Submitted:

26 September 2024

Posted:

27 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Overview of the Reservoir

2.1. Structural Characteristics

2.2. Reservoir Characteristics

2.2.1. Reservoir Characteristics

- Sedimentary microphases and lithology

- 2.

- Reservoir characteristics

- 3.

- Distribution characteristics of interbedded layers

2.2.2. Fluid Properties

2.2.3. Temperature and Pressure

3. Model Description

3.1. Mathematical Model

3.1.1. Subsubsection

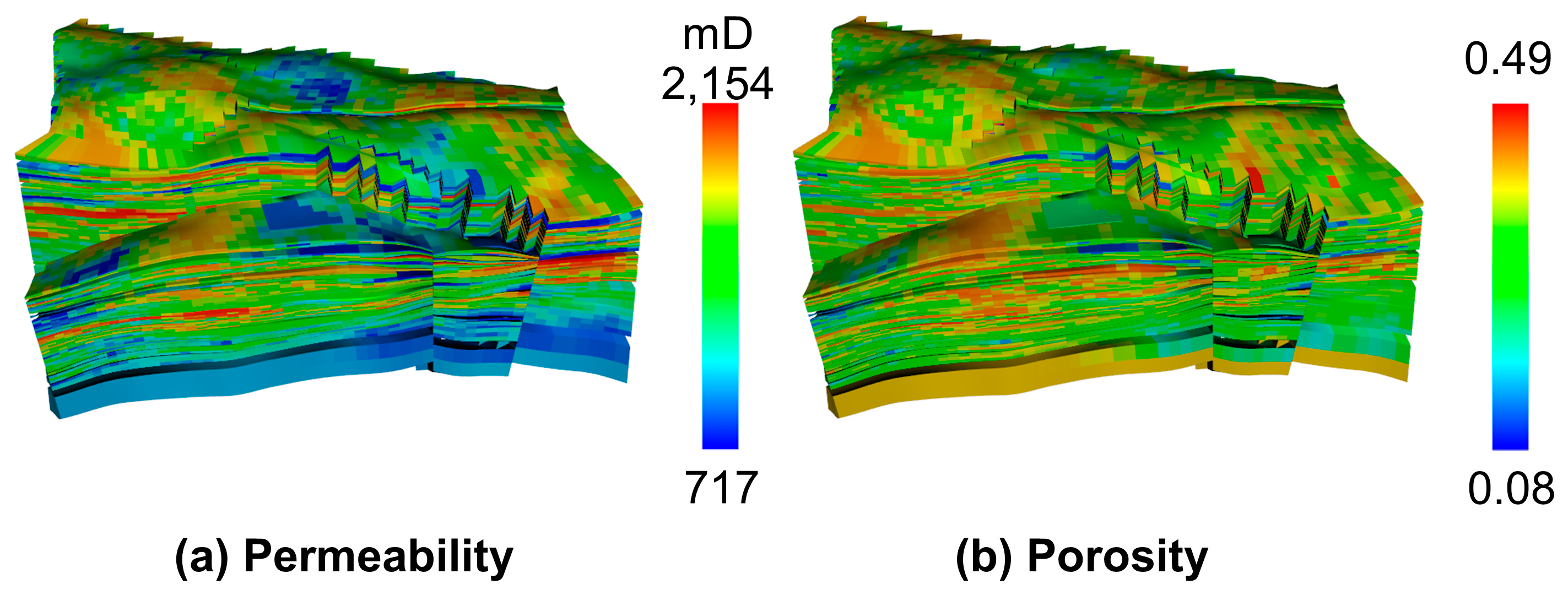

3.2. Numerical Simulation Model

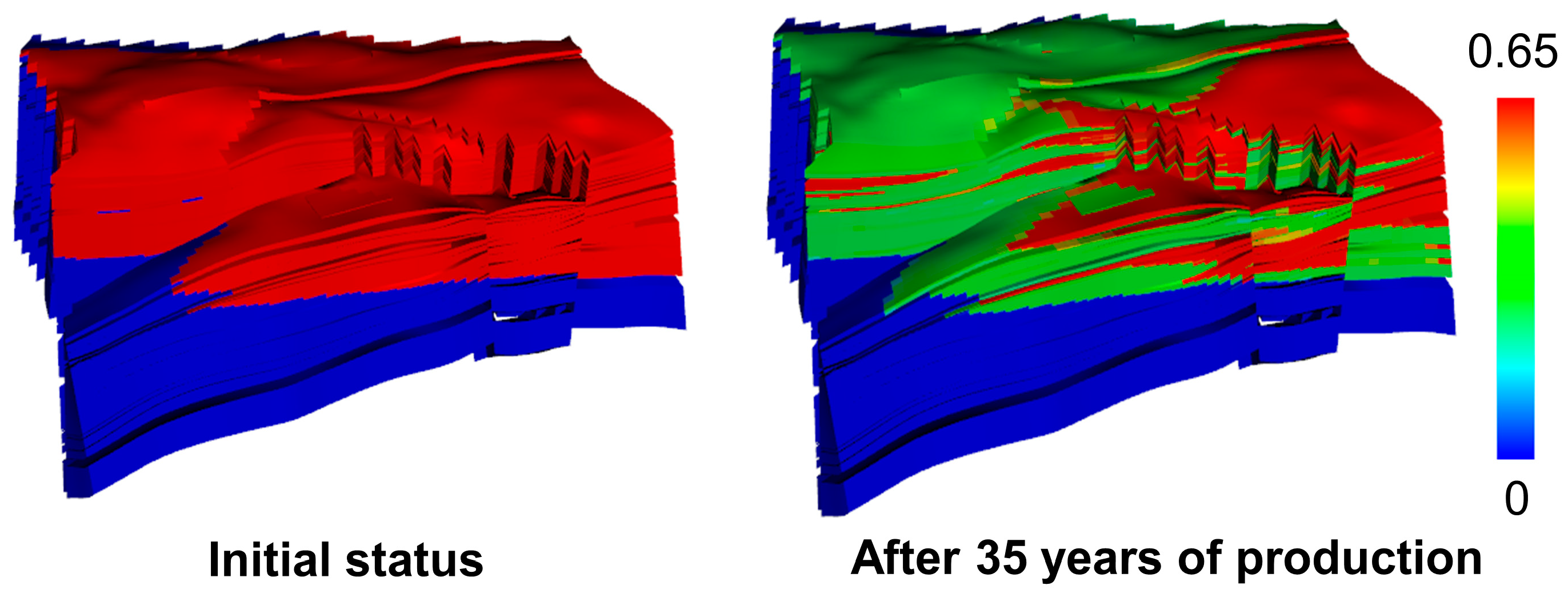

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Figures, Tables and Schemes

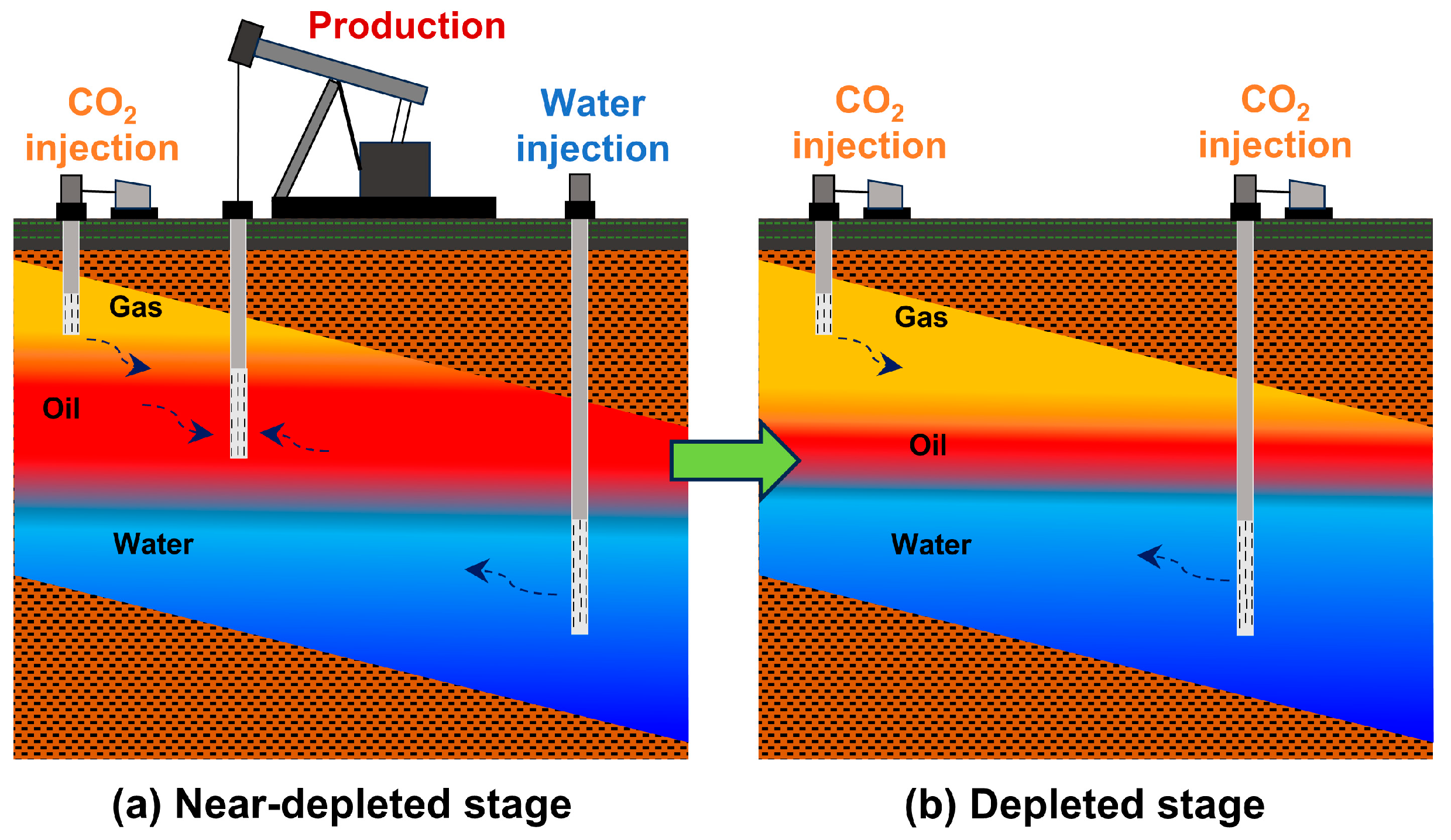

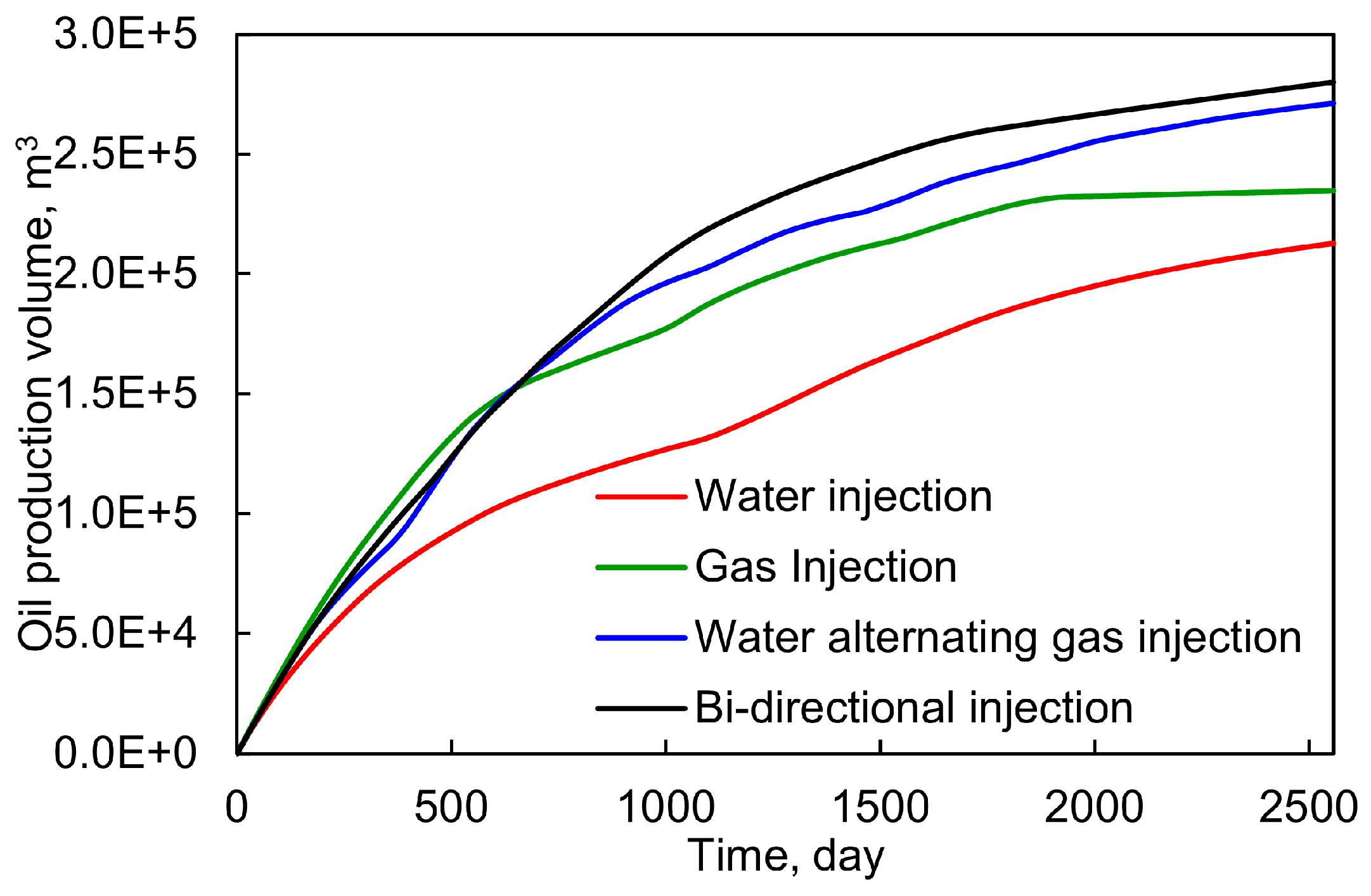

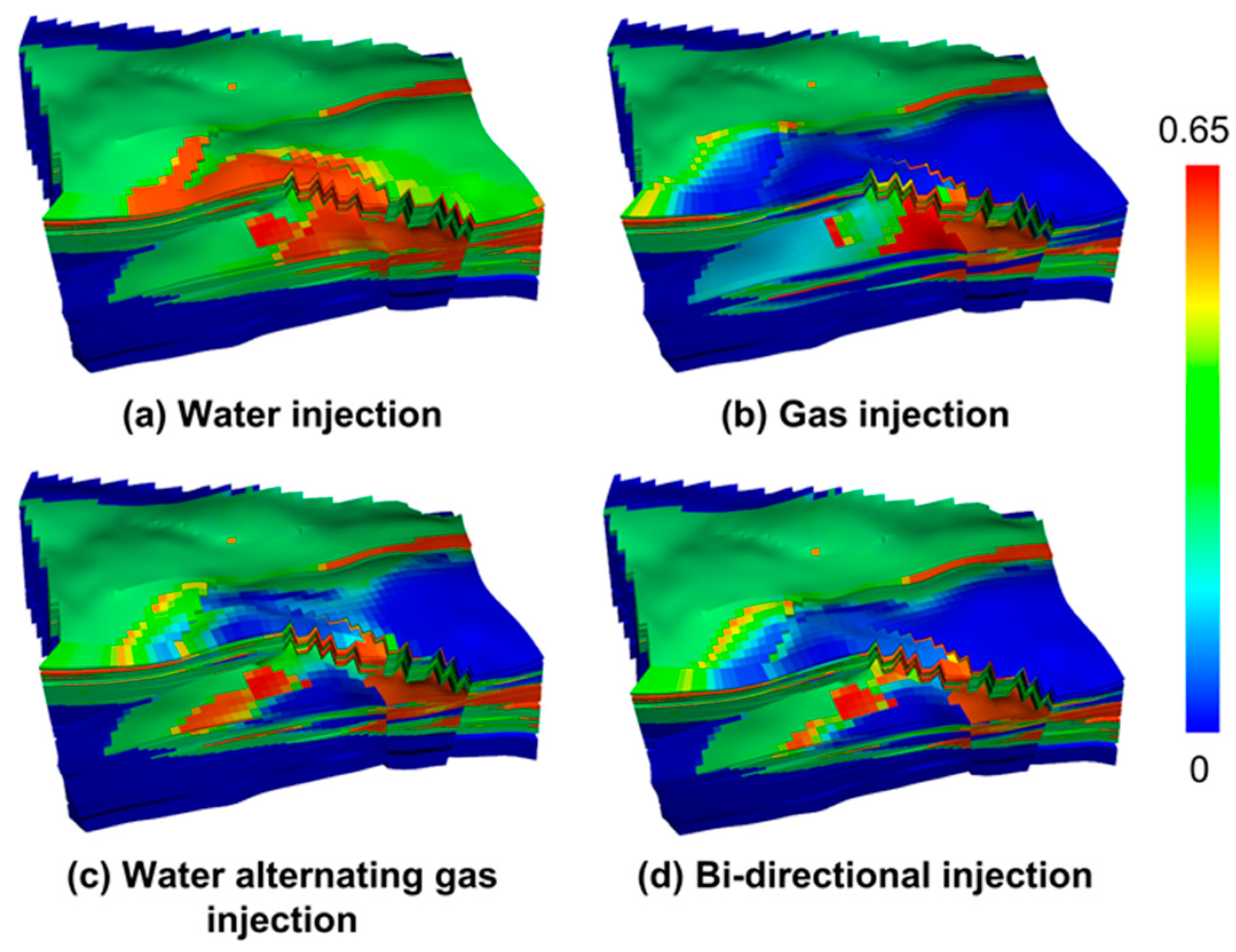

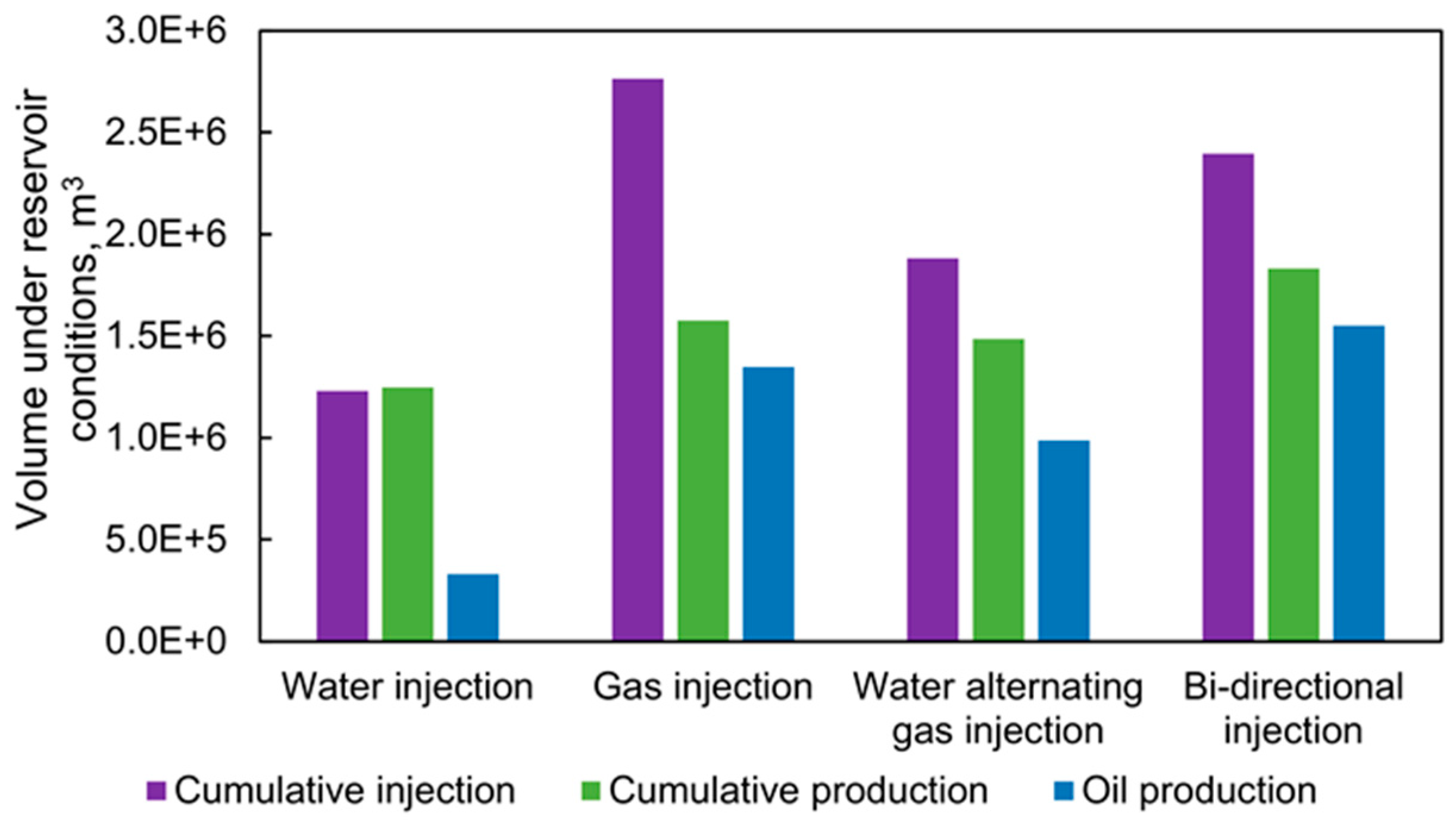

4.1.1. Injection Modes

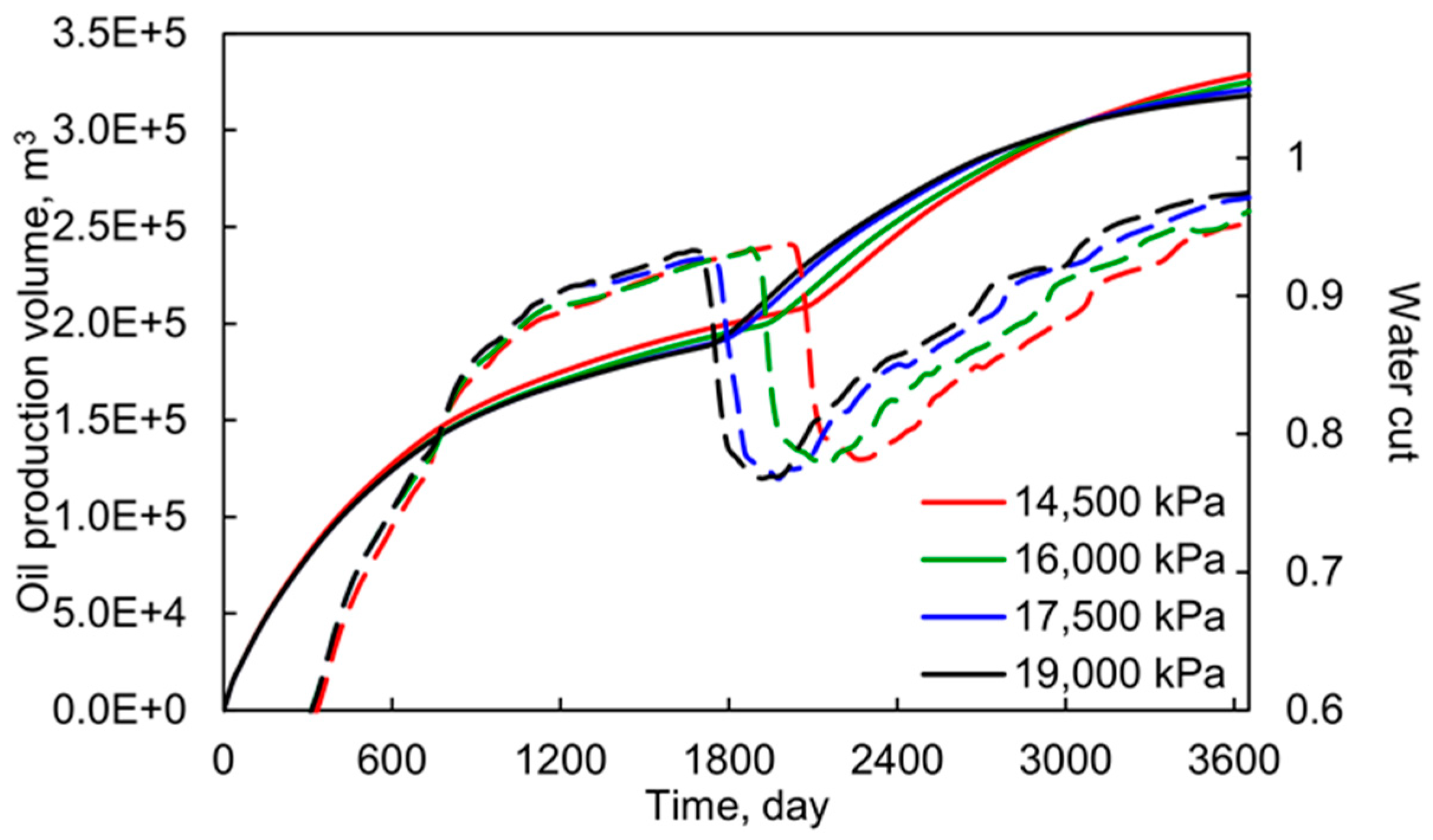

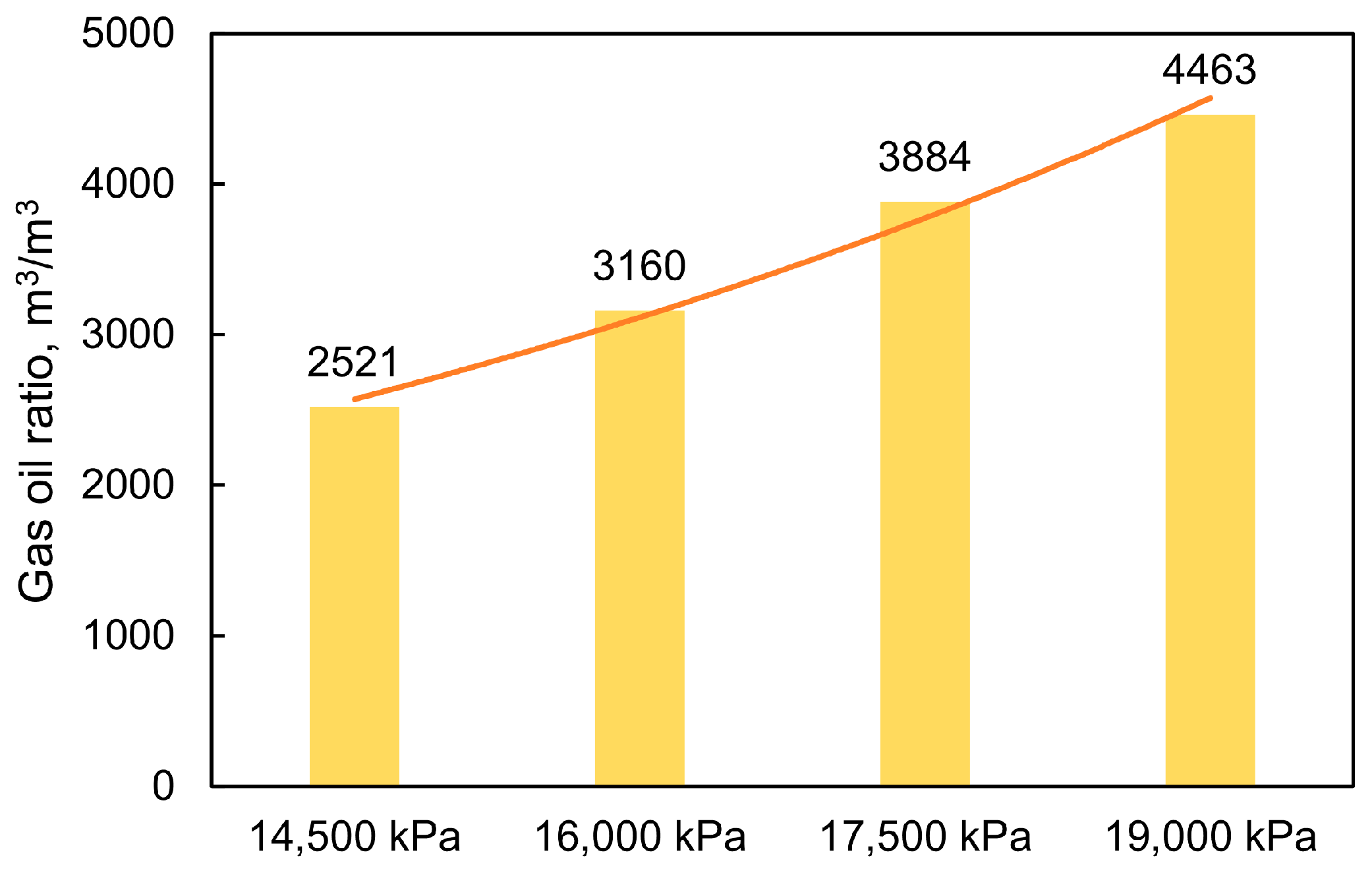

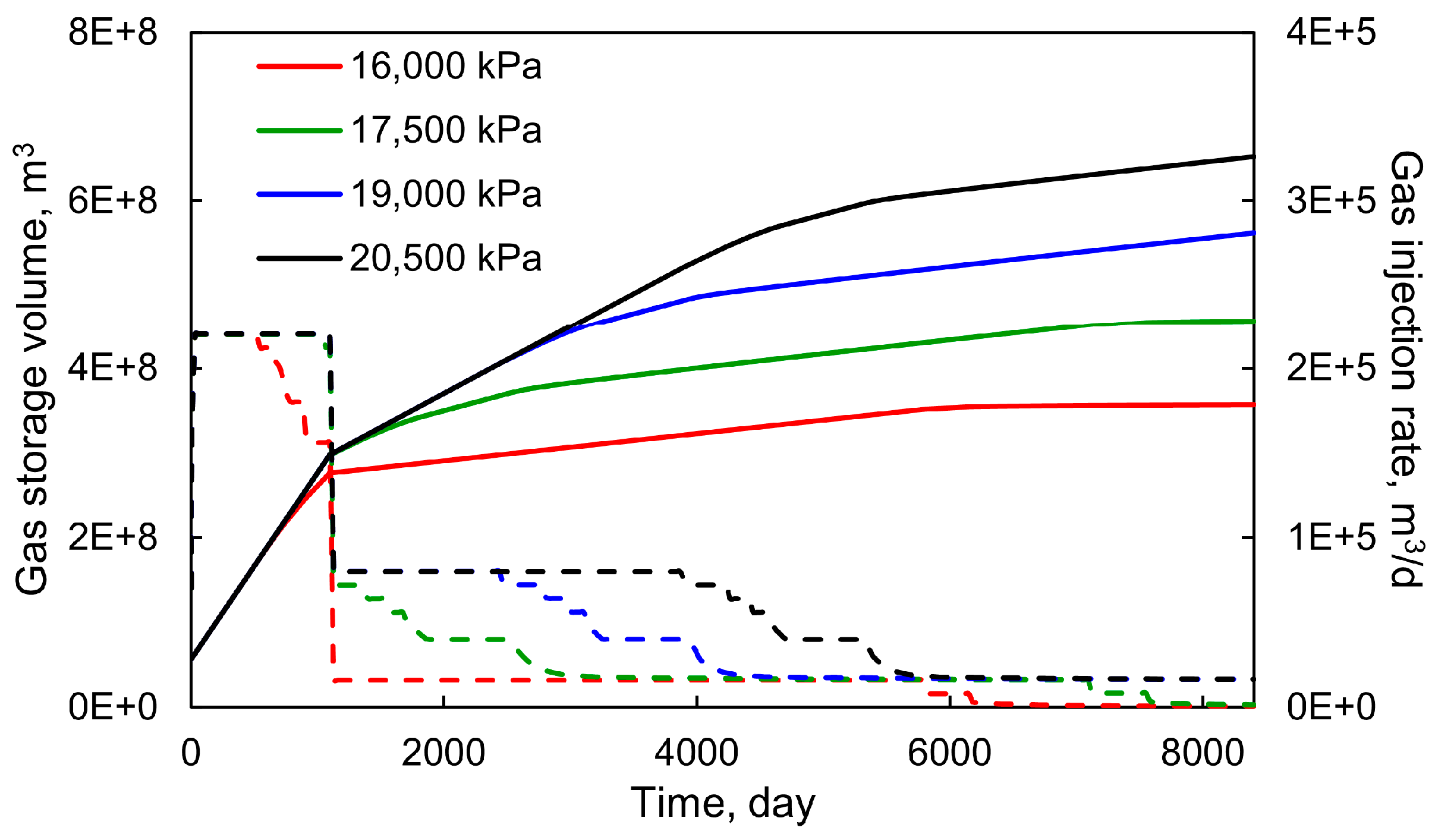

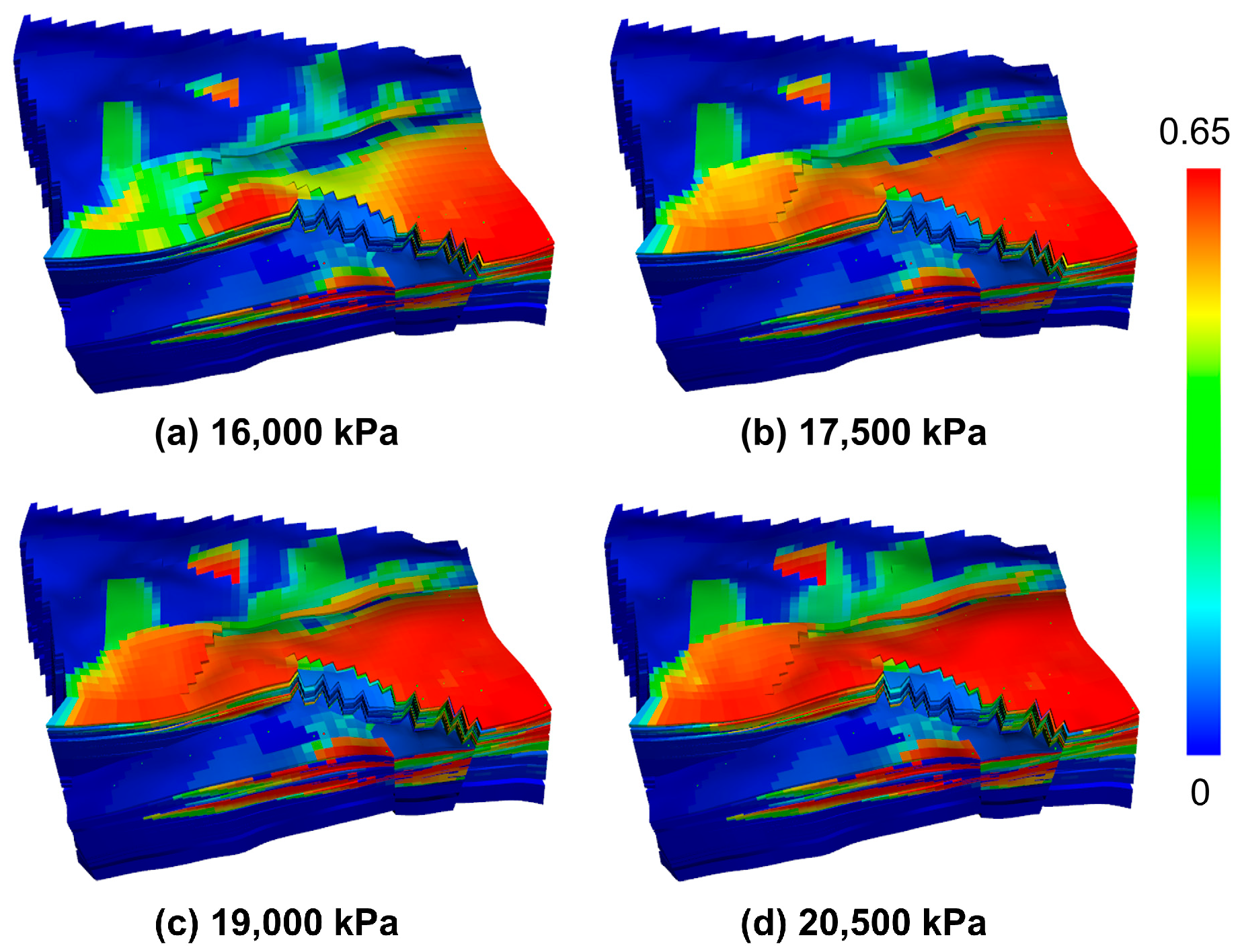

4.1.2. Injection Pressure

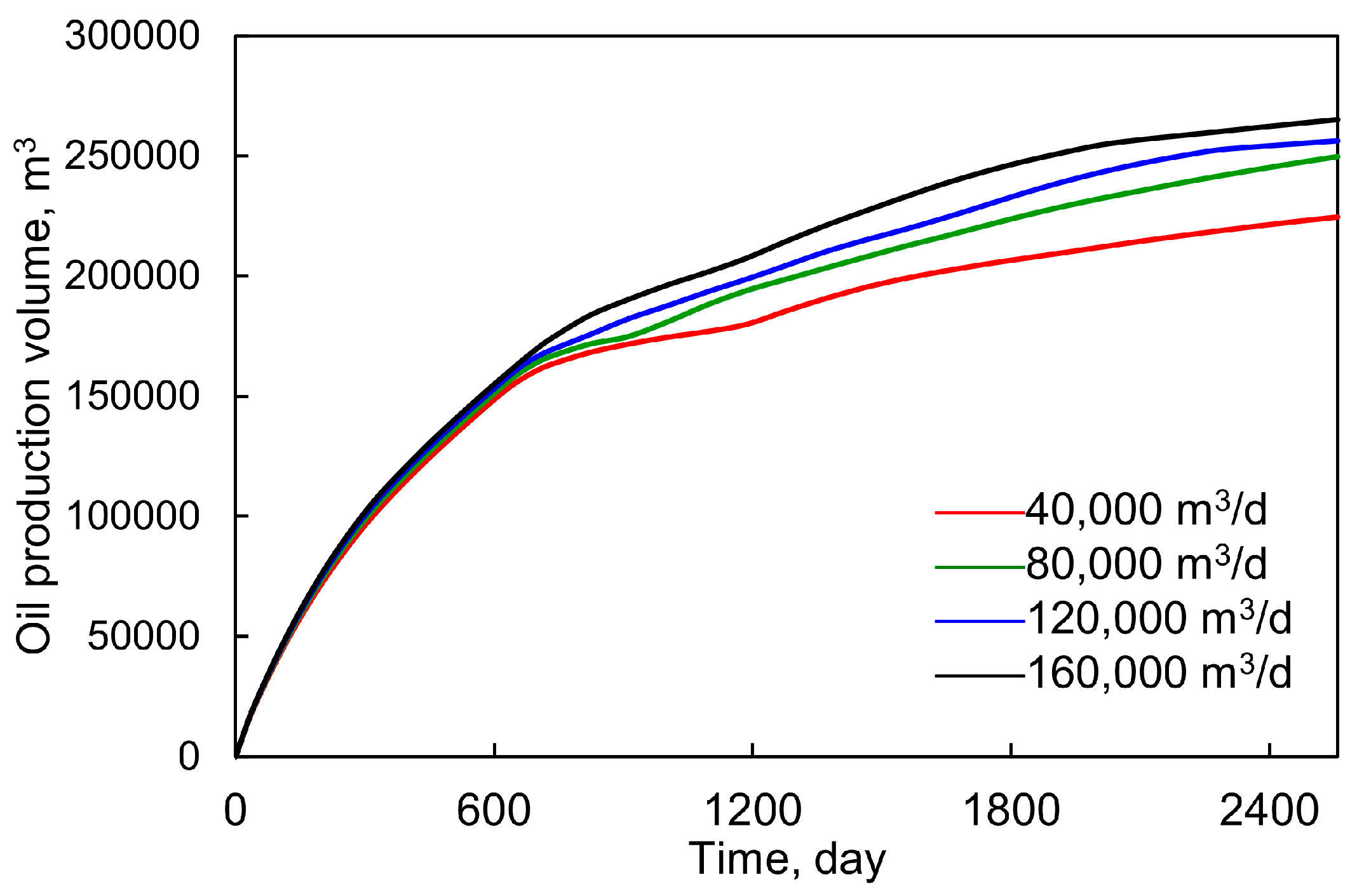

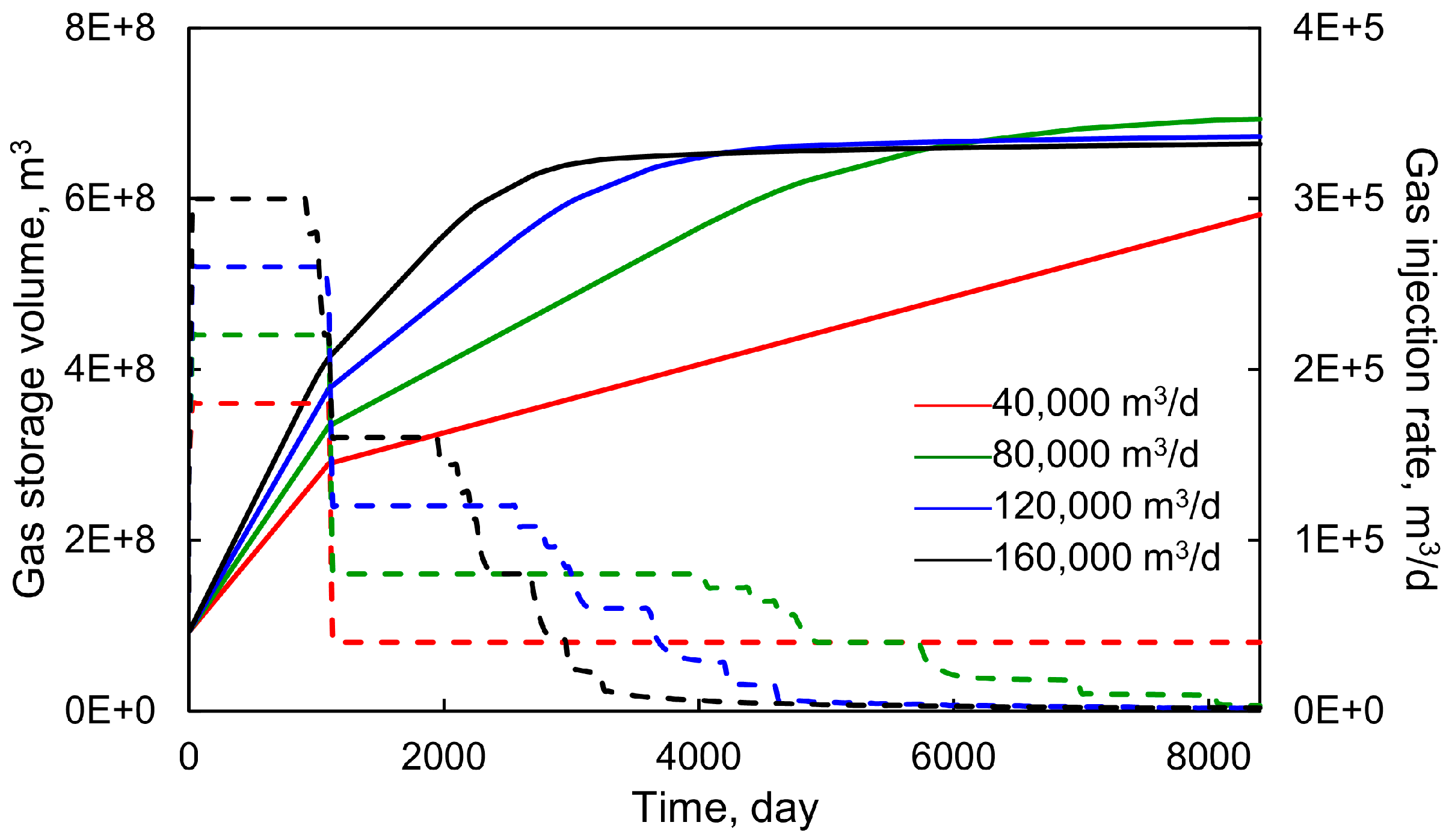

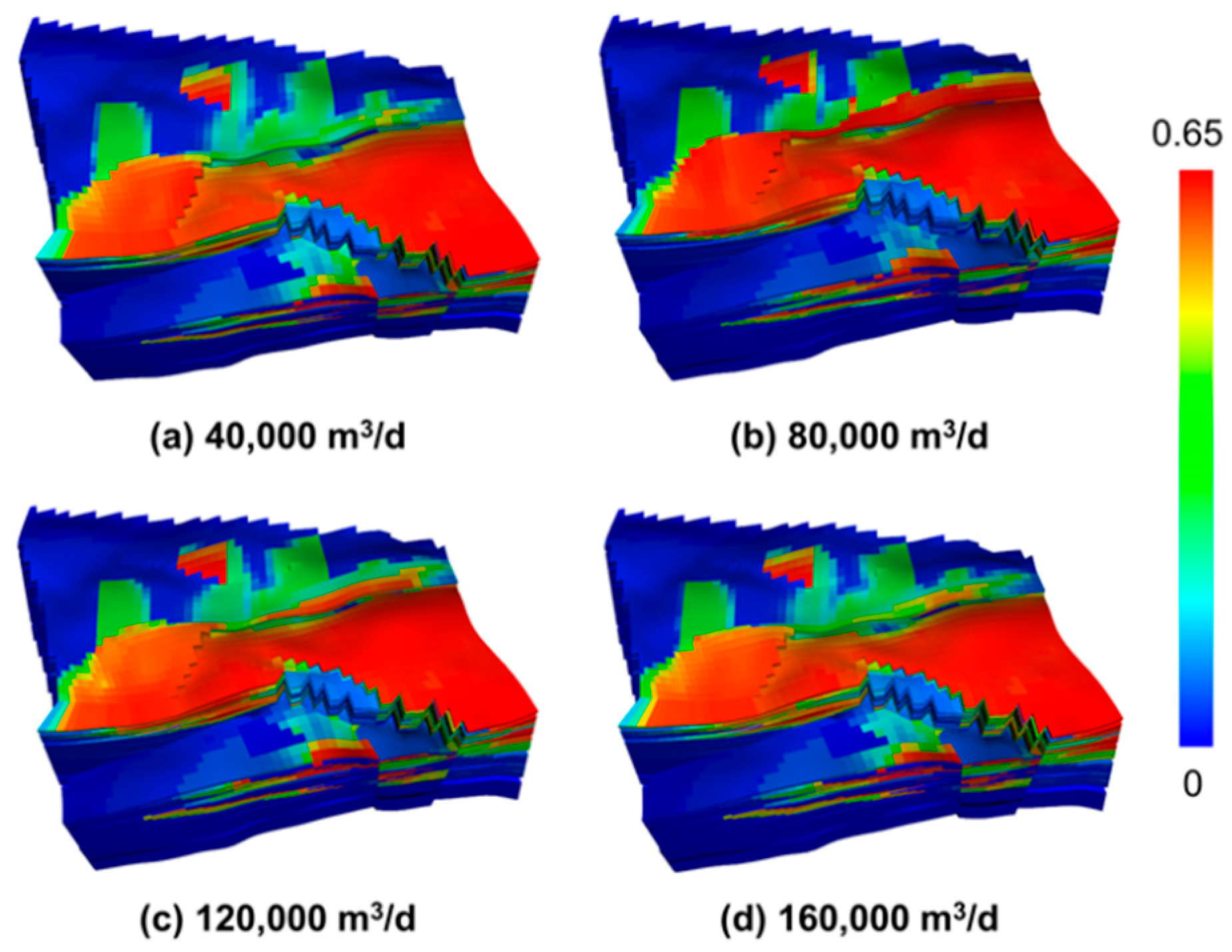

4.1.3. Gas Injection Rate

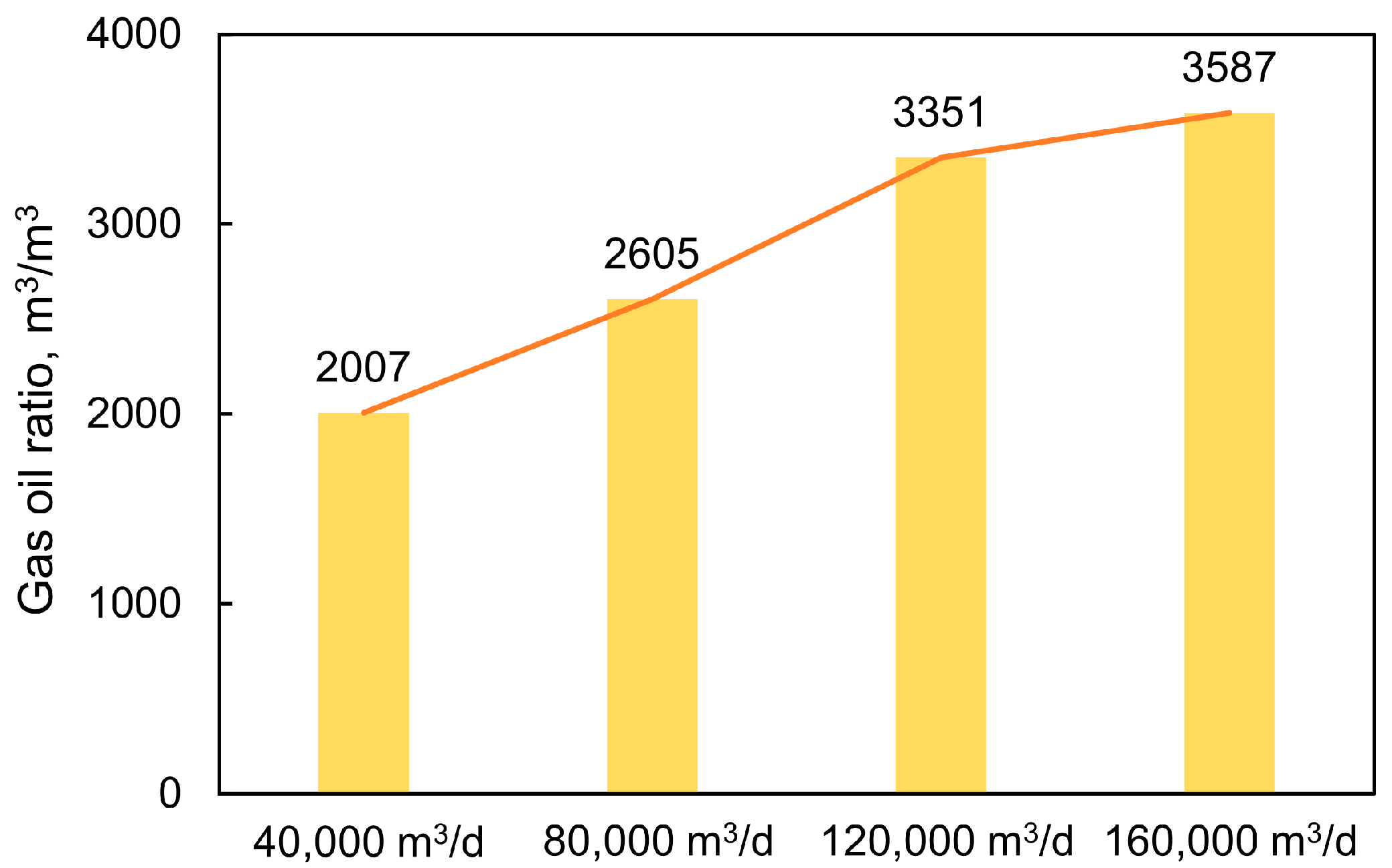

4.1.4. Gas Injection Rate

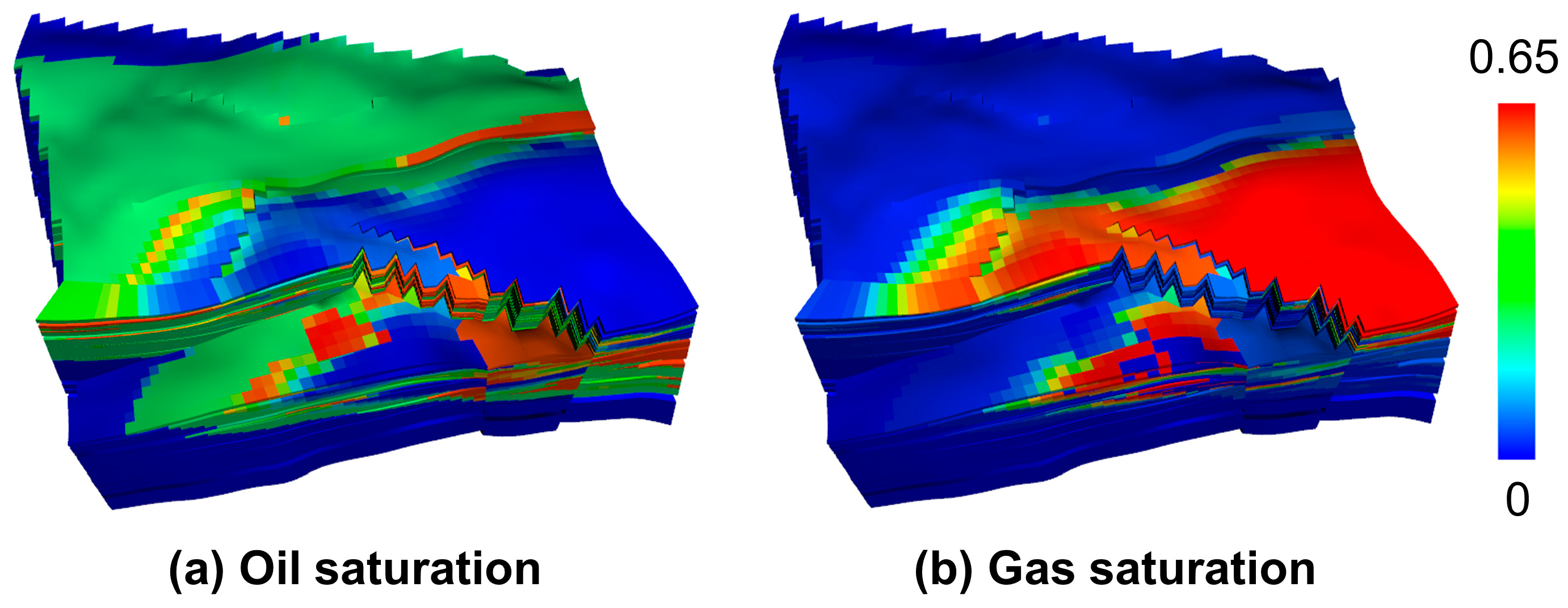

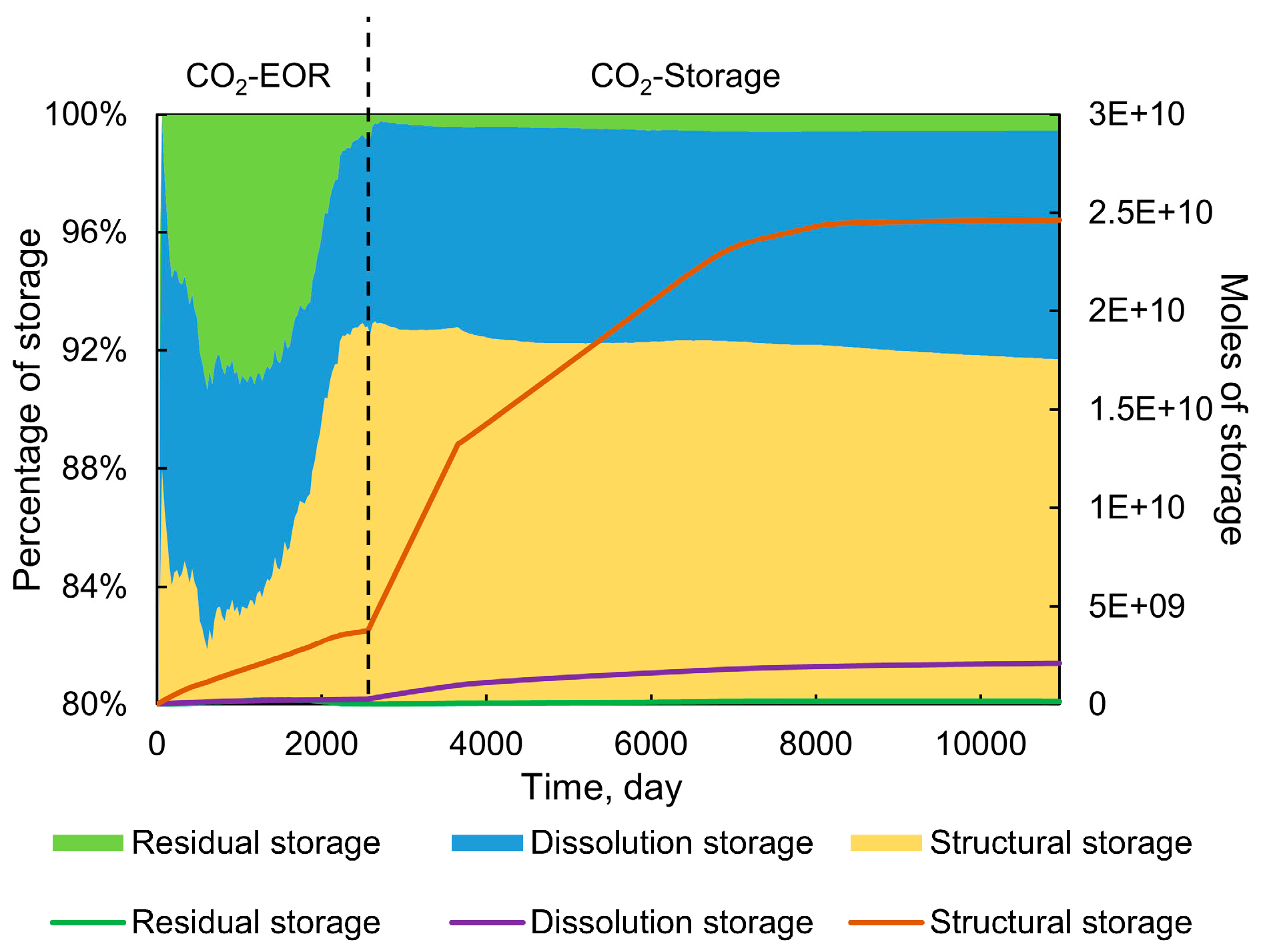

4.2. Analysis of CO2 Storage in Near-Depleted Edge-Bottom Water Reservoir

4.2.1. Injection Pressure

4.2.2. Injection Rate

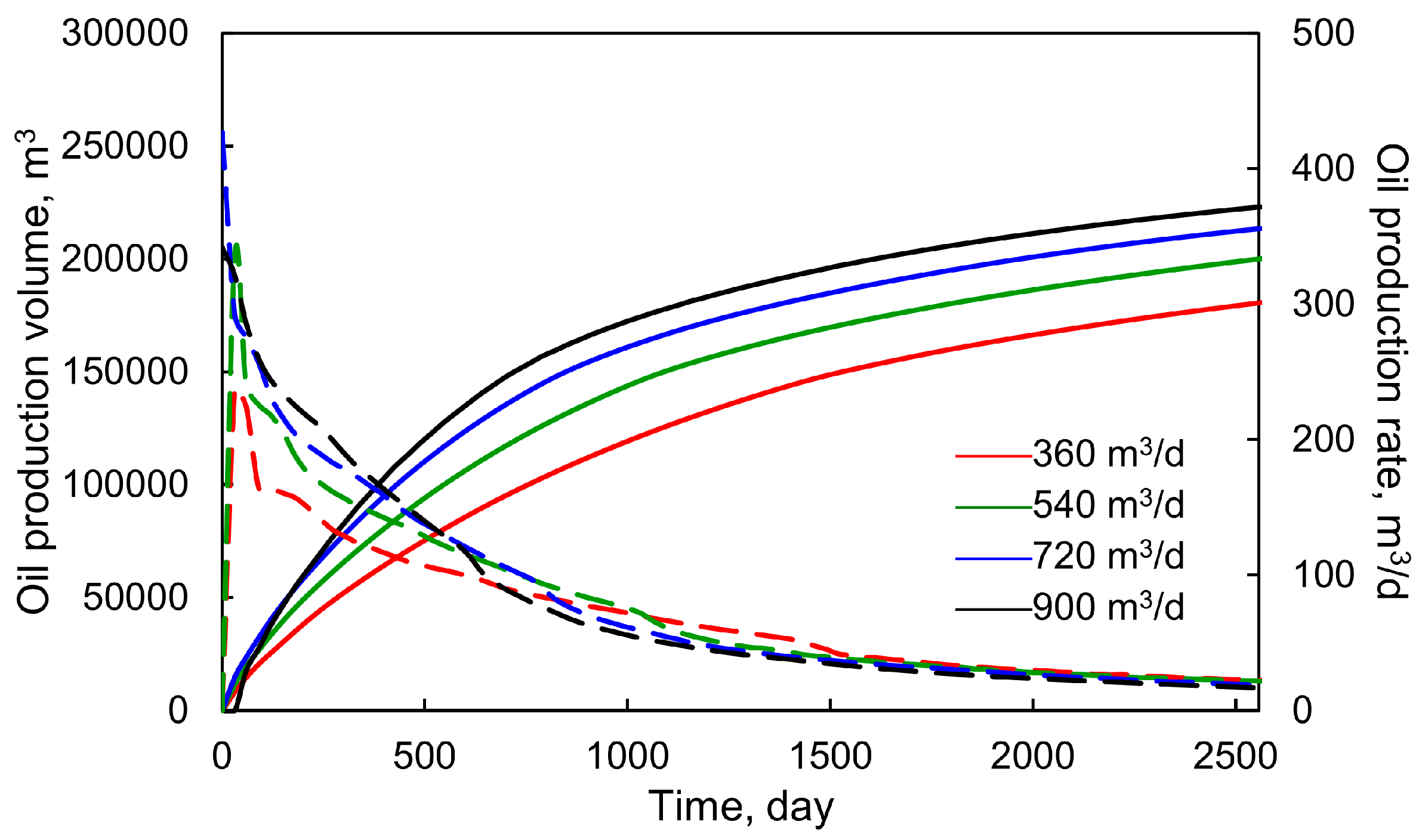

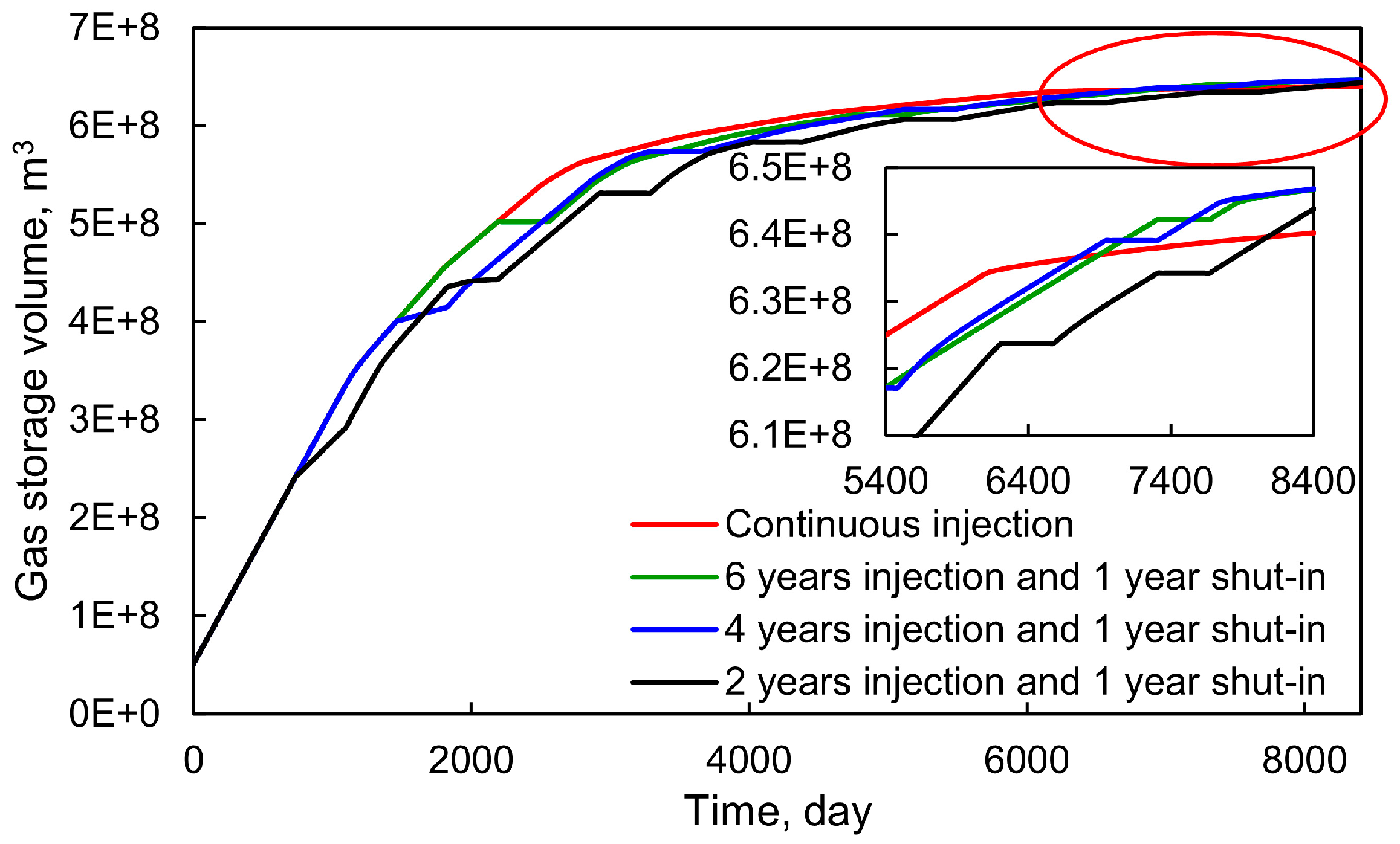

4.2.3. Intermittent Gas Injection

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Kennedy C, Steinberger J, Gasson B, et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from global cities. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Harindintwali J D, Yuan Z, et al. Technologies and perspectives for achieving carbon neutrality. The Innovation, 2021, 2(4): 100180.

- Rogelj J, Den Elzen M, Höhne N, et al. Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 C. Nature, 2016, 534(7609): 631-639. [CrossRef]

- d’Amore, Federico, Leonardo Lovisotto, and Fabrizio Bezzo. “Introducing social acceptance into the design of CCS supply chains: A case study at a European level.” Journal of Cleaner Production 249 (2020): 119337. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Zhuang Y, Tao R, et al. Multi-objective optimization for the deployment of carbon capture utilization and storage supply chain considering economic and environmental performance[. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020, 270: 122481. [CrossRef]

- Tapia J F D, Lee J Y, Ooi R E H, et al. A review of optimization and decision-making models for the planning of CO2 capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) systems. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 2018, 13: 1-15.

- Greig C, Uden S. The value of CCUS in transitions to net-zero emissions. The Electricity Journal, 2021, 34(7): 107004. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Dai Z, Romanak K D, et al. Inverse modeling of water-rock-CO2 batch experiments: Potential impacts on groundwater resources at carbon sequestration sites. Environmental science & technology, 2014, 48(5): 2798-2806. [CrossRef]

- Shaffer G. Long-term effectiveness and consequences of carbon dioxide sequestration. Nature Geoscience, 2010, 3(7): 464-467. [CrossRef]

- Bacon D H, Qafoku N P, Dai Z, et al. Modeling the impact of carbon dioxide leakage into an unconfined, oxidizing carbonate aquifer. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control, 2016, 44: 290-299. [CrossRef]

- Dai Z, Middleton R, Viswanathan H, et al. An integrated framework for optimizing CO2 sequestration and enhanced oil recovery. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 2014, 1(1): 49-54. [CrossRef]

- Bacon D H, Dai Z, Zheng L. Geochemical impacts of carbon dioxide, brine, trace metal and organic leakage into an unconfined, oxidizing limestone aquifer. Energy Procedia, 2014, 63: 4684-4707. [CrossRef]

- Nordbotten J M, Celia M A, Bachu S. Injection and storage of CO2 in deep saline aquifers: analytical solution for CO2 plume evolution during injection. Transport in Porous media, 2005, 58: 339-360. [CrossRef]

- Dai Z, Stauffer P H, Carey J W, et al. Pre-site characterization risk analysis for commercial-scale carbon sequestration. Environmental science & technology, 2014, 48(7): 3908-3915. [CrossRef]

- Godec M, Kuuskraa V, Van Leeuwen T, et al. CO2 storage in depleted oil fields: The worldwide potential for carbon dioxide enhanced oil recovery. Energy Procedia, 2011, 4: 2162-2169. [CrossRef]

- Haugan P M, Drange H. Sequestration of CO2 in the deep ocean by shallow injection. Nature, 1992, 357(6376): 318-320.

- Christensen J R, Stenby E H, Skauge A. Review of WAG field experience. SPE Reservoir Evaluation & Engineering, 2001, 4(02): 97-106.

- Gale J, Freund P. Coal-bed methane enhancement with CO2 sequestration worldwide potential. Environmental Geosciences, 2001, 8(3): 210-217. [CrossRef]

- Hamza A, Hussein I A, Al-Marri M J, et al. CO2 enhanced gas recovery and sequestration in depleted gas reservoirs: A review. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 2021, 196: 107685. [CrossRef]

- Cui G, Zhu L, Zhou Q, et al. Geochemical reactions and their effect on CO2 storage efficiency during the whole process of CO2 EOR and subsequent storage. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control, 2021, 108: 103335. [CrossRef]

- Brnak J, Petrich B, Konopczynski M R. Application of SmartWell technology to the SACROC CO2 EOR project: A case stud, DOE Symposium on Improved Oil Recovery. OnePetro, 2006.

- Global CCS Institute. Global Status of CCS 2023 – Report & Executive Summary. Melbourne: Global CCS Institute, 2023.

- Quintella C M, Dino R, Musse A P. CO2 enhanced oil recovery and geologic storage: an overview with technology assessment based on patents and article, International Conference on Health, Safety and Environment in Oil and Gas Exploration and Production. OnePetro, 2010.

- Ren B, Duncan I J. Reservoir simulation of carbon storage associated with CO2 EOR in residual oil zones, San Andres formation of West Texas, Permian Basin, USA. Energy, 2019, 167: 391-401. [CrossRef]

- Zhong Z, Liu S, Carr T R, et al. Numerical simulation of water-alternating-gas process for optimizing EOR and carbon storage. Energy Procedia, 2019, 158: 6079-6086. [CrossRef]

- Karimaie H, Nazarian B, Aurdal T, et al. Simulation study of CO2 EOR and storage potential in a North Sea Reservoir. Energy Procedia, 2017, 114: 7018-7032. [CrossRef]

- Wei J, Zhou X, Zhou J, et al. Experimental and simulation investigations of carbon storage associated with CO2 EOR in low-permeability reservoir. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control, 2021, 104: 103203. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Liu J, Su Y, et al. Influences of diffusion and advection on dynamic oil-CO2 mixing during CO2 EOR and storage process: Experimental study and numerical modeling at pore-scales. Energy, 2023, 267: 126567. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y Y, Wang X G, Dong R C, et al. Reservoir heterogeneity controls of CO2-EOR and storage potentials in residual oil zones: Insights from numerical simulations. Petroleum Science, 2023.

- Haro H A V, de Paula Gomes M S, Rodrigues L G. Numerical analysis of carbon dioxide injection into a high permeability layer for CO2-EOR projects. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 2018, 171: 164-174.

- Ampomah W, Balch R S, Grigg R B, et al. Optimization of CO2-EOR Process in Partially Depleted Oil Reservoirs, Western Regional Meeting. OnePetro, 2016.

- Imanovs E, Krevor S, Mojaddam Zadeh A. CO2-EOR and storage potentials in depleted reservoirs in the Norwegian continental shelf NCS, Europec. OnePetro, 2020.

- Liao H, Xu T, Yu H. Progress and prospects of EOR technology in deep, massive sandstone reservoirs with a strong bottom-water drive. Energy Geoscience, 2023: 100164. [CrossRef]

- Hannis S, Lu J, Chadwick A, et al. CO2 storage in depleted or depleting oil and gas fields: what can we learn from existing projects?. Energy Procedia, 2017, 114: 5680-5690. [CrossRef]

- Agartan E, Gaddipati M, Yip Y, et al. CO2 storage in depleted oil and gas fields in the Gulf of Mexico. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control, 2018, 72: 38-48. [CrossRef]

- Orlic B. Geomechanical effects of CO2 storage in depleted gas reservoirs in the Netherlands: Inferences from feasibility studies and comparison with aquifer storage. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, 2016, 8(6): 846-859. [CrossRef]

- Mo S, Akervoll I. Modeling long-term CO2 storage in aquifer with a black-oil reservoir simulator, doe exploration and production environmental conference. OnePetro, 2005.

- Li D, Saraji S, Jiao Z, et al. CO2 injection strategies for enhanced oil recovery and geological sequestration in a tight reservoir: An experimental study. Fuel, 2021, 284: 119013. [CrossRef]

- Saffou E, Raza A, Gholami R, et al. Geomechanical characterization of CO2 storage sites: A case study from a nearly depleted gas field in the Bredasdorp Basin, South Africa. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 2020, 81: 103446. [CrossRef]

- Sun Q, Ampomah W, Kutsienyo E J, et al. Assessment of CO2 trapping mechanisms in partially depleted oil-bearing sands. Fuel, 2020, 278: 118356. [CrossRef]

- Rasool M H, Ahmad M, Ayoub M. Selecting Geological Formations for CO2 Storage: A Comparative Rating System. Sustainability, 2023, 15(8): 6599. [CrossRef]

- Computer Modelling Group. CMG GEM – Compositional & Unconventional Simulator, 2019.

- Chen Z. Reservoir simulation: mathematical techniques in oil recovery. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 2007.

- Izgec O, Demiral B, Bertin H, et al. CO2 injection in carbonates. SPE western regional meeting. SPE, 2005.

- Peng D, Donald B R. A new two-constant equation of statea. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Fundamentals 15.1 (1976): 59-64.

- Narinesingh J, Boodlal D V, Alexander D. Feasibility study on the implementation of CO2-EOR coupled with sequestration in Trinidad via reservoir simulation, Energy Resources Conference. OnePetro, 2014.

- Phi T, Schechter D. CO2 EOR simulation in unconventional liquid reservoirs: an Eagle Ford case study, Unconventional Resources Conference. OnePetro, 2017.

- Alfarge D, Wei M, Bai B. Mechanistic study for the applicability of CO2-EOR in unconventional Liquids rich reservoirs, Improved Oil Recovery Conference. OnePetro, 2018.

- Hosseini S A, Alfi M, Nicot J P, et al. Analysis of CO2 storage mechanisms at a CO2-EOR site, Cranfield, Mississippi. Greenhouse Gases: Science and Technology, 2018, 8(3): 469-482.

- Haro H A V, de Paula Gomes M S, Rodrigues L G. Numerical analysis of carbon dioxide injection into a high permeability layer for CO2-EOR projects. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 2018, 171: 164-174.

- Holubnyak Y, Watney W, Rush J, et al. Reservoir Engineering Aspects of Pilot Scale CO2 EOR Project in Upper Mississippian Formation at Wellington Field in Southern Kansas. Energy Procedia, 2014, 63: 7732-7739. [CrossRef]

- Cao R, Knapp J, Bikkina P, et al. CO2 Storage Potential Reconnaissance of the Newly Identified Red Beds of Hazlehurst in the Southeastern United States. Frontiers in Energy Research, 2021, 9: 793300. [CrossRef]

- Burton M M, Bryant S L. Eliminating buoyant migration of sequestered CO2 through surface dissolution: implementation costs and technical challenges. SPE Reservoir Evaluation & Engineering, 2009, 12(03): 399-407. [CrossRef]

- Pentland C H, Itsekiri E, Al Mansoori S K, et al. Measurement of nonwetting-phase trapping in sandpacks. Spe Journal, 2010, 15(02): 274-281. [CrossRef]

- Pruess K, Xu T, Apps J, et al. Numerical modeling of aquifer disposal of CO2. Spe Journal, 2003, 8(01): 49-60. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Long X N. Phase equilibria of oil, gas and water/brine mixtures from a cubic equation of state and Henry’s law. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering 64.3 (1986): 486-496.

- Yu Z, Liu L, Liu K, et al. Petrological characterization and reactive transport simulation of a high-water-cut oil reservoir in the Southern Songliao Basin, Eastern China for CO2 sequestration. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control, 2015, 37: 191-212. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Wang W, Su Y, et al. Assessment of CO2 storage potential in high water-cut fractured volcanic gas reservoirs—Case study of China’s SN gas field. Fuel, 2023, 335: 126999. [CrossRef]

| Septal interlayer | Composition | Mechanisms of formation |

| Muddy | Mudstones, siltstones, muddy siltstones, shales | Sedimentation due to diminished hydrodynamics, with complete sheltering effect. |

| Calcareous | Calcareous siltstones, calcareous mudstones, calcareous shales | Related to the unevenness of the carbonate formation and dissolution, it is found at the junction of the top and base of the sandstone with the mudstone. With complete sheltering effect. |

| Stratigraphy | Sand, mud | Partially sheltered. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).