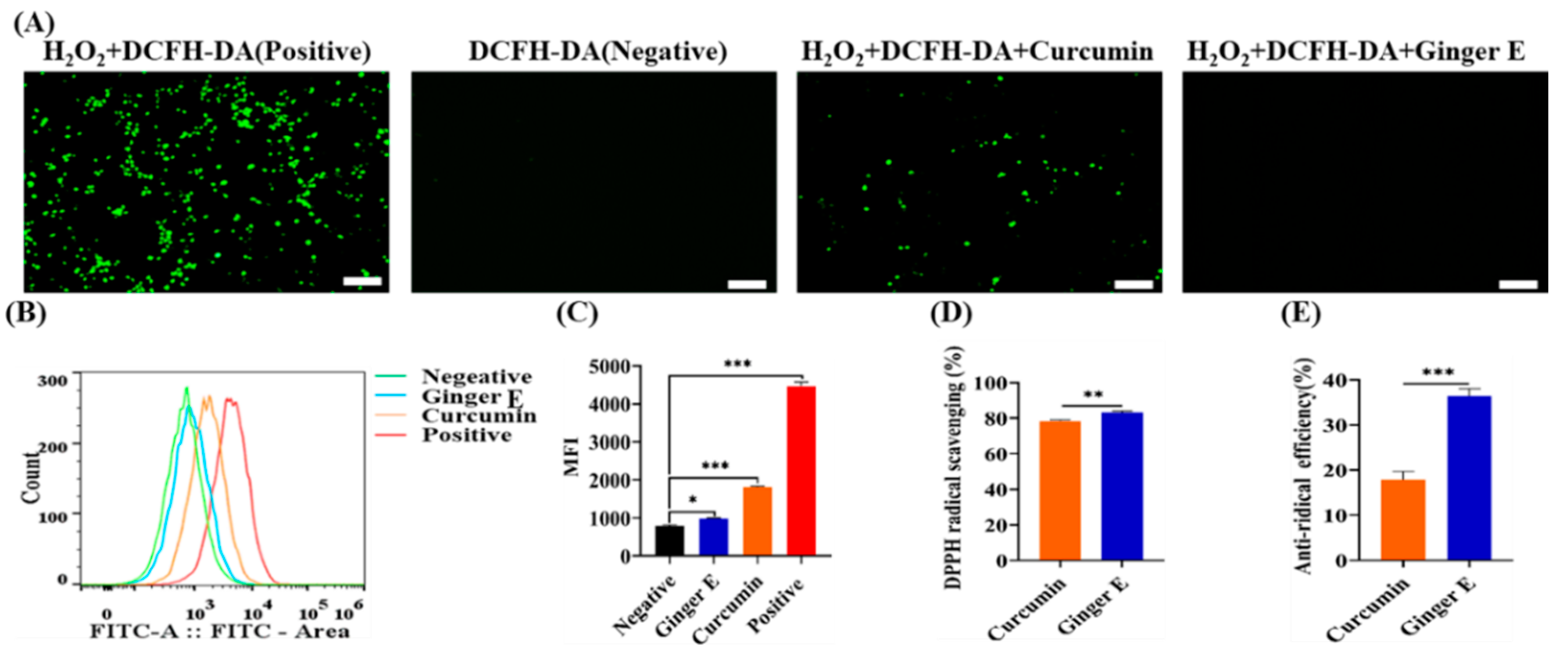

3.7. 2,7-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein Diacetate (DCFH-DA) Staining

An excessive amount of ROS can damage the cell structure and components such as the mitochondria, cell membrane, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), and protein[

35]. H

2O

2 was used to stimulate an oxidative stress damage environment in the cells, and Ginger E and curcumin were used to neutralize ROS, to verify their antioxidant activity. Accordingly, Ginger E group, curcumin group, positive group, and negative group were assembled. As shown in

Figure 6 (A), the positive group with the strongest fluorescence intensity, the fluorescence intensities of the Ginger E and negative groups were approximately equal, with almost no obvious fluorescence. Therefore, the Ginger E exhibited good antioxidant activity. The fluorescence intensity of curcumin group was higher than that of Ginger E group but lower than that of positive group, which indicates that the antioxidant activity of curcumin was lower than that of the Ginger E. As the fluorescence intensity is inversely proportional to the ROS resistance of a material, the results demonstrate that Ginger E has good antioxidant activity. The ROS flow absorption peak of each group after treatment is shown in

Figure 6 (B). According to the graph, the antioxidant activity of the Ginger E group was superior to those of the positive and curcumin groups. As illustrated in

Figure 6 (C), mean fluorescence intensity of the negative group was 794.33 ± 25.48,at of the Ginger E group was 980 ± 18.52, that of the curcumin group was 1850.33 ± 27.31, and that of the positive group was 4466 ± 108.05. The Ginger E exhibited excellent antioxidant activity that exceeded those of the curcumin and positive groups, with a significant difference (

p < 0.05). The results showed that the quantitative antioxidant activity detected by flow cytometry was consistent with the qualitative antioxidant activity detected by fluorescence.

3.8. DPPH Clearance Test

DPPH is a stable free radical in organic solvents. When free radical scavengers are present, the absorbance level of DPPH decreases, indicating that the sample has enhanced antioxidant capacity. Therefore, the DPPH clear rate is commonly measured the free radical scavenging capacity of a material[

36]. As shown in

Figure 6 (D), the DPPH scavenging rate of curcumin was 78.47% ± 0.64% and that of Ginger E was 83.24% ± 0.73%. Therefore, Ginger E had a higher DPPH free radical scavenging activity than curcumin, with a significant difference between them (

p < 0.05). Thus, the Ginger E had strong antioxidant activity, which was higher than that of curcumin. These results are consistent with those of DCFH-DA and flow cytometry.

3.9. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Assay

The antioxidant activity of Ginger E was further evaluated by determining the scavenging capacity of -OH[

37,

38]. Hydroxyl free radicals were produced by the Fenton reaction, and sodium salicylate reacted with a hydroxyl free radical to form 2, 3-dihydroxybenzoic acid. The content of 2, 3-dihydroxybenzoic acid was positively correlated with the content of free radicals at 510 nm. The hydroxyl radical scavenging rates of Ginger E and curcumin were evaluated quantitatively[

39]. As shown in

Figure 6 (E), the hydroxyl free radical scavenging rates of Ginger E and curcumin were 36.35% ± 1.67% and 17.8% ± 1.85%, respectively, with a significant difference between them (

p < 0.05). Therefore, Ginger E has a significantly higher hydroxyl radical scavenging rate and a superior direct antioxidant response effect than curcumin.

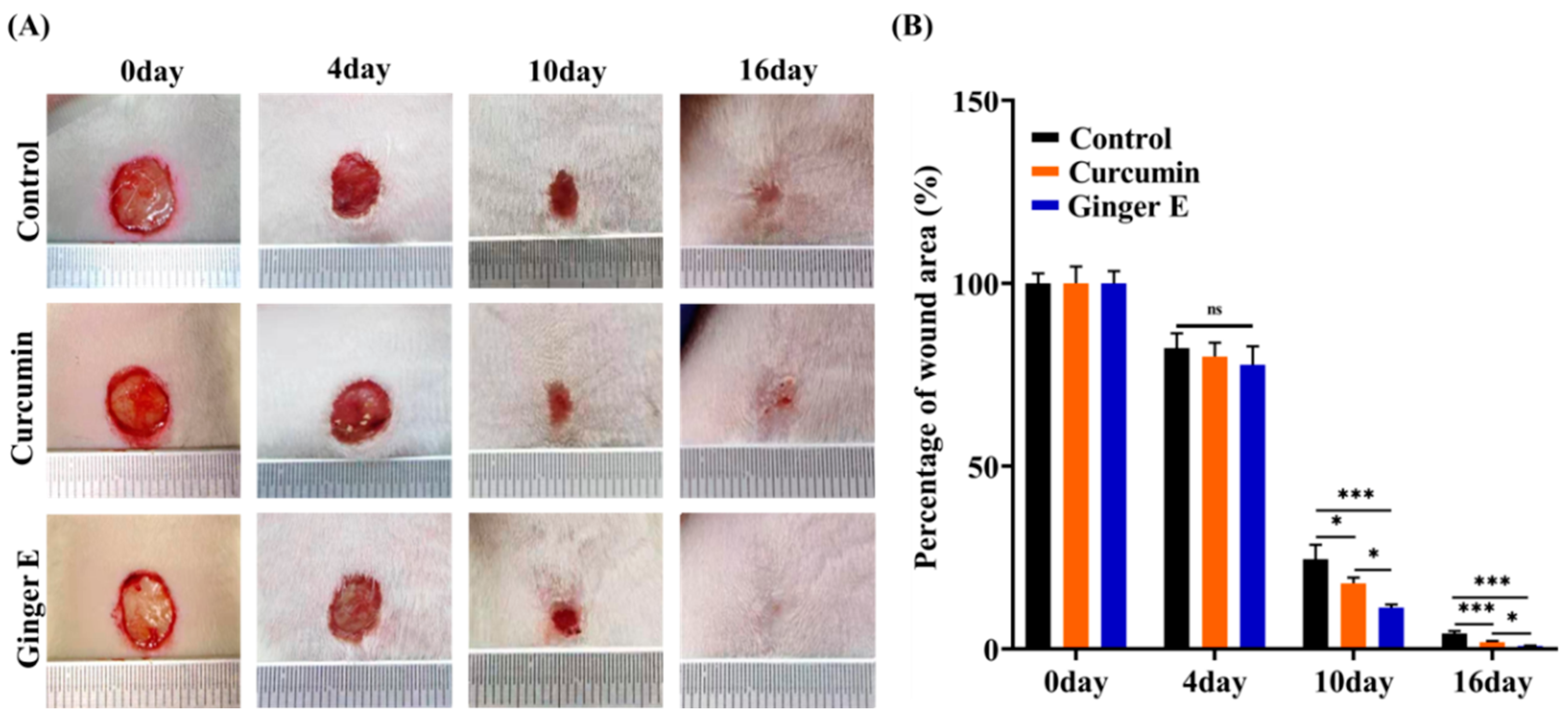

3.10. In Vivo Skin Wound Healing

Adult female SD rats were randomly assigned to Ginger E, curcumin, and control groups. A wound with a diameter of approximately 10 mm was created on the dorsal skin of the rats (

Figure 7A). The rats in the Ginger E and curcumin groups were treated with 12.5 µg/mL concentration solutions, whereas those in the control group were treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Each wound was treated with 100 µL of the solutions. The skin wounds were photographed before any treatment was provided and on the fourth, tenth, and sixteenth days of the treatment process. The photographs were analyzed using the ImageJ software. On the sixteenth day, the rats were killed, and the wound tissues were removed for hematoxylin (HE) and Masson staining for histological analysis. As shown in

Figure 7 (B), there was no significant difference between the wound healing rates of the Ginger E and curcumin groups on the fourth day. On the tenth day, the wound area percentages for the Ginger E, curcumin, and control groups were 9.38% ± 1.83%, 17.27% ± 1.1%, and 24.96% ± 4.81%, respectively. Therefore, the wound healing rate of the Ginger E group was significantly higher than that of the other two groups (

p < 0.05). On the sixteenth day, the wound of the Ginger E group was almost entirely healed, whereas the wound area percentages of the curcumin and control groups were 1.7% ± 0.14% and 4.22% ± 0.72%, respectively. Thus, the Ginger E accelerated wound healing, and was significantly better than the curcumin and control groups (

p < 0.05). Overall, Ginger E has a significantly better wound repair effect than curcumin.

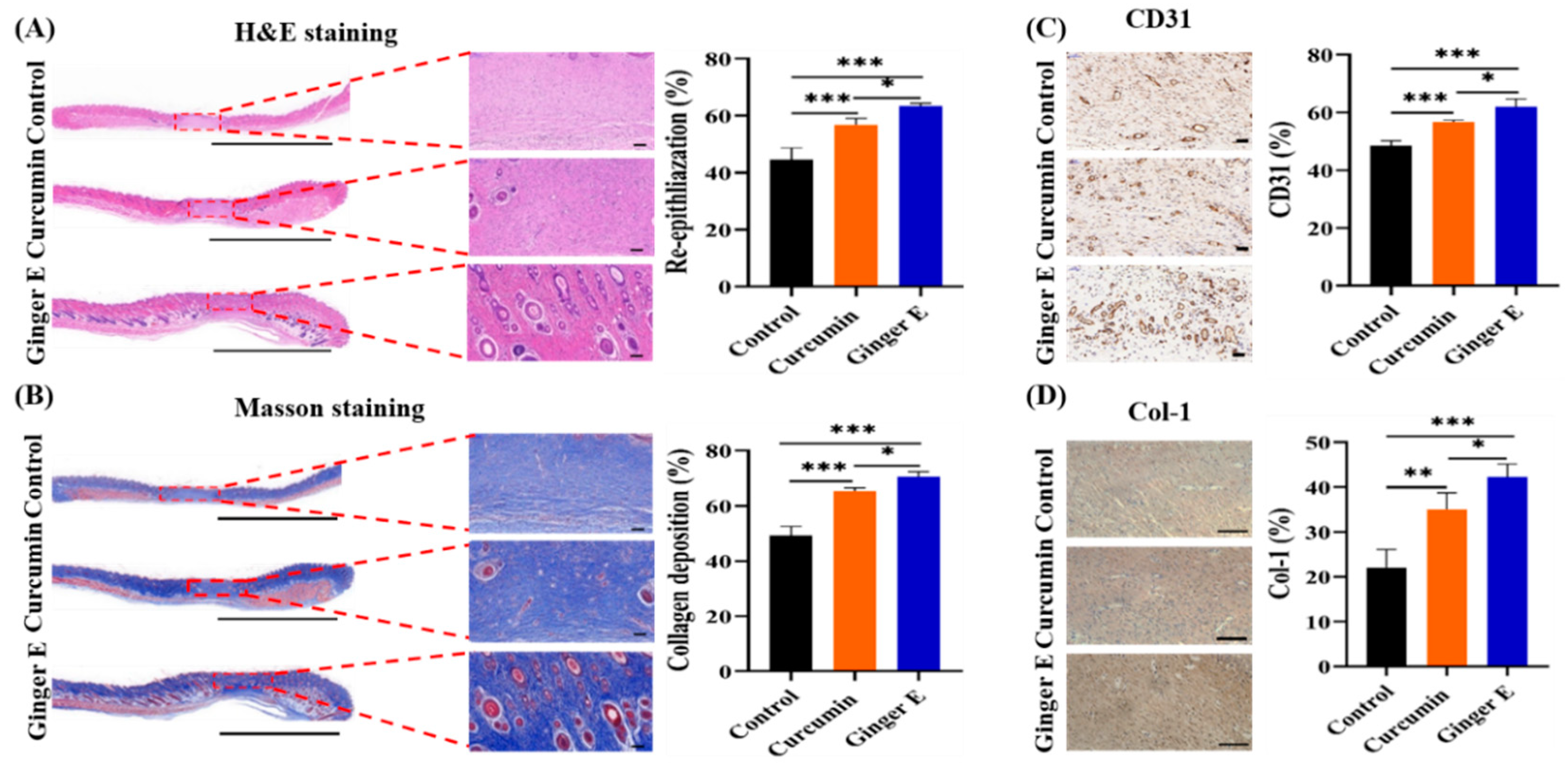

3.11. Histological Evaluation

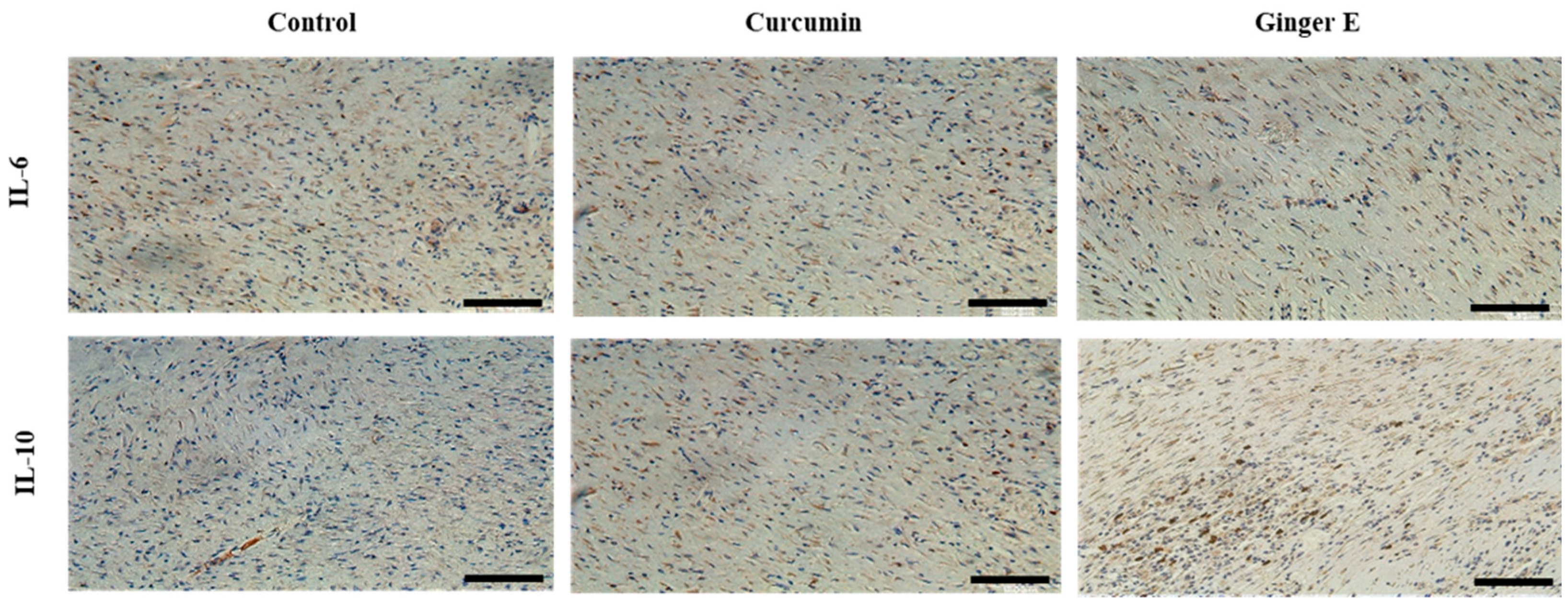

After 16 days of treatment, the skin of the wound sites of the rats was sectioned and sliced, and the histological structure and pathological changes at the wound site were observed. The growth of granulation tissue is an important indicator of wound healing[

40], as it contains several growth factors, fibroblasts, and collagen components. Histologically, HE and Masson staining were performed, at the same time while immunohistochemical analyses of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD31), collagen type 1 (Col-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-10 (IL-10) were performed on the wound specimens. As shown in the staining results in

Figure 8, wound tissue regeneration, collagen formation, and blood vessel and hair follicle formation were higher in the Ginger E group than in the blank control and curcumin groups. Therefore, Ginger E enhances wound repair.

Considering the wound immunohistochemistry, as shown in

Figure 8 (A), skin wound healing effect in each group was evaluated by detecting the degree of tissue regeneration in the granulation tissue: that of the Ginger E group was 63.31% ± 1.02%, that of the curcumin group was 56.69% ± 2.35%, and that of the control group was 44.55% ± 4.31%. As shown in

Figure 8 (B), the healing effect was evaluated through the quantitative analysis of the collagen content in the granulation tissue: that of the Ginger E group was 70.64% ± 1.74%, that of the curcumin group was 65.2% ± 1.29%, and that of the control group was 49.27% ± 3.24%.

Figure 8 (A-B) indicate that the Ginger E accelerated granulation tissue regeneration and collagen formation to accelerate wound healing, significantly better than curcumin and control groups (

p < 0.05). Therefore, the Ginger E provided better tissue remodeling and collagen formation than the curcumin and control groups. As shown in

Figure 8 (C), the CD31 content in the samples from the Ginger E, curcumin, and control groups was 61.89% ± 2.89%, 56.79% ± 0.51%, and 48.47% ± 1.76%, respectively. The Ginger E up-regulated the expression of vascular adhesion factors, thereby enhancing the adhesion function of the platelets and endothelial cells and accelerating wound healing. Consequently, Ginger E was better than the curcumin and control groups. As shown in

Figure 8 (D), the content of Col-1 in the Ginger E and curcumin groups was more orderly and compact than that in the control group, with a relatively complete structure. The Col-1 collagen content was 42.24% ± 1.70% in the Ginger E group, 35% ± 0.77% in the curcumin group, and 22.1% ± 1.05% in the control group. Therefore, the Col-1 collagen content of the Ginger E group was better than that in other groups and there were significant differences (

p < 0.05). Col-1 is an important component of collagen fibers in skin tissue. As collagen fibers play an important part in tissue remodeling and regeneration, these results further indicate that Ginger E promotes wound repair and healing. As shown in

Figure 9, the Ginger E group not only down-regulated inflammatory factors IL-6, but also promote the expression of IL-10. The performance of the Ginger E was superior to that of the control and curcumin groups, which indicates that Ginger E has a good anti-inflammatory effect that accelerates wound healing.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, Ginger E prepared by a simple method had a better therapeutic effect on skin wound healing than curcumin alone. They both had good biocompatibility and excellent hydroxyl radical scavenging ability in vitro. However, Ginger E showed better antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects than curcumin. At the same time, Ginger E also had a better effect of promoting migration and angiogenesis. This may be because Ginger E had a wider variety of bioactive components, which contribute to the scavenging of ROS and wound healing. Overall, Ginger E had great potential in wound healing, but more effective applications and treatments need to be further explored in the future.

Author Contributions

The experiments were conceived by L.S; the experiments were performed by C.Z. (Conglai Zhou), P.X.( Peikun Xin) and J.H.; C.Z. (Conglai Zhou), Q.Y. (Qiming Yang) and X.Y. (XiaoLi You) developed, drafted,and wrote the manuscript and developed the figures; J.H. and P.X.( Peikun Xin). revised the manuscript; L.S. conceived the idea and supervised the content and writing; L.S. and L.C. critically contributed to the content and reviewed the manuscript to ensure accuracy and completeness. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82460430).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sun Yat-sen University (SYSU-IACUC-2020-000573) on 30 December 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maeso, L.; Antezana, P.E.; Hvozda Arana, A.G.; Evelson, P.A.; Orive, G.; Desimone, M.F. Progress in the Use of Hydrogels for Antioxidant Delivery in Skin Wounds. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, C.; Gu, Z.; Liu, G.; Wu, J. Whole wheat flour coating with antioxidant property accelerates tissue remodeling for enhanced wound healing. Chinese Chemical Letters 2020, 31, 1612–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, A.; Gupta, J.; Gupta, R. Miracles of Herbal Phytomedicines in Treatment of Skin Disorders: Natural Healthcare Perspective. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2021, 21, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.; Li, Q.; Qiu, J.; Chen, J.; Du, S.; Xu, X.; Wu, Z.; Yang, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, T. Nanobiotechnology: Applications in Chronic Wound Healing. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 3125–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Rong, F.; Li, Z.; Li, W.; Kaur, K.; Wang, Y.J.C.E.J. Tailoring gas-releasing nanoplatforms for wound treatment: An emerging approach. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Fan, L.; Zhao, Y.J.C.E.J. Multifunctional microneedle patches with aligned carbon nanotube sheet basement for promoting wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 457, 141206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N. In Vitro and In Vivo Characterization Methods for Evaluation of Modern Wound Dressings. Pharmaceutics 2022, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Liu, S.; Xin, X.; Li, P.; Dou, J.; Han, X.; Kang, I.-K.; Yuan, J.; Chi, B.; Shen, J.J.C.e.j. S-nitrosated keratin composite mats with NO release capacity for wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 400, 125964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tottoli, E.M.; Dorati, R.; Genta, I.; Chiesa, E.; Pisani, S.; Conti, B. Skin Wound Healing Process and New Emerging Technologies for Skin Wound Care and Regeneration. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabestani Monfared, G.; Ertl, P.; Rothbauer, M. Microfluidic and Lab-on-a-Chip Systems for Cutaneous Wound Healing Studies. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Song, W.; He, Y.; Li, H. Multilayer Injectable Hydrogel System Sequentially Delivers Bioactive Substances for Each Wound Healing Stage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 29787–29806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.W.; Liu, S.Y.; Jia, Y.; Zou, M.L.; Teng, Y.Y.; Chen, Z.H.; Li, Y.; Guo, D.; Wu, J.J.; Yuan, Z.D. , et al. Insight into the role of DPP-4 in fibrotic wound healing. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Hou, J.; Yuan, Q.; Xin, P.; Cheng, H.; Gu, Z.; Wu, J.J.C.E.J. Arginine derivatives assist dopamine-hyaluronic acid hybrid hydrogels to have enhanced antioxidant activity for wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 392, 123775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanidad, K.Z.; Sukamtoh, E.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J.; Zhang, G. Curcumin: Recent Advances in the Development of Strategies to Improve Oral Bioavailability. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, Z.; Nejatian, M.; Daeihamed, M.; Jafari, S.M. Application of curcumin-loaded nanocarriers for food, drug and cosmetic purposes. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yuan, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Chen, S.; Ma, J.; Zhou, F. Curcumin Functionalized Electrospun Fibers with Efficient pH Real-Time Monitoring and Antibacterial and Anti-inflammatory Properties. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fereydouni, N.; Darroudi, M.; Movaffagh, J.; Shahroodi, A.; Butler, A.E.; Ganjali, S.; Sahebkar, A. Curcumin nanofibers for the purpose of wound healing. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 5537–5554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, L.F.; Darwis, Y.; Koh, R.Y.; Gah Leong, K.V.; Yew, M.Y.; Por, L.Y.; Yam, M.F. Wound Healing Property of Curcuminoids as a Microcapsule-Incorporated Cream. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkur, M.; Benlier, N.; Takan, I.; Vasileiou, C.; Georgakilas, A.G.; Pavlopoulou, A.; Cetin, Z.; Saygili, E.I. Ginger for Healthy Ageing: A Systematic Review on Current Evidence of Its Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anticancer Properties. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 4748447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabr, S.A.; Alghadir, A.H.; Ghoniem, G.A. Biological activities of ginger against cadmium-induced renal toxicity. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, R.; Gani, A.; Masarat Dar, M.; Bhat, N.A. Bioactive characterization of ultrasonicated ginger (Zingiber officinale) and licorice (Glycyrrhiza Glabra) freeze dried extracts. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2022, 88, 106048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, X.; Wang, F.; Xu, J.; Tang, X.; Li, N. Structural characterization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from ginger. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloum-Ardakani, M.; Barazesh, B.; Moshtaghioun, S.M.; Sheikhha, M.H. Designing and optimization of an electrochemical substitute for the MTT (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) cell viability assay. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; An, Y.L.; Wang, X.S.; Cui, L.Y.; Li, S.Q.; Liu, C.B.; Zou, Y.H.; Zhang, F.; Zeng, R.C. In vitro degradation, photo-dynamic and thermal antibacterial activities of Cu-bearing chlorophyllin-induced Ca-P coating on magnesium alloy AZ31. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 18, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalli, J.; de Assis, P.M.; Cristina Dalazen Gonçalves, E.; Daniele Bobermin, L.; Quincozes-Santos, A.; Raposo, N.R.B.; Gomez, M.V.; Dutra, R.C. Systemic, Intrathecal, and Intracerebroventricular Antihyperalgesic Effects of the Calcium Channel Blocker CTK 01512-2 Toxin in Persistent Pain Models. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 4436–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vajrabhaya, L.-o.; Korsuwannawong, S. Cytotoxicity evaluation of a Thai herb using tetrazolium (MTT) and sulforhodamine B (SRB) assays. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Guo, B.; Wu, H.; Liang, Y.; Ma, P.X. Injectable antibacterial conductive nanocomposite cryogels with rapid shape recovery for noncompressible hemorrhage and wound healing. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Huang, J.; Gui, S.; Chu, X. Preparation, Synergism, and Biocompatibility of in situ Liquid Crystals Loaded with Sinomenine and 5-Fluorouracil for Treatment of Liver Cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 3725–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liang, X.; Ma, P.X.; Guo, B. Injectable hydrogel based on quaternized chitosan, gelatin and dopamine as localized drug delivery system to treat Parkinson's disease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, W.; Wei, B.; Wang, X.; Tang, R.; Nie, J.; Wang, J. Carboxyl-modified poly(vinyl alcohol)-crosslinked chitosan hydrogel films for potential wound dressing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 125, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Gu, Z.; Wu, J. Tofu-Incorporated Hydrogels for Potential Bone Regeneration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 3037–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.Y.; Kim, H.; Kwak, G.; Yoon, H.Y.; Jo, S.D.; Lee, J.E.; Cho, D.; Kwon, I.C.; Kim, S.H. Development of Biocompatible HA Hydrogels Embedded with a New Synthetic Peptide Promoting Cellular Migration for Advanced Wound Care Management. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varankar, S.S.; Bapat, S.A. Migratory Metrics of Wound Healing: A Quantification Approach for in vitro Scratch Assays. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortesi, M.; Pasini, A.; Tesei, A.; Giordano, E.J.A.S. AIM: a computational tool for the automatic quantification of scratch wound healing assays. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, H.A.; Thakore, R.; Singh, R.; Jhala, D.; Singh, S.; Vasita, R. Antioxidative study of Cerium Oxide nanoparticle functionalised PCL-Gelatin electrospun fibers for wound healing application. Bioact. Mater. 2018, 3, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, A.; Rojas, P.; Cely-Veloza, W.; Guerrero-Perilla, C.; Coy-Barrera, E. Variation of isoflavone content and DPPH• scavenging capacity of phytohormone-treated seedlings after in vitro germination of cape broom (Genista monspessulana). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 130, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Zhao, X.; Liang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ma, P.X.; Guo, B. Degradable conductive injectable hydrogels as novel antibacterial, anti-oxidant wound dressings for wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 362, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, Q.V.; Van Bay, M.; Nam, P.C.; Mechler, A. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging of Indole-3-Carbinol: A Mechanistic and Kinetic Study. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 19375–19381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, J.; Lu, L.; Liu, Y. Antiradical and Antioxidative Activity of Azocalix[4]arene Derivatives: Combined Experimental and Theoretical Study. Molecules 2019, 24, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, K.; Wang, H.; Duan, C.; Ni, N.; An, L.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, P.; Gou, Y.; et al. Reversibly immortalized keratinocytes (iKera) facilitate re-epithelization and skin wound healing: Potential applications in cell-based skin tissue engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 9, 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of preparation of Ginger E and its effect on wound healing.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of preparation of Ginger E and its effect on wound healing.

Figure 2.

(A) The survival rate of NIH3T3 cells cultured with different concentrations of Ginger E for 24 h. (B) The survival rate of NIH3T3 cells cultured for 24 h with different concentrations of curcumin. (C) Hemolysis images of each group. (D) Hemolysis rates of ultrapure water, 0.9% sodium chloride injection, 12.5 µg/mL Ginger E and 12.5 µg/mL curcumin treatments. ***p<0.001,ns: not significant, (Mean ± SD, n=3).

Figure 2.

(A) The survival rate of NIH3T3 cells cultured with different concentrations of Ginger E for 24 h. (B) The survival rate of NIH3T3 cells cultured for 24 h with different concentrations of curcumin. (C) Hemolysis images of each group. (D) Hemolysis rates of ultrapure water, 0.9% sodium chloride injection, 12.5 µg/mL Ginger E and 12.5 µg/mL curcumin treatments. ***p<0.001,ns: not significant, (Mean ± SD, n=3).

Figure 3.

Live and dead stained images. Green fluorescence indicates living cells, red fluorescence indicates dead cells (Scale bars: 100 µm, n =3).

Figure 3.

Live and dead stained images. Green fluorescence indicates living cells, red fluorescence indicates dead cells (Scale bars: 100 µm, n =3).

Figure 4.

Cell migration experiment. (A) The qualitative results of wound repair in the scratch test (Scale bars: 500 µm). (B) Quantitative analysis of the results in Figure (A). **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ns: not significant, (Mean ± SD, n=3).

Figure 4.

Cell migration experiment. (A) The qualitative results of wound repair in the scratch test (Scale bars: 500 µm). (B) Quantitative analysis of the results in Figure (A). **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ns: not significant, (Mean ± SD, n=3).

Figure 5.

Pro-angiogenic assay (Scale bars: 500 µm. n =3).

Figure 5.

Pro-angiogenic assay (Scale bars: 500 µm. n =3).

Figure 6.

Scavenging experiment of reactive oxygen species in vitro. (A) Representative images of intracellular fluorescence (Scale bars: 100 µm). (B) The magnitude of the fluorescence intensity and the number of cells under the corresponding conditions. (C) Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity of ROS. (D) Quantitative comparative analysis of DPPH clearance rates of Ginger E and curcumin with concentrations of 12.5 µg/mL. (E) Quantitative comparative analysis of hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of Ginger E and curcumin with concentrations of 12.5 µg/mL. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, (Mean ± SD, n=3).

Figure 6.

Scavenging experiment of reactive oxygen species in vitro. (A) Representative images of intracellular fluorescence (Scale bars: 100 µm). (B) The magnitude of the fluorescence intensity and the number of cells under the corresponding conditions. (C) Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity of ROS. (D) Quantitative comparative analysis of DPPH clearance rates of Ginger E and curcumin with concentrations of 12.5 µg/mL. (E) Quantitative comparative analysis of hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of Ginger E and curcumin with concentrations of 12.5 µg/mL. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, (Mean ± SD, n=3).

Figure 7.

Experimental results of wound healing promotion in vivo. (A) Representative images of wound surface. (B) Quantitative comparison of final wound contraction area. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, ns: not significant (Mean ± SD, n=4).

Figure 7.

Experimental results of wound healing promotion in vivo. (A) Representative images of wound surface. (B) Quantitative comparison of final wound contraction area. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, ns: not significant (Mean ± SD, n=4).

Figure 8.

After 16 days of treatment in Ginger E group, curcumin group and control group. (A)Qualitative analysis of re-epithelialization and histological score of wound granulation tissue were performed (Scale bars: 5000 µm, 100 µm). (B)Collagen deposition and percentage of collagen tissue content (Scale bars: 5000 µm, 100 µm). (C)CD31 protein expression and content percentage (Scale bars: 500 µm). (D)Col-1 qualitative analysis and content percentage (Scale bars: 100 µm). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001(Mean ±SD, n=4).

Figure 8.

After 16 days of treatment in Ginger E group, curcumin group and control group. (A)Qualitative analysis of re-epithelialization and histological score of wound granulation tissue were performed (Scale bars: 5000 µm, 100 µm). (B)Collagen deposition and percentage of collagen tissue content (Scale bars: 5000 µm, 100 µm). (C)CD31 protein expression and content percentage (Scale bars: 500 µm). (D)Col-1 qualitative analysis and content percentage (Scale bars: 100 µm). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001(Mean ±SD, n=4).

Figure 9.

Qualitative analysis of IL-6 and IL-10 ELISA of wound tissue (Scale bars: 100 µm, n=4).

Figure 9.

Qualitative analysis of IL-6 and IL-10 ELISA of wound tissue (Scale bars: 100 µm, n=4).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).