Submitted:

11 September 2024

Posted:

12 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

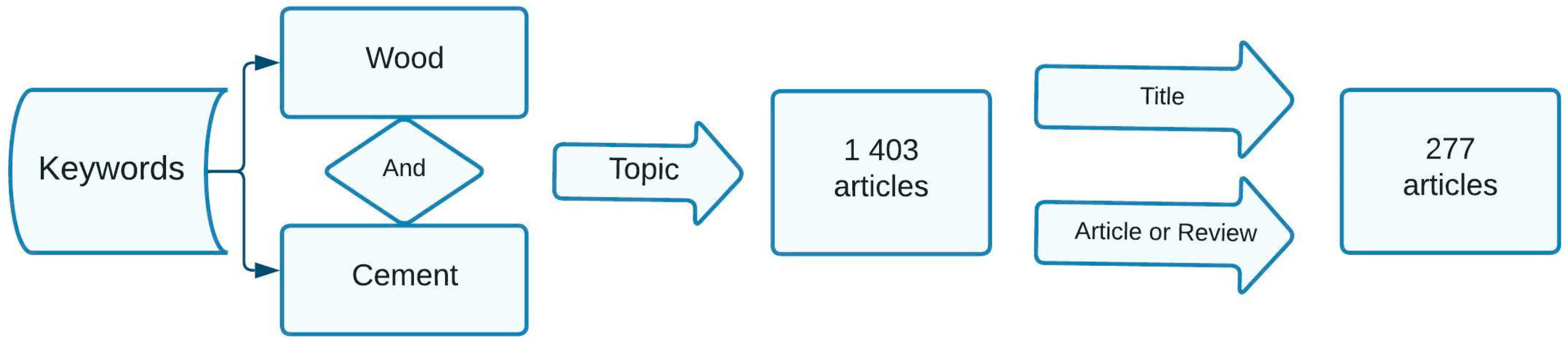

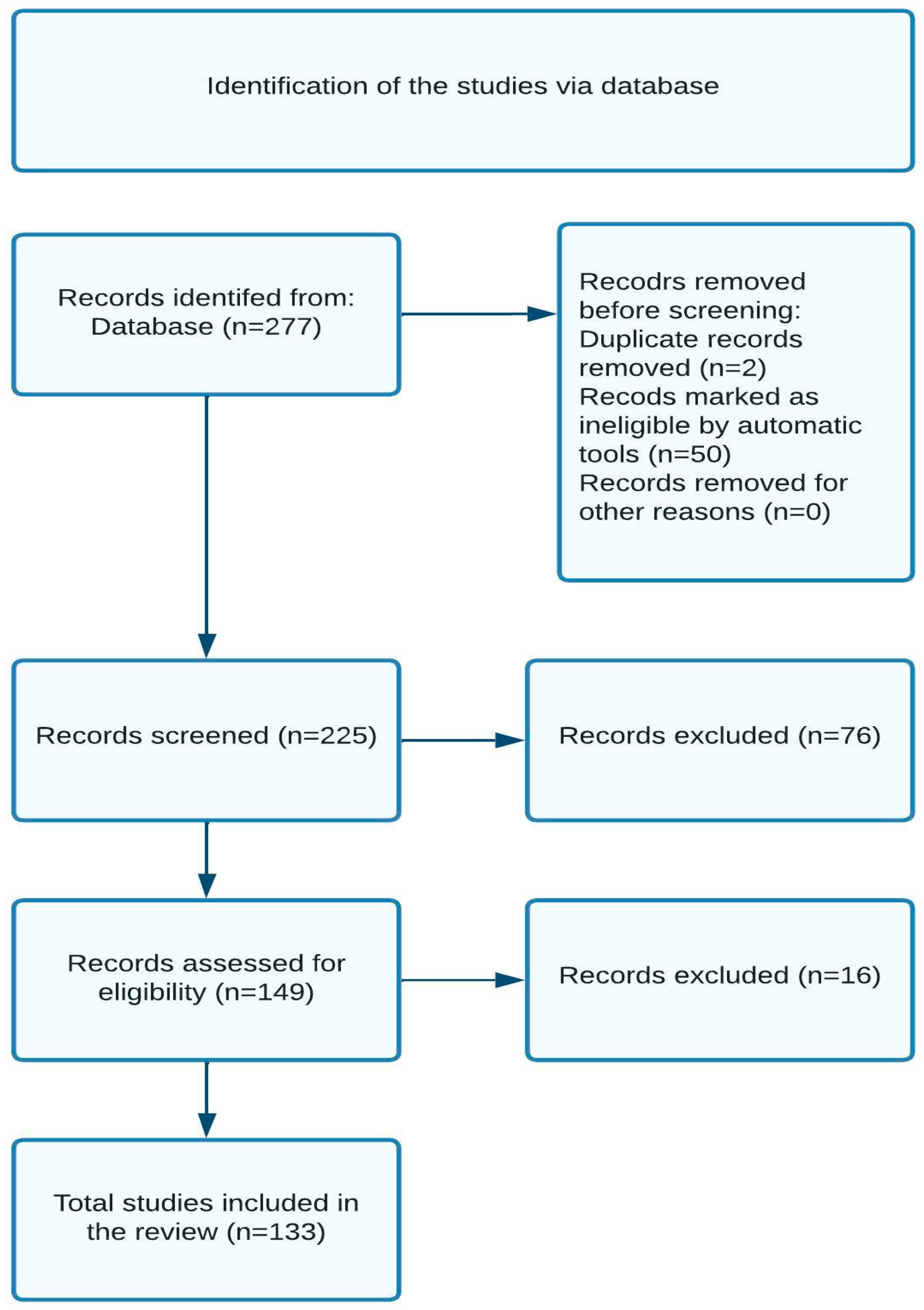

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Evolution of the Annual Number of Published Articles

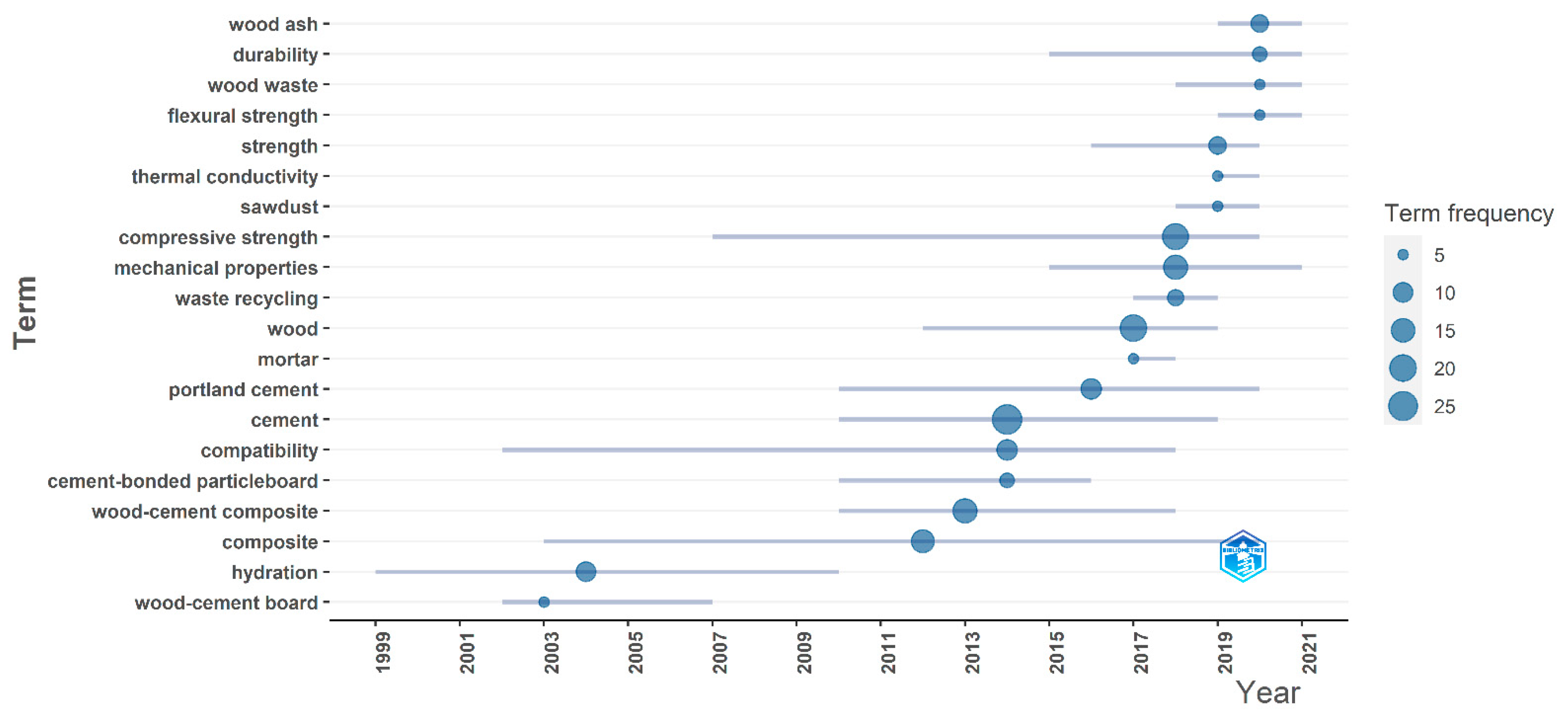

3.2. The Trend Topic Analysis

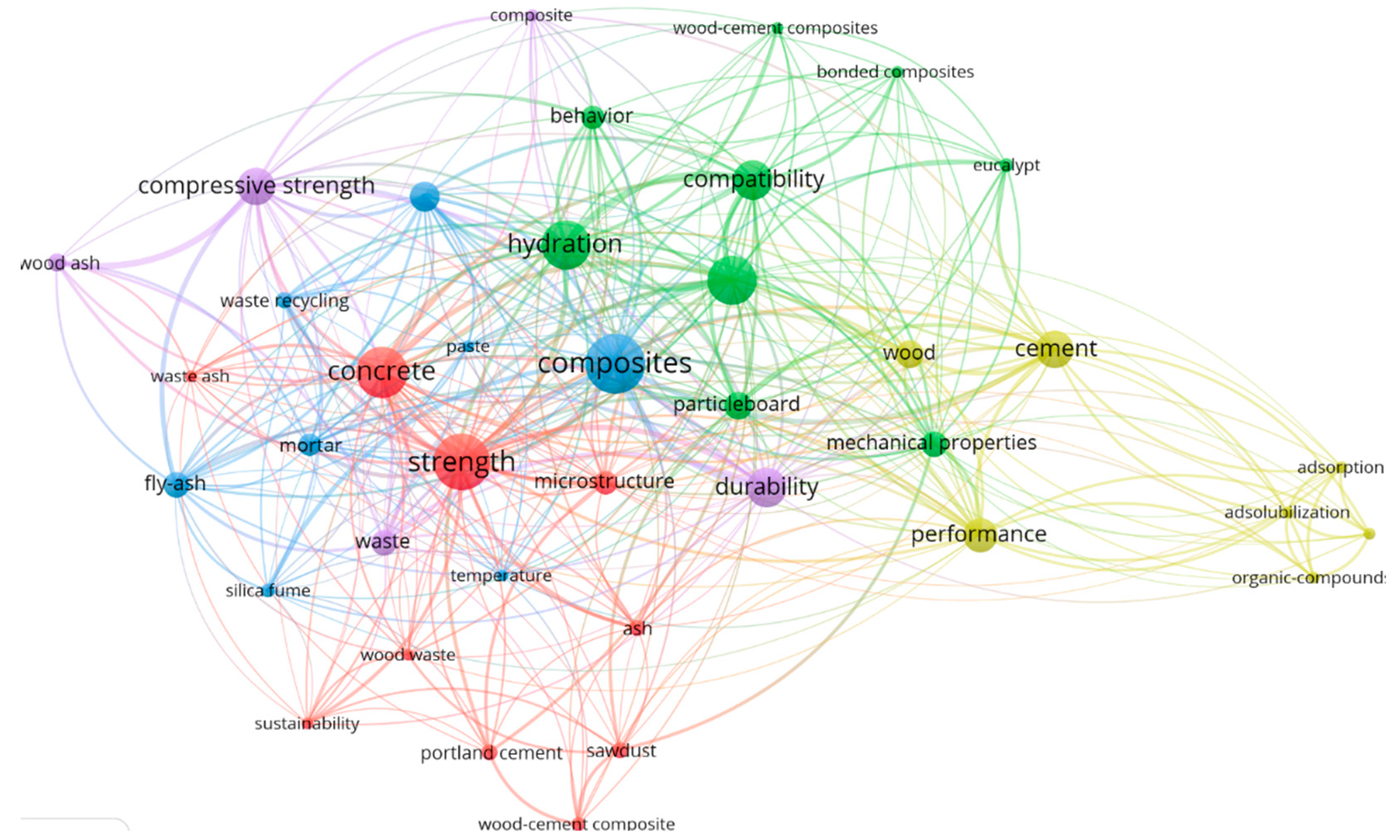

3.3. The Keywords Co-Occurrence Analysis

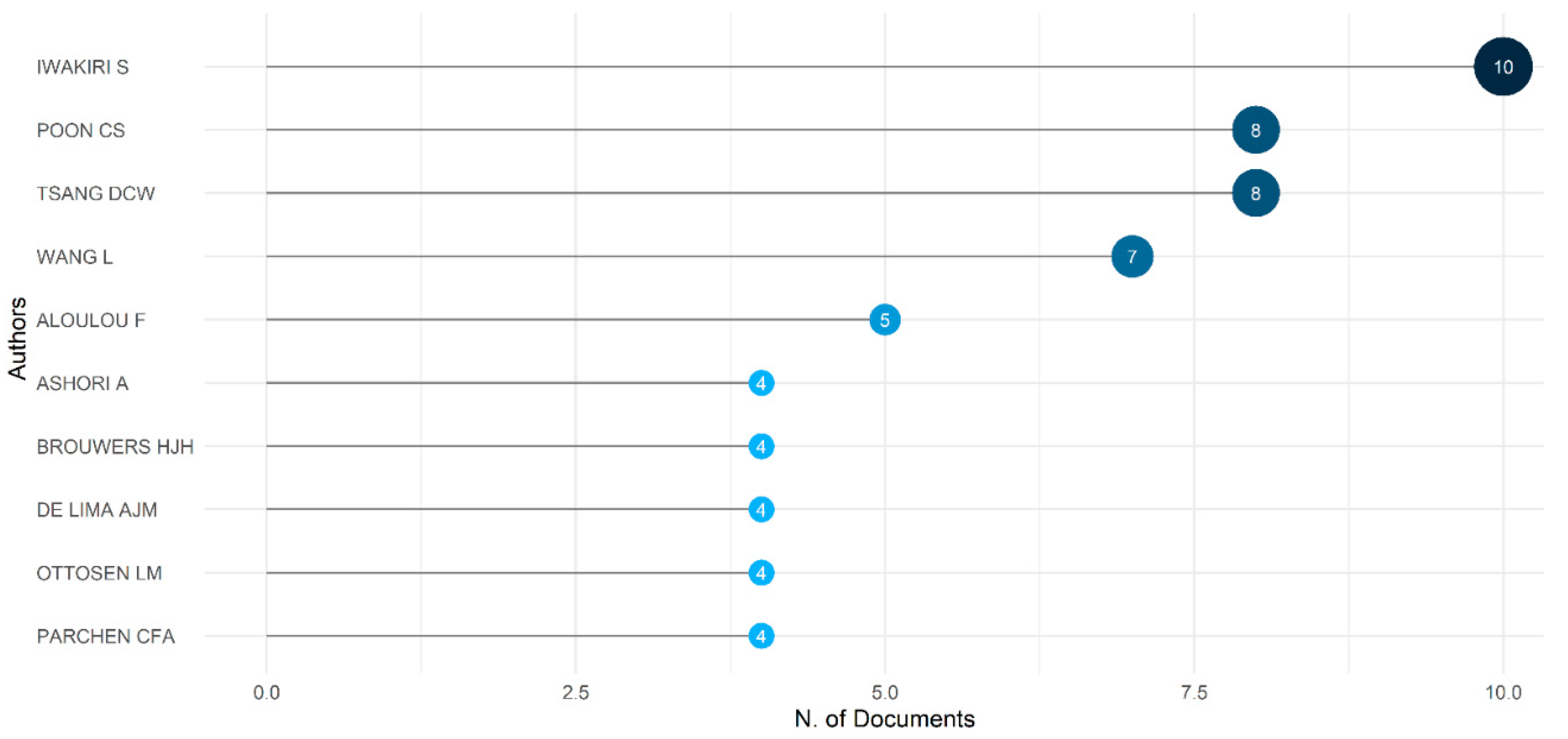

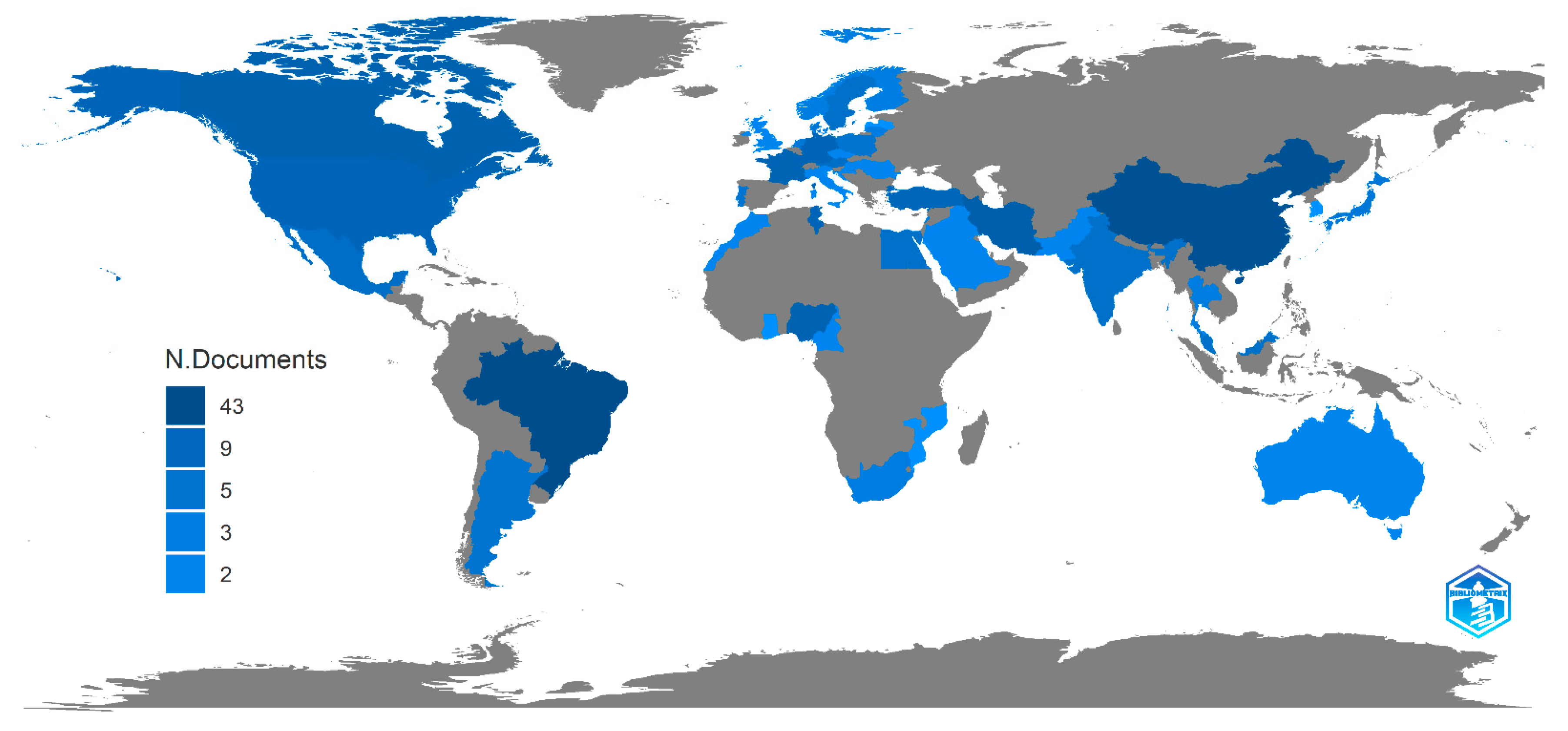

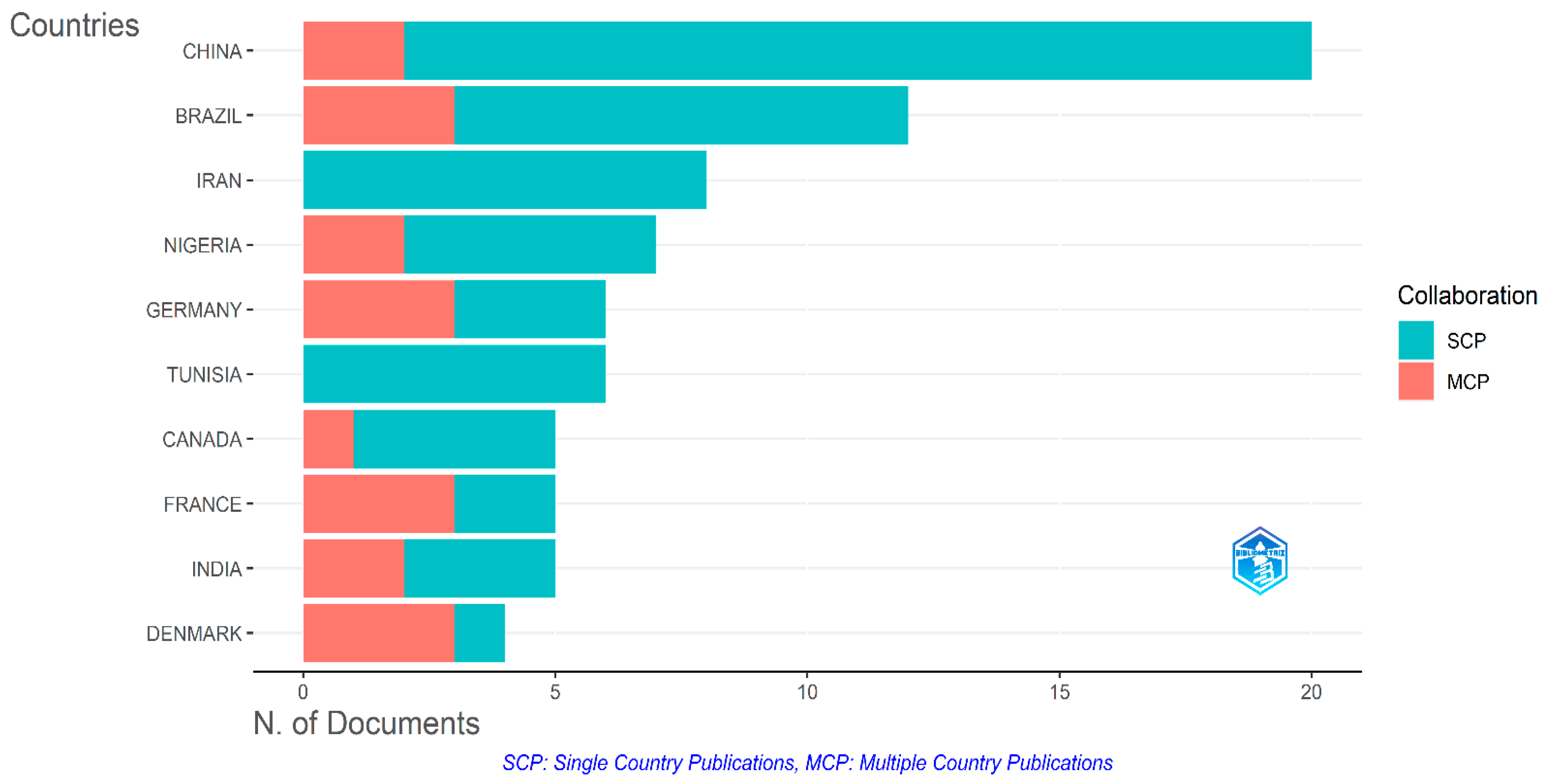

3.4. The Analysis of Authors

4. A Comprehensive Examination of the Literature

4.1. Early Investigations and Historical Context

4.2. Treatment of Wood Fibers in Wood-Cement Composites

4.3. Diverse Materials and Their Impact on Wood-Cement Composites

4.4. Exploring Wood Waste in Composite Production

4.5. Enhancing Wood-Cement Composite Characteristics

5. Conclusions

6. Key Findings and Insights

- Growing Interest: There is a discernible increase in interest surrounding the synergy between wood and cement. Researchers are fervently exploring this realm with the goal of devising new composite materials that can rival traditional concrete in terms of strength and versatility.

- Diverse Research Directions: The literature reflects diverse research directions aimed at mitigating the compatibility challenges between wood and cement. These avenues include testing different wood species, introducing various additives or treatments, and experimenting with sources of wood, such as wood waste, sawdust, or ash.

- Treatment and Enhancement: Noteworthy enhancements in the strength and compatibility of wood-cement composites were achieved through treatments such as alkali cooking modification, silane coupling agent immersion in tetraethyl orthosilicate, and the addition of cellulose nanocrystal particles, among others.

- Optimal Proportions: Research indicates that the proportion of wood plays a critical role in determining the mechanical properties of the composites. While the specifics vary, many studies suggest that lower percentages of wood in the mix tend to yield better mechanical results.

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs—Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022 Summary of Results. 2022. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Franz, B. Using the City: Migrant Spatial Integration as Urban Practice. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2018, 44, 307. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, V.U.; Nascimento, M.F.; Oliveira, P.R.; Panzera, T.H.; Rezende, M.O.; Silva, D.A.L.; Aquino, V.B.d.M.; Lahr, F.A.R.; Christoforo, A.L. Circular vs. linear economy of building materials: A case study for particleboards made of recycled wood and biopolymer vs. conventional particleboards. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 285, 122906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, L.R.; Saraiva, A.B.; Lucena, A.F.; Da Gloria, M.Y.; Santos, A.S.; Filho, R.D.T. Building materials in a circular economy: The case of wood waste as CO2-sink in bio concrete. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 166, 105346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, L.R.; Da Gloria, M.Y.R.; Pittau, F.; Andreola, V.M.; Habert, G.; Filho, R.D.T. Environmental impact assessment of wood bio-concretes: Evaluation of the influence of different supplementary cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 268, 121146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argalis, P.P.; Sinka, M.; Bajare, D. Recycling of Cement–Wood Board Production Waste into a Low-Strength Cementitious Binder. Recycling 2022, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovský, O.; Lojka, M.; Lauermannová, A.-M.; Antončík, F.; Pavlíková, M.; Pavlík, Z.; Sedmidubský, D. Carbon Dioxide Uptake by MOC-Based Materials. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, D. Building Materials Made of Wood Waste a Solution to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Materials 2021, 14, 7638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švajlenka, J.; Kozlovská, M.; Spišáková, M. The benefits of modern method of construction based on wood in the context of sustainability. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 14, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Du, Y.; Jiao, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z. Wood-Inspired Cement with High Strength and Multifunctionality. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheumani, Y.A.M.; Ndikontar, M.; De Jéso, B.; Sèbe, G. Probing of wood–cement interactions during hydration of wood–cement composites by proton low-field NMR relaxometry. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaltonen, A.; Hurmekoski, E.; Korhonen, J. What About Wood?—“Nonwood” Construction Experts' Perceptions of Environmental Regulation, Business Environment, and Future Trends in Residential Multistory Building in Finland. For. Prod. J. 2021, 71, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, E.; Adriazola, M. Thermal analysis of wood-based test cells. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, S.; Almeida, J.; Santos, B.; Humbert, P.; Tadeu, A.; António, J.; de Brito, J.; Pinhão, P. Lightweight cement composites containing end-of-life treated wood – Leaching, hydration and mechanical tests. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 317, 125931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucid, “LucidChart.” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://lucid.

- D. G. Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzla, J.; Altman. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. he PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman. Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dr. Prestemon, “Preliminary Evaluation of a Wood-Cement Composite,” Forest Products Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 43–45, 1976. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:A1976CE90000011 (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Coutts, R. Campbell Coupling agents in wood fibre-reinforced cement composites. Composites 1979, 10, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.D.; Coutts, R.S.P. Wood fibre-reinforced cement composites. J. Mater. Sci. 1980, 15, 1962–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Na, Z. Wang, H. Wang. Wood-cement compatibility review. Wood Res. 2014, 59, 813–825. [Google Scholar]

- de Lima, A.J.M.; Iwakiri, S.; Satyanarayana, K.G.; Lomelí-Ramírez, M.G. Preparation and characterization of wood-cement particleboards produced using metakaolin, calcined ceramics and residues of Pinus spp. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Han, C.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Zhou, H.; Song, X.; Zu, F. Study on wood chips modification and its application in wood-cement composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, A.; Marzocchi, V.; Rintoul, I. Influence of wood treatments on mechanical properties of wood–cement composites and of Populus Euroamericana wood fibers. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 84, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.B. Tessaro, R. D. A. Delucis, S. C. Amico. Cement Composites Reinforced with Teos-Treated Wood Fibres. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2021, 55, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayestehkia, M.; Khademieslam, H.; Bazyar, B.; Rangavar, H.; Taghiyari, H.R. Effects of Cellulose Nanocrystals as Extender on Physical and Mechanical Properties of Wood Cement Composite Panels. BioResources 2020, 15, 8291–8302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichi, A.H.; Bazyar, B.; Khademieslam, H.; Rangavar, H.; Talaeipour, M. Is wollastonite capable of improving the properties of wood fiber-cement composite? BioResources 2019, 14, 6168–6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, M.R.; Nakanishi, E.Y.; Franco, M.S.R.; Santos, S.F.; Fiorelli, J. Treatments of residual pine strands: characterization and wood-cement-compatibility. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2020, 40, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morjène, L.; Aloulou, F.; Seffen, M. Effect of organoclay and wood fiber inclusion on the mechanical properties and thermal conductivity of cement-based mortars. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2020, 23, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmia, F.Z.; Horváth, P.G.; Alpár, T.L. Effect of Pre-Treatments and Additives on the Improvement of Cement Wood Composite: A Review. BioResources 2020, 15, 7288–7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, V.-A.; Cloutier, A.; Bissonnette, B.; Blanchet, P.; Dagenais, C. Steatite Powder Additives in Wood-Cement Drywall Particleboards. Materials 2020, 13, 4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohijeagbon, I.O.; Adeleke, A.A.; Mustapha, V.T.; Olorunmaiye, J.A.; Okokpujie, I.P.; Ikubanni, P.P. Development and characterization of wood-polypropylene plastic-cement composite board. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2020, 13, e00365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, M.; Lu, L.; Zhao, P.; Gong, C. Investigation of the Adaptability of Paper Sludge with Wood Fiber in Cement-Based Insulation Mortar. BioResources 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigbomian, E.P.; Fan, M. Development of Wood-Crete building materials from sawdust and waste paper. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 40, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachmi, M.; Guelzim, M.; Hakam, A.; Sesbou, A. Wood-cement inhibition revisited and development of new wood-cement inhibitory and compatibility indices based on twelve wood species. Holzforschung 2017, 71, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.R. Marzuki, S. Rahim, M. Hamidah. Effects of wood: cement ratio on mechanical and physical properties of three-layered cement-bonded particleboards from leucaena leucocephala. J. Trop. For. Sci. 2011, 23, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, M.; Ndikontar, M.K.; Zhou, X.; Ngamveng, J.N. Cement-bonded composites made from tropical woods: Compatibility of wood and cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, F.J.N.; Scatolino, M.V.; Protásio, T.d.P.; Júnior, J.B.G.; Marconcini, J.M.; Mendes, L.M. Lignocellulosic Materials for Production of Cement Composites: Valorization of the Alkali Treated Soybean Pod and Eucalyptus Wood Particles to Obtain Higher Value-Added Products. Waste Biomass- Valorization 2020, 11, 2235–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, X. Study on compatibility of poplar wood and Portland cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 314, 125586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setter, C.; de Melo, R.R.; Carmo, J.F.D.; Stangerlin, D.M.; Pimenta, A.S. Cement boards reinforced with wood sawdust: an option for sustainable construction. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Chen, L.W.; Lee, S.H.; Mahyiddin, W.F.W.M. Behaviour of Walls Constructed using Kelempayan (Neolamarckia cadamba) Wood Wool Reinforced Cement Board. Sains Malays. 2018, 47, 1897–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.A.B.; Silva, J.V.F.; Bianchi, N.A.; Campos, C.I.; Oliveira, K.A.; Galdino, D.S.; Bertolini, M.S.; Morais, C.A.G.; de Souza, A.J.D.; Molina, J.C. Influence of Indian Cedar Particle Pretreatments on Cement-wood Composite Properties. BioResources 2020, 15, 1656–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoyebi, O.D.; Awolusi, T.F.; Davies, I.E. Artificial neural network evaluation of cement-bonded particle board produced from red iron wood (Lophira alata) sawdust and palm kernel shell residues. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Boasiako, C.; Ofosuhene, L.; Boadu, K.B. Suitability of sawdust from three tropical timbers for wood-cement composites. J. Sustain. For. 2018, 37, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohestani, B.; Koubaa, A.; Belem, T.; Bussière, B.; Bouzahzah, H. Experimental investigation of mechanical and microstructural properties of cemented paste backfill containing maple-wood filler. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 121, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, V.G.; Azambuja, R.d.R.; Parchen, C.F.A.; Iwakiri, S. Alternative vibro-dynamic compression processing of wood-cement composites using Amazonian wood. Acta Amaz. 2019, 49, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, V.G.; Azambuja, R.d.R.; Bila, N.F.; Parchen, C.F.A.; Sassaki, G.I.; Iwakiri, S. Correlation between chemical composition of tropical hardwoods and wood-cement compatibility. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2018, 38, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.K.; Kuqo, A.; Koddenberg, T.; Mai, C. Seagrass- and wood-based cement boards: A comparative study in terms of physico-mechanical and structural properties. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 156, 106864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, B.A.; Dai, C. Development of banana fibers and wood bottom ash modified cement mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 241, 118041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Wang, Y. Effect of pine needle fibre reinforcement on the mechanical properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 278, 122333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kasal, B. The immediate and short-term degradation of the wood surface in a cement environment measured by AFM. Mater. Struct. 2022, 55, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprai, V.; Gauvin, F.; Schollbach, K.; Brouwers, H. Influence of the spruce strands hygroscopic behaviour on the performances of wood-cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 166, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azambuja, R.d.R.; de Castro, V.G.; Bôas, B.T.V.; Parchen, C.F.A.; Iwakiri, S. Particle size and lime addiction on properties of wood-cement composites produced by the method of densification by vibro compaction. Cienc. Rural. 2017, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloulou, F.; Alila, S. Effect of modified fibre flour wood on the fresh condition properties of cement-based mortars. Int. J. Mason. Res. Innov. 2019, 4, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloulou, F.; Alila, S. Characterization and Influence of Nanofiber Flours of Wood Modified on Fresh State Properties of Cement Based Mortars. J. Renew. Mater. 2019, 7, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, D. The use of wood waste from construction and demolition to produce sustainable bioenergy—a bibliometric review of the literature. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 11640–11658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelusi, E.; Ajala, O.; Afolabi, R.; Olaoye, K. Strength and dimensional stability of cement-bonded wood waste-sand bricks. J. For. Sci. 2021, 67, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, F.; Gauvin, F.; Brouwers, H. The recycling potential of wood waste into wood-wool/cement composite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 260, 119786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, U.; Wang, L.; Yu, I.K.; Tsang, D.C.; Poon, C.-S. Environmental and technical feasibility study of upcycling wood waste into cement-bonded particleboard. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 173, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, R.A.; Salem, M.Z.; Al-Mefarrej, H.A.; Aref, I.M. Use of tree pruning wastes for manufacturing of wood reinforced cement composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 72, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, C.; Tayançlı, S.; Derogar, S. Recycling waste wood in cement mortars towards the regeneration of sustainable environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, A.J.M.; Iwakiri, S.; Trianoski, R. Determination of the physical and mechanical properties of wood-cement boards produced with pinus spp and pozzolans waste. maderas-ciencia y tecnologia 2020, 22, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, A.J.M.; Iwakiri, S.; Satyanarayana, K.G.; Lomelí-Ramírez, M.G. Studies on the durability of wood-cement particleboards produced with residues of Pinus spp., silica fume, and rice husk ash. BioResources 2020, 15, 3064–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Nicolas, V.; Khelifa, M.; El Ganaoui, M.; Fierro, V.; Celzard, A. Modelling the hygrothermal behaviour of cement-bonded wood composite panels as permanent formwork. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2019, 142, 111784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Khan, A.Y.; Farooq, S.H.; Hanif, A.; Tang, S.; Khushnood, R.A.; Rizwan, S.A. Eco-friendly self-compacting cement pastes incorporating wood waste as cement replacement: A feasibility study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 190, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. M. Abed and B. A., Khaleel. Effect of Wood Waste as A Partial Replacement of Cement, Fine and Coarse Aggregate on Physical and Mechanical Properties of Concrete Blocks Units. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2019, 11, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, S.S.; Tsang, D.C.; Poon, C.-S.; Dai, J.-G. CO 2 curing and fibre reinforcement for green recycling of contaminated wood into high-performance cement-bonded particleboards. J. CO2 Util. 2017, 18, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, S.S.; Tsang, D.C.; Poon, C.S.; Shih, K. Value-added recycling of construction waste wood into noise and thermal insulating cement-bonded particleboards. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 125, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.; Manea, D.L. Perspective of Using Magnesium Oxychloride Cement (MOC) and Wood as a Composite Building Material: A Bibliometric Literature Review. Materials 2022, 15, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Hossain, U.; Poon, C.S.; Tsang, D.C. Mechanical, durability and environmental aspects of magnesium oxychloride cement boards incorporating waste wood. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, I.K.; Tsang, D.C.; Yu, K.; Li, S.; Poon, C.S.; Dai, J.-G. Upcycling wood waste into fibre-reinforced magnesium phosphate cement particleboards. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 159, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, I.K.; Tsang, D.C.; Li, S.; Li, J.-S.; Poon, C.S.; Wang, Y.-S.; Dai, J.-G. Transforming wood waste into water-resistant magnesia-phosphate cement particleboard modified by alumina and red mud. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, I.K.M.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Li, S.; Poon, C.S. Mixture Design and Reaction Sequence for Recycling Construction Wood Waste into Rapid-Shaping Magnesia–Phosphate Cement Particleboard. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 6645–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiandamhen, S.; Meincken, M.; Tyhoda, L. Magnesium based phosphate cement binder for composite panels: A response surface methodology for optimisation of processing variables in boards produced from agricultural and wood processing industrial residues. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 94, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kua, H.W.; Koh, H.J. Application of biochar from food and wood waste as green admixture for cement mortar. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 619-620, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Krishnan, P.; Kashani, A.; Kua, H.W. Application of biochar from coconut and wood waste to reduce shrinkage and improve physical properties of silica fume-cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262, 120688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigvardsen, N.M.; Geiker, M.R.; Ottosen, L.M. Reaction mechanisms of wood ash for use as a partial cement replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayobami, A.B. Performance of wood bottom ash in cement-based applications and comparison with other selected ashes: Overview. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 166, 105351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigvardsen, N.M.; Geiker, M.R.; Ottosen, L.M. Phase development and mechanical response of low-level cement replacements with wood ash and washed wood ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, J.; Boluk, Y.; Bindiganavile, V. Wood ash as a supplementary cementing material in foams for thermal and acoustic insulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 215, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, C.B.; Ramli, M. The implementation of wood waste ash as a partial cement replacement material in the production of structural grade concrete and mortar: An overview. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashori, A.; Tabarsa, T.; Azizi, K.; Mirzabeygi, R. Wood–wool cement board using mixture of eucalypt and poplar. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2011, 34, 1146–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikoko, T.G.L. A Cameroonian Study on Mixing Concrete with Wood Ashes: Effects of 0-30% Wood Ashes as a Substitute of Cement on the Strength of Concretes. Rev. Des Compos. Et Des Mater. Av. Compos. Adv. Mater. 2021, 31, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, B.D.; Raheem, A.A. Characteristics of Wood Ash Cement Mortar Incorporating Green-Synthesized Nano-TiO2. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2021, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, V.; Priya, P.R. Evaluation of the permeability of high strength concrete using metakaolin and wood ash as partial replacement for cement. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carević, I.; Štirmer, N.; Serdar, M.; Ukrainczyk, N. Effect of Wood Biomass Ash Storage on the Properties of Cement Composites. Materials 2021, 14, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fořt, J.; Šál, J.; Žák, J.; Černý, R. Assessment of Wood-Based Fly Ash as Alternative Cement Replacement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, V.-A.; Cloutier, A.; Bissonnette, B.; Blanchet, P.; Duchesne, J. The Effect of Wood Ash as a Partial Cement Replacement Material for Making Wood-Cement Panels. Materials 2019, 12, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carević, I.; Baričević, A.; Štirmer, N.; Šantek Bajto, J. Correlation between physical and chemical properties of wood biomass ash and cement composites performances. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 256, 119450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C.-L. Oproiu, A. Nicoara, G. Voicu. The Effect Of Ash Resulted In Wood-Based Pannels Manufacturing Process On The Properties Of Portland Cement. University Politehnica Of Bucharest Scientific Bulletin Series B-Chemistry And Materials Science. 2020, 82, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sigvardsen, N.M.; Kirkelund, G.M.; Jensen, P.E.; Geiker, M.R.; Ottosen, L.M. Impact of production parameters on physiochemical characteristics of wood ash for possible utilisation in cement-based materials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.S.; Abdel-Gawwad, H.; Vásquez-García, S.; Israde-Alcántara, I.; Flores-Ramirez, N.; Rico, J.; Mohammed, M.S. Cleaner production of one-part white geopolymer cement using pre-treated wood biomass ash and diatomite. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J. Strength benefit of sawdust/wood ash amendment in cement stabilization of an expansive soil. Rev. Fac. De Ing. Univ. Pedagog. Y Tecnol. De Colomb. 2019, 28, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Pesonen, J. Yliniemi, T. Kuokkanen. Improving the hardening of fly ash from fluidized-bed combustion of peat and wood with the addition of alkaline activator and Portland cement. Revista Romana de Materiale-Romanian Journal Of Materials 2016, 46, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Engone, J.G.N.; El Moumen, A.; Djelal, C.; Imad, A.; Kanit, T.; Page, J. Evaluation of Effective Elastic Properties for Wood–Cement Composites: Experimental and Computational Investigations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, R.-U.; Soroushian, P.; Balachandra, A.; Nassar, S.; Weerasiri, R.; Darsanasiri, N.; Abdol, N. Effect of fiber type and content on the performance of extruded wood fiber cement products. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çavdar, A.D.; Yel, H.; Torun, S.B. Microcrystalline cellulose addition effects on the properties of wood cement boards. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 48, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, V.; Parchen, C.; Iwakiri, S. Particle Sizes and Wood/Cement Ratio Effect on the Production of Vibro-compacted Composites. Floresta e Ambient. 2018, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Khelifa, M.; Khennane, A.; El Ganaoui, M. Structural response of cement-bonded wood composite panels as permanent formwork. Compos. Struct. 2019, 209, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botterman, B.; de la Grée, G.D.; Hornikx, M.; Yu, Q.; Brouwers, H. Modelling and optimization of the sound absorption of wood-wool cement boards. Appl. Acoust. 2018, 129, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchen, C.F.A.; Iwakiri, S.; Zeller, F.; Prata, J.G. Vibro-dynamic compression processing of low-density wood-cement composites. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2016, 74, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, S.; Fu, H.; Mohrmann, S.; Wang, Z. Sound absorption performance of light-frame timber construction wall based on Helmholtz resonator. BioResources 2022, 17, 2652–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, K.A.; Brischke, C.; Meyer, C. Material moisture content of wood and cement mortars – Electrical resistance-based measurements in the high ohmic range. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 153, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, F.; Nishi, A.; Saito, H.; Asano, M.; Watanabe, S.; Kita, R.; Shinyashiki, N.; Yagihara, S.; Fukuzaki, M.; Sudo, S.; et al. Dielectric study on hierarchical water structures restricted in cement and wood materials. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2017, 28, 044008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangavar, H. Wood-Cement Board Reinforced with Steel Nets and Woven Hemp Yarns: Physical and Mechanical Properties. Drv. Ind. 2017, 68, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).