Submitted:

10 September 2024

Posted:

11 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 82B30; 82C03; 60J20; 94A17

1. Entropy Production in Stochastic Thermodynamics

2. Rény Entropy and Information

3. On the Definition of Rény Entropy Production

4. The Case of Markovian Evolution

4.1. Rény Entropy Production for Stationary Markovian Evolution

4.2. Exchangeability of the -Limits in Rény Entropy Production

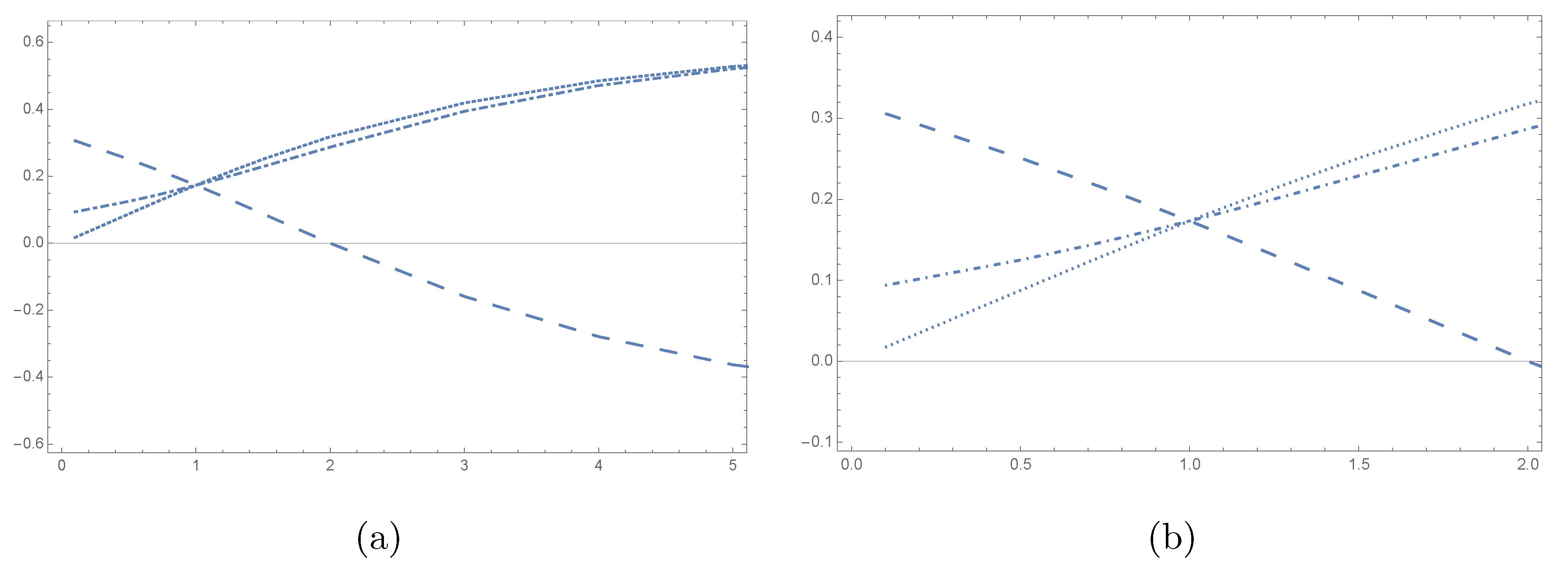

5. Numerical example

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- De Groot SR, Mazur P.Non-equilibrium thermodynamics. Dover Publications.

- Gaspard P. Time-reversed dynamical entropy and irreversibility in Markovian random processes. Journal of statistical physics. 2004 Nov;117:599-615. [CrossRef]

- Schnakenberg J. Network theory of microscopic and macroscopic behavior of master equation systems. Reviews of Modern physics. 1976 Oct 1;48(4):571. [CrossRef]

- Jiang DQ, Jiang D. Mathematical theory of nonequilibrium steady states: on the frontier of probability and dynamical systems. Springer Science & Business Media; 2004.

- Ge H, Qian H. Physical origins of entropy production, free energy dissipation, and their mathematical representations. Physical Review E—Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics. 2010 May;81(5):051133. [CrossRef]

- Esposito M, Van den Broeck C. Three faces of the second law. I. Master equation formulation. Physical Review E—Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics. 2010 Jul;82(1):011143. [CrossRef]

- Busiello, Daniel M., Deepak Gupta, and Amos Maritan. "Entropy production in systems with unidirectional transitions." Physical Review Research 2.2 (2020): 023011. [CrossRef]

- Koralov, Leonid, and Yakov G. Sinai. Theory of probability and random processes. Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- Golshani L, Pasha E, Yari G. Some properties of Rényi entropy and Rényi entropy rate. Information Sciences. 2009 Jun 27;179(14):2426-33.

- Rényi A. On measures of entropy and information. In Proceedings of the fourth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, volume 1: contributions to the theory of statistics 1961 Jan 1 (Vol. 4, pp. 547-562). University of California Press.

- Jizba P, Arimitsu T. The world according to Rényi: thermodynamics of multifractal systems. Annals of Physics. 2004 Jul 1;312(1):17-59. [CrossRef]

- Yang YJ, Qian H. Unified formalism for entropy production and fluctuation relations. Physical Review E. 2020 Feb;101(2):022129. [CrossRef]

- Rached Z, Alajaji F, Campbell LL. Rényi’s divergence and entropy rates for finite alphabet Markov sources. IEEE Transactions on Information theory. 2001 May;47(4):1553-61. [CrossRef]

- Masi M. A step beyond Tsallis and Rényi entropies. Physics Letters A. 2005 May 2;338(3-5):217-24. [CrossRef]

- Favretti M. The maximum entropy rate description of a thermodynamic system in a stationary non-equilibrium state. Entropy. 2009 Oct 29;11(4):675-87. [CrossRef]

- Monthus C. Non-equilibrium steady states: maximization of the Shannon entropy associated with the distribution of dynamical trajectories in the presence of constraints. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment. 2011 Mar 4;2011(03):P03008. [CrossRef]

- Cybulski, O., Babin, V. and Holyst, R., 2005. Minimization of the Renyi entropy production in the space-partitioning process. Physical Review E—Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics, 71(4), p.046130. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).