1. Introduction

Since the Wenchuan earthquake in 2008, seismic protection measures for structures have gradually shifted from the traditional seismic design of “using rigidity to overcome rigidity” to the seismic isolation design of “using flexibility to overcome rigidity.” The theoretical goal of seismic design in Chinese bridge engineering has evolved from conventional seismic design to seismic isolation design, as well as enhancing the resilience of post-earthquake structures [

1,

2,

3].

In recent years, theoretical, numerical simulation, and experimental research on bridge seismic isolation design have been conducted by many scholars. For example, in terms of theoretical research, Liu et al. [

4] summarized the nonlinear quasi-zero stiffness theory for the design of seismic isolation devices for structures. Wakjira et al. [

5] developed performance-based seismic design theory for predicting drift ratio limit states of UHPC bridge columns. In terms of numerical simulation, Guo et al. [

6] proposed a novel socket self-centering bridge pier with a hybrid energy dissipation system and evaluated the seismic response through the finite element method. Gao et al. [

7] designed a new bi-directional seismic protection device for bridge engineering and simulated the mechanical behavior of the device during real earthquake conditions using numerical simulation. Nagarajaiah et al. [

8] presented an analytical model and a solution algorithm developed for nonlinear dynamic analysis of three-dimensional base-isolated structures with elastomeric and/or sliding isolation systems. In terms of experimental research, Wang et al. [

9] proposed a gap SMA-NSD-FPB isolation bearing and analyzed its isolation performance through experiments. Lei et al. [

10] established a new seismic damping system using viscous dampers for cross-sea cable-stayed bridges in deep water environments and designed experiments to verify the reliability of the seismic isolation effect. So far, seismic isolation devices have played an important role in enhancing wind and earthquake resistance in bridge structures.

In most cases, passive isolation control methods are commonly used for the seismic isolation design of structures [

11,

12,

13]. From the above research, it can be seen that the optimal isolation effect of isolation devices is closely related to the mass, geometric dimensions, dynamic characteristics, site environment, and external load characteristics of the isolated object [

14,

15,

16,

17]. To achieve the best isolation effect for different isolated objects and seismic loads, it is necessary to design isolation devices with varying performance parameters. Therefore, for passive seismic isolation devices, due to their non-adjustable performance parameters, it is challenging to achieve a good seismic isolation effect for structures under random and variable seismic loads in the wide frequency range of 0 Hz to 20 Hz [

18,

19,

20].

In response to the issues mentioned above, a fuzzy optimization model for a new three-dimensional seismic isolation bearing used in bridge engineering was established, and the corresponding relationship between optimal seismic isolation performance and the coupling effect of design parameters was studied. Firstly, the shape and parameters to be optimized for the three-dimensional seismic isolation bearing were determined through a topology optimization method. Subsequently, a quantitative function was established with the optimization objective of minimizing the acceleration transfer rate. Then, the sensitivity of the design parameters of the seismic isolation bearing was analyzed using the optimization center gradient method, and an improved genetic algorithm was employed to quickly optimize and obtain the optimal design parameters. Finally, the effectiveness of the three-dimensional seismic isolation bearing was validated through experiments.

2. Design Principles

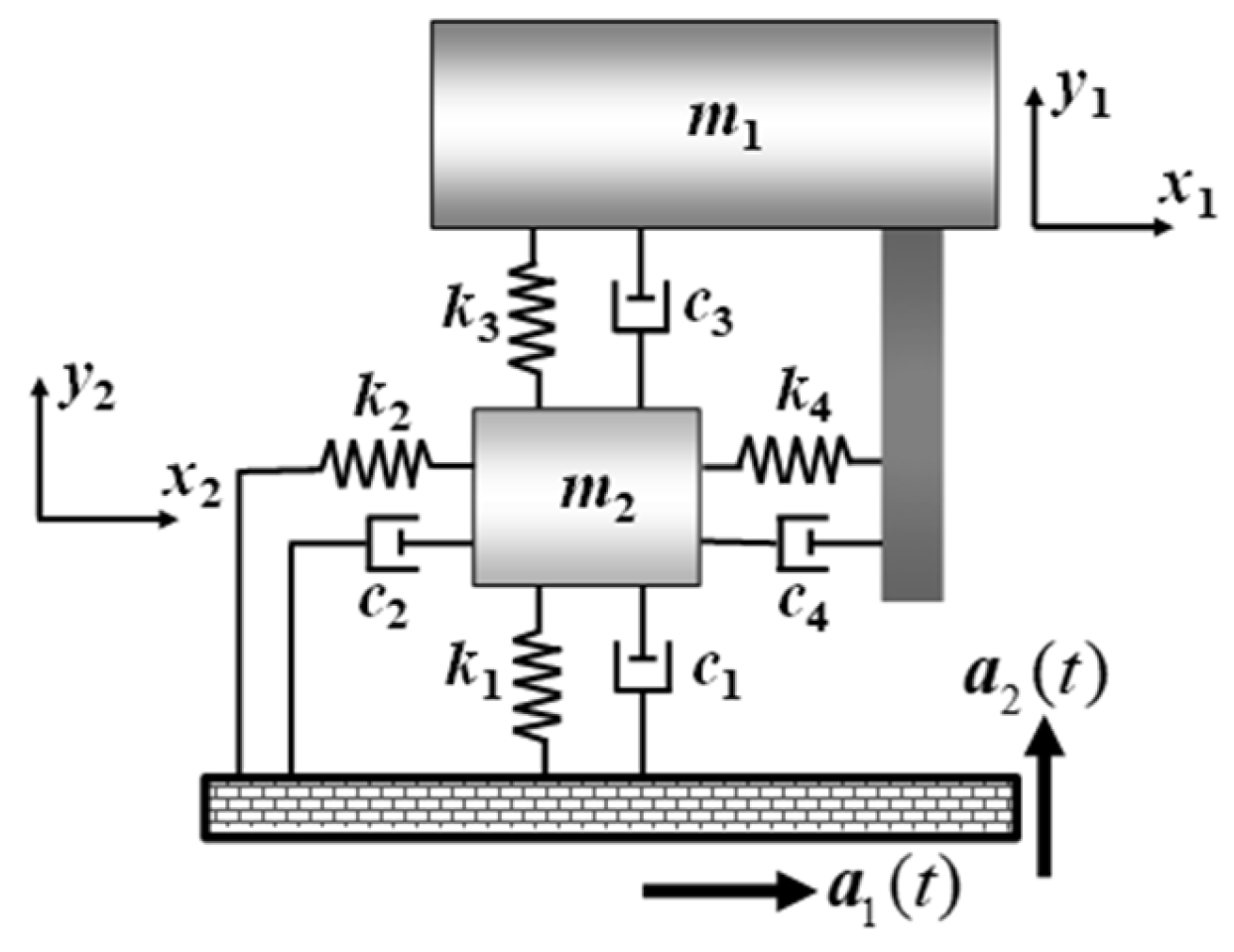

2.1. Mechanical Model of the Three-Dimensional Seismic Isolation Device

The three-dimensional seismic isolation system includes horizontal bidirectional and vertical isolation. In the design of the isolation device, a symmetric design is considered for the horizontal bidirectional aspect; therefore, the mechanical model of the three-dimensional seismic isolation device is simplified to a unidirectional horizontal and vertical model, as shown in

Figure 1.

In this mechanical model, m1 represents the mass of the isolated object, while m2 denotes the mass of the three-dimensional seismic isolation device. The parameters k1 and k2, as well as c1 and c2, reflect the stiffness and damping characteristics of the isolation device coupled with the lower load-bearing structure in the vertical and horizontal directions, respectively. Similarly, k3 and k4, along with c3 and c4, represent the stiffness and damping characteristics of the isolation device coupled with the upper isolated object in the vertical and horizontal directions.

The degrees of freedom of the isolated object in the horizontal and vertical directions are denoted by

x1 and

y1, respectively, while the degrees of freedom of the three-dimensional seismic isolation device in the horizontal and vertical directions are represented by

x2 and

y2. The motion differential equations are listed as shown in Equation (1).

The dynamic response at any given time can be calculated using the Newmark method based on Equation (1).

2.2. Topology Optimization Model of the Three-Dimensional Seismic Isolation Device.

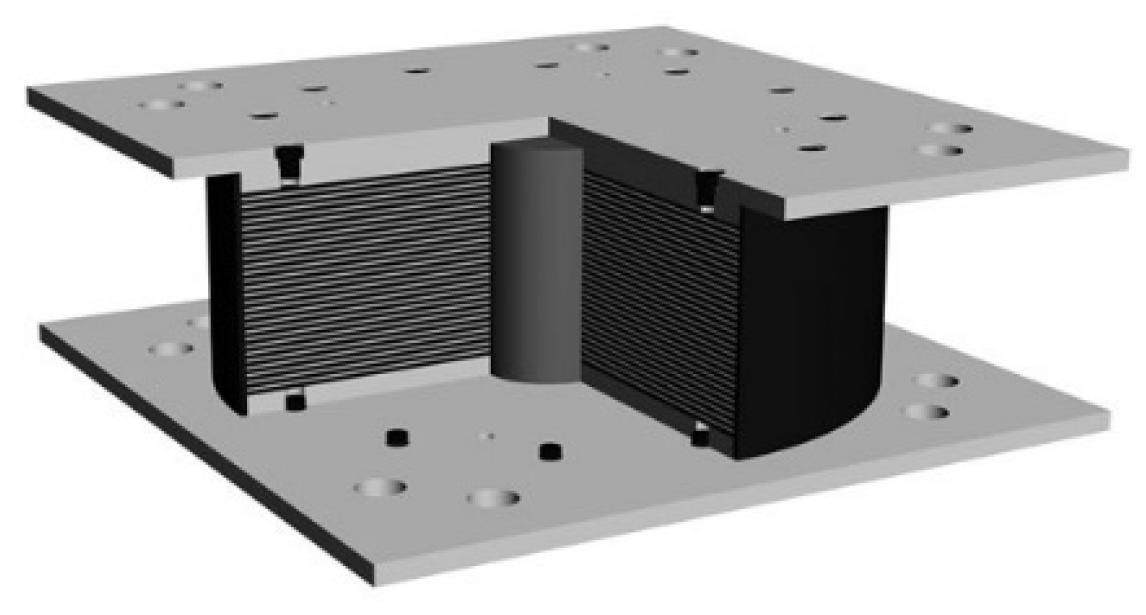

Passive seismic isolation devices include various types such as groove track isolation devices, ball-type isolation devices, sliding rail isolation devices, spherical track isolation devices, load-bearing isolation devices, and combined rubber isolation devices [

21]. The lead-core rubber seismic isolation bearings are commonly used in bridge engineering [

22], as shown in

Figure 2.

Based on existing rubber seismic isolation bearings, a new type of three-dimensional seismic isolation bearing with adjustable stiffness and improved isolation performance is proposed.

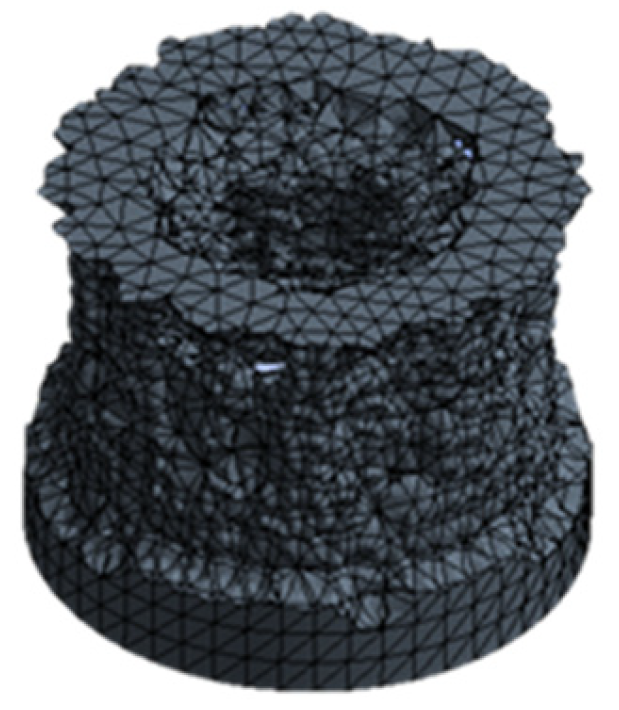

Firstly, the topology optimization model of the rubber seismic isolation bearing under specified working conditions is obtained using the Evolutionary Structural Optimization (ESO) method [

23]. The fundamental idea is to use stress as the optimization criterion: under loading conditions, the lowest 1% of stressed elements are removed; then, the structure is reloaded, causing a redistribution of stress, and the process continues by removing the lowest 1% of stressed elements repeatedly until the total number of removed elements reaches a predetermined ratio. The initial topological shape of the rubber seismic isolation bearing is designed as a cylinder, and its topology is optimized under compressive shear loads.

When the element removal rate reaches 85%, the topology optimization result is shown in

Figure 3.

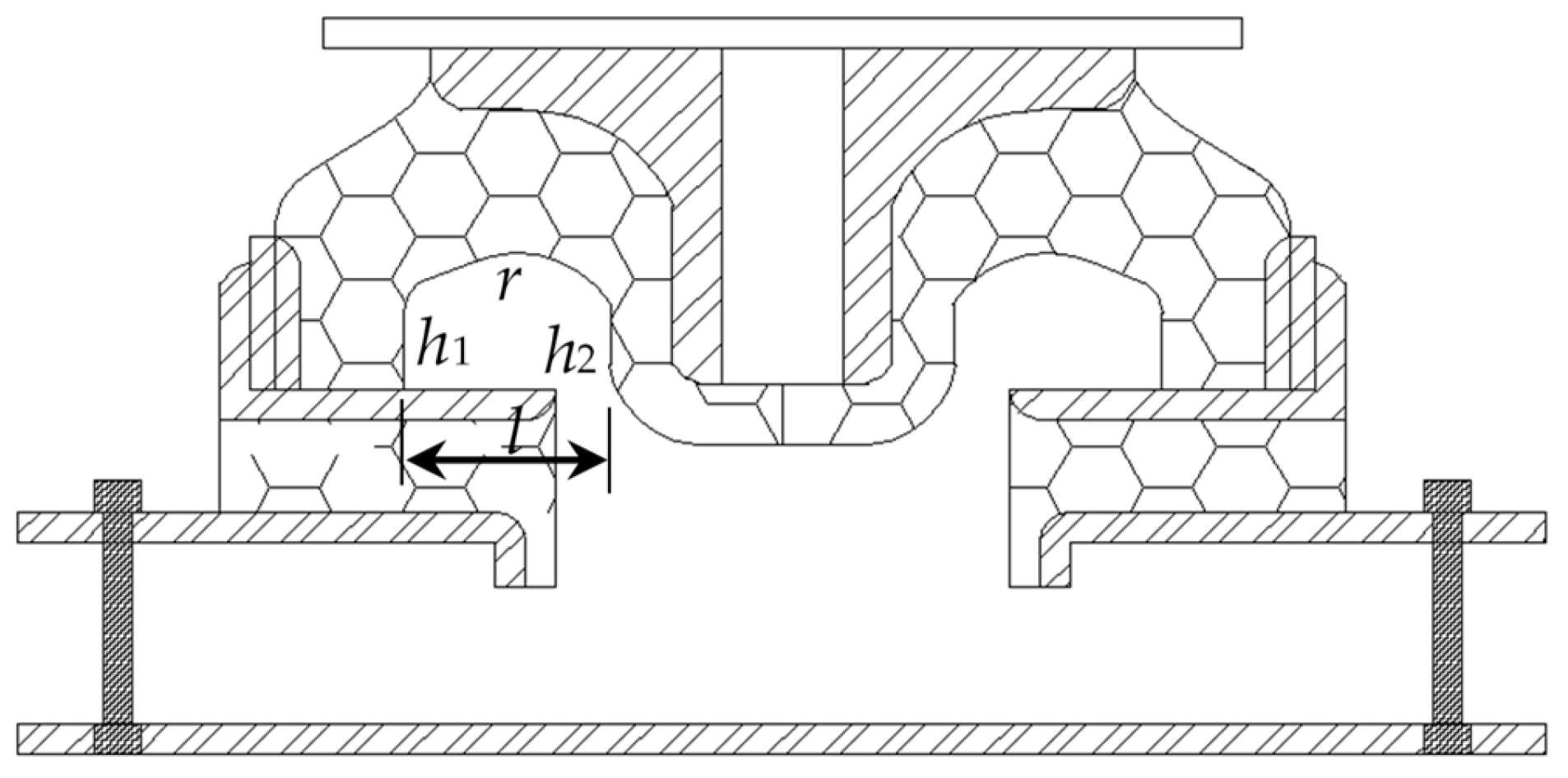

The topology optimization model obtained from

Figure 3 is then converted into a parametric three-dimensional seismic isolation bearing, with hollow cross-sectional dimensions

h1,

h2,

l and

r as the parameters to be optimized, as illustrated in

Figure 4. Subsequently, optimization methods will be employed to obtain the optimal parameters that enable the rubber seismic isolation bearing to achieve the best seismic isolation performance.

3. Multi-Parameter Optimization and Sensitivity Analysis Method

3.1. Mathematical Model for Multi-Parameter Optimization of the Three-Dimensional Seismic Isolation Device

The objective of parameter optimization for the seismic isolation device is to find a set of solutions that provide an overall optimal isolation effect against a series of vibrational loads.

According to Fourier series, any load can be decomposed into a linear combination of several harmonic loads. For a seismic design intensity of 8 degrees, the peak acceleration value of the designed harmonic vibrational load is set at 0.20g, with design load frequencies

ω ranging from 1 Hz to 20 Hz, resulting in 20 sets of harmonic loads (independently applied in the horizontal and vertical directions), expressed as:

Under the

i-th load set, the acceleration response at the top center node of the isolated object is calculated as

. The acceleration transmission ratio of the isolated object at any given moment is defined as:

Thus, the mathematical model for this problem is to find a set of design parameters such that the following objective function is satisfied:

where

W(

X) represents the objective function, and

X denotes the discrete design variables.

The physical significance of this objective function is that when the design load frequencies are taken as specified, the acceleration transmission ratio of the isolated object can be obtained at any moment, leading to the determination of the maximum acceleration transmission ratio . The objective function seeks to find the optimal set of parameter solutions X* that minimizes the maximum acceleration transmission ratio corresponding to the 20 different load frequencies under their respective working conditions.

3.2. Multi-Parameter Identification Based on Improved Genetic Algorithm

Genetic algorithms are intelligent optimization algorithms known for their strong global search capabilities and high computational efficiency, making them particularly advantageous for solving unimodal optimization problems. However, directly applying the basic genetic algorithm to solve multimodal optimization problems can lead to convergence at local optima (a phenomenon known as “premature convergence”), making it difficult to achieve global optima [

24]. Since the optimization of design parameters for the three-dimensional seismic isolation device may be a multimodal optimization problem, it is necessary to improve the basic genetic algorithm to address its shortcomings.

The operational process of the basic genetic algorithm includes the following steps:

Step 1: Variable Encoding: The commonly used binary encoding method represents variable

xi as

blbl-1…

b2b1 (where

bi = 0 or 1), with its corresponding value given by:

Step 2: Population Initialization: The population of the t-th generation is denoted as P(t). All individuals in the initial population P(0) are randomly generated.

Step 3: Fitness Calculation: The fitness of each individual in the population

P(

t) is calculated to determine the probability of its genetic contribution to the next generation. Since this problem is a minimization problem, the relationship between the fitness function

F(

X) and the objective function

W(

X) is established as:

Step 4: Selection and Genetic Operations: Selection is performed based on the proportion of individual fitness within the overall fitness (using a roulette wheel method), followed by crossover and mutation operations according to preset probabilities to obtain the next generation population P(t+1).

Step 5: Steps 3 and 4 are repeated iteratively until t exceeds the preset maximum number of generations T.

To improve optimization efficiency and overcome the “premature convergence” issue of the basic genetic algorithm, the following enhancements are proposed:

(1) Establishment of a small habitat algorithm with fusion mechanism:

After each generation of evolution, implement a “last position replacement” mechanism within each small habitat, eliminating the worst individual of that generation while ensuring that the best individual from the previous generation automatically enters this generation. This ensures that the optimal individual in the next generation is not worse than that of the previous generation, allowing the genetic algorithm to continuously evolve towards optimality without regressing.

Implement an “inter-habitat exchange” mechanism, where the second-worst individual in the i-th small habitat is eliminated, and the best individual from the (i-1)-th small habitat automatically enters the i-th small habitat. This increases population diversity and reduces the probability of the genetic algorithm converging to local optima.

(2) Establishment of a method for identifying global optima in multimodal problems:

Let Ai be the peak point to which the i-th small habitat converges after evolution (with an objective function value of Fi and corresponding variables Xi).

When there are sufficiently many small habitats, the point with the maximum objective function value is likely to be the global optimum, denoted as A*, with an objective function value of F* and corresponding variables X*.

By comparing each peak point

Ai with

A*, if

Fi is very close to

F* but

Xi differs significantly from

X*, then

Ai is considered another global optimum distinct from

A*:

where

α (0 <

α < 1) and

β are pre-defined constants.

3.3. Multi-Parameter Sensitivity Analysis Based on Optimized Central Gradient Method

Next, sensitivity analysis will be conducted on each parameter to determine how changes in each parameter affect the rate of change of the objective function. This provides a basis for fuzzy optimization design and stiffness adjustment, focusing on parameters with high sensitivity while applying fuzzy optimization to those with low sensitivity.

For the multi-parameter optimization problem of the three-dimensional seismic isolation device, each parameter is interrelated, and their relationship with the objective function is nonlinear. If traditional single-factor analysis methods are used, calculating the sensitivity of parameter xi generally yields different results when other parameters take different baseline values. Thus, evaluating the sensitivity of parameter xi loses significance.

Therefore, it is essential to use the optimal parameters (i.e., optimization center) as a baseline and apply single-factor analysis methods (i.e., gradient methods) to calculate the sensitivity of each parameter. The optimal parameters

X* have been obtained through genetic algorithm optimization. It has been found that the internal hollow dimensions of the three-dimensional rubber seismic isolation device significantly affect its vertical stiffness. Thus, using the vertical stiffness

KV of the isolation device as a sensitivity evaluation function allows for calculating the sensitivity value

f(

xi) of each parameter

xi using:

To adjust the stiffness of the three-dimensional seismic isolation device, it is sufficient to modify the values of design parameters with high sensitivity.

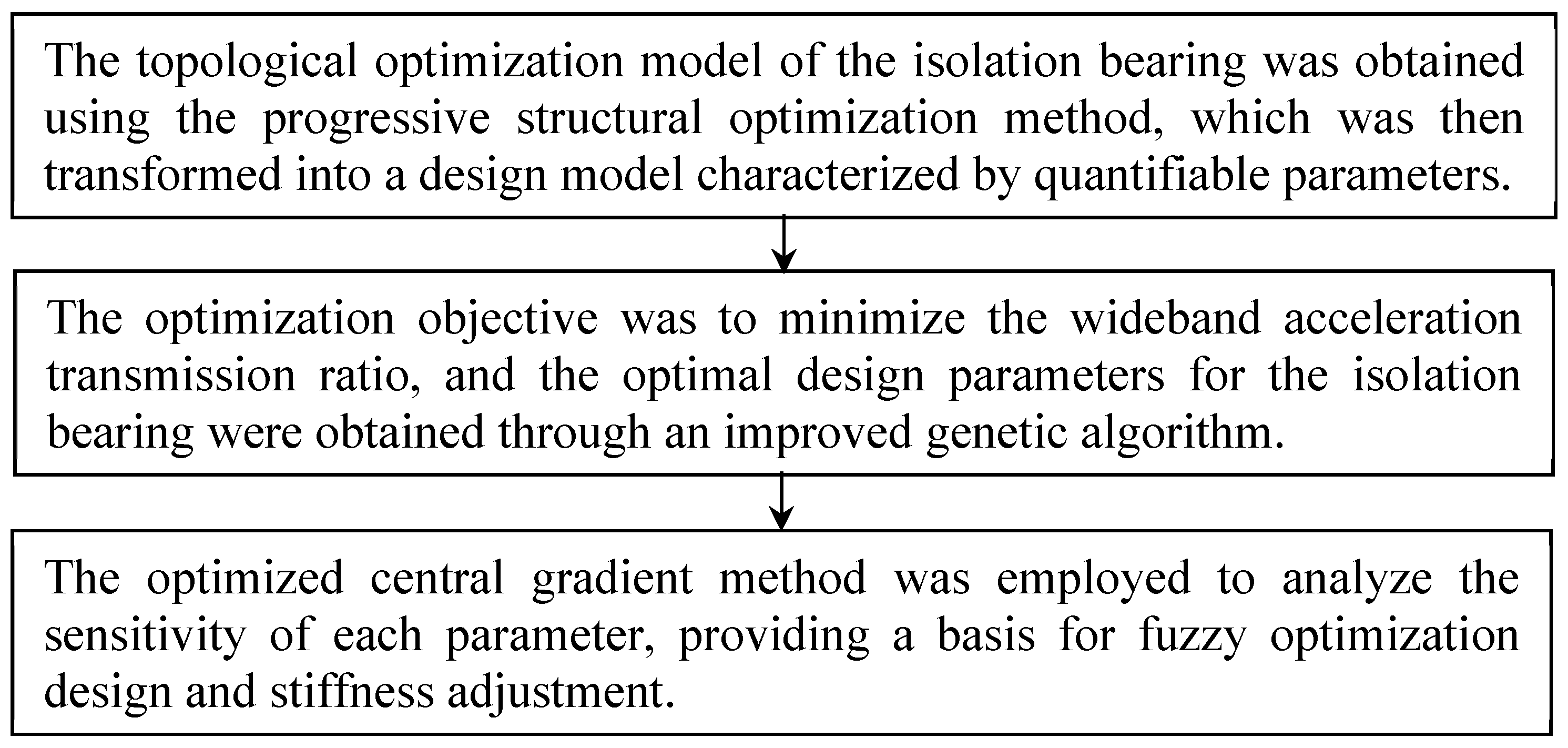

The flowchart for the initial design, multi-parameter optimization, and sensitivity analysis of the three-dimensional isolation device is shown in

Figure 5.

Based on the parameter sensitivity design method, the following fuzzy optimization design theory is established:

For design variables

xi with low sensitivity, let

, while maintaining the other variables at their optimal center values. If the following condition is satisfied:

where

W(

X) is the objective function as shown in Equation (4), then the design value of variable

xi can be freely chosen. This allows the isolation device to exhibit good versatility for different isolated objects, facilitating industrial processing.

4. Calculation Results and Experimental Validation

4.1. Optimal Solution Based on Improved Genetic Algorithm

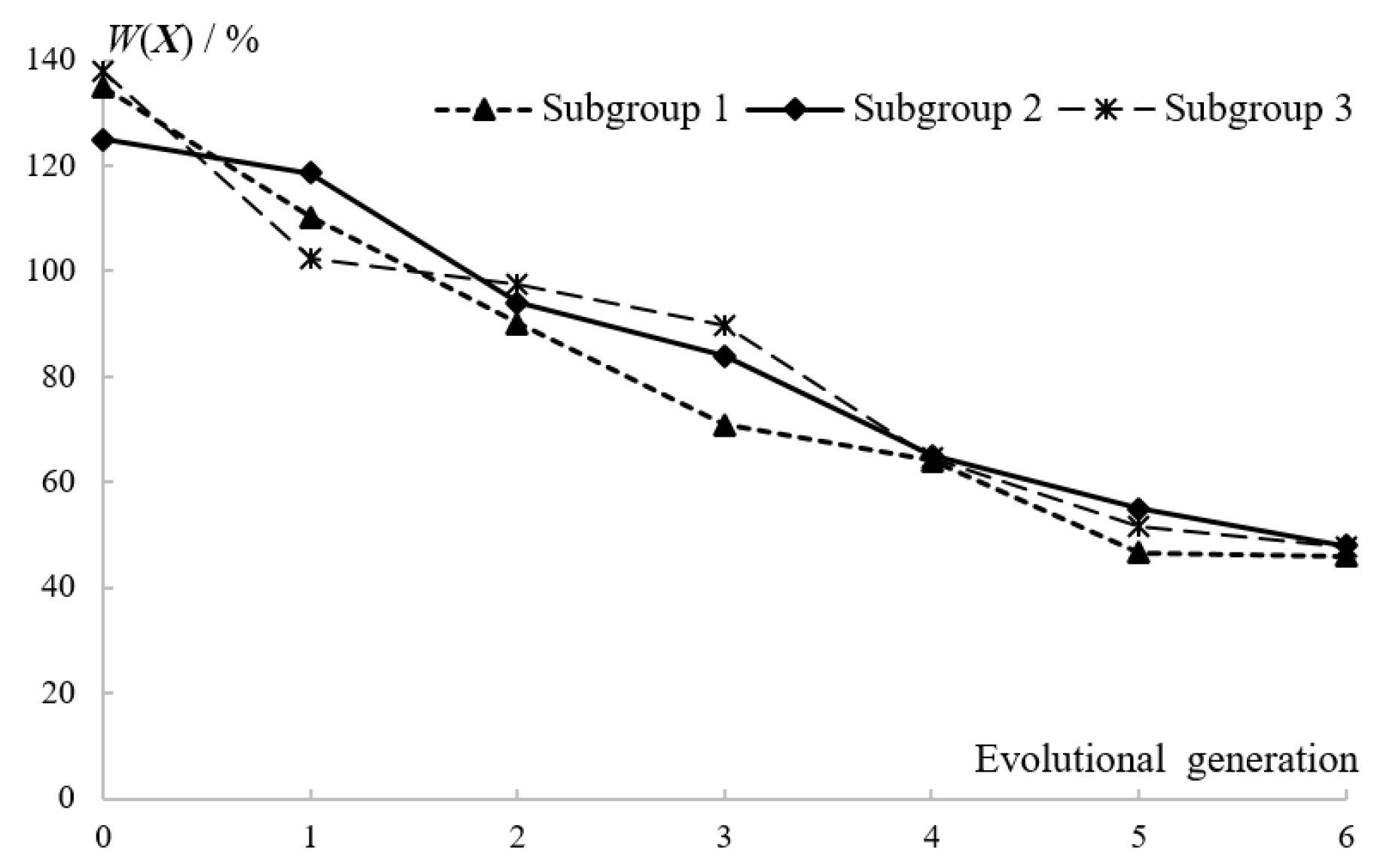

The mass of the isolated structure is set to 80 kg. The total width of the three-dimensional seismic isolation bearing is designed to be 150 mm, and the total height is 54 mm. The basic computational parameters for the genetic algorithm are set as follows: the number of small habitats is 5, the number of individuals in each population is 20, the crossover probability is 0.8, the mutation probability is 0.05, and the maximum number of generations is set to 6.

Through optimization using the improved genetic algorithm, after 6 generations of iteration, the maximum acceleration transmission ratio at the top center of the isolated structure was reduced from 138.1% to 46.0%. The optimal design parameters for the hollow cross-section of the three-dimensional seismic isolation bearing at this point are:

h1 = 10 mm,

h2 = 15 mm,

l = 24 mm and

r = 16 mm. The optimization iteration process of the genetic algorithm is shown in

Figure 6.

4.2. Sensitivity Calculation Results Based on Optimized Central Gradient Method

Using the optimal design parameters as the optimization center and the vertical stiffness

KV of the isolation bearing as the sensitivity evaluation function, the calculation results are shown in

Table 1.

From

Table 1, it can be observed that among the four design parameters of the three-dimensional seismic isolation bearing, their sensitivity ranks from high to low as follows:

l >

h1 >

h2 >

r. Specifically, vertical stiffness increases with an increase in

r, while it decreases with increases in

l,

h1, and

h2. Therefore, if adjustments to the vertical stiffness of the isolation bearing are required, it is advisable to first finely tune the parameter value of

l, followed by a broader adjustment of

l,

h1, and

h2.

4.3. Experimental Validation of Isolation Effect

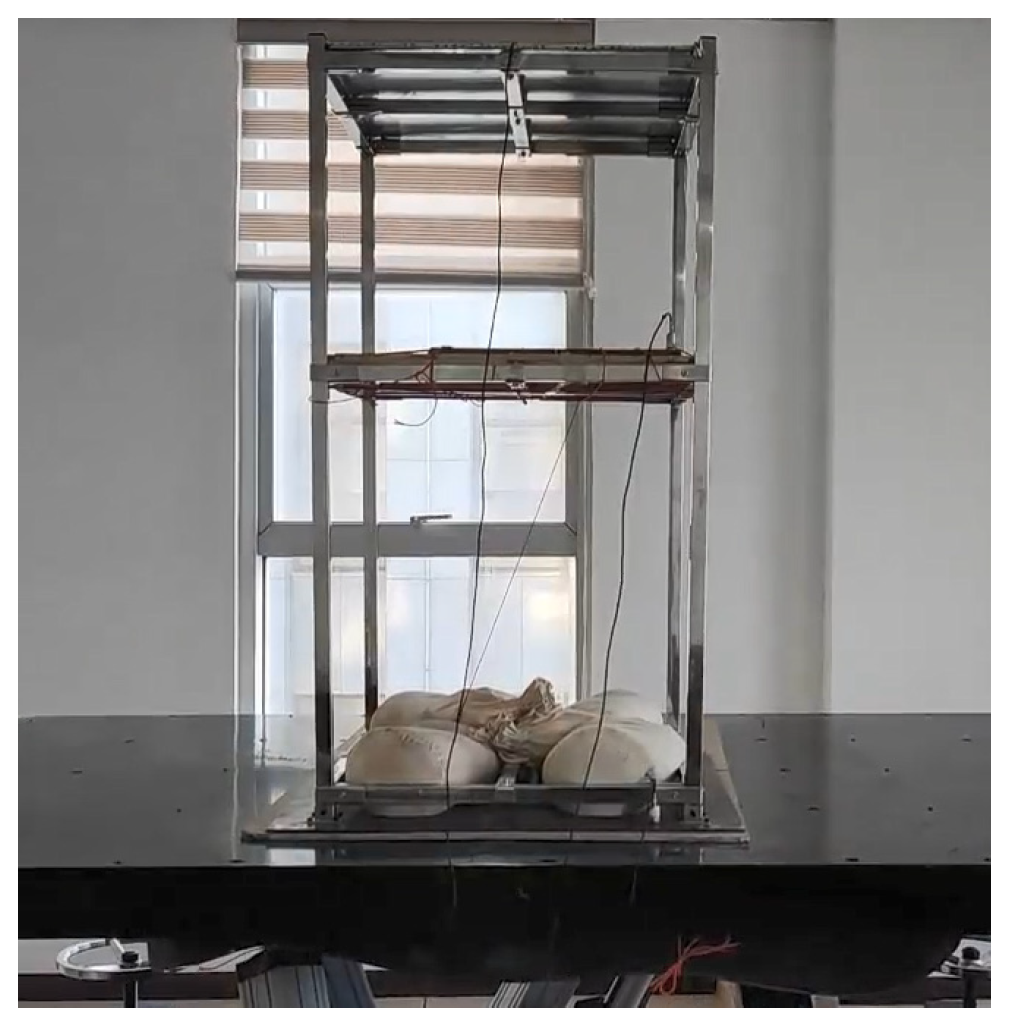

The isolation bearing processed based on optimized parameters is shown in

Figure 7.

The vibration table experiment for the structure equipped with isolation bearings is illustrated in

Figure 8.

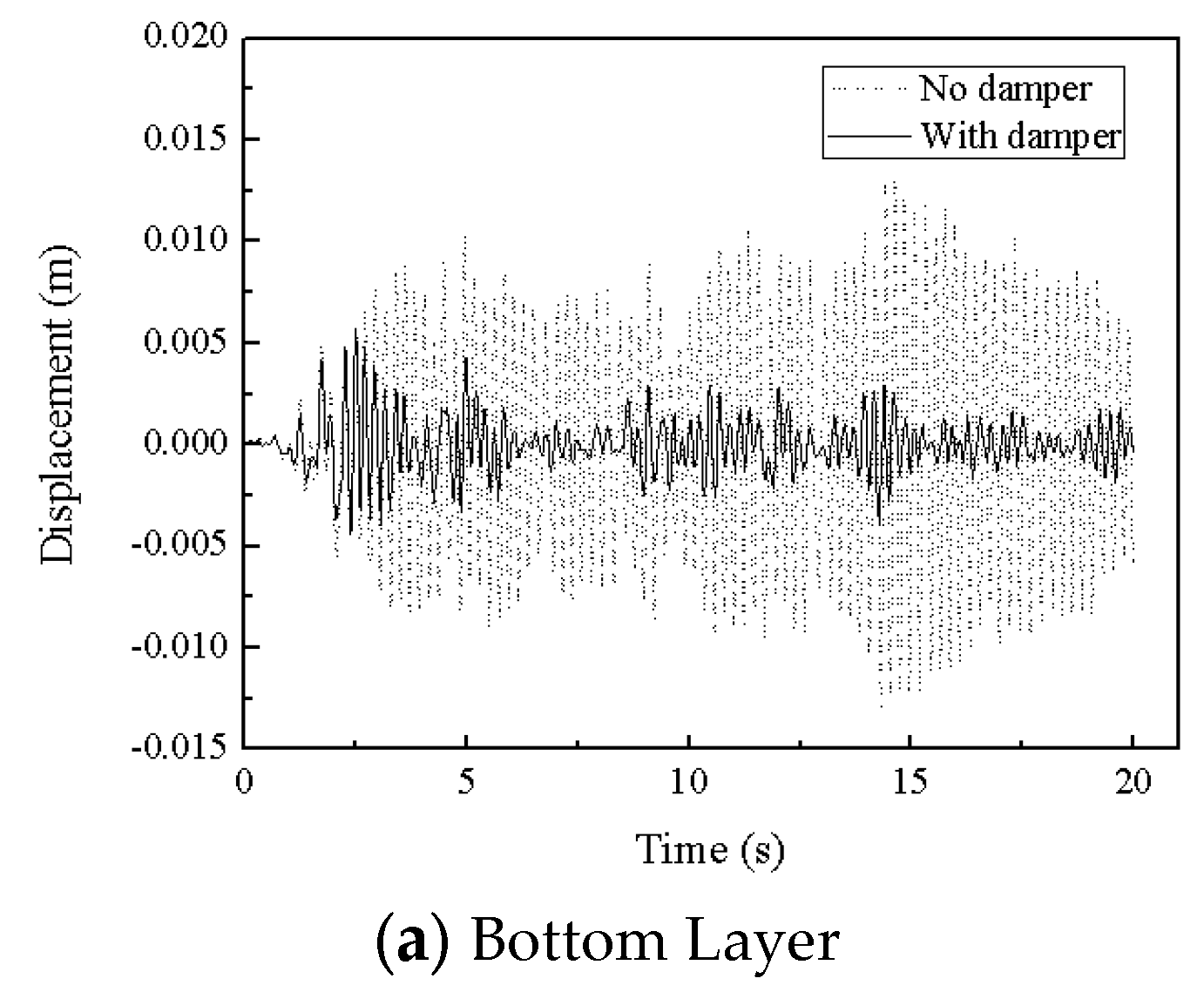

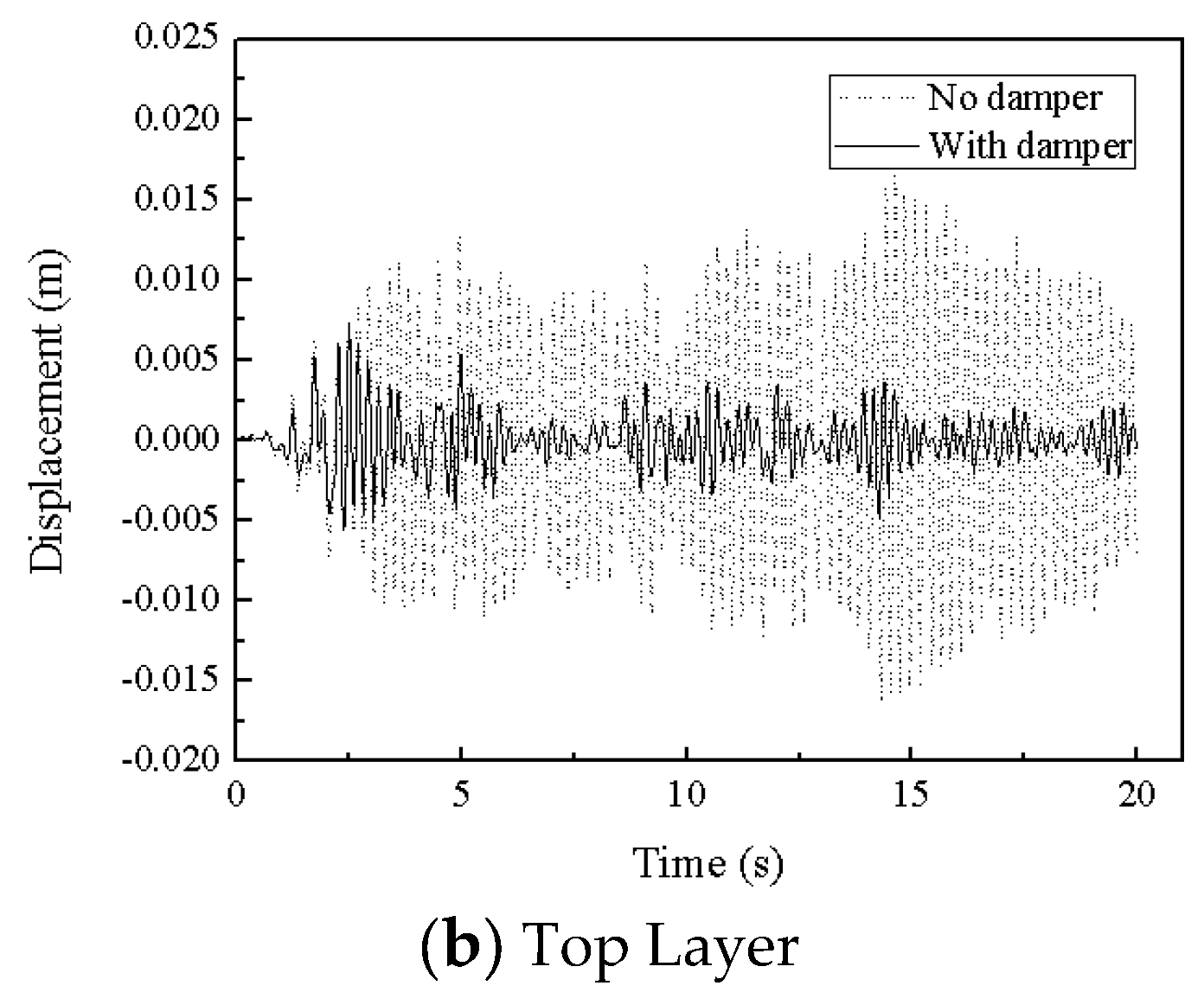

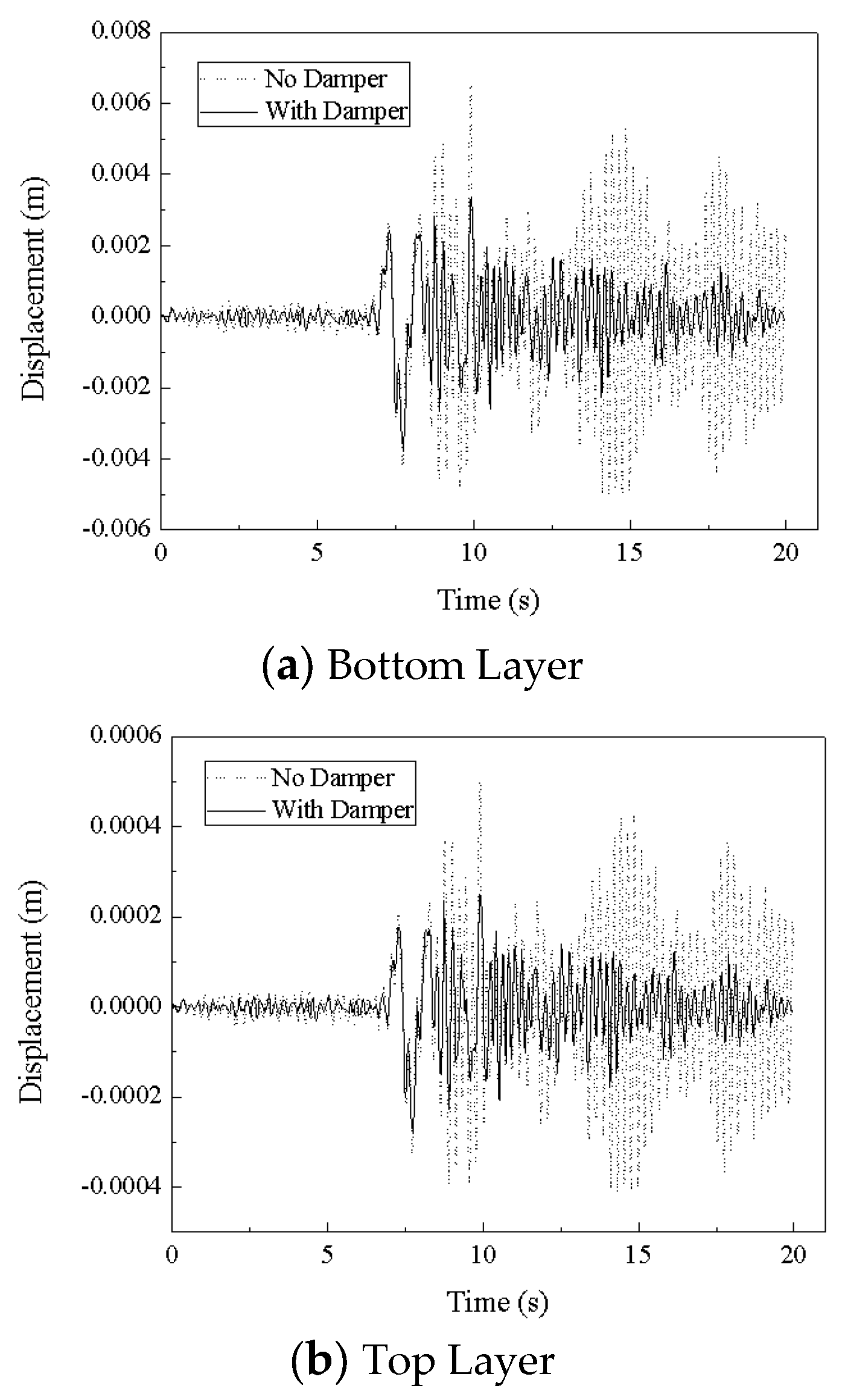

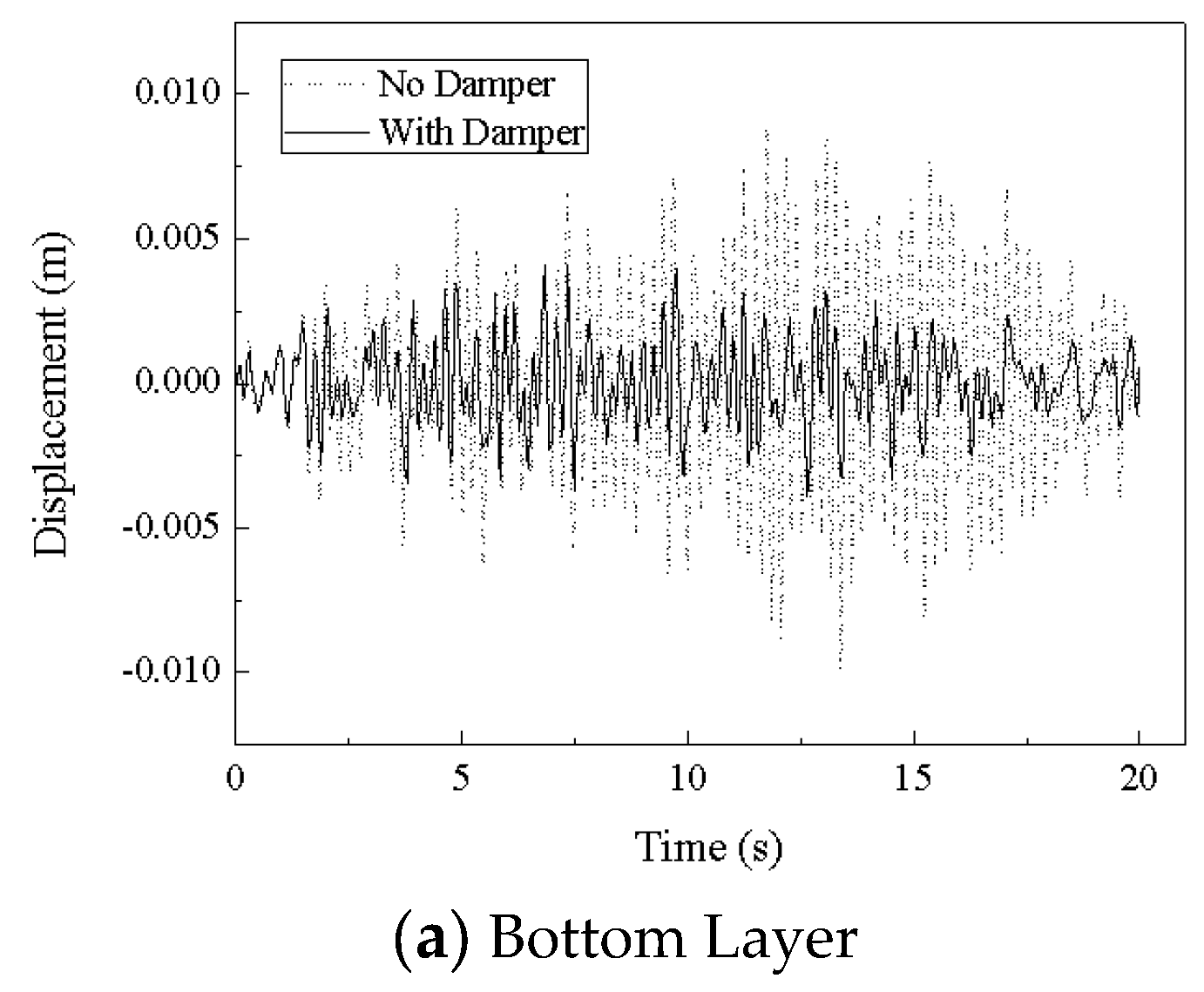

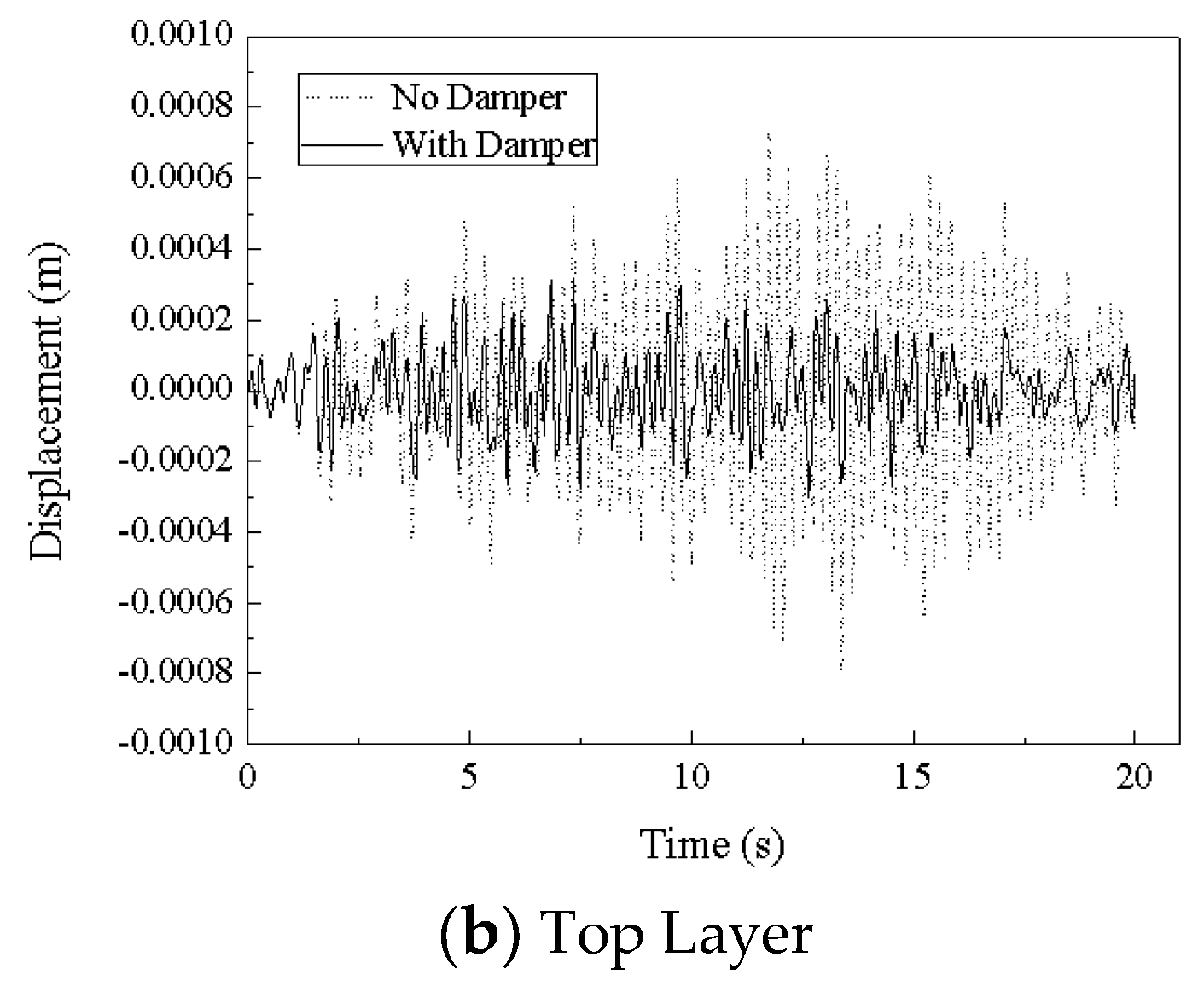

The isolation effect of the three-dimensional seismic isolation bearing was validated using EL-Centro wave, Tianjin wave, and Tangshan wave. The displacement time history curves for both cases—when isolation bearings are installed and when they are not—under these three seismic wave excitations are shown in

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11.

From

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, it can be seen that the maximum acceleration transmission ratios for the isolated structure under EL-Centro wave, Tianjin wave, and Tangshan wave are respectively 40.0%, 58.2%, and 41.1%, indicating that the three-dimensional seismic isolation bearing exhibits a good isolation effect.

To better illustrate the advantages of the optimization method proposed in this paper, a comparison with traditional design methods was conducted. Traditional design methods optimize bearing parameters based solely on a specific frequency external load. For instance, optimizing the design parameters of the isolation bearing solely for a harmonic load at a frequency of 3 Hz results in a maximum acceleration transmission ratio of 68.2% when subjected to EL-Centro seismic wave; a maximum ratio of 90.1% under Tianjin wave; and a maximum ratio of 69.4% under Tangshan wave. This indicates that traditional design methods have limited effectiveness against random loads.

According to Fourier series theory, random loads can be decomposed into a linear superposition of several harmonic loads, which cover loads ranging from 0 Hz to 20 Hz. The isolation bearing used in this example optimally considers a total of twenty sets of harmonic loads ranging from frequencies of 1 Hz to 20 Hz, with the optimization goal being to minimize the maximum acceleration transmission ratio at the top of the structure under independent action from these twenty sets of loads. Therefore, it demonstrates good performance against random seismic loads.

5. Conclusions

(1) By comprehensively considering multiple sets of harmonic loads covering frequencies from 0 Hz to 20 Hz, optimal performance parameters for the isolation bearing were designed to minimize the maximum acceleration transmission ratio for various working conditions of the isolated object. This design method ensures that the isolation bearing maintains good performance against real seismic waves.

(2) Through an improved genetic algorithm (which includes a small habitat algorithm with a fusion mechanism and a method for identifying global optima in multimodal problems), optimal performance parameters for the isolation bearing were obtained. Using these optimal parameters as a baseline, single-factor analysis methods (i.e., optimized central gradient methods) were employed to calculate sensitivities for each parameter, providing a basis for fuzzy optimization design and stiffness adjustment. During design, focus should be placed on parameters with high sensitivity while applying fuzzy optimization to those with low sensitivity, thereby providing theoretical support for unified customization and mass production in industrial applications.

(3) The multi-factor sensitivity analysis approach used in this study for designing novel isolation bearings is applicable not only to seismic design in bridges but also serves as a reference for parameter design in isolation bearings requiring medium to high precision in seismic performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S. and Z.Y.; methodology, Y.S. and Z.Y.; software, Y.M.; validation, Y.M.; formal analysis, Z.Y.; investigation, Y.S. and J.B.; resources, J.B.; data curation, Z.Y. and Y.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.S.; visualization, Y.M.; supervision, B.J.; project administration, B.J.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by General Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52278536 and General Project of the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province, grant number 2024NSFSC0428.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, J.Z.; Guan Z.G. Research progress on bridge seismic design: target from seismic alleviation to post-earthquake structural resilience. China J. Highw. Transp. 2017, 30, 1-9+59. (In Chinese).

- Banerjeet S.; Shinozuka M. Experimental verification of bridge seismic damage states quantified by calibrating analytical models with empirical field data. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2008, 7, 383-393.

- Zhang W.; Dong H.; Wen J.; et al. A resilience-based decision framework for post-earthquake restoration of bridge networks under uncertainty. Struct. Infrastruct. E. 2023.

- Liu, T.; Li A.Q. An overview of research on quasi-zero stiffness vibration isolation systems. J. S.-Cent. Univ. Natl. (Nat. Sci. Ed.). 2023, 53, 998-1012. (In Chinese).

- Wakjira T.G.; Alam M.S. Performance‐based seismic design of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete (UHPC) bridge columns with design example—Powered by explainable machine learning model. Eng. Strust. 2024, 314, 118346.

- Guo M.; Men J.; Fan D.S.Y. Seismic behavior and design method of socket self-centering bridge pier with hybrid energy dissipation system. Earthq. Struct. 2022, 23, 271-282.

- Gao H.; Yang J.; Wang J.J.; Yan H.Q. Experimental study on bi-directional seismic protection device for large and medium span bridges. J. Vib. Shock. 2022, 41, 112-118. (In Chinese).

- Nagarajaiah S.; Reinhorn A.M.; Constantinou M.C. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of three base isolated structures. J. Struct. Eng. 1991, 117, 2023-2054.

- Wang M.; Li C.T.; Tang Y.Q.; et al. Performance of gap SMA-NSD friction bearing in simply-supported bridge under near-field pulse ground motions. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vibrat. 2023, 43, 37-44. (In Chinese).

- Lei H.J.; Sun Y.K. Vibration control of sea-crossing cable-stayed bridge considering hydrodynamic force. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 19, 1936-1944. (In Chinese).

- Ren M.; He P.; Xie X.; et al. Active/passive vibration isolation with multi-axis transmission control: Analysis and experiment. J. Vib. Control, 2022, 5090-5106.

- Abdi M.S., Nekooei M., Jafari M.A. Seismic control of multi-degrees-of-freedom structures by vertical mass isolation method using MR dampers. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib., 2024, 23, 503-510. [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi A.; Nouri M.; Hoseinzadeh L.; et al. Hybrid vibration control of tall tubular structures via combining base isolation and mass damper systems optimized by enhanced special relativity search algorithm. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering, 2024, 48, 3373-3391. [CrossRef]

- Guo Q.; Zhou J.; Li M.T.G. Design and experimental study of a hybrid micro-vibration isolation system based on a strain sensor for high-precision space payloads. sensors, 2024, 24, 1649-1663.

- Jiang Y.; Ma Q. Isolation effect of double-layer wave impeding block on SV wave in unsaturated foundation. Mech. Solids, 2023, 58, 834–851.

- Qiang M.; Ye J. Isolation effect of P-wave by double-layer wave impeding barrier in unsaturated foundations. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dy., 2023, 23, 2350165.

- Li Z.; Naggar M.H.E.; Gong L.W. Seismic isolation effect of unconnected piles-caisson foundation: Large-scale shake table tests. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 176, 108304.

- Wang Z.; Zhang W.; Fang R.; et al. Development and experimental investigation of a novel self-centring friction rope device for continuous bridges. Eng. Struct. 2023, 1-19.

- Baig M.A.; Ansari I.; Islam N. Effect of material characteristics of lead rubber isolators on seismic performance of box girder bridge. J. Eng. App. Sci. 2024, 71. [CrossRef]

- Peng Y.; Yang J.; Pan G.; et al. Effects of fatigue characteristics on static and dynamic performance of eucommia rubber Isolators. J. App. Math. Phy., 2023, 11, 2165-2177.

- Warn G.P.; Ryan K.L. A review of seismic isolation for buildings: historical development and research needs. Buildings, 2012, 2, 300-325.

- Xu H.; He W.; Zhang L.L.W. Shaking table test of a novel three-dimensional seismic isolation system with inclined rubber bearings. Eng. Struct. 2023, 293, 1-13.

- Xu T.; Huang X.; Lin X.; et al. Enhancing structural stability in civil structures using the bi-directional evolutionary structural optimization method. AI in Civil Engineering. 2024, 3, 1-10.

- Singh V.; Singh S.K.; Sharma R. A novel framework based on explainable AI and genetic algorithms for designing neurological medicines. Scientific Reports. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).