1. Introduction

Acute Gastric Dilation (AGD) is characterized by massive gastric distension and severe cardiovascular alterations [

1], which may occur either in isolation or accompanied by gastric volvulus (GV). This condition represents a clinical emergency, often insidious, and is typically diagnosed post-mortem, frequently without a determined etiology. Death commonly results from the rapid onset of hypovolemic shock, myocardial ischemia, cardiac arrhythmias, visceral necrosis, and electrolyte imbalances [

1].

AGD has been reported in domestic canids as one of the leading causes of clinical emergencies, death, or justification for euthanasia in this species [

2,

3]. Among captive animals, dilation with or without volvulus has been described in felids, associated with enterotoxemia [

4]; guinea pigs [

5]; ferrets [

6]; maned wolves [

7]; rabbits [

8]; and in domestic pet rats [

9]. In non-human primates, there are reports of gastric dilation following chronic drug administration, dietary restriction, accidental overfeeding, or prior anesthesia in Old World primates [

10]. However, no cases have been described in Neotropical primates.

Despite the etiopathogenesis remaining undetermined in most cases, the gas accumulation observed in AGD may be secondary to the rapid ingestion of food and/or large quantities of food, sometimes followed by physical exercise [

11]. It can also occur due to the action of fermentative bacteria or even aerophagia [

12]. Among fermentative microorganisms,

Cronobacter sakazakii (formerly

Enterobacter sakazakii), an opportunistic bacterium from the Enterobacteriaceae family, stands out. This bacterium can be present in the environment, water, and foodstuffs [

13], such as contaminated milk, fruits, and/or vegetables [

14,

15].

Given the importance of wildlife breeding programs for species conservation, it is crucial to investigate diseases that may stem from management alterations, as well as potential pathogenic microorganisms that can affect these individuals. The objective of this study is to describe the occurrence of gastric dilation syndrome in captive Neotropical non-human primates, highlighting the pathological and microbiological aspects.

2. Materials and Methods

The necropsy and histopathology records of neotropical monkeys from breeding facilities were reviewed at the Veterinary Pathology Laboratory of the Federal University of Paraíba, Brazil. Cases with a history of sudden death between 2014 and 2023 were identified and selected. Tissue samples from all organs were collected during necropsies, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and routinely processed for histopathology. Histological slides were prepared using 5 µm thick sections and stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin.

During necropsies, gastric and intestinal content samples were collected aseptically and immersed in 5 mL of Peptone Water, incubated at 37°C for 24 hours in a bacteriological incubator for microbiological isolation and typing. For microbiological processing, aliquots were transferred to 5 mL of Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) broth and Selenite Cystine broth, incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Subsequently, they were plated onto MacConkey Agar and Brilliant Green Agar, and incubated again at 37°C for 24 hours. Isolated colonies were characterized and subjected to the following biochemical tests: Citrate, Lysine Iron Agar, Sulfide-Indole-Motility Agar, Triple Sugar Iron Agar, Voges-Proskauer, Methyl Red, Urea broth, Malonate, Ornithine, Glucose, Dulcitol, Inositol, Sorbitol, Sucrose, Rhamnose, Raffinose, and Mannitol.

After isolation, the colonies underwent antimicrobial susceptibility testing using the qualitative disk diffusion method with a McFarland standard of 1.0. The antibiotics tested, belonging to different classes to assess the behavior of the strains against various mechanisms of action, were: Nalidixic Acid (30 µg), Ampicillin (10 µg), Amoxicillin + Clavulanate (20 µg), Amikacin (30 µg), Azithromycin (15 µg), Doxycycline (30 µg), Ceftiofur (30 µg), Ciprofloxacin (5 µg), Streptomycin (10 µg), Erythromycin (150 µg), Gentamicin (10 µg), Norfloxacin (10 µg), Sulfonamide (300 µg), Sulfamethoxazole + Trimethoprim (25 µg), Tetracycline (30 µg), Penicillin (10 units), and Clindamycin (2 µg).

3. Results

Four monkeys were diagnosed with acute gastric dilatation. All were adult females: one from the species Alouatta guariba and three from the species Sapajus libidinosus. The animals were housed in four different groups within the same zoo, either on small isolated islands surrounded by freshwater or in separate enclosures, with approximately 20 individuals per group. They were all kept under the same management conditions and fed a diet of mixed fruits and commercial feed, with regular deworming. There was no history of direct contact between the four affected animals, and the deaths occurred at different times of the year, suddenly and without the collection of precise clinical information.

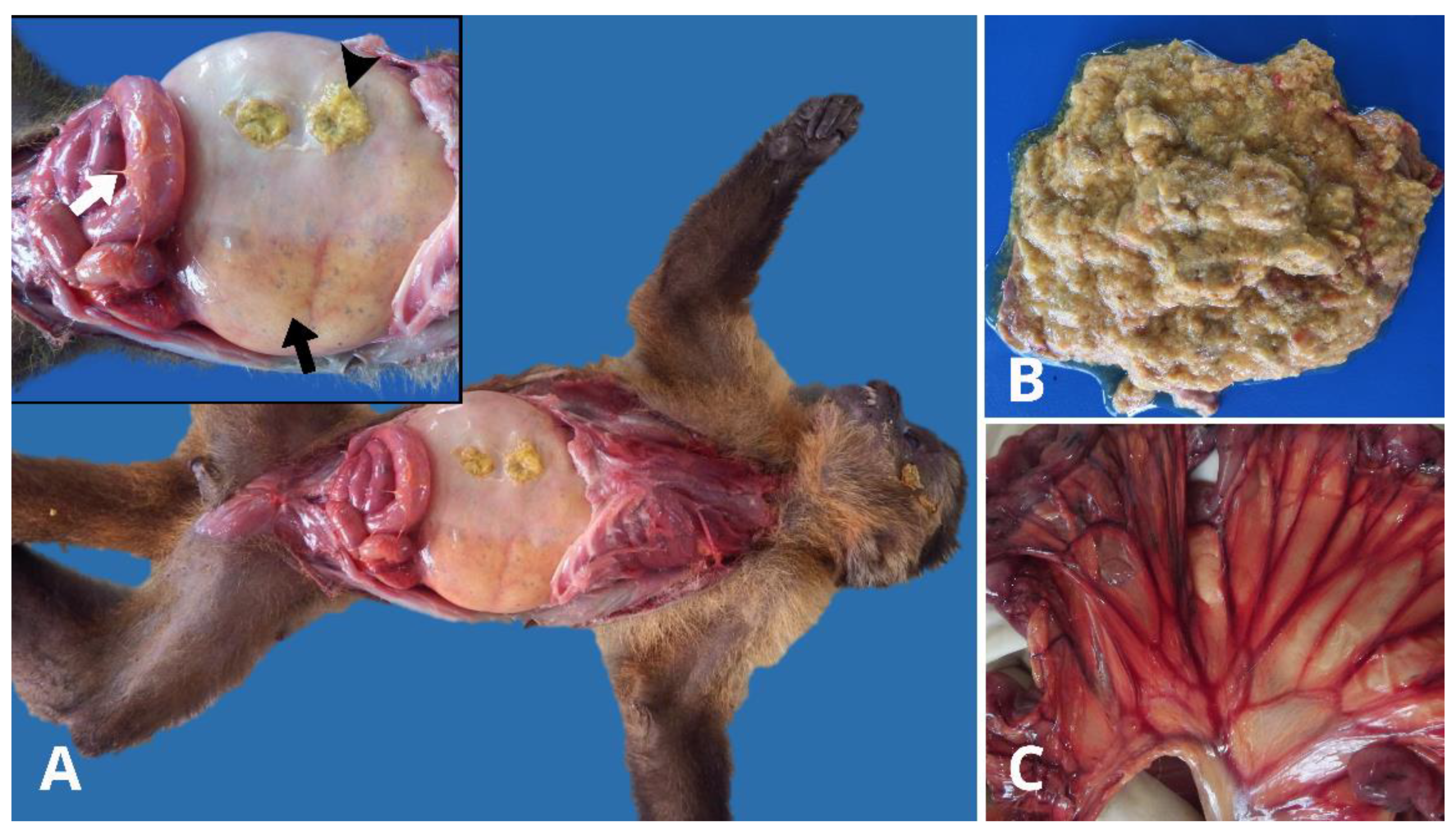

During necropsy, the animals were found to be in good body condition with no external lesions suggestive of fighting, ectoparasites, or trauma. Upon opening the abdominal cavity, a slightly reddish fluid was observed. The gastrointestinal tract showed marked stomach dilation (

Figure 1A), with a large amount of yellowish, gaseous, and pasty food content, and non-foul-smelling fluid (

Figure 1B). The duodenal loops were also dilated, with the mesenteric vascular root and mesenteric serosal vessels notably congested (

Figure 1). All spleens were enlarged with rounded edges due to congestion. No other significant macroscopic findings were observed in the other organs. Histopathological evaluation revealed mild to moderate inflammation in the intestines, composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils, confined to the lamina propria in all the animals.

Escherichia coli was isolated from the intestines and stomach of

S. libidinosus (Case 1);

Streptococcus sp. from the stomach, and

Salmonella sp.,

E. coli, and

Streptococcus sp. from the intestines of

S. libidinosus (Case 2);

Staphylococcus sp. from the stomach and Streptococcus sp. from the intestines of

A. guariba (Case 3); and

Cronobacter sakazakii from the intestines of

S. libidinosus (Case 4). The results of the biochemical battery for

C. sakazakii from the intestinal contents of

S. libidinosus are shown in

Table 1. The isolation of

C. sakazakii was confirmed based on biochemical typing, alongside its colonial characteristics, which included a rounded, glossy, matte-colored, and smooth appearance. Antibiograms were performed on all stomach/intestinal samples, and the results are displayed in

Table 2.

There was no standardization in the selection of antibiotic groups used for all the tested strains, as the cases were sent to the laboratories on an ad-hoc basis. The objective was not to characterize the strain but rather to outline a profile of the medications most available for clinical practice. Among the four antibiotics tested from the Penicillin group, sensitivity varied between active ingredients, with outcomes ranging from resistance and intermediate effect to efficacy. Of note, C. sakazakii showed sensitivity to Ampicillin. Other antibiotics to which C. sakazakii demonstrated sensitivity included Norfloxacin and Erythromycin, while resistance was observed to Penicillin and Clindamycin.

4. Discussion

The diagnosis of acute gastric dilatation in Sapajus libidinosus and Alouatta guariba was established based on necropsy findings and microbiological analysis. AGD is sporadically described in non-human Old World primates and has been attributed to chronic drug administration, food restriction, accidental overfeeding, and previous anesthesia [

10]. However, this syndrome has not yet been associated with C. sakazakii infection. The diagnosis of infection by this bacterium in primates has only been reported experimentally in Rhesus monkeys [

16].

Although well-known in canines and equines [

3,

17], the etiopathogenesis of gastric dilatation is not fully understood in primates, and in many situations, the cause remains undetermined. In the present report, it was not possible to determine the primary cause of gastric dilatation; however, it is known that the behavior of captive primates encourages competition, especially for food, with hierarchically inferior animals being the most affected, which may have favored the occurrence.

Gastric dilatation and volvulus were recently described in wild felids with enterotoxemia, and although Clostridium sp. was isolated, the authors attributed the occurrence of GDV to various factors, such as gastritis, the presence of foreign bodies in the stomach, gastrointestinal motility disorders, changes in diet (quantity and composition), as well as bacterial growth in the food [

4]. In the present study, despite the uncertain history, there were no sudden changes in the diet or management of the monkeys, and the condition was observed sporadically and individually over four years.

All monkeys died suddenly, affected by marked gastric and duodenal dilatation, indicating reflux of intestinal contents into the stomach. Duodenal reflux may occur secondary to atropine use or diets rich in lipids or proteins, which contribute to delayed gastric emptying or an increased reflux rate, leading to fermentation and gas production in the stomach [

18]. However, these factors did not play a role in the AGD observed in this study’s animals. Duodenal dilatation and chronic peritonitis were recently reported in marmosets, where five of the fourteen animals presented gastric infection without associated gastric dilatation [

19]. The authors suggested that nutritional causes might also be involved in its etiology.

In this work, C. sakazakii was detected in only one case, and despite its fermentative capacity, it is believed not to be associated with the gastric dilatation observed in the animals. The microbiota of healthy non-human primates’ intestines is mainly composed of gram-positive bacteria, with a smaller proportion of gram-negative bacteria, including Escherichia coli and Klebsiella oxytoca, while the presence of the genus Enterobacter sp. is minimal [

20], which corroborates the microbiological findings of the present study. In simian monkeys affected by AGD, for example, Clostridium perfringens was isolated and attributed as the cause, with no other agent isolated [

21].O gênero

Enterobacter contém diversos patógenos resistentes aos denominados “principais antibióticos de acesso” [

22,

23], o que pode conferir insucesso na terapêutica de alguns pacientes. O uso da ampicilina combinada com gentamicina ou cloranfenicol tem sido empregada no tratamento especialmente de infecções por

Cronobacter sp., mesmo diante da resistência desses microrganismos para essas drogas [

24]. No presente estudo observou-se sensibilidade a muitos dos antibióticos testados, incluindo a ampicilina, similar ao observado em estudos com o gênero

Enterobacter sp., isolado em

Alouatta sp. de vida livre no sudoeste Mexicano [

25].

Norfloxacin showed no resistance in our results. This drug, along with Gentamicin and Cephalosporins, has been recommended for the treatment of

C. sakazakii infections [

16]. However, resistance and ineffectiveness were observed for Gentamicin and Cephalosporins in this study. Some studies indicate resistance of

Cronobacter to multiple drugs [

26,

27], which may be attributed to strain variation, such as the ampC β-lactamase variant that confers phenotypic resistance exclusively to first-generation cephalosporins, but not to Ampicillin, for example [

28]. Although this phenotypic variation was not addressed in this study, these findings could explain the results presented here.

C. sakazakii has only been experimentally isolated in Rhesus monkeys and, to the authors’ knowledge, has not been described as causing gastrointestinal pathologies in this species, unlike in children diagnosed with enterocolitis [

15]. Contact with the pathogen occurs through the contamination of food and/or environment [

29], and in humans, it is associated with contaminated infant formulas. The presence of

C. sakazakii raises concerns, particularly regarding the pathogen’s environmental presence, which emphasizes the need for improved sanitary management to prevent contamination. The pathogen can remain viable for extended periods, up to two years in processed foods, for instance [

30].

Acute gastric dilatation should be included in the differential diagnosis of sudden death in captive non-human primates, similar to reports in captive chimpanzees associated with cardiac disorders [

31] or infectious diseases [

32,

33]. AGD must be differentiated from diseases that cause acute abdominal distention, such as reported in Rhesus monkeys due to tumor metastases [

34], which exhibited marked abdominal distension. However, the association of sudden death with the findings of gastric dilatation with pasty content, in addition to congestion of the mesenteric vessels observed at necropsy, allows the diagnosis of this syndrome.

Considering the metabolic-nutritional causes, appropriate management should be implemented, particularly in ensuring the consumption of a variety of natural fibers while avoiding large amounts of foods rich in gluten and other allergenic proteins [

35]. Despite the subtle findings and acute nature of the syndrome, it is important to monitor for early signs of AGD, such as hyperactivity or lethargy, agitation, dyspnea, abdominal rigidity, and tympany [

10], which should be investigated to prevent the death of the AGD-affected patient.

5. Conclusion

Dilatação gástrica aguda é uma causa de morte súbita em primatas não-humanos de zoológico. Os fatores predisponentes são indefinidos. No entanto, o isolamento de bacterias, principalmente do estômago, a exemplo de C. sakazakii, pode indicar a presença de patógenos no meio ambiente e/ou contato dos animais com microbiota humana. Há necessidade de cuidados específicos na alimentação de primatas não humanos, incluindo maior higienização dos alimentos e fornecimento de nutrientes adequados.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.S. and R.B.L.; methodology, M.S.S.; R.A.F.S.; N.T.A.S.; T.S.L.; K.L.S.; L.R.C.E; I.J.C.; and R.B.L.; investigation, M.S.S.; R.S.S.; H.H.L.N; K.L.S.; L.R.C.E; I.J.C.; and R.B.L.; resources, R.B.L.; M.S.S.; R.S.S.; H.H.L.N; T.S.L.; R.A.F.S. and N.T.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.S.; T.S.L.; N.T.A.S.; R.A.F.S. and R.S.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S.S.; R.S.S.; H.H.L.N; T.S.L.; N.T.A.S.; R.A.F.S.; T.F.L.N.; K.L.S.; L.R.C.E; I.J.C.; and R.B.L.; supervision, R.B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel grant number Code 001 and The APC was funded by Universidade Federal da Paraiba.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dudley, E.S.; Boivin, G.P. Gastric volvulus in guinea pigs: comparison with other species. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2011, 50, 526-530.

- Song, K.K.; Goldsmid, S.E.; Lee, J.; Simpson, D.J. Retrospective analysis of 736 cases of canine gastric dilatation volvulus. Aust. Vet. J. 2020, 98, 232-238. [CrossRef]

- Castro, N.B.; Boos, G.S.; Wurster, F.; Bassuino, D.M.; Oliveira, E.C.; Bandinelli, M.B.; Driemeier, D. Post-mortem Diagnosis of Gastric Dilatation Volvulus Syndrome in Dogs. Acta Sci. Vet. 2013, 41, 1-6.

- Anderson, K.M.; Garner, M.M.; Clyde, V.L.; Volle, K.A.; Laleggio, D.M.; Reid, S.W.; Hobbs, J.K.; Wolf, K.N. Gastric dilatation and enterotoxemia in ten captive felids. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2018, 253, 918-925. [CrossRef]

- Edis, A. Gastric dilatation volvulus in guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus). Vet. Nurs. J. 2019, 10, 156-161. [CrossRef]

- Hinton, J.D.; Aitken-Palmer, C.; Joyner, P.H.; Ware, L.; Walsh, T.F. Fatal gastric dilation in two adult black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2016, 47, 367-369. [CrossRef]

- Hinton, J.D.; Padilla, L.R.; Joyner, P.H.; Schnellbacher, R.; Walsh, T.F.; Aitken-Palmer, C. Gastric dilatation volvulus in adult maned wolves (Chrysocyon brachyurus). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2017, 48, 476-483. [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, A., & Müller, K. Radiological and laboratory prognostic parameters for gastric dilation in rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Vet. Rec. 2024. 194, no-no. [CrossRef]

- Woodhall, H., Barrow, K., Brown, S., Roe, T., & Bergen, C. (2024). Successful surgical treatment of gastric dilatation and volvulus in a pet domestic rat (Rattus norvegicus). Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine, 51, 9-12. [CrossRef]

- Pond, C.L.; Newcomer, C.E.; Anver, M.R. Acute gastric dilatation in nonhuman primates: review and case studies. Vet. Pathol. 1982, 19, 126-133.

- Gazzola, K.M.; Nelson, L.L. The relationship between gastrointestinal motility and gastric dilatation-volvulus in dogs. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2014, 29, 64-66. [CrossRef]

- Im, J. Y., Sokol, S., & Duhamel, G. E. Gastric dilatation associated with gastric colonization with Sarcina-like bacteria in a cat with chronic enteritis. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2017, 53, 321-325. [CrossRef]

- Kandhai, M.C.; Reij, M.W.; Gorris, L.G.M.; Guillaume-Gentil, O.; Van Schothorst, M. Occurrence of Enterobacter sakazakii in food production environments and households. The Lancet. 2004, 363, 39-40. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, A.B.; Braden, C.R. Invasive Enterobacter sakazakii disease in infants. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1185-1189.

- Iversen, C.; Forsythe, S. Risk profile of Enterobacter sakazakii, an emergent pathogen associated with infant milk formula. Trends. Food Sci. Technol. 2003, 14, 443-454. [CrossRef]

- WenHai, Y.; Yuan, Z.; ShuaiYao, L.; SuDong, Q.; Dong, S.; YanYan, L.; FengMei, Y.; LiXiong, C.; JunBin, W.; ZhanLong, H. Identification and sequence analysis on a Cronobacter (Enterobacter sakazakii) from rhesus monkey. Zhongguo Weishengtaxixue Zazhi/Chinese Journal of Microecology. 2014, 26, 377-381.

- Marcolongo-Pereira, C.; Estima-Silva, P.; Soares, M.P.; Sallis, E.S.V.; Grecco, F.B.; Raffi, M.B.; Fernandes, C.G.; Schild, A.L. Doenças de equinos na região Sul do Rio Grande do Sul. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2014, 34, 205-210. [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg, A.; Müller-Lissner, S.A.; Schattenmann, G.; Lepsien, G.; Hollinger, A.; Siewert, J.R.; Blum, A.L. A quantitative assessment of duodeno gastric reflux in the dog after meals and under pharmacological stimulation. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 1981, 67, 103-105.

- Mineshige, T.; Inoue, T.; Yasuda, M.; Yurimoto, T.; Kawai, K.; Sasaki, E. Novel gastrointestinal disease in common marmosets characterised by duodenal dilation: a clinical and pathological study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Carrier, C.A.; Elliott, T.B.; Ledney, G.D. Resident bacteria in a mixed population of rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) monkeys: a prevalence study. J. Med. Primatol. 2009, 38, 397-403. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, B.T.; Cuasay, L.; Welsh, T.J.; Beluhan, F.Z.; Schofield, L. Acute gastric dilatation in monkeys: a microbiology study of contentes gastric, blood and feed. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1980, 30, 241-244.

- World Health Organization- WHO. 2017. The selection and use of essential medicines: report of the WHO Expert Committee, 2017 (including the 20th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and the 6th Model List of Essential Medicines for Children). Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259481 (Accessed on: 13 April 2021).

- Davin-Regli, A.; Lavigne, J.P.; Pagès, J.M. Enterobacter spp.: update on taxonomy, clinical aspects, and emerging antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00002-19. [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.K. Enterobacter sakazakii infections among neonates, infants, children, and adults: case reports and a review of the litera-ture. Medicine. 2001, 80, 113-122. [CrossRef]

- Cristóbal-Azkarate, J.; Dunn, J.C.; Day, J.M.W.; Amábile-Cuevas, C.F. Resistance to Antibiotics of Clinical Relevance in the Fecal Microbiota of Mexican Wildlife. Plos One. 2014, 9, e107719. [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Liang, Q.; Zhan, Z.; Feng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, M.; Tong, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Yin, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, D. Co-occurrence of 3 different resistance plasmids in a multi-drug resistant Cronobacter sakazakii isolate causing neonatal infections. Virulence. 2018, 9, 110-120. [CrossRef]

- Lepuschitz, S.; Ruppitsch, W.; Pekard-Amenitsch, S.; Forsythe, S.J.; Cormican, M.; Mach, R.L.; Piérard, D.; Allerberger, F. Multi-center study of Cronobacter sakazakii infections in humans, Europe, 2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 515-522. [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Hächler, H.; Stephan, R.; Lehner, A. Presence of AmpC beta-lactamases, CSA-1, CSA-2, CMA-1, and CMA-2 conferring an unusual resistance phenotype in Cronobacter sakazakii and Cronobacter malonaticus. Microb. Drug. Resist. 2014, 20, 275-280. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Hwang, H.; Kim, K.P.; Yoon, H.; Kang, D.H.; Ryu, S. Hfq plays important roles in virulence and stress adaptation in Cronobacter sakazakii ATCC 29544. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 2089-2098. [CrossRef]

- Caubilla-Barron, J.; Hurrell, E.; Townsend, S.; Cheetham, P.; Loc-Carrillo, C.; Fayet, O.; Prère, M.-F.; Forsythe, S.J. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of Enterobacter sakazakii strains from an outbreak resulting in fatalities in a neonatal intensive care unit in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 3979-3985. [CrossRef]

- Lammey, M.L.; Lee, D.R.; Ely, J.J.; Sleeper, M.M. Sudden cardiac death in 13 captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). J. Med. Primatol. 2008, 37, 39-43. [CrossRef]

- Demetria, C.; Smith, I.; Tan, T.; Villarico, D.; Simon, E.M.; Centeno, R.; Tachedjian, M.; Taniguchi, S.; Shimojima, M.; Miranda, N.L.J.; Miranda, M.E.; Rondina, M.M.R.; Capistrano, R.; Tandoc, A.; Marsh, G.; Eagles, D.; Cruz, R.; Fukushi, S. Reemergence of Reston ebolavirus in Cynomolgus monkeys, the Philippines, 2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 1285-1291. [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Eo, K.Y.; Gumber, S.; Hong, J.J.; Kim, C.Y.; Lee, H.H.; Jung, Y.M.; Kim, J.; Whang, G.W.; Lee, J.M.; Yeo, Y.G.; Ryu, B.; Ryu, J.S.; Lee, S.K.; Kim, U.; Kang, S.G.; Park, J.H. An outbreak of toxoplasmosis in squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) in South Korea. J. Med. Primatol. 2018, 47, 238-246. [CrossRef]

- Asher, J.L.; Barnett, G.J.; Zeiss, C.J. Acute Abdominal Distension Due to Disseminated Peritoneal Neoplasia in a Rhesus Macaque (Macaca mulatta). Comp. Med. 2018, 68, 403-410. [CrossRef]

- Pastor- Nieto, R. Health and welfare of howler monkeys in captivity. In Howler monkeys: Adaptive Radiation, Systematics, and Morphology, 2015nd ed.; Kowalewski, M.M.; Garber, P.; Cortés-Ortiz, L.; Urbani, B.; Youlatos, D., Eds.; Springer, New York, NY, United States of America, 2015; pp. 313-355.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).