2. Background Discussion

In the view of Democritos, atoms have existed for ever. He formulated his hypothesis on the basis that they are too small to be perceived by our senses and are also in constant motion. Nonetheless, matter (owing to the existence of atoms) could not be infinitely divisible, as claimed by Aristotle [

2]. Similar views were held many centuries later by Dalton [

3] who added the idea of indistinguishability between atoms of a given species (at the time, isotopes were not known) but whose atoms remained eternal, solid objects with a definite boundary, intercombining to form matter, while the vacuum played a lesser role. Pascal [

4] attempted to reconcile the views of Aristotle with those of Democritos by imagining infinitely divisible atoms, but this to no avail.

The next important step is of course the Rutherford-Bohr planetary model of the atom [

5] which transformed the original concepts of Democritos and Dalton, because nearly all the solidity of atoms was transferred to the nucleus (an earlier suggestion of this kind had been made by Perrin [

6] but Rutherford proved the point experimentally). As a result, an empty space appeared

within the atom, since the electron (also solid, but too small to be of any significance) was thought to orbit inside it. When Rutherford [

7] subsequently broke even the nucleus into fragments (protons and neutrons), they, in a sense, took over the original role of the atoms of Democritos regarding solidity. By virtue of the Pauli exclusion principle, since these particles have half-integral spin, they reject others of the same type from within their volume, as does also the electron, which guarantees their integrity. However, an important difference concerns lifetimes: the neutron is unstable outside the atomic nucleus. It can only become stable in association with a proton, because of the mass-energy conservation rule, whereas the proton and the electron both have lifetimes in excess of the age of the universe [

8], as do also non-radioactive atoms.

The question of an “empty space” or vacuum within the atom is partly obscured by Quantum Mechanics, which replaces the point-like electron of the Bohr theory by a “wave-particle” or “wavicle” pervading the atomic void until a position measurement is actually performed and the wavefunction collapses [

9]. Thus, two kinds of “emptiness” emerge in Physics: an empty space external to the atom, containing no bound electrons at all (by analogy with the totally empty space of Democritos, which contains no atoms) and a space within the atom, which may or may not contain bound electrons somewhere inside, either of these possibilities being the potential outcome of a measurement. Regarding the first of these spaces, one could be still more draconian and insist that a “clean” or truly empty vacuum should contain no electrons of any kind whatsoever, even those of negative energy introduced by Dirac [

10]. Such a space can only exist well away from any atoms, perhaps even outside the expanding universe, in a region not yet reached by energy or by matter.

The different kinds of vacuum are mutually exclusive. Absolutely empty vacuum is clearly hypothetical, and the more draconian one is about what to exclude from it, the less it is observable. “Nearly empty” space, within which bound electrons are located, contains the idealised structure of an isolated atom, with outer boundary conditions set at infinity for its ground state wavefunction. In other words, all the accessible empty space comes within the atom as far as this amazingly simple model is concerned. Interestingly, Hawking [

11] once proposed adapting the Schrödinger equation as a model for the expanding universe, with a central gravitational field, mainly because its boundary conditions extend out towards infinity, but this idea has apparently not been taken any further.

Another reason exists for which the different spaces (inside and outside the atom) are fundamentally different from each other. It is related to the properties of time and to the fact that, although the universe expands, atoms never change in size. They remain identical to each other within a given species in the ground state anywhere and for all of time, as Democritos had originally suggested. So, the volume of the internal atomic space does not change. This is consistent with elementary Quantum Mechanics, which depends only on the masses and charges of the electron, proton and neutron, on the constancy of the velocity of light and of Planck’s constant but never introduces the gravitational constant

G or any distortion of space-time into its equations. Time itself is not even a proper operator in Quantum Theory and, although measurable as time intervals, only allows fixed atomic frequencies to appear as discrete transitions in the frame of reference of the stationary atom. This property is exploited for the extremely accurate calibration of time intervals [

12], but yields no other information about the nature of time itself, such as its direction or magnitude.

Time intervals can be measured directly to an accuracy of nearly 247.10

-21 s, but the age of the universe places time itself on a completely different scale, extending to 13.8 billion years. Thus, there is no sense to introducing

G into the equations of Quantum Mechanics. Atoms, to all intents and purposes, remain identical to each other in all their properties wherever they may be and for all of time, except perhaps in the immediate vicinity of a black hole, where even the definitions of the constants in quantum mechanics presumably break down. For extremely intense pulses, so short that the Uncertainty principle comes into play and that energies of twice the rest mass of the electron can be reached, virtual electron-positron pairs can briefly be extracted from the vacuum close to atoms. Therefore, the local vacuum external to atoms is in this sense not completely empty. It is subject to quantum fluctuations which are the cause of the Casimir effect [

13].

Quantum Mechanics leaves the nature of any boundary between the inside and the outside of the atom rather diffuse, both conceptually and in practice. It therefore disagrees from the outset with the simple models of both Democritos and Dalton, for whom atoms and the vacuum remained distinctly separate rom each other as constituents of reality.

3. Atomic Compressibility

Quantum Mechanics also differs fundamentally from other models in allowing an individual atom to be a compressible object. Dalton and Democritos [

1,

3] had both excluded this possibility and Bohr and Rutherford [

5] had not considered it in the context of their planetary model. The existence of atomic compressibility is not immediately obvious, first, because Quantum Theory introduces idealised boundary conditions at infinity for free atoms and, second, because there is no sharply defined atomic surface to refer to in defining its size. In Quantum Mechanics, atomic compressibility first emerges when one addresses related problems, such as an isolated atom inside a spherical shell (which can be attractive or repulsive) [

14], an atom in a hard cavity [

15], or an atom subjected to external pressure, for example, trapped within a bubble inside a solid [

16].

In all cases of this type, theory and experiment both reveal (a) that the volume of the atom, obtained from the expectation value of its mean radius, is changed (b) that ground state and the spectral lines of atoms are shifted and (c) that the atom responds to these changes by itself exerting a pressure on the environment. None of these changes have anything to do with bond formation. They are the response to applied pressure of a neutral coulombic fluid made up from a nucleus and its associated electrons and occur in the absence of chemical binding. The atom is far from being a hard object, as imagined by Democritos and Dalton. In fact, it behaves like a “soft” material, whose response is nonlinear : it becomes harder the more it is compressed.

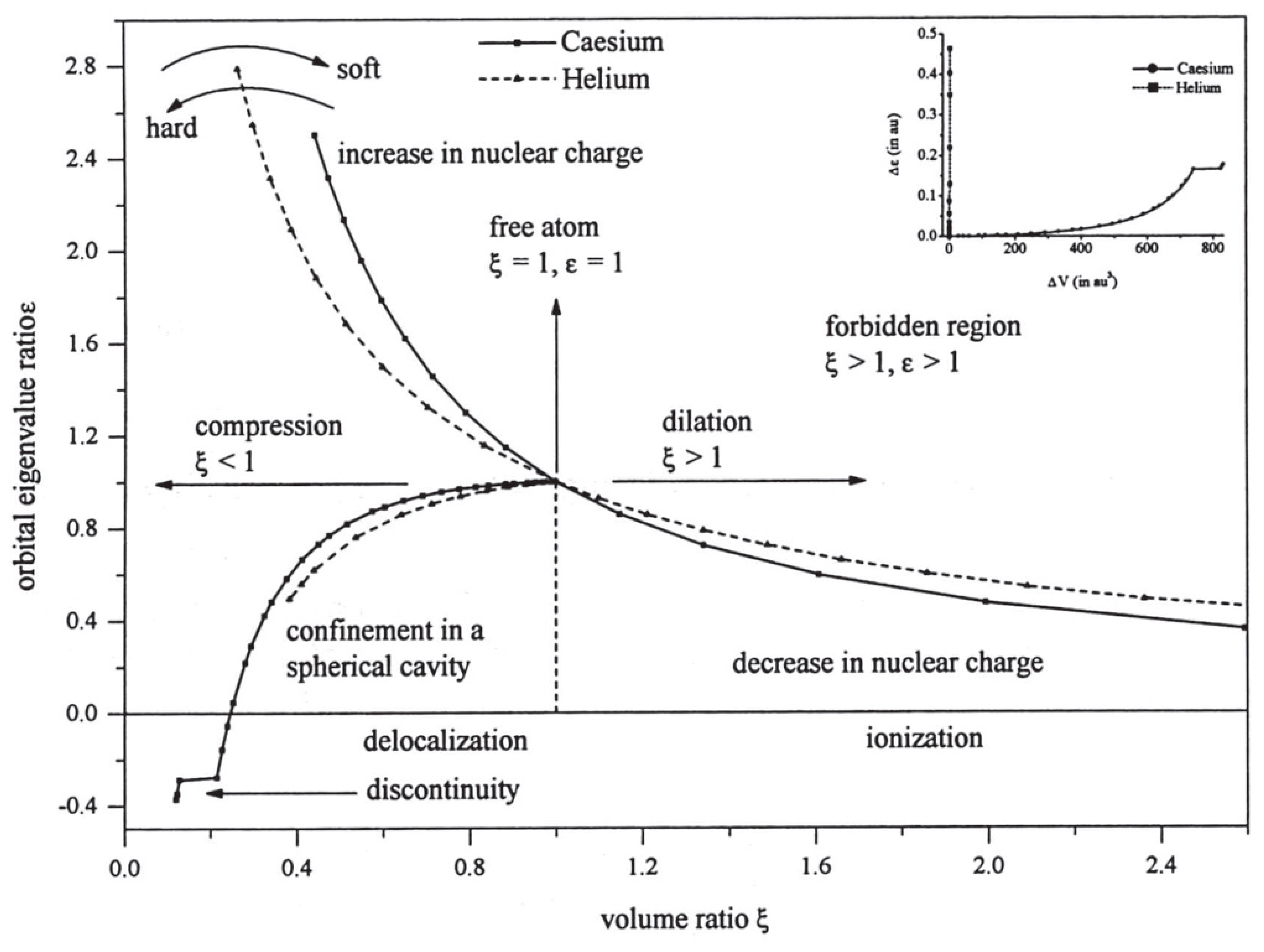

In order to study these changes from atom to atom, it is useful to divide the atomic volume obtained under compression or dilation by the volume of the “free” atom. The latter is of course not obtained from boundary conditions, but from the expectation value of radius for the outermost electron. This ratio, or strain, is a pure number which removes many of the changes in volume from atom to atom in the Periodic Table and yields a better understanding of atomic elasticity. Similarly, the energy of the atom under pressure is referred to the ground state energy for the “free” atom, which provides a dimensionless measure of applied stress (see [

17] for details). One finds that atomic stress/strain curves share certain common characteristics (see

Figure 1). Obviously, they all pass through the point (1,1) but, in addition, they nearly all exhibit a very similar nonlinear structure. This occurs even for the examples shown in

Figure 1 which involve volumes differing in magnitude by a factor of about 2000. Clearly, the curves are highly non-linear, and the similarity between them is merely a manifestation of the inverse square forces at play.

An exception to this behaviour occurs at very high pressures. Certain atoms, most notably from the long periods of the Periodic Table (transition elements) are able to their structure spontaneously under pressure, owing to the fact that the order of filling of the

s-d and

d-f electronic shells is altered from the rules for “free” atoms [

18]. When this happens, a reordered configuration first comes very close in energy to the usual atomic configuration and then crosses below it, becoming more favourable in energy and therefore constituting a “new” ground state under high pressures. This process leads to configuration mixing phenomena, and thus to avoided crossings between states sharing the same total angular momentum.

The root cause of the avoided crossings is that the balance between the inner and outer reaches of the effective radial potential for

d or for

f electrons is upset. As a consequence, there is a sudden reordering of the shell structure (see [

19] for a detailed explanation of this ‘orbital collapse’ effect). When it atoms of the transition periods progressively revert to what would be the expected order of filling if the ‘

aufbau prinzip’ alone were adhered to without any s-d or d-f competition in the filling of subshells. As with all avoided crossings, this also opens a pathway for Landau-Zener transitions [

20,

21] when sufficiently short and intense excitation pulses are applied.

This reorganisation of the outermost shell structure, is a purely quantum effect, due to the double-well effective radial potentials in the long periods of many-electron atoms. When it occurs, the valence and elasticity properties of an atom are obviously transformed. Hence, one can understand that chemistry under very high pressure is no longer the same as for ordinary pressures. The critical point at which the transition occurs differs enormously from one atom to another, and rather elaborate ab initio calculations are required to make predictions. This is especially true in the 4f and 5f sequences, where relativistic effects critically influence the balance between inner and outer wells.

As long as atoms do not undergo any fundamental reorganisation of the shell structure, i.e., as long as they retain the same configuration as normal under dilation or compression, all the changes remain reversible and can be termed

isoelectronic. For atoms in a crystal lattice, a profound change of shell structure would imply recrystallisation, with attendant losses of energy and, of course, of reversibility. Such considerations might apply, for example, when studying the reversible storage of lithium ions within a lattice by polaronic distortion of the host structure, or the structure of certain atomic clusters as a function of their size, since they would impose a limit to the allowable structural change in order to preserve reversibility [

22].

The compressibility of individual atoms emerges as a new and fundamental property of which is of strictly quantum mechanical origin. Elasticity and compressibility are usually described in classical physics as a resulting purely from changes in the mean separation between atoms. Here, we introduce a new form, in which the expectation value of the size of individual atoms responds to changes in their local environment.

If we examine the Periodic Table in this light, we see at once that there are enormous variations of “hardness” according to position expected from atom to atom. For example, the helium atom is clearly the hardest of the Table because of its 1s2 closed shell configuration, as revealed by its very high ionisation potential, and, likewise, the Li+ ion is the most compact and stable of the singly-charged ions. This accounts, not only for the wonderful electrical properties of the ion, but also for its extremely valuable mobility and insertion capabilities : it can be implanted in microscopic cavities of solid or composite electrodes, which remain stable in air when warm, although solid lithium electrodes would become highly reactive and explosive under the same circumstances.

At the other extreme, we see a wide panoply of non-alkali ‘soft’ atoms, readily deformable even within alloys and compounds. They are concentrated amongst rare earths, transition metals, lanthanides and even actinides. Their properties are especially sensitive along a broad diagonal in the quasi-periodic table of Smith and Kmetko [

23]. This, again, arises from purely quantum effects : whereas the hardness of He-like ions is due to their closed shell structure (the angular part of the Schrödinger equation), the ‘softness’ of Transition metals results from the radial part of the same equation for many-electron species. Detailed calculations are required to study the result of “squeezing” all the atoms of the Periodic Table [

24]. The outcome of such computations is clearly model-dependent to some extent, especially for the heavier species.

The existence of an internal “atomic vacuum” is the key to understanding a broad range of deformation processes of individual atoms by which their chemistry is mostly unaffected, but only their size and related physical properties. As the pressure is further increased (beyond a limit which must of course be determined for each species) we enter a new regime where the ground state of an atom and its related chemistry must change, i.e., the structure of the Periodic Table itself is altered by an externally applied pressure [

18].