Submitted:

08 January 2025

Posted:

10 January 2025

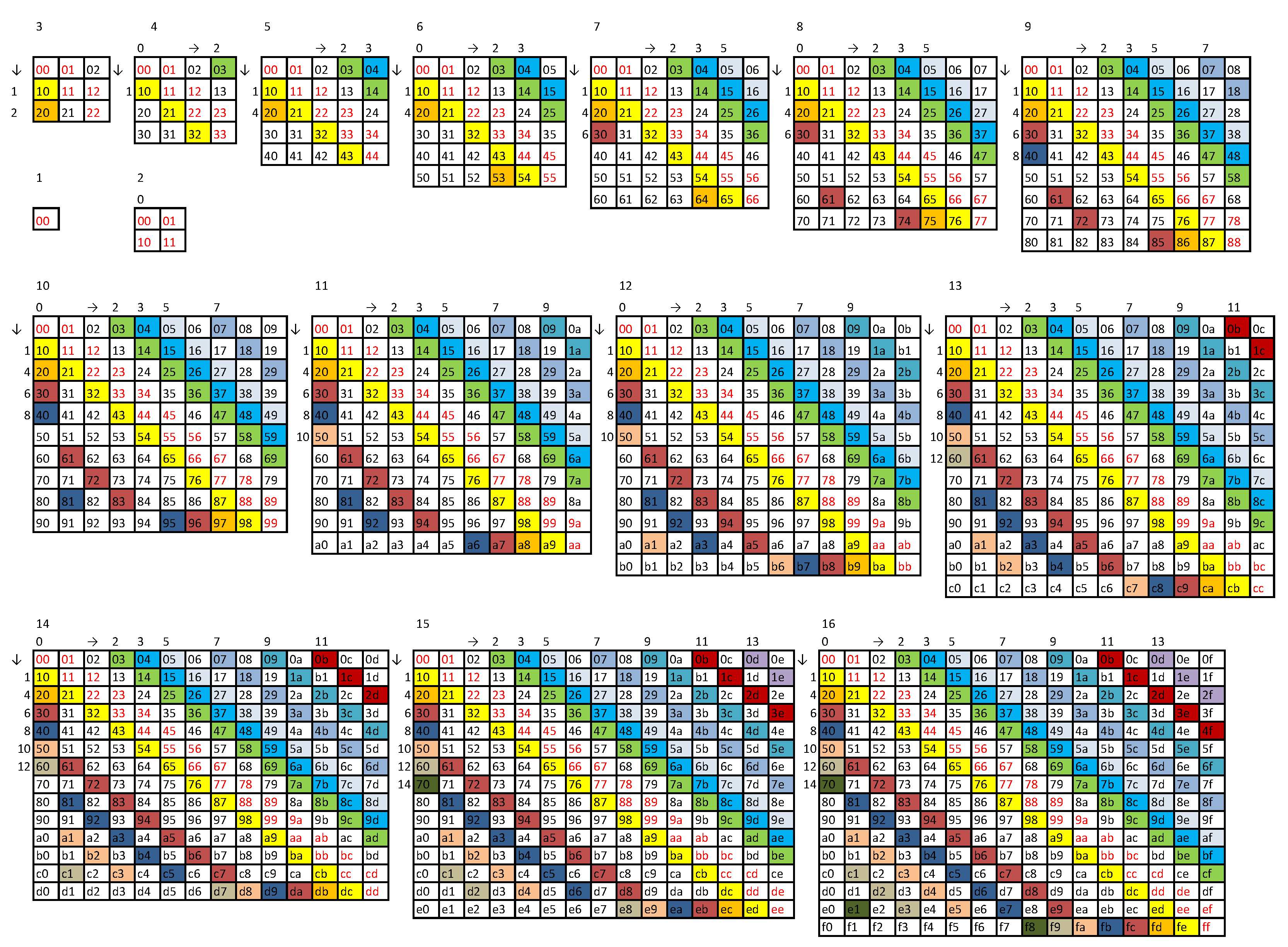

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

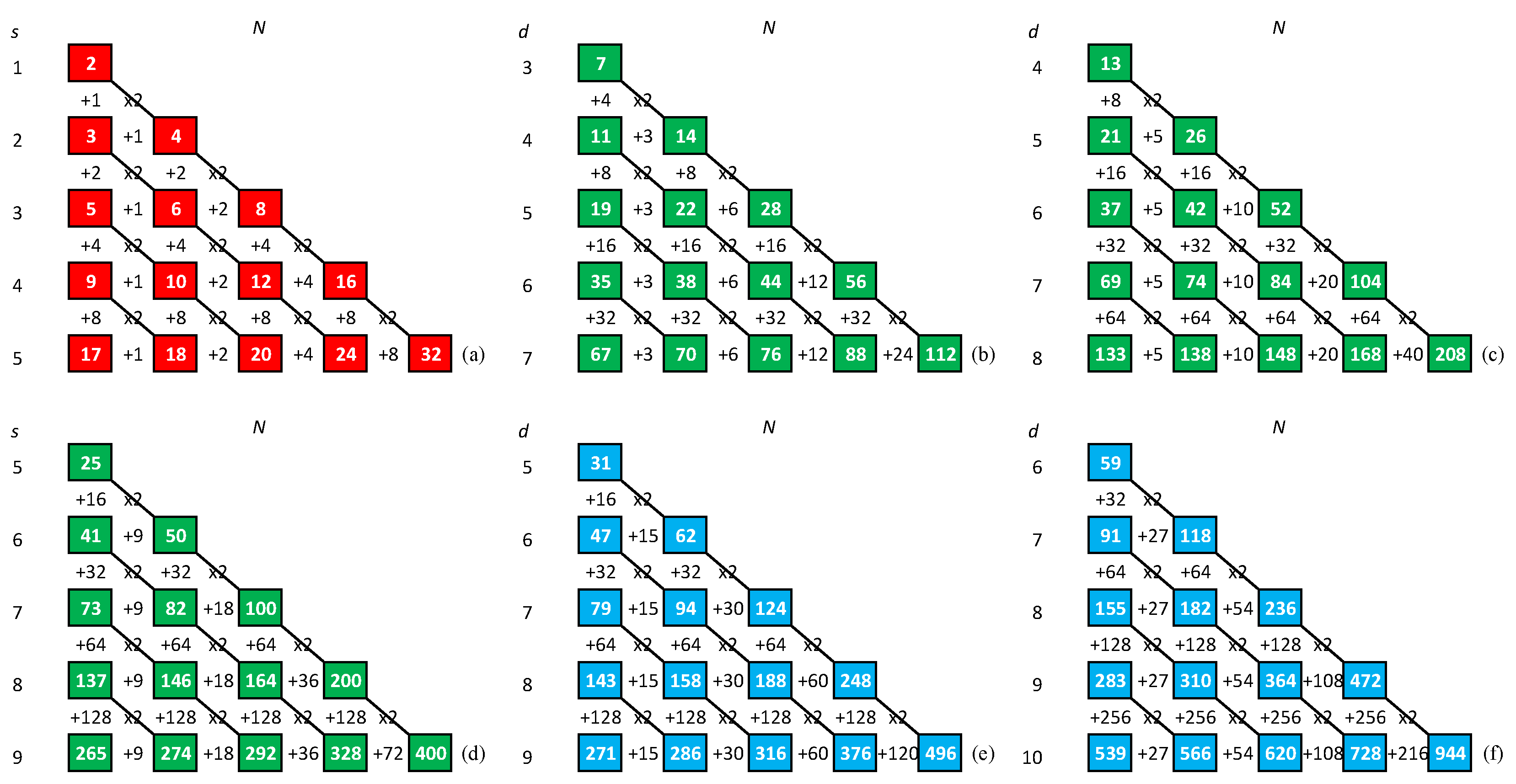

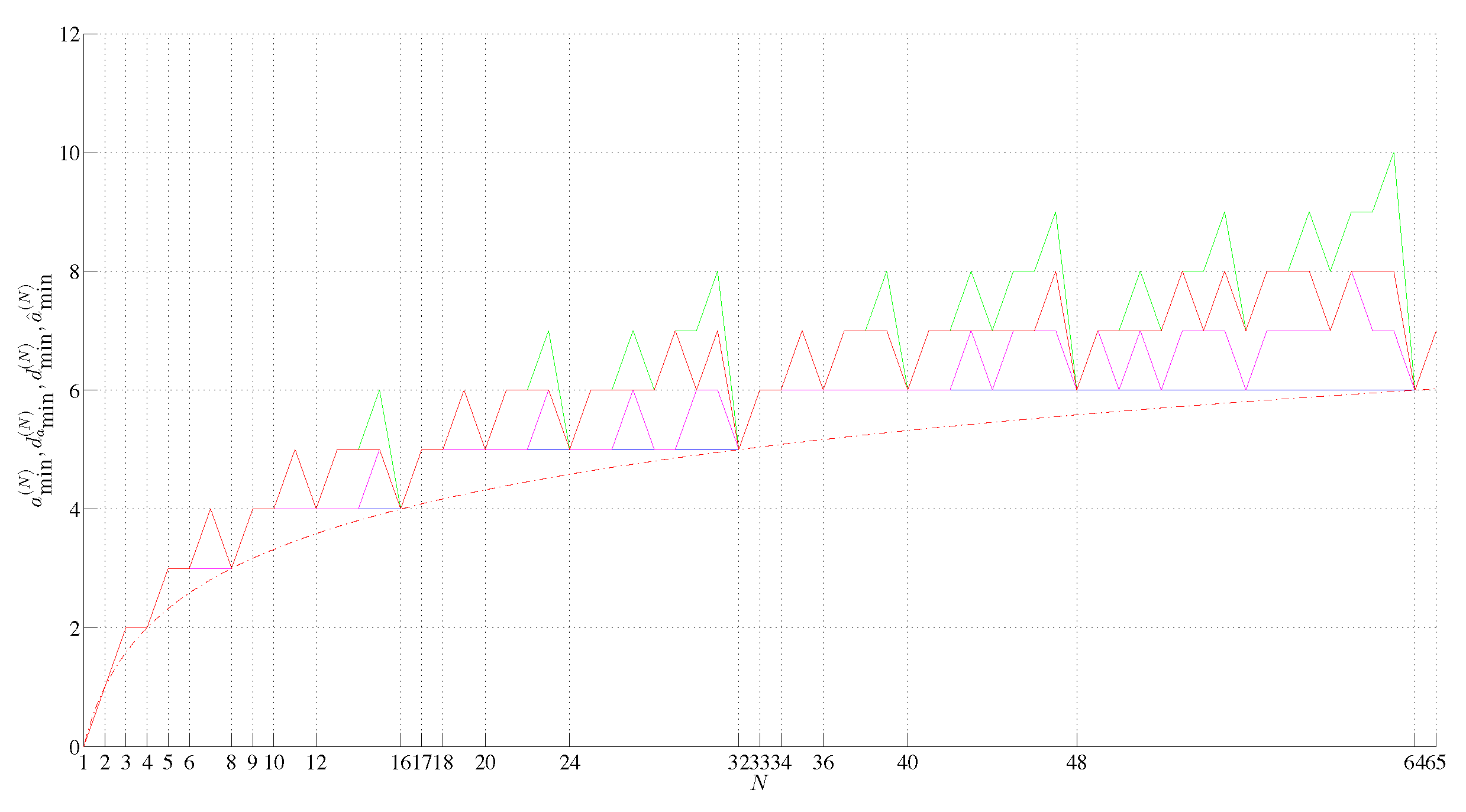

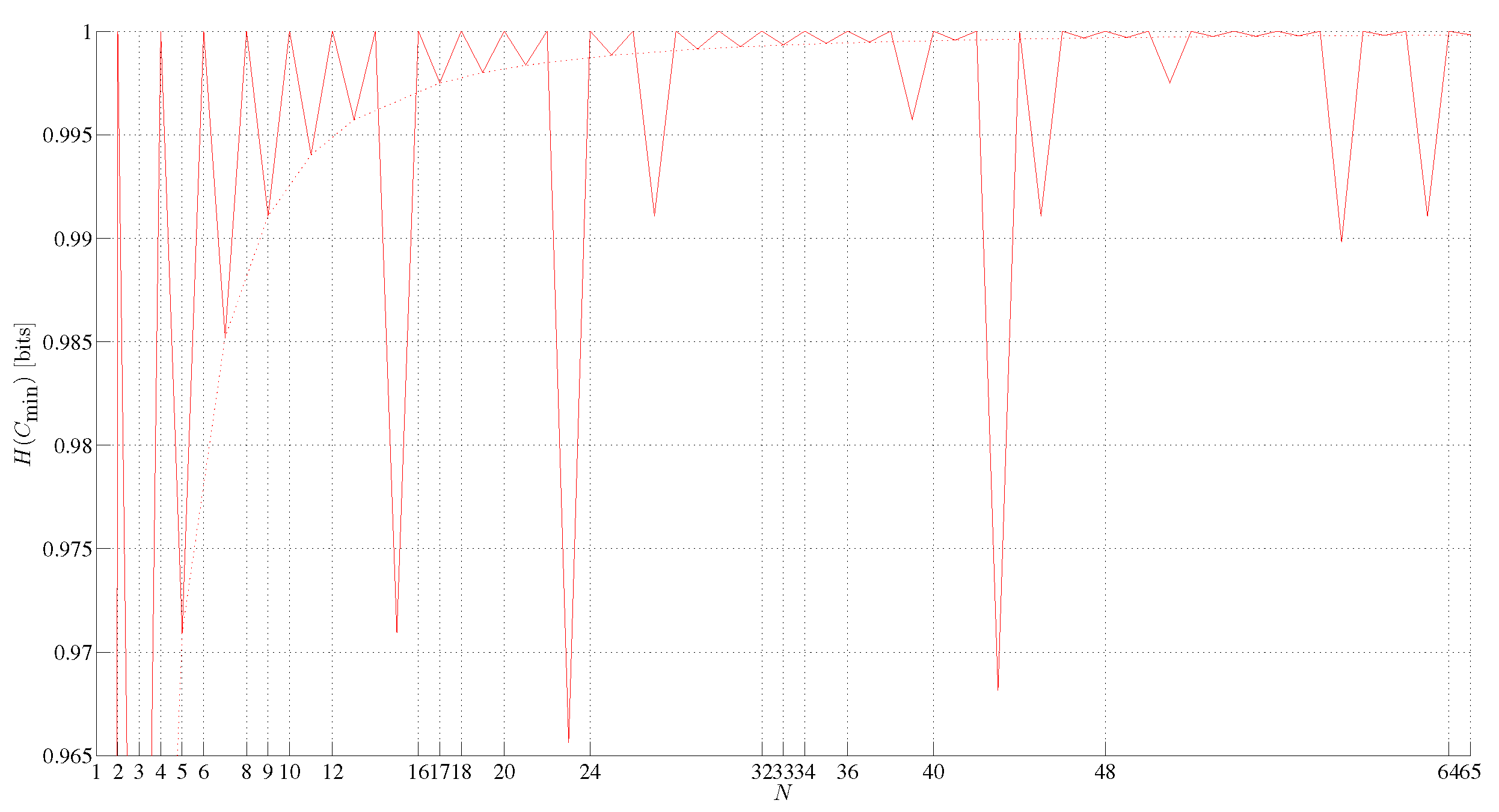

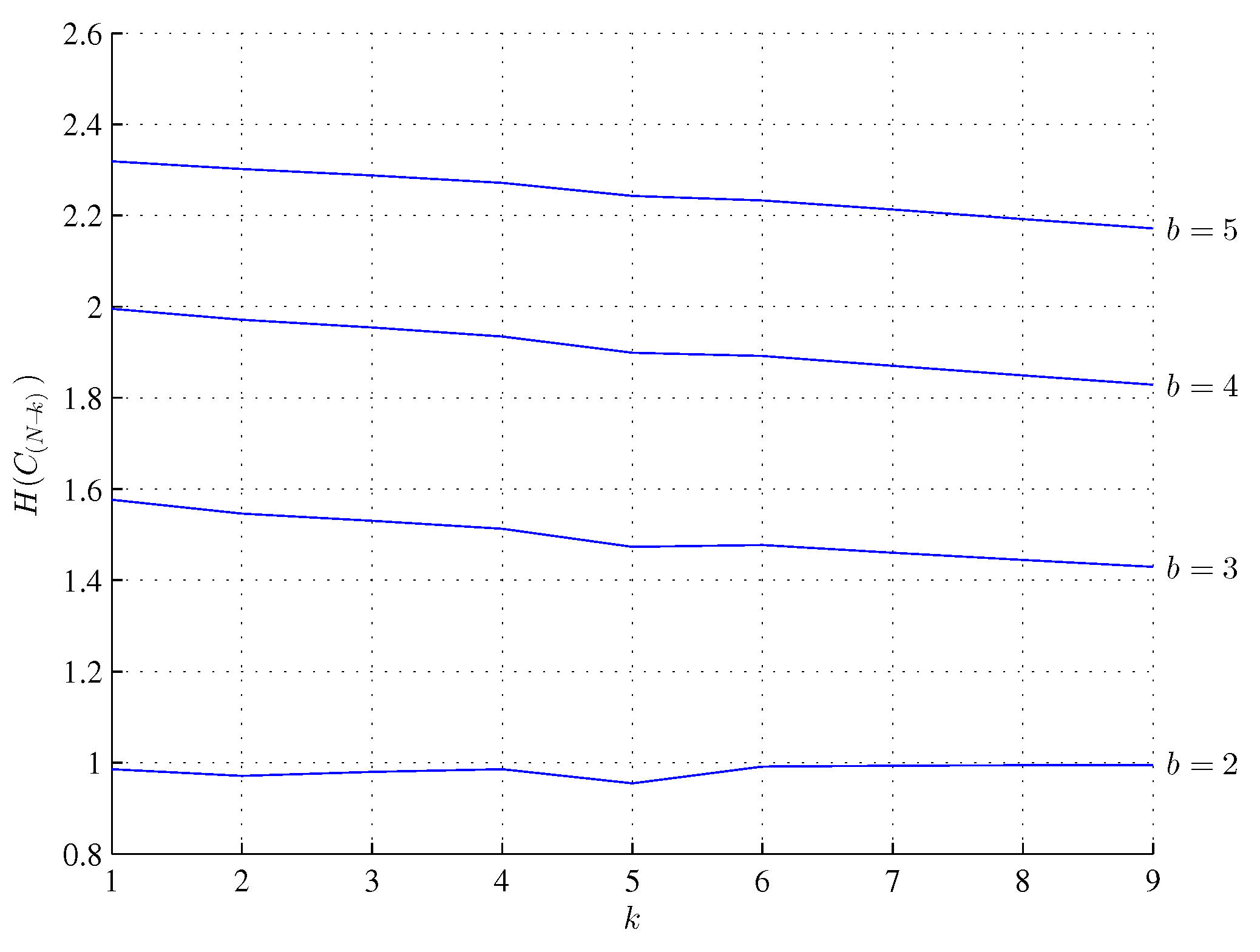

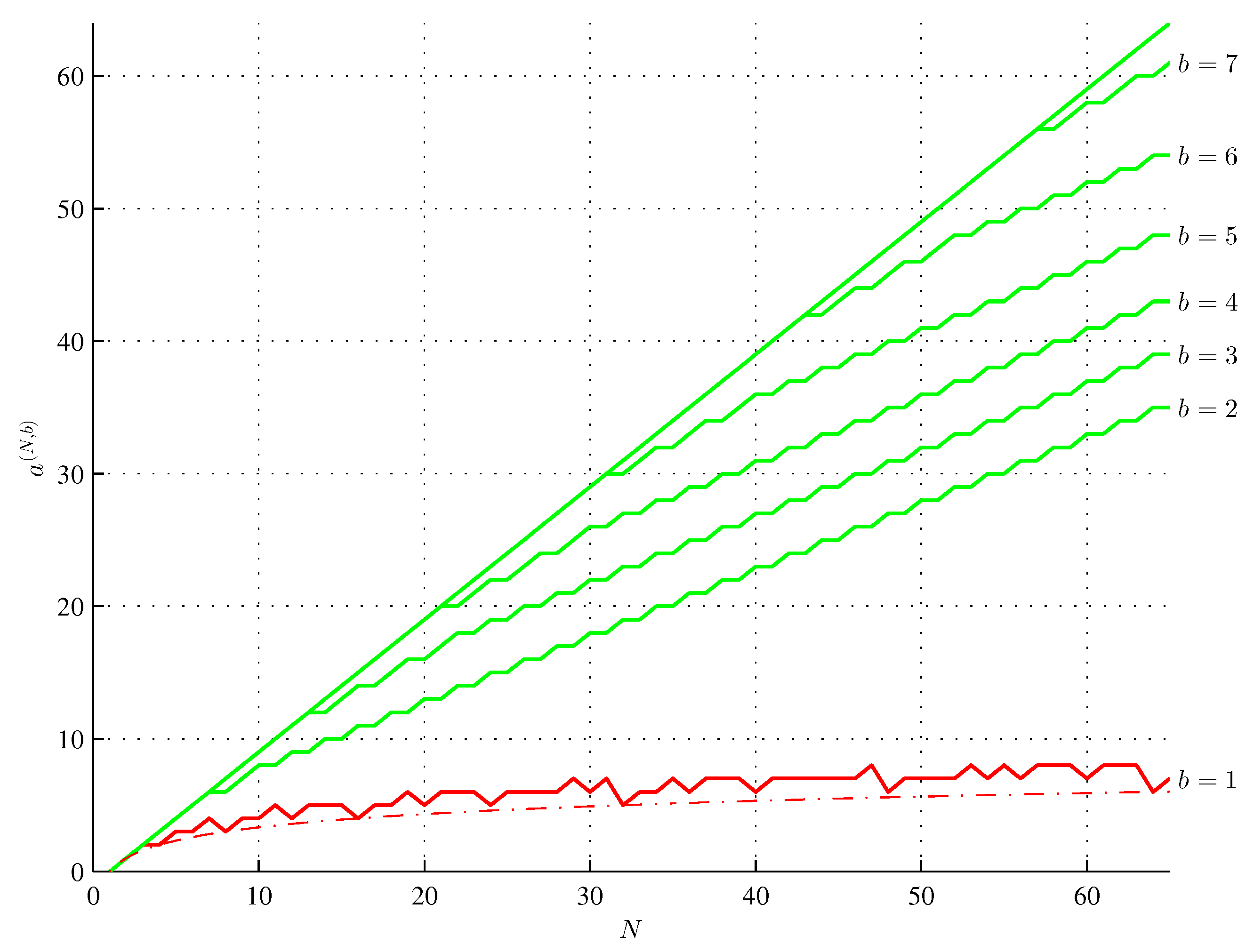

Assembly theory bridges the gap between evolutionary biology and physics by providing a framework to quantify the generation and selection of novelty in biological systems. We formalize the assembly space as an acyclic digraph of strings with 2-in-regular assembly steps vertices and provide a novel definition of the assembly index. In particular, we show that the upper bound of the assembly index depends quantitatively on the number b of unit-length strings, and the longest length N of a string that has the assembly index of N − k is given by N(N−1) = b2 + b + 1 and by N(N−k) = b2 + b + 2k for 2 ≤ k ≤ 9. We also provide particular forms of such maximum assembly index strings. For k = 1, such odd-length strings are nearly balanced, and there are four such different strings if b = 2 and seventy-two if b = 3. We also show that each k copies of an n-plet contained in a string decrease its assembly index at least by k(n − 1) − a, where a is the assembly index of this n-plet. We show that the minimum assembly depth satisfies d min(N) = ⌈log2(N)⌉, for all b, and is the assembly depth of a maximum assembly index string. We also provide the general formula for the lengths of the minimum assembly index strings having only one independent assembly step in their assembly spaces. Since these results are also valid for b = 1, assembly theory subsumes information theory.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

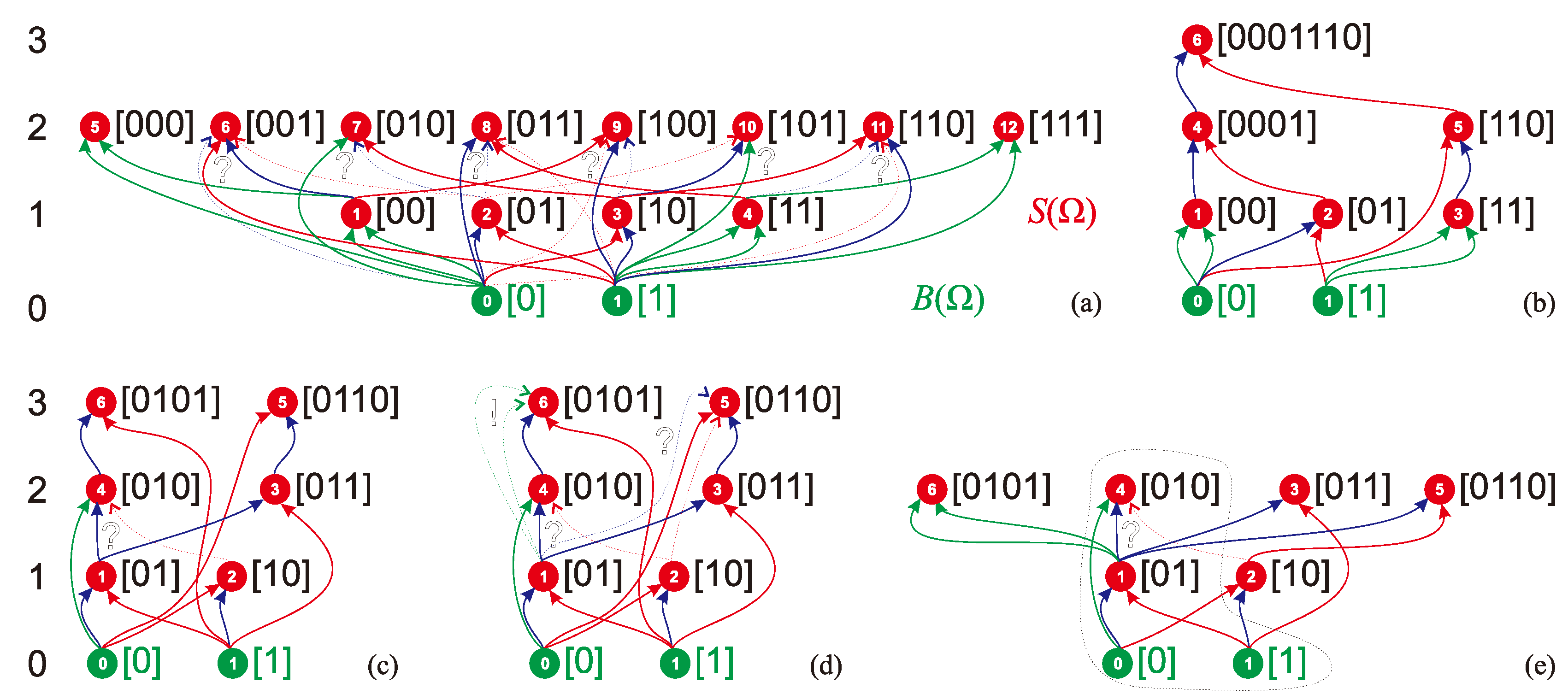

2. Rudiments

- k copies of a doublet in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

- k copies of a triplet in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

- k copies of a minimum ASI quadruplet in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

- k copies of a maximum ASI quadruplet in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

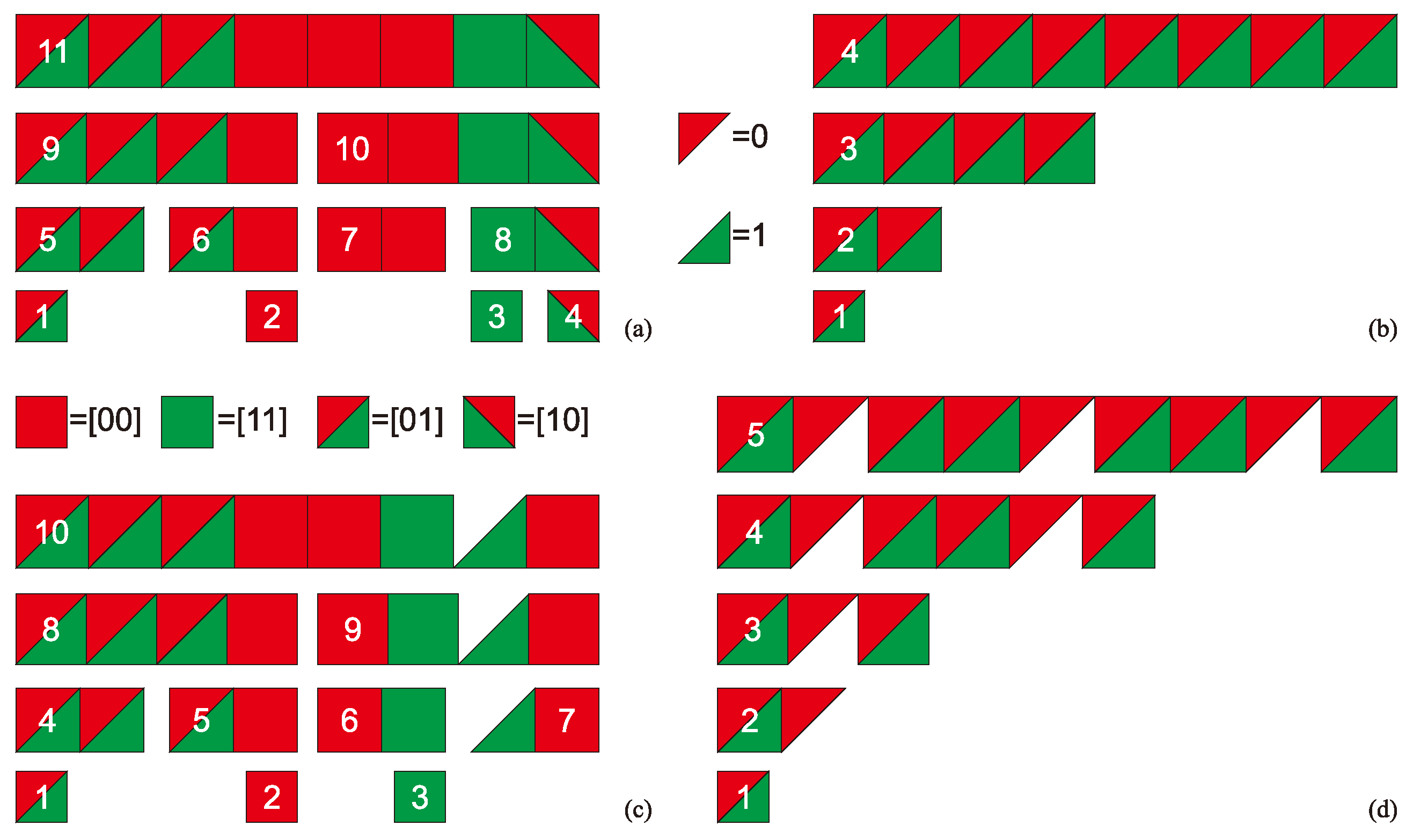

3. Minimum Assembly Depth, Assembly Depth and Entropy of a Minimum Assembly Index, Minimum Assembly Index, and Depth Index

- the of minimum ASI strings having ASI equal to DPI cannot contain strings assembled in independent assembly steps,

- the s of other minimum ASI strings can contain at least two such strings, and therefore

- the assembly space of a maximum ASI string will tend to maximize the number of strings assembled in independent assembly steps in the , taking into account the saturation of the as it cannot contain more than distinct n-plets, and hence to minimize the possible ASD.

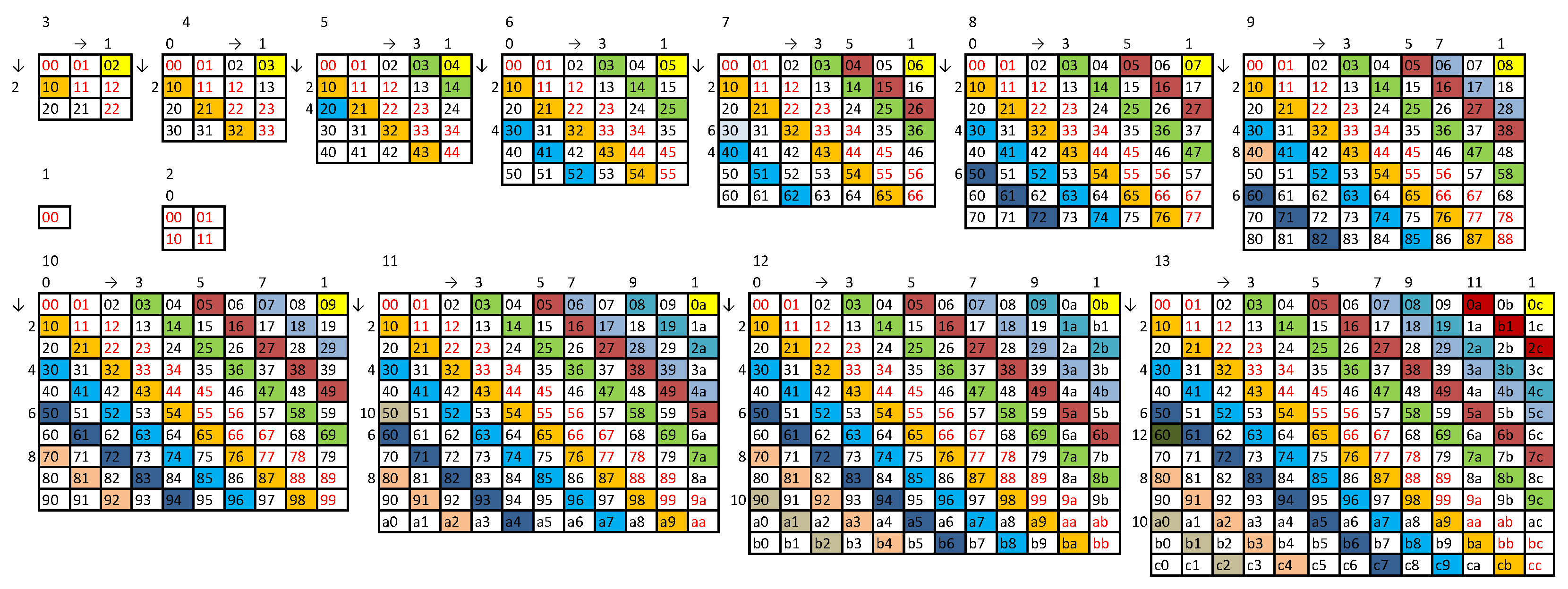

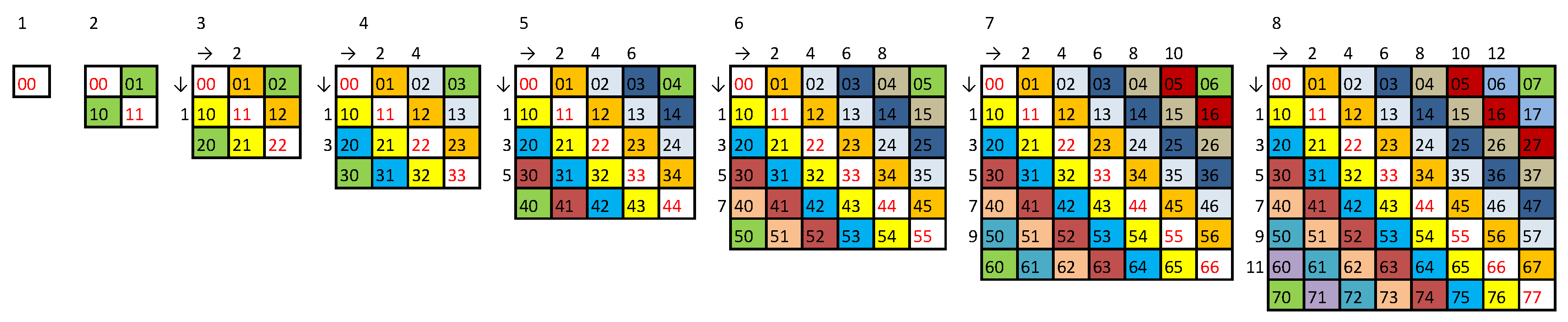

4. Maximum Assembly Index Strings

5. A Method of Generating a Maximum Assembly Index String

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Method A for Generating C (N-1) String

Appendix B. Method B for Generating C (N-1) String

- we check subsequent subdiagonals until we find one that does not contain a doublet present in the string formed so far, we append it at the end of this string and proceed to step 2;

- we check subsequent superdiagonals until we find one that does not contain a doublet present in the string formed so far, we append it at the end of this string and proceed to step 1.

Appendix C. A String with Exactly Two Copies of All Doublets and No Repeated Triplets

Appendix D. Proof of C (N-1) String Theorem

Appendix E. Proof of C (N-k) String Theorem

Appendix F. Assembly Spaces of Minimum Assembly Index Strings

| N | MIA pathway | MBL pathway (Hamming weight ) | String | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | (1) | ||

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | (1) | ||

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | (2) | ||

| 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | (2) | ||

| 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | (3) | ||

| 7 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | (3) | ||

| 8 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | (4) | ||

| 9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | (4) | ||

| 10 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | (5) | ||

| 11 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | (5) | ||

| 12 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | (6) | ||

| 13 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | (6) | ||

| 14 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | (7) | ||

| 15 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | (6) | ||

| 16 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | (8) | ||

| 17 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | (8) | ||

| 18 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | (9) | ||

| 19 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (9) | ||

| 20 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | (10) | ||

| 21 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (10) | ||

| 22 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (11) | ||

| 23 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | (9) | ||

| 24 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | (12) | ||

| 25 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (12) | ||

| 26 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (13) | ||

| 27 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | (12) | ||

| 28 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (14) | ||

| 29 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (14) | ||

| 30 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | (15) | ||

| 31 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | (15) | ||

| 32 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | (16) | ||

| 33 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | (16) | ||

| 34 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | (17) | ||

| 35 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (17) | ||

| 36 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | (18) | ||

| 37 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (18) | ||

| 38 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (19) | ||

| 39 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| 40 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||

| 41 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | |||

| 42 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | |||

| 43 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | (17) | ||

| 44 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (22) | ||

| 45 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | (20) | ||

| 46 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | (23) | ||

| 47 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | (23) | ||

| 48 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | (24) | ||

| 49 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | (24) | ||

| 50 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (25) | ||

| 51 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | (24) | ||

| 52 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (26) | ||

| 53 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | (26) | ||

| 54 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | (27) | ||

| 55 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | (27) | ||

| 56 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (28) | ||

| 57 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | (28) | ||

| 58 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | (29) | ||

| 59 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | (26) | ||

| 60 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | (30) | ||

| 61 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 9 | (30) | ||

| 62 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | (31) | ||

| 63 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | (28) | ||

| 64 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | (32) | ||

| 65 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | (32) | ||

References

- Levin, M. Self-constructing bodies, collective minds: the intersection of cs, cognitive bio, and philosophy. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, M. Self-Improvising Memory: A Perspective on Memories as Agential, Dynamically Reinterpreting Cognitive Glue. Entropy 2024, 26, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. Hoffman, The case against reality: Why evolution hid the truth from our eyes (WW Norton & Company, 2019).

- Hoffman, D.D.; Singh, M. Perception, Evolution, and the Explanatory Scope of Scientific Theories. Journal of Consciousness Studies 2024, 31, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brukner, Č. A No-Go Theorem for Observer-Independent Facts. Entropy 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukaszyk, S.; Tomski, A. Omnidimensional Convex Polytopes. Symmetry 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukaszyk, S. Shannon entropy of chemical elements. European Journal of Applied Sciences 2024, 11, 443–458. [Google Scholar]

- Łukaszyk, S. The Imaginary Universe (on the Three Complementary Sets of Measurement Units Defining Three Dark Electrons). 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, A.D. A relation between pythagorean triples and the special theory of relativity. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sporn, H. Pythagorean triples using the relativistic velocity addition formula. The Mathematical Gazette 2024, 108, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukaszyk, S. Metallic Ratios and Angles of a Real Argument. IPI Letters 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.M.; Murray, A.R.G.; Cronin, L. A probabilistic framework for identifying biosignatures using Pathway Complexity, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical. Physical and Engineering Sciences 2017, 375, 20160342. [Google Scholar]

- S. Imari Walker, L. S. Imari Walker, L. Cronin, A. Drew, S. Domagal-Goldman, T. Fisher, and M. Line, Probabilistic biosignature frameworks, in Planetary Astrobiology, edited by V. Meadows, G. Arney, B. Schmidt, and D. J. Des Marais (University of Arizona Press, 2019) pp. 1–1.

- V. S. Meadows, G. N. Arney, B. E. Schmidt, and D. J. Des Marais, eds., Planetary astrobiology, University of Arizona space science series (The University of Arizona Press ; Houston : Lunar and Planetary Institute, Tucson, 2020) oCLC: 1151198948.

- Liu, Y.; Mathis, C.; Bajczyk, M.D.; Marshall, S.M.; Wilbraham, L.; Cronin, L. Exploring and mapping chemical space with molecular assembly trees. Science Advances 2021, 7, eabj2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, S.M.; Mathis, C.; Carrick, E.; Keenan, G.; Cooper, G.J.T.; Graham, H.; Craven, M.; Gromski, P.S.; Moore, D.G.; Walker, S.I.; Cronin, L. Identifying molecules as biosignatures with assembly theory and mass spectrometry. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.M.; Moore, D.G.; Murray, A.R.G.; Walker, S.I.; Cronin, L. Formalising the Pathways to Life Using Assembly Spaces. Entropy 2022, 24, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Czégel, D.; Lachmann, M.; Kempes, C.P.; Walker, S.I.; Cronin, L. Assembly theory explains and quantifies selection and evolution. Nature 2023, 622, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirasek, M.; Sharma, A.; Bame, J.R.; Mehr, S.H.M.; Bell, N.; Marshall, S.M.; Mathis, C.; MacLeod, A.; Cooper, G.J.T.; Swart, M.; Mollfulleda, R.; Cronin, L. Investigating and Quantifying Molecular Complexity Using Assembly Theory and Spectroscopy. ACS Central Science 2024, 10, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łukaszyk, S.; Bieniawski, W. Assembly Theory of Binary Messages. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubitzek, S.; Schatten, A.; König, P.; Marica, E.; Eresheim, S.; Mallinger, K. Autocatalytic Sets and Assembly Theory: A Toy Model Perspective. Entropy 2024, 26, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Łukaszyk, On the "Assembly Theory and its Relationship with Computational Complexity" (2024d).

- P. Francis, Dilexit nos: Encyclical letter on the human and divine love of the heart of jesus christ (2024), accessed: 2024-11-01.

- Book of John [1.3] (c90).

- C. P. Kempes, M. Lachmann, A. Iannaccone, G. M. Fricke, M. R. Chowdhury, S. I. Walker, and L. Cronin, Assembly Theory and its Relationship with Computational Complexity (2024).

- L. Cronin, Exploring assembly index of strings is a good way to show why assembly & entropy are intrinsically different., https://x.com/leecronin/status/1850289225935257665 (2024), accessed: 2024-11-01.

- S. Pagel, A. Sharma, and L. Cronin, Mapping Evolution of Molecules Across Biochemistry with Assembly Theory (2024).

- S. Łukaszyk, Black Hole Horizons as Patternless Binary Messages and Markers of Dimensionality, in Future Relativity, Gravitation, Cosmology (Nova Science Publishers, 2023) Chap. 15, pp. 317–374.

- Łukaszyk, S. Life as the explanation of the measurement problem. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2024, 2701, 012124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitin, G.J. Randomness and Mathematical Proof. Scientific American 1975, 232, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vopson, M.M. The second law of infodynamics and its implications for the simulated universe hypothesis. AIP Advances 2023, 13, 105308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Chaitin, Proving Darwin: Making Biology Mathematical (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2013).

| s | ... | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 14 | 28 | 56 | 112 | 224 | ... | |

| 15 | 30 | 60 | 120 | 240 | 480 | ||||||

| 23 | 46 | 92 | 184 | 368 | |||||||

| 3 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 11 | 22 | 44 | 88 | 176 | ... | |

| 27 | 54 | 108 | 216 | 432 | |||||||

| 43 | 86 | 172 | 344 | ||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 13 | 26 | 52 | 104 | 208 | ... | ||

| 45 | 90 | 180 | 360 | ... | |||||||

| 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 3 | 19 | 38 | 76 | 152 | ... | |

| 51 | 102 | 204 | 408 | ||||||||

| 83 | 166 | 332 | |||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 5 | 21 | 42 | 84 | 168 | ... | ||

| 85 | 170 | 340 | ... | ||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 9 | 25 | 50 | 100 | 200 | ... | ||

| 5 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 3 | 35 | 70 | 140 | ... | |

| 99 | 198 | 396 | |||||||||

| 163 | 326 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 5 | 37 | 74 | 148 | ... | ||

| 165 | 330 | ... | |||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 9 | 41 | 82 | 164 | ... | ||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 17 | 49 | 98 | 196 | ... | ||

| 6 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 3 | 67 | 134 | ... | |

| 195 | 390 | ||||||||||

| 323 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 5 | 69 | 138 | 276 | ||

| 325 | 650 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 9 | 73 | 146 | ... | ||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 17 | 81 | 162 | ... | ||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 33 | 97 | 194 | ... | ||

| 7 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 3 | 131 | ... | |

| 387 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 5 | 133 | 266 | ||

| 645 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 9 | 137 | ... | ||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 17 | 145 | ... | ||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 33 | 161 | ... | ||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 65 | 193 | ... |

| N | last | last | last | last | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N | N | N | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N | N | N | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N | N | Y | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N | N | N | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N | N | Y | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| 6 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N | Y | N | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| 7 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N | Y | Y | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | N | N | N | 3 | 6 | 7 | 7 | |

| 9 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | N | N | Y | 4 | 7 | 8 | 8 | |

| 10 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | N | Y | N | 4 | 8 | 9 | 9 | |

| 11 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | N | Y | Y | 5 | 8 | 10 | 10 | |

| 12 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Y | N | N | 4 | 9 | 11 | 11 | |

| 13 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Y | N | Y | 5 | 9 | 12 | 12 | |

| 14 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Y | Y | N | 5 | 10 | 12 | 13 | |

| 15 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Y | Y | Y | 6 | 10 | 13 | 14 | |

| 16 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | N | N | N | N | 4 | 11 | 14 | 15 |

| 17 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | N | N | N | Y | 5 | 11 | 14 | 16 |

| 18 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | N | N | Y | N | 5 | 12 | 15 | 17 |

| 19 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | N | N | Y | Y | 6 | 12 | 15 | 18 |

| 20 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | N | Y | N | N | 5 | 13 | 16 | 19 |

| 21 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | N | Y | N | Y | 6 | 13 | 16 | 20 |

| 22 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | N | Y | Y | N | 6 | 14 | 17 | 20 |

| 23 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | N | Y | Y | Y | 7 | 14 | 17 | 21 |

| 24 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Y | N | N | N | 5 | 15 | 18 | 22 |

| 25 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Y | N | N | Y | 6 | 15 | 18 | 22 |

| 26 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Y | N | Y | N | 6 | 16 | 19 | 23 |

| 27 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Y | N | Y | Y | 7 | 16 | 19 | 23 |

| 28 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Y | Y | N | N | 6 | 17 | 20 | 24 |

| 29 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | 7 | 17 | 20 | 24 |

| 30 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Y | Y | Y | N | 7 | 18 | 21 | 25 |

| 31 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 | 18 | 21 | 25 |

| 32 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | N | N | N | N | 5 | 19 | 22 | 26 |

| 33 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | N | N | N | Y | 6 | 19 | 22 | 26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).