Submitted:

24 September 2024

Posted:

25 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Circular Economy, SMEs and Supply Chains

2.2. Experiential Learning

2.3. Circular Supply Chains in SMEs for Experiential Learning

- A concrete experience might consist of learners perceiving and interacting with supply chains (and their relevant stakeholders) in a real-world situation involving issues, challenges or problems related to waste generation or the linear economy in organisations. These activities might be accomplished by field visits, talking to guest speakers, simulations, or hands-on activities in immersive experiences.

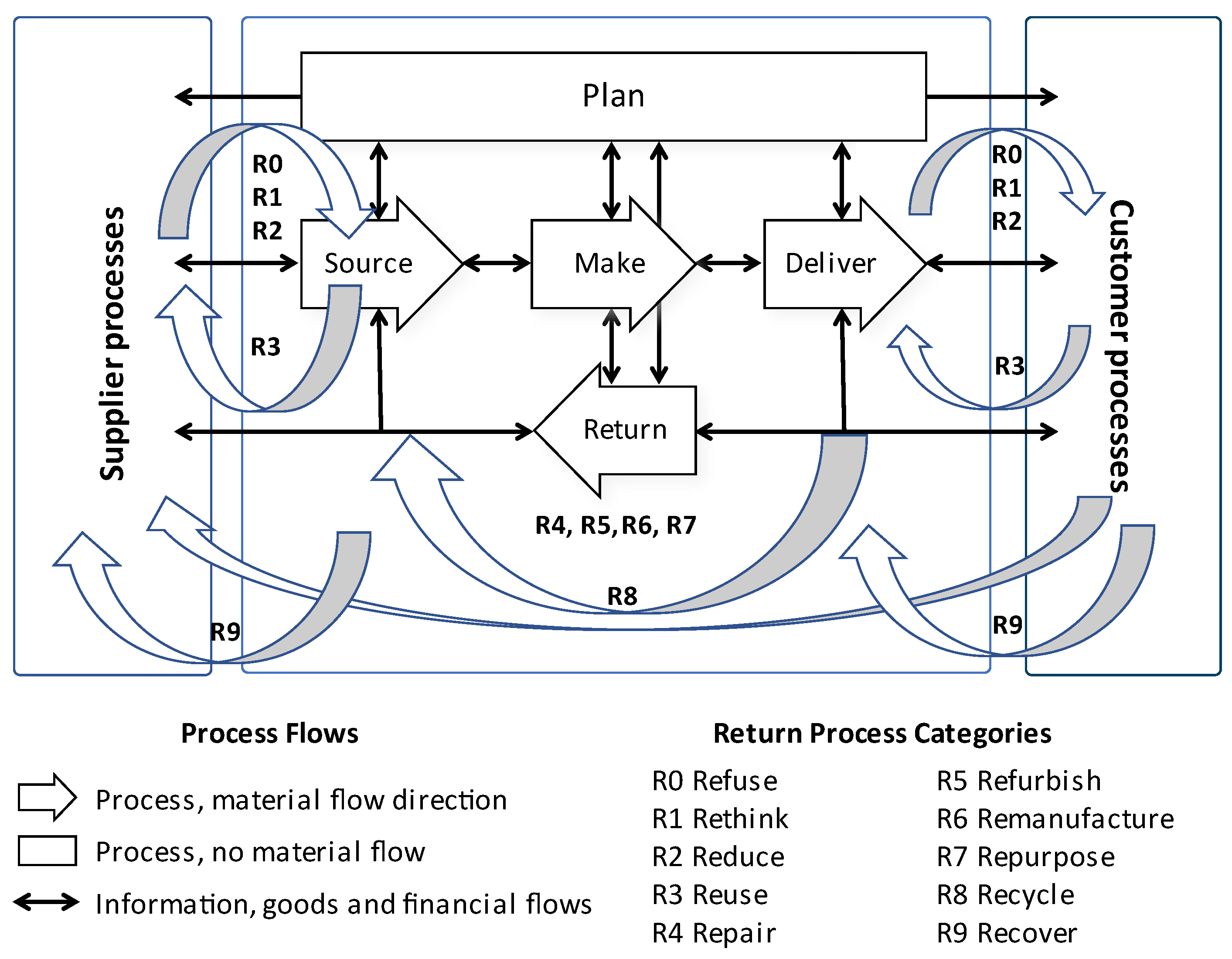

- The reflective observation takes place by critically assessing CE-related scenarios within SCM. This is to comprehensively understand the underlying principles, identify potential barriers and challenges, and consider the possible implications. Effective pedagogical approaches include class discussions, group reflections, and self-assessments, where students analyse and interpret their experiences, identifying key insights and lessons learned through SCM and CE models and frameworks application. This is the case of the SCOR [23] and the Ellen McArthur butterfly models [4] for the biochemical restoration or the maintenance, reuse/redistribution, refurbishment/remanufacturing, and recycling of materials, components or parts in manufacturing, production or service processes.

- Abstract conceptualisation involves students generating new ideas, establishing connections, and developing innovative solutions for supply chain challenges within the CE. This approach may include designing CE strategies for specific supply chain operations scenarios, developing circular design solutions, proposing CE performance metrics, reconfiguring supply chains, or creating circular business models to achieve zero waste and minimise social and economic impact.

- Active experimentation entails engagement and encourages students to design, test, and validate CE strategies in real-world contexts. This active involvement can manifest as implementation plans, demonstrations, practical applications, presentations, debates, role-plays, or simulations. The objective is to enable learners to evaluate their proposals, obtain feedback, and reach a consensus on feasible solutions in supply chain practice.

- Accordingly, this work looks at learning experiences based on experiential learning to achieve educational objectives, cover specific disciplinary contents, and develop specific learning outcomes. However, these learning experiences require an instructional design to undertake their particular activities.

3. Methodology

- Define what to study relative to the research question (RQ), using the underlying theories and concepts concerning the RQ, the research aim, and the ADDIE model.

- Develop an instructional design and select an instance of a learning experience as an exploratory single case study to advance in answering the RQ. The case study illustrates the instructional design of a learning experience using an in-depth exploration based on the proposed framework. A case study has been selected for this work as it applies to unique situations or explains the implementation of new methods and techniques where there is only one or a small number of occurrences or instances. Therefore, no comparisons are made with control groups to develop inferences or generalisations on instances or situations [54,55,56,57]. The ADDIE model was applied in this work to guide the development of a circular supply chain learning experience for an undergraduate industrial engineering course at Tecnologico de Monterrey in Mexico City, involving a group of SMEs from diverse backgrounds and industries. The ADDIE structure of the learning experience is presented in Table 1.

- Collect data and construct formulations and statements to answer the RQ. This considers a mixed method approach for data collection and analysis, which helps build formulations and statements on the RQ. Students’ and instructors’ reports on the instructional design and learning experiences were collected as primary data. This data provides the necessary background information using the ADDIE model. Additionally, secondary data was collected on institutional and course academic documents such as the syllabus, assignment briefs, and course materials. Students’ examinations were also collected to inform about the numeric evaluations of their learning results (formative or summative), such as exams and reports, assessments of disciplinary and SCM-related learning outcomes, and an assessment of student opinions on the course and the learning experience. Some of this data (i.e., student opinions on the learning experience) are collected through a longitudinal process with an intervening period during an academic term. Later, collected data is analysed by using descriptive statistics (i.e., mean, standard deviation, mode, and interquartile range).

- Evaluate and interpret results against the supporting theories, and redefine or discard statements and claims. If results differ from the theories and claims, these statements will require a redefinition (or being discarded) or further actions (i.e., implementing improvements) on further learning experiences.

- Report findings and decide on further actions using the results. This step refers to the discussion of research findings, including limitations, and future work on further instances of learning experiences, which may require going back to step 2 in a continuous cycle. If claims and statements do not change or vary over further instances of learning experiences, results might be transferred and applied or used to improve future cases.

4. Results

4.1. The Learning Experience

4.2. The Learning Experience Instructional Design According to the ADDIE Model

4.2.1. Analysis

- The course selection: This course refers to the IN3037 Design and Improvement of Logistics Systems, an intermediate course that provides students with advanced concepts of logistics systems, focusing on their analysis and design. Moreover, this course contributes to the ABET accreditation process and the development of engineering student outcomes for undergraduate programs [58]. Finally, this course also incorporates a transdisciplinary competence according to the university educational model to build committed, sustainable and supportive solutions to social problems and needs, through strategies that strengthen democracy and the common good, at the regional and national level. To build these solutions, it relies on theories related to citizenship, social responsibility, and social sciences in general, as well as in research methodologies of social development, which links to the problem it aims to solve.

- Problem situation/challenge definition: This points to sustainability challenges in SME’s supply chains in the aftermath of the global COVID-19 pandemic concerning the CE. SMEs have been disproportionately impacted in their operations by the pandemic at this time, highlighting their vulnerability during such sanitary crises. In the case of Mexico, SMEs are often referred to as the backbone of the Mexican economy, contributing significantly to its Gross Domestic Product (GDP)—approximately 52%—and generating 70% of its formal employment. However, during the pandemic, the Latin-American Association of Small and Medium Enterprises (ALAMPYME) reported in March 2020 that approximately 4.5 million SMEs in the region were navigating through uncertainty and had incurred losses nearing 30,000 million Mexican pesos [59]. The ALAMPYME also highlighted that 77% of SMEs were at risk of ceasing operations, 25% had to lay off employees, 47% were struggling with customers’ receivables, and 87% were facing declines in sales, customers, and new projects. Therefore, Mexican SMEs' limited resources can hinder the integration of sustainable practices into their supply chains. Consequently, challenging learning experiences can play a crucial role in SMEs adopting circular supply chain practices as part of their academic-industrial partnerships, which have turned out mutually beneficial in previous collaborations. Nevertheless, sustainability-related practices require a shift in mindset from short-term profit maximisation to long-term value creation, encompassing environmental and social dimensions. This shift can be challenging in SMEs where the culture may be deeply rooted in traditional businesses. Therefore, a learning experience where industrial engineering students addressed CE issues in SME´s supply chains was relevant and appropriate within the IN3037 Design and Improvement of Logistics Systems course.

- Learning objectives: The IN3037 Design and Improvement of Logistic Systems course aims to teach students to model, design and improve logistic systems, and determine relevant operations costs and appropriate configurations to achieve supply chain integration. The learning content comprises mathematical and conceptual modelling, simulation techniques and technologies, and planning models. Moreover, the learning objective extends to include CE practices within the supply chain design to develop circular supply chain solutions for Mexican SMEs.

- Learning outcomes: This course considers the definition of the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET) of engineering student learning outcome (K), and the university’s ethical commitment and citizenship student outcomes as follows:

- Learning outcome (K) engineering practice as “the ability to use the techniques, skills, and modern engineering tools necessary for engineering practice”.

- Citizenship commitment is “the ability to create committed, sustainable, and supportive solutions to social problems and needs through strategies that strengthen democracy and the common good”.

- Format: The learning experience required an immersive study where students had to observe and collect data directly from SME supply chains. All the course contents were delivered on campus at two different campus locations. In total, eleven SMEs were selected by the instructors involved and assigned to each team of students; the teams varied in size between four to five students each. All SMEs were located in the Mexico City metropolitan area.

- Target learners: Fifty-six seventh-semester industrial and systems engineering students of two cohorts on two different campuses.

4.2.2. Design

- Knowledge acquisition:

- Fundamental SCM and CE concepts to understand the need for circular supply chains;

- Advanced mathematical modelling of supply chain networks for process optimisation;

- Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) model processes and metrics to first diagnose the supply chain “as it is” and then to propose a “to be” design including CE solutions [59]. The activities were as follows:

- A preliminary formulation of the situation using the SCOR [46] model to map the current SME´s supply chain configuration (As Is) and collect data (using a questionnaire) on the existing waste generation at each company;

- The elaboration and agreement of a project charter (with the SME executives) showing milestones, deliverables and roles;

- Quantification of SCOR model metrics and generated waste;

- The elaboration and validation of CE proposals for SME’s supply chain and/or business model redesign to reduce/eliminate waste.

- Teaching and learning approach: Experiential learning.

- (Experiential) learning activities: The learning experience intends students to carry out their activities according to the experiential learning cycle. Table 2 summarises the experiential learning activities concerning the CE and SCOR model. These activities involved disciplinary studies linked to SCM and customer engagement content. These also involved addressing problem situations through synchronous and asynchronous individual and collaborative work among students.

4.2.3. Development

- Educational resources: This course required educational resources involving:

- A syllabus informing students about the learning objectives, learning outcomes, content, learning activities, assessment criteria, learning materials, a reading list, and a bibliography.

- A web-based learning platform in Canvas © to facilitate remote mentoring and virtual collaborative work.

- SCM and CE slide packs and reading lists in the virtual learning platform.

4.2.4. Implementation

- Course module execution: The module was carried out simultaneously on two campuses through regular classroom lectures. This course’s execution of the learning experience occurred over sixteen weeks throughout a semester term. The course involved three-hour teaching sessions plus three hours of on-demand mentoring per week. In addition, students were to conduct three hours of asynchronous collaborative work per week. Accordingly, four teaching sessions dedicated to the learning experience covered:

- An introduction to the study situation, justification, objective, assessment and learning outcomes;

- An exploration of the study situation of SMEs in which supply chain processes impact waste generation. This session aimed at concluding with the concrete experience stage;

- A presentation and discussion of relevant CE and SCM work addressing waste generation in SMEs, this session relates to the reflective observation stage;

- A session regarding alternative solutions to address the current situation using CE and SCM principles, methodologies, and techniques. This session related to the abstract conceptualisation stage.

- A presentation and discussion of students' proposals, implications, limitations and future work. This session related to active experimentation.

- Students’ learning results: Table 3 summarises students’ CE-proposed solutions for the SMEs under study. The proposed solutions were mapped according to the SCOR process types and categories (Return, Source, Make and Deliver). Students initially mapped the supply chain configuration at the present state (not included in this manuscript) and later proposed changes in a future state configuration as summarised in Table 3. These changes included adding or changing suppliers' practices, return processes, and new production/delivery processes. Proposals show proposed changes according to the existing literature in CE, ranging from packaging reduction or elimination to material return and recycling.

4.2.5. Evaluation

- Learning outcomes and experience evaluation: The learning experience covered three categories of evaluations and assessments. First, —summative and formative— evaluations of students’ learning results. Second, a learning outcome assessment of citizenship commitment. Third, a course and learning experience’s student opinion assessment—through the institutional student feedback survey. The specific student evaluations covered:

- Two partial exams and one final exam for summative evaluations;

- Two project partial reports as formative evaluations;

- A project report for a summative evaluation.

- MET—Teaching methodology and learning activities (0 = Very poor and 10 = Exceptional);

- PRA—Concept comprehension based on practical applications (0 = Very poor and 10 = Exceptional);

- ASE—Tutoring (0 = Very poor and 10 = Exceptional);

- EVA—Evaluation and feedback (0 = Very poor and 10 = Exceptional);

- RET—Intellectual challenge (0 = Very poor and 10 = Exceptional);

- APR—Instructor support and commitment (0 = Very poor and 10 = Exceptional);

- DOM—Knowledge proficiency (of the instructor) (0 = Definitively no and

- 10 = Definitively yes);

- REC—Course recommendation (0 = Definitively no and 10 = Definitively yes);

- COM—Students’ comments.

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings

5.2. Limitations

5.2. Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ballou, R.H. Business Logistics/Supply Chain Management : Planning, Organizing, and Controlling the Supply Chain.; Prentice Hall, 2004; ISBN 0-13-123010-7.

- Palma-Mendoza, J.A.; Neailey, K.; Roy, R. Business Process Re-Design Methodology to Support Supply Chain Integration. International Journal of Information Management 2014, 34, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Wang, J.X.; Farooque, M.; Wang, Y.; Choi, T.-M. Multi-Dimensional Circular Supply Chain Management: A Comparative Review of the State-of-the-Art Practices and Research. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2021, 155, 102509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation Towards the Circular Economy Vol. 1: An Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2013;

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Chiaroni, D.; Del Vecchio, P.; Urbinati, A. Designing Business Models in Circular Economy: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Bus Strat Env 2020, 29, 1734–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, R.; Onggo, B.S.; Corlu, C.G.; Nogal, M.; Juan, A.A. The Role of Simulation and Serious Games in Teaching Concepts on Circular Economy and Sustainable Energy. Energies 2021, 14, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Arias-Portela, C.Y.; González De La Cruz, J.R.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E. Experiential Learning for Circular Operations Management in Higher Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J.M.F.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Azapagic, A. Building a Business Case for Implementation of a Circular Economy in Higher Education Institutions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 220, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aming’a, M.; Marwanga, R.; Marendi, P. Circular Economy Educational Approaches for Higher Learning Supply Chains: A Literature Review. In Rethinking Management and Economics in the New 20’s; Santos, E., Ribeiro, N., Eugénio, T., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 197–217. ISBN 978-981-19848-4-6. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano, C.; Samani, P.; Van Der Meer, Y. How Can the Circular Economy Support the Advancement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)? A Comprehensive Analysis. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2023, 40, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P.; Secundo, G.; Mele, G.; Passiante, G. Sustainable Entrepreneurship Education for Circular Economy: Emerging Perspectives in Europe. IJEBR 2021, 27, 2096–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.; Wells, P.K.; Xu, G. How Does Experiential Learning Encourage Active Learning in Auditing Education? Journal of Accounting Education 2021, 54, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M. Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research. J of Engineering Edu 2004, 93, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliń, W.; Nitkiewicz, T.; Chattinnawat, W. Demand for Competences of Industrial Engineering Graduates in the Context of Automation of Manufacturing Processes. Quality Production Improvement - QPI 2019, 1, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguador, J.M.; Dotong, C.I. Engineering Students’ Challenging Learning Experiences and Their Changing Attitude towards Academic Performance. EUROPEAN J ED RES 2020, volume–9–2020, 1127–1140. [CrossRef]

- Vodovozov, V.; Raud, Z.; Petlenkov, E. Challenges of Active Learning in a View of Integrated Engineering Education. Educ. Sci. 2021; 11, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, M.V.; Salvador, R.; do Prado, G.F.; de Francisco, A.C.; Piekarski, C.M. Circular Economy as a Driver to Sustainable Businesses. Cleaner Environmental Systems 2021, 2, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan Kurniawan; Yudi Fernando CIRCULAR ECONOMY SUPPLY CHAIN FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS (SDGS): A REVIEW AND FUTURE OPPORTUNITIES. IJIM 2023, 17, 32–39. [CrossRef]

- Montag, L. Circular Economy and Supply Chains: Definitions, Conceptualizations, and Research Agenda of the Circular Supply Chain Framework. Circ.Econ.Sust. 2023, 3, 35–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Carvajal, D.; Picanço-Rodrigues, V.; Mejía-Argueta, C.; Salinas-Navarro, D.E. A Systems Perspective on Social Indicators for Circular Supply Chains. In The Social Dimensions of the Circular Economy; de Souza Campos, L.M., Vázquez-Brust, D.A., Eds.; Greening of Industry Networks Studies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; Volume 10, pp. 27–52. ISBN 978-3-031-25435-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, P.K.; Malesios, C.; Chowdhury, S.; Saha, K.; Budhwar, P.; De, D. Adoption of Circular Economy Practices in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Evidence from Europe. International Journal of Production Economics 2022, 248, 108496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Malesios, C.; De, D.; Budhwar, P.; Chowdhury, S.; Cheffi, W. Circular Economy to Enhance Sustainability of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises. Bus Strat Env 2020, 29, 2145–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APICS Supply Chain Operations Reference Model SCOR Version 12.0 2017.

- PRME PRME Principles for Responsible Management Education. Available online: https://www.unprme.org/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Responsible Management Education: The PRME Global Movement; Morsing, M., Ed.; Routledge: London New York, NY, 2022; ISBN 978-1-03-203029-6.

- Biggs, J.; Tang, C. Teaching for Quality Learning at University; McGraw-Hill Education: Maidenhead, UNITED KINGDOM, 2011; ISBN 978-0-335-24276-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, A.; Kolb, D. Eight Important Things to Know about The Experiential Learning Cycle. AEL 40 2018.

- Kolb, D. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, N.J, 1984; ISBN 978-0-13-295261-3.

- Kolb, D.A.; Fry, R. Towards an Applied Theory of Experiential_Learning. In Theories of Group Process.; Cooper, C., Ed.; John Wiley.: London, 1975; pp. 33–57.

- Akella, D. Learning Together: Kolb’s Experiential Theory and Its Application. Journal of Management & Organization 2010, 16, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, M.; Jenkins, A. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory and Its Application in Geography in Higher Education. Journal of Geography 2000, 99, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y. The Role of Experiential Learning on Students’ Motivation and Classroom Engagement. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 771272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, J.R.; Karabenick, S.A. Relevance for Learning and Motivation in Education. The Journal of Experimental Education 2018, 86, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, E.; Wildman, J.L.; Piccolo, R.F. Using Simulation-Based Training to Enhance Management Education. AMLE 2009, 8, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Pacheco-Velazquez, E.; Da Silva-Ovando, A.C. (Re-)Shaping Learning Experiences in Supply Chain Management and Logistics Education under Disruptive Uncertain Situations. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1348194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Rodríguez Calvo, E.Z. Social Lab for Sustainable Logistics: Developing Learning Outcomes in Engineering Education. In Operations Management for Social Good; Leiras, A., González-Calderón, C.A., de Brito Junior, I., Villa, S., Yoshizaki, H.T.Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 1065–1074 ISBN 978-3-030-23815-5.

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Mejia-Argueta, C.; Montesinos, L.; Rodriguez-Calvo, E.Z. Experiential Learning for Sustainability in Supply Chain Management Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggu, A.T.; Sundarsingh, J. An Experiential Learning Approach to Fostering Learner Autonomy among Omani Students. JLTR 2019, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkert, C.; van Dam, N. Experiential Learning: What’s Missing in Most Change Programs. Operations 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, A.; Zarama, R. The Process of Embodying Distinctions - a Re-Construction of the Process of Learning. Cybern. Hum. Knowing 1998, 5, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, C.; Putnik, G. Experiential Learning of CAD Systems Interoperability in Social Network-Based Education. Procedia CIRP 2019, 84, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masse, C.; Martinez, P.; Mertiny, P.; Ahmad, R. A Hybrid Method Based on Systems Approach to Enhance Experiential Learning in Mechatronic Education. In Proceedings of the 2019 7th International Conference on Control, Mechatronics and Automation (ICCMA); 2019; pp. 403–407.

- Al-Shammari, M.M. An Exploratory Study of Experiential Learning in Teaching a Supply Chain Management Course in an Emerging Market Economy. JIEB 2022, 15, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulwahed, M.; Nagy, Z.K. Applying Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle for Laboratory Education. J of Engineering Edu 2009, 98, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsteiner, H.; Avery, G.C.; Neumann, R. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model: Critique from a Modelling Perspective. Studies in Continuing Education 2010, 32, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.H. Experiential Learning – a Systematic Review and Revision of Kolb’s Model. Interactive Learning Environments 2020, 28, 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsteiner, H.; Avery, G.C. The Twin-Cycle Experiential Learning Model: Reconceptualising Kolb’s Theory. Studies in Continuing Education 2014, 36, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atstāja, D.; Purviņš, M.; Butkevičs, J.; Uvarova, I.; Cudečka-Puriņa, N. Developing E-Learning Course “Circular Economy” in the Study Process and Adult Education. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 371, 05025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoccaro, I.; Ceccarelli, G.; Fraccascia, L. Features of the Higher Education for the Circular Economy: The Case of Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L. Towards an Education for the Circular Economy (ECE): Five Teaching Principles and a Case Study. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2019, 150, 104406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C. Bringing ADDIE to Life: Instructional Design at Its Best. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia 2003, 12, 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Molenda, M. In Search of the Elusive ADDIE Model. Perf. Improv. 2003, 42, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales González, B. Instructional Design According to the ADDIE Model in Initial Teacher Training. Ap 2022, 14, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. The Academy of Management Review 1989, 14, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Applied social research methods; 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, Calif, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4129-6099-1.

- Tharenou, P.; Donohue, R.; Cooper, B. Case Study Research Designs. In Management Research Methods; Cambridge University Press, 2007; pp. 72–87.

- Rashid, Y.; Rashid, A.; Warraich, M.A.; Sabir, S.S.; Waseem, A. Case Study Method: A Step-by-Step Guide for Business Researchers. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2019, 18, 160940691986242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABET 2022-2023 Criteria for Accrediting Engineering Programs 2021.

- Maraboto Moreno, M. El Efecto COVID-19 en las PYMES. Available online: https://expansion.mx/opinion/2020/06/12/el-efecto-covid-19-en-las-pymes (accessed on 18 September 2024).

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Analysis | 1. Module/Course selection. Choose a module or course covering SCM and CE topics for industrial engineering in Higher Education. 2. Problem situation/challenge definition. Select real-world situations concerning the impact of SME´s supply chain operations on sustainability. 3. Disciplinary learning objectives. Define learning objectives regarding the impact of supply chains on sustainability in SMEs. 4. Learning outcomes and competencies. Determine disciplinary learning outcomes and competencies regarding: The design and development of CE solutions for SCM in SMEs. 5. Format. Select instructional formats for presence, online, blended, or hybrid learning experiences. 6. Target learners. Set learning experiences based on the study level, academic discipline, and academic program. |

| Design | 7. Knowledge acquisition. Define disciplinary topics in SCM related to CE and SMEs. 8. Teaching and learning approach/strategy. Choose experiential learning as the leading instructional approach. 9. (Experiential) Learning activities. Design and describe learning activities amid Kolb’s experiential learning cycle. |

| Development | 10. Educational resources. Prepare educational resources and materials for the course/module. |

| Implementation | 11. Course/Module execution. Carry out the learning experience through lectures, seminars, and other interactions, and obtain students’ learning results. |

| Evaluation | 12. Learning outcomes and experience evaluation. Provide coursework rubrics and student evaluation instruments; Conduct student surveys to obtain feedback on the learning experience and the course. |

| Experiential learning | Activity description | Method steps |

|---|---|---|

| Concrete experience |

Collect quantitative/qualitative data regarding SME supply chain processes and key performance indicators (KPIs) using the SCOR model; Collect and classify qualitative/qualitative data about SME waste generation and management practices. |

Formulation of the situation |

| Reflective observation |

Examine key supply chain processes affecting waste generation; Map supply chain processes at the configuration level. Quantify level 1 and 2 SCOR metrics; Diagnose a problem or issue of concern about supply chain processes waste generation; Relate the problem or issue of concern to CE theory. |

Diagnose |

| Abstract conceptualisation |

Identify waste elimination, reduction or minimisation strategies; Identify changes to the supply chain configuration; Elaborate supply chain improvement proposals. |

Elaboration of proposals |

| Active experimentation |

Evaluate/Validate CE solution proposals considering waste quantification using SCOR KPIs. | Evaluation |

| SCOR processes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMEs | Return process with suppliers | Source | Make | Deliver | Return process with clients | CE strategies (9Rs) | |

| SME 1: Toy retailing | Improvement of forecast accuracy to reduce inventories. Usage of in-house transport |

Bicycle deliveries for local online sales. Packaging material recycling |

Return process of carton board packaging materials | Reuse (R3) and recycle (R8) of packaging materials |

|||

| SME 2: Fuel distribution and sale | Paper waste reduction and recycling from administrative support processes through digital solutions. | Vehicle tyre recycling in fuel transportation. | Reduction (R2) of paper waste. Recycle (R8) of paper Recycle (R8) of tires |

||||

| SME 3: Bakery | Elaboration of compost from organic waste such as fruit peel and eggshell | Introduction of reusable and biodegradable packages and cutlery | Recycle (R8) and reuse (R3) of production materials and packages |

||||

| SME 4: Coffee shop | Packaging material reuse | Packaging material replacement in customer deliveries | Reuse (R3) of packaging materials Reduce (R2) of packaging waste |

||||

| SME 5: Home decoration retail | Change in product design to reduce material waste | Reuse of ornamental plant containers to replace plants at the end of their life | Reduce (R2) of production waste through product design Reuse (R8) of containers |

||||

| SME 6: Tableware retail | Packaging materials reuse | Reduce (R2) of packaging waste Reuse (R3) of packaging materials |

|||||

| SME 7: Beverage syrups production and retail | Replacement of cardboard using reusable plastic boxes in a supply chain return process configuration | Reduce (R2) of packaging waste Reuse (R3) of packaging materials |

|||||

| SME 8: Ice-cream shop | Local supplier utilisation to reduce transport time and emissions | Compost elaboration from organic waste generated in cream production. | Waste reduction in packaging and cutlery switching to biodegradable materials and promoting customers’ container reuse | Reduce (R2) of ice-cream production transportation time. Reduce (R2) of packaging waste Reuse (R3) of packaging materials Repurpose (R7) of organic waste onto compost |

|||

| SME 9: Scaffolding supply | Special paint usage in scaffoldings after customers’ return | Welding reduction in scaffold joints through mechanical clamp use. Production material recycling in new products and spare parts | Scaffold and recyclable plastic cover reduction for tyres and joints |

Reduce (R2) of packaging waste Reuse (R3) of packaging materials Recycling (R8) and repurpose (R7) of production materials |

|||

| SME 10: Sports product retail | Packaging material, cardboard and pallet use reduction | Reduce (R2) of packaging waste. Reuse (R3) of packaging materials. |

|||||

| SME 11: Plastic bottle manufacturing | Plastic material reduction in bottle redesign | Reduce (R2) of material through changes in product design. |

|||||

| Evaluation | 1st partial Exam | 2nd partial exam | Final exam |

Partial project report 1 | Partial project report 2 | Final project |

Final score/ grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (0-100 scale) | 90 | 93.95 | 89.96 | 97.13 | 98.53 | 98.8 | 90.34 |

| Standard Deviation | 7.20 | 3.18 | 15.17 | 3.95 | 1.78 | 2.4 | 1.32 |

| Student learning outcome | Engineering practice (K) | Citizenship commitment (1 below, 2 meets, 3 exceeds expectations) scale |

|---|---|---|

| Median | 3 | 3 |

| Min | 2 | 2 |

| Max | 3 | 3 |

| Q1 | 2.5 | 2 |

| Q3 | 3 | 3 |

| Interquartile Range (IQR) | 0.5 | 1 |

| Achievement level 2 or above | 100% | 100% |

| Achievement level 3 | 72.72% | 63.60% |

| Institutional Student Opinion Survey # student answers (49 out of 56) |

1. MET | 2. PRA | 3. ASE | 4. EVA | 5. RET | 6. APR | 7. DOM | 8. REC | 9. COM (student comments) |

| Mean (0-10 scale) | 9.25 | 9.5 | 9.56 | 9.55 | 9.41 | 9.52 | 9.76 | 9.38 | 100% of comments highlight satisfaction, clarity of explanations and instructors' knowledge proficiency |

| Standard Deviation |

0.91 | 0.91 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.68 | 0.85 |

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Strengths | a. Integration of experiential learning into the ADDIE model as the guiding pedagogical approach. |

| b. Relationship with SMEs as educational partners providing operations and process information. | |

| c. Faculty's pedagogical experience in active learning. | |

| d. Selection of a relatable study topic for both company operations and students' intended learning. | |

| e. High student participation and interest in real-world CE business activities. | |

| f. Students conducting independent research and situated reflective and hands-on learning. | |

| g. Interdisciplinary topic integration (CE, SCOR model, and SCM) to address real-world challenges. | |

| h. CE-related learning in alignment with SDG #4 Quality Education. | |

| Weaknesses | a. Limited study time to address CE topics—just a semester academic period. |

| b. Extra resource allocation to execute the learning experience. | |

| c. No precise impact evaluation of student learning outcomes, knowledge, and skills attainment. | |

| d. No follow-up of CE solutions’ implementations. | |

| Opportunities | a. Exploring additional sustainability topics like gas emissions and energy consumption. |

| b. Expanding the study of CE-related topics to other engineering courses. | |

| c. Transferring this approach and methodology to other instructors. | |

| d. Establishing knowledge exchange partnerships with other local companies. | |

| e. Further explore other disciplinary and interpersonal skills and learning outcomes. | |

| Challenges | a. SME engagement and coordination. |

| b. Reducing extra planning time and effort beyond regular workload allocation. | |

| c. Attaining challenge-expected results in line with intended learning objectives. | |

| d. Maintaining a safe and inclusive learning environment for students in real-world settings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).