1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are a group of viruses that mostly infect humans and wide range of animal species [

1]. They can cause different kinds of diseases, ranging from mild to severe respiratory, hepatic, and neurologic conditions [

2,

3]. SARS-CoV-2 is the third coronavirus that can pass from animals to humans, after SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV [

4], and the seventh coronavirus that can infect humans [

5]. It is the cause of the COVID-19 outbreak that emerged in December 2019 [

6]. Many human coronaviruses like HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV are believed to have originated in bats [

7,

8]. Additionally, CoV-OC43 and CoV-HKU1 are thought to have passed from rodents to humans [

9,

10]. However, the details of how these coronaviruses evolve in bats are still unknown, and the exact pathways through which they are transmitted from natural reservoirs to humans remain to be fully elucidated.

Coronaviruses have four main types of proteins: spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) [

11]. In SARS-CoV-2, the genome is protected by the N protein, which is closely associated with the M protein, often called the matrix protein. The outer envelope of the virus is made up of the E protein [

11,

12]. The N protein helps the virus replicate and has two parts: the N-terminal domain and the C-terminal domain, both of which can bind to RNA on their own [

13,

14,

15]. The E and M proteins are crucial for assembling the virus, its pathogenesis, and budding off from cells [

16,

17]. Meanwhile, the S proteins on the virus’s surface form trimers and are key for recognizing and entering host cells [

18,

19].

Molecular and phylogenetic analysis could yield an important understanding of how viruses evolve and spread [

20]. Though this method may not generally provide immediate clinical solutions, it offers promise for developing targeted therapies [

21,

22]. From the onset of the COVID 19 pandemic till date, plenty studies have been conducted to understand the phylogenetic relationships and immunogenic potential of different coronaviruses. In one comprehensive study, Oliviera and colleagues identified conserved B and T cell epitopes in the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein [

23]. However, the study was limited to nucleocapsid protein, overlooking other important viral proteins, such as the spike protein which plays crucial role in immune response and vaccine efficacy [

24,

25]. In addition, failure to account for all relevant coronaviruses could limit the discovery of many potential cross-reactive epitopes. Similarly, Chen and colleagues conducted a phylogenetic analysis to trace the evolutionary origin and unique niche among human coronaviruses—SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and MERS-CoV [

26]. While their findings provided insights into evolutionary history, they mainly come from phylogenetic analyses, which might not capture all the factors affecting how the virus evolves and adapts to hosts. Another recent study by Lopes used bioinformatics to explore possible cross-reaction between SARS-CoV-2 and other mammalian coronaviruses by identifying similar protein regions [

27]. However, like Oliviera's work, it failed to account for all relevant viral strains.

In summary, while recent studies have shed powerful light on the phylogenetic interconnections among coronaviruses [

28,

29,

30,

31], they often focus on only a subset of viral proteins or strains [

23,

24,

26,

27]. Few studies have comprehensively addressed both the phylogenetic and immunogenic aspects of coronaviruses considering all relevant strains and functional proteins [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Furthermore, the detailed mechanisms of the evolutionary changes and the structural adaptations owing to glycosylation and receptor binding in coronaviruses remain underexplored.

In this study we aimed to address these limitations by examining all relevant coronaviruses and their protein sequences to gain insights into their ancestral relatedness, cross-reactive epitopes, and potential immune escape mechanisms. Briefly, we leveraged web-based tools to determine whether different coronaviruses structural and antigenic variations could yield insights into their evolutionary relationships and ability to escape the immune system. This study could provide crucial insight to support the further development of vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostic tools, as well as for preparing for future outbreaks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Coronavirus Sequence Data Source

The nucleotide and protein sequences of the four viral proteins were extracted in FASTA format from the Microbial Genomes and Protein Resources at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov]. Among the list are sequences for SARS-CoV-2, BatCoV BM48-3, HCoV-229E, HCoV-HKU1, Ty-BatCoV HKU4, Ty-BatCoV HKU33, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, Pangolin-CoV, BatCoV RaTG13, and Pi-BatCoV HKU5, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 (refer to Supplementary Table 1 for details).

2.2. Antigenic Variation Prediction

To assess the variation among structural viral proteins from various coronaviruses, we performed pairwise sequence alignments using EMBOSS Needle software (version 6.6.0) available at

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/psa/emboss_needle/ [

36]. EMBOSS Needle aligns two input sequences globally using the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm. The alignment parameters included a gap open penalty of 10, a gap extend penalty of 0.5, and the BLOSUM62 protein alignment matrix. The software computes the optimal alignment along the entire length of the sequences, including gaps. We analyzed the percentage of gaps, similarity, and identity in the alignments, as well as the alignment length and score.

2.3. Antigenic Relationship and Structural Divergence

Amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalW. We then used Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) X software to construct phylogenetic trees for the spike glycoproteins, nucleocapsid, envelope, and membrane proteins [

37]. The analysis employed the maximum composite likelihood method and the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) [

38,

39]. This approach assessed the structural divergence of these proteins among the studied coronaviruses and evaluated their antigenic similarities.

2.4. Variation in Glycosylation Pattern of Spike Glycoproteins

Amino acid sequences of spike glycoproteins were analyzed using NetNGlyc 1.0 online software

https://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/ to predict glycosylation sites [

40]. This analysis aimed to identify differences in the glycosylation patterns of spike glycoproteins, which may affect viral attachment to host cell surfaces.

2.5. Prediction of Cleavage Sites

The cleavage sites for 3CL proteinase as well as furin were predicated for the spike glycoproteins. We used NETCorona

http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetCorona/ for the 3CL proteinase [

41]. The NETCorona utilizes artificial neural networks to to predict cleavage sites based on known sites from seven coronavirus family members, reflecting the conservation of these sites within the family.

For furin cleavage sites, ProP 1.0

https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/service.php?ProP-1.0 was utilized [

42]. This tool predicts cleavage positions based on arginine and lysine propeptides using neural networks. Additionally, the SignalP 3.0 server, integrated into ProP 1.0, was used to predict the presence and location of signal peptide cleavage sites. Predictions were considered significant with a score greater than 0.5.

2.6. Epitope Prediction and Variation in Spike Glycoprotein

To identify and compare Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes within the spike glycoproteins, we used the NetCTL 1.2 online tool

http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetCTL/ (Larsen et al., 2007). This software predicts CTL epitopes based on three key factors: the efficiency of transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP), proteasomal cleavage patterns, and MHC class I affinity. These predictions reveal variations in epitope presentation across different spike glycoproteins, proteasomal cleavage, and MHC class I affinity [

43,

44].

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analysis and Pairwise Sequence Alignment of Coronavirus Proteins

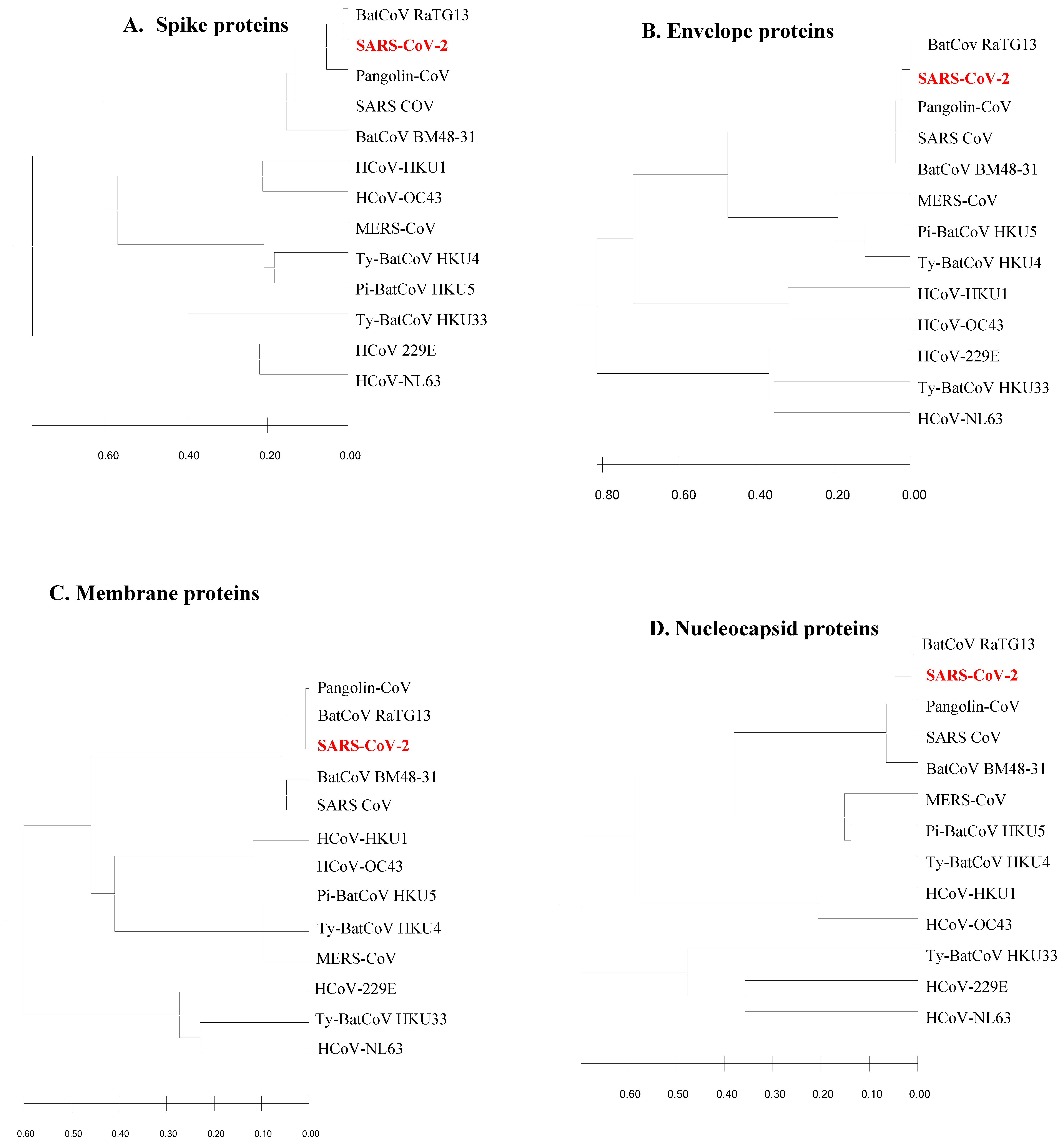

The phylogenetic trees constructed from the structural viral proteins (spike, membrane, envelope and nucleocapsid) demonstrated the ancestral origin and distant evolutionary relationships of the newly emerged SARS-CoV-2 (

Figure 1). It was found that SARS-CoV-2 was related to BatCoV RaTG13, Pangolin-CoV, Bat SARS CoV and BatCoV BM48-31. In all the trees, SARS-CoV-2 aligned with the same clade of BatCoV RaTG13, Pangolin-CoV, Bat SARS CoV and BaTCoV BM48-31. However, the phylogenetic analysis revealed that SARS-CoV-2, BatCoV RaTG13 and Pangolin-CoV originate from the same immediate common ancestor. Three bat-originated coronaviruses; HKU4, HKU5 and HKU33, and five human-originated coronaviruses; MERS, HKU1, OC43, 229E and NL63, were found to have divergent relationships with SARS-CoV-2. However, Ty-BatCoV HKU4 and Pi-BatCoV HKU5 showed ancestral relationships with MERS-CoV. Moreover, HKU33, of bat origin, always showed a phylogenetic relationship with the human-originated coronaviruses 229E and NL63. Three bat-originated coronaviruses (HKU4, HKU5, and HKU33) and five human-originated coronaviruses (MERS, HKU1, OC43, 229E, and NL63) were found to have divergent relationships with SARS-CoV-2, suggesting their potential for future zoonotic spillovers and emphasizing the need for continuous viral monitoring.

The results suggest that major proteins of SARS-CoV-2 were more aligned with BatCoV RaTG13 and Pangolin CoV structural proteins. Pairwise sequence alignment by EMBOSS Needle strengthened the phylogenetic relationship of SARS-CoV-2, BatCoV RaTG13 and Pangolin CoV. The identical and similarity patterns of SARS-CoV-2 proteins with their homologous proteins of other coronaviruses is indicated in

Table 2. It has been revealed that SARS-CoV-2 proteins were highly similar and identical to BatCoV RaTG13 and Pangolin CoV than SARS-COV proteins. The spike, envelope, membrane and nucleocapsid proteins of SARS-CoV-2 showed approximately (89.8% and 97.3%), (100% and 100%), (97.7% and 99.1%) and (97.1% and 98.3%) nucleotide similarities with the respective protein molecules of Pangolin CoV and BatCoV RaTG13. Again, in the case of identity pattern, results showed that spike, envelope, membrane and nucleocapsid proteins of SARS-CoV-2 were (94.0% and 98.2%), (100% and 100%), (98.6% and 99.1%), and (98.1% and 98.6%) identical with the respective homologous proteins of Pangolin CoV and BatCoV RaTG13.

3.2. Antigenic Site Determination and Epitope Variation Analysis

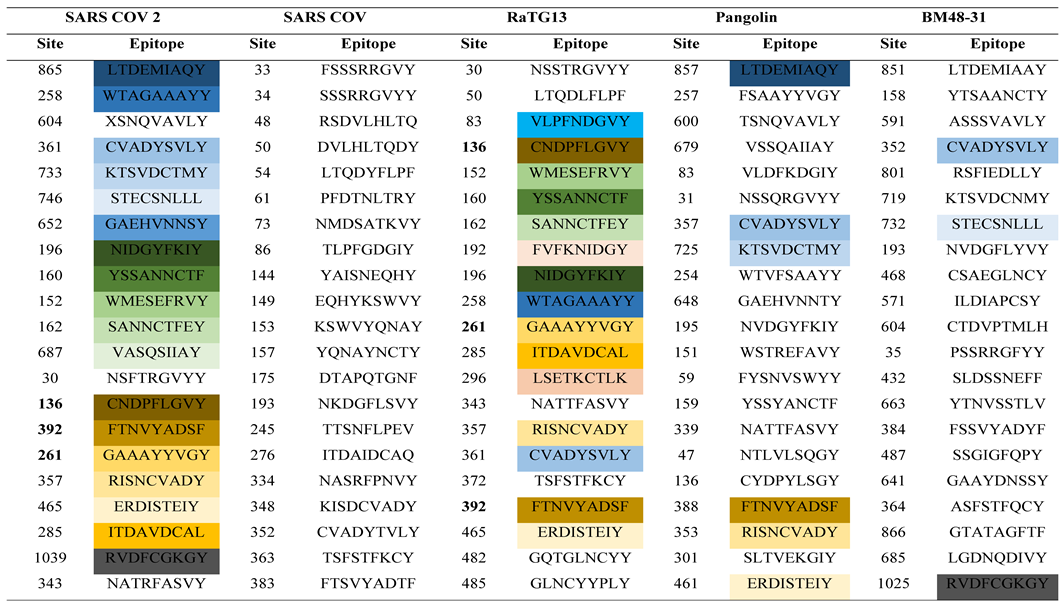

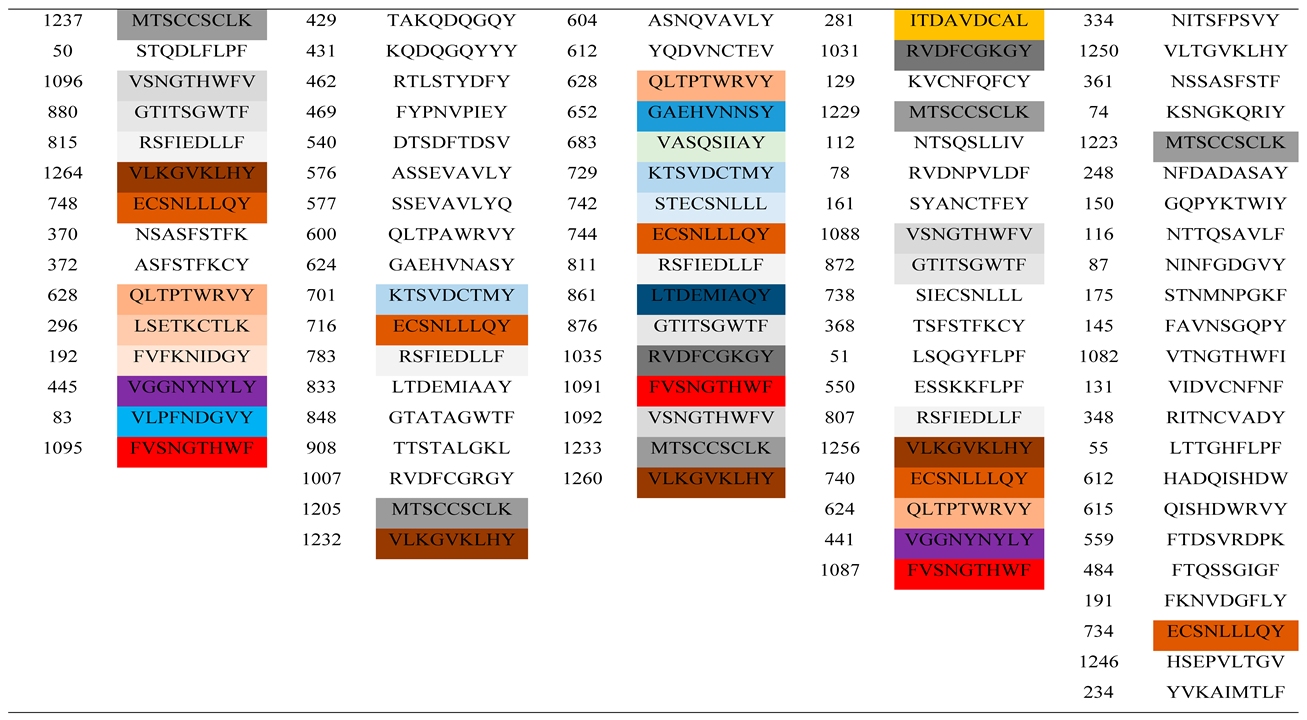

The spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-COV, BatCoV RaTG13, BatCoV BM48-31 and Pangolin CoV were used to determine the most antigenic sites by employing the NetCTL 1.2 epitope prediction tool. The NetCTL server, which gave a score well above the threshold value of 0.75, revealed the antigenic potential required to stimulate a protective response in host organisms (Flower et al., 2017). From the analysis, a total of 37 epitopes from the S proteins were found to be mostly antigenic in SARS-CoV-2, with almost 100% of peptides carrying more than the threshold value of the antigenic score of the NetCTL server (

Table 3). Similarly, the other four coronaviruses (SARS-COV, BatCoV RaTG13, BatCoV BM48-31 and Pangolin CoV) also showed the presence of epitopic candidates in their spike proteins with values exceeding the antigenic threshold. Moreover, there were variation among the peptides present at the various epitopes in the spike proteins of the five coronaviruses including the recently emerged coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

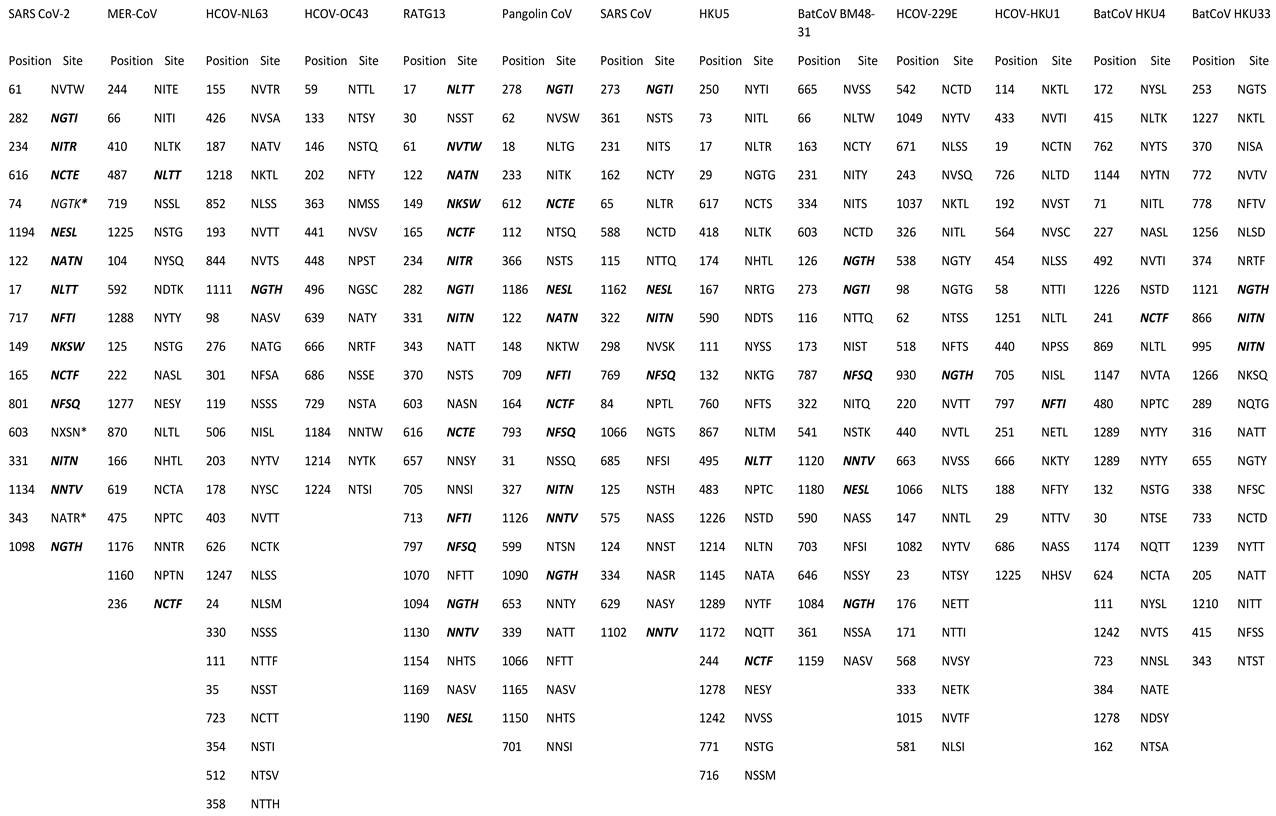

3.3. Comparative Analysis and Prediction of Spike Glycoprotein Glycosylation Sites

The glycosylation sites for the retrieved spike glycoproteins of the various coronaviruses were predicted (

Table 4). A comparative analysis has demonstrated that 14 of SARS-COV-2 glycosylation sites can be found in other coronaviruses. Besides, three (3) novel glycosylation sites (NGTK, NXSN and NATR) were found in SARS-CoV-2. BatCoV RaTG13 had the most common sites (14) with SARS-COV-2, followed by Pangolin CoV (10), BatCoV BM48-31 (6), SARS-CoV (5), BatCoV HKU33 (5), BatCoV HKU5 and MERS-CoV (2), and CoV-229E, CoV-HKU1 and BatCoV HKU4 (1). None of the predicted glycosylation sites of CoV-OC43 and SARS-CoV-2 were common. These novel epitopes identified in SARS-CoV-2 can be critical for the development of peptide-based vaccines and should be prioritized for experimental validation.These glycosylation sites play crucial roles in viral infectivity and immune evasion, and their novel positions in SARS-CoV-2 could provide insights for antiviral drug design targeting glycosylation processes.

3.4. Predicted Cleavage Sites and Site Position of the Retrieved Spike Glycoproteins

The 3CL pro cleavage site was predicted for SARS-CoV-2, BatCoV BM48-3, BatCoV RaTG13, Pangolin CoV, SARS-COV, BatCoV HKU5, BatCoV HKU4, CoV-229E and CoV-NL63, whilst no 3CL pro cleavage site was predicted for MERS-CoV, BatCoV HKU33, CoV-HKU1 and CoV- OC43 (

Table 5). By comparing the predicted cleavage site position of the other coronaviruses spike glycoproteins to SARS-COV-2 predicted cleavage sites, BatCoV RaTG13 had the nearest cleavage site position to SARS-CoV-2 cleavage site, followed by Pangolin CoV, BatCoV BM48-31 and SARS-CoV. This variation in cleavage sites can inform the development of specific inhibitors targeting these protease sites to hinder viral replication.

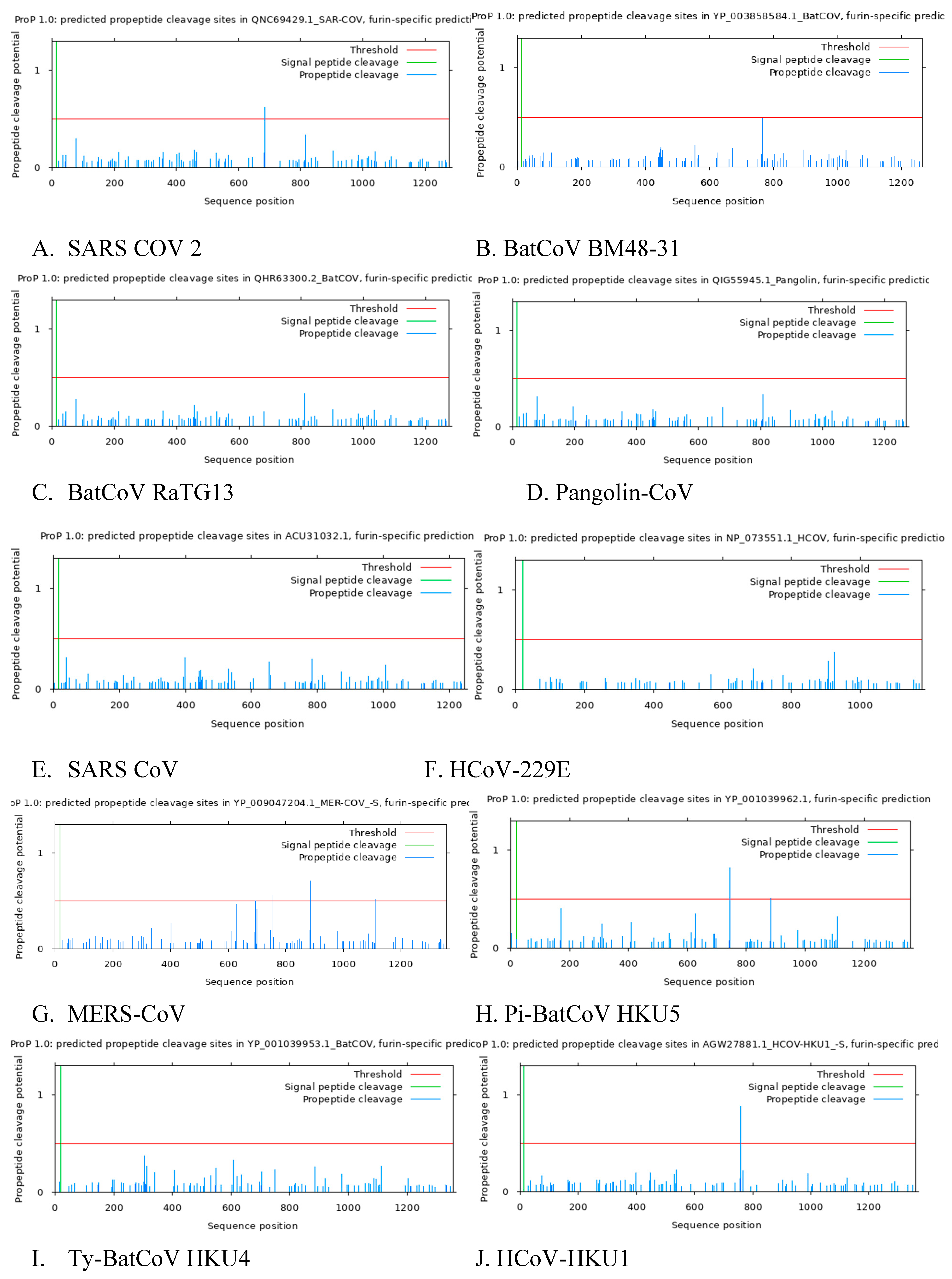

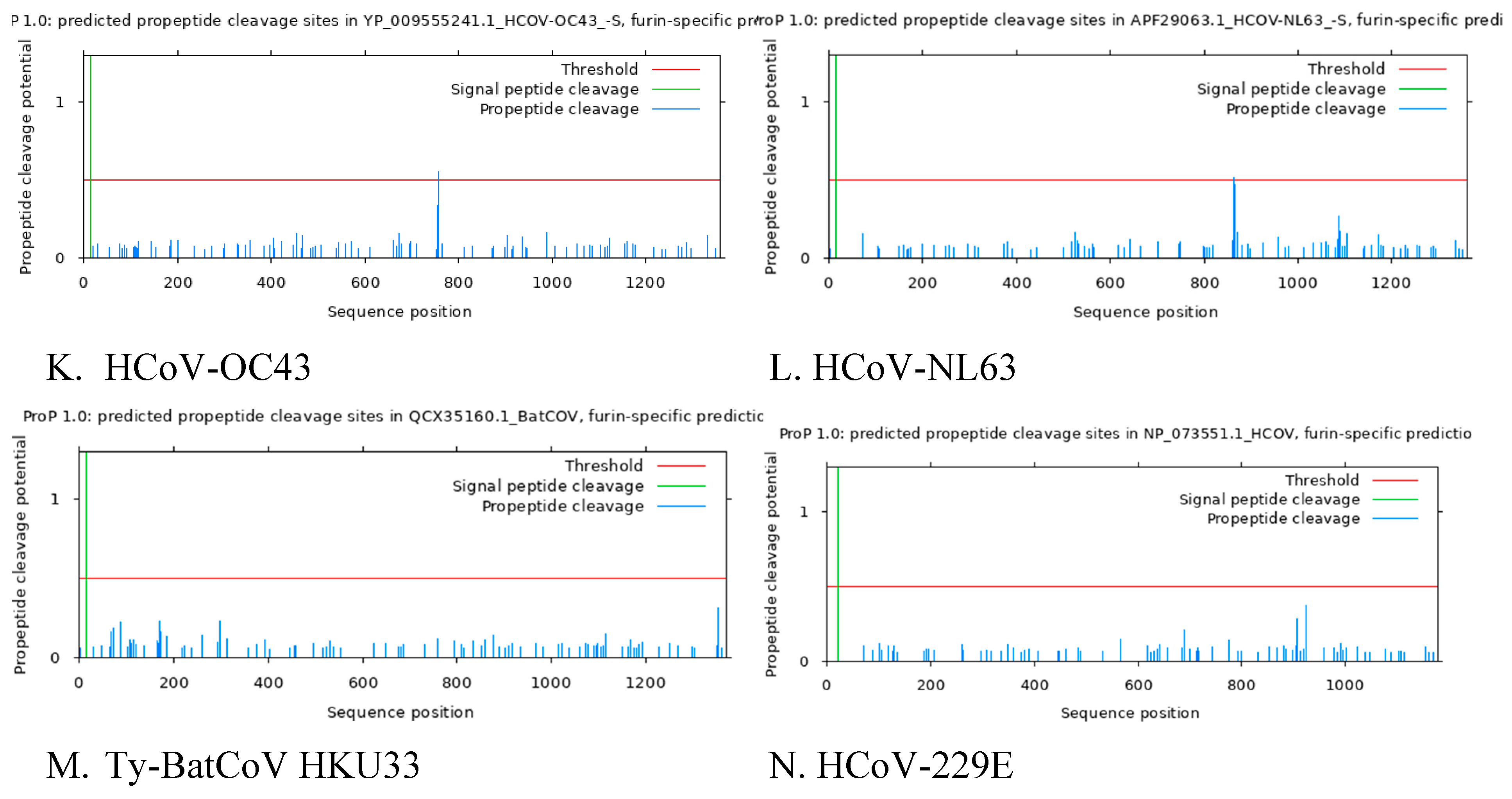

3.5. Predicted Furin Cleavage Site and Signal Peptide Cleavage Site

Predictive analysis reveal the presence of Furin cleavage site in SARS CoV 2, Pi-BatCoV HKU5, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-HKU1, HCoV-OC43, MERS-CoV but furin cleavage maturation in SARS CoV, BatCoV BM48-31, BatCoV RaTG13, Pangolin-CoV, HCoV-229E, Ty-BatCoV HKU4 ,Ty-BatCoV HKU33 was absent. This analysis confirms that among coronaviruses in the subgenus

Sarbecovirus, Sars CoV 2, BatCoV RaTG13, Pangolin-CoV and Sars CoV, Sars Cov 2 is the only Sarbecovirusvirus with furin cleavage site SI/S2 (

Figure 2A, B, C, D, E). The presence of this unique furin cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2 may account for its high infectivity and could be targeted in therapeutic strategies to mitigate viral entry into host cells.

Table 6.

Summary of predicted furin cleavage site among coronaviruses.

Table 6.

Summary of predicted furin cleavage site among coronaviruses.

| Coronavirus |

Furin Cleavage site position |

sequence |

Score |

Signal peptide cleavage position |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

685 |

NSPRRAR|SV |

0.620 |

13 and 14 |

| BatCoV BM48-31 |

NONE |

|

None |

15 and 16 |

| BatCoV RaTG13 |

NONE |

|

None |

13 and 14 |

| Pangolin-CoV |

NONE |

|

None |

14 and 15 |

| Pi-BatCoV HKU5 |

745 |

TSSRVRR|AT |

0.822 |

21 and 22 |

| 884 |

TGERKYR|ST |

0.507 |

| HCoV-229E |

NONE |

|

None |

21 AND 22 |

| Ty-BatCoV HKU4 |

NONE |

|

None |

20 and 21 |

| HCoV-NL63 |

863 |

LPQRNIR|SS |

0.519 |

15 and 16 |

| Ty-BatCoV HKU33 |

NONE |

|

NONE |

16 and17 |

| MERS-CoV |

751 |

LTPRSVR|SV |

0.563 |

17 and 18 |

| 887 |

TGSRSAR|SA |

0.707 |

| 1113 |

VKAQSKR|SG |

0.512 |

HCoV-HKU1

AGW27881.1 |

759 |

SSSRRKR|RS |

0.675 |

13 and 14 |

| 758 |

SSRRKRR|SI |

0.878 |

| HCoV-OC43 |

757 |

SKNRRSR|GA |

0.551 |

14 and 15 |

| SARS CoV |

NONE |

|

NONE |

15 and 16 |

4. Discussion

Human coronaviruses evolve from zoonotic transmission, and bats are commonly reported as reservoirs for such zoonotic viruses [

45]. While COVID-19 is no longer a pandemic, understanding the genetic and structural characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and related coronaviruses remains crucial for future preparedness. Our findings suggest that the unique features of SARS-CoV-2, including the novel glycosylation sites and distinct furin cleavage sites, may potentially contribute to the higher infectivity. This may ultimately provide valuable targets for developing broad-spectrum vaccines and antiviral therapies.

The output from the phylogenetics tree demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2, Pangolin-CoV and BatCoV RaTG13 share similar characteristics, and pairwise alignment indicated maximum similarity and identity between these variants. These findings are in accordance with previous studies that reported similar results [

46,

47,

48,

49]. Considering the diversity and similarities among coronaviruses, it is evident that frequent genetic recombination among various strains might lead to the emergence of new coronaviruses [

50,

51]. Like other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 shares similarities with the six coronaviruses that infect humans but our phylogenetic studies suggest that SARS-CoV-2 is not a direct descendant of any of the six. However, it represents a divergence from coronaviruses that infect humans

The pairwise sequence analysis of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoproteins with the other coronaviruses reveal a high similarity between RaTG13, Pangolin-CoV, Bat SARS CoV and BatCoV BM48-31, respectively. Although Pangolin-CoV and BatCoV RaTG13 revealed a 100% similarity in its envelope protein to SARS-CoV-2, a structural divergence was observed during the analysis of the nucleocapsid, membrane and spike proteins as BatCoV RaTG13 and Pangolin-CoV showed a similarity of 98.3% and 97.1% for nucleocapsid and 91.1% and 97.7% for membrane proteins. Accordingly, it is clear that the six human coronaviruses widely diverge from SARS-CoV-2 supporting the findings from the phylogenetic tree.

Antigenic epitope site determination analyses of coronavirus proteins were performed to determine the potential CTL epitopes that would interact efficiently with B lymphocytes to initiate an immune response against specific antigens [

52]. Epitope sites were determined for the spike glycoproteins of SARS-CoV-2, BatCoV RaTG13, Pangolin-CoV, Bat SARS CoV and BatCoV BM48-31. SARS-CoV-2 was identified to have a total of 36 highly immunogenic CTL epitopes followed by BatCoV RaTG13 (38), Pangolin-CoV (41), Bat SARS CoV (40), and BatCoV BM48-31 (45) epitopes. The antigenic sites of SARS-CoV-2 were also compared with the other four coronaviruses spike glycoproteins. Higher levels of conservation among antigenic epitope sites of SARS-CoV-2, BatCoV RaTG13 and Pangolin-CoV were observed and this supports the claim that SARS-CoV-2, BatCoV RaTG13 and Pangolin-CoV evolve from a more recent ancestor [

47,

53]. Comparison between the antigen recognition site of SARS-CoV-2 and Bat SARS CoV spike glycoproteins showed a wide structural diversity among the two strains. Hence, it is evident that therapeutic agents used for treating severe acute respiratory syndrome diseases cannot be effective and efficient against COVID-19 [

54,

55]. Screening of predicted epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoproteins with BatCoV RaTG13, Pangolin-CoV, Bat SARS CoV and BatCoV BM48-31 revealed six new CTL epitopes; XSNQVAVLY, NSFTRGVYY, NATRFASVY, STQDLFLPF, NSASFSTFK and ASFSTFKCY that may be responsible for the unique antigenic response of SARS-CoV-2. These novel CTL epitopes can be a target site for the development of peptide-based vaccine. The spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 is considered to be responsible for host specificity and is also the main receptor binding domain [

56].

The SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoproteins were found to share fourteen out of its seventeen glycosylation sites with other coronaviruses, with majority of its glycosylation sites found in BatCoV RaTG13 (14 glycosylation sites) and Pangolin-CoV. Additionally, three novel glycosylation sites—NATR, NXSN and NGTK—were identified in the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2, suggesting that the virus might use a unique glycosylation mechanism to interact with its receptors. These glycosylation sites are potential targets for antiviral drugs that can interfere with viral attachment and entry into host cells. Analysis of the spike glycoproteins using the 3C-like protease tool revealed that the cleavage site for SARS-CoV-2 is 1000 amino sequence away from the start codons of the spike glycoproteins. 3C-like protease cleaves proteins to generate functional proteins such as single-stranded RNA-binding protein, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (which is the main replicase of coronaviruses), helicase, exoribonuclease and endoribonuclease [

57]. A comparative analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 cleavage site position revealed that BatCoV RaTG13 has the nearest cleavage site to SARS-CoV-2 at 998, whiles Pangolin-CoV has its site at 994. BatCoV BM48-31 and Bat SARS-CoV also have nearby cleavage sites at 988 and 972, respectively. In contrast, other human coronaviruses showed a wide variation in cleavage site position suggesting a major difference in their spike receptor binding protein and mechanism of replication from SARS-COV-2, Pangolin-CoV, BatCoV RaTG13, BatCoV BM48-31 and Bat SARS CoV. These variations might stem from gaps observed during pairwise alignment, as all these gaps appeared before the cleavage site position. Inhibiting the activity of 3C-like protease prevents replication since viral replication apparatus will not be produced [

58,

59]. Cleavage sites can serve as a target site for drug design [

60]. Therefore, further research into designing 3C-like protease inhibitors against coronaviruses is warranted.

Furin is expressed at low level in the Golgi apparatus cells and has been shown to play a vital role in viral pathogenesis by cleaving polybasic or multi-basic sites such as those found in influenza virus subtypes H5, H7 and Mers CoV [

61,

62]. SARS-CoV-2 furin cleavage at the S1/S2 boundary primes the spike for an open conformation necessary for interaction to the ACE2 entrance receptor [

63,

64]. The presence of a unique furin cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2 at the S1/S2 boundary primes the spike for an open conformation necessary for interaction with the ACE2 receptor. This could explain the highly infectious nature of SARS-CoV-2 compared to phylogenetically closely related viruses of the Sarbecovirus subgenus. Targeting the furin cleavage site may be a promising therapeutic approach to block viral entry into host cells [

62,

65].

Taken together, future research should focus on validating the identified CTL epitopes and glycosylation sites through experimental studies, exploring their potential as targets for antiviral drugs and vaccines. Additionally, understanding the mechanisms behind the unique features of SARS-CoV-2, such as its furin cleavage site, can provide deeper insights into viral pathogenesis and inform the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

5. Conclusions

This study has revealed the genetic diversity among the structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2, BatCoV BM48-31, BatCoV RaTG13, Pangolin-CoV, Bat SARS CoV, Pi-BatCoV HKU5, HCoV-229E, Ty-BatCoV HKU4, HCoV-NL63, Ty-BatCoV HKU33, MERS-CoV, HCoV-HKU1, HCoV-OC43. The phylogenetic analysis of nucleocapsid, membrane, envelop and spike protein showed that SARS-CoV-2, BatCoV RaTG13 and Pangolin-CoV are closely related and evolved from an immediate common ancestor. Further characterization of spike glycoproteins using predicted epitopes, pairwise alignment, glycosylation site and cleavage site position proved that BatCoV RaTG13 is closely related to SARS-CoV-2 than the other coronaviruses. Also, SARS-CoV-2 showed six unique epitopes, three unique glycosylation sites and a unique furin cleavage site which can contribute to development of peptide-based vaccine as well as monitoring the consequences of glycosylation, enzyme cleavage and antigen binding variations during the process of SARS-CoV-2 infectivity.

References

- To, K. K., Hung, I. F., Chan, J. F., & Yuen, K. Y. (2013). From SARS coronavirus to novel animal and human coronaviruses. J Thorac Dis, 5 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), S103-108. [CrossRef]

- Hasöksüz, M., Kiliç, S., & Saraç, F. (2020). Coronaviruses and SARS-COV-2. Turk J Med Sci, 50(SI-1), 549-556. [CrossRef]

- Santacroce, L., Charitos, I. A., Carretta, D. M., De Nitto, E., & Lovero, R. (2021). The human coronaviruses (HCoVs) and the molecular mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Mol Med (Berl), 99(1), 93-106. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Vega, V. R., Monroy-Molina, J. V., Jiménez-Hernández, L. E., Torres, A. G., Santos-Preciado, J. I., & Rosales-Reyes, R. (2022). SARS-CoV-2: Evolution and Emergence of New Viral Variants. Viruses, 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N., & Lorusso, A. (2020). Novel human coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): A lesson from animal coronaviruses. Vet Microbiol, 244, 108693. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y. J., Wang, Y. L., Wang, M. Y., Zhou, L., Shi, J. Y., Cao, J. M., & Wang, D. P. (2022). The origins of COVID-19 pandemic: A brief overview. Transbound Emerg Dis, 69(6), 3181-3197. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z. W., Yuan, S., Yuen, K. S., Fung, S. Y., Chan, C. P., & Jin, D. Y. (2020a). Zoonotic origins of human coronaviruses. Int J Biol Sci, 16(10), 1686-1697. [CrossRef]

- Latif, A. A., & Mukaratirwa, S. (2020). Zoonotic origins and animal hosts of coronaviruses causing human disease pandemics: A review. Onderstepoort J Vet Res, 87(1), e1-e9. [CrossRef]

- Lau, S. K., Woo, P. C., Li, K. S., Tsang, A. K., Fan, R. Y., Luk, H. K.,…Yuen, K. Y. (2015). Discovery of a novel coronavirus, China Rattus coronavirus HKU24, from Norway rats supports the murine origin of Betacoronavirus 1 and has implications for the ancestor of Betacoronavirus lineage A. J Virol, 89(6), 3076-3092. [CrossRef]

- Narh, C. A. (2020). Genomic Cues From Beta-Coronaviruses and Mammalian Hosts Sheds Light on Probable Origins and Infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 Causing COVID-19. Front Genet, 11, 902. [CrossRef]

- Malik, Y. A. (2020). Properties of Coronavirus and SARS-CoV-2. Malays J Pathol, 42(1), 3-11.

- Sinha, S. K., Shakya, A., Prasad, S. K., Singh, S., Gurav, N. S., Prasad, R. S., & Gurav, S. S. (2021). An. J Biomol Struct Dyn, 39(9), 3244-3255. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Liu, Q., & Guo, D. (2020a). Emerging coronaviruses: Genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J Med Virol, 92(10), 2249. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., Siddique, R., Shereen, M. A., Ali, A., Liu, J., Bai, Q.,…Xue, M. (2020). Emergence of a Novel Coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2: Biology and Therapeutic Options. J Clin Microbiol, 58(5). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R., Zeng, R., von Brunn, A., & Lei, J. (2020). Structural characterization of the C-terminal domain of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. Mol Biomed, 1(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- J Alsaadi, E. A., & Jones, I. M. (2019a). Membrane binding proteins of coronaviruses. Future Virol, 14(4), 275-286. [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, D., & Fielding, B. C. (2019). Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol J, 16(1), 69. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D. E., Jang, G. M., Bouhaddou, M., Xu, J., Obernier, K., White, K. M.,…Krogan, N. J. (2020). A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature, 583(7816), 459-468. [CrossRef]

- Michel, C. J., Mayer, C., Poch, O., & Thompson, J. D. (2020). Characterization of accessory genes in coronavirus genomes. Virol J, 17(1), 131. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., & Rannala, B. (2012). Molecular phylogenetics: principles and practice. Nat Rev Genet, 13(5), 303-314. [CrossRef]

- Lam, T. T., Hon, C. C., & Tang, J. W. (2010). Use of phylogenetics in the molecular epidemiology and evolutionary studies of viral infections. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci, 47(1), 5-49. [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A., & Caetano-Anollés, G. (2015). A phylogenomic data-driven exploration of viral origins and evolution. Sci Adv, 1(8), e1500527. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S. C., de Magalhães, M. T. Q., & Homan, E. J. (2020). Immunoinformatic Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Identification of COVID-19 Vaccine Targets. Front Immunol, 11, 587615. [CrossRef]

- Khalaj-Hedayati, A. (2020). Protective Immunity against SARS Subunit Vaccine Candidates Based on Spike Protein: Lessons for Coronavirus Vaccine Development. J Immunol Res, 2020, 7201752. [CrossRef]

- Almehdi, A. M., Khoder, G., Alchakee, A. S., Alsayyid, A. T., Sarg, N. H., & Soliman, S. S. M. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: pathogenesis, vaccines, and potential therapies. Infection, 49(5), 855-876. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Boon, S. S., Wang, M. H., Chan, R. W. Y., & Chan, P. K. S. (2021). Genomic and evolutionary comparison between SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. J Virol Methods, 289, 114032. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L. R. (2024). SARS-CoV-2-identical protein regions found in mammalian coronaviruses have immunogenic potential and can imply cross-protection. ImmunoInformatics, 14, 100034.

- Jiang, S., Wu, S., Zhao, G., He, Y., Guo, X., Zhang, Z.,…Wang, B. (2022). Identification of a promiscuous conserved CTL epitope within the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Emerg Microbes Infect, 11(1), 730-740. [CrossRef]

- Phan, T. (2020). Genetic diversity and evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Infect Genet Evol, 81, 104260. [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, J. C., Martini, F., Maritati, M., Mazziotta, C., Di Mauro, G., Lanzillotti, C.,…Contini, C. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 Infection: New Molecular, Phylogenetic, and Pathogenetic Insights. Efficacy of Current Vaccines and the Potential Risk of Variants. Viruses, 13(9). [CrossRef]

- Forster, P., Forster, L., Renfrew, C., & Forster, M. (2020). Phylogenetic network analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 117(17), 9241-9243. [CrossRef]

- Klasse, P. J., Nixon, D. F., & Moore, J. P. (2021). Immunogenicity of clinically relevant SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in nonhuman primates and humans. Sci Adv, 7(12). [CrossRef]

- Li, T., Liu, D., Yang, Y., Guo, J., Feng, Y., Zhang, X.,…Feng, J. (2020). Phylogenetic supertree reveals detailed evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Sci Rep, 10(1), 22366. [CrossRef]

- Enayati, S., Ranjbar, M. M., Hooshmandi, S., Ahangarzadeh, S., & Aboutalebian, S. (2023). Molecular and Antigen Detection, Phylogenetics, and Immunoinformatics Study of the Zoonotic Coronavirus in Iranian Diarrheic Calves. Adv Biomed Res, 12, 224. [CrossRef]

- Sallard, E., Halloy, J., Casane, D., Decroly, E., & van Helden, J. (2021). Tracing the origins of SARS-COV-2 in coronavirus phylogenies: a review. Environ Chem Lett, 19(2), 769-785. [CrossRef]

- Needleman, S. B., and Wunsch, C. D. (1970). A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins. Journal of Molecular Biology, 48(3), 443–453. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C., and Tamura, K. (2018). MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35(6), 1547–1549. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K., Nei, M., and Kumar, S. (2004). Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(30), 11030–11035. [CrossRef]

- Sneath, P. H. A., and Sokal, R. R. (1973). Numerical Taxonomy: the principles and practice of numerical classification. San Franscisco: Freeman.

- Guarner, J. (2020). Three emerging coronaviruses in two decades: the story of SARS, MERS, and now COVID-19. American Journal of Clinical Pathology, 153(4), 420–421. [CrossRef]

- Kiemer, L., Lund, O., Brunak, S., and Blom, N. (2004). Coronavirus 3CL-pro proteinase cleavage sites: possible relevance to SARS virus pathology. BMC Bioinformatics, 5, 72. [CrossRef]

- Duckert, P., Brunak, S., & Blom, N. (2004). Prediction of proprotein convertase cleavage sites. Protein Eng Des Sel, 17(1), 107-112. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M. V., Lundegaard, C., Lamberth, K., Buus, S., Lund, O., and Nielsen, M. (2007). Large-scale validation of methods for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope prediction. BMC Bioinformatics, 8, 424. [CrossRef]

- Stranzl, T., Larsen, M. V., Lundegaard, C., and Nielsen, M. (2010). NetCTLpan: pan-specific MHC class I pathway epitope predictions. Immunogenetics, 62(6), 357–368. [CrossRef]

- Graham, R. L., and Baric, R. S. (2010). Recombination, reservoirs, and the modular spike: Mechanisms of coronavirus cross-species transmission. Journal of Virology, 84(7), 3134–3146. [CrossRef]

- Malaiyan, J., Arumugam, S., Mohan, K., & Gomathi Radhakrishnan, G. (2021). An update on the origin of SARS-CoV-2: Despite closest identity, bat (RaTG13) and pangolin derived coronaviruses varied in the critical binding site and O-linked glycan residues. J Med Virol, 93(1), 499-505. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Alanis, A., Sandner-Miranda, L., Delgado, G., Cravioto, A., & Morales-Espinosa, R. (2020). The receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is the result of an ancestral recombination between the bat-CoV RaTG13 and the pangolin-CoV MP789. BMC Res Notes, 13(1), 398. [CrossRef]

- os Santos Bezerra, R., Valença, I. N., de Cassia Ruy, P., Ximenez, J. P. B., da Silva Junior, W. A., Covas, D. T.,…Slavov, S. N. (2020). The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: From a zoonotic infection to coronavirus disease 2019. J Med Virol, 92(11), 2607-2615. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S., & Miyazawa, T. (2020). Genome evolution of SARS-CoV-2 and its virological characteristics. Inflamm Regen, 40, 17. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S., Wu, S., Zhao, G., He, Y., Guo, X., Zhang, Z.,…Wang, B. (2022). Identification of a promiscuous conserved CTL epitope within the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Emerg Microbes Infect, 11(1), 730-740. [CrossRef]

- Singh, D., & Yi, S. V. (2021). On the origin and evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Exp Mol Med, 53(4), 537-547. [CrossRef]

- Klingen, T. R., Reimering, S., Guzmán, C. A., and McHardy, A. C. (2018). In silico vaccine strain prediction for human influenza viruses. Trends in Microbiology, 26(2), 119–131. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Wu, Q., and Zhang, Z. (2020). Probable Pangolin origin of SARS-CoV-2 associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. Current Biology, 30(7), 1346–1351.e2. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y. J., Lee, K. H., Yoon, S., Nam, S. W., Ryu, S., Seong, D.,…Shin, J. I. (2021). Treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review of. Theranostics, 11(3), 1207-1231. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., Siddique, R., Shereen, M. A., Ali, A., Liu, J., Bai, Q.,…Xue, M. (2020). Emergence of a Novel Coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2: Biology and Therapeutic Options. J Clin Microbiol, 58(5). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Maurya, V. K., Prasad, A. K., Bhatt, M. L., and Saxena, S. K. (2020). Structural, glycosylation and antigenic variation between 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) and SARS coronavirus (SARS-Cov). VirusDisease, 31(1), 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Ulferts, R., Imbert, I., Canard, B., and Ziebuhr, J. (2009). Expression and functions of SARS coronavirus replicative proteins. In Lal, S. K. (Ed.), Molecular biology of the SARS-Coronavirus (pp. 75–98). New York: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Liang, C., Xin, L., Ren, X., Tian, L., Ju, X.,…Jian, Y. (2020). The development of Coronavirus 3C-Like protease (3CL. Eur J Med Chem, 206, 112711. [CrossRef]

- Sun, D., Chen, S., Cheng, A., & Wang, M. (2016). Roles of the Picornaviral 3C Proteinase in the Viral Life Cycle and Host Cells. Viruses, 8(3), 82. [CrossRef]

- Dampalla, C. S., Nguyen, H. N., Rathnayake, A. D., Kim, Y., Perera, K. D., Madden, T. K.,…Groutas, W. C. (2023). Broad-Spectrum Cyclopropane-Based Inhibitors of Coronavirus 3C-like Proteases: Biochemical, Structural, and Virological Studies. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci, 6(1), 181-194. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C., Zheng, M., Yang, Y., Gu, X., Yang, K., Li, M.,…Li, H. (2020). Furin: A Potential Therapeutic Target for COVID-19. iScience, 23(10), 101642. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., & Zhao, S. (2020). Furin cleavage sites naturally occur in coronaviruses. Stem Cell Res, 50, 102115. [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, A. G., Benton, D. J., Xu, P., Roustan, C., Martin, S. R., Rosenthal, P. B.,…Gamblin, S. J. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 and bat RaTG13 spike glycoprotein structures inform on virus evolution and furin-cleavage effects. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 27(8), 763-767. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B. A., Xie, X., Kalveram, B., Lokugamage, K. G., Muruato, A., Zou, J.,…Menachery, V. D. (2020). Furin Cleavage Site Is Key to SARS-CoV-2 Pathogenesis. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Shiryaev, S. A., Remacle, A. G., Ratnikov, B. I., Nelson, N. A., Savinov, A. Y., Wei, G.,…Strongin, A. Y. (2007). Targeting host cell furin proprotein convertases as a therapeutic strategy against bacterial toxins and viral pathogens. J Biol Chem, 282(29), 20847-20853. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).