Submitted:

23 September 2024

Posted:

24 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Materials

2.2. Modelling Growth Parameters and Population Variability

2.3. Modelling Feeding and Spawning Migration

2.4. Estimating Temporal Heterogeneity and Identifying driving Factors

2.4. Meta-Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

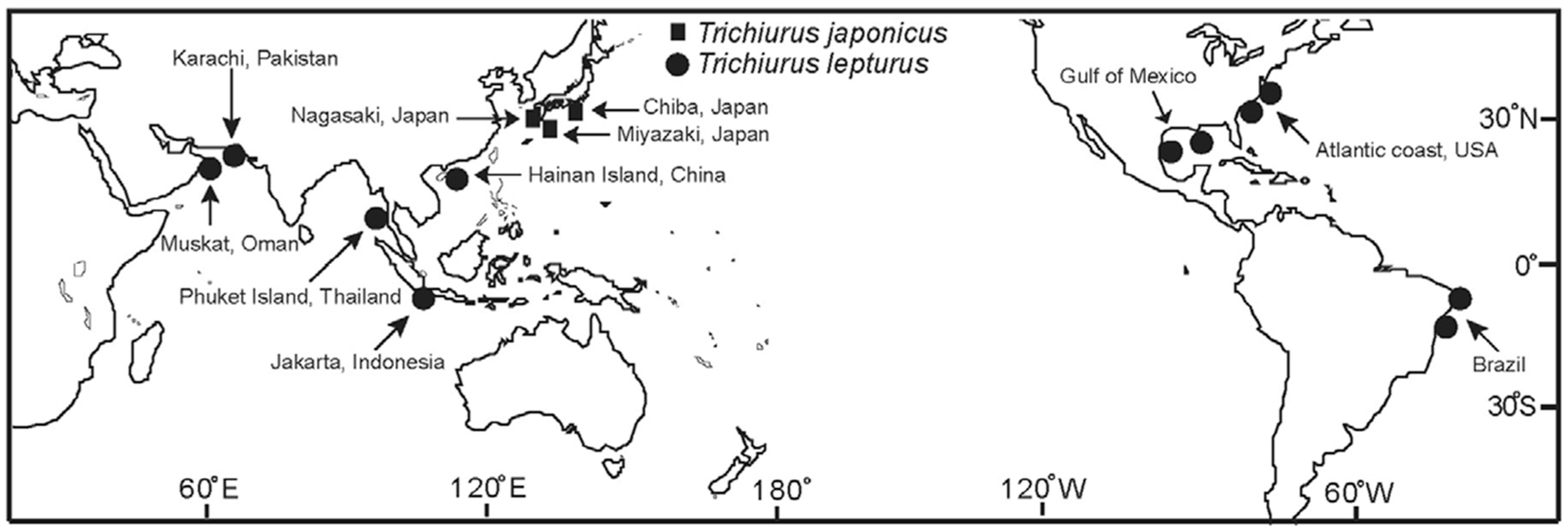

3.1. Main Marine Ecosystems (i.e. Region 1, Region 2, Region 3 and Region 4)

3.2. Seas of Japan/East Sea (T. japonicus)

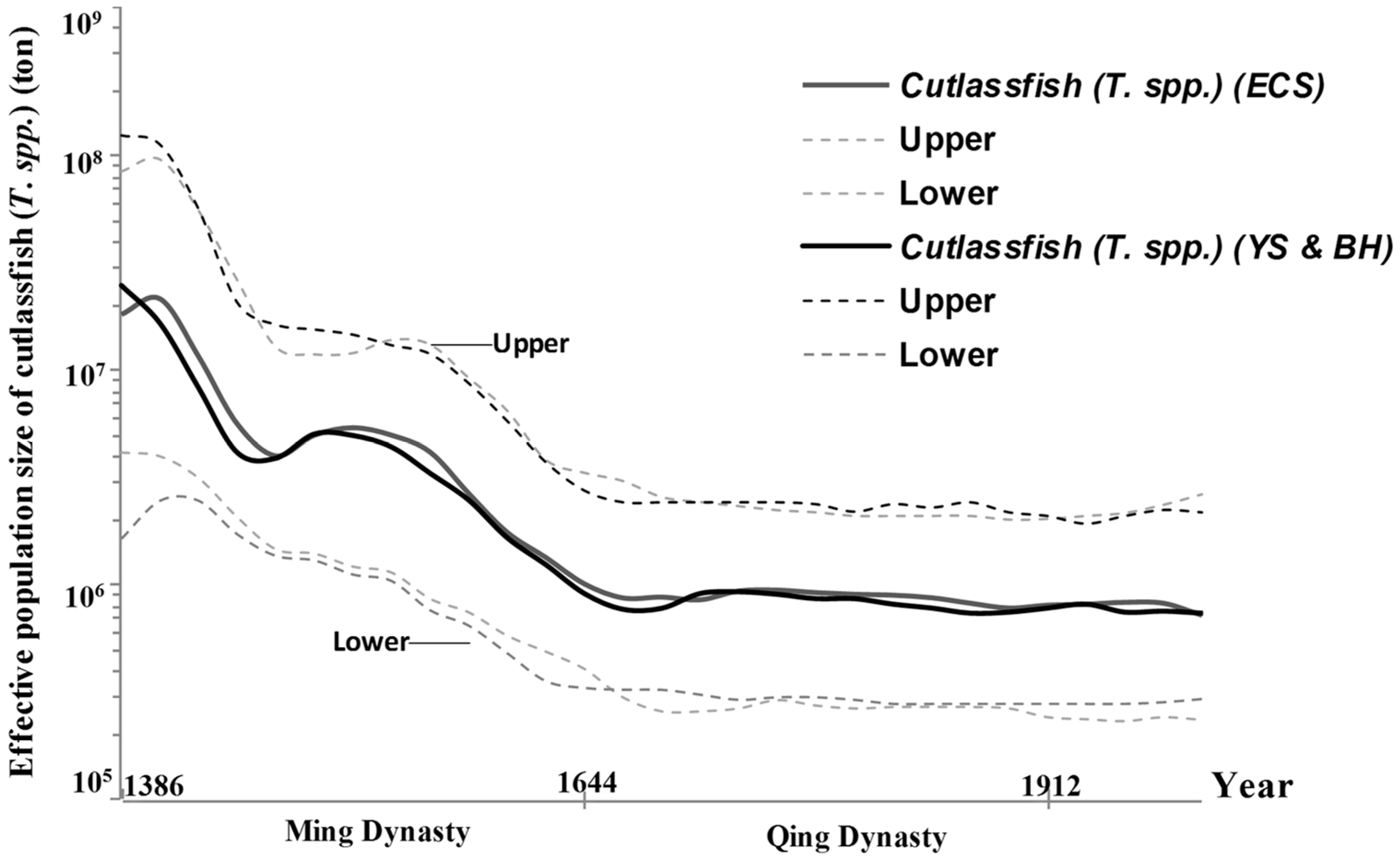

3.3. Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea (T. japonicas)

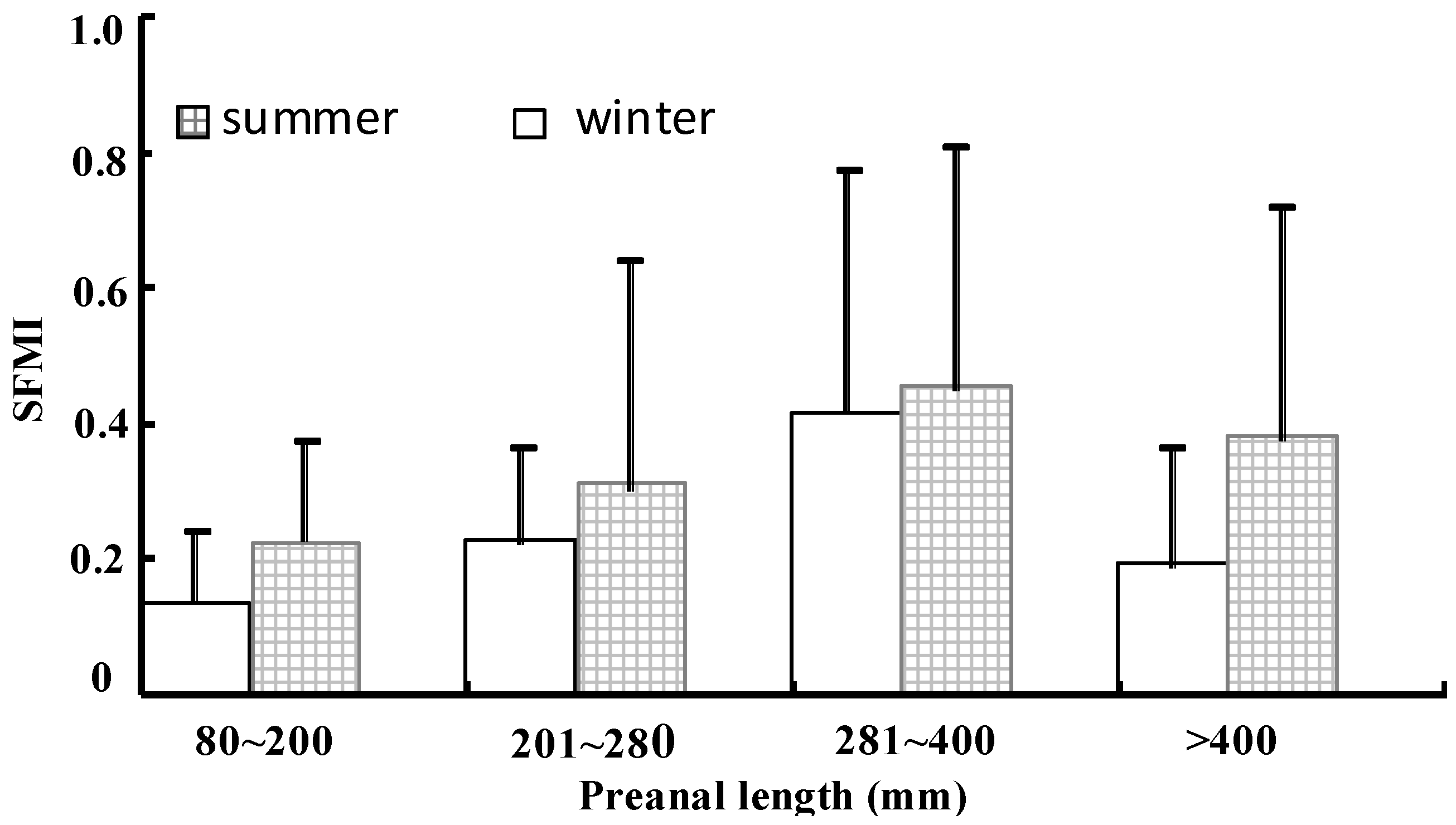

3.4. East China Sea (T. japonicas and T. nanhaiens)

3.5. South China Sea (T. nanhaiens and T. brevis)

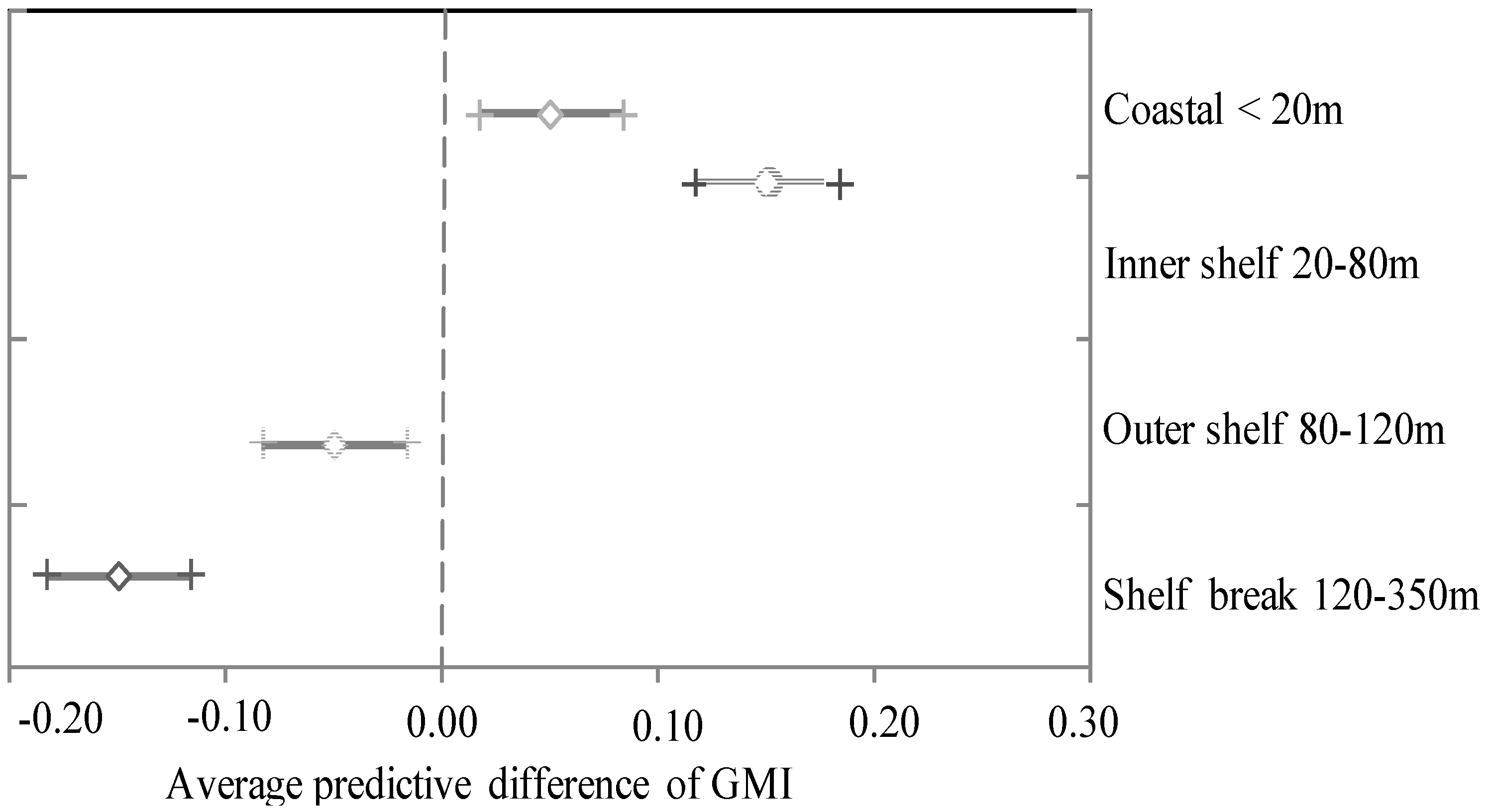

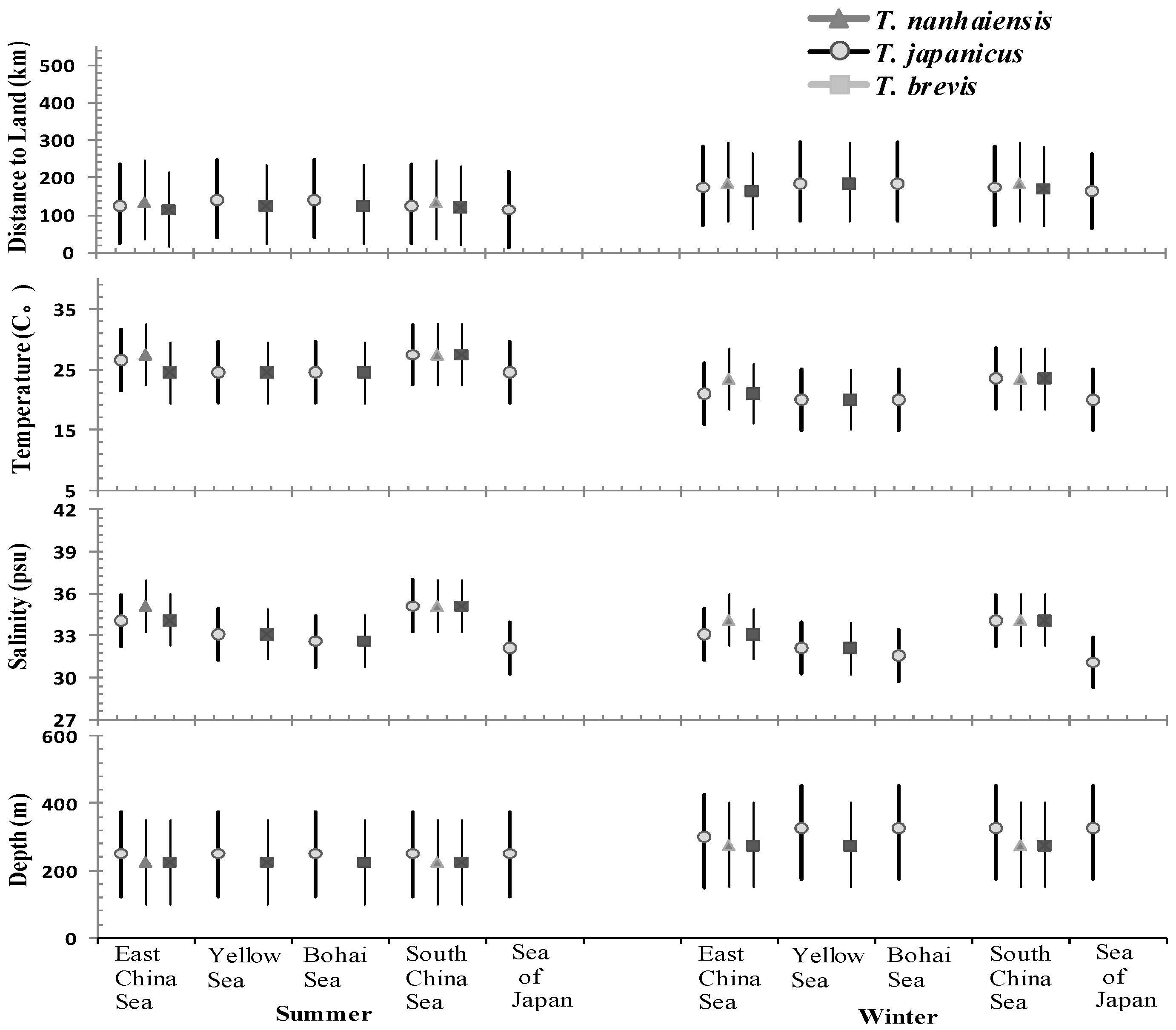

3.6. Distributions, Prey Groups, and Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity

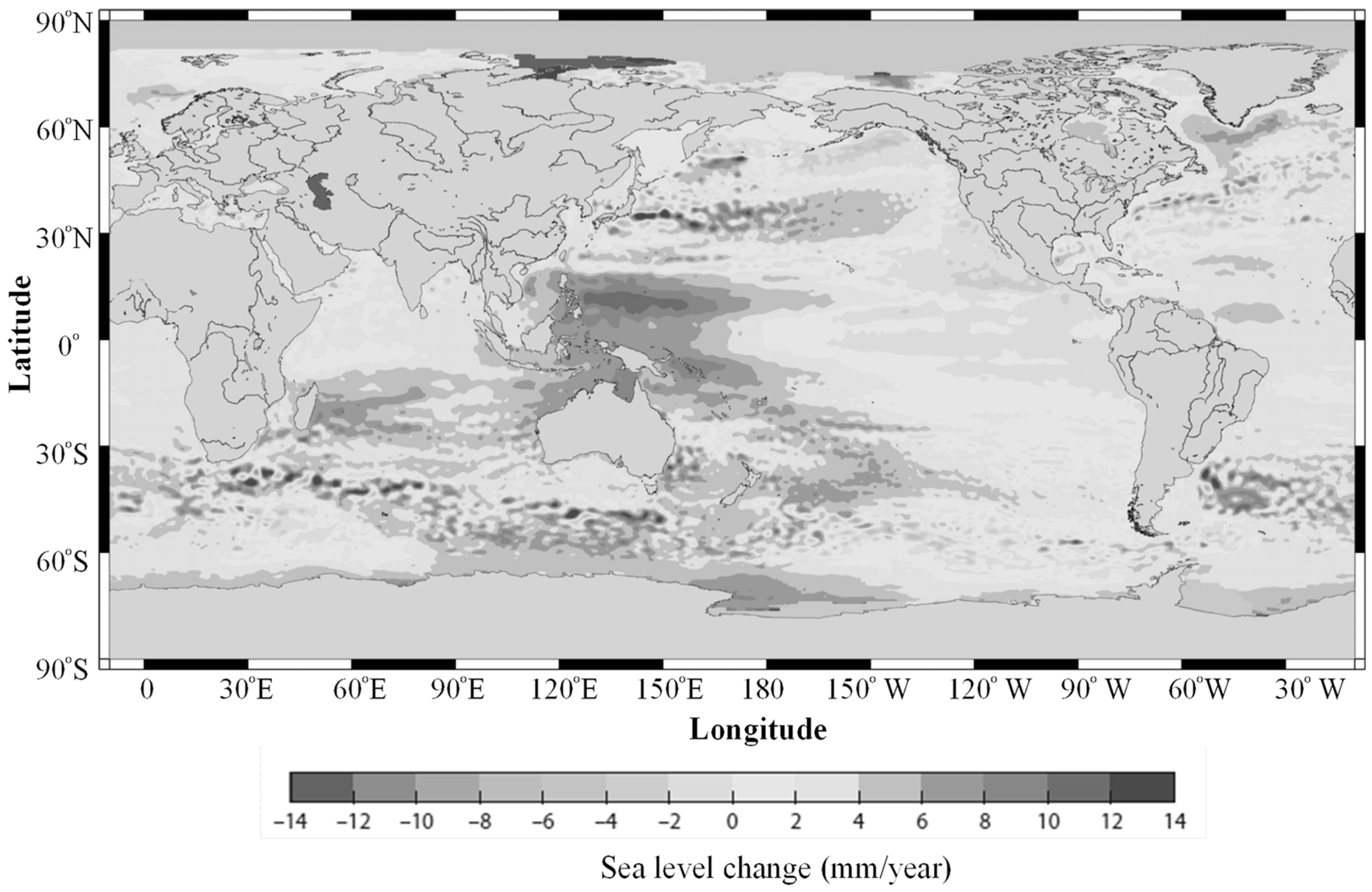

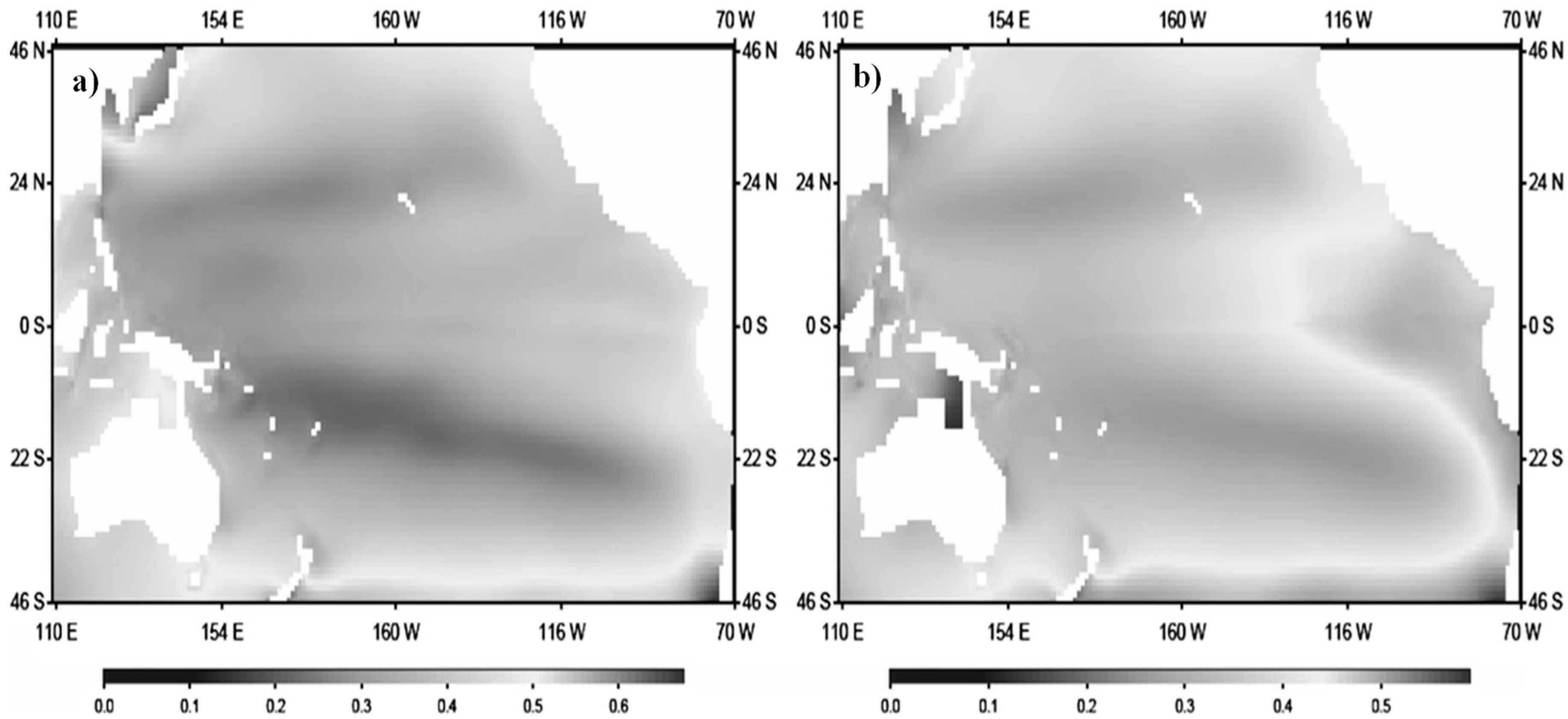

3.7. Coupling Phytoplankton Production and Physical Transport

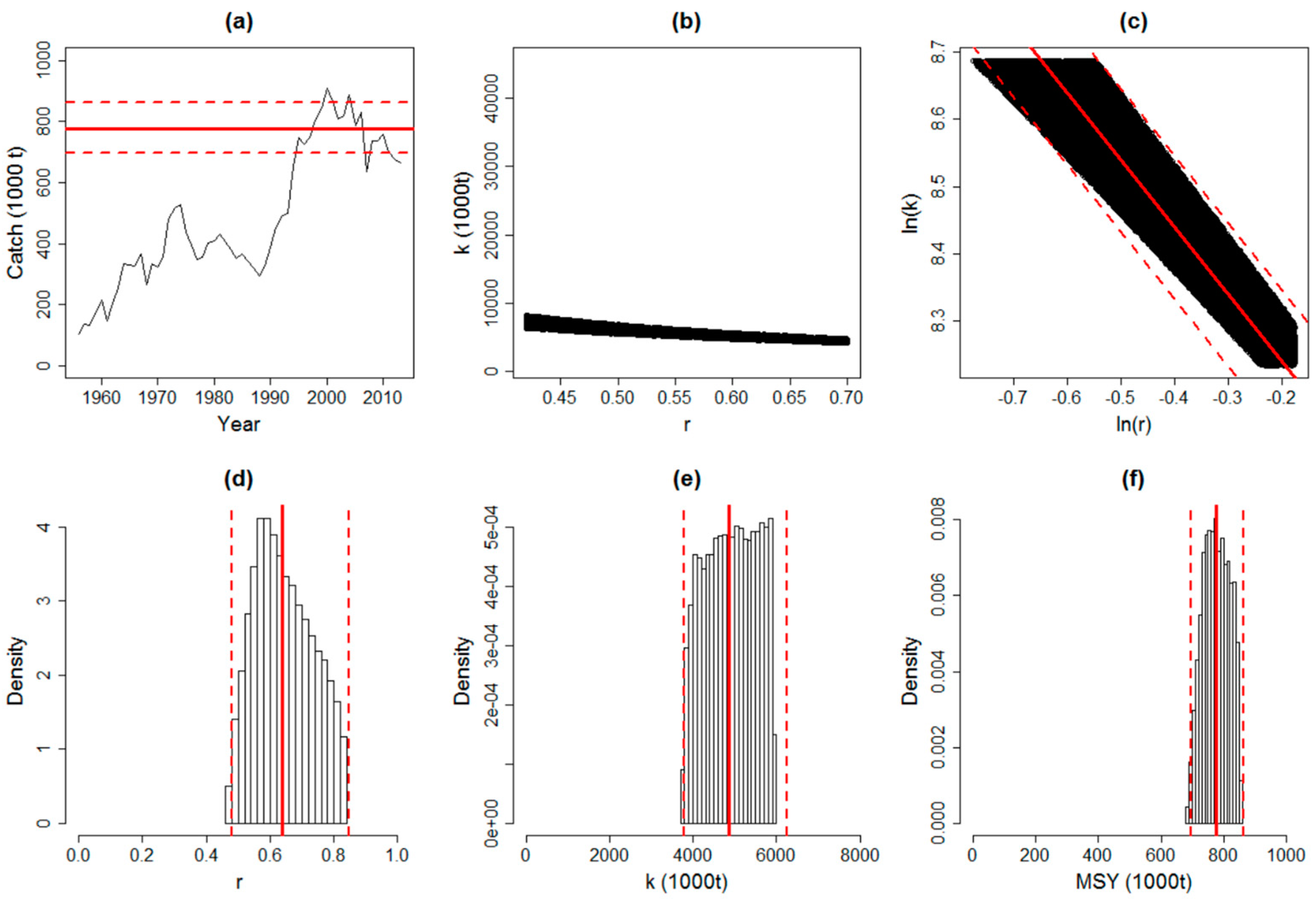

3.8. Framework of Assessment and Impacts on Ecosystems

3.9. Heterogeneity and Localization Considered

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Acknowledgments

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- Levin SA (1976) Population dynamic models in heterogeneous environments. Annu Rev Ecol Evol S 1(1): 287–310.

- Fahrig L (1992) Relative importance of spatial and temporal scales in a patchy environment. Theor popul biol 41(3): 300–314. [CrossRef]

- Bascompte J Rodríguez MA (2000) Self-disturbance as a source of spatiotemporal heterogeneity: the case of the tallgrass prairie. J Theor Biol 204(2): 153–164. [CrossRef]

- Poff NL, Ward JV (1990) Physical habitat template of lotic systems: recovery in the context of historical pattern of spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Environ Manage 14(5):629–645. [CrossRef]

- Schanze J J, Schmitt R W. (2013). Estimates of cabbeling in the global ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 43:698–705. [CrossRef]

- Abril A, Villagra P, Noe L (2009) Spatiotemporal heterogeneity of soil fertility in the Central Monte desert (Argentina). J Arid Environ 73(10): 901–906. [CrossRef]

- Brown TM, Piggins HD (2009) Spatiotemporal heterogeneity in the electrical activity of suprachiasmatic nuclei neurons and their response to photoperiod. J Biol Rhythm 24(1): 44–54. [CrossRef]

- Zobel M (1997) The relative of species pools in determining plant species richness: an alternative explanation of species coexistence. Trends Ecol Evol 12(7): 266–269. [CrossRef]

- Burhanuddin AI, Iwatsuki Y, Yoshino T, Kimura S (2002) Small and valid species of Trichiurus brevis Wang and You, 1992 and T. russelli Dutt and Thankam, 1966, defined as the “T. russelli complex” (Perciformes: Trichiuridae). Ichthyol Res 49(3): 211–223. [CrossRef]

- Cheung WW, Pitcher TJ, Pauly D (2005) A fuzzy logic expert system to estimate intrinsic extinction vulnerabilities of marine fishes to fishing. Biol Conserve 124(1): 97–111. [CrossRef]

- He L, Zhang A, Weese D, Li S, Li J, Zhang J (2014) Demographic response of Cutlassfish (Trichiurus japonicus and T. nanhaiensis) to fluctuating palaeo-climate and regional oceanographic conditions in the China seas. Sci Rep-UK 4(1): 6380–6392. [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan A (2016) The Impact of Submesoscale Physics on Primary Productivity of Plankton. Annu Rev Mar Sci 8: 161–184. [CrossRef]

- Froese R, Pauly D (1997) FishBase—a biological database on fish (software). ICLARM, Manila.

- Zeng ZX (2005) Specific morphological and genetic variations of Cutlassfish (Trichiurus spp.) (In Chinses), National Taiwan University Thesis, pp 1–64.

- El-Haweet AED, Ozawa T (1996) Age and growth of Ribbon fish Trichiurus japonicus in Kagoshima bay, Japan. Fisheries Sci 62(4): 529–533.

- Kwok KY, Ni IH (1999) Reproduction of Cutlassfishes Trichiurus spp. from the South China Sea. Mar Ecol-Prog Ser 176(1): 39–47.

- Shih HH (2004) Parasitic helminth fauna of the cutlass fish, Trichiurus lepturus L., and the differentiation of four anisakid nematode third-stage larvae by nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Parasitol Res 93(3): 188–195. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Cheng J, Chen Y (2009) A spatial analysis of trophic composition: a case study of hairtail (Trichiurus japonicus) in the East China Sea. Hydrobiologia 632(1): 79-90. [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Zhang B, Xue Y (2010) The response of the diets of four carnivorous fishes to variations in the Yellow Sea ecosystem. Deep-Sea Res PT II 57(11): 996–1000. [CrossRef]

- Wang K, Xu C (1992) Studies on the genetic variation and systematics of the hairtail fishes from the South China Sea (In Chinese with English abstract). Acta Oceanol Sin 2: 69–72.

- Chakraborty A, Aranishi F, Iwatsuki Y (2006) Genetic differentiation of Trichiurus japonicus and T. lepturus (Perciformes: Trichiuridae) based on mitochondrial DNA analysis. Zoological Studies Taipei 45(3): 419–424.

- Kwok KY, Ni IH (2000) Age and growth of Cutlassfishes, Trichiurus spp., from the South China Sea. Fish B-NOAA 98(4): 748–758.

- Liu SL (1996) Compilation of the statistics of Chinese fishery (1989–1993). Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture, the People’s Republic China (in Chinese). China Ocean Press, Beijing.

- Tang Q, Jin X, Wang J, Zhuang Z, Cui Y, Meng T (2003) Decadal-scale variations of ecosystem productivity and control mechanisms in the Bohai Sea. Fish Oceanogr 12(4): 223–233. [CrossRef]

- Martins AS, Haimovici M (1997) Distribution, abundance and biological interactions of the Cutlassfish Trichiurus lepturus in the southern Brazil subtropical convergence ecosystem. Fish Res 30:217–227. [CrossRef]

- Jin X (2004) Long-term changes in fish community structure in the Bohai Sea, China. Estuar Coast Shelf S 59(1): 163–171. [CrossRef]

- Bjørnstad ON, Grenfell BT (2001) Noisy clockwork: time series analysis of population fluctuations in animals. Science 293(5530): 638–643. [CrossRef]

- Lin L, Zhang H, Li H, Cheng J (2006a) Study on seasonal variation of the feeding habits of hairtail (Trichiurus japonicus) in the East China Sea (in Chinese with English abstract). J Ocean U China 36(6): 932–936.

- DeWoody YD, Feng Z, Swihart RK (2005) Merging spatial and temporal structure within a metapopulation model. Am Nat 166(1): 42–55. [CrossRef]

- Lehodey P, Senina I, Murtugudde R (2008) A spatial ecosystem and populations dynamics model (SEAPODYM) –Modeling of tuna and tuna-like populations. Prog Oceanogr 78(4): 304–318. [CrossRef]

- Lin L, Zheng Y, Cheng J, Liu Y, Ling J (2006b) A preliminary study on fishery biology of main commercial fishes surveyed from the bottom trawl fisheries in the East China Sea (in Chinese with English abstract). Acta Oceanol Sin 2: 4–11.

- Xu D, Feng Z, Allen LJ, Swihart RK (2006) A spatially structured metapopulation model with patch dynamics. J Theor Biol 239(4): 469–481. [CrossRef]

- Lehodey P, Alheit J, Barange M, Baumgartner T, Beaugrand G., Drinkwater K., ... & Werner F (2006) Climate variability, fish, and fisheries. J Climate 19(20): 5009–5030. [CrossRef]

- Schirripa MJ, Lehodey P, Prince E, Luo J (2011) Habitat modeling of Atlantic blue marlin with SEAPODYM and satellite tags. Collect Vol Sci Pap-ICCAT 66(4): 1735–1737.

- Kendall BE, Fox GA (1998) Spatial structure, environmental heterogeneity, and population dynamics: analysis of the coupled logistic map. Theor Populn Biol 54(1): 11–37. [CrossRef]

- Guo LB, Gifford RM (2002) Soil carbon stocks and land use change: a meta-analysis. Global Change Biol 8(4): 345–360. [CrossRef]

- Don A, Schumacher J, Freibauer A (2011) Impact of tropical land-use change on soil organic carbon stocks–a meta-analysis. Global Change Biol 17(4): 1658–1670. [CrossRef]

- Van Wynsberge S, Andréfouët S, Gaertner-Mazouni N, Wabnitz CC, Gilbert A, Remoissenet G, ... Fauvelot C (2015) Drivers of density for the exploited giant clam Tridacna maxima: a meta-analysis. Fish Fish. [CrossRef]

- Vollset KW, Krontveit RI, Jansen PA, Finstad B, Barlaup BT, Skilbrei OT, ... Dohoo I (2015) Impacts of parasites on marine survival of Atlantic salmon: a meta-analysis. Fish Fish. [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Deng J (1999) Variations in community structure of fishery resources and biodiversity in the Laizhou Bay, Shandong. Chinese Biodiversity 8(1): 65–72. [CrossRef]

- Cheung WW, Pitcher TJ (2008) Evaluating the status of exploited taxa in the northern South China Sea using intrinsic vulnerability and spatially explicit catch-per-unit-effort data. Fish Res 92(1): 28–40. [CrossRef]

- Wang XH, Qiu YS, Zhu GP, Du FY, Sun DR, Huang SL (2011a) Length-weight relationships of 69 fish species in the Beibu Gulf, northern South China Sea. J Appl Ichthyol 27(3): 959–961. [CrossRef]

- Qiu Y, Lin Z, Wang Y (2010) Responses of fish production to fishing and climate variability in the northern South China Sea. Prog Oceanogr 85(3):197–212. [CrossRef]

- Martell S, Froese R (2014). A simple method for estimating MSY from catch and resilience. Fish & Fisheries, 14(4), 504–514. [CrossRef]

- Jiao Y, Lapointe NW, Angermeier PL, Murphy BR (2009b) Hierarchical demographic approaches for assessing invasion dynamics of non-indigenous species: an example using northern snakehead (Channa argus). Ecol Model 220(13): 1681–1689.

- Department of Fishery (DOF) (2012) Compilation of the statistics of Chinese fishery (1950-2012). Ministry of Agriculture, China Ocean Press, Beijing.

- Zheng YJ, Chen XZ, Cheng JH, Wang YL, Shen XQ, Chen WZ, Li CS (2003) The biological resources and environment in continental shelf of the East China Sea. Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers, Shanghai, China.

- Okamoto DK, Schmitt RJ, Holbrook SJ, Reed DC (2012) Fluctuations in food supply drive recruitment variation in a marine fish. P Roy Soc Lond B: Bio rspb20121862. [CrossRef]

- Kim JY, Kang YS, Oh HJ, Suh YS, Hwang JD (2005) Spatial distribution of early life stages of anchovy (Engraulis japonicus) and hairtail (Trichiurus lepturus) and their relationship with oceanographic features of the East China Sea during the 1997–1998 El Niño Event. Estuar Coast Shelf S 63(1): 13-21. [CrossRef]

- Woolrich MW, Behrens TE (2006) Variational Bayes inference of spatial mixture models for segmentation. IEEE T Med Imaging 25(10):1380–1391. [CrossRef]

- Yan Y, Hou G., Chen J, Lu H, Jin X (2011) Feeding ecology of hairtail Trichiurus margarites and largehead hairtail Trichiurus lepturus in the Beibu Gulf, the South China Sea. Chin J Oceanol Limnol 29:174–183. [CrossRef]

- Xu S, Jia G, Deng W, Wei G, Chen W, Huh CA (2014) Carbon isotopic disequilibrium between seawater and air in the coastal Northern South China Sea over the past century. Estuar Coast Shelf S 149(1): 38–45. [CrossRef]

- Chiou WD, Chen CY, Wang C M, Chen CT (2006) Food and feeding habits of ribbonfish Trichiurus lepturus in coastal waters of south-western Taiwan. Fisheries Sci 72(2): 373–381. [CrossRef]

- Qiu Y, Wang Y, Chen Z (2008) Runoff-and monsoon-driven variability of fish production in East China Seas. Estuar Coast Shelf S 77(1):23–34. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh HY, Lo WT, Wu LJ (2012) Community structure of larval fishes from the southeastern Taiwan Strait: linked to seasonal monsoon-driven currents. Zool Stud 51(5): 679–691.

- Li Y (2012) Change of Catch of Trichiurus haumela and its Reasons in Bo Sea and Yellow Sea since Ming and Qing Dynasty (in Chinese). Science and Management 1(1): 11– 16.

- Engen S, Lande R, Sæther BE (2002) Migration and spatiotemporal variation in population dynamics in a heterogeneous environment. Ecology 83(2): 570–579. [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Tang Q (1996) Changes in fish species diversity and dominant species composition in the Yellow Sea. Fish Res 26(3): 337–352. [CrossRef]

- Pitcher TJ, Cheung WW (2013) Fisheries: Hope or despair. Mar Pollut Bull 74(2):506–516. [CrossRef]

- Walther G, Post E, Convey P, Menzel A, Parmesan C, Beebee T, ... Bairlein F (2002) Ecological responses to recent climate change. Nature 416(6879): 389–395. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Holmes J, Teo SL (2014) A study on relationships between large-scale climate indices and estimates of North Pacific albacore tuna productivity. Fish Oceanogr 23(5): 409–416. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura I, Parin NV (1993) FAO species catalogue v. 15: snake mackerels and Cutlassfishes of the world (families Gempylidae and Trichiuridae). An annotated and illustrated catalogue of the Snake Mackerels, Snoeks, Escolars, Gemfishes, Sackfishes, Domine, Oilfish, Cutlassfishes, Scabbardfishes, Hairtails and Frostfishes known to date. FAO Fish. Synop 125(15):136–141.

- Chen Y, Jiao Y, Chen L (2003) Developing robust frequentist and Bayesian fish stock assessment methods. Fish Fish 4(2): 105–120. [CrossRef]

- Cemgil AT, Févotte C, Godsill SJ (2007) Variational and stochastic inference for Bayesian source separation. Digit Signal Process 17(5): 891–913. [CrossRef]

- Wang YZ, Jia XP, Lin ZJ, Sun DR (2011b) Responses of Trichiurus japonicus catches to fishing and climate variability in the East China Sea. J Fish China 35(12): 1881–1889.

- Sanvicente-Añorve L, Flores-Coto C, Chiappa-Carrara X (2000) Temporal and spatial scales of ichthyoplankton distribution in the southern Gulf of Mexico. Estuar Coast Shelf S 51(4):463–475. [CrossRef]

- Liao B, Liu Q, Wang X, Zhang K, Zhang J, Memon K H, Kalhoro MA (2016) Asymptotic behavior of an n-species stochastic Gilpin–Ayala cooperative model. Stoch EnvRes Risk A 30(1): 39–45. [CrossRef]

- Liao XX, Li J (1997) Stability in Gilpin-Ayala competition models with diffusion. Nonlinear Anal-Theor 28(10):1751–1758. [CrossRef]

- Kuussaari M, Heikkinen RK, Heliölä J, Luoto M, Mayer M, Rytteri S, von Bagh P (2015) Successful translocation of the threatened Clouded Apollo butterfly (Parnassius mnemosyne) and metapopulation establishment in southern Finland. Biol Conserve 190(1): 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Makino M, Sakurai Y (2012) Adaptation to climate-change effects on fisheries in the Shiretoko World Natural Heritage area, Japan. ICES J Mar Sci fss098.

- Hsieh CH, Chiu T S (2004) Summer spatial distribution of copepods and fish larvae in relation to hydrography in the northern Taiwan Strait. Zool Stud 41(1): 100–114.

- Daoji L, Daler D (2004) Ocean pollution from land-based sources: East China Sea, China. AMBIO: J Hum Environ 33(1): 107–113.

- Shan X, Jin X, Yuan W (2010) Fish assemblage structure in the hypoxic zone in the Changjiang (Yangtze River) estuary and its adjacent waters. Chin J Oceanol Limnol 28: 459–469. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Jiao Y (2015) Evaluation of stocking strategies for endangered white abalone using a hierarchical demographic model. Ecol Model, 299:14–22. [CrossRef]

- Jiao Y (2009) Regime shift in marine ecosystems and implications for fisheries management, a review. Rev Fish Biol Fisher 19(2): 177–191. [CrossRef]

| Valid Name | Scientific name (by Authors) |

Distribution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trichiurus japonicas | T. lepturus (Linnaeus,1758) | Circumtropical and temperate waters (e.g. ECS, BH, YS, and the Seas of Japan/East Sea ) | El-Haweet, 1996 Shih, 2004 Zeng 2005 Liu et al 2009 Jin et al. 2010 |

| T. lepturus japonicas (Temmick&Schlegel,1844) | |||

| T. japonicas (Temmick&Schlegel,1844) | |||

| T. japanicus (Temmick&Schlegel,1844) | |||

|

Trichiurus brevis |

T. minor (Wang et al. 1993) | Northwest Pacific (e.g. ECS, SCS) | Wang et al. 1993 Zeng 2005 |

| T. brevis (Wang & You, 1992) | |||

|

Trichiurus nanhaiensis |

T. lepturus (Chakraborty et al. 2006) T. nanhaiensis (Wang & Xu, 1992) |

West Pacific (northwest SCS) | Wang& Xu, 1992 Kwok & Ni, 2000 |

| Trichiurus | Trichiurus | Trichiurus | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| japonicas | nanhaiensis | brevis | ||

| East China Sea | κ=(0.27, 0.46) yr−1 | κ=(0.17, 0.22) yr−1 | κ=(0.11, 0.17) yr−1 | Shih et al. 2011 |

| W∞=(1911.3, 1950.2)g | W∞=(2998.8, 3144.4)g | W∞=(2685.4, 2871.4)g | Lin et al. 2006b | |

| Lam=(43.2, 46.3) cm | Lam=(45.7, 54.9) cm | Lam=(38.7, 41.6) cm | Tzeng et al. 2007 | |

| PL∞=(54.1, 85.1)cm | PL∞=(60.1, 89.1)cm | PL∞=(42.3, 49.8)cm | - | |

| t0 =(-1.762, -0.634) | t0 =(-1.762, -0.634) | t0 =(-1.762, -0.634) | Shih et al. 2011 | |

| a=(0.00032, 0.00054) | a=(0.00032, 0.00054) | a=(0.00079, 0.00481) | - | |

| b=(3.06, 3.22) | b=(3.06, 3.22) | b=(2.92, 3.32) | - | |

| South China Sea | κ=(0.17, 0.22) yr−1 | κ=(0.11, 0.17) yr−1 | Shih et al. 2011 | |

| W∞=(2998.8, 3144.4)g | W∞=(2685.4, 2871.4)g | Kwok & Ni, 2000 | ||

| Lam=(45.7, 54.9) cm | Lam=(38.7, 41.6) cm | - | ||

| PL∞=(60.1, 89.1)cm | PL∞=(42.3, 49.8)cm | Shih et al. 2011 | ||

| t0 =(-1.762, -0.634) | t0 =(-1.762, -0.634) | - | ||

| a=(0.00032, 0.00054) | a=(0.00079, 0.00481) | Wang et al. 2011a | ||

| b=(3.06, 3.22) | b=(2.92, 3.32) | - | ||

| Yellow Sea & Bohai Sea | κ=(0.27, 0.46) yr−1 | Shih et al. 2011 | ||

| W∞=(1961.3, 1989.2)g | Lin et al. 2006b | |||

| Lam=(43.5, 46.8) cm | Tzeng et al. 2007 | |||

| PL∞=(55.2, 86.9)cm | - | |||

| t0 =(-1.762, -0.634) | Shih et al. 2011 | |||

| a=(0.00032, 0.00054) | - | |||

| b=(3.06, 3.22) | - | |||

| Sea of Japan | κ=(0.17, 0.22) yr−1 | Shih et al. 2011 | ||

| W∞=(1891.6, 1918.5)g | Lin et al. 2006b | |||

| Lam=(41.3, 42.6) cm | El-Haweet & Ozawa, 1996 | |||

| PL∞=(50.2, 86.3)cm | - | |||

| t0 =(-1.975, -1.791) | Shih et al. 2011 | |||

| a=(0.00032, 0.00054) | - | |||

| b=(3.06, 3.22) | - |

| Summary | Regional scales |

Feeding area |

Prey composition |

|---|---|---|---|

|

BH & YS (T. japonicas) |

35°N-45°N and 117°E-123°E |

Few high abundance area (Nowadays only as bycatch) |

Fishes(e.g. engraulis japonicus, apogon lineatus, T. japonicus), cephalopod (e.g. loligo japonica, sepiellamaindroni de), macrura |

|

ECS (T. japonicas) |

23°N-34°N and 117°E-131°E |

30°N-31°N and 123°E-124°E |

Pisces (e.g. T. japonicas, decapterus maruadsi), crustacea (e.g. mysidacea, stomatopoda, euphausiacea) cephalopods (e.g. abralia multihamata), urochorda. |

|

SCS (T. brevis and T. nanhaiensis) |

11°N-22°N and 109°E-117°E |

22°N-24°N and 109°E-110°E |

Fishes (e.g. Benthosema pterotum, Bregmaceros lanceolatus, Encrasicholina heteroloba, sardinella longiceps, decapterus russelli), crustaceans (e.g. acetes sp., unidentified shrimps), cephalopod (loligo sp.) |

|

Through the Korea Strait into the East Japan Sea (T. japonicas) |

31°N-40°N and 127°E-150°E |

35°N-38°N and 128°E-145°E |

Fishes(e.g. T. japonicas, engraulis japonicus, apogon lineatus), crustaceans (e.g. Euphausiids, shrimps) cephalopod (e.g. loligo japonica, sepiellamaindroni de), chaetognaths |

| Correlation Analysis | Partial correlation coefficient | Correlation coefficient (R) | P-Significance (2-tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea surface temperature (ECS) & CPUE (ECS) | 0.52 (3); 0.50 (5) | -0.67 | 0.01 | |

| Summer wind speed (ECS) & CPUE (ECS) | 0.46 (0); 0.38 (2) | -0.42 | 0.02 | |

| Winter wind speed (ECS) & CPUE (ECS) | - 0.42 (1); - 0.33 (2) | 0.41 | 0.04 | |

| Winter wind speed (YS) & CPUE (ECS) | - 0.44 (3); - 0.50 (4) | 0.47 | <0.001 | |

| Summer wind speed (YS) & CPUE (ECS) | - 0.66 (2); - 0.49 (3) | -0.45 | <0.001 | |

| Annual precipitation (ECS) & CPUE (ECS) | 0.48 (1); 0.56 (2) | -0.37 | <0.001 | |

| Factors distributions | Min | Pref Min (10th) | Pref Max (90th) | Max |

| Depth (m) | 0 | 100 | 350 | 400 |

| Temperature (C°) | 8.31 | 18.45 | 28.39 | 29.39 |

| Salinity (psu) | 22.7 | 32.27 | 35.93 | 39.36 |

| Primary Production | 0 | 488 | 1957 | 4336 |

| Distance to Land (km) | 0 | 10 | 209 | 1463 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).