Submitted:

26 September 2024

Posted:

27 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Compositions

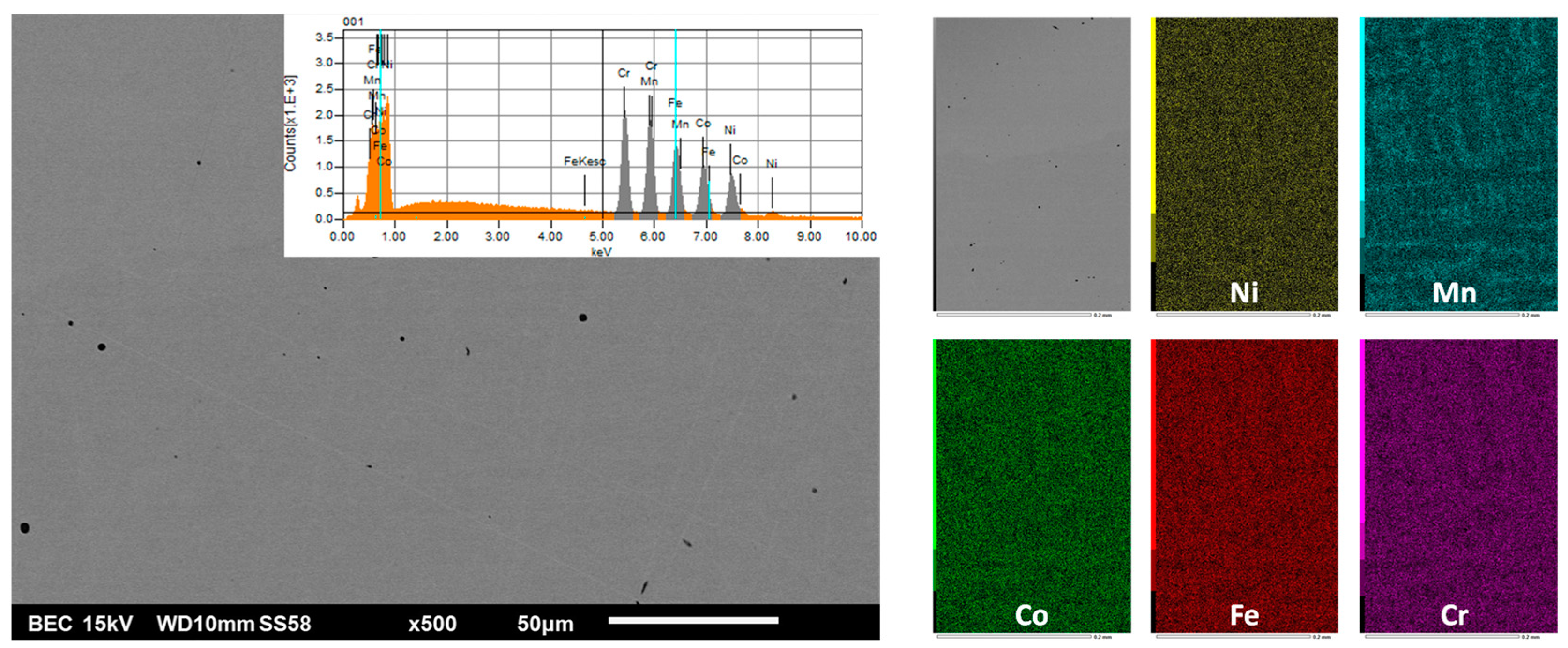

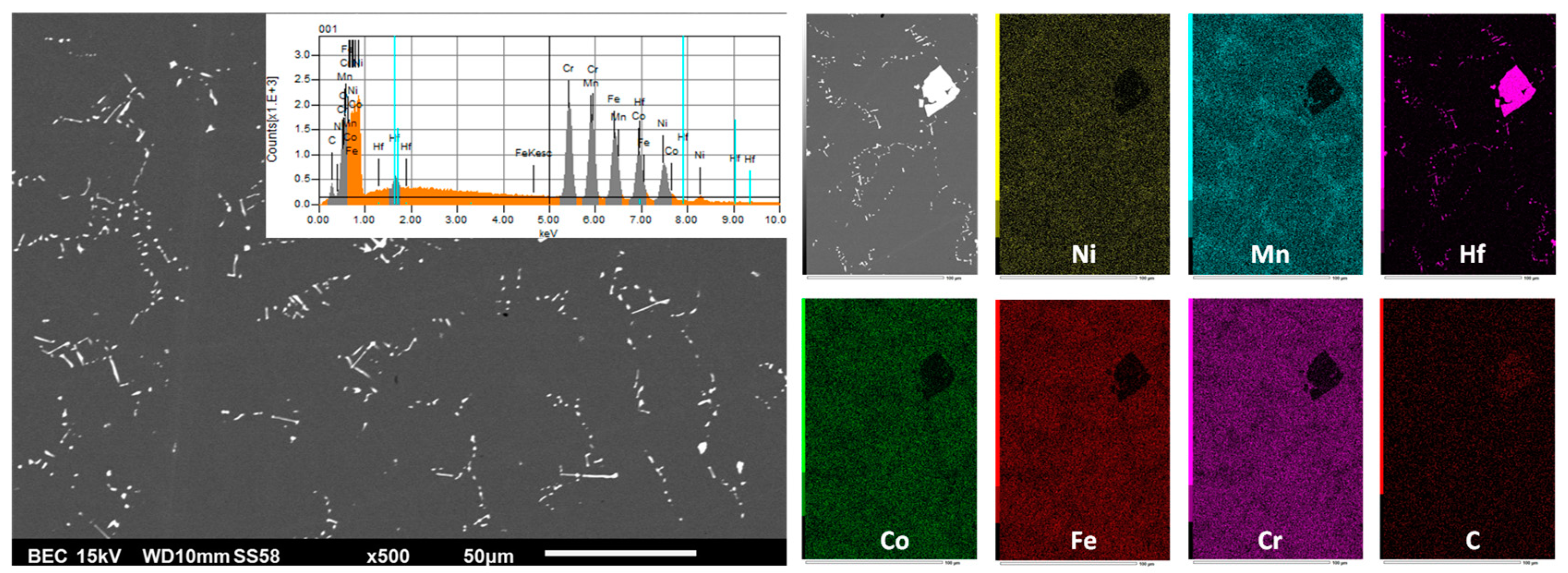

3.2. As–Cast Microstructures

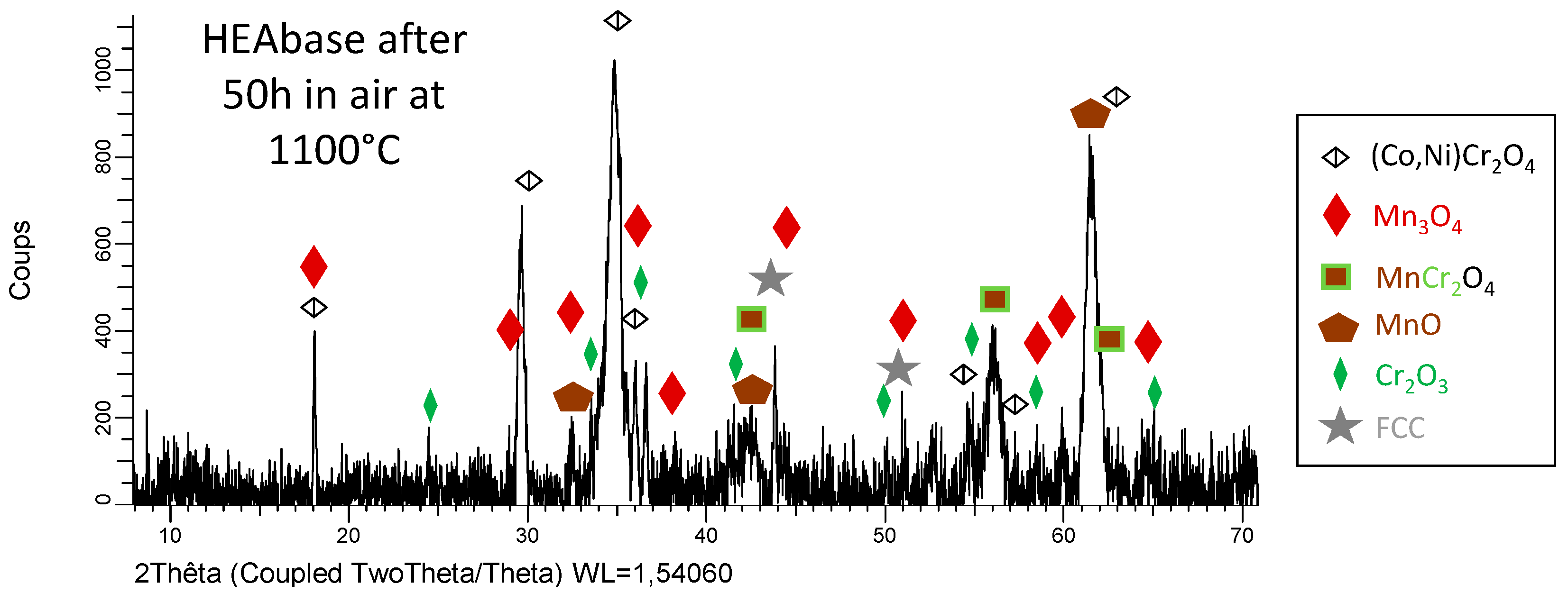

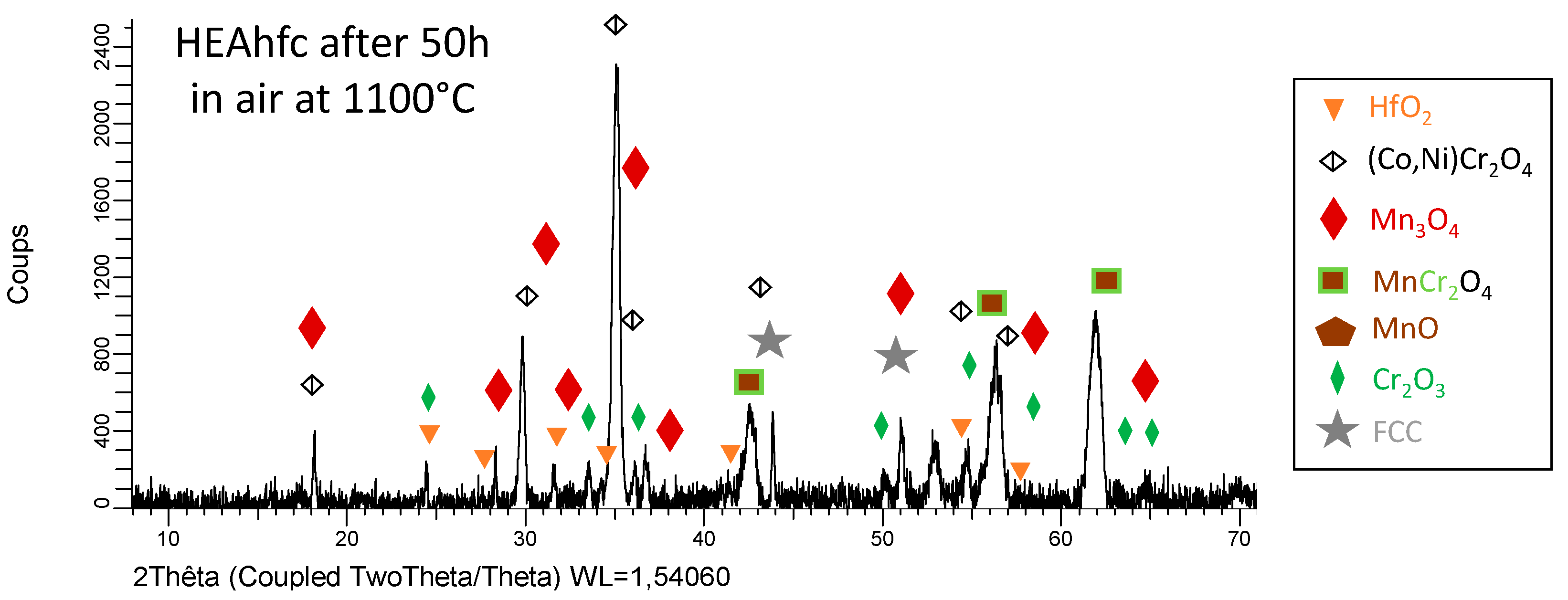

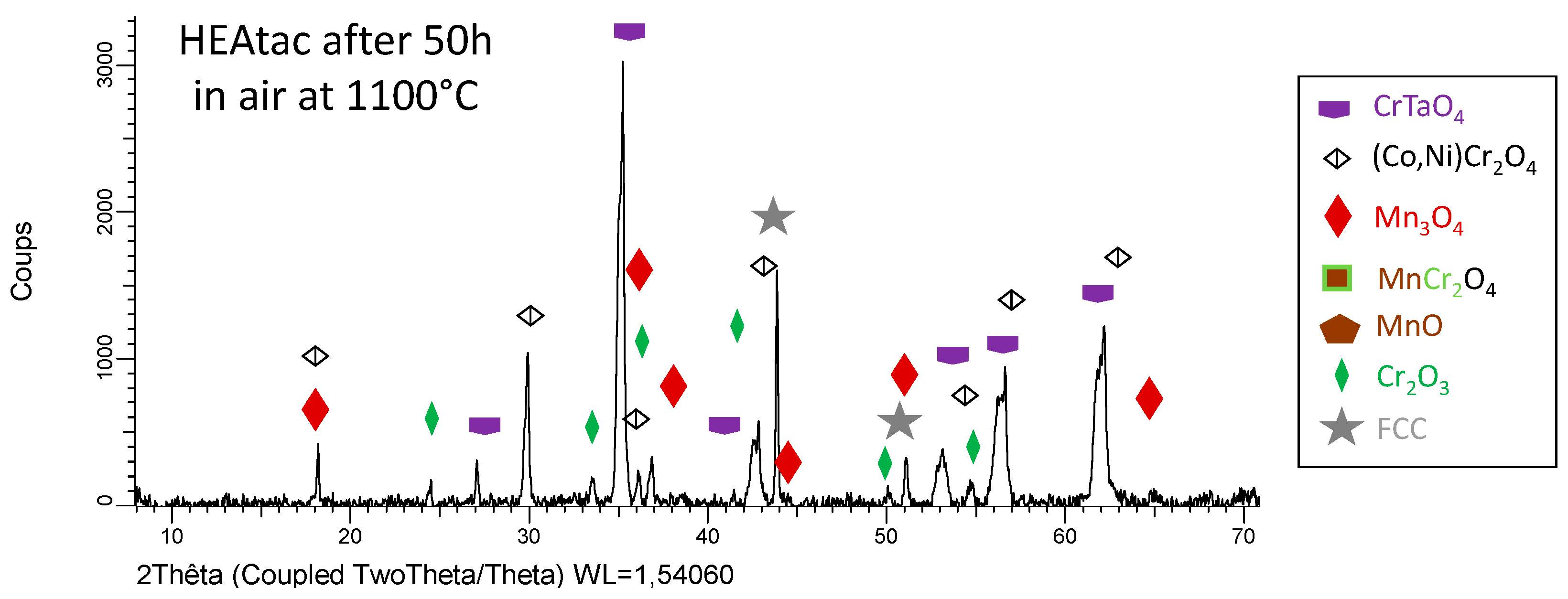

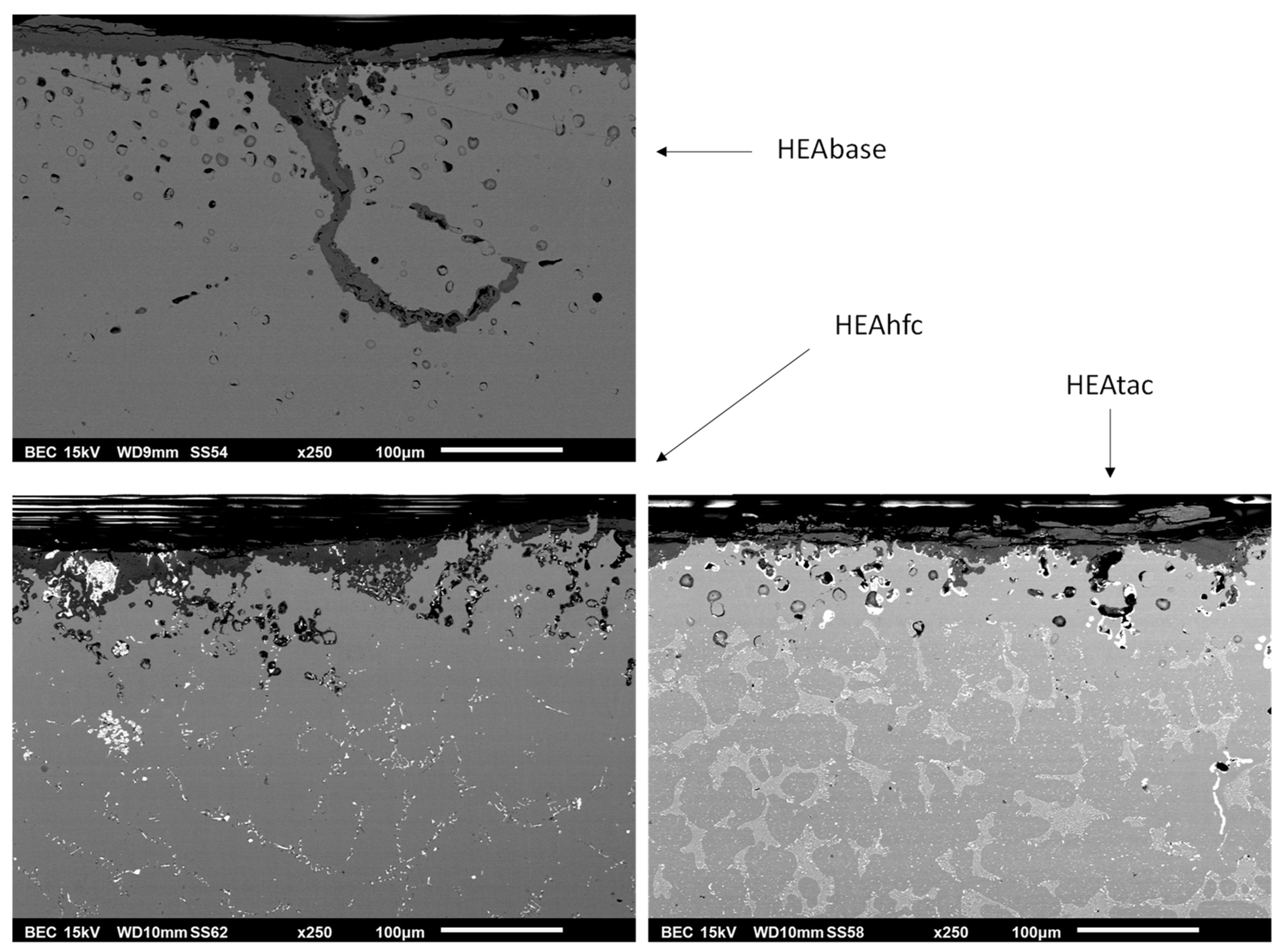

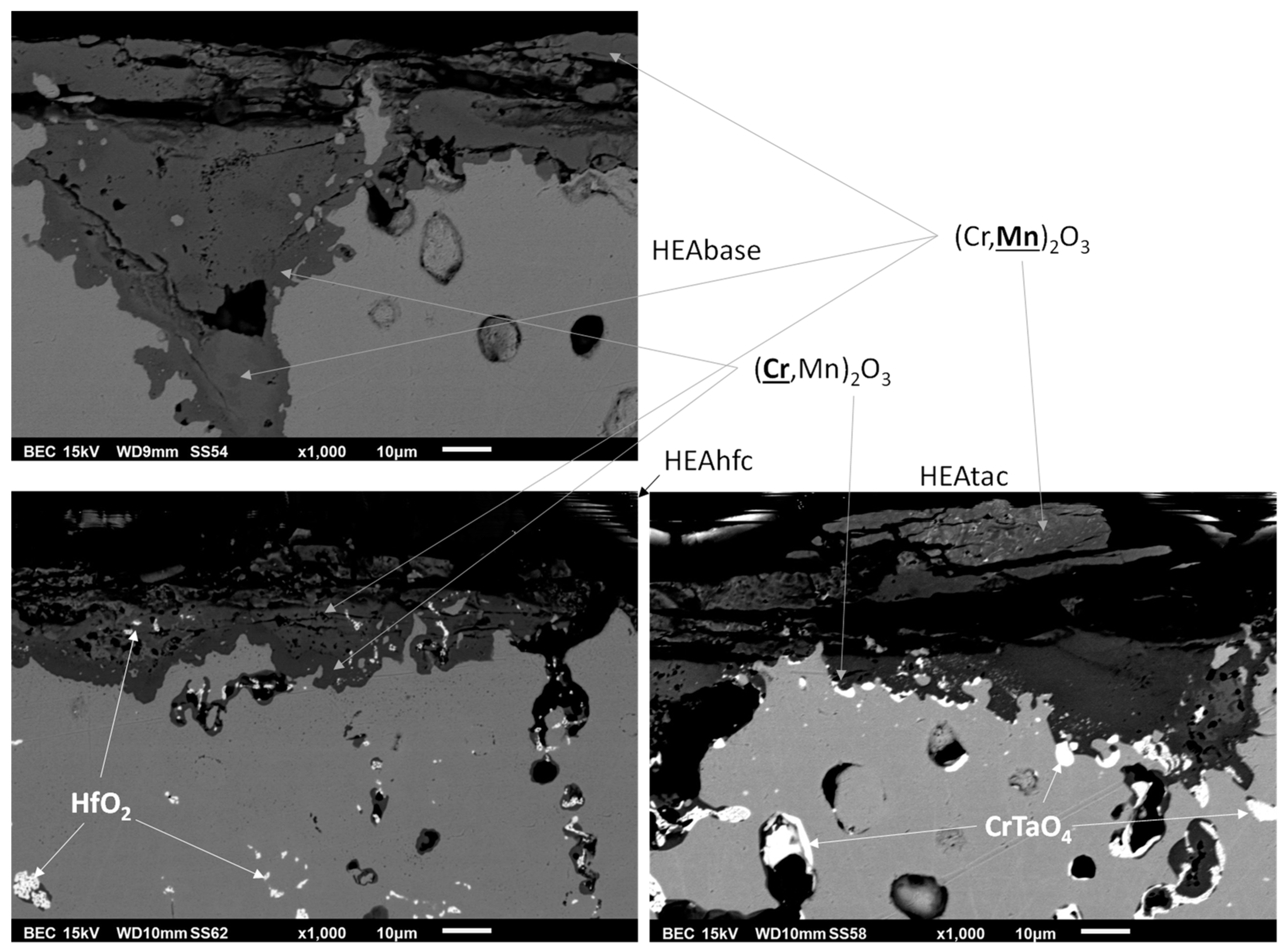

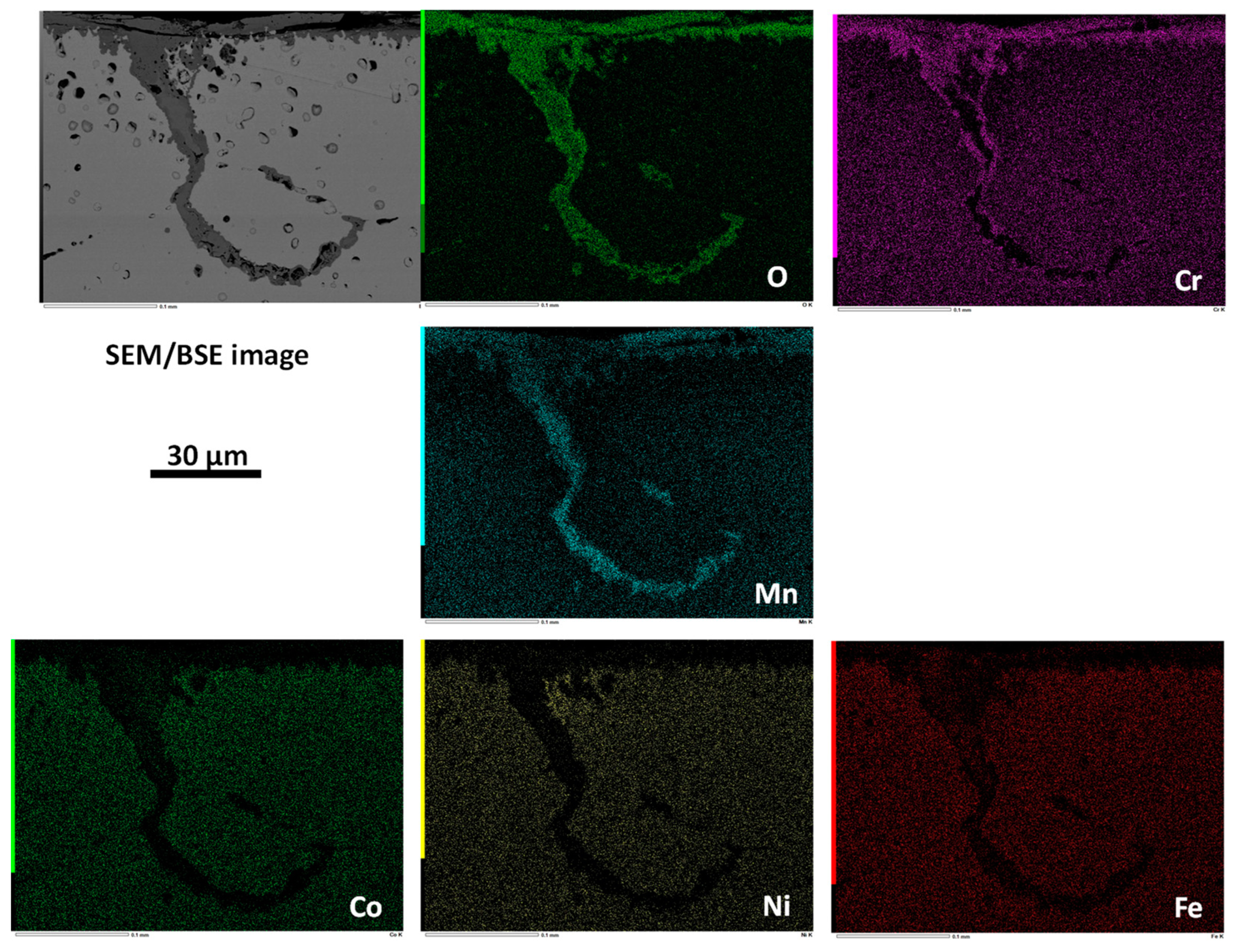

3.3. Post–Mortem Characterization of the Oxidized Samples

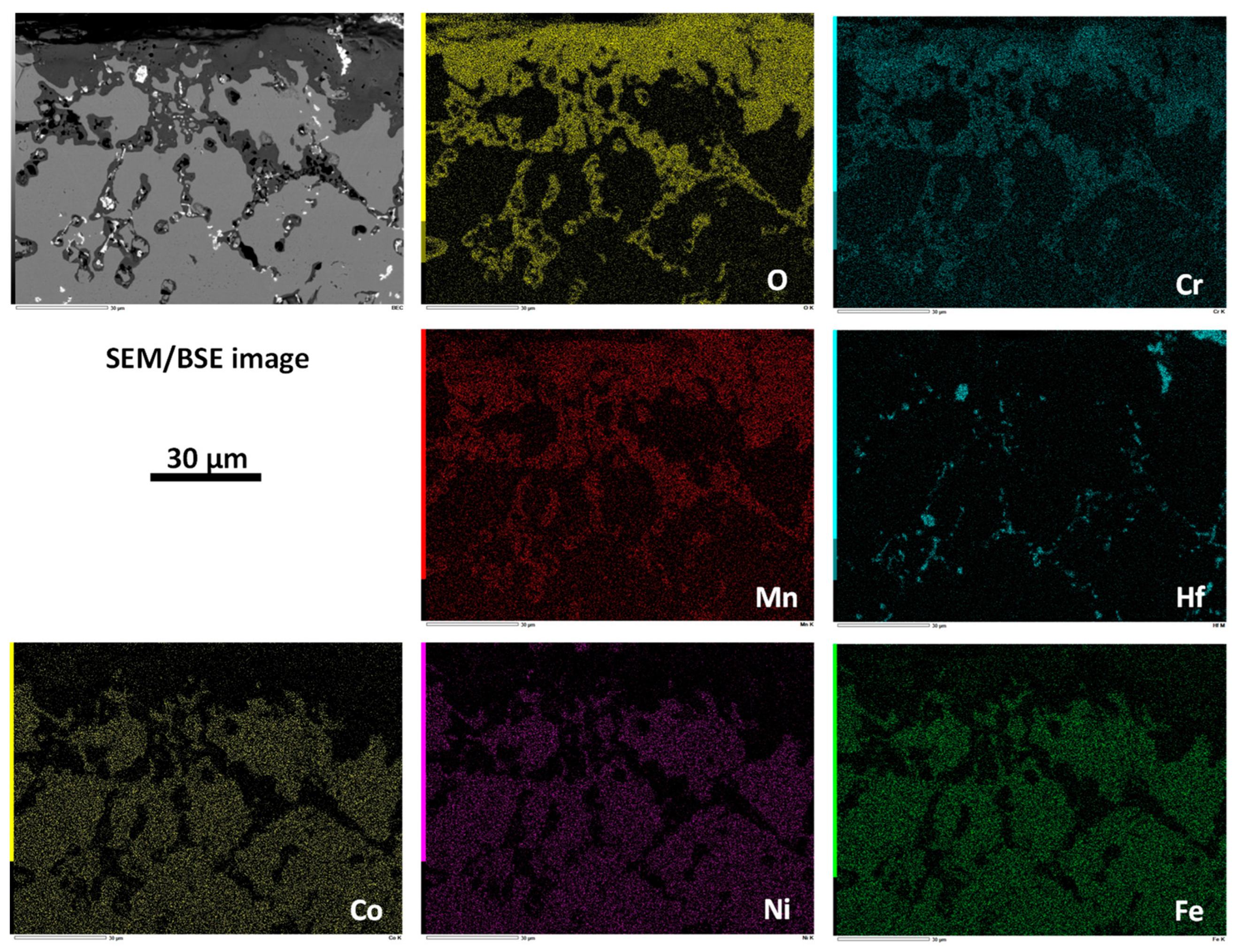

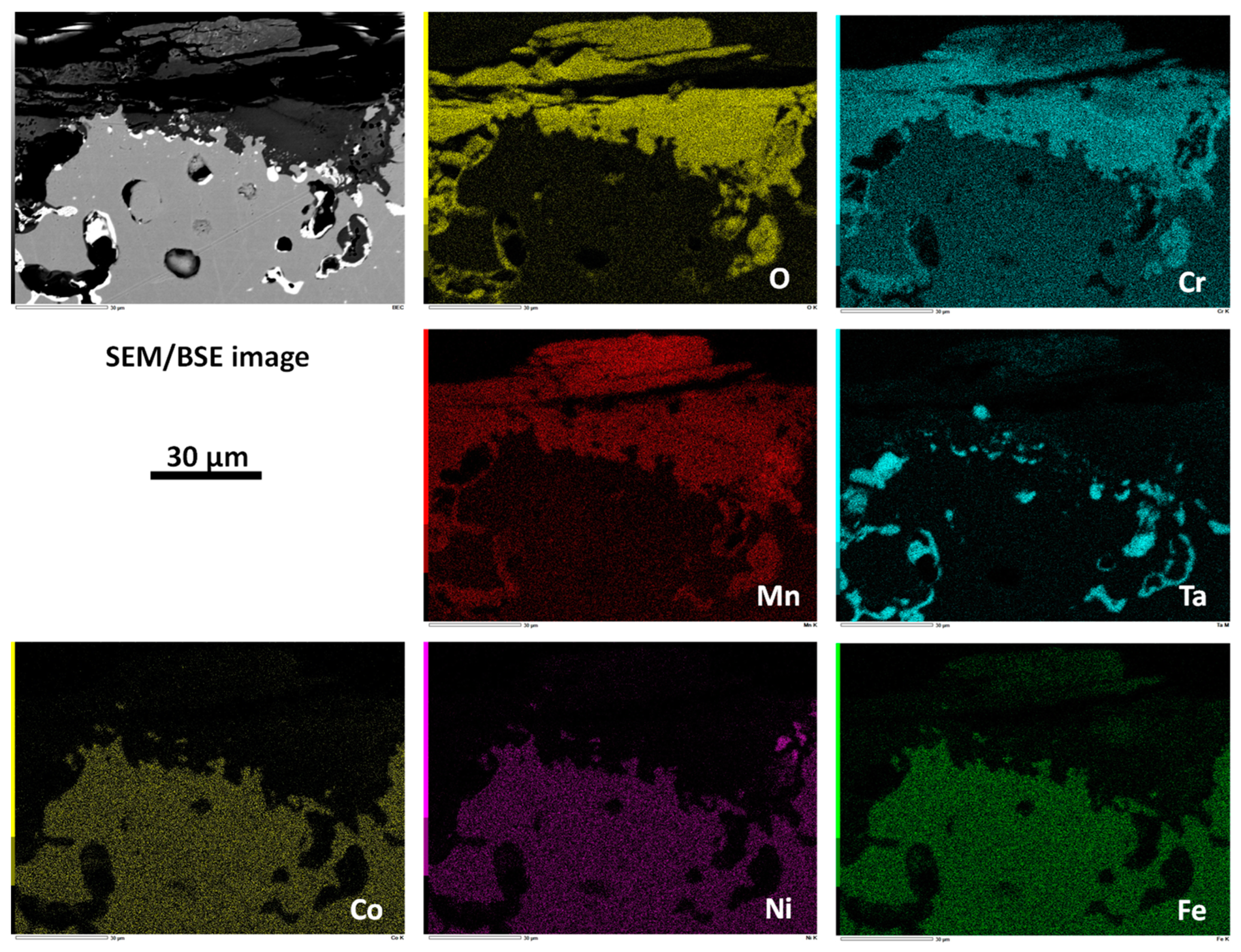

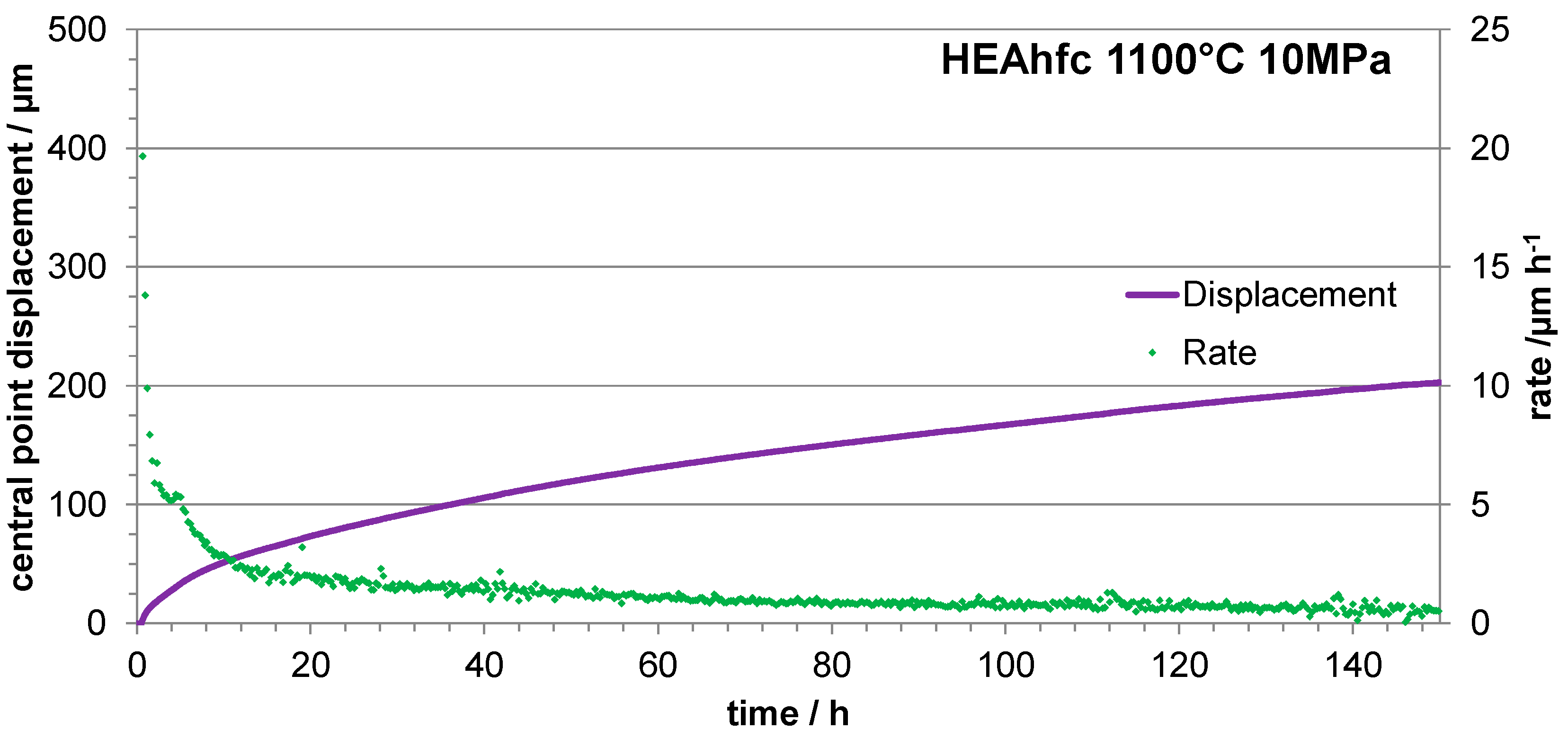

3.4. Three Points Bending Creep Tests

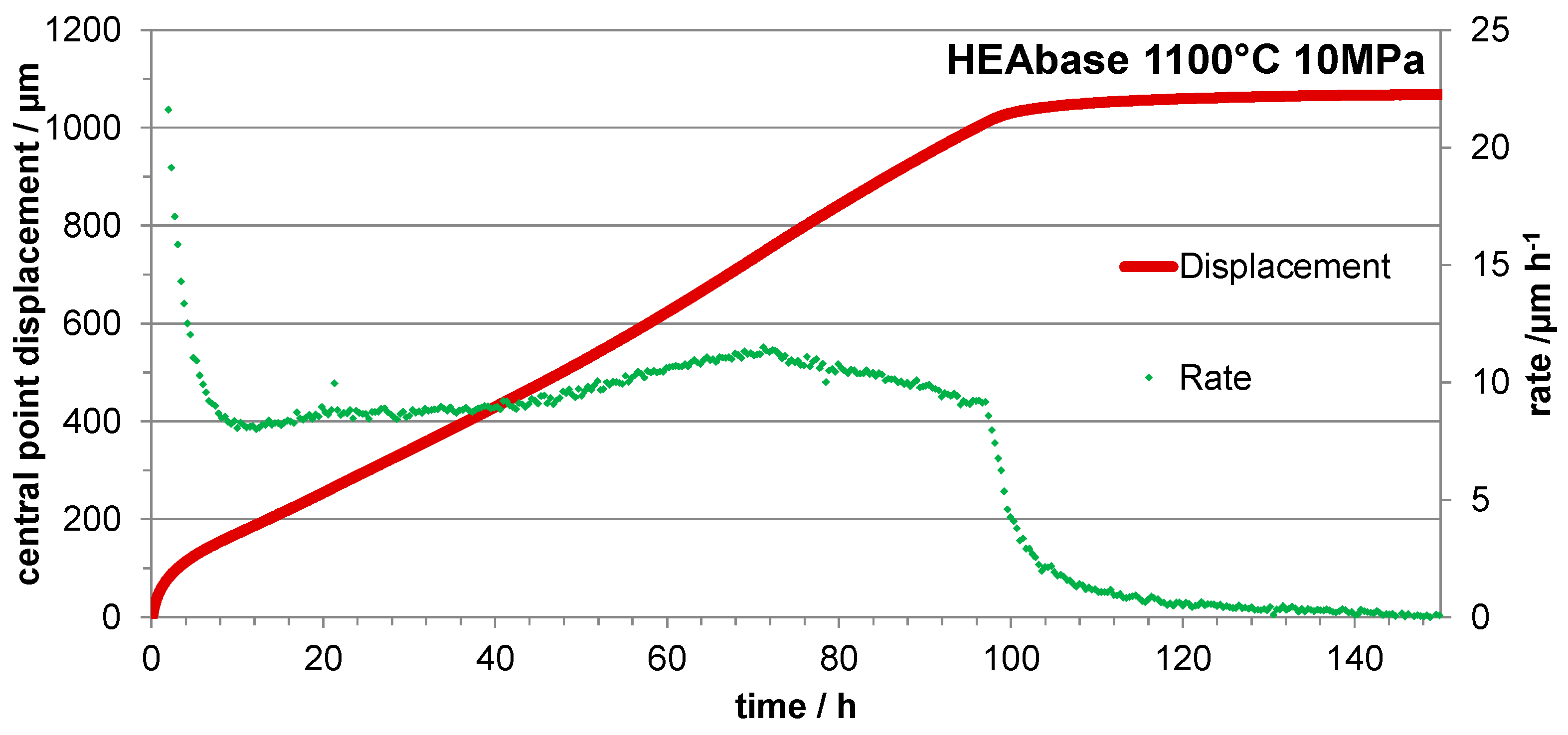

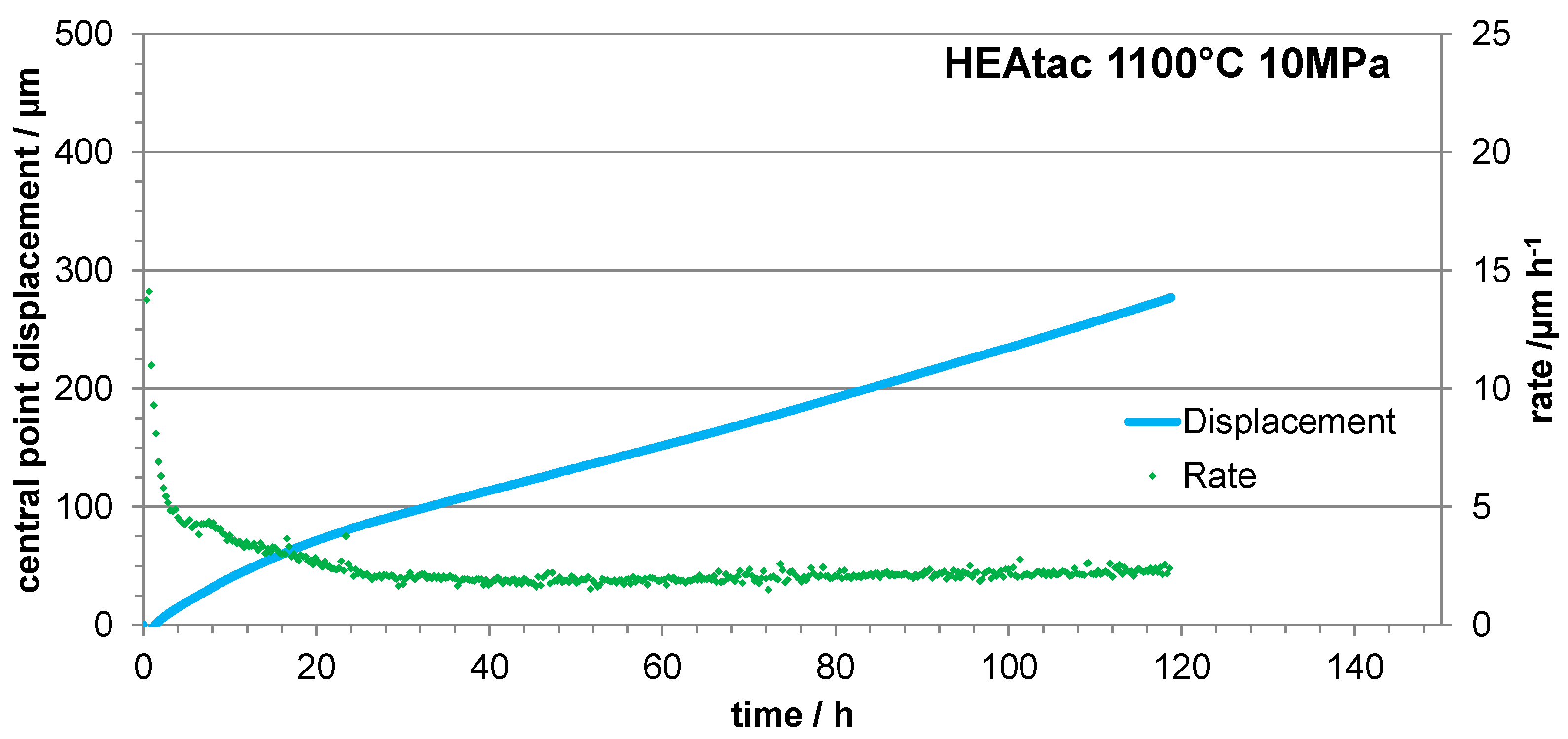

3.5. Comments on the Mechanisms of Oxidation and of Creep Deformation

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilson, P.; Field, R.; et al. The use of diffusion multiples to examine the compositional dependence of phase stability and hardness of the Co-Cr-Fe-Mn-Ni high entropy alloy system. Intermetallics 2016, 75, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowa, J.; Kucza, W.; et al. Interdiffusion in the FCC-structured Al-Co-Cr-Fe-Ni high entropy alloys: Experimental studies and numerical simulations. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2016, 674, 465–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, A. Design of eutectic high entropy alloys in Al-Co-Cr-Fe-Ni system. Metals and Materials International 2021, 27, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, A. The design of eutectic high entropy alloys in Al-Co-Cr-Fe-Ni system. Condensed Matter 2020, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, N.D.; Shaysultanov, D.G.; et al. Structure and high temperature mechanical properties of novel non-equiatomic Fe-(Co, Mn)-Cr-Ni-Al-(Ti) high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2018, 102, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.L.; Yang, T.; et al. Development of high-strength Co-free high-entropy alloys hardened by nanosized precipitates. Scripta Materialia 2018, 148, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagase, T.; Todai, M.; et al. Liquid phase separation in Ag-Co-Cr-Fe-Mn-Ni, Co Cr-Cu-Fe-Mn-Ni and Co-Cr-Cu-Fe-Mn-Ni-B high entropy alloys for biomedical application. Crystals 2020, 10(6), 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracq, G.; Laurent-Brocq, M.; et al. The fcc solid solution stability in the Co-Cr-Fe-Mn-Ni multi-component system. Acta Materialia 2017, 128, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. F.; Wu, Y.; et al. Stacking fault energy of face-centered-cubic high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2018, 93, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Li, X.; et al. Novel Co-rich high performance twinning-induced plasticity (TWIP) and transformation-induced plas-ticity (TRIP) high-entropy alloys. Scripta Materialia 2019, 165, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowa, J.; Stygar, M.; et al. Synthesis and microstructure of the (Co,Cr,Fe,Mn,Ni)3O4 high entropy oxide characterized by spinel structure. Materials Letters 2018, 216, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teramoto, T.; Yamada, K.; et al. Monocrystalline elastic constants and their temperature dependences for equi-atomic Cr-Mn-Fe-Co-Ni high-entropy alloy with the face-centered cubic structure. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2019, 777, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffmann, A.; Stueber, M.; et al. Combinatorial exploration of the high entropy alloy system Co-Cr-Fe-Mn-Ni. Surface and Coatings Technology 2017, 325, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Jung, S.; et al. Design of new face-centered cubic high entropy alloys by thermodynamic calculation. Metals and Materials International 2017, 23, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, M.; Asakura, M.; et al. Plastic deformation of single crystals of the equiatomic Cr-Mn-Fe-Co-Ni high-entropy alloy in tension and compression from 10 K to 1273 K. Acta Materialia 2021, 203, 116454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, C.; Tang, F.; et al. Combining thermodynamic modeling and 3D printing of elemental powder blends for high-throughput investigation of high-entropy alloys - Towards rapid alloy screening and design. Materials Science & Engi-neering, A: Structural Materials: Properties, Microstructure and Processing 2017, 688, 180–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Q.; Feng, K.; et al. Microstructure and corrosion properties of CrMnFeCoNi high entropy alloy coating. Applied Surface Science 2017, 396, 1420–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Ma, Q.; et al. Effects of vacancy on the thermodynamic properties of Co-Cr-Fe-Mn-Ni high-entropy alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2021, 885, 160944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varvenne, C.; Luque, A.; et al. Theory of strengthening in fcc high entropy alloys. Acta Materialia 2016, 118, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, A. Simple approach to model the strength of solid-solution high entropy alloys in Co-Cr-Fe-Mn-Ni system. Condensed Matter 2020, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucza, W.; Dabrowa, J.; et al. Studies of "sluggish diffusion" effect in Co-Cr-Fe-Mn-Ni, Co-Cr-Fe-Ni and Co-Fe-Mn-Ni high entropy alloys; determination of tracer diffusivities by combinatorial approach. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2018, 731, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, L. High-throughput determination of interdiffusion coefficients for Co-Cr-Fe-Mn-Ni high-entropy alloys. Journal of Phase Equilibria and Diffusion 2017, 38(4), 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthod, P.; Conrath, E. Mechanical and chemical properties at high temperature of {M-25Cr}-based alloys containing hafnium carbides (M=Co, Ni or Fe): creep behavior and oxidation at 1200°C. Journal of Material Science and Technology Research 2014, 1, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michon, S.; Aranda, L.; et al. High temperature evolution of the microstructure of a cast cobalt base superalloy. Consequences on its thermomechanical properties. La Revue de Métallurgie-CIT/Science et Génie des Matériaux 2004, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthod, P.; Tlili, S. Creep and oxidation behaviors of 25 wt. % Cr–containing nickel-based alloys reinforced by ZrC carbides. Crystals 2022, 12, 416. [Google Scholar]

- Berthod, P.; Conrath, E. Creep and oxidation kinetics at 1100 °C of nickel-base alloys reinforced by hafnium carbides. Mate-rials and Design 2016, 104, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, N.D.; Yurchenko, N.Y.; et al. Effect of carbon content and annealing on structure and hardness of the CoCrFeNiMn-based high entropy alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2016, 687, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthod, P. As-Cast microstructures of high entropy alloys designed to be TaC-strengthened. Journal of Metallic Material Research 2022, 5(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthod, P. As–cast microstructures of HEA designed to be strengthened by HfC. Journal of Engineering Sciences and Innovation 2022, 7, 305–314. Available online: https://jesi.astr.ro/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/3_Patrice-Berthod. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Koermann, F. Surface segregation in Cr-Mn-Fe-Co-Ni high entropy alloys. Applied Surface Science 2020, 533, 147471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthod, P. Influence of chromium carbides on the high temperature oxidation behavior and on chromium diffusion in nickel-base alloys. Oxidation of Metals 2007, 68, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthod, P.; Hamini, Y.; et al. Influence of tantalum on the rates of high temperature oxidation and chromia volatilization for cast (Fe and/or Ni)-30Cr-0.4C alloys. Materials Science Forum 2008, 595-598, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrath, E.; Berthod, P. Kinetics of high temperature oxidation of chromium rich HfC reinforced cobalt based alloys. Corro-sion Engineering, Science and Technology 2014, 49, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Joo, Y.A.; et al. High temperature oxidation behavior of Cr-Mn-Fe-Co-Ni high entropy alloy. Intermetallics 2018, 98, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabat, K.C.; Rajput, P.; Paramguru, R.K. , Bhoi, B. ; Mishra, B.K. Reduction of Oxide Minerals by Hydrogen Plasma: An Overview. Plasma Chem Plasma Process 2014, 34, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ellingham_Richardson-diagram_english.svg.

| Weight and atomic contents | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Hf or Ta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEAbase | wt.% | 19.8 | 19.5 | 19.5 | 19.8 | 21.4 | / |

| at.% | 20.1 | 20.2 | 19.9 | 19.1 | 20.7 | / | |

| HEAhfc | wt.% | 19.3 | 18.2 | 18.4 | 19.9 | 20.2 | 4.0 |

| at.% | 19.9 | 19.1 | 19.0 | 19.5 | 19.9 | 1.3 | |

| HEAtac | wt.% | 19.2 | 18.3 | 18.6 | 19.3 | 20.1 | 4.5 |

| at.% | 19.9 | 19.3 | 19.3 | 19.0 | 19.9 | 1.4 |

| Extreme surface (contents in wt.%) |

Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Hf or Ta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEAbase | Average | 12.1 | 1.9 | 29.9 | 27.7 | 28.3 | / |

| Std dev. | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | / | |

| HEAhfc | Average | 11.0 | 2.5 | 27.8 | 28.9 | 29.9 | 0 |

| Std dev. | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0 | |

| HEAtac | Average | 11.7 | 1.6 | 29.4 | 27.0 | 30.0 | 0.3 |

| Std dev. | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).