1. Introduction

Coal, also called fossil fuel [

1], which has been used for heating and cooking since cavemen, is derived from open-cast mines (53%), ground bord-and-pillar operations (40%), stopping (4%), and longwall mining (3%) [

2]. Coal remains South Africa’s (SA) primary energy source at 70%. Thus, commercial coal mining activities in SA started as early as 1870 and increased between 1879 and 1889 to support gold and diamond mining endeavors [

3]. Since other countries such as India get coal from SA, exploration of new coal fields remains active, currently involving Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), leading to the establishment of over 20 junior coal mining and exploration companies in South Africa. The concern is that coal mining activities produce huge tons of mineral waste, causing ambient (outdoor) air pollution and poor air quality.

The World Health Organization (WHO) [

4] asserts that in 2019, approximately 99% of the world's population resided in areas that did not meet the WHO's air quality guidelines. Thus, such populations breathe in air that contains high levels of pollutants. According to the WHO [

5], low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) are suffering from the highest exposures to ambient air pollution, with nitrogen dioxide (NO2) being one of the main pollutants. The concern is that NO2 is known to cause health issues such as asthma, lung inflammation, and reduced lung function. Thus, particles with a diameter of 10 microns or less (<PM 10) can penetrate and lodge deep inside the lungs, causing irritation and inflammation and damaging the lining of the respiratory tract [

6,

7]. Particles with a diameter of 2.5 microns or less have more health-damaging effects. These particles penetrate the lung barrier and enter the blood system, affecting all major organs of the body and increasing the risk of heart and respiratory diseases, as well as lung cancer and strokes [

8]. The WHO [

4] in 2019 established an association between prenatal exposure to high NO2 levels of air pollution and developmental delay at age three, as well as psychological and behavioral problems later on, including symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, and depression. According to the WHO, [

5] ambient air pollution resulted in 4.2 million premature deaths worldwide in 2019, with 89% (n=1.1 million) of such premature deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries, especially across Africa. Thus, Khan & Ghouri [

9] assert that polluted air can cause a shorter lifespan.

An additional concern is that burning coal in power plants leaves behind a gray powder-like substance known as coal ash. Coal-fired power plants produce more than 100 million tons of coal ash and other waste products, about a third of which is often re-used in concrete, while the remainder is stored in landfills, abandoned mines, and hazardous, highly toxic ponds. Unlined ponds or pits store the majority of coal ash. All coal ash contains concentrated amounts of toxic elements, including arsenic, lead, and mercury. Over time, heavy metals in the ash can escape into nearby waterways and contaminate drinking water. Coal ash exposure increases the risk of cancer, heart damage, reproductive issues, neurological disorders, and other serious health conditions. The WHO [

5] revealed that the majority of global premature deaths in 2019 were due to non-communicable diseases as a result of coal mining environmental pollution. Similarly, the WHO [

13] estimates that in 2019, some 37% of environmental air pollution-related premature deaths were due to ischaemic heart disease and stroke, while 18% and 23% of deaths were due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and acute lower respiratory infections, respectively, and 11% of deaths were due to cancer within the respiratory tract.

Another coal mining concern is water pollution through acid mine drainage, which occurs when certain substances (typically iron sulfide, FeS2, or fool's gold) oxidize after exposure to air and water. Runoff can change the pH of nearby streams to the same level as vinegar or battery acid. Highly acidic water contains heavy toxic metals such as arsenic, lead, and mercury, contaminating nearby rivers, lakes, and aquifers. Skin irritation, kidney damage, and neurological diseases are some of the effects of acid mine drainage on human health. Acid rain, on the other hand, causes respiratory problems such as bronchitis, pneumonia, and permanent lung damage.

The South African National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act 39 [

10] prescribes that MECs of Health in Provinces through a gazette, and municipalities in terms of a by-law, should identify substances or mixtures of substances in ambient air which, through ambient concentrations, bioaccumulation, deposition, or in any other way, present a threat to health, well-being or the environment in the municipality or which the municipality reasonably believes present such a threat; and establish local standards for emissions from point, non-point or mobile sources based on the national ambient air quality standards [

11]; and require persons falling within specified categories to prepare and submit related environmental pollution prevention plans. According to Schedule 2 of the National Environmental Management Act 39 [

11], the national ambient air quality standards for NO2 in one hour are 200 micrograms/m

3 and 40 micrograms/m

3 annually, whereas, for particulate matter (PM10), they are 75 micrograms/m3 in 24 hours and 40 micrograms/m3 annually.

However, AQMesh, which is the organization monitoring air quality around mining facilities in South Africa, highlights that the South African average air quality (real-time PM2.5 and PM10 air pollution) level of 49 micrograms/m3 on July 26, 2024, 12:12 [

12], is above the national air quality annual standard of 40 micrograms/m3 [

13]. The CREA [

14] study detected exceedances in all air quality standards, i.e., PM

10 (daily and annual), NO

2 (hourly), SO

2 (hourly and daily), and PM

2.5 (daily and annually), which are not only restricted to nearby communities, and which increase the risk of a wide range of health outcomes for residents. Statistics SA [

15] highlights that in 2017, Limpopo was the province of usual residence for 10.2% (n = 40685) of the deceased, with tuberculosis (TB) ranking as the No. 1 cause of death at 6.4%, followed by diabetes mellitus (5.7%), 125 cerebrovascular disease (5%), other forms of heart disease (4.9%), HIV 126 (4.8%), hypertension diseases (4.5%), influenza and pneumonia (4.2%), and 127 chronic lower respiratory diseases (2.9%). According to Statsa [

15], Capri-128 corn district had the highest number (n = 12, 206) of deaths in 2017, followed 129 by Mopani (8,961), Greater Sekhukhune (8,632), Vhembe (7931), and Water-130 berg (5,977).

Problem Statement

The proportion of Limpopo province morbidity attributed to environmental risks associated with mining activities remains unclear. Lack of certainty regarding the environmental risk factors underlying causes of morbidity in the province misdirect preventive intervention programs. This study aimed to map the prevalence of diseases among communities closer to coal mining activities and associated risk factors as attested by residents, to guide preventive and management intervention programs and direct future research.

Rationale

Studies investigating the perceived health impacts of coal mining activities in Limpopo Province are necessary to direct preventive programs, given that coal mining in Limpopo could potentially continue well beyond the current average mining period [

17]. Previous studies on this phenomenon include Nephalama and Muzerengi [

18], who focused on the influence of coal mining on groundwater quality at Masisi village. Additional studies focused on miners' health and safety [

20]; Chipa [

21] focused on mining corporate social responsibility and sustainable communities' livelihoods post-mine closure. All these studies did not measure the health impacts of coal mining activities as perceived by residents near mines. It is important to understand the impact of coal mining activities on the health and well-being of residents near coal mines to inform preventive and management intervention programs that mitigate the effects of mining activities and promote the well-being of residents closer to mines reducing morbidity rates.

The findings of this study may help Limpopo provincial policymakers realize the need to amend regulations (MPRDA, NEMA, and NEM: AQA) and requirements for mining activities. This study may also trigger researchers in collaboration with the Department of Environmental Affairs and the Department of Health to conduct intensive studies to confirm the findings of this study.

Research Purpose

To investigate the impact of coal mining activities on the health and well-being of communities residing closer to a coal mine as perceived by residents.

Research Objectives

To explore the perceived impact of mining activities on the health and well-being of community members near a coal mine.

To describe perceived factors associated with the health and well-being of community members exposed to coal mining activities.

Definition of Terms

Perception: The view or prospect of anything such as biological, psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, and humanistic [

22] In this study, perception refers to the view and perceptions of the community about their physical, mental, and social health and well-being.

Health impacts: Health impacts have been defined by WHO as a combination of procedures, methods, and tools by which a policy, program, or project may be judged as to its potential effects on the health of a population [

23]. In this study, health impacts refer to negative and positive changes in the community’s physical, mental, and social health resulting from exposure to mining activities around the study area.

Well-being: Well-being is the experience of health, happiness, and prosperity. In this study, well-being means physical, mental, and social wellness.

Village: A small community or group of houses and associated buildings, larger than a hamlet and smaller than a town, with a population ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand, often located in rural areas, villages are normally permanent, with fixed dwellings [

24]. In this study, the village refers to the Mutele.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology of this study is described below using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research [COREQ] [

25].

Research Approach

The qualitative exploratory design was adopted to uncover the perceived impacts of coal mining activities on the health and well-being of community members living near a mine in the Limpopo Province.

Research Design

The study was exploratory research, and perspectives and experiences of community members concerning the effects of a nearby coal mine on their health and well-being were probed through direct observations and interactions during one-on-one interviews.

Study Setting

This study was conducted at Mutele Village, a community near a coal mine called Tshikondeni. The village is within the magisterial district of Mutale in the Limpopo Province. Mutele Village comprises sub-villages called Mukomawabane, Tshivaloni, Sanari, Thondoni, Tshifunguduwe and Bileni. These sub-villages are approximately 5-20 km away from the mine. All the sub-villages depend on one community health care clinic called Sanari Community Health Clinic.

Mutele Village is in Musina Local Municipality, which forms part of Vhembe District Municipality in the Limpopo Province. It is approximately 123 km from Thohoyandou and 70km from Musina and is characterized by scattered households. The road links are of poor quality except the roads to Tshikondeni Mine. The total area is 3.886 km

2 while the total population is 91, 870 [

26] with a population density of 24/km

2. The dominant language is Tshivenda at about 96.8 % and others at 3.2 %.

Tshikondeni is a coal mine with open-cast and underground mines owned and managed by Exxaro Coal. It started operations in 1984 with only an underground mine and in 2003 an open cast seam was added. Most general workers are from the surrounding communities. The mine has a high number of male employees compared to females. Some females work as domestic workers for the staff of Tshikondeni who resides at Tshikondeni Eco-village.

Study Population and Sampling

The study population comprised communities near the Tshikondeni Coal Mine. The communities around Tshikondeni Coal Mine include Tshivaloni, Mukomawabane, Bileni, Sanari, and Thondoni. However, the study specifically targeted community members residing in Mukomawabane, Bileni, and Mutele B. These three sub-villages were selected for their proximity to the coal mine (5km radius). The total area encompassing these communities is 3.886 km2;, with a combined population of 91,870 (26). The inclusion criteria for participants were individuals aged between 18 and 80 years. Participants were interviewed at preferred locations, to ensure comfort.

The study employed multistage sampling, encompassing the sub-villages, households, and the study participants. The selection of participants was based on the total population counts for sub-villages as reported by STATSSA [

26]. Sub-villages near the mine were purposefully selected. The area of interest included eight (8) sub-villages, out of which only three (3) were purposively sampled prioritizing those closer to the coal mine. The sub-villages selected include Bileni, Mukomawamabe, and Mutele B. Furthermore, random sampling was also employed to select households within the three chosen sub-villages for inclusion in the study. To accomplish this, the number of all households was written on small pieces of paper and placed in a bowl. The researcher then randomly drew a piece of paper from the bowl to determine which household would be included in the study.

Data Collection Method

In this study, data was collected using audio-recorded unstructured interviews. A carefully designed unstructured interview guide comprised of one question, namely “What are the negative things that were brought about by the coal mining activities in the bodies, mind, and community in general” was used for data collection. This tool was instrumental in facilitating discussions, enabling the researcher to delve into the lived experiences, perceptions, and conditions of life in the villages adjacent to the mine. One-on-one interviews were conducted to capture rich, in-depth information about the participants' health, well-being, and life circumstances. Recognizing the linguistic preferences and needs of the study population, most of the interview questions were translated into Tshivenda, the primary language spoken in Tshikondeni , “ndi zwhifhio zwithu zwi si zwavhudi zwe u gwiwa ha malasha kha mugodi wa Tshikondeni ho zwi bveledza fhano muvhunduni, (1) kha mivhili, (2) kha mihumbulo, na (3) kha vhadzulapo ngo angaredza”. This consideration ensured that participants could express themselves fully and comfortably, enhancing the quality and authenticity of the data collected. The data collection process was iterative, with the researcher continuing to conduct interviews until reaching a point of data saturation. Data saturation indicated that no new information emerged from the interviews, thus suggesting that the collected data sufficiently represented the phenomena under investigation.

Data Management and Analysis

Data management and analysis procedures were followed to analyze the collected data. Thematic analysis involved categorizing, manipulating, ordering, and summarizing the data to derive meaningful insights. The data were transcribed from audiotapes with a focus on accuracy and quality. Then, underlying concepts were identified to develop category themes. These themes were used to code the data consistently.

Trustworthiness Measures

In carrying out a study, it was important to ensure that data and findings represented the truth about the community’s perceptions of their health and well-being due to exposure to the selected coal mine activities. Thus, the four criteria widely used to appraise the trustworthiness of qualitative research, namely credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability were used to ensure rigor of inquiry. Prolonged engagements, persistent observations, member debriefing, and peer debriefing were used to ensure the credibility of the study findings. To ensure transferability, this detailed report of the methodology guides future researchers to reproduce the study in similar settings, ensuring transferability. To ensure dependability, an inquiry audit was performed by an external examiner appointed by the university for examination purposes. In addition, stepwise replication was done by an independent coder, and the findings were compared to inform adjustments in coding. Reflexivity of the researcher’s feelings, actions, and conflicts during data collection and analysis ensured confirmability.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Information

This study collected data from eighty-one (81) participants from three villages near Tshikondeni mine. Most participants (40.7% n=33) were from Ha-Mukomawabane; whereas 32.1%, n=26; and 27.2%, n=22 of participants were from Ha-Mutele B and Bileni villages, respectively. Regarding age, the majority of participants (51.9%) were adults, i.e., aged between 36 and 60 years old. Youths only constituted a third of the study sample, with the elderly (over 61 years) comprising almost 15%. Most participants were women, who constituted about 60% of the sample; 53.1% were single, 6.2% were cohabiting, 3.3% were married, and 7.4% were widowed. Concerning the level of education, more than half, i.e., 66.7% of the participants, had attained a secondary level education, with only 7.4 without a known education level and less than 5% with tertiary education. Only a fifth of the sample had primary education. Finally, the majority (51.9%) of the participants were unemployed, with only 35.8% reporting being employed. More than 10% of the sampled participants were unemployed (see

Appendix A: Table 2 for details)

3.2. Themes and Sub-Themes

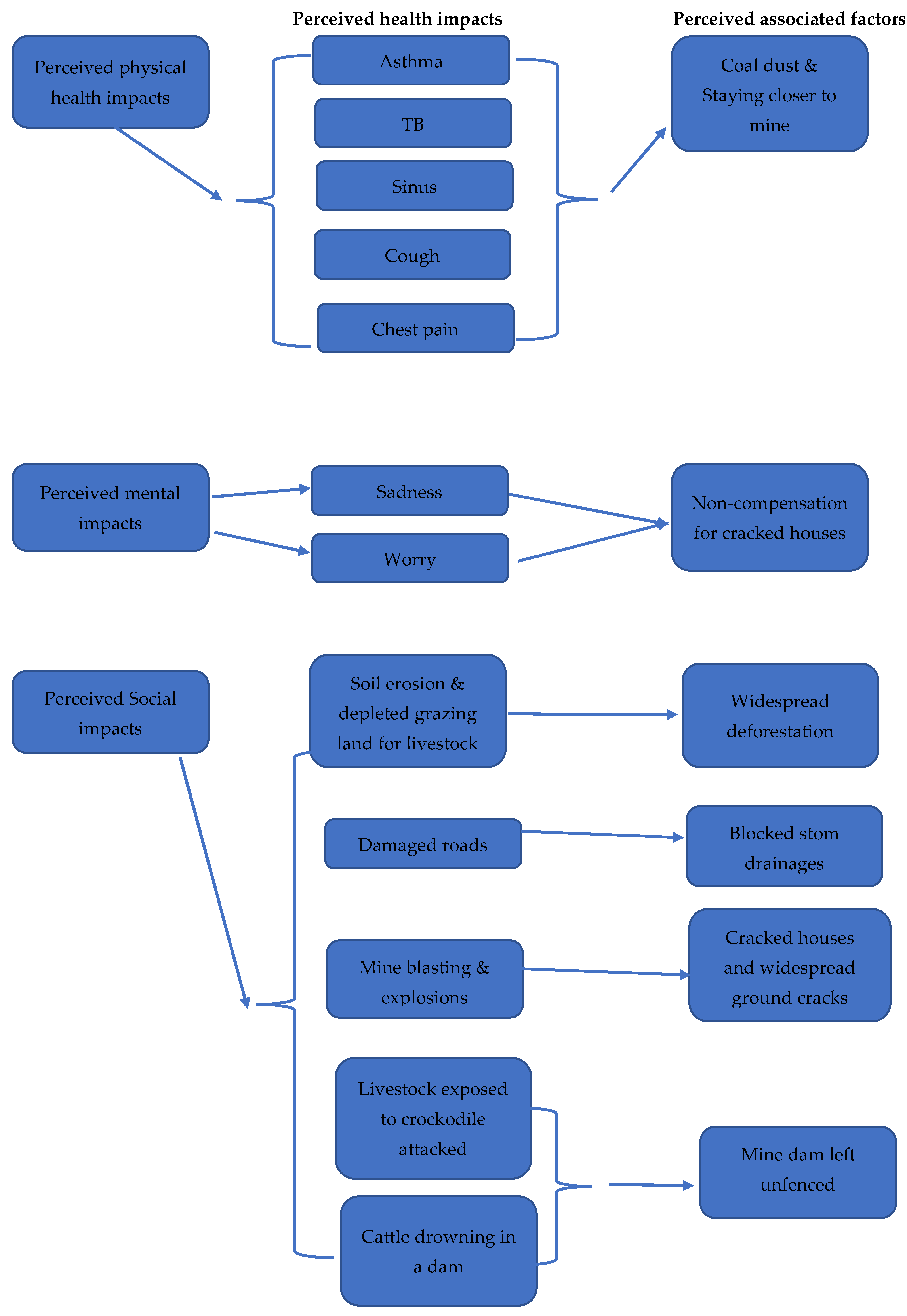

Two themes emerged from the thematic analysis of the data (see

Table 3), encapsulating the community's perceptions of the impacts of coal mining and the factors associated with the health and well-being of individuals exposed to such activities. Theme 1, is about the community's perceived impacts of coal mining on physical, mental, and social well-being. Theme 2 explored perceived factors associated with the health and well-being of individuals exposed to coal mining.

THEME 2: Perceived Factors Associated with the Health and Well-Being of Individuals Exposed to Coal Mining

This section presents factors perceived to be responsible for health and well-being perceived impacts among communities close to the Tshikondeni mine, namely coal dust pollution, staying close to the mine, deforestation, mine blasting, and explosions, blocked storm water drainage, Dam that mine left unfenced.

2.1. Coal Dust Pollution

Coal dust pollution emerged strongly as a perceived cause of all self-proclaimed respiratory-related conditions such as Asthma, TB, sinuses, coughs, and chest pain.

P2, P4, P5, P7 says, “I think my chest pain and weight loss are caused by mining dust.

“Malasha o vha atshi duba ri tshi fema one, nne ndi vho lwala TB” – translated- we were breathing coal dust, thus, why I am now sick”; “ we now have breathing problems, the dust affected our breathing”P18, P19; “ … ho vha na mafhungo a mabuse manzhi” – translated – “There was a lot of dust”P24, P28; “Nne ndi khou lwala nga nwambo wa malasha – translated – “ I am sick because of coal”P44; Mugodi wo balelwa u protecta tshitshavha kha dust – translated – “the mine failed to protect people from dust)”P26; “Ndi ngauri ri tsinisa na mugodi lune u duba ha buse la hone zwa ri swikela” – translated- “ we are so close to the mine, such that the coal dust could reach us”P23

2.2. Staying Close to Mine

Residing close to Tshikondeni mine was also expressed by some participants as a cause of sicknesses among residents and creches. Participants had this to say, “Coal mine and living closer to mine is causing sicknesses around the community and creches” P45. “Ndi ngauri ri tsinisa na mugodi lune u duba ha buse la hone zwa ri swikela” – translated- “ we are so close to the mine, such that the coal dust could reach us”P23

2.3. Deforestation

Participants expressed concerns about widespread deforestation from coal mine operations as the cause of soil erosion and land degradation in communities close to Tshikondeni Mine. P66, P68, P70 says, “Mugodi wo remekanya madaka u si tavhe minwe miri” – Translated – “ mine cutdown the forests and never plant new trees” P61, P62, P70, P79 says, “Ho no dalesa mikumbululo kha vhupo hashu” – translated – there is so much soil erosion lately”; P64 says, “ Zwifuwo a zwi tshena pfulo, mahatsi ha tsha mela” – translated – “grass for livestock grazing no longer grow”.

2.4. Mine Blasting and Explosions

Some participants indicated that mine blasting operations and explosions cracked land and houses. P66, P70, P 71, P72, P73 says, “Mine u tshi thuthubisa malasha hovha na u bva mitwe kha dzinndu dzashu, na nahasi a vho ngo ri lilisa” – translated – “the mine blastings and explosions cracked our houses, but to date we were never compensated"

2.5. Blocked Storm Drainage

Some participants blamed the mine for blocked storm drainage. P52 says, “Mine caused blocked storm drainage and damaged roads”.

2.6. Mine Dam Left Unfenced

Some participants expressed concern about the dam that Tshikondeni mine left unfenced, as it is exposing their livestock to crocodiles’ attacks. P69, P73, P80 say, “Damu le mugodi wa sia li na ngwena, a longo dzharateliwa, li khou ri fhedzela zwifuwo” – translated – “The mine left an unfenced dam which is having crocodiles that are finishing our livestock”

2.7. Non-Compensation of Cracked Houses

More than a quarter of participants (24) displayed worry and saddness about the non-compensation of their cracked houses from mine blasting operations. P66, P70, P 71, P72, P73 says, “Mine u tshi thuthubisa malasha hovha na u bva mitwe kha dzinndu dzashu, na nahasi a vho ngo ri lilisa” (zwifhatuwo zwo nzwinzwimala) – translated – “the mine blastings and explosions cracked our houses, but to date we were never compensated" (sad worried facial expressions).

Figure 1 below summarizes the study findings for ease of clarity.

Figure 1.

Summary of the study findings.

Figure 1.

Summary of the study findings.

4. Discussion

The study findings indicate TB as the second most prevalent condition among communities closer to the Tshikondeni coal mine. These findings concur with STAS SA [

15], where TB was ranked 6 among the top 10 leading underlying causes of death in South Africa in 2020. These findings might mean that most TB disease in South Africa is associated with environmental dust pollution from mining activities. It is widely known that silica dust produced in almost every mining activity [

27] is a significant risk factor for TB [

28]. According to the New York State Department of Health [

29], quartz is the most common form of silica and the second most common mineral on the earth’s surface produced in nearly all mining operations and is associated with TB. However, Kootbodien T, Iyaloo S, Wilson K, et al [

30] found no association between TB and environmental exposure to gold mine tailing dust in Gauteng, Johannesburg, South Africa. More studies are needed to determine if the cause of TB among communities closer to the Tshikondeni mine is silica dust, so that preventive measures may be enforced to reduce the TB burden in the Limpopo Province and South Africa in general. These findings imply that the Department of Health, South Africa should redirect efforts towards making communities closer to mines aware and able to protect themselves from the dust produced from mining activities.

The study findings reveal that to date the Tshikondeni mine failed to compensate many residents for cracked houses due to blasting and explosion mining operations. In addition, there is a dam that the mine left unfenced, which is exposing livestock to crocodile attacks and drowning. All these situations make the communities distraught and dragged down to much deeper poverty than they were before the mining establishment in the area. These findings indicate that the Tshikondeni mine, a subsidiary of EXXARRO got away with the mindlessness of communities in its proximity. These findings concur with what happened over the past decades where the mining sector was seen as not being mindful of its immediate stakeholders, failing to consider the environment within which they operate, often leaving the impression that mines simply, degraded the environment without contributing to sustainable local development such as poverty alleviation, improving health and well-being, infrastructure, education status and reducing unemployment [

31]. The findings imply that the Tshikondeni mine operates against Mining Charter 111 of South Africa [

32], which compels mining companies to contribute towards community development. Thus, communities remain fixing their cracked houses when the mine has gained wealth from coal extracted from their land. Contrary to the findings of this study, Tshabalala [

33] argues that the EXXARRO mines in other settings had economic benefits to communities through many social and labor plan projects ranging from paving, farming, soap making, baking, etc.

Social Well-Being Impact of Tshikondeni Mine on Communities

The findings reveal how the social well-being of communities close to Tshikondeni Mine is impacted namely, soil erosion and land degradation, cracked houses, livestock exposed to crocodile attacks, damaged roads, and diminishing grazing area for livestock. The impacts highlighted in these findings are linked to deforestation for mining operations, namely soil erosion and land degradation, damaged roads, and diminishing grazing areas. For example, soil erosion means that the fertility of the soil to produce good crops and ensure food security is lost [

34]; when the grass is no longer growing, grazing areas are depleted, affecting livestock, food security, and livelihoods of communities[

34]. Damaged roads on the other hand affect the transportation of food, goods, and people’s movements in and out of the affected areas, which impacts food security and the livelihood of communities in general [

34]. Similar findings by Thakur TK, Dutta J, Bijalwan, et al [

35] indicate that in India dense native vegetation decreased drastically (by 13.74 km

2) with the gradual and consistent expansion in the activities of coal mines; and that soil and vegetation are degraded over the large mining areas consistently over a long time. These findings imply that restoration of soil health through organic matter replenishment and mineral nutrients via vegetation development is indispensable in communities near coal mines.

5. Conclusions

Communities closer to coal mines experience a variety of physical, mental, and social well-being challenges related to mining operations, non-compliance, and negligence. The South African Department of Health, Environmental Affairs, and Mineral and Energy should work together, to ensure the implementation of policies to protect communities closer to mines against harmful mining operations, non-compliance, and negligence. A follow-up study is needed to confirm the prevalence of claimed physical well-being challenges where clinic document review and diagnostic surveillance research would be done.

Limitations

The perceived physical impacts were not verified scientifically. Most participants were reluctant to participate, their perceptions could have added value to the study findings. The Tshikondeni eco-village was excluded from the study because only mine workers live in that village. Opinions and perceptions of the excluded group could have given a more significant insight into the impacts associated with coal mining. Since coal miners were excluded in this study, occupational health impacts were not thoroughly investigated. Due to the small villages around the mine; the educational level of participants and age group hindered the researcher from getting an in-depth perception about the impacts caused by Tshikondeni Coal Mine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T. and TG.; methodology, T.; validation, TG; formal analysis T. investigation, T., resources, T.; data curation, T.; writing—original draft preparation, TG.; writing—review and editing, TG.; supervision, TG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human and Clinical Trials Research Ethics Committee (HCTREC) (protocol code FHS/22/PH/11/0610; 10/09/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data for this manuscript is obtainable from nelwamondothabelo50@gmail.com.

Acknowledgments

Heartfelt gratitude goes to the communities near Tshikondeni Coal Mine for their willingness to participate and share their invaluable insights. This study would not have been possible without their cooperation and contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

Table A1.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

Participant

Identity |

Name of the village |

Age |

Sex/Gender |

Marital

Status |

Level of

Education |

Employment

status |

| 1 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

52 |

Male |

Married |

Grade 12 |

Unemployed |

| 2 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

40 |

Male |

Married |

Grade 10 |

Unemployed |

| 3 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

62 |

Female |

Widowed |

No education |

Pension |

| 4 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

39 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 10 |

Unemployed |

| 5 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

68 |

Male |

Married |

Standard 6 |

Pension |

| 6 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

83 |

Female |

Married |

No education |

Unemployed |

| 7 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

25 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 12 |

Employed |

| 8 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

43 |

Male |

Cohabitation |

Grade 9 |

Employed |

| 9 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

24 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 9 |

Employed |

| 10 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

56 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 7 |

Unemployed |

| 11 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

30 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 7 |

Unemployed |

| 12 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

67 |

Male |

Married |

No education |

Unemployed |

| 13 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

57 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 9 |

Unemployed |

| 14 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

28 |

Female |

Single |

Tertiary |

Unemployed |

| 15 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

24 |

Female |

Single |

Tertiary |

Employed |

| 16 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

36 |

Male |

Married |

Grade 11 |

Employed |

| 17 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

50 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 11 |

Employed |

| 18 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

40 |

Female |

Cohabitation |

Grade 9 |

Employed |

| 19 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

36 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 11 |

Employed |

| 20 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

31 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 10 |

Unemployed |

| 21 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

59 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 5 |

Pension |

| 22 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

47 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 12 |

Unemployed |

| 23 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

66 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 8 |

Pension |

| 24 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

25 |

Female |

Cohabitation |

Grade 11 |

Unemployed |

| 25 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

29 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 11 |

Unemployed |

| 26 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

19 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 10 |

Unemployed |

| 27 |

Bileni |

30 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 10 |

Employed |

| 28 |

Bileni |

59 |

Female |

Single |

Standard 4 |

Unemployed |

| 29 |

Bileni |

41 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 11 |

Employed |

| 30 |

Bileni |

76 |

Male |

Married |

Standard 6 |

Unemployed |

| 31 |

Bileni |

38 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 8 |

Employed |

| 32 |

Bileni |

25 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 11 |

Unemployed |

| 33 |

Bileni |

29 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 9 |

Employed |

| 34 |

Bileni |

48 |

Male |

Married |

Standard 5 |

Unemployed |

| 35 |

Bileni |

36 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 10 |

Employed |

| 36 |

Bileni |

23 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 11 |

Unemployed |

| 37 |

Bileni |

46 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 8 |

Unemployed |

| 38 |

Bileni |

36 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 12 |

Employed |

| 39 |

Bileni |

30 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 12 |

Employed |

| 40 |

Bileni |

72 |

Male |

Married |

Standard 1 |

Pension |

| 41 |

Bileni |

33 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 10 |

Employed |

| 42 |

Bileni |

31 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 9 |

Employed |

| 43 |

Bileni |

29 |

Male |

Cohabitation |

Grade 11 |

Employed |

| 44 |

Bileni |

56 |

Male |

Married |

Standard 4 |

Unemployed |

| 45 |

Bileni |

53 |

Female |

Single |

Standard 4 |

Employed |

| 46 |

Bileni |

Uknown |

Male |

Widowed |

No education |

Pension |

| 47 |

Bileni |

18 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 10 |

Unemployed |

| 48 |

Bileni |

35 |

Female |

Cohabitation |

Grade 10 |

Employed |

| 49 |

Ha-Mutete B |

38 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 12 |

Unemployed |

| 50 |

Ha-Mutete B |

65 |

Male |

Single |

Standard 3 |

Pension |

| 51 |

Ha-Mutete B |

55 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 11 |

Unemployed |

| 52 |

Ha-Mutete B |

42 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 11 |

Unemployed |

| 53 |

Ha-Mutete B |

44 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 12 |

Employed |

| 54 |

Ha-Mutete B |

48 |

Male |

Widowed |

Standard 7 |

Employed |

| 55 |

Ha-Mutete B |

54 |

Female |

Single |

Standard 4 |

Employed |

| 56 |

Ha-Mutete B |

53 |

Female |

Married |

Standard 10 |

Unemployed |

| 57 |

Ha-Mutete B |

26 |

Male |

Single |

Tertiary |

Unemployed |

| 58 |

Ha-Mutete B |

38 |

Male |

Married |

Standard 6 |

Unemployed |

| 59 |

Ha-Mutete B |

33 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 11 |

Employed |

| 60 |

Ha-Mutete B |

41 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 12 |

Employed |

| 61 |

Ha-Mutete B |

61 |

Female |

Married |

Standard 4 |

Unemployed |

| 62 |

Ha-Mutete B |

35 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 10 |

Unemployed |

| 63 |

Ha-Mutete B |

45 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 11 |

Unemployed |

| 64 |

Ha-Mutete B |

23 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 12 |

Unemployed |

| 65 |

Ha-Mutete B |

47 |

Male |

Married |

Grade 10 |

Unemployed |

| 66 |

Ha-Mutete B |

60 |

Female |

Single |

Standard 10 |

Unemployed |

| 67 |

Ha-Mutete B |

99 |

Female |

Widowed |

No education |

Pension |

| 68 |

Ha-Mutete B |

23 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 12 |

Unemployed |

| 69 |

Ha-Mutete B |

44 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 11 |

Unemployed |

| 70 |

Ha-Mutete B |

54 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 10 |

Unemployed |

| 71 |

Ha-Mutete B |

53 |

Female |

Widowed |

Grade 12 |

Employed |

| 72 |

Ha-Mutete B |

60 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 10 |

Pension |

| 73 |

Ha-Mutete B |

79 |

Female |

Widowed |

No education |

Pension |

| 74 |

Ha-Mutete B |

21 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 12 |

Unemployed |

| 75 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

40 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 8 |

Unemployed |

| 76 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

53 |

Female |

Married |

Grade 11 |

Employed |

| 77 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

28 |

Male |

Single |

Tertiary |

Unemployed |

| 78 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

43 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 10 |

Unemployed |

| 79 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

42 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 10 |

Employed |

| 80 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

42 |

Male |

Single |

Grade 10 |

Employed |

| 81 |

Ha-Mukomawabane |

29 |

Female |

Single |

Grade 11 |

Unemployed |

References

- Elem. Fossil energy study guide: Coal, 2024 https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/Elem_Coal_Studyguide.pdf.

- CSIR. Introduction to South African coal mining and exploration, 2015. https://researchspace.csir.co.za/dspace/bitstream/handle/10204/8153/McGill_2015.pdf?sequence=1#:~:text=Coal%20was%20discovered%20in%20KwaZulu,the%20Eastern%20Cape%2C%20in%2018701.

- Environmental Monitoring Group, 2010. The Social and Environmental Consequences of Coal Mining in South Africa: A Case Study, 2010. https://www.bothends.org/uploaded_files/uploadlibraryitem/1case_study_South_Africa_updated.pdf.

- World Health Organization. How air pollution is affecting our health, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/how-air-pollution-is-destroying-our-health.

- World Health Organisation. Ambient (outdoor) air pollution, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health.

- Chiluba, B. C. ‘Critical review of Dust in the Mining Environment: A focus on Workers and Community Health’. University of Zambia, 2018. School of Health Sciences. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints201811. 002.v1. [CrossRef]

- Michael H. ‘The public health impacts of surface coal mining’. Department of Applied Health Science. Indiana University, 2015. Bloomington. IN 47405, USA.

- Ncube, V. ‘South Africa’s “Deadly Air” Case Highlights Health Risks from Coal’. Environmental and Human Rights, 2021. South Africa.

- Khan MA, Ghouri AM. Environmental pollution: its effects on life and its remedies. Researcher World: Journal of Arts, Science & Commerce. 2011, 2, 276–285.

- South Africa. National Environment Management: Air Quality Act (no. 39 of 2004). https://www.dffe.gov.za/sites/default/files/legislations/nema_amendment_act39.pdf.

- South Africa. National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act: National Ambient Air Quality Standards, 2009. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/328161210.pdf.

- AQI. South Africa air quality Index real-time PM2.5, PM10 air pollution level 26 July 2024, 12:00 pm. https://www.aqi.in/dashboard/south-africa.

- AQMesh. AQMesh monitors air quality around mining facilities in South Africa, 2020. https://www.aqmesh.com/news/aqmesh-monitors-air-quality-around-mining-facilities-in-south-africa/.

- Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA). Air quality, health, and economic impacts of a new coal mine and power plant in Lephalale, 2023. https://energyandcleanair.org/publication/air-quality-health-and-economic-impacts-of-a-new-coal-mine-and-power-plant-in-lephalale/.

- Statistics South Africa. Mortality and causes of death in South Africa: Findings from death notification, 2020. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03093/P030932017.pdf.

- Prüss-Ustün A, Wolf J, Corvalán C, Neville T, Bos R, Neira M. Diseases due to unhealthy environments: an updated estimate of the global burden of disease attributable to environmental determinants of health. Journal of Public Health 2017, 39, 464–475. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs. South Africa has less than 50 years of mining left, Dialy investor, 2023. https://dailyinvestor.com/mining/34217/south-africa-has-less-than-50-years-of-mining-left/#:~:text=South%20Africa%20has%20approximately%20261,concentrated%20in%20a%20single%20mine.

- Nephalama, A. and Muzerengi, C. ‘Assessment of the influence of Coal mining on groundwater quality. Case of Masisi village in the Limpopo Province of South Africa.’ University of Venda, 2023.

- Momoh, A. , et al. ‘Potential implications of mine dusts on human health’. A case study of Mukula Mine, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Pak J Med Sc. 2013, 29, 14441446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthelo, L. Strategies to enhance compliance with health and safety standards at the selected mining industries in Limpopo Province, South Africa: occupational health nurse's perspective (Doctoral dissertation). Ulspace.ul.ac.za.

- Chipa, M. J. Mining, corporate social responsibility and communities in Limpopo Province: the case study of Mogalakwena Local Municipality, 2021. Scholar.ufs.ac.za.

- Martino, L. ‘Concepts of Health, wellbeing & Illness’. Health Knowledge Education, 2017. CPD & Revalidation from Phast.

- World Health Organization. Ambient air pollution: A global assessment of exposure and burden of diseases, 2016. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/250141/?

- Adam, V.Y. and Awunor, N.S. ‘Perception and factors affecting utilization of health services in a rural community in Southern Nigeria’. Journal of Medicine and Biomedical Research 2014, 13, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007, 19, 49–357. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. ‘Mid-year population estimates, 2017. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=2990.

- Gottesfeld P, Tirima S, Anka SM, Fotso A, Nota MM. Reducing lead and silica dust exposures in small-scale mining in northern Nigeria. Annals of work exposures and health. 2019, 63, 1–8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte J, Castelo Branco J, Rodrigues F, Vaz M, Santos Baptista J. Occupational exposure to mineral dust in mining and earthmoving works: A scoping review. Safety. 2022, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NewYork State Department of Health. Silicosis and Mining: Information for Workers. 2024 https://www.health.ny.gov/environmental/investigations/silicosis/docs/worker.pdf.

- Kootbodien T, Iyaloo S, Wilson K, Naicker N, Kgalamono S, Haman T, Mathee A, Rees D. Environmental silica dust exposure and pulmonary tuberculosis in Johannesburg, South Africa. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2019, 16, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashego, SD. Evaluating the influence of corporate social responsibility on brand reputation in the mining industry: a case study of Exxaro's Grootegeluk mine, Faculty of Commerce, Marketing, 2021. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/11427/33793.

- Mining Charter III. www.gpwonline.co.za, 2018 https://www.webberwentzel.com/News/Pages/mining-charter-iii-what-you-need-to-know-about-the-final-version-published.aspx.

- Tshabalala, EK. Corporate social responsibility: impact of Exxaro mine’s social and labor plan in the community (Doctoral dissertation, 2020, North-West University (South Africa)). https://repository.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/35931/Tshabalala_EK.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Münzel, T. , Hahad, O., Daiber, A., & Landrigan, P. J. Soil and water pollution and human health: what should cardiologists worry about? Cardiovascular research 2023, 119, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur TK, Dutta J, Bijalwan A, Swamy SL. Evaluation of decadal land degradation dynamics in old coal mine areas of Central India. Land Degradation & Development. 2022, 33, 3209–3230. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).