2. Rudiments

The Definition 1 and Theorems 1 and 2 were already stated in our previous studies [

20,

22]. We restate them here for clarity.

Definition 1 (Assembly Space).

An assembly space is an acyclic digraph of strings , where all unit length strings (basic symbol(s)) are inaccessible source vertices and the remaining strings are 2-in-regular assembly steps vertices, E is a set of edges, and is an edge labeling map, wherein an assembly step consists of forming a new string from two, not necessarily different, strings , by concatenating them with each other, establishing edges and , and assigning, strings , to edges , e using the map ϕ as

where "∘" denotes the string concatenation (strcat) operator.

In other words, the edge labeling map (

1) has the following property

that preserves the commutativity of the assembly step, defines the concatenation order of the strings

,

in the string

being the endpoint of both edges

e and

, as - in general - for different strings

. Although the notion of a

concatenation direction is pointless for one symbol only, we consider such a degenerate case here.

Although all the

vertices are strings, it is convenient to separate this set into a set

of inaccessible source vertices, and a set

of 2-in-regular assembly steps vertices, associating them with labels

. At each assembly step

s, the cardinality of the set

S of assembly steps vertices increases by one. The relation (

1) (based on the map discussed in [

25]) is superfluous if the vertices defining the directed edges of

are strings, as any edge

unambiguously resolves to either

or

. For example, the edge

unambiguously resolves to

. However, we leave it in Definition 1 for clarity.

Definition 1 is consistent: all vertices are unique (in any standard graph, all vertices should be unique) and all are strings. Since an assembly step always consists of joining two parts only [

12], this can be thought of as the left and right fragments of the newly formed string, and those strings that can be the result of concatenation of two shorter strings are assembly step 2-in-regular vertices, while unit-length strings are inaccessible. Remarkably, the uniqueness of each vertex is a sufficient criterion to establish the admissibility of an assembly step and to introduce the notion of an assembly pool. Vertices (strings) present in the assembly space can not be

assembled again as new vertices of

, as they would not be unique.

Definition 2 (String Assembly Space). An assembly space of a string is the assembly space Definition 1 containing the vertex and all the vertices leading to the string .

There can be more than one assembly space of a string reflecting different assembly pathways leading to this string. The Definition 2 of the string assembly space provides a novel definition of the assembly index.

Definition 3 (Assembly Index). The assembly index (ASI) of a string is the minimum cardinality of the set of the assembly step vertices of all assembly spaces of the string .

Theorem 1. A quadruplet is the shortest string that allows for more than one ASI .

Proof.

provides available doublets with unit ASI. provides available triplets with ASI equal to two. Only provides quadruplets that include quadruplets with ASI equal to two, that is b quadruplets and quadruplets , while the ASI of the remaining quadruplets is three. □

For example, to assemble the quadruplet , we need to assemble the doublet and reuse it, while there is nothing available to reuse, in the case of the quadruplet .

Where the symbol value can be arbitrary, we write * assuming that it is the same within the string. If we allow for the 2nd possibility different from *, we write ★. Thus, , for example, is a placeholder for all b strings, while a placeholder for all strings.

Theorem 2. The minimum ASI as a function of N corresponds to the shortest addition chain for N (OEIS A003313) .

Proof. Strings

for which

,

can be formed in subsequent steps

s by joining the longest string assembled so far with itself until

is reached. Therefore, if

, then

. Only

strings have such ASI if

, including respectively

b and

strings

and the assembly space of each of the strings (

3) is unique. At each assembly step, its length doubles.

An addition chain for

having the shortest length

(commonly denoted as

) is defined as a sequence

of integers such that

,

for

. Hence,

and the first step in forming an addition chain for

N is always

, which is an equivalent of saying that the ASI of any doublet is one. The second step in forming an addition chain can be

,

, or

. The 1

st case does not represent the shortest addition chain but the first step, the 2

nd one corresponds to assembling a triplet based on the previously assembled doublet, and the 3

rd one corresponds to assembling a minimum ASI quadruplet (

3) from this doublet. Maximum ASI quadruplet can be assembled in a third step

, which corresponds to joining a basic symbol to a triplet. Therefore, four is the smallest number achievable in two ways according to Theorem 1.

Thus, finding the shortest addition chain for N corresponds to finding the ASI of a string containing basic symbols and/or doublets and/or triplets containing these doublets for since due to Theorem 1 only they provide the same assembly indices with no internal repetitions. □

The assembly spaces of strings of length are not unique. For example, a string can be assembled in three steps from four assembly spaces with , , , or .

We note in passing that any shortest addition chain for n starts with one, not zero, as zero is the neutral element of addition. For the same reason, two is considered the smallest prime, as one is the neutral element of multiplication. Hence, the fundamental theorem of arithmetic can be thought of as the shortest multiplication chain for n.

Theorem 3. The strings can contain at most two distinct symbols if . Other minimum ASI strings of length can contain at most three distinct symbols if .

Proof. Minimum ASI strings of length are formed by joining the newly assembled string to itself, where a clear or mixed doublet is assembled in the first step. Minimum ASI strings of other lengths admit a doublet and a triplet containing this doublet and an additional basic symbol.

To formally prove the first part, we can also use mathematical induction on the assembly step

s. If

, then the minimum ASI strings

are doublets of the form

, where

. If

, the string contains one distinct symbol, and if

, the string contains two distinct symbols. In both cases, the string has a form (

3) and the number of distinct symbols does not exceed two. Now assume that for some

, all minimum ASI strings

contain at most two distinct symbols. We must show that

also contains at most two distinct symbols. We construct

by joining two identical minimum ASI strings

with each other. By the inductive hypothesis, each

contains at most two distinct symbols. Therefore, their concatenation also contains at most two distinct symbols. By induction, for all

, the minimum ASI string

contains at most two distinct symbols.

We will now show that other minimum ASI strings of length can contain at most three distinct symbols if . We provide the construction of minimum ASI strings with three symbols. In the first step , we assemble a doublet where and . Next, we join the existing doublet with a new symbol where . This forms a triplet , introducing a third distinct symbol and further increasing the ASI by 1. We continue assembling by joining the longest string formed so far with itself or with previously formed strings, maintaining the minimal ASI increase.

Assume a contrario that there exists a minimum ASI string of length that contains four or more distinct symbols. But, to incorporate a fourth symbol, at least one additional assembly step is required beyond what is needed for the three symbols. This additional step implies an increase in ASI, which contradicts the minimality of . Thus, Theorem 3 is proven. □

The strings having non-minimum ASI can contain all symbols. For example, the string [

26]

has ASI

and contains all five basic symbols

. We conjecture [

20] that the problem of constructing a non-minimum ASI string is NP-hard, the problem of determining the ASI of such string is NP, and hence it is an NP-complete problem.

Another quantity quantifying the complexity of a string is the assembly depth (ASD) defined [

27] as

where

, and

and

are the ASDs of two substrings

,

of the string

that were joined in step

s. For

, and if there are more assembly pathways with different depths

leading to a string, which happens if at least two independent assembly steps are possible, the minimum pathway depth is the ASD of this string. Hence, the ASD captures the notion of an

independent assembly step.

Theorem 4. If an assembly space Ω contains strings having the same (non-zero) ASD they were assembled in independent assembly steps.

Proof. Without loss of generality (w.l.o.g.) assume

a contrario that

contains two strings

,

having the same ASD, i.e.,

, that were not assembled in independent assembly steps, i.e., that

was used in the assembly of

along with a basic symbol

c in some previous step

s. Then

which contradicts our assumption and completes the proof. □

In other words, if two strings

,

in

have the same ASD, their assembly pathways are unrelated to each other; by the defining equation (

6) neither of them could have been used in the assembly pathway of the other.

Corollary 1. If the ASI and ASD of a string are equal to each other, an assembly space of this string cannot contain independent assembly steps.

Theorem 5.

The maximum length N of any string that can be assembled with the ASD (6), , satisfies

Proof. Assume

a contrario that

. Then for the ASD

, we have

which is a contradiction as all basic symbols

c are unit-length strings and

. Similarly, for

,

is also contradiction in the case of doublets, and so on. This is a consequence of the ASD Definition (

6). □

Theorem 6.

The minimum ASD as a function of a string length N is given by

where denotes the ceiling function.

Proof.

follows from the relation (

8).

satisfies both the definition (

6) and our hypothesis (

9). Similarly

. Using induction on length

N, assume that for some

, we can assemble a minimum ASD string with ASD (

9). We need to show that for

, we can assemble a string with the ASD satisfying

Since, by definition (

6), the ASD as a function of

N is monotonously nondecreasing and can increase at most by one between

N and

, we have

where we used relations (

9) and (

10). Solving the relation (

11) for

N yields

and completes the proof. □

The ASD does not have to be a monotonously nondecreasing function of the assembly step. For example

We cannot consider the ASD apart from the ASI. For example, the ASD of a string

is

even though this string can be assembled in six steps with three larger pathway depths

as

Similarly, the ASD of a string

is

as

However, the non-maximum and non-minimum ASI string

has only two doublets that can be assembled in independent steps. Hence, its ASD cannot be decreased to

In general, the that contains a -plet having the ASD d can also contain -plets having the ASD d and based on the shorter n-plets of length .

Theorem 7.

For all b the ASD of any maximum ASI string , corresponds to the minimum ASD (9) of Theorem 6, that is

Proof. Using the property of the ceiling function

valid for

, we have

The non-strict inequality (

18) corresponds to the non-strict inequality (

8) valid for any

N and any ASD. Therefore, we need to prove that the strict inequality

holds for all

strings. Assume, for contradiction, that there exists a maximum ASI string

such that

But this relation does not hold for the maximum ASI string . □

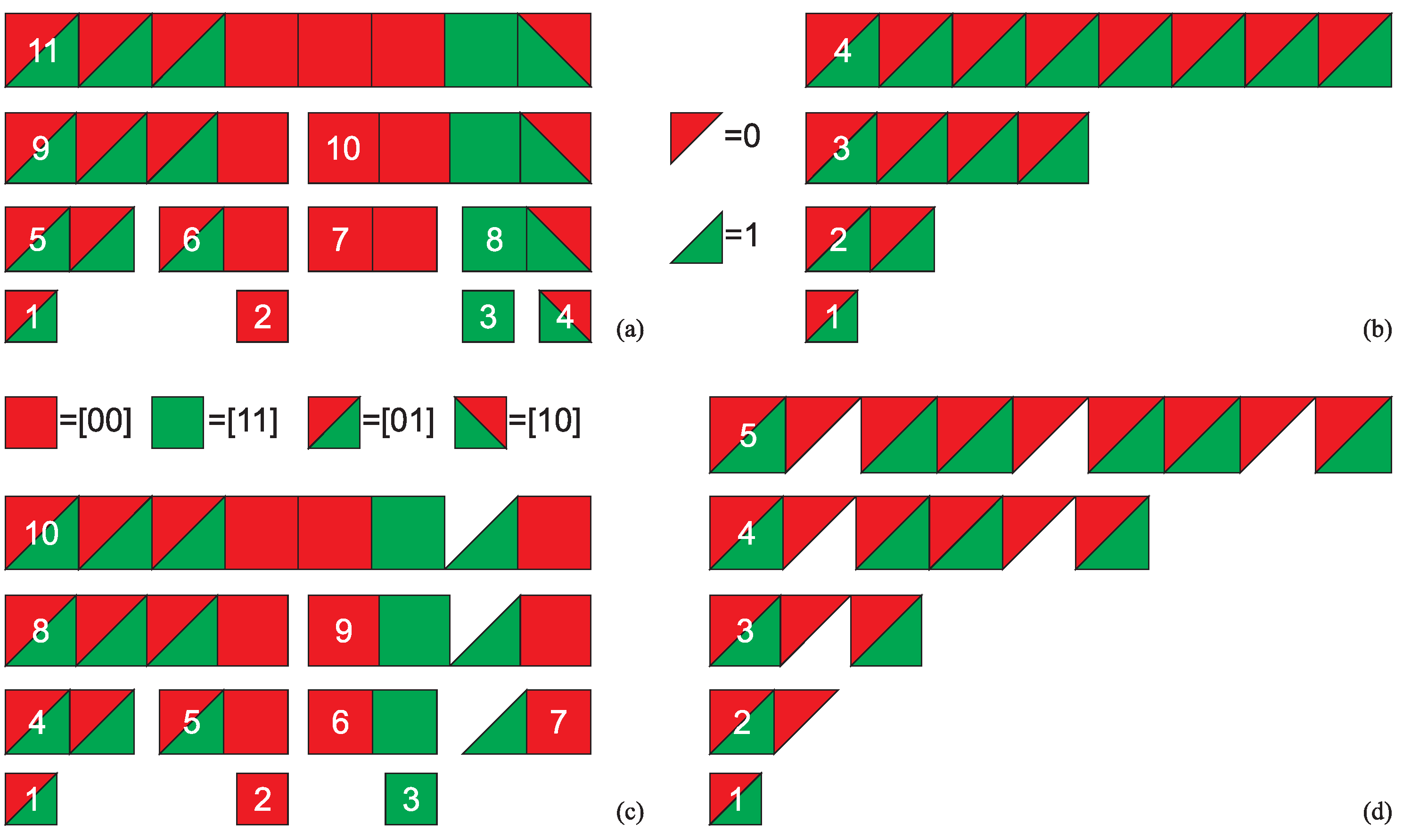

For example, as shown in

Figure 1(c,d), the string

has the ASI

and the ASD

, while the string

has smaller ASI

but larger ASD

. On the other hand, the ASD of the maximum ASI string

(

A21) and the minimum ASI string (

3), shown in

Figure 1(a,b), is the same.

Here, we introduce the following definition, which - as we shall see - is also related to the independent assembly step.

Definition 4 (Depth Index).

We call the number of steps to reach 1 starting from and assigning if is odd and otherwise (OEIS A014701) the depth index (DPI).

Unlike the minimum ASI, DPI is an analytical function of N. For example, and .

We assume that initially a new string of length

N is formed in an assembly space based on a basic symbol and a string of length

. Subsequently, this string assembly space evolves to reduce the cardinality

of the set of the assembly step vertices until it equals the ASI of this string, that is until

. This assumption is supported by physics. It was shown [

28] by equating the binary entropy variation on a holographic sphere with the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy that a black hole can be thought of as patternless string of length

having the Hamming weight of

active Planck triangles and - in general - containing at least one fractional triangle having an area smaller than the Planck area and therefore too small to carry a single bit of information. It was further shown [

29] that a black hole represents a pure binary quantum state (qubit) in an equal superposition, that is the only quantum state attaining three known bounds for the quantum orthogonalization interval, and generates entropy variation spheres through the solid angle correspondence that can be thought of as strings of length

, wherein

. Finally, it was shown [

20] based on a simple model of binputation that elegant [

30] binary assembling programs (i.e., bitstrings) assemble minimum ASI bitstrings of lengths expressible as a product of Fibonacci numbers (OEIS

A065108), wherein some binary assembling programs of at least four bits can also assemble non-minimum ASI strings or are not elegant. Hence, we assume that the assembly spaces evolve by reconfiguring the network of edges to decrease the ASD of newly assembled strings, possibly finding shorter pathways for these strings, and if only such a decrease would not result in ASI increase (

shown in

Figure 1(d) is the shortest length, where

).

The concepts of assembly space, string assembly space, assembly index and depth, as well as the evolution of assembly spaces are illustrated in

Figure 2. The assembly depth naturally divides the lengths of strings into sections

.

Theorem 8. A string containing the same three doublets has the same ASI as a string containing two pairs of the same doublets, provided that both strings have the same distributions of other repetitions and have the same lengths.

Proof. W.l.o.g., consider the following two strings of the same length

with

and the same distributions of other repetitions (if there are any other repetitions)

Assembling a doublet takes one assembly step. Each appending of a doublet to an assembled string counts as another assembly step. Hence, in a general case (i.e., for strings , containing also other symbols), the string requires six additional assembly steps, the same as the string , which completes the proof. □

Theorem 9. A string containing the same three doublets has the same ASI as a string containing the same two triplets, provided that both strings have the same distributions of other repetitions.

Proof. W.l.o.g. consider the following two strings of the same length

with the same distributions of other repetitions

The assembly of a triplet takes two steps. Hence, in the general case, the string requires four additional assembly steps, the same as the string , which completes the proof. □

Theorem 10. A string containing the same two triplets has the same ASI as a string containing two pairs of the same doublets, provided that both strings have the same distributions of other repetitions and have the same lengths.

Proof. The proof comes from Theorems 8 and 9. □

Theorem 11. A string containing the same two quadruplets of the minimum ASI has the same ASI as a string containing the same three triplets, provided that both strings have the same distributions of other repetitions and have the same lengths.

Proof. W.l.o.g. consider the following two strings of the same length

with the same distributions of other repetitions

The assembly of such a quadruplet takes two steps. Hence, in a general case, the string requires five additional assembly steps, the same as the string , which completes the proof. □

Theorem 12. A string containing the same two quadruplets of the maximum ASI has the same ASI as a string containing a doublet and the same two triplets based on this doublet, provided that both strings have the same distributions of other repetitions.

Proof. W.l.o.g. consider the following two strings of the same length

with the same distributions of other repetitions

The assembly of such a quadruplet takes three steps. Hence, in a general case, the string requires five additional assembly steps, the same as the string , which completes the proof. □

Theorem 13. A string containing the same two doublets and the same two triplets not based on this doublet has the same ASI as a string containing a doublet and the same two triplets based on this doublet, provided that both strings have the same distributions of other repetitions and have the same lengths.

Proof. W.l.o.g. consider the following two strings of the same length

with the same distributions of other repetitions

where

. In a general case, the string

requires seven additional assembly steps, the same as the string

, which completes the proof. □

In general, Theorems 1-13 show that

k copies of a doublet in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

k copies of a triplet in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

k copies of a minimum ASI quadruplet in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

k copies of a maximum ASI quadruplet in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

where, the phrase "at least" is meant to indicate that other repetitions, such as e.g., doublets forming multiple quadruplets, etc. can further decrease the ASI of the string. This observation allows us to state the following theorem.

Theorem 14.

Each copies of an -plet contained in a string decrease its ASI at least by . That is

where R is the total number of repeated -plets.

Proof. W.l.o.g. consider the following string

containing two copies of an

n-plet

. The

n-plet

can be assembled in at least

steps and appended to the assembled string

in one step. Consider that the ASI of the

n-plet

is

, i.e., the

n-plet does not have any repetitions that can be reused. Then one copy of this

n-plet - as expected - does not decrease the ASI of the string

, as

, while more copies

k decrease it by

. On the other hand, if

then even a single copy of this

n-plet will decrease the ASI of

. □

For example, due to the presence of three copies of a 5-plet

, each with

, in a string

its ASI amounts to

. The relation (

25) provides the upper bound on ASI as it does not describe a situation in which

n-plet for

is assembled based on a doublet also present in one copy in the string. For example, the string

, while

. We note that the maximum ASI decrease is provided by

-plets of the minimum ASI and amounts to

.

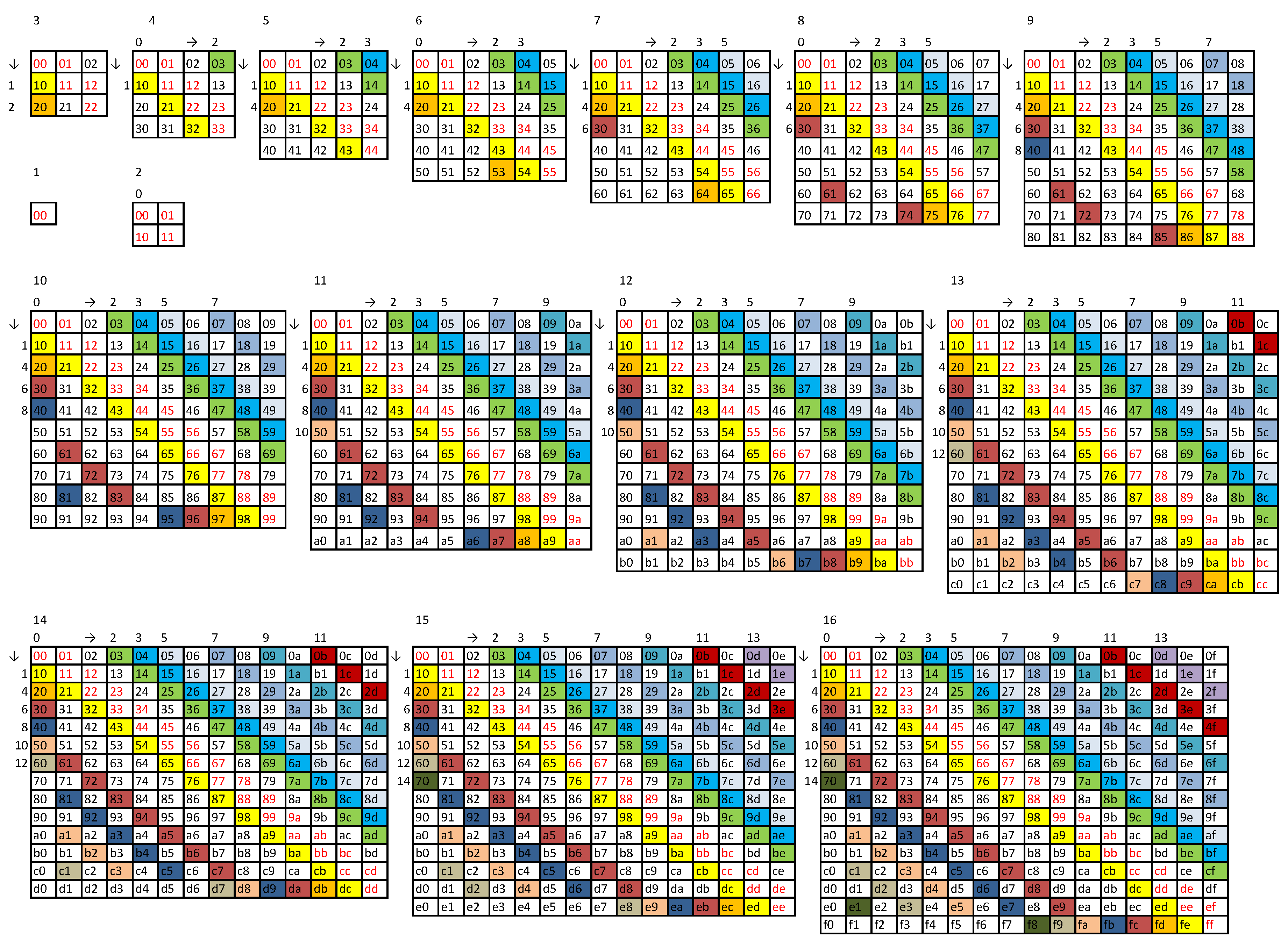

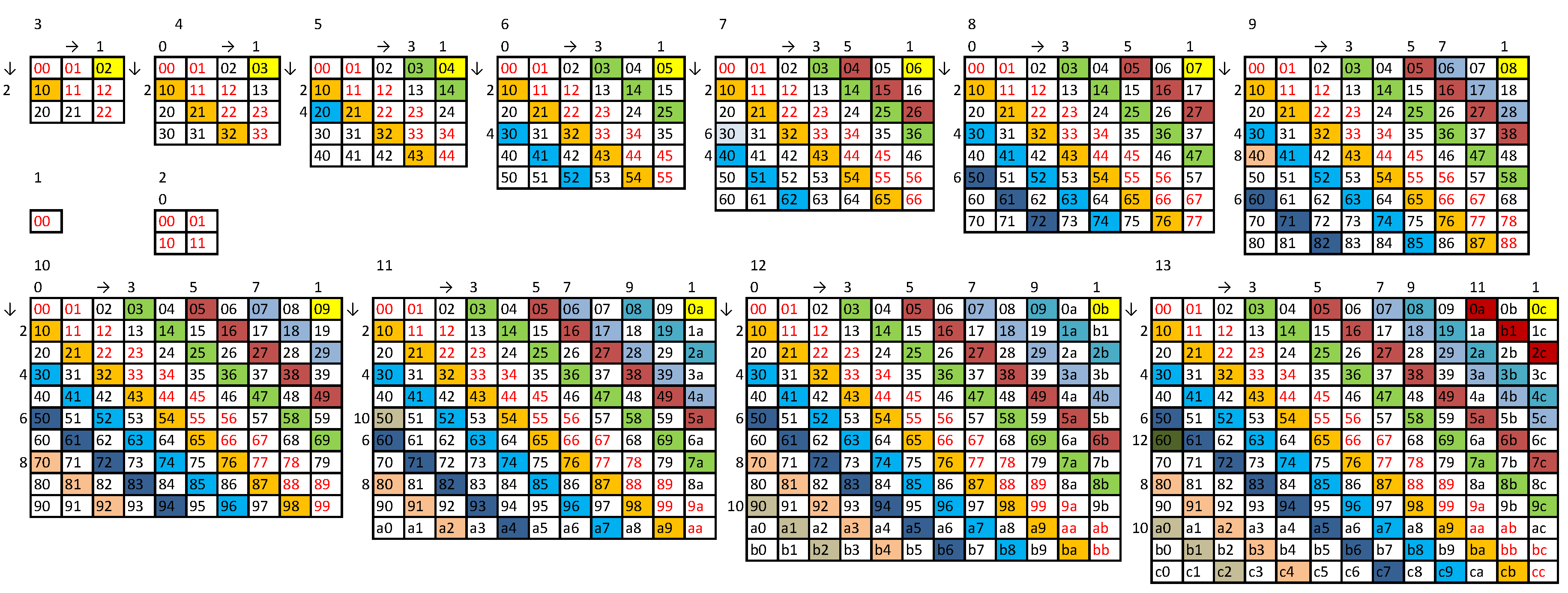

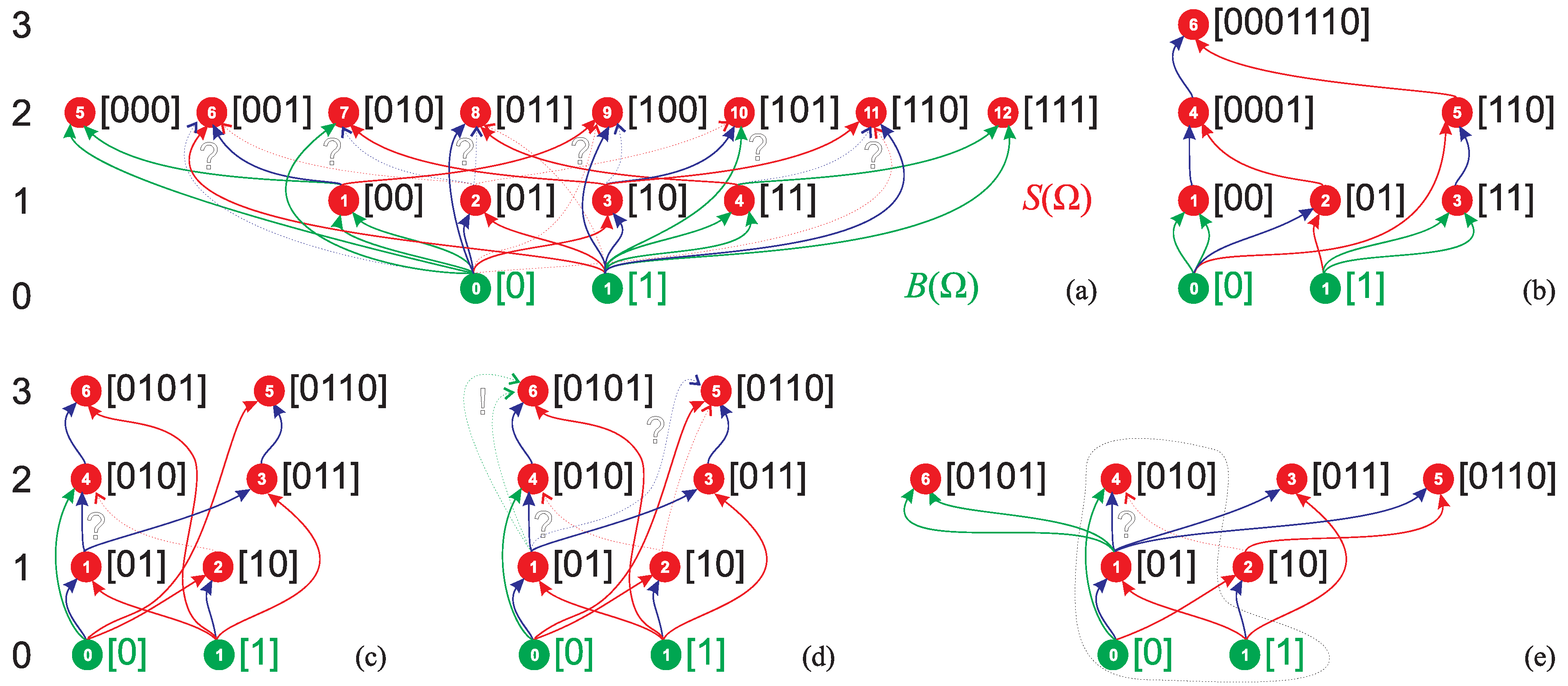

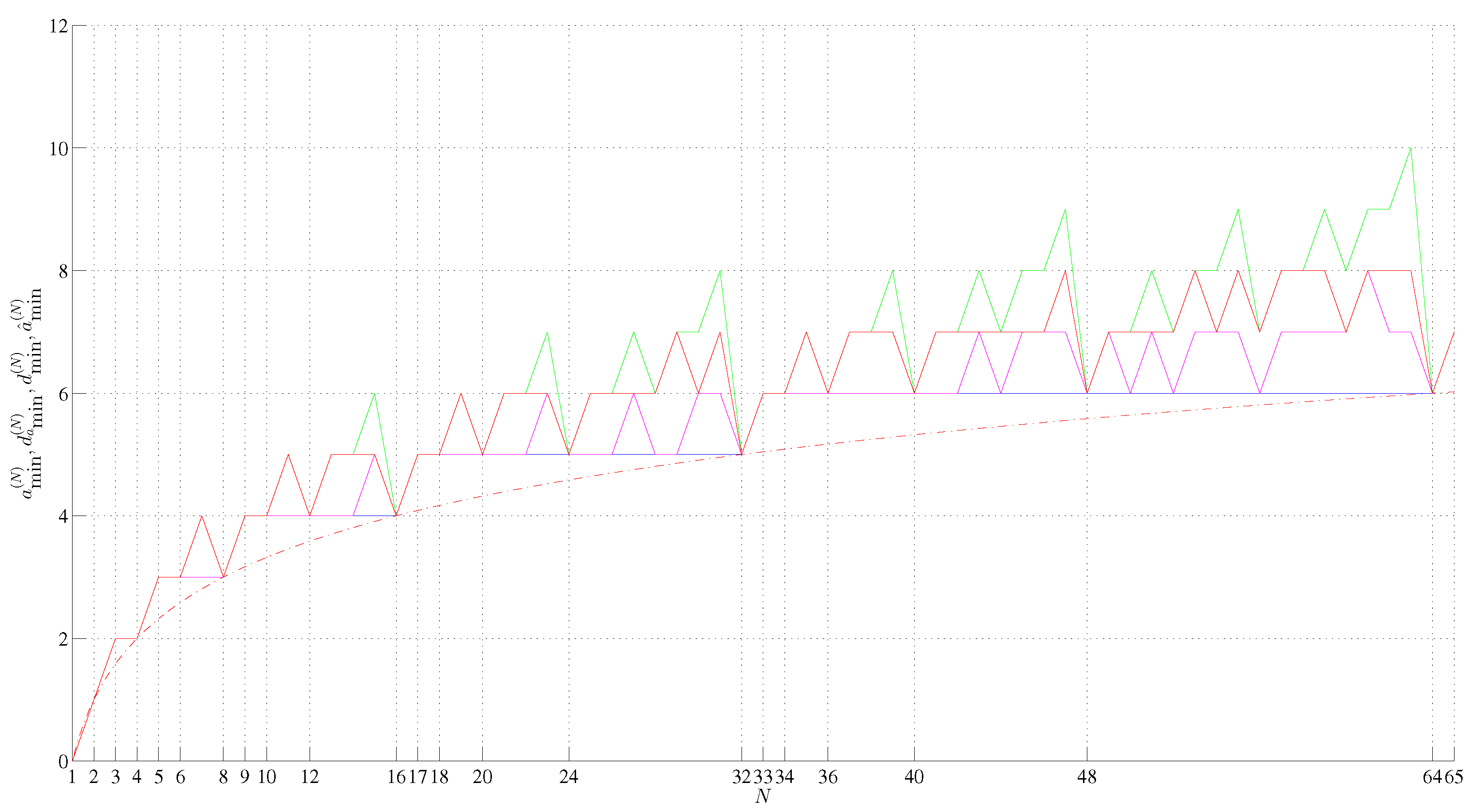

3. Minimum Assembly Depth, Assembly Depth of a Minimum Assembly Index, Minimum Assembly Index, and Depth Index

The minimum ASD as a function of the length of a string

(

9), the ASD of a minimum ASI string

(which we call here the

minimum ASI ASD), the minimum ASI as a function of the length of a string

(OEIS

A003313), and DPI

(OEIS

A014701) define four distinct sets illustrated in

Figure 4, wherein

. We observed certain salient regularities among them.

Theorem 15. The minimum ASD, minimum ASI ASD, minimum ASI, and DPI are equal to if .

Proof. To prove that the minimum ASI ASD equals minimum ASI, we use mathematical induction on the length

N of the string. For the base case (

), the string consists of a single basic symbol

. Hence, its ASI is

and its ASD

. Therefore,

. Assume now that for all strings of length

less than

N, the ASD equals the minimum ASI, that is

For some integer

s, we construct the minimum ASI string as follows. First, we assemble a doublet from two basic symbols:

Its ASI is

and its ASD is

. Then for each

we have

with the ASI

and the ASD

and we construct

by joining two copies of

The ASI of the string

is equal to

and, similarly, its ASD is equal to

Therefore,

. At any step, we assemble strings (

3), and no two assembly steps can be independent, which follows from Theorem 2. The equation (

12) establishes that

is the largest

N for which

. This proves

. Finally, the even part of the definition of the DPI Definition 4 is the only defining part of this definition iff

. Hence,

. □

Theorem 15 can be generalized as follows.

Theorem 16.

The minimum ASD, minimum ASI ASD, minimum ASI, and DPI are equal to iff

Proof. The strings (

33) (OEIS

A173786 or

A048645) are the generalization of the strings of length

of the previous Theorem 15. For other lengths of the strings (

33), the base case for

describes the assembly of a triplet, by joining a symbol to a doublet made in the first step, so that both the ASI and the ASD of this triplet increase by one. And so on. For any

s we can join a symbol to a string of length

assembled in

steps or join two such strings, as shown in

Figure 3(a).

To see that

(

33) holds for

note that there is only one odd part of the definition of the DPI Definition 4 that

restores. For example, we reach one starting from

in five steps through

. □

The assembly spaces of other minimum ASI strings can contain independent assembly steps. The first such case occurs for

, where, for example, the

results in a string having ma

and

, since both

and

were assembled from the doublet

in two independent assembly steps at the same depth

, which is congruent with Theorem 4.

Theorem 17.

The minimum ASI strings [20] (strings (15)) of lengths

have only one independent assembly step in their assembly spaces, and excluding this step, they are assembled by joining the longest string assembled so far with itself. Therefore, their ASI is one greater than the minimum ASD (9).

Proof. We begin at

by assembling a

using a quadruplet and a triplet assembled independently (e.g., using an assembly space (

34)) with

and

. For

, the string (

35)

can be assembled by joining the string

assembled in three steps and the triplet, while the string

by joining two strings

made in the previous step. For any

d, the shortest string (

35)

can be assembled by joining the string

(

3) assembled in

steps and the triplet, while the remaining strings

- by joining two strings made in a previous step

, as shown in

Figure 3(b). □

Theorem 18.

The minimum ASI strings of lengths

have only one independent assembly step in their assembly spaces, and excluding this step, they are assembled by joining the longest string assembled so far with itself. Therefore, their ASI is one greater than the minimum ASD (9).

Proof. We begin at

by assembling a

through

with

. For any

d, the shortest string (

36)

can be assembled by joining the string

(

3) assembled in

steps with the 5-plet assembled in the independent assembly step, while the remaining strings

- by joining two strings made in a previous step

, as shown in

Figure 3(c). □

Theorem 19.

The minimum ASI strings of lengths

have only one independent assembly step in their assembly spaces, and excluding this step, they are assembled by joining the longest string assembled so far with itself. Therefore, their ASI is one greater than the minimum ASD (9).

Proof. We begin at

by assembling a

with

. For any

d, we assemble the shortest strings (

37) as

with one independent assembly step

to assemble the string of length

and joining 9-plet at the last step, while the remaining strings

- by joining two strings made in a previous step

, as shown in

Figure 3(d). □

Theorems 17-19 allow for the following generalization.

Theorem 20.

The minimum ASI strings of lengths

have only one independent assembly step in their assembly spaces, and excluding this step, they are assembled by joining the longest string assembled so far with itself. Therefore, their ASI is one greater than the minimum ASD (9).

Proof. The lengths of the strings (

39) are listed in rows in

Table 1 starting after the length of the substring assembled in an independent assembly step marked green. Hence, the first row contains the lengths of strings of Theorem 17 shown on the diagonal of

Figure 3(b), and so on. □

Theorem 21.

The minimum ASI strings [20] of lengths

are assembled by joining the longest string assembled so far with itself. Their ASI and ASD are the same, one greater than the minimum ASD (9) and one smaller than the DPI.

Proof. The equality of ASI and ASD of the strings (

40) follows from the proof of Theorem 16. Furthermore,

shows that

. Finally,

follows from the DPI Definition 4: six steps are required to reach one starting from fifteen and additional steps for thirty, sixty, etc., which completes the proof. □

Theorem 21 seems to allow for the following generalization, which we have validated numerically based on the OEIS

A003313 sequence for

.

Conjecture 22.

For d, l, and defined by the relation (39), the following holds

The lengths of the strings (

42a) and (

42b) are listed in rows in

Table 1.

Furthermore, we have numerically validated the following conjecture.

Conjecture 23.

The minimum ASI strings of lengths

The shortest strings of length

(

43a) can be assembled with the pathways

shown in

Figure 3(e); the shortest strings of length

(

43b) can be assembled with the pathways

shown in

Figure 3(f); and for any

d, the shortest strings of length

(

43c) can be assembled as

The remaining strings of length , , and (23) can be assembled by joining two strings made in a previous step .

Strings of lengths (

33), (

35), and (

40), revealed in [

20] based on the degree of causation, showed that there are certain regularities among the minimum ASI strings. Here, we extended these results to strings of lengths (

39), (42), and (43).

In general, Theorems 16-21 (in particular Theorem 21) and Conjectures 23 and 22 show a peculiar interdependence among the minimum ASD (

9), minimum ASI ASD, minimum ASI, and DPI, as shown in

Figure 4. In particular, they show that

the of minimum ASI strings having ASI equal to DPI cannot contain strings assembled in independent assembly steps,

the s of other minimum ASI strings can contain at least two such strings, and therefore

the assembly space of a maximum ASI string will tend to maximize the number of strings assembled in independent assembly steps in the , taking into account the saturation of the as it cannot contain more than distinct n-plets, and hence to minimize the possible ASD.

We note that the difference between the DPI and minimum ASI is, in general, larger than one. The assembly spaces of the minimum ASI strings for

are listed in

Table A1.

4. Maximum Assembly Index Strings

The seven-bit string is the longest string that can have the maximum ASI

. There are four such bitstrings containing two clear triplets and the starting bit at the end or the ending bit at the start, that is

and their lengths cannot be increased without a repetition of a doublet, which keeps the ASI at the same level

.

This observation and Theorem 2 motivated us to develop a general method to construct the longest possible string having the maximum ASI , as a function of the radix b. We denote the length of this string by or , and we call this string a string.

After a few groping try-outs, we eventually reached two stable methods (cf. Appendices, Methods

Appendix A and

Appendix B). In both methods, we start with an initial balanced string of length

containing

b clear triplets ordered as

The doublets that can be inserted into the initial string (

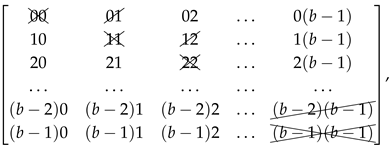

48) can be arranged in a

matrix

where the crossed out entries on a diagonal cannot be reused, as they would form repetitions in this string. Due to the order of triplets in the string (

48) we can also cross out the entries in the first superdiagonal of the matrix (

49). The strings of odd lengths generated by these general methods are not only the longest but also the most balanced. This can be stated in the following theorem.

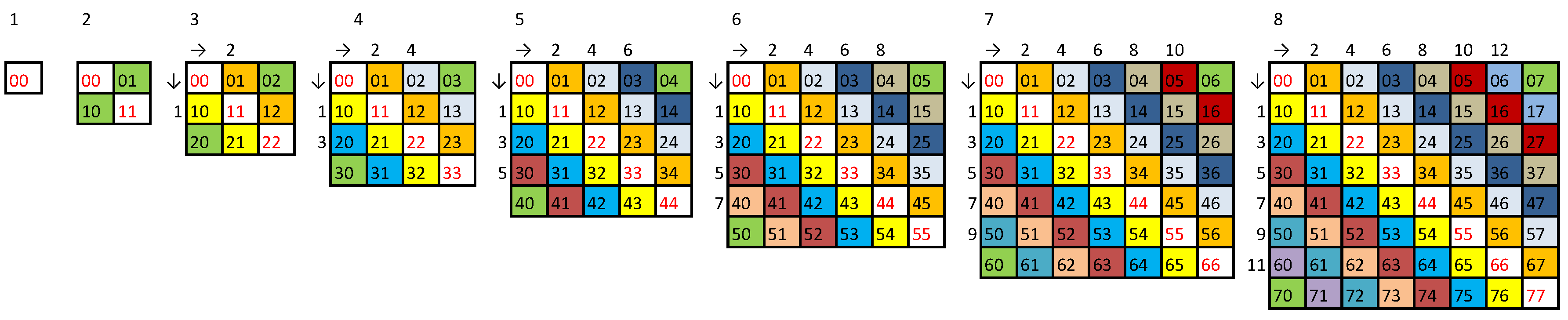

Theorem 24.

The longest length of a string that has the ASI of is given by

(Squarefree numbers, OEIS A353887) and this string is nearly balanced, that is

where is the number of occurrences of all but one symbol within the string, and its Shannon entropy is

The proof of Theorem 24 is given in

Appendix D. A

string must contain all clear triplets and all doublets and if it is generated by Method

Appendix A or

Appendix B it is terminated with 0 and has a form

Although the case for

is degenerate, as no information can be conveyed using only one symbol (

in this case), nothing precludes the assembly of such defunct strings and the formula (

50) yields the correct result; the string

is the longest string with

by Theorem 1, as for

the upper and the lower bound on the ASI are the same,

(OEIS

A003313). This is the only case where the maximum ASI is not a monotonically nondecreasing function of

N.

For

, only two doublets can be introduced without repetitions into the initial string (

48), leading to twelve unique strings of length

Finally, we have to multiply the cardinality of this set by to account for permutations. For example, the first string , is equivalent to five strings , , , , and . Hence, there are seventy-two different strings of length .

Subsequently, we considered other strings of length with the maximum ASI for .

Theorem 25.

For all and the longest length of a string that has the ASI of is given by

The proof of Theorem 25 is given in

Appendix E. This result disproves our upper bound Conjecture 1 for

stated in our previous study [

20]. If the strings of Theorem 25 are based on strings generated by Method

Appendix A or

Appendix B, for

they owe their properties to the following distributions of symbols

For the strings of the form (

56) the fractions in the Shannon entropy are

where

,

if

and

,

otherwise, as

is inserted into

,

into

and

or

otherwise. This leads to Shannon entropy

of any

string having length

, for

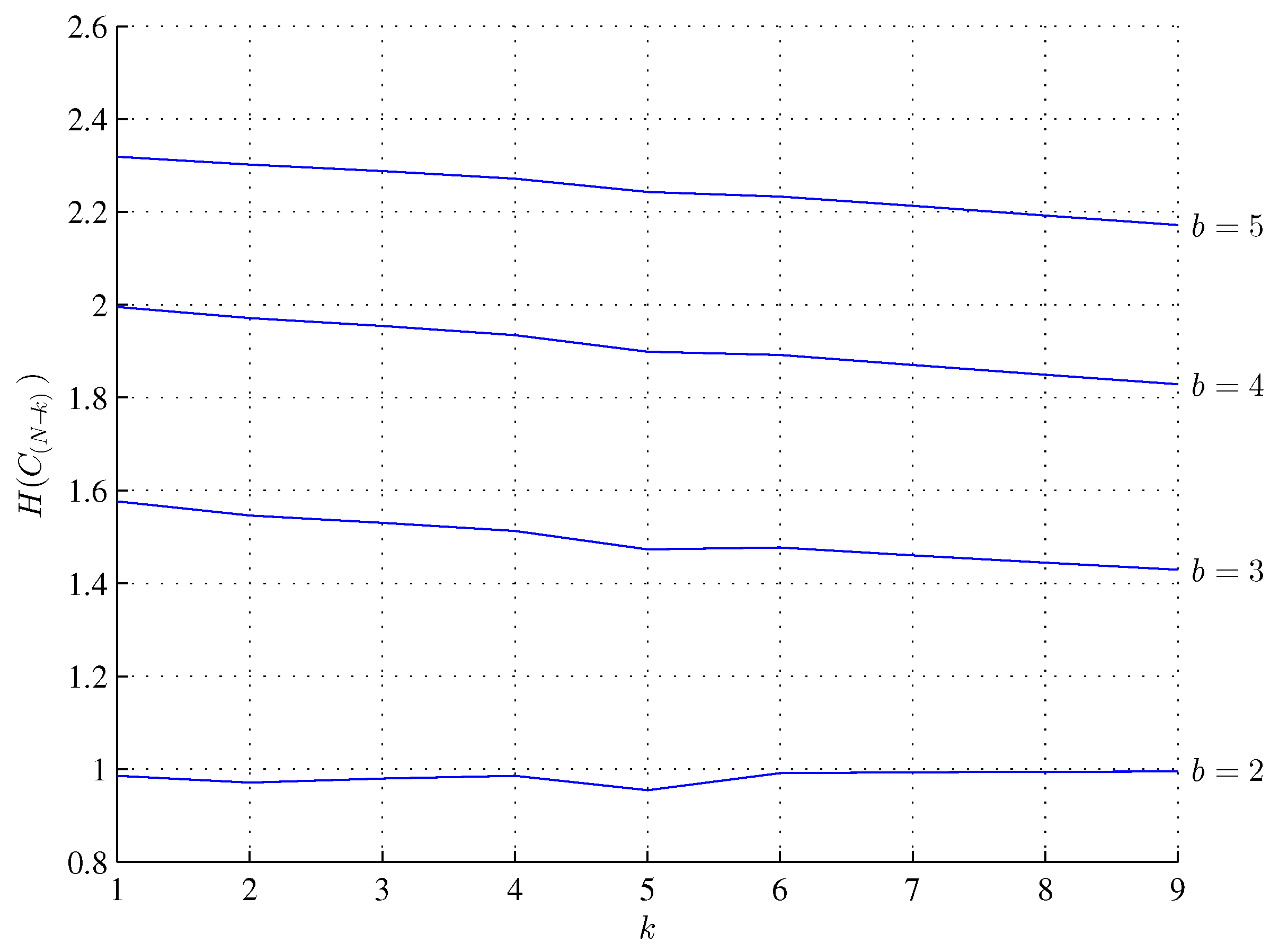

. The entropies (

52) and (

58) are shown in

Figure 5. Radix

is the smallest one at which the entropy (

58) is a monotonically decreasing function of

k. For

there is a local entropy minimum for

and for

an additional local entropy minimum for

. Perhaps, the entropy (

58) has other local entropy minima for

and for

.

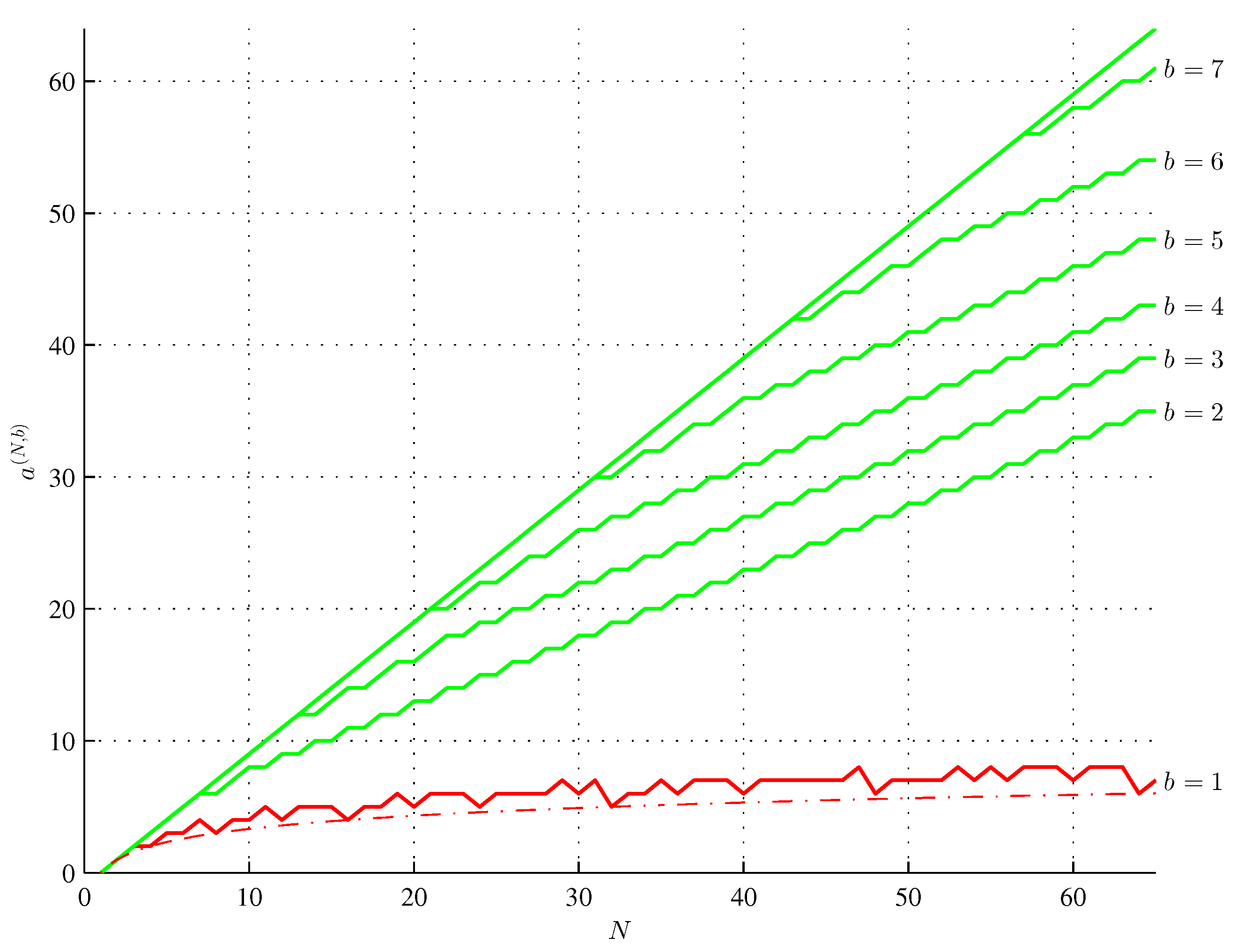

Theorem 26.

If and then

Proof. Formulas (

59) and (

60) capture the stepwise linear relation of Theorem 25, shown in

Figure 6 for all

N. In other words, if

, then ASI increases by one, where

N increases by two (

are triangular numbers, OEIS

A000217). Once

is defined by this relation it can only decrease its slope for

. □

Conjecture 27.

then .

W.l.o.g. Conjecture 27 can be proven (or falsified) for

. We note that inserting any doublet into a

string (

A19) at any position forms a triplet. Using the equation (

25) of Theorem 14 we have

for any step

s if only

. Now, assume that

,

and

,

. Then

The proof of the Conjecture 27 must show the conditions for the equations (

62) and (

63) to hold. We note that the assumption used in the equation (

63) is valid only for

and

. We note that maximum ASI must rise. If it were constant for

, then at some even larger

N it would inevitably become lower than the minimum ASI bound 2 which also rises, and this would be a contradiction. The bounds of Theorems 24 and 25 and Conjecture 26 are illustrated in

Figure 6.

5. A Method of Generating a Maximum Assembly Index String

The results thus far led us to a simple method of determining the ASI of a maximum ASI string and strengthened our Conjectures 3 and 4 stated in the previous study [

20]. The method is based on unique

-plets and powers of two, as shown in

Table 2. First, a maximum ASI string is sequenced, every two symbols to find the number

of unique adjoining doublets

. In particular, a

string (

A3) or (

A4) contain the maximum of

unique adjoining doublets, a

string (

A13) contains the maximum of

unique adjoining doublets, and so on. In general, a

string contains the maximum of

unique adjoining doublets, where

is given by the relations (

50) or (

55), which is independent of

k.

Subsequently, these doublets form unique adjoining quadruplets, quadruplets form unique adjoining octuples, and so on depending on the length of the string N and the radix b, as there can be at most unique -plets. The columns "last " indicate if the assembled string should be terminated with a single substring of length in descending order. The empty fields in the respective columns for indicate that a given substring can be interpreted as either a "regular" single substring or a last substring if . Furthermore, each step and all last steps are tantamount to one ASD level.

For example, the

string (

A20) of length

for

can be assembled as

Similarly, the

string (

A3) of length

for

can be assembled, as shown in

Table 2 as

Furthermore, for

the method produces the DPI (OEIS

A014701). For example, the string of length

can be assembled in six steps as

where obviously

. However, this is the 1

st exception for

as the ASI of this string is five if it is assembled using doublet

and triplet

.

We further note that the method illustrated in

Table 2 cannot be used to construct the maximum ASI string. For example, both the following two distributions of doublets for

satisfy the distributions of

Table 2. However, only the left one correctly reflects the maximum ASI of the assembled string.

as the right one can be assembled in four steps with

. Similarly, only the top distribution of doublets below correctly reflects the maximum ASI of the assembled string for

as the bottom one can be assembled in six steps with

. Furthermore, this method tends to exaggerate the estimated maximum ASI value, that is,

where

is the ASI of a string

determined by the method illustrated in

Table 2. For example, the first six strings below contain four unique doublets instead of the required three. Therefore

Further research should consider researching the formula equivalent to (

50) that captures a quadruplet repetition, similarly as

captures a doublet repetition.

6. Discussion

The mathematical findings of this study, especially the theorems concerning the ASI, DPI, and ASD, provide a framework for understanding the principles underlying the assembly of biological macromolecules such as DNA and proteins. These theorems offer insights into how the complexity and functionality of biological sequences are governed by underlying mathematical principles. For instance, here we demonstrate that a DNA strand of length N containing four nucleobases cannot represent a minimum ASI string without violating Chargaff’s rules and Theorem 3, which establishes that a minimum ASI string can contain at most two distinct symbols if and at most three, otherwise.

The fundamental interplay of entropy, energy, and temperature is inherent in thermodynamics. Although increasing entropy is a natural tendency of thermodynamic systems following the second law of thermodynamics, dissipative structures, including biological ones, which are open, can decrease their internal entropy by increasing the entropy of their surroundings. By evolving sequences with lower entropies, organisms may achieve more stable and energetically favorable configurations. Despite the mathematical ideal of maximum entropy in balanced strings, biological systems often deviate from this balance. This is evident in natural sequences, where certain nucleotides or amino acids are more prevalent, resulting in lower entropy. For example, the Shannon entropy of the SARS-CoV genome containing N = 29903 nucleobases decreased from

to

within two years after the Wuhan outbreak [

20,

31], (

). If the length of a DNA strand is constant, it will tend to evolve to decrease the Shannon entropy [

7,

31] and, hence, to become less balanced. Here we show that any maximum length string without substring repetitions, that is a maximum ASI string with

, is inherently the most balanced: all but one symbol occur

times and one symbol occurs

times within such string

. However, longer maximum ASI strings

become less balanced and, hence, their entropies (

58) decrease. Notably, radix

is the smallest one at which the entropy (

58) is a monotonically decreasing function of

k. Together with Theorem 3 this could be the reason why nature has chosen four nucleobases to encode genetic information. The tendency of biological sequences to become less balanced and thus exhibit lower entropy may reflect an underlying drive toward minimizing the energy required for their assembly and maintenance. This evolution toward energetically favorable states supports the principle that natural systems evolve in ways that reduce free energy, aligning with fundamental thermodynamic and biological principles. More complex sequences require more assembly steps and, consequently, more energy. This energy consideration can influence evolutionary processes, as organisms that synthesize essential proteins and nucleic acids more efficiently may have a selective advantage. Metabolic efficiency is critical for survival, especially in environments where resources are limited, so there is evolutionary pressure to minimize the energy costs associated with macromolecule assembly. Understanding these relationships enhances our comprehension of molecular evolution and the factors that influence the complexity of biological macromolecules.

Analogously, in theoretical physics, black holes - objects of maximal entropy - also consolidate all available energy, suggesting that systems may reach energy minima through configurations that balance entropy and energy. The energy of a black hole conceptualized as a balanced bitstring [

28], can be two times the energy of the entropy variation sphere that it generates [

29], indicating that a tendency toward imbalance seems to be associated with the minimum energy condition.

In summary, our theorems provide a mathematical underpinning biological phenomena such as the preference for radix

in genetic encoding and the evolutionary trend toward lower entropy. Integrating AT into biological contexts opens avenues for a fundamental mathematical understanding of evolutionary processes, responding to the call for a precise and abstract mathematical theory of evolution [

32].