Submitted:

27 September 2024

Posted:

30 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Control (C)

- Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus (AMF)

- Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR)

- Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus+ Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (AMF+PGPR)

- Salt stress (S)

- Salt stress+Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus (S+AMF)

- Salt stress+Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (S+PGPR)

- Salt stress+Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus+Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (S+AMF+PGPR)

2.1. Parameters Investigated in Experiment

2.1.1. Plant Growth Parameters

2.1.2. Ion Leakage (%)

2.1.3. Leaf Relative Water Content (RWC)

2.1.4. Determination of Leaf Osmotic Potential (MPa)

2.1.5. Leaf Water Potential (MPa)

2.1.6. Leaf Elemental Analysis

2.1.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

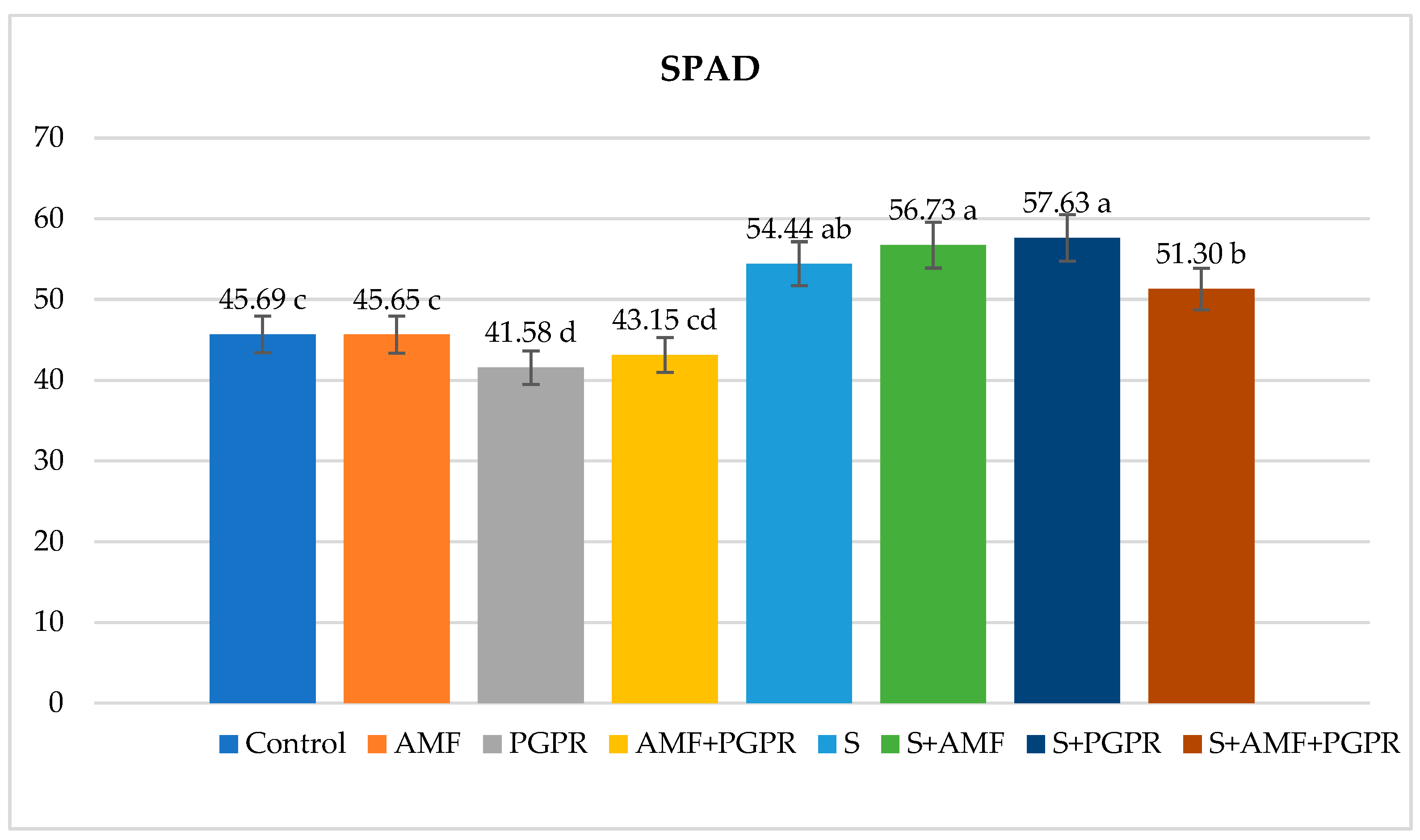

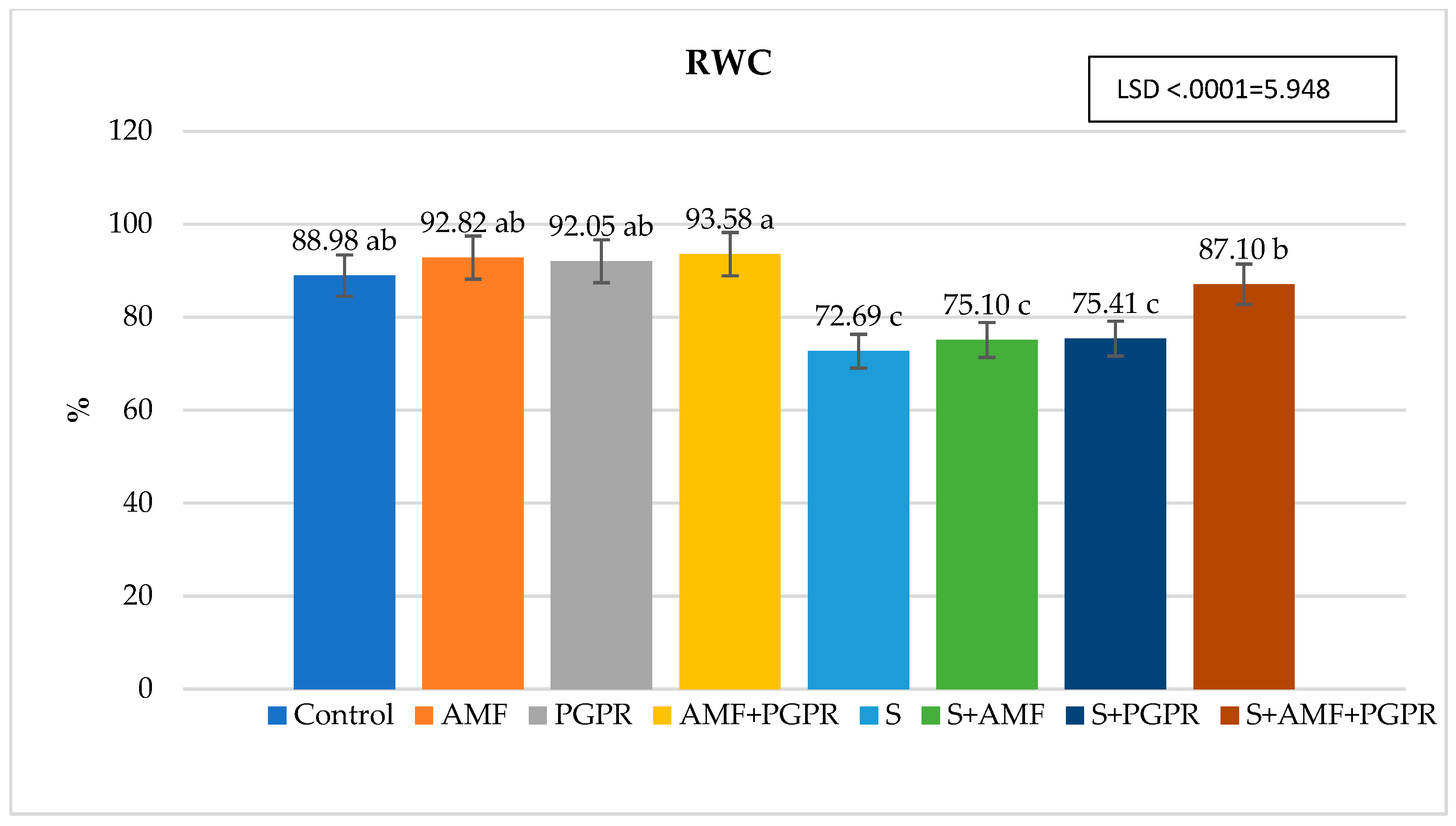

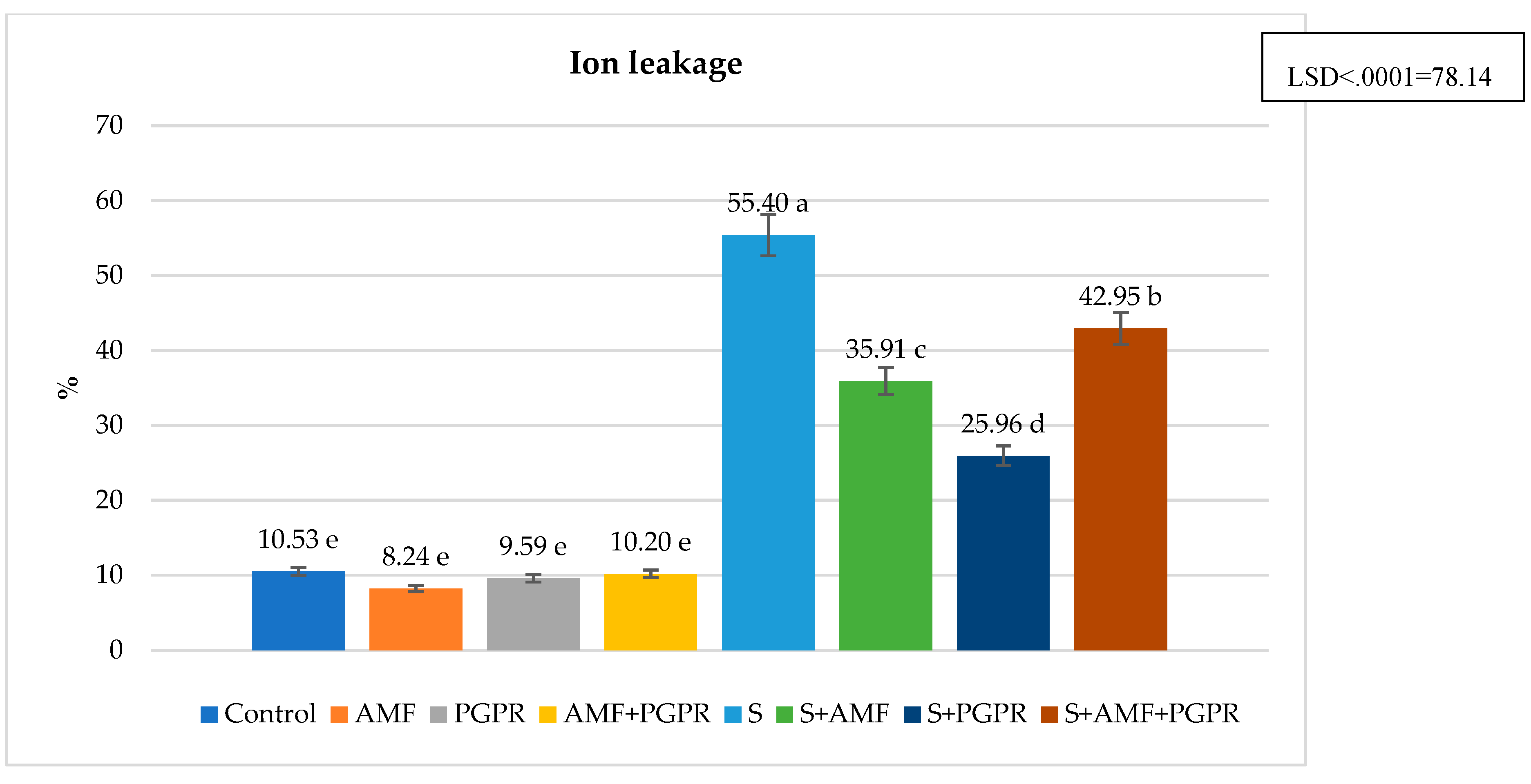

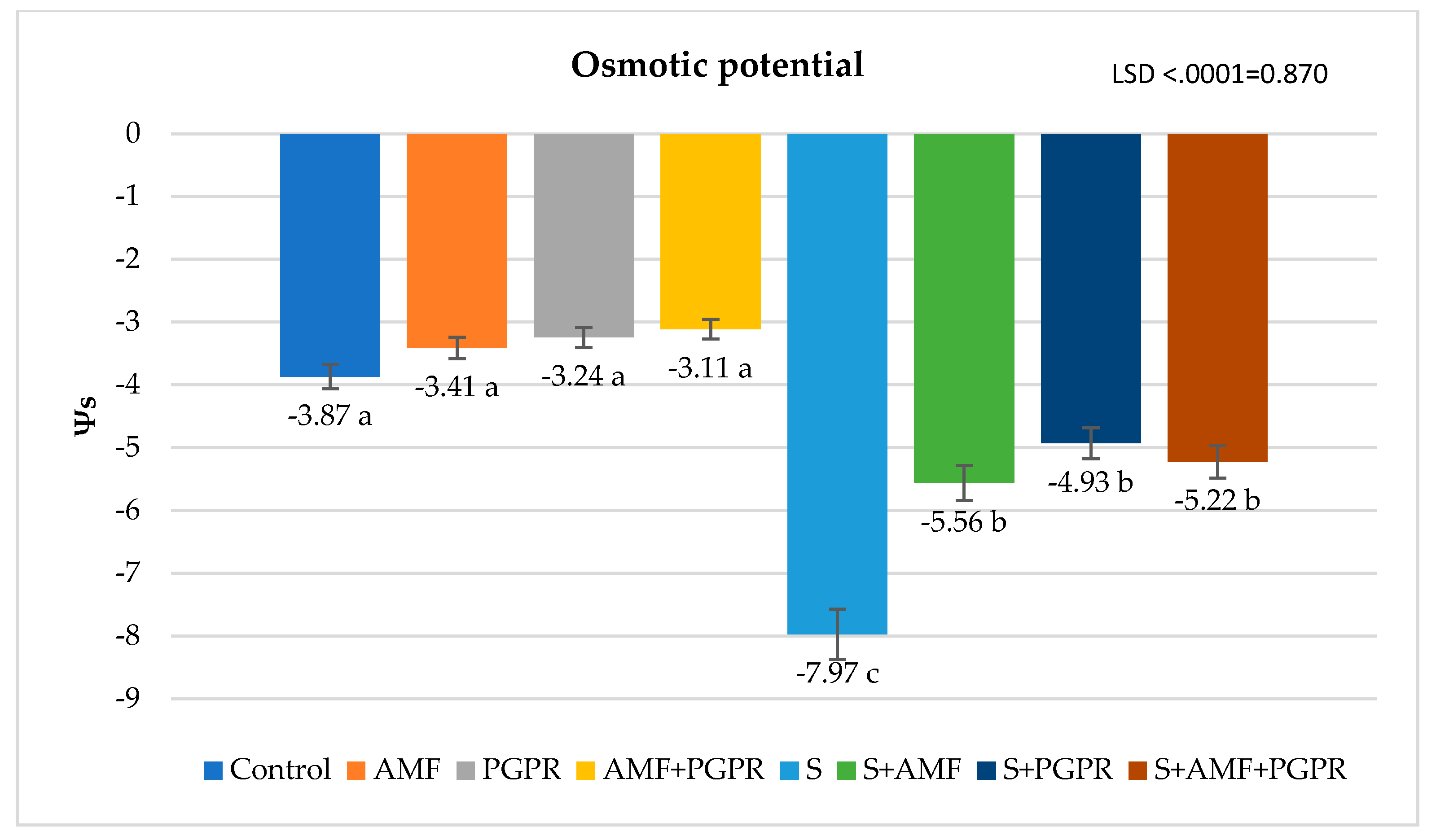

3.1. Physiological Parameters

3.2. Mineral Nutrient Uptake

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aydın, F.; Sarptaş, H. İklim değişikliğinin bitki yetiştiriciliğine etkisi: model bitkiler ile Türkiye durumu. PAJES. 2018, 24, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alveroğlu, L. The effects of some bacteria (Serratia marcescens and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia) and potassium nitrate applications to salt tolerance in pepper plants. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Eskişehir Osmangazi Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Eskişehir, 2014.

- Gül, V. Stres Terminolojisi. Bitkilerde Abiyotik Ve Biyotik Stres Yönetimi. Iksad Publications: 2022.

- Kopecká, R.; Kameniarová, M.; Černý, M.; Brzobohatý, B.; Novák, J. Abiotic stress in crop production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(7), 6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Sabagh, A.; Islam, M.S.; Skalicky, M.; Ali Raza, M.; Singh, K.; Anwar Hossain, M.; Arshad, A. Salinity stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in the changing climate: Adaptation and management strategies. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 661932. [Google Scholar]

- Çolak, G.; Keser, Ö.; Çatak, E. Tuz stresine maruz bırakılan raphanus sativus l.'de embriyonik yaprak (kotiledon) gelişimleri. EJONS, 2020, 4(16), 987-997.

- Dhiman, J.; Prasher, S.O.; El Sayed, E.; Patel, R.M.; Nzediegwu, C.; Mawof, A. Effect of hydrogel based soil amendments on yield and growth of wastewater irrigated potato and spinach grown in a sandy soil. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 23, 101730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamidov, M.; Ishchanov, J.; Hamidov, A.; Dönmez, C.; Djumaboev, K. Assessment of soil salinity changes under the climate change in the Khorezm region, Uzbekistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19(14), 8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Bano, A.; Khan, N. Climate Change and Salinity Effects on Crops and Chemical Communication Between Plants and Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganisms Under Stress. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 618092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, C.H.; Tunçtürk, M.; Tunçtürk, R. Tuz stresi koşullarında yetiştirilen soya (Glycine max L.) bitkisinde bazı fizyolojik ve biyokimyasal değişimler üzerine salisilik asit uygulamalarının etkileri. Ege Univ. Ziraat Fak. Derg. 2023, 60(1), 91-101.

- Gürsoy, M. An overview of the effects of salt stress on plant development. In Proceedings of the 9th International Zeugma Conference on Scientific Research, Zeugma, Turkey; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, M. Ö. Karnitin uygulamalarının tuz stresi altında biber ve hıyar tohumlarının çimlenme ve çıkış performansları üzerine olan etkilerinin incelenmesi. MSc Thesis, Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Bahçe Bitkileri Anabilim Dalı, Kahramanmaraş, Turkey, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A.A.; Söylemez, S.; Sarhan, T.Z. Effect of biofertilizers, seaweed extract and inorganic fertilizer on growth and yield of lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. longifolia L.). Harran Tarım ve Gıda Bilimleri Dergisi 2022, 26(1), 60-71.

- Nolan, T.M.; Vukašinović, N.; Liu, D.; Russinova, E.; Yin, Y. Brassinosteroids: Multidimensional Regulators of Plant Growth, Development, and Stress Responses. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhou, H.; Ma, C.; Wang, P. Regulation of plant responses to salt stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, M.; Wani, S.P. Rhizobacterial-plant interactions: strategies ensuring plant growth promotion under drought and salinity stress. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 231, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, P.P.; Kumar, A. Interaction of plant growth promoting bacteria with tomato under abiotic stress: a review. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 267, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Rajkumar, M.; Luo, Y.M.; Freitas, H. Inoculation of endophytic bacteria on host and non-host plants – effects on plant growth and Ni uptake. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 195, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Shahzad, B.; Rehman, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Landi, M.; Zheng, B. Response of phenylpropanoid pathway and the role of polyphenols in plants under abiotic stress. Molecules 2019, 24(13), 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azeem, M.; Pirjan, K.; Qasim, M.; Mahmood, A.; Javed, T.; Muhammad, H.; Rahimi, M. Salinity stress improves antioxidant potential by modulating physio-biochemical responses in Moringa oleifera Lam. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, N.; Pal, N.; Dey, S.; Mandal, A. Characterizations of surfactant synthesized from palm oil and its application in enhanced oil recovery. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 81, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naamala, J.; Subramanian, S.; Msimbira, L.A.; Smith, D.L. Effect of NaCl stress on exoproteome profiles of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens EB2003A and Lactobacillus helveticus EL2006H. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1206152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Freschi, G.; Rouphael, Y.; Pascale, S.; Lucini, L. The differential modulation of secondary metabolism induced by a protein hydrolysate and a seaweed extract in tomato plants under salinity. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dere, S. Organic substances application to enhance abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Iksad Yayinevi: 2020; pp. 1.

- Alkaç, O.S.; Tuncel, M.E.; Dinçer, E.; Donat, A. The effect of compost, bacteria, and mycorrhiza applications on the phytochemical contents of edible tulip petals. Turkish J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 11(3), 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Qin, C.; Ahanger, M.A.; Raza, S.; Khan, M.I.; Ashraf, M.; Zhang, L. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant growth regulation: implications in abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbaraj, M.P. Plant-microbe interactions in alleviating abiotic stress—A mini review. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 667903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, Q.; Xiukang, W.; Haider, F.U.; Kučerik, J.; Mumtaz, M.Z.; Holatko, J.; Mustafa, A. Rhizosphere bacteria in plant growth promotion, biocontrol, and bioremediation of contaminated sites: A comprehensive review of effects and mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22(19), 10529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedayo, A.A.; Babalola, O.O. Fungi That Promote Plant Growth in the Rhizosphere Boost Crop Growth. J. Fungus. 2023, 9, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, M.A.; Islam, S.; Gani, G.; Dar, Z.M.; Masood, A.; Baligah, S.H. AM fungi as a potential biofertilizer for abiotic stress management. in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in agriculture-new insights. IntechOpen. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcel, R.; Aroca, R.; Ruíz-Lozano, J.M. Salinity stress alleviation using arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, N.; Meng, S.; Wu, F.; Liu, T. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) enhance the tolerance of Euonymus maackii Rupr. at a moderate level of salinity. PLoS One 2020, 15(4), e0231497. [Google Scholar]

- Evelin, H.; Devi, T.S.; Gupta, S.; Kapoor, R. Mitigation of salinity stress in plants by arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis: current understanding and new challenges. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekaran, M.; Chanratana, M.; Kim, K.; Seshadri, S.; Sa, T. Impact of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on photosynthesis, water status, and gas exchange of plants under salt stress—a meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastogeer, K.M.; Zahan, M.I.; Tahjib-Ul-Arif, M.; Akter, M.A.; Okazaki, S. Plant salinity tolerance conferred by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and associated mechanisms: a meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 588550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliu, A.; Sallaku, G.; Rewald, B. AMF inoculation enhances growth and improves the nutrient uptake rates of transplanted, salt-stressed tomato seedlings. Sustainability. 2015, 7, 15967–15981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.; Li, Q.S.; Ding, W.Y.; Dong, L.W.; Deng, M.; Chen, J.H.; Wu, Q.S. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculation impacts expression of aquaporins and salt overly sensitive genes and enhances tolerance of salt stress in tomato. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunlu, H. 2020. The Effects of mycorrhiza and rhizobacteria application on growth and some physiological parameters of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) under salt stress. J. Agric. Fac. Ege Univ. 2020, 57, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Radhakrishnan, R.; Al-Arjani, A.B.F.; Aldehaish, H.A.; Egamberdieva, D.; Abd_Allah, E.F. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi regulate the oxidative system, hormones, and ionic equilibrium to trigger salt stress tolerance in Cucumis sativus L. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25(6), 1102–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A.; Mittra, B. Effects of inoculation with stress-adapted arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus deserticola on growth of Solanum melongena L. and Sorghum sudanese Staph. seedlings under salinity and heavy metal stress conditions. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2013, 59(2), 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulhadi, S.A.A. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on seedling development of edible seed pumpkin under salty soil conditions. Master’s Thesis, The Graduate School of Natural and Applied Science of Selçuk University, 2017; 35 pp.

- Sharma, N.; Aggarwal, A.; Yadav, K. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance growth, physiological parameters and yield of salt stressed Phaseolus mungo (L.) Hepper. Eur. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 7(1), 22-27.

- Wang, H.; An, T.; Huang, D.; Liu, R.; Xu, B.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses alleviating salt stress in maize is associated with a decline in root-to-leaf gradient of Na+/K+ ratio. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santander, C.; Sanhueza, M.; Olave, J.; Borie, F.; Valentine, A.; Cornejo, P. Arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization promotes the tolerance to salt stress in lettuce plants through an efficient modification of ionic balance. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2019, 19, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouhaddou, R.; Ben-Laouane, R.; Slimani, A.; Boutasknit, A.; Anli, M.; Oufdou, K.; Meddich, A. Autochthonous biostimulants as a promising biological tool to promote lettuce growth and development under salinity conditions. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022a, 16(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouhaddou, R.; Ben-Laouane, R.; Lahlali, R.; Anli, M.; Ikan, C.; Boutasknit, A.; Meddich, A. Application of indigenous rhizospheric microorganisms and local compost as enhancers of lettuce growth, development, and salt stress tolerance. Microorganisms 2022b, 10(8), 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, D.; Ansari, M.W.; Sahoo, R.K.; Tuteja, N. Biofertilizers function as key players in sustainable agriculture by improving soil fertility, plant tolerance, and crop productivity. Microb. Cell Fact. 2014, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H.; Emami, S.; Alikhani, H.A. Potassium solubilizing bacteria (KSB): Mechanisms, promotion of plant growth, and future prospects—a review. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2017, 17(4), 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, R.; Rokem, J. S.; Ilangumaran, G.; Lamont, J.; Praslickova, D.; Ricci, E.; Smith, D.L. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: context, mechanisms of action, and roadmap to commercialization of biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Godínez, L.J.; Aguirre-Noyola, J.L.; Martínez-Romero, E.; Arteaga-Garibay, R.I.; Ireta-Moreno, J.; Ruvalcaba-Gómez, J.M. A Look at Plant-Growth-Promoting Bacteria. Plants 2023, 12(8), 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, N.; Asif, R.; Ayyub, S.; Salman, S.; Shafique, F.; Ali, Q.; Malik, A. Role of rhizobacteria in phytoremediation of heavy metals. Biol. Clin. Sci. Res. J. 2020, 2020(1).

- Ahemad, M.; Khan, M.S. Productivity of greengram in tebuconazole–stressed soil, by using a tolerant and plant growth-promoting Bradyrhizobium sp. MRM6 strain. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2012, 34, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenova, N.; Tsigoriyna, L.; Arsov, A.; Petrov, K.; Petrova, P. Microbial detoxification of residual pesticides in fermented foods: current status and prospects. Foods. 2023, 12, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egamberdieva, D.; Wirth, S.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D.; Mishra, J.; Arora, N.K. Salt-tolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for enhancing crop productivity of saline soils. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Gaurav, A.K.; Srivastava, S.; Verma, J.P. Plant growth-promoting bacteria: biological tools for the mitigation of salinity stress in plants. Front. Microbiol. 2020a, 11, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirry, N.; Kouchou, A.; Laghmari, G.; Lemjereb, M.; Hnadi, H.; Amrani, K.; El Ghachtouli, N. Improved salinity tolerance of Medicago sativa and soil enzyme activities by PGPR. Biocatalysis Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Takishita, Y.; Zhou, G.; Smith, D.L. Plant associated rhizobacteria for biocontrol and plant growth enhancement. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 634796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhojiya, A.A.; Joshi, H.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Srivastava, A.K.; Pathak, V.V.; Pandey, V.C.; Jain, D. Screening and optimization of zinc removal potential in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-HMR1 and its plant growth-promoting attributes. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 108(3), 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, L.A.; Santos, C.H.B.; Frezarin, E.T.; Sales, L.R.; Rigobelo, E.C. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria for Sustainable Agricultural Production. Microorganisms 2023, 11(4), 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanse, P.; Kumar, M.; Singh, L.; Awasthi, M.K.; Qureshi, A. Role of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria in boosting the phytoremediation of stressed soils: Opportunities, challenges, and prospects. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 134954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vocciante, M.; Grifoni, M.; Fusini, D.; Petruzzelli, G.; Franchi, E. The role of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) in mitigating plant’s environmental stresses. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Tahmish, F.; Mishra, J.; Mishra, I.; Verma, S.; Verma, R.; Vermad, M.; Bhattacharya, A.; Verma, P.; Mishra, P.; Bharti, C. Halo-tolerant plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for improving productivity and remediation of saline soils. J. Adv. Res. 2020b, 26, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıyer, T.; Çiftci, H.N. Effect of different storage periods on quality properties in pepper (Capsicum annuum L. cv. Oskar F1). COMU J. Agric. Faculty 2022, 10(1), 137-142.

- López-Serrano, L.; Calatayud, Á.; López-Galarza, S.; Serrano, R.; Bueso, E. Uncovering salt tolerance mechanisms in pepper plants: a physiological and transcriptomic approach. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgan, H.Y.; Yilmaz, M.; Dere, S.; Ikiz, B.; Gruda, N.S. Bio-Fertilizers Reduced the Need for Mineral Fertilizers in Soilless-Grown Capia Pepper. Horticulturae 2023, 9(2), 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, F.G.; Lieth, J.H. Irrigation control in hydroponics. In Hydroponic Production of Vegetables and Ornamentals; Savvas, D., Passam, H., Eds.; Embryo Publications: Athens, Greece, 2002; pp. 263–298. [Google Scholar]

- Dere, S. Domateste besin özellikleri ve kalitenin kuraklığa dayanıklılıkla arttırılması. Doctoral Thesis, Çukurova Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Adana, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, M. Topraksız biber yetiştiriciliğinde mikoriza ve bakteri biyogübreleri kullanılarak mineral gübrelerin azaltılması. MSc Thesis, Çukurova University, Adana, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgan, H.Y.; Kuşvuran, Ş.; Abak, K.; Sarı, N. Screening and saving of local vegege tarımsal araştırma enstitüsübles for their resistance to drought and salinity. UNDP Project Final Report, 2010.

- Altuntas, O.; Dasgan, H.Y.; Akhoundnejad, Y.; Kutsal, I.K. Does Silicon Increase the tolerance of a sensıtıve pepper genotype to salt stress? Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus. 2020, 19, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dere, S. Kuraklık stresi koşullarında bakteri uygulamasının domates bitkileri üzerine etkileri. Türk Doğa ve Fen Dergisi 2021, 10(1), 52-62.

- Bayram, M.; Dasgan, H.Y. (2020). Useful parameters and correlations for screening of tomatoes to salt tolerance under field conditions. Russ. Agric. Sci. 2020, 46, 451–458. [Google Scholar]

- Altuntas, O.; Dasgan, H.Y.; Akhoundnejad, Y. Silicon-induced salinity tolerance improves photosynthesis, leaf water status, membrane stability, and growth in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Hortic. Sci. 2018, 53, 1820–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, K.A.A.; Mazrou, Y.S.; Hafez, Y.M. Silicon foliar application mitigates salt stress in sweet pepper plants by enhancing water status, photosynthesis, antioxidant enzyme activity, and fruit yield. Plants 2020, 9, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivam, V.; Packiaraj, G.; Subiramani, S.; Govindarajan, S.; Kumar, G.P.; Kalamani, V.; Vemuri, L.; Narayanasamy, J. Evaluation of seagrass liquid extract on salt stress alleviation in tomato plants. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2017, 16, 172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Akhoundnejad, Y.; Baran, S. Boosting drought resistance in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) with the aid of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and key phytohormones. Hortic. Sci. 2023, 58, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar]

- Coban, A.; Akhoundnejad, Y.; Dere, S.; Dasgan, H.Y. Impact of salt-tolerant rootstock on the enhancement of sensitive tomato plant responses to salinity. HortScience 2020, 55(1), 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daşgan, H.Y.; Bayram, M.; Kuşvuran, S.; Çoban, G.A.; Akhoundnejad, Y. Screening of tomatoes for their resistance to salinity and drought stress. Glob. J. Biol. Agric. Health Sci. 2018, 8(24).

- Hao, S.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. A review on plant responses to salt stress and their mechanisms of salt resistance. Horticulturae 2021, 7(6), Art. no: 132.

- Yavas, I.; Ilker, E. Changes in photosynthesis and phytohormone levels in plants exposed to environmental stress conditions. Agric. 2020, 267, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Chaoxing, H. Does inoculation with Glomus mosseae improve salt tolerance in pepper plants? . J. Plant. Growth. Regul. 2014, 33, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, N.B.; Shawky, B.T. Protective effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ) plants exposed to salinity. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 98, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badem, A.; Söylemez, S. Effects of nitric oxide and silicon application on growth and productivity of pepper under salinity stress. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34(6), 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayavarapu, V.B.; Padmavathi, T. Effect of Bacillus sp. and Glomus monosporum on growth and antioxidant activity of bell pepper (Capsicum annuum) under salinity stress. J. Glob. Agric. Ecol. 2016, 6(1), 57-67.

- Kadan, H.Y.; Üzal, Ö. Tuz stresi ve geri kazanım sürecinde biberin (Capsicum annuum L.) bitki gelişimi ve iyon alımındaki değişimler. J. Inst. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10(3), 1476-1485.

- Yaşar, F.; Yaşar, Ö. Tuz stresi altındaki çarliston biber çeşidinin gelişim performansı. ISPEC J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 6(4), 835–841. [Google Scholar]

- Kaymak, M.A. Grafen oksit uygulamalarının biber (Capsicum annuum L.)'de tuz stresine karşı etkileri. MSc Thesis, Atatürk Üniversitesi, Erzurum, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Trung, N.T.; Hieu, H.V.; Thuan, N.H. Screening of strong 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylate deaminase producing bacteria for improving the salinity tolerance of cowpea. Appl. Microbiol.: Open Access.

- Safronova, V.I.; Stepanok, V.V.; Engqvist, G.L.; Alekseyev, Y.V.; Belimov, A.A. Root-associated bacteria containing 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase improve growth and nutrient uptake by pea genotypes cultivated in cadmium supplemented soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2006, 42(3), 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amri, S.M. Mitigation of salinity stress of pepper (Capsicum annuum l.) by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus, glomus constrictum. Appl Ecol Environ Res. 2019. 17, 9965-9978. [CrossRef]

- Sevgi, B.; Leblebici, S. Tuz stresinin bitkiler üzerindeki etkileri ve geliştirilen tolerans mekanizmaları. Düzce Üniversitesi Bilim ve Teknoloji Dergisi 2023, 11(3), 1498-1516.

- Munns, R. Comparative physiology of salt and water stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25(2), 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, B.; Fahad, S.; Tanveer, M.; Saud, S.; Khan, I.A. Plant responses and tolerance to salt stress. In Approaches for Enhancing Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Florida, USA, 2019; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Parvin, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Nahar, K.; Mohsin, S.M.; Fujita, M. Comparative physiological and biochemical changes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) under salt stress and recovery: Role of antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 350. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta-Motos, J.; Ortuño, M.; Bernal-Vicente, A.; Díaz Vivancos, P.; Sánchez-Blanco, M.; Hernández, J. Plant responses to salt stress: Adaptive mechanisms. Agronomy 2017, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, K.A.A.; Hafez, Y.M.; El-Afry, M.M.; Tantawy, D.S.; Alshaal, T. Effect of some osmoregulators on photosynthesis, lipid peroxidation, antioxidative capacity, and productivity of barley (Hordeum vulgare L. ) under water deficit stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 30199–30211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicek, N.; Çakirlar, H. The effect of salinity on some physiological parameters in two maize cultivars. Bulg. J. Plant Physiol. 2002, 28(1-2), 66-74.

- Ghoulam, C.; Foursy, A.; Fares, K. Effects of salt stress on growth, inorganic ions and proline accumulation in relation to osmotic adjustment in five sugar beet cultivars. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2002, 47(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tayeb, M.A. Response of barley grains to the interactive effect of salinity and salicylic acid. Plant Growth Regul. 2005, 45, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, H.; Abak, K.; Eker, S. Anti-oxidative responses of salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes grown under salt stress. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2012, 87(4), 360-366.

- Çekiç, F.Ö.; Ünyayar, S.; Ortaş, İ. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculation on biochemical parameters in Capsicum annuum grown under long term salt stress. Turkish J. Bot. 2012, 36, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, H.; Çimrin, K.M.; Turan, M.; Güneş, A.; Ozlu, E. Response of mycorrhiza-inoculated pepper and amino acids to salt treatment at different ratios. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2019, 50(3), 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Read, D. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.E.; Smith, F.A. Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizas in plant nutrition and growth: New paradigms from cellular to ecosystem scales. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2011, 62, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, S.M.; Ahmad, M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Javaid, A.; Ashraf, M. The role of mycorrhizae and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) in improving crop productivity under stressful environments. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32(2), 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelin, H.; Kapoor, R.; Giri, B. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in alleviation of salt stress: A review. Ann. Bot. 2009, 104(7), 1263–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, S.B. Photoinhibition of photosynthesis induced by visible light. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1984, 35(1), 15–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.; Tang, M.; Chen, H.; Yang, B.; Zhang, F.; Huang, Y. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizae on photosynthesis and water status of maize plants under salt stress. Mycorrhiza 2008, 18(6), 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Jia-Dong, H.E.; Qiu-Dan, N.I.; Qiang-Sheng, W.U.; Ying-Ning, Z.O.U. Enhancement of drought tolerance in trifoliate orange by mycorrhiza: changes in root sucrose and proline metabolisms. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agro-botanici Cluj-Napoca 2018, 46(1), 270–276. [CrossRef]

- Altuntas, O.; Dasgan, H.Y.; Akhoundnejad, Y.; Nas, Y. Unlocking the potential of pepper plants under salt stress: mycorrhizal effects on physiological parameters related to plant growth and gas exchange across tolerant and sensitive genotypes. Plants 2024, 13(10), 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzanza, B.; Marais, D.; Soundy, P. Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal inoculation and biochar amendment on growth and yield of tomato. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2012, 14, 965–969. [Google Scholar]

- Flexas, J.; Bota, J.; Galmes, J.; Medrano, H.; Ribas-Carbó, M. Keeping a positive carbon balance under adverse conditions: responses of photosynthesis and respiration to water stress. Physiologia Plantarum 2006, 127(3), 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Flexas, J.; Pinheiro, C. Photosynthesis under drought and salt stress: regulation mechanisms from whole plant to cell. Annals of Botany 2009, 103(4), 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, B.; Mukerji, K.G. Mycorrhizal inoculant alleviates salt stress in Sesbania aegyptiaca and Sesbania grandiflora under field conditions: evidence for reduced sodium and improved magnesium uptake. Mycorrhiza 2004, 14(5), 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusvuran, S.; Dasgan, H.Y.; Abak, K. Responses of okra genotypes to drought stress: VII. Vegetable. In Agricultura Sempozium, 2008, pp. 329-333.

- İzci, B. Pamukta (Gossypium hirsutum L.) farklı tuz konsantrasyonlarının in vitro koşullarda fotosentetik pigmentler üzerine etkisi. Alinteri J. Agric. Sci. 2009, 17(2), 7-13.

- Demirel, K.; Genç, L.; Mendeş, M.; Saçan, M.; Kızıl, Ü. Estimation of growth curve parameters for pepper (Capsicum annuum cv. Kapija) under deficit irrigation conditions. Ege Üniv. Ziraat Fak. Derg. 2012, 49(1), 37-43.

- Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Tullio, M.; Rivera, C.M.; Rea, E. Alleviation of salt stress by arbuscular mycorrhizal in zucchini plants grown at low and high phosphorus concentration. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2008, 44(3), 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Ashraf, M.; Sönmez, Ö.; Aydemir, S.; Tuna, A.L.; Cullu, M.A. The influence of arbuscular mycorrhizal colonisation on key growth parameters and fruit yield of pepper plants grown at high salinity. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 121(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlıdağ, H.; Yıldırım, E.; Turan, M.; Pehluvan, M.; Dönmez, F. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria mitigate deleterious effects of salt stress on strawberry plants (Fragaria × ananassa). HortScience 2013, 48(5), 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badizi, B.M.; Zarandi, M.M. Some physiological and growth parameters of Pistachio vera L. under coinoculation with endomycorrhizae and Bacillus subtilis in response to salinity. Bull. Env. Pharmacol. Life Sci. 2016, 1, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Koç, A.; Balcı, G.; Ertürk, Y.; Keles, H.; Bakoglu, N.; Ercisli, S. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizae and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on proline, membrane permeability and growth of strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa) under salt stress. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2016, 89, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Latef, A.A. Changes of antioxidative enzymes in salinity tolerance among different wheat cultivars. Cereal Res. Commun. 2010, 38, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, H.; Sanon, K.B.; Le Roux, C.; Duponnois, R.; Traoré, A.S. Improvement of cowpea productivity by rhizobial and mycorrhizal inoculation in Burkina Faso. Symbiosis 2018, 74(2), 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Lv, W.; Yang, Y. Molecular mechanisms of plant responses to salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 934877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Mu, X.; Shao, H.; Wang, H.; Brestic, M. Global plant-responding mechanisms to salt stress: Physiological and molecular levels and implications in biotechnology. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2015, 35(4), 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, M.; Saxena, J.; Nema, R.; Singh, D.; Gupta, A. Phytochemistry of medicinal plants. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2013, 1(6), 168–182. [Google Scholar]

- Zulfiqar, F.; Akram, N.A.; Ashraf, M. Osmoprotection in plants under abiotic stresses: New insights into a classical phenomenon. Planta 2020, 251(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, H.; Gomaa, E. Effect of plant growth promoting Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas fluorescens on growth and pigment composition of radish plants (Raphanus sativus) under NaCl stress. Photosynthetica 2012, 50, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, M.; Yildirim, E.; Turan, M. Ameliorating effects of hydrogen sulfide on growth, physiological and biochemical characteristics of eggplant seedlings under salt stress. South Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 143, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Esawi, M.A.; Alaraidh, I.A.; Alsahli, A.A.; Alamri, S.A.; Ali, H.M.; Alayafi, A.A. Bacillus firmus (SW5) augments salt tolerance in soybean (Glycine max L.) by modulating root system architecture, antioxidant defense systems and stress-responsive genes expression. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018a, 132, 375–384. [CrossRef]

- El-Esawi, M.A.; Alaraidh, I.A.; Alsahli, A.A.; Alzahrani, S.A.; Ali, H.M.; Alayafi, A.A.; et al. Serratia liquefaciens KM4 improves salt stress tolerance in maize by regulating redox potential, ion homeostasis, leaf gas exchange and stress-related gene expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018b, 19, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Asgha, H.N.; Arshad, M. The combined application of rhizobial strains and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria improves growth and productivity of mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) under salt-stressed conditions. Ann. Microbiol. 2012, 62, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Bora, M. Değişik vejetasyon dönemlerine kadar uygulanan farklı tuz konsantrasyonlarının biberde meydana getirdiği fizyolojik, morfolojik ve kimyasal değişikliklerin belirlenmesi. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Namık Kemal Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Tekirdağ, 2015.

- Hedrich, R.; Shabala, S. Stomata in a saline world. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 46, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, S.; Mishra, S. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi and salinity on seedling growth, solute accumulation and mycorrhizal dependency of Jatropha curcas L. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2010, 29, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharnagl, K.; Sanchez, V.; Von Wettberg, E. The impact of salinity on mycorrhizal colonization of a rare legume, Galactia smallii, in South Florida pine rocklands. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kader, M.A.; Lindberg, S. Cytosolic calcium and pH signaling in plants under salinity stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5(3), 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Kim, W.Y.; Yun, D.J. A new insight of salt stress signaling in plants. Molecules Cells 2016, 39(6), Art. no: 447.

- Al-Karaki, G.N.; Hammad, R.; Rusan, M. Response of two tomato cultivars differing in salt tolerance to inoculation with mycorrhizal fungi under salt stress. Mycorrhiza 2001, 11, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuna, A.L.; Eroğlu, B. Tuz stresi altındaki biber (Capsicum annuum L.) bitkisinde bazı organik ve inorganik bileşiklerin antioksidatif sisteme etkileri. Anadolu J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 32(1), 121-131. [CrossRef]

- Güneş, A.; Inal, A.; Alpaslan, M. Effect of salinity on stomatal resistance, proline, and mineral composition of pepper. J. Plant Nutr. 1996, 19(2), 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ballesta, M.C.; Martínez, V.; Carvajal, M. Osmotic adjustment, water relations and gas exchange in pepper plants grown under NaCl or KCl. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2004, 52(2), 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lycoskoufis, I.H.; Savvas, D.; Mavrogianopoulos, G. Growth, gas exchange, and nutrient status in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) grown in recirculating nutrient solution as affected by salinity imposed to half of the root system. Sci. Hortic. 2005, 106(2), 147-161. [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.G. Tuz Stresi Altındaki Acı ve Çarliston Biber Çeşitlerinin Genç-Orta ve Yaşlı Yapraklarında İyon Hareketleri. MSc Thesis, Van Yüzüncü Yıl Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Bahçe Bitkileri Anabilim Dalı, Van, Turkey, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Muchate, N.S.; Nikalje, G.C.; Rajurkar, N.S.; Suprasanna, P.; Nikam, T.D. Plant salt stress: Adaptive responses, tolerance mechanisms and bioengineering for salt tolerance. Bot. Rev. 2016, 82(4), 371–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, P.; Singh, S.; Singh, R.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M. Effect of salinity stress on plants and its tolerance strategies: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22(6), 4056–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. Plant salt tolerance and Na⁺ sensing and transport. Crop J. 2018, 6(3), 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusvuran, S. Relationships between physiological mechanisms of tolerance to drought and salinity in melons. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Horticulture, Institute of Natural and Applied Sciences, Çukurova University, Adana, Turkey, 2010; p. 356. [Google Scholar]

- Esin, F. Bazı çilek çeşitlerinde NaCl uygulamasının bitki gelişimi ve iyon içeriği üzerine etkisi. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Yüzüncü Yıl Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Van, 2007.

- Kusvuran, Ş.; Ellialtıoğlu, Ş.; Abak, K.; Yaşar, F. Bazı kavun (Cucumis sp.) genotiplerinin tuz stresine tepkileri. Ankara Üniversitesi Biyoteknoloji Enstitüsü, 2002; Proje No: 2002-58, Ankara.

- Del Amor, F.M.; Cuadra-Crespo, F. Plant growth-promoting bacteria as a tool to improve salinity tolerance in sweet pepper. Funct. Plant Biol. 2011, 39(1), 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geilfus, C.M. Chloride: From nutrient to toxicant. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59(6), 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | P | K | Ca | Mg | Fe | Mn | Zn | B | Cu | Mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100-239 | 40-81 | 96-370 | 150-250 | 50-92 | 5-10 | 1.97 | 0.25 | 0.7 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Application | Plant height (cm) | Plant diameter (mm) | Number of leaf per plant (number) | Number of bifurcations per plant (number) | Plant fresh weight (g/plant) | Leaf area (cm2/plant) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 37.25 ab | 6.37 a | 45.00 a | 5.25 bc | 48.38 ab | 1450.75 b |

| AMF | 39.50 a | 6.52 a | 37.25 b | 5.75 ab | 47.94 ab | 1553.25 ab |

| PGPR | 37.75 ab | 6.50 a | 37.25 b | 7.00 a | 59.44 a | 1837.25 a |

| AMF+PGPR | 36.25 b | 5.44 b | 34.25 b | 6.00 ab | 39.11 b | 1436.25 b |

| Salt | 24.25 d | 4.53 d | 10.00 d | 2.00 e | 13.61 c | 382.75 c |

| Salt+AMF | 29.5 c | 5.10 bc | 16.75 c | 4.00 cd | 18.74 c | 580.00 c |

| Salt+PGPR | 26.5 cd | 5.09 bc | 14.75 cd | 4.50 bcd | 14.03 c | 450.00 c |

| Salt+AMF+PGPR | 27.25 cd | 4.78 cd | 11.00 d | 3.00 de | 11.81 c | 409.25 c |

| LSD0.05 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| p | 3.017 | 0.402 | 4.963 | 1.616 | 13.677 | 361.422 |

| Application | Ca | Mg | K | Na | Cl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.058 a | 1.126 de | 9.506 a | 0.29 c | 1.42 d |

| AMF | 0.966 b | 1.184 bcde | 9.023 bc | 0.23 c | 1.30 d |

| PGPR | 0.712 c | 1.139 cde | 9.231 ab | 0.22 c | 1.66 c |

| AMF+PGPR | 0.699 c | 1.100 e | 8.568 cd | 0.31 c | 1.49 cd |

| Salt | 0.983 ab | 1.334 a | 7.777 e | 3.05 a | 2.69 a |

| Salt+AMF | 0.978 b | 1.236 abcd | 7.726 e | 2.79 b | 2.27 b |

| Salt+PGPR | 0.937 b | 1.305 ab | 7.832 e | 3.00 a | 2.53 a |

| Salt+AMF+PGPR | 0.973 b | 1.263 abc | 8.174 de | 2.99 a | 2.63 a |

| LSD0.05 | <.0001 | 0.0067 | <.0001 | 0.82 | 0.68 |

| P | 0.080 | 0.128 | 0.487 | 2.99 | 2.63 |

| Application | Cu | Mn | Fe | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 14.75 bc | 87.68 f | 100.50 a | 131.67 cd |

| AMF | 13.50 cd | 101.33 ef | 97.50 ab | 125.25 d |

| PGPR | 13.50 cd | 119.67 d | 89.00 cd | 138.50 c |

| AMF+PGPR | 12.25 d | 109.33 de | 86.75 d | 129.33 d |

| Salt | 14.75 bc | 188.33 b | 101.75 a | 171.67 a |

| Salt+AMF | 18.00 a | 161.00 c | 97.00 abc | 160.33 b |

| Salt+PGPR | 18.00 a | 218.67 a | 98.50 ab | 171.00 a |

| Salt+AMF+PGPR | 16.75 ab | 185.50 b | 90.50 bcd | 174.67 a |

| LSD0.05 | 0.0003 | <.0001 | 0.0048 | <.0001 |

| P | 2.431 | 14.788 | 8.073 | 8.460 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).