Submitted:

20 September 2024

Posted:

23 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pomegranate and Microencapsulation

2.2. Animals

2.3. Induction of MetS by 30% Sucrose

2.4. Measurement of Body Weight, Blood Pressure, and Biochemical Parameters

2.5. MPJ Supplementation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

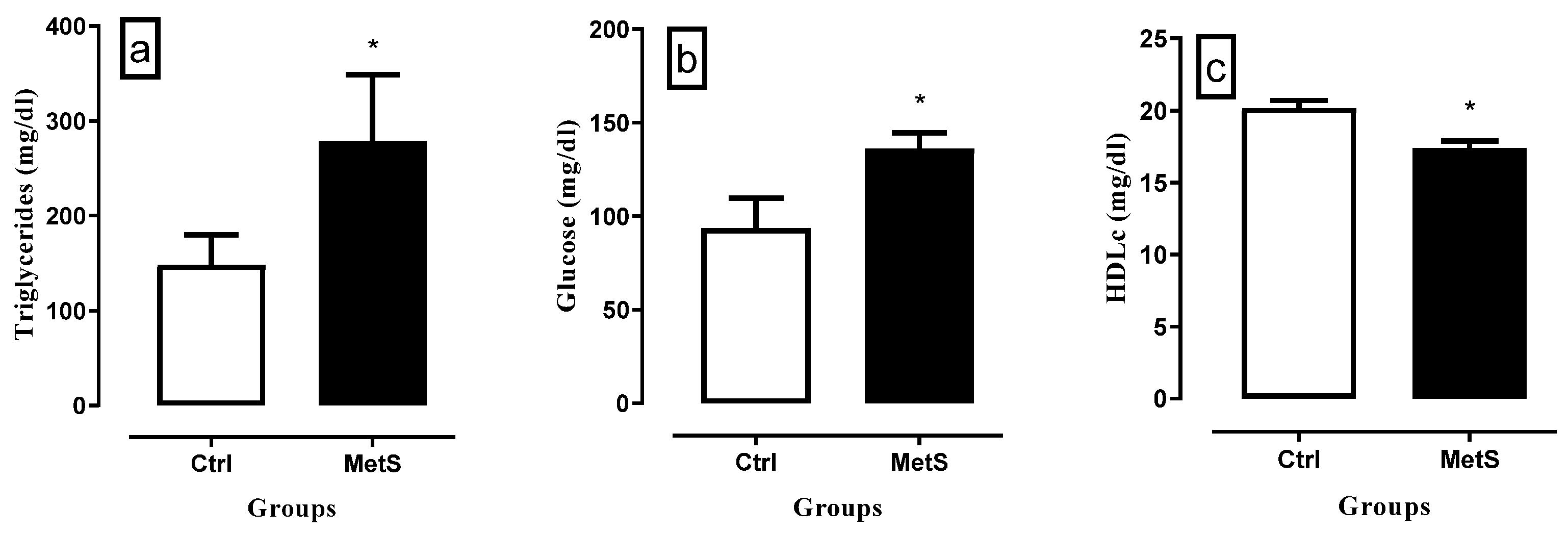

3.1. MetS Induction

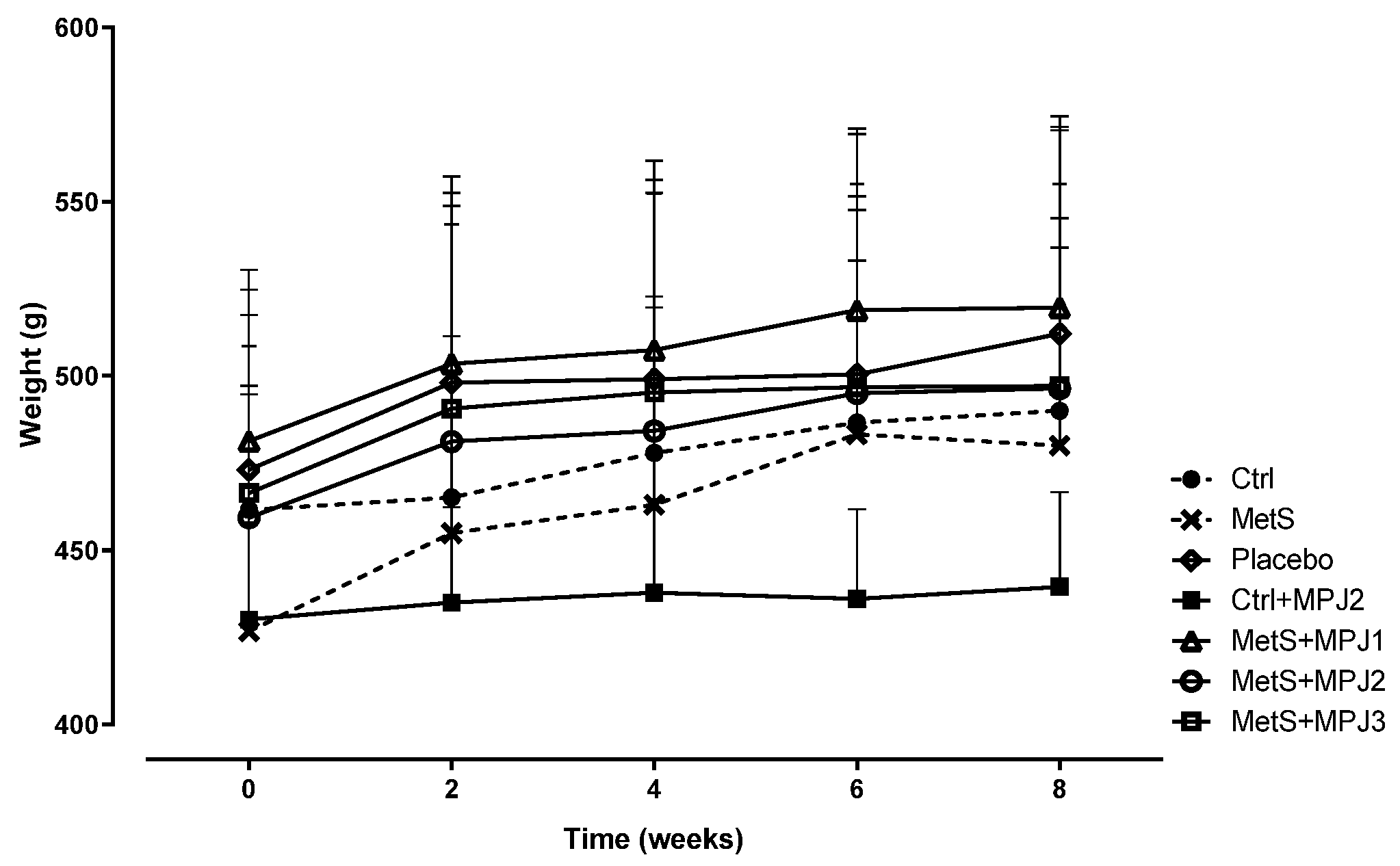

3.2. Body Weight

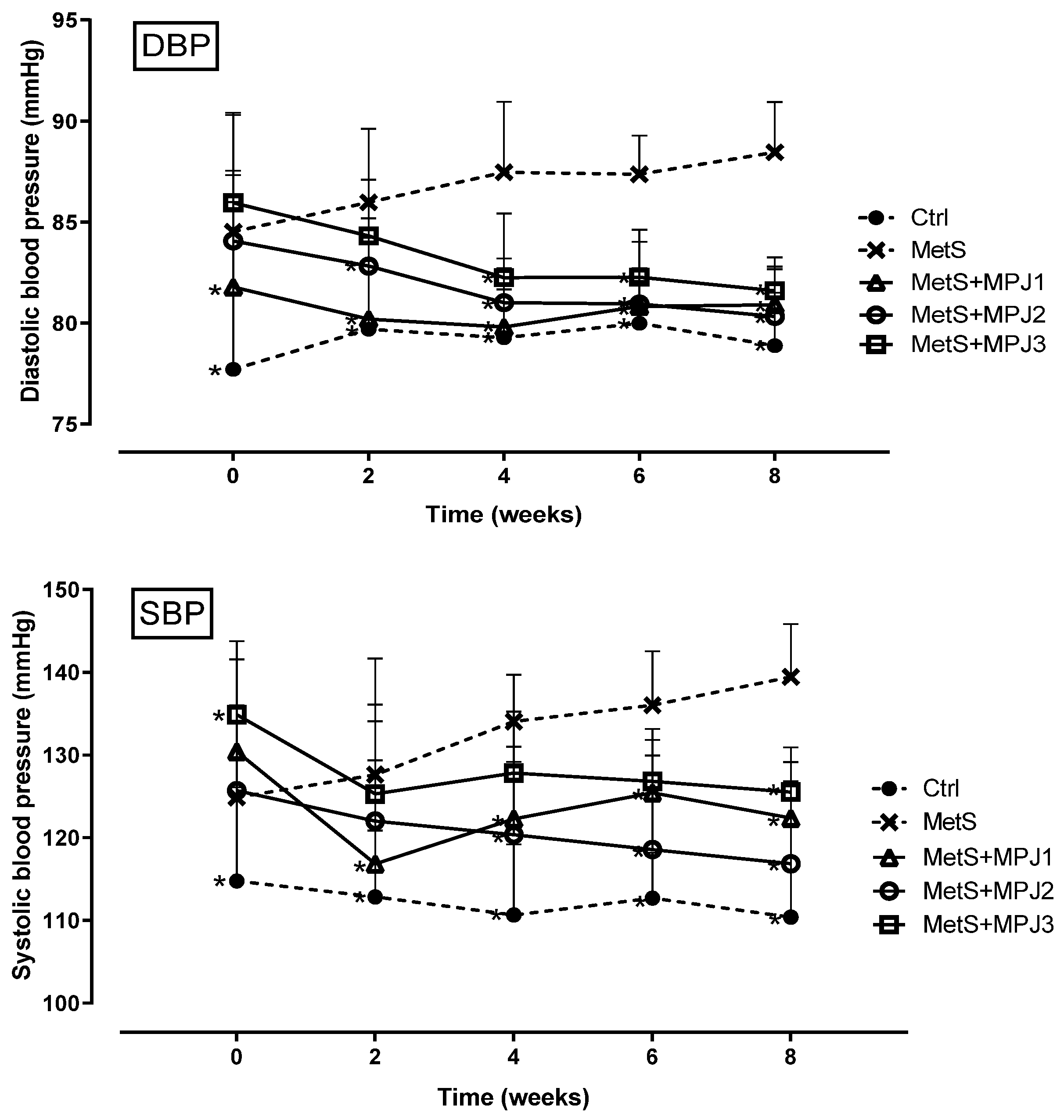

3.3. Blood Pressure

3.4. Biochemical Analysis

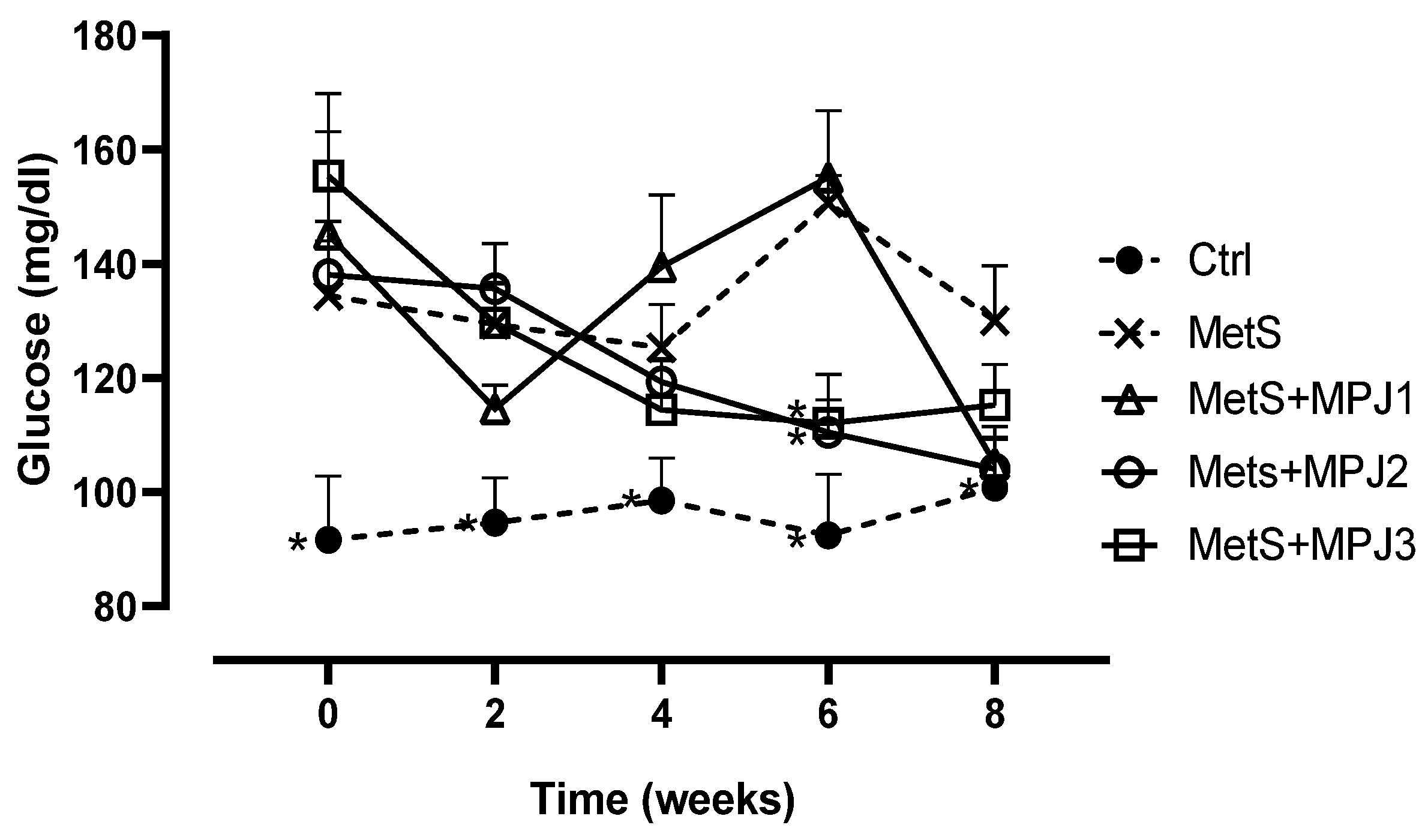

Glucose

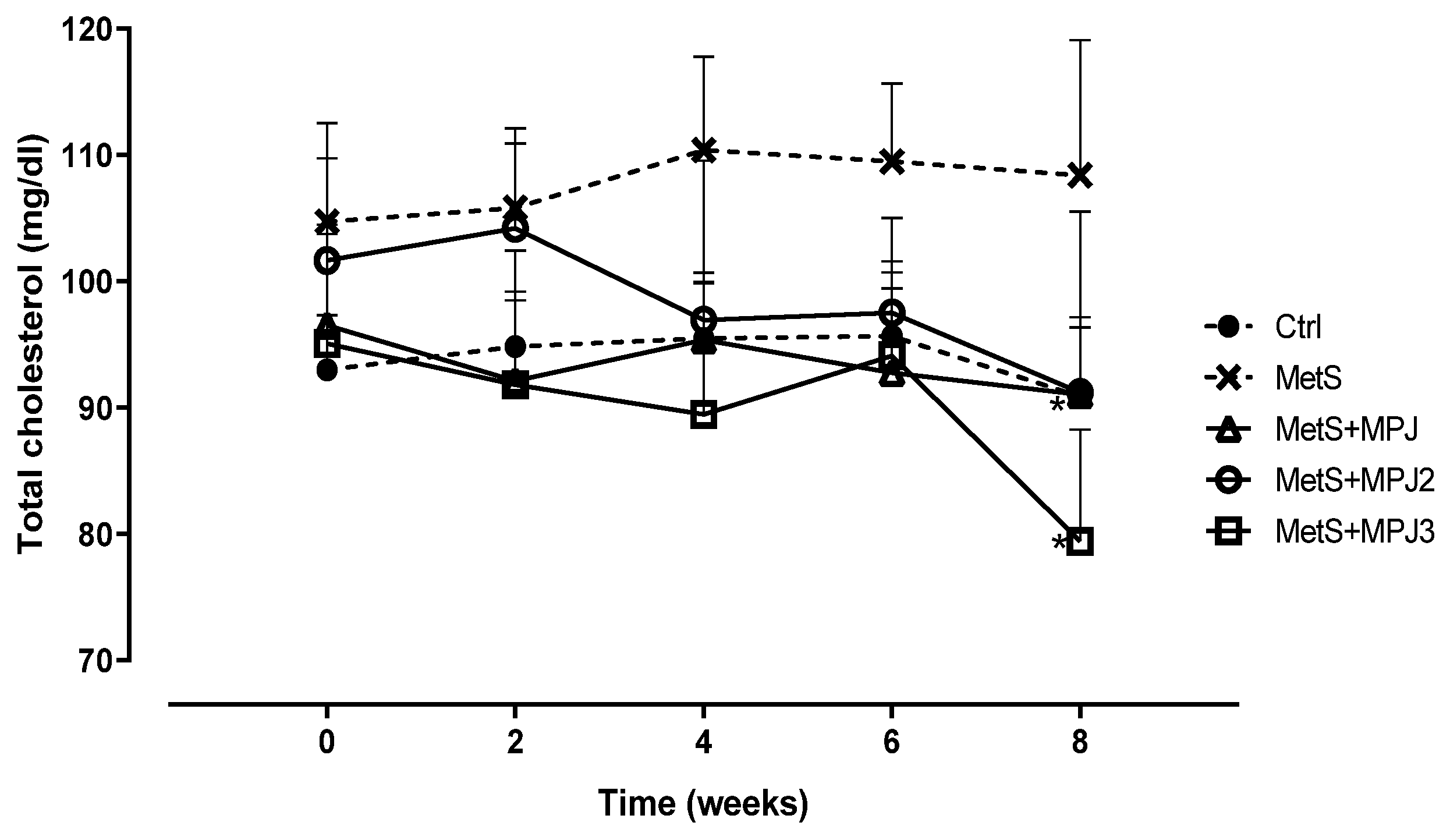

Total Cholesterol

LDL-c and HDL-c

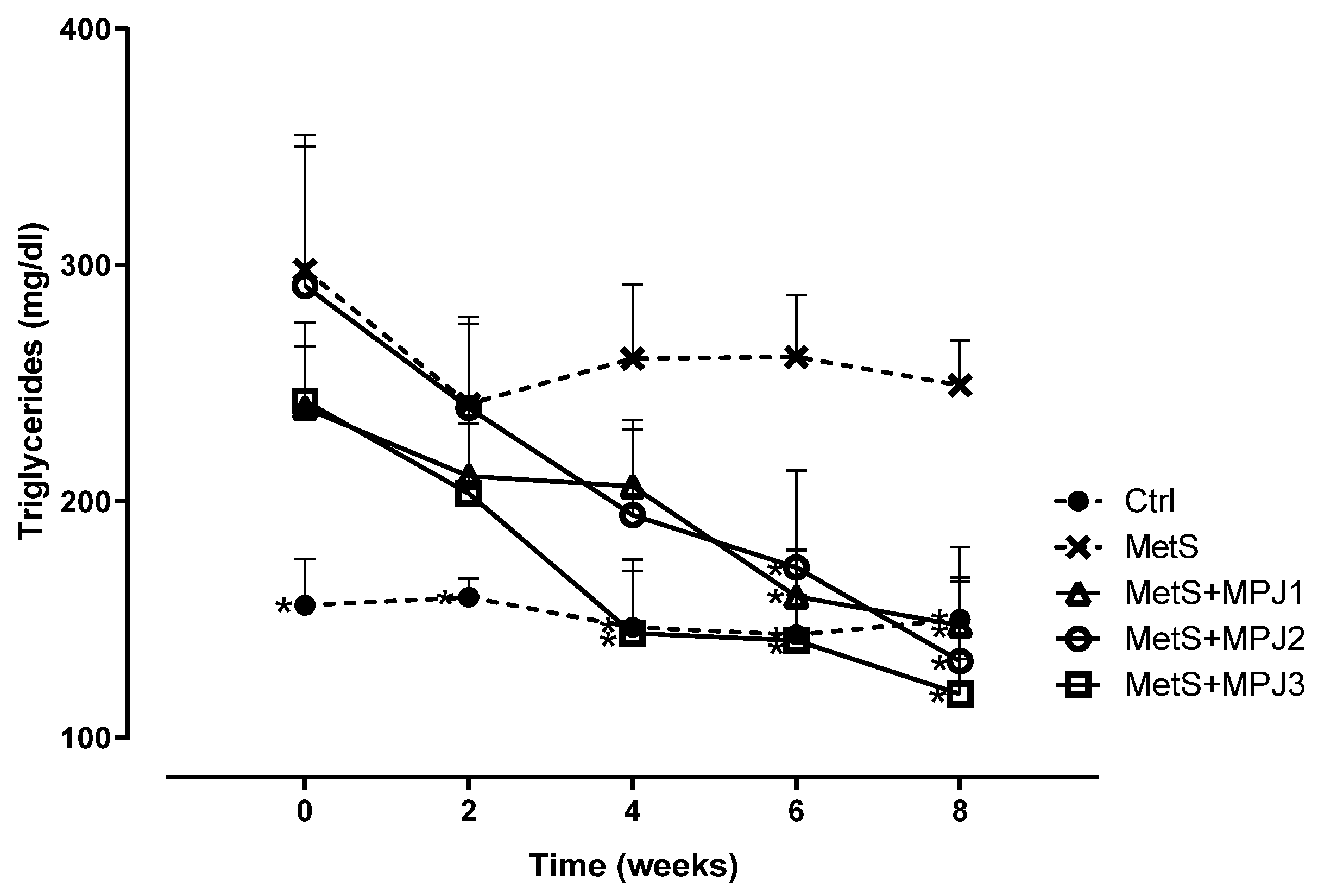

Triglycerides

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (cvds). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Ambroselli, D.; Masciulli, F.; Romano, E.; Catanzaro, G.; Besharat, Z.M.; Massari, M.C.; Ferretti, E.; Migliaccio, S.; Izzo, L.; Ritieni, A.; et al. New Advances in Metabolic Syndrome, from Prevention to Treatment: The Role of Diet and Food. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, M.; Varghese, T.P.; Sharma, R.; Chand, S. Association Between Metabolic Syndrome and Diabetes Mellitus According to International Diabetic Federation and National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Criteria: a Cross-sectional Study. J Diabetes Met Dis 2020, 19, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, F.; Bo, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Ju, L.; Fang, H.; Piao, W.; Yu, D.; Lao, X. Prevalence and Influencing Factors of Metabolic Syndrome among Adults in China from 2015 to 2017. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayi, T.; Ozgoren, M. Effects of the Mediterranean diet on the components of metabolic syndrome. J Prevent Med Hygiene 2022, 63, E56–E64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, U.; Khaliq, S.; Ahmad, H.U.; Manzoor, S.; Lone, K.P. Metabolic syndrome: an update on diagnostic criteria, pathogenesis, and genetic links. Hormones 2018, 17, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslov, L.N.; Naryzhnaya, N.V.; Boshchenko, A.A.; Popov, S.V.; Ivanov, V.V.; Oeltgen, P.R. Is oxidative stress of adipocytes a cause or a consequence of the metabolic syndrome? J Clin Transl Endocrinol 2019, 15, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monserrat-Mesquida, M.; Quetglas-Llabrés, M.; Capó, X.; Bouzas, C.; Mateos, D.; Pons, A.; Tur, J.A.; Sureda, A. Metabolic Syndrome is Associated with Oxidative Stress and Proinflammatory State. Antioxidants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Barbalho, S.M.; Marquess, A.R.; Grecco, A.I.S.; Goulart, R.A.; Tofano, R.J.; Bishayee, A. Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) and Metabolic Syndrome Risk Factors and Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Duo, L.; Wang, J.; GegenZhula; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Tu, Y. A unique understanding of traditional medicine of pomegranate, Punica granatum L. and its current research status. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 271, 113877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morvaridzadeh, M.; Sepidarkish, M.; Daneshzad, E.; Akbari, A.; Mobini, G.R.; Heshmati, J. The effect of pomegranate on oxidative stress parameters: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Compl Ther Med 2020, 48, 102252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirzadeh, M.; Caporaso, N.; Rauf, A.; Shariati, M.A.; Yessimbekov, Z.; Khan, M.U.; Imran, M.; Mubarak, M.S. Pomegranate as a source of bioactive constituents: a review on their characterization, properties and applications. Crit Rev Food Sci Nut 2021, 61, 982–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahmy, H.; Hegazi, N.; El-Shamy, S.; Farag, M.A. Pomegranate juice as a functional food: a comprehensive review of its polyphenols, therapeutic merits, and recent patents. Food Funct 2020, 11, 5768–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegazi, N.M.; El-Shamy, S.; Fahmy, H.; Farag, M.A. Pomegranate juice as a super-food: A comprehensive review of its extraction, analysis, and quality assessment approaches. J Food Comp Anal 2021, 97, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, J.P.; Kaur, A.; Singh, N. Phenolic compounds as beneficial phytochemicals in pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel: A review. Food Chem 2018, 261, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaemi, F.; Emadzadeh, M.; Atkin, S.L.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Zengin, G.; Sahebkar, A. Impact of pomegranate juice on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytother Res 2023, 37, 4429–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.I.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Hess-Pierce, B.; Holcroft, D.M.; Kader, A.A. Antioxidant activity of pomegranate juice and its relationship with phenolic composition and processing. J Agric Food Chem 2000, 48, 4581–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Ismail, T.; Fraternale, D.; Sestili, P. Pomegranate peel and peel extracts: chemistry and food features. Food Chem 2015, 174, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučić, V.; Grabež, M.; Trchounian, A.; Arsić, A. Composition and Potential Health Benefits of Pomegranate: A Review. Curr Pharm Design 2019, 25, 1817–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMatar, M.; Islam, M.R.; Albarri, O.; Var, I.; Koksal, F. Pomegranate as a Possible Treatment in Reducing Risk of Developing Wound Healing, Obesity, Neurodegenerative Disorders, and Diabetes Mellitus. Mini Rev Med Chem 2018, 18, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Du, L.; Lv, O.; Zhao, S.; Li, J. Beneficial Effects of Pomegranate on Lipid Metabolism in Metabolic Disorders. Mol Nut Food Res 2019, 63, e1800773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medjakovic, S.; Jungbauer, A. Pomegranate: a fruit that ameliorates metabolic syndrome. Food Funct 2013, 4, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada-Luna, D.; Carreón-Torres, E.; Bautista-Pérez, R.; Betanzos-Cabrera, G.; Dorantes-Morales, A.; Luna-Luna, M.; Vargas-Barrón, J.; Mejía, A.M.; Fragoso, J.M.; Carvajal-Aguilera, K.; et al. Microencapsulated Pomegranate Reverts High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL)-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction and Reduces Postprandial Triglyceridemia in Women with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hafidi, M.; Pérez, I.; Zamora, J.; Soto, V.; Carvajal-Sandoval, G.; Baños, G. Glycine intake decreases plasma free fatty acids, adipose cell size, and blood pressure in sucrose-fed rats. Am J Physiol. Reg Int Comp Physiol 2004, 287, R1387–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura-Clapier, R.; Piquereau, J.; Garnier, A.; Mericskay, M.; Lemaire, C.; Crozatier, B. Gender issues in cardiovascular diseases. Focus on energy metabolism. Bioch Biophys Acta 2020, 1866, 165722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Cervantes, P.; Izquierdo-Vega, J.A.; Morán-León, J.; Guerrero-Solano, J.A.; García-Pérez, B.E.; Cancino-Díaz, J.C.; Belefant-Miller, H.; Betanzos-Cabrera, G. Subacute and subchronic toxicity of microencapsulated pomegranate juice in rats and mice. Toxicol Res 2021, 10, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, A.; Carbone, F.; Tirandi, A.; Montecucco, F.; Liberale, L. Obesity phenotypes and cardiovascular risk: From pathophysiology to clinical management. Rev Endocr Met Dis 2023, 24, 901–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Gaspar, V.; Sánchez-Meza, K.; López-Alcaraz, F.; Palacios-Fonseca, A.J.; del Toro-Equihua, M.; Montero-Cruz, S.A.; Hummel, J.; Cerna-Cortés, J.F.; Cerna-Cortés, J. Reducción de la ingesta de alimento balanceado por consumo de agua endulzada con sacarosa en ratas Wistar. Acta Bioquím Clín Latinoam 2020, 54, 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva-Gutiérrez, S.; Villegas Sepúlveda, N.; Olmedo-Buenrostro, B.; Virgen-Ortiz, A.; Palacios Fonseca, A.; López Alcaraz, F. Análisis comparativo del consumo crónico de agua endulzada con sacarosa o stevia con respecto al peso corporal, la cantidad de alimento consumido y el desarrollo de diabetes y dislipidemias en ratas Wistar. Temas Cienc Tecnol 2017, 21, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, I.M.; Goble, E.A.; Wittert, G.A.; Morley, J.E.; Horowitz, M. Effect of intravenous glucose and euglycemic insulin infusions on short-term appetite and food intake. Am J Physiol 1998, 274, R596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.; Samir el, S.A.; El-Shehawi, A.M.; Alkafafy, M.E. Anti-obesity effects of Taif and Egyptian pomegranates: molecular study. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2015, 79, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.F.; Soliman, G.M.; Okasha, E.F.; Shalaby, A.M. Histological, Immunohistochemical, and Biochemical Study of Experimentally Induced Fatty Liver in Adult Male Albino Rat and the Possible Protective Role of Pomegranate. J Micros Ultrastruct 2018, 6, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Les, F.; Carpéné, C.; Arbonés-Mainar, J.M.; Decaunes, P.; Valero, M.S.; López, V. Pomegranate juice and its main polyphenols exhibit direct effects on amine oxidases from human adipose tissue and inhibit lipid metabolism in adipocytes. J Funct Foods 2017, 33, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, F.; Zhang, X.N.; Wang, W.; Xing, D.M.; Xie, W.D.; Su, H.; Du, L.J. Evidence of anti-obesity effects of the pomegranate leaf extract in high-fat diet induced obese mice. Int J Obesity (2005) 2007, 31, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Yan, C.; Shi, Y.; Cao, K.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Luo, C.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity-associated nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the protective effects of pomegranate with its active component punicalagin. Antiox Redox Sign 2014, 21, 1557–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, E.; Do, G.M.; Lim, Y.; Park, J.E.; Park, Y.J.; Kwon, O. Pomegranate vinegar attenuates adiposity in obese rats through coordinated control of AMPK signaling in the liver and adipose tissue. Lip Health Dis 2013, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigin, V.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol 2021, 20, 795–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahari, H.; Omidian, K.; Goudarzi, K.; Rafiei, H.; Asbaghi, O.; Hosseini Kolbadi, K.S.; Naderian, M.; Hosseini, A. The effects of pomegranate consumption on blood pressure in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytother Res 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, M.; Waghulde, H.; Kasture, S. Effect of pomegranate juice on Angiotensin II-induced hypertension in diabetic Wistar rats. Phytother Res 2010, 24 Suppl 2, S196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Rong, X.; Um, I.S.; Yamahara, J.; Li, Y. 55-week treatment of mice with the unani and ayurvedic medicine pomegranate flower ameliorates ageing-associated insulin resistance and skin abnormalities. Evid Based Comp Altern Med 2012, 2012, 350125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Yan, C.; Frost, B.; Wang, X.; Hou, C.; Zeng, M.; Gao, H.; Kang, Y.; Liu, J. Pomegranate extract decreases oxidative stress and alleviates mitochondrial impairment by activating AMPK-Nrf2 in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 34246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Wang, P.; Liu, A.; Du, X.; Bai, J.; Chen, M. Punicalagin Prevents Hypoxic Pulmonary Hypertension via Anti-Oxidant Effects in Rats. Am J Chin Med 2016, 44, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, M.; Ahmed, M.G.; Bhattacharjee, A. The potential for interaction of tolbutamide with pomegranate juice against diabetic induced complications in rats. Integr Med Res 2017, 6, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera-Sandoval, C.; Fabela-Illescas, H.E.; Fernández-Martínez, E.; Ortiz-Rodríguez, M.A.; Cariño-Cortés, R.; Ariza-Ortega, J.A.; Hernández-González, J.C.; Olivo, D.; Valadez-Vega, C.; Belefant-Miller, H.; et al. Potential Mechanisms of the Improvement of Glucose Homeostasis in Type 2 Diabetes by Pomegranate Juice. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgen-Carrillo, C.A.; Martínez Moreno, A.G.; Valdés Miramontes, E.H. Potential Hypoglycemic Effect of Pomegranate Juice and Its Mechanism of Action: A Systematic Review. J Med Food 2020, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohrab, G.; Roshan, H.; Ebrahimof, S.; Nikpayam, O.; Sotoudeh, G.; Siasi, F. Effects of pomegranate juice consumption on blood pressure and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: A single-blind randomized clinical trial. Clin Nutr 2019, 29, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekooeian, A.A.; Eftekhari, M.H.; Adibi, S.; Rajaeifard, A. Effects of pomegranate seed oil on insulin release in rats with type 2 diabetes. Iran J Med Sci 2014, 39, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.H.; Peng, G.; Kota, B.P.; Li, G.Q.; Yamahara, J.; Roufogalis, B.D.; Li, Y. Anti-diabetic action of Punica granatum flower extract: activation of PPAR-gamma and identification of an active component. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2005, 207, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.H.; Yang, Q.; Harada, M.; Li, G.Q.; Yamahara, J.; Roufogalis, B.D.; Li, Y. Pomegranate flower extract diminishes cardiac fibrosis in Zucker diabetic fatty rats: modulation of cardiac endothelin-1 and nuclear factor-kappaB pathways. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2005, 46, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nankar, R.P.; Doble, M. Ellagic acid potentiates insulin sensitising activity of pioglitazone in L6 myotubes. J Funct Foods 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Missiry, M.A.; Amer, M.A.; Hemieda, F.A.E.; Othman, A.I.; Sakr, D.A.; Abdulhadi, H.L. Cardioameliorative effect of punicalagin against streptozotocin-induced apoptosis, redox imbalance, metabolic changes and inflammation. Egyp J Basic Appl Sci 2015, 2, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Fang, Z.; Wang, H.; Cai, Y.; Rahimi, K.; Zhu, Y.; Fowkes, F.G.R.; Fowkes, F.J.I.; Rudan, I. Global and regional prevalence, burden, and risk factors for carotid atherosclerosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2020, 8, e721–e729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, M.; Kitagawa, T.; Koyanagi, N.; Chujo, H.; Maeda, H.; Kohno-Murase, J.; Imamura, J.; Tachibana, H.; Yamada, K. Dietary effect of pomegranate seed oil on immune function and lipid metabolism in mice. Nutrition 2006, 22, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlin, B.K.; Strohacker, K.A.; Kueht, M.L. Pomegranate seed oil consumption during a period of high-fat feeding reduces weight gain and reduces type 2 diabetes risk in CD-1 mice. Brit J Nutr 2009, 102, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betanzos-Cabrera, G.; Guerrero-Solano, J.A.; Martínez-Pérez, M.M.; Calderón-Ramos, Z.G.; Belefant-Miller, H.; Cancino-Diaz, J.C. Pomegranate juice increases levels of paraoxonase1 (PON1) expression and enzymatic activity in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice fed with a high-fat diet. Food Res Int 2011, 44, 1381–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, P.; Fazeli, M.R.; Asghari, G.; Shafiee, A.; Azizi, F. Effect of pomegranate seed oil on hyperlipidaemic subjects: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Brit J Nutr 2010, 104, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Luna, D.; Martínez-Hinojosa, E.; Cancino-Diaz, J.C.; Belefant-Miller, H.; López-Rodríguez, G.; Betanzos-Cabrera, G. Daily supplementation with fresh pomegranate juice increases paraoxonase 1 expression and activity in mice fed a high-fat diet. Eur J Nutr 2018, 57, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casula, M.; Colpani, O.; Xie, S.; Catapano, A.L.; Baragetti, A. HDL in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: In Search of a Role. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaillzadeh, A.; Tahbaz, F.; Gaieni, I.; Alavi-Majd, H.; Azadbakht, L. Concentrated pomegranate juice improves lipid profiles in diabetic patients with hyperlipidemia. J Med Food 2004, 7, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Chávez, P.; Infante-Vázquez, O.; Sánchez-Torres, G.; Martínez-Memije, R.; Rodríguez-Rossini, G. A non-invasive methods to record vital signs in rats. Vet Mex 2002, 22, 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald, W.T.; Levy, R.I.; Fredrickson, D.S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972, 18, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).