Introduction

Fabry disease (FD, OMIM #301500) is an X-linked genetic metabolic disease caused by pathogenic variants in the GLA gene (HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee ID: 4296; Gene Entrez: 2717; NCBI reference sequence: NM_000169.3) and thus a deficiency in activity of the lysosomal alpha-galactosidase A (α-Gal A, Enzyme Commission number: EC 3.2.1.22; UniProt ID: P06280). This deficiency results in the progressive accumulation of globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) and its deactylated derivative globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3) in the lysosomes of various tissues and organs, leading to multisystem manifestations such as kidney failure, hypertrophic arythmogenic cardiomyopathy, and cerebrovascular events (Desnick et al. 2003, Germain 2010, Tuttolomondo et al. 2013). Starting in 2001, enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) (Schiffmann et al. 2001) (Eng et al. 2001) has significantly improved the care and lives of people with FD by reducing substrate accumulation and thus slowing disease progression. A pharmacological chaperone, migalastat, has also been approved since 2016 by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicine Agency (EMA) as an oral therapy, with restricted used to patients bearing amenable pathogenic variants of GLA (Germain et al. 2016).

Although gene-activated agalsidase alfa (Replagal®, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) is administered fortnightly by intravenous infusion over 40-60 minutes (Schiffmann et al. 2001, Goker-Alpan et al. 2016, Ramaswami et al. 2019, Hughes et al. 2021, Beck et al. 2022, Cybulla et al. 2022, Frustaci et al. 2023), recombinant agalsidase beta (Fabrazyme®, Sanofi, Framingham, MA, USA) is typically administered intravenously (again fortnightly) over a longer period (Eng et al. 2001, Hilz et al. 2010, Ortiz et al. 2016, Politei et al. 2016, Frustaci et al. 2023, Hopkin et al. 2023, Nowak et al. 2023, Wanner et al. 2023), often up to 3.5 hours in clinical practice, while the more recently EMA- and FDA-approved pegunigalsidase alfa (Elfabrio®) should be administered during a minimal time of 90 minutes after four mandatory infusions in a hospital setting (Schiffmann et al. 2019, Hughes et al. 2023, Linhart et al. 2023, Wallace et al. 2023, Germain and Linhart 2024). The European Medicines Agency’s summary of product characteristics (SPC) for agalsidase beta (Fabrazyme®) states that the infusion rate should be no more than 0.25 mg/min (15 mg/hour) initially to minimize the potential for infusion-associated reactions (IARs) but can be increased once patient tolerance has been established. Hence, depending on the patient’s bodyweight, the therapeutic dose of ERT may need to be delivered over a long period. However, in the absence of IARs or other adverse events, a lengthy infusion regime poses a significant burden on patients’ quality of life and might reduce treatment adherence and therefore effectiveness. Hence, shortening and optimizing infusion protocols to reduce treatment burden while maintaining safety and effectiveness is an area of ongoing research and clinical interest.

A few research groups have described their attempts to reduce the agalsidase beta infusion time safely and effectively. In 2007, a phase IV double-blind, randomized placebo controlled trial reported on decreasing the infusion time to 90 minutes in 51 patients treated with agalsidase beta or placebo. However, all the participants received pretreatment with paracetamol or ibuprofen, and some were given an antihistamine. Twenty-eight of the patients reported mild or moderate IARs (Banikazemi et al. 2007).

The use of a shortened agalsidase beta infusion protocol was reported in a Spanish series of six cases (five women and a man) (Sanchez-Purificacion et al. 2021). The first four to eight infusions were administered over several hours (at an initial, fixed rate of 0.25 mg/min) but subsequent infusions were gradually shortened to as little as 45 minutes in a hospital setting. Premedication with 1 g paracetamol was provided, and patients were closely monitored during the infusion. The outcomes were favourable, and only one patient (a woman with a history of allergies) experienced an IAR after the tenth (45-minute) infusion. The IAR was treated with antihistamines and corticosteroids (Sanchez-Purificacion et al. 2021).

An Italian study reported retrospectively on a stepwise infusion rate escalation protocol in a cohort of 53 patients with FD (Riccio et al. 2021). The initial, standard infusion duration was as long as 7 hours in the heaviest patients. Patients experiencing an IAR were premedicated before subsequent infusions. Fifty-two of the 53 patients were able to move to a shorter infusion, and this duration was below 2 hours in 38 patients. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) infusion duration was significantly shorter in previously treated patients than in ERT-naive patients (100.91 ± 15.14 minutes vs. 130.71 ± 38.53 minutes, respectively; p<0.01) (Riccio et al. 2021).

In 2022, the start of a multicentre Italian prospective study with a dose infusion rate of 15 mg/h for the first four months was described (Mignani and Pieruzzi 2022). Patients experiencing an IAR were premedicated before subsequent infusions. During the following four infusions, the infusion rate was increased progressively from 15 to 35 mg/h, giving the shortest infusion time at end of the sixth month (Mignani and Pieruzzi 2022). The study’s results were published in 2024: 25 of the 31 enrolled patients were treatment-naive, and the other six had been switched from agalsidase alfa to agalsidase beta. Only one patient experienced a (mild) IAR, and 28 of the patients were seronegative at month 12 (Mignani et al. 2024).

In a report published in 2023, a Japanese post-marketing study described the impact of short (<90 min) infusions versus standard (≥90 min) infusions on various safety variables in children and adults with FD, respectively (Lee et al. 2023). The presence or absence of premedication was not reported. The incidence of serious adverse events was low (less than 1%) in patients weighing less than 30 kg, and the frequency of such events in given individuals fell over time. The authors concluded that gradual reductions in infusion times may be feasible in patients who tolerate treatment well (Lee et al. 2023).

Despite these valuable contributions, critical questions persist with regard to the initiation of shorter infusion times. To address these knowledge gaps, we evaluated the safety and tolerability of a shortened infusion time for agalsidase beta in adult ERT-naive and ERT-experienced patients with classic or later-onset FD. Specifically, we assessed clinical variables and patient-reported treatment satisfaction and investigated the feasibility of reducing the infusion duration from 2.5-3.5 hours to 90 minutes in routine clinical care (as outlined in the SPC), without the need for premedication in adult patients at various stages of disease progression and severity, in the absence of recent infusion-associated reaction.

2. Patients and Methods

Between March 2023 and May 2024, we received 39 consecutive adult patients with genetically confirmed FD scheduled for an infusion of agalsidase beta in our European Reference Network (ERN) tertiary center for lysosomal diseases (

www.centre-geneo.com). The patients had been treated at-home with fortnightly 2.5- to 3.5-hour intravenous infusions of agalsidase beta with the exception of seven patients who were naive to enzyme replacement therapy. Baseline characteristics (including age, sex,

GLA variant, bodyweight, and medical history of comorbidities) were recorded for each patient (

Table 1). For all patients, the infusion duration was set to 90 minutes (as mentioned in the SPC of agalsidase beta) without the administration of premedication. In addition for a few participants (n=7) and following the provision of specific written request, the infusion time could be reduced still further to between 50 and 60 minutes under strict medical supervision. Once an infusion had started, the infusion rate was not modified. Vital signs (including body temperature, blood pressure, and resting heart rate) were measured before and after the infusion. Any IARs or other adverse events reported by the patient or the attending healthcare professionals were documented (

Table 2).

In line with the French legislation on retrospective analyses of anonymized data from routine clinical practice, approval by an institutional review board was not required. The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant institutional guidelines.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics, genotype characteristics, infusion parameters, and safety outcomes. Continuous variables were reported as the mean ± SD, mean (range) or the median [interquartile range (IQR)], as appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as the frequency (percentage). Given the descriptive nature of the study, no formal hypotheses were tested.

3. Results

Thirty-nine consecutive adult patients (21 males and 18 females) bearing 29 different pathogenic

GLA variants (

Table 1) were scheduled for a hospital visit in routine clinical care. The mean (range) age was 50.4 (24-78), and the mean bodyweight was 73.3 kg. Six of the 39 patients were ERT-naive. Fifteen patients presented with significant comorbidities: these included end-stage renal disease with the requirement for dialysis or kidney transplantation, a history of stroke and/or transient ischaemic attack, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, an elevated body weight requiring 105 mg of agalsidase beta (n=5) or a history of IARs (though not ongoing) (

Table 2).

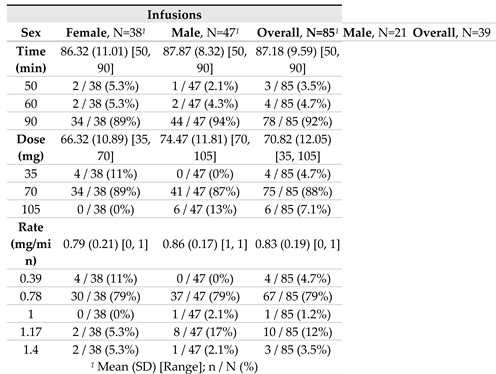

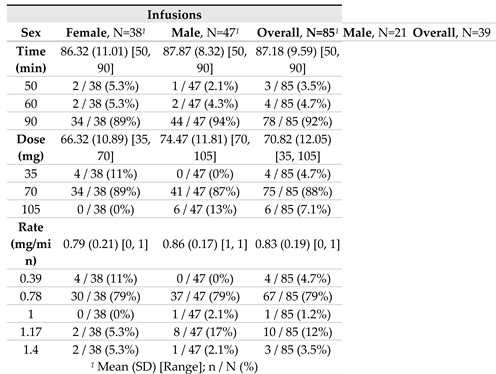

For a total of 85 infusions, the mean dose of agalsidase beta infusion was 70.8 mg, delivered over a mean period of 87.2 minutes; this yielded a mean infusion rate of 0.83 mg/min. The highest agalsidase beta infusion rate recorded in the setting of our routine regimen was 1.17 mg/min, which corresponds to 105 mg of agalsidase beta infused over 90 minutes in patients with higher body weight (>95 kgs) (

Table 1). Anecdotally, the ultimate highest agalsidase beta infusion rate was 1.40 mg/min in the three patients who for various imperative reasons or personal convenience requested a shorter infusion time under strict medical supervision (70 mg of agalsidase beta infused over 50 minutes), without any side effect (

Table 2).

All 39 participants tolerated the shorter infusions well, with no reports of adverse events (not even discomfort or IARs) during or following any of the procedures. The vital signs remained stable throughout the infusion process, with no clinically significant changes. The level of patient satisfaction was high.

4. Discussion

Our present data on clinical variables and vital signs showed that it was feasible to reducing the agalsidase beta infusion duration to 90 minutes (as outlined in the summary of product characteristics of agalsidase beta) in routine clinical care, without the need for premedication and based on individual patient requirements. Anecdotally, an infusion time below 90 minutes was specifically requested by patients in a few imperative cases and then applied under strict medical supervision. Importantly, no adverse events or IARs were reported during or after for the 85 infusions administered, and the patients’ vital signs remained stable.

Although our single-centre case series differed from previous studies in this field in several respects, we confirmed the overall literature findings on the safety and tolerability of shorter agalsidase beta infusions. While we assessed a specific 90-minute infusion protocol in most patients, Spanish authors tried to shorten the infusion time even more – to as little as 45 minutes (Sanchez-Purificacion et al. 2021). Similarly, in the small subset of patients (n=7) who for personal convenience or imperative reasons on the day of the infusion requested it from us, further shortening of the infusion time to either 60 minutes (n=4) or 50 minutes (n=3) under strict medical supervision was done without any adverse event. Although some of the patients studied by Italian colleagues were able to move to infusions of between 90 and 120 minutes, the study’s main focus was the efficacy and safety of a fortnightly infusion regimen of initially up to 7 hours (for the heaviest patients) (Riccio et al. 2021) that reflected standard practice from the time of the clinical development program of agalsidase beta (Eng et al. 2001). In contrast, our study sought to explore the feasibility and safety profile of shorter infusion durations, specifically targeting a 90-minute infusion regimen. Our present results are also partially or fully in line with several findings of a previous Japanese study (Lee et al. 2023). The authors observed a non-significant trend towards fewer adverse events in patients weighing less than 30 kg. Likewise, we did not observed obvious disparities in safety outcomes as a function of the patient’s bodyweight or comorbidities. It is noteworthy that the few published studies on this topic were conducted in distinct populations and settings but provide complementary insights into the safety and feasibility of shorter agalsidase beta infusions durations in FD patients receiving enzyme therapy (Mignani et al. 2024). Our present findings contribute to the growing body of evidence in favour of moving towards the patient-centred treatment of rare lysosomal disorders, including home-based treatment.

Our study had several strengths. Firstly, we included consecutive (but recent IAR-free) patients, which reduced selection bias. Some of the study participants (n=6) were agalsidase-naive, others suffered from advanced FD and/or major comorbidities (such as heart failure and kidney failure), and yet others had a past history of allergic reactions; this heterogeneity illustrated the potential for shortening the infusion time in a real-life patient population. Secondly, premedication was not administered.

Our study also had several limitations. Firstly, the sample size (n=39 patients) was relatively small. Secondly, the study duration was short; hence, further investigation will be needed to validate the long-term safety of optimized infusion protocols. Thirdly, we did not use a validated questionnaire to assess the patients’ level of satisfaction with the shortened infusion. In the future, longer-term multicentre studies should address these limitations and explore safety, immunological variables, and patient-centred outcomes (including quality of life) in individuals receiving optimized agalsidase beta infusion protocols which for safety reasons has for now been implemented only in our tertiary referral center (

www.centre-geno.com) and not yet transitioned to a home care setting.

In conclusion, our results support the safety and feasibility of shortening the agalsidase beta infusion time to 90 minutes in non-premedicated, IAR-free, adult patients at various stages of of FD. A pragmatic, optimized regimen should increase flexibility, reduce the treatment burden, improve patient adherence, and ultimately improve the patient-centred management of this complex metabolic disorder (Veldman et al. 2024).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific funding from agencies or organizations in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available, due to the privacy of the study participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients for their participation and Aicha EL MOUDEN, Yé FAN, Laeticia TJOMB, and Wenting TRANG for their contribution to data collection.

Conflict of Interest Statement

D.P.G. is a consultant for Chiesi, Idorsia, Sanofi, and Takeda. APV, LTTP and LB report no conflict of interest.

References

- Banikazemi, M., J. Bultas, S. Waldek, W. R. Wilcox, C. B. Whitley, M. McDonald, R. Finkel, S. Packman, D. G. Bichet, D. G. Warnock, R. J. Desnick and G. Fabry Disease Clinical Trial Study (2007). Agalsidase-beta therapy for advanced Fabry disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 146: 77-86.

- Beck, M.; Ramaswami, U.; Hernberg-Ståhl, E.; Hughes, D.A.; Kampmann, C.; Mehta, A.B.; Nicholls, K.; Niu, D.-M.; Pintos-Morell, G.; Reisin, R.; et al. Twenty years of the Fabry Outcome Survey (FOS): insights, achievements, and lessons learned from a global patient registry. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cybulla, M.; Nicholls, K.; Feriozzi, S.; Linhart, A.; Torras, J.; Vujkovac, B.; Botha, J.; Anagnostopoulou, C.; West, M.L. Renoprotective Effect of Agalsidase Alfa: A Long-Term Follow-Up of Patients with Fabry Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desnick, R.J.; Brady, R.; Barranger, J.; Collins, A.J.; Germain, D.P.; Goldman, M.; Grabowski, G.; Packman, S.; Wilcox, W.R. Fabry Disease, an Under-Recognized Multisystemic Disorder: Expert Recommendations for Diagnosis, Management, and Enzyme Replacement Therapy. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003, 138, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, C.M.; Guffon, N.; Wilcox, W.R.; Germain, D.P.; Lee, P.; Waldek, S.; Caplan, L.; Linthorst, G.E.; Desnick, R.J. Safety and Efficacy of Recombinant Human α-Galactosidase A Replacement Therapy in Fabry's Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Fabrazyme®. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/fabrazyme-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Frustaci, A.; Verardo, R.; Galea, N.; Alfarano, M.; Magnocavallo, M.; Marchitelli, L.; Sansone, L.; Belli, M.; Cristina, M.; Frustaci, E.; et al. Long-Term Clinical-Pathologic Results of Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Prehypertrophic Fabry Disease Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2024, 13, e032734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, D. P. (2010). “Fabry disease”. Orphanet J Rare Dis 5: 30.

- Germain DP, Hughes D, Nicholls K, Bichet D, Giugliani R, Wilcox WR (2016) Treatment of Fabry’s disease with the pharmacologic chaperone migalastat. N Engl J Med 375: 545-555.

- Germain, D.P.; Linhart, A. Pegunigalsidase alfa: a novel, pegylated recombinant alpha-galactosidase enzyme for the treatment of Fabry disease. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1395287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goker-Alpan, O.; Longo, N.; McDonald, M.; Shankar, S.P.; Schiffmann, R.; Chang, P.; Shen, Y.; Pano, A. An open-label clinical trial of agalsidase alfa enzyme replacement therapy in children with Fabry disease who are naïve to enzyme replacement therapy. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2016, ume 10, 1771–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilz, M.J.; Marthol, H.; Schwab, S.; Kolodny, E.H.; Brys, M.; Stemper, B. Enzyme replacement therapy improves cardiovascular responses to orthostatic challenge in Fabry patients. J. Hypertens. 2010, 28, 1438–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkin, R.J.; Cabrera, G.H.; Jefferies, J.L.; Yang, M.; Ponce, E.; Brand, E.; Feldt-Rasmussen, U.; Germain, D.P.; Guffon, N.; Jovanovic, A.; et al. Clinical outcomes among young patients with Fabry disease who initiated agalsidase beta treatment before 30 years of age: An analysis from the Fabry Registry. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2023, 138, 106967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.; Linhart, A.; Gurevich, A.; Kalampoki, V.; Jazukeviciene, D.; Feriozzi, S. Prompt Agalsidase Alfa Therapy Initiation is Associated with Improved Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes in a Fabry Outcome Survey Analysis. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, ume 15, 3561–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.; Gonzalez, D.; Maegawa, G.; Bernat, J.A.; Holida, M.; Giraldo, P.; Atta, M.G.; Chertkoff, R.; Alon, S.; Almon, E.B.; et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of pegunigalsidase alfa: A multicenter 6-year study in adult patients with Fabry disease. Anesthesia Analg. 2023, 25, 100968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.S.; Tsurumi, M.; Eto, Y. Safety and tolerability of agalsidase beta infusions shorter than 90 min in patients with Fabry disease: post-hoc analysis of a Japanese post-marketing study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2023, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenders, M.; Brand, E. Effects of Enzyme Replacement Therapy and Antidrug Antibodies in Patients with Fabry Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 2265–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linhart, A.; Dostálová, G.; Nicholls, K.; West, M.L.; Tøndel, C.; Jovanovic, A.; Giraldo, P.; Vujkovac, B.; Geberhiwot, T.; Brill-Almon, E.; et al. Safety and efficacy of pegunigalsidase alfa in patients with Fabry disease who were previously treated with agalsidase alfa: results from BRIDGE, a phase 3 open-label study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2023, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignani, R.; Americo, C.; Aucella, F.; Battaglia, Y.; Cianci, V.; Sapuppo, A.; Lanzillo, C.; Pennacchiotti, F.; Tartaglia, L.; Marchi, G.; et al. Reducing agalsidase beta infusion time in Fabry patients: low incidence of antibody formation and infusion-associated reactions in an Italian multicenter study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2024, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignani, R.; Pieruzzi, F. Safety of a protocol for reduction of agalsidase beta infusion time in Fabry disease: An Italian multi-centre study. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2021, 30, 100838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak A, Dormond O, Monzambani V, Huynh-Do U, Barbey F. Agalsidase-beta should be proposed as first line therapy in classic male Fabry patients with undetectable alpha-galactosidase A activity. Mol Genet Metab. 2022; 137: 173-178.

- Ortiz A, Abiose A, Bichet DG, Cabrera G, Charrow J, Germain DP, Hopkin RJ, Jovanovic A, Linhart A, Maruti SS, Mauer M, Oliveira JP, Patel MR, Politei J, Waldek S, Wanner C, Yoo HW, Warnock DG. T ime to treatment benefit for adult patients with Fabry disease receiving agalsidase beta: data from the Fabry Registry. J Med Genet. 2016; 53: 495-502.

- Pisani, A.; Pieruzzi, F.; Cirami, C.L.; Riccio, E.; Mignani, R. Interpretation of GFR slope in untreated and treated adult Fabry patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 39, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politei J, Schenone AB, Cabrera G, Heguilen R, Szlago M. Fabry disease and enzyme replacement therapy in classic patients with same mutation: different formulations--different outcome? Clin Genet. 2016; 89: 88-92.

- Ramaswami, U.; Beck, M.; Hughes, D.; Kampmann, C.; Botha, J.; Pintos-Morell, G.; West, M.L.; Niu, D.-M.; Nicholls, K.; Giugliani, R. Cardio- Renal Outcomes With Long- Term Agalsidase Alfa Enzyme Replacement Therapy: A 10- Year Fabry Outcome Survey (FOS) Analysis. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2019, ume 13, 3705–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, E.; Zanfardino, M.; Franzese, M.; Capuano, I.; Buonanno, P.; Ferreri, L.; Amicone, M.; Pisani, A. Stepwise shortening of agalsidase beta infusion duration in Fabry disease: Clinical experience with infusion rate escalation protocol. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2021, 9, e1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Purificación, A.; Castellano, A.; Gutiérrez, B.; Gálvez, M.; Díaz, B.; Pérez, T.; Arnalich, F. Reduction of agalsidase beta infusion time in patients with fabry disease: A case series report and suggested protocol. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2021, 27, 100755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffmann, R. B. Kopp, H. A. Austin, 3rd, S. Sabnis, D. F. Moore, T. Weibel, J. E. Balow and R. O. Brady (2001). “Enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease: a randomized controlled trial.” JAMA 285: 2743-2749.

- Schiffmann R, Goker-Alpan O, Holida M, Giraldo P, Barisoni L, Colvin RB, Jennette CJ, Maegawa G, Boyadjiev SA, Gonzalez D, Nicholls K, Tuffaha A, Atta MG, Rup B, Charney MR, Paz A, Szlaifer M, Alon S, Brill-Almon E, Chertkoff R, Hughes D (2019). Pegunigalsidase alfa, a novel PEGylated enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease, provides sustained plasma concentrations and favorable pharmacodynamics: A 1-year Phase 1/2 clinical trial. J Inherit Metab Dis. 42: 534-544.

- Tuttolomondo, A.; Pecoraro, R.; Simonetta, I.; Miceli, S.; Pinto, A.; Licata, G. Anderson-Fabry Disease: A Multiorgan Disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 19, 5974–5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldman, B.C.F.; Schoenmakers, D.H.; van Dussen, L.; Datema, M.R.; Langeveld, M. Establishing Treatment Effectiveness in Fabry Disease: Observation-Based Recommendations for Improvement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace EL, Ozlem Goker-Alpan, Wilcox WR, Holida M, Bernat J, Longo N et al. (2023) Head-to-head trial of pegunigalsidase alfa versus agalsidase beta in patients with Fabry disease and deteriorating renal function: results from the 2-year randomized phase 3 BALANCE study. J Med Genet 61: 520-530.

- Wanner, C.; Ortiz, A.; Wilcox, W.R.; Hopkin, R.J.; Johnson, J.; Ponce, E.; Ebels, J.T.; Batista, J.L.; Maski, M.; Politei, J.M.; et al. Global reach of over 20 years of experience in the patient-centered Fabry Registry: Advancement of Fabry disease expertise and dissemination of real-world evidence to the Fabry community. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2023, 139, 107603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Patients demographics.

Table 1.

Patients demographics.

| Patients |

| Sex |

Female, N=181

|

Male, N=211

|

Overall, N=391

|

| Age1 |

54.83 (13.81) [32, 78] |

46.52 (11.88) [24, 73] |

50.36 (13.31) [24, 78] |

| Weight1 |

66.60 (11.76) [48, 95] |

78.90 (12.74) [57, 106] |

73.23 (13.64) [48, 106] |

|

GLAgenetic variants

|

|

|

| deletion2

|

0 / 18 (0%) |

1 / 21 (4.8%) |

1 / 39 (2.6%) |

| frameshift2

|

0 / 18 (0%) |

4 / 21 (19%) |

4 / 39 (10%) |

| indel2

|

0 / 18 (0%) |

1 / 21 (4.8%) |

1 / 39 (2.6%) |

| missense2

|

15 / 18 (83%) |

13 / 21 (62%) |

28 / 39 (72%) |

| nonsense2

|

3 / 18 (17%) |

1 / 21 (4.8%) |

4 / 39 (10%) |

| splicing2

|

0 / 18 (0%) |

1 / 21 (4.8%) |

1 / 39 (2.6%) |

| Phenotype |

|

|

|

| Classic2

|

17 / 18 (94%) |

20 / 21 (95%) |

37 / 39 (95%) |

| Late-onset2

|

1 / 18 (5.6%) |

1 / 21 (4.8%) |

2 / 39 (5.1%) |

| Significant comorbidities |

6 / 18 (33%) |

11 / 21 (52%) |

17 / 39 (44%) |

| Naïve |

3 / 18 (17%) |

3 / 21 (14%) |

6 / 39 (15%) |

|

Table 2.

Summary of vital signs of patients before and after 90-minute-infusions of agalsidase beta.

Table 2.

Summary of vital signs of patients before and after 90-minute-infusions of agalsidase beta.

| Patient ID |

Sex |

Phenotype |

Weight(kg) |

Dose(mg) |

Time (min) |

Rate(mg/min) |

Vitals before infusion |

Vitals after infusion |

IAR |

History of IAR |

| BT (°C) |

BP (mmHg) |

HR (bpm) |

BT (°C) |

BP (mmHg) |

HR (bpm) |

| P#1 |

M |

Classic |

63,5 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,4 |

118/86 |

73 |

36,5 |

117/88 |

72 |

No |

No |

| |

59 |

0,78 |

36,8 |

131/82 |

75 |

36,1 |

124/81 |

77 |

No |

|

| |

58 |

0,78 |

36,9 |

131/87 |

74 |

36,8 |

123/70 |

72 |

No |

|

| P#2 |

F |

Classic |

67,3 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,1 |

106/74 |

76 |

36,2 |

110/75 |

74 |

No |

No |

| P#3 |

F |

Classic |

66 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,4 |

106/75 |

62 |

36,5 |

104/75 |

63 |

No |

No |

| P#4 |

F |

Classic |

90 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

126/79 |

78 |

36,2 |

111/79 |

75 |

No |

No |

| |

90 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,1 |

121/68 |

76 |

36 |

134/81 |

81 |

No |

| |

90 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

132/89 |

66 |

36,8 |

110/76 |

75 |

No |

| |

90 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,3 |

121/85 |

62 |

36,3 |

112/76 |

66 |

No |

| |

90 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,6 |

111/70 |

75 |

36,3 |

127/88 |

82 |

No |

| |

91 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,2 |

124/82 |

73 |

36,1 |

126/80 |

70 |

No |

| P#5 |

M |

Classic |

69 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,2 |

113/80 |

62 |

36,1 |

110/87 |

60 |

No |

No |

| P#6 |

M |

Classic |

80 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,5 |

129/93 |

85 |

36,9 |

145/90 |

70 |

No |

No |

| |

79 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,4 |

106/68 |

68 |

36,4 |

126/78 |

77 |

No |

| |

79 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,4 |

115/80 |

73 |

36,6 |

125/83 |

66 |

No |

| |

79 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,4 |

138/88 |

75 |

36,6 |

135/87 |

75 |

No |

| |

79 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,5 |

118/81 |

67 |

36,5 |

126/80 |

66 |

No |

| |

79 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,3 |

133/79 |

88 |

36,3 |

132/80 |

81 |

No |

| |

78 |

70 |

70 |

1,00 |

36,6 |

119/84 |

71 |

36,4 |

121/81 |

71 |

No |

| P#7 |

F |

Classic |

53 |

35 |

90 |

0,39 |

37 |

110/58 |

58 |

37 |

95/48 |

59 |

No |

No |

| |

54 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,4 |

101/47 |

53 |

37,3 |

111/64 |

57 |

No |

| |

54 |

35 |

90 |

0,39 |

36,8 |

113/68 |

57 |

36,6 |

98/55 |

61 |

No |

| |

54 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,9 |

108/48 |

93 |

37 |

100/51 |

47 |

No |

| |

54 |

35 |

90 |

0,39 |

36 |

97/56 |

68 |

37 |

101/53 |

57 |

No |

| |

54 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,5 |

103/48 |

66 |

36 |

98/55 |

68 |

No |

| |

55 |

35 |

90 |

0,39 |

36,6 |

110/51 |

59 |

37,1 |

94/61 |

52 |

No |

| |

55 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,3 |

104/54 |

78 |

36 |

107/49 |

69 |

No |

| |

55 |

70 |

50 |

1,40 |

36,6 |

106/70 |

63 |

36,4 |

112/74 |

65 |

No |

| P#8 |

F |

Classic |

95 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

157/90 |

71 |

36,3 |

149/96 |

67 |

No |

No |

| |

96 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,2 |

146/80 |

63 |

36,1 |

140/80 |

66 |

No |

| P#9 |

F |

Classic |

70 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,8 |

114/64 |

73 |

36,9 |

118/68 |

79 |

No |

No |

| P#10 |

F |

Classic |

78 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,6 |

120/84 |

65 |

36,5 |

120/85 |

60 |

No |

No |

| |

75 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

122/63 |

63 |

36,6 |

127/87 |

57 |

No |

| P#11 |

F |

Classic |

57 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

118/76 |

62 |

36,3 |

132/60 |

74 |

No |

No |

| |

57 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

104/78 |

60 |

36,4 |

98/49 |

69 |

No |

| |

58 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,5 |

105/58 |

60 |

36,4 |

121/53 |

60 |

No |

| P#12 |

|

Classic |

80 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

142/73 |

61 |

36 |

142/73 |

61 |

No |

No |

| |

80,5 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

138/81 |

63 |

36,5 |

148/83 |

89 |

No |

| |

80 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

130/74 |

57 |

36 |

139/80 |

59 |

No |

| |

80 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,1 |

132/77 |

58 |

36 |

138/78 |

59 |

No |

| |

80 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,2 |

130/77 |

55 |

36,7 |

132/78 |

54 |

No |

| |

84 |

70 |

80 |

0,88 |

35 |

130/75 |

62 |

36,4 |

132/76 |

60 |

No |

| P#13 |

F |

Classic |

70 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,6 |

131/63 |

62 |

37,1 |

129/78 |

64 |

No |

No |

| |

68 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,7 |

125/78 |

63 |

36,4 |

150/64 |

58 |

No |

| |

68 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,4 |

146/72 |

50 |

36,7 |

131/90 |

53 |

No |

| P#14 |

M |

Classic |

93 |

105 |

90 |

1,17 |

36,2 |

117/89 |

75 |

36,5 |

149/98 |

68 |

No |

No |

| P#15 |

M |

Classic |

80 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

161/75 |

64 |

36,1 |

153/87 |

57 |

No |

No |

| |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,3 |

141/84 |

60 |

36,2 |

135/68 |

65 |

No |

| P#16 |

F |

Classic |

55 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

135/77 |

55 |

36,8 |

141/72 |

58 |

No |

No |

| P#17 |

F |

Later-onset |

56 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,3 |

104/64 |

66 |

36,6 |

100/64 |

74 |

No |

No |

| |

56 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,4 |

109/74 |

79 |

36,7 |

98/68 |

72 |

No |

| |

56 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

37 |

95/66 |

70 |

36,9 |

88/64 |

65 |

No |

| |

56 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,88 |

98/71 |

63 |

36,7 |

100/71 |

64 |

No |

| P#18 |

M |

Later-onset |

106 |

105 |

90 |

1,17 |

36,5 |

124/77 |

61 |

36,4 |

124/74 |

60 |

No |

No |

| P#19 |

M |

Classic |

74 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

113/74 |

57 |

36,5 |

140/82 |

51 |

No |

No |

| P#20 |

M |

Classic |

78 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

142/84 |

56 |

36,1 |

133/118 |

52 |

No |

No |

| |

80 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,4 |

149/99 |

54 |

36,4 |

153/93 |

55 |

No |

| |

76 |

70 |

60 |

1,17 |

36,2 |

136/79 |

50 |

36,7 |

138/80 |

52 |

No |

| P#21 |

M |

Classic |

93 |

105 |

90 |

1,17 |

36,5 |

131/76 |

52 |

36,7 |

137/62 |

53 |

No |

No |

| |

93 |

105 |

90 |

1,17 |

36 |

139/84 |

53 |

35,9 |

148/85 |

56 |

No |

| P#22 |

M |

Classic |

71 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,3 |

93/72 |

66 |

36,1 |

94/75 |

65 |

No |

No |

| P#23 |

M |

Classic |

85 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

109/84 |

51 |

36,3 |

98/57 |

48 |

No |

No |

| P#24 |

M |

Classic |

60 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,2 |

112/64 |

65 |

36,6 |

110/64 |

62 |

No |

No |

| P#25 |

M |

Classic |

70 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36 |

121/66 |

83 |

36,7 |

115/55 |

68 |

No |

No |

| P#26 |

M |

Classic |

57 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,4 |

102/66 |

64 |

36,5 |

105/66 |

68 |

No |

No |

| P#27 |

F |

Classic |

74 |

70 |

60 |

1,17 |

36,7 |

124/82 |

57 |

36,3 |

123/81 |

59 |

No |

No |

| |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,6 |

120/77 |

60 |

36,7 |

139/89 |

61 |

No |

| P#28 |

F |

Classic |

75 |

70 |

90 |

0,88 |

36,7 |

124/82 |

57 |

36,5 |

125/80 |

56 |

No |

No |

| |

Classic |

75 |

70 |

90 |

0,88 |

37,1 |

110/63 |

62 |

36.7 |

120/65 |

61 |

No |

| P#29 |

F |

Classic |

60 |

70 |

90 |

0,88 |

35,9 |

107/72 |

78 |

36,3 |

109/73 |

68 |

No |

Yes |

| |

36,8 |

122/94 |

72 |

36,4 |

147/94 |

64 |

No |

| P#30 |

F |

Classic |

74 |

70 |

60 |

1,17 |

36,2 |

139/84 |

76 |

36,3 |

140/83 |

71 |

No |

No |

| P#31 |

M |

Classic |

94.5 |

105 |

90 |

1,17 |

36 |

143/93 |

72 |

36,5 |

144/95 |

70 |

No |

No |

| P#32 |

F |

Classic |

47.5 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,5 |

141/80 |

75 |

36,1 |

122/69 |

60 |

No |

No |

| P#33 |

M |

Classic |

78 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,2 |

114/67 |

55 |

36,1 |

117/71 |

49 |

No |

No |

| |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,5 |

132/95 |

56 |

36,5 |

128/77 |

60 |

No |

| |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,8 |

142/92 |

58 |

36,2 |

144/85 |

65 |

No |

| |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,4 |

122/70 |

55 |

36,4 |

122/70 |

55 |

No |

| |

70 |

90 |

1,00 |

36,4 |

131/83 |

61 |

36,8 |

132/82 |

71 |

No |

| P#34 |

F |

Classic |

57 |

70 |

50 |

1,40 |

36,5 |

110/69 |

60 |

36,3 |

119/71 |

62 |

No |

No |

| P#35 |

M |

Classic |

71 |

70 |

50 |

1,40 |

36 |

110/89 |

83 |

36,2 |

109/79 |

84 |

No |

No |

| P#36 |

F |

Classic |

80 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,5 |

121/80 |

78 |

36,6 |

123/81 |

75 |

No |

No |

| P#37 |

M |

Classic |

70 |

70 |

60 |

1,17 |

36,2 |

132/82 |

73 |

36,3 |

131/76 |

68 |

No |

No |

| P#38 |

F |

Classic |

64 |

70 |

90 |

0,78 |

36,8 |

109/73 |

61 |

36,7 |

106/64 |

68 |

No |

No |

| P#39 |

M |

Classic |

94 |

105 |

90 |

1,17 |

35,8 |

131/83 |

51 |

36,2 |

128/75 |

53 |

No |

No |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).