1. Introduction

Pine wood nematodes (

Bursaphelenchus xylophilus; PWNs) are responsible for causing pine wilt disease (PWD), which is a serious and often fatal condition for pine trees. Pine species native to Eastern Asia and Western European countries are highly susceptible to PWD, which causes severe damage to forest ecosystems and significant economic losses in the forest product industry [

5].

The current method for controlling PWD mainly relies on insecticide application via

foliar sprays on pine plants to eliminate pine sawyer beetles (

Monochamu spp.), which are insect vectors of PWNs [

11,

14]. Trunk injection of nematicides in pine plants is the most frequently used protocol for preventing PWN proliferation and decreasing the longevity and feeding activity of insect vectors [

12,

24]

. Abamectin (

Avermectin B1) and emamectin benzoate are the two most widely used nematicides and are members of the macrocyclic lactone family [

12]. However, the application of toxic chemicals has raised concerns for nonharmful insects living in forest environments [

1].

Many attempts have been made to develop beneficial eco-friendly compounds with nematicidal activity against PWNs [

3].

Biological control methods for pine wilt disease aim to manage the spread of the nematode and reduce its impact on pine populations. Certain fungi and bacteria are known to kill PWNs; thus, these microorganisms can be used as biological control agents to reduce the population of PWNs [

26,

29]

. Chitosan is frequently used as a potential natural compound to manage plant diseases [

9,

23]. Nunes da Silva et al. [

21]

evaluated the application of different molecular weight chitosans as a soil amendment to control PWD in maritime pine (

Pinus pinaster, very susceptible to the disease) and stone pine (

Pinus pinea, less susceptible). Elicitation with

methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid, and benzo(1,2,3)-thiadiazole-7-carbothioic acid-S-methyl ester via foliar spraying increases tolerance to

B. xylophilus [

18].

The addition of this biofertilizer (mixed with diazotrophic bacteria and a chitosan-producing fungus, Cunninghamella elegans) to soils confers resistance against the PWN in P. pinaster [

21].

Phytoalexins are important secondary metabolites in plant immunity, as they play crucial roles in defending plants against various pathogens. Pinosylvin and its methylated derivatives, pinosylvin monomethyl ether (PME) and dihydropinosylvin monomethyl ether (DPME), are representative phytoalexins found in pine species. Suga et al. [

25] reported that pinosylvin, DPME, and PME are the most toxic compounds against PWNs among the extracted compounds from the Pinaceae family. Although pinosylvin and its methylated derivatives are very toxic to PWNs, these compounds are not detectable or exist in low amounts in the fresh tissue of branches and needles of pine plants [

10,

22,

28], except for nonliving heartwood tissues [

7]. The production of pinosylvin stilbenoids in sapwood and needles in pine is activated only by abiotic and biotic stresses [

6,

8]. In

P. strobus, which is highly resistant to PWD, the accumulation of pinosylvin stilbenoids (PME and DPME) is increased upon PWN infection [

10]. In contrast, in both Korean red pine (

P. densiflora) and Koran pine (

Pinus koraiensis), which are susceptible to PWD, there is no change in these substances upon PWN infection [

10]. On the basis of these results, [

10] proposed that PWD resistance in

P. strobus is related to the ability to synthesize PME and DPME substances upon PWN infection.

To date, no studies have been conducted to increase the synthesis of pinosylvin stilbene through biotic or abiotic stress treatments in pine plants susceptible to PWD. However, increased accumulation of PME and DPME has been reported when calli and cultured cells induced from PWN-susceptible pine species were treated with fungi or fungus-derived elicitors. In the cell culture of

P. sylvestris, treatment with fungal mycelium extracts from

Lophodermium seditiosum strongly increased the accumulation of PME hundreds of times [

17]. Kim et al. [

16] reported that PME and DPME accumulation was highly increased in calli of

P. koraiensis when the callus was treated with fungus-derived elicitors. The above results show that even for PWN-susceptible pine species such as

P. koraiensis and

P. sylvestris, the cultured cells recognized and quickly responded to the fungal elicitor, resulting in increased synthesis of pinosylvin stilbenes. Therefore, it was hypothesized that fungal elicitor treatment of PWD-susceptible pine plants might increase the accumulation of pinosylvin stilbenoid substances, which may confer PWD resistance upon infection with the nematode.

Trunk injection or soil drenching is frequently used for the delivery of pesticides, insecticides, or nutrients into the stems of woody plants. There are no reports of the trunk injection of elicitors for the prevention of PWD. Moreover, no studies have investigated the correlation between PWD resistance and pinosylvin stilbene accumulation by applying biotic and abiotic stimuli to pine plants. Therefore, in this study, pine trees were treated with fungus-derived elicitors to increase the synthesis of pinosylvin stilbenes, and then, we investigated the possible acquisition of PWN resistance in PWN-susceptible P. densiflora.

2. Materials and Methods

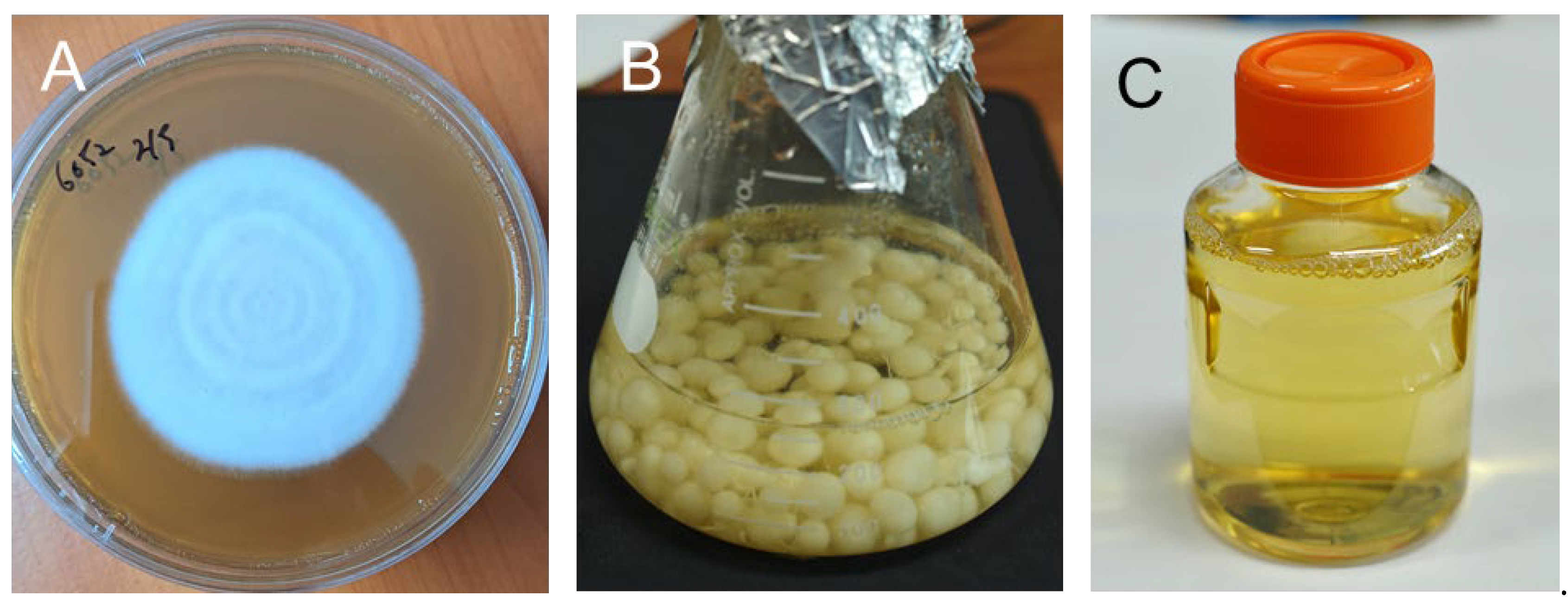

2.1. Preparation of Fungal Elicitors and PWNs

Penicillium chrysogenum KCTC 6052 was provided by KCTC, Biological Resources Center of Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB). To manufacture an elicitor using P. chrysogenum, the fungi were grown in potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich, agar (20 g/L) was added to make a solid medium, and the pH of the medium was adjusted to 5.0 before sterilization. For suspension culture of the fungus, a small amount (1 mL) of the mixed fungal culture medium was inoculated into a 500 ml flask containing 100 ml of PDA liquid medium, and the flasks were agitated on a gyratory shaker at 100 rpm. After 2 weeks of culture, the fungal suspension medium was filtered through filter paper (Whatman No. 1) and filtered again through a 0.45 µm membrane filter. The filtered solution was then autoclaved at 120 °C for 15 minutes and used as an elicitor.

PWNs (

Bursaphelenchus xylophilus) were propagated on filamentous fungi (

Botrytis cinerea), which were subsequently grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) media under dark conditions. The propagated PWNs were isolated via the Baerman funnel method [

31].

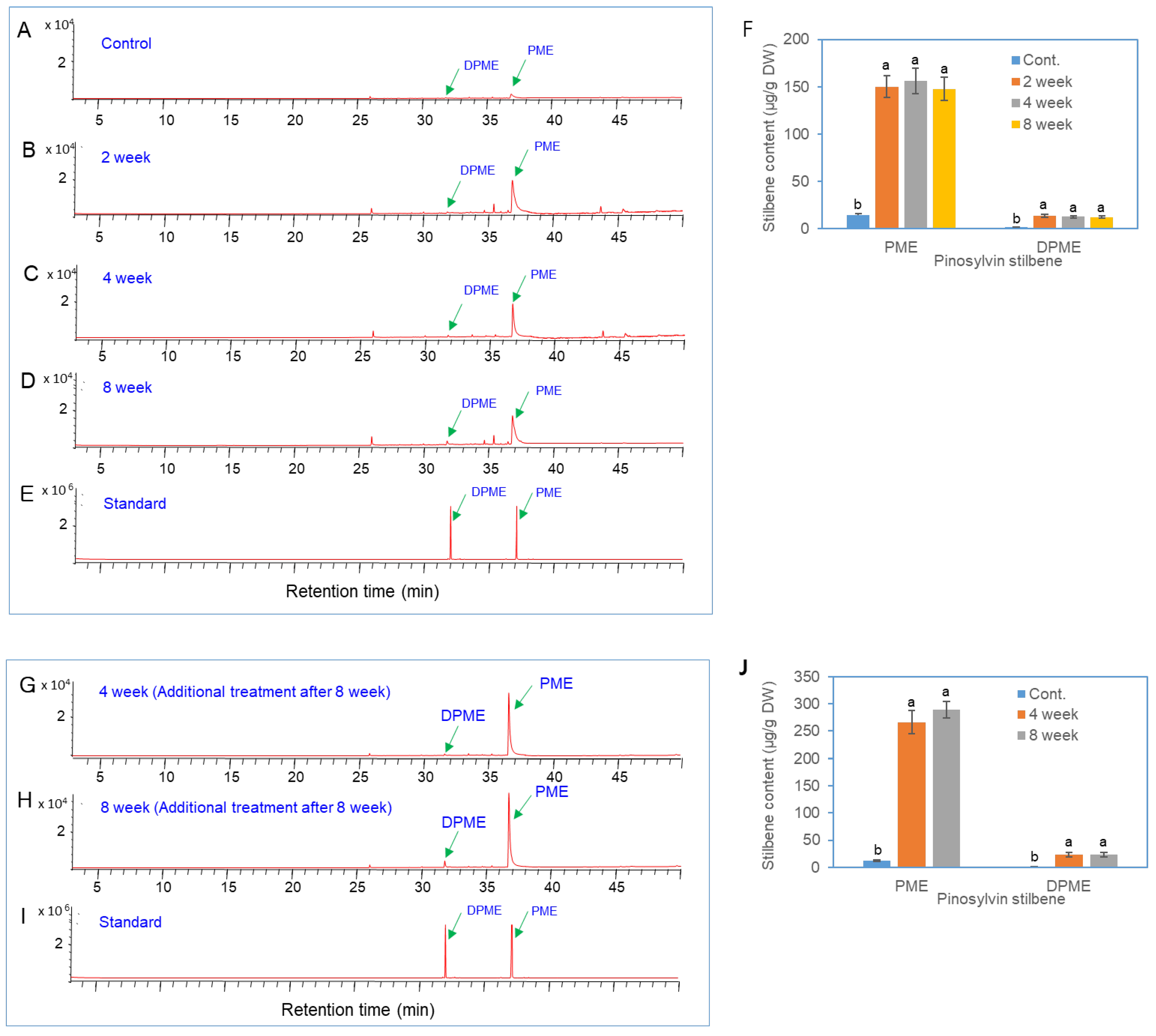

2.2. Fungal Elicitor Treatment of Pine Trees by Soil Drenching

The fungal culture mixture was diluted by adding water to a concentration of 20% (v/v). The fungal culture mixture (500 ml) was applied via soil drenching to a 1 L soil pot where two-year-old Korean red pine trees were planted. As a control, the same amount of PDA medium was diluted with water. Pine leaves were harvested 1 week, 2 weeks, 3 weeks, and 4 weeks after the fungal elicitor was applied to the soil pot and used as materials for analyzing the contents of DPME and PME via GC/MS. To investigate the effects of multiple fungal elicitor treatments, the same amount of fungal culture mixture (500 ml) was subjected to soil drenching after 8 weeks of the first fungal elicitor treatment. Pine leaves were harvested 2 and 4 weeks after the additional fungal elicitor treatment to analyze the contents of DPME and PME.

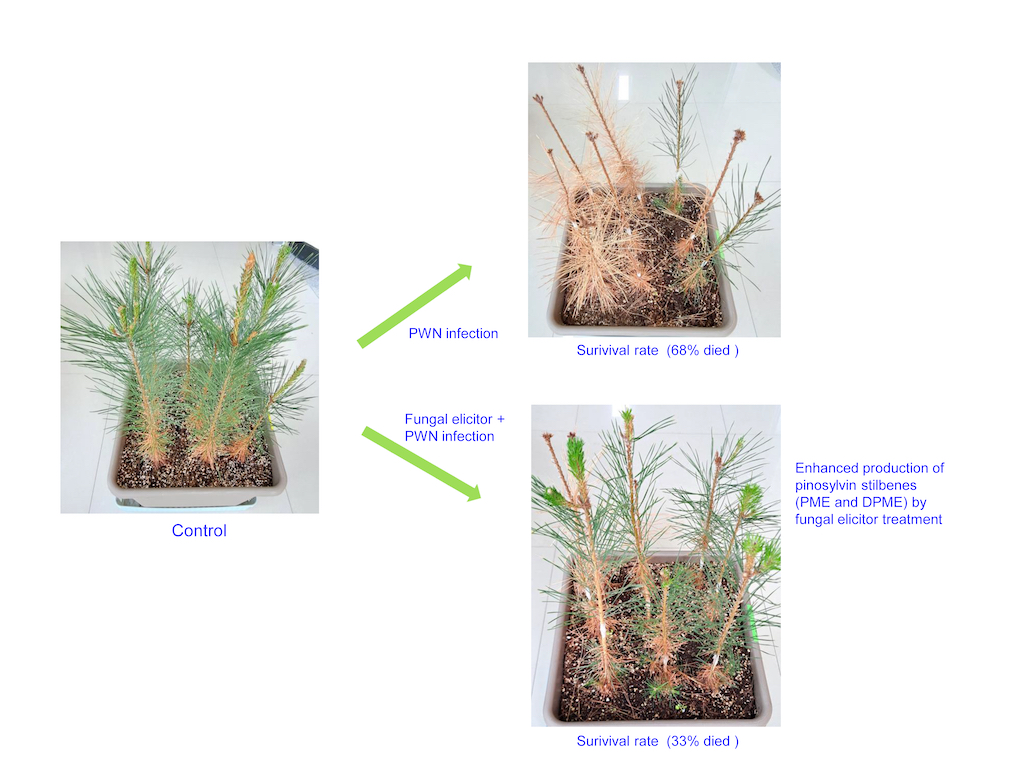

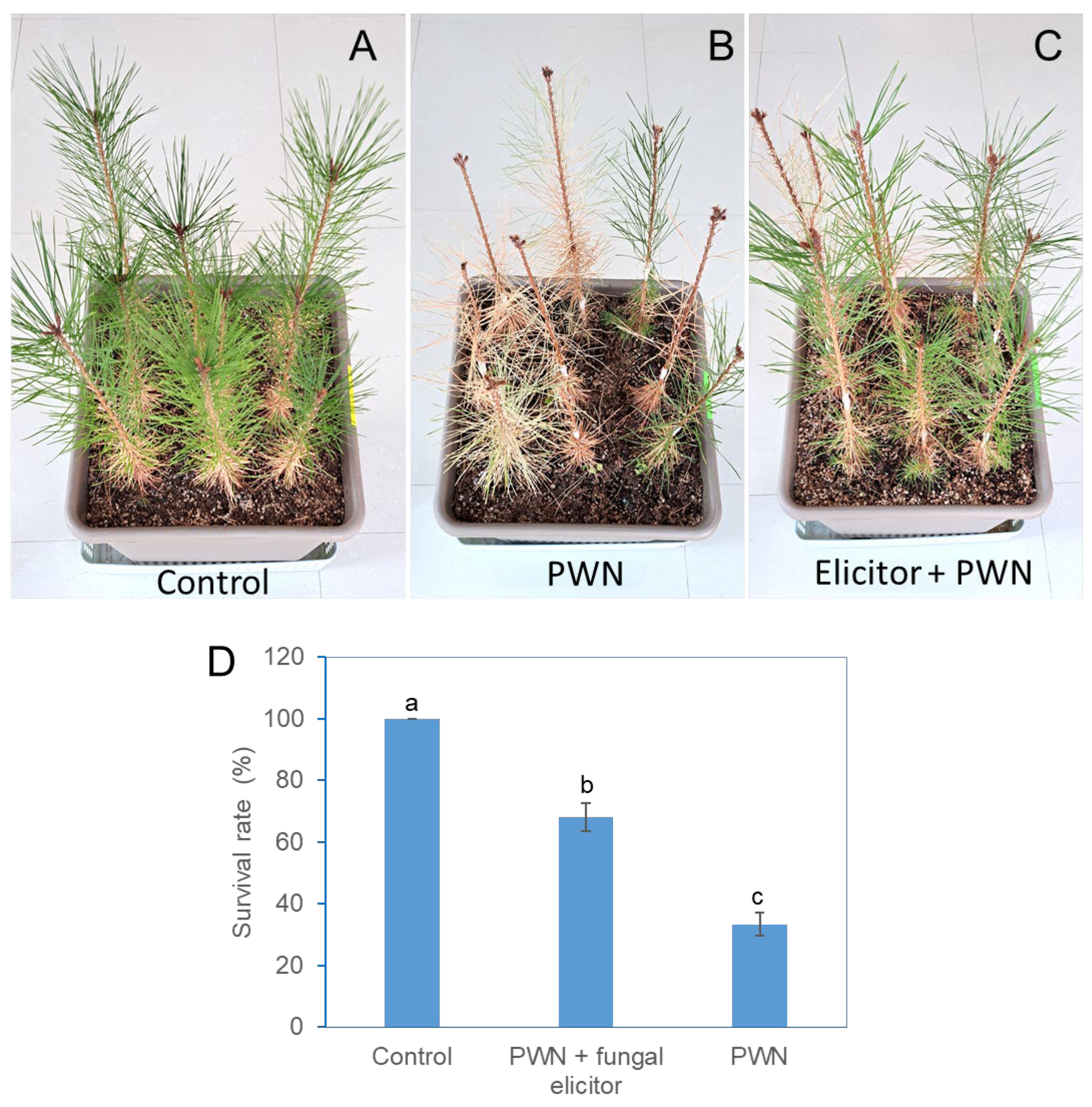

2.3. PWD Resistance of Pine Plants after Soil Drenching Treatment with Fungal Elicitors

To inoculate the PWNs in pine trees, a part of the bark of the pine trunk is cut with a knife, cotton is inserted into the wounded bark, and then, a culture medium containing approximately 500 PWNs is inoculated there. After inoculation, the samples were sealed with parafilm. In the case of pine trees not treated with fungal elicitors as a control group, the bark was wounded in the same way, and the same number of nematodes were inoculated. The progress of PWD was monitored after PWN inoculation, and the survival rate of the pine trees was subsequently examined after 5 months. More than 15 inoculated pine trees were included in each of the control and treatment groups, and 3 repetitions were performed.

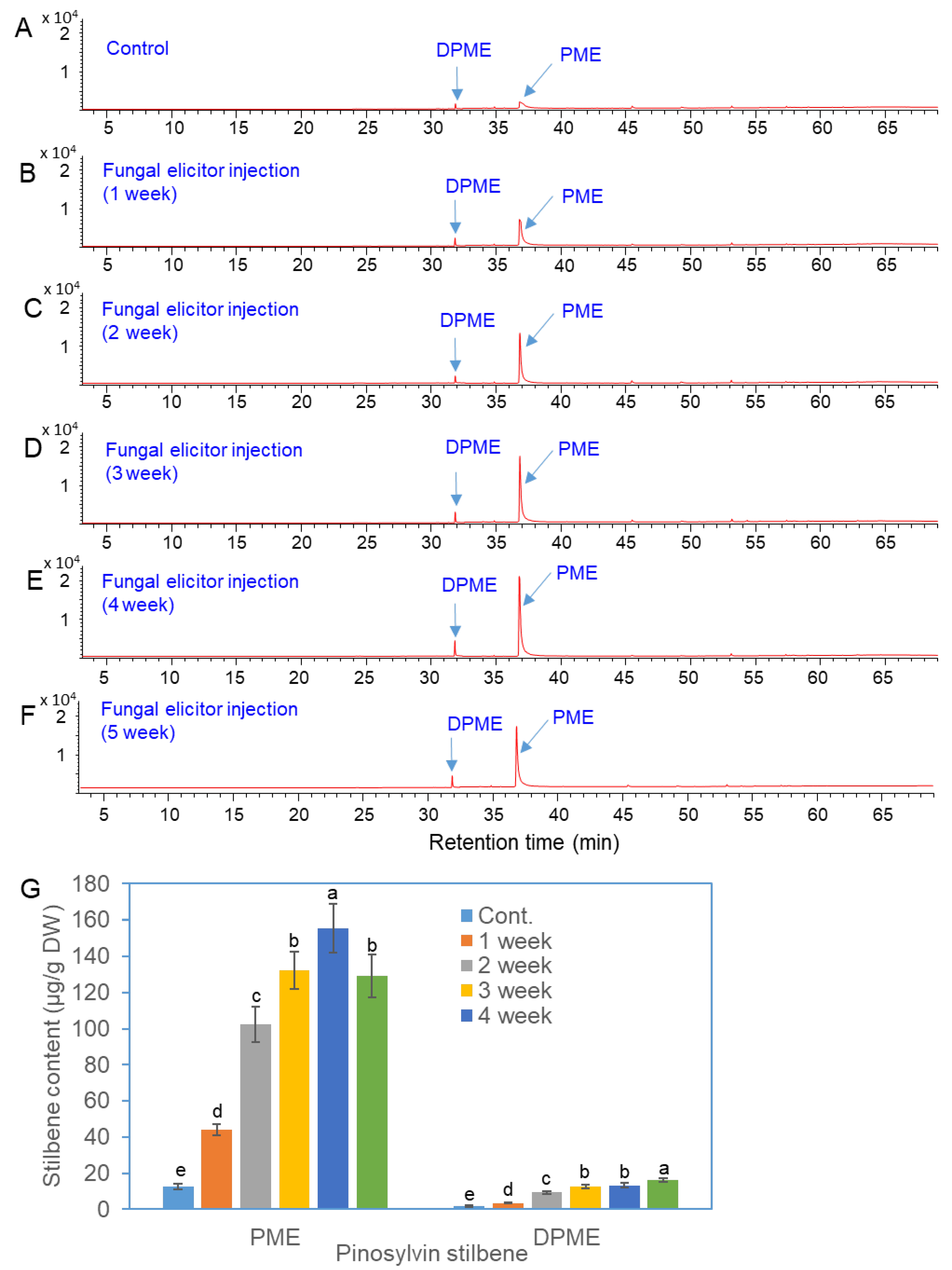

2.4. Trunk Injection of Fungal Elicitors on Pine Trees

The fungal culture medium was diluted by adding water to a concentration of 20% (v/v). Fungal culture medium (20 ml) was injected into the drilled holes of the trunks of 10-year-old Korean red pine trees. As a control, the same amount of PDA medium diluted with water was injected into the trunk. Pine leaves were harvested 1 week, 2 weeks, 3 weeks, and 4 weeks after the fungal elicitor injection was applied to the pine plants, which were subsequently used as materials for analyzing the contents of DPME and PME.

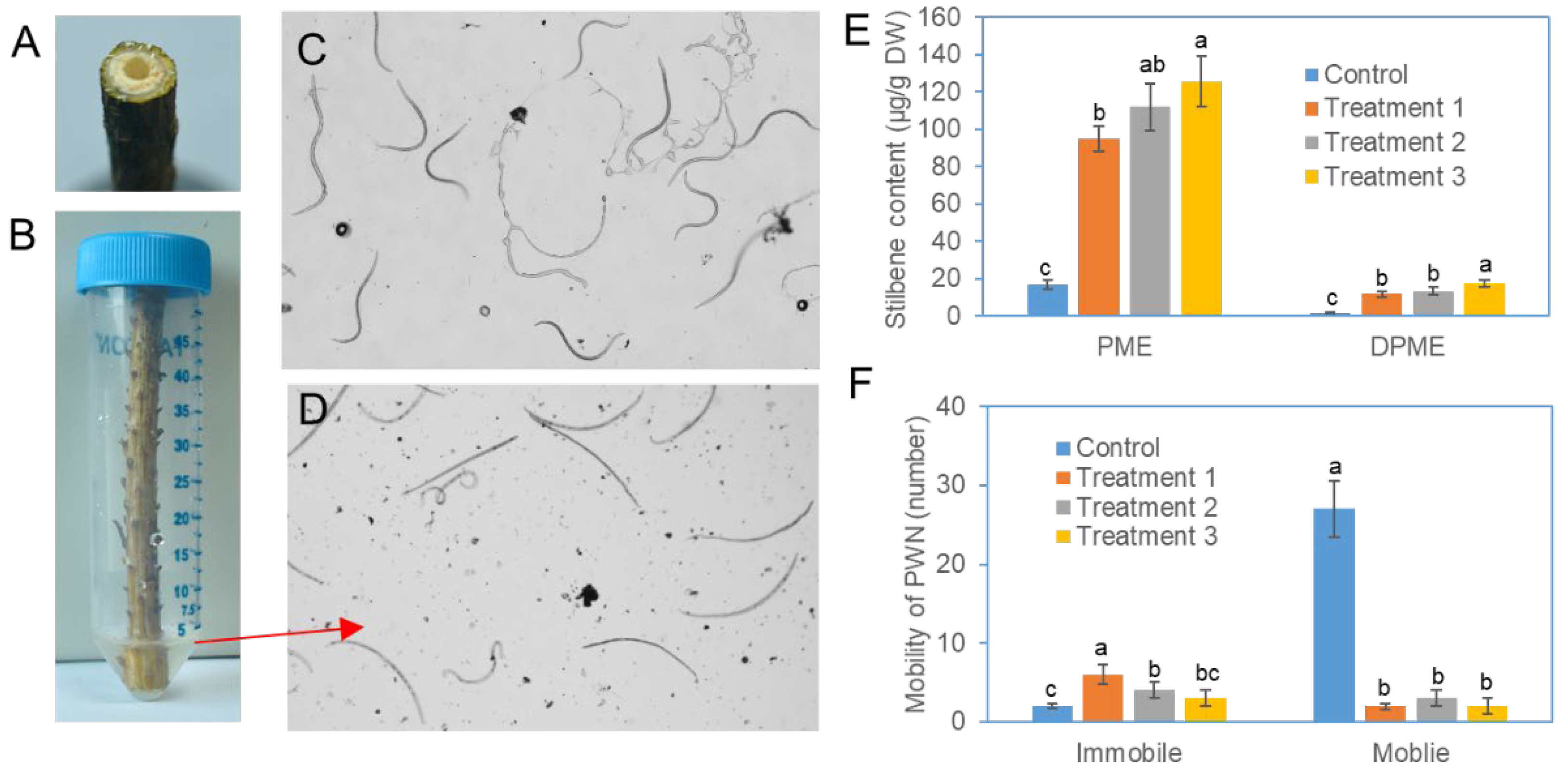

2.5. Investigation of PWN Movement in Branches of P. densiflora Plants after Trunk Injection of Fungal Elicitors

Internodes of control and fungal elicitor-treated pine (Pinus densiflora) plants were cut to 100 mm to make nodal segments, and then, a hole was drilled at the top, approximately 500 PWNs were inoculated there, and the samples were sealed with parafilm. The branch segments were placed into a 50 mL Falcon tube. At this time, 5 mL of water was added to a tube in which the lower parts of the segments were submerged in water. After that, the cap of the falcon tube was closed and erected, and after 24 hours, the number and viability (movement) of PWNs in the water removed from the bottom of the branch segments were determined via optical microscopy. The branch segments were sampled from three independent pine plants, and the analysis of the number and viability of PWNs that were removed from the bottom of branch segments was performed on more than 5 segments per pine plant.

2.6. GC‒MS Analysis

To measure the contents of the DPME and PME compounds via gas chromatography‒mass spectrometry (GC‒MS), the pine leaves were air-dried in an oven at 50 °C. Each sample was pulverized to make a powder, and then 100 mg was weighed, immersed in 100% methanol (1 ml), and sonicated at a frequency of 20 kHz for 30 min at 40 °C. Then, the supernatant obtained by centrifugation (15000 × g for 10 min) was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane to remove impurities. Filtered aliquots were injected into a GC (Agilent 7890A) coupled to an MSD system (Agilent 5975C) equipped with an HP-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.25 mm). The injection temperature was 250 °C, and the column temperature was 70 °C for 4 min, 220 °C at 5 °C min-1, heated to 320 °C at 4 °C min-1, and held at 320 °C for 5 min. The carrier gas was He at a flow rate of 1.2 ml min-1. The interface temperature was 300 °C with split/nonsplit implantation (10:1), the temperature of the ionization chamber was 250 °C, and ionization was performed by electron bombardment at 70 eV. The standard compounds of DPME and PME used for GC‒MS analysis were purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich Co. The experiment was repeated three times.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The quantitative data are expressed as the means ± standard errors (SEs). All the statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (SPSS Science, Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical differences among means were calculated via one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s post hoc test.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether fungal elicitor treatment affects PME and DPME accumulation in Korean red pine trees and whether this change is associated with resistance to PWD. The fungal elicitor used was the medium filtrate after

P. chrysogenum liquid culture, which has already been shown to strongly increase the synthesis of PME and DPME in Korean pine cell cultures through the treatment of the medium filtrate of

P. chrysogenum [

16]. Among the fungal elicitors derived from 7 different fungal species,

Penicillium, Trichoderma and

Aspergillus, a fungal elicitor prepared from

P. chrysogenum was the most effective elicitor for increasing the production of DPME and PME in

P. strobus cells [

30]. The fungal elicitors were either inoculated into the soil where the pine trees were planted or directly injected into the trunks of the pine trees and then analyzed for changes in the contents of PME and DPME for 4 weeks. The results revealed that both soil drenching and tree injection of the fungal elicitor significantly increased the accumulation of PME and DPME. PME is highly toxic to PWNs, resulting in 100% killing of PWNs in 24 hours at concentrations as low as 10 ppm according to an in vitro assay [

25]. Therefore, we speculated that increasing PME by fungal elicitor treatment of Korean red pine, which is highly susceptible to PWD, may slow the progression of PWD caused by PME toxicity. To test this hypothesis, we inoculated PWNs into Korean Red pine trees after two weeks of fungal elicitor soil treatment and monitored the development of PWD symptoms for five months. The results revealed that 78% of the fungal elicitor-untreated pine plants presented symptoms of PWD, whereas only 33% of the pine trees pretreated with the elicitor presented symptoms of PWD, confirming that pretreatment with the fungal elicitor was highly effective in reducing PWD. This result supports our previous hypothesis that fungal elicitor treatment of

P. densiflora plants results in increased pinosylvin stilbenoid accumulation, which may confer toxicity to PWNs.

Since trunk injection of fungal elicitors into pine trees resulted in a significant increase in the PME and DPME contents, we investigated the effects of trunk elicitor injection of fungal elicitors on the motility and activity of PWNs after PWN infection. Inoculation of the PWNs was performed on the top of the internodal segments of branches of 10-year-old pine plants after two weeks of trunk injection of fungal cultures. We examined the migration and mobility of nematodes to the bottom of branches from the top. The results revealed that the movement of PWNs downward to the branch was significantly inhibited because the number of nematodes was significantly reduced in branches pretreated with the fungal elicitor. Moreover, the movement of PWNs that moved from the branches was highly weakened, and these PWNs began to lose movement within 24 hrs. These results suggest that the increased accumulation of PME and DPME in pine trees after injection of fungal cultures may directly affect the movement of inoculated PWNs. Thus, trunk injection of fungal elicitors has the potential to provide a protocol for controlling PWD disease in P. densiflora plants.

Currently, aerial spraying and trunk injection of abamectin-based insecticides constitute a general way to eliminate PWN

vectors, pine sawyer beetles [

19], and control PWD in pine plants [

12,

24]. However, it is widely believed that these methods cause severe damage to the biological ecosystem of forests [

15]. Therefore, many researchers are actively developing eco-friendly control technologies as alternatives to chemical pesticide applications [

3]. Among them, representative control substances for PWD in pine plants often utilize microorganisms (fungi, bacteria, and actinomycetes) [

3]. On the other hand, chitosan has been reported to have a preventive effect on PWD when it is sprayed on pine trees [

21]. Treatments with methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid, and methyl salicylate have also been reported to be protective against PWNs [

13,

18]. Although neither of these studies confirmed the association between PWN protection and pinosylvin stilbenoid accumulation, it is possible that elicitor treatment may be associated with pinosylvin stilbenoid synthesis.

In

P. strobus, which is highly resistant to PWD, pinosylvin stilbenoid (PME and DPME) accumulation is highly increased upon PWN infection. However, both Korean red pine (Korean red pine (

P. densiflora) and Korean pine (

P. koraiensis), which are susceptible to PWD, do not exhibit changes in these substances upon PWN infection [

10]. Thus, the ability of PWNs to accumulate pinosylvin stilbenoids upon infection is likely related to PWD resistance in

P. strobus plants because pinosylvin stilbenoids (PME and DPME) are highly toxic to PWNs [

10,

25]. Pinosylvin stilbenoids are produced from the precursor phenylalanine to PME or DPME [

4]. Transcriptional regulators play key roles in plant defense mechanisms [

2]. In a previously reported study, the lack of an increase in pinosylvin stilbenoids upon PWN infection in PWD-susceptible Korean Red pine and Korean pine [

10] was attributed to a defect in the role of transcriptional regulators in controlling the synthesis of pinosylvin stilbenoids. Therefore, the differences in pinosylvin stilbenoid accumulation between strobe pine and Korean pine upon PWN infection are likely due to differences in the role of transcriptional regulators that control the synthesis of these substances. In recent years, much progress has been made in understanding the mechanisms of disease resistance associated with plant disease immunity [

27]. In the case of pine plants, terpenoids, flavonoids, and stilbenoids have been interpreted as the main secondary metabolites associated with immunity in PWD resistance [

20]. Therefore, analyzing the role of transcriptional regulators that control the synthesis of these compounds in pine tree species may provide important clues for understanding PWD immunity and for their use in breeding for the future development of PWD-resistant pine trees.