Submitted:

12 September 2024

Posted:

13 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

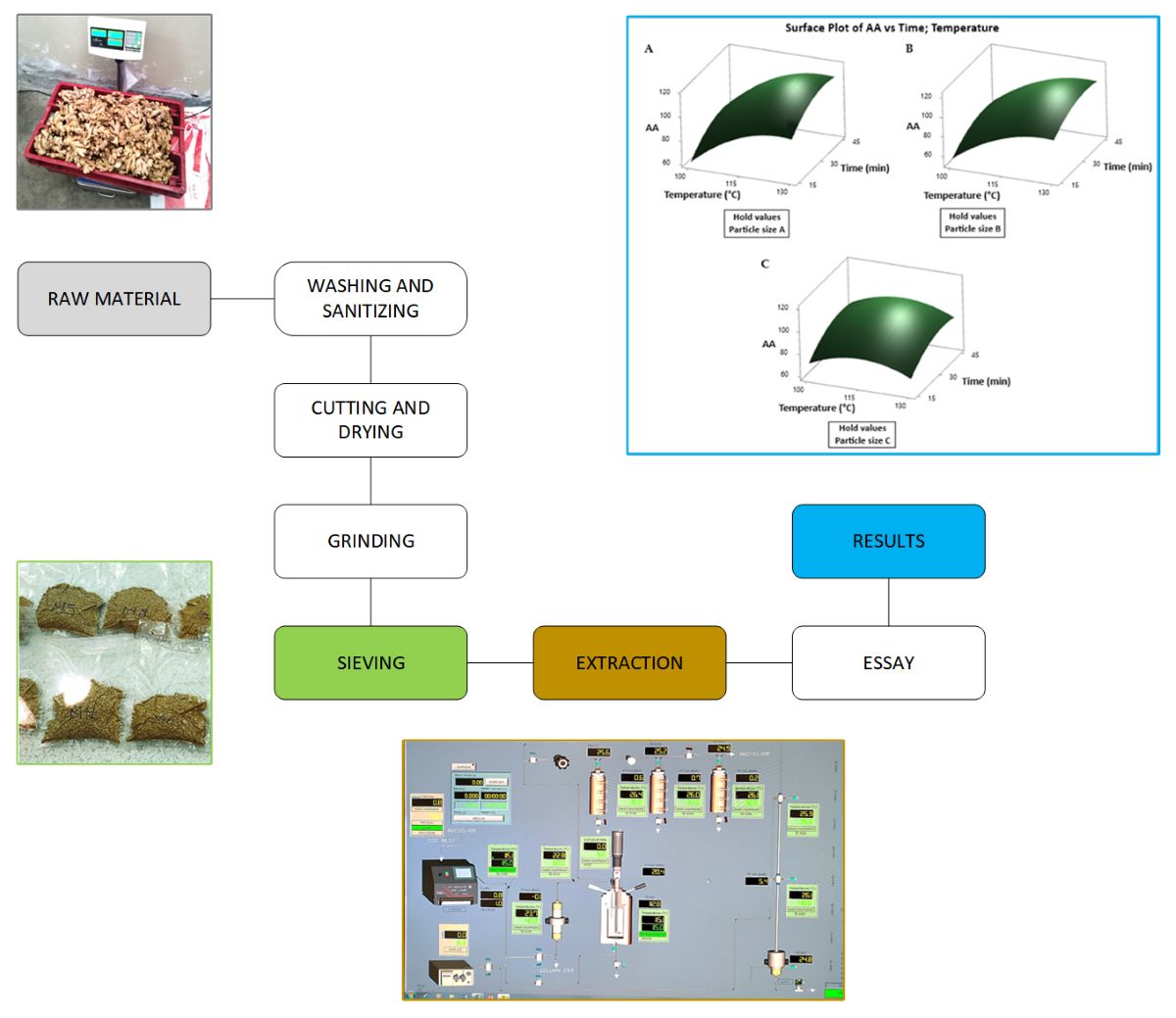

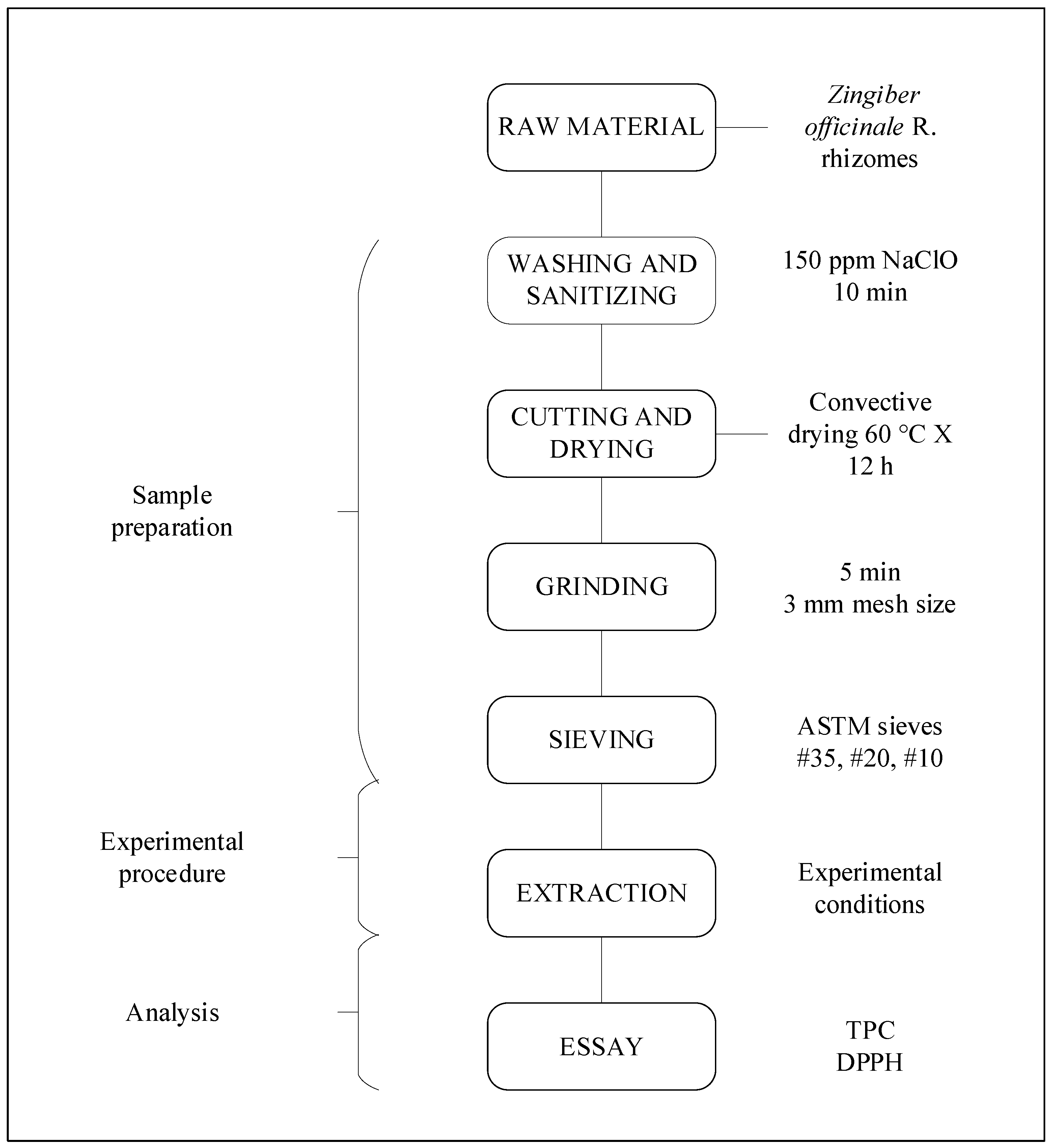

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sample

2.3. Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE)

2.3.1. Step 1: Loading the Extraction Cell in the Extractor

2.3.2. Step 2: Establishing Operating Conditions

2.3.3. Step 3: Operation and Control

2.3.4. Step 4: Extract Discharge

2.4. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) Assay

2.5. Antioxidant Activity (AA) Assay

2.6. Experimental Design

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Extraction, TPC and AA Essay Results

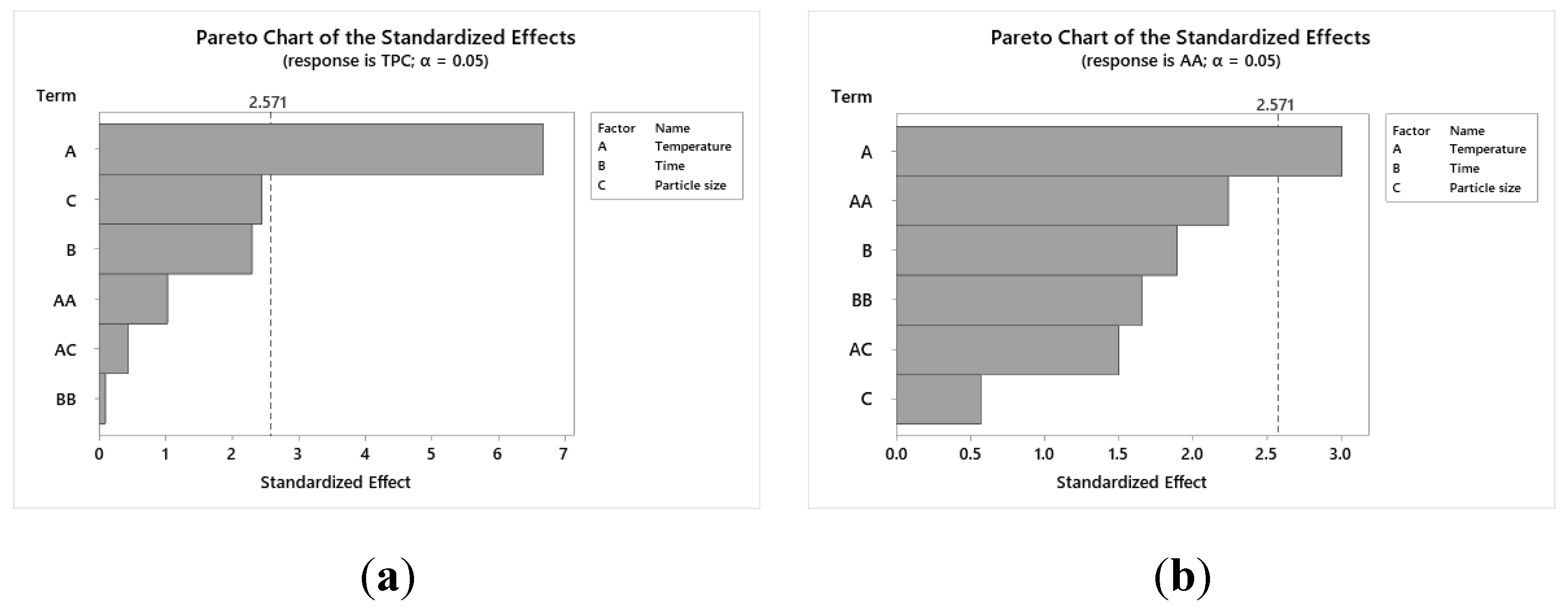

3.2. TPC and AA Responses ANOVA

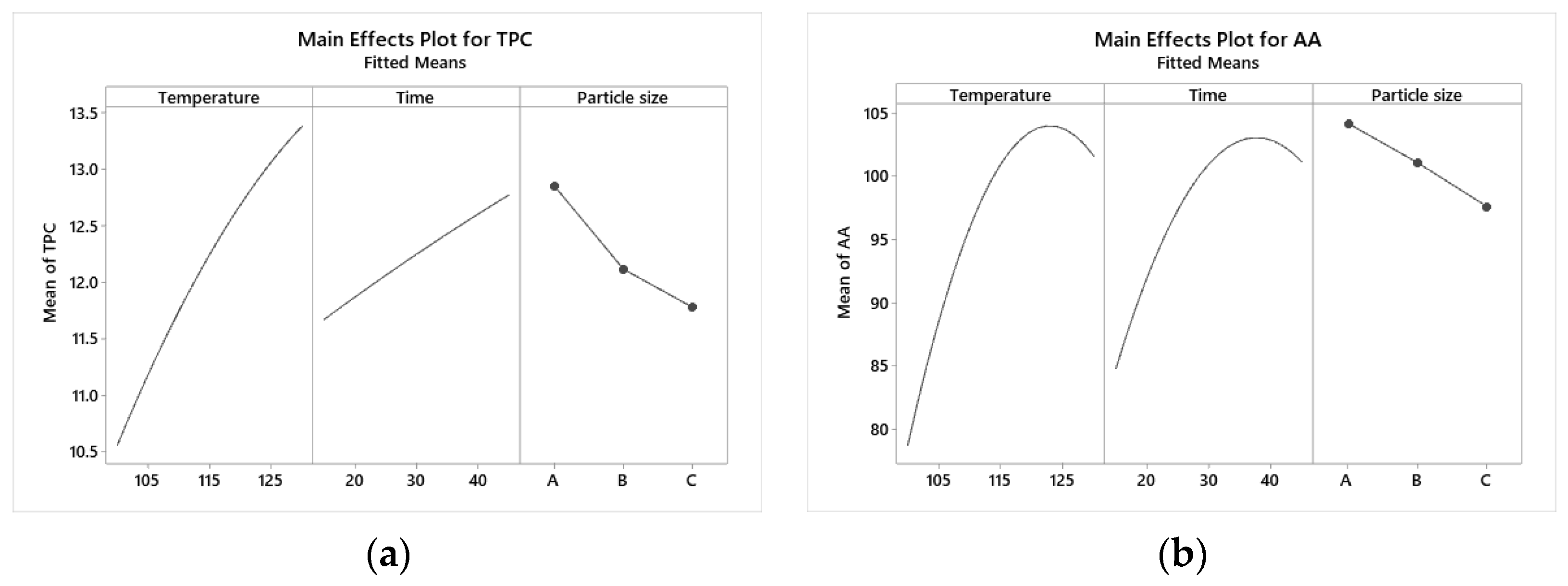

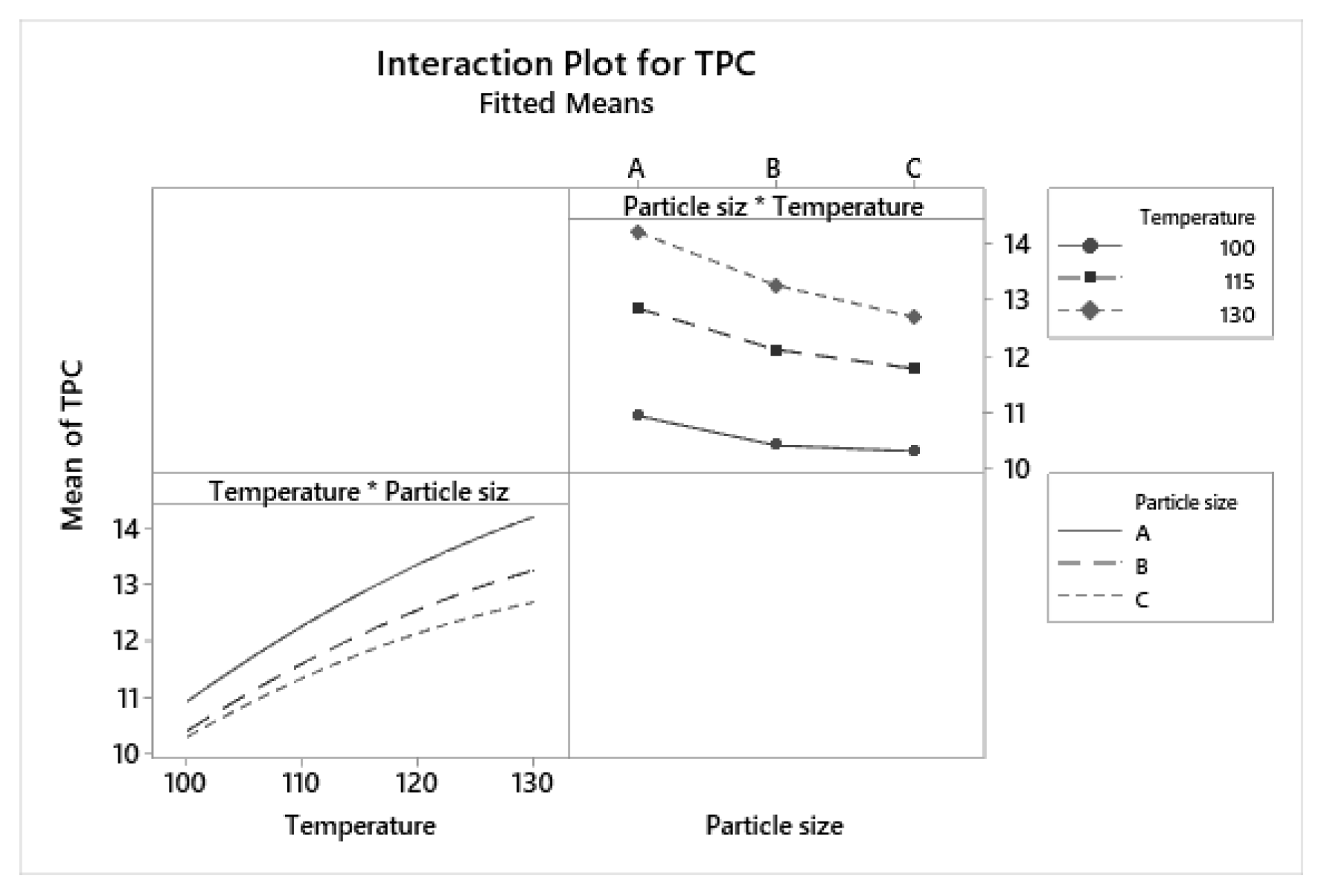

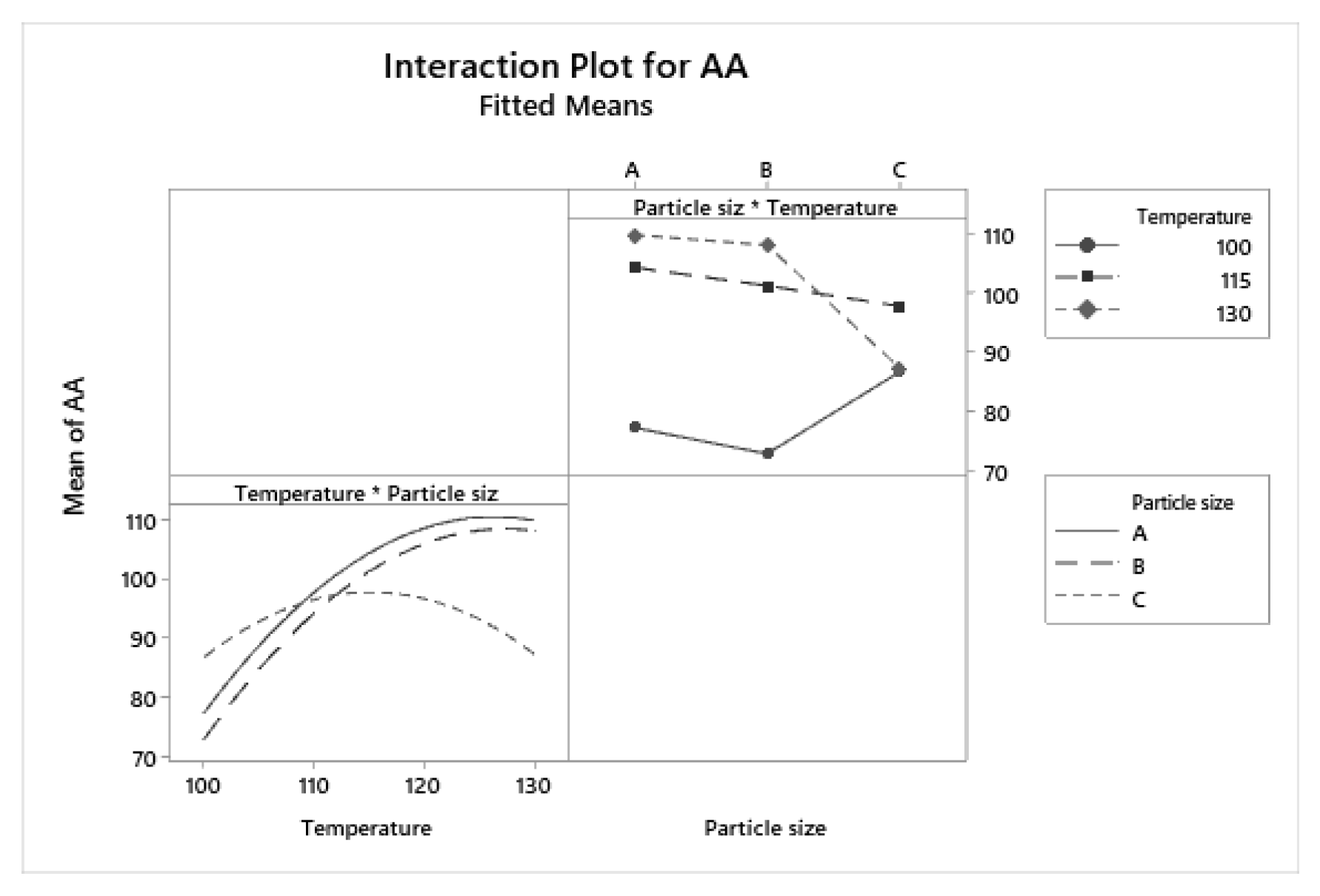

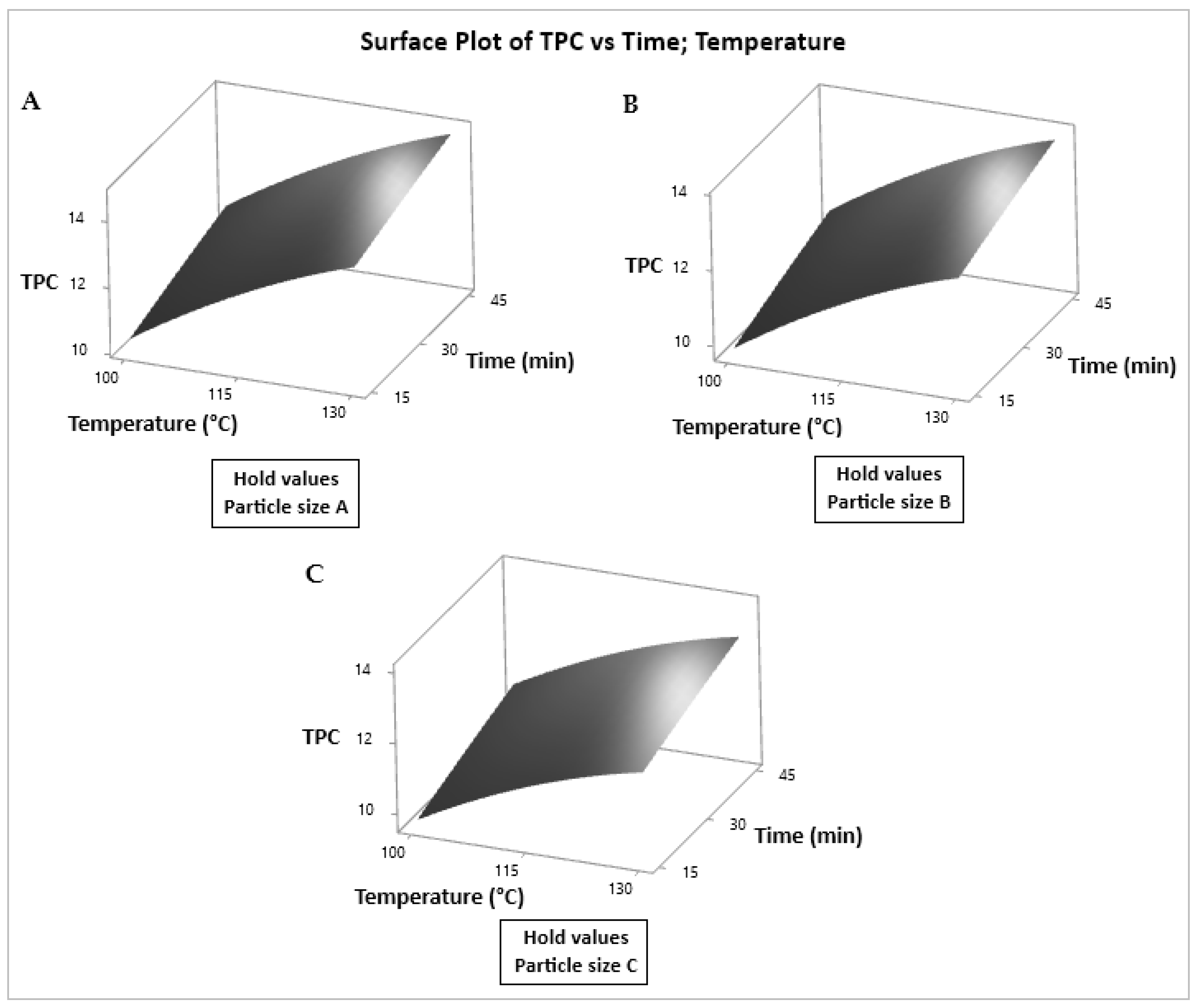

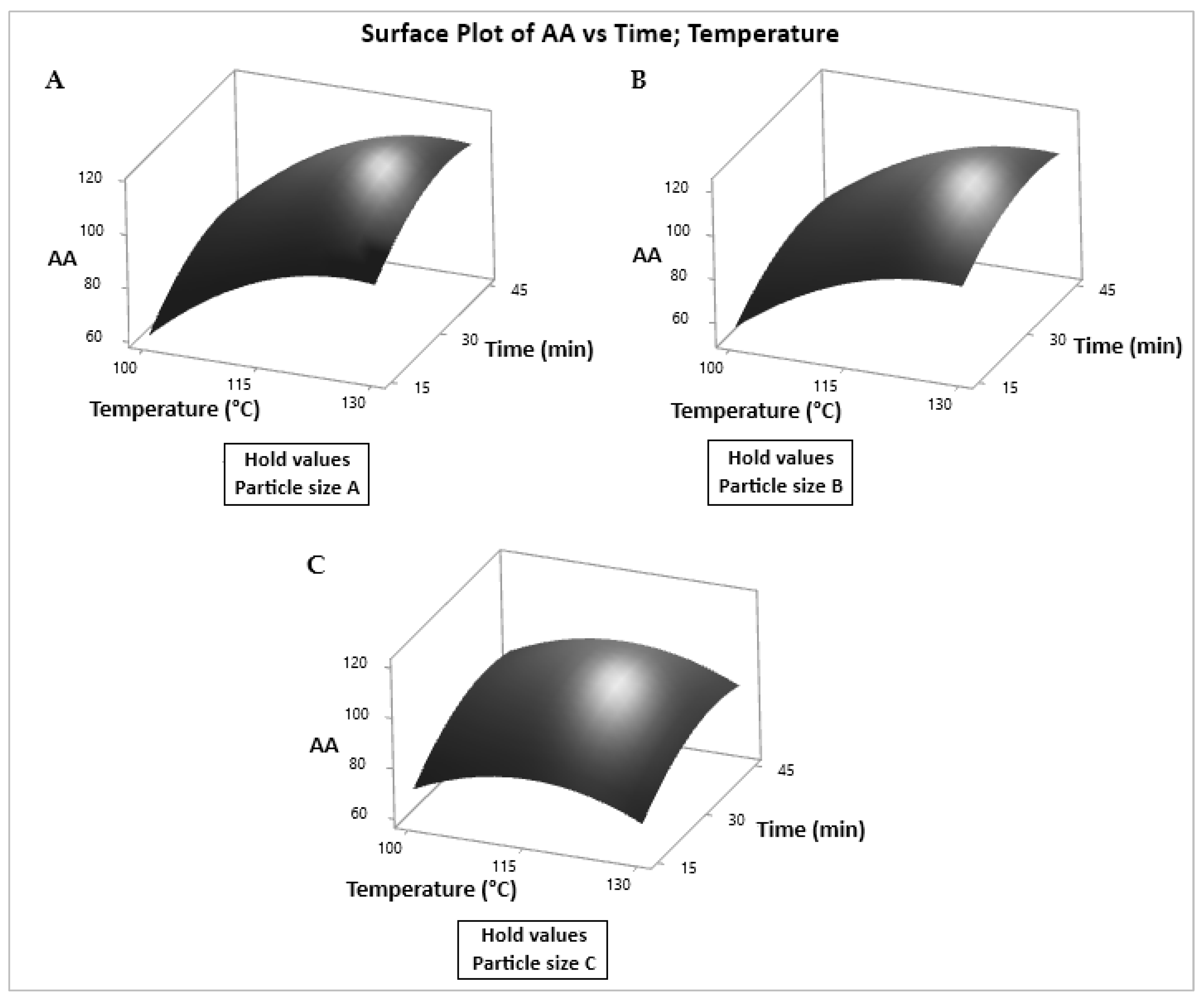

3.3. TPC and AA Responses Graphical Analysis

3.4. TPC and AA Correlation

3.5. Response Optimization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sulejmanović, M.; Milić, N.; Mourtzinos, I.; Nastić, N.; Kyriakoudi, A.; Drljača, J.; Vidović, S. Ultrasound-assisted and subcritical water extraction techniques for maximal recovery of phenolic compounds from raw ginger herbal dust toward in vitro biological activity investigation. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz-Turan, S.; Gál, T.; Lopez-Sanchez, P.; Martinez, M.M.; Menzel, C.; Vilaplana, F. Modulating temperature and pH during subcritical water extraction tunes the molecular properties of apple pomace pectin as food gels and emulsifiers. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 145, 109148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Moreira, M.M.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Sarraguça, M. Subcritical water extraction to valorize grape biomass—A step closer to circular economy. Molecules 2023, 28, 7538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulzar, R.; Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Samar, N.; Shahbaz, A.; Ateeq, H.; Farooq, M.U.; Akram, N.; Asghar, A.; Rasheed, A.; Teferi Asres, D. Bio valorization and industrial applications of ginger waste: a review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 2772–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ozel, M.Z.; Dugmore, T.; Sulaeman, A.; Matharu, A.S. A biorefinery strategy for spent industrial ginger waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.-J.; Nam, H.-H.; Chung, M.-S. Conversion of 6-gingerol to 6-shogaol in ginger (Zingiber officinale) pulp and peel during subcritical water extraction. Food Chem. 2019, 270, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimone, C.; Calcio Gaudino, E.; Brncic, M.; Barba, F.J.; Grillo, G.; Cravotto, G. Sorbus spp. berries extraction in subcritical water: Bioactives recovery and antioxidant activity. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xue, F.; Yu, S.; Du, S.; Yang, Y. Subcritical water extraction of natural products. Molecules 2021, 26, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, P.; Gruba, M.; Fekner, Z.; Tyśkiewicz, K.; Kobus, Z. The influence of water extraction parameters in subcritical conditions and the shape of the reactor on the quality of extracts obtained from Norway maple (Acer platanoides L.). Processes 2023, 11, 3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, P.A.V.; Martín-Pérez, L.; Gil-Guillén, I.; González-Martínez, C.; Chiralt, A. Subcritical water extraction for valorisation of almond skin from almond industrial processing. Foods 2023, 12, 3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibekov, R.S.; Mustapa Kamal, S.M.; Taip, F.S.; Sulaiman, A.; Azimov, A.M.; Urazbayeva, K.A. Recovery of phenolic compounds from jackfruit seeds using subcritical water extraction. Foods 2023, 12, 3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endy Yulianto, M.; Paramita, V.; Amalia, R.; Wahyuningsih, N.; Dwi Nyamiati, R. Production of bioactive compounds from ginger (Zingiber officianale) dregs through subcritical water extraction. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 63, S188–S194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Vieira, E.F.; Peixoto, A.F.; Freire, C.; Freitas, V.; Costa, P.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F. Optimizing the extraction of phenolic antioxidants from chestnut shells by subcritical water extraction using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2021, 334, 127521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigueros, E.; Benito-Román, Ó.; Oliveira, A.P.; Videira, R.A.; Andrade, P.B.; Sanz, M.T.; Beltrán, S. Onion (Allium cepa L.) skin waste valorization: Unveiling the phenolic profile and biological potential for the creation of bioactive agents through subcritical water extraction. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudjito, R.C.; Matute, A.C.; Jiménez-Quero, A.; Olsson, L.; Stringer, M.A.; Krogh, K.B.R.M.; Eklöf, J.; Vilaplana, F. Integration of subcritical water extraction and treatment with xylanases and feruloyl esterases maximises release of feruloylated arabinoxylans from wheat bran. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 395, 130387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, R.; Hai, A.; Banat, F. Subcritical water extraction of mango seed kernels and its application for cow ghee preservation. Processes 2023, 11, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.G.; Gomes-Dias, J.S.; Pereira, R.N.; Teixeira, J.A.; Rocha, C.M.R. Innovative processing technology in agar recovery: Combination of subcritical water extraction and moderate electric fields. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 84, 103306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.P.; Ferreira-Santos, P.; Lopes, G.R.; Reis, S.F.; González, A.; Nobre, C.; Freitas, V.; Coimbra, M.A.; Coelho, E. Industrial byproduct pine nut skin factorial design optimization for production of subcritical water extracts rich in pectic polysaccharides, xyloglucans, and phenolic compounds by microwave extraction. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabalak, E.; Aminzai, M.T.; Gizir, A.M.; Yang, Y. A review: Subcritical water extraction of organic pollutants from environmental matrices. Molecules 2024, 29, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalhan, S.D.; Meryemoğlu, B.; Eroğlu, P.; Saçlı, B.; Kalderis, D. Subcritical water extraction of Onosma mutabilis: Process optimization and chemical profile of the extracts. Molecules 2023, 28, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga-Sánchez, M.; Rosales-Hartshorn, M. Effects of subcritical water extraction and cultivar geographical location on the phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of Quebranta (Vitis vinifera) grape seeds from the Peruvian pisco industry by-product. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e107321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-K.; Noh, J.; Lee, S.; Choi, J.-S.; Suh, H.; Chung, H.-Y.; Song, Y.-O.; Choi, W.-C. The first total synthesis of 2,3,6-tribromo-4,5-dihydroxybenzyl methyl ether (TDB) and its antioxidant activity. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2002, 23, 661–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh Amiri, Z.; Najafpour, G.D.; Mohammadi, M.; Moghadamnia, A.A. Subcritical Water Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Int. J. Eng. 2018, 31, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-W.; Lin, L.-G.; Ye, W.-C. Techniques for extraction and isolation of natural products: a comprehensive review. Chin. Med. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siti Nur Khairunisa, M.A.; Mad Nordin, M.F.; Shameli, K.; Mohamad Abdul Wahab, I.; Abdul Hamid, M. Evaluation of parameters for subcritical water extraction of Zingiber zerumbet using fractional factorial design. J. Teknol. 2021, 83, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Gonzales, G. , Castro-Rumiche, C., Alvarez-Guzman, G., Flores-García, J., & Barriga-Sánchez, M. Compuestos fenólicos y actividad antioxidante de los extractos de la hoja de chirimoya (Annona cherimola Mill). Rev. Colomb. Quím. 2019, 48, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beristain-Bauza, S.D.; Hernández-Carranza, P.; Cid-Pérez, T.S.; Ávila-Sosa, R.; Ruiz-López, I.I.; Ochoa-Velasco, C.E. Antimicrobial Activity of Ginger (Zingiber officinale) and Its Application in Food Products. Food Rev. Int. 2019, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.-Q.; Xu, X.-Y.; Cao, S.-Y.; Gan, R.-Y.; Corke, H.; Beta, T.; Li, H.-B. Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods 2019, 8, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-López, E.; Castañeda-Ovando, A.; Jaimez-Ordaz, J.; Cruz-Cansino, N. del S.; González-Olivares, L.G.; Rodríguez-Martínez, J.S.; Ramírez-Godínez, J. Release of antioxidant compounds of Zingiber officinale by ultrasound-assisted aqueous extraction and evaluation of their in vitro bioaccessibility. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge-Montalvo, P.; Vílchez-Perales, C.; Visitación-Figueroa, L. Evaluation of antioxidant capacity, structure, and surface morphology of ginger (Zingiber officinale) using different extraction methods. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmudati, N.; Wahyono, P.; Djunaedi, D. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of three varieties of Ginger (Zingiber officinale) in decoction and infusion extraction method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1567, 22028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.; Norton, E.; Montgomery, F.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols from Ginger (Zingiber officinale) and Evaluation of its Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties. J. Food Chem. Nanotechnol. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, A.M.; Zakaria, S.N.A.; Abdul Sani, N.F.; Ab Rani, N.; Hakimi, N.H.; Mohd Said, M.; Tan, J.K.; Gan, H.K.; Mad Nordin, M.F.; Makpol, S. A subcritical water extract of soil grown Zingiber officinale Roscoe: Comparative analysis of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects and evaluation of bioactive metabolites. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, N.; Nordin, M.F.M.; Morad, N. Total Phenolic Content, Total Flavonoid Content and Radical Scavenging Activity from Zingiber zerumbet Rhizome using Subcritical Water Extraction. Int. J. Eng. 2018, 31, 1421–1429. https://www.ije.ir/article_73263_a2c983d8d7e9dd24f79c6eb632e9a19e.pdf.

- Siti Nur Khairunisa, M.A.; Mad Nordin, M.F.; Shameli, K.; Mohamad Abdul Wahab, I.; Abdul Hamid, M. Modeling and optimization of pilot-scale subcritical water extraction on Zingiber zerumbet by central composite design. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 778, 12077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thepthong, P.; Rattakarn, K.; Ritchaiyaphum, N.; Intachai, S.; Chanasit, W. Effect of extraction solvents on antioxidant and antibacterial activity of Zingiber montanum rhizomes. ASEAN J. Sci. Technol. Rep. 2023, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazyan, W.I.; O’Connor, E.; Martin, E.; Vogt, A.; Charter, E.; Ahmadi, A. Effects of temperature and extraction time on avocado flesh (Persea americana) total phenolic yields using subcritical water extraction. Processes 2021, 9, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SampleExtracts | Conditions | Responses 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | Time (min) | Particle size (μm) 1 | TPC (mg GAE/g sample) | AA (μmol TE/g sample) | |||

| M1 | 100 | 15 | B | 10.84 | 11.28 | 117.46 | 117.90 |

| M2 | 115 | 30 | B | 11.27 | 10.89 | 111.94 | 112.02 |

| M3 | 115 | 30 | B | 12.43 | 12.76 | 106.70 | 104.83 |

| M4 | 100 | 30 | C | 10.29 | 10.42 | 89.80 | 89.53 |

| M5 | 115 | 30 | B | 12.16 | 12.32 | 98.19 | 98.87 |

| M6 | 115 | 45 | A | 13.22 | 13.45 | 107.85 | 109.16 |

| M7 | 130 | 30 | A | 13.73 | 14.10 | 106.52 | 106.12 |

| M8 | 130 | 15 | B | 12.68 | 12.36 | 91.83 | 91.66 |

| M9 | 115 | 45 | C | 12.53 | 12.23 | 94.33 | 93.99 |

| M10 | 115 | 15 | A | 12.06 | 12.40 | 90.98 | 95.68 |

| M11 | 130 | 30 | C | 12.93 | 12.79 | 90.36 | 90.26 |

| M12 | 100 | 45 | B | 10.95 | 11.02 | 72.88 | 72.30 |

| M13 | 115 | 30 | B | 13.06 | 12.61 | 88.12 | 88.80 |

| M14 | 115 | 15 | C | 10.96 | 11.08 | 78.60 | 79.07 |

| M15 | 130 | 45 | B | 12.90 | 13.07 | 88.79 | 89.72 |

| M16 | 100 | 30 | A | 10.40 | 10.85 | 73.95 | 73.34 |

| Variation source | TPC | AA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contribution | p | Contribution | p | |

| Model | 92.15% | 0.02 | 81.07% | 0.15 |

| Lineal | 89.12% | 0.01 | 38.69% | 0.15 |

| Temperature | 61.88% | 0.00 | 23.14% | 0.03 |

| Time | 10.99% | 0.07 | 9.23% | 0.12 |

| Particle | 16.25% | 0.06 | 6.32% | 0.59 |

| Quadratic | 1.70% | 0.61 | 24.80% | 0.12 |

| Temperature*Temperature | 1.68% | 0.35 | 14.35% | 0.07 |

| Time*Time | 0.02% | 0.93 | 10.45% | 0.16 |

| Two-factor interaction | 1.33% | 0.68 | 17.58% | 0.19 |

| Temperature*Particle | 1.33% | 0.68 | 17.58% | 0.19 |

| Error | 7.85% | - | 18.93% | - |

| Lack of fit | 0.57% | 0.89 | 4.21% | 0.69 |

| Pure error | 7.29% | - | 14.73% | - |

| Total | 100.00% | - | 100.00% | - |

| Response 1 | Response 2 | ρ | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPC | AA | 0.58 | (0.07; 0.85) | 0.03 |

| Response | Fit | SE Fit | 95% CI | 95% PI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPC | 112.44 | 6.77 | (95.03; 129.85) | (84.30; 140.58) |

| AA | 14.20 | 0.38 | (13.23; 15.17) | (12.64; 15.76) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).