1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) faces a number of mathematical challenges, including optimization, generalization, model interpretability, and phase transitions. These issues significantly restrict AI’s applicability in critical fields such as medicine, autonomous systems, and finance. This article explores the core mathematical problems of AI and proposes solutions based on the universality of the Riemann zeta function. Moreover, AI, as a dominant trend into which hundreds of billions of dollars are being invested, is now responsible for solving humanity’s most intricate problems, such as nuclear fusion, turbulence, the functioning of consciousness, the development of new materials and medicines, genetic challenges, and disasters like earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis, as well as climatic, ecological, and social upheavals, with the ultimate goal of advancing civilization to a galactic scale. All these challenges, whether explicitly mentioned or not, are tied together by the problem of prediction and the issue of "black swans" within existing problems. This work provides an analysis of AI’s challenges and some approaches to overcoming them, which, in our opinion, will reinforce certain existing trends laid down by our great predecessors, which we assume will become central in mastering AI.

Currently, we are witnessing remarkable progress in the field of AI. The successes of AI are paving the way for the emergence of a Global Intelligence (GI). However, concerns about electricity consumption cast doubt on its imminent realization. We believe that the only hope lies in the universality of the Riemann zeta function and its constructive application. This hope was articulated by the fathers of modern mathematics, who saw the Riemann Hypothesis as a kind of "Holy Grail" of science, the discovery of which would yield immeasurable knowledge. As the great mathematician David Hilbert once said, when asked what would interest him 500 years from now: "Only the Riemann Hypothesis." It is fitting here to admire all our predecessors who envisioned the development of science and humanity across millennia.

The mathematical foundations of artificial intelligence encompass several key areas, including probability theory, statistics, linear algebra, optimization, and information theory. These disciplines provide the necessary tools to tackle the complex tasks associated with AI learning and development. However, despite significant progress in this field, AI faces a growing number of mathematical challenges that must be addressed for the further effective advancement of AI technologies.

2. Problem Statement

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in electricity consumption due to the development of AI. For instance, statistical data indicate that AI’s electricity consumption rose from 0.1% of global usage in 2023 to 2% in 2024. Additionally, the catastrophic rise in water consumption for cooling the processors that support AI must be noted. This growth implies either a slowdown in AI development due to energy resource constraints, the creation of new energy sources, or the development of more efficient computational algorithms capable of significantly reducing energy costs. Therefore, we will focus here on the mathematical problems and algorithms that address them, while simultaneously consuming vast amounts of energy and water in super data centers when implemented in programs.

In this article, we will review the key mathematical disciplines currently known to play a vital role in AI development, analyze the problems limiting its effective application due to colossal energy demands, and propose our approaches based on global scientific achievements, systematizing them for AI advancement and energy reduction. Below are the mathematical problems that lead to energy consumption.

Here, it is appropriate to recall an analogy with young Gauss, who was tasked with summing numbers from one to a million sequentially. Instead, he derived the formula for the sum of an arithmetic progression, reducing the task to three operations instead of a million. Now, consider that each addition cycle in a computer consumes energy, and using his three-step formula reduces energy costs by tens of thousands of times in this case. Thus, methods for solving equations as a means of conservation were developed by young Gauss. One could say he replaced endless abacus clicking with three actions!

Another genius, Riemann, suggested that the zeta function is the "Grail of science," while Hilbert decided to wait 500 years for its resolution, building on the work of G. Leibniz, one of the first to study conditionally convergent series. Leibniz also introduced the concept of signs in series and demonstrated that some series could converge. Banach and Tarski contributed to understanding permutation properties, describing them in the context of more abstract mathematical structures and showing that conditionally convergent series can change their sum under rearrangement. These classics laid the foundation for the modern approach to the "Grail of science," anticipating that it would open the gates to the future. These works enabled S. Voronin to arrive at the universality of the zeta function. Our goal is to demonstrate that this "Grail of science" indeed leads us to the future through the collective efforts of our contemporaries—toward Global Intelligence. Furthermore, this "Grail of science" leads to solving fundamental problems of humanity, such as turbulence, and, consequently, achieving the long-awaited control of nuclear fusion.

3. Mathematical Disciplines and Their Problems

Probability Theory and Statistics: Probability theory and statistics form the basis for modeling uncertainty and training AI. These disciplines provide tools for building predictive models, such as Bayesian methods and probabilistic graphical models.

Problems: The main challenges relate to uncertainty estimation, handling incomplete and noisy data. Probabilistic models require significant computational resources to account for all uncertainty factors.

Linear Algebra: Linear algebra is used for data analysis, working with high-dimensional spaces, and performing basic operations in neural networks. It is also crucial for dimensionality reduction methods, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Problems: As data volumes grow, the computational complexity of operations in high-dimensional spaces increases exponentially, leading to the so-called "curse of dimensionality."

Optimization Theory: Optimization underpins most machine learning algorithms. Gradient descent and its variants are used to minimize loss functions and find optimal solutions.

Problems: Key challenges include the presence of local minima, slow convergence, and complexity in multidimensional spaces, requiring substantial computational resources.

Differential Equations: Differential equations are employed to model dynamic systems, such as recurrent neural networks and LSTMs. They are essential for describing changes over time and forecasting based on data.

Problems: Nonlinear differential equations are difficult to solve in real time, making their application computationally expensive.

Information Theory: Information theory plays a critical role in encoding and transmitting data with minimal loss. It is also vital for minimizing entropy and enhancing the efficiency of model training.

Problems: Balancing entropy and data volume, especially in the presence of noisy data, is a complex task requiring significant computational resources.

Computability Theory: Computability theory helps determine which tasks can be solved algorithmically and where the limits of AI applicability lie.

Problems: Identifying tasks that are fundamentally unsolvable by algorithmic methods, particularly in the context of creating strong AI.

Stochastic Methods and Random Process Theory: These methods are used to handle uncertainty and noise, including in algorithms like Monte Carlo methods and stochastic gradient descent.

Problems: Optimizing random processes under resource constraints remains a difficult challenge.

Neural Networks and Deep Learning: Deep neural networks are complex multilayer structures involving linear transformations and nonlinear activation functions. These networks are widely applied to AI tasks such as pattern recognition and natural language processing.

Problems: Key issues include the interpretability of neural network decisions, overfitting, and generalization. Addressing these requires significant computational resources.

4. Problem Detailing

Probability Theory and Statistics - Probabilistic methods are central to machine learning and AI, particularly in tasks like supervised and unsupervised learning. Bayesian methods, probabilistic graphical models, and maximum likelihood techniques are employed. - Problems: A primary mathematical challenge lies in uncertainty estimation and developing methods for probabilistic models in the presence of incomplete or heavily noisy data.

Problems: These include uncertainty estimation, handling incomplete data, and noise. Probabilistic models must be flexible enough to account for all these factors.

Linear Algebra: Used for data analysis and working with high-dimensional spaces, which is critical for neural networks and dimensionality reduction methods like PCA. - Analysis of data and operations in high-dimensional spaces are vital aspects of machine learning and AI tasks, especially for neural networks. High data dimensionality increases computational and modeling complexity, making efficient methods for processing such data essential. - Methods like PCA (Principal Component Analysis) are used to reduce the number of features (variables) while preserving the most significant information. PCA identifies the main directions of data variation, enabling: - Reduction of computational volume; - Decreased likelihood of overfitting; - Improved data visualization in 2D and 3D; - Faster model training. - This method extracts key components, which is particularly important in tasks with thousands of features, such as image processing, text analysis, or genetic data, where the original data is high-dimensional.

Problems: The curse of dimensionality, where working with large datasets becomes computationally complex.

Optimization Theory: Forms the foundation of most learning algorithms. Gradient descent and its modifications are applied to minimize loss functions.

Problems: Local minima and slow convergence in multidimensional spaces remain challenges.

Differential Equations: Used to model dynamic systems, such as recurrent neural networks and LSTMs.

Problems: Solving nonlinear differential equations in real time poses a significant mathematical difficulty.

Information Theory: Assesses how to encode and transmit information with minimal loss, relating to entropy reduction and minimizing losses in model training.

Problems: Balancing entropy and data volume when training models with noise.

Computability Theory: Crucial for determining tasks solvable by algorithms and exploring AI’s limits.

Problems: Tasks that are fundamentally unsolvable by algorithmic means, especially in the context of strong AI.

Computability Theory: The primary task of this theory is to determine which problems can be solved algorithmically and to study the boundaries of computation. It plays a key role in understanding which tasks are computable and which are not, particularly relevant to developing efficient AI algorithms.

Problems: In the context of strong AI, a major issue is intractable problems that cannot be solved algorithmically, such as the halting problem. This imposes fundamental limits on creating a strong AI capable of solving any task. Other problems, like computing all consequences of complex systems or handling chaotic dynamics, may also be incomputable within existing algorithmic frameworks.

Stochastic Methods and Random Process Theory: These methods are applied in AI algorithms to manage uncertainty and noise, such as in Monte Carlo methods and stochastic gradient descent.

Problems: Efficiently handling uncertainty and optimizing random processes under limited resources.

Stochastic Methods and Random Process Theory: Stochastic methods are widely used in AI to address uncertainty, noise, and probabilistic models. Examples include the Monte Carlo method, used for numerical modeling of complex systems via random sampling, and stochastic gradient descent (SGD), applied to optimize parameters in neural networks with large datasets. - Monte Carlo Method: Employed for numerical simulation of complex systems by generating numerous random samples. This method is particularly useful when analytical solutions are impossible or overly complex. In AI, Monte Carlo is used in planning tasks, such as Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) in games and strategic modeling. - Stochastic Gradient Descent: Used for optimizing models with large datasets. Unlike classical gradient descent, which updates parameters based on the entire dataset, SGD does so using random subsets, speeding up training, especially in deep neural networks, and helping avoid local minima traps. - Problems: - Efficient Uncertainty Handling: Stochastic methods often struggle to accurately model complex systems, relying on large data volumes or numerous samples, which can slow training and optimization. Uncertainty in data distribution and structure can lead to significant prediction deviations and complicate training. - Optimization with Limited Resources: Real-world AI systems often face computational and memory constraints. Monte Carlo methods demand substantial computational power for accurate results, especially in high-parameter or complex dynamic tasks. Meanwhile, SGD can suffer from high volatility, necessitating multiple runs with varying initial conditions. - Accuracy vs. Speed Tradeoff: Stochastic methods face a dilemma: balancing prediction accuracy and computation speed. For instance, increasing Monte Carlo sample sizes improves accuracy but extends computation time, critical in real-time applications with limited resources and a need for rapid decisions.

Thus, optimizing stochastic processes under resource constraints remains a key challenge in applying these methods to AI, especially in systems requiring large data processing or real-time operation.

Neural Networks and Deep Learning: Deep neural networks are based on multilayer structures involving linear transformations and nonlinear activation functions.

Problems: The primary issue is the explainability (interpretability) of neural network decisions, alongside overfitting and generalization.

Neural Networks and Deep Learning: Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) consist of multiple layers, each performing linear transformations on input data followed by nonlinear activation functions. These layers enable the detection of complex, multidimensional relationships in data, making neural networks highly effective for tasks like image recognition, speech processing, and text analysis.

Problems: 1. **Explainability (Interpretability)**: - A major challenge in deep learning is the lack of transparency in model operation, rendering them "black boxes." With thousands or millions of parameters, interpreting how deep neural networks arrive at specific decisions is difficult. This raises trust issues in AI systems, especially in critical applications like medicine or finance, where understanding the decision-making process is vital. - Methods to address this include: - **LIME** (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations): Provides local interpretations for individual predictions. - **SHAP** (SHapley Additive exPlanations): A game-theory-based algorithm evaluating each feature’s contribution to a prediction. - **Neuron Activation Analysis**: Visualizing how specific layers and neurons respond to input data to better understand what the network learns at each stage.

2. **Overfitting**: - Overfitting occurs when a model learns the training data too well, memorizing its specifics rather than general patterns. This degrades performance on new, unseen data, impairing generalization. - Strategies to combat overfitting: - **Regularization**: Techniques like L2 regularization (weight decay) penalize overly large weights, limiting model complexity. - **Dropout**: Randomly dropping neurons during training to prevent excessive adaptation to training data. - **Early Stopping**: Halting training when performance peaks on validation data, before overfitting occurs.

3. **Generalization**: - Generalization is a model’s ability to perform well on new, unseen data, directly tied to the overfitting problem. The goal is to develop models that capture core data patterns rather than noise or random correlations. - Ways to improve generalization: - **Data Augmentation**: Generating additional training data through random modifications (e.g., image rotation, noise addition) to help models learn broader features. - **Simpler Models**: Models with fewer parameters often generalize better than overly complex ones. - **Cross-Validation**: Techniques like k-fold cross-validation provide insight into a model’s generalization across different data subsets.

5. The Main Result and Its Consequences

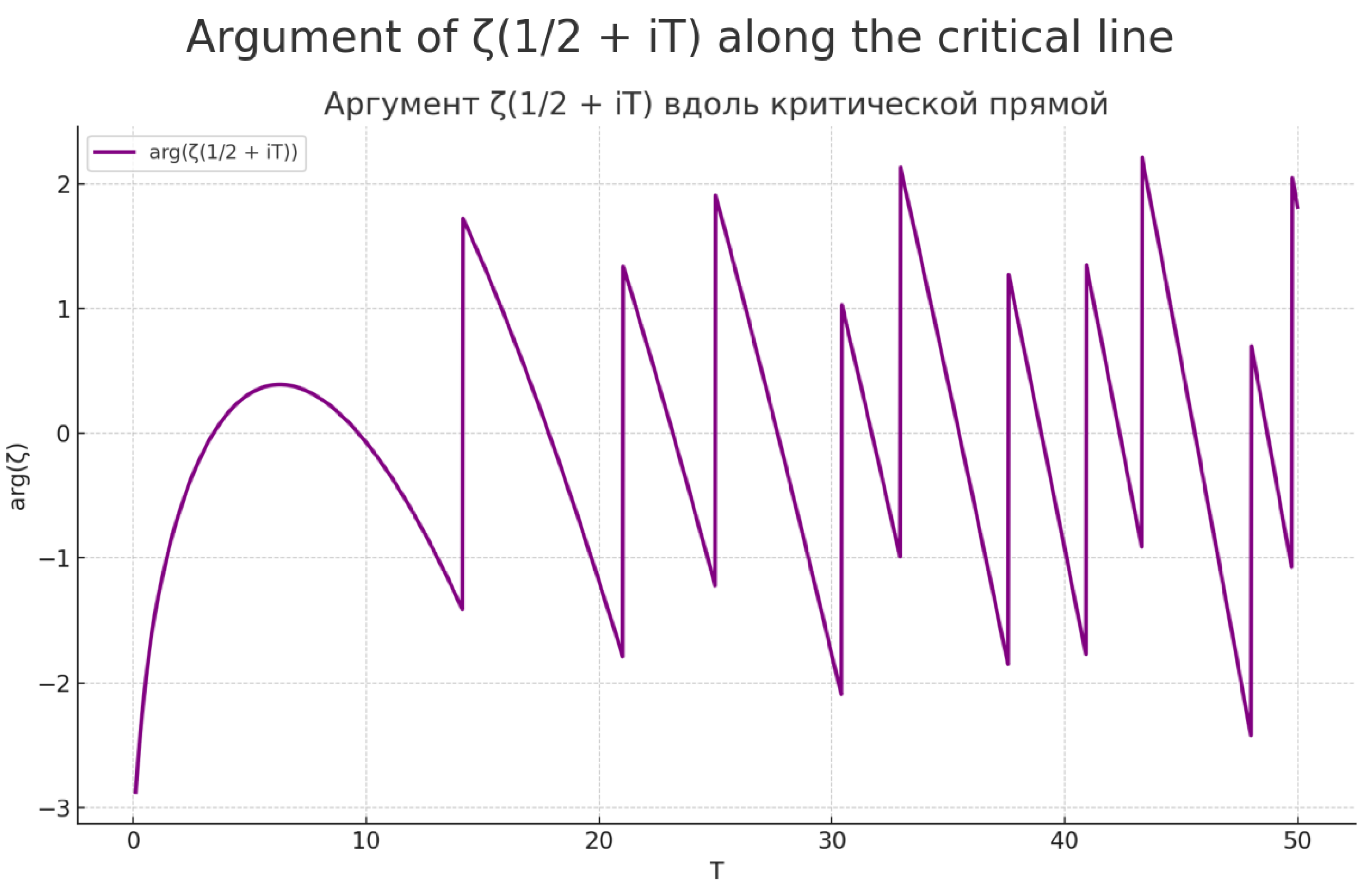

In this section, we present the main mathematical results that could serve as a unified foundation for overcoming the mathematical problems of AI outlined above. We begin by presenting these results with an image depicting this function in

Figure 1.

In [

6], Voronin proved the following universality theorem for the Riemann zeta function. Let

D be any closed disc contained in the strip

. Let

f be any non-vanishing continuous function on

D which is analytic in the interior of

D. Let

. Then there exist real numbers

t such that

Voronin mentions in [

6] that the analogue of this result for an arbitrary Dirichlet

L-function is valid.

In [

7],

Theorem (Joint universality of Dirichlet L-function):

Let

, and let

be distinct Dirichlet characters modulo

k. For

, let

be a simply connected compact subset of

, and let

be a non-vanishing continuous function on

, which is analytic in the interior (if any) of

. Then the set of all

for which

has positive lower density for every

.

Constructive Universality of the Riemann Zeta Function, developed in [

12,

13]:

Theorem: Constructive Universality of the Zeta Function:

and its zeros can be used for global approximation of loss functions and avoiding local minima. The theorems formulated above open opportunities to consider zeta functions as key points for analyzing high-dimensional loss function spaces [

8]. This will accelerate the optimization process and achieve better convergence. The critical line and zeros of the zeta function are depicted in

Figure 2.

6. Universality of the Riemann Zeta Function as a Unified Mathematical Foundation for AI Problems

Consider the first mathematical problem of AI—probability. Naturally, probability theory is a vast field, but selecting an appropriate measure to describe current processes becomes problematic, especially under turbulent conditions. We believe that results linking quantum statistics with the zeros of the zeta function could serve as a foundation for resolving both the turbulence problem and the task of constructing measures for AI. Such possibilities are provided by the theorems of Berry, Keating, Montgomery, Odlyzko, and Durmagambetov [

2,

3,

8,

12,

13].

Replacing random measures with quantum statistics based on zeta function zeros in the context of AI and Global AI represents an intriguing and profound research direction. This offers a new approach to modeling uncertainty, learning, and prediction in complex systems.

1. Quantum Statistics and Uncertainty in AI: In modern AI systems, uncertainty is often modeled using probabilistic methods like Bayesian networks, stochastic processes, and distributions. Quantum statistics could provide more precise methods for describing uncertainty. The zeros of the zeta function could serve as generators of statistical measures for complex dynamic systems where uncertainty and chaotic behavior are key.

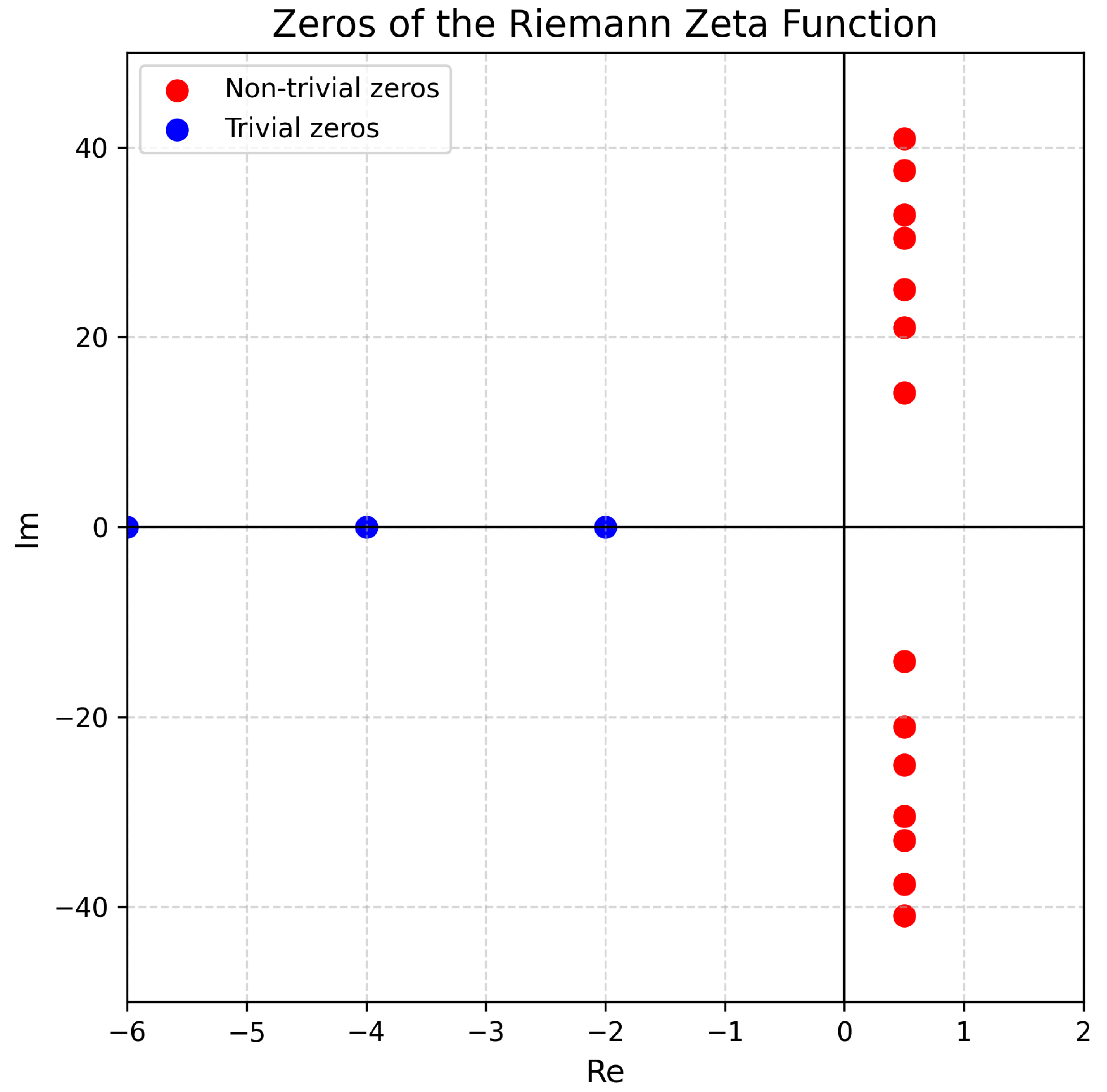

The figure reflecting the connection between zeros and quantum statistics is shown in

Figure 3, obtained from [

3].

2. Connection to Global AI: The task of building Global AI (AGI) involves creating an AI capable of solving a wide range of problems at a level far surpassing human intelligence. This requires robust methods for handling incomplete information and complex dependencies. The zeros of the zeta function could enhance AGI’s ability to predict chaotic and complex dynamics in real time.

3.

Prior Measure for Bayesian AI Systems: Choosing a prior measure in Bayesian AI systems is a significant challenge. Replacing classical prior measures with a distribution based on zeta function zeros could improve the determination of initial probabilities under uncertainty, as the measure of chaos is the distribution of zeta function zeros, as shown in [

2,

3,

8].

4.

Quantum AI: Combining quantum computing and AI could significantly accelerate training and data processing. The zeros of the zeta function could underpin the creation of probabilistic models in quantum AI, where quantum superposition and entanglement enhance computational capabilities. For the transition to quantum AI, we propose relying on the results of Berry, Keating, Montgomery, Odlyzko, and Durmagambetov [

2,

3,

8,

12,

13], which enable these results to form a robust theory.

7. Linear Algebra

The primary problem in using linear algebra methods in AI is the growth of data dimensionality. Within the framework of constructive universality theory, this problem reduces to replacing datasets with a single point representing the entire dataset. Transformations such as the Hilbert transform or Fourier transform can be reduced to analytic functions constructively encoded by a single point on the complex plane, according to Voronin’s universality theorem and implemented in [

12].

Differential Equations: Differential equations are used to model dynamic systems like recurrent neural networks and LSTMs. To study differential equations via the zeta function, consider equations of the form:

For

, we introduce the operators

and

T as follows:

where

, and

. Using the analyticity of

and the results of [

12,

13], we can formulate:

We reduce the problem’s solution to constructing the trajectory of the parameter s. Since we operate between the zeros of the Riemann zeta function, this simultaneously addresses the task of determining turbulence onset—finding the point where parameter k hits a zeta function zero. This allows tracking which zero we encounter and understanding the nature of the resulting instability. This approach provides a significant leap in understanding the nature of phenomena and could serve as a basis for describing phase transitions, thereby addressing the "black swan" problem.

This method resolves the issue of phase transitions for both AI and technologies for producing new materials. Additionally, in the context of financial markets, it can describe the "black swan" phenomenon. In medicine, this approach describes critical health states, while in nuclear fusion, it helps avoid operational regime disruptions.

8. Information Theory

Information theory evaluates how to encode and transmit information with minimal loss, relating to entropy reduction and minimizing losses in model training.

Problems: Balancing entropy and data volume when training noisy models is a complex task. The universality of the zeta function offers a new approach to encoding and decoding data: signals are replaced by points on the critical line. This fundamentally changes training technology—instead of training on large data volumes, the process focuses on key points along the critical line. In regions near zeta function zeros, training will yield opposite results with minimal data changes.

9. Computability Theory

Computability theory is essential for identifying tasks solvable by algorithms and studying AI’s limits. Tasks can now be classified for each input dataset located between two zeta function zeros. By the universality theorem, all datasets transition to points on the critical line. We can observe cyclic processes or transitions to critical points—zeta function zeros. Process termination may occur either by approaching a zero or by near-periodicity, according to Poincaré’s theorem and the boundedness of functions between two zeros. This also precisely describes the problem of phase transitions and the shift from one stable regime to another via turbulence.

10. Optimization Problems

Local minima and slow convergence in multidimensional spaces pose significant challenges. The universality of the zeta function and its tabulated values help eliminate these issues, reducing them to simple computational tasks. Optimizing stochastic processes under limited resources remains a critical challenge, especially in AI systems requiring large data processing or real-time operation.

11. Neural Networks and Deep Learning

Deep neural networks consist of multilayer structures with linear transformations and nonlinear activation functions. Multilayer neural networks can be viewed as layered "boxes" constructed from zeta function zeros. Considering all zeta function zeros yields an infinite-layer neural network capable of performing Global Intelligence functions. Activation functions can be regarded as phases of zeta function zeros.

11.1. Understanding Intelligence Through the Zeta Function

Processes described by zeta function values to the right of the line in the critical strip correspond to the observable world. Those described by values to the left are their reflections, symbolizing fundamental processes influencing the physical world. This symmetry underscores the zeta function’s importance in understanding AI. AI focuses on prediction, and zeta function values can be seen as part of this prediction.

Suppose we observe a process occurring simultaneously in the brain (computer, sensor) and externally. The universality of the zeta function lies in its ability to describe both processes. For instance, signal registration by sensors and subsequent record decoding can be described via the zeta function. Interpretation becomes a shift from one point to another on the critical line. Our task then is to study correlation and attention to these correlations.

11.2. Interpretability and the Future of Global Intelligence

A Global Intelligence will be capable of analyzing and predicting processes based on both explicit and hidden aspects. The nonlinear symmetry of the zeta function provides a new metaphor for solving AI interpretability issues, making it more predictable and efficient, as outlined across all aspects of our study. AI development is directly tied to understanding human intelligence, requiring deep insight into brain functioning.

We propose that the remarkable symmetry inherent in living organisms may be linked to the zeta function’s symmetry, representing a computational system that implements prediction mechanisms through its zeros. Fully decoding the brain’s hemispheres and their connection to zeta function symmetry seems a natural step toward creating Global Intelligence and understanding both AI and brain operation.

An example of this process is the visual system’s functioning. Vision is inherently a two-dimensional sensor system, yet through holographic processing in the brain, it transforms into three-dimensional images. We suggest that retinal follicles could be interpreted as a natural realization of zeta function zeros. This hypothesis elucidates how information received by the retina is processed by the brain, synchronized with biorhythms like the heartbeat, which acts as the brain’s "clock generator."

Thus, the right brain hemisphere processes data tied to the right side of the zeta function’s critical line, while the left hemisphere handles the left side. This synchronous process forms the perception of temporal and spatial coordinates, creating awareness of past and present.

Extending this idea about brain operation, we can hypothesize that similar principles govern the Universe. For instance, black holes might be associated with zeta function zeros, leading to a deeper understanding of microcosm and macrocosm principles, which humanity has contemplated since ancient times.

Let us systematize the zeta function by its imaginary parameter and show that it can be interpreted as temperature.

Abstract: We demonstrate that the energy distribution dependent on temperature matches the shape of the zeta function’s modulus on the critical line. This observation opens the possibility of a profound connection between microphysics, statistical mechanics, quantum theory, and analytic number theory. We substantiate the fundamental unity of temperature and the zeta function’s imaginary parameter within the critical curve framework and propose a model where the zeta function’s critical line serves as the boundary between macro- and micro-worlds.

Further reasoning leads us to conclude that the zeta function is the very matrix forming the world. The Riemann Hypothesis and its connection to quantum mechanics are subjects of active theoretical research. Specifically, the statistical properties of zeta function zero distributions on the critical line exhibit behavior akin to energy levels in quantum chaotic systems.

We propose interpreting the imaginary part of the zeta function’s argument as analogous to thermodynamic temperature.

Energy Distribution and the Zeta Function: In many thermodynamic systems, energy distribution is described by a function where temperature T determines the probabilities of the system occupying various energy states. Numerical experiments by Odlyzko showed that the distribution of imaginary parts of Riemann zeta function zeros on the critical line exhibits statistics similar to energy level distributions in quantum chaotic systems, described by Gaussian Unitary Ensembles (GUE) (Montgomery, Odlyzko, 1973–2000).

Quantum Statistics and Zero Distribution: According to the Hilbert–Pólya conjecture, there exists a self-adjoint Hamiltonian whose spectrum matches the imaginary parts of zeta function zeros. Thus, each zeta function zero can be interpreted as a quantum system’s energy state. This idea was further developed by Michael Berry and Jonathan Keating, who proposed the Hamiltonian as a potential model for generating the zeta function zero spectrum.

Critical Line as a Boundary Between Worlds: We propose interpreting the critical line as a boundary between the macro- and micro-worlds. Along this line, temperature (the imaginary part s) governs the transition from quantum states to classical structures. Thus, the zeta function’s behavior near the critical line may reflect physical transitions and phase changes. Similar ideas are traced in noncommutative geometry and statistical mechanics in the works of Alain Connes and Matilde Marcolli (Connes & Marcolli, 2004).

Turbulence and Distribution Evolution: Turbulent systems in physics are described by complex energy structures. If we accept the zeta function as a generator of energy states, the distribution of its zeros becomes analogous to the energy density function in a turbulent flow. We hypothesize that the evolution of the imaginary argument (temperature) determines fluctuations in these systems. The problem of constructing consistent measures to describe the interaction of current and energy fluctuations in a turbulent medium is a central challenge in turbulence theory. Our hypothesis—interpreting temperature as the imaginary part of the zeta function argument—offers a solution by linking quantum statistics, temperature evolution, and bifurcations, previously considered one of the most complex unresolved problems in turbulence description.

Information Structure of Physical Reality: As a practical application of this hypothesis, consider describing plasma processes in the context of nuclear fusion. Plasma in controlled fusion setups exhibits complex dynamics tied to turbulent fluctuations, energy spectra, and temperature gradient distributions. We propose that the zeta function’s informational component, described by its imaginary argument, can be used to build new models for controlling plasma states. The connection between quantum statistics, temperature evolution, and zeta function zeros enables describing plasma behavior via energy state distributions. This, in turn, creates a theoretical foundation for developing new methods to stabilize and control fusion plasma based on analyzing the zeta function’s structure and its relation to informational transfer and energy mode dynamics.

Continuing this line, we can assert that as temperature changes during nuclear fusion, the plasma state undergoes a sequence of phase transitions. In this context, zeta function zeros reflect these transitions and serve as quantitative characteristics of phase states. The primary challenge in plasma control, in our view, lies in the fact that each phase transition radically alters the physical system’s description, rendering control effective for one phase inapplicable to another. The need to account for the structure of phase transitions, reflected in the zeta function zero distribution, constitutes the core difficulty in managing fusion plasma. Our interpretation provides a tool for describing and predicting such transitions based on a universal mathematical object—the Riemann zeta function.

Thus, the proposed concept can be applied to describe and potentially control macroscopic nonlinear processes, particularly in achieving sustainable nuclear fusion.

The alignment between the zeta function and energy distribution suggests a deep informational component in physical reality. Temperature, as a parameter determining movement along the critical curve, becomes an indicator not only of energy state but also of the system’s informational content.

Extending our concept, we can assert that as a physical process’s temperature changes, the state of matter undergoes an infinite number of phase transitions. Here, Riemann zeta function zeros can be viewed as quantitative markers of these phase transitions. Thus, each phase transition corresponds to a specific zero, and the set of such zeros describes the system’s full spectral dynamics during temperature evolution. This assertion reinforces the fundamental link between the zeta function’s analytic structure and physical reality, encompassing both macro- and microscopic description levels.

We propose interpreting temperature as the imaginary part of the Riemann zeta function argument. This unifies quantum mechanics, thermodynamics, and number theory within a single conceptual framework. The critical line becomes the transition boundary between different physical reality levels, while the zeta function zero distribution serves as a universal model for describing energy, statistical, and informational processes.

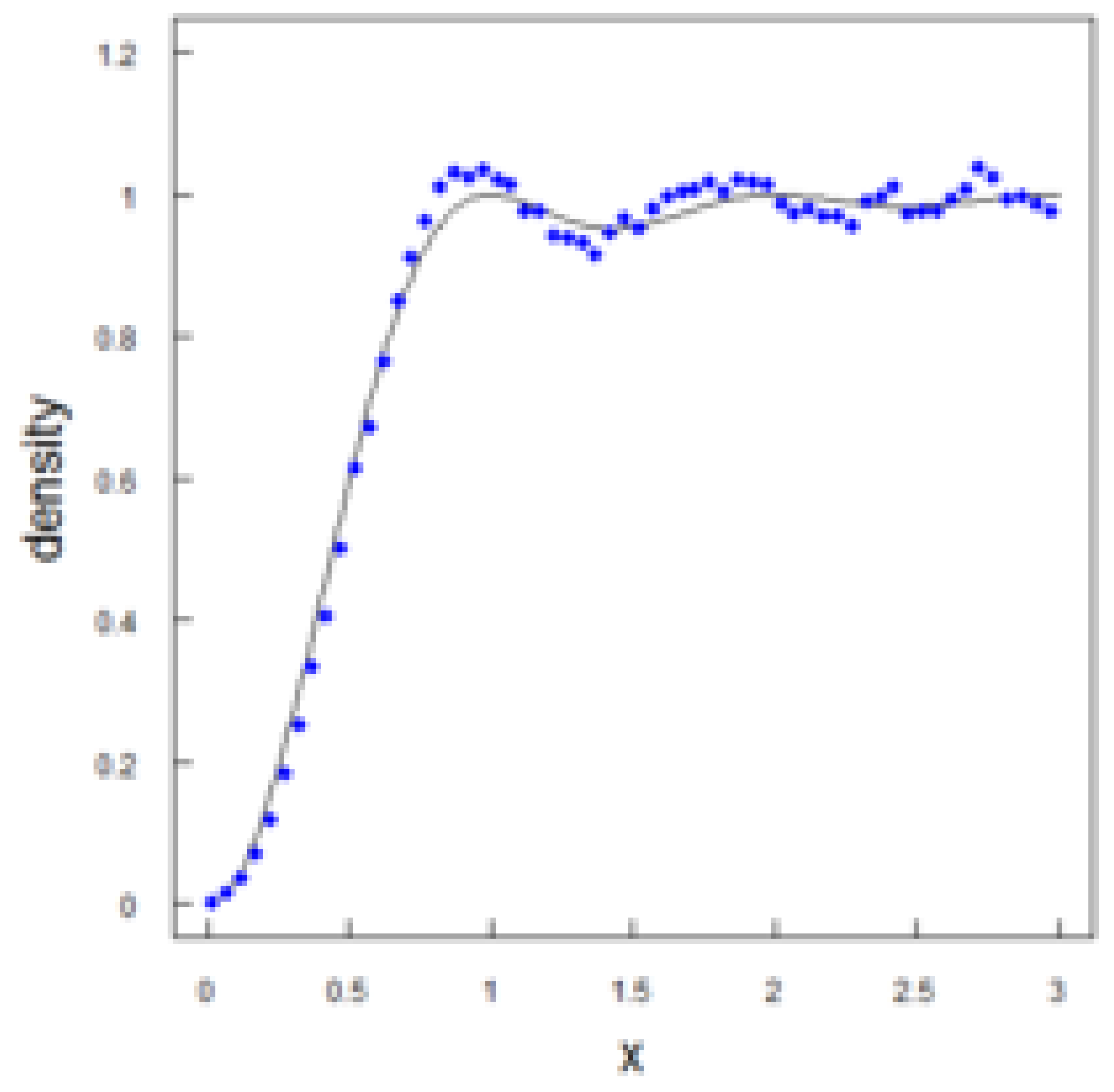

We introduce the function:

which will explain our reasoning in greater detail based on its behavior and comparison with fundamental distributions.

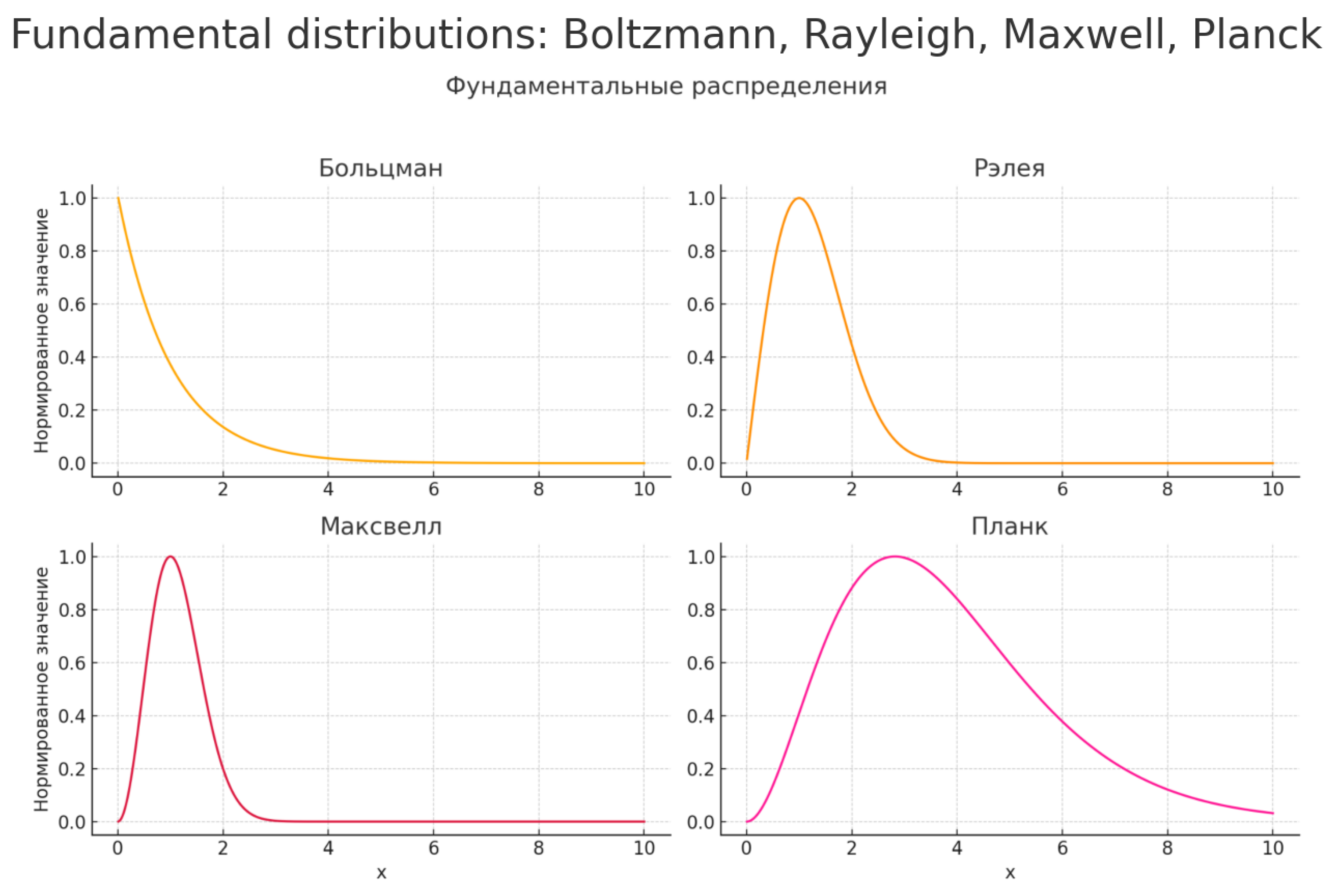

Figure 4.

Comparison of distributions: Boltzmann, Rayleigh, Maxwell, Planck

Figure 4.

Comparison of distributions: Boltzmann, Rayleigh, Maxwell, Planck

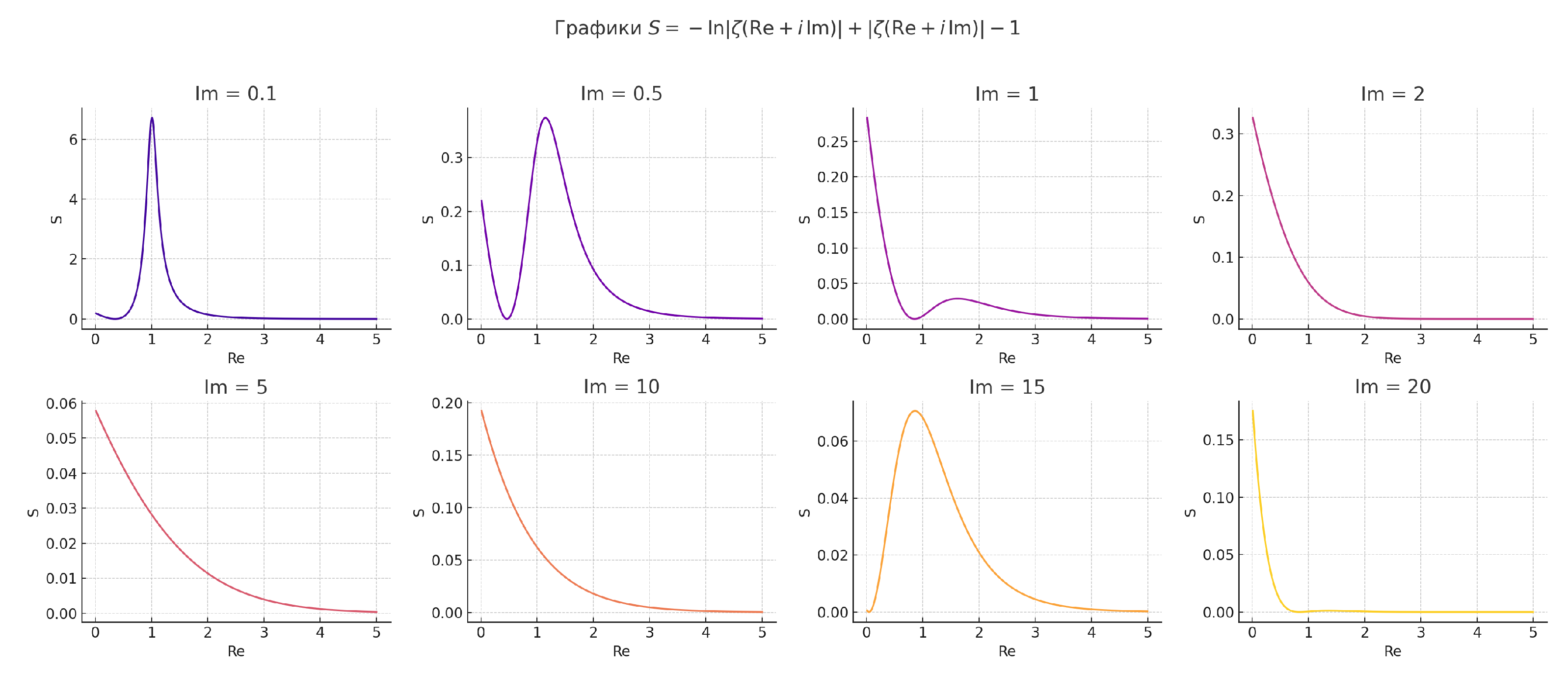

Figure 5.

Graphs of at various Im values

Figure 5.

Graphs of at various Im values

Family of Distributions Generated by the Zeta Function

The function

represents a fundamental construct that, by varying the imaginary part

, yields curves matching the shapes of key distributions used in statistical physics and quantum theory.

Figure 6.

Graphs of at various Im values

Figure 6.

Graphs of at various Im values

Each fixed value of corresponds to a curve , which, when normalized, reproduces known distributions:

at —a sharp peak, analogous to the Planck distribution (blackbody radiation);

at —curves close in shape to the Rayleigh distribution;

at —smooth decaying curves corresponding to the Boltzmann distribution;

at large —smooth distributions similar to the Maxwell speed distribution of particles.

Thus, varying the imaginary part of the zeta function argument yields a family of measures reflecting fundamental physical states—from excited to equilibrium.

Measures Generating Thermodynamics

These distributions derived from the function S possess all the properties of probabilistic measures used in statistical physics. Moreover, they naturally generate:

Thus, the concept of specific heat capacity requires no additional introduction—it naturally emerges as the derivative of the function S derived from the zeta function.

Universality and Physical Connectivity

Since all these distributions stem from a single analytic object—the Riemann zeta function—they not only describe known physical processes but also:

are unified by a common mathematical structure;

allow extension to new system classes;

are described by unified equations akin to those in thermodynamics, quantum mechanics, and field theory.

Formally, each distribution can be regarded as a thermodynamic potential in the corresponding statistical ensemble. Thus, the zeta function acts as a universal generator of physical measures, encompassing all fundamental distribution types and thermodynamic descriptions.

Let us also establish a comparison with Boltzmann entropy or Planck’s energy spectrum.

Figure 7.

Graph of . Jump-like features are visible.

Figure 7.

Graph of . Jump-like features are visible.

Comparison with Boltzmann Entropy

Boltzmann entropy is defined by the classical expression:

where

W is the number of microstates corresponding to a macrostate, and

is the Boltzmann constant.

The function

S based on the Riemann zeta function:

also includes a logarithmic term reflecting the entropic component. If we take

as analogous to the partition function

Z, then:

Thus, S can be interpreted as a generalized entropy, encompassing both an entropic contribution (via ) and an energetic one (via directly).

Comparison with Planck Distribution

The Planck distribution for electromagnetic radiation energy density is:

If we denote as analogous to frequency and as analogous to temperature T, the shape of the function at fixed reproduces the Planck distribution’s form by : - A characteristic peak emerges (maximum radiation); - A smooth decline on the right (high-frequency decay); - The peak shifts with changing , akin to Wien’s displacement law.

Conclusion

The function S based on the zeta function:

Thus, the zeta function becomes a unified source of thermodynamics, bridging energy distributions and informational characteristics of physical systems.

Based on its universality, it naturally and self-consistently integrates with the equations of motion, which we expressed in simplified form as:

Electromagnetic fields arise as a consequence of the self-consistency of four flows: positively charged particles (), negatively charged particles (), neutral particles (), and the total mass flow ().

Both of these classes are also self-consistent within the framework of the universality of the zeta function, which ensures the integrity of the description of the medium’s dynamics. These considerations about the zeta function and the emergence of self-consistent distributions can be applied to the equations of electrodynamics. Now we will add another fundamental law—the law of conservation of electric charge, which in differential form is expressed as follows:

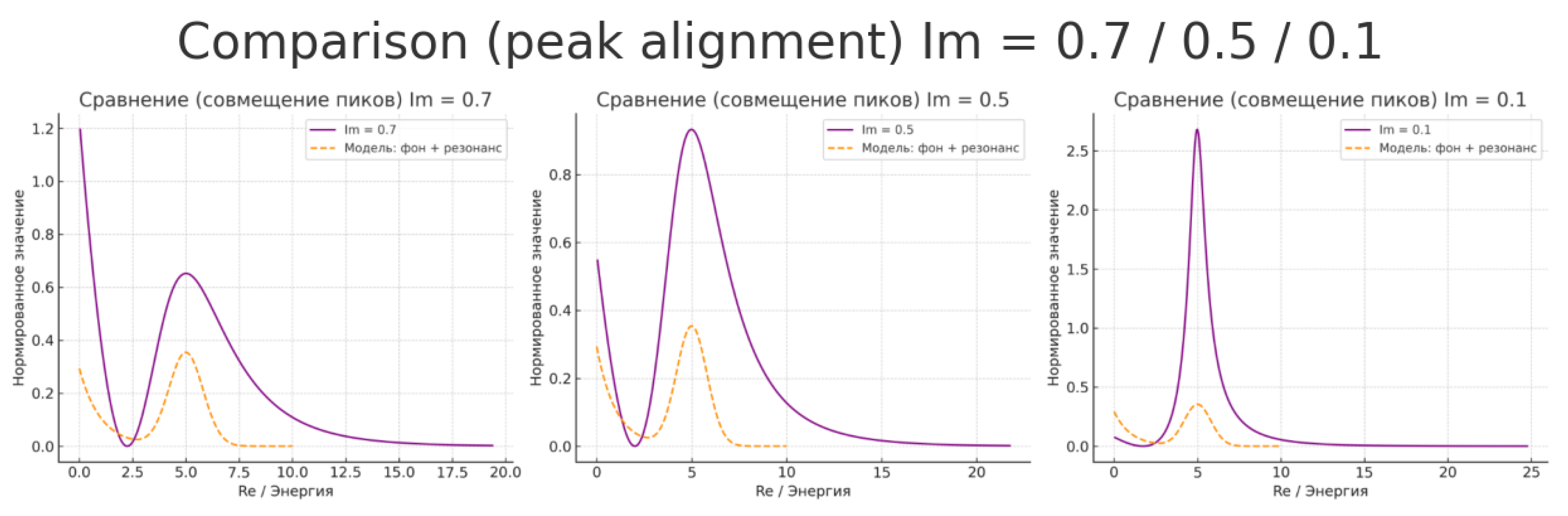

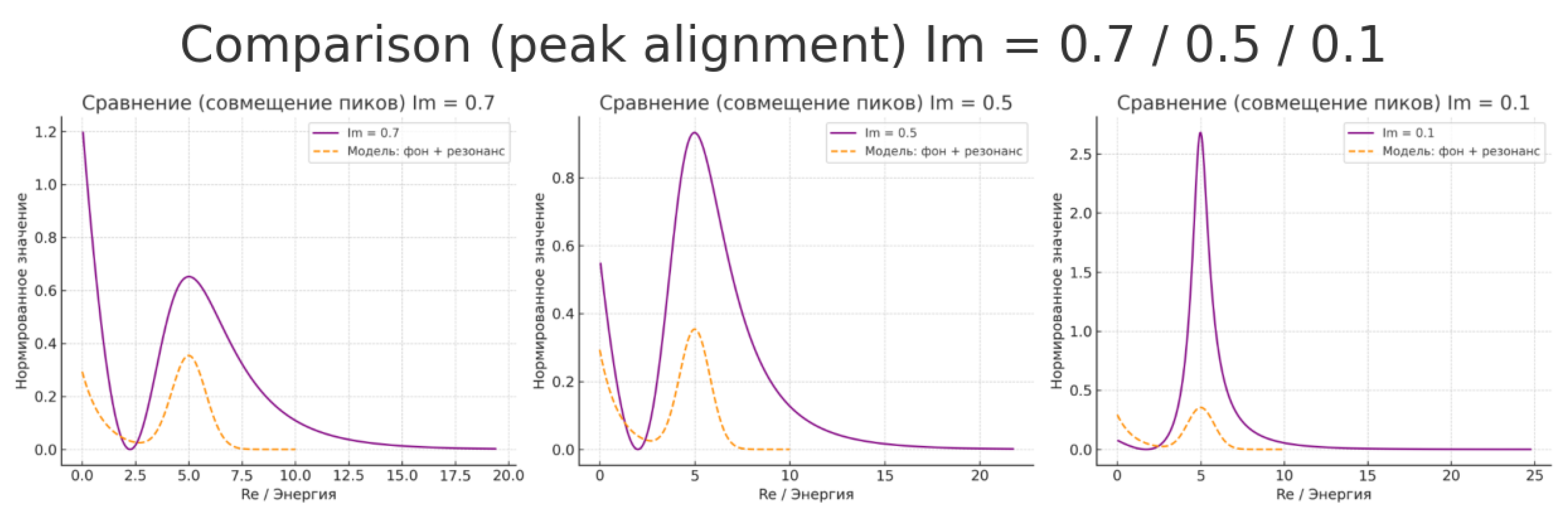

Explanation of Graphs Comparing Function S and Resonance Model

The graphs depict the behavior of the function:

at various imaginary part values Im, overlaid with a physical "background + resonance" model. This allows observing analogies between the zeta function’s mathematical behavior and energy distribution in turbulent or quantum systems.

Graph at Im = 0.7 (Left)

The graph of S shows a broad peak and smooth decline—corresponding to an excited system state. The peak can be interpreted as a resonance region with maximum energy absorption or redistribution. The right side of the curve represents a decay and stabilization phase, akin to thermodynamic equilibrium.

Graph at Im = 0.5 (Center)

A more pronounced dual behavior is evident: an excitation zone with a local maximum and a sharp decline. This corresponds to a quasi-stationary state where the system begins losing excitation and entering equilibrium. The "background + resonance" model clearly fits the peak, reflecting local energy excitation transitioning to equilibrium.

Graph at Im = 0.1 (Right)

The peak is sharp and high—resonance is sharply expressed, like a turbulent burst or phase transition. This can be interpreted as a moment of critical excitation—turbulence, peak instability, or a short-lived excited state. The rapid decline post-peak mirrors relaxation.

Interpretation

The imaginary part Im acts as a temperature or perturbation parameter: as it decreases, the system shifts from an equilibrium regime to one of pronounced resonance, similar to quantum or turbulent systems.

The behavior of the S-function resembles energy profiles in quantum physics (e.g., Breit–Wigner distributions, spectral functions) and energy bursts in turbulent flows.

Conclusion

The function S, based on the Riemann zeta function, naturally reproduces the structure of resonance curves characteristic of transitional states in physics. This strengthens the hypothesis of a connection between the zeta function’s analytic properties and universal energy distribution laws in nature, including:

Thus, we arrive at a unified concept in which solving the turbulence problems in nuclear fusion and the mathematical challenges related to AI analysis lie on the same plane. The problems faced by scientists and engineers in these fields intersect at a more fundamental level, where advancements in one area can contribute to progress in the other. The conceptual unity of these tasks opens up new prospects for the synthesis of knowledge and technology.

Turbulence in the plasma of nuclear fusion reactors, on one hand, represents one of the major challenges faced by researchers striving to improve plasma confinement and increase the efficiency of nuclear fusion. In existing models based on the Boltzmann equation, this issue faces a serious obstacle: the closure problem, which leads to a deadlock. The Boltzmann equation describes the evolution of the particle distribution function, but for a complete description of the system, higher-order moments are required, which leads to an infinite hierarchy. In the traditional approach, this hierarchy is artificially truncated, raising concerns about the internal consistency of models and their ability to accurately predict system behavior.

Figure 8.

Graph of . Jump-like features are visible.

Figure 8.

Graph of . Jump-like features are visible.

On the other hand, in the concept proposed by us, this closure problem is overcome through the use of self-consistent measures derived from the zeta function. These measures do not require the artificial truncation of the hierarchy because they naturally align with the equations of motion for electron, positron, and neutral gas density, as well as with the equations of momentum conservation. This avoids the deadlock that the traditional approach encounters and ensures internal consistency across all levels—from kinetic to hydrodynamic.

The use of the zeta function as a tool for describing and controlling plasma dynamics parallels approaches used in computational algorithms for artificial intelligence. The zeros of the zeta function, interpreted as markers of phase transitions, can serve as the foundation for constructing mathematical models that not only predict plasma dynamics but also guide the computation process in AI. This enables the joint solution of both nuclear fusion and AI challenges using a common theoretical framework.

Thus, the solution to turbulence problems and the mathematical challenges in AI can be linked through a common mathematical apparatus. We propose that solving these issues will eventually open up the possibility of creating "mega-brains"—super-powerful computing systems that can integrate data from various fields of knowledge and solve humanity’s grand challenges. These systems will leverage vast resources, including those related to nuclear fusion, enabling the development of AI capable of addressing tasks that require immense computational power.

These ideas provide the foundation for further research in nuclear fusion, turbulence theory, and artificial intelligence, and could serve as a starting point for the creation of a new generation of computing systems focused on solving the most complex problems of modern science and technology.

Previously, analyzing stock market dynamics, biophysical systems, or complex technological processes lacked consistent measures and tools for quantitatively assessing phase discontinuities. However, with advancements in our understanding of phase analysis and the emergence of consistent metrics, it is now possible not only to track but also to potentially manage critical transitions. This paves the way for more robust models—toward a state conditionally termed a "white swan society," characterized by reduced systemic uncertainty.

11.3. Conclusions

All the results and hypotheses outlined are built upon the fundamental theorems of Voronin’s universality, the Riemann Hypothesis, Durmagambetov’s constructive universality, and its reduction of differential equation studies to the zeta function. Additionally, they rely on Montgomery’s key results, confirmed by Odlyzko, and the potential use of quantum statistics tied to zeta function zeros. I hope the above forms a cohesive perception of AI developments for readers and provides a new impetus for advancing efficient AI.

One question remains: how does the initial motion—filling of the zeta function—arise, from which everything described follows? Naturally, the most significant point emerges: the heartbeat governs the brain, a crucial fact of launching universality and animating the zeta function, which then takes over as the most powerful quantum computer, recalculating everything. From where does the predetermination of all existence arise? As we see, it is encoded in prime numbers, through which the zeta function is defined, and through the zeta function, everything else is described. Hence, we might hypothesize that prime numbers are the angels of the Almighty, unchanging and strictly adhering to divine commandments, while humans are the processes described by these numbers, with original sin as the initiation of the zeta function into life.

References

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., Courville, A. (2016). Deep Learning. MIT Press.

- Montgomery, H. L. (1973). The pair correlation of zeros of the zeta function. Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics.

- Odlyzko A. On the distribution of spacings between zeros of the zeta function (engl.) // Mathematics of Computation[engl.] : journal. — Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, 1987. — Vol. 48, iss. 177. — P. 273—308.

- Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S., & Guestrin, C. (2016). "Why Should I Trust You?" Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining.

- Gaspard, P. (2005). Chaos, Scattering and Statistical Mechanics. Cambridge Nonlinear Science Series.

- Voronin, S. M. (1975). Theorem on the Universality of the Riemann Zeta-Function. Mathematics of the USSR-Izvestija.

- Bagchi, B. (1981). Statistical behaviour and universality properties of the Riemann zeta-function and other allied Dirichlet series. PhD thesis, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata.

- Berry, M. V., & Keating, J. P. (1999). The Riemann Zeros and Eigenvalue Asymptotics. SIAM Review.

- Ivic, A. (2003). The Riemann Zeta-Function: Theory and Applications. Dover Publications.

- Haake, F. (2001). Quantum Signatures of Chaos. Springer Series in Synergetics.

- Sierra, G., & Townsend, P. K. (2000). The Landau model and the Riemann zeros. Physics Letters B.

- Durmagambetov, A. A. (2023). A new functional relation for the Riemann zeta functions. Presented at TWMS Congress-2023.

- Durmagambetov, A. A. (2024). Theoretical Foundations for Creating Fast Algorithms Based on Constructive Methods of Universality. Preprints 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).