Submitted:

27 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. General Framework

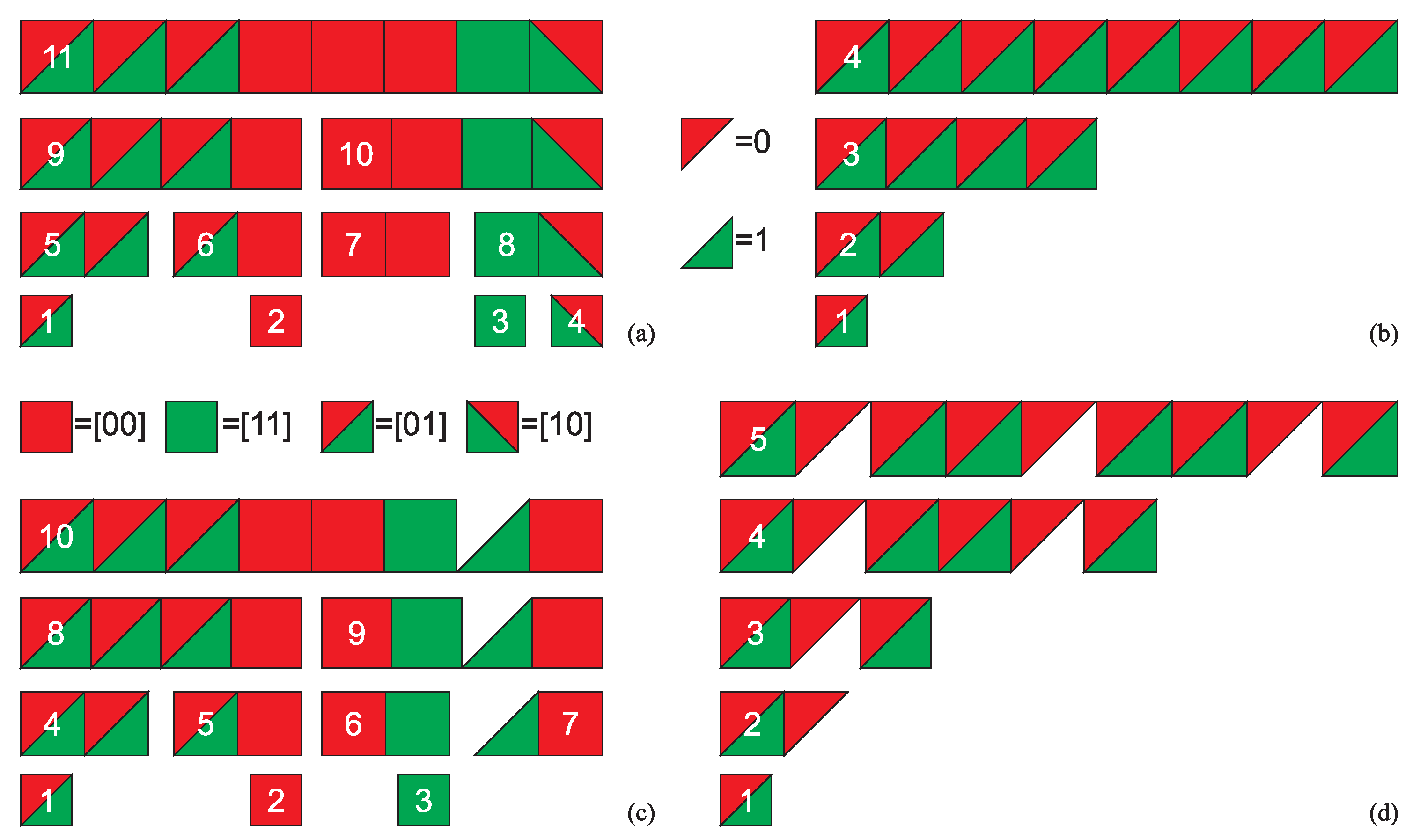

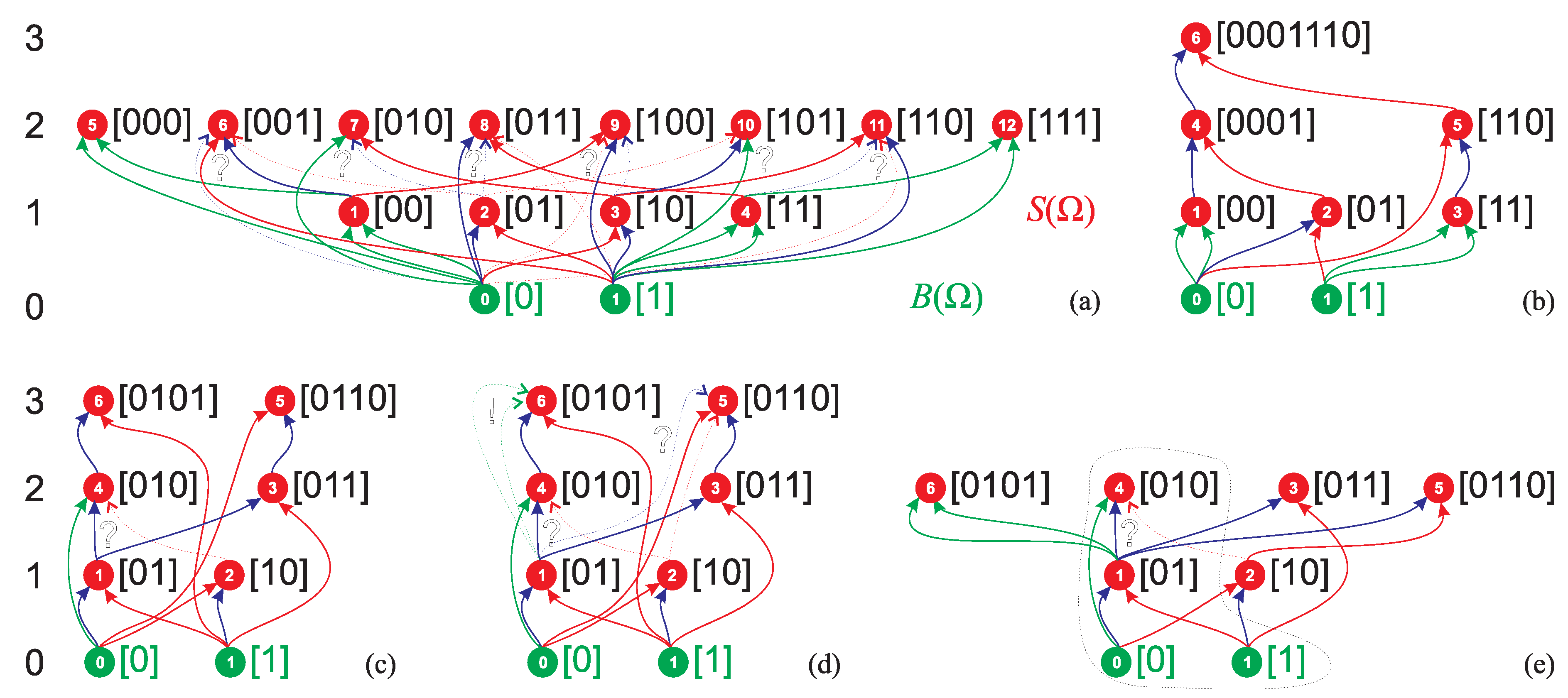

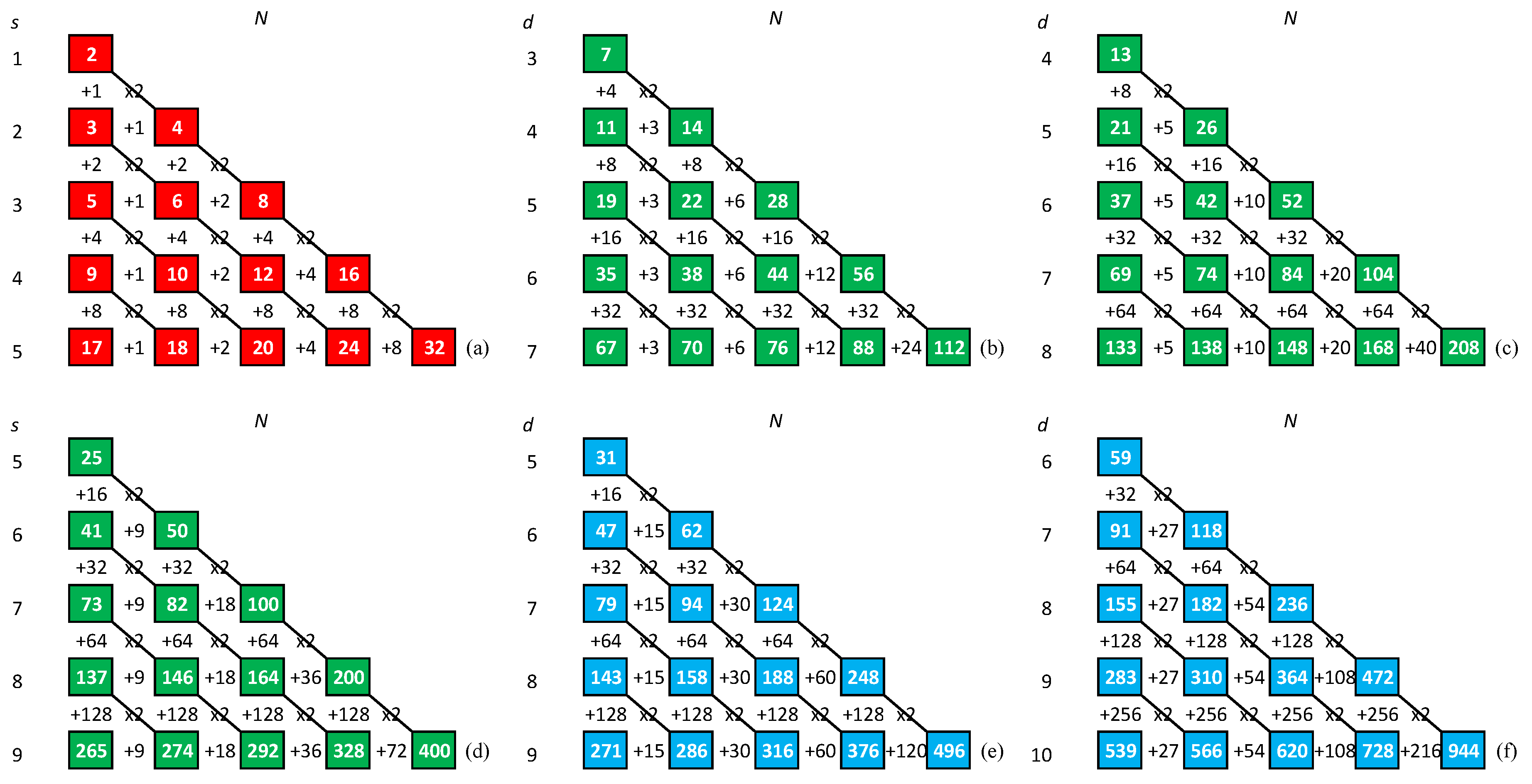

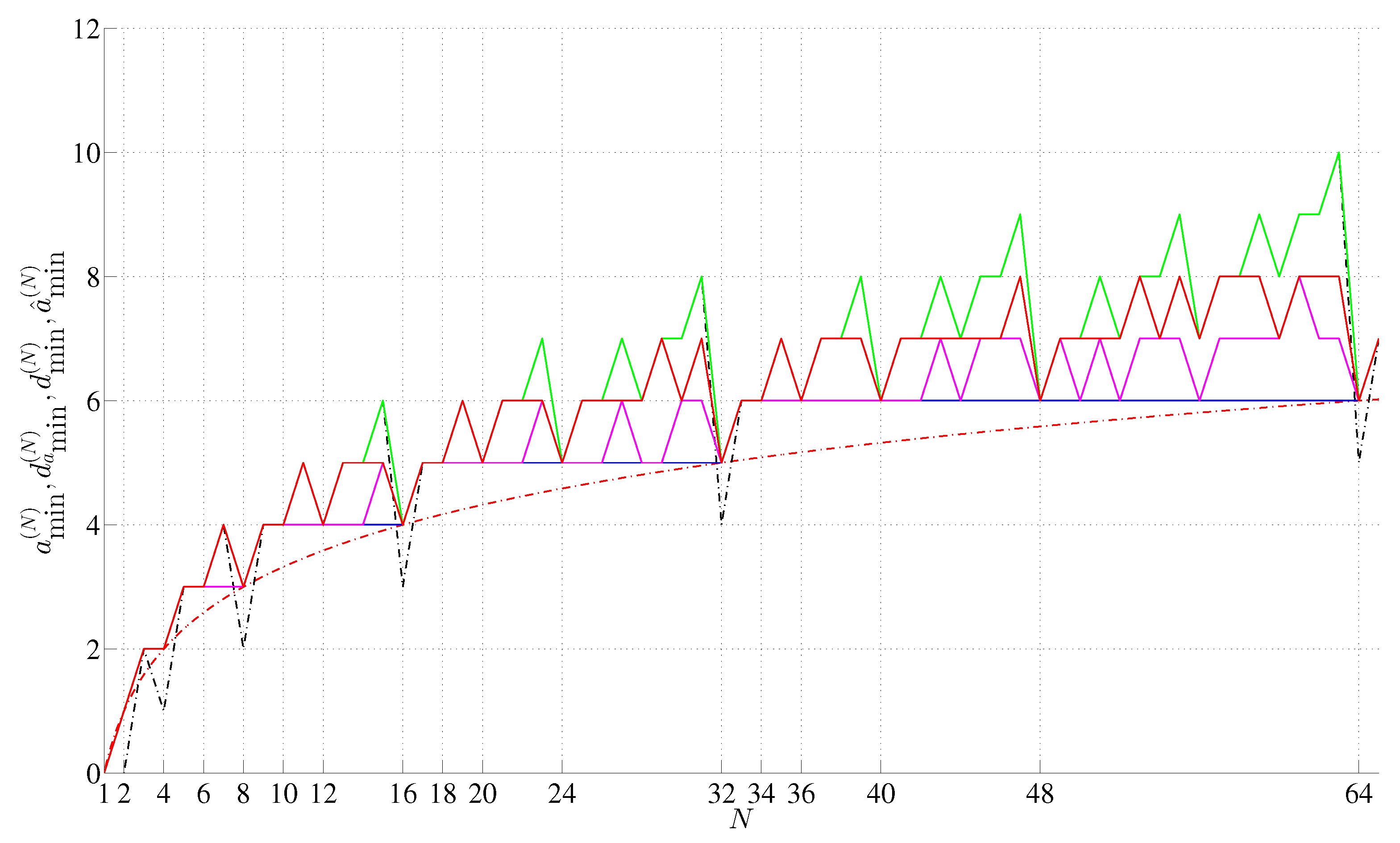

3. Minimum Complexity Strings of AT

- the of minASI strings having ASI equal to DPI cannot contain strings assembled in independent assembly steps,

- the s of other minASI strings can contain at least two such strings, and therefore

- the assembly space of a maxASI string will tend to maximize the number of strings assembled in independent assembly steps in the , taking into account the saturation of the as it cannot contain more than distinct n-grams, and hence to minimize the possible ASD.

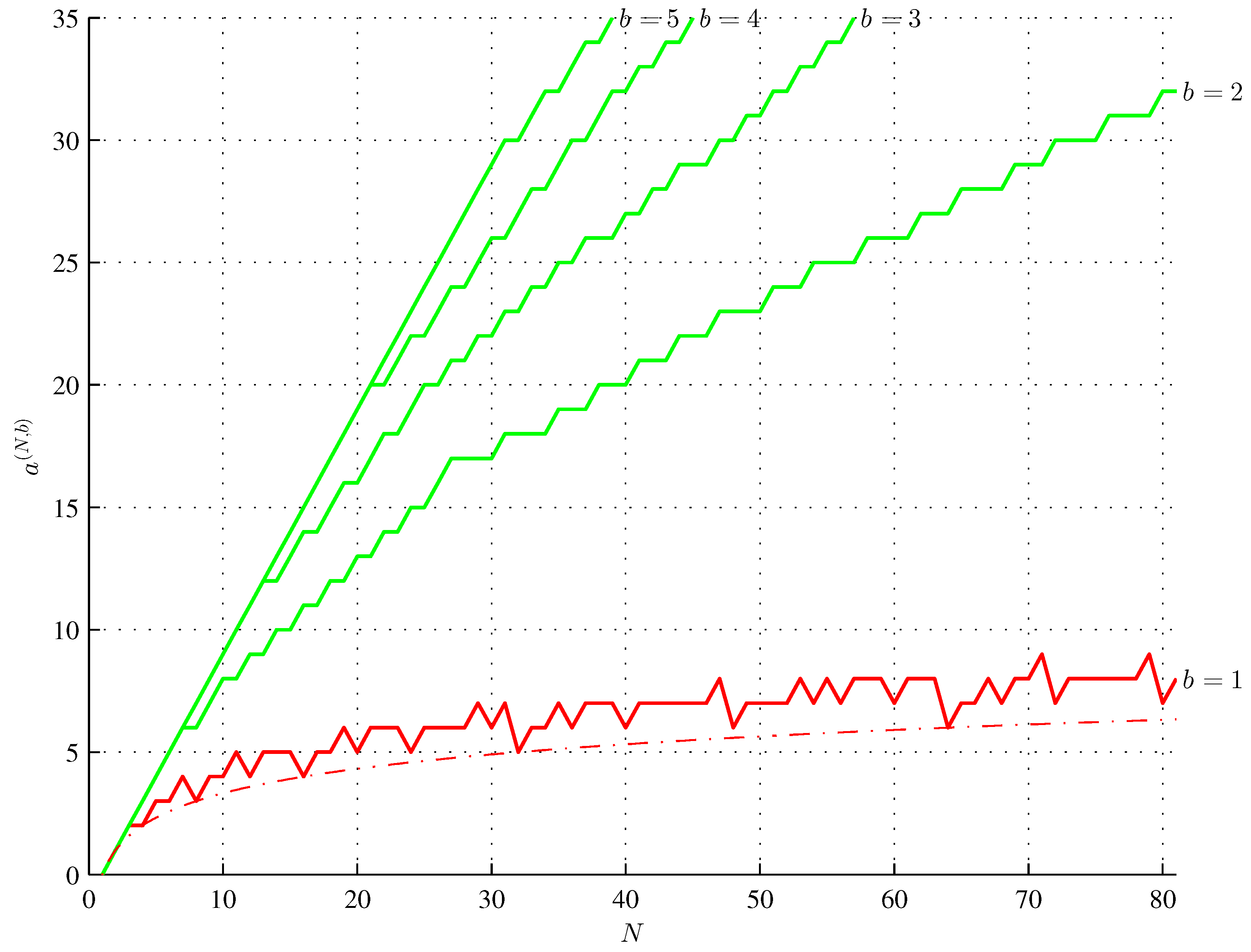

4. Maximum Assembly Index Strings of AT

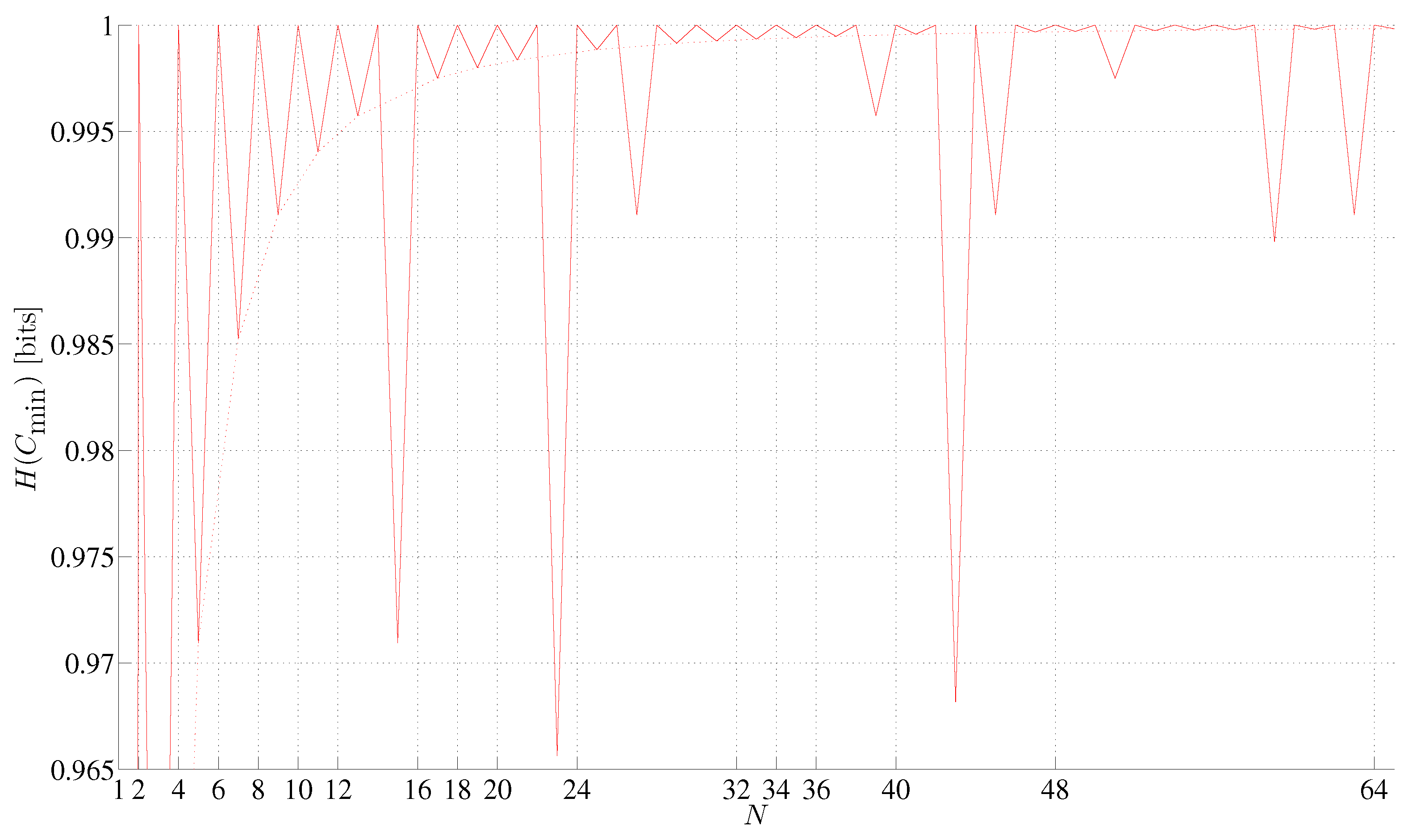

5. Results Common to the Minimum and Maximum Complexity Strings

6. Supremacy of the ASI Compression over Polynomial-Time Compression Algorithms

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AT | assembly theory; |

| N | length of a string; |

| b | number of basic symbols ; |

| , | a string; |

| ASI, | assembly index of a string (minASI - minimum, maxASI - maximum); |

| assembly space of a string ; | |

| ASD, | assembly depth of a string (minASD - minimum, minASI ASD - the ASD of a minASI string); |

| DPI | depth index (OEIS A014701); |

| EWT, | expected waiting time; |

OEIS Sequences

| A003313 | Length of shortest addition chain for n (minASI); |

| A014701 | Number of multiplications to compute n-th power by the Chandah-sutra method (DPI); |

| A026644 | Number of moves to solve Chinese rings puzzle; |

| A048645 | Integers with one or two 1-bits in their binary expansion; |

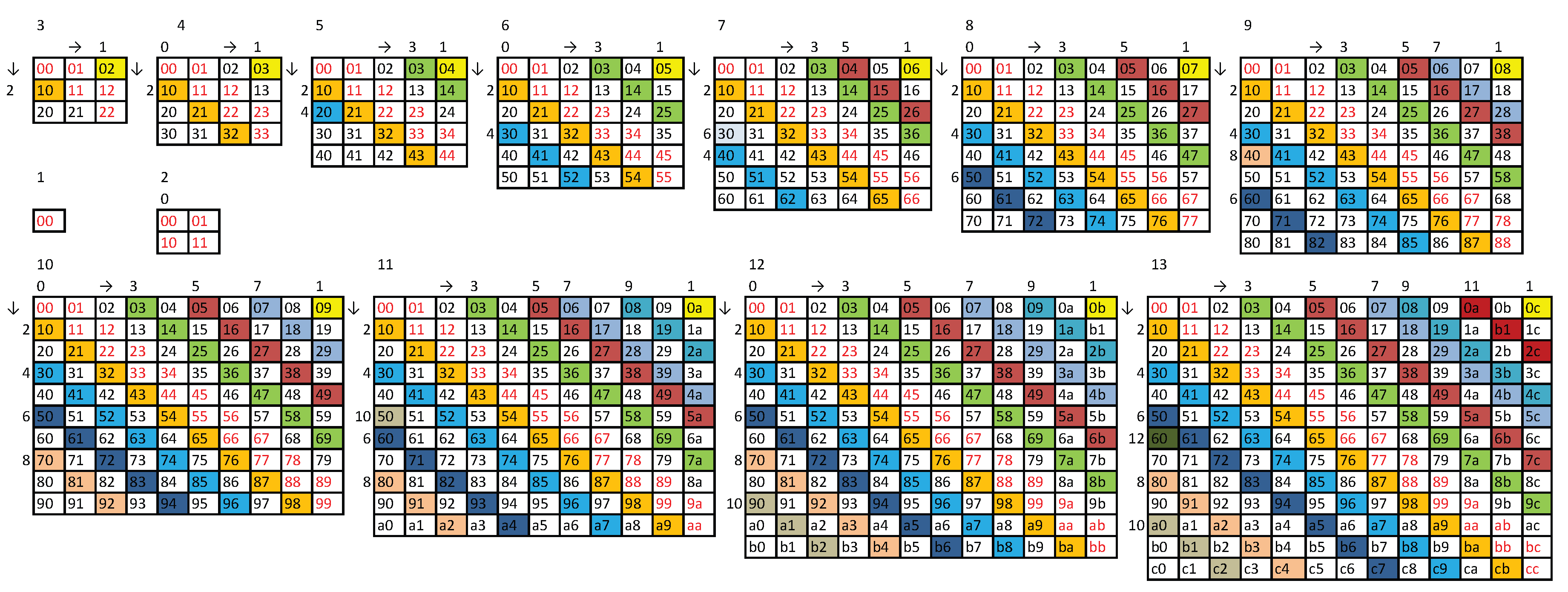

| A173786 | Triangle read by rows: , . |

Appendix A

| s | ... | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 14 | 28 | 56 | 112 | 224 | ... | |

| 15 | 30 | 60 | 120 | 240 | 480 | ||||||

| 23 | 46 | 92 | 184 | 368 | |||||||

| 3 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 11 | 22 | 44 | 88 | 176 | ... | |

| 27 | 54 | 108 | 216 | 432 | |||||||

| 43 | 86 | 172 | 344 | ||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 13 | 26 | 52 | 104 | 208 | ... | ||

| 45 | 90 | 180 | 360 | ... | |||||||

| 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 3 | 19 | 38 | 76 | 152 | ... | |

| 51 | 102 | 204 | 408 | ||||||||

| 83 | 166 | 332 | |||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 5 | 21 | 42 | 84 | 168 | ... | ||

| 85 | 170 | 340 | ... | ||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 9 | 25 | 50 | 100 | 200 | ... | ||

| 5 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 3 | 35 | 70 | 140 | ... | |

| 99 | 198 | 396 | |||||||||

| 163 | 326 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 5 | 37 | 74 | 148 | ... | ||

| 165 | 330 | ... | |||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 9 | 41 | 82 | 164 | ... | ||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 17 | 49 | 98 | 196 | ... | ||

| 6 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 3 | 67 | 134 | ... | |

| 195 | 390 | ||||||||||

| 323 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 5 | 69 | 138 | 276 | ||

| 325 | 650 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 9 | 73 | 146 | ... | ||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 17 | 81 | 162 | ... | ||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 33 | 97 | 194 | ... | ||

| 7 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 3 | 131 | ... | |

| 387 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 5 | 133 | 266 | ||

| 645 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 9 | 137 | ... | ||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 17 | 145 | ... | ||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 33 | 161 | ... | ||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 65 | 193 | ... |

| N | MIA pathway | MBL pathway (Hamming weight ) | String | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | (1) | ||

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | (1) | ||

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | (2) | ||

| 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | (2) | ||

| 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | (3) | ||

| 7 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | (3) | ||

| 8 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | (4) | ||

| 9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | (4) | ||

| 10 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | (5) | ||

| 11 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | (5) | ||

| 12 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | (6) | ||

| 13 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | (6) | ||

| 14 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | (7) | ||

| 15 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | (6) | ||

| 16 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | (8) | ||

| 17 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | (8) | ||

| 18 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | (9) | ||

| 19 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (9) | ||

| 20 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | (10) | ||

| 21 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (10) | ||

| 22 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (11) | ||

| 23 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | (9) | ||

| 24 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | (12) | ||

| 25 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (12) | ||

| 26 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (13) | ||

| 27 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | (12) | ||

| 28 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | (14) | ||

| 29 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (14) | ||

| 30 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | (15) | ||

| 31 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | (15) | ||

| 32 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | (16) | ||

| 33 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | (16) | ||

| 34 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | (17) | ||

| 35 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (17) | ||

| 36 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | (18) | ||

| 37 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (18) | ||

| 38 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (19) | ||

| 39 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| 40 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||

| 41 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | |||

| 42 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | |||

| 43 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | (17) | ||

| 44 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (22) | ||

| 45 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | (20) | ||

| 46 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | (23) | ||

| 47 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | (23) | ||

| 48 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | (24) | ||

| 49 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | (24) | ||

| 50 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (25) | ||

| 51 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | (24) | ||

| 52 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (26) | ||

| 53 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | (26) | ||

| 54 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | (27) | ||

| 55 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | (27) | ||

| 56 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | (28) | ||

| 57 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | (28) | ||

| 58 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | (29) | ||

| 59 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | (26) | ||

| 60 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | (30) | ||

| 61 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 9 | (30) | ||

| 62 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | (31) | ||

| 63 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | (28) | ||

| 64 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | (32) | ||

| 65 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | (32) | ||

| N | N | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | [1010000111] | 8 | 25 | [0000000101010110011111110] | 15 |

| 11 | [00010111100] | 8 | 26 | [01001100000111111101010110] | 16 |

| 12 | [101010000111] | 9 | 27 | [000000011111110101011001000] | 16 |

| 13 | [1000001110101] | 9 | 28 | [0110101011111110000000110010] | 17 |

| 14 | [10011000010111] | 10 | 29 | [01100000001010100111011111110] | 17 |

| 15 | [000001010111110] | 10 | 30 | [100100000000110010101101111111] | 17 |

| 16 | [1001100001010111] | 11 | 31 | [0101010010000000111111101101100] | 18 |

| 17 | [00000010101111110] | 11 | 32 | [01001100000000101011011111111001] | 18 |

| 18 | [100110100001010111] | 12 | 33 | [100000000010011111111011101101010] | 18 |

| 19 | [0111110110000010100] | 12 | 34 | [1000000000100111111110111011010101] | 18 |

| 20 | [10011010000101011111] | 13 | 35 | [10101000000010110010011111110001101] | 19 |

| 21 | [000000010101100111110] | 13 | 36 | [101010000000101100100111111100011101] | 19 |

| 22 | [0010111111101001100000] | 14 | 37 | [1011010101000000010010001111111001101] | 19 |

| 23 | [00000001010101100111110] | 14 | 38 | [10111010101000000010010001111111001101] | 20 |

| 24 | [011001111111010100000001] | 15 | 39 | [111001100100011010000001010101101101111] | 20 |

| N | ||

|---|---|---|

| 40 | [0011001011111110101000000011011000101101] | 20 |

| 41 | [00000111111001110101001011011011000100110] | 21 |

| 42 | [001101111110101010110000000111100100100101] | 21 |

| 43 | [0111100111110110010100000011100011000101101] | 21 |

| 44 | [11101010101011111100100100011000000010110110] | 22 |

| 45 | [111010101010111111001001000110000000111011010] | 22 |

| 46 | [0111100111111010001110000000110010010101001101] | 22 |

| 47 | [01111001111110100011100000001100100101010110110] | 23 |

| 48 | [011110011111101000111000000011001001010101101100] | 23 |

| 49 | [0111100111111010001110000000110010010101011011000] | 23 |

| 50 | [10100111111100010001111010000001011011000011100110] | 23 |

| 51 | [101001111111000100011110100000010110110010011010101] | 24 |

| 52 | [1010011111110001000111101000000101101100100100110101] | 24 |

| 53 | [10100111111100010001111010000001011011001001001101010] | 24 |

| 54 | [101001111111000100011110100000010110110010010011010101] | 25 |

| 55 | [1010011111110001000111101000000101101100100100110101010] | 25 |

| 56 | [10100111111100010001111010000001011011001001001101010101] | 25 |

| 57 | [101001111111000100011110100000010110110010010011010101010] | 25 |

| 58 | [1010011111110001000111101000000101101100100100110101010101] | 26 |

| 59 | [10001011100111001111111011010000001110000011001001001010101] | 26 |

| 60 | [101010111011110011111110100100001100100010001001010110000000] | 26 |

| 61 | [1010101110111100111111101001000011001000100010010101100000001] | 26 |

| 62 | [10101011101111001111111010010000110010001000100101011011000001] | 27 |

| 63 | [101010111011110011111110100100001100100010001001010110110000000] | 27 |

| 64 | [1010101110111100111111101001000011001000100010010101101100000001] | 27 |

| 65 | [10101011101111001111111010010000110010001000100101011011011000001] | 28 |

| 66 | [101010101011001000111110110111110001000000110011001110011010010010] | 28 |

| 67 | [1010101010110010001111101101111100010000001100110011100110100100101] | 28 |

| 68 | [10101010101100100011111011011111000100000011001100111001110001011110] | 28 |

| 69 | [101010101011001000111110110111110001000000110011001110011100010100101] | 29 |

| 70 | [1010101010110010001111101101111100010000001100110011100111000101001001] | 29 |

| 71 | [10101010101100100011111011011111000100000011001100111001110001010010010] | 29 |

| 72 | [101010101011001000111110110111110001000000110011001110011100010100100101] | 30 |

| 73 | [1010101010110010001111101101111100010000001100110011100111000101001001001] | 30 |

| 74 | [10101010101100100011111011011111000100000011001100111001110001010010000001] | 30 |

| 75 | [101010101011001000111110110111110001000000110011001110011100010100100000001] | 30 |

| 76 | [1010101010110010001111101101111100010000001100110011100111000101001000010000] | 31 |

| 77 | [10101010101100100011111011011111000100000011001100111001110001010010000000000] | 31 |

| 78 | [101010101011001000111110110111110001000000110011001110011100010100100000000001] | 31 |

| 79 | [1001011101101011111110100110110010011101010110100101000110011110111100000001011] | 31 |

| 80 | [10010111011010111111101001101100100111010101101001010001100111101111000000010101] | 32 |

| 81 | [100101110110101111111010011011001001110101011010010100011001111011110000000101010] | 32 |

| 82 | [1001011101101011111110100110110010011101010110100101000110011110111100000001010100] | 32 |

| 83 | [10010111011010111111101001101100100111010101101001010001100111101111000000010101000] | 33 |

| 84 | [100101110110101111111010011011001001110101011010010100011001111011110000000101011100] | 33 |

| 85 | [1001011101101011111110100110110010011101010110100101000110011110111100000001010111000] | 33 |

| N | ||

|---|---|---|

| 13 | [0002220111210] | 12 |

| 14 | [00022201112101] | 12 |

| 15 | [000222011121012] | 13 |

| 16 | [0002220111210120] | 14 |

| 17 | [20011121002201021] | 14 |

| 18 | [222111210100001202] | 15 |

| 19 | [0221110100122200021] | 16 |

| 20 | [02211101001222000211] | 16 |

| 21 | [022111010012220002112] | 17 |

| 22 | [0221110100122200002021] | 18 |

| 23 | [02211101001222000211201] | 18 |

| 24 | [022111010012220002011210] | 19 |

| 25 | [0222212112002010001111021] | 20 |

| 26 | [02222121120020100011110210] | 20 |

| 27 | [012221211200201000111102202] | 21 |

| 28 | [0122212112002010001111022010] | 21 |

| 29 | [01222121120020100011110220210] | 22 |

| 30 | [012221211200201000111102202102] | 22 |

| 31 | [0122212112002010001111022021020] | 23 |

| 32 | [01222121120020100011110220210200] | 23 |

| 33 | [012221211200201000111102202102000] | 24 |

| 34 | [0122212112002010001111022021020001] | 24 |

| 35 | [01222121120020100011110220210200000] | 25 |

| 36 | [012221211200201000111102202102000001] | 25 |

| 37 | [0122212112002010001111022021020010101] | 26 |

| 38 | [01222121120020100011110220210200101101] | 26 |

| 39 | [012221211200201000111102202102001011012] | 26 |

| 40 | [0122212112002010001111022021020010110000] | 27 |

| 41 | [01222121120020100011110220210200101100002] | 27 |

| 42 | [012221211200201000111102202102001011000022] | 28 |

| 43 | [0122212112002010001111022021020010110000222] | 28 |

| 44 | [01222121120020100011110220210200101100000110] | 29 |

| 45 | [012221211200201000111102202102001011000001110] | 29 |

| 46 | [2111020110222211012201112212121010020000001202] | 29 |

| 47 | [21110201102222110122011122121210100200000010220] | 30 |

| 48 | [211102011022221101220111221212101002000000120210] | 30 |

| 49 | [2111020110222211012201112212121010020000001202112] | 31 |

| 50 | [21110201102222110122011122121210100200000012021120] | 31 |

| 51 | [211102011022221101220111221212101002000000120212210] | 32 |

| 52 | [2111020110222211012201112212121010020000001202122120] | 32 |

| 53 | [21110201102222110122011122121210100200000012021200220] | 33 |

| 54 | [211102011022221101220111221212101002000000120212002202] | 33 |

| N | ||

|---|---|---|

| 21 | [000111222333102132030] | 20 |

| 22 | [0001112223331021320302] | 20 |

| 23 | [00011122233310213203012] | 21 |

| 24 | [010000111222333102132030] | 22 |

| 25 | [0100001112223331021320302] | 22 |

| 26 | [01000011122233310213203023] | 23 |

| 27 | [010000111222333102132030221] | 24 |

| 28 | [0001102013331121301222230323] | 24 |

| 29 | [00011320133311121022232302030] | 25 |

| 30 | [301000012111123222233310320213] | 26 |

| 31 | [3010000121111232222333103202130] | 26 |

| 32 | [30100001211112322223331032021303] | 27 |

| 33 | [301000012111123222233310320213313] | 28 |

| 34 | [3010000121111232222333203102133130] | 28 |

| 35 | [30100001211112322223332031021331300] | 29 |

| 36 | [301000012111123222233320310213313110] | 30 |

| 37 | [3010000121111232222333203102133131101] | 30 |

| 38 | [30100001211112322223332031021331311011] | 31 |

| 39 | [301000012111123222233320310213313110221] | 32 |

| 40 | [3010000121111232222333203102133131102210] | 32 |

| 41 | [30100001211112322223332031021331311022101] | 33 |

| 42 | [301000012111123222233320310213313110322011] | 33 |

| 43 | [3010000121111232222333203102133131102210103] | 34 |

| 44 | [30100001211112322223332031021331311022101030] | 34 |

| 45 | [301000012111123222233320310213313110221201300] | 35 |

| 46 | [3010000121111232222333203102133131102212013002] | 36 |

| 47 | [30100001211112322223332031021331311022120130023] | 36 |

| 48 | [301000012111123222233320310213313110221201300230] | 37 |

| 49 | [3010000121111232222333203102133131102212013002303] | 38 |

Appendix A.1. Proof of Theorem 2.1

- k copies of a 2-gram in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

- k copies of a 3-gram in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

- k copies of a minASI 4-gram in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

- k copies of a maxASI 4-gram in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

Appendix A.2. Proof of Theorem 2.2

Appendix A.3. Proof of Lemma 2.2

Appendix A.4. Proof of Theorem 2.3

Appendix A.5. Proof of Theorem 2.4

Appendix A.6. Proof of Theorem 3.1

Appendix A.7. Proof of Theorem 3.3

Appendix A.8. Proof of Theorem 3.4

Appendix A.9. Proof of Lemma 3.1

Appendix A.10. Proof of Lemma 3.2

Appendix A.11. Proof of Lemma 3.3

Appendix A.12. Proof of Theorem 3.6

Appendix A.13. Support for Conjecture Section 3

Appendix A.14. Proof of Lemma 3.4

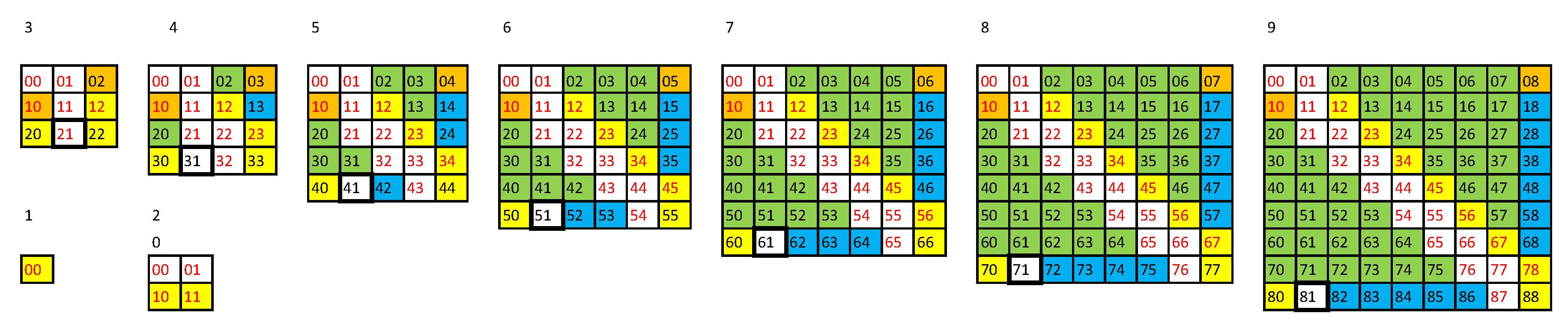

Appendix A.15. The 2nd Method for Generating C (N-1) Strings

- (1)

- we check subsequent subdiagonals until we find one that does not contain a 2-gram present in the string formed so far, we append it at the end of this string and proceed to step 2;

- (2)

- we check subsequent superdiagonals until we find one that does not contain a 2-gram present in the string formed so far, we append it at the end of this string and proceed to step 1.

Appendix A.16. Method for Generating Non-Balanced C (N-b) Strings

References

- Wootters, WK; Zurek, WH. A single quantum cannot be cloned. Nature 1982, 299(5886), 802–3. Available online: http://www.nature.com/articles/299802a0. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, SM; Murray, ARG; Cronin, L. A probabilistic framework for identifying biosignatures using Pathway Complexity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences Available from. 2017, 375(2109), 20160342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imari Walker, S; Cronin, L; Drew, A; Domagal-Goldman, S; Fisher, T; Line, M. Probabilistic Biosignature Frameworks. In Planetary Astrobiology; Meadows, V, Arney, G, Schmidt, B, Des Marais, DJ, Eds.; University of Arizona Press, 2019; pp. 1–1. Available online: https://uapress.arizona.edu/book/planetary-astrobiology.

- Planetary astrobiology. In University of Arizona space science series; Meadows, VS, Arney, GN, Schmidt, BE, Des Marais, DJ, Eds.; The University of Arizona Press: Tucson; Lunar and Planetary Institute: Houston, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y; Mathis, C; Bajczyk, MD; Marshall, SM; Wilbraham, L; Cronin, L. Exploring and mapping chemical space with molecular assembly trees. Science Advances Available from. 2021, 7(39), eabj2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, SM; Mathis, C; Carrick, E; Keenan, G; Cooper, GJT; Graham, H; et al. Identifying molecules as biosignatures with assembly theory and mass spectrometry. Nature Communications 2021, 12(1), 3033. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-23258-x. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, SM; Moore, DG; Murray, ARG; Walker, SI; Cronin, L. Formalising the Pathways to Life Using Assembly Spaces. Entropy 2022, 24(7), 884. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/24/7/884. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A; Czégel, D; Lachmann, M; Kempes, CP; Walker, SI; Cronin, L. Assembly theory explains and quantifies selection and evolution. Nature 2023, 622(7982), 321–8. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06600-9. [CrossRef]

- Jirasek, M; Sharma, A; Bame, JR; Mehr, SHM; Bell, N; Marshall, SM; et al. Investigating and Quantifying Molecular Complexity Using Assembly Theory and Spectroscopy. ACS Central Science Available from. 2024, 10(5), 1054–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukaszyk, S; Bieniawski, W. Assembly Theory of Binary Messages. Mathematics 2024, 12(10), 1600. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7390/12/10/1600. [CrossRef]

- Raubitzek, S; Schatten, A; König, P; Marica, E; Eresheim, S; Mallinger, K. Autocatalytic Sets and Assembly Theory: A Toy Model Perspective. Entropy 2024, 26(9), 808. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/26/9/808. [CrossRef]

- Łukaszyk, S. On the "Assembly Theory and its Relationship with Computational Complexity. 2024. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202412.1492/v1.

- Patarroyo, KY; Sharma, A; Seet, I; Packmore, I; Walker, SI; Cronin, L. Quantifying the Complexity of Materials with Assembly Theory ArXiv:2502.09750. arXiv. 2025. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2502.09750.

- Masierak, P. Computational Complexity of Determining the Assembly Index. Available from. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ziv, J; Lempel, A. Compression of individual sequences via variable-rate coding. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1978, 24(5), 530–6. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1055934. [CrossRef]

- Storer, JA; Szymanski, TG. Data compression via textual substitution. Journal of the ACM Available from. 1982, 29(4), 928–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch. A Technique for High-Performance Data Compression. Computer 1984, 17(6), 8–19. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1659158. [CrossRef]

- Charikar, M; Lehman, E; Liu, D; Panigrahy, R; Prabhakaran, M; Sahai, A; et al. The Smallest Grammar Problem. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2005, 51(7), 2554–76. Available online: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1459058/. [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, JC; Yang, En-Hui. Grammar-based codes: a new class of universal lossless source codes. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2000, 46(3), 737–54. Available online: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/841160/. [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, J; Yang, En-hui; Park, T; Yakowitz, S. Complexity of preprocessor in MPM data compression system. Proceedings DCC ’98 Data Compression Conference (Cat. No.98TB100225), 1998; IEEE Comput. Soc: Snowbird, UT, USA; p. 554. Available online: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/672292/.

- Lehman, E. Approximation Algorithms for Grammar-Based Data Compression. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), 2002. Available online: https://compression.ru/download/articles/grammar/lehman_phd_2002_approximation_algorithms.pdf.

- Kieffer, JC; Eh, Yang. Compression and Explanation using Hierarchical Grammars. The Computer Journal 2000, 43(3), 212–22. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/2826982_1_INTRODUCTION_Compression_and_Explanation_using_Hierarchical_Grammars.

- Kieffer, JC; Yang, En-Hui; Nelson, GJ; Cosman, P. Universal lossless compression via multilevel pattern matching. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2000, 46(4), 1227–45. Available online: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/850665/. [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, J; Flajolet, P; Yang, Eh. Universal Lossless Data Compression Via Binary Decision Diagrams. arXiv 2011, 1111.1432. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1111.1432. [CrossRef]

- Nevill-Manning, CG. Compression and Explanation using Hierarchical Grammars. The Computer Journal 1997, 40(2 and 3), 103–16. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/comjnl/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/comjnl/40.2_and_3.103. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, NJ; Moffat, A. Offline dictionary-based compression. Proceedings DCC’99 Data Compression Conference (Cat. No. PR00096), 1999; pp. 296–305. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/755679, ISSN 1068-0314.

- Larsson, NJ; Moffat, A. Off-line dictionary-based compression. Proceedings of the IEEE 2000, 88(11), 1722–32. Available online: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/892708/. [CrossRef]

- Nevill-Manning, C; Witten, I. Compression and Explanation using Hierarchical Grammars. In The Computer Journal; Source; CiteSeer, 1999; Volume 40, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Nevill-Manning, CG; Witten, IH. Identifying Hierarchical Structure in Sequences: A linear-time algorithm. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 1997, 7, 67–82. Available online: https://jair.org/index.php/jair/article/view/10192. [CrossRef]

- Apostolico, A; Lonardi, S. Off-line compression by greedy textual substitution. Proceedings of the IEEE 2000, 88(11), 1733–44. Available online: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/892709/. [CrossRef]

- Apostolico, A; Lonardi, S. Compression of biological sequences by greedy off-line textual substitution. Proceedings DCC 2000. Data Compression Conference, Snowbird, UT, USA, 2000; IEEE Comput. Soc; pp. 143–52. Available online: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/838154/.

- Sakamoto, H; Maruyama, S; Kida, T; Shimozono, S. A Space-Saving Approximation Algorithm for Grammar-Based Compression. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems 2009, E92-D(2), 158–65. Available online: http://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/transinf/E92.D/2/E92.D_2_158/_article. [CrossRef]

- Takabatake, Y; I, T; Sakamoto, H. A Space-Optimal Grammar Compression. LIPIcs, Volume 87, ESA 2017. 2017, 87:67, 1–67:15. Available online: https://drops.dagstuhl.de/entities/document/10.4230/LIPIcs.ESA.2017.67.

- Pagel, S; Sharma, A; Cronin, L. Mapping Evolution of Molecules Across Biochemistry with Assembly Theory. 2024. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.05993.

- Knuth, DE. The art of computer programming. In Seminumerical algorithms / Donald E. Knuth (Stanford University). Third edition, forthy-first printing ed; Addison-Wesley: Boston, 2021; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Clift, NM. Calculating optimal addition chains. Computing Available from. 2011, 91(3), 265–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, L. Exploring assembly index of strings is a good way to show why assembly & entropy are intrinsically different. 2024. Available online: https://x.com/leecronin/status/1850289225935257665.

- Łukaszyk, S. 15. In Black Hole Horizons as Patternless Binary Messages and Markers of Dimensionality; Nova Science Publishers, 2023; pp. 317–74. Available online: https://novapublishers.com/shop/future-relativity-gravitation-cosmology/.

- Łukaszyk, S. Life as the Explanation of the Measurement Problem. Journal of Physics: Conference Series Available from. 2024, 2701(1), 012124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukaszyk, S. Black hole merger as an event converting two qubits into one. Frontiers in Quantum Science and Technology 2025, 4, 1656200. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frqst.2025.1656200/full. [CrossRef]

- Gabric, D; Shallit, J; Zhong, XF. Avoidance of split overlaps. Discrete Mathematics 2021, 344(2), 112176. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0012365X20303629. [CrossRef]

- Guibas, LJ; Odlyzko, AM. String overlaps, pattern matching, and nontransitive games. Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A 1981, 30(2), 183–208. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0097316581900054. [CrossRef]

- Ozelim, L; Uthamacumaran, A; Abrahão, FS; Hernández-Orozco, S; Kiani, NA; Tegnér, J. Assembly Theory Reduced to Shannon Entropy and Rendered Redundant by Naive Statistical Algorithms. arXiv. 2025. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2408.15108.

- Abrahão, FS; Hernández-Orozco, S; Kiani, NA; Tegnér, J; Zenil, H. Assembly Theory is an approximation to algorithmic complexity based on LZ compression that does not explain selection or evolution. PLOS Complex Systems 2024, 1(1), e0000014. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/complexsystems/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcsy.0000014. [CrossRef]

- Uthamacumaran, A; Abrahão, FS; Kiani, NA; Zenil, H. On the salient limitations of the methods of assembly theory and their classification of molecular biosignatures. npj Systems Biology and Applications 2024, 10(1), 82. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41540-024-00403-y. [CrossRef]

- Vimal, D; Parzych, G; Smith, OM; Parkar, D; Bergen, S; Daymude, JJ. Open, Reproducible Calculation of Assembly Indices ArXiv:2507.08852 version: 1. arXiv. 2025. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2507.08852.

- Flamm, C; Merkle, D; Stadler, PF. Assembly in Directed Hypergraphs. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences Available from. 2025, 481(2324), 20250331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempes, CP; Lachmann, M; Iannaccone, A; MF, G; RC, M; Walker, SI; et al. Assembly theory and its relationship with computational complexity. npj Complexity 2025, 2(1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhard, TD; Bell, A; Gong, J; Hastings, JJA; Fricke, GM; Cabrol, N; et al. Inferring molecular complexity from mass spectrometry data using machine learning. Machine Learning and the Physical Sciences workshop, NeurIPS 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, L; Parra, JCM; Patarroyo, KY. Assembly Addition Chains. arXiv. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.18030.

- Krzyżanowski, W. Procesy ewolucji kulturowej muzyki w środowisku technologii cyfrowych [Rozprawa doktorska]. Poznań: Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu, Wydział Nauk o Sztuce; 2025. Praca doktorska napisana pod kierunkiem prof. UAM dr hab. Piotra Podlipniaka, złożona w 2025 r.

- Vopson, MM. The second law of infodynamics and its implications for the simulated universe hypothesis. AIP Advances 2023, 13(10), 105308. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/adv/article/13/10/105308/2915332/The-second-law-of-infodynamics-and-its. [CrossRef]

- Mugur-Schachter, M. On a Crucial Problem in Probabilities and Solution. arXiv. 2008. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/0801.2654.

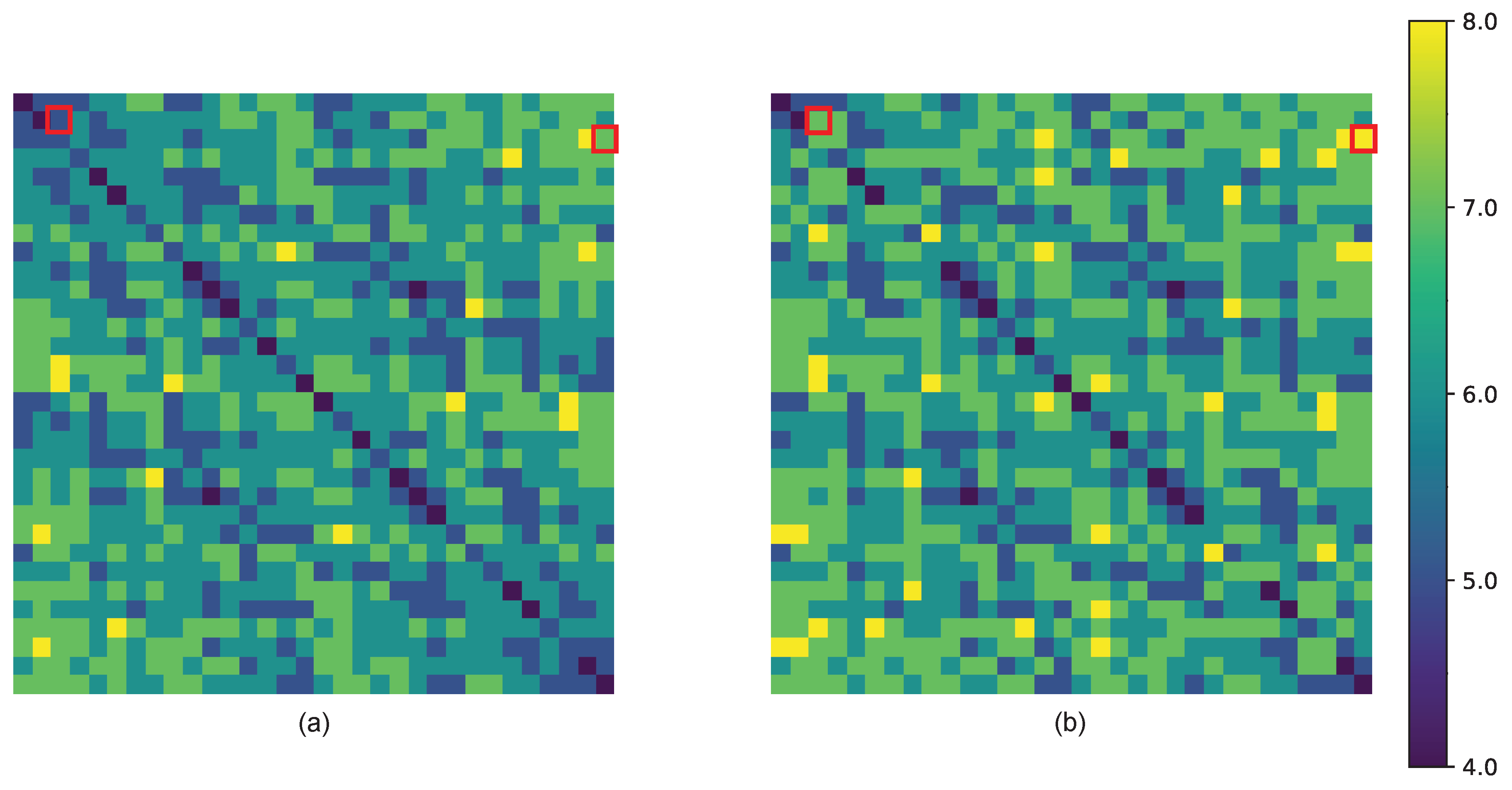

| 1 | Sixteen if we relax the Definition 2.5 (cf. Figure 9b). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).