Submitted:

21 September 2024

Posted:

23 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

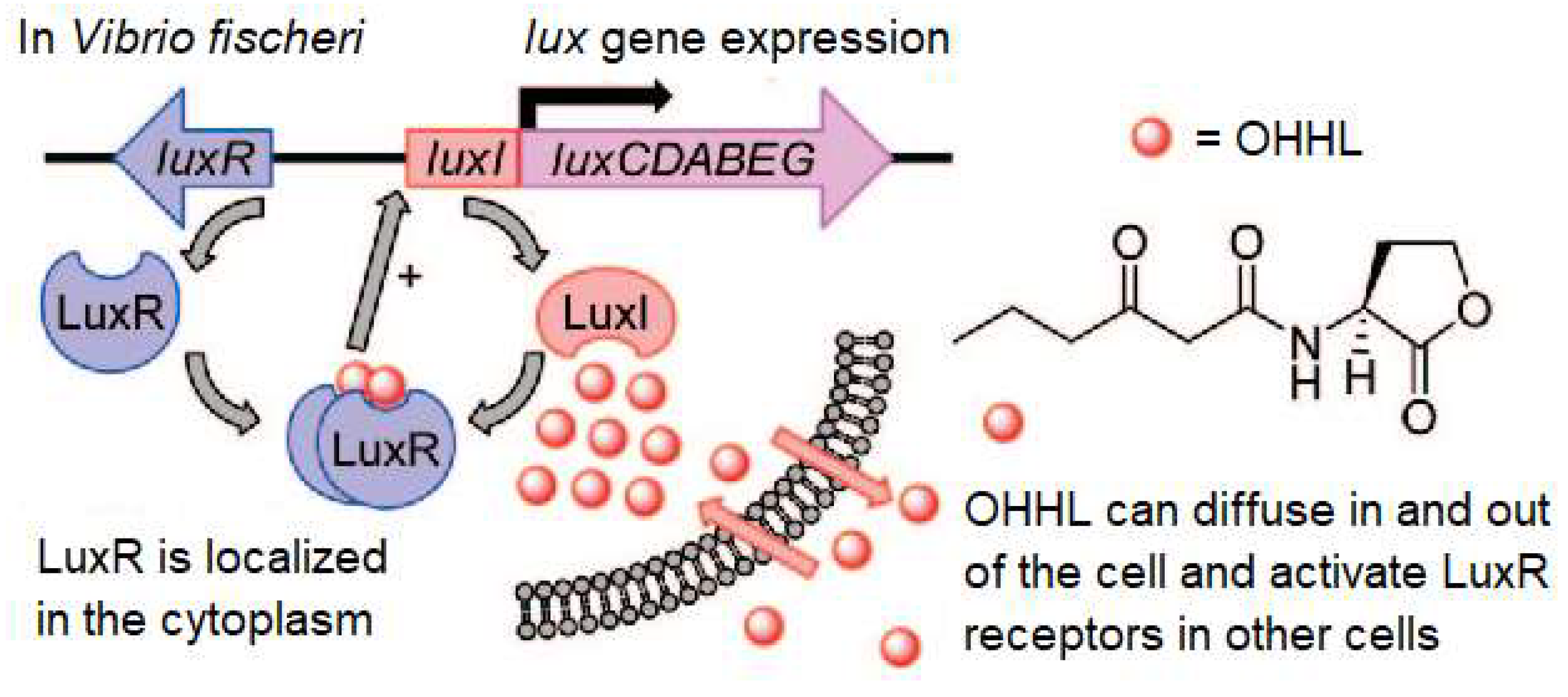

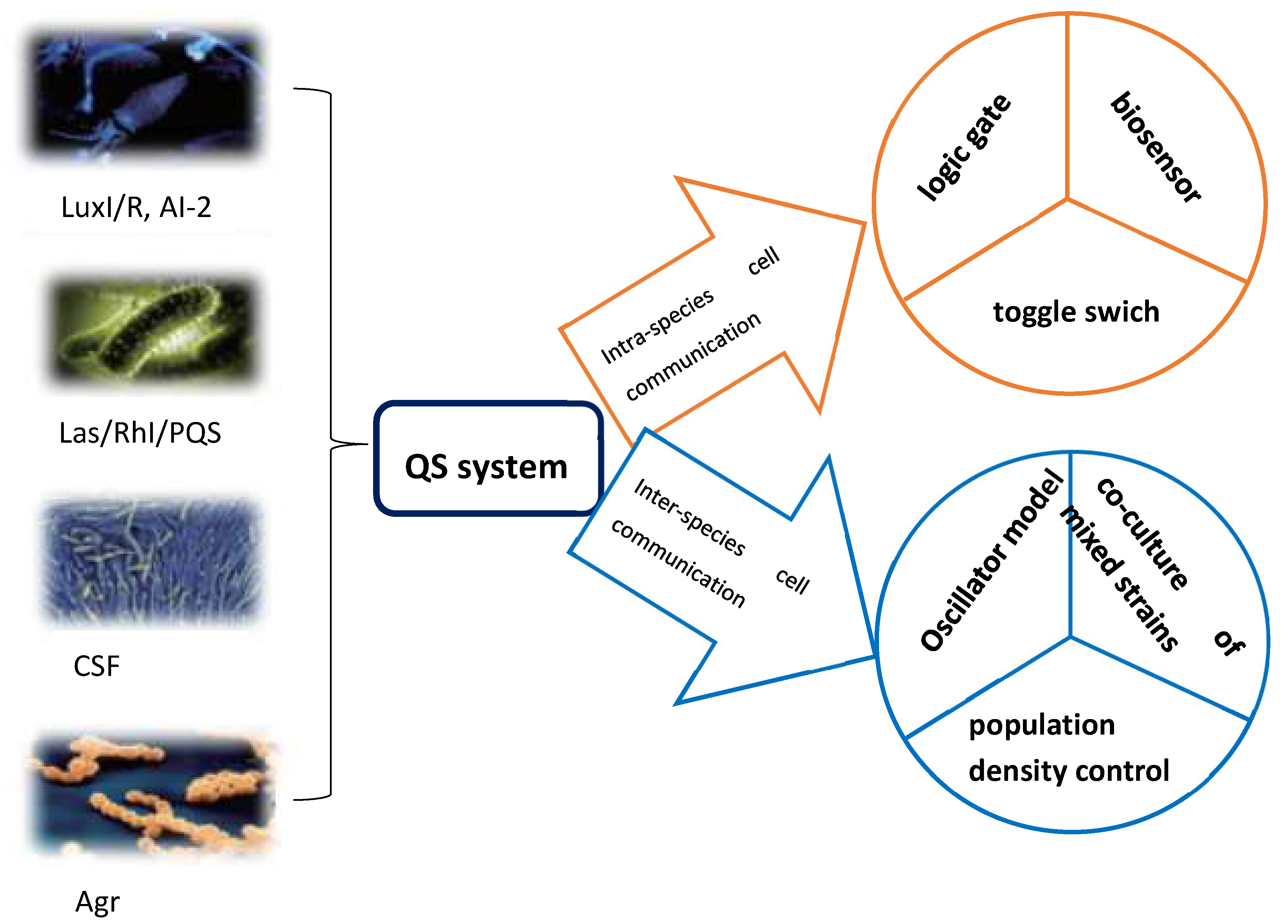

1. Quorum Sensing System of Natural Bacteria and Its Main Mechanisms

1.1. Quorum Sensing System That Regulates Bioluminescence: LuxI/R, AI-2 Quorum Sensing System

1.2. Quorum Sensing System Formed by Biofilm: Las/Rhl/Quinolone Quorum Sensing System

1.3. Quorum Sensing System for Sporulation: CSF Quorum Sensing System

1.4. Virulence-Producing Group Induction System: Agr Group Induction System

2. A Synthetic Biology Quorum Sensing Gene Circuit Involved in the Dynamic Regulation of Intracellular Communication

2.1. Toggle Switch

2.2. Biosensor

2.3. Logic Gate

3. Synthetic Biological Quorum Sensing Gene Circuit Involved in the Dynamic Regulation of Inter-Specific Cell Communication

3.1. Population Density Control

3.2. Oscillator

3.3. Co-Cultivation of Mixed Strains

Conclusion and Outlook

References

- Geethanjali, et al., Quorum sensing: A molecular cell communication in bacterial cells. Journal of Biomedical Sciences, 2019. 5(2): p. 23-34.

- Bassler, B.L., et al., Intercellular signalling in Vibrio harveyi: sequence and function of genes regulating expression of luminescence. Mol Microbiol, 1993. 9(4): p. 773-86.

- Fuqua, W.C., S.C. Winans, and E.P. Greenberg, Quorum sensing in bacteria: the LuxR-LuxI family of cell density-responsive transcriptional regulators. J Bacteriol, 1994. 176(2): p. 269-75.

- Galloway, W.R., et al., Quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria: small-molecule modulation of AHL and AI-2 quorum sensing pathways. Chem Rev, 2011. 111(1): p. 28-67.

- Choudhary, S. and C. Schmidt-Dannert, Applications of quorum sensing in biotechnology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2010. 86(5): p. 1267-79.

- Mangwani, N., et al., Bacterial quorum sensing: functional features and potential applications in biotechnology. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol, 2012. 22(4): p. 215-27.

- Bassler, B.L. and R. Losick, Bacterially speaking. Cell, 2006. 125(2): p. 237-46.

- Clinton, A. and K.P. Rumbaugh, Interspecies and interkingdom signaling via quorum signals. Israel Journal of Chemistry, 2016. 56(5): p. 265-272.

- Straight, P.D. and R. Kolter, Interspecies chemical communication in bacterial development. Annu Rev Microbiol, 2009. 63: p. 99-118.

- Goo, E., et al., Control of bacterial metabolism by quorum sensing. Trends Microbiol, 2015. 23(9): p. 567-76.

- Ryan, R.P. and J.M. Dow, Diffusible signals and interspecies communication in bacteria. Microbiology (Reading), 2008. 154(Pt 7): p. 1845-1858.

- Ng, W.-L. and B.L. Bassler, Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annual review of genetics, 2009. 43(1): p. 197-222.

- Waters, C.M. and B.L. Bassler, Quorum sensing: cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol., 2005. 21(1): p. 319-346.

- Jakobsen, T.H., et al., Targeting quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: current and emerging inhibitors. Future microbiology, 2013. 8(7): p. 901-921.

- Neelapu, N.R.R., T. Dutta, and S. Challa, Quorum sensing and its role in Agrobacterium mediated gene transfer. Implication of quorum sensing system in biofilm formation and virulence, 2018: p. 259-275.

- Atkinson, S., et al., Quorum sensing and the lifestyle of Yersinia. Current issues in molecular biology, 2006. 8(1): p. 1-10.

- Wopperer, J., et al., A quorum-quenching approach to investigate the conservation of quorum-sensing-regulated functions within the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Applied and environmental microbiology, 2006. 72(2): p. 1579-1587.

- Barnard, A.M., et al., Quorum sensing, virulence and secondary metabolite production in plant soft-rotting bacteria. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2007. 362(1483): p. 1165-1183.

- Liu, X., et al., Characterisation of two quorum sensing systems in the endophytic Serratia plymuthica strain G3: differential control of motility and biofilm formation according to life-style. BMC microbiology, 2011. 11: p. 1-12.

- Carlier, A.L., Regulation of surface polysaccharides in Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii. 2008: University of Connecticut.

- Puskas, A., et al., A quorum-sensing system in the free-living photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Journal of bacteriology, 1997. 179(23): p. 7530-7537.

- Chu, W., et al., Role of the quorum-sensing system in biofilm formation and virulence of Aeromonas hydrophila. African Journal of Microbiology Research, 2011. 5(32): p. 5819-5825.

- Patel, K., et al., Spatially propagating activation of quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri and the transition to low population density. Phys Rev E, 2020. 101(6-1): p. 062421.

- Nealson, K.H., T. Platt, and J.W. Hastings, Cellular control of the synthesis and activity of the bacterial luminescent system. J Bacteriol, 1970. 104(1): p. 313-22.

- Whiteley, M., S.P. Diggle, and E.P. Greenberg, Progress in and promise of bacterial quorum sensing research. Nature, 2017. 551(7680): p. 313-320.

- Whiteley, M., S.P. Diggle, and E.P. Greenberg, Corrigendum: Progress in and promise of bacterial quorum sensing research. Nature, 2018. 555(7694): p. 126.

- Swartzman, A., et al., A new Vibrio fischeri lux gene precedes a bidirectional termination site for the lux operon. J Bacteriol, 1990. 172(12): p. 6797-802.

- Stevens, A.M., K.M. Dolan, and E.P. Greenberg, Synergistic binding of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR transcriptional activator domain and RNA polymerase to the lux promoter region. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1994. 91(26): p. 12619-23.

- Liang, X., et al., Bifunctional Doscadenamides Activate Quorum Sensing in Gram-Negative Bacteria and Synergize with TRAIL to Induce Apoptosis in Cancer Cells. J Nat Prod, 2021.

- Chbib, C., Impact of the structure-activity relationship of AHL analogues on quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria. Bioorg Med Chem, 2020. 28(3): p. 115282.

- Nguyen, P.D.T., et al., Quorum sensing between Gram-negative bacteria responsible for methane production in a complex waste sewage sludge consortium. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2019. 103(3): p. 1485-1495.

- Qais, F.A., M.S. Khan, and I. Ahmad, Broad-spectrum quorum sensing and biofilm inhibition by green tea against gram-negative pathogenic bacteria: Deciphering the role of phytocompounds through molecular modelling. Microb Pathog, 2019. 126: p. 379-392.

- Manner, S. and A. Fallarero, Screening of Natural Product Derivatives Identifies Two Structurally Related Flavonoids as Potent Quorum Sensing Inhibitors against Gram-Negative Bacteria. Int J Mol Sci, 2018. 19(5).

- Lipa, P., M. Koziel, and M. Janczarek, [Quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria: signal molecules, inhibitors and their potential therapeutic application]. Postepy Biochem, 2017. 63(4): p. 242-260.

- Melkina, O.E., Goryanin, II, and G.B. Zavilgelsky, [Histone-like protein H-NS as a negative regulator of quorum sensing systems in gram-negative bacteria]. Genetika, 2017. 53(2): p. 165-72.

- Lemfack, M.C., et al., Novel volatiles of skin-borne bacteria inhibit the growth of Gram-positive bacteria and affect quorum-sensing controlled phenotypes of Gram-negative bacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol, 2016. 39(8): p. 503-515.

- Kong, F.D., et al., Metabolites with Gram-negative bacteria quorum sensing inhibitory activity from the marine animal endogenic fungus Penicillium sp. SCS-KFD08. Arch Pharm Res, 2017. 40(1): p. 25-31.

- Chen, Z. and J. Xiang, [Advances in the research of LuxR family protein in quorum-sensing system of gram-negative bacteria]. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi, 2016. 32(9): p. 536-8.

- Papenfort, K. and B.L. Bassler, Quorum sensing signal-response systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2016. 14(9): p. 576-88.

- Wang, D., et al., The Comparison of the Combined Toxicity between Gram-negative and Gram-positive Bacteria: a Case Study of Antibiotics and Quorum-sensing Inhibitors. Mol Inform, 2016. 35(2): p. 54-61.

- Stockli, M., et al., Coprinopsis cinerea intracellular lactonases hydrolyze quorum sensing molecules of Gram-negative bacteria. Fungal Genet Biol, 2017. 102: p. 49-62.

- Wang, D., et al., Mechanism-based QSAR Models for the Toxicity of Quorum Sensing Inhibitors to Gram-negative and Gram-positive Bacteria. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol, 2016. 97(1): p. 145-50.

- Wang, T., et al., Prediction of mixture toxicity from the hormesis of a singl`e chemical: A case study of combinations of antibiotics and quorum-sensing inhibitors with gram-negative bacteria. Chemosphere, 2016. 150: p. 159-167.

- Zhang, W. and C. Li, Exploiting Quorum Sensing Interfering Strategies in Gram-Negative Bacteria for the Enhancement of Environmental Applications. Front Microbiol, 2015. 6: p. 1535.

- Husain, F.M., et al., Sub-MICs of Mentha piperita essential oil and menthol inhibits AHL mediated quorum sensing and biofilm of Gram-negative bacteria. Front Microbiol, 2015. 6: p. 420.

- Morohoshi, T., et al., Inhibition of quorum sensing in gram-negative bacteria by alkylamine-modified cyclodextrins. J Biosci Bioeng, 2013. 116(2): p. 175-9.

- Husain, F.M. and I. Ahmad, Doxycycline interferes with quorum sensing-mediated virulence factors and biofilm formation in gram-negative bacteria. World J Microbiol Biotechnol, 2013. 29(6): p. 949-57.

- Galloway, W.R., et al., Applications of small molecule activators and inhibitors of quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends Microbiol, 2012. 20(9): p. 449-58.

- Camps, J., et al., Paraoxonases as potential antibiofilm agents: their relationship with quorum-sensing signals in Gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2011. 55(4): p. 1325-31.

- Deng, Y., et al., Listening to a new language: DSF-based quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria. Chem Rev, 2011. 111(1): p. 160-73.

- Myszka, K. and K. Czaczyk, [Quorum sensing mechanism as a factor regulating virulence of Gram-negative bacteria]. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online), 2010. 64: p. 582-9.

- Chai, H., et al., Functional properties of synthetic N-acyl-L-homoserine lactone analogs of quorum-sensing gram-negative bacteria on the growth of human oral squamous carcinoma cells. Invest New Drugs, 2012. 30(1): p. 157-63.

- Mok, K.C., N.S. Wingreen, and B.L. Bassler, Vibrio harveyi quorum sensing: a coincidence detector for two autoinducers controls gene expression. EMBO J, 2003. 22(4): p. 870-81.

- Chen, X., et al., Structural identification of a bacterial quorum-sensing signal containing boron. Nature, 2002. 415(6871): p. 545-9.

- Waters, C.M. and B.L. Bassler, The Vibrio harveyi quorum-sensing system uses shared regulatory components to discriminate between multiple autoinducers. Genes Dev, 2006. 20(19): p. 2754-67.

- Freeman, J.A. and B.L. Bassler, Sequence and function of LuxU: a two-component phosphorelay protein that regulates quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. J Bacteriol, 1999. 181(3): p. 899-906.

- Zhu, J., et al., Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2002. 99(5): p. 3129-34.

- Li, J., et al., Quorum sensing in Escherichia coli is signaled by AI-2/LsrR: effects on small RNA and biofilm architecture. Journal of bacteriology, 2007. 189(16): p. 6011-6020.

- Williams, P. and M. Camara, Quorum sensing and environmental adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a tale of regulatory networks and multifunctional signal molecules. Curr Opin Microbiol, 2009. 12(2): p. 182-91.

- Fuqua, C. and E.P. Greenberg, Self perception in bacteria: quorum sensing with acylated homoserine lactones. Curr Opin Microbiol, 1998. 1(2): p. 183-9.

- Zeng Lili, S.D., Niu Peiguang, Research progress on the quorum sensing system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its inhibitors. Antibiotics, 2014. 39(9): p. 701-705, 714.

- Singh, B.N., et al., Lagerstroemia speciosa fruit extract modulates quorum sensing-controlled virulence factor production and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology (Reading), 2012. 158(Pt 2): p. 529-538.

- Diggle, S.P., et al., 4-quinolone signalling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: old molecules, new perspectives. Int J Med Microbiol, 2006. 296(2-3): p. 83-91.

- Diggle, S.P., et al., The Pseudomonas aeruginosa 4-quinolone signal molecules HHQ and PQS play multifunctional roles in quorum sensing and iron entrapment. Chem Biol, 2007. 14(1): p. 87-96.

- Song, S.-S., et al., Plant responds to bacterial quorum-sensing system. Chinese Journal of Coll Biology, 2005.

- Parsek, M.R. and E.P. Greenberg, Acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing in gram-negative bacteria: a signaling mechanism involved in associations with higher organisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2000. 97(16): p. 8789-93.

- Schuster, M. and E.P. Greenberg, A network of networks: quorum-sensing gene regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Med Microbiol, 2006. 296(2-3): p. 73-81.

- Jia, L., Applied characters and Status of Bacillus subtilis [J]. Meat Research, 2009. 11: p. 18-21.

- Ming, H., D. Lina, and T. Qing, Advances in Application Research of Bacillus subtilis [J]. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences, 2008. 27.

- Ansaldi, M., et al., Specific activation of the Bacillus quorum-sensing systems by isoprenylated pheromone variants. Mol Microbiol, 2002. 44(6): p. 1561-73.

- Comella, N. and A.D. Grossman, Conservation of genes and processes controlled by the quorum response in bacteria: characterization of genes controlled by the quorum-sensing transcription factor ComA in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol, 2005. 57(4): p. 1159-74.

- Roggiani, M. and D. Dubnau, ComA, a phosphorylated response regulator protein of Bacillus subtilis, binds to the promoter region of srfA. J Bacteriol, 1993. 175(10): p. 3182-7.

- Bacon Schneider, K., T.M. Palmer, and A.D. Grossman, Characterization of comQ and comX, two genes required for production of ComX pheromone in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol, 2002. 184(2): p. 410-9.

- Koroglu, T.E., et al., Global regulatory systems operating in Bacilysin biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol, 2011. 20(3): p. 144-55.

- Ji, G., R.C. Beavis, and R.P. Novick, Cell density control of staphylococcal virulence mediated by an octapeptide pheromone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1995. 92(26): p. 12055-9.

- Mayville, P., et al., Structure-activity analysis of synthetic autoinducing thiolactone peptides from Staphylococcus aureus responsible for virulence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1999. 96(4): p. 1218-1223.

- Case, R.J., M. Labbate, and S. Kjelleberg, AHL-driven quorum-sensing circuits: their frequency and function among the Proteobacteria. The ISME journal, 2008. 2(4): p. 345-349.

- Srivastava, D. and C.M. Waters, A tangled web: regulatory connections between quorum sensing and cyclic di-GMP. Journal of bacteriology, 2012. 194(17): p. 4485-4493.

- Herring, C.D., J.D. Glasner, and F.R. Blattner, Gene replacement without selection: regulated suppression of amber mutations in Escherichia coli. Gene, 2003. 311: p. 153-163.

- Kim, J.Y. and H.J. Cha, Down-regulation of acetate pathway through antisense strategy in Escherichia coli: Improved foreign protein production. Biotechnology and bioengineering, 2003. 83(7): p. 841-853.

- PANG Qingxiao, L.Q., QI Qingsheng, Application of switch for synthetic biology in metabolic engineering. Biotechnology Bulletin, 2017. 33(1): p. 58-63.

- Gu, P., et al., Tunable switch mediated shikimate biosynthesis in an engineered non-auxotrophic Escherichia coli. Sci Rep, 2016. 6: p. 29745.

- Chen, Y.F., et al., Quorum sensing and microbial drug resistance. Yi Chuan, 2016. 38(10): p. 881-893.

- LIANG Zhibin, C.Y., CHEN Yufan, et al., RND family efflux pump and its relationship with microbial quorum sensing system. Genetics, 2016. 38(10): p. 894-901.

- Swofford, C.A., N. Van Dessel, and N.S. Forbes, Quorum-sensing Salmonella selectively trigger protein expression within tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2015. 112(11): p. 3457-3462.

- Soma, Y. and T. Hanai, Self-induced metabolic state switching by a tunable cell density sensor for microbial isopropanol production. Metab Eng, 2015. 30: p. 7-15.

- Gupta, A., et al., Dynamic regulation of metabolic flux in engineered bacteria using a pathway-independent quorum-sensing circuit. Nature biotechnology, 2017. 35(3): p. 273.

- Doong, S.J., A. Gupta, and K.L.J. Prather, Layered dynamic regulation for improving metabolic pathway productivity in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2018. 115(12): p. 2964-2969.

- Cui, S., et al., Engineering a Bifunctional Phr60-Rap60-Spo0A Quorum-Sensing Molecular Switch for Dynamic Fine-Tuning of Menaquinone-7 Synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. ACS Synth Biol, 2019. 8(8): p. 1826-1837.

- Gu, F., et al., Quorum Sensing-Based Dual-Function Switch and Its Application in Solving Two Key Metabolic Engineering Problems. ACS Synth Biol, 2020. 9(2): p. 209-217.

- Kalia, V.C., Quorum sensing vs quorum quenching: a battle with no end in sight. 2015: Springer.

- Miller, C. and J. Gilmore, Detection of Quorum-Sensing Molecules for Pathogenic Molecules Using Cell-Based and Cell-Free Biosensors. Antibiotics (Basel), 2020. 9(5).

- Winkler, W., A. Nahvi, and R.R. Breaker, Thiamine derivatives bind messenger RNAs directly to regulate bacterial gene expression. Nature, 2002. 419(6910): p. 952-6.

- Pang, Q., et al., In vivo evolutionary engineering of riboswitch with high-threshold for N-acetylneuraminic acid production. Metab Eng, 2020. 59: p. 36-43.

- Nivens, D.E., et al., Bioluminescent bioreporter integrated circuits: potentially small, rugged and inexpensive whole-cell biosensors for remote environmental monitoring. J Appl Microbiol, 2004. 96(1): p. 33-46.

- Rawson, D.M., A.J. Willmer, and A.P. Turner, Whole-cell biosensors for environmental monitoring. Biosensors, 1989. 4(5): p. 299-311.

- Raut, N., P. Pasini, and S. Daunert, Deciphering bacterial universal language by detecting the quorum sensing signal, autoinducer-2, with a whole-cell sensing system. Anal Chem, 2013. 85(20): p. 9604-9.

- Cai, S., et al., Engineering highly sensitive whole-cell mercury biosensors based on positive feedback loops from quorum-sensing systems. Analyst, 2018. 143(3): p. 630-634.

- Thapa, A., et al. Development of a biosensor using photobacterium Spps. For the detection of environmental pollutants. in 2017 2nd International Conference on Bio-engineering for Smart Technologies (BioSMART). 2017. IEEE.

- Courbet, A., et al., Detection of pathological biomarkers in human clinical samples via amplifying genetic switches and logic gates. Sci Transl Med, 2015. 7(289): p. 289ra83.

- Pardee, K., et al., Rapid, low-cost detection of Zika virus using programmable biomolecular components. Cell, 2016. 165(5): p. 1255-1266.

- Soltani, M., et al., Reengineering cell-free protein synthesis as a biosensor: Biosensing with transcription, translation, and protein-folding. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 2018. 138: p. 165-171.

- Wen, K.Y., et al., A Cell-Free Biosensor for Detecting Quorum Sensing Molecules in P. aeruginosa-Infected Respiratory Samples. ACS Synth Biol, 2017. 6(12): p. 2293-2301.

- Nandagopal, N. and M.B. Elowitz, Synthetic biology: integrated gene circuits. science, 2011. 333(6047): p. 1244-1248.

- Shong, J. and C.H. Collins, Quorum sensing-modulated AND-gate promoters control gene expression in response to a combination of endogenous and exogenous signals. ACS synthetic biology, 2014. 3(4): p. 238-246.

- Din, M.O., et al., Interfacing gene circuits with microelectronics through engineered population dynamics. Science advances, 2020. 6(21): p. eaaz8344.

- Hasty, J., D. McMillen, and J.J. Collins, Engineered gene circuits. Nature, 2002. 420(6912): p. 224-230.

- Hu, Y., et al., Programming the quorum sensing-based AND gate in Shewanella oneidensis for logic gated-microbial fuel cells. Chemical Communications, 2015. 51(20): p. 4184-4187.

- Shong, J. and C.H. Collins, Quorum sensing-modulated AND-gate promoters control gene expression in response to a combination of endogenous and exogenous signals. ACS Synth Biol, 2014. 3(4): p. 238-46.

- He, X., et al., Autoinduced AND Gate Controls Metabolic Pathway Dynamically in Response to Microbial Communities and Cell Physiological State. ACS Synth Biol, 2017. 6(3): p. 463-470.

- Garg, N., G. Manchanda, and A. Kumar, Bacterial quorum sensing: circuits and applications. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 2014. 105(2): p. 289-305.

- Schuster, S., T. Dandekar, and D.A. Fell, Detection of elementary flux modes in biochemical networks: a promising tool for pathway analysis and metabolic engineering. Trends Biotechnol, 1999. 17(2): p. 53-60.

- Wang, Q., et al., Engineering an in vivo EP-bifido pathway in Escherichia coli for high-yield acetyl-CoA generation with low CO2 emission. Metab Eng, 2019. 51: p. 79-87.

- An, J.H., et al., Bacterial quorum sensing and metabolic slowing in a cooperative population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014. 111(41): p. 14912-7.

- Goo, E., et al., Bacterial quorum sensing, cooperativity, and anticipation of stationary-phase stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012. 109(48): p. 19775-80.

- Patidar, S.K., et al., Pelagibaca bermudensis promotes biofuel competence of Tetraselmis striata in a broad range of abiotic stressors: dynamics of quorum-sensing precursors and strategic improvement in lipid productivity. Biotechnology for biofuels, 2018. 11(1): p. 1-16.

- Kim, S., et al., Quorum sensing can be repurposed to promote information transfer between bacteria in the mammalian gut. ACS synthetic biology, 2018. 7(9): p. 2270-2281.

- Brexó, R.P. and A.d.S. Sant’Ana, Microbial interactions during sugar cane must fermentation for bioethanol production: does quorum sensing play a role? Critical reviews in biotechnology, 2018. 38(2): p. 231-244.

- Scott, S.R., et al., A stabilized microbial ecosystem of self-limiting bacteria using synthetic quorum-regulated lysis. Nature microbiology, 2017. 2(8): p. 1-9.

- Mondragon-Palomino, O., et al., Entrainment of a population of synthetic genetic oscillators. Science, 2011. 333(6047): p. 1315-1319.

- Potvin-Trottier, L., et al., Synchronous long-term oscillations in a synthetic gene circuit. Nature, 2016. 538(7626): p. 514-517.

- Tu, B.P. and S.L. McKnight, Metabolic cycles as an underlying basis of biological oscillations. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology, 2006. 7(9): p. 696-701.

- McMillen, D., et al., Synchronizing genetic relaxation oscillators by intercell signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2002. 99(2): p. 679-84.

- Hasty, J., Sensing array of radically coupled genetic biopixels. 2012, Wiley Online Library.

- Prindle, A., et al., A sensing array of radically coupled genetic ‘biopixels’. Nature, 2012. 481(7379): p. 39-44.

- Chen, Y., et al., SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY. Emergent genetic oscillations in a synthetic microbial consortium. Science, 2015. 349(6251): p. 986-9.

- Kim, J.K., et al., Long-range temporal coordination of gene expression in synthetic microbial consortia. Nat Chem Biol, 2019. 15(11): p. 1102-1109.

- Jagavati, S., et al., Cellulase production by co-culture of Trichoderma sp. and Aspergillus sp. under submerged fermentation. Dyn Biochem Process Biotechnol Mol Biol, 2012. 6(1): p. 79-83.

- Dinh, C.V., X. Chen, and K.L.J. Prather, Development of a Quorum-Sensing Based Circuit for Control of Coculture Population Composition in a Naringenin Production System. ACS Synth Biol, 2020. 9(3): p. 590-597.

- Evans, K.C., et al., Quorum-sensing control of antibiotic resistance stabilizes cooperation in Chromobacterium violaceum. ISME J, 2018. 12(5): p. 1263-1272.

- Smalley, N.E., et al., Quorum Sensing Protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa against Cheating by Other Species in a Laboratory Coculture Model. J Bacteriol, 2015. 197(19): p. 3154-9.

| Bacterial species | Regulatory gene | Signal molecule(s) | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vibrio fischeri | luxI/luxR, luxS-luxP/Q | 3-oxo-C6-HSL AI-2 |

Bioluminescence, motility | [12,13] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | lasI/lasR, rhlI/rhlR, pqsABCDE | 3-oxo-C12-HSL C4-HSL HHQ/PQS |

Virulence, motility and biofilms formation | [14] |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | traI/traR | 3-oxo-C8-HSL | Plasmid conjugation | [15] |

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis | ypsI/ypsR, ytbI/ytbR | C6-HSL, 3-oxo-C6-HSL, C8-HSL | Motility, clumping and biofilms formation | [16] |

| Burkholderia cepacia | cepI/cepR | C8-HSL | Protease synthesis | [17] |

| Erwinia carotovora | expI/expR, carI/carR | 3-oxo-C6-HSL | Antibiotic synthesis | [18] |

| Serratia plymuthica | splI/splR, spsI/spsR, sptR | 3-oxo-C6-HSL, C6-HSL, C4-HSL | Biofilms formation | [19] |

| Erwinia stewartii | esaI/esaR | 3-oxo-C6-HSL | Virulence | [20] |

| Rhizobium leguminosarum | rhiI/ rhiR | C6-HSL, C8-HSL 3-hydroxy-7-cis-C14-HSL |

Expression of rhizosphere genes | [20] |

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides | cerI/cerR | 7-cis-C14-HSL | Evacuated bacterial accumulation | [21] |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | ahyI/ahyR | C4-HSL | Biofilms formation, exoproteases | [22] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).