Submitted:

27 September 2024

Posted:

30 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

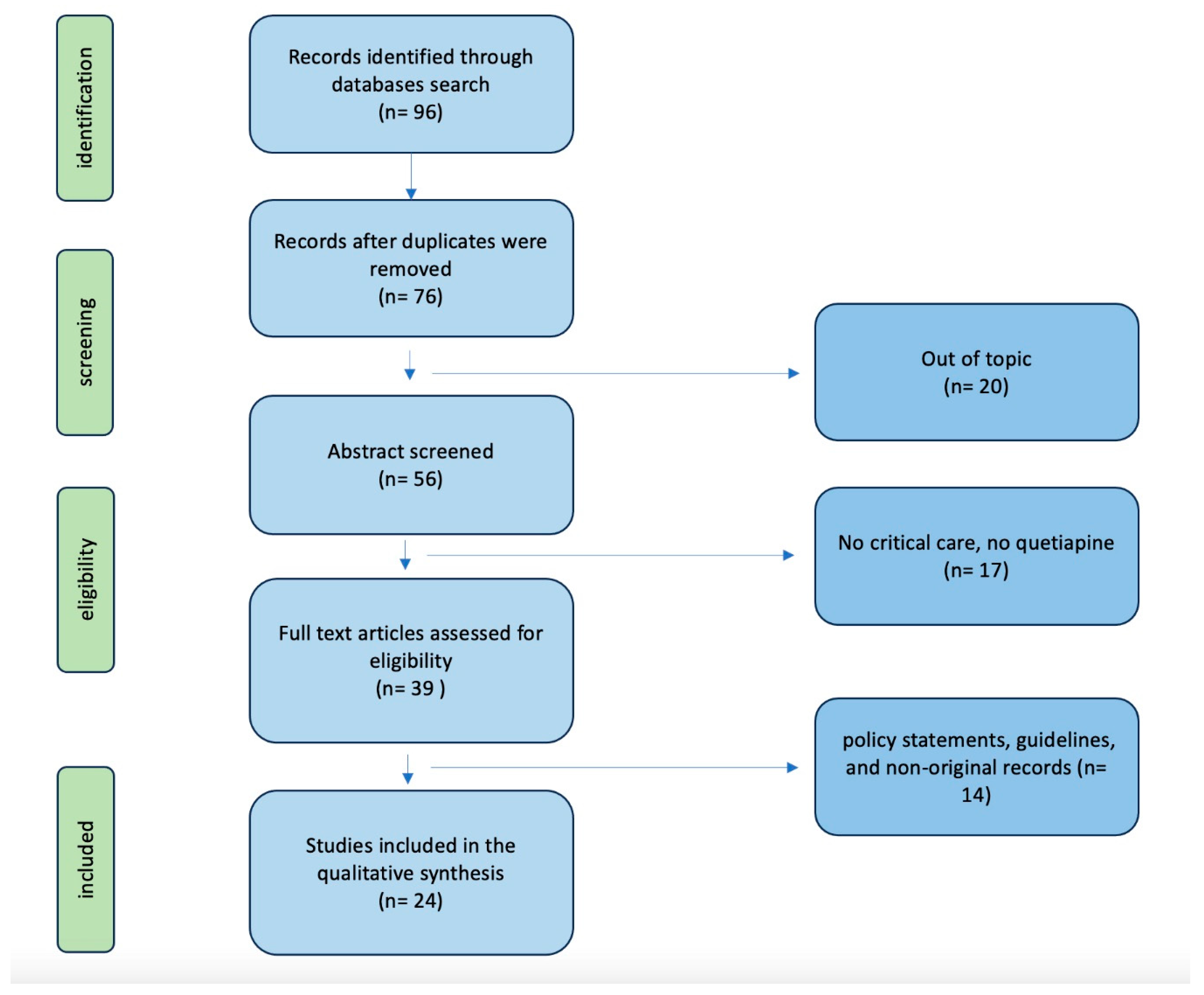

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Definition and Characteristics of Delirium

2.1. Clinical Features of Delirium

3. Quetiapine in ICU Care: Applications, Dosage, and Key Considerations

4.2. Quetiapine in the Pediatric ICU Setting

5. Contraindications, Toxicity, and Cautions

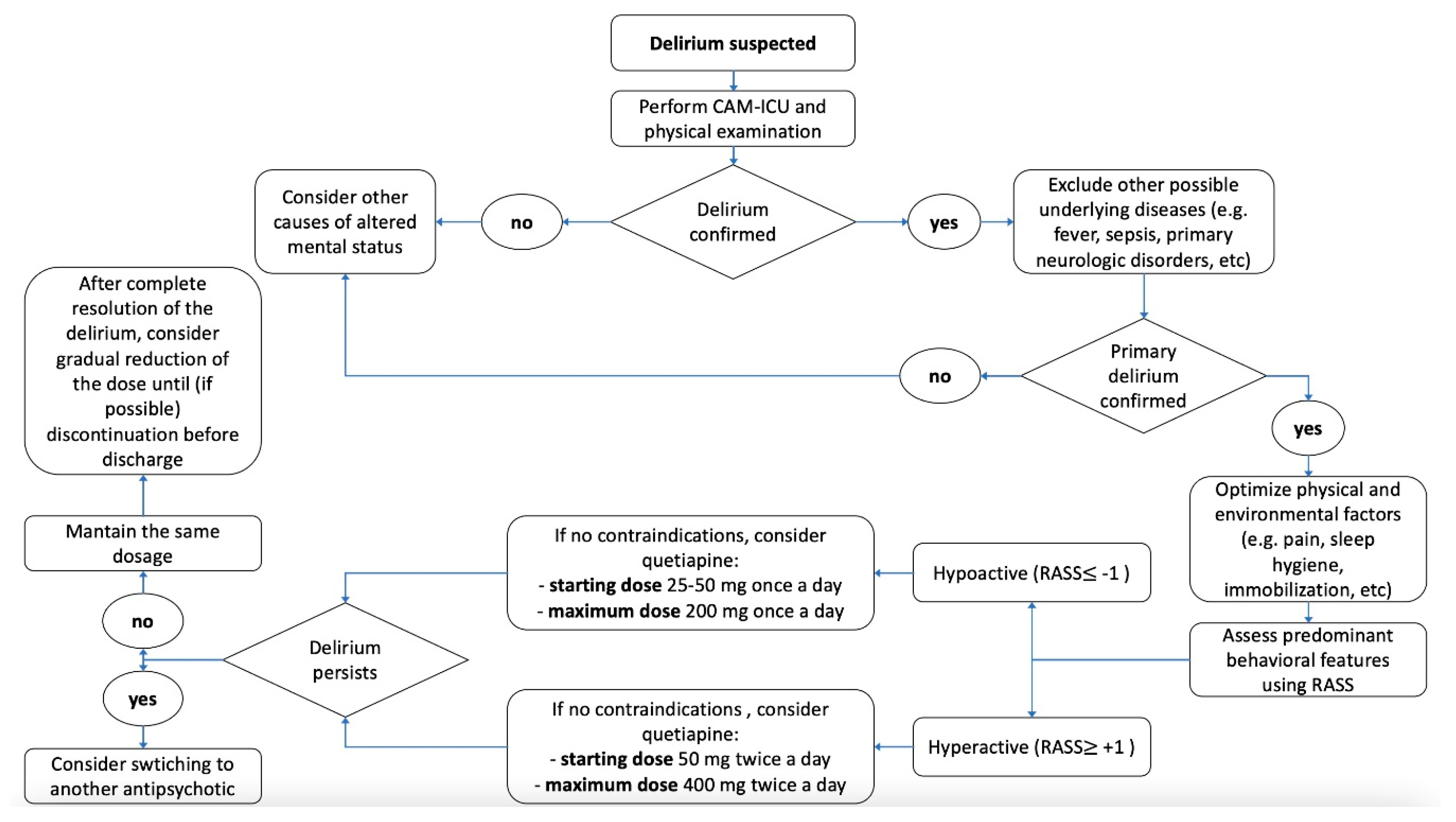

6. Clinical Practical Algorithm

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, M.; Cascella, M. ICU Delirium. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fiest, K.M.; Soo, A.; Hee Lee, C.; Niven, D.J.; Ely, E.W.; Doig, C.J.; Stelfox, H.T. Long-Term Outcomes in ICU Patients with Delirium: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021, 204, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez Echeverría, M.d.L.; Schoo, C.; Paul, M. Delirium. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mart, M.F.; Boehm, L.M.; Kiehl, A.L.; Gong, M.N.; Malhotra, A.; Owens, R.L.; Khan, B.A.; Pisani, M.A.; Schmidt, G.A.; Hite, R.D.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes after Treatment of Delirium during Critical Illness with Antipsychotics (MIND-USA): A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2024, 12, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.-C.; Yeh, T.Y.-C.; Wei, Y.-C.; Ku, S.-C.; Xu, Y.-J.; Chen, C.C.-H.; Inouye, S.; Boehm, L.M. Association of Incident Delirium With Short-Term Mortality in Adults With Critical Illness Receiving Mechanical Ventilation. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2235339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessler, C.N.; Gosnell, M.S.; Grap, M.J.; Brophy, G.M.; O’Neal, P.V.; Keane, K.A.; Tesoro, E.P.; Elswick, R.K. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: Validity and Reliability in Adult Intensive Care Unit Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 166, 1338–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ely, E.W.; Truman, B.; Shintani, A.; Thomason, J.W.W.; Wheeler, A.P.; Gordon, S.; Francis, J.; Speroff, T.; Gautam, S.; Margolin, R.; et al. Monitoring Sedation Status over Time in ICU Patients: Reliability and Validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA 2003, 289, 2983–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, F.E.; Tee, R.; Poulter, A.-L.; Jordan, L.; Bell, L.; Balogh, Z.J. Delirium Screening and Pharmacotherapy in the ICU: The Patients Are Not the Only Ones Confused. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.-Y.; Lockwood, C.; Tsou, Y.-C.; Mu, P.-F.; Liao, S.-C.; Chen, W.-C. Implementing the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale in a Respiratory Critical Care Unit: A Best Practice Implementation Project. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2019, 17, 1717–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashidi, M.; Molavynejad, S.; Javadi, N.; Adineh, M.; Sharhani, A.; Poursangbur, T. The Effect of Using Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale on Hospital Stay, Ventilator Dependence, and Mortality Rate in ICU Inpatients: A Randomised Clinical Trial. J Res Nurs 2020, 25, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunther, M.L.; Morandi, A.; Ely, E.W. Pathophysiology of Delirium in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Clin 2008, 24, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, R.; Nakamura, K.; Takatani, Y.; Tanaka, C.; Kondo, Y.; Ohbe, H.; Kamijo, H.; Otake, K.; Nakamura, A.; Ishikura, H.; et al. Sepsis-Associated Delirium: A Narrative Review. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Rhim, H.C.; Park, A.; Kim, H.; Han, K.-M.; Patkar, A.A.; Pae, C.-U.; Han, C. Comparative Efficacy and Acceptability of Pharmacological Interventions for the Treatment and Prevention of Delirium: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2020, 125, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, J.; Herzig, S.J.; Howell, M.D.; Le, S.H.; Mathew, C.; Kats, J.S.; Stevens, J.P. Antipsychotic Utilization in the Intensive Care Unit and in Transitions of Care. J Crit Care 2016, 33, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, J.W.; Skrobik, Y. Antipsychotics for the Prevention and Treatment of Delirium in the Intensive Care Unit: What Is Their Role? Harv Rev Psychiatry 2011, 19, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, J.T.; Fitousis, K.; Hall, J.B.; Todd, S.R.; Turner, K.L. Antipsychotic Use and Diagnosis of Delirium in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care 2012, 16, R84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kram, B.L.; Kram, S.J.; Brooks, K.R. Implications of Atypical Antipsychotic Prescribing in the Intensive Care Unit. J Crit Care 2015, 30, 814–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, J.W.; Michaud, C.J.; Bullard, H.M.; Harris, S.A.; Thomas, W.L. Quetiapine for Intensive Care Unit Delirium: The Evidence Remains Weak. Pharmacotherapy 2016, 36, e12–e13, discussion e13–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghadeer, S.; Almesned, R.S.; Alshehri, E.A.; Alwhaibi, A. Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of Quetiapine in the Treatment of Delirium in Adult ICU Patients: A Retrospective Comparative Study. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.P.; Adie, S.K.; Ketcham, S.W.; Deshmukh, A.; Gondi, K.; Abdul-Aziz, A.A.; Prescott, H.C.; Thomas, M.P.; Konerman, M.C. Atypical Antipsychotic Safety in the CICU. Am J Cardiol 2022, 163, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, M.T.; Di Gennaro, J.L.; Watson, R.S.; Dervan, L.A. Haloperidol and Quetiapine for the Treatment of ICU-Associated Delirium in a Tertiary Pediatric ICU: A Propensity Score-Matched Cohort Study. Paediatr Drugs 2021, 23, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakhary, T.; Ahmed, I.; Luttfi, I.; Montasser, M. Quetiapine Versus Haloperidol in the Management of Hyperactive Delirium: Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurocrit Care 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Yam, F.K. Rational Use of Second-Generation Antipsychotics for the Treatment of ICU Delirium. J Pharm Pract 2017, 30, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, S.; El-Menyar, A.; Al-Hassani, A.; Strandvik, G.; Asim, M.; Mekkodithal, A.; Mudali, I.; Al-Thani, H. Delirium in the Intensive Care Unit. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2017, 10, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders | Psychiatry Online. Available online: https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Stevens, R.D.; Nyquist, P.A. Coma, Delirium, and Cognitive Dysfunction in Critical Illness. Crit Care Clin 2006, 22, 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, A.; Young, J.B. Which Medications to Avoid in People at Risk of Delirium: A Systematic Review. Age Ageing 2011, 40, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, M.; Reininghaus, E.Z.; Biasi, J.D.; Fellendorf, F.T.; Schoberer, D. Delirium-associated Medication in People at Risk: A Systematic Update Review, Meta-analyses, and GRADE-profiles. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2023, 147, 16–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaal, I.J.; Devlin, J.W.; Hazelbag, M.; Klein Klouwenberg, P.M.C.; van der Kooi, A.W.; Ong, D.S.Y.; Cremer, O.L.; Groenwold, R.H.; Slooter, A.J.C. Benzodiazepine-Associated Delirium in Critically Ill Adults. Intensive Care Med 2015, 41, 2130–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagiakrishnan, K.; Wiens, C.A. An Approach to Drug Induced Delirium in the Elderly. Postgrad Med J 2004, 80, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado, J.R. Neuropathogenesis of Delirium: Review of Current Etiologic Theories and Common Pathways. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013, 21, 1190–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flacker, J.M.; Lipsitz, L.A. Neural Mechanisms of Delirium: Current Hypotheses and Evolving Concepts. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1999, 54, B239–B246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Ge, Q. Inflammatory Biomarkers and Delirium: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Front Aging Neurosci 2023, 15, 1221272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, B. Hyperactive Delirium with Severe Agitation. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2024, 42, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, J.H.; Bieber, E.; Matta, S.E.; Sayde, G.E.; Fedotova, N.O.; deVries, J.; Rafferty, M.; Stern, T.A. Hypoactive Delirium: Differential Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2024, 26, 23f03602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, M.G.; McCusker, J.; Dendukuri, N.; Han, L. Symptoms of Delirium among Elderly Medical Inpatients with or without Dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2002, 14, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, S.K.; Needham, E. Diagnosis of Delirium: A Practical Approach. Pract Neurol 2023, 23, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, V.; O’Neill, P.J.; Cotton, B.A.; Pun, B.T.; Haney, S.; Thompson, J.; Kassebaum, N.; Shintani, A.; Guy, J.; Ely, E.W.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Development of Delirium in Burn Intensive Care Unit Patients. J Burn Care Res 2010, 31, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salluh, J.I.; Soares, M.; Teles, J.M.; Ceraso, D.; Raimondi, N.; Nava, V.S.; Blasquez, P.; Ugarte, S.; Ibanez-Guzman, C.; Centeno, J.V.; et al. Delirium Epidemiology in Critical Care (DECCA): An International Study. Crit Care 2010, 14, R210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosgen, B.K.; Krewulak, K.D.; Stelfox, H.T.; Ely, E.W.; Davidson, J.E.; Fiest, K.M. The Association of Delirium Severity with Patient and Health System Outcomes in Hospitalised Patients: A Systematic Review. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salluh, J.I.F.; Wang, H.; Schneider, E.B.; Nagaraja, N.; Yenokyan, G.; Damluji, A.; Serafim, R.B.; Stevens, R.D. Outcome of Delirium in Critically Ill Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2015, 350, h2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, F.; Gonzalez, F.; Plana, M.N.; Zamora, J.; Quinn, T.J.; Seron, P. Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) for the Diagnosis of Delirium in Adults in Critical Care Settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2023, 11, CD013126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.W.; Skrobik, Y.; Gélinas, C.; Needham, D.M.; Slooter, A.J.C.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Watson, P.L.; Weinhouse, G.L.; Nunnally, M.E.; Rochwerg, B.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2018, 46, e825–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, R.; Corbet, S.; Johnston, C.; Moffitt, E.; Shaw, G.; Quinn, T.J. Test Accuracy of Short Screening Tests for Diagnosis of Delirium or Cognitive Impairment in an Acute Stroke Unit Setting. Stroke 2013, 44, 3078–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellelli, G.; Morandi, A.; Davis, D.H.J.; Mazzola, P.; Turco, R.; Gentile, S.; Ryan, T.; Cash, H.; Guerini, F.; Torpilliesi, T.; et al. Validation of the 4AT, a New Instrument for Rapid Delirium Screening: A Study in 234 Hospitalised Older People. Age Ageing 2014, 43, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, J.; Wand, A.P.F.; Smerdely, P.I.; Hunt, G.E. Validating the 4A’s Test in Screening for Delirium in a Culturally Diverse Geriatric Inpatient Population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017, 32, 1322–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palakshappa, J.A.; Hough, C.L. How We Prevent and Treat Delirium in the ICU. Chest 2021, 160, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, J.M. Quetiapine Fumarate (Seroquel): A New Atypical Antipsychotic. Drugs Today (Barc) 1999, 35, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVane, C.L.; Nemeroff, C.B. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Quetiapine: An Atypical Antipsychotic. Clin Pharmacokinet 2001, 40, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakken, G.V.; Rudberg, I.; Christensen, H.; Molden, E.; Refsum, H.; Hermann, M. Metabolism of Quetiapine by CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 in Presence or Absence of Cytochrome B5. Drug Metab Dispos 2009, 37, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, P. Atypical Antipsychotics: Mechanism of Action. Can J Psychiatry 2002, 47, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefvert, O.; Lundberg, T.; Wieselgren, I.M.; Bergström, M.; Långström, B.; Wiesel, F.; Lindström, L. D(2) and 5HT(2A) Receptor Occupancy of Different Doses of Quetiapine in Schizophrenia: A PET Study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2001, 11, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.R.; Hodle, T.J.; Spinner, H.E. Antipsychotic Initiation in Mechanically Ventilated Patients in a Medical Intensive Care Unit. Am J Pharmacother Pharm Sci 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, T.D.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Carson, S.S.; Schmidt, G.A.; Wright, P.E.; Canonico, A.E.; Pun, B.T.; Thompson, J.L.; Shintani, A.K.; Meltzer, H.Y.; et al. Feasibility, Efficacy, and Safety of Antipsychotics for Intensive Care Unit Delirium: The MIND Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Crit Care Med 2010, 38, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Chiang, C.-H.; Tseng, M.-C.M.; Tam, K.-W.; Loh, E.-W. Effects of Quetiapine on Sleep: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2023, 67, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, M.P.; Hinds, M.; Tayidi, I.; Jeffcoach, D.R.; Corder, J.M.; Hamilton, L.A.; Lawson, C.M.; Bollig, R.W.; Heidel, R.E.; Daley, B.J.; et al. Quetiapine for Delirium Prophylaxis in High-Risk Critically Ill Patients. Surgeon 2021, 19, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawthorne, A.; Delgado, E.; Battle, A.; Norton, C. Quetiapine Twice Daily Versus Bedtime Dosing in the Treatment of ICU Delirium. J Pharm Pract 2023, 8971900231193545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunther, M.; Dopheide, J.A. Antipsychotic Safety in Liver Disease: A Narrative Review and Practical Guide for the Clinician. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry 2023, 64, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieveld, J.N.M.; van der Valk, J.A.; Smeets, I.; Berghmans, E.; Wassenberg, R.; Leroy, P.L.M.N.; Vos, G.D.; van Os, J. Diagnostic Considerations Regarding Pediatric Delirium: A Review and a Proposal for an Algorithm for Pediatric Intensive Care Units. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35, 1843–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieveld, J.N.M. On Pediatric Delirium and the Use of the Pediatric Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Med 2011, 39, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blankespoor, R.J.; Janssen, N.J.J.F.; Wolters, A.M.H.; Van Os, J.; Schieveld, J.N.M. Post-Hoc Revision of the Pediatric Anesthesia Emergence Delirium Rating Scale: Clinical Improvement of a Bedside-Tool? Minerva Anestesiol 2012, 78, 896–900. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, G.; Traube, C.; Kearney, J.; Kelly, D.; Yoon, M.J.; Nash Moyal, W.; Gangopadhyay, M.; Shao, H.; Ward, M.J. Detecting Pediatric Delirium: Development of a Rapid Observational Assessment Tool. Intensive Care Med 2012, 38, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.J.; Breitbart, W.S.; Platt, M.M. A Critique of Instruments and Methods to Detect, Diagnose, and Rate Delirium. J Pain Symptom Manage 1995, 10, 35–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- On the Utility of Diagnostic Instruments for Pediatric Delirium in Critical Illness: An Evaluation of the Pediatric Anesthesia Emergence Delirium Scale, the Delirium Rating Scale 88, and the Delirium Rating Scale-Revised R-98 – PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21567109/ (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- Traube, C.; Silver, G.; Kearney, J.; Patel, A.; Atkinson, T.M.; Yoon, M.J.; Halpert, S.; Augenstein, J.; Sickles, L.E.; Li, C.; et al. Cornell Assessment of Pediatric Delirium: A Valid, Rapid, Observational Tool for Screening Delirium in the PICU*. Crit Care Med 2014, 42, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, R.; López-Herce, J.; Arias, Á.; Del Castillo, J.; Mencía, S. Validity and Reliability of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale in Pediatric Intensive Care Patients: A Multicenter Study. Front Pediatr 2021, 9, 795487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, K.; Kaur, S.; Mauer, E.A.; Gerber, L.M.; Greenwald, B.M.; Silver, G.; Traube, C. BENZODIAZEPINES AND DEVELOPMENT OF DELIRIUM IN CRITICALLY ILL CHILDREN: ESTIMATING THE CAUSAL EFFECT. Crit Care Med 2018, 46, 1486–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, A.; Bashqoy, F.; Santos, L.; Herbsman, J.; Papadopoulos, J.; Saad, A. Quetiapine for the Treatment of Pediatric Delirium. Ann Pharmacother 2023, 57, 1172–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, C.; Witcher, R.; Herrup, E.; Kaur, S.; Mendez-Rico, E.; Silver, G.; Greenwald, B.M.; Traube, C. Evaluation of the Safety of Quetiapine in Treating Delirium in Critically Ill Children: A Retrospective Review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2015, 25, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, C.J.; Engler, M.; Zaki, H.; Crooker, A.; Cabrera, M.; Golden, C.; Whitehill, R.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, K.; Fundora, M.P. The Effect of Antipsychotic Medications on QTc and Delirium in Paediatric Cardiac Patients with ICU Delirium. Cardiol Young 2024, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krøigaard, S.M.; Clemmensen, L.; Tarp, S.; Pagsberg, A.K. A Meta-Analysis of Antipsychotic-Induced Hypo- and Hyperprolactinemia in Children and Adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2022, 32, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-L.; Wu, V.C.-C.; Lee, C.H.; Wu, C.-L.; Chen, H.-M.; Huang, Y.-T.; Chang, S.-H. Incidences, Risk Factors, and Clinical Correlates of Severe QT Prolongation after the Use of Quetiapine or Haloperidol. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, M.; Vieweg, W.V.R.; Howland, R.H.; Kogut, C.; Breden Crouse, E.L.; Koneru, J.N.; Hancox, J.C.; Digby, G.C.; Baranchuk, A.; Deshmukh, A.; et al. Quetiapine, QTc Interval Prolongation, and Torsade de Pointes: A Review of Case Reports. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2014, 4, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, K.M.; DeGrado, J.; Hohlfelder, B.; Szumita, P.M. Evaluation of the Effects of Quetiapine on QTc Prolongation in Critically Ill Patients. J Pharm Pract 2018, 31, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, S.S. Extrapyramidal Symptoms Associated with Quetiapine. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2003, 37, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leucht, S.; Pitschel-Walz, G.; Abraham, D.; Kissling, W. Efficacy and Extrapyramidal Side-Effects of the New Antipsychotics Olanzapine, Quetiapine, Risperidone, and Sertindole Compared to Conventional Antipsychotics and Placebo. A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Schizophr Res 1999, 35, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistraletti, G.; Mantovani, E.S.; Cadringher, P.; Cerri, B.; Corbella, D.; Umbrello, M.; Anania, S.; Andrighi, E.; Barello, S.; Di Carlo, A.; et al. Enteral vs. Intravenous ICU Sedation Management: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2013, 14, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomichek, J.E.; Stollings, J.L.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Chandrasekhar, R.; Ely, E.W.; Girard, T.D. Antipsychotic Prescribing Patterns during and after Critical Illness: A Prospective Cohort Study. Crit Care 2016, 20, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.; Vermassen, J.; Fierens, J.; Peperstraete, H.; Petrovic, M.; Colpaert, K. Discharge from Hospital with Newly Administered Antipsychotics after Intensive Care Unit Delirium - Incidence and Contributing Factors. J Crit Care 2021, 61, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.; Herzig, S.J.; Howell, M.D.; Le, S.H.; Mathew, C.; Kats, J.S.; Stevens, J.P. Antipsychotic Utilization in the Intensive Care Unit and in Transitions of Care. J Crit Care 2016, 33, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.W.; Roberts, R.J.; Fong, J.J.; Skrobik, Y.; Riker, R.R.; Hill, N.S.; Robbins, T.; Garpestad, E. Efficacy and Safety of Quetiapine in Critically Ill Patients with Delirium: A Prospective, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study. Crit Care Med 2010, 38, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.W.; Bhat, S.; Roberts, R.J.; Skrobik, Y. Current Perceptions and Practices Surrounding the Recognition and Treatment of Delirium in the Intensive Care Unit: A Survey of 250 Critical Care Pharmacists from Eight States. Ann Pharmacother 2011, 45, 1217–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneeton, B.; Maneeton, N.; Srisurapanont, M.; Chittawatanarat, K. Quetiapine versus Haloperidol in the Treatment of Delirium: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013, 7, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Patients | Design | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Martinez et al.[8] | 665 ICU patients | Retrospective observational study | The screening rates for RASS and CAM-ICU were below the recommended levels. The administration of antipsychotic medications – mostly quetiapine in this cohort - occurs more frequently than the diagnosis of delirium |

| Sessler et al.[6] | 192 ICU patients | Comparative study | RASS showed a high inter-rater reliability among the entire adult ICU population. Robust correlations between the investigator-assigned RASS and the visual analog scale scores validated the use of RASS across all subgroups within the ICU. The RASS scores documented by individual physicians, nurses, and pharmacists exhibited a strong correlation with the principal investigator’s visual analog scale score. |

| Ely et al.[7] | 290 ICU patients | Prospective cohort study | The RASS represents the first sedation scale validated for its capacity to identify variations in sedation levels over successive days of ICU treatment, in relation to constructs such as consciousness levels and delirium, and it showed a correlation with the dosages of sedative and analgesic medications administered. This study confirmed the reliability and validity of RASS for monitoring sedation status over time. |

| Miranda et al.[42] | 2817 ICU | Cochrane review | This study evaluated CAM-ICU for diagnosing delirium in critical care settings. The test is primarily beneficial for ruling out delirium. However, it may fail to identify a subset of patients with newly developed delirium. Consequently, in scenarios where comprehensive detection of all delirium cases is essential, it may be advisable to either retest or to use the CAM-ICU in conjunction with an additional assessment. |

| Marshall et al.[80] | 164’996 ICU patients | Retrospective observational cohort study | Antipsychotic medications are prescribed to 1 in every 10 patients in the ICU, and their use is correlated with prolonged lengths of stay in both the ICU and the hospital. Patients receiving antipsychotics without any recorded diagnosis of a mental disorder exhibit longer ICU stays, extended hospitalizations, and higher mortality rates in comparison to those with a documented mental disorder. |

| Girard et al.[54] | 101 ICU patients mechanically ventilated | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Neither haloperidol nor ziprasidone significantly shortened the duration of delirium when compared to placebo. Patients across the three treatment groups had a comparable number of days alive without experiencing delirium or coma. |

| Mart et al.[4] | 566 ICU patients | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | In critically ill patients experiencing delirium, neither haloperidol nor ziprasidone demonstrated a significant impact on cognitive, functional, psychological, or quality-of-life outcomes in survivors. |

| Devlin et al.[81] | 36 ICU patients with delirium | Prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | The inclusion of quetiapine with as-needed haloperidol is associated with a more rapid resolution of delirium, decreased levels of agitation, and a higher rate of discharge to home or rehabilitation. Patients receiving quetiapine needed fewer days of as-needed haloperidol. Furthermore, the occurrence of QTc prolongation and extrapyramidal symptoms was comparable between the groups. |

| Zakhary et al.[22] | 100 ICU patients | Randomized controlled | Quetiapine has been shown to be as effective as haloperidol in alleviating the symptoms of hyperactive delirium in critically ill patients, although it does not confer any benefit in terms of mortality. |

| Maneeton et al.[83] | 52 ICU patients with delirium | Prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled | Low doses of quetiapine and haloperidol demonstrate comparable efficacy and safety for managing behavioral disturbances (efficacy, tolerability, total sleep time) in patients with delirium, particularly when combined with environmental modifications. |

| Alghadeer et al.[19] | 47 ICU patients | Retrospective comparative study | The authors found no significant differences in efficacy or adverse effects when comparing the treatment of delirium with quetiapine, haloperidol, risperidone, and olanzapine |

| Wang et al.[72] | 11173 patients, quetiapine vs haloperidol | Multicenter retrospective cohort study | The authors showed that severe QT prolongation was prevalent among patients undergoing treatment with quetiapine or haloperidol. A considerable proportion of these patients were exposed to risk factors associated with QT prolongation, including older age, heart failure, hypokalemia, and the concurrent administration of medications recognized to elevate the risk of torsades des pointes. |

| Dube et al.[74] | 103 ICU patients | Single-center, prospective cohort analysis | There were no reported occurrences of torsades de pointes. QTc prolongation was relatively rare among critically ill patients receiving quetiapine. Patients who were prescribed concomitant medications known to prolong the QTc interval may be at a heightened risk. |

| Tomichek et al.[78] | 500 ICU patients | Single-centre prospective cohort study | The administration of an atypical antipsychotic markedly increased the probability of receiving an antipsychotic prescription at discharge, a practice that should be carefully evaluated during medication reconciliation |

| Lambert et al.[79] | 196 ICU patients | Retrospective observational study | About 20% of patients were released from the hospital while still on antipsychotic medications. Hospital discharge protocols should incorporate strategies for the systematic reduction of antipsychotic dosages and improved monitoring of antipsychotic use during transitions of care. |

| Traube et al.[65] | 111 PICU patients | Validation study | Cornell Assessment of Pediatric Delirium (CAPD) has shown high accuracy in diagnosing delirium, and notably 31% of the diagnosis were in children less than 2 years old, and 27% of the diagnosis assessments were in children who were developmentally delayed. |

| Cronin et al.[21] | 846 PICU patients | A single-center retrospective cohort study | Patients administered haloperidol or quetiapine did not demonstrate any short-term improvement in delirium screening scores following the initiation of treatment, relative to untreated patients matched by propensity scores. Additionally, clinical outcomes for those receiving treatment were either not improved or were worse. |

| Caballero et al.[68] | 37 PICU patients | Single-center observational study | Quetiapine did not produce a statistically significant effect on the dosages of deliriogenic medications. There were negligible alterations in the QTc interval, and no dysrhythmias were detected. |

| John et al.[70] | 139 PICU patients | Retrospective observational study | The QTc interval did not exhibit a statistically significant alteration following the administration of antipsychotics, whereas an improvement in the CAPD score was observed. Atypical antipsychotic medications can be used safely without causing substantial QTc prolongation and are effective in treating delirium. |

| Joyce et al.[69] | 50 PICU patients | Retrospective observational study | Authors proposed a potential dosing regimen initiating therapy at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg/day, divided into three doses. For breakthrough agitation, additional doses of 0.5 mg/kg were administered on top of the regular every-8-hour schedule with a usual maximum dosage limit of 6 mg/kg/day. In this cohort, the short-term administration of quetiapine for the management of delirium seems to be safe, with no significant adverse events reported. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).