1. Introduction

The leaching of pollutants into terrestrial and aquatic environments constitutes a global concern due to the potential risks they pose to living organisms [

1,

2]. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are exogenous substances that either stimulate or inhibit endogenous hormonal responses, interfering with the reproduction and development of organisms [

3]. Most EDCs, such as atrazine, bisphenol A (BPA), triclosan, and phthalate esters, are synthetic compounds resulting from human activities [

4]. However, phytoestrogens (plant-derived) and mycoestrogens (fungi-derived) are naturally occurring substances. These synthetic compounds adversely affect organisms by inhibiting normal hormones and mimicking endogenous hormones, leading to alterations in hormone synthesis and patterns [

5,

6]. BPA and di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), both derived from plastics, are commonly used in household products, cosmetics, and medical devices [

7,

8,

9,

10]. BPA at concentration of 1 mg L

-1 induced approximately an 80% reduction in the growth rate of the marine green algae

Tetraselmis suecica [

11], wheras the survival rate of

Daphnia magna was reduced to approximately 30% when exposed to 10 mg L

-1 of BPA for 2 days [

12]. In trout, exposure to DEHP triggered a decrease in glutathione content and significantly disrupted antioxidant and immune defense functions [

13]. Although environmental EDC pollution has been linked to various adverse effects on living organisms, the impacts of EDCs on marine environments remain largely unexplored.

EDCs not only disrupt the endocrine system but also negatively affect the immune system’s ability to defend against external toxins [

14]. Immunity is a biological system that protects an organism from harmful substances, including viruses, parasites, and pathogens [

15]. In general, the immune system consists of two main components: the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system [

16]. Innate immunity is the first line of defense against invading pathogens and includes the prophenoloxidase (proPO) system, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), phagocytosis, and hemocyte nodulation [

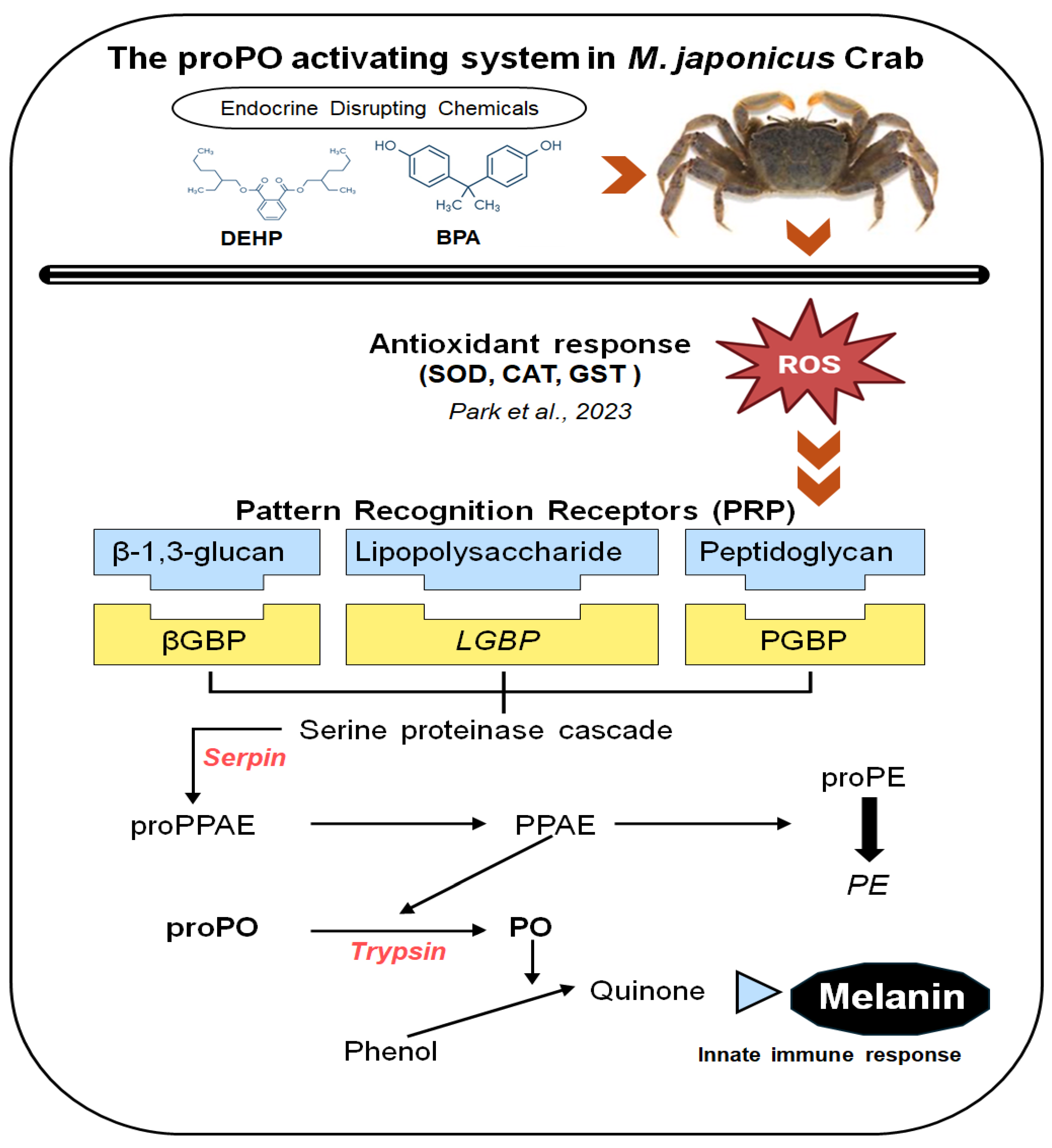

17]. The proPO system is activated by pattern recognition proteins (PRPs) that bind to β-1,3-glucans (

βGBP), lipopolysaccharides (

LGBP), and peptidoglycans (

PGBP). These PRPs activate proteinase, which triggers the serine proteinase cascade, leading to the activation of prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase (PAP). In turn, PAP converts proPO into phenoloxidase, which then synthesizes melanin [

18]. Melanin deposition is a signal response to physical tissue damage or the invasion of foreign substances in invertebrates [

19]. The proPO system includes various genes, such as serine protease inhibitor (

Serpin), trypsin-like serine protease (

Tryp), and peroxinectin (

PE) [

8]. Numerous environmental factors have been linked to changes in the immune response and the expression of genes associated with the proPO system. For example, the innate immunity of the blue mussel (

Mytilus edulis) was inhibited by changes in salinity and exposure to ZnO nanoparticles [

20]. Additionally, the antibiotic sulfamethoxazole caused decreased expression levels of innate immunity-related genes such as Janus kinase, astakine, and proPO, and reduced activities of antioxidant enzymes [

21].

Macrophthalmus japonicus is a marine benthic crab that inhabits tidal flats and is widely distributed across East Asia, including Korea, China, and Japan [

22]. These crabs typically live in burrows and feed on microorganisms or organic matter on the mud surface [

23]. Crabs living in tidal flats play a crucial role in the marine ecosystem’s food chain. Depending on their developmental stage,

M. japonicus larvae feed on rotifers, diatoms, and organic matter, providing a significant food source for higher organisms [

24,

25]. They also contribute to aeration in the mudflats through their burrowing behavior and help purify the water by consuming organic matter [

26]. Gene expression analysis is commonly used to assess the toxic effects of chemical pollutants, including EDCs. Changes in gene expression can reflect biological responses to toxicity and are identified by assessing mRNA levels of antioxidant, immune, and stress-related genes in organisms. Increased mRNA expression levels of antioxidant enzymes have been observed in

Litopenaeus vannamei exposed to polystyrene nanoplastics [

27]. Exposure to the marine pollutant phenanthrene (PHE) reduced blood cell counts and suppressed immune function in the crustacean

Scylla paramamosain [

28]. In this study, we investigated the different toxic effects of EDC exposures on the immune defense system, focusing on digestive and reproductive organs in marine organisms. Particularly, we assessed changes in the expression of innate immune proPO-related genes in the stomach and gonad of

M. japonicus exposed to BPA and DEHP at varying concentrations(

Figure 1).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Organism

M. japonicus (width: 40 ± 5 mm; height: 35 ± 5 mm; weight: 8.0 ± 2.0 g) were collected from fish markets at Suncheon Bay, South Korea. Crabs with intact claws and appendages were selected and then acclimatized with aeration at 16.0 ± 1.0 °C and a 17:7 hour light-to-dark cycle. They were fed approximately 180 mg of Tetramine (Tetra-Werke, Melle, Germany) daily. The salinity of the water tank was adjusted to 33 ± 1 psu.

2.2. Chemicals, Reagents, and Exposure Experiment Design

BPA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (99.9% purity; St. Louis, MO, USA), and DEHP was purchased from Junsei Chemical Co. Ltd. (99% purity; Tokyo, Japan). Stock solutions of BPA and DEHP were prepared at 10 mg L-1 using acetone as the solvent. These solutions were then diluted to concentrations of 1, 10, and 30 µg L-1 by mixing with artificial seawater. The crabs were divided into four groups (control and three treatment groups corresponding to 1, 10, and 30 µg L-1; n = 180). Each group was sampled for mRNA expression analysis at different time points (1, 4, and 7 days) after exposure to the three concentrations of BPA and DEHP. The experiment was conducted in triplicate.

2.3. Total RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from the gonad and stomach of control and treated crabs (30–35 mg crab-1) using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic DNA was removed using recombinant DNase I (RNase-free) (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan). The RNA concentration was measured using a Nano-Drop 1000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and nuclease-free water (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to adjust the concentration. RNA integrity was confirmed via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the samples were stored at −80 °C. For single-stranded cDNA synthesis, oligo dT primers (50 μM) and 1 μg of total RNA were used with the PrimeScriptTM 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan).

2.4. Gene Expression Quantification in M. japonicus

The mRNA expression levels of four candidate genes (

LGBP, Serpin, Tryp, and PE) in the control and treated crab groups were measured via quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) (

Table 1). The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene was used as an endogenous control for relative expression analysis. The qRT-PCR was conducted using AccuPower

® 2x GreenStar

TM qPCR Master Mix (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea) in a total volume of 20 μL, which included 5 μL of cDNA diluted 30-fold, 10 μL of 2x SYBR, 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μM), and DEPC-treated water. The qRT-PCR cycle conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 3 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95 °C, 35 seconds at 57 °C, and 20 seconds at 72 °C, with a final step for melting curve analysis (from 67 °C to 95 °C, with increments of 1 °C every 5 seconds). Relative gene expression levels were determined by normalizing the expression of the target genes to GAPDH as an internal reference gene using the 2

−ΔΔct method [

29].

2.5. Data Analysis

Statistical significance for all BPA and DEHP treatment groups was determined using R (version 4.3.1). Comparisons with the control group were conducted via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student’s t-tests. Independent t-tests were used to compare the statistical significance of mRNA expression between stomach and gonad in response to different concentrations of BPA and DEHP. Data were represented as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Expression of proPO System-Related Genes in Gonads after Exposure to EDCs

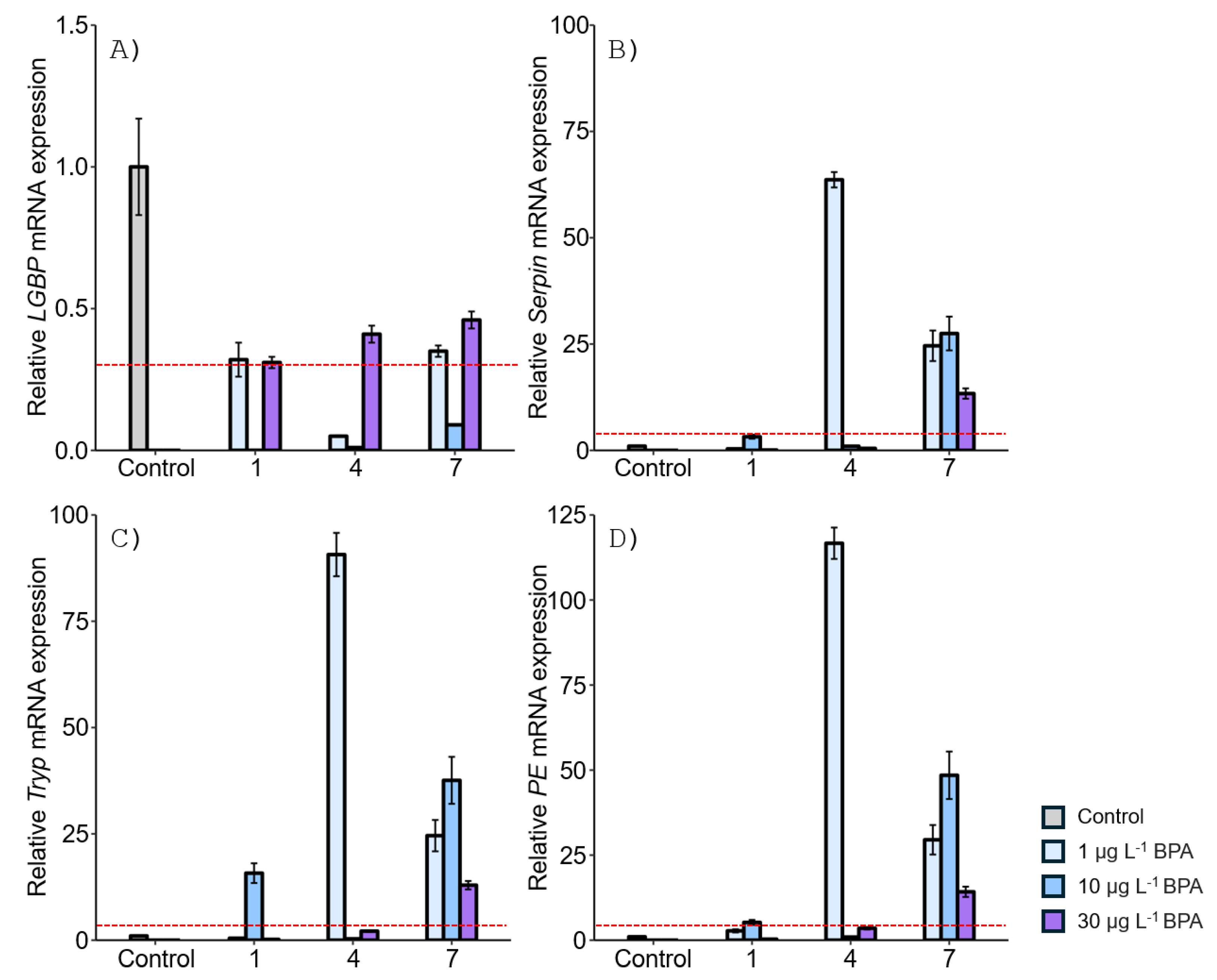

The mRNA expression levels of proPO system-related genes were examined in the gonad of M. japonicus exposed to BPA and DEHP (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). In the gonad, LGBP gene expression was significantly decreased compared to the control after exposure to all concentrations of BPA at all time points (

Figure 2A). On day 1, the lowest expression of the LGBP gene was observed at 10 μg L

-1 BPA. The decreased level of LGBP gene expression to BPA exposure increased at 4 and 7 days. Serpin gene expression was generally increased in the gonad of M. japonicus exposed to BPA (

Figure 2B). On day 4, the highest expression of the Serpin gene was observed at 1 μg L

-1 of BPA (P < 0.01). Serpin mRNA expression was upregulated at all BPA concentrations on day 7. The expression patterns of the Tryp and PE genes were similar to that of the Serpin gene (

Figure 2C and D). On day 1, Tryp gene expression was significantly increased at 1 μg L

-1 BPA, with the highest expression observed in the gonad of M. japonicus exposed to this lower concentration. On day 7, Tryp gene expression generally increased at all BPA concentrations (

Figure 2C). Additionally, the highest expression of the PE gene was observed at 1 μg L

-1 BPA, with upregulation observed at all BPA concentrations on day 7.

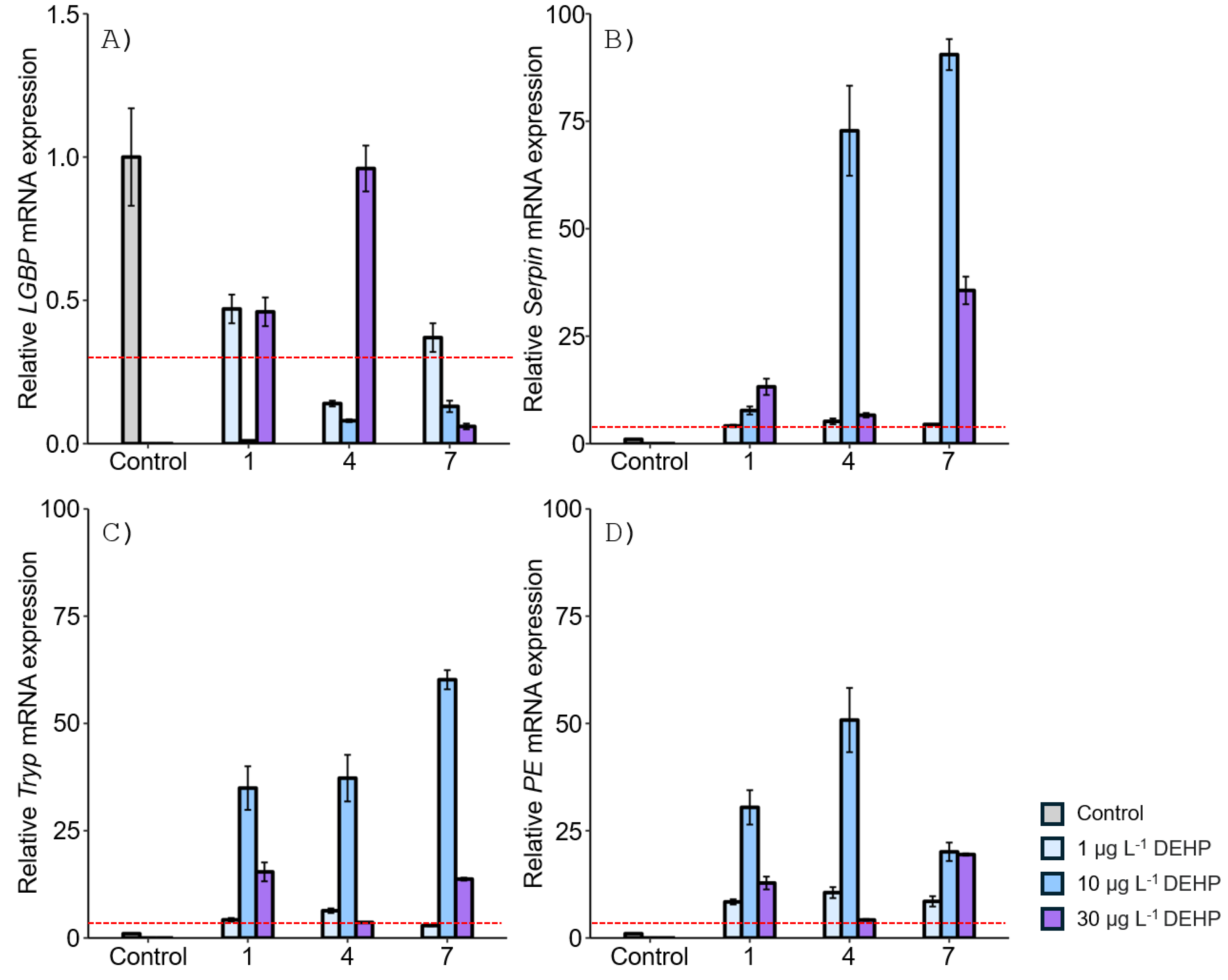

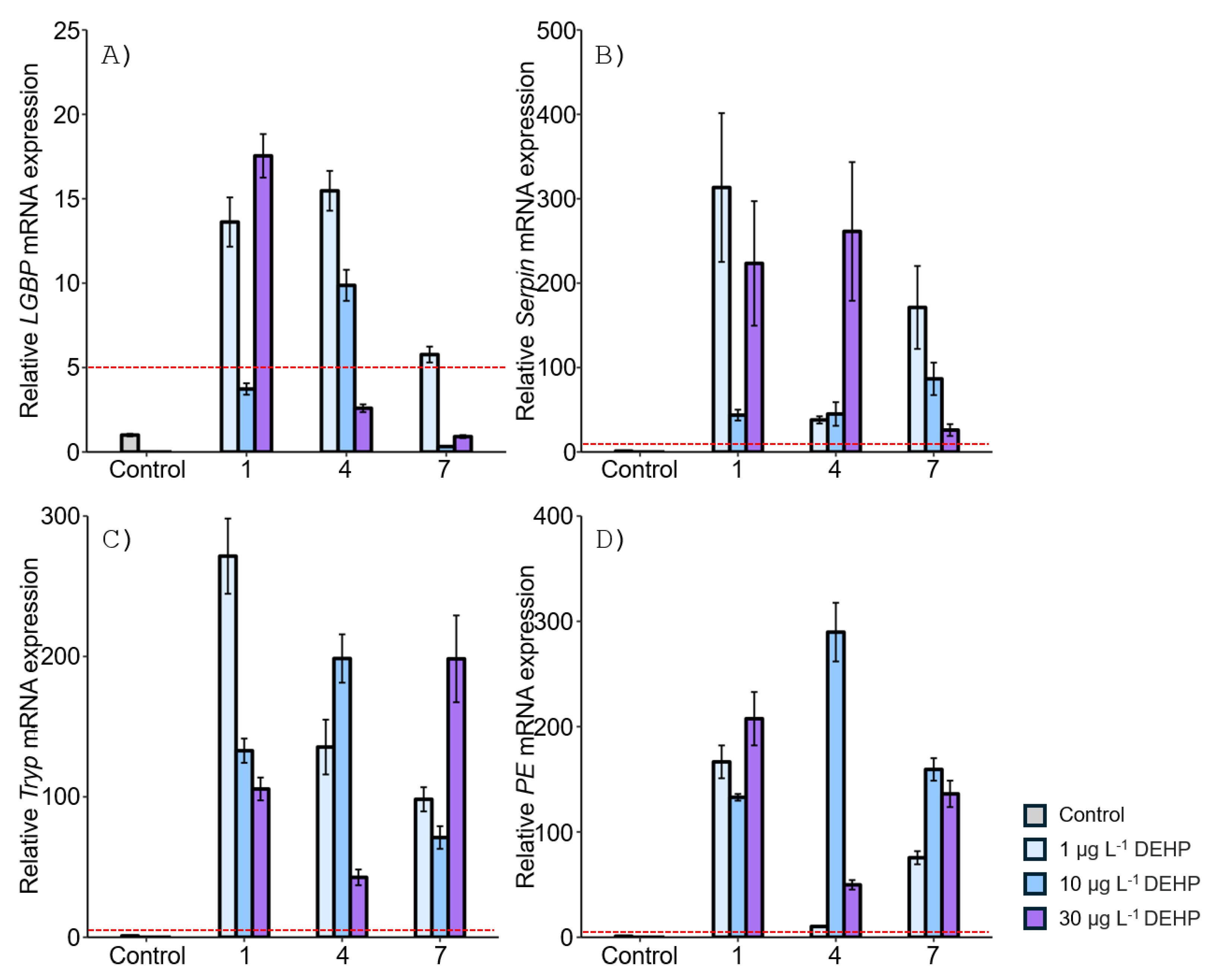

After DEHP exposure, LGBP gene expression generally decreased in the gonad of M. japonicus over 7 days compared to the control. On day 1, the lowest LGBP gene expression was observed at 10 μg L

-1 DEHP (

Figure 3A). On day 7, LGBP mRNA expression was most downregulated at the higher concentration of 30 μg L

-1 DEHP. In contrast, other proPO system-related genes, including Serpin, Tryp, and PE, showed significantly increased levels at all DEHP concentrations and exposure times (

Figure 3B-D). On day 1, Serpin gene expression increased in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 3B). On days 4 and 7, the highest Serpin expression was observed at 10 μg L

-1 DEHP, with peak expression at this concentration on day 7. Similarly, Tryp and PE were highly upregulated at 10 μg L

-1 DEHP for all exposure times (

Figure 3C and D).

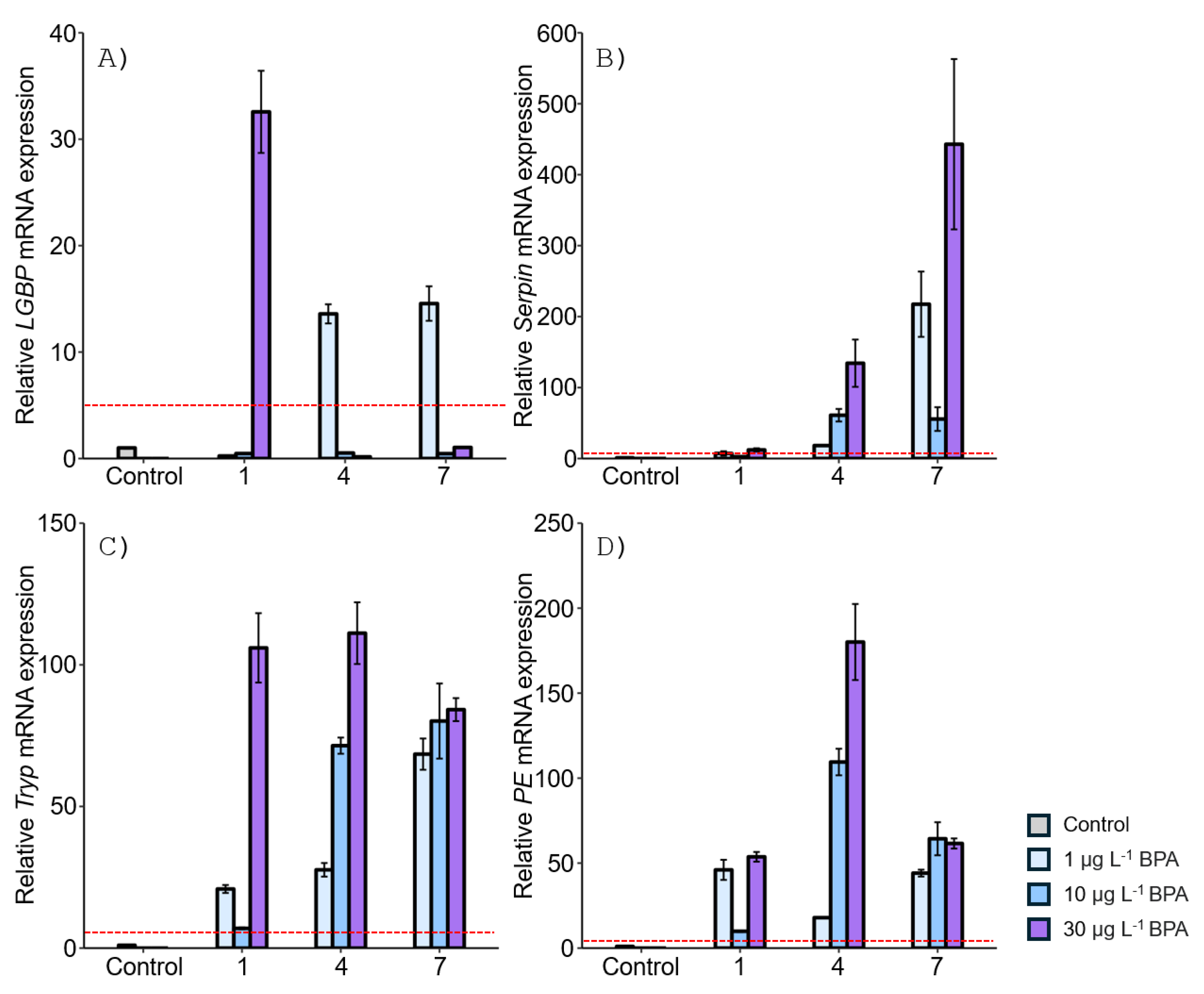

3.2. Expression of proPO System-Related Genes in the Stomach after EDC Exposure

In the stomach, the LGBP gene exhibited the highest expression (32-fold) compared to the controls after 1 day of exposure to the relatively high concentration of 30 µg L

-1 BPA (

Figure 4A). On days 4 and 7, upregulation of the LGBP gene was observed at the lower concentration of 1 µg L

-1 BPA. However, LGBP gene expression decreased at other concentrations and exposure times. The mRNA expression of Serpin generally increased at all BPA concentrations. On day 4, Serpin expression increased in an exposure time-dependent manner, with the highest expression observed at 30 µg L

-1 BPA after 7 days (

Figure 4B). Tryp gene expression also increased in the stomach of M. japonicus exposed to all concentrations of BPA across all exposure times (

Figure 4C). On days 4 and 7, Tryp expression increased in an exposure time-dependent manner. At the relatively high concentration of 30 µg L

-1 BPA, Tryp gene expression was notably elevated at all exposure times. Additionally, PE gene expression was upregulated at all concentrations of BPA for all exposure times (

Figure 4D). On day 4, PE expression increased in a dose-dependent manner, though the upregulation slightly decreased by day 7.

After DEHP exposure, LGBP gene expression increased at all concentrations after 1 day, with the highest expression (18-fold) observed in the stomach of M. japonicus exposed to 30 µg L

-1 DEHP (18-fold) (

Figure 5A). On day 4, LGBP gene upregulation was observed at all concentrations of DEHP. However, by day 7, LGBP gene expression was downregulated, becoming similar to the control after exposure to 10 and 30 µg L

-1 DEHP. Serpin gene expression generally increased at all DEHP concentrations and exposure times (

Figure 5B). On day 1, the highest Serpin expression was observed at 1 μg L

-1 DEHP compared to the control. High levels of Serpin gene expression were observed at 30 μg L

-1 DEHP after 4 days and at 1 μg L

-1 DEHP after 7 days. Tryp gene expression significantly increased at all concentrations of DEHP across all exposure times (

Figure 5C). The highest Tryp expression was observed at 1 μg L

-1 DEHP on day 1. However, Tryp upregulation was not dose-dependent. On day 7, a high level of Tryp mRNA expression was observed at the relatively high concentration of 30 μg L

-1 DEHP. PE gene expression reached its highest level on day 4 after exposure to 10 μg L

-1 DEHP, which was significantly higher compared to the control (P < 0.05) (

Figure 5D). DEHP exposure generally induced PE gene upregulation.

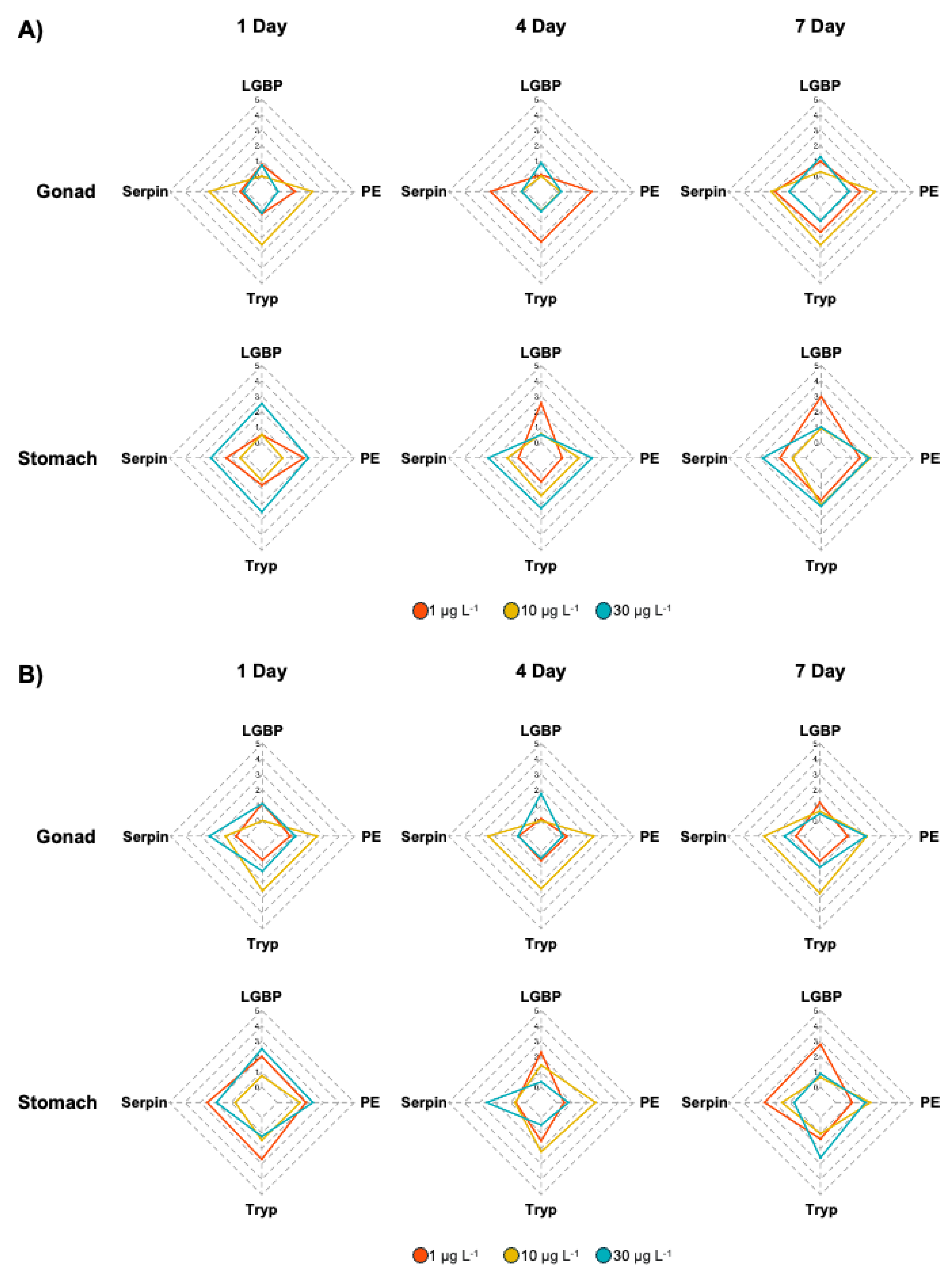

3.3. Integrated Biomarker Response (IBR) Index and Heatmap Analysis on M. japonicus Exposed to BPA and DEHP

To identify biomarkers of the toxic effects of BPA and DEHP exposure, IBR indices were calculated based on the expression levels of proPO system genes (

Figure 6), after which gene expression patterns were visualized via heatmap analysis (

Figure 7). In the BPA-exposed M. japonicus, PE expression responded to the relatively low concentration of 1 μg L

-1 BPA in both the gonad and stomach tissues on day 1 (

Figure 6A). In the gonad, the Tryp gene showed significant upregulation across all exposure times. In the stomach, proPO system-related genes responded sensitively to the relatively high concentration of 30 μg L

-1 BPA on day 1. On days 4 and 7, LGBP gene upregulation was observed at the low concentration of 1 μg L

-1 BPA, whereas Serpin gene expression was higher than that of other genes at the relatively high concentration of 30 μg L

-1 BPA. In DEHP-exposed M. japonicus, all proPO system-related genes exhibited a stronger response in the stomach compared to the gonad on day 1 (

Figure 6B). A concentration-dependent increase in Serpin IBR values was observed in the gonad 1 day after DEHP exposure, with a decrease in LGBP (IBR value: 0.45) at 7 days (

Table 2). In gonad, exposure to relatively high DEHP levels induced LGBP gene expression on day 4 and PE gene expression on day 7. At 10 μg L

-1 BPA, upregulation was observed for the Serpin, Tryp, and PE genes. In the stomach, all genes were generally expressed on day 1, with LGBP (2.50) and PE (2.31) gene levels being markedly upregulated 1 day after exposure to 30 μg L

-1 DEHP (

Table 2). However, on day 4, different expression patterns were observed at various exposure concentrations, with some genes being markedly upregulated at particular doses, including the LGBP gene at 1 μg L

-1 DEHP, PE at 10 μg L

-1 DEHP, and Serpin at 30 μg L

-1 DEHP. By day 7, the LGBP and Serpin genes responded to low levels of DEHP, whereas PE (1.91) and Tryp (2.60) responded to high levels of DEHP (

Table 2).

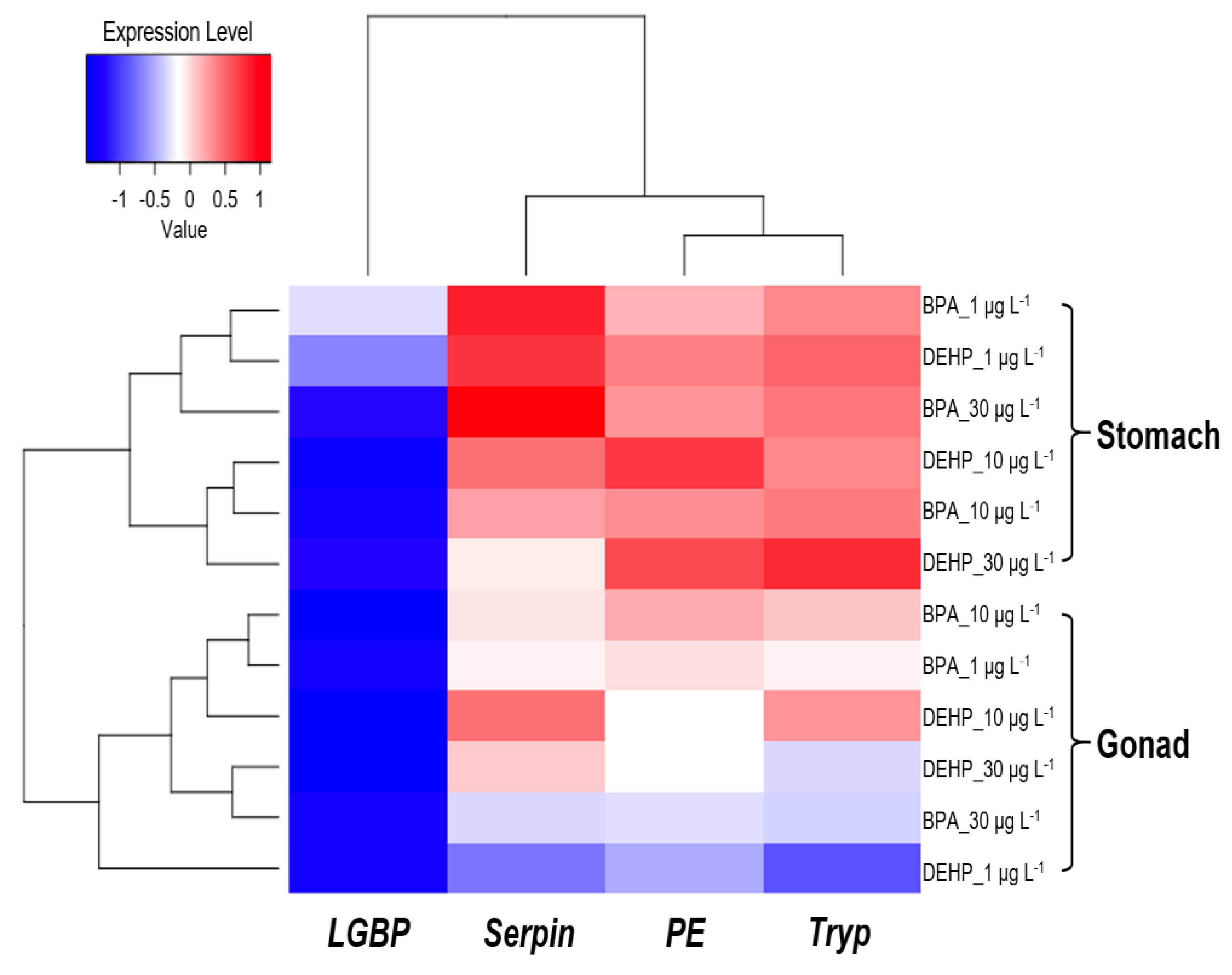

Our heatmap analyses revealed that the LGBP gene exhibited a negative correlation between exposure concentration and tissue, except for the stomach tissues of M. japonicus exposed to 1 μg L

-1 BPA and DEHP. In contrast, the Serpin, Tryp, and PE genes displayed a positive correlation in the stomach (

Figure 7). In M. japonicus crabs, proPO system-related genes responded more sensitively in the stomach than in gonad tissue. The Tryp gene expression was highly upregulated in the gonad to both exposure of BPA and DEHP. In the stomach, gene expression was more sensitively influenced by DEHP exposure compared to BPA exposure at day 1. However, the effects of BPA and DEHP on gene expression patterns were significantly different on days 4 and 7.

4. Discussion

Marine and coastal ecosystems serve as vast aquatic storage systems, acting as major sinks for pollutants originating from landscapes and freshwater sources [

30]. These ecosystems have been heavily impacted by human activities, leading to elevated levels of various contaminants in marine sediments [

31]. EDCs such as BPA and DEHP enter marine and coastal ecosystems primarily through effluents from wastewater treatment facilities (WWTF). These chemicals have been ubiquitously detected in marine biota, as well as in surface waters and sediments across all environments [

31]. EDCs are exogenous substances that can mimic or interfere with the endocrine system, causing adverse effects in organisms and altering critical biological processes, including reproduction, growth, organ development, metabolism, immunity, and behavior [

14,

32,

33,

34]. In crustaceans, EDCs can disrupt the molting process, which is vital for their growth and development [

35]. Recent studies have shown that exposure to BPA or DEHP induces oxidative stress and alters the expression of inflammation-related genes and calcium ion homeostasis genes in crabs [

35,

36]. For instance, DEHP has been shown to disrupt phagocytosis by affecting inflammatory factors in common carp [

37], whereas BPA exposure has been linked to delayed gonad development, metabolic disturbances, and endocrine disruptions in Pacific whiteleg shrimp [

38]. In marine environments, plastic materials, including plasticizers such as DEHP, BPA, and dibutyl phthalate (DBP), frequently attach to microplastics, creating a combination that is highly toxic to marine life [

39].

The potential effects of EDC exposure have been identified at the molecular level in

M. japonicus, an indicator species in coastal sediment environments. Exposure to DEHP or BPA induced alterations in the

p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (

MAPK) gene, which plays a crucial role in cellular immune and apoptotic pathways [

40]. Both exposures also resulted in changes to the histological structure and the expression of immune neurotransmitter-related genes in

M. japonicus [

41]. The innate immune system, which serves as the first line of defense in eliminating invading pathogens, is essential for regulating the activation of immune cells and maintaining control over antioxidant defense, inflammatory responses, and tissue homeostasis [

42,

43]. The cellular stress caused by immune disruption may ultimately affect epigenetic responses across generations, as innate immune cells and inflammatory processes are tightly regulated by epigenetic mechanisms [

43].

In a previous study, we reported that exposure to these EDCs altered the expression of proPO system-related genes in

M. japonicus [

8]. The present study further demonstrated that exposure to EDCs, such as BPA or DEHP, induces different expressions of innate immune proPO system-related genes depending on the tissue type in

M. japonicus. In the gonads, which are associated with reproductive function, low-level exposure to BPA or DEHP primarily triggered a transcriptional response in the

Tryp gene among the proPO system-related genes tested. In the stomach, which is related to digestive function, early exposure to DEHP caused all proPO system-related genes to respond across all concentrations, while BPA exposure elicited a response mainly at higher concentrations. At later exposure times, low-level exposure to BPA or DEHP induced a transcriptional response in the LGBP gene within the stomach of

M. japonicus. These findings suggest that the immune defense mechanisms against toxicant exposure may vary between tissues with different functions.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we observed changes in the mRNA expression of genes related to proPO system activation in the gonad and stomach of M. japonicus exposed to the EDCs BPA and DEHP. BPA exposure resulted in the upregulation of Tryp, Serpin, and PE in gonadal tissue, while it downregulated the LGBP gene. On day 1, the lowest expression of the LGBP gene in the gonad was observed at 10 μg L-1 of both BPA and DEHP. However, in the stomach, LGBP gene expression was upregulated following BPA exposure. The expression patterns of LGBP differed depending on the tissue type. The expression levels of the Serpin, Tryp, and PE genes were elevated at all concentrations of both EDCs compared to the control group. In the gonad, Serpin and Tryp were upregulated in a time-dependent manner at 10 μg L-1 DEHP. In the stomach, exposure to either BPA or DEHP induced higher expression of proPO system-related genes compared to the control group on day 1 at all concentrations. The transcriptional response to DEHP was generally higher than that to BPA. These results highlight distinct expression patterns depending on tissue type and EDC concentration. Moreover, our findings suggest that EDC exposure disrupts the immune defense system via the regulation of proPO system-activating genes.

Author Contributions

J.H. Kim carried out data curation and original draft preparation; K. Park carried out original draft preparation and reviewed and edited the paper; W.S. Kim directed the biological analyses; I.S. Kwak managed the project and edited the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2018-R1A6A1A-03024314). Additional support was provided by the Korean Environment Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through the Aquatic Ecosystem Conservation Research Program, funded by the Korean Ministry of Environment (MOE) (2021003050001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans. Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves). Please state “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Alrumman, S.; Keshk, S.; El Kott, A. Water pollution: source & treatment. Am. J. Environ. Enginner. 2016, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Morin-Crini, N.; Lichtfouse, E.; Liu, G.; Balaram, V.; Ribeiro, A.R.L.; Lu, Z.; Stock, F.; Carmona, E.; Teixeira, M.R.; Picos-Corrales, L.A.; Moreno-Piraján, J.C.; Giraldo, L.; Li, C.; Pandey, A.; Hocquet, D.; Torri, G.; Crini, G. Worldwide cases of water pollution by emerging contaminants: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2311–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.G.; Dybing, E.; Greim, H.A.; Ladefoged, O.; Lambré, C.; Tarazona, J.V.; Brandt, I.; Vethaal, A.D. Health effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on wildlife, with special reference to the European situation. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2000, 30, 71–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbre, P.D. The history of endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 2019, 7, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Kannan, K.; Tan, H.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, Y.L.; Wu, Y.; Widelka, M. Bisphenol analogues other than BPA: Environmental occurrence, human exposure, and toxicity – a review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5438–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Lee, C.J.; Mao, W.M.; Nadim, F. Identifying the potential sources of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate contamination in the sediment of the Houjing River in southern Taiwan. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowdhwal, S.S.S.; Chen, J. Toxic Effects of Di-2-ethylhexyl Phthalate: An Overview. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1750368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Kim, W.S.; Kwak, I.S. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals impair the innate immune T prophenoloxidase system in the intertidal mud crab, Macrophthalmus japonicus. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 2019, 87, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetherill, Y.B.; Akingbemi, B.T.; Kanno, J.; McLachlan, J.A.; Nadal, A.; Sonnenschein, C.; Watson, C.S.; Zoeller, R.T.; Belcher, S.M. In vitro molecular mechanisms of bisphenol A action. Reprod. Toxicol. 2007, 24, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, R.; D’Esposito, V.; Ariemma, F.; Cimmino, I.; Beguinot, F.; Formisano, P. Bisphenol A environmental exposure and the detrimental effects on human metabolic health: is it necessary to revise the risk assessment in vulnerable population? J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2016, 39, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoane, M.; Cid, Á.; Esperanza, M. Toxicity of bisphenol A on marine microalgae: Single- and multispecies bioassays based on equivalent initial cell biovolume. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 767, 144363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Yuan, S.; Li, J.; Liu, C. Greater toxic potency of bisphenol AF than bisphenol A in growth, reproduction, and transcription of genes in Daphnia magna. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 25218–25227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zeb, R.; Wei, H.; Cai, L. Acute exposure of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) induces immune signal regulation and ferroptosis in oryzias melastigma. Chemosphere. 2021, 265, 129053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.A.; Metz, L.; Yong, V.W. Review: Endocrine disrupting chemicals and immune responses: A focus on bisphenol-A and its potential mechanisms. Mol. Immunol. 2013, 53, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.G.; Li, X.B.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wu, H.; Li, K.D.; Jin, X.; Du, Y.J.; Wang, H.; Qian, F.Y.; Li, B.Z. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and autoimmune diseases. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivier, E.; Malissen, B. Innate and adaptive immunity: specificities and signaling hierarchies revisited. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amparyup, P.; Charoensapsri, W.; Tassanakajon, A. Prophenoloxidase system and its role in shrimp immune responses against major pathogens. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 2013, 34, 990–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binggeli, O.; Neyen, C.; Poidevin, M.; Lemaitre, B. Prophenoloxidase Activation Is Required for Survival to Microbial Infections in Drosophila. PLoS. Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerenius, L.; Söderhäll, K. ; The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates. Immunol. Rev. 2004, 198, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Falfushynska, H.; Delwig, O.; Piontkivska, H.; Sokolova, I.M. Interactive effects of salinity variation and exposure to ZnO nanoparticles on the innate immune system of a sentinel marine bivalve, Mytilus edulis. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 712, 136473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Jin, Q.; Zhu, F. Effects of the aquatic pollutant sulfamethoxazole on the innate immunity and antioxidant capacity of the mud crab Scylla paramamosain. Chemosphere. 2024, 349, 140775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitaura, J.; Nishida, M.; Wada, K. Genetic and behavioral diversity in the Macrophthalmus japonicus species complex (Crustacea: Brachyura: Ocypodidae). Mar. Biol. 2002, 140, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Henmi, Y. Life-history patterns in two forms of Macrophthalmus japonicus (Crustacea: Brachyura). Mar. Biol. 1989, 101, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.A.; Wille, M.; Hecht, T.; Sorgeloos, P. Optimal first feed organism for South African mud crab Scylla serrata (Forskål) larvae. Aquac. Int. 2005, 13, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, A.; Mohanty, R.K.; Mohanty, S.K.; Bhatta, K.S.; Das, N.R. Fisheries enhancement and biodiversity assessment of fish, prawn and mud crab in Chilika lagoon through hydrological intervention. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 15, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoville, A.; Lagarde, R.; Grondin, H.; Faivre, L.; Rasoanirina, E.; Teichert, N. Influence of environmental conditions on the distribution of burrows of the mud crab, Scylla serrata, in a fringing mangrove ecosystem. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 43, 101684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.L.; Hsieh, S.; Xu, R.Q.; Chen, Y.T.; Chen, C.W.; Singhania, R.R.; Chen, Y.C.; Tsai, T.H.; Dong, C.D. Toxicological effects of polystyrene nanoplastics on marine organisms on marine organisms. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 30, 103073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yifei, Y.; Zhixiong, Z.; Luna, C.; Qihui, C.; Zuoyuan, W.; Xinqi, L.; Zhexiang, L.; Fei, Z.; Xiujuan, Z. Marine pollutant Phenanthrene (PHE) exposure causes immunosuppression of hemocytes in crustacean species, Scylla paramamosain. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 275, 109761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔct method. Methods. 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avellan, A.; Duarte, A.; Rocha-Santos, T. Organic contaminants in marine sediments and seawater: A review for drawing environmental diagnostics and searching for informative predictors. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 808, 152012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, R.A.; Miralha, A.; Guimarães, T.B.; Sorrentino, R.; Calderari, M.R.; Santos, L.N. Phthalates contamination in the coastal and marine sediments of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 190, 114819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfo, A.; Nuzzo, A.M.; De Amicis, R.; Moretti, L.; Bertoli, S.; Leone, A. Fetal-Maternal Exposure to Endocrine Disruptors: Correlation with Diet Intake and Pregnancy Outcomes. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, N.; Junaid, M.; Pei, D.S. Combined toxicity of endocrine-disrupting chemicals: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 215, 112136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Flaws, J.A.; Spinella, M.J.; Irudayaraj, J. The relationship between typical environmental endocrine disruptors and kidney disease. Toxics. 2022, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, C.; Liu, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Sun, R.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C. The effects of bisphenol S exposure on the growth, physiological and biochemical indices, and ecdysteroid receptor gene expression in red swamp crayfish, Procambarus clarkii. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 276, 109811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.S.; Park, K.; Kim, J.H.; Kwak, I.S. Effect of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on the expression of a calcium ion channel receptor (ryanodine receptor) in the mud crab (Macrophthalmus japonicus). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 283, 109972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cao, Y.; Wang, S.; Cai, J.; Zhang, Z. DEHP induces immunosuppression through disturbing inflammatory factors T and CYPs system homeostasis in common carp neutrophils. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 2020, 96, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Shi, W.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Sun, H.; Zhang, J.; Yan, M.; Hu, L.; Liu, G. Microplastics and bisphenol A hamper gonadal development of whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) by interfering with metabolism and disrupting hormone regulation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 810, 152354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, V.; Chinchilla, Y.; Gómez, L.; Flores, A.; Medaglia, A.; Guillén, R.; Montero, E. Human health risk assessment for consumption of microplastics and plasticizing substances through marine species. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 116843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Kim, W.S.; Choi, B.; Kwak, I.S. Expression levels of the immune-related p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase transcript in response to environmental pollutants on Macrophthalmus japonicus crab. Genes. 2020, 11, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.S.; Kwak, I.S. EDCs trigger immune-neurotransmitter related gene expression, and cause histological damage in sensitive mud crab Macrophthalmus japonicus gills and hepatopancreas. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 2022, 122, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, T.; Mukai, K. Innate immunity signalling and membrane trafficking. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 2019, 59, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Winther, M.P.; Palaga, T. Epigenetic Regulation of Innate Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 713758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the innate immune prophenoloxidase (proPO) activation system in M. japonicus after exposure to EDCs, including BPA and DEHP. PE: Peroxinectin; proPE: Properoxinectin; PPAE: proPO-activating enzyme; proPPAE: proproPO-activating enzyme. Italicized letters indicate the genes tested in the proPO system in this study.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the innate immune prophenoloxidase (proPO) activation system in M. japonicus after exposure to EDCs, including BPA and DEHP. PE: Peroxinectin; proPE: Properoxinectin; PPAE: proPO-activating enzyme; proPPAE: proproPO-activating enzyme. Italicized letters indicate the genes tested in the proPO system in this study.

Figure 2.

Relative mRNA expression levels of four proPO-related genes in the M. japonicus gonad exposed to 1, 10, and 30 μg L-1 BPA. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. mRNA expression levels of each gene were normalized against GAPDH. The red dotted line indicates significantly regulated values compared to the control.

Figure 2.

Relative mRNA expression levels of four proPO-related genes in the M. japonicus gonad exposed to 1, 10, and 30 μg L-1 BPA. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. mRNA expression levels of each gene were normalized against GAPDH. The red dotted line indicates significantly regulated values compared to the control.

Figure 3.

Relative mRNA expression levels of four proPO-related genes in the M. japonicus gonad exposed to 1, 10, and 30 μg L-1 DEHP. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. mRNA expression levels of each gene were normalized against GAPDH. The red dotted line indicates significantly regulated values compared to the control.

Figure 3.

Relative mRNA expression levels of four proPO-related genes in the M. japonicus gonad exposed to 1, 10, and 30 μg L-1 DEHP. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. mRNA expression levels of each gene were normalized against GAPDH. The red dotted line indicates significantly regulated values compared to the control.

Figure 4.

Relative mRNA expression levels of four proPO-related genes in the M. japonicus stomach exposed to 1, 10, and 30 μg L-1 BPA. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. mRNA expression levels of each gene were normalized against GAPDH. The red dotted line indicates significantly regulated values compared to the control.

Figure 4.

Relative mRNA expression levels of four proPO-related genes in the M. japonicus stomach exposed to 1, 10, and 30 μg L-1 BPA. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. mRNA expression levels of each gene were normalized against GAPDH. The red dotted line indicates significantly regulated values compared to the control.

Figure 5.

Relative mRNA expression levels of four proPO-related genes in the M. japonicus stomach exposed to 1, 10, and 30 μg L-1 DEHP. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. mRNA expression levels of each gene were normalized against GAPDH. The red dotted line indicates significantly regulated values compared to the control.

Figure 5.

Relative mRNA expression levels of four proPO-related genes in the M. japonicus stomach exposed to 1, 10, and 30 μg L-1 DEHP. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. mRNA expression levels of each gene were normalized against GAPDH. The red dotted line indicates significantly regulated values compared to the control.

Figure 6.

Star plot of IBR values for evaluating gene responses in the M. japonicus gonad and stomach exposed to BPA (A) and DEHP (B).

Figure 6.

Star plot of IBR values for evaluating gene responses in the M. japonicus gonad and stomach exposed to BPA (A) and DEHP (B).

Figure 7.

Heatmap of the relative expression levels in the M. japonicus gonad and stomach after exposure to 1, 10, and 30 μg L-1 BPA and DEHP on days 1, 4, and 7. Down-regulated expression (<0) is indicated in blue, while up-regulated expression (>0) is indicated in red. Data from each exposure group were subjected to log transformation.

Figure 7.

Heatmap of the relative expression levels in the M. japonicus gonad and stomach after exposure to 1, 10, and 30 μg L-1 BPA and DEHP on days 1, 4, and 7. Down-regulated expression (<0) is indicated in blue, while up-regulated expression (>0) is indicated in red. Data from each exposure group were subjected to log transformation.

Table 1.

Primers used for proPO-related gene amplification in this study.

Table 1.

Primers used for proPO-related gene amplification in this study.

| Gene |

Primer Sequence (5’-3’) |

Amplicon size (bp) |

Efficiency (%) |

Accession number |

| LGBP_F |

AATGGCTTCTTCCCTGACGG |

131 |

100.0 |

KJ653260 |

| LGBP_R |

CTGATCTTGCCCTCACCCTG |

|

|

|

| Serpin_F |

TTTGGAACGTGGGAGTATGC |

74 |

93.0 |

MH41109 |

| Serpin_R |

TGCACATTGGGAATCGCATG |

|

|

|

| Tryp_F |

CCTAGAGGTCGGGGTCAAGA |

91 |

99.5 |

KJ653261 |

| Tryp_R |

CCTATCCAGCTCGAGCAGTG |

|

|

|

| PE_F |

CTGACCACCATACACACGCT |

98 |

90.0 |

KF804082 |

| PE_R |

TGGAACACTTGCTCGTCCTG |

|

|

|

| GAPDH_F |

TGCTGATGCACCCATGTTTG |

147 |

102.5 |

KJ653265 |

| GAPDH_R |

AGGCCCTGGACAATCTCAAAG |

|

|

|

Table 2.

IBR index for evaluating gene responses in gonad and stomach tissues of M. japonicus exposed to 1, 10, and 30 μg L-1 BPA and DEHP.

Table 2.

IBR index for evaluating gene responses in gonad and stomach tissues of M. japonicus exposed to 1, 10, and 30 μg L-1 BPA and DEHP.

| Chemical |

Organ |

Concentration (μg/L) |

proPO system related gene |

IBR value |

| LGBP |

Serpin |

Tryp |

PE |

Mean |

| BPA |

Gonad |

Control |

2.67 |

0.00 |

0.15 |

0.20 |

0.75 |

2.45 |

| |

|

1 |

0.96 |

1.96 |

1.65 |

1.60 |

1.54 |

1.17 |

| |

|

10 |

0.29 |

2.20 |

2.48 |

2.53 |

1.87 |

4.31 |

| |

|

30 |

1.25 |

1.03 |

0.91 |

0.85 |

1.01 |

2.61 |

| |

Stomach |

Control |

1.00 |

0.58 |

0 |

0.05 |

0.41 |

0.46 |

| |

|

1 |

2.98 |

1.67 |

1.74 |

1.52 |

1.98 |

1.38 |

| |

|

10 |

0.92 |

0.85 |

2.04 |

2.22 |

1.51 |

3.90 |

| |

|

30 |

1.01 |

2.81 |

2.14 |

2.12 |

2.02 |

4.24 |

| DEHP |

Gonad |

Control |

2.65 |

0.46 |

0.56 |

0 |

0.92 |

2.58 |

| |

|

1 |

1.17 |

0.54 |

0.63 |

0.82 |

0.79 |

1.35 |

| |

|

10 |

0.63 |

2.62 |

2.69 |

2.08 |

2.00 |

1.93 |

| |

|

30 |

0.45 |

1.29 |

1.02 |

2.01 |

1.19 |

3.78 |

| |

Stomach |

Control |

0.90 |

0.37 |

0.18 |

0 |

0.37 |

0.34 |

| |

|

1 |

2.79 |

2.62 |

1.37 |

1.05 |

1.96 |

1.31 |

| |

|

10 |

0.64 |

1.50 |

1.04 |

2.24 |

1.35 |

3.40 |

| |

|

30 |

0.87 |

0.70 |

2.60 |

1.91 |

1.52 |

2.97 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).