Submitted:

16 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

- Shared Pathophysiological Mechanisms: inflammation and oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction:

- Motor and Functional Decline: mobility and balance, sarcopenia, and muscle wasting.

- Risk of Malnutrition

- Cognitive Decline and Depression

3. Aged People Dysfunction: Parkinson's vs. Frailty: A Comparison of Aging-Related Conditions

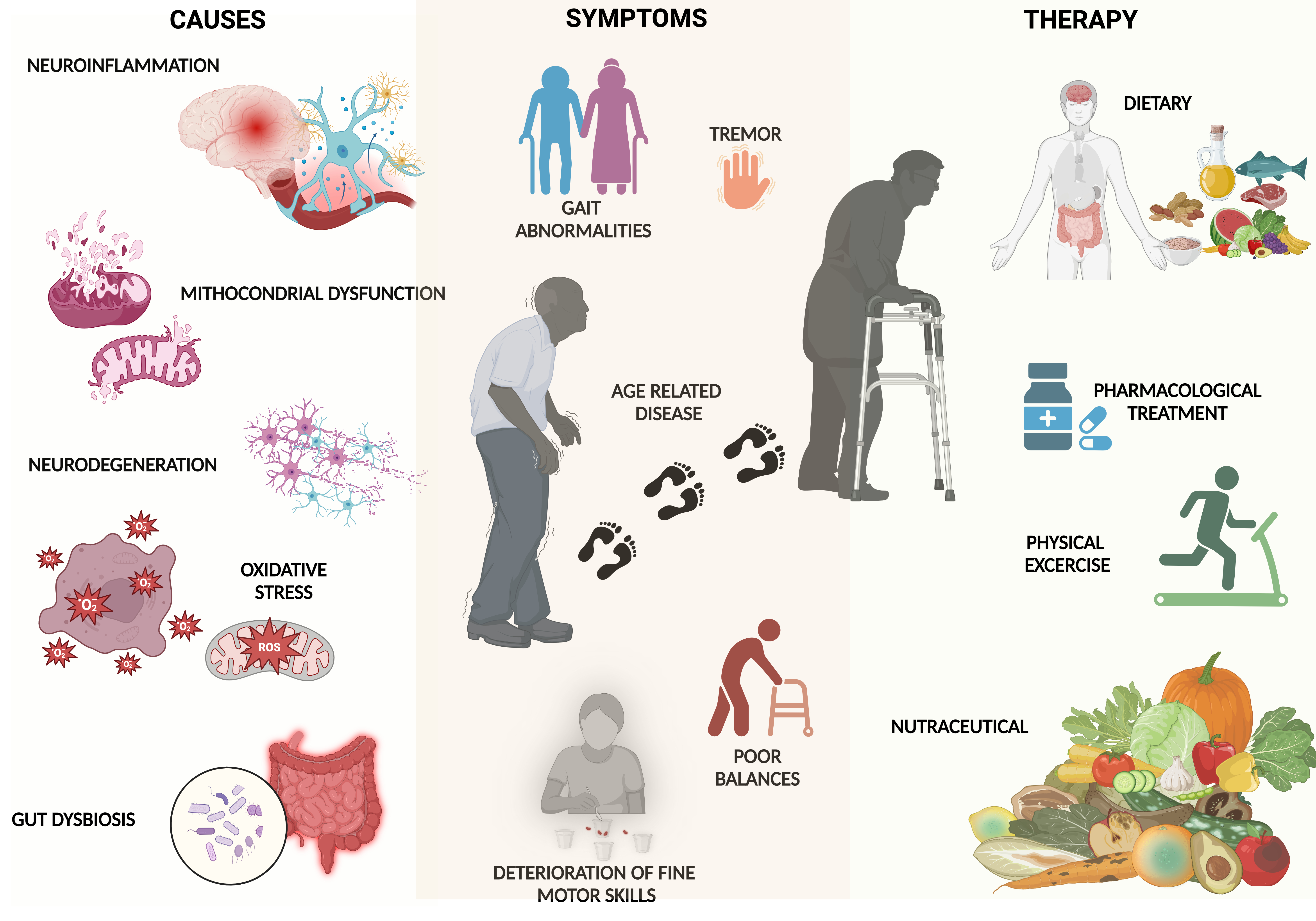

3.1. Parkinson’s Disease

3.1.1. Current Therapeutic Approaches

3.1.2. Limitations of Conventional Treatments

| Category | Treatment | Mechanism | Benefits | Limitations/ Side Effects |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Levodopa and Derivatives |

Converts to dopamine to alleviate motor symptoms | Effective for tremors and rigidity | Diminished effectiveness over time, dyskinesia, motor fluctuations | [69,70,71] | |

| Conventional Pharmacological Treatments |

MAO-B Inhibitors |

Delays breakdown of levodopa, extending benefits | Fewer dyskinesias, used in early-stage PD |

Less potent than levodopa, often used in combination with other therapies | [69,70,71,72,73,74] |

| COMT Inhibitors | Increases levodopa availability by reducing breakdown | Extends levodopa's effects | Dyskinesia, confusion, tolcapone risk of liver failure | [101] | |

|

Antidiabetic Agents |

May reduce neuroinflammation and oxidative stress |

Potential neuroprotective effects, motor and cognitive improvements |

Potential off-target effects; still under study | [78,79,80,81] | |

| Biguanides (Metformin) | Potential neuroprotective effects | Neuroprotective effects in PD | Risk of vitamin B12 deficiency, potential cognitive decline |

[84,85,86,111] | |

|

Non- Pharmacological Treatments |

Stem Cell Therapy |

Regenerates dopaminergic neurons |

Long-term motor benefits |

Risks of dyskinesia, ethical concerns, early-stage research | [87,88,89]. |

| Gene Therapy | Targets defective genes and neurotrophic factors | Promising disease-modifying potential | Gene distribution challenges, efficacy concerns in clinical application | [90,91] | |

|

|

Lesioning Procedures |

Targets specific brain areas to alleviate motor symptoms |

Effective for motor symptom relief |

Neurological side effects, reserved for medication-unresponsive patients |

[92]. |

| Surgical Treatments | DBS | Delivers electrical impulses to control motor symptoms | Improves motor function, reduces medication reliance | Risk of dyskinesia, cognitive impairment, requires careful management | [93,94] |

| FUS |

Non-invasive ultrasound to target brain tissue |

Promising alternative to traditional surgery |

Still under study, potential for tissue damage | [95] | |

| GKT | Uses gamma radiation to treat tremors | Minimally invasive, fewer long-term complications | Radiation-induced neurological changes possible | [96,97] |

3.2. Frailty

3.2.1. Current Therapeutic Approaches

3.2.2. Limitations of Conventional Treatments

| Category | Treatment | Mechanism | Benefits | Limitations/ Side Effects |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Testosterone |

Increases anabolic and metabolic activity, promoting muscle growth and improving physical capacity. | Modestly improves muscle function and overall physical capacity in frailty patients. | Requires large-scale studies for safety and efficacy validation. Risk of prostatic hyperplasia. | [72,73,74,134,135,136] |

|

|

GH | Anabolic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects in preclinical models. |

Shows promise in preclinical studies for muscle growth and function. | Has not demonstrated clinical effectiveness.Uncertain due to lack of clinical efficacy data. | [128] |

|

Ghrelin |

Stimulates appetite and enhances gastric motility. | Potential to improve muscle mass and nutritional status by stimulating appetite. | Clinical benefits are not fully validated. | [137] | |

| Hormone Therapy |

Insulin |

Promotes muscle protein synthesis by increasing amino acid delivery and blood flow to muscles. |

Enhances muscle protein synthesis and may prevent muscle wasting. |

Associated with poorer outcomes in heart failure patients with diabetes. Risk of adverse effects in patients with heart failure. | [78,79,80,138,139] |

| Thyroid Hormone | Critical metabolic regulator affecting skeletal muscle. | Linked to improved muscle metabolism and function. | Limited effectiveness in cases of overt and latent thyroid dysfunction. Potential to worsen muscle wasting in thyroid dysfunction cases. | [139] [69,70,71] |

|

|

|

Myostatin |

Blocks myostatin, a cytokine that regulates muscle growth, to promote muscle mass increase. |

Positive outcomes in improving muscle function and independence in elderly sarcopenic individuals. |

Limited therapeutic benefit in many clinical trials. Unknown due to limited clinical success. | [140,141] |

| GDF-15 | Neutralizes GDF-15, which is associated with reduced muscle mass and heightened inflammation, to restore muscle function. | Significantly increases muscle mass, boosts appetite, and improves physical function in experimental models. | Experimental, requires further validation in clinical settings. | [140,141,148] | |

| Exercise |

Resistance Training |

Involves mTORC1 activation, mitochondrial biogenesis, increased IGF-1, and enhanced insulin sensitivity, reducing oxidative stress and inflammation. |

Preserves and enhances muscle mass, strength, and function in frail individuals. |

Requires structured programs and close supervision, making adherence challenging.Risk of injury in frail patients if not supervised properly. |

[149,150] [149,150,151,152]. |

|

|

|||||

| Vitamin D | Regulates calcium flow and reduces inflammation, impacting muscle function. | May improve muscle mass and physical performance in older adults with deficiency. | Effectiveness limited by patient adherence and variability in dietary habits.Uncertain in patients with chronic kidney disease or heart failure. | [159] | |

|

Nutrition |

Protein |

Stimulates muscle protein synthesis and anabolism, particularly through essential amino acids like leucine. and inflammation. |

Helps maintain muscle structure and function, and improves muscle mass in frail elderly individuals |

Compliance issues due to variability in diet, ethnicity, and genetics. |

[149,150,163] [163,164] |

|

Omega-3 Fatty Acids |

Anti-inflammatory properties that support muscle health. |

May reduce inflammation and support muscle function in frailty. |

Challenges include low adherence and complex interactions with other nutrients | [149,150,155,166] |

4. Unveiling the Differences: Nutraceutical vs. Conventional Food

4.1. Categories of Nutraceuticals: A Comprehensive Overview

4.1.1. Traditional Nutraceuticals

4.1.2. Non-Traditional Nutraceuticals

5. Mechanisms of Nutraceutical Action in Frailty and Parkinson’s Disease

Anti-Inflammatory Activity

5.2.2. Anti-Oxidant Activity

5.3. Promoting Healthy Aging

6. Emerging Nutraceuticals and Future Directions

7. Challenges and Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ismail, Z.; Ahmad, W.I.W.; Hamjah, S.H.; Astina, I.K. The impact of population ageing: A review. Iran. J. Public Health 2021, 50, 2451–2460. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Morsiani, C.; Conte, M.; Santoro, A.; Grignolio, A.; Monti, D.; Capri, M.; Salvioli, S. The Continuum of Aging and Age-Related Diseases: Common Mechanisms but Different Rates. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018, 5, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, M.; Xenodochidis, C.; Krasteva, N. Old age as a risk factor for liver diseases: Modern therapeutic approaches. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 184, 112334. [CrossRef]

- Fajemiroye, J.O.; da Cunha, L.C.; Saavedra-Rodríguez, R.; Rodrigues, K.L.; Naves, L.M.; Mourão, A.A.; da Silva, E.F.; Williams, N.E.E.; Martins, J.L.R.; Sousa, R.B.; Rebelo, A.C.S.; Reis, A.A. da S.; Santos, R. da S.; Ferreira-Neto, M.L.; Pedrino, G.R. Aging-Induced Biological Changes and Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 7156435. [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Li, Y.; Sheng, C.-S.; Liu, L.; Hou, T.; Xia, N.; Sun, S.; Miao, Y.; Pang, Y.; Gu, K.; Lu, X.; Wen, C.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, M.; Harris, K.; Bloomgarden, Z.T.; Tian, J.; Shi, Y. Association between age at diabetes onset or diabetes duration and subsequent risk of pancreatic cancer: Results from a longitudinal cohort and mendelian randomization study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2023, 30, 100596. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Park, J.H.; Lu, H.-C. Axonal energy metabolism, and the effects in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 49. [CrossRef]

- Salvioli, S.; Basile, M.S.; Bencivenga, L.; Carrino, S.; Conte, M.; Damanti, S.; De Lorenzo, R.; Fiorenzato, E.; Gialluisi, A.; Ingannato, A.; Antonini, A.; Baldini, N.; Capri, M.; Cenci, S.; Iacoviello, L.; Nacmias, B.; Olivieri, F.; Rengo, G.; Querini, P.R.; Lattanzio, F. Biomarkers of aging in frailty and age-associated disorders: State of the art and future perspective. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 91, 102044. [CrossRef]

- Cristina-Pereira, R.; Trevisan, K.; Vasconcelos-da-Silva, E.; Figueredo-da-Silva, S.; F. Magri, M.P. de; Brunelli, L.F.; Aversi-Ferreira, T.A. Association between Age Gain, Parkinsonism and Pesticides: A Public Health Problem? Int. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. J. 2023, 19, 44–73. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Lv, Y.; Rong, S.; Sun, T.; Chen, L. Physical frailty, genetic predisposition, and incident parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 455–461. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, P.A.; Wilkinson, J.R. Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders. In Geriatric medicine: A person centered evidence based approach; Wasserman, M. R., Bakerjian, D., Linnebur, S., Brangman, S., Cesari, M., Rosen, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; pp. 1073–1096 ISBN 978-3-030-74719-0.

- Kumar, S.; Goyal, L.; Singh, S. Tremor and Rigidity in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: Emphasis on Epidemiology, Pathophysiology and Contributing Factors. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2022, 21, 596–609. [CrossRef]

- Montanari, M.; Imbriani, P.; Bonsi, P.; Martella, G.; Peppe, A. Beyond the Microbiota: Understanding the Role of the Enteric Nervous System in Parkinson’s Disease from Mice to Human. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, A.; Kamble, N.; Bhattacharya, A.; Holla, V.; Yadav, R.; Pal, P.K. Impact of Non-Motor Symptoms on Quality of Life in Patients with Early-Onset Parkinson’s Disease. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Saini, N.; Singh, N.; Kaur, N.; Garg, S.; Kaur, M.; Kumar, A.; Verma, M.; Singh, K.; Sohal, H.S. Motor and non-motor symptoms, drugs, and their mode of action in Parkinson’s disease (PD): a review. Med. Chem. Res. 2024, 33, 580–599. [CrossRef]

- Grotewold, N.; Albin, R.L. Update: Descriptive epidemiology of Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2024, 120, 106000. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, E.; Jang, I.Y. Frailty and comprehensive geriatric assessment. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e16. [CrossRef]

- Proietti, M.; Cesari, M. Frailty: what is it? Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1216, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.; Herpich, C.; Müller-Werdan, U. Role of phase angle in older adults with focus on the geriatric syndromes sarcopenia and frailty. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2023, 24, 429–437. [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Gaunt, D.M.; Whone, A.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Henderson, E.J. The association between frailty and parkinson’s disease in the respond trial. Can. Geriatr. J. 2021, 24, 22–25. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, K.; Singh, S.; Singh, V.; Bajpai, M. Nutraceuticals a food for thought in the treatment of parkinson’s disease. CNF 2023, 19, 961–977. [CrossRef]

- Barua, C.C.; Sharma, D.; Devi, Ph.V.; Islam, J.; Bora, B.; Duarah, R. Nutraceuticals and bioactive components of herbal extract in the treatment and prevention of neurological disorders. In Treatments, nutraceuticals, supplements, and herbal medicine in neurological disorders; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 577–600 ISBN 9780323900522.

- Gómez-Gómez, M.E.; Zapico, S.C. Frailty, cognitive decline, neurodegenerative diseases and nutrition interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Ebina, J.; Ebihara, S.; Kano, O. Similarities, differences and overlaps between frailty and Parkinson’s disease. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2022, 22, 259–270. [CrossRef]

- Kalra, E.K. Nutraceutical--definition and introduction. AAPS PharmSci 2003, 5, E25. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Gupta, H.; Anamika; Kumar, R. Therapeutic approaches of nutraceuticals in neurological disorders: A review. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 3, 261–281. [CrossRef]

- Jan, B.; Choudhary, B.; Malik, Z.; Dar, M.I. A descriptive review on exploiting the therapeutic significance of essential oils as a potential nutraceutical and food preservative. Food Safety and Health 2024, 2, 238–264. [CrossRef]

- do Prado, D.Z.; Capoville, B.L.; Delgado, C.H.O.; Heliodoro, J.C.A.; Pivetta, M.R.; Pereira, M.S.; Zanutto, M.R.; Novelli, P.K.; Francisco, V.C.B.; Fleuri, L.F. Nutraceutical food: composition, biosynthesis, therapeutic properties, and applications. In Alternative and replacement foods; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 95–140 ISBN 9780128114469.

- Gimeno-Mallench, L.; Sanchez-Morate, E.; Parejo-Pedrajas, S.; Mas-Bargues, C.; Inglés, M.; Sanz-Ros, J.; Román-Domínguez, A.; Olaso, G.; Stromsnes, K.; Gambini, J. The Relationship between Diet and Frailty in Aging. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2020, 20, 1373–1382. [CrossRef]

- Jacquier, E.F.; Kassis, A.; Marcu, D.; Contractor, N.; Hong, J.; Hu, C.; Kuehn, M.; Lenderink, C.; Rajgopal, A. Phytonutrients in the promotion of healthspan: a new perspective. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1409339. [CrossRef]

- Kassis, A.; Fichot, M.-C.; Horcajada, M.-N.; Horstman, A.M.H.; Duncan, P.; Bergonzelli, G.; Preitner, N.; Zimmermann, D.; Bosco, N.; Vidal, K.; Donato-Capel, L. Nutritional and lifestyle management of the aging journey: A narrative review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1087505. [CrossRef]

- Noto, S. Perspectives on aging and quality of life. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Keskinidou, C.; Vassiliou, A.G.; Dimopoulou, I.; Kotanidou, A.; Orfanos, S.E. Mechanistic understanding of lung inflammation: recent advances and emerging techniques. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 3501–3546. [CrossRef]

- Schuliga, M.; Read, J.; Knight, D.A. Ageing mechanisms that contribute to tissue remodeling in lung disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 70, 101405. [CrossRef]

- Sabbatinelli, J.; Prattichizzo, F.; Olivieri, F.; Procopio, A.D.; Rippo, M.R.; Giuliani, A. Where metabolism meets senescence: focus on endothelial cells. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1523. [CrossRef]

- Coryell, P.R.; Diekman, B.O.; Loeser, R.F. Mechanisms and therapeutic implications of cellular senescence in osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2021, 17, 47–57. [CrossRef]

- Rezuș, E.; Cardoneanu, A.; Burlui, A.; Luca, A.; Codreanu, C.; Tamba, B.I.; Stanciu, G.-D.; Dima, N.; Bădescu, C.; Rezuș, C. The link between inflammaging and degenerative joint diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Singler, K.; Sieber, C.C. Age-related changes in the elderly. In Musculoskeletal trauma in the elderly; Court-Brown, C. M., McQueen, M. M., Swiontkowski, M. F., Ring, D., Friedman, S. M., Duckworth, A. D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, 2016., 2016; pp. 21–30 ISBN 9781315381954.

- Dharmarajan, T.S. Physiology of Aging. In Geriatric Gastroenterology; Pitchumoni, C. S., Dharmarajan, T. S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 101–153 ISBN 978-3-030-30191-0.

- Roger, L.; Tomas, F.; Gire, V. Mechanisms and regulation of cellular senescence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Sacco, A.; Belloni, L.; Latella, L. From development to aging: the path to cellular senescence. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 34, 294–307. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fang, J.; Yue, H.; Ma, S.; Guan, F. Aging and age-related diseases: from mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Biogerontology 2021, 22, 165–187. [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yang, H.; Zheng, K. Immune Remodeling during Aging and the Clinical Significance of Immunonutrition in Healthy Aging. Aging Dis. 2024, 15, 1588–1601. [CrossRef]

- Coperchini, F.; Greco, A.; Teliti, M.; Croce, L.; Chytiris, S.; Magri, F.; Gaetano, C.; Rotondi, M. Inflamm-ageing: How cytokines and nutrition shape the trajectory of ageing. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Jackson, T.; Sapey, E.; Lord, J.M. Frailty and sarcopenia: The potential role of an aged immune system. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 36, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Brito, D.V.C.; Esteves, F.; Rajado, A.T.; Silva, N.; ALFA score Consortium; Araújo, I.; Bragança, J.; Castelo-Branco, P.; Nóbrega, C. Assessing cognitive decline in the aging brain: lessons from rodent and human studies. npj Aging 2023, 9, 23. [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J.F.; Mather, M.; Koenig, J. Stress and aging: A neurovisceral integration perspective. Psychophysiology 2021, 58, e13804. [CrossRef]

- Kemoun, P.; Ader, I.; Planat-Benard, V.; Dray, C.; Fazilleau, N.; Monsarrat, P.; Cousin, B.; Paupert, J.; Ousset, M.; Lorsignol, A.; Raymond-Letron, I.; Vellas, B.; Valet, P.; Kirkwood, T.; Beard, J.; Pénicaud, L.; Casteilla, L. A gerophysiology perspective on healthy ageing. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 73, 101537. [CrossRef]

- Kouli, A.; Torsney, K.M.; Kuan, W.-L. Parkinson’s disease: etiology, neuropathology, and pathogenesis. In Parkinson’s disease: pathogenesis and clinical aspects; Stoker, T. B., Greenland, J. C., Eds.; Codon Publications: Brisbane (AU), 2018 ISBN 9780994438164.

- Armstrong, M.J.; Okun, M.S. Diagnosis and treatment of parkinson disease: A review. JAMA 2020, 323, 548–560. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, E.J.; Zhang, W.; Lu, Y.; Liu, R.; Huang, X.; Ciesielski-Jones, A.J.; Justice, M.A.; Cousins, D.S.; Peddada, S. Meta-analyses on prevalence of selected Parkinson’s nonmotor symptoms before and after diagnosis. Transl. Neurodegener. 2015, 4, 1. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.; Goetz, C.G.; Mestre, T.A.; Sampaio, C.; Adler, C.H.; Berg, D.; Bloem, B.R.; Burn, D.J.; Fitts, M.S.; Gasser, T.; Klein, C.; de Tijssen, M.A.J.; Lang, A.E.; Lim, S.-Y.; Litvan, I.; Meissner, W.G.; Mollenhauer, B.; Okubadejo, N.; Okun, M.S.; Postuma, R.B.; Trenkwalder, C. A statement of the MDS on biological definition, staging, and classification of parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2024, 39, 259–266. [CrossRef]

- Virameteekul, S.; Revesz, T.; Jaunmuktane, Z.; Warner, T.T.; De Pablo-Fernández, E. Clinical diagnostic accuracy of parkinson’s disease: where do we stand? Mov. Disord. 2023, 38, 558–566. [CrossRef]

- Kadiyala, P.K. Mnemonics for diagnostic criteria of DSM V mental disorders: a scoping review. Gen. Psych. 2020, 33, e100109. [CrossRef]

- Qutubuddin, A.A.; Chandan, P.; Carne, W. Degenerative movement disorders of the central nervous system. In Braddom’s physical medicine and rehabilitation; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 972–982 ISBN 9780323625395.

- Stocchi, F.; Torti, M. Constipation in parkinson’s disease. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2017, 134, 811–826. [CrossRef]

- Ramjit, A.L.; Sedig, L.; Leibner, J.; Wu, S.S.; Dai, Y.; Okun, M.S.; Rodriguez, R.L.; Malaty, I.A.; Fernandez, H.H. The relationship between anosmia, constipation, and orthostasis and Parkinson’s disease duration: results of a pilot study. Int. J. Neurosci. 2010, 120, 67–70. [CrossRef]

- Pessoa Rocha, N.; Reis, H.J.; Vanden Berghe, P.; Cirillo, C. Depression and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: a role for inflammation and immunomodulation? Neuroimmunomodulation 2014, 21, 88–94. [CrossRef]

- Ongari, G.; Ghezzi, C.; Di Martino, D.; Pisani, A.; Terzaghi, M.; Avenali, M.; Valente, E.M.; Cerri, S.; Blandini, F. Impaired Mitochondrial Respiration in REM-Sleep Behavior Disorder: A Biomarker of Parkinson’s Disease? Mov. Disord. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.Y.-Y.; Ho, P.W.-L.; Liu, H.-F.; Leung, C.-T.; Li, L.; Chang, E.E.S.; Ramsden, D.B.; Ho, S.-L. The interplay of aging, genetics and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2019, 8, 23. [CrossRef]

- Kolicheski, A.; Turcano, P.; Tamvaka, N.; McLean, P.J.; Springer, W.; Savica, R.; Ross, O.A. Early-Onset Parkinson’s Disease: Creating the Right Environment for a Genetic Disorder. J Parkinsons Dis 2022, 12, 2353–2367. [CrossRef]

- Jin, W. Novel Insights into PARK7 (DJ-1), a Potential Anti-Cancer Therapeutic Target, and Implications for Cancer Progression. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Ortega, R.A.; Wang, C.; Raymond, D.; Bryant, N.; Scherzer, C.R.; Thaler, A.; Alcalay, R.N.; West, A.B.; Mirelman, A.; Kuras, Y.; Marder, K.S.; Giladi, N.; Ozelius, L.J.; Bressman, S.B.; Saunders-Pullman, R. Association of dual LRRK2 G2019S and GBA variations with parkinson disease progression. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e215845. [CrossRef]

- Pyatha, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, D.; Kim, K. Association between Heavy Metal Exposure and Parkinson’s Disease: A Review of the Mechanisms Related to Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, V.; Santoro, A.; Monti, D.; Crupi, R.; Di Paola, R.; Latteri, S.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Zappia, M.; Giordano, J.; Calabrese, E.J.; Franceschi, C. Aging and Parkinson’s Disease: Inflammaging, neuroinflammation and biological remodeling as key factors in pathogenesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 115, 80–91. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-W.; Chen, C.-M.; Chang, K.-H. Biomarker of neuroinflammation in parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Tassone, A.; Meringolo, M.; Ponterio, G.; Bonsi, P.; Schirinzi, T.; Martella, G. Mitochondrial bioenergy in neurodegenerative disease: huntington and parkinson. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Muleiro Alvarez, M.; Cano-Herrera, G.; Osorio Martínez, M.F.; Vega Gonzales-Portillo, J.; Monroy, G.R.; Murguiondo Pérez, R.; Torres-Ríos, J.A.; van Tienhoven, X.A.; Garibaldi Bernot, E.M.; Esparza Salazar, F.; Ibarra, A. A comprehensive approach to parkinson’s disease: addressing its molecular, clinical, and therapeutic aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Elsworth, J.D. Parkinson’s disease treatment: past, present, and future. J. Neural Transm. 2020, 127, 785–791. [CrossRef]

- Bezard, E. Experimental reappraisal of continuous dopaminergic stimulation against L-dopa-induced dyskinesia. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 1021–1022. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.K.; Kwatra, M.; Wang, J.; Ko, H.S. Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesia in Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Emerging Treatment Strategies. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Picillo, M.; Phokaewvarangkul, O.; Poon, Y.-Y.; McIntyre, C.C.; Beylergil, S.B.; Munhoz, R.P.; Kalia, S.K.; Hodaie, M.; Lozano, A.M.; Fasano, A. Levodopa Versus Dopamine Agonist after Subthalamic Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2021, 36, 672–680. [CrossRef]

- Regensburger, M.; Ip, C.W.; Kohl, Z.; Schrader, C.; Urban, P.P.; Kassubek, J.; Jost, W.H. Clinical benefit of MAO-B and COMT inhibition in Parkinson’s disease: practical considerations. J. Neural Transm. 2023, 130, 847–861. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, X.; Chen, F.; Wen, S.; Zhou, C. Dopamine agonists versus levodopa monotherapy in early Parkinson’s disease for the potential risks of motor complications: A network meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 954, 175884. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.-Y.; Jenner, P.; Chen, S.-D. Monoamine Oxidase-B Inhibitors for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease: Past, Present, and Future. J Parkinsons Dis 2022, 12, 477–493. [CrossRef]

- Finberg, J.P.M. Inhibitors of MAO-B and COMT: their effects on brain dopamine levels and uses in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2019, 126, 433–448. [CrossRef]

- Rascol, O.; Fabbri, M.; Poewe, W. Amantadine in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 1048–1056. [CrossRef]

- Bohnen, N.I.; Yarnall, A.J.; Weil, R.S.; Moro, E.; Moehle, M.S.; Borghammer, P.; Bedard, M.-A.; Albin, R.L. Cholinergic system changes in Parkinson’s disease: emerging therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 381–392. [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Li, H.; Yan, H.; Zhang, P.; Chang, L.; Li, T. Risk of Parkinson Disease in Diabetes Mellitus: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Cohort Studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95, e3549. [CrossRef]

- Cheong, J.L.Y.; de Pablo-Fernandez, E.; Foltynie, T.; Noyce, A.J. The association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2020, 10, 775–789. [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.-T.; Chen, K.-Y.; Wang, W.; Chiu, J.-Y.; Wu, D.; Chao, T.-Y.; Hu, C.-J.; Chau, K.-Y.D.; Bamodu, O.A. Insulin Resistance Promotes Parkinson’s Disease through Aberrant Expression of α-Synuclein, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Deregulation of the Polo-Like Kinase 2 Signaling. Cells 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Nowell, J.; Blunt, E.; Gupta, D.; Edison, P. Antidiabetic agents as a novel treatment for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 89, 101979. [CrossRef]

- Novak, P.; Pimentel Maldonado, D.A.; Novak, V. Safety and preliminary efficacy of intranasal insulin for cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease and multiple system atrophy: A double-blinded placebo-controlled pilot study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214364. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Xie, A. Intranasal insulin ameliorates cognitive impairment in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease through Akt/GSK3β signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2020, 259, 118159. [CrossRef]

- Ping, F.; Jiang, N.; Li, Y. Association between metformin and neurodegenerative diseases of observational studies: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- He, L. Metformin and systemic metabolism. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 41, 868–881. [CrossRef]

- Paudel, Y.N.; Angelopoulou, E.; Piperi, C.; Shaikh, M.F.; Othman, I. Emerging neuroprotective effect of metformin in Parkinson’s disease: A molecular crosstalk. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 152, 104593. [CrossRef]

- Studer, L. Strategies for bringing stem cell-derived dopamine neurons to the clinic-The NYSTEM trial. Prog. Brain Res. 2017, 230, 191–212. [CrossRef]

- Titova, N.; Chaudhuri, K.R. Personalized medicine in Parkinson’s disease: Time to be precise. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 1147–1154. [CrossRef]

- Stoddard-Bennett, T.; Reijo Pera, R. Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease through Personalized Medicine and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cells 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Kia, D.A.; Zhang, D.; Guelfi, S.; Manzoni, C.; Hubbard, L.; Reynolds, R.H.; Botía, J.; Ryten, M.; Ferrari, R.; Lewis, P.A.; Williams, N.; Trabzuni, D.; Hardy, J.; Wood, N.W.; United Kingdom Brain Expression Consortium (UKBEC) and the International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics Consortium (IPDGC) Identification of Candidate Parkinson Disease Genes by Integrating Genome-Wide Association Study, Expression, and Epigenetic Data Sets. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 464–472. [CrossRef]

- Nutt, J.G.; Curtze, C.; Hiller, A.; Anderson, S.; Larson, P.S.; Van Laar, A.D.; Richardson, R.M.; Thompson, M.E.; Sedkov, A.; Leinonen, M.; Ravina, B.; Bankiewicz, K.S.; Christine, C.W. Aromatic L-Amino Acid Decarboxylase Gene Therapy Enhances Levodopa Response in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 851–858. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, C.S.; Tam, J.; Lozano, A.M. The changing landscape of surgery for Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 36–47. [CrossRef]

- Malek, N. Deep brain stimulation in parkinson’s disease. Neurol. India 2019, 67, 968–978. [CrossRef]

- Krauss, J.K.; Lipsman, N.; Aziz, T.; Boutet, A.; Brown, P.; Chang, J.W.; Davidson, B.; Grill, W.M.; Hariz, M.I.; Horn, A.; Schulder, M.; Mammis, A.; Tass, P.A.; Volkmann, J.; Lozano, A.M. Technology of deep brain stimulation: current status and future directions. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 75–87. [CrossRef]

- Phenix, C.P.; Togtema, M.; Pichardo, S.; Zehbe, I.; Curiel, L. High intensity focused ultrasound technology, its scope and applications in therapy and drug delivery. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 17, 136–153. [CrossRef]

- Young, R.F. Gamma Knife Radiosurgery as an Alternative Form of Therapy for Movement Disorders | JAMA Neurology | JAMA Network. Archives of Neurology 2002.

- Pérez-Sánchez, J.R.; Martínez-Álvarez, R.; Martínez Moreno, N.E.; Torres Diaz, C.; Rey, G.; Pareés, I.; Del Barrio A, A.; Álvarez-Linera, J.; Kurtis, M.M. Gamma Knife® stereotactic radiosurgery as a treatment for essential and parkinsonian tremor: long-term experience. Neurologia (Engl Ed) 2023, 38, 188–196. [CrossRef]

- Wamelen, D.J.V.; Rukavina, K.; Podlewska, A.M.; Chaudhuri, K.R. Advances in the Pharmacological and Non-pharmacological Management of Non-motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease: An Update Since 2017. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 1786–1805. [CrossRef]

- di Biase, L.; Pecoraro, P.M.; Carbone, S.P.; Caminiti, M.L.; Di Lazzaro, V. Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesias in Parkinson’s Disease: An Overview on Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, Therapy Management Strategies and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Lees, A.; Tolosa, E.; Stocchi, F.; Ferreira, J.J.; Rascol, O.; Antonini, A.; Poewe, W. Optimizing levodopa therapy, when and how? Perspectives on the importance of delivery and the potential for an early combination approach. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2023, 23, 15–24. [CrossRef]

- Cabreira, V.; Soares-da-Silva, P.; Massano, J. Contemporary options for the management of motor complications in parkinson’s disease: updated clinical review. Drugs 2019, 79, 593–608. [CrossRef]

- Haider, R. Pharmacologic management of parkinsonism and other movement disorders. JNNS 2024, 14, 01–13. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ting, J.P.; Al-Azzam, S.; Ding, Y.; Afshar, S. Therapeutic advances in diabetes, autoimmune, and neurological diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.J.; Scott, E.; Fulcher, J.; Kilov, G.; Januszewski, A.S. Management of diabetes mellitus. In Comprehensive cardiovascular medicine in the primary care setting; Toth, P. P., Cannon, C. P., Eds.; Contemporary Cardiology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 113–177 ISBN 978-3-319-97621-1.

- Gadó, K.; Tabák, G.Á.; Vingender, I.; Domján, G.; Dörnyei, G. Treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the elderly - Special considerations. Physiol. Int. 2024, 111, 143–164. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Tang, L.; Tang, X. Current developments in cell replacement therapy for parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience 2021, 463, 370–382. [CrossRef]

- Kohn, D.B.; Chen, Y.Y.; Spencer, M.J. Successes and challenges in clinical gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2023, 30, 738–746. [CrossRef]

- Sarwal, A. Neurologic complications in the postoperative neurosurgery patient. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2021, 27, 1382–1404. [CrossRef]

- Machado, F.A.; Reppold, C.T. The effect of deep brain stimulation on motor and cognitive symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: A literature review. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2015, 9, 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Nunez, A.E.; Justich, M.B.; Okun, M.S.; Fasano, A. Emerging therapies for neuromodulation in Parkinson’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 2023, e00310. [CrossRef]

- Infante, M.; Leoni, M.; Caprio, M.; Fabbri, A. Long-term metformin therapy and vitamin B12 deficiency: An association to bear in mind. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 916–931. [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, U.; Bashyal, B.; Shrestha, A.; Koirala, B.; Sharma, S.K. Frailty and chronic diseases: A bi-directional relationship. Aging Med (Milton) 2024, 7, 510–515. [CrossRef]

- Lameirinhas, J.; Gorostiaga, A.; Etxeberria, I. Definition and assessment of psychological frailty in older adults: A scoping review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 100, 102442. [CrossRef]

- Dent, E.; Kowal, P.; Hoogendijk, E.O. Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: A review. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 3–10. [CrossRef]

- Benjumea, A. Frailty Phenotype. In Frailty and kidney disease: A practical guide to clinical management; Musso, C. G., Jauregui, J. R., Macías-Núñez, J. F., Covic, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 1–6 ISBN 978-3-030-53528-5.

- Almeida Barros, A.A.; Lucchetti, G.; Guilhermino Alves, E.B.; de Carvalho Souza, S.Q.; Rocha, R.P.R.; Almeida, S.M.; Silva Ezequiel, O. da; Granero Lucchetti, A.L. Factors associated with frailty, pre-frailty, and each of Fried’s criteria of frailty among older adult outpatients. Geriatr. Nurs. 2024, 60, 85–91. [CrossRef]

- Marengoni, A.; Zucchelli, A.; Vetrano, D.L.; Aloisi, G.; Brandi, V.; Ciutan, M.; Panait, C.L.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G.; Palmer, K. Heart failure, frailty, and pre-frailty: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 316, 161–171. [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, J.; Long, S.; Carter, B.; Bach, S.; McCarthy, K.; Clegg, A. The prevalence of frailty and its association with clinical outcomes in general surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 793–800. [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Xie, W.; Fu, X.; Lu, W.; Jin, H.; Lai, J.; Zhang, A.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiao, W. Inflammation and sarcopenia: A focus on circulating inflammatory cytokines. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 154, 111544. [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Pérez, D.; Sánchez-Flores, M.; Proietti, S.; Bonassi, S.; Costa, S.; Teixeira, J.P.; Fernández-Tajes, J.; Pásaro, E.; Laffon, B.; Valdiglesias, V. Association of inflammatory mediators with frailty status in older adults: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Geroscience 2020, 42, 1451–1473. [CrossRef]

- Soysal, P.; Stubbs, B.; Lucato, P.; Luchini, C.; Solmi, M.; Peluso, R.; Sergi, G.; Isik, A.T.; Manzato, E.; Maggi, S.; Maggio, M.; Prina, A.M.; Cosco, T.D.; Wu, Y.-T.; Veronese, N. Inflammation and frailty in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 31, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Greco, E.A.; Pietschmann, P.; Migliaccio, S. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia increase frailty syndrome in the elderly. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10, 255. [CrossRef]

- El Assar, M.; Angulo, J.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Frailty as a phenotypic manifestation of underlying oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 149, 72–77. [CrossRef]

- Perazza, L.R.; Brown-Borg, H.M.; Thompson, L.V. Physiological systems in promoting frailty. Compr. Physiol. 2022, 12, 3575–3620. [CrossRef]

- Angulo, J.; El Assar, M.; Álvarez-Bustos, A.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Physical activity and exercise: Strategies to manage frailty. Redox Biol. 2020, 35, 101513. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 538–548. [CrossRef]

- Eidam, A.; Durga, J.; Bauer, J.M.; Zimmermann, S.; Vey, J.A.; Rapp, K.; Schwenk, M.; Cesari, M.; Benzinger, P. Interventions to prevent the onset of frailty in adults aged 60 and older (PRAE-Frail): a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Najm, A.; Niculescu, A.-G.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Beuran, M. Emerging therapeutic strategies in sarcopenia: an updated review on pathogenesis and treatment advances. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Oguz, S.H.; Yildiz, B.O. The endocrinology of aging. In Beauty, aging, and antiaging; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 303–318 ISBN 9780323988049.

- Chertman, L.S.; Merriam, G.R.; Kargi, A.Y. Growth Hormone in Aging. In Endotext; De Groot, L. J., Beck-Peccoz, P., Chrousos, G., Dungan, K., Grossman, A., Hershman, J. M., Koch, C., McLachlan, R., New, M., Rebar, R., Singer, F., Vinik, A., Weickert, M. O., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth (MA), 2000.

- Liu, H.; Bravata, D.M.; Olkin, I.; Nayak, S.; Roberts, B.; Garber, A.M.; Hoffman, A.R. Systematic review: the safety and efficacy of growth hormone in the healthy elderly. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 104–115. [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.E.; Malmstrom, T.K. Frailty, sarcopenia, and hormones. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2013, 42, 391–405. [CrossRef]

- Bhasin, S. The Brave New World of Function-Promoting Anabolic Therapies: Testosterone and Frailty. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2010, 95, 509–511. [CrossRef]

- Emmelot-Vonk, M.H.; Verhaar, H.J.J.; Nakhai Pour, H.R.; Aleman, A.; Lock, T.M.T.W.; Bosch, J.L.H.R.; Grobbee, D.E.; van der Schouw, Y.T. Effect of testosterone supplementation on functional mobility, cognition, and other parameters in older men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008, 299, 39–52. [CrossRef]

- Srinivas-Shankar, U.; Roberts, S.A.; Connolly, M.J.; O’Connell, M.D.L.; Adams, J.E.; Oldham, J.A.; Wu, F.C.W. Effects of testosterone on muscle strength, physical function, body composition, and quality of life in intermediate-frail and frail elderly men: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 639–650. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, D.T.; Adler, K.A.; Weinstein, C.S.; Weiss, J.P. Managing nocturia in frail older adults. Drugs Aging 2021, 38, 95–109. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Tsai, C.-Y. Ghrelin and motilin in the gastrointestinal system. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18, 4755–4765. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, W.K.; Phillips, B.E.; Williams, J.P.; Rankin, D.; Lund, J.N.; Wilkinson, D.J.; Smith, K.; Atherton, P.J. The impact of delivery profile of essential amino acids upon skeletal muscle protein synthesis in older men: clinical efficacy of pulse vs. bolus supply. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 309, E450-7. [CrossRef]

- Guan, B.; Luo, J.; Huang, X.; Tian, F.; Sun, S.; Ma, Y.; Yu, Y.; Liu, R.; Cao, J.; Fan, L. Association between thyroid hormone levels and frailty in the community-dwelling oldest-old: a cross-sectional study. Chin. Med. J. 2022, 135, 1962–1968. [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.-Q.; Deng, C.-J.; Wang, Q.-Q.; Zhao, L.-M.; Jiao, B.-W.; Xiang, Y. The role of TGF-β signaling in muscle atrophy, sarcopenia and cancer cachexia. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2024, 353, 114513. [CrossRef]

- Baczek, J.; Silkiewicz, M.; Wojszel, Z.B. Myostatin as a Biomarker of Muscle Wasting and other Pathologies-State of the Art and Knowledge Gaps. Nutrients 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.L.; Vissing, J.; Krag, T.O. Antimyostatin treatment in health and disease: the story of great expectations and limited success. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Rooks, D.; Swan, T.; Goswami, B.; Filosa, L.A.; Bunte, O.; Panchaud, N.; Coleman, L.A.; Miller, R.R.; Garcia Garayoa, E.; Praestgaard, J.; Perry, R.G.; Recknor, C.; Fogarty, C.M.; Arai, H.; Chen, L.-K.; Hashimoto, J.; Chung, Y.-S.; Vissing, J.; Laurent, D.; Petricoul, O.; Roubenoff, R. Bimagrumab vs Optimized Standard of Care for Treatment of Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2020836. [CrossRef]

- Curcio, F.; Ferro, G.; Basile, C.; Liguori, I.; Parrella, P.; Pirozzi, F.; Della-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Testa, G.; Tocchetti, C.G.; Bonaduce, D.; Abete, P. Biomarkers in sarcopenia: A multifactorial approach. Exp. Gerontol. 2016, 85, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.A.; Whittington, R.A.; Baldwin, M.R. Critical illness and the frailty syndrome: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 130, 1545–1555. [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.; Martucci, M.; Mosconi, G.; Chiariello, A.; Cappuccilli, M.; Totti, V.; Santoro, A.; Franceschi, C.; Salvioli, S. GDF15 plasma level is inversely associated with level of physical activity and correlates with markers of inflammation and muscle weakness. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 915. [CrossRef]

- Mallardo, M.; Daniele, A.; Musumeci, G.; Nigro, E. A Narrative Review on Adipose Tissue and Overtraining: Shedding Light on the Interplay among Adipokines, Exercise and Overtraining. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Desmedt, S.; Desmedt, V.; De Vos, L.; Delanghe, J.R.; Speeckaert, R.; Speeckaert, M.M. Growth differentiation factor 15: A novel biomarker with high clinical potential. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2019, 56, 333–350. [CrossRef]

- Merchant, R.A.; Morley, J.E.; Izquierdo, M. Editorial: Exercise, aging and frailty: Guidelines for increasing function. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 405–409. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, L.E.; Villareal, D.T. Physical exercise as therapy for frailty. Nestle Nutr. Inst. Workshop Ser. 2015, 83, 83–92. [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, R.; Hammert, W.B.; Yamada, Y.; Song, J.S.; Seffrin, A.; Kang, A.; Spitz, R.W.; Wong, V.; Loenneke, J.P. The Plateau in Muscle Growth with Resistance Training: An Exploration of Possible Mechanisms. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 31–48. [CrossRef]

- Mcleod, J.C.; Currier, B.S.; Lowisz, C.V.; Phillips, S.M. The influence of resistance exercise training prescription variables on skeletal muscle mass, strength, and physical function in healthy adults: An umbrella review. J. Sport Health Sci. 2024, 13, 47–60. [CrossRef]

- Furrer, R.; Handschin, C. Molecular aspects of the exercise response and training adaptation in skeletal muscle. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 223, 53–68. [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.C.; Zierath, J.R. Influence of AMP-activated protein kinase and calcineurin on metabolic networks in skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 295, E545-52. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Collins, P.; Rattray, M. Identifying and managing malnutrition, frailty and sarcopenia in the community: A narrative review. Nutrients 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Tittikpina, N.K.; Issa, A.; Yerima, M.; Dermane, A.; Dossim, S.; Salou, M.; Bakoma, B.; Diallo, A.; Potchoo, Y.; Diop, Y.M. Aging and nutrition: theories, consequences, and impact of nutrients. Curr. Pharmacol. Rep. 2019, 5, 232–243. [CrossRef]

- Bunchorntavakul, C.; Reddy, K.R. Review article: malnutrition/sarcopenia and frailty in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 64–77. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, G.L. Nutrition and healthy ageing: Emphasis on brain, bone, and muscle. In Pathy’s principles and practice of geriatric medicine; Sinclair, A. J., Morley, J. E., Vellas, B., Cesari, M., Munshi, M., Eds.; Wiley, 2022; pp. 165–176 ISBN 9781119484202.

- Remelli, F.; Vitali, A.; Zurlo, A.; Volpato, S. Vitamin D deficiency and sarcopenia in older persons. Nutrients 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Orkaby, A.R.; Dushkes, R.; Ward, R.; Djousse, L.; Buring, J.E.; Lee, I.-M.; Cook, N.R.; LeBoff, M.S.; Okereke, O.I.; Copeland, T.; Manson, J.E. Effect of Vitamin D3 and Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation on Risk of Frailty: An Ancillary Study of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2231206. [CrossRef]

- Halfon, M.; Phan, O.; Teta, D. Vitamin D: a review on its effects on muscle strength, the risk of fall, and frailty. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 953241. [CrossRef]

- Prado, C.M.; Landi, F.; Chew, S.T.H.; Atherton, P.J.; Molinger, J.; Ruck, T.; Gonzalez, M.C. Advances in muscle health and nutrition: A toolkit for healthcare professionals. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 2244–2263. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Cano, A.M.; Calzada-Mendoza, C.C.; Estrada-Gutierrez, G.; Mendoza-Ortega, J.A.; Perichart-Perera, O. Nutrients, mitochondrial function, and perinatal health. Nutrients 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Baltzer, C.; Tiefenböck, S.K.; Frei, C. Mitochondria in response to nutrients and nutrient-sensitive pathways. Mitochondrion 2010, 10, 589–597. [CrossRef]

- De Bandt, J.-P. Leucine and Mammalian Target of Rapamycin-Dependent Activation of Muscle Protein Synthesis in Aging. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2616S-2624S. [CrossRef]

- Gagesch, M.; Wieczorek, M.; Vellas, B.; Kressig, R.W.; Rizzoli, R.; Kanis, J.; Willett, W.C.; Egli, A.; Lang, W.; Orav, E.J.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A. Effects of Vitamin D, Omega-3 Fatty Acids and a Home Exercise Program on Prevention of Pre-Frailty in Older Adults: The DO-HEALTH Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Frailty Aging 2023, 12, 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Montoya, I.; Correa-Pérez, A.; Abraha, I.; Soiza, R.L.; Cherubini, A.; O’Mahony, D.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J. Nonpharmacological interventions to treat physical frailty and sarcopenia in older patients: a systematic overview - the SENATOR Project ONTOP Series. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 721–740. [CrossRef]

- Basaria, S.; Coviello, A.D.; Travison, T.G.; Storer, T.W.; Farwell, W.R.; Jette, A.M.; Eder, R.; Tennstedt, S.; Ulloor, J.; Zhang, A.; Choong, K.; Lakshman, K.M.; Mazer, N.A.; Miciek, R.; Krasnoff, J.; Elmi, A.; Knapp, P.E.; Brooks, B.; Appleman, E.; Aggarwal, S.; Bhasin, S. Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 109–122. [CrossRef]

- Abati, E.; Manini, A.; Comi, G.P.; Corti, S. Inhibition of myostatin and related signaling pathways for the treatment of muscle atrophy in motor neuron diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 374. [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, G.B.; Cederholm, T.; Avesani, C.M.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Bellizzi, V.; Cuerda, C.; Cupisti, A.; Sabatino, A.; Schneider, S.; Torreggiani, M.; Fouque, D.; Carrero, J.J.; Barazzoni, R. Nutritional status and the risk of malnutrition in older adults with chronic kidney disease - implications for low protein intake and nutritional care: A critical review endorsed by ERN-ERA and ESPEN. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 443–457. [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Baiamonte, E.; Guarrera, M.; Parisi, A.; Ruffolo, C.; Tagliaferri, F.; Barbagallo, M. Healthy aging and dietary patterns. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Rane, B.R.; Amkar, A.J.; Patil, V.S.; Vidhate, P.K.; Patil, A.R. Opportunities and challenges in the development of functional foods and nutraceuticals. In Formulations, regulations, and challenges of nutraceuticals; Apple Academic Press: New York, 2024; pp. 227–254 ISBN 9781003412496.

- Pandey, P.; Pal, R.; Koli, M.; Malakar, R.K.; Verma, S.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, P. A traditional review: the utilization of nutraceutical as a traditional cure for the modern world at current prospectus for multiple health conditions. J. Drug Delivery Ther. 2024, 14, 154–163. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, V.; Subbarayan, K.; Viswanathan, S.; Subramanian, K. Role of nutraceuticals in the management of lifestyle diseases. In Role of herbal medicines: management of lifestyle diseases; Dhara, A. K., Mandal, S. C., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 461–478 ISBN 978-981-99-7702-4.

- Sharma, M.; Vidhya C. S.; Ojha, K.; Yashwanth B. S.; Singh, B.; Gupta, S.; Pandey, S.K. The role of functional foods and nutraceuticals in disease prevention and health promotion. EJNFS 2024, 16, 61–83. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, I.; Habib, M.; Bashir, K.; Jan, K.; Jan, S. Introduction to functional foods and nutraceuticals. In Functional foods and nutraceuticals: chemistry, health benefits and the way forward; Bashir, K., Jan, K., Ahmad, F. J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; pp. 1–15 ISBN 978-3-031-59364-2.

- Hasler, C.M. Functional foods: benefits, concerns and challenges-a position paper from the american council on science and health. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 3772–3781. [CrossRef]

- Regulation of functional foods and nutraceuticals: A global perspective; Hasler, C. M., Ed.; Wiley, 2005; ISBN 9780470277676.

- Bioactive components in milk and dairy products; Park, Y. W., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780813819822.

- Swinbanks, D.; O’Brien, J. Japan explores the boundary between food and medicine. Nature 1993, 364, 180–180. [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.Y.-T.; Lai, J.M.C.; Chan, A.W.-K. Regulations and protection for functional food products in the United States. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 17, 540–551. [CrossRef]

- Tonucci, D. A historical overview of food regulations in the United States. In History of food and nutrition toxicology; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 183–214 ISBN 9780128212615.

- Fernandes, F.A.; Carocho, M.; Prieto, M.A.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Heleno, S.A. Nutraceuticals and dietary supplements: balancing out the pros and cons. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 6289–6303. [CrossRef]

- Lähteenmäki-Uutela, A.; Rahikainen, M.; Lonkila, A.; Yang, B. Alternative proteins and EU food law. Food Control 2021, 130, 108336. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Díaz, L.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Cámara, M. An international regulatory review of food health-related claims in functional food products labeling. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 68, 103896. [CrossRef]

- Moors, E.H.M. Functional foods: regulation and innovations in the EU. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 2012, 25, 424–440. [CrossRef]

- Gulati, O.P.; Berry Ottaway, P.; Coppens, P. Botanical Nutraceuticals, (Food Supplements, Fortified and Functional Foods) in the European Union with Main Focus on Nutrition And Health Claims Regulation. In Nutraceutical and functional food regulations in the united states and around the world; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 221–256 ISBN 9780124058705.

- Bhoite, A.M.; Patil, U.P.; Bagul, H.U.; Talele, S.G.; Jadhav, A. Overview of formulation, challenges, and regulation for the development of nutraceutical. In Formulations, regulations, and challenges of nutraceuticals; Apple Academic Press: New York, 2024; pp. 3–27 ISBN 9781003412496.

- AlAli, M.; Alqubaisy, M.; Aljaafari, M.N.; AlAli, A.O.; Baqais, L.; Molouki, A.; Abushelaibi, A.; Lai, K.-S.; Lim, S.-H.E. Nutraceuticals: Transformation of Conventional Foods into Health Promoters/Disease Preventers and Safety Considerations. Molecules 2021, 26. [CrossRef]

- Yegin, S.; Kopec, A.; Kitts, D.D.; Zawistowski, J. Dietary fiber: a functional food ingredient with physiological benefits. In Dietary sugar, salt and fat in human health; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 531–555 ISBN 9780128169186.

- Damián, M.R.; Cortes-Perez, N.G.; Quintana, E.T.; Ortiz-Moreno, A.; Garfias Noguez, C.; Cruceño-Casarrubias, C.E.; Sánchez Pardo, M.E.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G. Functional foods, nutraceuticals and probiotics: A focus on human health. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Tabashsum, Z.; Anderson, M.; Truong, A.; Houser, A.K.; Padilla, J.; Akmel, A.; Bhatti, J.; Rahaman, S.O.; Biswas, D. Effectiveness of probiotics, prebiotics, and prebiotic-like components in common functional foods. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safety 2020, 19, 1908–1933. [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.B. Diet strategies for promoting healthy aging and longevity: An epidemiological perspective. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 295, 508–531. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, B.L.; Pinho-Gomes, A.-C.; Woodward, M. Addressing the global obesity burden: a gender-responsive approach to changing food environments is needed. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2024, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Coates, P.M.; Bailey, R.L.; Blumberg, J.B.; El-Sohemy, A.; Floyd, E.; Goldenberg, J.Z.; Gould Shunney, A.; Holscher, H.D.; Nkrumah-Elie, Y.; Rai, D.; Ritz, B.W.; Weber, W.J. The evolution of science and regulation of dietary supplements: past, present, and future. J. Nutr. 2024, 154, 2335–2345. [CrossRef]

- Amanullah, M.; Nahid, M.; Hosen, S.Z.; Akther, S.; Kauser-Ul-Alam, M. The nutraceutical value of foods and its health benefits: A review. Health Dyn. 2024, 1, 273–283. [CrossRef]

- Valero-Vello, M.; Peris-Martínez, C.; García-Medina, J.J.; Sanz-González, S.M.; Ramírez, A.I.; Fernández-Albarral, J.A.; Galarreta-Mira, D.; Zanón-Moreno, V.; Casaroli-Marano, R.P.; Pinazo-Duran, M.D. Searching for the Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Neuroprotective Potential of Natural Food and Nutritional Supplements for Ocular Health in the Mediterranean Population. Foods 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Puri, V.; Nagpal, M.; Singh, I.; Singh, M.; Dhingra, G.A.; Huanbutta, K.; Dheer, D.; Sharma, A.; Sangnim, T. A comprehensive review on nutraceuticals: therapy support and formulation challenges. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Zou, L.; Zhang, R.; Salvia-Trujillo, L.; Kumosani, T.; Xiao, H. Enhancing nutraceutical performance using excipient foods: designing food structures and compositions to increase bioavailability. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safety 2015, 14, 824–847. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.F.S.; Martins, J.T.; Duarte, C.M.M.; Vicente, A.A.; Pinheiro, A.C. Advances in nutraceutical delivery systems: From formulation design for bioavailability enhancement to efficacy and safety evaluation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 270–291. [CrossRef]

- Riar, C.S.; Panesar, P.S. Bioactive compounds and nutraceuticals: classification, potential sources, and application status. In Bioactive Compounds and Nutraceuticals from Dairy, Marine, and Nonconventional Sources: Extraction Technology, Analytical Techniques, and Potential Health Prospects; Apple Academic Press: New York, 2024; pp. 3–60 ISBN 9781003452768.

- Sathyanarayana, R. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research & Development.

- Zhang, Z.; Bao, J. Recent advances in modification approaches, health benefits, and food applications of resistant starch. Starch/Stärke 2023, 75. [CrossRef]

- Ayua, E.O.; Kazem, A.E.; Hamaker, B.R. Whole grain cereal fibers and their support of the gut commensal Clostridia for health. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre 2020, 100245. [CrossRef]

- Vegetables as sources of nutrients and bioactive compounds: health benefits. In Handbook of vegetable preservation and processing; Hui, Y. H., Evranuz, E. �g�l, Eds.; CRC Press, 2015; pp. 24–45 ISBN 9780429173073.

- Kabir, M.T.; Rahman, M.H.; Shah, M.; Jamiruddin, M.R.; Basak, D.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Bhatia, S.; Ashraf, G.M.; Najda, A.; El-Kott, A.F.; Mohamed, H.R.H.; Al-Malky, H.S.; Germoush, M.O.; Altyar, A.E.; Alwafai, E.B.; Ghaboura, N.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Therapeutic promise of carotenoids as antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents in neurodegenerative disorders. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112610. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Rauf, A.; Tareq, A.M.; Jahan, S.; Emran, T.B.; Shahriar, T.G.; Dhama, K.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; Aljohani, A.S.M.; Rebezov, M.; Uddin, M.S.; Jeandet, P.; Shah, Z.A.; Shariati, M.A.; Rengasamy, K.R. Potential health benefits of carotenoid lutein: An updated review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 154, 112328. [CrossRef]

- Palamutoğlu, R.; Palamutoğlu, M.İ. Beneficial health effects of collagen hydrolysates. In; Studies in natural products chemistry; Elsevier, 2024; Vol. 80, pp. 477–503 ISBN 9780443155895.

- Harris, M.; Potgieter, J.; Ishfaq, K.; Shahzad, M. Developments for collagen hydrolysate in biological, biochemical, and biomedical domains: A comprehensive review. Materials (Basel) 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Barati, M.; Jabbari, M.; Navekar, R.; Farahmand, F.; Zeinalian, R.; Salehi-Sahlabadi, A.; Abbaszadeh, N.; Mokari-Yamchi, A.; Davoodi, S.H. Collagen supplementation for skin health: A mechanistic systematic review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 2820–2829. [CrossRef]

- Geng, R.; Kang, S.-G.; Huang, K.; Tong, T. Boosting the photoaged skin: the potential role of dietary components. Nutrients 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Weiskirchen, S.; Weiper, K.; Tolba, R.H.; Weiskirchen, R. All You Can Feed: Some Comments on Production of Mouse Diets Used in Biomedical Research with Special Emphasis on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Research. Nutrients 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Dutta, A.; Panchali, T.; Khatun, A.; Kar, R.; Das, T.K.; Phoujdar, M.; Chakrabarti, S.; Ghosh, K.; Pradhan, S. Advances in therapeutic applications of fish oil: A review. Measurement: Food 2024, 13, 100142. [CrossRef]

- Tański, W.; Świątoniowska-Lonc, N.; Tabin, M.; Jankowska-Polańska, B. The Relationship between Fatty Acids and the Development, Course and Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Altemimi, A.; Lakhssassi, N.; Baharlouei, A.; Watson, D.G.; Lightfoot, D.A. Phytochemicals: Extraction, Isolation, and Identification of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Extracts. Plants 2017, 6. [CrossRef]

- Marmitt, D.J.; Bitencourt, S.; da Silva, G.R.; Rempel, C.; Goettert, M.I. Traditional plants with antioxidant properties in clinical trials-A systematic review. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 5647–5667. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Kaur, G.; Ali, S.A. Dairy-Based Probiotic-Fermented Functional Foods: An Update on Their Health-Promoting Properties. Fermentation 2022, 8, 425. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Dhaneshwar, S. Role of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in management of inflammatory bowel disease: Current perspectives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 2078–2100. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Xie, B.; Wan, C.; Song, R.; Zhong, W.; Xin, S.; Song, K. Enhancing Soil Health and Plant Growth through Microbial Fertilizers: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Sustainable Agricultural Practices. Agronomy 2024, 14, 609. [CrossRef]

- Ballini, A.; Charitos, I.A.; Cantore, S.; Topi, S.; Bottalico, L.; Santacroce, L. About functional foods: the probiotics and prebiotics state of art. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Torky, A.; Saad, S.; Eltanahy, E. Microalgae as dietary supplements in tablets, capsules, and powder. In Handbook of Food and Feed from Microalgae; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 357–369 ISBN 9780323991964.

- Lopes, M.; Coimbra, M.A.; Costa, M. do C.; Ramos, F. Food supplement vitamins, minerals, amino-acids, fatty acids, phenolic and alkaloid-based substances: An overview of their interaction with drugs. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 4106–4140. [CrossRef]

- “Francisc I. Rainer” Institute of Anthropology, Bucharest, Romania; Petre, L.; Popescu-Spineni, D.; “Francisc I. Rainer” Institute of Anthropology, Bucharest, Romania; “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania Dietary supplements for joint disorders from a lifestyle medicine perspective. LMRR 2023, 1, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Pérez, K.M.; Ruiz-Pulido, G.; Medina, D.I.; Parra-Saldivar, R.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Insight of nanotechnological processing for nano-fortified functional foods and nutraceutical-opportunities, challenges, and future scope in food for better health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 4618–4635. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E.F.; Souza, S. Formulation Strategies for Improving the Stability and Bioavailability of Vitamin D-Fortified Beverages: A Review. Foods 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Zacharodimos, N.; Georgiopoulos, G.; Athanasaki, C.; Bothou, D.-L.; Tsitsou, S.; Lympaki, F.; Vitsou-Anastasiou, S.; Papadopoulou, O.S.; Delialis, D.; Alexopoulos, E.C.; Petsiou, E.; Keramida, K.; Doulgeraki, A.I.; Patsopoulou, I.-M.; Nychas, G.-J.E.; Tassou, C.C. Two-Month Consumption of Orange Juice Enriched with Vitamin D3 and Probiotics Decreases Body Weight, Insulin Resistance, Blood Lipids, and Arterial Blood Pressure in High-Cardiometabolic-Risk Patients on a Westernized Type Diet: Results from a Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Nutraceuticals, nutritional therapy, phytonutrients, and phytotherapy for improvement of human health: a perspective on plant biotechnology application. Recent Pat. Biotechnol. 2007, 1, 75–97. [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Datta, K.; Datta, S.K. Rice Biofortification: High Iron, Zinc, and Vitamin-A to Fight against “Hidden Hunger.” Agronomy 2019, 9, 803. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Cheng, K.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mou, H.; Sun, H. Microalgal protein for sustainable and nutritious foods: A joint analysis of environmental impacts, health benefits and consumer’s acceptance. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104278. [CrossRef]

- Gebregziabher, B.S.; Gebremeskel, H.; Debesa, B.; Ayalneh, D.; Mitiku, T.; Wendwessen, T.; Habtemariam, E.; Nur, S.; Getachew, T. Carotenoids: Dietary sources, health functions, biofortification, marketing trend and affecting factors – A review. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2023, 14, 100834. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.P.; Ansell, J.; Drummond, L.N. The nutritional and health attributes of kiwifruit: a review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 2659–2676. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, C.; Prakash, D. Nutraceuticals for geriatrics. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2015, 5, 5–14. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hamidu, S.; Yang, X.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, L.; Oduro, P.K.; Li, Y. Dietary supplements and natural products: an update on their clinical effectiveness and molecular mechanisms of action during accelerated biological aging. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 880421. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Verma, A.; Ashique, S.; Bhowmick, M.; Mohanto, S.; Singh, A.; Gupta, M.; Gupta, A.; Haider, T. Unlocking the role of herbal cosmeceutical in anti-ageing and skin ageing associated diseases. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2024, 43, 211–226. [CrossRef]

- Dama, A.; Shpati, K.; Daliu, P.; Dumur, S.; Gorica, E.; Santini, A. Targeting metabolic diseases: the role of nutraceuticals in modulating oxidative stress and inflammation. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.A.; Joo, B.J.; Lee, J.S.; Ryu, G.; Han, M.; Kim, W.Y.; Park, H.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, C.S. Phytochemicals as Anti-Inflammatory Agents in Animal Models of Prevalent Inflammatory Diseases. Molecules 2020, 25. [CrossRef]

- Tansey, M.G.; Wallings, R.L.; Houser, M.C.; Herrick, M.K.; Keating, C.E.; Joers, V. Inflammation and immune dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 657–673. [CrossRef]

- Standaert, D.G.; Harms, A.S.; Childers, G.M.; Webster, J.M. Disease mechanisms as subtypes: Inflammation in Parkinson disease and related disorders. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2023, 193, 95–106. [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.W.; Lim, B.O. Nutritional interventions using functional foods and nutraceuticals to improve inflammatory bowel disease. J. Med. Food 2020, 23, 1136–1145. [CrossRef]

- Makuch, S.; Więcek, K.; Woźniak, M. The Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Curcumin on Immune Cell Populations, Cytokines, and In Vivo Models of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Bordoloi, D.; Padmavathi, G.; Monisha, J.; Roy, N.K.; Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin, the golden nutraceutical: multitargeting for multiple chronic diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1325–1348. [CrossRef]

- Monroy, A.; Lithgow, G.J.; Alavez, S. Curcumin and neurodegenerative diseases. Biofactors 2013, 39, 122–132. [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, A.; Wahid, F.; Lee, Y.S. Curcumin in cancer chemoprevention: molecular targets, pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and clinical trials. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2010, 343, 489–499. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Sasi, P.; Gupta, V.H.; Rai, G.; Amarapurkar, D.N.; Wangikar, P.P. Protective effect of curcumin, silymarin and N-acetylcysteine on antitubercular drug-induced hepatotoxicity assessed in an in vitro model. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2012, 31, 788–797. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, P.; Misra, A.; Surin, W.R.; Jain, M.; Bhatta, R.S.; Pal, R.; Raj, K.; Barthwal, M.K.; Dikshit, M. Anti-platelet effects of Curcuma oil in experimental models of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion and thrombosis. Thromb. Res. 2011, 127, 111–118. [CrossRef]

- Izem-Meziane, M.; Djerdjouri, B.; Rimbaud, S.; Caffin, F.; Fortin, D.; Garnier, A.; Veksler, V.; Joubert, F.; Ventura-Clapier, R. Catecholamine-induced cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction and mPTP opening: protective effect of curcumin. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302, H665-74. [CrossRef]

- Chandran, B.; Goel, A. A randomized, pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of curcumin in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Phytother. Res. 2012, 26, 1719–1725. [CrossRef]

- Nagajyothi, F.; Zhao, D.; Weiss, L.M.; Tanowitz, H.B. Curcumin treatment provides protection against Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 110, 2491–2499. [CrossRef]

- Benameur, T.; Soleti, R.; Panaro, M.A.; La Torre, M.E.; Monda, V.; Messina, G.; Porro, C. Curcumin as Prospective Anti-Aging Natural Compound: Focus on Brain. Molecules 2021, 26. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-S.; Lee, B.-S.; Semnani, S.; Avanesian, A.; Um, C.-Y.; Jeon, H.-J.; Seong, K.-M.; Yu, K.; Min, K.-J.; Jafari, M. Curcumin extends life span, improves health span, and modulates the expression of age-associated aging genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Rejuvenation Res. 2010, 13, 561–570. [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Montecucco, F.; Carbone, F.; Sahebkar, A. Effects of curcumin on aging: molecular mechanisms and experimental evidence. Biomed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 8972074. [CrossRef]

- Turer, B.Y.; Sanlier, N. Relationship of Curcumin with Aging and Alzheimer and Parkinson Disease, the Most Prevalent Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Narrative Review. Nutr. Rev. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Balić, A.; Vlašić, D.; Žužul, K.; Marinović, B.; Bukvić Mokos, Z. Omega-3 Versus Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Prevention and Treatment of Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaer, A.E.; Buddenbaum, N.; Shaikh, S.R. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, specialized pro-resolving mediators, and targeting inflammation resolution in the age of precision nutrition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2021, 1866, 158936. [CrossRef]

- Villaldama-Soriano, M.A.; Rodríguez-Cruz, M.; Hernández-De la Cruz, S.Y.; Almeida-Becerril, T.; Cárdenas-Conejo, A.; Wong-Baeza, C. Pro-inflammatory monocytes are increased in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and suppressed with omega-3 fatty acids: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2022, 29, 855–864. [CrossRef]

- Hernando, S.; Requejo, C.; Herran, E.; Ruiz-Ortega, J.A.; Morera-Herreras, T.; Lafuente, J.V.; Ugedo, L.; Gainza, E.; Pedraz, J.L.; Igartua, M.; Hernandez, R.M. Beneficial effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids administration in a partial lesion model of Parkinson’s disease: The role of glia and NRf2 regulation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 121, 252–262. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Higuera, A.; Peña-Montes, C.; Barroso-Hernández, A.; López-Franco, Ó.; Oliart-Ros, R.M. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and its use in Parkinson’s disease. In Treatments, nutraceuticals, supplements, and herbal medicine in neurological disorders; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 675–702 ISBN 9780323900522.

- Li, P.; Song, C. Potential treatment of Parkinson’s disease with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 180–191. [CrossRef]

- Ceccarini, M.R.; Ceccarelli, V.; Codini, M.; Fettucciari, K.; Calvitti, M.; Cataldi, S.; Albi, E.; Vecchini, A.; Beccari, T. The Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid EPA, but Not DHA, Enhances Neurotrophic Factor Expression through Epigenetic Mechanisms and Protects against Parkinsonian Neuronal Cell Death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Jazvinšćak Jembrek, M.; Oršolić, N.; Mandić, L.; Sadžak, A.; Šegota, S. Anti-Oxidative, Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Apoptotic Effects of Flavonols: Targeting Nrf2, NF-κB and p53 Pathways in Neurodegeneration. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Yahfoufi, N.; Alsadi, N.; Jambi, M.; Matar, C. The Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Role of Polyphenols. Nutrients 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.; Dixit, M. Role of polyphenols and other phytochemicals on molecular signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 504253. [CrossRef]

- Moraes, D.S.; Moreira, D.C.; Andrade, J.M.O.; Santos, S.H.S. Sirtuins, brain and cognition: A review of resveratrol effects. IBRO Rep. 2020, 9, 46–51. [CrossRef]

- Gengatharan, A.; Che Zahari, C.-N.-M.; Mohamad, N.-V. Exploring lycopene: A comprehensive review on its food sources, health benefits and functional food applications. CNF 2024, 20, 914–931. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.-C.; McIntosh, M.K. Potential mechanisms by which polyphenol-rich grapes prevent obesity-mediated inflammation and metabolic diseases. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2011, 31, 155–176. [CrossRef]

- Falsafi, S.R.; Rostamabadi, H.; Babazadeh, A.; Tarhan, Ö.; Rashidinejad, A.; Boostani, S.; Khoshnoudi-Nia, S.; Akbari-Alavijeh, S.; Shaddel, R.; Jafari, S.M. Lycopene nanodelivery systems; recent advances. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 378–399. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.K.; Das, R.; Ray, A.K.; Mishra, S.K.; Anand, S. Recent insights on pharmacological potential of lycopene and its nanoformulations: an emerging paradigm towards improvement of human health. Phytochem. Rev. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zou, Q.; Suo, Y.; Tan, X.; Yuan, T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X. Lycopene ameliorates systemic inflammation-induced synaptic dysfunction via improving insulin resistance and mitochondrial dysfunction in the liver-brain axis. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 2125–2137. [CrossRef]

- Mrowicka, M.; Mrowicki, J.; Kucharska, E.; Majsterek, I. Lutein and Zeaxanthin and Their Roles in Age-Related Macular Degeneration-Neurodegenerative Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, M.; Ohno, K. Gut microbiota changes and parkinson’s disease: what do we know, which avenues ahead. In Gut microbiota in aging and chronic diseases; Marotta, F., Ed.; Healthy ageing and longevity; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; Vol. 17, pp. 257–278 ISBN 978-3-031-14022-8.

- Yan, F.; Polk, D.B. Probiotics and Probiotic-Derived Functional Factors-Mechanistic Insights Into Applications for Intestinal Homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1428. [CrossRef]

- Gou, H.-Z.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Ren, L.-F.; Li, Z.-J.; Zhang, L. How do intestinal probiotics restore the intestinal barrier? Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 929346. [CrossRef]

- Thangaleela, S.; Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Kesika, P.; Chaiyasut, C. Role of probiotics and diet in the management of neurological diseases and mood states: A review. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Ray Chaudhuri, K.; Reynolds, R.; Tan, E.-K.; Pettersson, S. The role of gut dysbiosis in Parkinson’s disease: mechanistic insights and therapeutic options. Brain 2021, 144, 2571–2593. [CrossRef]

- Cristofori, F.; Dargenio, V.N.; Dargenio, C.; Miniello, V.L.; Barone, M.; Francavilla, R. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Effects of Probiotics in Gut Inflammation: A Door to the Body. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 578386. [CrossRef]

- Gazerani, P. Probiotics for parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Leta, V.; Ray Chaudhuri, K.; Milner, O.; Chung-Faye, G.; Metta, V.; Pariante, C.M.; Borsini, A. Neurogenic and anti-inflammatory effects of probiotics in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review of preclinical and clinical evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 98, 59–73. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, K.; Dedeepiya, V.D.; Yamamoto, N.; Ikewaki, N.; Sonoda, T.; Iwasaki, M.; Kandaswamy, R.S.; Senthilkumar, R.; Preethy, S.; Abraham, S.J.K. Benefits of Gut Microbiota Reconstitution by Beta 1,3-1,6 Glucans in Subjects with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. J Alzheimers Dis 2023, 94, S241–S252. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y.; Zhu, X.; Ai, Q.; Shi, Y. β-glucan protects against necrotizing enterocolitis in mice by inhibiting intestinal inflammation, improving the gut barrier, and modulating gut microbiota. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 14. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, A. Antiinflammatory Herbal Supplements. In Translational Inflammation; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 69–91 ISBN 9780128138328.

- Angelopoulou, E.; Paudel, Y.N.; Papageorgiou, S.G.; Piperi, C. Elucidating the Beneficial Effects of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) in Parkinson’s Disease. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 5, 838–848. [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, A.H.; Casolaro, V.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Keyvani, H.; Taghinezhad-S, S. Modulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway by probiotics as a fruitful target for orchestrating the immune response. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Al-Harrasi, A.; Bhatia, S.; Behl, T.; Kaushik, D. Effects of essential oils on CNS. In Role of Essential Oils in the Management of COVID-19; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2022; pp. 269–297 ISBN 9781003175933.

- Gachowska, M.; Szlasa, W.; Saczko, J.; Kulbacka, J. Neuroregulatory role of ginkgolides. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 5689–5697. [CrossRef]

- Sahin, K.; Pala, R.; Tuzcu, M.; Ozdemir, O.; Orhan, C.; Sahin, N.; Juturu, V. Curcumin prevents muscle damage by regulating NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways and improves performance: an in vivo model. J. Inflamm. Res. 2016, 9, 147–154. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, G.; Zhou, D. The curcumin analog EF24 is a novel senolytic agent. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 771–782. [CrossRef]

- Nocito, M.C.; De Luca, A.; Prestia, F.; Avena, P.; La Padula, D.; Zavaglia, L.; Sirianni, R.; Casaburi, I.; Puoci, F.; Chimento, A.; Pezzi, V. Antitumoral activities of curcumin and recent advances to improve its oral bioavailability. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Padilha de Lima, A.; Macedo Rogero, M.; Araujo Viel, T.; Garay-Malpartida, H.M.; Aprahamian, I.; Lima Ribeiro, S.M. Interplay between Inflammaging, Frailty and Nutrition in Covid-19: Preventive and Adjuvant Treatment Perspectives. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2022, 26, 67–76. [CrossRef]

- McCarty, M.F.; Lerner, A. Nutraceuticals targeting generation and oxidant activity of peroxynitrite may aid prevention and control of parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.C.; Neher, J.J. Inflammatory neurodegeneration and mechanisms of microglial killing of neurons. Mol. Neurobiol. 2010, 41, 242–247. [CrossRef]

- AlFadhly, N.K.Z.; Alhelfi, N.; Altemimi, A.B.; Verma, D.K.; Cacciola, F.; Narayanankutty, A. Trends and technological advancements in the possible food applications of spirulina and their health benefits: A review. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Araiza, C.; Álvarez-Mejía, A.L.; Sánchez-Torres, S.; Farfan-García, E.; Mondragón-Lozano, R.; Pinto-Almazán, R.; Salgado-Ceballos, H. Effect of natural exogenous antioxidants on aging and on neurodegenerative diseases. Free Radic. Res. 2013, 47, 451–462. [CrossRef]

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; Chandra, N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 118–126. [CrossRef]

- Amir Aslani, B.; Ghobadi, S. Studies on oxidants and antioxidants with a brief glance at their relevance to the immune system. Life Sci. 2016, 146, 163–173. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.Y.; Chaturvedi, S.; Ibrahim, B.; Khan, M.S.; Jain, H.; Nama, N.; Jain, V. Hearbal detox extract formulation from seven wonderful natural herbs: garlic, ginger, honey, carrots, aloe vera, dates, & corn. AJPRD 1970, 7, 22–30. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, J.-G.; Yang, W.; Xu, P.; Xiao, Y.-L.; Zhang, H.-T. 6-Gingerol attenuates LPS-induced neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment partially via suppressing astrocyte overactivation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 1523–1529. [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.E.; Mocan, A.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Popa, D.-S. Health Benefits of Nut Consumption in Middle-Aged and Elderly Population. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Nassiri-Asl, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. The role of saffron and its main components on oxidative stress in neurological diseases: A review. In Oxidative stress and dietary antioxidants in neurological diseases; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 359–375 ISBN 9780128177808.

- Gurău, F.; Baldoni, S.; Prattichizzo, F.; Espinosa, E.; Amenta, F.; Procopio, A.D.; Albertini, M.C.; Bonafè, M.; Olivieri, F. Anti-senescence compounds: A potential nutraceutical approach to healthy aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 46, 14–31. [CrossRef]

- Verburgh, K. Nutrigerontology: why we need a new scientific discipline to develop diets and guidelines to reduce the risk of aging-related diseases. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 17–24. [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.; Accardi, G.; Candore, G.; Carruba, G.; Davinelli, S.; Passarino, G.; Scapagnini, G.; Vasto, S.; Caruso, C. Nutrigerontology: a key for achieving successful ageing and longevity. Immun. Ageing 2016, 13, 17. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Bhawal, S.; Kapila, S.; Yadav, H.; Kapila, R. Health-promoting role of dietary bioactive compounds through epigenetic modulations: a novel prophylactic and therapeutic approach. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 619–639. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Q.C.; Dos Santos, T.W.; Fortunato, I.M.; Ribeiro, M.L. The molecular mechanism of polyphenols in the regulation of ageing hallmarks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Di Micco, R.; Krizhanovsky, V.; Baker, D.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Cellular senescence in ageing: from mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 75–95. [CrossRef]

- Sen, C.K.; Khanna, S.; Roy, S. Tocotrienols in health and disease: the other half of the natural vitamin E family. Mol. Aspects Med. 2007, 28, 692–728. [CrossRef]

- von Kobbe, C. Targeting senescent cells: approaches, opportunities, challenges. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 12844–12861. [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Sun, S.; Ma, S.; Liu, X.; Chan, P.; Sun, L.; Song, M.; Zhang, W.; Liu, G.-H.; Qu, J. Low-dose quercetin positively regulates mouse healthspan. Protein Cell 2019, 10, 770–775. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, B.J.; Rakshe, P.S.; Maurya, N.; Chib, S.; Singh, S. Unlocking the therapeutic potential of natural stilbene: Exploring pterostilbene as a powerful ally against aging and cognitive decline. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 92, 102125. [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, O.; Kujawska, M. Urolithin A in health and diseases: prospects for parkinson’s disease management. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Manocha, S.; Dhiman, S.; Grewal, A.S.; Guarve, K. Nanotechnology: An approach to overcome bioavailability challenges of nutraceuticals. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 72, 103418. [CrossRef]

- Pateiro, M.; Gómez, B.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Barba, F.J.; Putnik, P.; Kovačević, D.B.; Lorenzo, J.M. Nanoencapsulation of promising bioactive compounds to improve their absorption, stability, functionality and the appearance of the final food products. Molecules 2021, 26. [CrossRef]

- de Toro-Martín, J.; Arsenault, B.J.; Després, J.-P.; Vohl, M.-C. Precision nutrition: A review of personalized nutritional approaches for the prevention and management of metabolic syndrome. Nutrients 2017, 9. [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. Genetic variants in the metabolism of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids: their role in the determination of nutritional requirements and chronic disease risk. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2010, 235, 785–795. [CrossRef]

- Martens, C.R.; Wahl, D.; LaRocca, T.J. Personalized medicine: will it work for decreasing age-related morbidities? In Aging; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 683–700 ISBN 9780128237618.