1. Introduction of Slow Release Fertilizers

The data from the International Fertilizer Association (IFA) reveals a steady escalation in the global consumption of agricultural fertilizers. This trend is indicative of the increasing reliance on chemical inputs to enhance crop yields and meet the demands of a growing global population. The IFA’s projections suggest that the use of fertilizers has seen an average annual increase of 1.3% from 2019 to 2023 [

1], underscoring the agricultural sector’s continued dependence on these resources. Nitrogen fertilizers, in particular, dominate the market due to their critical role in promoting plant growth by providing essential nutrients. However, the efficiency of these fertilizers is marred by significant losses, with estimates suggesting that up to 70% of conventional fertilizers are wasted. This inefficiency has far-reaching environmental implications. The wasted fertilizers contribute to pollution through various mechanisms, including decomposition, leaching, and ammonium volatilization. These processes not only deplete the quality of water resources but also contaminate soil and air, leading to a range of environmental issues such as eutrophication, soil acidification, and the emission of greenhouse gases [

2,

3].

In order to solve the problems from overusing fertilizers, the development of SRFs has emerged as a promising solution. These fertilizers are designed to release nutrients gradually over an extended period, thereby enhancing nutrient uptake by plants and reducing the environmental impact associated with conventional fertilizers [

4,

5]. SRFs encompass a variety of products, including controlled-release fertilizers, enhanced efficiency fertilizers, and smart release fertilizers, among others. Despite the different nomenclatures, all these products should be classified as SRFs, because their primary function is to decelerate the release rate without the ability to modulate performance based on specific agricultural species or environmental conditions. The evaluation standards, including those from the EU, ISO, and GB (China), also categorize these fertilizers as SRFs. Technically, there are two methods to supply nutrients to plants from SRFs: one involves slowing down nutrient availability in the soil or reducing their solubility in water [

6,

7,

8].

Various slow-release methodologies, encompassing physical or chemical reactions, loading into carriers, and coating techniques, have been established [

9,

10,

11]. Among these, coating stands out as a favored approach for developing SRFs due to its simplicity, efficiency, and the ability to precisely control the thickness, thereby modulating the release rate [

12]. A range of petrochemical-derived polymers and biodegradable compounds, including synthetic polylactic acid (PLA) and natural materials such as cellulose, lignin, starch, chitosan, and alginate, have been explored as coating materials for SRFs fabrication [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Given concerns about potential environmental impact from non-biodegradable materials, systems derived from biodegradable polymers, particularly those from renewable sources, have garnered significant interest. Additionally, addressing the challenges of drought and desertification in agriculture, the incorporation of superabsorbent polymers (SAPs) into polymer-coated SRFs products offers benefits such as enhanced water retention in soil and reduced soil pollution [

17,

18,

19]. Recently, the use of eco-friendly hydrogels or SAPs as fertilizer carriers for developing SRFs has attracted growing attention [

20,

21]. The advantages of SRFs based on SAPs encompass improved soil aeration, mitigation of soil degradation, reduced carbon emissions, and enhanced nutrient retention in soil.

There are already many review papers about the development of slow-releasing fertilizers from different angles and at different development stages [

9,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. This review will focus on the development of application eco-friendly hydrogels as fertilizer carrier for SRFs, which has water retention function and unique release mechanisms. The reviewer includes both scientific issues and technical development. Based on the literatures and our experience, we have not only discussed and summarized the achievements, but also pointed out the weakness of current technologies and proposed research directions in this area.

2. Development of Starch-Based Hydrogels

Hydrogels, characterized by their unique capacity to absorb and retain substantial amounts of water, play a crucial role in various scientific and industrial applications. These materials are not only versatile but also exhibit a wide range of properties that can be tailored to specific needs. The fundamental structure of hydrogels consists of a network of hydrophilic polymers that are cross-linked, allowing them to maintain a solid form despite their high water content [

33]. This cross-linking is essential as it prevents the polymer chains from dissolving in water, thereby enabling the hydrogel to absorb water without losing its structural integrity. The composition of hydrogels can vary widely, with both synthetic and natural polymers being utilized. Synthetic polymers like polyacrylic acid (PAA), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polyacrylamide (PAM) are commonly used due to their controllable properties and ease of synthesis [

34,

35,

36]. On the other hand, natural polymers such as proteins, polysaccharides, and nucleic acids offer advantages like bioresorbability and non-toxicity, making them suitable for biomedical applications. Polysaccharides, in particular, are favored for their robustness and cost-effectiveness, with examples including starch, alginate, chitosan, and hyaluronic acid. Manuel and Jennifer [

37] have recently conducted a comprehensive review of hydrogels, encompassing their properties, classification, synthesis mechanisms, and applications across various sectors, with a particular focus on their formulation using starch and cellulose as copolymer components.

Starch, a polysaccharide composed of amylose and amylopectin, exhibits high hydrophilicity, which makes it an attractive precursor for hydrogel synthesis. Starch-based hydrogels have garnered significant attention in the field of agricultural due to their inherent properties such as biodegradability and environmental friendliness. However, the native starch-based hydrogels often suffer from several limitations, including inadequate water absorption capacity, poor mechanical stability, and limited salt tolerance [

38]. To address these challenges, researchers have explored various modification techniques to enhance the properties of starch-based hydrogels [

39,

40,

41]. One of the most effective methods is grafting, where hydrophilic vinyl monomers such as acrylic acid (AA) and acrylamide (AM) are covalently attached to the starch backbone [

42,

43,

44,

45]. This grafting process introduces additional hydrophilic groups into the starch matrix, significantly boosting the hydrogel’s water absorption capacity and mechanical strength. The grafting reaction can be initiated through free-radical polymerization, typically using chemical initiators like ammonium cerium nitrate, persulfate and redox systems [

46,

47]. Crosslinking is a critical step in hydrogel synthesis, as it determines the structural integrity and swelling behavior of the hydrogel. Various crosslinking methods have been employed, including irradiation with ultraviolet (UV) light, microwave irradiation, or gamma (γ) radiation and chemical crosslinking agents [

48,

49].

Starch-based SAPs, which are known for their exceptional water absorption capabilities, are often synthesized via graft polymerization onto starch substrates. These SAPs exhibit the remarkable capacity to absorb water at a rate that is several hundred to several thousand times their own weight. This high absorption capacity is crucial for applications such as agriculture, where SAPs are used to retain water in soil, thereby improving plant growth conditions. Additionally, the ability of SAPs to encapsulate nutrients through physicochemical interactions allows for controlled nutrient release, which can be beneficial in SRFs formulations. Recent studies by Supare and Mahanwar [

48] have extensively reviewed the importance of SAPs in agriculture, focusing on starch-derived SAPs, crosslinking, and graft copolymerization methods employed in their synthesis. This chapter focuses on the methods of synthesizing starch-based SAPs under various process conditions.

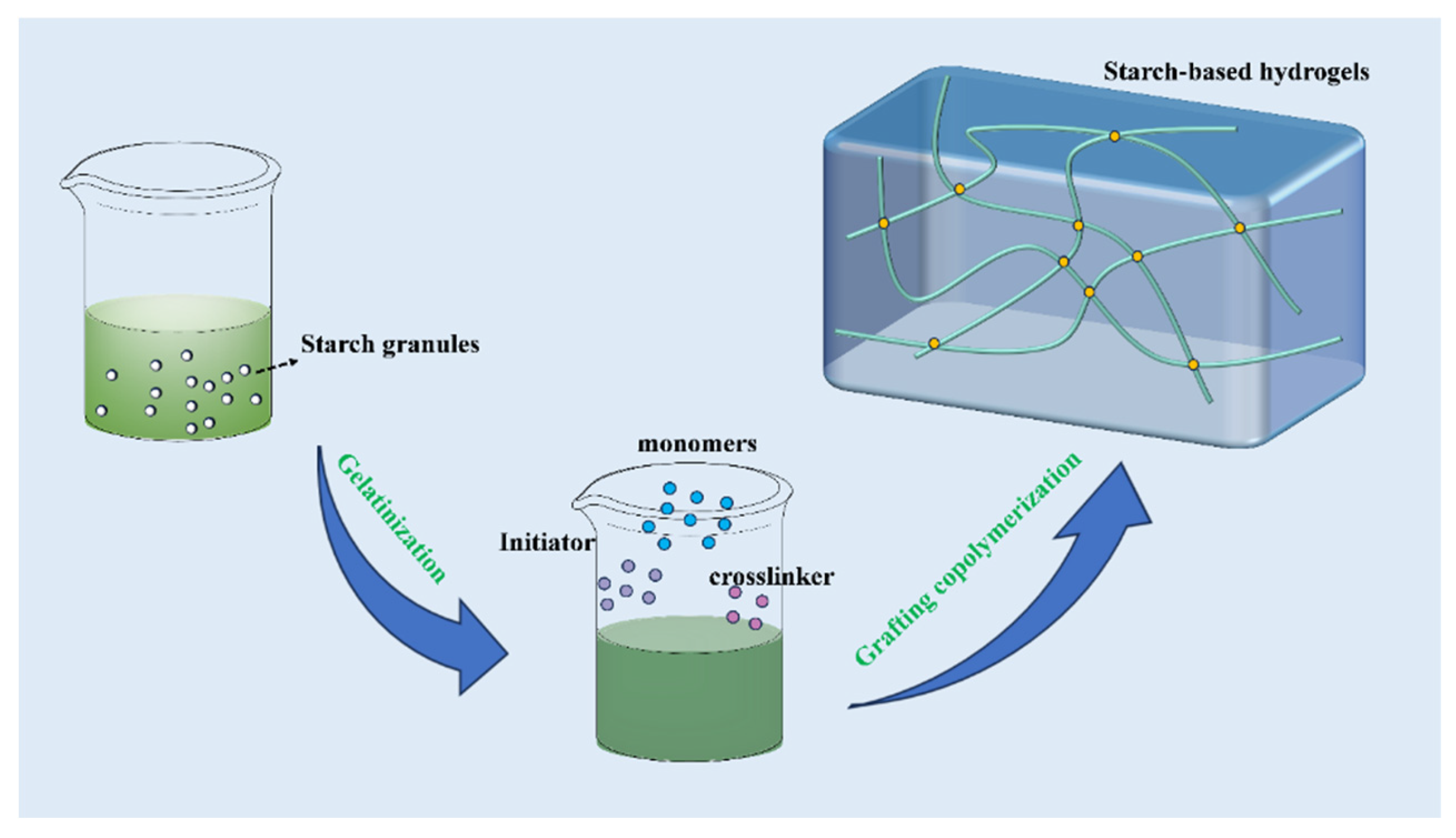

2.1. Grafting Copolymerization with Starches

Starch grafted PAM and PAA are among the most effective superabsorbent materials due to their superior water absorption capabilities. These materials are synthesized through a process known as graft polymerization, which typically takes place in an aqueous medium using batch processing techniques. This method allows for the creation of starch-based SAPs that are highly efficient in retaining water and can be used in various applications ranging from agriculture to personal care products. [

50,

51,

52]. The process of grafting copolymers onto starch in an aqueous medium is shown in

Figure 1. The starch is first gelatinized at a certain temperature, which destroys the crystalline structure of the starch and promotes its uniform dissolution. This step is essential as it enhances the accessibility of the starch molecules to the subsequent chemical reactions involved in the grafting process. Subsequently, a chemical initiator, such as a redox system, is introduced to generate free radicals required to initiate the grafting reaction. Then monomers and crosslinkers are introduced into the solution to start the grafting polymerization reaction. This process continues until the desired degree of polymerization is achieved. The resulting starch-based SAPs are then isolated from the reaction mixture through techniques such as filtration or centrifugation. The isolated SAPs are typically washed and dried to remove any residual monomers, initiators, and by-products. The final product is a highly absorbent material that can retain large amounts of water, making it suitable for a wide range of applications [

53,

54].

Mahmoodi-Babolan et al. [

55] synthesized starch-based SAPs via solution polymerization, incorporating AA and AM. The material’s performance was improved by grafting catecholamine functional groups onto its pore surfaces through the oxidative polymerization of dopamine. The resultant bimodal mesoporous adsorbent demonstrated a swelling ratio of 5914.66%. SAPs have demonstrated efficacy as adsorbents for the elimination of pollutants, notably dyes. Specifically, in the context of methylene blue adsorption, the adsorbent has realized a maximum adsorption capacity of 2276 mg g⁻¹.

Various starches from different resources with different microstructures have been evaluated to be used as raw materials. Zhang et al. [

56] developed three types of rice starch-based superabsorbent materials(SPAM). The findings indicated a minimal occurrence of side reactions, resulting in an exceptionally high acrylic grafting efficiency of 93-94%. Substantial amylose content enhances polymer chain interactions and structural integrity through hydrogen bonding. The structured rigidity of amylopectin’s branched chains in glutinous rice starch contributes to the SPAM’s favorable water absorption properties. Siyamak et al. [

57] reported the grafting of acrylamide monomers through free radical copolymerization onto four distinct starches as potential ammonium sorbents. The findings indicated that there was no significant difference in the average monomer conversion and graft efficiency among the different types of starch. Zou et al. [

58] performed an extensive investigation into the impact of the amylose/amylopectin ratio in corn-derived starches on the grafting reactions and the resultant properties of starch-based SAPs. Their results demonstrated that, under consistent reaction conditions, both the grafting ratio and efficiency increased with higher amylose content, correlating with the water absorption capacity. The high molecular weight and branched structure of amylopectin reduce polymer chain mobility, thereby increasing viscosity and potentially affecting the grafting reactions and performance attributes of starch-based SAPs. Bao et al. [

59,

60] investigated the relationship between molecular structures, viscoelastic properties, graft polymerization, and hydrogel microstructures using cornstarch models with varying amylose/amylopectin ratios. They found that an increase in amylose content resulted in a higher viscoelastic modulus in starch melts, which was associated with a reduced degree of micro-mixing at lower rheological dynamic rates. Although monomer conversion remained nearly constant with increasing amylose content, the grafting efficiency decreased. This decrease was attributed to the higher tendency of high-amylose starch to form crosslinks with grafted components.

In order to enhance the performance of hydrogels, particularly in terms of gel strength and water absorption capacity, researchers have been exploring the synthesis and application of composite hydrogels. One of the primary strategies in enhancing gel strength involves the introduction of reinforcing agents into the hydrogel matrix. These agents can include various types of fibers, nanoparticles, and other polymers that can increase the structural integrity of the hydrogel [

61,

62,

63]. Li et al. [

64] synthesized a starch-

g-PAA/attapulgite superabsorbent composite by incorporating attapulgite micropowder into an aqueous reaction medium. The optimal synthesis conditions, which included 10 w% attapulgite, resulted in a composite with a water absorption capacity of 1077 g H

2O/g sample in distilled water and 61 g H

2O/g sample in a 0.9 w% NaCl solution. This biodegradable, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly superabsorbent composite demonstrates superior water absorbency and water retention capabilities under load, making it particularly suitable for agricultural and horticultural applications.

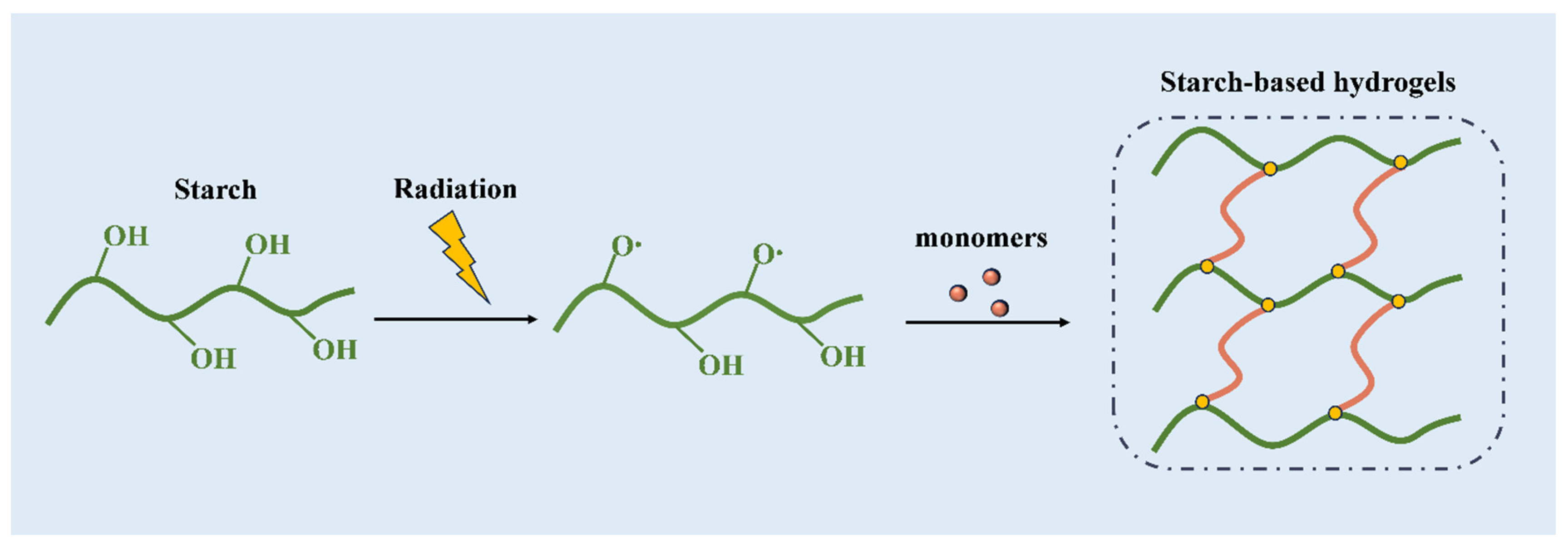

2.2. Radiation In Situ Polymerization

Radiation technology has been extensively employed in the modification of starch, with numerous radiation techniques being utilized to produce starch-based hydrogels [

65,

66,

67,

68]. Radiations are typically classified into ionising and nonionising categories based on their ability to ionise materials. Ionizing radiation has the capability to ionize the medium it passes through, either through direct or indirect interaction with the material. Conversely, nonionising radiation, due to its low ionising potential, is incapable of ionising materials [

69]. Within the realm of ionising radiation, gamma radiation and electron beams are extensively utilized for hydrogel synthesis. In contrast, nonionising radiation has been explored for the microwave-assisted synthesis of hydrogels [

70]. As depicted in

Figure 2, the radiation-induced ionization process of starch generally involves two stages. Initially, covalent bonds are disrupted, leading to the formation of free radicals. Subsequently, the generated ions initiate chemical reactions among molecules at varying concentrations [

71].

Gamma irradiation has been particularly effective in forming three-dimensional polymeric networks of superabsorbent materials, showcasing high efficiency [

72]. This method offers several advantages over conventional methods for fabricating polymeric networks. Traditional techniques often require the use of toxic initiators and crosslinking agents, which can be hazardous to both human health and the environment [

73]. In contrast, gamma irradiation eliminates the need for these chemicals, making the process safer and more environmentally friendly. Additionally, gamma irradiation allows for the conduct of reactions under milder conditions, reducing energy consumption and operational costs [

74]. The formation of minimal by-products further enhances the sustainability of the process, as it reduces waste generation and simplifies the purification steps. The irradiation process is highly controllable, allowing for precise adjustments in the radiation dose to achieve the desired degree of polymerization and crosslinking [

75,

76]. This flexibility enables the production of starch hydrogels with tailored properties, such as absorption capacity, mechanical strength, and biodegradability [

77]. Similar to gamma ray irradiation, electron beam crosslinking represents a clean and safe technique that obviates require any external initiators or crosslinking agents. The electron beam irradiation method surpasses gamma irradiation techniques in hydrogel production, primarily due to its rapid processing speed and precise beam control [

78].

Starch-based hydrogels were synthesized at ambient temperature through the application of gamma radiation [

79,

80]. The study reveals that, within a certain range, an increase in radiation dosage leads to a higher gel fraction. Higher doses generate more persistent free radicals, which enhances the probability of homopolymerization and the formation of an entangled network. As the radiation dose escalates, the concentration of free radicals generated during irradiation also increases, leading to a higher degree of conversion and crosslinking. However, at higher doses, intramolecular free radical recombination becomes more dominant than intermolecular recombination, particularly at sufficiently high absorbed doses, which can inhibit further crosslinking and initiate the degradation of the polymer network. Upon partial substitution of carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) with starch, an enhancement in the swelling capacity of SAP in water was noted when compared to pure CMC gels. The SAPs were synthesized via gamma irradiation of aqueous mixtures containing CMC and starch. The incorporation of starch notably augmented the gel fraction and water absorption capacity at comparatively low irradiation doses of 20 kGy. However, excessive starch content impeded gel formation, consequently reducing the gel fraction. Starch is inherently susceptible to radiation-induced degradation, in the presence of CMC, radicals formed on the starch molecules interact with those on the CMC chains, facilitating crosslinking rather than degradation. [

81].

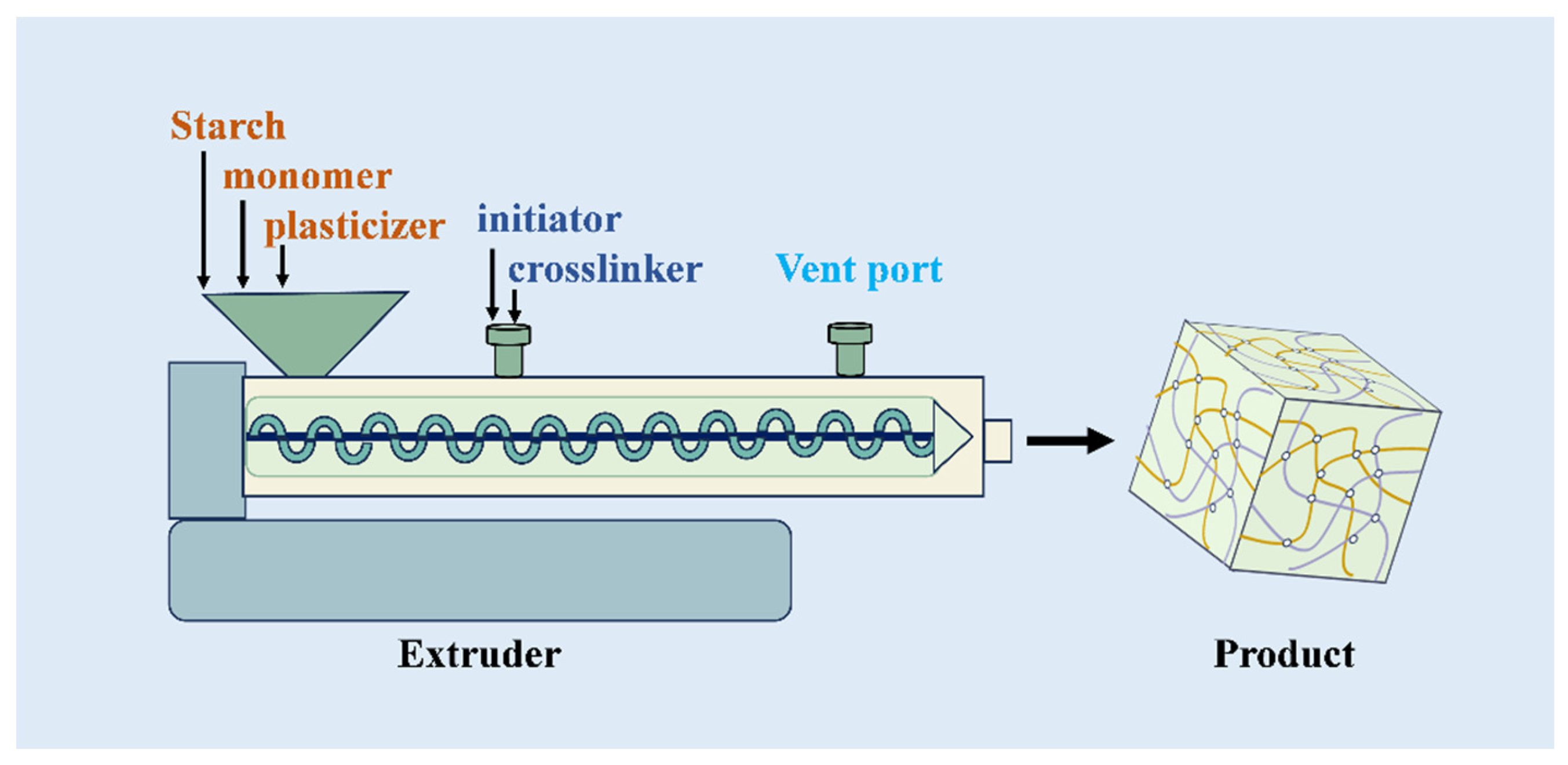

2.3. Application of Reactive Extrusion Technology

As mentioned earlier, traditional methods of producing Starch-based SAPs involve batch processes that are not only solvent-intensive but also inefficient in terms of energy consumption and waste generation. The shift towards reactive extrusion (REX) as a manufacturing technique for SAPs represents a promising advancement that addresses many of these challenges [

82,

83,

84,

85,

86]. As shown in

Figure 3, REX is a continuous process that utilizes extruders as chemical reactors to facilitate the grafting and polymerization of starch-based materials [

87]. This method is particularly advantageous for handling high viscosity polymers, which are often difficult to process using conventional batch techniques [

88]. By reducing the reliance on solvents, REX not only minimizes environmental impact but also enhances the safety and efficiency of the production process.

One of the primary advantages of REX lies in its capacity to offer significant operational flexibility. This flexibility stems from the ability to control various processing parameters, such as temperature and pressure, which are critical in achieving the desired polymer properties [

89,

90,

91,

92,

93]. The extrusion process allows for precise control over the residence time of the reactants within the extruder, which is crucial for optimizing the reaction kinetics and the final product’s performance. The efficiency of REX is another significant advantage. Continuous production lines using REX can achieve high throughput rates, significantly reducing the time required for manufacturing SAPs compared to batch processes. This not only leads to cost savings but also allows for more responsive production schedules, which can be adapted to meet fluctuating market demands [

91]. Furthermore, the reduced need for solvents and the associated waste treatment processes contribute to a more sustainable manufacturing approach. Siyamak et al. [

94] synthesized starch-

g-PAM copolymers through REX, utilizing a screw configuration composed of various elements. The solvent-free graft copolymerization of starch was performed at high solid concentrations, with the reaction reaching completion within 5 minutes. This process resulted in an average monomer conversion rate of 80% and a grafting efficiency of approximately 74%. The flexibility in designing and assembling REX systems for diverse applications is yet another benefit. The modular nature of extrusion equipment allows manufacturers to easily modify and optimize the process for various types of starch-based materials and desired product characteristics [

95]. The adaptability of starch-based SAPs is especially significant in the realm of ongoing research and development, which is dedicated to improving their performance and broadening their applicability.

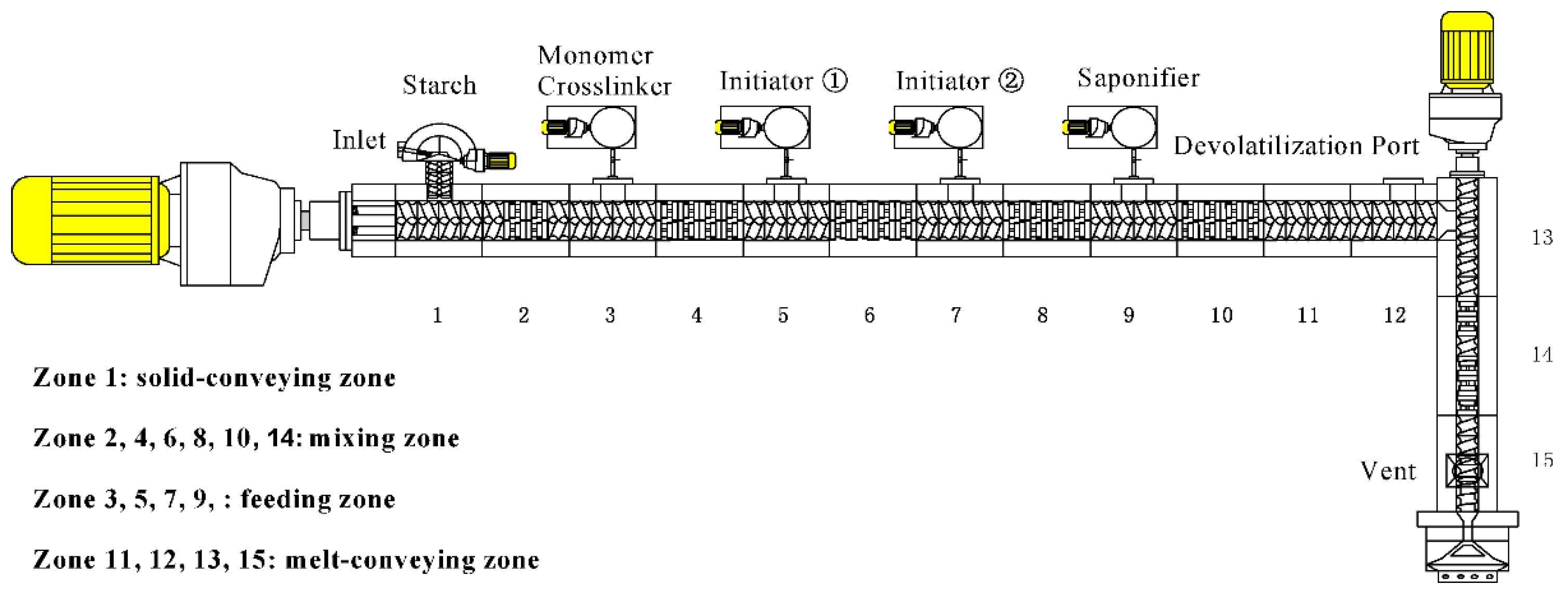

Jiang et al. [

96] developed a REX system (

Figure 4) for the production of starch

-g-PAM hydrogels utilizing a dual initiation mechanism. The REX system, equipped with a twin-screw co-extruder, a solid feeder, and four injection ports, facilitated the separate addition of an acrylamide solution, initiator-1, initiator-2, and a saponifying agent. The dual initiation approach was found to enhance the homogeneity of the hydrogel’s network microstructure and augment its gel strength.

3. Loading Fertilizer into Hydrogels

3.1. Coating by Starch

Among the various methods to create SRFs, the use of coated and matrix types has garnered considerable attention [

97]. Coated-type SRFs, in particular, have been extensively researched for their capacity to modulate nutrient release through the manipulation of coating materials [

11,

98,

99]. These SRFs are typically prepared by applying a layer of inert material onto solid fertilizers to reduce their dissolution rate. The effectiveness of this approach heavily relies on the intrinsic physical attributes of the coating material, including its hydrophobic/hydrophilic nature and porosity. Starch granules have emerged as a promising coating material due to their ability to enhance the adhesion properties of fertilizer surfaces. For instance, Khan et al. [

100] demonstrated a process where starch was incorporated into NPK fertilizers as a binder, ensuring uniform coating of the NPK granules with starch particles. However, native starch possesses limitations such as poor film-forming ability, low water resistance, and susceptibility to damage in humid environments. To overcome these challenges, starch is often chemically modified through processes like esterification, cross-linking, and graft copolymerization to enhance its water resistance [

101,

102,

103,

104]. Modified starch as a coating material has been extensively reviewed [

105], with this chapter specifically delving into the novel application of starch-based hydrogel coatings in SRFs.

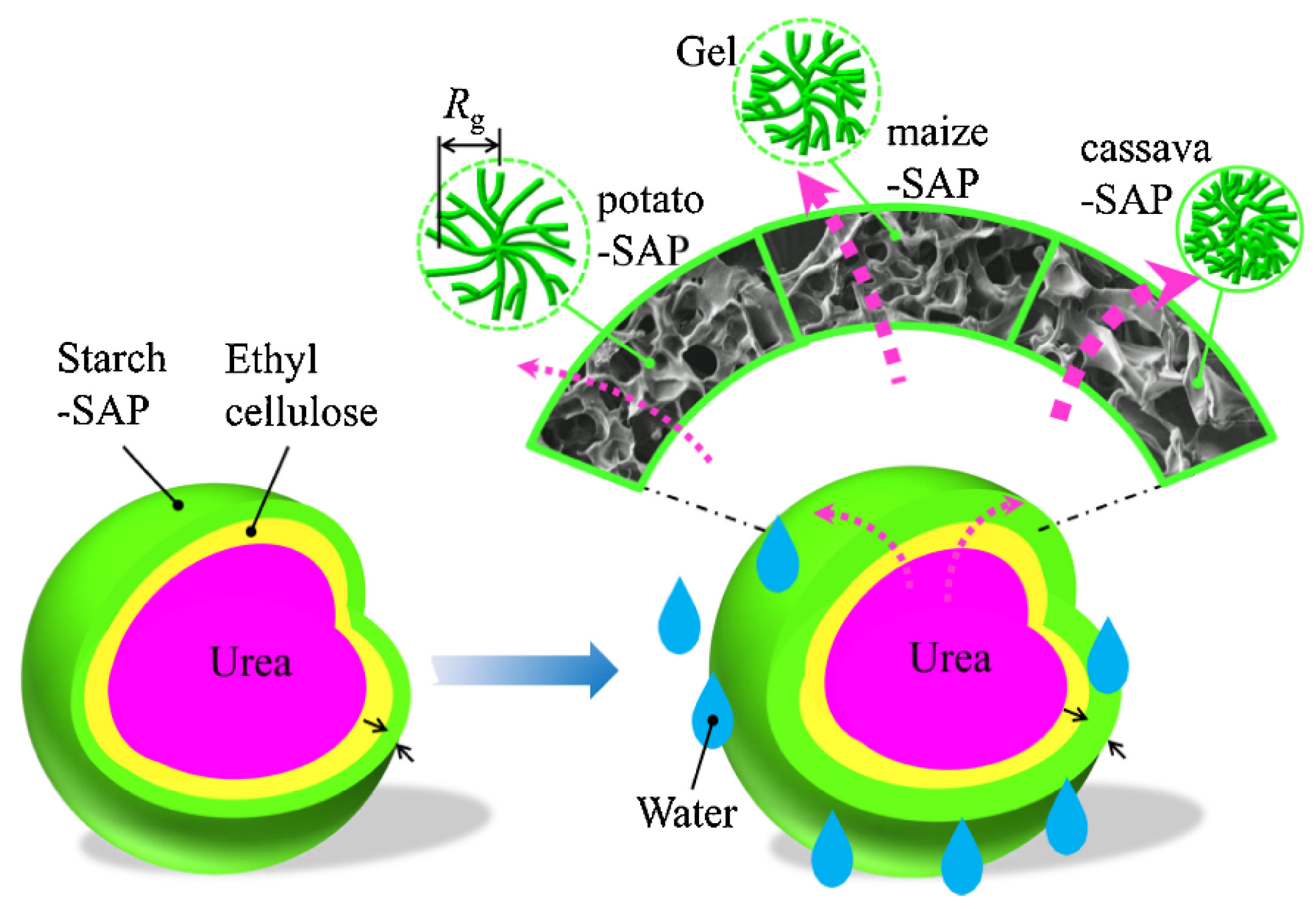

Qiao et al. [

106] introduced a novel double-coated SRF design, utilizing ethyl cellulose (EC) as the inner layer and a starch-based SAP as the outer layer (

Figure 5). The release of nutrients from the double-coated SRF occurs in three distinct phases: (1) the absorption of water by the starch-based SAP and its subsequent permeation through the EC layer, (2) the subsequent dissolution of the urea core’s nutrients by water, and (3) nutrient delivery into the soil through the dual-layered system. The release dynamics of the fertilizer are primarily influenced by the properties of the starch-SAP layer. This innovative double-coating technique significantly augments the controlled release of nutrients and improves the overall efficiency and sustainability of fertilizer application. Similarly, Lü et al. [

107] developed another dual-coated SRFs that incorporated starch acetate and a combination of carboxymethyl starch and xanthan gum. By carefully selecting and modifying coating materials, researchers can tailor the release profiles of SRFs to align with specific agricultural, ultimately leading to more effective and environmentally friendly farming practices.

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), a biodegradable polymer, can form a strong and environmentally friendly coating matrix when combined with starch. The enhancement of interactions and crosslinking within PVA-starch blends not only augments the strength and density of the resulting films but also impedes the swelling of the starch structure by reducing accessible regions, thereby increasing their resistance to dissolution. Zafar et al. [

102] used starch and PVA coatings, acrylic acid, citric acid, and maleic acid as crosslinking agents, and prepared a new type of coated urea SRFs through a granulator/fluidized bed coater. The incorporation of clay nanoparticles, such as bentonite, further augments the mechanical properties of the coating film, making it more durable and effective in controlling the release of nutrients. Sarkar et al. [

108] demonstrated a novel approach to encapsulate diammonium phosphate (DAP) using a blend of wheat starch, PVA, and bentonite clay, aiming to optimize the release kinetics and improve the overall performance of the fertilizer. The resulting coated DAP particles exhibited controlled release characteristics, with the release rate influenced by the concentration of bentonite clay. Higher concentrations of bentonite resulted in slower release rates, as the clay nanoparticles increased the film’s barrier properties and reduced permeability. This controlled release mechanism is beneficial for optimizing nutrient availability to plants and minimizing environmental impact by reducing nutrient leaching. This approach holds promise for the development of sustainable and efficient slow-release fertilizers, contributing to improved agricultural practices and environmental sustainability.

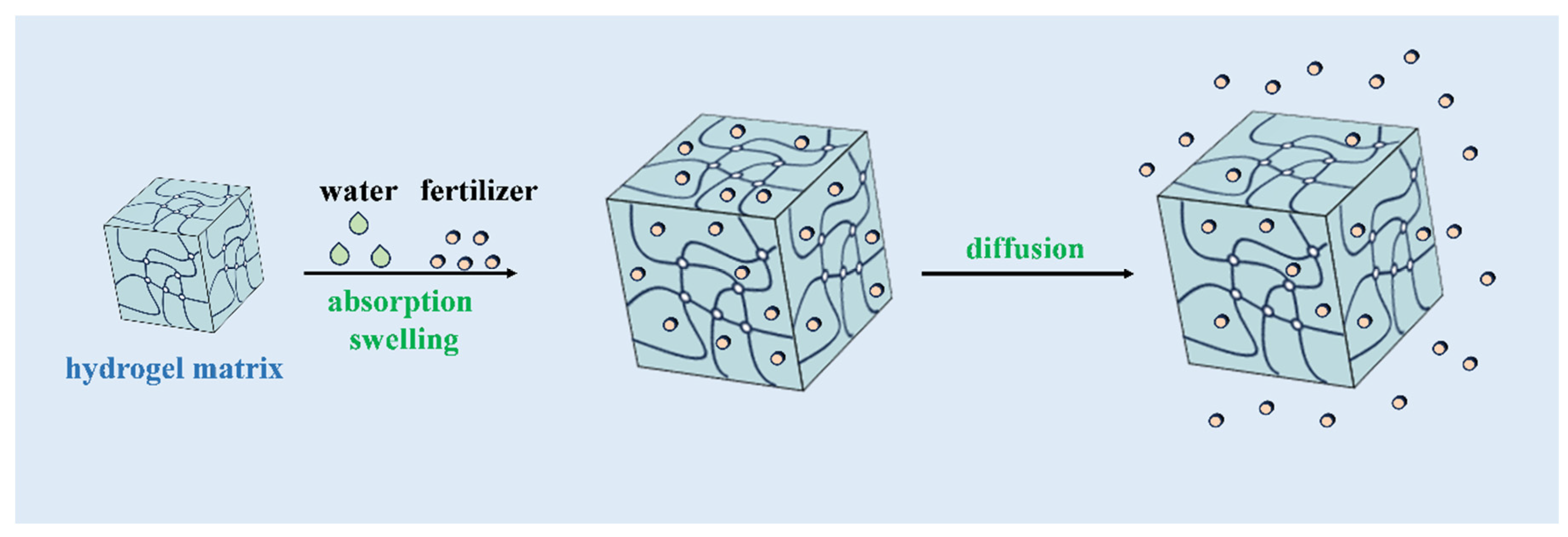

3.2. Swelling and Absorption Equilibrium Method

When hydrogels are immersed in a fertilizer solution, they absorb the nutrients, causing them to swell as they take up the liquid. This process continues until the hydrogels reach an equilibrium state, where they have absorbed as much fertilizer solution as they can hold. These loaded hydrogels can then be applied to the soil, where they release the fertilizers slowly over time as they gradually release the absorbed liquid (

Figure 6). This method allows for controlled and sustained release of fertilizers, which can improve nutrient uptake by plants and reduce the potential for nutrient leaching into the environment.

Leόn et al. [

109] explored the graft copolymerization of starch with itaconic acid to produce SAPs. The findings indicated that an escalation in fertilizer concentration from 0.5 g/L to 10 g/L resulted in enhanced urea absorption and reduced adsorption of KNO

3 and NH

4NO

3. The release behavior of the fertilizers also exhibited variations, with an increase in the loaded fertilizer concentration resulting in reduced release rates for the fertilizers tested. Perez et al. [

110] investigated the macrospheres fabricated from chitosan and chitosan-starch blends. The dry polymer matrices, prepared in advance, were then immersed in the fertilizer-enriched solution for a period of 4 hours at ambient temperature. Following hydration, the macrospheres were subjected to drying at a temperature of 40°C for a duration of 48 hours. Subsequent analyses revealed that the final bead structure significantly influenced their swelling behavior, which in turn dictated their capacity for fertilizer loading and the kinetics of release. These methods of swelling and absorption equilibrium are simple but the weakness is also clear like higher energy to dry the products, limited loading amount depending swelling capability. Since the capability of swelling and absorption of all SAPs will be significantly decreased in the ionic aqueous, which widely existing in various fertilizers, the concentration of fertilizer within SAPs is typically modest.

3.3. In Situ Polymerization Technology

In situ polymerization of starch is a method of directly initiating the polymerization of monomers in the presence of starch, which enables the formation of polymers on the surface or inside the starch granules, thus improving the physicochemical properties of starch or giving it new functions [

111,

112]. Salimi et al. [

113] fabricated a novel slow-release urea fertilizer using an in-situ polymerization process. This method integrated acrylic monomers with starch in the presence of urea, achieving a homogeneous blend. The innovation was further enhanced by incorporating natural char nanoparticles as nano-fillers, which uniformly dispersed within the polymer matrix. This uniform distribution significantly improved the interfacial interactions between the polymer and the fillers, effectively retarding nitrogen diffusion and reducing the release rate in both aqueous and soil conditions.

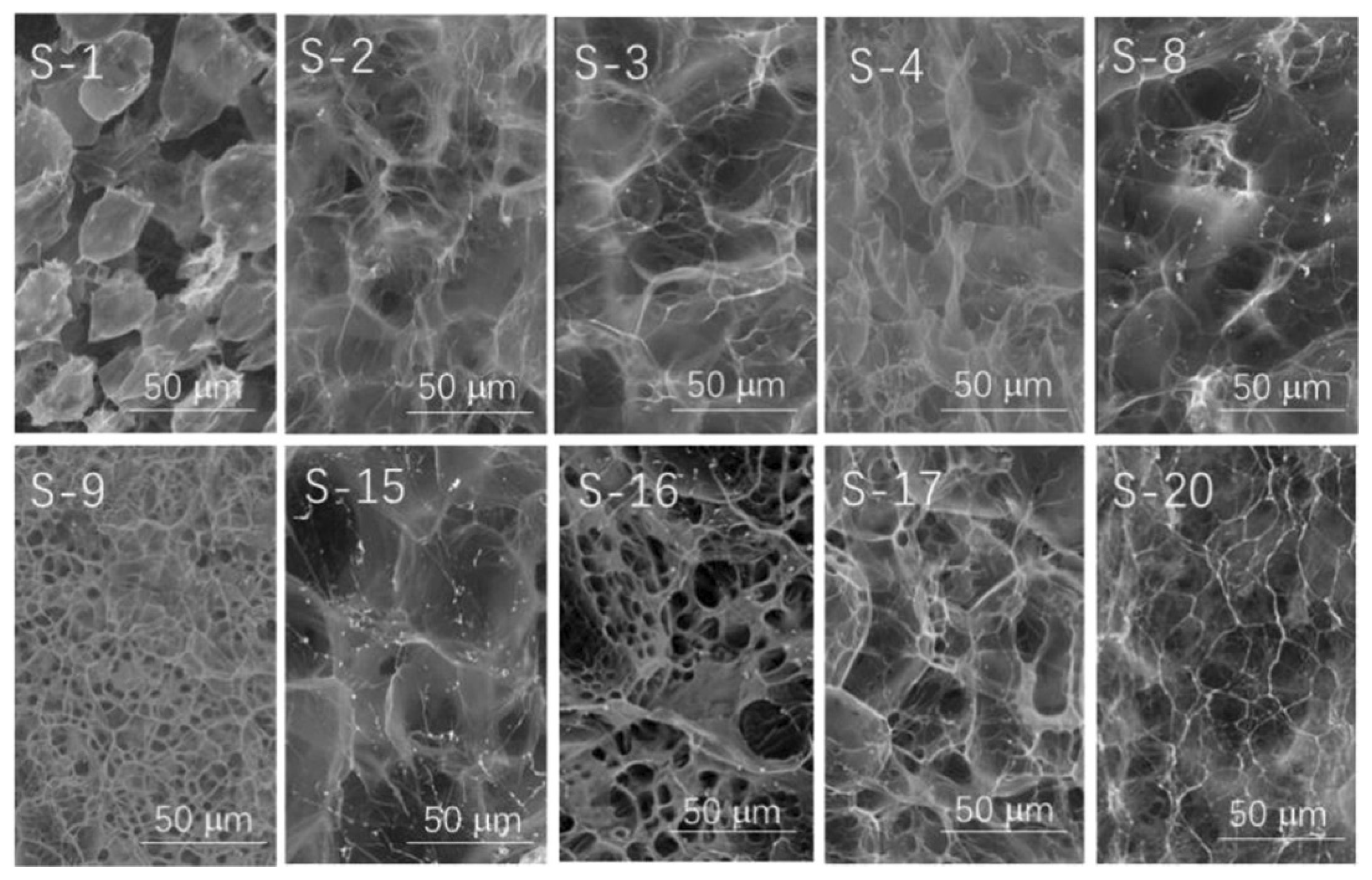

Chen et al. [

114] developed a approach for synthesizing SRFs through in-situ radiation-induced polymerization of monolithic hydrogels. This method involves embedding urea within a starch-based matrix and grafting it with polyacrylamide. The analysis demonstrated distinct microstructures in hydrogels prepared under different conditions (

Figure 7). Low irradiation intensities preserved some honeycomb structures with weaker fibers, but higher intensities resulted in the disappearance of these structures, replaced by larger holes and a denser, more homogeneous cross-linked network. Higher concentrations led to porous structures, whereas lower concentrations produced less dense networks and thinner cell walls. The presence of porous or cottony structures was primarily attributed to the grafted starch matrix, emphasizing the significant influence of irradiation intensity, concentration, and AM/starch ratio on the hydrogel microstructure. An increase in radiation intensity and concentration enhanced grafting efficiency and monomer conversion. Enhanced gel strength, associated with higher radiation levels, AM content, and concentration, correlated with a reduced urea release rate.

3.4. Reactive Extrusion Technology

REX is a continuous process that involves the mixing and chemical modification of polymers in the molten state within an extruder. The extruder is a long, cylindrical machine equipped with a screw that rotates and conveys the polymer forward while mixing it with other components [

115]. The REX process for loading fertilizer into hydrogels typically involves the following steps: (1) Preparation of hydrogel precursors. The first step is the preparation of the hydrogel precursors, which are usually hydrophilic polymers such as PVA, PAA, PAM, starch, cellulose, etc. (2) Incorporation of fertilizer. The fertilizer, which can be in the form of solid particles or a liquid solution, is introduced into the extruder along with the hydrogel precursors. The extruder is designed to provide a controlled environment for the mixing and encapsulation of the fertilizer within the polymer matrix. (3) Crosslinking reaction. As the mixture moves along the extruder, a crosslinking reaction is initiated, typically through the addition of a crosslinking agent or by using heat or radiation. This reaction leads to the formation of the hydrogel network, with the fertilizer particles or molecules being trapped within the polymer matrix. (4) Formation of hydrogel beads. The hydrogel-fertilizer mixture is then extruded through a die, typically in the form of small beads or pellets. These beads are rapidly cooled to solidify the hydrogel structure and stabilize the encapsulated fertilizer.

REX research encompasses a broad spectrum of disciplines, such as chemical reaction engineering, rheology, polymer processing, and mechanics, involving numerous intricate reaction processes. Given the complexity of these processes, the utilization of reactive extrusion in the production of starch-based SRFs remains relatively constrained. A modified Hakke internal mixer was employed as a reactor to synthesize SAPs, mimicking the operation of a twin-screw extruder [

59,

60,

116,

117,

118]. The REX process, while efficient for many polymer processing applications, presents a unique challenge when it comes to the preservation of the cross-linked structure of hydrogels. The cross-linking in hydrogels is a critical factor that determines their mechanical strength, swelling behavior, and degradation rate. During the reaction extrusion process, which involves the extrusion of a polymer melt through a die, the high shear forces and thermal conditions can potentially disrupt the delicate cross-linked structure of the hydrogel. This disruption can lead to a decrease in the mechanical integrity of the hydrogel, affecting its performance in practical applications. To circumvent the potential degradation of the cross-linked structure during the reaction extrusion process, an alternative approach known as post-cross-linking can be employed. Post-cross-linking involves the formation of cross-links in a polymer matrix after the initial processing steps. This method allows for the preparation of hydrogels with controlled cross-linking density and distribution, which is crucial for optimizing the properties of the hydrogel for specific applications.

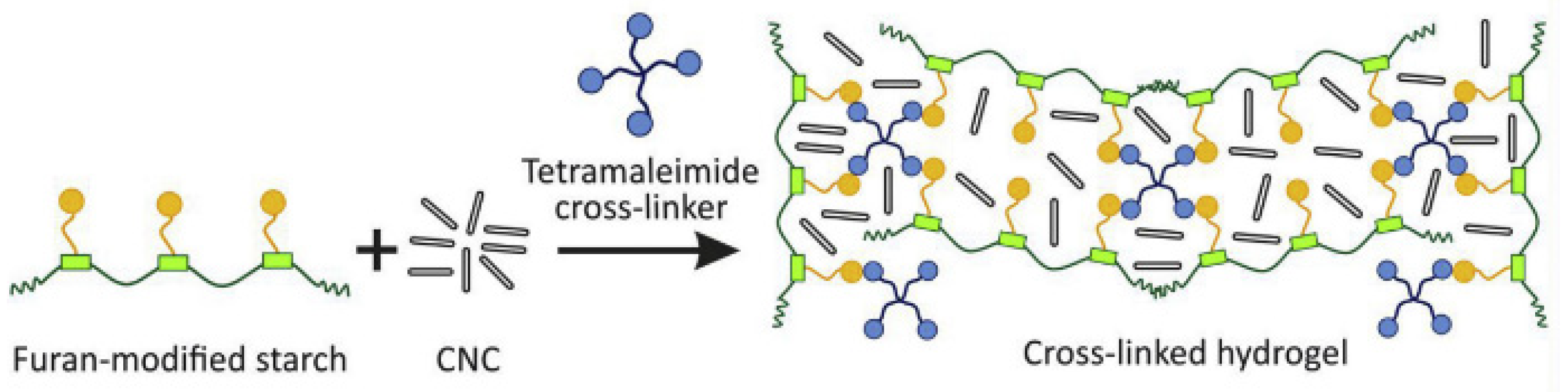

3.5. Compounding with Cellulose

Cellulose is a polymeric compound, ubiquitously present in the cell walls of plants, stands out as the most plentiful and sustainably sourced material on our planet. It is endowed with a rich array of functional groups, remarkable mechanical properties, and a high degree of chemical adaptability for modifications [

119]. Furthermore, the capability to render cellulose into fibrous forms at the micro- or nanometer-scale has positioned it as an increasingly promising contender for the creation of hydrogels in recent years. Li et al. [

120] reviewed various modification methods of cellulose and the application of stimuli-responsive hydrogels in slow-release fertilizers. Manuel et al. [

37] conducted an review on hydrogels, delving into their properties, classifications, synthesis mechanisms, and the diverse applications across various industries. From the article, starch and cellulose were highlighted as copolymers, showcasing their integral roles in the development and functionality of hydrogels.

Cellulose-based composites have garnered significant attention in recent years due to their potential as reinforcing fillers in biopolymer matrices derived from starch [

63,

121,

122,

123] (

Figure 8). Starch composite cellulose hydrogels are both biodegradable and renewable polymers, these hydrogels can slowly release nutrients to plants, providing a controlled and sustained supply of essential elements for plant growth. Bora et al. [

124] utilized wastepaper powder as a modifier in a biodegradable hydrogel composite composed of starch, itaconic acid, and acrylic acid. The incorporation of an optimal quantity of the modifier increased the hydrogel’s swelling capacity from 503 g/g to 647 g/g. The NPK-laden hydrogel demonstrated effective sustained-release characteristics, with 98% of nitrogen, 81% of phosphorus, and 95% of potassium being released over 20 days.

3.6. Other Hydrogel Systems

Interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) hydrogels based on starch represent a promising class of materials that combine the biodegradability and biocompatibility of starch with the mechanical properties and functional versatility of synthetic polymers. These hydrogels are formed by the simultaneous or sequential polymerization of starch with one or more synthetic polymers, resulting in a network structure where both components are interwoven. This interpenetration enhances the overall performance of the hydrogel, rendering it appropriate for SRFs. Vudjung et al. explored the synthesis of crosslinked natural rubber and cassava starch hydrogels through the IPN method [

125]. This approach aimed to enhance mechanical strength and compatibility by integrating multiple network polymers. These hydrogels demonstrated high water swelling capabilities and favorable biodegradation properties. However, the rigid nature of the final product precluded its application as a coating on urea bead surfaces. To mitigate this issue, they sought to innovate by developing a novel coating membrane from pre-vulcanized natural rubber (NR) and starch (St), employing the IPN method with sulfur and glutaraldehyde as crosslinking agents [

126]. The release mechanism of urea in both aqueous and soil environments was characterized as non-Fickian diffusion, suggesting transport through a porous matrix. The efficacy of encapsulated urea beads in corn and basil cultivation was significantly superior to that of native urea beads.

Apart from cellulose, starch can also form complexes with other polysaccharides to construct a SRFs system. Pimsen et al. [

127] focused on the creation of SRFs utilizing a nano zeolite (NZ) composite incorporated into chitosan (CS)/sago starch (ST)-based biopolymers. The biopolymer nanocomposite was synthesized through an ionotropic gelation method, employing sodium tripolyphosphate as the crosslinking agent. The swelling capacity of the biopolymer nanocomposite notably increased with higher molecular weights of CS and increased crosslinking durations. The NZ-CS/ST nanocomposite exhibited a release of 64.00% phosphorus and 41.93% urea by the 14th day. Majeed et al. [

128] investigated the impact of lignin concentration on the release and biodegradability of urea-modified tapioca starch-based enhanced efficiency fertilizers. They found that incorporating lignin at levels of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% into the starch matrix decreased nutrient release in moist soil. Furthermore, an increase in lignin content was associated with enhanced biodegradability.

The integration of inorganic fillers into starch-based hydrogel SRFs represents a significant advancement in agricultural technology, offering multifaceted benefits that enhance the overall efficacy and sustainability of fertilizer applications. This integration is particularly crucial in modern agriculture, where the need for efficient, environmentally friendly, and cost-effective fertilization methods is paramount. These fillers serve as potent reinforcing agents, significantly bolstering the hydrogel’s resilience against mechanical stress, including wear and compression [

129]. Furthermore, they enhance the hydrogel’s capacity to retain water, ensuring a robust performance in various applications. Lu et al. [

130] studied a novel slow-release fertilizer characterized by high water retention, designated as HS-BCF, which is synthesized by integrating hydrotalcite and starch into biochar-based compound fertilizers (BCF). The findings indicate that the addition of hydrotalcite and starch to BCF enhances the soil water-retention capacity by 5-10%. Over a period of 30 days, the cumulative leaching amounts of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium from HS-BCF in soil were, at most, 49.4%, 13.3%, and 87.4% of those from BCF, respectively. Furthermore, hydrotalcite was found to bind with phosphorus in HS-BCF, thereby improving the longevity of phosphorus in the fertilizer. Wei et al. [

131] reported a novel slow-release and water-retention fertilizer through the free radical copolymerization of potato starch, acrylic acid, acrylamide, and maleic anhydride-modified β-cyclodextrin. This synthesis process was enhanced by incorporating acid-treated halloysite nanotubes, which were engineered to expand their internal cavities for optimal urea pre-loading. The addition of these halloysite nanotubes has improved the fertilizer’s release profile, effectively regulating the cumulative release rate of urea from the slow-release formulation.

4. Release Mechanisms and Kinetics

4.1. Release Mechanisms

The release of nutrients from SRF hydrogels is a multifaceted process involving several stages and mechanisms. A comprehensive understanding of these mechanisms is essential for optimizing the design and application of hydrogels in agricultural contexts. The nutrient release profile of hydrogels typically encompasses three distinct phases: the lag period, the constant release phase, and the decay period, each of which contributes uniquely to the overall release dynamics. [

132]. During the lag period, the hydrogel absorbs water from the surrounding environment, initiating the swelling process. This initial stage is characterized by minimal nutrient release as the hydrogel undergoes hydration and expansion. The constant release stage follows, where the hydrogel reaches a state of equilibrium, and nutrients are released at a steady rate. This stage is influenced by the diffusion of nutrients through the polymer matrix and the continued hydration and expansion of the polymer chains. Finally, the decay period occurs when the release rate of nutrients begins to decline, often due to the depletion of available nutrients within the hydrogel or changes in the surrounding environmental conditions.

The release mechanisms of hydrogels are multifaceted and cannot be attributed to a single process. Multiple concurrent processes, including diffusion through the polymer, hydration, expansion, and dissolution of the polymer chains, contribute to the overall release behavior [

133,

134]. Diffusion through the polymer matrix is a critical mechanism, enabling the transport of nutrients from regions of higher concentration to those of lower concentration within the hydrogel. This process is influenced by the porosity of the polymer network, the size of the nutrient molecules, and the degree of cross-linking within the polymer. Hydration and expansion of the polymer chains are also essential mechanisms in the release of nutrients from hydrogels. As the hydrogel absorbs water, the polymer chains swell, creating additional space within the polymer matrix. This swelling allows for the movement of nutrient molecules and facilitates their release into the surrounding environment. The degree of swelling is influenced by the nature of the polymer, the degree of cross-linking, and the ionic strength and pH of the surrounding environment. Polymers with higher hydrophilicity and lower cross-linking density tend to exhibit greater swelling, which can enhance the release of nutrients.

To better understand the swelling process and its impact on nutrient release, various kinetic models have been developed [

135,

136]. These models aim to dissect the underlying mechanisms and provide insights into the factors that influence the swelling behavior of hydrogels. The swelling behavior of the hydrogel can be delineated into two distinct phases: an initial phase of rapid swelling, succeeded by a subsequent phase of gradual and slower swelling. The initial phase is distinguished by the swift absorption of water molecules into the hydrogel’s porous matrix. This process is facilitated by the hydrophilic nature of the polymer and the presence of pores or channels within the polymer matrix. In the subsequent gradual swelling phase, water molecules penetrate the pores induced by the relaxation of polymer chains. This process is slower and more protracted, reflecting the gradual uptake of water and the continued expansion of the polymer matrix. The initial rapid swelling and the gradual swelling phase is influenced by several factors, including the nature of the polymer, the degree of cross-linking, and the environmental conditions. Polymers with higher hydrophilicity and lower cross-linking density tend to exhibit more pronounced initial rapid swelling, while polymers with higher cross-linking density and lower hydrophilicity tend to exhibit more gradual swelling.

The swelling characteristics of superabsorbent polymers are substantially influenced by environmental factors, including temperature, pH, and ionic strength. Variations in these parameters can modulate both the rate and the degree of swelling, consequently impacting the nutrient release profile. Specifically, elevated temperatures enhance the diffusion of water molecules into the hydrogel matrix, resulting in more pronounced swelling and a subsequent increase in nutrient delivery. Similarly, changes in pH can affect the ionization of functional groups within the polymer, altering the hydrophilicity and swelling behavior of the hydrogel. Ionic strength can also impact the swelling behavior by affecting the osmotic pressure within the hydrogel, which drives the uptake of water [

137,

138]. Al Rohily et al. [

139] investigated the swelling properties of fertilizer materials derived from phosphorylated alginate that was grafted with polyacrylamide (PAM). The swelling behavior of these hydrogel polymers is significantly affected by the degree of crosslinking and the presence of pendant ionic groups within the polymer matrix. The swelling in these hydrogel networks is predominantly governed by the presence of ionic charges, wherein the repulsion between adjacent fixed charged groups induces network expansion, consequently resulting in swelling. Shang et al. [

135] employed the Korsmeyer-Peppas and pseudo-second-order kinetic models to analyze the swelling characteristics of temperature-responsive hydrogels. Their study revealed that these models accurately described the swelling kinetics, suggesting that water molecule transport within the hydrogel is predominantly governed by Fickian diffusion and the relaxation of polymer chains.

The release mechanisms of SRFs hydrogel are multifaceted and involve a combination of diffusion, swelling and deswelling, chemical degradation, mechanical stress, ion exchange, and temperature effects. These mechanisms work synergistically to provide a controlled and sustained release of nutrients to plants, enhancing nutrient use efficiency and promoting plant growth. The design and optimization of hydrogel fertilizers require a deep understanding of these release mechanisms and their interactions with environmental factors to achieve the desired nutrient delivery profile.

4.2. Kinetic Modals

The development of release kinetic models for fertilizers is a critical aspect of agricultural science, particularly in the optimization of nutrient delivery to plants. These models are essential for understanding and predicting the behavior of fertilizers in various environmental conditions, which in turn aids in maximizing crop yields and minimizing environmental impact. One of the primary reasons for the necessity of quantitative analysis in developing release kinetic models is the dynamic nature of nutrient release. Fertilizers do not release nutrients at a constant rate; instead, the release rate can vary significantly depending on factors such as temperature, moisture, and the biological activity in the soil. Quantitative analysis allows for the measurement of these variables over time, providing data that can be used to construct mathematical models that accurately predict nutrient release patterns. For instance, the type of fertilizer, whether it is a conventional, slow-release, or controlled-release formulation, significantly impacts the release kinetics. Given the variability in nutrient-release mechanisms among various types of SRFs and the intricate interplay of factors such as composition, soil moisture, and temperature, the release mechanisms of SRFs cannot be simplistically characterized. Typically, four primary mathematical models are employed to elucidate these mechanisms: the zero-order, first-order, Korsmeyer-Peppas, and Higuchi kinetic models can be represented by the following equations (Equations (1)–(4), respectively):

Specifically, the parameter M

t/M

∞ denotes the percentage of fertilizer released from the hydrogel at a specific time t. The constants k

0, k

1, k

H, and k represent the release constants for the zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, and Korsmeyer-Peppas models, respectively. The release mechanisms are classified according to the diffusion index (n) as follows: (1) Fickian diffusion mechanism: n < 0.43; (2) Non-Fickian diffusion mechanism: 0.43 < n < 0.85; (3) Case-II transport mechanism: n > 0.85 [

120].

Indeed, the slow-release model of SRFs hydrogel exhibits variation across different stages. Shaghaleh et al. [

140] developed an aminated cellulose nanofiber (A-CNF) fertilizer hydrogel by encapsulating ammonium nitrate (AN) within the A-CNF matrix. During the initial phase, the hydrogel demonstrated rapid AN release within the first 72 h, conforming to a first-order kinetic model (k

1 = 0.068-0.0575). This phase was characterized by the swelling of A-CNF upon exposure to buffer or soil media, leading to diffusion of AN influenced by pH levels. In the subsequent phase, spanning 144 to 504 h, the hydrogel exhibited a controlled release pattern, adhering to a zeroth-order kinetic mechanism. This stage was marked by a significant decrease in the AN release rate (k

0 = 0.0023-0.0027), ensuring sustained AN availability until the hydrogel’s degradation commenced. The final release phase, occurring between 720 and 1540 h, involved degradation of the hydrogel’s polymeric network, particularly in soil conditions. This degradation resulted in the breakdown of A-CNFs and the formation of oligomeric fragments, enlarging the pore structure and enhancing AN release, which was previously restricted within the dense hydrogel matrix. This stage followed the Higuchi model, with an increased release rate (k

H = 0.0281-0.0268). Notably, soil properties significantly moderated the AN release rates across all stages and pH levels, compared to buffer media, leading to a more consistent and stable AN release profile.

The mechanism by which water molecules permeate the hydrogel matrix and subsequently induce chain relaxation within the hydrogel is a pivotal process that dictates the swelling dynamics and nutrient release kinetics of the hydrogel. Tanan et al. [

141] developed biodegradable semi-IPN hydrogels composed of cassava starch (CSt)-

g-PAA, natural rubber (NR), and PVA. The release kinetics of urea in both aqueous and soil environments conformed to the Korsmeyer-Peppas model. The behavior of these hydrogels was found to be non-Fickian when the NR content was ≤ 50%, suggesting that water diffusion and polymer chain relaxation jointly governed the swelling process. Conversely, hydrogels with an NR content above 50%, the diffusion was characterized as pseudo-Fickian (or less-Fickian) with an n value < 0.5. This suggests that the solvent penetration into hydrogels with NR > 50% is more dependent on the hydrophobicity of the system rather than the relaxation of polymer chains, which correlates with a decrease in the equilibrium swelling ratio (S

eq). These findings demonstrate that the S

eq and n values of hydrogels can be modulated by adjusting the NR/PVA ratios to suit specific application requirements.

Chamorro et al. [

142] prepared cassava starch hydrogels in an aqueous environment. Upon swelling, the polymer matrix undergoes macromolecular relaxation, transitioning to a rubbery state that typically allows solute diffusion into the surrounding aqueous phase. However, if the rate of water penetration is significantly lower than the polymer chain relaxation rate, the diffusion is characterized as “Less-Fickian” with an “n” value less than 0.5, although it remains within the Fickian classification. The release kinetics of potassium followed a Less-Fickian diffusion pattern, suggesting that its release is predominantly governed by the water intake rate, which promotes swift diffusion through the hydrogel’s rubbery matrix. In contrast, nitrogen release is influenced by the hydrogel’s high fluidity, which enhances water permeation into the biopolymer network.

In conclusion, release kinetic models are indispensable tools in the field of agricultural science. They provide a quantitative framework for understanding and predicting the behavior of fertilizers, which is crucial for optimizing nutrient delivery to plants and ensuring sustainable agricultural practices. By combining quantitative analysis with mathematical and geometrical models, researchers can develop more effective and environmentally friendly fertilizer formulations, ultimately leading to healthier plants and higher crop yields

5. Summarizing and Future Directions

In the pursuit of sustainable agricultural practices, the development of controlled-release fertilizers (CRFs) and smart fertilizers has garnered significant attention. These innovative fertilizers are designed to optimize nutrient delivery to crops in a manner that closely aligns with their growth requirements, thereby enhancing plant health and productivity while minimizing environmental impacts. The use of eco-friendly starch hydrogels in the formulation of these fertilizers not only aids in slow-release mechanisms but also contributes to improved water retention in the soil, a critical factor in arid and semi-arid regions where water scarcity is a pressing issue. Starch hydrogels, derived from renewable plant sources, offer a biodegradable and environmentally friendly alternative to traditional synthetic polymers used in fertilizer encapsulation. These hydrogels can be engineered to have varying degrees of permeability, allowing for precise control over the release of nutrients into the soil. The incorporation of starch hydrogels into fertilizer formulations can significantly reduce the initial burst effect commonly associated with conventional fertilizers, where a large amount of nutrients are released quickly, often leading to nutrient leaching and runoff.

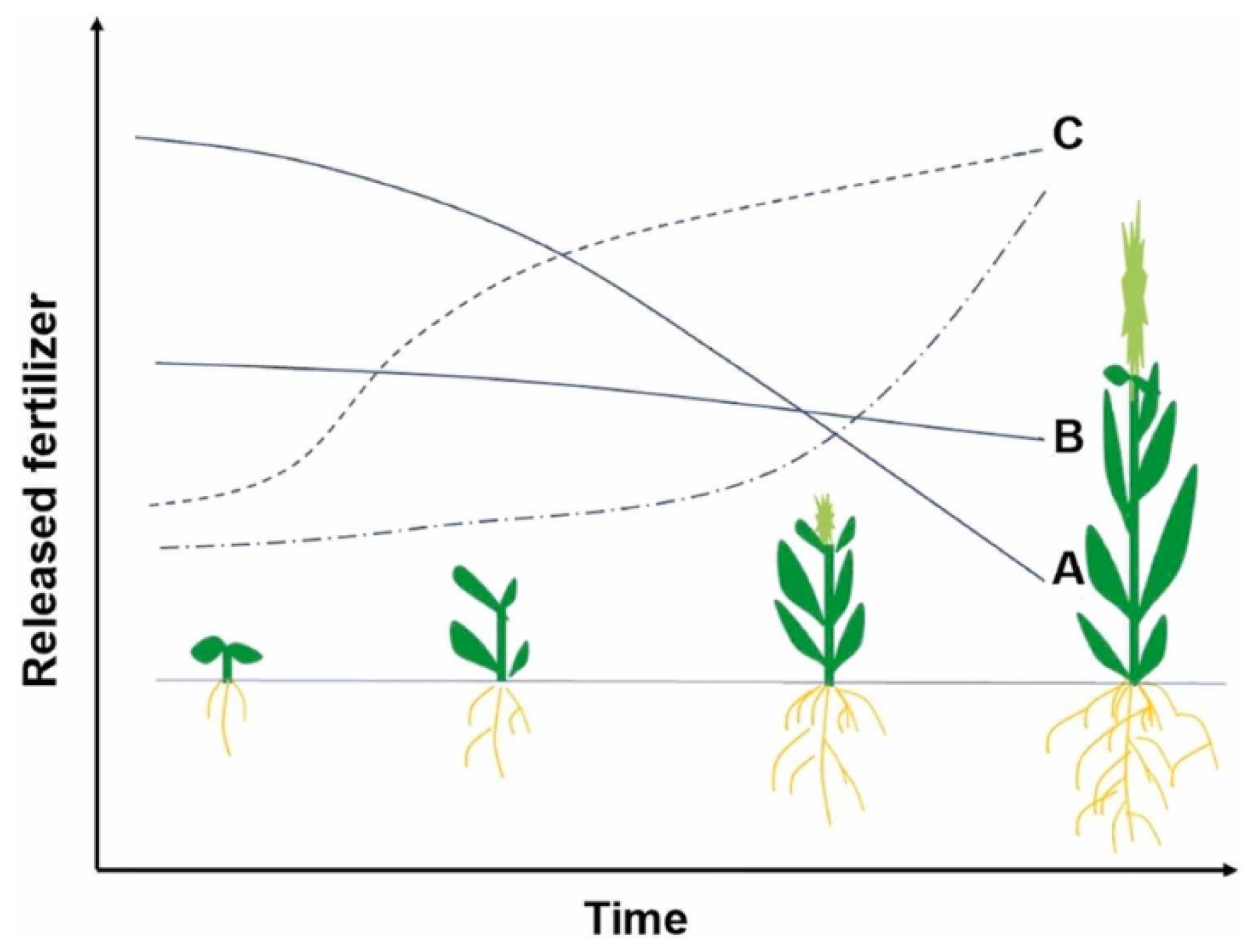

Figure 9 provides a schematic depiction of plant growth in relation to the release of fertilizer, highlighting the discrepancy between the conventional rates of fertilizer release and the nutrient requirements of plants [

143,

144]. Corn, for instance, undergoes distinct growth phases: sowing, seedling, tasseling, and grain filling, each with varying nutrient demands. Traditional fertilizers like urea, due to their high solubility, release nutrients rapidly, often at times when the plant requires them the least. This mismatch can lead to inefficiencies in nutrient utilization and potential environmental harm.

Smart fertilizers, on the other hand, are designed to release nutrients in a controlled manner that mimics the natural uptake patterns of plants. By adjusting the composition and structure of starch hydrogels, researchers can modulate the release kinetics of nutrients, ensuring that they are available to the plant when needed. This approach not only enhances crop yields but also reduces the overall amount of fertilizer required, making agriculture more sustainable and cost-effective. The potential of smart fertilizers extends beyond traditional soil-based agriculture to soilless cultures, including hydroponics and aeroponics. In these systems, precise control over nutrient delivery is crucial for maintaining optimal plant growth conditions. Starch hydrogels can be adapted for use in nutrient reservoirs, providing a steady and controlled release of nutrients directly to the plant roots. This application can lead to more efficient nutrient use and reduced waste, further supporting the sustainability of soilless cultivation methods.

Despite the promising developments in the field of smart fertilizers, several challenges remain. The development of truly responsive fertilizers that can adapt to changing environmental conditions and plant needs is still in its infancy. Future research should focus on integrating advanced sensing technologies with fertilizer formulations to create fertilizers that can dynamically adjust their release rates based on real-time data on soil conditions, weather patterns, and plant health. Moreover, the commercialization of these advanced fertilizers requires careful consideration of cost-effectiveness and scalability. While the benefits of using starch hydrogels and other eco-friendly materials are clear, their adoption will depend on their economic viability compared to traditional fertilizers.

The development of slow-releasing fertilizers with water retention capabilities using eco-friendly starch hydrogels represents a significant step forward in sustainable agriculture. By aligning nutrient release with plant growth needs and enhancing soil moisture retention, these fertilizers can contribute to more efficient and environmentally friendly farming practices. As research continues to advance, the potential for these smart fertilizers to revolutionize agriculture and support global food security becomes increasingly evident.

Author Contributions

As a review paper, the name position presents his/her contribution.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22178124), High-level Talent Research Start-up Project Funding of Henan Academy of Sciences (No. 232018005, 231818017), Joint Fund of Henan Province Science and Technology R&D Program (No. 225200810010, 230618025), Key Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Province (No. 232102230101), Fundamental Research Fund of Henan Academy of Sciences (No. 230618025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Association, I. F., Fertilizer Outlook 2019—2023. In 87th IFA Annual Conference, Montreal, Canada, 11-13 June 2019.

- Naz, M. Y.; Sulaiman, S. A. , Slow release coating remedy for nitrogen loss from conventional urea: a review. J. Control. Release 2016, 225, 109–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindasamy, P.; Muthusamy, S. K.; Bagavathiannan, M.; Mowrer, J.; Jagannadham, P. T. K.; Maity, A.; Halli, H. M.; G. K., S.; Vadivel, R.; T. K., D.; Raj, R.; Pooniya, V.; Babu, S.; Rathore, S. S.; L., M.; Tiwari, G., Nitrogen use efficiency—a key to enhance crop productivity under a changing climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Ortiz, R.; Naranjo, M. A.; Ruiz-Navarro, A.; Atares, S.; Garcia, C.; Zotarelli, L.; San Bautista, A.; Vicente, O. , Enhanced Agronomic Efficiency Using a New Controlled-Released, Polymeric-Coated Nitrogen Fertilizer in Rice. Plants 2020, 9, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messiga, A. J.; Dyck, K.; Ronda, K.; van Baar, K.; Haak, D.; Yu, S.; Dorais, M. , Nutrients Leaching in Response to Long-Term Fertigation and Broadcast Nitrogen in Blueberry Production. Plants 2020, 9, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, G. , Contemporary strategies for enhancing nitrogen retention and mitigating nitrous oxide emission in agricultural soils: present and future. Environ. Dev. Sustainability 2019, 22, 2703–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Gao, B.; Tong, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y. , Chitosan and graphene oxide nanocomposites as coatings for controlled-release fertilizer. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2019, 230, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Bao, X.; Yu, L.; Liu, H.; Lu, K.; Chen, L.; Bai, L.; Zhou, X.; Li, Z.; Li, W. , Correlation Between Gel Strength of Starch-Based Hydrogel and Slow Release Behavior of Its Embedded Urea. J. Polym. Environ. 2020, 28, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Jiang, S.; Chen, F.; Li, Z.; Ma, L.; Song, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, L. , Fabrication, evaluation methodologies and models of slow-release fertilizers: a review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 192, 116075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Chen, D. , Classification research and types of slow controlled release fertilizers (SRFs) used—a review. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2018, 49, 2219–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, I.; Ablouh, E.-H.; El Bouchtaoui, F.-Z.; Jaouahar, M.; El Achaby, M. , Polymer coated slow/controlled release granular fertilizers: Fundamentals and research trends. Prog. Mater Sci. 2024, 101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beig, B.; Niazi, M. B. K.; Jahan, Z.; Hussain, A.; Zia, M. H.; Mehran, M. T. , Coating materials for slow release of nitrogen from urea fertilizer: A review. J. Plant Nutr. 2020, 43, 1510–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Assimi, T.; Blažic, R.; Vidović, E.; Raihane, M.; El Meziane, A.; Baouab, M. H. V.; Khouloud, M.; Beniazza, R.; Kricheldorf, H.; Lahcini, M. , Polylactide/cellulose acetate biocomposites as potential coating membranes for controlled and slow nutrients release from water-soluble fertilizers. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 156, 106255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, N.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ma, Y.; Ruso, J. M.; Liu, Z. , Engineering and slow-release properties of lignin-based double-layer coated fertilizer. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2023, 34, 2029–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, A. N.; Pillai, S. S.; Aravind, M.; Salim, S. A.; Kuzhivilayil, S. J. , Cassava starch-graft-poly (acrylonitrile)-coated urea fertilizer with sustained release and water retention properties. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2018, 37, 2687–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Huang, H.; Han, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, C. , Poly (vinyl alcohol)/sodium alginate polymer membranes as eco-friendly and biodegradable coatings for slow release fertilizers. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 3592–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andry, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Irie, T.; Moritani, S.; Inoue, M.; Fujiyama, H. , Water retention, hydraulic conductivity of hydrophilic polymers in sandy soil as affected by temperature and water quality. J. Hydrol. 2009, 373, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, D. R.; Akay, G.; Bilsborrow, P. E. , Development of novel polymeric materials for agroprocess intensification. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 118, 3292–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. S.; Bruulsema, T. W.; Jensen, T. L.; Fixen, P. E., Review of greenhouse gas emissions from crop production systems and fertilizer management effects. Agric., Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 133, 247-266. [CrossRef]

- Channab, B.-E.; El Idrissi, A.; Zahouily, M.; Essamlali, Y.; White, J. C. , Starch-based controlled release fertilizers: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 238, 124075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matmin, J.; Ibrahim, S. I.; Mohd Hatta, M. H.; Ricky Marzuki, R.; Jumbri, K.; Nik Malek, N. A. N. , Starch-Derived Superabsorbent Polymer in Remediation of Solid Waste Sludge Based on Water–Polymer Interaction. Polymers 2023, 15, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, B.; Elboughdiri, N.; KuShaari, K.; Jamoussi, B.; Ghernaout, D.; Ghareba, S.; Raza, S.; Gasmi, A. , Valorization of almond shells’ lignocellulosic microparticles for controlled release urea production: interactive effect of process parameters on longevity and kinetics of nutrient release. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2021, 19, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, B.; KuShaari, K.; Man, Z. B.; Basit, A.; Thanh, T. H. , Review on materials & methods to produce controlled release coated urea fertilizer. J. Control. Release 2014, 181, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Fan, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Sun, S.; Sun, R. C. , Research Progress in Lignin-Based Slow/Controlled Release Fertilizer. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4356–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Lu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Ning, P.; Liu, M., Environmentally friendly fertilizers: A review of materials used and their effects on the environment. Sci Total Environ 2018, 613-614, 829-839. [CrossRef]

- Fertahi, S.; Ilsouk, M.; Zeroual, Y.; Oukarroum, A.; Barakat, A. , Recent trends in organic coating based on biopolymers and biomass for controlled and slow release fertilizers. J. Control. Release 2021, 330, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irfan, S. A.; Razali, R.; KuShaari, K.; Mansor, N.; Azeem, B.; Ford Versypt, A. N. , A review of mathematical modeling and simulation of controlled-release fertilizers. J. Control. Release 2018, 271, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennett, T. S.; Zheng, Y. , Component characterization and predictive modeling for green roof substrates optimized to adsorb P and improve runoff quality: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrencia, D.; Wong, S. K.; Low, D. Y. S.; Goh, B. H.; Goh, J. K.; Ruktanonchai, U. R.; Soottitantawat, A.; Lee, L. H.; Tang, S. Y. , Controlled release fertilizers: A review on coating materials and mechanism of release. Plants 2021, 10, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejan, P.; Khadiran, T.; Abdullah, R.; Ahmad, N. , Controlled release fertilizer: A review on developments, applications and potential in agriculture. J. Controlled Release 2021, 339, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesołowska, M.; Rymarczyk, J.; Góra, R.; Baranowski, P.; Sławiński, C.; Klimczyk, M.; Supryn, G.; Schimmelpfennig, L. , New slow-release fertilizers—economic, legal and practical aspects: a Review. Int. Agrophys. 2021, 35, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Cheng, L.; Tan, Z. , Characteristics and preparation of oil-coated fertilizers: A review. J. Control. Release 2022, 345, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madduma-Bandarage, U. S. K.; Madihally, S. V. , Synthetic hydrogels: Synthesis, novel trends, and applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 50376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Mu, B.; Wang, Y.; Quan, Z.; Wang, A. , Synthesis, characterization, and swelling behaviors of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose-g-poly(acrylic acid)/semi-coke superabsorbent. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 935–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, S.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yin, H.; Yu, D. , Research Advances in Superabsorbent Polymers. Polymers 2024, 16, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Wen, G. , Development history and synthesis of super-absorbent polymers: a review. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, M.; Jennifer, A. , A review on starch and cellulose-enhanced superabsorbent hydrogel. J. Chem. Rev. 2023, 5, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamruzzaman, M.; Ahmed, F.; Mondal, M. I. H. , An Overview on Starch-Based Sustainable Hydrogels: Potential Applications and Aspects. J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 30, 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, R.; Wu, Z.; Xie, H.-Q.; Xu, G.-X.; Cheng, J.-S.; Zhang, B. , Preparation, characterization, and encapsulation capability of the hydrogel cross-linked by esterified tapioca starch. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, F.; Yu, H.; Wang, L.; Teng, L.; Haroon, M.; Khan, R. U.; Mehmood, S.; Bilal Ul, A.; Ullah, R. S.; Khan, A.; Nazir, A. , Advances in chemical modifications of starches and their applications. Carbohydr. Res. 2019, 476, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masina, N.; Choonara, Y. E.; Kumar, P.; du Toit, L. C.; Govender, M.; Indermun, S.; Pillay, V. , A review of the chemical modification techniques of starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, E. S.; Apopei, D. F. , Synthesis and swelling behavior of pH-sensitive semi-interpenetrating polymer network composite hydrogels based on native and modified potatoes starch as potential sorbent for cationic dyes. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 178, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkamjornwong, S.; Mongkolsawat, K.; Sonsuk, M. , Synthesis and property characterization of cassava starch grafted poly [acrylamide-co-(maleic acid)] superabsorbent via γ-irradiation. Polymer 2002, 43, 3915–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka, E.; Nowaczyk, J. , Semi-Natural Superabsorbents Based on Starch-g-poly(acrylic acid): Modification, Synthesis and Application. Polymers 2020, 12, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka, E.; Nowaczyk, J. , Synthesis and Characterization Superabsorbent Polymers Made of Starch, Acrylic Acid, Acrylamide, Poly(Vinyl Alcohol), 2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate, 2-Acrylamido-2-methylpropane Sulfonic Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordergraaf, I.-W.; Witono, J. R.; Heeres, H. J. , Grafting Starch with Acrylic Acid and Fenton’s Initiator: The Selectivity Challenge. Polymers 2024, 16, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniagor, C. O.; Afifi, M. A.; Hashem, A. , Rapid and efficient uptake of aqueous lead pollutant using starch-based superabsorbent hydrogel. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 6373–6388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supare, K.; Mahanwar, P. A. , Starch-derived superabsorbent polymers in agriculture applications: an overview. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 5795–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A.; Bhattacharia, S. K.; Kader, M. A.; Bahari, K. , Preparation and characterization of ultra violet (UV) radiation cured bio-degradable films of sago starch/PVA blend. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 63, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathy, P. C.; Jyothi, A. N., Synthesis, characterization and swelling behaviour of superabsorbent polymers from cassava starch-graft-poly(acrylamide). Starch—Starke 2012, 64, 207-218. [CrossRef]

- Amiri, F.; Kabiri, K.; Bouhendi, H.; Abdollahi, H.; Najafi, V.; Karami, Z. , High gel-strength hybrid hydrogels based on modified starch through surface cross-linking technique. Polym. Bull. 2019, 76, 4047–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhu, B.; Cao, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J., The Microstructure and Swelling Properties of Poly Acrylic Acid-Acrylamide Grafted Starch Hydrogels. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B 2016, 55, 1124-1133. [CrossRef]

- Zamani-Babgohari, F.; Irannejad, A.; Kalantari Pour, M.; Khayati, G. R. , Synthesis of carboxymethyl starch co (polyacrylamide/ polyacrylic acid) hydrogel for removing methylene blue dye from aqueous solution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 269, 132053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazoubandi, B.; Soares, J. B. P. , Amylopectin-graft-polyacrylamide for the flocculation and dewatering of oil sands tailings. Miner. Eng. 2020, 148, 106196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi-Babolan, N.; Nematollahzadeh, A.; Heydari, A.; Merikhy, A. , Bioinspired catecholamine/starch composites as superadsorbent for the environmental remediation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Aluko, R. E.; Yuan, J.; Ju, X.; He, R. , Structural and functional characterization of rice starch-based superabsorbent polymer materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 153, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siyamak, S.; Laycock, B.; Luckman, P. , Synthesis of starch graft-copolymers via reactive extrusion: Process development and structural analysis. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 227, 115066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, W.; Yu, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, D.; Zhang, R. , Effects of amylose/amylopectin ratio on starch-based superabsorbent polymers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 1583–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Yu, L.; Simon, G. P.; Shen, S.; Xie, F.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Zhong, L. , Rheokinetics of graft copolymerization of acrylamide in concentrated starch and rheological behaviors and microstructures of reaction products. Carbohydr Polym 2018, 192, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Yu, L.; Shen, S.; Simon, G. P.; Liu, H.; Chen, L. , How rheological behaviors of concentrated starch affect graft copolymerization of acrylamide and resultant hydrogel. Carbohydr Polym 2019, 219, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Saruchi; Medha; Thakur, S.; Kaith, B. S.; Sharma, N.; Ansar, S.; Pandey, S.; Kuma, V., Biopolymer starch-gelatin embedded with silver nanoparticle–based hydrogel composites for antibacterial application. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022, 12, 5363-5384. [CrossRef]

- Motamedi, E.; Motesharezedeh, B.; Shirinfekr, A.; Samar, S. M. , Synthesis and swelling behavior of environmentally friendly starch-based superabsorbent hydrogels reinforced with natural char nano/micro particles. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olad, A.; Doustdar, F.; Gharekhani, H., Fabrication and characterization of a starch-based superabsorbent hydrogel composite reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals from potato peel waste. Colloids Surf., A 2020, 601, 124962. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhang, J.; Wang, A. , Utilization of starch and clay for the preparation of superabsorbent composite. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, G. A.; Abdel-Aal, S. E.; Badway, N. A.; Abo Farha, S. A.; Alshafei, E. A., Radiation synthesis and characterization of starch-based hydrogels for removal of acid dye. Starch-Stärke 2014, 66, 400-408. [CrossRef]

- Relleve, L. S.; Aranilla, C. T.; Barba, B. J. D.; Gallardo, A. K. R.; Cruz, V. R. C.; Ledesma, C. R. M.; Nagasawa, N.; Abad, L. V. , Radiation-synthesized polysaccharides/polyacrylate super water absorbents and their biodegradabilities. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2020, 170, 108618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshii, F.; Zhao, L.; Wach, R. A.; Nagasawa, N.; Mitomo, H.; Kume, T., Hydrogels of polysaccharide derivatives crosslinked with irradiation at paste-like condition. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. B 2003, 208, 320-324. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Yoshii, F.; Kume, T.; Hashim, K. , Syntheses of PVA/starch grafted hydrogels by irradiation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2002, 50, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, M. J.; Naveed, M.; Asif, H. M.; Akhtar, R. , Irradiation applications for polymer nano-composites: A state-of-the-art review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 60, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goganian, A. M.; Hamishehkar, H.; Arsalani, N.; Khiabani, H. K. , Microwave-Promoted Synthesis of Smart Superporous Hydrogel for the Development of Gastroretentive Drug Delivery System. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2015, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naikwadi, A. T.; Sharma, B. K.; Bhatt, K. D.; Mahanwar, P. A. , Gamma Radiation Processed Polymeric Materials for High Performance Applications: A Review. Front. Chem. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Rehim, H.; Hegazy, E.-S. A.; Diaa, D. , Radiation synthesis of eco-friendly water reducing sulfonated starch/acrylic acid hydrogel designed for cement industry. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2013, 85, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapuła, P.; Bialik-Wąs, K.; Malarz, K. , Are Natural Compounds a Promising Alternative to Synthetic Cross-Linking Agents in the Preparation of Hydrogels? Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braşoveanu, M.; Nemţanu, M. R.; Duţă, D. , Electron-beam processed corn starch: evaluation of physicochemical and structural properties and technical-economic aspects of the processing. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, K.; Aggarwal, M. , Physicochemical, structural and functional properties of native and irradiated starch: a review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Moreno, V. E.; Sandoval-Pauker, C.; Aldas, M.; Ciobotă, V.; Luna, M.; Vargas Jentzsch, P.; Muñoz Bisesti, F. , Synthesis of inulin hydrogels by electron beam irradiation: physical, vibrational spectroscopic and thermal characterization and arsenic removal as a possible application. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, A. P.; Chapekar, S. , Irradiation assisted synthesis of hydrogel: A Review. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 5839–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, R. H.; Dadfarnia, S.; Shabani, A. M. H.; Moghaddam, Z. H.; Tavakol, M., Electron beam irradiation synthesis of porous and non-porous pectin based hydrogels for a tetracycline drug delivery system. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2019, 102, 391-404. [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Mohdy, H. L.; Hegazy, E. A.; El-Nesr, E. M.; El-Wahab, M. A. , Synthesis, characterization and properties of radiation-induced Starch/(EG-co-MAA) hydrogels. Arabian J. Chem. 2016, 9, S1627–S1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, M. M.; Chandra Dafader, N.; Hara, K.; Okabe, H.; Hidaka, Y.; Rahman, M. M.; Mizanur Rahman Khan, M.; Rahman, N. , Synthesis of Potato Starch-Acrylic-Acid Hydrogels by Gamma Radiation and Their Application in Dye Adsorption. International Journal of Polymer Science 2016, 2016, 9867859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, T.; Borsa, J.; Takács, E.; Wojnárovits, L. , Synthesis of carboxymethylcellulose/starch superabsorbent hydrogels by gamma-irradiation. Chem. Cent. J. 2017, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkenstadt, V. L.; Willett, J. L. , Reactive Extrusion of Starch-Polyacrylamide Graft Copolymers: Effects of Monomer/Starch Ratio and Moisture Content. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2005, 206, 1648–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, J. L.; Finkenstadt, V. L. , Initiator effects in reactive extrusion of starch-polyacrylamide graft copolymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 99, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, J. L.; Finkenstadt, V. L. , Reactive Extrusion of Starch–Polyacrylamide Graft Copolymers Using Various Starches. J. Polym. Environ. 2006, 14, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, J. L.; Finkenstadt, V. L. , Comparison of Cationic and Unmodified Starches in Reactive Extrusion of Starch–Polyacrylamide Graft Copolymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 17, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, J. L.; Finkenstadt, V. L. , Starch-poly (acrylamide-co-2-acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonic acid) graft copolymers prepared by reactive extrusion. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 42405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]