Submitted:

18 September 2024

Posted:

19 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Results

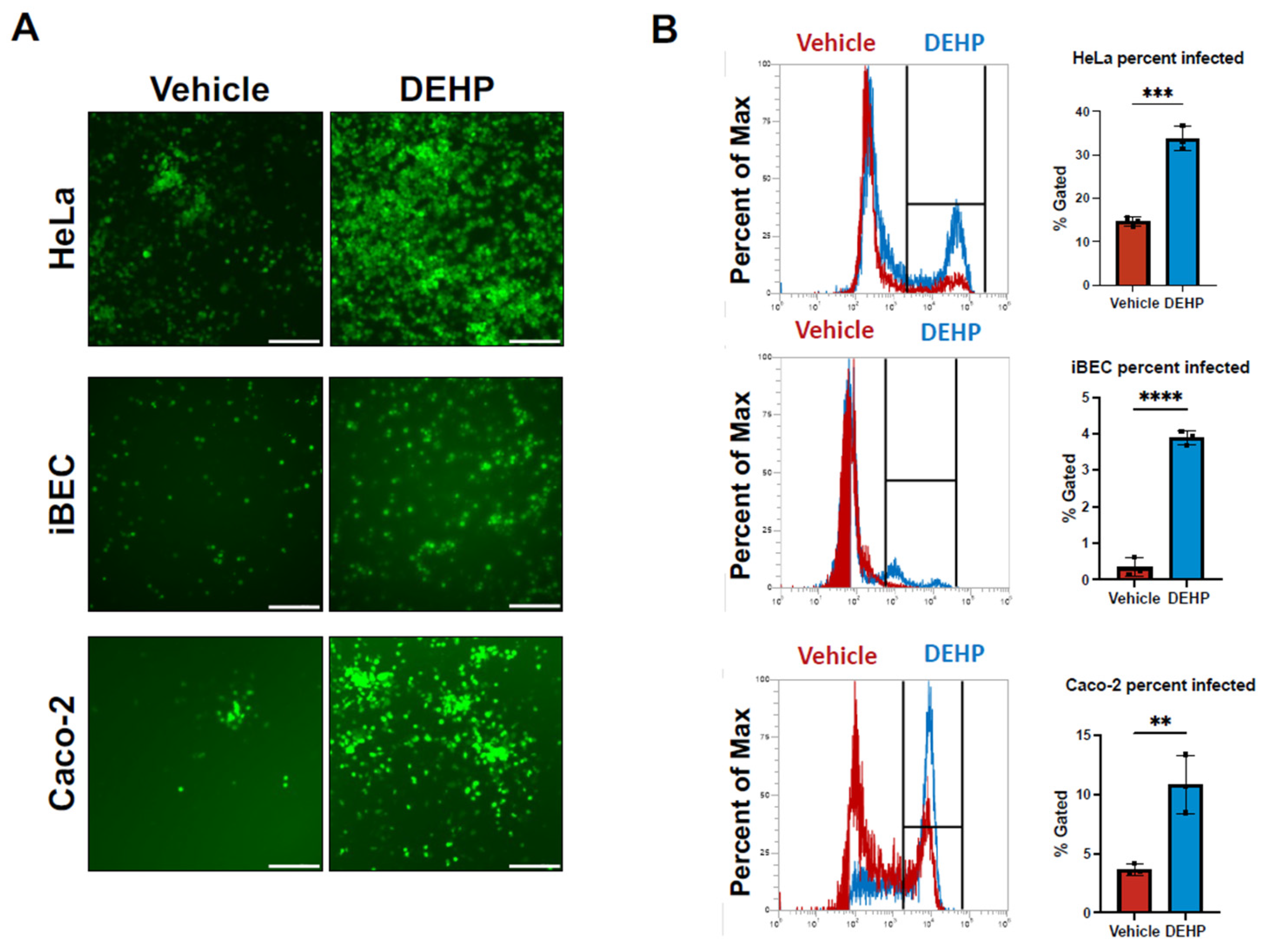

Coxsackievirus B3 Infection Increases Following Di(2-ethhylhexyl) Phthalate (DEHP) Exposure

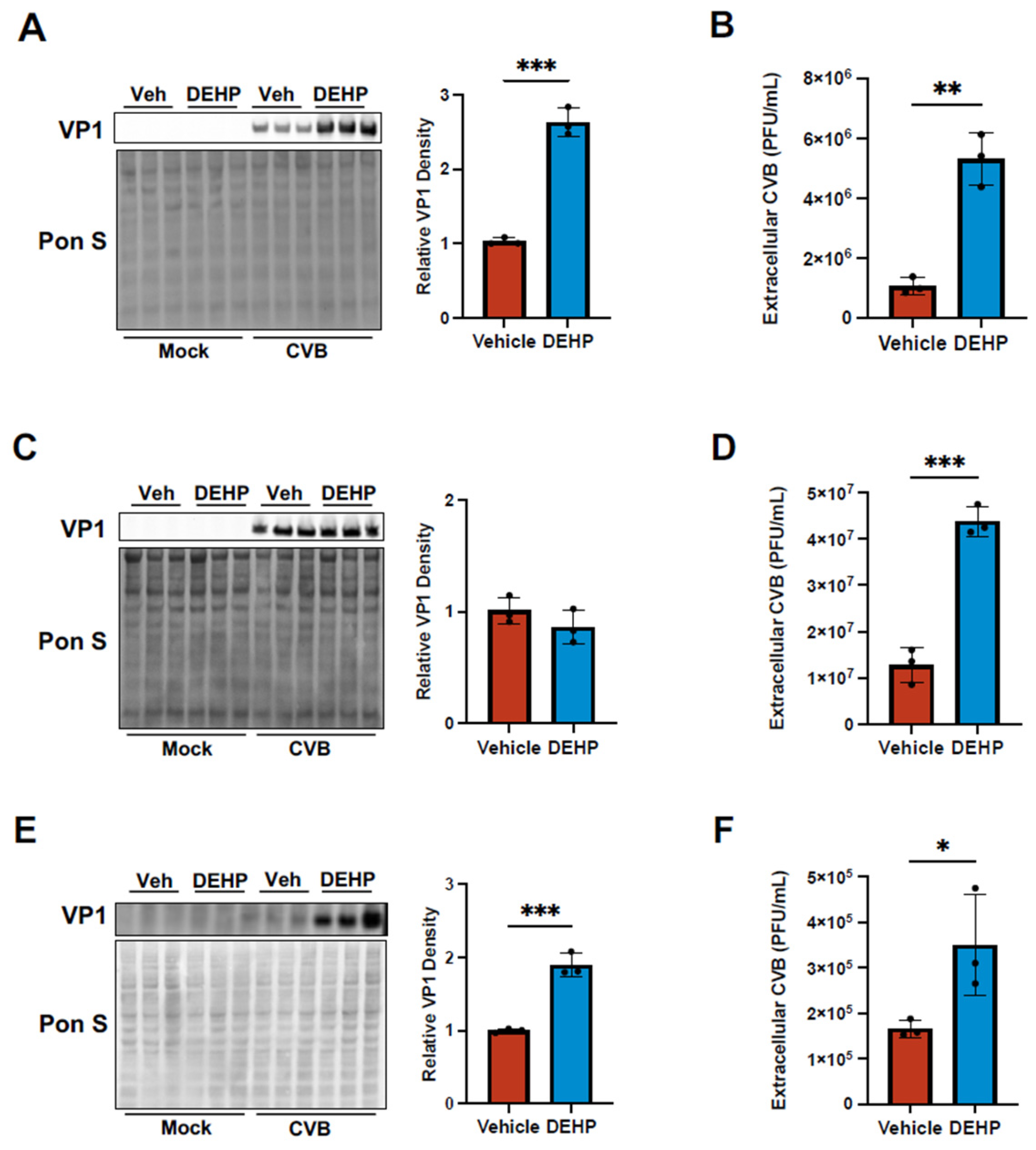

DEHP Enhances Viral Egress of CVB in Certain Cell Types

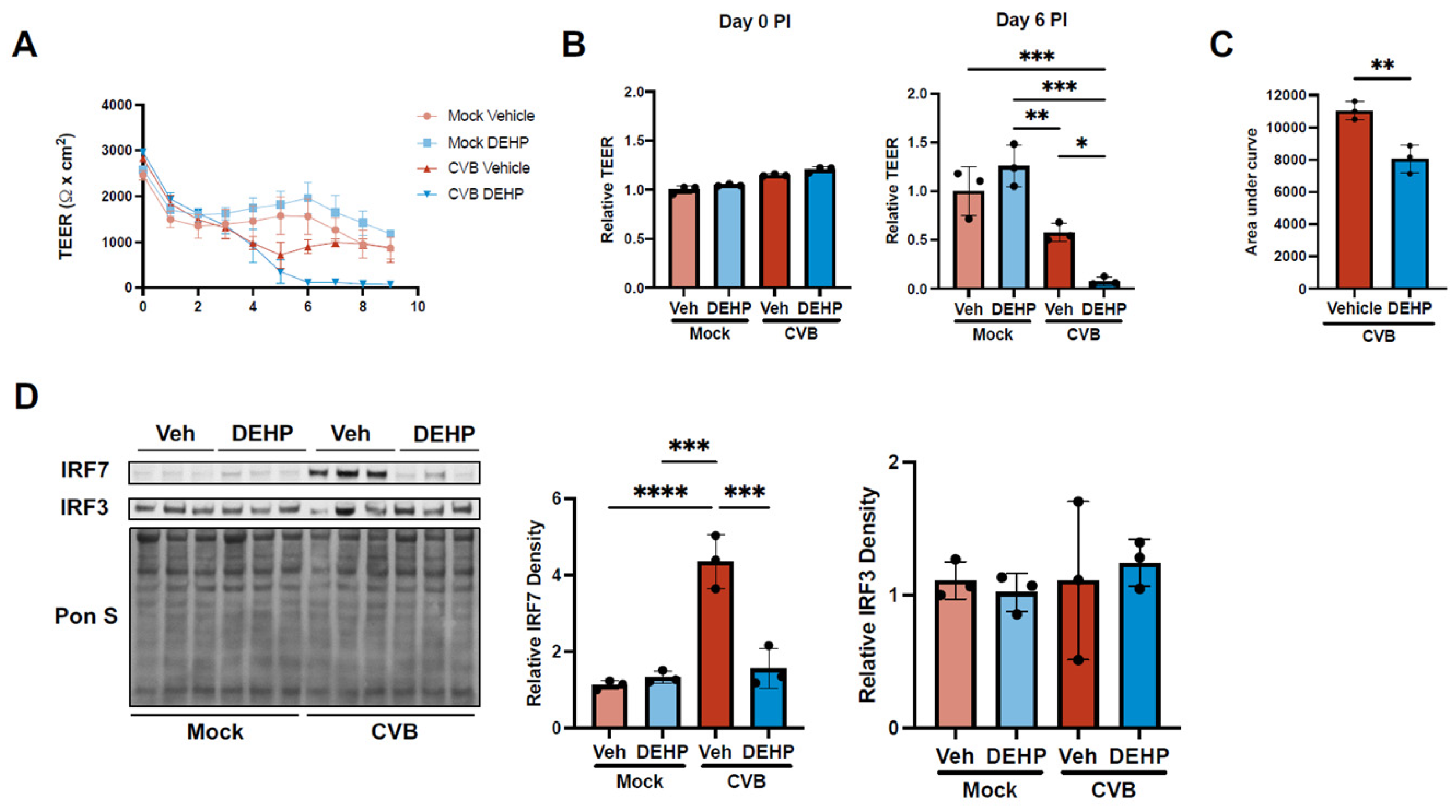

DEHP Suppresses CVB-Mediated Interferon Regulatory Factor 7 Induction in iBECs

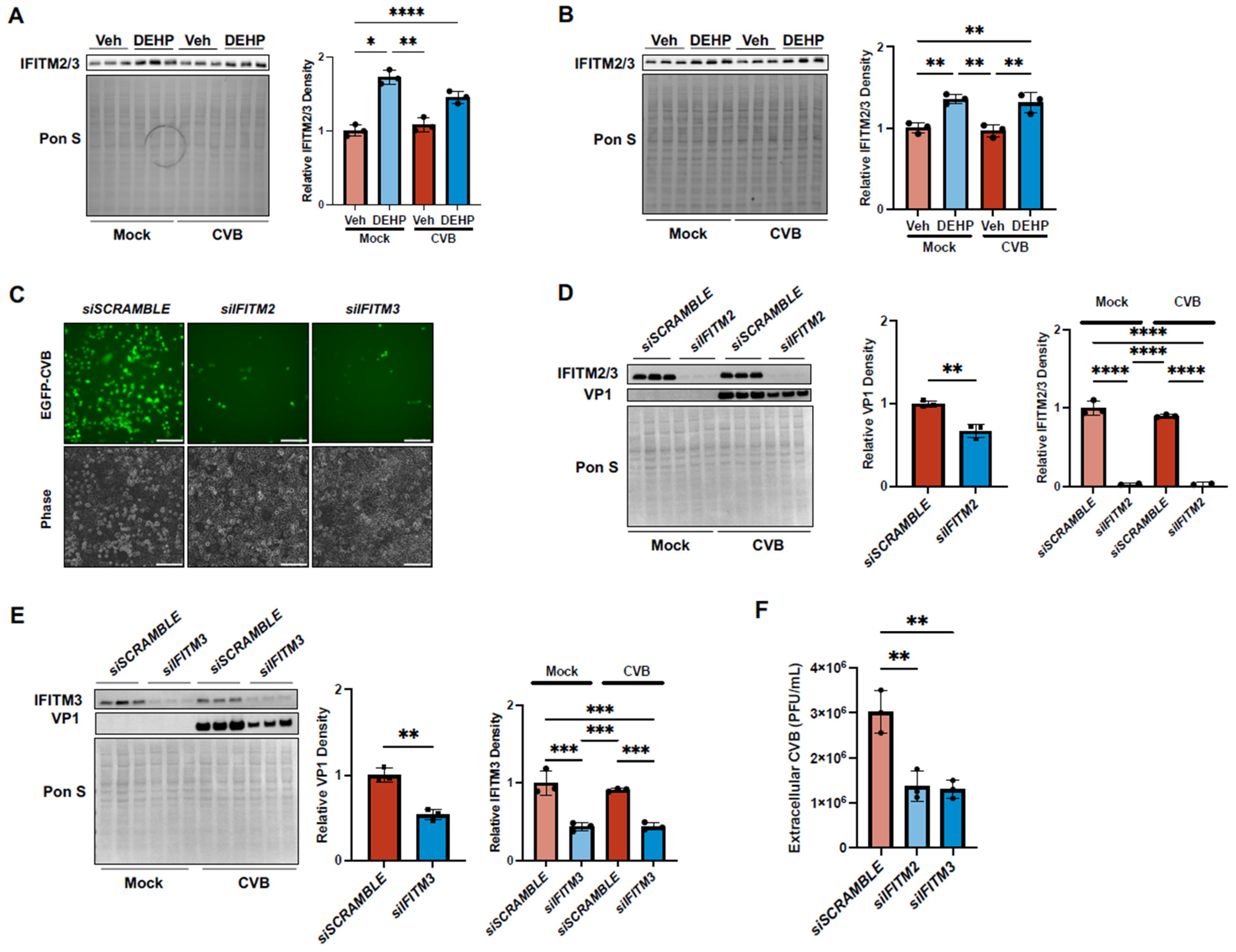

DEHP Exacerbates CVB Infection by Enhancing Interferon-Induced Transmembrane 2 and 3 in HeLas and iBECs

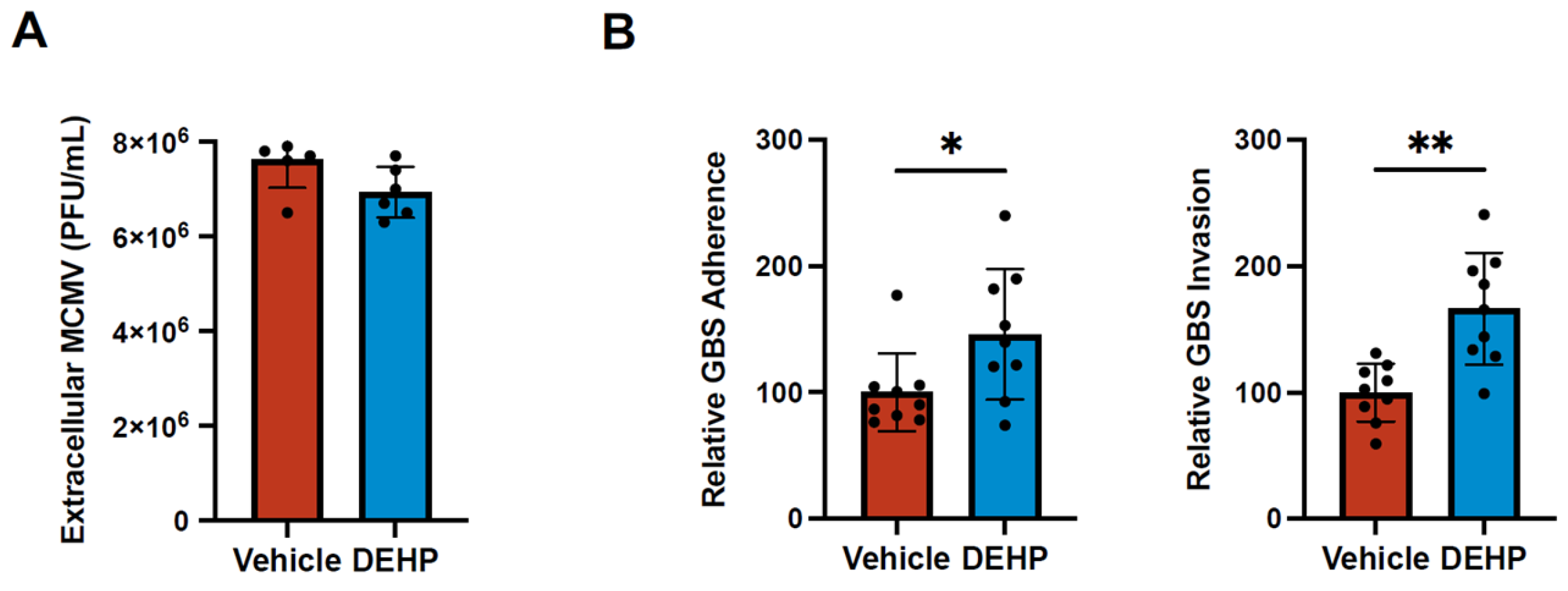

DEHP Has No Effect on Murine Cytomegalovirus Replication but Increases Group B Streptococcal Attachment and Invasion

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swift, L.M.; Roberts, A.; Pressman, J.; Guerrelli, D.; Allen, S.; Haq, K.T.; A Reisz, J.; D’alessandro, A.; Posnack, N.G. Evidence for the cardiodepressive effects of the plasticizer di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate. Toxicol. Sci. 2023, 197, 79–94. [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, R.J. and R.J. Rubin, Extraction, localization, and metabolism of di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate from PVC plastic medical devices. Environ Health Perspect, 1973. 3: p. 95-102.

- Koch, H.M., R. Preuss, and J. Angerer, Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP): human metabolism and internal exposure-- an update and latest results. Int J Androl, 2006. 29(1): p. 155-65; discussion 181-5. [CrossRef]

- Melzak, K.A.; Uhlig, S.; Kirschhöfer, F.; Brenner-Weiss, G.; Bieback, K. The Blood Bag Plasticizer Di-2-Ethylhexylphthalate Causes Red Blood Cells to Form Stomatocytes, Possibly by Inducing Lipid Flip-Flop. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2018, 45, 413–422. [CrossRef]

- Greiner, T.; Volkmann, A.; Hildenbrand, S.; Wodarz, R.; Perle, N.; Ziemer, G.; Rieger, M.; Wendel, H.; Walker, T. DEHP and its active metabolites: leaching from different tubing types, impact on proinflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecule expression. Is there a subsumable context?. Perfusion 2011, 27, 21–29. [CrossRef]

- Chao, K.-P.; Huang, C.-S.; Wei, C.-Y. Health risk assessments of DEHP released from chemical protective gloves. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 283, 53–59. [CrossRef]

- Demirel, A.; Çoban, A.; Yıldırım, .; Doğan, C.; Sancı, R.; İnce, Z. Hidden Toxicity in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: Phthalate Exposure in Very Low Birth Weight Infants. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2016, 8, 298–304. [CrossRef]

- Rose, R.J.; Priston, M.J.; Rigby-Jones, A.E.; Sneyd, J.R. The effect of temperature on di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate leaching from PVC infusion sets exposed to lipid emulsions. Anaesthesia 2012, 67, 514–520. [CrossRef]

- Aubuchon, J.P., T.N. Estep, and R.J. Davey, The effect of the plasticizer di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate on the survival of stored rbcs. Blood, 1988. 71(2): p. 448-452. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Wu, K.-H. Low-level plasticizer exposure and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in the general population. Environ. Heal. 2022, 21, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.X., et al., Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) exposure induces sperm quality and functional defects in mice. Chemosphere, 2023. 312. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y., et al., Mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate Promotes Dengue Virus Infection by Decreasing IL-23-Mediated Antiviral Responses. Frontiers in Immunology, 2021. 12. [CrossRef]

- Garmaroudi, F.S.; Marchant, D.; Hendry, R.; Luo, H.; Yang, D.; Ye, X.; Shi, J.; McManus, B.M. Coxsackievirus B3 Replication and Pathogenesis. Futur. Microbiol. 2015, 10, 629–653. [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.; Pirruccello, S.; Lane, P.H.; Reyna, S.M.; Gauntt, C.J.; Höfling, K. Group B coxsackievirus myocarditis and pancreatitis: Connection between viral virulence phenotypes in mice. J. Med Virol. 2000, 62, 70–81. [CrossRef]

- Sin, J.; Mangale, V.; Thienphrapa, W.; Gottlieb, R.A.; Feuer, R. Recent progress in understanding coxsackievirus replication, dissemination, and pathogenesis. Virology 2015, 484, 288–304. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-L.; Lin, S.-Y.; Lee, C.-N.; Shih, J.-C.; Cheng, A.-L.; Chen, S.-H.; Chang, L.-Y.; Fang, C.-T. Serostatus of echovirus 11, coxsackievirus B3 and enterovirus D68 in cord blood: The implication of severe newborn enterovirus infection. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2023, 56, 766–771. [CrossRef]

- McManus, B.M., et al., Genetic determinants of coxsackievirus B3 pathogenesis, in Microarrays, Immune Responses and Vaccines, L. Aujame, et al., Editors. 2002. p. 169-179. [CrossRef]

- Drescher, K.M. and S.M. Tracy, The CVB and etiology of type 1 diabetes, in Group B Coxsackieviruses, S. Tracy, M.S. Oberste, and K.M. Drescher, Editors. 2008. p. 259-274. [CrossRef]

- Ianzini, F.; Bertoldo, A.; A Kosmacek, E.; Phillips, S.L.; A Mackey, M. Lack of p53 function promotes radiation-induced mitotic catastrophe in mouse embryonic fibroblast cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2006, 6, 11–11. [CrossRef]

- Lippmann, E.S.; Azarin, S.M.; Kay, J.E.; Nessler, R.A.; Wilson, H.K.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Palecek, S.P.; Shusta, E.V. Derivation of blood-brain barrier endothelial cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 783–791. [CrossRef]

- Espinal, E.R., S.J. Sharp, and B.J. Kim, Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-Derived Endothelial Cells to Study Bacterial–Brain Endothelial Cell Interactions, in The Blood-Brain Barrier: Methods and Protocols, N. Stone, Editor. 2022, Springer US: New York, NY. p. 73-101. [CrossRef]

- Lippmann, E.S.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Azarin, S.M.; Palecek, S.P.; Shusta, E.V. A retinoic acid-enhanced, multicellular human blood-brain barrier model derived from stem cell sources. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4160. [CrossRef]

- Slifka, M.K.; Pagarigan, R.; Mena, I.; Feuer, R.; Whitton, J.L. Using Recombinant Coxsackievirus B3 To Evaluate the Induction and Protective Efficacy of CD8+T Cells during Picornavirus Infection. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 2377–2387. [CrossRef]

- Gillum, N.; Karabekian, Z.; Swift, L.M.; Brown, R.P.; Kay, M.W.; Sarvazyan, N. Clinically relevant concentrations of di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) uncouple cardiac syncytium. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009, 236, 25–38. [CrossRef]

- Posnack, N.G.; Lee, N.H.; Brown, R.; Sarvazyan, N. Gene expression profiling of DEHP-treated cardiomyocytes reveals potential causes of phthalate arrhythmogenicity. Toxicology 2011, 279, 54–64. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.W.; Hancock, T.J.; Dogra, P.; Patel, R.; Arav-Boger, R.; Williams, A.D.; Kennel, S.J.; Wall, J.S.; Sparer, T.E. Anticytomegalovirus Peptides Point to New Insights for CMV Entry Mechanisms and the Limitations of In Vitro Screenings. mSphere 2019, 4, e00586-18. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J., et al., Modeling Group B Streptococcus and Blood-Brain Barrier Interaction by Using Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Brain Endothelial Cells. mSphere, 2017. 2(6). [CrossRef]

- Vollmuth, N., et al., Group B Streptococcus transcriptome when interacting with brain endothelial cells. Journal of Bacteriology, 2024. 206(6). [CrossRef]

- Espinal, E.R.; Matthews, T.; Holder, B.M.; Bee, O.B.; Humber, G.M.; Brook, C.E.; Divyapicigil, M.; Sharp, J.; Kim, B.J. Group B Streptococcus-Induced Macropinocytosis Contributes to Bacterial Invasion of Brain Endothelial Cells. Pathogens 2022, 11, 474. [CrossRef]

- Mamana, J.; Humber, G.M.; Espinal, E.R.; Seo, S.; Vollmuth, N.; Sin, J.; Kim, B.J. Coxsackievirus B3 infects and disrupts human induced-pluripotent stem cell derived brain-like endothelial cells. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Müller, U.; Steinhoff, U.; Reis, L.F.L.; Hemmi, S.; Pavlovic, J.; Zinkernagel, R.M.; Aguet, M. Functional Role of Type I and Type II Interferons in Antiviral Defense. Science 1994, 264, 1918–1921. [CrossRef]

- Takaoka, A.; Yanai, H. Interferon signalling network in innate defence. Cell. Microbiol. 2006, 8, 907–922. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.A. and M.L. Lloyd, A Review of Murine Cytomegalovirus as a Model for Human Cytomegalovirus Disease-Do Mice Lie? Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 22(1). [CrossRef]

- Roback, J.D.; Su, L.; Newman, J.L.; Saakadze, N.; Lezhava, L.J.; Hillyer, C.D. Transfusion-transmitted cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections in a murine model: characterization of CMV-infected donor mice. Transfusion 2006, 46, 889–895. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.C., Interstitial pneumonia and sub-clinical infection after intranasal inoculation of murine cytomegalovirus. Infection and Immunity, 1978. 21(1): p. 275-280. [CrossRef]

- Brizić, I.; Lisnić, B.; Brune, W.; Hengel, H.; Jonjić, S. Cytomegalovirus Infection: Mouse Model. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2018, 122, e51. [CrossRef]

- Brigtsen, A.K.; Jacobsen, A.F.; Dedi, L.; Melby, K.K.; Espeland, C.N.; Fugelseth, D.; Whitelaw, A. Group B Streptococcus colonization at delivery is associated with maternal peripartum infection. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0264309. [CrossRef]

- Tavares, T.; Pinho, L.; Andrade, E.B. Group B Streptococcal Neonatal Meningitis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 35, e0007921. [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J.; Grabiec, U.; Falk, K.; Dehghani, F.; Schaedlich, K. The endocrine disruptor DEHP and the ECS: analysis of a possible crosstalk. Endocr. Connect. 2020, 9, 101–110. [CrossRef]

- Heudorf, U.; Mersch-Sundermann, V.; Angerer, J. Phthalates: Toxicology and exposure. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Heal. 2007, 210, 623–634. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Peng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Song, P.; Zhou, J.; Ma, K.; Yu, Y.; Dong, Q. Exposure to di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) increases the risk of cancer. BMC Public Heal. 2024, 24, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lyu, L.; Tao, Y.; Ju, H.; Chen, J. Health risks of phthalates: A review of immunotoxicity. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120173. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., et al., DEHP induces immunosuppression through disturbing inflammatory factors and CYPs system homeostasis in common carp neutrophils. Fish Shellfish Immunol, 2020. 96: p. 26-31. [CrossRef]

- Narayana, S.K., et al., The Interferon-induced Transmembrane Proteins, IFITM1, IFITM2, and IFITM3 Inhibit Hepatitis C Virus Entry. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2015. 290(43): p. 25946-25959. [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, S., et al., A Role for IFITM Proteins in Restriction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. Cell Reports, 2015. 13(5): p. 874-883. [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Schwartz, O.; Compton, A.A. More than meets the I: the diverse antiviral and cellular functions of interferon-induced transmembrane proteins. Retrovirology 2017, 14, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Kemball, C.C.; Alirezaei, M.; Flynn, C.T.; Wood, M.R.; Harkins, S.; Kiosses, W.B.; Whitton, J.L. Coxsackievirus Infection Induces Autophagy-Like Vesicles and Megaphagosomes in Pancreatic Acinar Cells In Vivo. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 12110–12124. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.M.; Tsueng, G.; Sin, J.; Mangale, V.; Rahawi, S.; McIntyre, L.L.; Williams, W.; Kha, N.; Cruz, C.; Hancock, B.M.; et al. Coxsackievirus B Exits the Host Cell in Shed Microvesicles Displaying Autophagosomal Markers. PLOS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004045. [CrossRef]

- Sin, J.; McIntyre, L.; Stotland, A.; Feuer, R.; Gottlieb, R.A. Coxsackievirus B Escapes the Infected Cell in Ejected Mitophagosomes. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01347-17. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Du, W.; Hagemeijer, M.C.; Takvorian, P.M.; Pau, C.; Cali, A.; Brantner, C.A.; Stempinski, E.S.; Connelly, P.S.; Ma, H.-C.; et al. Phosphatidylserine vesicles enable efficient en bloc transmission of enteroviruses. Cell 2015, 160, 619–630. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-L.; Weng, S.-F.; Kuo, C.-H.; Ho, H.-Y. Enterovirus 71 Induces Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Generation That is Required for Efficient Replication. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e113234–e113234. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-L.; Wu, C.-H.; Chien, K.-Y.; Lai, C.-H.; Li, G.-J.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Lin, G.; Ho, H.-Y. Enteroviral 2B Interacts with VDAC3 to Regulate Reactive Oxygen Species Generation That Is Essential to Viral Replication. Viruses 2022, 14, 1717. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, A.; Guan, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Song, H.; et al. TBK1-Mediated DRP1 Targeting Confers Nucleic Acid Sensing to Reprogram Mitochondrial Dynamics and Physiology. Mol. Cell 2020, 80, 810–827.e7. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Won, J.-H.; Hwang, I.; Hong, S.; Lee, H.K.; Yu, J.-W. Defective mitochondrial fission augments NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15489. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Kordbacheh, R.; Sin, J. Extracellular Vesicles: A Novel Mode of Viral Propagation Exploited by Enveloped and Non-Enveloped Viruses. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 274. [CrossRef]

- Sawaged, S.; Mota, T.; Piplani, H.; Thakur, R.; Lall, D.; McCabe, E.; Seo, S.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Feuer, R.; Gottlieb, R.A.; et al. TBK1 and GABARAP family members suppress Coxsackievirus B infection by limiting viral production and promoting autophagic degradation of viral extracellular vesicles. PLOS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010350. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).