Submitted:

12 September 2024

Posted:

12 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Experiment and Sample Collection

2.2. Meat Quality Traits Detection

2.3. Analyses of Blood Parameters

2.4. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.6. Statistics Analysis

3. Results

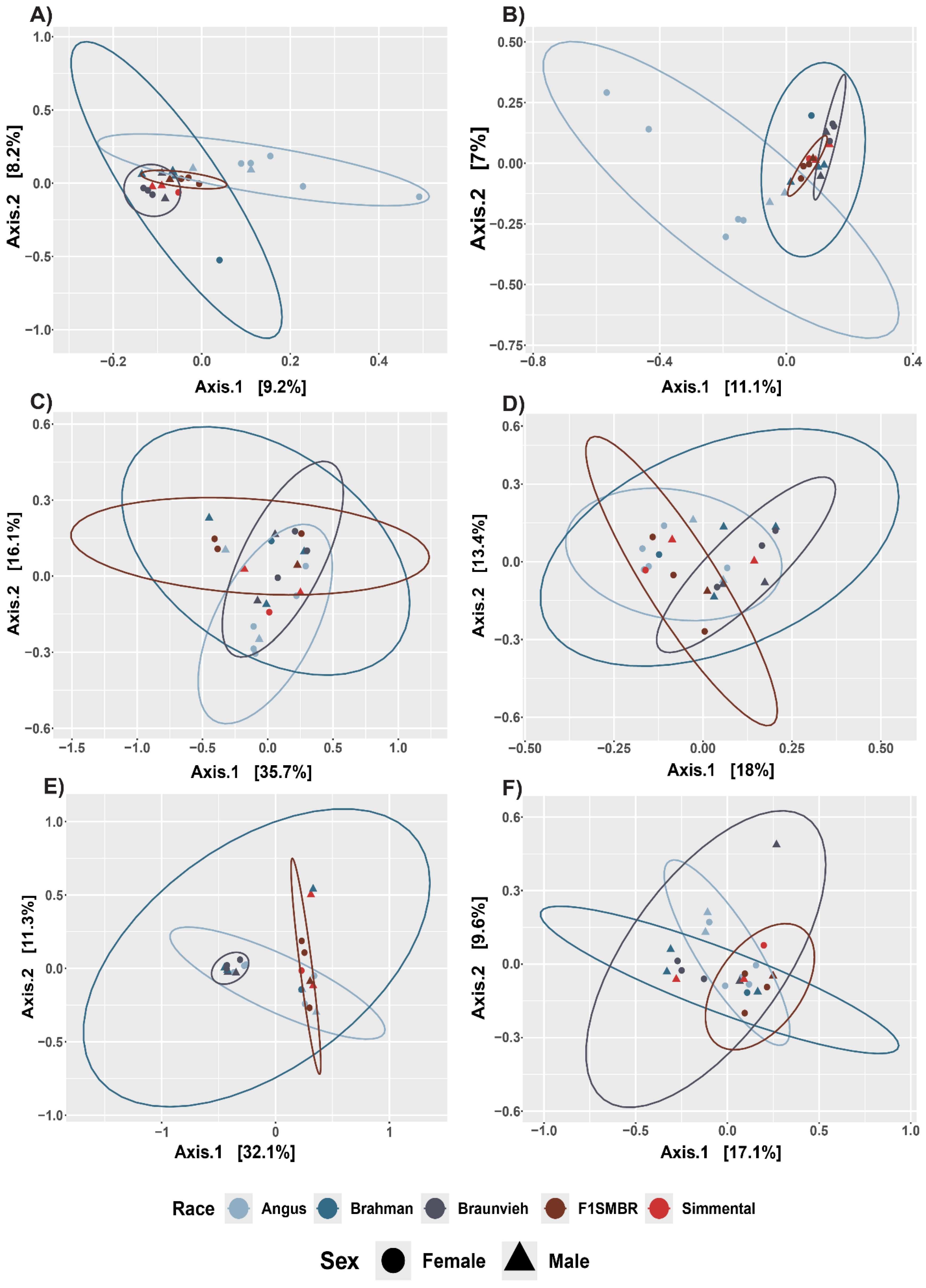

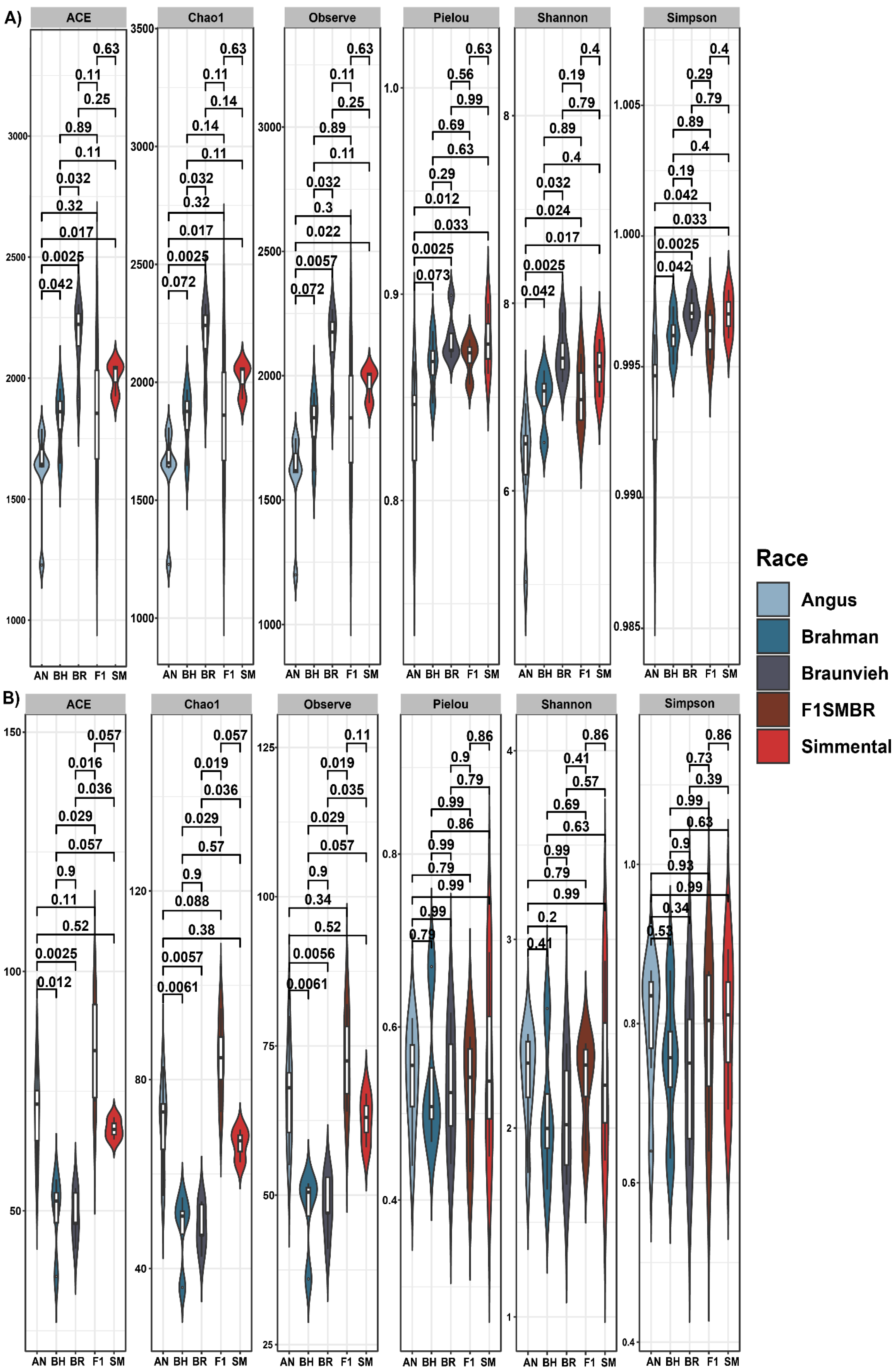

3.1. Analysis of Effect of Breed on the Gut Microbiota Diversity and Composition

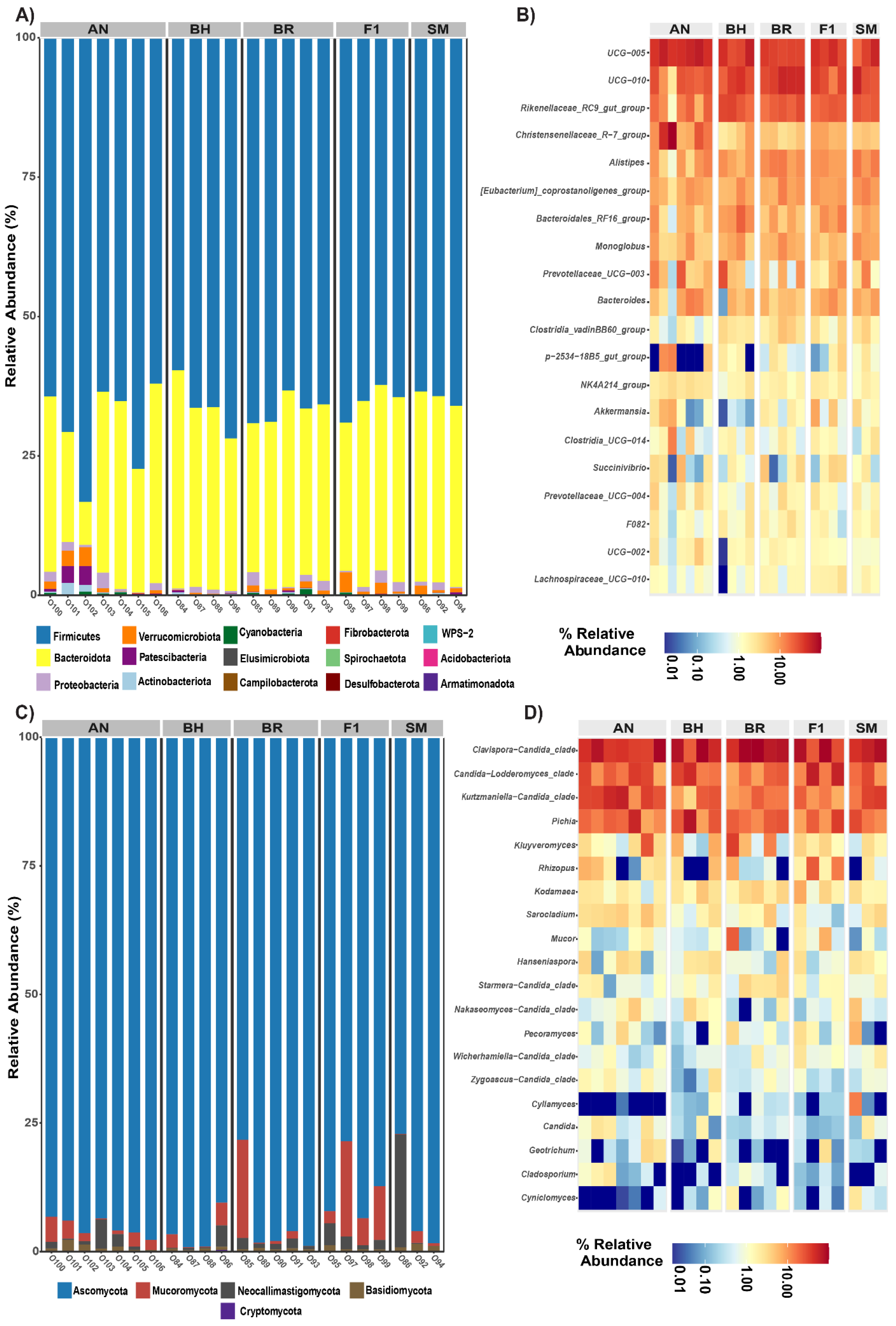

3.2. Effect of Breed on the Gut Microbiota Taxonomy

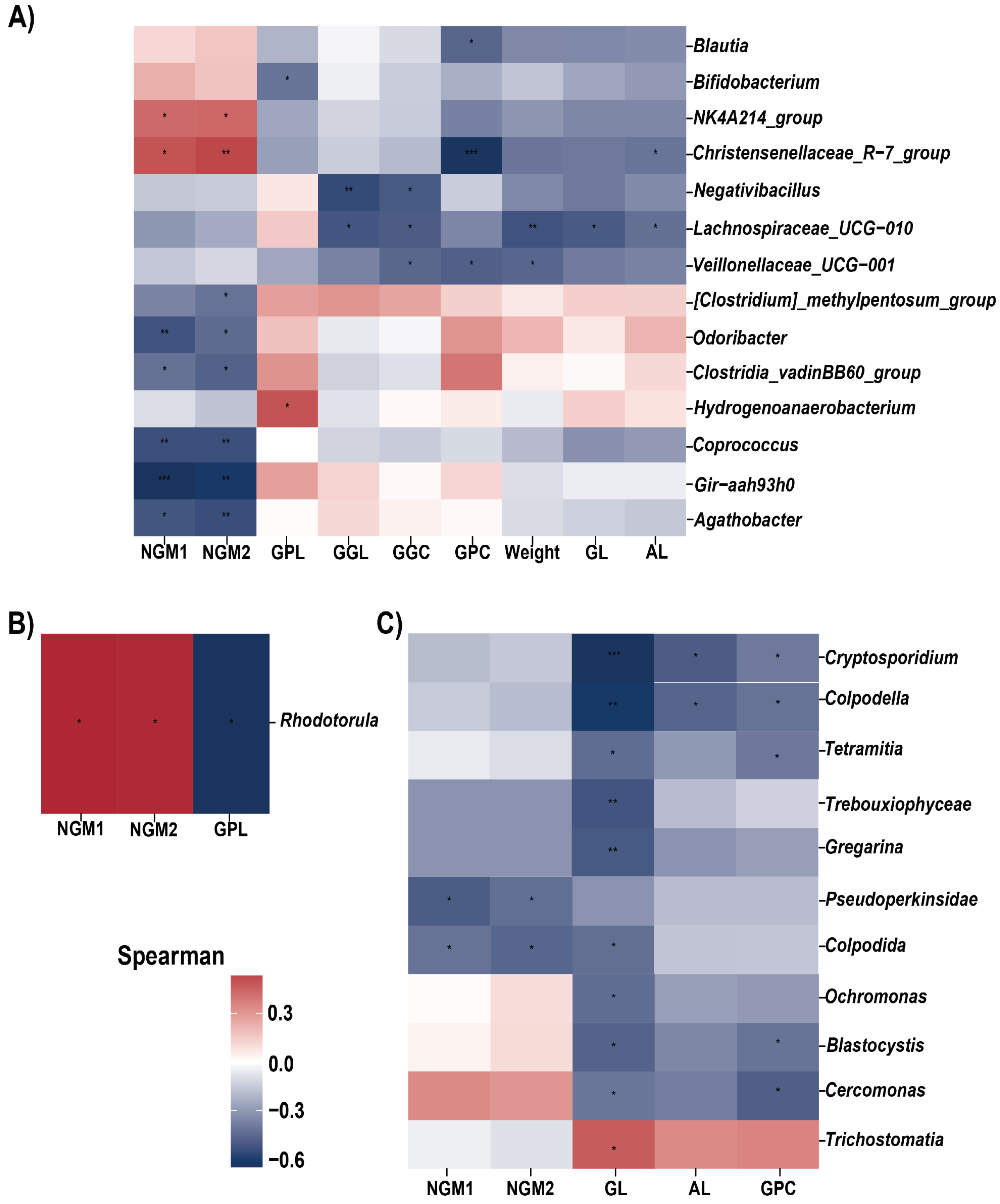

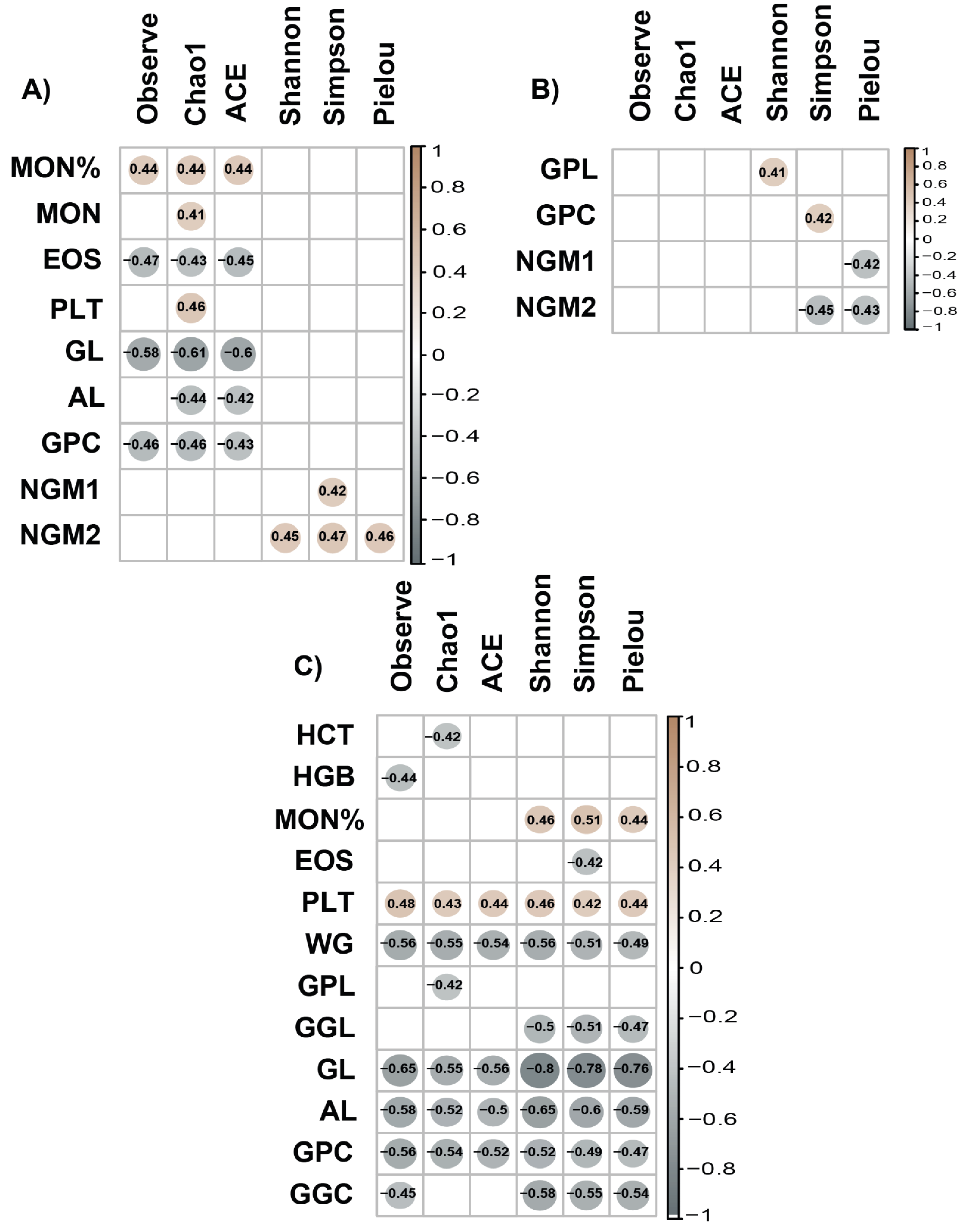

3.3. Relationship between Gut Microbiota and Beef Quality Variables

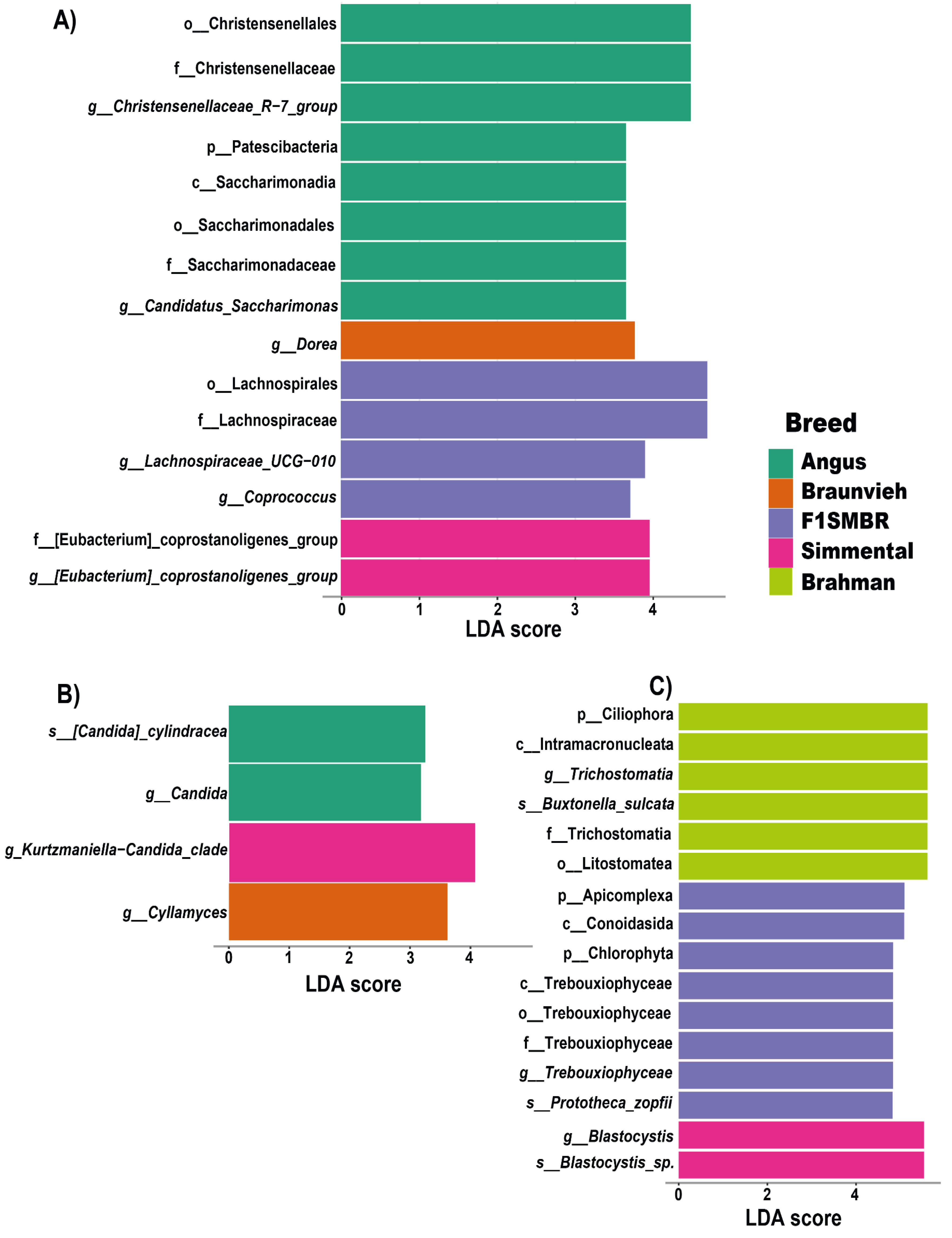

3.4. Biomarkers Identification for Different Breed

3.5. Breed Relationship of Alpha/Beta Diversity with Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Lin, L.; Miao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, B. Intestinal Barrier Damage Involved in Intestinal Microflora Changes in Fluoride-Induced Mice. Chemosphere 2019, 234, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Liu, B.; Li, F.; He, Y.; Wang, L.; Fakhar-e-Alam Kulyar, M.; Li, H.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Integrated Bacterial and Fungal Diversity Analysis Reveals the Gut Microbial Alterations in Diarrheic Giraffes. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, M.; Ma, J. Dynamic Distribution of Gut Microbiota in Cattle at Different Breeds and Health States. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1113730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Irving, B.; Fitzsimmons, C.; Plastow, G.; Guan, L.L. Host Genetics Influence the Rumen Microbiota and Heritable Rumen Microbial Features Associate with Feed Efficiency in Cattle. Microbiome 2019, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, W.; Howard, J.T.; Paz, H.A.; Hales, K.E.; Wells, J.E.; Kuehn, L.A.; Erickson, G.E.; Spangler, M.L.; Fernando, S.C. Influence of Host Genetics in Shaping the Rumen Bacterial Community in Beef Cattle. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.J.; Sasson, G.; Garnsworthy, P.C.; Tapio, I.; Gregson, E.; Bani, P.; Huhtanen, P.; Bayat, A.R.; Strozzi, F.; Biscarini, F.; et al. A Heritable Subset of the Core Rumen Microbiome Dictates Dairy Cow Productivity and Emissions. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav8391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasson, G.; Kruger Ben-Shabat, S.; Seroussi, E.; Doron-Faigenboim, A.; Shterzer, N.; Yaacoby, S.; Berg Miller, M.E.; White, B.A.; Halperin, E.; Mizrahi, I. Heritable Bovine Rumen Bacteria Are Phylogenetically Related and Correlated with the Cow’s Capacity To Harvest Energy from Its Feed. mBio 2017, 8, 10.1128/mbio.00703-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmora, N.; Suez, J.; Elinav, E. You Are What You Eat: Diet, Health and the Gut Microbiota. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canibe, N.; O’Dea, M.; Abraham, S. Potential Relevance of Pig Gut Content Transplantation for Production and Research. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, J.K.; Davenport, E.R.; Waters, J.L.; Clark, A.G.; Ley, R.E. Cross-Species Comparisons of Host Genetic Associations with the Microbiome. Science 2016, 352, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Li, K.; Xiang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Gui, G.; Yang, H. The Fecal Microbiota Composition of Boar Duroc, Yorkshire, Landrace and Hampshire Pigs. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 30, 1456–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit, R.J.; Hinsu, A.T.; Patel, N.V.; Koringa, P.G.; Jakhesara, S.J.; Thakkar, J.R.; Shah, T.M.; Limon, G.; Psifidi, A.; Guitian, J.; et al. Microbial Diversity and Community Composition of Caecal Microbiota in Commercial and Indigenous Indian Chickens Determined Using 16s rDNA Amplicon Sequencing. Microbiome 2018, 6, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Wang, Y.; Liang, J.; Wu, Y.; Wright, A.; Liao, X. Exploratory Analysis of the Microbiological Potential for Efficient Utilization of Fiber Between Lantang and Duroc Pigs. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wright, A.-D.G.; Si, H.; Wang, X.; Qian, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, G. Changes in the Rumen Microbiome and Metabolites Reveal the Effect of Host Genetics on Hybrid Crosses. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2016, 8, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bainbridge, M.L.; Cersosimo, L.M.; Wright, A.-D.G.; Kraft, J. Rumen Bacterial Communities Shift across a Lactation in Holstein, Jersey and Holstein × Jersey Dairy Cows and Correlate to Rumen Function, Bacterial Fatty Acid Composition and Production Parameters. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Sanabria, E.; Goonewardene, L.A.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, M.; Moore, S.S.; Guan, L.L. Influence of Sire Breed on the Interplay among Rumen Microbial Populations Inhabiting the Rumen Liquid of the Progeny in Beef Cattle. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e58461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehe, R.; Dewhurst, R.J.; Duthie, C.-A.; Rooke, J.A.; McKain, N.; Ross, D.W.; Hyslop, J.J.; Waterhouse, A.; Freeman, T.C.; Watson, M.; et al. Bovine Host Genetic Variation Influences Rumen Microbial Methane Production with Best Selection Criterion for Low Methane Emitting and Efficiently Feed Converting Hosts Based on Metagenomic Gene Abundance. PLOS Genet. 2016, 12, e1005846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagaoua, M.; Picard, B. Current Advances in Meat Nutritional, Sensory and Physical Quality Improvement. Foods 2020, 9, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakowski, T.; Grodkowski, G.; Gołebiewski, M.; Slósarz, J.; Kostusiak, P.; Solarczyk, P.; Puppel, K. Genetic and Environmental Determinants of Beef Quality—A Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petracci, M.; Soglia, F.; Berri, C. Chapter 3 - Muscle Metabolism and Meat Quality Abnormalities. In Poultry Quality Evaluation; Petracci, M., Berri, C., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing, 2017; pp. 51–75 ISBN 978-0-08-100763-1.

- Gerber, P.J.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.I.; Falcucci, A.; Teillard, F. Environmental Impacts of Beef Production: Review of Challenges and Perspectives for Durability. Meat Sci. 2015, 109, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorslund, C.A.H.; Sandøe, P.; Aaslyng, M.D.; Lassen, J. A Good Taste in the Meat, a Good Taste in the Mouth – Animal Welfare as an Aspect of Pork Quality in Three European Countries. Livest. Sci. 2016, 193, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.T.; Kim, G.D.; Hwang, Y.H.; Ryu, Y.C. Control of Fresh Meat Quality through Manipulation of Muscle Fiber Characteristics. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corredor, F.-A.; Figueroa, D.; Estrada, R.; Salazar, W.; Quilcate, C.; Vásquez, H.V.; Gonzales, J.; Maicelo, J.L.; Medina, P.; Arbizu, C.I. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of a Peruvian Cattle Herd Using SNP Data. Front. Genet. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, G.Y.G.; Torre-Trinidad, L.L.; Farje-Muguruza, P.; Vargas, J.F.G. Desarrollo y calidad embrionaria de un protocolo de superovulación en vacas Brahman en el distrito de Codo del Pozuzo, Huánuco, Perú. Braz. J. Anim. Environ. Res. 2024, 7, e70052–e70052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Guo, Q.; Deng, H.; Luo, J.; Yi, K.; Sun, A.; Chen, K.; Shen, Q. Muscle Fatty Acids, Meat Flavor Compounds and Sensory Characteristics of Xiangxi Yellow Cattle in Comparison to Aberdeen Angus. Animals 2022, 12, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conanec, A.; Campo, M.; Richardson, I.; Ertbjerg, P.; Failla, S.; Panea, B.; Chavent, M.; Saracco, J.; Williams, J.L.; Ellies-Oury, M.-P.; et al. Has Breed Any Effect on Beef Sensory Quality? Livest. Sci. 2021, 250, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cziszter, L.-T.; Ilie, D.-E.; Neamt, R.-I.; Neciu, F.-C.; Saplacan, S.-I.; Gavojdian, D. Comparative Study on Production, Reproduction and Functional Traits between Fleckvieh and Braunvieh Cattle. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 30, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrow, H.M. Genetic Aspects of Cattle Adaptation in the Tropics. Genet. Cattle 2015, 571–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.J.; Koester, L.R.; Schmitz-Esser, S. Rumen Epithelial Communities Share a Core Bacterial Microbiota: A Meta-Analysis of 16S rRNA Gene Illumina MiSeq Sequencing Datasets. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaulot, D.; Geisen, S.; Mahé, F.; Bass, D. Pr2-Primers: An 18S rRNA Primer Database for Protists. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2022, 22, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Tulsani, N.J.; Jakhesara, S.J.; Dafale, N.A.; Patil, N.V.; Purohit, H.J.; Koringa, P.G.; Joshi, C.G. Exploring the Eukaryotic Diversity in Rumen of Indian Camel (Camelus Dromedarius) Using 18S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 1861–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukin, Y.S.; Mikhailov, I.S.; Petrova, D.P.; Galachyants, Y.P.; Zakharova, Y.R.; Likhoshway, Y.V. The Effect of Metabarcoding 18S rRNA Region Choice on Diversity of Microeukaryotes Including Phytoplankton. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PloS One 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Yao, M. Microeco: An R Package for Data Mining in Microbial Community Ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fiaa255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhan, L.; Tang, W.; Wang, Q.; Dai, Z.; Zhou, L.; Feng, T.; Chen, M.; Wu, T.; Hu, E.; et al. MicrobiotaProcess: A Comprehensive R Package for Deep Mining Microbiome. The Innovation 2023, 4, 100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, G.A.; Neto, P.S.M.; Nociti, R.P.; Santana, Á.E. Hematological Normality, Serum Biochemistry, and Acute Phase Proteins in Healthy Beef Calves in the Brazilian Savannah. Animals 2023, 13, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geletu, U.S.; Usmael, M.A.; Mummed, Y.Y.; Ibrahim, A.M. Quality of Cattle Meat and Its Compositional Constituents. Vet. Med. Int. 2021, 2021, 7340495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Nelson, C.D.; Driver, J.D.; Elzo, M.A.; Jeong, K.C. Animal Breed Composition Is Associated With the Hindgut Microbiota Structure and β-Lactam Resistance in the Multibreed Angus-Brahman Herd. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.-B.; Meng, J.-X.; Ma, H.; Liu, R.; Qin, Y.; Qin, Y.-F.; Geng, H.-L.; Ni, H.-B.; Zhang, X.-X. Description of Gut Mycobiota Composition and Diversity of Caprinae Animals. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0242422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfrey, L.W.; Walters, W.A.; Lauber, C.L.; Clemente, J.C.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Teiling, C.; Kodira, C.; Mohiuddin, M.; Brunelle, J.; Driscoll, M.; et al. Communities of Microbial Eukaryotes in the Mammalian Gut within the Context of Environmental Eukaryotic Diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Chen, Y.; Wu, H.; Meng, Q.; Guan, L.L. Metatranscriptomic Profiling Reveals the Effect of Breed on Active Rumen Eukaryotic Composition in Beef Cattle With Varied Feed Efficiency. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramayo-Caldas, Y.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.; Zingaretti, L.M.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, O.; Dalmau, A.; Quintanilla, R.; Ballester, M. Gut Eukaryotic Communities in Pigs: Diversity, Composition and Host Genetics Contribution. Anim. Microbiome 2020, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Yan, X.; Xia, L.; Yao, G. Differences in Meat Quality between Angus Cattle and Xinjiang Brown Cattle in Association with Gut Microbiota and Its Lipid Metabolism. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghio, M.; Ciucci, F.; Buccioni, A.; Cappucci, A.; Casarosa, L.; Serra, A.; Conte, G.; Viti, C.; McAmmond, B.M.; Van Hamme, J.D.; et al. Correlation of Breed, Growth Performance, and Rumen Microbiota in Two Rustic Cattle Breeds Reared Under Different Conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, S.; Li, J.; Kuang, Y.; Feng, J.; Wang, H.; Niu, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Nie, C. Differential Microbial Composition and Interkingdom Interactions in the Intestinal Microbiota of Holstein and German Simmental × Holstein Cross F1 Calves: A Comprehensive Analysis of Bacterial and Fungal Diversity. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Lu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, D.; Zhang, M.; O’Connor, P.; Wei, F.; Zhu, Y.-G. Insights into the Roles of Fungi and Protist in the Giant Panda Gut Microbiome and Antibiotic Resistome. Environ. Int. 2021, 155, 106703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, I.; Kim, M.J. Comparison of Gut Microbiota of 96 Healthy Dogs by Individual Traits: Breed, Age, and Body Condition Score. Animals 2021, 11, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wei, S.; Chen, N.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Characteristics of Gut Microbiota in Pigs with Different Breeds, Growth Periods and Genders. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meineri, G.; Martello, E.; Atuahene, D.; Miretti, S.; Stefanon, B.; Sandri, M.; Biasato, I.; Corvaglia, M.R.; Ferrocino, I.; Cocolin, L.S. Effects of Saccharomyces Boulardii Supplementation on Nutritional Status, Fecal Parameters, Microbiota, and Mycobiota in Breeding Adult Dogs. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, L.; Xu, Y.; Liu, N.; Sun, X.; Hu, L.; Huang, H.; Wei, K.; Zhu, R. Dynamic Distribution of Gut Microbiota in Goats at Different Ages and Health States. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, C.; Estrada, R.; Oros, O.; Sánchez, D.; Maicelo, J.L.; Arbizu, C.I.; Coila, P. Alterations in the Gut Microbial Composition and Diversity Associated with Diarrhea in Neonatal Peruvian Alpacas. Small Rumin. Res. 2024, 235, 107273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.; Olsen, K.D.; Ricks, N.J.; Dill-McFarland, K.A.; Suen, G.; Robinson, T.F.; Chaston, J.M. Bacterial Communities in the Alpaca Gastrointestinal Tract Vary With Diet and Body Site. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, R.; Romero, Y.; Figueroa, D.; Coila, P.; Hañari-Quispe, R.D.; Aliaga, M.; Galindo, W.; Alvarado, W.; Casanova, D.; Quilcate, C. Effects of Age in Fecal Microbiota and Correlations with Blood Parameters in Genetic Nucleus of Cattle. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, P.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Lu, Q.; Xi, D.; Yang, R.; Wang, S.; Bai, W.; Yang, Z.; et al. The Composition of Fungal Communities in the Rumen of Gayals (Bos Frontalis), Yaks (Bos Grunniens), and Yunnan and Tibetan Yellow Cattle (Bos Taurs). Pol. J. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Niu, Y.; Wang, H.; Qin, S.; Zhang, R.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Xu, Y.; Yang, C. Effects of Three Different Plant-Derived Polysaccharides on Growth Performance, Immunity, Antioxidant Function, and Cecal Microbiota of Broilers. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Cidan, Y.; Sun, G.; Li, X.; Shahid, M.A.; Luosang, Z.; Suolang, Z.; Suo, L.; Basang, W. Comparative Analysis of Gut Fungal Composition and Structure of the Yaks under Different Feeding Models. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, A.E.; Mazel, F.; Lemay, M.A.; Morien, E.; Billy, V.; Kowalewski, M.; Di Fiore, A.; Link, A.; Goldberg, T.L.; Tecot, S.; et al. Biodiversity of Protists and Nematodes in the Wild Nonhuman Primate Gut. ISME J. 2020, 14, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, W.; Li, G.; Xue, B.; Feng, Y.; Tang, S.; Wei, W.; Yuan, H. Eukaryotes May Play an Important Ecological Role in the Gut Microbiome of Graves’ Disease. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubik, M.; Pilecki, B.; Moeller, J.B. Commensal Intestinal Protozoa—Underestimated Members of the Gut Microbial Community. Biology 2022, 11, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tsedan, G.; Liu, Y.; Hou, F. Shrub Coverage Alters the Rumen Bacterial Community of Yaks (Bos Grunniens) Grazing in Alpine Meadows. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2020, 62, 504–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Bai, J.; Gao, Y.; Ru, X.; Bi, C.; Li, J.; Shan, A. Effects of Sex on Fat Deposition through Gut Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Weaned Pigs. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 17, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Morrison, M.; Yu, Z. Evaluation of Different Partial 16S rRNA Gene Sequence Regions for Phylogenetic Analysis of Microbiomes. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011, 84, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, H.J.; Scott, K.P.; Duncan, S.H.; Louis, P.; Forano, E. Microbial Degradation of Complex Carbohydrates in the Gut. Gut Microbes 2012, 3, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopherson, M.R.; Dawson, J.A.; Stevenson, D.M.; Cunningham, A.C.; Bramhacharya, S.; Weimer, P.J.; Kendziorski, C.; Suen, G. Unique Aspects of Fiber Degradation by the Ruminal Ethanologen Ruminococcus Albus 7 Revealed by Physiological and Transcriptomic Analysis. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.J.; Wearsch, P.A.; Veloo, A.C.M.; Rodriguez-Palacios, A. The Genus Alistipes: Gut Bacteria With Emerging Implications to Inflammation, Cancer, and Mental Health. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourrisson, C.; Scanzi, J.; Brunet, J.; Delbac, F.; Dapoigny, M.; Poirier, P. Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Fecal Microbiota in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients and Healthy Individuals Colonized With Blastocystis. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamanikam, A.; Isa, M.N.M.; Samudi, C.; Devaraj, S.; Govind, S.K. Gut Bacteria Influence Blastocystis Sp. Phenotypes and May Trigger Pathogenicity. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, D.; Zapata, C.; Romero, Y.; Flores-Huarco, N.H.; Oros, O.; Alvarado, W.; Quilcate, C.; Guevara-Alvarado, H.M.; Estrada, R.; Coila, P. Parasitism-Induced Changes in Microbial Eukaryotes of Peruvian Alpaca Gastrointestinal Tract. Life 2024, 14, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, G.; Vega, L.; Patarroyo, M.A.; Ramírez, J.D.; Muñoz, M. Gut Microbiota Composition in Health-Care Facility-and Community-Onset Diarrheic Patients with Clostridioides Difficile Infection. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, L.-G.; Choi, G.; Kim, S.-W.; Kim, B.-Y.; Lee, S.; Park, H. The Combination of Sport and Sport-Specific Diet Is Associated with Characteristics of Gut Microbiota: An Observational Study. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2019, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Páez, A.; Gómez del Pugar, E.M.; López-Almela, I.; Moya-Pérez, Á.; Codoñer-Franch, P.; Sanz, Y. Depletion of Blautia Species in the Microbiota of Obese Children Relates to Intestinal Inflammation and Metabolic Phenotype Worsening. mSystems 2020, 5, 10.1128/msystems.00857-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Han, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yu, Q. Metagenomic and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal the Differences and Associations Between the Gut Microbiome and Muscular Genes in Angus and Chinese Simmental Cattle. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; An, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, K.; Kulyar, M.F.-E.-A.; Duan, K.; Zhou, H.; Wu, Y.; Wan, X.; Li, J.; et al. Integrated Bacteria-Fungi Diversity Analysis Reveals the Gut Microbial Changes in Buffalo With Mastitis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 918541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigore, D.-M.; Mironeasa, S.; Ciurescu, G.; Ungureanu-Iuga, M.; Batariuc, A.; Babeanu, N.E. Carcass Yield and Meat Quality of Broiler Chicks Supplemented with Yeasts Bioproducts. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, H. Rhodotorula Spp. in the Gut – Foe or Friend? GMS Infect. Dis. 2019, 7, Doc02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Huang, K.; Xie, W.; Xu, C.; Yao, Q.; Liu, Y. Effects of Rhodotorula Mucilaginosa on the Immune Function and Gut Microbiota of Mice. Front. Fungal Biol. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa-Seki, M.; Fereig, R.M.; Masatani, T.; Kinami, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Kida, K.; Nishikawa, Y. Development of CpGP15 Recombinant Antigen of Cryptosporidium Parvum for Detection of the Specific Antibodies in Cattle. Parasitol. Int. 2019, 69, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Zou, W.; Chen, X.; Sun, G.; Cidan, Y.; Almutairi, M.H.; Dunzhu, L.; Nazar, M.; Mehmood, K.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Effects of Cryptosporidium Parvum Infection on Intestinal Fungal Microbiota in Yaks (Bos Grunniens). Microb. Pathog. 2023, 183, 106322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooh, P.; Thébault, A.; Cadavez, V.; Gonzales-Barron, U.; Villena, I. Risk Factors for Sporadic Cryptosporidiosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microb. Risk Anal. 2021, 17, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, U.; Power, M. Cryptosporidium Species in Australian Wildlife and Domestic Animals. Parasitology 2012, 139, 1673–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, D.B.; Gzyl, K.E.; Scott, H.; Prieto, N.; López-Campos, Ó. Cara Service Associations between the Rumen Microbiota and Carcass Merit and Meat Quality in Beef Cattle. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, C. Modulation of Gut Microbiota and Immune System by Probiotics, Pre-Biotics, and Post-Biotics. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; Hao, W.; Yin, W.; Ai, S.; Han, J.; Wang, R.; Duan, Z. Depicting Fecal Microbiota Characteristic in Yak, Cattle, Yak-Cattle Hybrid and Tibetan Sheep in Different Eco-Regions of Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00021-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Chen, H.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, F.; Ruan, G.; Ying, S.; Tang, W.; Chen, L.; Chen, M.; Lv, L.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Relieves Gastrointestinal and Autism Symptoms by Improving the Gut Microbiota in an Open-Label Study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Guo, P.; Mao, R.; Ren, Z.; Wen, J.; Yang, Q.; Yan, T.; Yu, J.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y. Gut Microbiota Signature of Obese Adults Across Different Classifications. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2022, 15, 3933–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Lordan, C.; Ross, R.P.; Cotter, P.D. Gut Microbes from the Phylogenetically Diverse Genus Eubacterium and Their Various Contributions to Gut Health. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1802866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bay, V.; Gillespie, A.; Ganda, E.; Evans, N.J.; Carter, S.D.; Lenzi, L.; Lucaci, A.; Haldenby, S.; Barden, M.; Griffiths, B.E.; et al. The Bovine Foot Skin Microbiota Is Associated with Host Genotype and the Development of Infectious Digital Dermatitis Lesions. Microbiome 2023, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhan, H.; Xu, W.; Yan, S.; Ng, S.C. The Role of Gut Mycobiome in Health and Diseases. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 17562848211047130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Aschenbrenner, D.; Yoo, J.Y.; Zuo, T. The Gut Mycobiome in Health, Disease, and Clinical Applications in Association with the Gut Bacterial Microbiome Assembly. Lancet Microbe 2022, 3, e969–e983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeš, J.; Stensvold, C.R.; Jirků-Pomajbíková, K.; Parfrey, L.W. Are Human Intestinal Eukaryotes Beneficial or Commensals? PLOS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforest-Lapointe, I.; Arrieta, M.-C. Microbial Eukaryotes: A Missing Link in Gut Microbiome Studies. mSystems 2018, 3, 10.1128/msystems.00201-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizoguchi, Y.; Guan, L.L. Translational Gut Microbiome Research for Strategies to Improve Beef Cattle Production Sustainability and Meat Quality. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, C.; Teng, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, B.; Niu, Y.; Ma, L.; Yan, X. Multi-Omics Analysis Reveals Gut Microbiota-Induced Intramuscular Fat Deposition via Regulating Expression of Lipogenesis-Associated Genes. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 9, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feed Type | Amount | Dry Matter | Moisture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn Silage | 3% of body weight | 24%-26% | 74%-76% |

| Balanced Feed | 2 kg | 90% | 10% |

| Crude Protein | 14% |

| Bacteria | Fungi | Protists | ||||||||||

| Unweighted unifrac | Jaccard | Unweighted unifrac | Jaccard | Unweighted unifrac | Jaccard | |||||||

| Items | R2 | p | R2 | p | R2 | p | R2 | p | R2 | p | R2 | p |

| Race | 0.22 | 0.001** | 0.22 | 0.001** | 0.21 | 0.058 | 0.22 | 0.001** | 0.27 | 0.004** | 0.23 | 0.003** |

| Sex | 0.05 | 0.022* | 0.05 | 0.035* | 0.07 | 0.027* | 0.05 | 0.036* | 0.05 | 0.225 | 0.05 | 0.058 |

| Race:Sex | 0.19 | 0.083 | 0.19 | 0.045* | 0.15 | 0.691 | 0.17 | 0.438 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.082 |

| Fungi | Jaccard | Unweighted Unifrac | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mantel test | Partial Mantel test | Mantel test | Partial Mantel test | |||||

| Variables | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p |

| NGM1 | 0.22821 | 0.016 | 0.23833 | 0.017 | - | - | - | - |

| NGM2 | 0.19406 | 0.033 | 0.20089 | 0.036 | - | - | - | - |

| WBC | - | - | - | - | 0.22348 | 0.019 | 0.1771 | 0.041 |

| WEIGHT | - | - | - | - | 0.28379 | 0.015 | 0.22588 | 0.044 |

| RBC | - | - | - | - | 0.26543 | 0.031 | - | - |

| MCV | - | - | - | - | 0.27068 | 0.019 | - | - |

| MCHC | - | - | - | - | 0.25847 | 0.025 | - | - |

| NEU | - | - | - | - | 0.19148 | 0.038 | - | - |

| SEG | - | - | - | - | 0.19148 | 0.039 | - | - |

| Protists | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p |

| MON | - | - | - | - | 0.19531 | 0.013 | 0.20835 | 0.008 |

| PLT | 0.22961 | 0.021 | 0.2268 | 0.024 | 0.16086 | 0.026 | 0.1609 | 0.026 |

| GL | - | - | - | - | 0.25734 | 0.01 | 0.27912 | 0.006 |

| AL | - | - | - | - | 0.13362 | 0.033 | 0.1335 | 0.044 |

| NEU% | 0.21743 | 0.031 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).