Submitted:

24 September 2024

Posted:

25 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

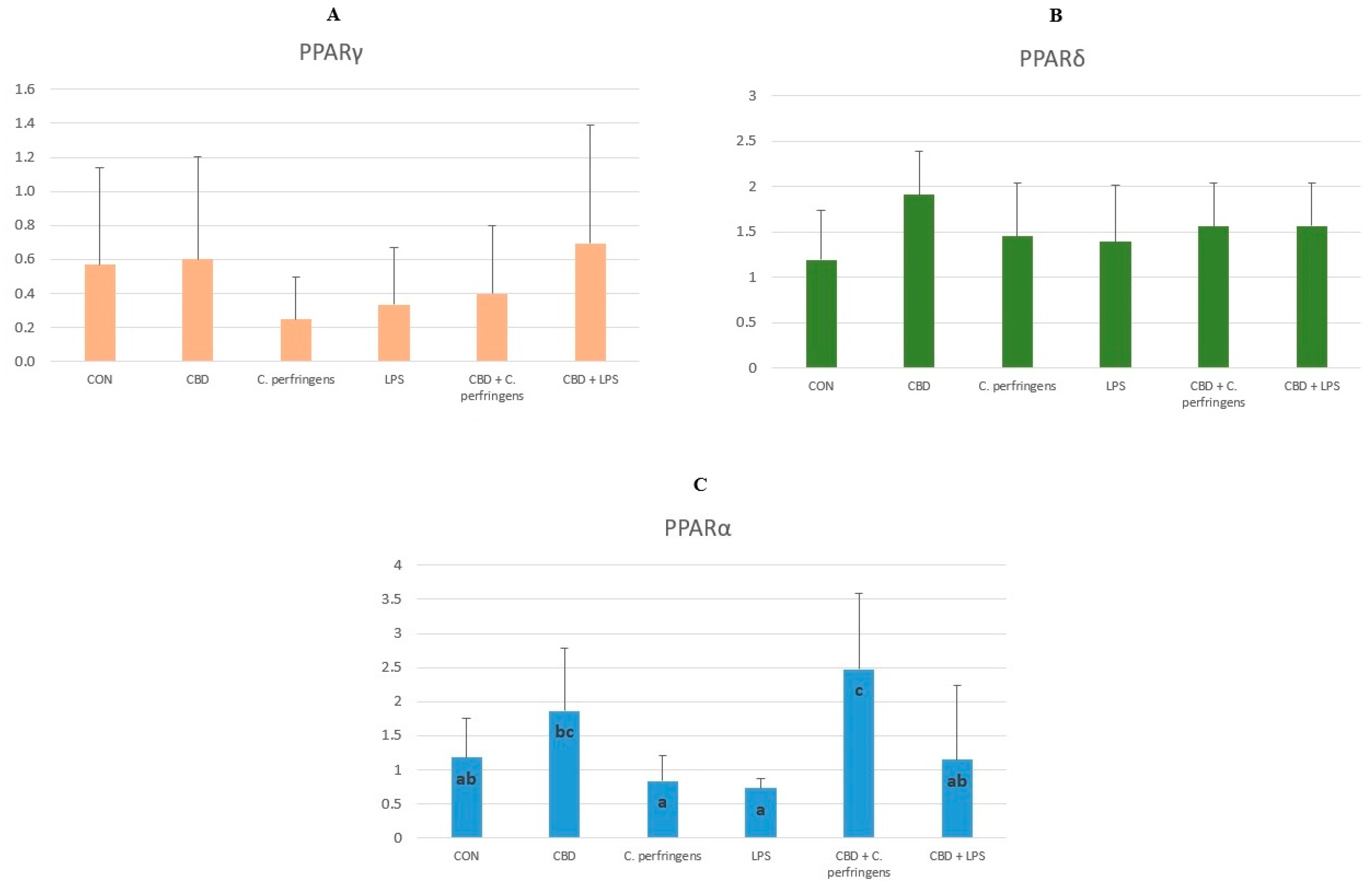

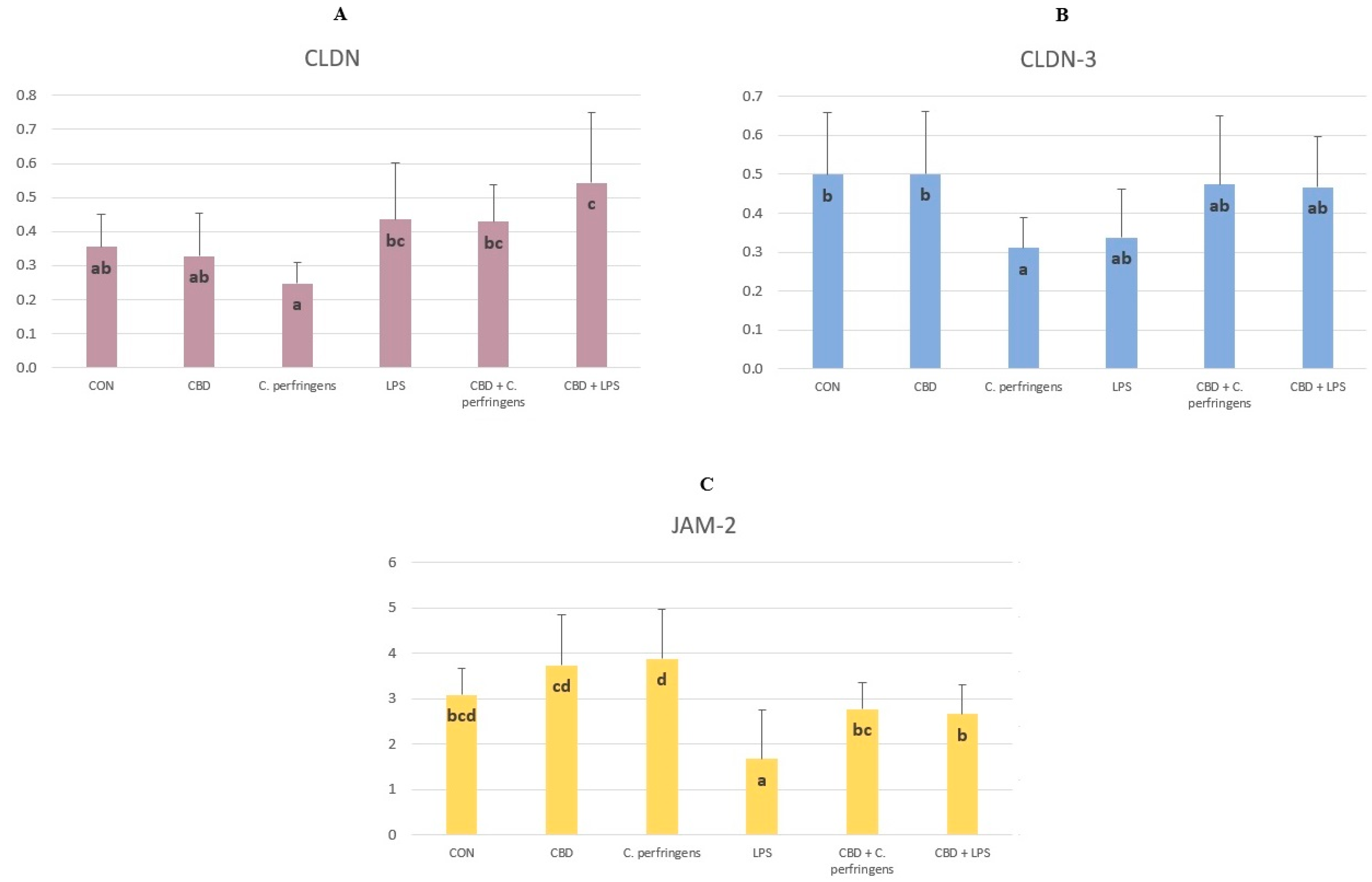

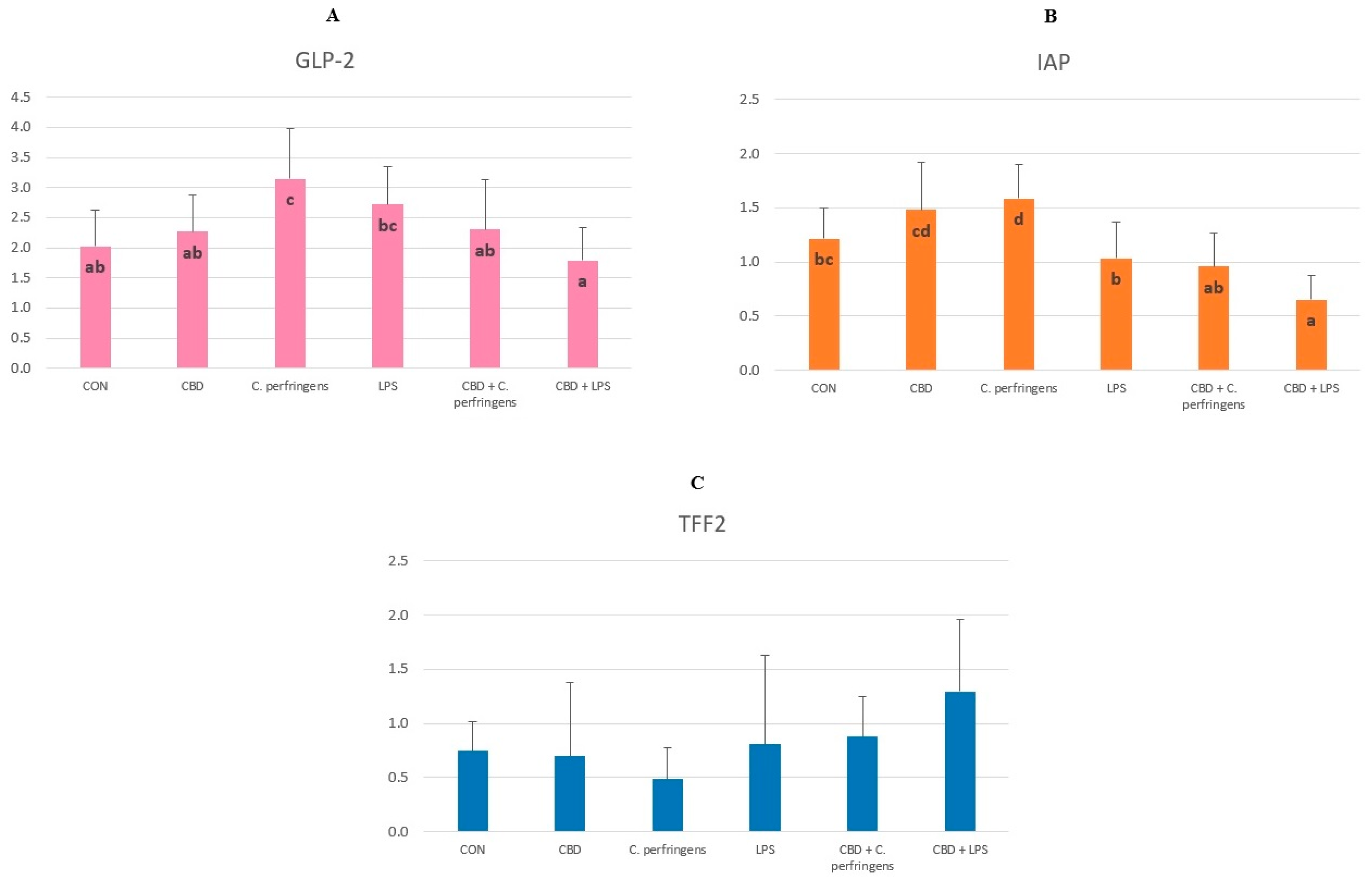

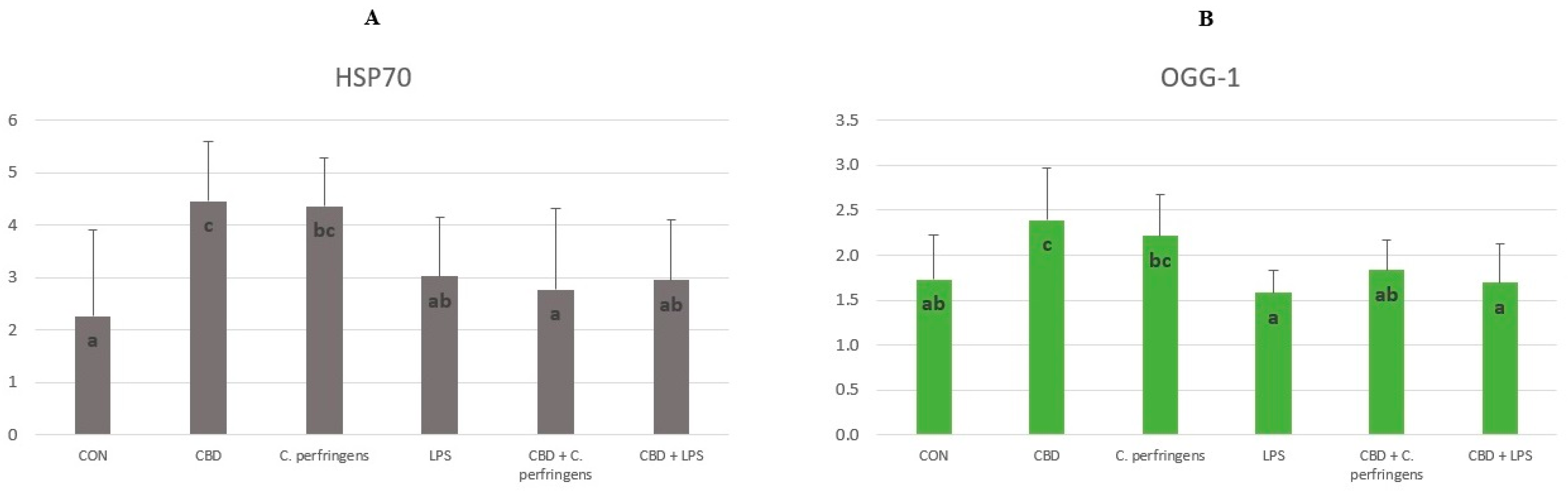

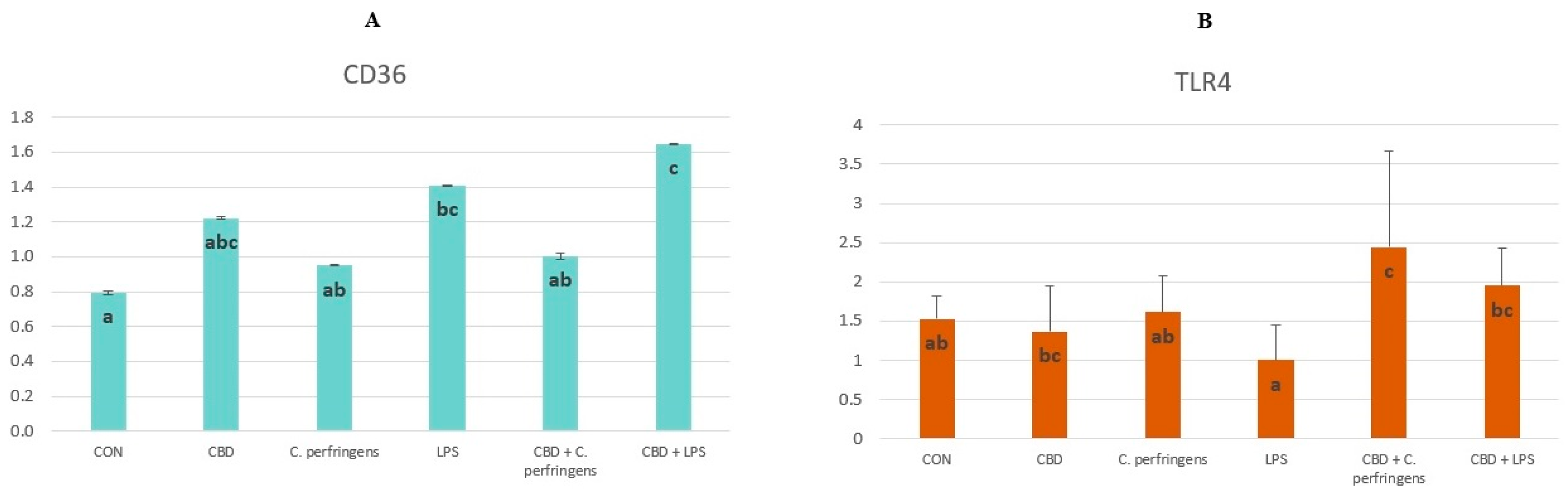

2.1. CBD-, LPS- and C. Perfringens-Mediated Changes in the Transcript Levels of PPARs and Selected Genes

2.2. Correlations between mRNA Expression Levels of PPARs and Selected Genes

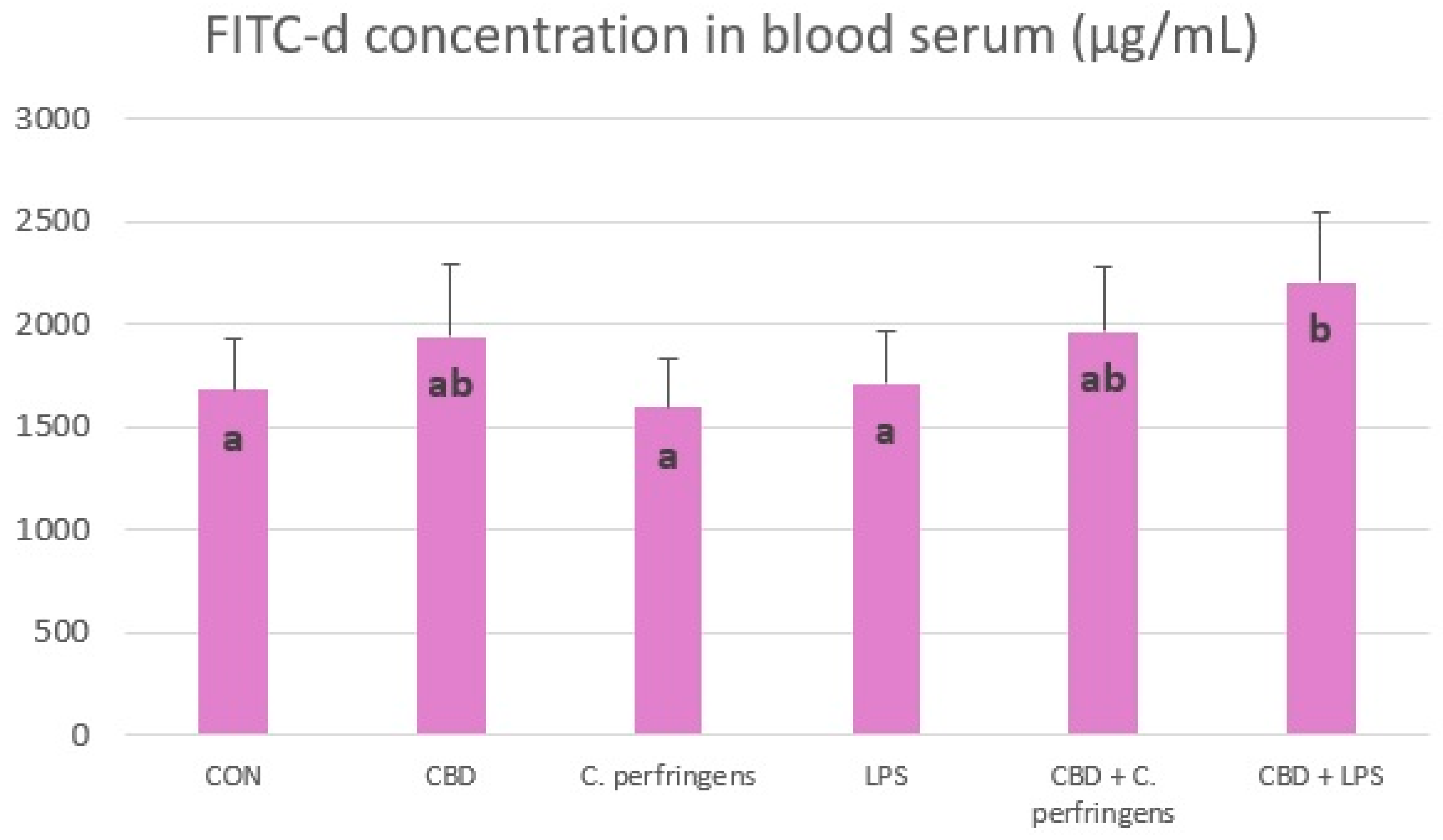

2.3. Effect of CBD on FITC-d Concentration in Blood of Challenged and Non-Challenged Birds

2.4. Correlations between Gene Expression and FITC-d Concentration

| Gene | FITC-d | |

|---|---|---|

| r | p-value | |

| HSP70 | -0.105 | 0.500 |

| TFF2 | 0.213 | 0.155 |

| PPARγ | -0.083 | 0.590 |

| PPARα | -0.275 | 0.032* |

| PPARδ | 0.005 | 0.974 |

| P53 | 0.002 | 0.992 |

| ZO-1 | 0.206 | 0.175 |

| ZO-2 | 0.06 | 0.972 |

| TLR4 | 0.311 | 0.036* |

| OCLN | 0.255 | 0.087 |

| MUC-5B | 0.279 | 0.062 |

| MUC-2 | 0.147 | 0.330 |

| JAM-2 | -0.150 | 0.338 |

| IAP | -0.313 | 0.032* |

| E-cad | -0.055 | 0.719 |

| CLDN-3 | 0.189 | 0.215 |

| GLP-2 | -0.269 | 0.071 |

| OGG-1 | -0.027 | 0.864 |

| GPX-1 | -0.141 | 0.398 |

| CLDN-1 | -0.083 | 0.591 |

| CD36 | 0.301 | 0.040* |

| CLDN | 0.318 | 0.038* |

| CNR1 | 0.258 | 0.083 |

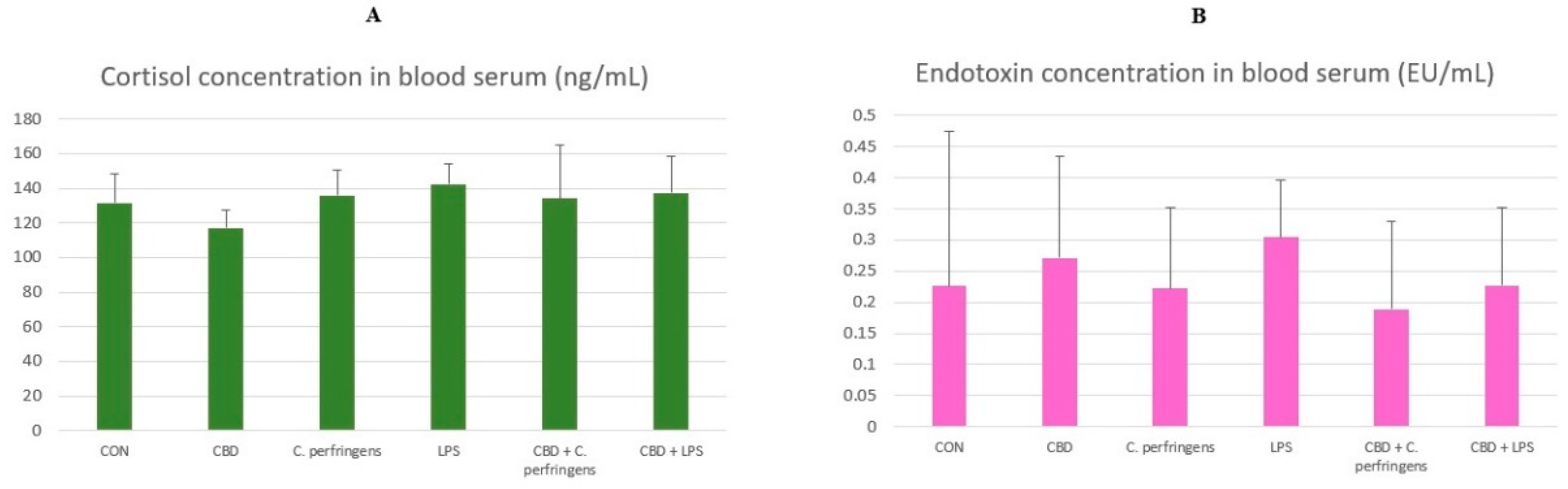

2.5. The Effect of CBD on Cortisol and Endotoxin Concentration in the Blood

2.6. Correlations between Gene Expression and Cortisol Concentration

| Gene | Cortisol | |

|---|---|---|

| r | p-value | |

| HSP70 | -0.067 | 0.664 |

| TFF2 | 0.104 | 0.488 |

| PPARγ | -0.154 | 0.308 |

| PPARα | -0.105 | 0.478 |

| PPARδ | -0.21 | 0.157 |

| P53 | 0.186 | 0.217 |

| ZO-1 | -0.087 | 0.566 |

| ZO-2 | -0.024 | 0.881 |

| TLR4 | -0.047 | 0.754 |

| OCLN | -0.085 | 0.571 |

| MUC-5B | -0.24 | 0.104 |

| MUC-2 | -0.105 | 0.481 |

| JAM-2 | -0.301 | 0.047* |

| IAP | -0.192 | 0.190 |

| E-cad | -0.044 | 0.771 |

| CLDN-3 | -0.053 | 0.726 |

| GLP-2 | -0.146 | 0.327 |

| OGG-1 | -0.218 | 0.151 |

| GPX-1 | -0.053 | 0.748 |

| CLDN-1 | -0.044 | 0.775 |

| CD36 | 0.1 | 0.498 |

| CLDN | 0.186 | 0.226 |

| CNR1 | -0.305 | 0.037* |

2.7. Correlations between Gene Expression and Endotoxin Concentration

| Gene | Endotoxin | |

|---|---|---|

| r | p-value | |

| HSP70 | -0.234 | 0.131 |

| TFF2 | 0.045 | 0.769 |

| PPARγ | -0.154 | 0.308 |

| PPARα | 0.099 | 0.511 |

| PPARδ | -0.133 | 0.384 |

| P53 | 0.001 | 1.000 |

| ZO-1 | 0.053 | 0.731 |

| ZO-2 | -0.027 | 0.867 |

| TLR4 | 0.07 | 0.646 |

| OCLN | 0.043 | 0.780 |

| MUC-5B | 0.066 | 0.667 |

| MUC-2 | 0.042 | 0.783 |

| JAM-2 | -0.203 | 0.198 |

| IAP | -0.092 | 0.546 |

| E-cad | -0.152 | 0.325 |

| CLDN-3 | 0.117 | 0.451 |

| GLP-2 | -0.255 | 0.091 |

| OGG-1 | 0.21 | 0.177 |

| GPX-1 | -0.093 | 0.586 |

| CLDN-1 | -0.344 | 0.022* |

| CD36 | -0.325 | 0.028* |

| CLDN | -0.076 | 0.631 |

| CNR1 | 0.097 | 0.525 |

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

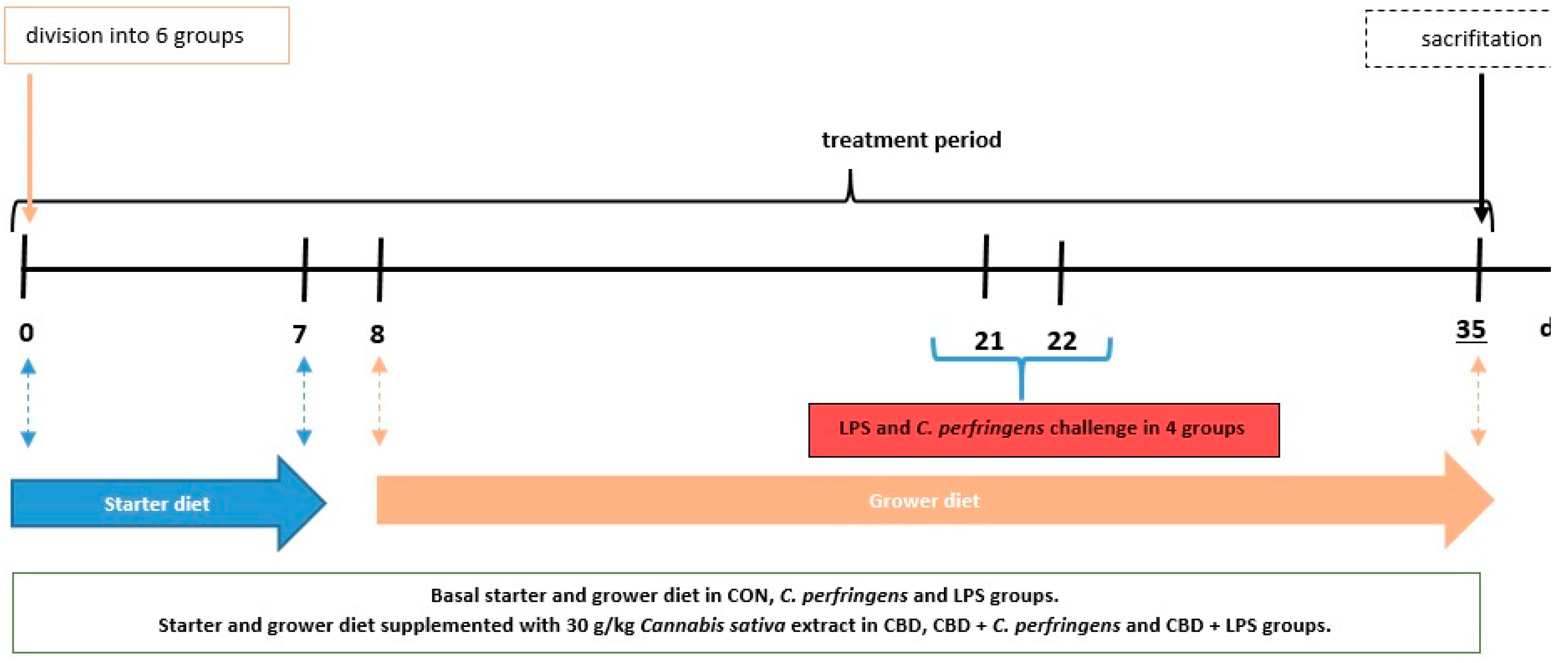

4.1. Chicken Experiment, Diets and Applied Experimental Challenges

4.1.1. Chemical Composition of Cannabis Extract

4.1.2. Chicken Experiment and Diets

4.1.3. Applied Experimental Challenges and Sampling Procedure

4.2. Real-Time PCR

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5’-3’) | Product size (nt) | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTB | Forward | CGGACTGTTACCAACACCCA | 115 | NM_205518 |

| Reverse | TCCTGAGTCAAGCGCCAAAA | |||

| GADPH | Forward | GCACGCCATCACTATCTT | 82 | NM_204305 |

| Reverse | GGACTCCACAACATACTCAG | |||

| HSP70 | Forward | GGCAATAAGCGAGCAGTG | 146 | NM_001006685 |

| Reverse | CGAGTGATGGAGGTGTAGAA | |||

| TFF2 | Forward | ACTACCCTACTGAGAGAACAAA | 143 | XM_416743 |

| Reverse | CTGAAGAACCTGCTCAACTG | |||

| PPARγ | Forward | GACCTTAATTGTCGCATCCA | 130 | XM_025154399 |

| Reverse | TCTCCTTCTCCGCTTGTG | |||

| PPARα | Forward | CGGAGTACATGCTTGTGAAGG | 198 | XM_025150258.2 |

| Reverse | TCAGACCTTGGCATTCGTCC | |||

| PPARδ | Forward | TACACCGACCTTTCGCAGAG | 108 | NM_204728.2 |

| Reverse | TCCACAGACTCTGCACTCCA | |||

| P53 | Forward | AGGTGGGCTCTGACTGTA | 98 | NM_001407269.1 |

| Reverse | TGTAAGGATGGTGAGGATGG | |||

| ZO-1 | Forward | TCGCTGGTGGCAATGATGTT | 89 | XM_413773 |

| Reverse | TTGGTCTCCTTCCTCTAATCCTTCTT | |||

| ZO-2 | Forward | CCTCCTACCAGACCTTACC | 153 | NM_204918 |

| Reverse | CCAGCAAGCCTACAGTTC | |||

| TLR4 | Forward | CAAGCACCAGATAGCAACA | 146 | FJ915527 |

| Reverse | CACTACACTACTGACAGAACAC | |||

| OCLN | Forward | ATCAACGACCGCCTCAAT | 86 | XM_046904540.1 |

| Reverse | TACTCCTCTGCCACATCCT | |||

| MUC-5B | Forward | TGACTGTACCTGCTGCCAAG | 145 | XM_046919157.1 |

| Reverse | TGCTTCAAGGGTTTGTGGGT | |||

| MUC-2 | Forward | ATCGTGAGGAATGTGAGAAGTT | 140 | XM_421035 |

| Reverse | GCAGAGGCAGAAGGAGTC | |||

| JAM-2 | Forward | TCCTCCCACTACTCCAATATG | 134 | XM_026849998 |

| Reverse | ACTGCCTGTTCCTGTCTT | |||

| IAP | Forward | CAGGAGCAGCACTATGTTG | 199 | XM_015291489 |

| Reverse | CTAGAGGAGGGCTTGGTAG | |||

| E-cad | Forward | GGATGGCGTCGTCTCAACA | 75 | NM_001039258 |

| Reverse | TCCTGTGCGTAGATGGTGAAG | |||

| CLDN-3 | Forward | CGTCATCTTCCTGCTCTC | 87 | NM_204202 |

| Reverse | AGCGGGTTGTAGAAATCC | |||

| GLP-2 | Forward | TGTGTTCAGACGGTAAGG | 127 | NM_001163248 |

| Reverse | TCATCCAGTGCCATCTTC | |||

| OGG-1 | Forward | GAGTCTGAGTCTGGAGCA | 79 | XM_046926490.1 |

| Reverse | CTTCCTGGCTTGGCTTATC | |||

| GPX-1 | Forward | AGTAAAGGAAAGCCCGCACC | 157 | NM_001277853.3 |

| Reverse | GCTGTTCCCCCAACCATTTC | |||

| CLND-1 | Forward | GGTGAAGAAGATGCGGATG | 99 | NM_001013611 |

| Reverse | GCCACTCTGTTGCCATAC | |||

| CD36 | Forward | AGACCAGTAAGACCGTGAAG | 134 | NM_001030731 |

| Reverse | TAGGACTCCAGCCAGTGT | |||

| Tac1 | Forward | CCGATGACCTCAGCTACTGG | 99 | XM_004939318.3 |

| Reverse | GTCTCCTTGCCATCCTCTGC | |||

| CNR1 | Forward | GTCACCAGCGTCCTCTTG | 127 | NM_001038652 |

| Reverse | CTCCGTACTCTGAATGATTATGC | |||

| CNR2 | Forward | AACTGAATGAGGCTCTTCCA | 194 | XM_025143151 |

| Reverse | GCTCTTGTCACTTACTGCTG |

4.3. Determination of the FITC-D Concentration in Blood Serum

4.4. Determination of the Cortisol in Blood Serum

4.5. Determination of Endotoxin in Blood Serum

4.6. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); European Food Safiety Authority (EFSA); European Medicines Agency (EMA). Antimicrobial consumption and resistance in bacteria from humans and food-producing animals. EFSA J. 2024, 22(2), e8589. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); European Food Safiety Authority (EFSA); European Medicines Agency (EMA). ECDC/EFSA/EMA second joint report on the integrated analysis of the consumption of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from humans and food-producing animals – Joint Interagency Antimicrobial Consumption and Resistance Analysis (JIACRA) Report. EFSA J. 2017, 15, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldhusdal, M.; Løvland, A. The economical impact of Clostridium perfringens is greater than anticipated. Worlds Poult. 2000, 16, 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Van Immerseel, F.; De Buck, J.; Pasmans, F.; Huyghebaert, G.; Haesebrouck, F.; Ducatelle, R. Clostridium perfringens in poultry: an emerging threat for animal and public health. Avian Pathol. 2004, 33, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McReynolds, J.L.; Byrd, J.A.; Anderson, R.C.; Moore, R.W.; Edrington, T.S.; Genovese, K.J.; Poole, T.L.; Kubena, L.F.; Nisbet, D.J. Evaluation of immunosuppressants and dietary mechanisms in an experimental disease model for necrotic enteritis. Poult Sci. 2004, 83(12), 1948–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellata, M. Human and avian extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli: infections, zoonotic risks, and antibiotic resistance trends. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2013, 10(11), 916–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, T.A.; Johnson, J.R. Medical and economic impact of extraintestinal infections due to Escherichia coli: focus on an increasingly important endemic problem. Microbes Infect. 2003, 5, 449–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojadoost, B.; Vince, A.R.; Prescott, J.F. The successful experimental induction of necrotic enteritis in chickens by Clostridium perfringens: a critical review. Vet. Res. 2012, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewers, C.; Antao, E.M.; Diehl, I.; Philipp, H.C.; Wieler, L.H. Intestine and environment of the chicken as reservoirs for extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strains with zoonotic potential. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75(1), 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, L.; Garenaux, A.; Harel, J.; Boulianne, M.; Nadeau, E.; Dozois, C.M. Escherichia coli from animal reservoirs as a potential source of human extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli. E. coli. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 62, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, L.J.; Kogut, M.H. Gut immunity: its development and reasons and opportunities for modulation in monogastric production animals. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2018, 19(1), 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klasing, K.C. Nutritional modulation of resistance to infectious diseases. Poult. Sci. 1998, 77(8), 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Eicher, S.D.; Applegate, T.J. Development of intestinal mucin 2, IgA, and polymeric Ig receptor expressions in broiler chickens and Pekin ducks. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94(2), 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, E.; Droessler, L.; Amasheh, S. Cannabidiol attenuates inflammatory impairment of intestinal cells expanding biomaterial-based therapeutic approaches. Materials Today Bio 2023, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, S.; Jarocka-Karpowicz, I.; Skrzydlewska, E. Antioxidative and anti-inflammatory propertied of cannabidiol. Antioxidants 2020, 9(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamoruni, A.; Lee, A.C.; Wright, K.L.; Larvin, M.; O’Sullivan, S.E. Pharmacological effects of cannabinoids on the Caco-2 cell culture model of intestinal permeability. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010, 335(1), 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Petrocellis, L.; Ligresti, A.; Moriello, A.S.; Moriello, A.S.; Allara, M.; Bisogno, T.; Petrosino, S.; Stott, C.G.; Di Marzo, V. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1479–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marzo, V.; Bifulco, M.; Petrocellis, L. The endocannabinoid system and its therapeutic exploitation. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2004, 3, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Posadas, R.; Stürz, M.; Atreya, I.; Neurath, M. F.; Britzen-Laurent, N. 2017. Interplay of GTPases and Cytoskeleton in Cellular Barrier Defects during Gut inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczka, P.; Szkopek, D.; Kinsner, M.; Fotschki, B.; Juśkiewicz, J.; Banach, J. Cannabis-derived cannabidiol and nanoselenium improve gut barrier function and affect bacterial enzyme activity in chickens subjected to C. perfringens challenge. Vet. Res. 2020, 51, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yekhtin, Z.; Khuja, I.; Meiri, D.; Or, R.; Almogi-Hazan, O. Differential effects of D9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)- and cannabidiol (CBD)-based cannabinoid treatments on macrophage immune function in vitro and on gastrointestinal inflammation in a murine model. Biomedicines 2022, 10(8), 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruhaak, L.R.; Felth, J.; Karlsson, P.C.; Rafter, J.J.; Verpoorte, R.; Bohlin, L. Evaluation of the cyclooxygenase inhibiting effects of six major cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 34(5), 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlost, J.; Bryk, M.; Starowicz, K. Cannabidiol for pain treatment: Focus on pharmacology and mechanism of action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21(22), 8870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosropoor, S.; Alavi, M.; Etemad, L.; Roohbakhsh, A. Cannabidiol goes nucler: The role of PPAR γ. Phytomedicine 2023, 114, 154771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, S.E. An update on PPAR activation by cannabinoids. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173(12), 1899–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Waltenberger, B.; Pferschy-Wenzing, E.; Blunder, M.; Liu, X.; Malainer, C.; Blazevic, T.; Schwaiger, S.; Rollinger, J.M.; Heiss, E.H.; Schuster, D.; Kopp, B.; Bauer, R.; Stuppner, H.; Dirsch, V.M.; Atanasov, A.G. Natural product agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ): a review. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 92, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, I.; Goel, H.; Kotwani, A. Implications of endogenous PPAR-gamma ligand, 15-Deoxy-Delta-12,14-prostaglandin J2, in diabetic retinopathy. Life Sci. 2016, 153, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schild, R.L.; Schaiff, W.T.; Carlson, M.G.; Cronbach, E.J.; Nelson, D.M.; Sadovsky, Y. The activity of PPAR gamma in primary human trophoblasts is enhanced by oxidized lipids. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87(3), 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygiel-Gorniak, B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and their ligands: nutritional and clinical implications—a review. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajas, L.; Auboeuf, D.; Raspe, E.; Schoonjans, K.; Lefebvre, A.; Saladin, R.; Najib, J.; Laville, M.; Fruchart, J.; Deeb, S.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Flier, J.; Briggs, M.R.; Staels, B.; Vidal, H.; Auwerx, J. The organization, promoter analysis, and expression of the human PPARgamma gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272(30), 18779–18789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbrecht, A.; Chen, Y.; Cullinan, C.A.; Hayes, N.; Leibowitz, M.D.; Moller, D.E.; Berger, J. Molecular cloning, expression and characterization of human peroxisome proliferator activated receptors gamma 1 and gamma 2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 224(2), 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogasawara, N.; Kojima, T.; Ohkuni, T.; Koizumi, J.; Kamekura, R.; Masaki, T.; Murata, M.; Tanaka, S.; Fuchimoto, J. , Himi, T.; Sawada, N. PPARgamma agonists upregulate the barrier function of tight junctions via a PKC pathway in human nasal epithelial cells. Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 61(6), 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Wu, T.; Tsai, B.; Hung, Y.; Lin, H.; Tsai, Y., Ko; Tsai, P. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ as the gatekeeper of tight junction in Clostridioides difficile infection. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Singh, S.; Potula, R; Persidsky, Y.; Kanmogne, G.D. Dysregulation of claudin-5 in HIV-induced interstitial pneumonitis and lung vascular injury. Protective role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2014, 190, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, Y.P.; Ko, W.C.; Chou, P.H.; Chen, Y.H.; Lin, H.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Tsai, H.W. , Lee, J.C.; Tsai, P.J. Proton-pump inhibitor exposure aggravates Clostridium difficile-associated colitis: evidence from a mouse model. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 212(4), 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granja, A.G.; Carillo-Salinas, F.; Pagani, A.; Gómez-Cañas, M.; Negri, R.; Navarrete, C.; Mecha, M.; Mestre, L.; Fiebich, B.L.; Cantarero, I.; Calzado, M.A.; Bellido, M.L.; Fernandez-Ruiz, J.F.; Appendino, G.; Guaza, C.; Muñoz, E. A cannabigerol quinone alleviates neuroinflammation in a chronic model of multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2021, 7, 1002–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, V.L.; Singh, U.P.; Nagarkatti, P.S.; Nagarkatti, M. Critical Role of Mast Cells and Peroxisome Proliferator–Activated Receptor γ in the Induction of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells by Marijuana Cannabidiol In Vivo. J. Immunol. 2015, 194(11), 5211–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, H. Role of PPAR-gamma in inflammation. Prospects for therapeutic intervention by food components. Mutat. Res. 2009, 669, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Fan, M.; An, C.; Ni, F.; Huang, W.; Luo, J. A narrative review of molecular mechanism and therapeutic effect of cannabidiol (CBD). BCPT 2022, 130(4), 130–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahi, S.; Bobak, Ł.; Opaliński, S. Hemp in Animal Diets—Cannabidiol. Animals 2022, 12, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinetti, G.; Fruchart, J.C.; Staels, B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and inflammation: from basic science to clinical applications. Int. J. Obes. 2003, 27(3), S41–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, H.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.G.; Gu, Z.L. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma gene in various chicken tissues. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2005, 28(1), 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, R.K.; Shanmugasundaram, R.; Klasing, K.C. Effects of dietary lutein and PUFA on PPAR and RXR isomer expression in chickens during an inflammatory response. CBPA 2010, 157(3), 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, G. Essential fatty acids and early life programming in meat-type birds. J. World’s Poult. Sci. 2011, 67, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.A. PPARγ Physiology and Pathology in Gastrointestinal Epithelial Cells. Molecules and Cells 2007, 24(2), 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, D.; Esposito, G.; Cirillo, C.; Cipriano, M.; De Winter, B.Y.; Scuderi, C.; Sarnelli, G.; Cuomo, R.; Steardo, L.; De Man, J.G. , Iuvone, T. Cannabidiol reduces intestinal inflammation throigh the control of neuroimmune axis. PLoS ONE 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, M.J.; Choi, S.W.; Choi, Y.S.; Lee, H.; Park, M.Y.; Whang, K.Y. Effects of sophorolipid on growth performance, organ characteristics, lipid digestion markers, and gut functionality and integrity in broiler chickens. Animals 2022, 12(5), 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries-Craft, K.A.; Meyer, M.M.; Lindblom, S.C.; Kerr, B.J.; Bobeck, E.A. Lipid source and peroxidation status alter immune cell recruitment in broiler chicken ileum. J. Nutr. 2021, 151(1), 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib-Naseri, K.; de Las Heras-Saldana, S.; Kheravii, S.; Qin, L.; Wang, J.; Wu, S.B. Necrotic enteritis challenge regulates peroxisome proliferator-1 activated receptors signaling and β-oxidation pathways in broiler chickens. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7(1), 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougarne, N.; Weyers, B.; Desmet, S.J.; Deckers, J.; Ray, D.W.; Staels, B.; De Bosscher, K. Molecular Actions of PPARα in Lipid Metabolism and Inflammation, Endocr. Rev. 2018, 39(5), 760–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, A.; Rathnayake, S.S.; Stroud, R.M. Structural basis for Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin targeting of claudins at tight junctions in mammalian gut. PNAS 2021, 118(15), e2024651118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebnet, K.; Suzuki, A.; Ohno, S.; Vestweber, D. Junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs): more molecules with dual functions? J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117(1), 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, W.A.; Hess, C.; Hess, M. Enteric pathogens and their toxin-induced disruption of the intestinal barrier through alteration of tight junctions in chickens. Toxins 2017, 9(2), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawley, J.; Gourlay, D. Intestinal alkaline phosphatase: a summary of its role in clinical disease. J. Surg. Res. 2015, 202(1), 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Possemiers, S.; Van de Wiele, T.; Guiot, Y.; Everard, A.; Rottier, O.; Geurts, L.; Naslain, D.; Neyrinck, A.; Lambert, D.M.; Muccioli, G.G.; Delzenne, N.M. Changes in gut microbiota control inflammation in obese mice through a mechanism involving GLP-2-driven improvement of gut permeability. Gut 2009, 58, 1044–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barekatain, R.; Chrystal, P.; Gilani, S.; McLaughlan, C. Expression of selected genes encoding mechanistic pathways, nutrient and amino acid transporters in jejunum and ileum of broiler chickens fed a reduced protein diet supplemented with arginine, glutamine and glycine under stress stimulated by dexamethasone. J. Anim. Physiol. Nutr. 2020, 105(1), 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, E.L.; Burchmore, R.J.; Sparks, N.H.; Eckersall, P.D. The effect of microbial challenge on the intestinal proteome of broiler chickens. Proteome Sci. 2016, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Gu, X.H.; Wang, X.L. Overexpression of heat shock protein 70 and its relationship to intestine under acute heat stress in broilers: 1. Intestinal structure and digestive function. Poult. Sci 2012, 91, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczka, P.; Tykałowski, B.; Ognik, K.; Kinsner, M.; Szkopek, D.; Wójcik, M.; Mikulski, D.; Jankowski, J. Increased arginine, lysine, and methionine levels can improve the performance, gut integrity and immune status of turkeys but the effect is interactive and depends on challenge conditions. Vet. Res. 2022, 53(1), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langie, S.A.; Kowalczyk, P.; Tomaszewski, B.; Vasilaki, A.; Maas, L.M.; Moonen, E.J.; Palagani, A.; Godschalk, R.W.L.; Tudek, B.; van Schooten, F.J.; Berghe, W.V.; Zabielski, R. , Mathers, JC. Redox and epigenetic regulation of the APE1 gene in the hippocampus of piglets: the effect of early life exposures. DNA Repair 2014, 18, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, M.S.U.; Rehman, S.U.; Yousaf, W.; Hassan, F.U.; Ahmad, W.; Liu, Q.; Pan, H. The potential of toll-like receptors to modulate avian immune system: exploring the effects of genetic variants and phytonutrients. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 671235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghareeb, K.; Awad, W.A.; Bohm, J.; Zebeli, Q. Impact of luminal and systemic endotoxin exposure on gut function, immune response and performance of chickens. J. World’s Poult. Sci. 2016, 72, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Sarson, A.J.; Gong, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, W.; Kang, Z.; Yu, H.; Sharif, S.; Han, Y. Expression Profiles of Genes in Toll-Like Receptor-Mediated Signaling of Broilers Infected with Clostridium perfringens. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2009, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Guo, Y.; Ding, M.; Su, A.; Li, W.; Tian, Y.; Li, K.; Sun, G.; Jiang, R.; Han, R.; Yan, F.; Kang, X. Identification of genes related to stress affecting thymus immune function in a chicken stress model using transcriptome analysis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2021, 138, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanu, H.K.; Kheravii, S.K.; Morgan, N.K.; Bedford, M.R.; Swick, R.A. Interactive effect of dietary calcium and phytase on broilers challenges with subclinical necrotic enteritis: part 2. Gut permeability, phytate ester concentrations, jejunal gene expression, and intestinal morphology. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 4914–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabacka, M.; Płonka, P.M.; Pierzchalska, M. The PPARα regulation of the gut physiology in regard to interaction with microbiota, intestinal immunity, metabolism, and permeability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23(22), 14156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şeren, N.; Dovinova, I.; Birim, D.; Kaftan, G.; Barancik, M.; Erdogan, M.A.; Armagan, G. Regulation of tight junction proteins and cell death by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonist in brainstem of hypertensive rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Teng, P.Y.; Kim, W.K.; Applegate, T.J. Assay considerations for fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran (FITC-d): an indicator of intestinal permeability in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100(7), 101202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, S.; Howarth, G.S.; Kitessa, S.M.; Tran, C.D.; Forder, R.E.A.; Hughes, R.J. New biomarkers for increased intestinal permeability induced by dextran sodium sulphate and fasting in chickens. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2017, 101(5), e237–e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, C.; Lumpkins, B.; Mathis, G.F.; França, M.; King, W.D.; Graugnard, D.E.; Dawson, K.A.; Applegate, T.J. Zinc source modulates intestinal inflammation and intestinal integrity of broiler chickens challenged with coccidia and Clostridium perfringens. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98(5), 2211–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzon, E.; Cuzzocrea, S. Absence of functional peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha enhanced ileum permeabilty during experimental colitis. Shock 2007, 28(2), 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, Z.; Abouelezz, K.F.M.; Fan, Q.; Li, L.; Lin, X.; Wang, Y.; Cui, X.; Ye, J.; Masoud, M.A.; Jiang, S.; Ma, X. Physiological effects of transport duration on stress biomarkers and meat quality of medium-growing Yellow broiler chickens. Animal 2021, 15(2), 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawab, A.; Ibtisham, F.; Li, G.; Kieser, B.; Wu, J.; Liu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Nawab, Y.; Li, K.; Xiao, M.; An, L. Heat stress in poultry production: Mitigation strategies to overcome the future challenges facing the global poultry industry. J. Therm. Biol. 2018, 78, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S.; Sah, N.; Mishra, B. Impact of heat stress on poultry health and performances, and potential mitigation strategies. Animals 2020, 10(8), 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladokun, S.; Adewole, D.I. Biomarkers of heat stress and mechanism of heat stress response in Avian species: Current insight and future perspectives from poultry science. J. Therm. Biol. 2022, 110, 103332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanes, C.G. Biology of stress in poultry with emphasis on glucocorticoids and the heterophil to lymphocyte ratio. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95(9), 2208–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Mushtaq, M.M.H.; Parvin, R.; Kang, H.K.; Kim, J.H.; Na, J.C.; Hwangbo, J.; Kim, J.D.; Yang, C.B.; Park, B.J.; Choi, H.C. Various levels and forms of dietary α-lipoic acid in broiler chickens: Impact on blood biochemistry, stress response, liver enzymes, and antibody titers. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94(2), 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yan, C.; Descovivh, K.; Phillips, C.J.C.; Chen, Y.; Huang, H.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, X. The effects of preslaughter electrical stunning on serum cortisol and meat quality parameters of a slow-growing Chinese chicken breed. Animals 2022, 12(20), 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetel, V.; Wyk, B.V.; Fraley, G.S. Sex differences in glucocorticoid responses to shipping stress in Pekin ducks. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101(1), 101534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczka, P.; Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I.; Półtorak, A.; Kinsner, M.; Szkopek, D.; Fotschki, B.; Juśkiewicz, J.; Banach, J.; Michalczuk, M. Cannabidiol affects breast meat volatile compounds in chickens subjected to different infection models. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barekatain, R.; Howarth, G.S.; Willson, N.L.; Cadogan, D.; Wilkinson, S. Excreta biomarkers in response to different gut barrier dysfunction models and probiotic supplementation in broiler chickens. PLoS ONE 2020, 15(8), e0237505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | PPARγ | PPARα | PPARδ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p-value | r | p-value | r | p-value | |

| HSP70 | 0.083 | 0.598 | -0.171 | 0.262 | 0.134 | 0.387 |

| TFF2 | 0.109 | 0.477 | -0.015 | 0.092 | 0.064 | 0.672 |

| P53 | 0.22 | 0.152 | 0.247 | 0.097 | 0.228 | 0.132 |

| ZO-1 | 0.295 | 0.052* | 0.320 | 0.030* | 0.324 | 0.030* |

| ZO-2 | 0.559 | 0.001* | 0.411 | 0.007* | 0.657 | 0.001* |

| TLR4 | 0.044 | 0.776 | 0.323 | 0.027* | -0.02 | 0.896 |

| OCLN | 0.361 | 0.015* | 0.459 | 0.001* | 0.290 | 0.051* |

| MUC-5B | 0.194 | 0.203 | 0.404 | 0.005* | 0.056 | 0.71 |

| MUC-2 | 0.226 | 0.136 | 0.313 | 0.032* | 0.474 | 0.001* |

| JAM-2 | 0.339 | 0.026* | 0.220 | 0.152 | 0.325 | 0.033* |

| IAP | 0.069 | 0.651 | -0.085 | 0.567 | 0.014 | 0.923 |

| E-cad | 0.545 | 0.001* | 0.436 | 0.003* | 0.24 | 0.113 |

| CLDN-3 | 0.346 | 0.022* | 0.351 | 0.017* | 0.212 | 0.162 |

| GLP-2 | 0.021 | 0.89 | -0.043 | 0.755 | 0.21 | 0.161 |

| OGG-1 | 0.139 | 0.376 | 0.176 | 0.248 | 0.236 | 0.123 |

| GPX-1 | 0.01 | 0.954 | -0.085 | 0.605 | -0.196 | 0.233 |

| CLDN-1 | 0.622 | 0.001* | 0.366 | 0.014* | 0.25 | 0.102 |

| CD36 | 0.449 | 0.002* | 0.177 | 0.299 | 0.051 | 0.736 |

| CLDN | 0.101 | 0.526 | 0.209 | 0.173 | 0.1 | 0.518 |

| CNR1 | 0.197 | 0.194 | 0.459 | 0.001* | 0.06 | 0.687 |

| Total of 204 Broiler Ross 308 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Number of birds | Additives | Challenge |

| CON | 34 | none | None |

| CBD | 34 | 30 g/kg CBD | None |

| C. perfringens | 34 | none | C. perfringens |

| LPS | 34 | none | E. coli LPS |

| CBD + C. perfringens | 34 | 30 g/kg CBD | C. perfringens |

| CBD + LPS | 34 | 30 g/kg CBD | E. coli LPS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).