Submitted:

20 September 2024

Posted:

23 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Isolation Technics

2.2. Culture Medium

2.3. Biochemical and Cultural Identification of Isolated Strains

2.4. Molecular Identification

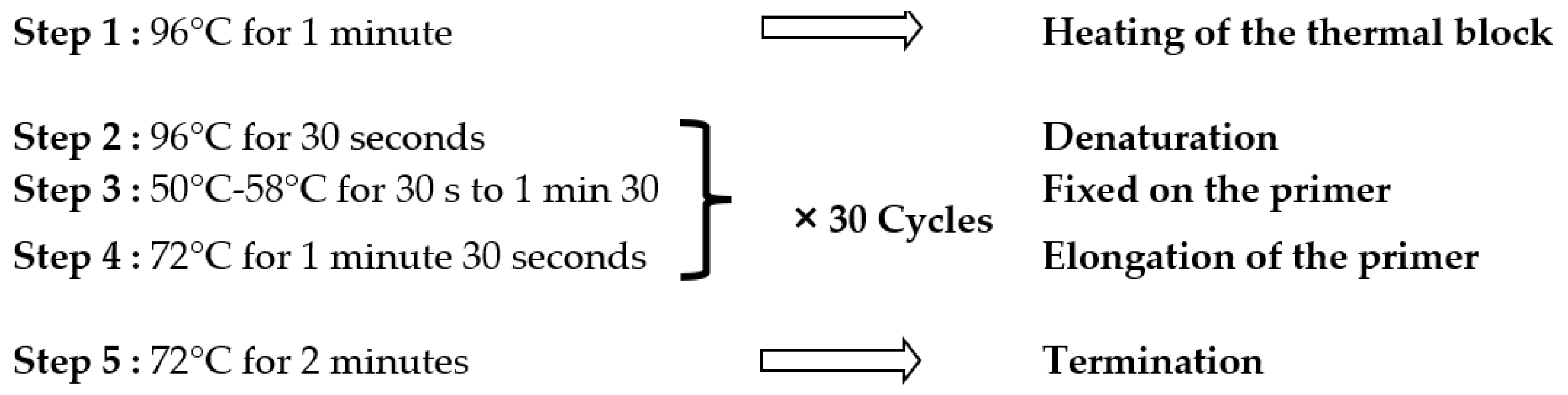

2.4.1. PCR Amplification of 16S rDNA and PCR Programming

2.4.2. 16S rDNA Sequencing

2.4.3. Phylogenetic Analysis and Similarity Distance Calculations

2.5. Selection of the Strains According to Physiological and Biochemical Characteristics

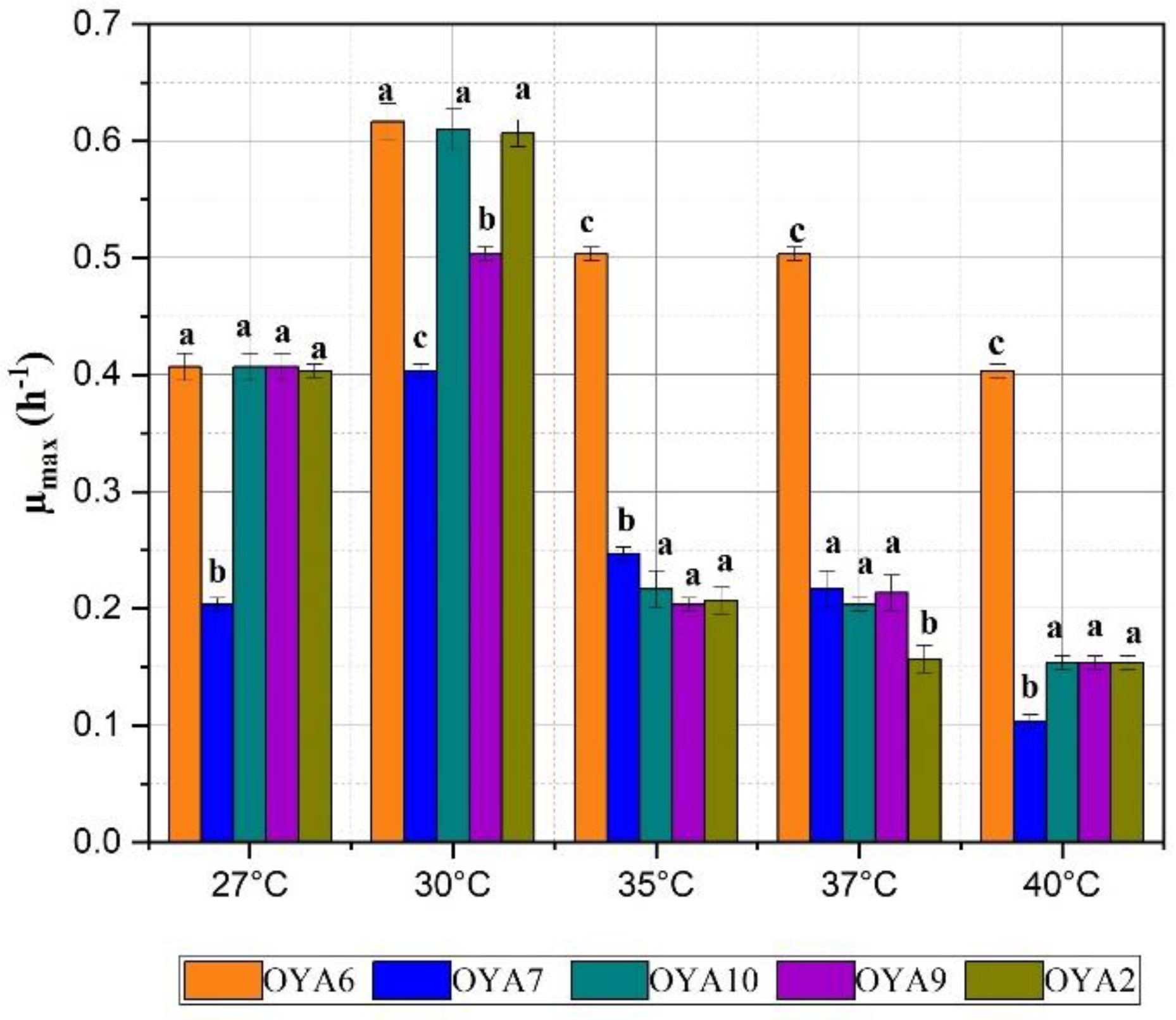

- Thermo-tolerance test: Cultures were incubated at temperatures of 30 °C, 35 °C, 37 °C, and 40 °C.

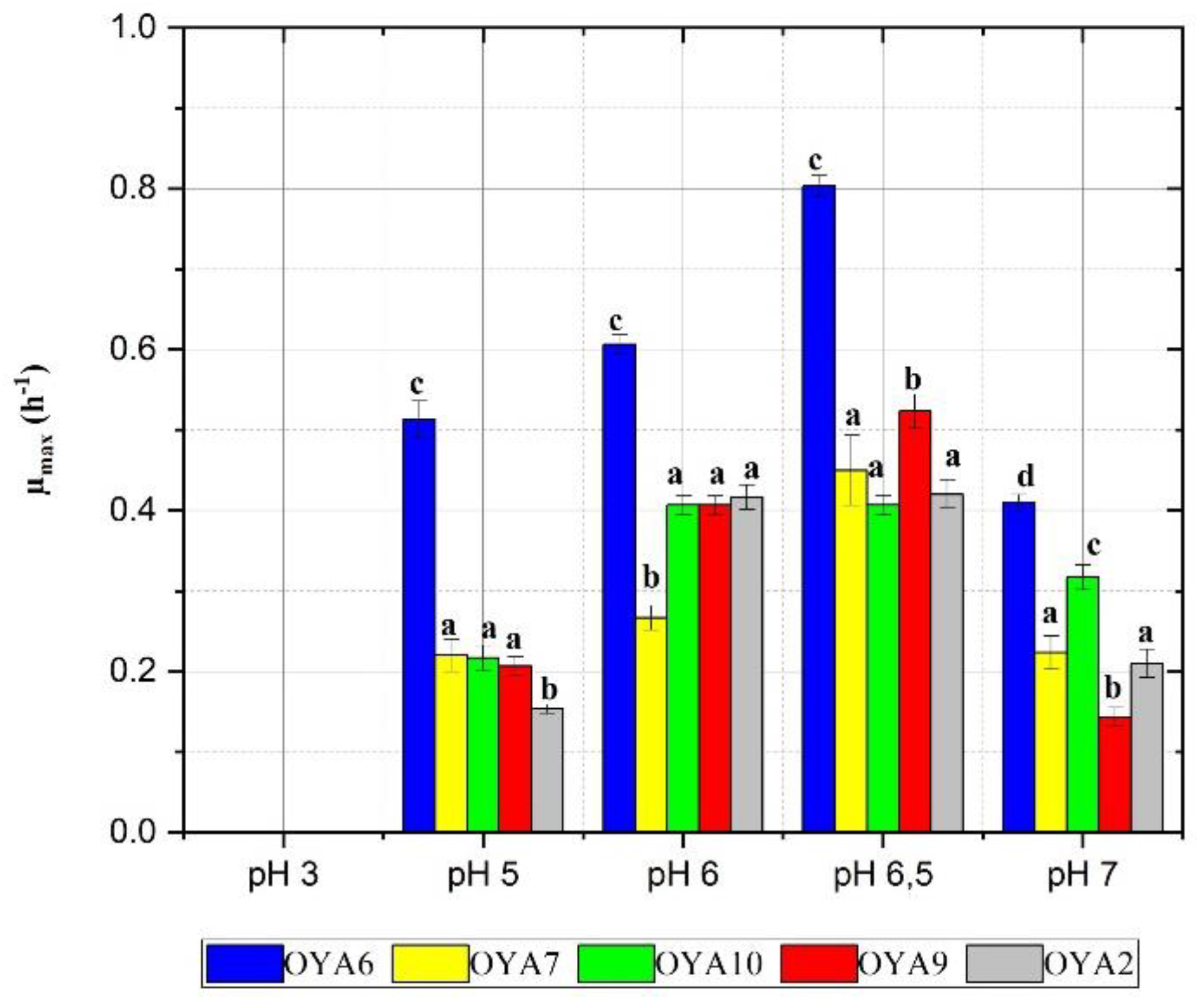

- Effect of pH: Bacteria were grown at pH 3, 5, 6, 6.5 and 7

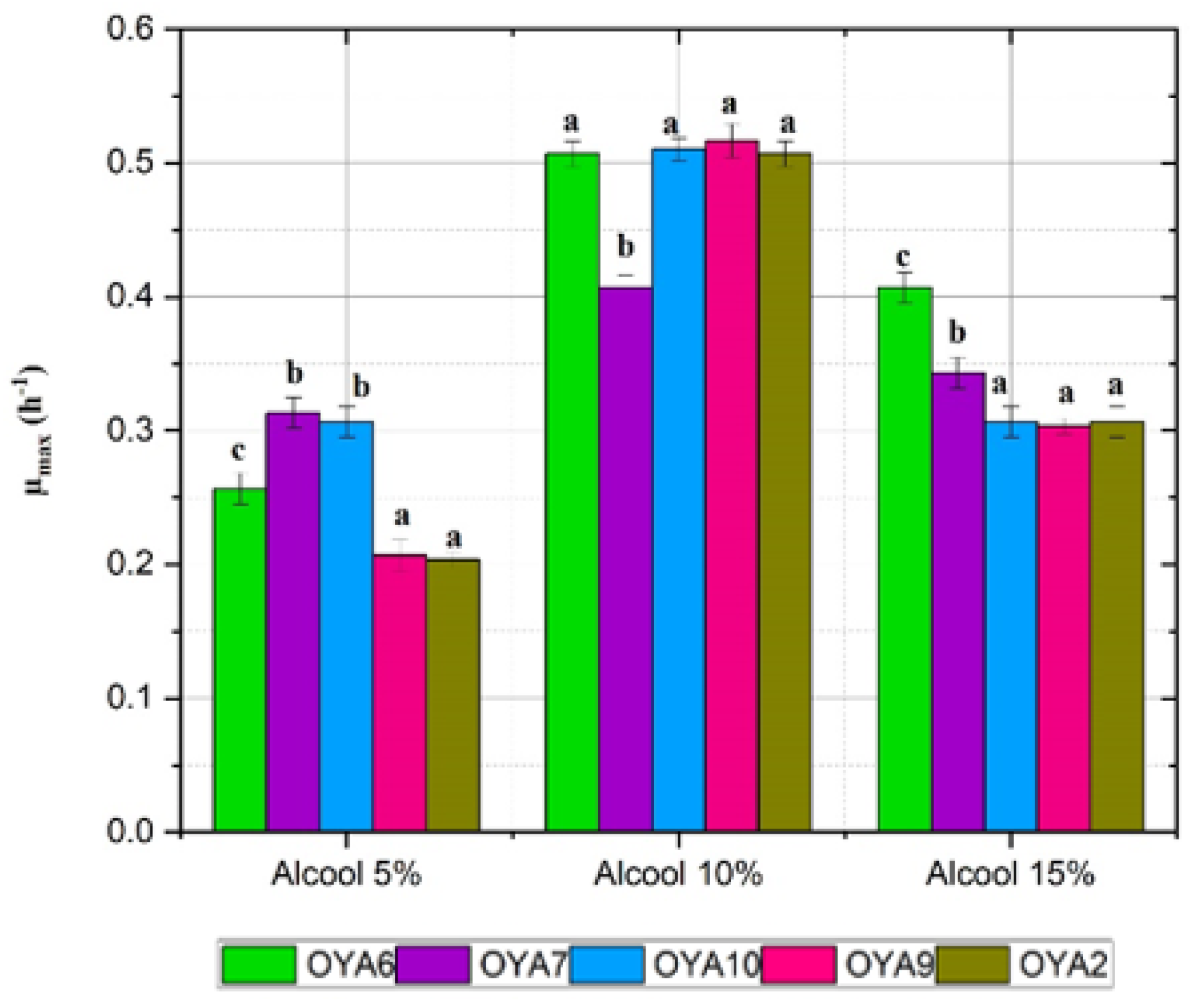

- Ethanol tolerance test: Bacteria were grown in GYP medium supplemented with at 5°, 10° and 15° alcohol (v/v).

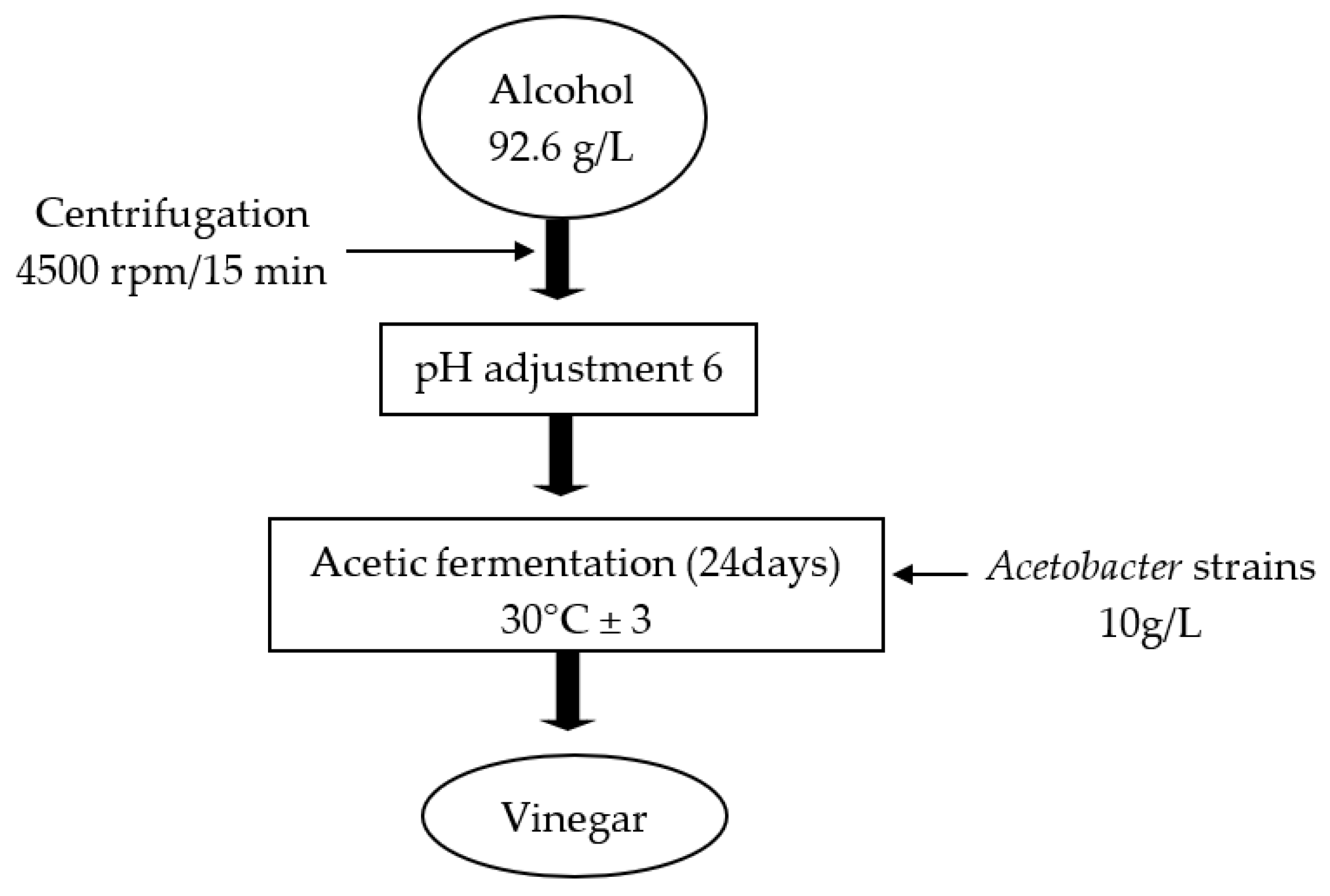

2.6. Acetic Acid Production

2.7. Estimation of Acetic Acid

2.8. Fermentation Parameters

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation, Screening, and Identification of the Strains for Production of Acetic

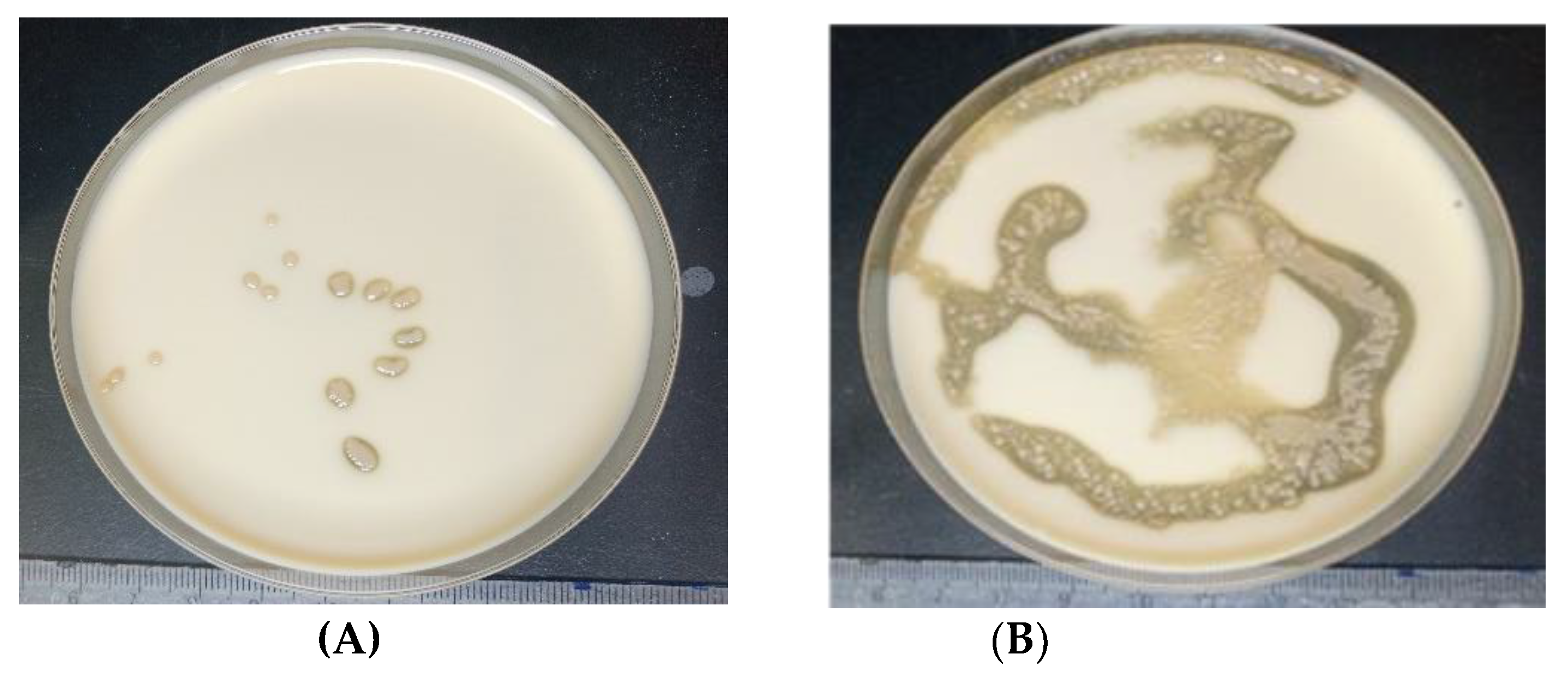

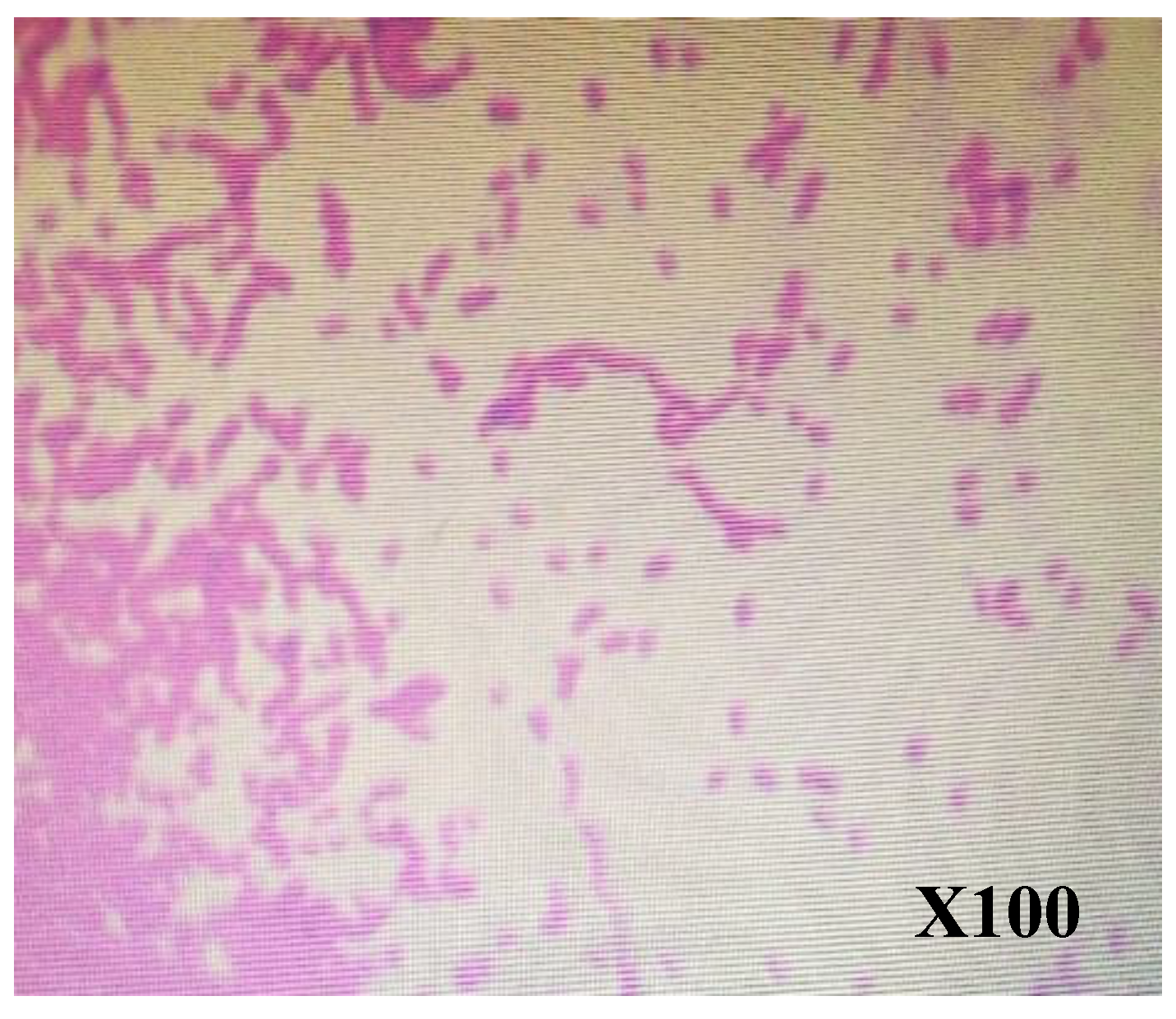

3.1.1. Biochemical and Cultural Identification of Isolated Strains

3.1.2. Molecular Identification

3.1.3. Physiological Characterization of Isolated Acetic Acid Bacteria Strains

- Effect of temperature

- Effect of pH

- Effect of alcohol

3.2. Acetic acid Fermentation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chuvochina, M.; Mussig, A.J.; Chaumeil, P.-A.; Skarshewski, A.; Rinke, C.; Parks, D.H.; Hugenholtz, P. Proposal of Names for 329 Higher Rank Taxa Defined in the Genome Taxonomy Database under Two Prokaryotic Codes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2023, 370, fnad071. [CrossRef]

- Kersters, K.; Lisdiyanti, P.; Komagata, K.; Swings, J. The Family Acetobacteraceae: The Genera Acetobacter, Acidomonas, Asaia, Gluconacetobacter, Gluconobacter, and Kozakia. In The Prokaryotes: Volume 5: Proteobacteria: Alpha and Beta Subclasses; Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.-H., Stackebrandt, E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2006; pp. 163–200 ISBN 978-0-387-30745-9.

- Sengun, I.Y.; Karabiyikli, S. Importance of Acetic Acid Bacteria in Food Industry. Food. Control. 2011, 22, 647–656. [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, R.; Leprince, P.; Sombolestani, A.S.; Thonart, P.; Delvigne, F. Effect of Sequential Acclimation to Various Carbon Sources on the Proteome of Acetobacter Senegalensis LMG 23690T and Its Tolerance to Downstream Process Stresses. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 608. [CrossRef]

- FAO-WHO Food Standards Programme. ROME. https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/en/ (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- AFNOR NF EN 13188-Octobre 2000 : Vinaigre Produit Fabriqué à Partir de Liquides d’origine Agricole. Définitions, Prescriptions, Marquage. - Recherche Google Available online: https://www.boutique.afnor.org/fr-fr/norme/nf-en-13188/vinaigre-produit-fabrique-a-partir-de-liquides-dorigine-agricole-definition/fa036606/17808 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Joyeux, A.; Lafon-Lafourcade, S.; Ribéreau-Gayon, P. Evolution of Acetic Acid Bacteria During Fermentation and Storage of Wine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1984, 48, 153–156.

- Ndoye, B.; Cleenwerck, I.; Engelbeen, K.; Dubois-Dauphin, R.; Guiro, A.T.; Van Trappen, S.; Willems, A.; Thonart, P. Acetobacter Senegalensis Sp. Nov., a Thermotolerant Acetic Acid Bacterium Isolated in Senegal (Sub-Saharan Africa) from Mango Fruit (Mangifera Indica L.). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 1576–1581. [CrossRef]

- Konate, M.; Akpa, E.; Bernadette, G.; Koffi, L.; Honore, O.; Niamke, S. Banana Vinegars Production Using Thermotolerant Acetobacter Pasteurianus Isolated From Ivorian Palm Wine. J. Food Res. 2015, 4, p92. [CrossRef]

- Ndoye, B.; Lebecque, S.; Dubois-Dauphin, R.; Tounkara, L.; Guiro, A.-T.; Kere, C.; Diawara, B.; Thonart, P. Thermoresistant Properties of Acetic Acids Bacteria Isolated from Tropical Products of Sub-Saharan Africa and Destined to Industrial Vinegar. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2006, 39, 916–923. [CrossRef]

- Ndoye, B.; Shafiei, R.; Sanaei, N.S.; Cleenwerck, I.; Somda, M.K.; Dicko, M.H.; Tounkara, L.S.; Guiro, A.T.; Delvigne, F.; Thonart, P. Acetobacter Senegalensis Isolated from Mango Fruits: Its Polyphasic Characterization and Adaptation to Protect against Stressors in the Industrial Production of Vinegar: A Review. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 4130–4149. [CrossRef]

- Cleenwerck, I.; Camu, N.; Engelbeen, K.; De Winter, T.; Vandemeulebroecke, K.; De Vos, P.; De Vuyst, L. Acetobacter Ghanensis Sp. Nov., a Novel Acetic Acid Bacterium Isolated from Traditional Heap Fermentations of Ghanaian Cocoa Beans. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 1647–1652. [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, A.; Somda, M.; SINA, H.; Mousse, W.; Christine, N. tcha; C.A.T, O.; Traore, A.; Baba-Moussa, L.; Ouattara, A. Screening and Molecular Identification of Indigenous Strains of Acetic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Mango Biotopes in Burkina Faso. Afr. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2021, 12, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, C.-Y.; Jo, H.-W.; Lee, W.-H.; Kim, E.-H.; Choi, B.-K.; Huh, C.-K. Screening of Acetic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Various Sources for Use in Kombucha Production. Fermentation. 2023, 10, 18. [CrossRef]

- Vegas, C.; Mateo, E.; González, A.; Jara, C.; Guillamon, J.; Poblet, M.; Torija, M.; Mas, A. Population Dynamics of Acetic Acid Bacteria during Traditional Wine Vinegar Production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 138, 130–136. [CrossRef]

- Sombolestani, A.S.; Cleenwerck, I.; Cnockaert, M.; Borremans, W.; Wieme, A.D.; De Vuyst, L.; Vandamme, P. Novel Acetic Acid Bacteria from Cider Fermentations: Acetobacter Conturbans Sp. Nov. and Acetobacter Fallax Sp. Nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 6163–6171. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Hosono, R.; Lisdyanti, P.; Widyastuti, Y.; Saono, S.; Uchimura, T.; Komagata, K. Identification of Acetic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Indonesian Sources, Especially of Isolates Classified in the Genus Gluconobacter. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 1999, 45, 23–28. [CrossRef]

- Komagata, K.; Iino, T.; Yamada, Y. The Family Acetobacteraceae. In The Prokaryotes: Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria; Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E.F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E., Thompson, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; pp. 3–78 ISBN 978-3-642-30197-1.

- Katsura, K.; Kawasaki, H.; Potacharoen, W.; Saono, S.; Seki, T.; Yamada, Y.; Uchimura, T.; Komagata, K. Asaia Siamensis Sp. Nov., an Acetic Acid Bacterium in the Alpha-Proteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001, 51, 559–563. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, R.; Zhang, Y.; Iino, T.; Kosako, Y.; Komagata, K.; Uchimura, T. Asaia Astilbes Sp. Nov., Asaia Platycodi Sp. Nov., and Asaia Prunellae Sp. Nov., Novel Acetic Acid Bacteria Solated from Flowers in Japan. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 56, 339–346. [CrossRef]

- Lino, T.; Suzuki, R.; Kosako, Y.; Ohkuma, M.; Komagata, K.; Uchimura, T. Acetobacter Okinawensis Sp. Nov., Acetobacter Papayae Sp. Nov., and Acetobacter Persicus Sp. Nov.; Novel Acetic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Stems of Sugarcane, Fruits, and a Flower in Japan. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 58, 235–243. [CrossRef]

- Aluko, A.; Makule, E.; Kassim, N. Effect of Clarification on Physicochemical Properties and Nutrient Retention of Pressed and Blended Cashew Apple Juice. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Doudjo, S.; Dornier, M.; Abreu, F.; Assidjo, E.; Yao, B.; Reynes, R. The Cashew ( Anacardium Occidentale ) Industry in Côte d’Ivoire: Analysis and Prospects for Development. Fruits. 2011, 66, 237–245. [CrossRef]

- Gnagne, A.; Soro, D.; Ouattara, Y.; Koui, E.; Koffi, E. A Literature Review of Cashew Apple Processing. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2023, 23, 22452–22469. [CrossRef]

- Yaya Anianhou, O.; Soro, D.; Kakou, E.; Koné, K.; Assidjo, E.; Mabia, G.; Kamagate, M. Synthesis and Characterisation of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Immobilised Cells from Cashew Apple Bagasse. Revue des Bioressources. 2023, 18, 3736–3749. [CrossRef]

- Guero, M.; Drion, B.; Karsch, P. Study of the Biomass Potential in Côte d’Ivoire 2021.

- Usharani, G.; Rani, Mrs.G.U. Isolation and Identification of an Acetobacter Isolate from Cashew Apple as a Potential Strain for Vinegar Production. Int. J. Recent Sci. Res. 2011, 3, 080–084.

- Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria; Whitman, W.B., Ed.; 1st ed.; Wiley, 2015; ISBN 978-1-118-96060-8.

- Ruiz, A.; Poblet, M.; Mas, A.; Guillamon, J. Identification of Acetic Acid Bacteria by RFLP of PCR-Amplified 16S rDNA and 16S-23S rDNA Intergenic Spacer. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000, 50, 1981–1987. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J. DNA Protocols for Plants. In Molecular Techniques in Taxonomy; Hewitt, G.M., Johnston, A.W.B., Young, J.P.W., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1991; pp. 283–293 ISBN 978-3-642-83964-1.

- Gnangui, S.; Fossou, R.; Ebou, A.; Amon, R.E.; Koua, D.; Kouadjo, G.; Cowan, D.; Zézé, A. The Rhizobial Microbiome from the Tropical Savannah Zones in Northern Côte d’Ivoire. Microorganisms. 2021, 9, 1842. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Arya, P.; Gupta, K.; Randhawa, V.; Acharya, V.; Singh, A. Comparative Phylogenetic Analysis and Transcriptional Profiling of MADS-Box Gene Family Identified DAM and FLC-like Genes in Apple (Malus x Domestica). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20695. [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The Neighbor-Joining Method: A New Method for Reconstructing Phylogenetic Trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 24, 189–204. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.; Swofford, D. A Fast Method for Approximating Maximum Likelihoods of Phylogenetic Trees from Nucleotide Sequences. Syst. Biol. 1998, 47, 77–89. [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence Limits on Phylogenies: An Approach Using the Bootstrap. Evol. 1985, 39, 783. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464.

- Rashid, H.; Young, J.P.; Everall, I.; Clercx, P.; Willems, A.; Braun, M.; Wink, M. Average Nucleotide Identity of Genome Sequences Supports the Description of Rhizobium Lentis Sp. Nov., Rhizobium Bangladeshense Sp. Nov. and Rhizobium Binae Sp. Nov. from Lentil (Lens Culinaris) Nodules. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65. [CrossRef]

- Fossou, R.; Ziegler, D.; Zézé, A.; Barja, F.; Perret, X. Two Major Clades of Bradyrhizobia Dominate Symbiotic Interactions with Pigeonpea in Fields of Côte d’Ivoire. Front. microbiol. 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Cleenwerck, I.; Vandemeulebroecke, K.; Janssens, D.; Swings, J. Re-Examination of the Genus Acetobacter, with Descriptions of Acetobacter Cerevisiae Sp. Nov. and Acetobacter Malorum Sp. Nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 1551–1558. [CrossRef]

- Lisdiyanti, P.; Kawasaki, H.; Seki, T.; Yamada, Y.; Uchimura, T.; Komagata, K. Identification of Acetobacter Strains Isolated from Indonesian Sources, and Proposals of Acetobacter Syzygii Sp. Nov., Acetobacter Cibinongensis Sp. Nov., and Acetobacter Orientalis Sp. Nov. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 47, 119–131. [CrossRef]

- Lisdiyanti, P.; Kawasaki, H.; Seki, T.; Yamada, Y.; Uchimura, T.; Komagata, K. Systematic Study of the Genus Acetobacter with Descriptions of Acetobacter Indonesiensis Sp. Nov., Acetobacter Tropicalis Sp. Nov., Acetobacter Orleanensis (Henneberg 1906) Comb. Nov., Acetobacter Lovaniensis (Frateur 1950) Comb. Nov., and Acetobacter Estunensis (Carr 1958) Comb. Nov. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 46, 147–165. [CrossRef]

- Spitaels, F.; Li, L.; Wieme, A.; Balzarini, T.; Cleenwerck, I.; Van Landschoot, A.; De Vuyst, L.; Vandamme, P. Acetobacter Lambici Sp. Nov., Isolated from Fermenting Lambic Beer. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 1083–1089. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Gachhui, R. Novel Nitrogen-Fixing Acetobacter Nitrogenifigens Sp. Nov., Isolated from Kombucha Tea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 1899–1903. [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.T.L.; Yukphan, P.; Bui, V.T.T.; Charoenyingcharoen, P.; Malimas, S.; Nguyen, L.K.; Muramatsu, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Tanasupawat, S.; Le, B.T.; et al. Acetobacter Sacchari Sp. Nov., for a Plant Growth-Promoting Acetic Acid Bacterium Isolated in Vietnam. Ann. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 1155–1163. [CrossRef]

- Pitiwittayakul, N.; Yukphan, P.; Chaipitakchonlatarn, W.; Yamada, Y.; Theeragool, G. Acetobacter Thailandicus Sp. Nov., for a Strain Isolated in Thailand. Ann. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 1855–1863. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Rutherfurd-Markwick, K.; Zhang, X.-X.; Mutukumira, A.N. Isolation and Characterisation of Dominant Acetic Acid Bacteria and Yeast Isolated from Kombucha Samples at Point of Sale in New Zealand. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 835–844. [CrossRef]

- Mounir, M.; Shafiei, R.; Zarmehrkhorshid, R.; Hamouda, A.; Ismaili Alaoui, M.; Thonart, P. Simultaneous Production of Acetic and Gluconic Acids by a Thermotolerant Acetobacter Strain during Acetous Fermentation in a Bioreactor. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2016, 121, 166–171. [CrossRef]

- N’Guessan, Y.D.; Akpa, E.E.; Samaci, lamine; Ouattara, H.; Akoa, E.E.; Ahonzo-Niamké, S.L. Vinegar Production Trial from Cashew Apple (Anacardium Occidentale) Using Thermotolerant Acetobacter Strains with High Acetic Acid Yield in Non-Optimized Small Scale Conditions. Microbiol. Nat. 2020, 1, 107–119. [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, S.; Rasooli, I.; Beheshti-Maal, K. Isolation, Characterization and Optimization of Indigenous Acetic Acid Bacteria and Evaluation of Their Preservation Methods. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2010, 2, 38–45.

- Cire Kourouma, M.; Mbengue, M.; Sarr, K.; Toure Kane, C. Isolement, identification et caractérisation de souches de bactéries acétiques a partir d’un alcool de mangue fermente. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 9, 271–281. [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Sombolestani, A.S.; Laureys, D.; De Clippeleer, J.; Won, M.; Vandamme, P.; Kwon, S.-W. Acetobacter Vaccinii Sp. Nov., a Novel Acetic Acid Bacterium Isolated from Blueberry Fruit (Vaccinium Corymbosum L.). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-H.; Chang, M.-T.; Huang, L.; Chu, W.-S. Molecular Discrimination and Identification of Acetobacter Genus Based on the Partial Heat Shock Protein 60 Gene (Hsp60) Sequences. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94. [CrossRef]

- Stackebrandt, E.; Goebel, B.M. Taxonomic Note: A Place for DNA-DNA Reassociation and 16S rRNA Sequence Analysis in the Present Species Definition in Bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1994, 44, 846–849. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.-W.; Park, J.-Y.; Kim, J.-S.; Kang, J.W.; Cho, Y.-H.; Lim, C.-K.; Parker, M.; Lee, G.-B. Phylogenetic Analysis of the Genera Bradyrhizobium, Mesorhizobium, Rhizobium and Sinorhizobium on the Basis of 16S rRNA Gene and Internally Transcribed Spacer Region Sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 263–270. [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, W.; Morales, M.L.; Garcı́a-Parrilla, M.C.; Troncoso, A.M. Wine Vinegar: Technology, Authenticity and Quality Evaluation. Trends. Food. Sci. Tech. 2002, 1, 12–21. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Bai, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, C.; Xu, N.; Hu, Y. Improvement of the Flavor and Quality of Watermelon Vinegar by High Ethanol Fermentation Using Ethanol-Tolerant Acetic Acid Bacteria. Int. J. Food Eng. 2017, 13. [CrossRef]

- Drysdale, G.S.; Fleet, G.H. Acetic Acid Bacteria in Winemaking: A Review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1988, 39, 143–154. [CrossRef]

- Kyu-Ho, B.; Chae-Won, K.; Chul-Ho, K. Isolation of an Acetic Acid Bacterium Acetobacter Pasteurianus CK-1 and Its Fermentation Characteristics. J. Life. Sci. 2022, 32. [CrossRef]

- Mamlouk, D.; Gullo, M. Acetic Acid Bacteria: Physiology and Carbon Sources Oxidation. Indian J. Microbiol. 2013, 53, 377–384. [CrossRef]

- Soumahoro, S.; Goualie, B.G.; Adom, J.N.; Ouattara, H.G.; Koua, G.; Doue, G.G.; Niamke, S.L. Effects of Culture Conditions on Acetic Acid Production by Bacteria Isolated from Ivoirian Fermenting Cocoa (Theobroma Cacao L.) Beans. J. App. Bioscience. 2016, 95, 8981. [CrossRef]

- El-Askri, T.; Yatim, M.; Sehli, Y.; Rahou, A.; Belhaj, A.; Castro-Mejías, R.; Durán-Guerrero, E.; Hafidi, M.; Rachid, Z. Screening and Characterization of New Acetobacter Fabarum and Acetobacter Pasteurianus Strains with High Ethanol–Thermo Tolerance and the Optimization of Acetic Acid Production. Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 1741. [CrossRef]

- Lisdiyanti, P.; Kawasaki, H.; Seki, T.; Yamada, Y.; Uchimura, T.; Komagata, K. Systematic Study of the Genus Acetobacter with Descriptions of Acetobacter Indonesiensis Sp. Nov., Acetobacter Tropicalis Sp. Nov., Acetobacter Orleanensis (Henneberg 1906) Comb. Nov., Acetobacter Lovaniensis (Frateur 1950) Comb. Nov., and Acetobacter Estunensis (Carr 1958) Comb. Nov. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 46, 147–165. [CrossRef]

- Gullo, M.; Giudici, P. Acetic Acid Bacteria in Traditional Balsamic Vinegar: Phenotypic Traits Relevant for Starter Cultures Selection. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 125, 46–53. [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Cao, X.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Hou, L. Genome Shuffling to Improve Fermentation Properties of Acetic Acid Bacterium by the Improvement of Ethanol Tolerance. Int. J. of Food. Sci. Tech. 2012, 47, 2184–2189. [CrossRef]

- Raspor, P.; Goranovic, D. Biotechnological Applications of Acetic Acid Bacteria. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2008, 28, 101–124. [CrossRef]

- Cleenwerck, I.; De Vos, P. Polyphasic Taxonomy of Acetic Acid Bacteria: An Overview of the Currently Applied Methodology. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 125, 2–14. [CrossRef]

- Hussenet, C. Instrumentation, modélisation et automatisation de fermenteurs levuriers à destination oenologique. Génie des procédés, L’UNIVERSITE PARIS-SACLAY: FRANCE, 2017.

- Acourene, S.; Ammouche, A.; Djaafri, K. Valorisation des rebuts de dattes par la production de la levure boulangère, de l’alcool et du vinaigre. Sciences & Technologie. C, Biotechnologies 2008, 38–45.

- Saeki, A.; TaniguchiI, M.; Matsushita, K.; Toyama, H.; Theeragool, G.; Lotong, N.; Adachi, O. Microbiological Aspects of Acetate Oxidation by Acetic Acid Bacteria, Unfavorable Phenomena in Vinegar Fermentation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1997, 61, 317–323. [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, R.; Delvigne, F.; Thonart, P. Flow-Cytometric Assessment of Damages to Acetobacter Senegalensis during Freeze-Drying Process and Storage. Acetic Acid Bacteria 2013, 2, 10. [CrossRef]

| Concentration | Sample Volume | |

|---|---|---|

| 2X oneTaq standard buffer | 2 X | 25 µl |

| Amorce 1 (avant) | 10 µM | 5 µl |

| Amorce 2 (inverse) | 10 µM | 5 µl |

| ADN | Ca. 10 ng/µl | 3 µl |

| Distilled sterile water | - | 12 µl |

| Total reaction volume for each amplification | 50 µl | |

| Reference Type Strain | Isolation Source & Country | 16S Data1 | Genome Data | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A. cerevisiae LMG 1625T | Beer (ale) in storage; Canada |

AJ419843 | LHZA01000074 | Cleenwerck et al.[39] |

| 2 | A. cibinongensis NRIC 0482T | montana (fruit); Indonesia |

AB681085 | BAOZ01000003 | Lisdiyanti et al.[40] |

| 3 | A. conturbans LMG 1627T | Laboratory-scale cider fermentations, UK | MN744433 | WOSY01000049 | Sombolestani et al. [16] |

| 4 | A. ghanensis 18895T | Traditional heap fermentations of cocoa beans; Ghana | EF030713 | BAPC01000052 | Cleenwerck et al. [12] |

| 5 | A. indonesiensis 16471T | Fruit of Annona muricata; Indonesia | AB032356 | BJXQ01000038 | Lisdiyant et al.[41] |

| 6 | A. lambici LMG 27439T | fermenting lambic beer ; Belgium | HF969863 | WOTD01000082 | Spitaels et al.[42] |

| 7 | A. malorum LMG 1746T | Rotting apple ; Belgium | AJ419844 | LHZC01000018 | Cleenwerck et al.[39] |

| 8 | A. nitrogenifigens DSM 23921T | Kombucha tea ; India | AY669513 | BAPG01000028 | Dutta & Gachhui.[43] |

| 9 | A. okinawensis JCM 25146T | Sugarcane (stem); Japon | AB665068 | BAJU01000075 | Lino et al.[21] |

| 10 | A. orientalis NRIC 0481T | Canna (flower) ; Indonesia |

AB681086 | BAPI01000013 | Lisdiyanti et al.[40] |

| 11 | A. sacchari VTH-Ai14T | stems of sugarcane; Thailand |

LC103252 | LC103252 | Vu et al.[44] |

| 12 | A. senegalensis LMG 23690T | mango fruit ; Senegal | AY883036 | LHZU01000060 | Ndoye et al.[8] |

| 13 | A. syzygii NBRC 16604T | Malay rose apple (fruit); Indonesia | AB681084 | BJVT01000030 | Lisdiyanti et al.[40] |

| 14 | A. thailandicus BCC 15839T | flower of the blue trumpet vine; Thailand | AB937775 | Not available | Pitiwittayakul et al.[45] |

| 15 | A. tropicalis LMG 19825T | Coconut juice; Indonesia | AB032354 | LHZQ01000125 | Lisdiyanti et al.[40] |

| Test | Morphology | Color | Motility | Gram Staining | Catalase | Oxidase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OYA10 | Irregular | Brown | + | - | + | - |

| OYA2 | Irregular | Brown | + | - | + | - |

| OYA9 | regular | Brown | + | - | + | - |

| OYA6 | Irregular | Brown | + | - | + | - |

| OYA7 | Irregular | Brown | + | - | + | - |

| Strain of Acetic Acid Bacteria | Fermentation Time (h) |

Initial Alcohol (g/L) |

Final Alcohol (g/L) |

Acetic Acid Produced (g/L) |

Qp (g/L/h) |

Yp⁄s (g/g) |

Conversion (%) |

η (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OYA6 | 576 | 92.6 ± 3.43 a | 5.18 ± 0.13 a | 80.67 ± 2.1 c | 0.14 | 0.92 | 94.41 | 67.85 |

| OYA7 | 576 | 92.6 ± 3.43 a | 10.34 ± 0.26 b | 70.26 ± 0.9 a | 0.12 | 0.85 | 88.83 | 62.8 |

| OYA10 | 576 | 92.6 ± 3.43 a | 10.49 ± 0.55 b | 68.7 ± 1.51 ab | 0.12 | 0.84 | 88.67 | 61.52 |

| OYA9 | 576 | 92.6 ± 3.43 a | 10.61 ± 1.69 b | 67.22 ± 0.37 b | 0.12 | 0.82 | 88.54 | 60.28 |

| OYA2 | 576 | 92.6 ± 3.43 a | 11.2 ± 1.15 b | 70.11 ± 1.69 a | 0.12 | 0.86 | 88.54 | 62.88 |

| Isolate / Strain | 16S rDNA-Based Identification | 16S Genbank Accession | Stress at 40°C (Temperature) | Stress at 10° & 15° (v/v) of Alcohol | Acetic Acid Produced (g/L) | Yp⁄s (g/g) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | OYA2 | A. tropicalis & A. senegalensis (100%) | PP359646 | doesn't grow | resistant | 70.11 ± 1.69 | 0.86 |

| 2 | OYA6 | A. tropicalis (99.7%) | PP359647 | still grow | resistant | 80.67 ± 2.1 | 0.92 |

| 3 | OYA7 | A. syzygii (99.7%) | PP359648 | doesn't grow | resistant | 70.26 ± 0.9 | 0.85 |

| 4 | OYA9 | A. tropicalis & A. senegalensis (100%) | PP359644 | doesn't grow | resistant | 67.22 ± 0.37 | 0.82 |

| 5 | OYA10 | A. tropicalis & A. senegalensis (100%) | PP359645 | doesn't grow | resistant | 68.7 ± 1.51 | 0.84 |

| 6 | CWBI-B4181 (=LMG 23690T =DSM 18889T) | A. senegalensis | AY883036 | still grow | resistant | - | Up to 0.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).