1. Introduction

Previous studies show the significant effects of prosocial behavior (defined as a voluntary behavior aimed to help and share with others [

1]); and scholastic performance in determining adolescents’ long term psychological and social adjustment. In this direction, a large body of research aimed at investigating the predictors of prosocial behavior and scholastic adjustment, showed the significant role played by academic self-efficacy, which consists of the students’ beliefs in their efficacy to reach high academic goals [

2]; however, no studies have investigated the impact of other important personality variables, such as students’ feedback sensitivity, which refers to a greater or lesser propensity to pay attention to different implicit levels of feedback [

3]. Following this direction, the present study has the overall aim of examining the effects of adolescents’ personality constructs which were only partially investigated by previous studies, such as feedback sensitivity (reward sensitivity and punishment sensitivity), on their prosocial behavior and scholastic performance also investigating the potential indirect effect of academic self-efficacy in explaining the association between adolescents’ reward/punishment sensitivity and their prosocial behavior/scholastic performance.

1.1. Feedback Sensitivity and Youths’ Social and Scholastic Adjustment

Regarding the students’ personality characteristics that predict positive psychosocial functioning, recently a wide interest extended towards the construct of feedback sensitivity. In this sense, the concept of feedback sensitivity has in general been associated with a greater or lesser propensity to pay attention to different implicit levels of feedback [

3]. Among the first authors who have provided evidence of the existence of different levels of sensitivity to feedback, noteworthy are the study conducted by Edwards and Pledger which have shown the existence of different levels of sensitivity to feedback in interpersonal communication [

4], and in particular, Booth-Butterfield found that some students tend to have more negative attributions related to feedback than others [

5]. Therefore, the concept of feedback and in particular of feedback sensitivity, is a very widespread and important concept in the social sciences, however in the same way, feedback in education is very relevant in influencing the learning processes and the students’ academic achievement [

6]. In the school context, the term feedback has often had problems of definition, particularly with respect to the positive and negative feedback [

3]. Positive feedback refers to providing reinforcement for an appropriate behavior, while negative feedback usually refers to the act of correcting an inappropriate behavior and in this sense, Jussim, Coleman, and Nassau highlighted the differences of students’ reactions to negative and positive feedback [

7].

Kluger and DeNisi first proposed that feedback interventions (FI) were, “Actions taken by (an) external change agent (s) to provide information regarding aspects of one’s own competition” [

8] (p. 255). Of fundamental importance in FI Theory is the student, who is the place of attention with his personality characteristics and the relationship with the teacher who provides the feedback. The FIT states that this place of attention is the primary problem in determining the success of feedback [

3]. Of particular interest, Kluger and DeNisi identified the main characteristics of feedback in the school context associated with its effectiveness through the cognitive mechanism of attention: message signals, personality traits and nature of the task performed [

8]. Regarding specifically the feedback sensitivity in the school context, previous studies supported that, students and specifically adolescents, tend to learn faster and at higher levels from rewards than punishments [

9]. In particular, it seems that rewards positively affect students’ positive academic functioning by motivating adolescents to pay attention [

10] and by facilitating their learning, their memory and problem solving and by establishing mutually beneficial relationships among students to achieve academic goals [

11,

12]; while the sensitivity to punishment leads to a greater disengagement in learning processes and in school life in order to avoid adverse stimuli, resulting in a worse school performance. Therefore, empirical literature seems to suggest a positive effect of reward sensitivity on the overall academic functioning and a negative effect of punishment sensitivity on this latter; however, to our knowledge, no empirical studies have examined the role played by feedback sensitivity in affecting prosocial behavior. Therefore, more studies are in need to explore this association.

1.2. Academic Self-Efficacy and and Youths’ Social and Scholastic Adjustment

Among students’ individual differences, one key factor in affecting psychosocial adjustment is well represented by students’ academic self-efficacy beliefs. Overall, self-efficacy beliefs account for the active role that individuals may have in controlling their own life based on cognitive self-regulation and reflective thinking [

2]. As stated by Bandura [

13], personal self-efficacy beliefs are stronger predictors of motivations and actions, than the real abilities of individuals. In fact, personal self-efficacy beliefs influence cognitive, affective and motivational processes [

2]. In the context of academic functioning, self-efficacy acts by orienting students’ choices of the activities to undertake, and interest, persistence, and efforts to achieve academic goals [

14]. Compared to students with low self-efficacy beliefs, students with high self-efficacy beliefs work harder and persist in difficult situations, thereby achieving higher levels of academic performance [

15]. Research on academic self-efficacy is consistent in highlighting its effect on different aspects of academic performance, such as academic motivations, learning and prosocial behavior [

16,

17]. In particular, Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara and Pastorelli examined the role of self-efficacy in academic functioning amongst a sample of 279 Italian students from middle school, and their parents [

18]. The results of the study showed positive significant associations between academic self-efficacy beliefs and students’ prosocial behavior, peer acceptance, and academic achievement. Other more recent, have demonstrated the positive impact of self-efficacy beliefs in promoting prosocial behavior by promoting the efficiency in managing social relationships to cooperate for shared goals [

19,

20].

1.3. The Present Study

Notwithstanding the important insights gained by those previous lines of work, there is a surprising lack of research considering the role of feedback sensitivity on adolescents’ adjustment and the potential effects of this latter on students’ academic self-efficacy which in turn could affects adolescents social and scholastic functioning. Accordingly, the present study has the overall aim of investigating the effects of adolescents’ feedback sensitivity (reward sensitivity/punishment sensitivity) on their prosocial behavior and scholastic performance also examining the potential indirect effect of academic self-efficacy on the association between reward/punishment sensitivity and prosocial behavior/scholastic performance.

The specific objectives of this proposal consist of: a) Examining the effect of youths’ feedback sensitivity (reward/punishment sensitivity) on their academic self-efficacy, prosocial behavior and scholastic performance; b) Examining the effect of youths’ academic self-efficacy on their prosocial behavior and scholastic performance; c) Examining the indirect effect of academic self-efficacy on the association between feedback sensitivity and prosocial behavior/scholastic performance.

Regarding the first objective, according with the Feedback Intervention Theory [

8], which supported that student’s personality characteristics play a key role in determining the success of the feedback received by teachers and consequently, the academic aspirations, motivation, success and, in accordance with previous studies [

10,

11,

12], which suggested that rewards positively affect students’ positive academic functioning by facilitating the learning processes through several cognitive processes, and that punishment negatively affect the positive academic functioning by disengaging the students’ learning, it is plausible expect to find positive significant associations between reward sensitivity and academic self-efficacy, prosocial behaviors and scholastic performance, and negative significant associations between punishment sensitivity and academic self-efficacy, prosocial behaviors and scholastic performance. However, no studies have been conducted analyzing specifically the effect of feedback sensitivity on prosocial behavior, therefore our hypothesis regarding this latter is exploratory in its nature.

Regarding the second objective, according with the Bandura’s theory [

2] about the key role played by self-efficacy beliefs in affecting the persistence and efforts to achieve personal goals by collaborating each other and also by increasing motivations, we expect to find positive significant association both between youths’ academic self-efficacy beliefs and prosocial behaviors and between youths’ academic self-efficacy and scholastic performance. In particular, we hypothesized that students’ academic self-efficacy beliefs positively affect prosocial behavior by increasing the efforts and the cooperation among students to reach their academic goals and that determines high scholastic performance by increasing students’ academic aspirations and motivations.

Finally, regarding the third objective, based on the aformentioned studies which supported the positive effects of reward sensitivity on the increasement of academic self-efficacy by acting on students goals, aspirations and efforts, and based on the aformentioned studies which suggested the positive effects of academic self-efficacy on both prosocial behavior and scholastic performance by increasing the motivations and the cohoperation among students, we expect to find that reward sensitivity could increase academic self-efficacy which in turn could positively affect both prosocial behavior and academic perfomance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were 132 adolescents (53.1% males; Mage = 16.42, SD = 1.55, range 13-19) drawn from a public high school located in Rome (Italy), from a study entitled: “PROINCLU- Predictors and Outcomes of Inclusive Teaching: The Role of Academic Self-Efficacy, Feedback Sensitivity and Prosocial Behavior”. Regarding family’s socio-economic characteristics, mothers completed on average 14.54 years of education (SD=5.08) while fathers completed 14 years of education (SD=4.19). For what concern families’ occupation, the 83.1% of parents reported to work, and among these, the 76.8% of mothers reported to have a full-time work and the same for the 82.7% of fathers. Regarding parents’ marital status, most parents (84.7%) were married, 7.6% were separated, 4.6% were in a cohabitation relationship, 3.1% were divorced.

2.2. Procedure

The study was presented to the school, teachers, parents, and students as a research project designed to better understand the role played by adolescents’ individual differences and school climate in affecting their socio-emotional adjustment with the confidentiality of the data. After obtaining approval from the local Institutional Review Board and once informed consent was obtained and signed by the school council, parents, adolescents’ assent, a URL link containing the battery of questionnaire to administer was created via the Qualtrics platform and shared with the recruited participants. The full battery of questionnaires took approximately 30 minutes. Because of the convenient nature of this sample, it was not possible to calculate the response rate. The average completion rate from both cohorts of data collection was 50%.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Youths’ Gender

1 = boys; 2 = girls.

2.3.2. Youths’ Age

Adolescents’ average years of age.

2.3.3. Parents’ Education

Participants’ mothers and fathers’ average years of education completed.

2.3.4. Youths’ Social Desirability

Participants completed the Lie Scale from the Big Five Questionnaire [

21], which evaluates the tendency of participants to give a more positive image of themselves. Adolescents were asked to rate on 11 items (item example: “I have never criticized anyone”) how typical each answer was for him/her (from 1 = “absolutely false for me” to 5 = “absolutely true for me”; α = .71).

2.3.5. Youths’ Feedback Sensitivity

Participants’ reward and punishment sensitivity were assessed using the 12-item BIS/BAS scale by Carver and White [

22]. Participants rated on a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 = Completely false for me, to 4 = Completely true for me) their feedback sensitivity. The total Punishment Sensitivity construct was obtained by averaging the participants responses on the 7 related items (e.g., “I worry about making mistakes”; α = .80); while the total Reward Sensitivity construct (alpha = .66) was obtained by averaging the participants responses on the 5 related items (e.g., “When I get something I want, I feel excited and full of energy”; α = .66).

2.3.6. Youths’ Academic Self-Efficacy

Participants’ beliefs in their efficacy were measured on a 11-item scale [

18,

23,

24], that assessed their efficacy in structuring environments conducive to learning and in planning and organizing academic activities (sample item e.g., “How well can you study when there are other interesting things to do?”). Adolescents rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1= not well at all, to 5= very well), their perceived capability to manage one’s learning and academic activities (α = .89).

2.3.7. Youths’ Prosocial Behavior

Participants rated their prosocial behavior on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1, “Never”, to 5, “Always”), 16 items (item example: “I try to help others”; α = .92) from the scale of Caprara & Pastorelli [

25], referred to the evaluation of the degrees of helpfulness, sharing, and consoling.

2.3.8. Youths’ Scholastic Performance

Participants rated their scholastic performance across 7 subject matters (reading, writing, math, spelling, social studies, science and other matters) on a 4-pont Likert scale (from 1 = failing, to 4 = above average; α = .87), from the academic section of the Youth Self-Report [

26].

2.4. Data Analytic Approach

Preliminary descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations; skewness, and kurtosis) of the variable of interest were investigated. Furthermore, Pearson’s correlation analyses have been implemented in order to preliminary investigate the potential significant associations among the studied variables. Then, a path analysis model via MPlus version 8 [

27] was implemented to examine: (a) the predictive effects of youths’ reward sensitivity and punishment sensitivity on their academic self-efficacy, prosocial behavior scholastic performance; (b) the predicted effect of youths’ scholastic self-efficacy on their prosocial behavior and scholastic performance; (c) the indirect effect of youths’ scholastic self-efficacy on the associations between feedback sensitivity (reward and punishment) and their prosocial behavior and scholastic performance. We considered youths’ gender, youth’s age, parents’ educational level and youths’ social desirability as covariates. We also estimated the correlations among the variables. The following parameters were used to evaluate the model’s goodness of fit: Chi-square Goodness of Fit (χ2) with its degrees of freedom (df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root-Mean-square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root-Mean-square Residual (SRMR). For the fit evaluation we considered the not significant χ2, the CFI values >0.90, RMSEA<0.07, and SRMR <0.08 [

28,

29].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table1 shows means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis for the studied variables. All the variables were distributed at acceptable rates to evaluate their univariate normality: values less than 2 for univariate skewness and less than 5 for univariate kurtosis were used as criteria [

28].

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables.

| Variables |

M |

SD |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

| Social Desirability |

2.64 |

0.55 |

0.08 |

0.15 |

| Reward Sensitivity |

3.30 |

0.48 |

-0.49 |

-0.50 |

| Punishment Sensitivity |

0.01 |

0.56 |

-0.49 |

0.22 |

| Academic Self-Efficacy |

3.58 |

0.70 |

-0.18 |

-0.84 |

| Prosocial Behavior |

3.57 |

0.71 |

-0.42 |

0.22 |

| Scholastic Performance |

3.11 |

0.49 |

-0.78 |

0.56 |

3.2. Correlation Analysis

Table 2 shows the correlations among the study variables.

It emerged that: reward sensitivity was positively and significantly related with punishment sensitivity and prosocial behavior; punishment sentivity was positively and significantly related with prosocial behavior; academic self-efficacy was positively and significantly related with prosocial behavior and scholastic performance.

3.3. Path Analysis

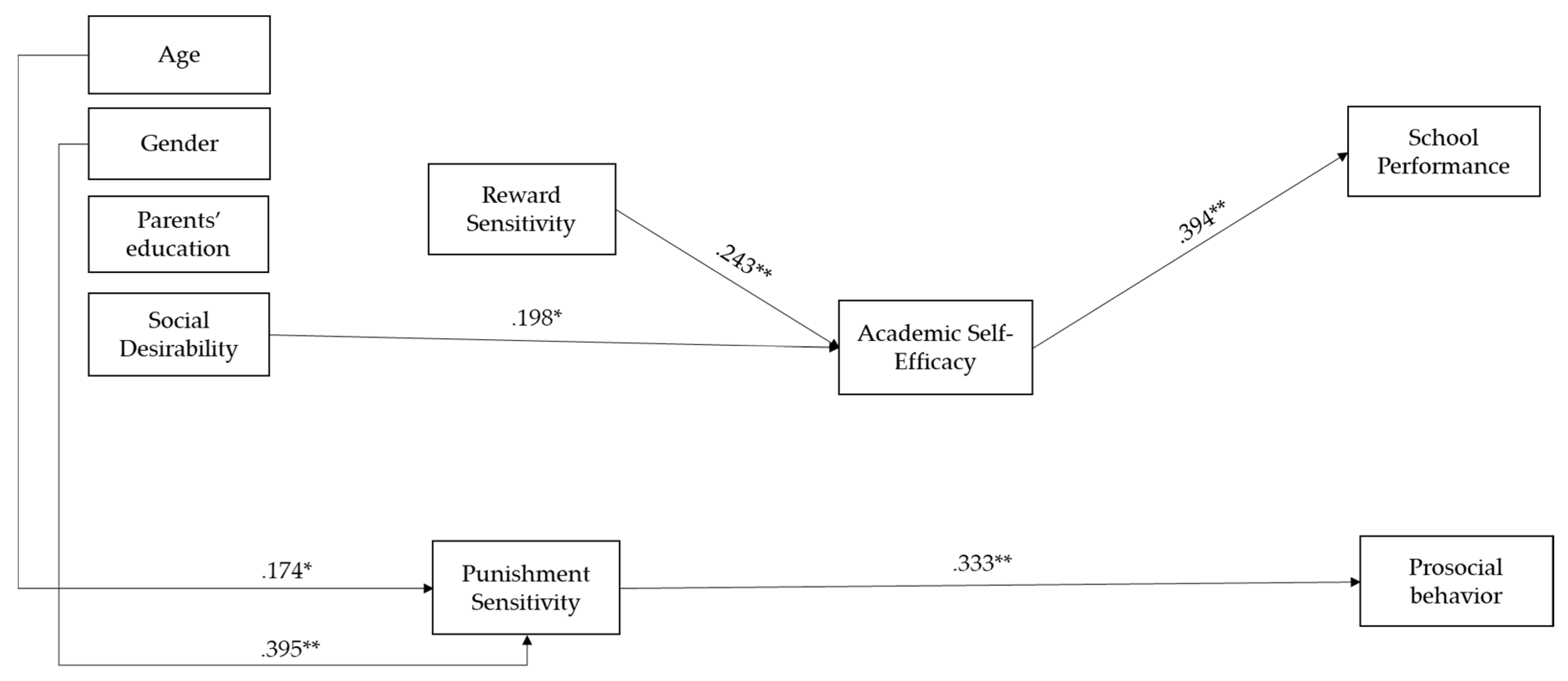

We ran a path analysis model in which we examined: the direct effects of youths’ reward sensitivity and punishment sensitivity on their academic self-efficacy, prosocial behavior and scholastic performance; the direct effect of academic self-efficacy on youths’ prosocial behavior and scholastic perfomance; the indirect effects of academic self-efficacy on the associations between youths’ feedback sensitivity (reward and punishment) and their prosocial behavior and scholastic performance. We considered youths’ gender, youth’s age, parents’ educational level and youths’ social desirability as covariates. We also estimated the correlations among the variables. The path analysis model (

Figure 1) reported a good fit to the data [χ2 (4) = 1.71, p=0.78, CFI=1.00, RMSEA = 0.00 (90% CI 0.00–0.94), SRMR=0.02].

It emerged that: (a) reward sensitivity was positivetly associated with academic self-efficacy (b) punishment sensitivity was positively associated with prosocial behavior and inclusive teaching; (c) academic self-efficacy was positively related with scholastic performance. Furthermore, we found a significant indirect effect of reward sensitivity on scholastic performance (β = .096; p=.023); it seems that reward sensitivity determine high scholastic performance by increasing academic self-efficacy. We did not found any significant within correlations. Regarding covariates, it emerged that being older is associated with punishment sensitivity. In addition, being girl was associated with punishment sensitivity. Finally, high social desirability was associated with high academic self-efficacy.

4. Discussion

Several studies emphasize the important role play by personality in affecting psychosocial adjustment and positive long-term outcomes; despite the large body of existing research on the individual differences (such as, personality traits) that can promote prosocial behavior and scholastic adjustment, there is a gap in literature regarding specific personality characteristics that, in the school context, could affect these outcomes. In this framework, the present study attempts to go beyond this gap by investigating the impact of personal characteristics that in the school context, could impact the implementation of prosocial actions and scholastic performance. We refer to feedback sensitivity. Furthermore, in our study, we included also the investigation of a specific domain of self-efficacy beliefs that, in the school activities, could be particularly relevant in the promotion of prosocial behavior and scholastic performance, academic self-efficacy beliefs.

The first objective of this study was to examine the effect of youths’ feedback sensitivity (reward/punishment sensitivity) on their academic self-efficacy, prosocial behavior and scholastic performance. Regarding the effects of feedback sensitivity on prosocial behavior, no previous studies have been conducting, therefore our hypothesis was exploratory; however, in accordance with empirical research which support that rewards positively affect students’ positive academic functioning by facilitating the learning processes, and that punishment negatively affect the positive academic functioning by disengaging the students’ learning, we expected to find positive significant associations between reward sensitivity and both prosocial behaviors and scholastic performance, and conversely, negative significant associations between punishment sensitivity and both prosocial behavior and scholastic performance. However, our results were different, in fact we found only a positive significant association between feedback sensitivity and prosocial. This unexpected result could be interpreted on the base of the fact that is more likely that the sensitivity to feedback received in the school context, and in particular reward sensitivity, act at more significant level on cognitive processes (such as planning school activities and organizing the,) than on behavior. It could be plausible that students, who are more sensitive to the negative feedback received at school, are less able to apply their cognitive capabilities to reach their academic goals and therefor that they try to find different way to reach those goals such as collaborate with other students. However, it is important to recognize that this explanation it is not supported by scientific data and that must be better explored in future studies. Regarding the effects of feedback sensitivity on academic self-efficacy, our results were consistent with the study hypotheses suggesting a positive and significant association between reward sensitivity and academic self-efficacy. In fact, in accordance with the Feedback Intervention Theory [

8], which supported the feedback received by teachers affects academic aspirations, motivation, which are proxy of academic self-efficacy believes, our findings highlighted the important role played by rewards in facilitating the learning processes through several cognitive processes which act on the self-efficacy believes system.

The second objective of this study was to investigate the associations between academic self-efficacy believes and both prosocial behavior and scholastic performance. Our results, in accordance with the Bandura’s theory [

2] about the key role played by self-efficacy beliefs in affecting the persistence and efforts to achieve personal goals, support the positive and significant effect academic self-efficacy on ascholastic performance. Therefore, our study confirmed the importance of increasing self-efficacy beliefs, in particular acting on their sources (mastering experiences, modelling, positive feedback, emotion regulation) in order to increase positive scholastic outcomes. However, we did not find any significant effect of academic self-efficacy on prosocial behavior. Regarding this finding, it is plausible to speculate that other domain of self-efficacy believes more related to social life, such as collective self.efficacy believes or social self-efficacy believes, could determine an increasement in youths’ prosocial behavior.

Finally, the third objective of this study was to investigate the indirect effect of academic self-efficacy on the association between feedback sensitivity and the studied outcomes. On the base of the aformentioned studies which supported the positive effects of reward sensitivity on the increasement of academic self-efficacy by acting on students goals, aspirations and efforts, and based on the aformentioned studies which suggested the positive effects of academic self-efficacy on scholastic performance by increasing the motivations and academic aspirations, we expected to find that reward sensitivity could increase academic self-efficacy which in turn could positively affect academic perfomance. Our findings confermed this hypothesys. In fact, it seems that reward sensitivity indirectly affects youths’ high academic performance by increasing their self-efficacy believes.

5. Conclusions

This study presents several strengths. First, we confirm the significant role played by academic self-efficacy in determining a high scholastic performance. This result is significant also in term of practical implications. In fact, it could be useful act on students’ sources of self-efficacy beliefs in order to increase prosocial behavior. Second, this study supports the significant role of other personality structure on which we could act to increase prosocial behavior, such as punishment sensitivity. Finally, our result suggest that it is possible to increase students’ academic performance indirectly acting on students’ reward sensitivity, which in turn, increase the students’ level of academic self-efficacy In addition, our result remains strong and significant also controlling for several covariates.

Despite these strengths there also some limits of the study that future research could overcome. We did not examine the role played by other variables such as the school characteristics, that could affect the identified results. Furthermore, all our variables were self- reported by students, it could be useful also to include other reported measures of the investigating variables. In addition, we used a convenient sample that cannot be considered nationally representative of the general population. Another relevant limit of the present study consists of the relatively low participation rate. Lastly, our data are correlational in their nature limiting causal relationships among the examined variables.

Future research should overcome these limits: (a) by relying on a multi-informant approach based also on teachers and parents reported measures; (b) by examining other students’ personality characteristics, such as personality traits; (c) by longitudinally and internationally investigating the associations among the studied variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Carolina Lunetti and Laura Di Giunta; methodology, Carolina Lunetti, Laura Di Giunta, Clementina Comitale and Ainzara Favini; formal analysis, Carolina Lunetti.; investigation, Carolina Lunetti, Laura Di Giunta, Clementina Comitale and Ainzara Favini; data curation, Carolina Lunetti and Clementina Comitale; writing—original draft preparation, Carolina Lunetti, Laura Di Giunta, Clementina Comitale and Ainzara Favini; writing—review and editing, Carolina Lunetti, Laura Di Giunta, Clementina Comitale and Ainzara Favini; supervision, Laura Di Giunta.; project administration, Carolina Lunetti and Clementina Comitale; funding acquisition, Carolina Lunetti. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by La Sapienza University of Rome, grant BE-FOR-ERC2021 - SAPIExcellence.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology, La Sapienza University of Rome (02/02/2022) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author (c.lunetti@unimarconi.it) upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the students who participated in this research and the many research assistants who helped gather data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Eisenberg, N.; Hofer, C.; Sulik, M. J.; Liew, J. The Development of Prosocial Moral Reasoning and a Prosocial Orientation in Young Adulthood: Concurrent and Longitudinal Correlates. Developmental Psychology 2014, 50, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. The Anatomy of Stages of Change. American Journal of Health Promotion 1997, 12, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C. D.; King, P. E. Student Feedback Sensitivity and the Efficacy of Feedback Interventions in Public Speaking Performance Improvement. Communication Education 2004, 53, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.; Pledger, L. Development and Construct Validation of the Sensitivity to Feedback Scale. Communication Research Reports 1990, 7, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth-Butterfield, M. The Interpretation of Classroom Performance Feedback: An Attributional Approach. Communication Education 1989, 38, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J.; Timperley, H. The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research 2007, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. D.; King, P. E. Student Feedback Sensitivity and the Efficacy of Feedback Interventions in Public Speaking Performance Improvement. Communication Education 2004, 53, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, A. N.; DeNisi, A. The Effects of Feedback Interventions on Performance: A Historical Review, a Meta-Analysis, and a Preliminary Feedback Intervention Theory. Psychological Bulletin 1996, 119, 254–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauffman, E.; Shulman, E. P.; Steinberg, L.; Claus, E.; Banich, M. T.; Graham, S.; Woolard, J. Age Differences in Affective Decision Making as Indexed by Performance on the Iowa Gambling Task. Developmental Psychology 2010, 46, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, A.; Geier, C. F.; Ordaz, S. J.; Teslovich, T.; Luna, B. Developmental Changes in Brain Function Underlying the Influence of Reward Processing on Inhibitory Control. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 2011, 1, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidow, Juliet Y.; Foerde, K.; Galván, A.; Shohamy, D. An Upside to Reward Sensitivity: The Hippocampus Supports Enhanced Reinforcement Learning in Adolescence. Neuron 2016, 92 (1), 93–99. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Schaaf, M. E.; Warmerdam, E.; Crone, E. A.; Cools, R. Distinct Linear and Non-Linear Trajectories of Reward and Punishment Reversal Learning during Development: Relevance for Dopamine’s Role in Adolescent Decision Making. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 2011, 1, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Self-efficacy: The foundation of agency. In Control of human behavior, mental processes, and consciousness: Essays in honor of the 60th birthday of August Flammer., 1nd ed.; Walter J. Perrig, Alexander Grob, Eds.; Publisher: Psychology Press, 2000; pp. 17-33. [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., & Usher, E. L.; Assessing self-efficacy for self-regulated learning. In Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance, 1nd ed.; B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2011; pp. 282-297. [CrossRef]

- Pajares, F., & Schunk, D. Self-beliefs and school success: Self-efficacy, self-concept, and school achievement. In R. Riding, & S. Rayner (Eds.), International perspectives on individual differences: Self-perception, Vol. 2, 2001; pp. 239–265. Ablex.

- Pajares, F. Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Academic Settings. Review of Educational Research 1995, 66, 543–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H. Self-Efficacy and Education and Instruction. Self-Efficacy, Adaptation, and Adjustment 1995, 281–303. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G. V.; Pastorelli, C. Multifaceted Impact of Self-Efficacy Beliefs on Academic Functioning. Child Development 1996, 67, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, G.; Chen, Y.; Huang, L. The Relationship between Ego Depletion and Prosocial Behavior of College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Social Self-Efficacy and Personal Belief in a Just World. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, S. T.; Geelan, B. J.; Zaehringer, S.; Mutuura, K.; Wolkow, E.; Frasseck, L.; Opwis, K. Potentials and Pitfalls of Increasing Prosocial Behavior and Self-Efficacy over Time Using an Online Personalized Platform. PLOS ONE 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprara, G. V.; Barbaranelli, C.; Borgogni, L.; Perugini, M. The “Big Five Questionnaire”: A New Questionnaire to Assess the Five Factor Model. Personality and Individual Differences 1993, 15, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S.; White, T. L. Behavioral Inhibition, Behavioral Activation, and Affective Responses to Impending Reward and Punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1994, 67, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Perceived Self-Efficacy in the Exercise of Personal Agency. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 1990, 2, 128–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorelli C, Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, Rola J, Rozsa S, & Bandura A. The structure of children’s perceived self-efficacy: A cross-national study. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2001; 17(2): 87–97. [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V.; Pastorelli, C. Early Emotional Instability, Prosocial Behaviour, and Aggression: Some Methodological Aspects. European Journal of Personality 1993, 7, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T. M. Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry, 1991.

- Muthén BO, & Muthén LK. Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2017. Available online: https://www.statmodel.com/.

- Curran, P.; West, S.; Finch, J. F. The Robustness of Test Statistics to Nonnormality and Specification Error in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Semantic Scholar 1996, 1 (1). [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. Promise and Pitfalls of Structural Equation Modeling in Gifted Research. American Psychological Association eBooks 2010, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).