Introduction

The evolution of the immune system has undergone significant changes over approximately 800 million years, transitioning from primitive innate immune responses in early metazoans to the complex adaptive immune systems seen in vertebrates [

1]. Key developments including the emergence of immune cells capable of phagocytes could have occurred around 700 million years ago. Trichoplax adherens which belong to the Placozoa phylum, has diverged more than 700 year ago. Recently they have been shown to possess macrophage-like cells that can perform phagocytosis. Macrophages-like cells have been also reported in other

Porifera, Ctenophora, and Cnidaria [

2]. While neutrophils themselves are unique to vertebrates, invertebrates have immune cells with similar roles in pathogen recognition and response. For example, hemocytes in insects perform functions analogous to those of neutrophils, such as phagocytosis and producing antimicrobial substances [

3]. However, the adpative immuen system with its antigen-specific seems to have diverged with the advent of lymphocytes in jawed vertebrates approximately 500 million years ago, which allowed recognition of species based on their antigens. The diversification of immune mechanisms continued with the appearance of T and B cells, enabling sophisticated recognition of pathogens [

4]. This evolutionary trajectory highlights the interplay between innate and adaptive immunity, shaped by environmental pressures and the need for enhanced host defense strategies against diverse pathogens.

The GFI1 gene family, which includes GFI1A and GFI1B, plays a critical role in regulating immune cell differentiation and function within the innate and the adaptive immune system [

5,

6]. GFI1A is particularly important for the development of T helper cells and neutrophils, influencing their differentiation and function during immune responses [

7]. Specifically, mice deleted for Gfi1 lack neutrophils [

6]. It is also known to regulate genes involved in T cell activation and cytokine production, thereby shaping the immune landscape [

7]. GFI1B, while sharing structural similarities, has distinct roles in hematopoiesis and may influence the development of other immune cell lineages [

8]. Together, GFI1A and GFI1B illustrate the functional diversity within the GFI1 gene family, contributing to the complexity of immune regulation across different species.

The evolutionary history of GFI1A and GFI1B remains largely unknown, with critical gaps in understanding their structural and functional adaptations. Both genes encode proteins featuring multiple C2H2-type zinc finger domains, essential for DNA binding and transcriptional regulation, and play pivotal roles in immune cell differentiation [

9,

10]. Both genes also include an N-terminal repressor domain of 20 aminoacids known as SNAG [

11]. However, several key aspects require further investigation, including patterns of positive selection, type II divergence, and the identification of crucial structural motifs necessary for their regulatory functions. Furthermore, the role of the less characterized middle region loctaed between the SNAG sequence and the C2H2 sequences has not been yet identfied [

5].These unanswered questions underscore the need for comprehensive studies to elucidate the evolutionary dynamics and functional significance of the GFI1 gene family across different species.

In our study, we conducted a comprehensive investigation into the evolutionary history of the GFI1 gene family, employing methods such as phylogenetic tree reconstruction, positive selection analysis, type II divergence assessment, motif searching, and non-homology-based functional ontology analysis. Our findings reveal important insights into the divergence and conservation of GFI1A and GFI1B across various species, highlighting structural motifs that may play critical roles in their functions. Additionally, we identified patterns of evolutionary adaptation that inform our understanding of the functional implications of these genes within the immune system.

Materials and Methods

Database Search

In this study, our primary focus was investigating the evolutionary origins of the GFI1 pathway. Given the diverse nature and extensive evolutionary history of the genes under investigation, we employed a strategy based on sequence alignment of their respective proteins [

12,

13]. We conducted a detailed analysis of GFI1 presence across various taxonomic classes, spanning over 500 million years and encompassing more than 200 protein sequences, including Mammalia, Actinopterygii, Insecta, Arachnida, Gastropoda, Bivalvia, Cephalopoda, Anthozoa, and Placozoa. To maintain consistency and comparability across our analysis, we conducted BLASTP searches utilizing human protein families against the aforementioned proteomes. In order to ascertain robust results, we employed the longest transcript homolog for each species during our investigation. To establish candidate proteins, we set a stringent threshold, only accepting sequences with E values below 1e

–10 [

14]. Additionally, we implemented a filtering step by comparing conserved domains within each identified protein against the query human protein sequences. By adopting this comprehensive approach and standardizing our taxonomic categorization, we aim to provide a clear basis for comparison across different evolutionary time frames. This ensures that our analysis accurately captures the evolutionary trajectories of the GFI1 pathway within the context of its respective taxa.

Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

The phylogenetic analysis was conducted in two stages [

15]. Initially, we aligned amino acid sequences using MAFFT with the iterative refinement method (FFT-NS-i) [

16]. To ensure precise representation of complex evolutionary relationships within our dataset, we utilized IQ-Tree [

17]. This advanced tool allowed us to explore a variety of substitution models, including GTR, HKY, and JC. IQ-Tree’s comprehensive analysis enabled us to rigorously compare and evaluate the performance of different models using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Based on these evaluations, we identified the model that best explained the observed sequence variations and accurately reflected the underlying evolutionary processes.

Positive Selection Analysis

We employed a maximum likelihood approach to explore whether GFI1 underwent positive selection during evolution [

13]. First, we back-translated the corresponding complementary DNAs (cDNAs) using the EMBOSS Backtranseq tool and aligned them based on their codon sequences [

18]. We then examined patterns of positive selection in GIF1 using Datamonkey. server [

19]. In particular, we calculated the substitution rate ratio (ω), which represents the ratio of nonsynonymous (dN) to synonymous (dS) mutations. We conducted four levels of analysis: (i) basic (global) selection, (ii) branch-specific selection, (iii) (iv) site-specific selection models [

20]. Statistical significance was assessed using a likelihood ratio test (LRT).

Functional Divergence Estimation

We performed an analysis of Type II functional divergence between GIF1 and its homologs using the DIVERGE software. This analysis aimed to detect any shifts in amino acid properties, such as charge, size, or hydropathy [

21](Gu and Velden 2002). In this analysis, GIF1 was grouped according to its presence in different vertebrate and invertebrate classes [

21,

22].

Ancestral Sequence reconstruction

For ancestral sequence reconstruction, we used MEGA to align GFI1 homologs from vertebrates and invertebrates using MAFFT with the iterative refinement method (FFT-NS-i) [

23]. Ancestral sequences were inferred via maximum likelihood methods, focusing on conserved regions to minimize the influence of rapidly evolving domains. To identify the earliest diverging homologs, we conducted BLASTp searches using the ancestral sequence against NCBI’s non-redundant database, with an E-value cutoff of 1e

–10, followed by HMMER searches to detect distant homolog.

Linear Motifs Search

To explore the evolution-function relationship between GFI1 and its homologs, we searched for linear motifs within the protein sequences. Linear motifs are short sequences of amino acids that may act as protein interaction sites. This search was conducted using the ELM server (

http://elm.eu.org/) with a motif significance threshold set to 100 [

24].

Non-Homology Functional Prediction

To validate our findings, we used two non-homology-based techniques for predicting the functions of GFI1. First, we employed DeepGO, which predicts protein functions using neural networks and gene network connections [

25].

Results

GFI1 evolution history and structural conservation.

Our study reveals that GFI1 likely diverged during the emergence of early metazoans, around 600 million years ago in species like Trichoplax, and is present in various invertebrates such as mollusks, Hydra, and Drosophila melanogaster. We did not observe the same genome duplication events in these invertebrates or lampreys as seen in vertebrates. Instead, the GFI1 genes from invertebrates and lampreys clustered together as orthologs of the vertebrate GFI1 genes in our phylogenetic analysis. Approximately 450–500 million years ago, GFI1 underwent the 2R (two rounds of genome duplication) event in vertebrates during the evolution of bony and cartilaginous fish. This event led to the formation of the vertebrate paralogs gfi1a and gfi1b, which formed distinct clusters in our tree. Nonetheless, we found that the main structure of GFI1 includes repeated ZnF_C2H2 domains across both vertebrate and invertebrate sequences, as well as the SNAG domain, although the middle segment of the gene exhibits high variability.

Ancestral Sequence reconstruction

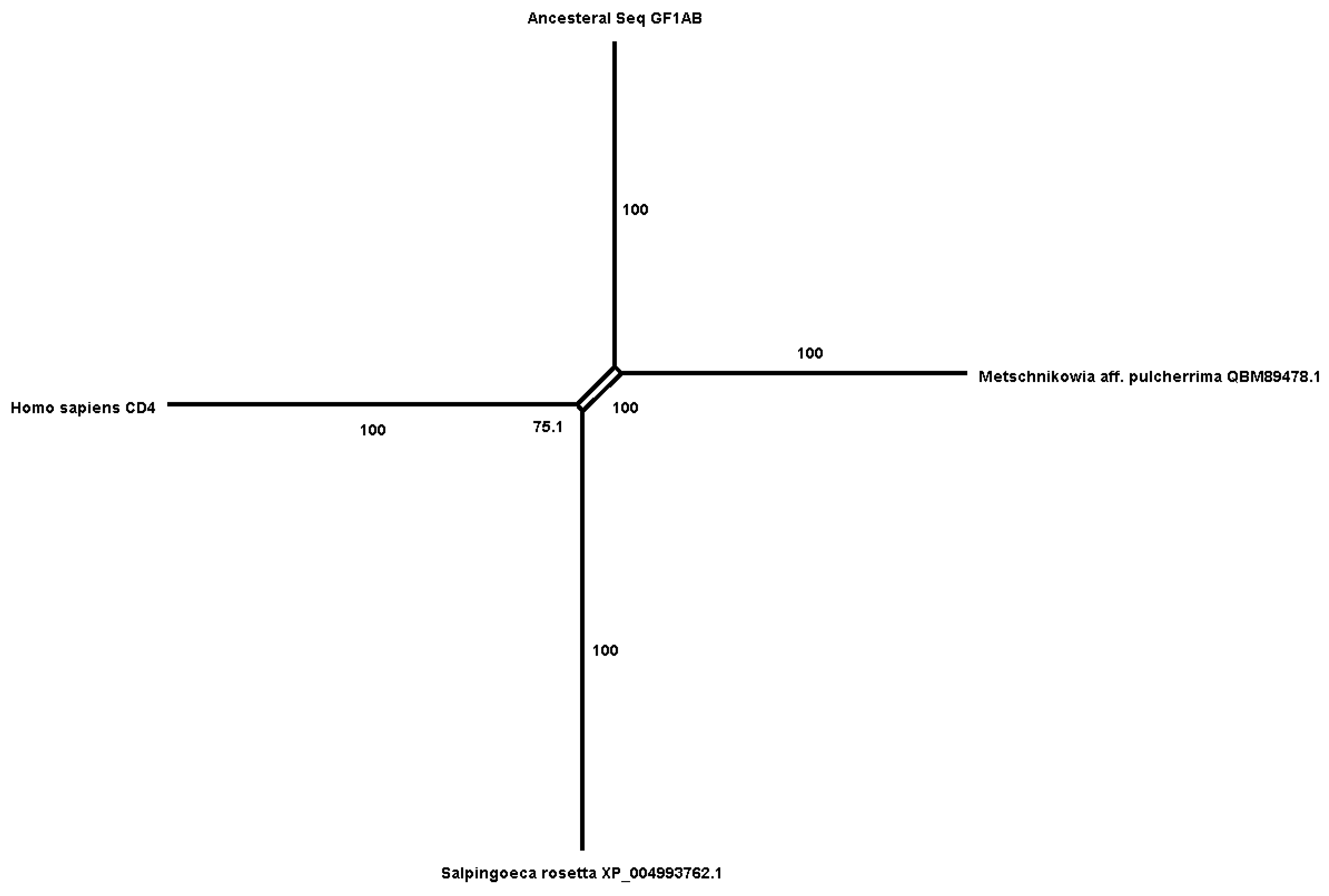

We reconstructed the ancestral sequence of GIF1 homologs found in vertebrates and invertebrates using MEGA, and then employed BLASTp and HMM to identify the earliest diverging homolog to the ancestral sequence. We discovered a homolog, a "zinc finger protein," in Choanoflagellates (Salpingoeca rosetta), as well as a C2H2-type zinc finger protein in fungi, specifically yeast (e.g., Metschnikowia aff. pulcherrima). All three (ancesteral, Salpingoeca rosetta Metschnikowia aff. pulcherrima contained multiple C2H2-type zinc finger domains. Taken together, our results suggest that the GIF1 homolog, characterized by C2H2-type zinc finger domains, may have originated in a common ancestor of choanoflagellates, fungi, and metazoans.

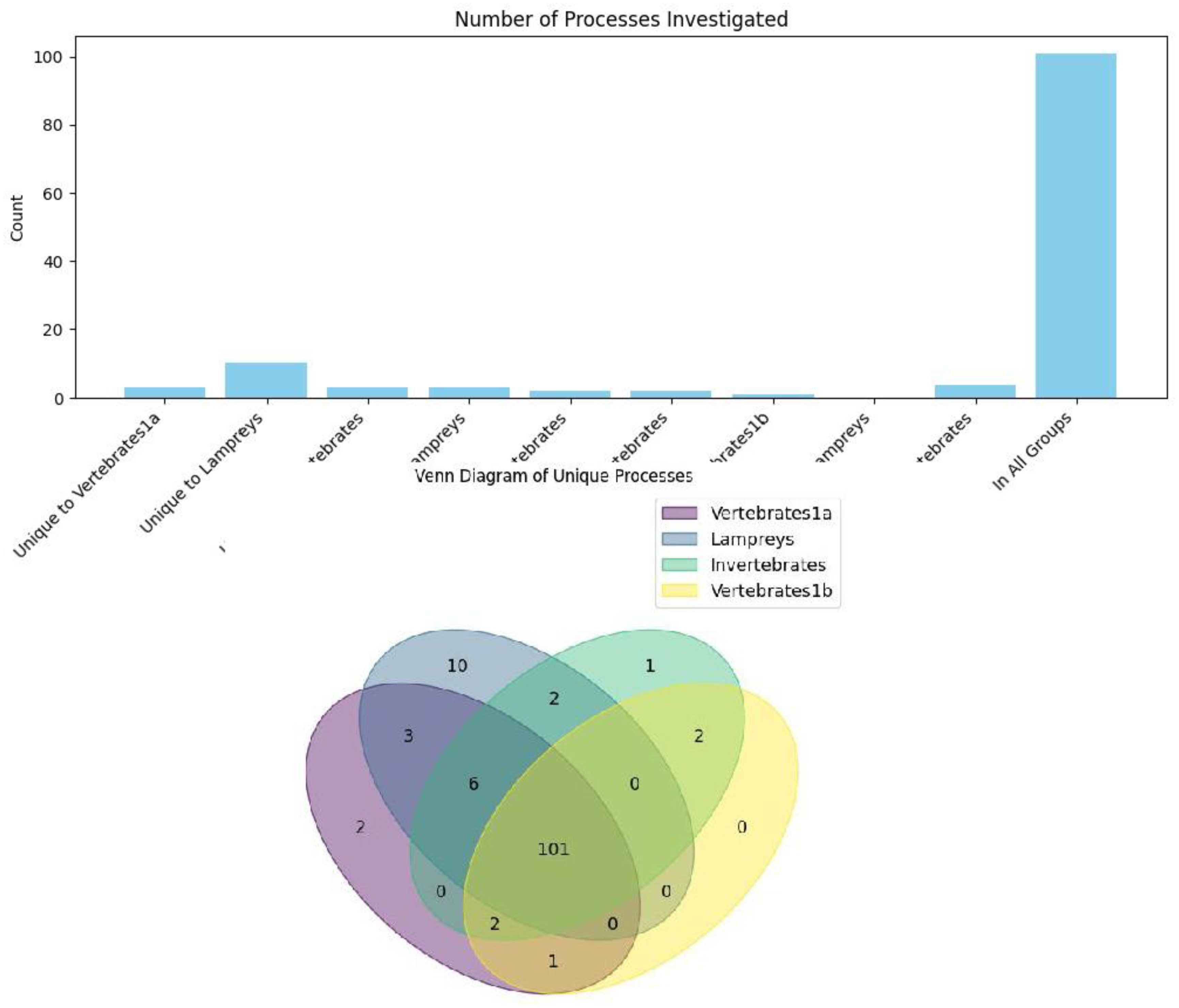

Non-Homolog-Based Functional Ontology of GIF1A

Our results show that GFI1A and GFI1B functions are highly conserved. We performed a Venn diagram analysis of DeepGO terms for each of the groups investigated—GFI1A (vertebrates), GFI1B (vertebrates), lampreys, and invertebrates. We found that the majority of the functional ontology terms identified by DeepGO were present across all groups. Interestingly, GFI1A was predicted to have a role in the response to oxygen-containing compounds, while lampreys exhibited various predicted terms related to signal transduction, such as the positive regulation of cell differentiation. However, upon manual inspection, we judged that these terms were generic, as this particular function is already well-established for GFI1A in vertebrates (Figure 4A and 4B).

Positive selection

We used Branch-site Unrestricted Statistical Test for Episodic Diversification (Busted) to check for episodic diversifying selection. Based on the likelihood ratio test, there is evidence of episodic diversifying selection in this dataset (p=0.000). aBSREL found evidence of episodic diversifying selection on 24 out of 35 branches in your phylogeny. A total of 35 branches were formally tested for diversifying selection. Significance was assessed using the Likelihood Ratio Test at a threshold of p ≤ 0.05, after correcting for multiple testing. Significance and number of rate categories inferred at each branch are provided in the detailed results table (supplementary file 2). We also employed MEM to find sites that have evolved under positive selection, our method identfied 176 sites with p-value threshold p ≤ 0.05 (supplementary file 3).

Functional Divergence

Overall, we did not observe a high degree of functional divergence between (i) vertebrate GFI1A and the invertebrate species investigated. Using DIVERGE 3.0, we identified potential Type II functional divergence sites with a cutoff value of 0.5. At position 549, invertebrates had S/E, while vertebrates had K. At position 574, invertebrates had K/T/V, and GFI1A had T. At position 609, invertebrates had Q/E/T, and GFI1A had I. At position 680, invertebrates had V/Q/L, and vertebrates had V. At position 705, invertebrates had A/S, while vertebrates had G. Finally, at position 715, invertebrates had A/S, while vertebrates had G. These findings suggest that the core functions of the proteins are largely conserved across these groups, with only minor divergences that may point to specialized adaptations in vertebrates and invertebrates. (ii) In a comparison between vertebrate GFI1B and GFI1A, we found only one location of potential Type II divergence at position 362, known as YSWS/FSED. This indicates minimal divergence between these proteins in vertebrates. (iii) In the third analysis, a comparison between vertebrate GFI1B and invertebrate species revealed further divergence. At position 549, GFI1B had H, while invertebrates had S/E. At position 574, GFI1B had T, while invertebrates had K/T/V. At position 596, GFI1B had T/M/L, while invertebrates had R. At position 609, GFI1B had M, while invertebrates had Q/E/T. At position 715, GFI1B had G, while invertebrates had A/S. Finally, at position 733, GFI1B had K, while invertebrates had L/S/T/R.

Motif search

We identified the ADSTS motif, which corresponds to the SPOP-binding consensus, exclusively in humans and chimpanzees GF11A, with no detectable presence in the platypus. Upon further investigation, we focused on this motif and discovered that mice possess a slightly modified variant, ADSTLS. Notably, the platypus has completely lost this motif, and it is absent in fish, Xenopus (frog), lampreys, and invertebrates. These findings suggest that the SPOP-binding consensus motif has evolved specifically in higher vertebrates, particularly within mammals, to fulfill distinct regulatory functions in the context of cellular signaling and gene regulation. We also identfied the motif FEDFW which was shown before to play a role in recruitment of neutrophils through enabling conformational change of the receptor of ligands of NPA2. Interestingly, we located the motif EPLRP only in higher vertebrtes (humans and Chimp) GFI1B. EPLRP has been implicated as a Separase cleavage site, best known in sister chromatid separation. We also found the motif LKREPELE which is Medium length variant of the KEPE motif which is found superposed on some SUMO sites (supplementary file 4).

Discussion

In our study, we traced the evolutionary history of the GFI1 gene family, revealing that it diverged as early as Trichoplax adhaerens, suggesting a foundational role in the evolution of immune-related functions across various taxa. We reconstructed the ancestral sequence of GFI1 homologs found in vertebrates and invertebrates using MEGA, and through BLASTp and HMM analyses, we identified the earliest diverging homolog to this ancestral sequence (

Figure 1). Notably, we discovered a homolog characterized as a "zinc finger protein" in Choanoflagellates (Salpingoeca rosetta), along with a C2H2-type zinc finger protein in fungi, specifically yeast (e.g., Metschnikowia aff. pulcherrima) (

Figure 2). All three sequences—ancestral, Salpingoeca rosetta, and Metschnikowia aff. pulcherrima—contained multiple C2H2-type zinc finger domains. These findings suggest that the GFI1 homolog, distinguished by C2H2-type zinc finger domains, may have originated in a common ancestor shared by choanoflagellates, fungi, and metazoans. Furthermore, our observation that GFI1 underwent the two rounds of genome duplication (2R) during the emergence of bony and cartilaginous fish, approximately 450 million years ago, highlights the gene’s significance in the evolutionary transition to more complex vertebrate immune systems. Notably, this duplication was not observed in lampreys, which possess only a single homolog, indicating a divergent evolutionary trajectory within jawless vertebrates. The presence of two GFI1 homologs in other aquatic vertebrates emphasizes the adaptive advantages conferred by gene duplication in enhancing immune responses. Overall, our findings underscore the evolutionary dynamics of GFI1, suggesting that while the gene has conserved key structural features, its functional roles may have diversified significantly throughout vertebrate evolution.

Our findings illustrate the balance between evolutionary conservation and adaptive divergence in the GFI1 gene family, emphasizing both structural stability and functional innovation across different species. The evidence of episodic diversifying selection, as indicated by the Branch-site Unrestricted Statistical Test for Episodic Diversification (BUSTED), reveals significant selection pressure on 24 out of 35 branches in our phylogeny (p=0.000), suggesting that certain lineages of GFI1 have adapted to specific environmental or functional challenges. In conjunction, our assessment of functional divergence using DIVERGE 3.0 indicates that core functions of GFI1A remain largely conserved between vertebrates and invertebrates, with only minor differences at specific positions—such as S/E in invertebrates versus K in vertebrates at position 549. Comparisons between vertebrate GFI1B and GFI1A show minimal divergence, with just one potential Type II divergence site at position 362. However, a greater degree of divergence is observed between vertebrate GFI1B and invertebrates, indicating distinct evolutionary adaptations; for example, GFI1B shows “H” at position 549 while invertebrates have S/E. Overall, these results highlight the complex interplay between conservation and adaptation in the GFI1 gene family across diverse taxa.

We identified structural motifs that could have emerged specifically in GIF1A to support its novel functions in upper vertebrates, including humans and chimpanzees. Whereas the peptide sequences of the SNAG and the C2H2 domains are highly conserved among GFIA and GFIB as well as between different species [

11]. The middle regions are highly variable [

5,

8]. We identfied severla motifs within this regions that could be playing a role in novel functional emergence. These motifs include the SPOP-binding motif, which appears crucial for GIF1A’s regulatory function in Th1 cells. This motif facilitates the interaction between GIF1 and SPOP, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, enabling the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of GIF1 [

26]. This process is essential for maintaining appropriate levels of GIF1 activity, which influences the production of key cytokines like IFN-γ and TNF-α that drive Th1 responses. By regulating GIF1, the SPOP-binding motif ensures that cytokine production and T cell differentiation occur within optimal ranges, potentially preventing excessive inflammatory responses. In lower vertebrates, where this motif is absent, regulatory mechanisms may differ significantly, highlighting an evolutionary adaptation in higher vertebrates to fine-tune immune responses in complex environments. Additionally, our results indicate that GFI1A possesses the motif FEDFW, which is also found in CXCR-2, suggesting a potential role in neutrophil recruitment during inflammation. Low concentrations of neutrophil-activating peptide-2 (NAP-2) attract neutrophils from the periphery via CXCR-2, while higher concentrations can lead to receptor downregulation, modulating the migratory response [

27]. The FEDFW motif in CXCR-2 may facilitate this process by inducing conformational changes in the receptor or through steric hindrance. Given that GFI1A shares this motif, it raises intriguing questions about its potential involvement in similar mechanisms, inviting further exploration of redundancy, as GFI1A’s presence may indicate it could functionally mimic CXCR-2 in interacting with NAP-2, necessitating a deeper understanding of the roles each plays in neutrophil recruitment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study highlights the evolutionary significance and functional diversity of the GFI1 gene family, revealing key adaptations that enhance immune responses in vertebrates. The identification of novel structural motifs in GIF1A, particularly the SPOP-binding and FEDFW motifs, underscores their potential roles in regulating cytokine production and neutrophil recruitment, emphasizing the need for further exploration of their functions in immune mechanisms. Overall, these findings contribute to our understanding of how GFI1 has evolved to meet the challenges of complex environments in higher vertebrates.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Hirano, M.; Das, S.; Guo, P.; Cooper, M.D. The Evolution of Adaptive Immunity in Vertebrates. In Advances in Immunology; 2011; pp. 125–157. [CrossRef]

- Mayorova, T.D.; Hammar, K.; Jung, J.H.; Aronova, M.A.; Zhang, G.; Winters, C.A.; Reese, T.S.; Smith, C.L. Placozoan fiber cells: mediators of innate immunity and participants in wound healing. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Browne, N.; Heelan, M.; Kavanagh, K. An analysis of the structural and functional similarities of insect hemocytes and mammalian phagocytes. Virulence 2013, 4, 597–603. [CrossRef]

- Bhaumik, S.; Łazarczyk, M.; Kubick, N.; Klimovich, P.; Gurba, A.; Paszkiewicz, J.; Teodorowicz, P.; Kocki, T.; Horbańczuk, J.O.; Manda, G.; et al. Investigation of the Molecular Evolution of Treg Suppression Mechanisms Indicates a Convergent Origin. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 628–648. [CrossRef]

- Möröy, T.; Vassen, L.; Wilkes, B.; Khandanpour, C. From cytopenia to leukemia: the role of Gfi1 and Gfi1b in blood formation. Blood 2015, 126, 2561–2569. [CrossRef]

- Kazanjian, A.; Gross, E.A.; Grimes, H.L. The growth factor independence-1 transcription factor: New functions and new insights. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2006, 59, 85–97. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, J.; Maruyama, S.; Tamauchi, H.; Kuwahara, M.; Horiuchi, M.; Mizuki, M.; Ochi, M.; Sawasaki, T.; Zhu, J.; Yasukawa, M.; et al. Gfi1, a transcriptional repressor, inhibits the induction of the T helper type 1 programme in activated CD4 T cells. Immunology 2016, 147, 476–487. [CrossRef]

- Anguita, E.; Candel, F.J.; Chaparro, A.; Roldán-Etcheverry, J.J. Transcription Factor GFI1B in Health and Disease. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 54. [CrossRef]

- Meseguer, A.; Årman, F.; Fornes, O.; Molina-Fernández, R.; Bonet, J.; Fernandez-Fuentes, N.; Oliva, B. On the prediction of DNA-binding preferences of C2H2-ZF domains using structural models: application on human CTCF. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2020, 2, lqaa046. [CrossRef]

- Fraszczak, J.; Möröy, T. The Transcription Factors GFI1 and GFI1B as Modulators of the Innate and Acquired Immune Response. In Advances in Immunology; 2021; Vol. 149. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.; Ayyanathan, K. Snail/Gfi-1 (SNAG) family zinc finger proteins in transcription regulation, chromatin dynamics, cell signaling, development, and disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2012, 24, 123–131. [CrossRef]

- Mickael, M.; Łazarczyk, M.; Kubick, N.; Gurba, A.; Kocki, T.; Horbańczuk, J.O.; Atanasov, A.G.; Sacharczuk, M.; Religa, P. FEZF2 and AIRE1: An Evolutionary Trade-off in the Elimination of Auto-reactive T Cells in the Thymus. J. Mol. Evol. 2024, 92, 72–86. [CrossRef]

- Kubick, N.; Klimovich, P.; Flournoy, P.H.; Bieńkowska, I.; Łazarczyk, M.; Sacharczuk, M.; Bhaumik, S.; Mickael, M.-E.; Basu, R. Interleukins and Interleukin Receptors Evolutionary History and Origin in Relation to CD4+ T Cell Evolution. Genes 2021, 12, 813. [CrossRef]

- Kubick, N.; Paszkiewicz, J.; Bieńkowska, I.; Ławiński, M.; Horbańczuk, J.O.; Sacharczuk, M.; Mickael, M.E. Investigation of Mutated in Colorectal Cancer (MCC) Gene Family Evolution History Indicates a Putative Role in Th17/Treg Differentiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11940. [CrossRef]

- Kubick, N.; Klimovich, P.; Bieńkowska, I.; Poznanski, P.; Łazarczyk, M.; Sacharczuk, M.; Mickael, M.-E. Investigation of Evolutionary History and Origin of the Tre1 Family Suggests a Role in Regulating Hemocytes Cells Infiltration of the Blood–Brain Barrier. Insects 2021, 12, 882. [CrossRef]

- Huson, D.H.; Bryant, D. Application of Phylogenetic Networks in Evolutionary Studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006, 23, 254–267. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F.; Park, Y.M.; Lee, J.; Buso, N.; Gur, T.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Basutkar, P.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Potter, S.C.; Finn, R.D.; et al. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W636–W641. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.; Shank, S.D.; Spielman, S.J.; Li, M.; Muse, S.V.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L. Datamonkey 2.0: A Modern Web Application for Characterizing Selective and Other Evolutionary Processes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 773–777. [CrossRef]

- Mickael, M.-E.; Kubick, N.; Klimovich, P.; Flournoy, P.H.; Bieńkowska, I.; Sacharczuk, M. Paracellular and Transcellular Leukocytes Diapedesis Are Divergent but Interconnected Evolutionary Events. Genes 2021, 12, 254. [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Velden, K.V. DIVERGE: phylogeny-based analysis for functional–structural divergence of a protein family. Bioinformatics 2002, 18, 500–501. [CrossRef]

- Kubick, N.; Brösamle, D.; Mickael, M.-E. Molecular Evolution and Functional Divergence of the IgLON Family. Evol. Bioinform. 2018, 14. [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Gouw, M.; Michael, S.; Sámano-Sánchez, H.; Pancsa, R.; Glavina, J.; Diakogianni, A.; Valverde, J.A.; Bukirova, D.; Čalyševa, J.; et al. ELM-the eukaryotic linear motif resource in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D296–D306. [CrossRef]

- Kulmanov, M.; Khan, M.A.; Hoehndorf, R. DeepGO: predicting protein functions from sequence and interactions using a deep ontology-aware classifier. Bioinformatics 2017, 34, 660–668. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-M.; Wu, H.-L.; Xia, Q.-D.; Zhou, P.; Wang, S.-G.; Yu, X.; Hu, J. Novel insights into the SPOP E3 ubiquitin ligase: From the regulation of molecular mechanisms to tumorigenesis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 149, 112882. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, A.; Petersen, F.; Zahn, S.; Götze, O.; Schröder, J.-M.; Flad, H.-D.; Brandt, E. The CXC-Chemokine Neutrophil-Activating Peptide-2 Induces Two Distinct Optima of Neutrophil Chemotaxis by Differential Interaction With Interleukin-8 Receptors CXCR-1 and CXCR-2. Blood 1997, 90, 4588–4597. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).