1. Introduction

Cancer is defined as a broad group of diseases that affect any part of the body and begin with cell death, irregular growth and subsequent invasion and spread to other organs [

1]. The number of people with cancer by 2040 is alarming [

2]. Both cellular and tumor-forming cancers have specific treatments, depending on factors such as stage, the patient's immune system, interaction with other drugs, tolerance to treatment and side effects. Among the treatments, chemotherapy is considered an effective but not selective therapy, destroying healthy cells with rapidly dividing characteristics hair follicle cells, intestinal epithelium cells and blood cells. [

3]. This fact triggers serious effects in patients receiving therapy. In this context, there are chemodrugs that act in different ways to produce cell death, inhibiting DNA synthesis, attacking growth factors, preventing angiogenesis, among others [

4].

Gemcitabine (GEM) is a nucleoside analog chemodrug composed of a nitrogenous base and a ribose with two fluorine atoms. It inhibits DNA synthesis by passing through phosphorylation states to the synthesis and blocking the sequence [

5]. It is used in monotherapy and in combination with other drugs for the treatment of several major cancers such as pancreatic [

6], non-small cell lung [

7], ovarian, breast, colon [

8] and bladder [

9]. Its biological half-life is estimated to be 17 minutes approximately, during which it can cause myelosuppression, infection, hemolytic ureic syndrome, skin rashes, alopecia, and respiratory failure, among other effects. Besides, GEM is active against clinical multiresistant strains of staphylococcus [

10]. In the biological environment it is easily converted into a secondary metabolite uracil by deoxycytidine deaminase. The raw material, gemcitabine hydrochloride, is colorless and hydrophilic [

11].

New systems have been developed to improve the administration of gemcitabine on solid tumors [

12], evaluating chemo-resistance and sensitivity factors to improve the efficacy of the therapy [

13]. Bijay Singh et al. developed a pharmacological combination of gemcitabine and imiquimod based on hyaluronic acid to stimulate immune cells in the treatment of breast cancer [

14]. Shabnam Samimi et al, prepared carbon quantum dots with quinic acid and gemcitabine and tested them in MCF7 breast cancer cells and obtained interesting results on luminescent properties and high accumulation in tumors thanks to the mixture of these materials [

15]. In contrast, Pearl Moharil et al, performed a study on polymeric nanocarriers of gemcitabine decorated with folic acid in combination with doxorubicin for dual targeting: tumor cells (breast cancer) and tumor-associated macrophages [

16]. On the other hand, Han et al. commented on the different strategies to improve the therapeutic performance of GEM through the fabrication of prodrugs and nanodrugs. Among the improved systems are liposomes, polymeric particles, inorganic metallic and non-metallic micelles and nanoparticles, among others [

17]. Another example of a novel and possibly effective system is the amphiphilic biodegradable polymeric drug carriers conjugated with gemcitabine developed by Tie-Jun Liang et al. where they obtained promising results from mPEG-PLA/GEM conjugates and showed potential for polymer-based drug targeting and accumulation in tumors, increased bioavailability and cytotoxic effect on HT29 cell line [

18].

In fact, polymeric matrices with biocompatible and biodegradable characteristics help to improve the bioavailability of these chemotherapeutic agents by avoiding damage to the biological environment (healthy cells) and drug metabolization. One of the most studied polymers due to its interesting properties of solubility in acidic aqueous media, bactericidal properties, biocompatibility, non-toxic and compatible with many other molecules and materials is Chitosan (CS) [

19,

20]. Its versatility and modifiability have led to the study of thiolated forms to improve gemcitabine loading capability and bioavailability, with enhanced results of cytotoxic effects over pure gemcitabine [

21]. It has also been shown that the modify N-Trimethyl CS form can significantly improve the oral bioavailability of gemcitabine and its efficacy against breast cancer [

22]. Similarly, the inclusion of other chemodrugs such as cisplatin or doxorubicin together with gemcitabine in a CS-polymeric matrix has also been studied [

23,

24].

Of course, the conjugation of CS with other materials has not been long in coming to obtain improved gemcitabine loading, delivery and effectiveness systems. Some of the most common components are metallic and non-metallic particles (silver NPs, iron oxide, silica, zeolites), organic molecules (folic acid, hyaluronic acid) and other biopolymers (PEG, PLGA). These materials readily couple and interact with CS to enhance the bioavailability and targeting characteristics of a delivery system for this drug [

25,

26].

One of the most studied metallic minerals in combination with CS for drug applications is iron oxide particles [

27]. These nanoparticles in addition to being compatible with chitosan are approved for use in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and have interesting magnetic properties [

28]. They increase the potential for targeted and local delivery to target cells and/or tumors in cancer therapy. Likewise, after concentrating in the target tissue, these particles can transform magnetic radiation into local heat and subsequently trigger a process of cell death by temperature increase (hyperthermia) [

29]. Several systems have been studied using functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles as vehicles for gemcitabine loading. The results show compatibility of gemcitabine with iron oxide nanoparticles and CS, increased uptake, higher accumulation and potentiation of gemcitabine cytotoxicity [

30,

31].

On the other hand, Zeolites has unique structural properties, as high porosity, ion exchange capacity, non-toxicity, biocompatibility and ability to control their physicochemical properties, have been studied as scaffolds and potential drug carriers [

32,

33]. They have antiproliferative and proapoptotic properties on cancer cells [

34]. In addition, their affinity with CS results in a synergy of controlled drug-release properties and subsequent dose adjustment [

35,

36]. Natural zeolite form as clinoptilolite is generally recognized as safe by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) being on the list of non-carcinogenic minerals and becomes a great material to include in the chemopharmaceutical delivery system [

37].

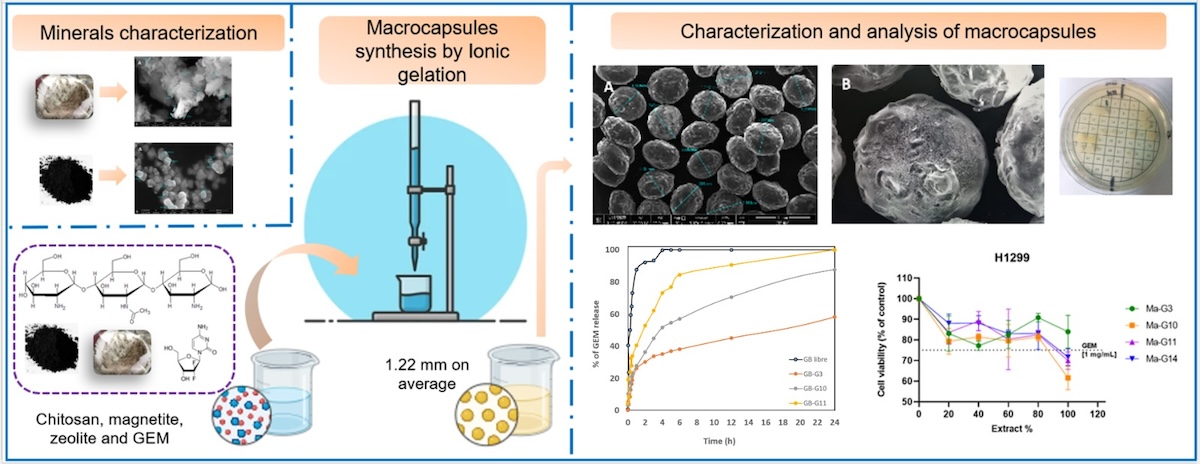

In order to fill the existing gaps in GEM delivery systems and contribute to improvements in drug bioavailability and delivery, tumor targeting, anticancer and antibacterial activity, this work focused on developing a novel system. It is the mixture of materials with specific characteristics, never before put in a composite, in the form of macrocapsules. The importance of including magnetite lies in its magnetic properties and zeolite in its harmlessness, both with possible anchor points and negative charges to generate interactions in the composite. For its part, CS was chosen for its biocompatibility, in acidic aqueous solution would facilitate the inner possible interactions.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the potential of a new delivery system for gemcitabine in the form of CS-based macrocapsules with natural zeolite and magnetite. To ensure the biomedical use of the system and to know the properties of the components, the initial materials were rigorously characterized. The physicochemical, drug-delivery, microbiological and cytotoxicity properties of the composites were evaluated.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Initial Materials Characterization

Initially, the characterization of the initial materials; chitosan, zeolite and magnetite to be included in the composite that will act as a delivery system for the chemodrug was carried out.

Table 1 shows the parameters measured in chitosan.

The biopolymer to be used in chemopharmaceutical delivery systems must have specific properties to fulfill the therapy-enhancing function. In the case of the chitosan used, with a high molecular weight of 218 kDa, it should avoid the use of any crosslinking agent such as tripolyphosphate (TPP) [

38]. The cross-linking of the chitosan chains with this and other agents modifies and slows down the biodegradation of the polymer into smaller molecular units within the biological system. On the other hand, the high degree of deacetylation allowed more protonated amino groups in the dilution in acid medium. By increasing these reactive groups, the interaction with the included materials and the retention of the GEM could be improved.

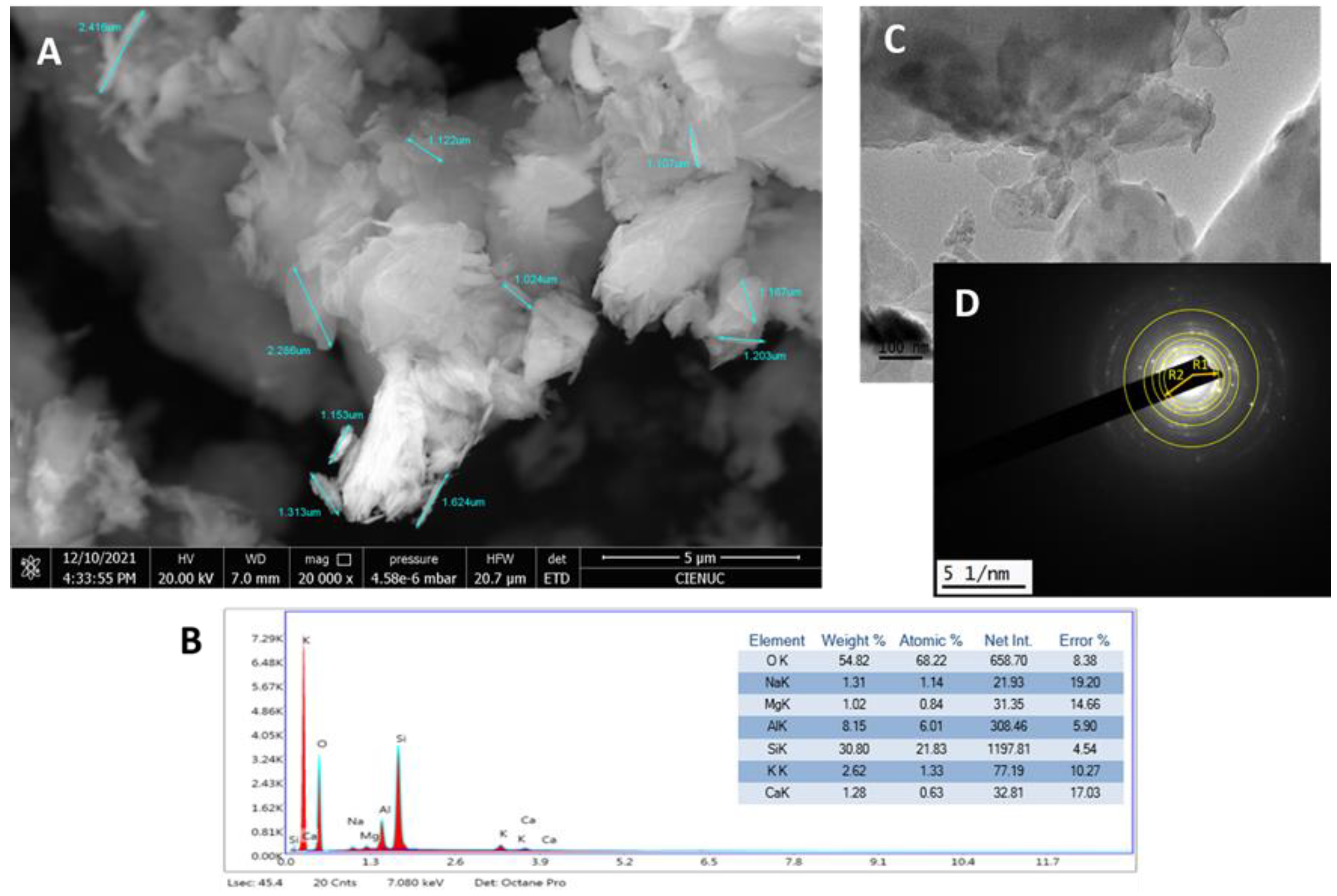

With respect to the natural zeolite (clinoptilolite), the TGA analysis showed that the percentage mass loss was 11.465% in total and occurred up to approximately 700°C. As for clinoptilolite zeolite, at higher temperatures (near 1000 °C), thermal stability without mass loss of the material is evident, due to its inorganic nature. The percentage lost is associated with evaporated water molecules, due to their hygroscopic nature. This is in agreement with those obtained by [

39,

40], who performed thermal stability analysis on a natural clinoptilolite sample. In the micrograph obtained in

Figure 1, (A) it can be observed that the zeolite sample presents ordered, agglomerated, crystalline particles (confirmed by XRD) of various shapes, including: flakes, sheets, rods and prisms [

41]. The flake shapes and tubular aggregates coincide with the micrographs reported by [

42]. An average particle size of 1.442 μm was obtained. The EDS elemental composition shown in

Figure 1 (B), yielded atoms characteristic of the tetrahedral structure of zeolite: Si, Al, and O and the cation exchange atoms: Na, Ca, Mg and K. These properties qualify the material for biomedical use [

39].

The TEM micrograph,

Figure 1 (C), shows the microstructure of the material and in the diffraction pattern

Figure 1 (D), the rings formed measured coincided with the XRD spectrum showed in

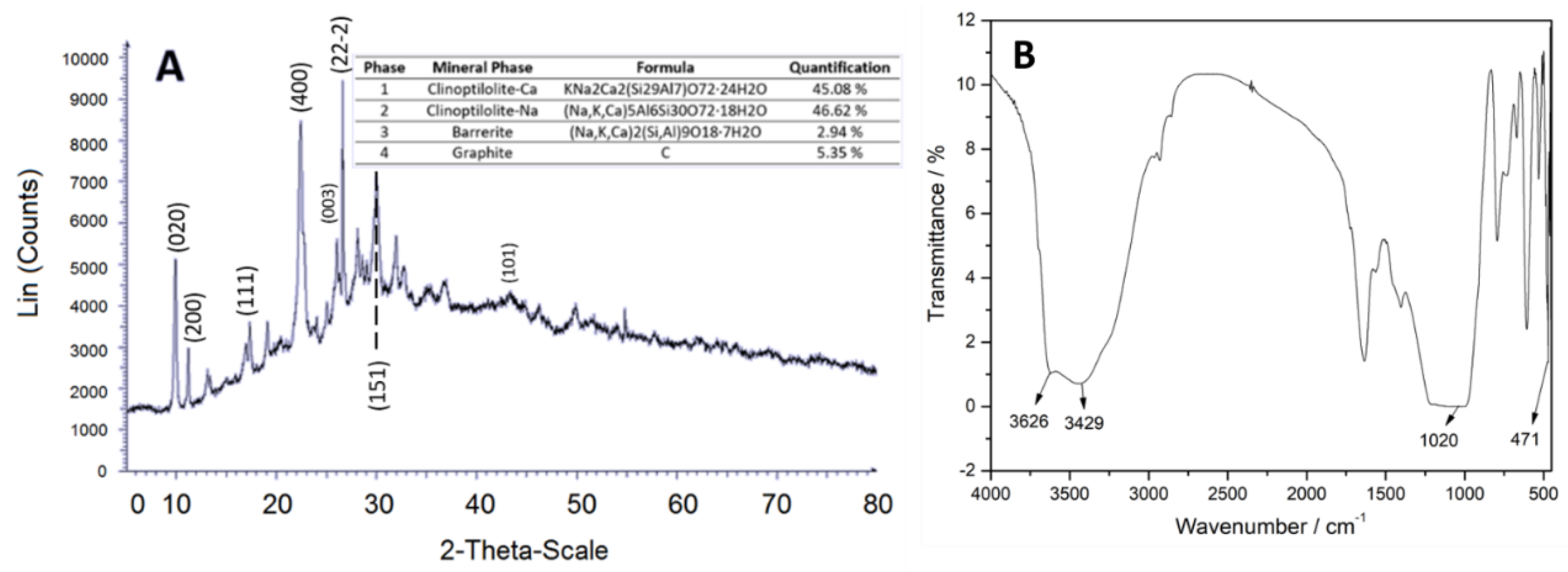

Figure 2 (A), according with x-ray tables 00-039-1383 and 00-047-1870. The intensity of planes (020) and (020), (200), (001), (021) confirm the Clinoptilolite-Ca and –Na phases.

The FT-IR spectrum,

Figure 2 (B) shows bands associated with stretching vibration of acid hydroxyls at 3626 and 3429 cm

-1, another band at 1020 cm

-1 indicating the asymmetric valence of the SiO

4 tetrahedron and a confirmation at 471 cm

-1 with bending vibration of the Si-O-Si bond.

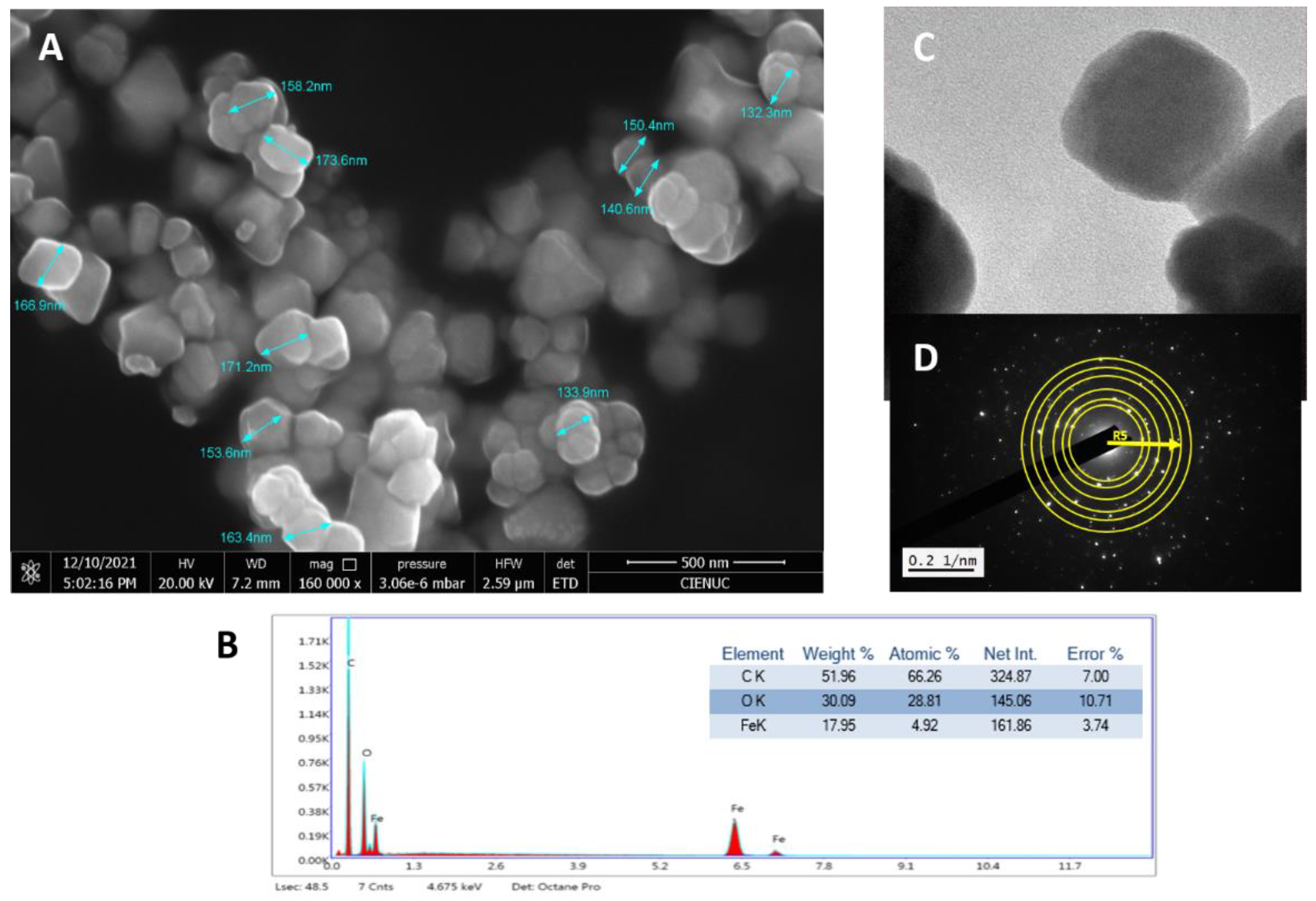

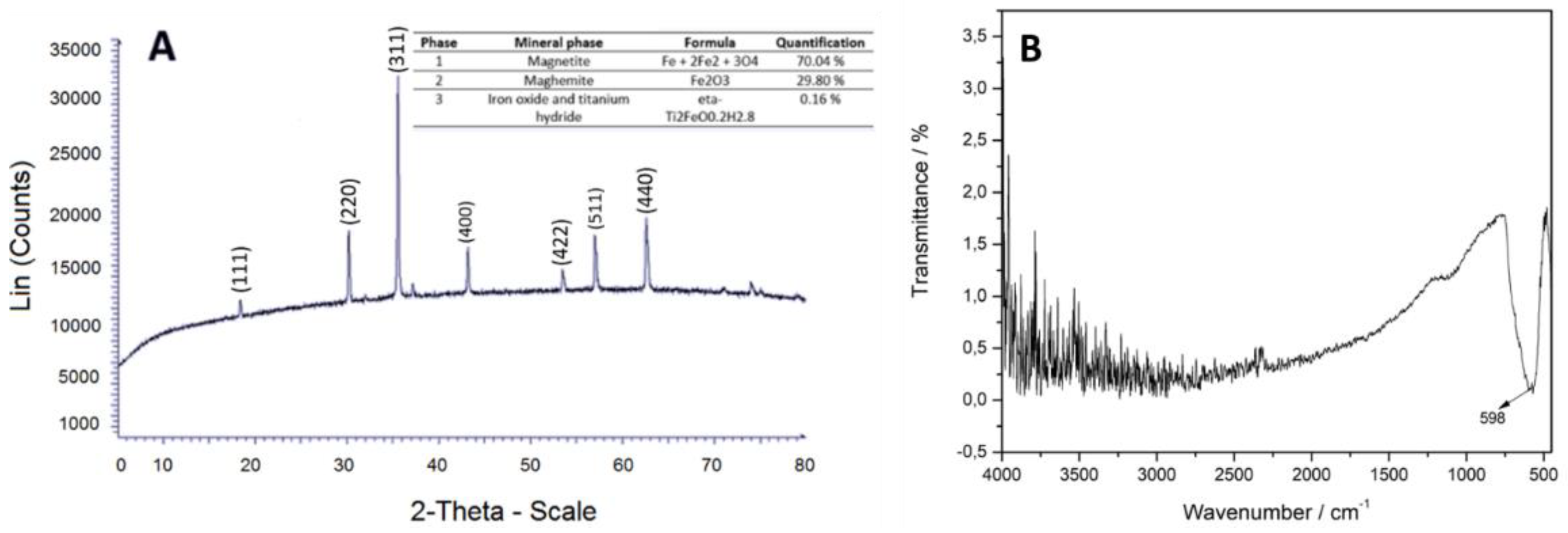

Magnetite was characterized by morphology, elemental composition, X-ray diffraction pattern and characteristic FT-IR bands.

Figure 3 (A) shows that the magnetite is in cubes, half-cubes and half-spheres with average diameter sizes of 154.4 nm and are agglomerated. In the EDS spectrum,

Figure 3 (B), carbon appeared due to the composition of the microscope sample holder. Considering the above and normalizing the composition data of magnetite in Fe and O atoms, the elemental composition results in percentages by weight in 62.64 % for O and 37.36 % for Fe.

The TEM micrograph,

Figure 3 (C and D), shows the microstructure of the material and the diffraction pattern. These data (mostly R5) coincided with the XRD spectrum

Figure 4 (A), according with x-ray tables 00-019-0629 and 00-039-1346, where the intensity of 100 of the plane (311) confirms that they correspond to the iron oxide phases, magnetite and maghemite, validating its purity [

43]. The FT-IR spectrum,

Figure 4 (B) shows band at 598 cm

-1 characteristic of the stretching vibration of the Fe-O bond [

44].

2.2. Macrocapsules Characterization

The groups of samples described below were obtained by the described method of ionic gelation to perform the respective characterization. Several techniques are used to obtain capsules for the biomedical and food industry. In this case, microencapsulation by ionic gelation proposed by Cárdenas-Triviño et al., 2021, with chitosan, magnetite and Erlotinib allowed more than 50% encapsulation of the drug, since its solubility depends on pH. In our study, gemcitabine is soluble in water (decreasing the pH), making it compatible with the CS dissolution solution. The formation of the macrocapsules then occurred by the interaction of a polysaccharide and an oppositely charged ion, precipitating the chitosan on the KOH solution. The size of the capsules will basically depend on the diameter of the nozzle or instrument used and the subsequent drying process.

The affinity of the materials for intrinsic characteristics is reflected in the results of interactions to form the composite. Just as chitosan has affinity for both the individual minerals used and the drug, [

45], also found evidence that iron ions can be inserted into clinoptilolite frameworks.

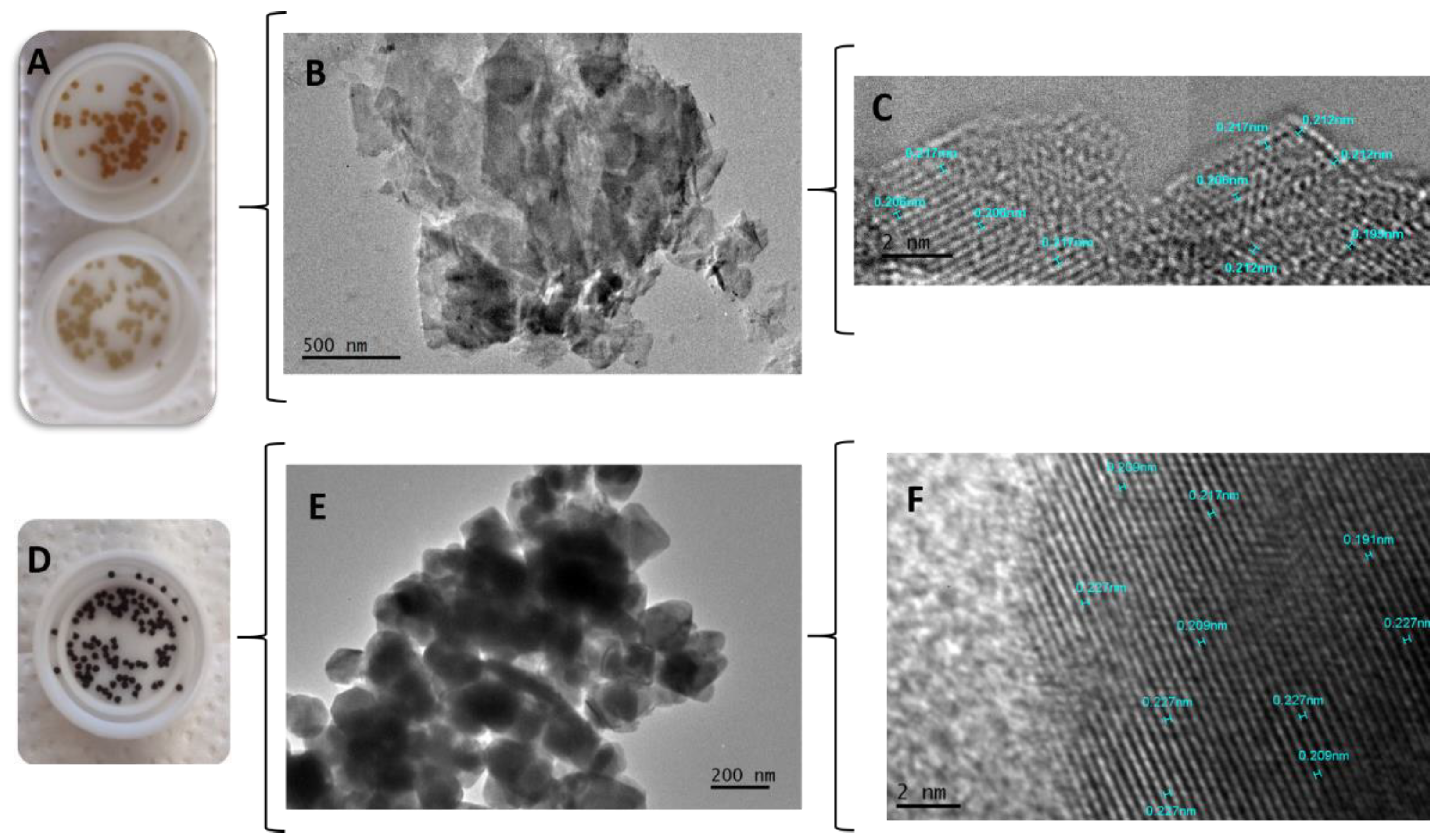

2.2.1. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM-HRTEM)

TEM and HRTEM showed that there were no modifications in the crystalline structures of the minerals inside the capsules and in their interaction with the polymeric matrix. To perform this analysis, the particle size of the macrocapsules was reduced by manual crushing with the aid of liquid nitrogen.

Figure 5 (A) corresponds to the CS macrocapsules with zeolite in different concentrations.

Figure 5 (B) show the original forms of the zeolite mineral inside the macrocapsules and the

Figure 5 (C), shows the structure, atom arrangement and interplanar distances of zeolite with an average of 0.21 nm (2.1 Å). In addition,

Figure 5 (D) shows CS macrocapsules with magnetite.

Figure 5 (E) shows the original agglomerated half-cube shape of the magnetite inside the macrocapsules. Finally,

Figure 5 (F) shows the structure with interplanar distances of magnetite (with an average of 0.217 nm).

Regarding the visualization of Clinoptilolite by TEM, there are few studies, since the electron beam that has contact with the sample damages it and therefore, it is also difficult to obtain the diffraction pattern. However, Yilmaz. S et al., managed to observe natural clinoptilolite loaded with Pd to be used as a catalyst [

46]. In the micrograph, overlapping flake-like frameworks can be observed, very similar to those obtained in this study. On the other hand [

47], is a TEM of agglomerated clinoptilolite with various shapes and sizes. Magnetite, being a crystalline metallic mineral composite material, is more stable, allowing the electron beam emitted by the microscope to pass through it, thus projecting the interference of the light in the micrograph in the form of an image.

For example, Tadic et al. [

48] synthesized and characterized iron oxide nanochairs and with TEM micrographs were able to see shapes, sizes, chain lengths and make segmentations. On the other hand, when performing an electrosynthesis and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles, were able to visualize by TEM different shapes and sizes, agglomerates of these particles [

49]. In this study it was possible to apply HRTEM to see the structure of the minerals and to know the interplanar distances. Comparing the obtained results of interplanar distances for magnetite (0.217 nm) coincide with the data reported for Velsankar V et al. who show in their HRTEM micrographs, interplanar distances of 0.22 and 0.25 nm for nanoparticles obtained from Echinochloa frumentacea [

50].

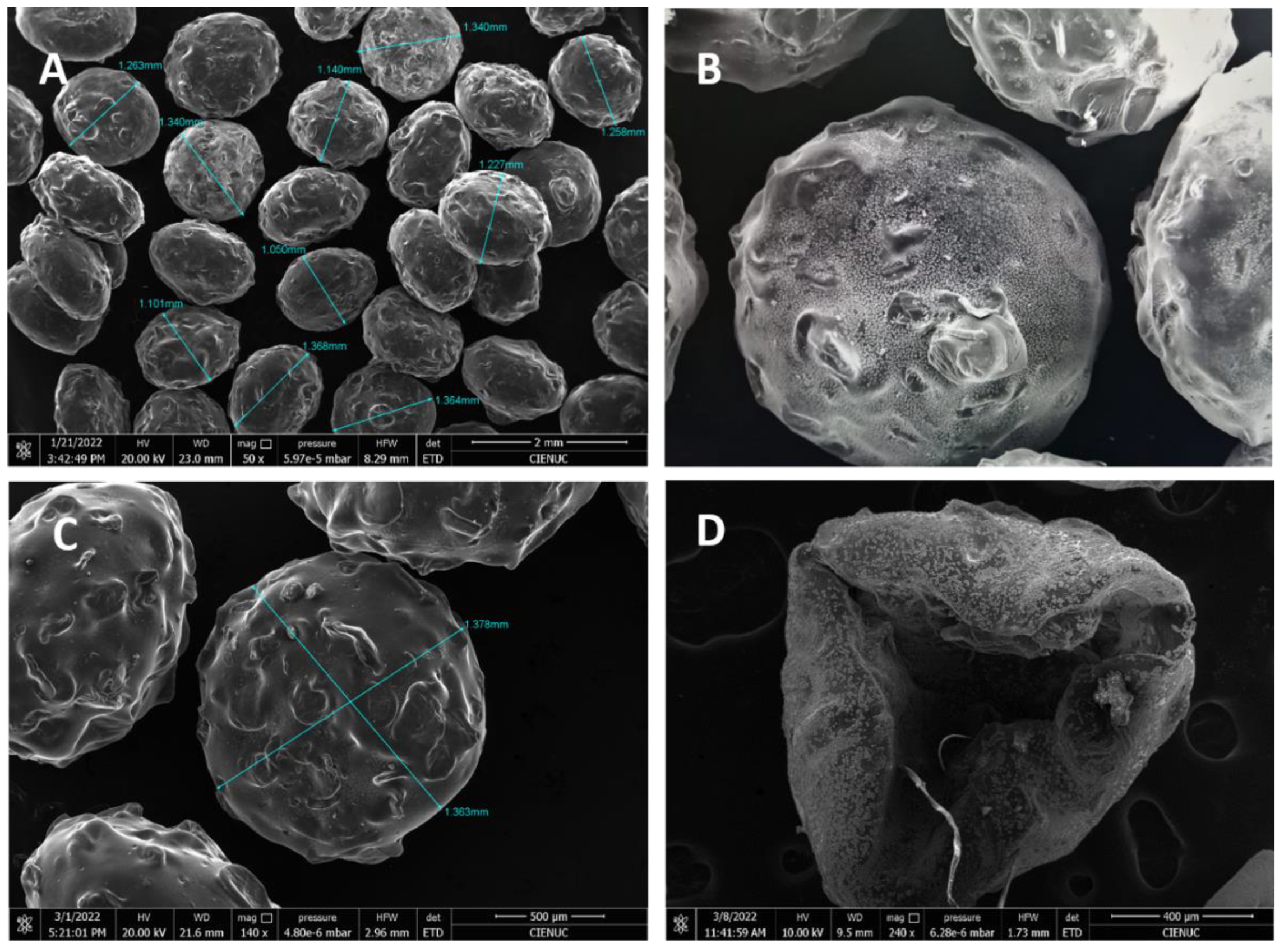

2.2.2. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (FESEM-EDS)

The macrocapsules in the form of spheres and hemispheres of about 1.22 mm in diameter were obtained. Rough surfaces and the presence of minerals on the polymeric matrix can be observed,

Figure 6. The other micrographs of the remaining macrocapsule groups are shown in

Figure S1 in the supplementary material. In addition, the capability of the instrument reveals, both on the surface and inside the capsule, the particle structures corresponding to the minerals with their characteristic shapes and the shapes of the dry biopolymer resulting from the breakage of the chitosan capsule.

EDS analysis revealed compositions corresponding to the structures of CS (C and O), magnetite (Fe and O) and zeolite (O, Si, Al, Ca, K, Na and Mg). This information is corroborated by the EDS analyses of groups 5, 7 and 14 shown in

Figure S2 in the supplementary material. Potassium was common in most of the analyses, and it is related to the KOH solution in which the capsules were precipitated. The characteristic and distinguishing fluorine atom of GEM was not detected in any system containing the drug.

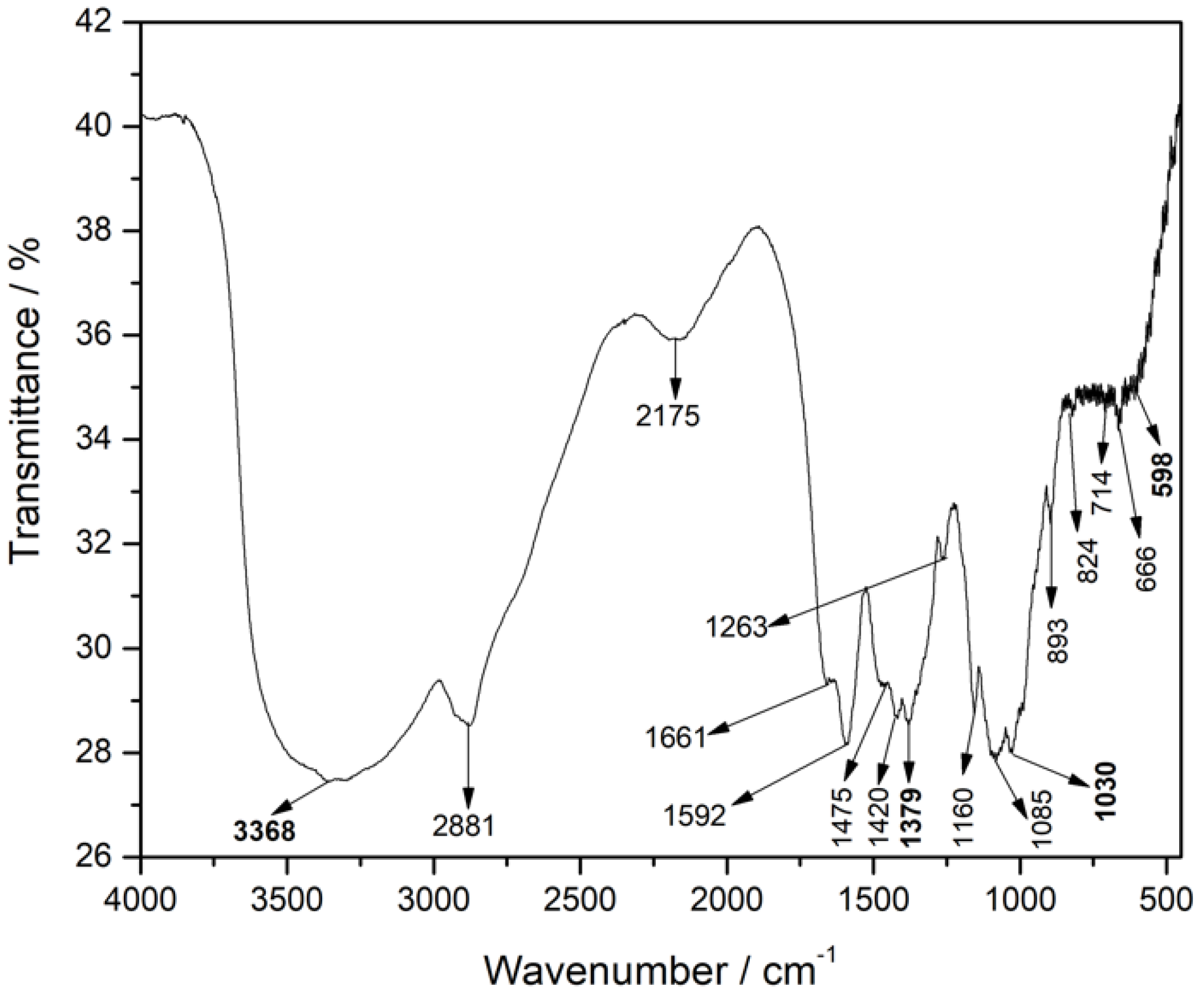

2.2.3. Infrared Spectroscopy with Fourier Transform (FT-IR)

FT-IR analyses were performed in order to prove the loading efficiency of the materials and the GEM in the chitosan macrocapsules.

Table S3 shows the bands of groups 3, 5 and 7 with specific components of CS + GEM; CS + Magnetite and CS + Zeolite, respectively.

Likewise,

Figure 7 shows the spectrum of group 14, which in its formulation contains all the materials. Here the bands at 3368 cm

-1 and 1030 cm

-1 correspond to vibrations of the zeolite OH and the asymmetric valence of the tetrahedron. The band at 598 cm

-1 shows the inclusion of magnetite with the vibration of the Fe-O bond and the band at 1379 cm

-1 indicates the loading of gemcitabine inside the capsules, with the C-F bond. The other bands correspond to the structure of the chitosan polymeric base.

The broadband peaks between 3000 and 3600 cm

-1 indicate the incorporation of GEM into the structure of the materials and into possible residues of OH ions, belonging to the KOH precipitation solution [

51]. Also, in this same section of the spectrum, the vibrations of bonds of the -OH groups of the clinoptilolite and the -NH

2 of the chitosan [

52].

2.2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

A TGA analysis was carried out to evaluate the thermal stability of the macrocapsules. The degradation peaks correspond mainly to CS and GEM (between 315°C and 284°C respectively), since, as observed above, zeolite is stable at higher temperatures. The degradation peak above 400°C is associated with the total degradation of the organic components and the loss of water from the minerals. The macrocapsule thermogram of group 14 is shown in

Figure S4 of the supplementary material.

For the TGA analysis, the data obtained by [

53] analyzed loaded with an antibiotic (oxolinic acid). Likewise, they found two maximum degradation temperatures associated with CS (285 and 590°C approximately), and the maximum mass loss percentage was 68.09 %. In our study, these two temperature peaks were 270.1 and 426.2 °C and the percentage mass loss ranged from 56.79 % to 79.18 %.

2.3. Gemcitabine Quantification, Encapsulation and Release Profiles

2.3.1. Gemcitabine Quantification by HPLC

Initially, a stock standard solution of GEM was prepared at a concentration of 500 μg/mL. Aliquots of 20, 140, 280, 400, 520, 660 and 780 μL were taken from this solution and placed in 25 mL amber volumetric flasks to obtain calibration curve concentrations: 0.4, 2.8, 5.6, 8, 10.4, 13.2 and 15.6 μg GEM/mL, respectively. Then they were injected in triplicate in the chromatograph, the GEM peaks were integrated (retention time: 6.9 approximately) and the area averages were plotted vs concentrations, obtaining the following equation of the line:

The amount of encapsulated GEM was calculated from the averages of the areas obtained in the chromatograms, in relation to the concentration obtained and the theoretical mass of the drug. Finally, this result of the trapped mass of GEM was applied in the encapsulation efficiency (%E.E.) formula (equation 2, materials and methods). The results in mg GEM and %E.E. were obtained and are arranged in

Table 2. These data show that the %E.E. for all formulations is above 82%, evidencing the affinity of both chitosan and minerals with GEM. G10 and G11 formulations displayed a similar %E.E. and slightly lower than the value shown by G3 (pure CS + GEM) suggesting that the addition of nanomagnetite does not affect the encapsulation capacity of the macrocapsules, giving it useful magnetic properties. In the same way, G14 formulation containing CS and both minerals showed a %E.E. = 86.56%, indicating that the combination of these minerals with chitosan is compatible and does not limit its drug loading properties. Likewise, the aqueous solubility of the drug allowed a good extraction with PBS buffer at pH 7.4 and the HPLC technique allowed the separation of the GEM and the CS-dissolved due to the decrease in the pH of the solution.

For the quantification of GEM, the HPLC methodology allowed the correct separation of the peaks and subsequent drug analysis, and the solubility properties of the GEM were visualized from the outset. In the acidic dispersion of the polymer matrix, the amino groups of the GEM are protonated, generating cations such as CS, which can bind to negative groups by electrostatic interaction. The percentages of GEM encapsulated in the systems above 85 % show that the technique employed, the way of drug incorporation, and the affinity of the materials favor GEM entrapment. These results are in agreement with those obtained by [

50] who tested the loading of GEM-CS nanoparticles with different amounts of cross-linking agent (Pluronic F127) and obtained GEM loading percentages above 56.22 % up to 71.07 %. On the other hand, Kazemi-Andalib et al, fabricated hollow CS and PEG microcapsules for the release of Curcumin and GEM, obtaining % E.E. results of 84% and 82%, for each drug, respectively [

54]. In addition, our results may be influenced by the different concentrations of the minerals.

2.3.2. Release Profiles

Drug release profiles were carried out to obtain information about the release kinetics of free and encapsulated GEM into macrocapsules. The amount of released GEM from the dialysis bags was followed by absorbance measurements at 269 nm by UV-Vis spectroscopy. The data obtained were normalized by the total amount of encapsulated drug and expressed as a time-dependent release percentage.

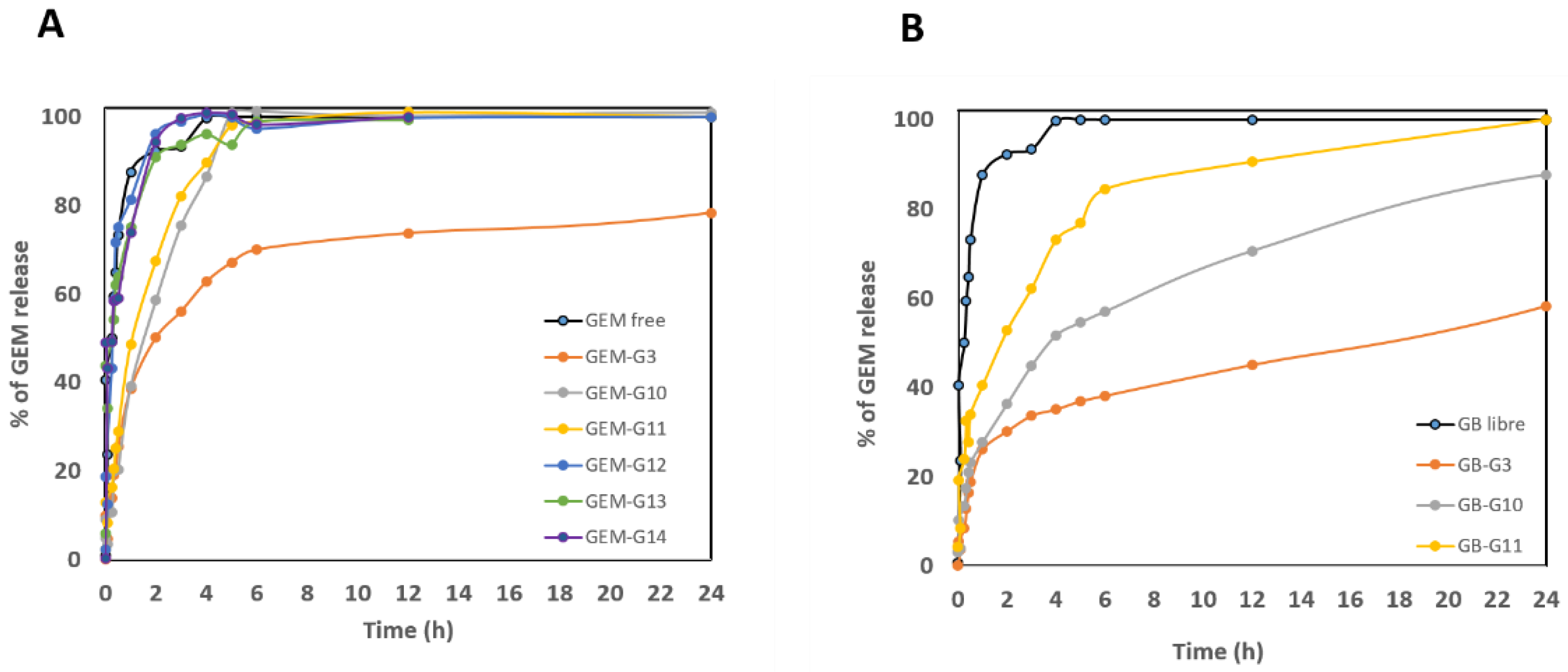

The graph of GEM delivery kinetics in PBS at pH 7.4,

Figure 8 (A), shows an explosion of release of groups 12, 13, 14 and pure GEM, when at 2 h they had already released on average more than 90%. These results suggest that the encapsulation of GEM in these macrocapsules was rather superficial, since no significant difference was observed with respect to the free drug. However, groups 3, 10 and 11 showed a slower drug release behavior, with the CS + GEM formulation (Group 3) releasing GEM the slowest in this pH condition.

To observe the behavior of the samples with some simulated physiological parameters (pH and temperature), delivery profiles were performed. Because the polymeric layer of the macrocapsules (CS) is sensitive to acidic pH, it was expected that in PBS solution at pH 7.4 it would take time to deliver to the medium [

51]. But this did not occur and means that no potential for pH-directed release is demonstrated in this case. However, for some groups (12, 13 and 14), a burst of GEM release occurred at 2 hours (i.e. ~ 90%). On the other hand, for the groups that contained only magnetite in their formulation, the behavior was more controlled release. Similar results were found by Arias. J et al. [

55], by testing magnetic CS nanoparticles loaded with GEM with two forms of drug inclusion (absorbed and entrapped). Indeed, under these neutral pH conditions, the trapped GEM had a controlled release behavior.

Now, for the release in acetate buffer pH 5.0, the groups that had better control of drug delivery at pH 7.4 were considered. The common factor of groups 10 and 11 is that both contain magnetite (in different concentrations). The kinetics graph at pH 5.0,

Figure 8 (B), shows that the formulations have a controlled drug delivery behavior with respect to pure GEM. These results can be attributed to the gelation properties of CS at acidic pH conditions, promoting a slower release of the drug loading from the macrocapsules. By 24 hours, group 3 (CS + GEM) delivered 58.29 %, group 10 (CS + Magnetite 0.0225% + GEM) delivered 87.70 % and finally group 11 (CS + Magnetite 0.1 % + GEM) released 100 % in 24 h.

Now, for the experiment at pH 5.0 solution, the first observation was that after an hour and a half, the macrocapsule content in the dialysis bag began to dissolve. Indeed, the chitosan polymer matrix allowed the release of gemcitabine and in a controlled manner in different delivery percentages for each formulation. From the behavior of groups 10 and 11, it can be inferred that the magnetite concentration influences drug release. Curiously, the formulation that only contains chitosan and gemcitabine was the one that delivered the drug the slowest, approximately 58.29% in 24 hours. Importantly, this controlled delivery of the drug at acidic pH also gives good results for targeting the tumor by other means and then reformulating the doses.

Based on these release results at both pH conditions, these same groups of macrocapsules (3, 10, 11 and 14) were chosen for cell viability assays on lung cancer cells and microbiological assays.

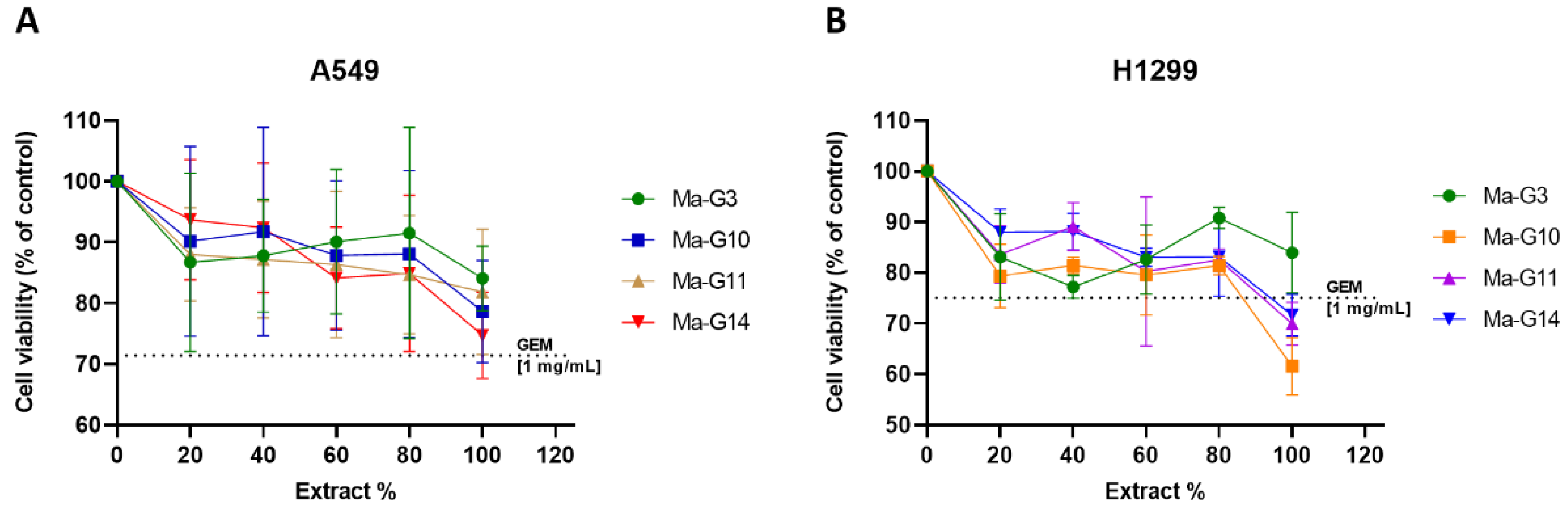

2.4. Viability Cellular Assays

The cell viability assay was determined by measuring the absorbance (UV at 570 nm) from the plates containing cells exposed to the various systems under study. The extracts at 100% from macrocapsules in groups 3, 10, 11, and 14, which encapsulate GEM at a concentration approximately 45 times lower (0.022–0.025 mg/mL) than the free GEM solution (1 mg/mL), were obtained through maceration and trituration with liquid nitrogen. For more details, review the

Table S5 of the supplementary material. Viability assays were performed in triplicate. Despite the significantly lower GEM concentration in the macrocapsule extracts, the results depicted in

Figure 9 (A) indicate that the cell viability associated with these extracts is comparable to free GEM [1mg/mL] for the A549 cell line, with the viability for GEM being 71.42%. The highest concentration of the macrocapsule extracts (100%) resulted in cell viabilities of 74.71%, 78.65%, 81.86%, and 84.12% for G14, G10, G11, and G3, respectively, suggesting a slightly lower or similar cytotoxic effect compared to free GEM, despite requiring a much lower amount of GEM to achieve this effect.

On the other hand,

Figure 9 (B) shows that macrocapsule extracts exhibit lower cell viability compared to free GEM [1mg/mL] on the H1299 cell line, where GEM-induced viability is 75.09%. Notably, despite the GEM in the macrocapsule extracts was approximately 45 times lower than in the free GEM solution, the 100% concentration of macrocapsule extracts G10, G11, and G14 resulted in viabilities of 61.59%, 69.97%, and 71.65%, respectively, indicating a greater cytotoxic effect than free GEM on the H1299 cells. Only the G3 extract at 100% concentration resulted in higher viability (83.96%) than the GEM control. As the concentration of the extracts increased, the viability of almost all groups tested decreased. Interestingly, a different behavior was observed in G3, where at low extract concentrations, viability began to decrease, then increased again at 60% and 80% extract concentration.

It is important to highlight that while the highest extract concentrations were highly effective, they achieved a cytotoxic effect on A549 cells that was comparable to free GEM, despite containing approximately 45 times less GEM. This demonstrates the efficiency of the encapsulation process, as the encapsulated GEM achieved similar cytotoxicity at a significantly lower concentration. On H1299 cells, the extracts exhibited even greater cytotoxicity than free GEM, further underscoring the advantages of the encapsulation approach. This finding aligns with previous studies suggesting that drug encapsulation within polymeric carriers can enhance cytotoxicity through sustained release and increased bioavailability, allowing for comparable or superior effects at much lower drugdoses [

56]. Notably, groups 10, 11, and 14, which include magnetite material at low and high concentrations, and a combination of magnetite and zeolite with GEM, demonstrated a more pronounced cytotoxic effect on NSCLC/H1299 cells compared to free GEM, despite the much lower GEM content in the extracts.

2.5. Microbiological Assays

With the interest of knowing the microbiological properties of the formulations against strains commonly present in hospitals, a screening was initially carried out using 10 mg of the ground samples on solid plate inoculum of E. coli, P. aerugionosa, S epidermidis and S. aureus strains (not showed results). MIC and MBC of all groups of macrocapsules were performed against S. aureus and S. epidermidis. Groups 10 to 14 showed antibacterial activity (the common component of these groups were magnetite, and GEM. As shown in

Table 3, the best activity was achieved against S. epidermidis with MICs ranging between 0.156 and 0.625 mg/mL with similar values for MCB. The exceptions were, with the MBCs approximately ten-fold higher (MIC/MBC 0.650/5.0 and 0.156/1.250, respectively). Against S. aureus, the MICs were slightly higher ranging from 0.625 to 1.250 mg/mL, except for group 12 (MIC 0.313 mg/mL). On the contrary, MBC against S. aureus was consistently higher than MIC. The group 14 was the exception, showing the same value for MIC and MBC (1.250 mg/mL).

For the S. aureus strain, the results are different, because from groups 10 to 13 the MIC’s are not the same as the MBC’s, the two highest concentrations tested (10 and 5 mg/mL) the ones with bactericidal effect. However, for group 14, which has all the components in its formulation, the MIC and MBC coincide, and the MBC value is lower than that of the previous groups. This may indicate a synergy of the combination of these materials with inhibitory and bactericidal effects against this strain.

The results obtained in this study showed that the antibacterial activity depends on the components of the formula that contains the drug. Although the synergy of microbiological properties can be inferred, it should also be considered that the ground powder of the samples could not have been homogeneous. According to Jordheim. L et al [

10], GEM had an inhibitory and bactericidal effect on various strains of multiresistant staphylococci, which vary between 0.08 and 0.25 mg/mL. On the other hand, and no less important, the antimicrobial properties of the chitosan itself should be highlighted. For example, a chitosan-based oligosaccharide derivative exhibited a MIC of 2 mg/mL against the

S. Aureus strain [

57]. Of course, the combination of chitosan in this case with the nucleoside analog enhances the bactericidal properties.

In a previous study, we worked on the synthesis and characterization of multifunctional nano-in-microencapsulated systems with the same components and materials, by spray-drying method, to evaluate the influence of size on the anticancer properties of the composites at smaller scales. The results showed promising systems with high percentages of GEM encapsulation, controlled drug release at acidic pH, percentages of magnetic mobility dependent on the concentration of magnetite, and higher cytotoxicity than pure GEM [1 mg/mL] on A549 and H1299 cells. In the treatment of lung cancer, aerial administration using an external magnetic field to improve the targeting and concentration of compounds in the tissue could provide a solution to one of the many challenges of this chemotherapy [

58].

3. Conclusions

The initial materials, chitosan, zeolite and magnetite have already been used in the biomedical area for various purposes, including as drug delivery systems. While it is true that several systems were found in the literature, this mixture of materials was the first. Their intrinsic characteristics projected a synergy, and for this reason they were chosen. Also, the use of clinoptilolite-type natural zeolite provides new and possible opportunities for the improvement of systems in drug delivery applications.

On the other hand, the ionic gelation method made it possible to form the capsules and incorporate all the materials. Thanks to the micrographs, it was possible to observe the structures of the minerals inside the capsules and to corroborate their interaction. The thermal degradation data are compatible with those reported by other authors for CS-based systems.

The characteristics of the drug (GEM) and its behavior in the acidic dispersion solution of the polymeric matrix (CS), had a significant influence on the high encapsulation percentages. Both these data and those of controlled delivery profiles at pH 5.0 (tumor microenvironment) of the formulations containing CS + nanomagnetite + GEM, demonstrated affinity and an increased potential chemopharmaceutical delivery system.

The cytotoxicity effectiveness of the highest tested concentration of the extracts of the tested groups against the immortalized lung cancer cell lines H1299 was superior to that of pure GEM [1mg/mL], even thought the GEM concentration in the macrocapsule extracts was significantly lower. For the A549 cell line, while the extracts showed slightly lower cytotoxicity compared to free GEM, this result was still notable given that the GEM concentrations in the extracts was around 45 times lower. This indicates a synergistic effect of the encapsulated materials, which enhances the cytotoxic response despite the reduced GEM content. Finally, the bactericidal properties of the tested composites enhance the antibiotic activity of GEM, presenting lower MIC and MBC values on S. epidermidis than on S. aureus.

Compared with the microencapsulated systems obtained in the previous study, the effect of the size of the capsules that include the same materials can be observed on the encapsulation efficiency and release of GEM and on the cytotoxic activity against lung cancer cells, parameters. The percentages of encapsulation efficiency were between 6-10% higher in the microcapsules. Likewise, the delivery profiles showed a less controlled release in the macrocapsules at both pH studied althougth macro and microcápsules show a more sustained release at pH 5 due to the swelling capacity of the CS matrix. "Finally, the cytotoxicity tests demonstrated that both the macrocapsules and microcapsules significantly enhanced the cytotoxic effect against the A549 and H1299 cell lines compared to pure GEM. The 100% extract of both systems showed the greatest cytotoxicity, with macrocapsules being particularly effective on H1299 cells, while microcapsules demonstrated strong cytotoxic effects on both A549 and H1299 cells."

Macrocapsule composites show significant potential as a delivery system for gemcitabine in the treatment of lung cancer, demonstrating effectiveness against both cancerous cells and bacterial infections. This dual action is particularly important in the context of immunocompromised patients, where the presence of infections can diminish the efficacy of chemotherapy. By effectively targeting cancer cells, such as those in the A549 and H1299 lines, and simultaneously combating bacterial infections, these macrocapsules could enhance the overall therapeutic outcome for patients with compromised immune systems, where infections often exacerbate the progression of cancer and undermine treatment efficacy

4. Materials and Methods

Gemcitabine hydrochloride was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (>98% HPLC Merck, Germany). High molecular weight Chitosan, food grade with a degree of deacetylation 96.64% was purchased from Quitoquímica, Chile. Zeolite (Clinoptilolite) in powder 30 mesh (Minera San Francisco, San Luis Potosí, México). Nanopowder of iron oxide (nanomagnetite) (97% Merck [Sigma Aldrich], Germany). KOH, glacial acetic acid, phosphoric acid, sodium acetate 3-hydrate and monobasic potassium phosphate were purchased from Merck.

4.1. Materials Pretreatment an Characterization of Precursor Materials

Zeolite was subjected to particle size reduction treatment using ultraturrax cycles at 10000 rpm for 8 hours, in a volume of 250 mL of water and subsequently the solid was recovered by evaporation. Characterization was made by high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), electron diffraction (ED), x-ray diffraction (XRD), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), characteristic x-ray energy division spectroscopy (EDS), Fast Fourier infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA).

For CS characterization was performed by molecular mass, degree of deacetylation, TGA and FT-IR. Meanwhile, magnetite was characterized by HRTEM-ED, XRD, FESEM-EDS, and FTIR.

4.2. Macrocapsules Synthesis by Ionic Gelation Method

The ionic gelation method is based on generating a gelation reaction between opposite charges, precipitating an acidic solution of CS on an alkaline solution of 0.5 M KOH, drop by drop. The contact of the polycation with the hydroxyl groups (anion) gives rise to the polyelectrolyte reaction, where the outer layer of the CS precipitates. Then, a 4% CS dispersion was prepared in a 1% acetic acid solution and then mixed with the amounts described in

Table 5. At the same time, a 0.5 mol L

-1 KOH solution was prepared. The order of addition in the systems containing all the components was: GEM, nanomagnetite and zeolite. The mixtures remained in magnetic mechanical agitation for 8 h at 600 rpm and then were precipitated over the KOH solution. They were recovered by filtration, washed with distilled water and checked for neutral pH. They were dried in convection oven between 50 ± 2 °C for 5 hours [

59].

The macrocapsules to be obtained would have a ratio of 2.5 % and 0.56 % of high and low concentrations respectively of nanomagnetite and microzeolite to CS. In the case of GEM, this would be 0.0625 % with respect to CS.

4.3. Macrocapsules Characterization

4.3.1. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM-HRTEM)

A JEOL 2010F microscope with resolution of 0.19 nm was used. The HRTEM micrographs provided information on the crystalline structure of the materials.

4.3.2. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (FESEM-EDS)

The FEI QUANTA FEG 250FESEM microscope with EDS equipment was used for obtaining morphologic particle size and chemical composition information of the materials.

4.3.3. Infrared Spectroscopy with Fourier Transform (FT-IR)

A Perkin Elmer infrared spectrophotometer model Spectrum Two was used to study the incorporation of the components and the drug inside the macrocapsules. The spectra obtained from the samples were analyzed with the OriginPro 9.0 program.

4.3.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

For the thermogravimetric analysis, a TA Instrument model -Q50 was used to determine the thermal stability of the samples. The initial weight of the samples varied from 1 to 6 mg which was maintained at a heating rate of 10 °C/min and N2 (g) atmosphere flow rate up to 550°C

4.4. Gemcitabine Quantification, Encapsulation and Delivery Profiles

For the initial titration from the macrocapsules, the HPLC method (at 275 nm) was used because in the process of maceration, solubilization and extraction of the drug molecule, the chitosan also showed UV absorbance at the same wavelength. Thus, chromatography was used to separate the peaks and quantify gemcitabine more accurately. On the other hand, the quantification of gemcitabine for delivery profile assays was carried out by spectrophotometry UV-Vis employing a wavelength of 269 nm.

4.4.1. Encapsulation Efficiency (E.E.%)

The HPLC technique (Agilent, 1220 Infinity LC) was used to quantify gemcitabine. The general conditions of the equipment were: mobile phase, KH

2PO

4 buffer (13.8 g) and H

3PO

4 (2.5 mL) pH 2.4, for one liter. Column, Zorbax - C18; 4.6x150 mm; 5-Micron. Flow rate 1.4 - 1.9 mL/min; wavelength: 275 nm. To find the encapsulation efficiency, 20 mg of each sample was weighed in triplicate, 1 mL of PBS buffer at pH of 7.40 was added then vortexed for 10 min and the supernatant was filtered (0.22 μm) to inject 20 μL into the chromatograph. Encapsulation efficiency (E.E.%) was calculated form equation 2 [

58,

60]:

4.4.2. Release Profiles

Drug release studies from macrocapsules were performed using the equilibrium dialysis method [

61]. For GEM release profiles, two different buffer solutions were prepared: PBS at pH 7.4 and acetate buffer at pH 5.0, to simulate physiological and tumor microenvironment conditions, respectively. Briefly, 2.0 grams of macrocapsules were put into a dialysis membrane sac (cut-off 12.5 kDa, Merck), with 3 mL of buffer previously prepared. The enclosed membranes were immersed in a beaker containing 100 mL of the delivery medium at 37.0 °C in continuous agitation at 100 rpm. Subsequently, 700 μL aliquots were taken every 5 minutes until 30 minutes, then at 60 minutes and thereafter every hour until 6 hours. Finally, two more aliquots were taken at 12 and 24 hours. The volume of buffer was replenished at each sampling. These aliquots were read in an Evolution 206 Bio UV-Vis spectrophotometer at 269 nm [

62].

4.5. Viability Cellular Assays

Cell viability assays were performed by MTT method on immortalized A549 and H1299 lung cancer cell lines (5000 cells per well - 96-well plate). Macrocapsule samples of groups 3, 10, 11 and 14 were macerated with the aid of liquid nitrogen and subsequently, 50 mg of the samples were subjected to extraction in RPMI medium (1300 μL) with the aid of 0.4 μm inserts in 24-well plates. After 24 hours, the seeded cells were contacted with sample extracts at concentrations of 100, 80, 60, 40 and 20%. For the above, 100 μL of the extract was placed directly in the 100 % concentration and for the others, in the first one, 800 μL of the extract was taken and mixed with 200 μL of the medium after shaking with the micropipette about 10 times, an aliquot of 600 μL was taken and mixed with 200 μL of the medium. After shaking, 400 μL of aliquot was taken and mixed with 200 μL. Finally, after shaking, 200 μL aliquot was taken and mixed of the medium and pipetted for 10 times to homogenize. The estimated GEM concentrations (mg/mL) for the different extracts are given in

Table S5 of the supplementary material.

Twenty-four hours later, the MTT reagent was added to react and stain the live cells; the plates were placed in the incubator for 4 hours at 37 °C. After this time, MTT solubilizer was added and after 24 hours, the absorbance was read in the equipment UV TECAN Infinite M Nano at 570 nm.

4.6. Microbiological Assays

The antibacterial activity of the different compounds was assayed against

S. aureus ATCC25923 and

S. epidermidis ATCC12228. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) was determined by the broth microdilution method according to EUCAST protocol [

63] with minimal variations. Briefly, solutions of 10 mg/mL of each compound were prepared directly in Mueller Hinton broth. A series of two-fold dilutions between 10 and 0.01 mg/mL was prepared in 96-well, U-shaped-bottom microplates and inoculated with the testing strains at a final concentration of 5x105 UFC/mL. Plates were incubated at 35 °C for 24 hours. MIC was registered as the lowest concentration of the compound that completely inhibits growth. All assays were performed in triplicated.

Minimal Bactericidal Concentrations (MBC) were determined by inoculating 10 μL from each well without visual turbidity onto Mueller Hinton agar plate. The lowest dilution showing no growth was considered as MBC after 24 h of incubation at 35 °C.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: FESEM micrographs of macrocapsules; (A) group 3, (B) group 4, (C) group 5, (D) group 6, (E) group 8, (F) group 9, (G) group 10, (H) group 11, (I) group 12, (K) group 14 and (K) minerals in the surface focus of group 14. Figure S2: EDS analysis of the group 5 (A), group 7 (B) and group 14 (C). Figure S3: Thermogram, macrocapsules group 14.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Investigation, methodology, visualization and writing-original draft was performed by Yuly Andrea Guarín-González. Conceptualization, resources, supervision and visualization was performed by Gerardo Cabello-Guzmán. Resources, software and writing-review & editing was performed by José Reyes-Gasga. Data curation by Yanko Moreno-Navarro. Methodology, resources and writing-review & editing was performed by Luis Vergara-González. Software by Antonia Martin-Martín. Formal analysis, methodology and resources was performed by Rodrigo López-Muñoz. Conceptualization, methodology, project administration and validation was performed by Galo Cárdenas-Triviño. Formal analysis, methodology, resources and writing-review & editing was performed by Luis Felipe Barraza. Finally, all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ANID FONDECYT, grant number 11200611.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

To the DIMPROS program of the Universidad del Bío-Bío and the research grant awarded by the vice-chancellor's office of the same university. To Dr. José Reyes Gasga for his help and contribution in the characterization of the minerals by means of HRTEM images. To Dr. Galo Cárdenas Triviño (R.I.P.), for his valuable contribution of knowledge on biomaterials, composites and the feasibility of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pecorino, L. Molecular Biology of Cancer Topics. Oxford, United Kingdom; 2016. 397 p. Available from: http://www.angelfire.com/sc3/toxchick/molbiocancer/molbiocancer11.html.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer Tomorrow. Global Cancer Observatory. 2018 [cited 2019 Oct 10]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/graphic-isotype?

- DeRidder L, Rubinson DA, Langer R, Traverso G. The past, present, and future of chemotherapy with a focus on individualization of drug dosing. J Control Release. 2022;352(November):840–60. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Shiranthika C, Wang C, Chen K, Sumathipala S. Reinforcement Learning Strategies in Cancer Chemotherapy Treatment: A Review. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2022;107280. [CrossRef]

- Armijo JA, Mediavilla Á. Farmacología Humana Florez. Vol. 3ra Edició, Masson, S.A. Editorial Garsi, S.A. 1998. 1–1302 p.

- Thierry André, Monique Noirclerc, Pascal Hammel, Roderich Meckenstock, Bruno Landi, Stéphane Cattan, Frédéric Selle, Jena- francois Codoul, Béatrice Guerrier-Parmentier, Rabia Mokhtar, Christophe Luvet G. Phase II study of leucovorin, 5-fluorouracil metastatic pancreatic cancer ( FOLFUGEM 2 ). Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28:645–50.

- Forster M, Hackshaw A, De Pas T, Cobo M, Garrido P, Summers Y, et al. A phase I study of nintedanib combined with cisplatin/gemcitabine as first-line therapy for advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer (LUME-Lung 3). Lung Cancer. 2018;120(August 2017):27–33. [CrossRef]

- Bobek V, Pinterova D, Kolostova K, Boubelik M, Douglas J, Teyssler P, et al. Streptokinase increases the sensitivity of colon cancer cells to chemotherapy by gemcitabine and cis-platine in vitro. Cancer Lett. 2006;237(1):95–101.

- Aydin AM, Cheriyan SK, Reich R, Hajiran A, Peyton CC, Zemp L, et al. Comparative analysis of three vs. four cycles of neoadjuvant gemcitabine and cisplatin for muscle invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig. 2022;40(10):453.e19-453.e26. [CrossRef]

- Jordheim LP, Ben Larbi S, Fendrich O, Ducrot C, Bergeron E, Dumontet C, et al. Gemcitabine is active against clinical multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus strains and is synergistic with gentamicin. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39(5):444–7. [CrossRef]

- Jyoti Dahiya*, Pawan Jalwal, Sneh Lata PM. Development and evaluation oh Eethanol free ready to use injection og gemcitabine hydrochloride. Int J pharma Prof Res. 2015;6(2):1218–22.

- Paroha S, Verma J, Dubey RD, Dewangan RP, Molugulu N, Bapat RA, et al. Recent advances and prospects in gemcitabine drug delivery systems. Int J Pharm. 2021;592(November 2020):120043. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Wu P, Guo C, Zhang C, Zhao Y, Tan D, et al. Lipocalin 2 may be a key factor regulating the chemosensitivity of pancreatic cancer to gemcitabine. Biochem Biophys Reports. 2022;31(April):101291. [CrossRef]

- Singh B, Maharjan S, Pan DC, Zhao Z, Gao Y, Zhang YS, et al. Imiquimod-gemcitabine nanoparticles harness immune cells to suppress breast cancer. Biomaterials. 2022;280(April 2021):121302. [CrossRef]

- Samimi S, Ardestani MS, Dorkoosh FA. Preparation of carbon quantum dots- quinic acid for drug delivery of gemcitabine to breast cancer cells. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2021;61(August 2020):102287. [CrossRef]

- Moharil P, Wan Z, Pardeshi A, Li J, Huang H, Luo Z, et al. Engineering a folic acid-decorated ultrasmall gemcitabine nanocarrier for breast cancer therapy: Dual targeting of tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(3):1148–62. [CrossRef]

- Han H, Li S, Zhong Y, Huang Y, Wang K, Jin Q, et al. Emerging pro-drug and nano-drug strategies for gemcitabine-based cancer therapy. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2022;17(1):35–52.

- Liang TJ, Zhou ZM, Cao YQ, Ma MZ, Wang XJ, Jing K. Gemcitabine-based polymer-drug conjugate for enhanced anticancer effect in colon cancer. Int J Pharm. 2016;513(1–2):564–71.

- Guarín González YA, Cárdenas Triviño G. New Chitosan-Based Chemo Pharmaceutical Delivery Systems for Tumor Cancer Treatment: Short-Review. J Chil Chem Soc. 2022;67(1):5425–32.

- Dubey SK, Bhatt T, Agrawal M, Saha RN, Saraf S, Saraf S, et al. Application of chitosan modified nanocarriers in breast cancer. Int J Biol Macromol [Internet]. 2022;194(November 2021):521–38. [CrossRef]

- Kaur A, Kumar P, Kaur L, Sharma R, Kush P. Thiolated chitosan nanoparticles for augmented oral bioavailability of gemcitabine: Preparation, optimization, in vitro and in vivo study. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2021;61(July 2020):102169. [CrossRef]

- Chen G, Svirskis D, Lu W, Ying M, Li H, Liu M, et al. N-trimethyl chitosan coated nano-complexes enhance the oral bioavailability and chemotherapeutic effects of gemcitabine. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;273(June 2020):118592. [CrossRef]

- Yu H, Song H, Xiao J, Chen H, Jin X, Lin X, et al. The effects of novel chitosan-targeted gemcitabine nanomedicine mediating cisplatin on epithelial mesenchymal transition, invasion and metastasis of pancreatic cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;96(305):650–8.

- Huang TH, Hsu S hui, Chang SW. Molecular interaction mechanisms of glycol chitosan self-healing hydrogel as a drug delivery system for gemcitabine and doxorubicin. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:700–9. [CrossRef]

- Karuppaiah A, Babu D, Selvaraj D, Natrajan T, Rajan R, Gautam M, et al. Building and behavior of a pH-stimuli responsive chitosan nanoparticles loaded with folic acid conjugated gemcitabine silver colloids in MDA-MB-453 metastatic breast cancer cell line and pharmacokinetics in rats. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2021;165(June):105938. [CrossRef]

- Garg NK, Dwivedi P, Campbell C, Tyagi RK. Site specific/targeted delivery of gemcitabine through anisamide anchored chitosan/poly ethylene glycol nanoparticles: An improved understanding of lung cancer therapeutic intervention. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2012;47(5):1006–14. [CrossRef]

- Unsoy G, Khodadust R, Yalcin S, Mutlu P, Gunduz U. Synthesis of Doxorubicin loaded magnetic chitosan nanoparticles for pH responsive targeted drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2014;62:243–50. [CrossRef]

- Ullah Khan A, Chen L, Ge G. Recent development for biomedical applications of magnetic nanoparticles. Inorg Chem Commun. 2021;134(October):108995. [CrossRef]

- Trujillo Herrera, W.V. Preparación y caracterización de nanopartículas de magnetita funcionalizados con ácido láurico, oleico y etilendiamino tetraacético para aplicaciones biomédicas y remediación ambiental. Univ Nac Mayor San Marcos - Lima, Perú. 2013.

- Viota JL, Carazo A, Munoz-Gamez JA, Rudzka K, Gómez-Sotomayor R, Ruiz-Extremera A, et al. Functionalized magnetic nanoparticles as vehicles for the delivery of the antitumor drug gemcitabine to tumor cells. Physicochemical in vitro evaluation. Mater Sci Eng C. 2013;33(3):1183–92. [CrossRef]

- Khan S, Setua S, Kumari S, Dan N, Massey A, Hafeez B Bin, et al. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles of curcumin enhance gemcitabine therapeutic response in pancreatic cancer. Biomaterials. 2019;208(April):83–97. [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski M, Kucinska M, Ratajczak M, Pokora M, Murias M, Voelkel A, et al. Zinc forms of faujasite zeolites as a drug delivery system for 6-mercaptopurine. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022;343(March):112194. [CrossRef]

- Souza IMS, Borrego-Sánchez A, Rigoti E, Sainz-Díaz CI, Viseras C, Pergher SBC. Experimental and molecular modelling study of beta zeolite as drug delivery system. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021;321(April):1–10.

- Servatan M, Zarrintaj P, Mahmodi G, Kim SJ, Ganjali MR, Saeb MR, et al. Zeolites in drug delivery: Progress, challenges and opportunities. Drug Discov Today. 2020;25(4):642–56. [CrossRef]

- Sandomierski M, Adamska K, Ratajczak M, Voelkel A. Chitosan - zeolite scaffold as a potential biomaterial in the controlled release of drugs for osteoporosis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;223(PA):812–20. [CrossRef]

- Faraji Dizaji B, Hasani Azerbaijan M, Sheisi N, Goleij P, Mirmajidi T, Chogan F, et al. Synthesis of PLGA/chitosan/zeolites and PLGA/chitosan/metal organic frameworks nanofibers for targeted delivery of Paclitaxel toward prostate cancer cells death. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;164:1461–74.

- Serati-Nouri H, Jafari A, Roshangar L, Dadashpour M, Pilehvar-Soltanahmadi Y, Zarghami N. Biomedical applications of zeolite-based materials: A review. Mater Sci Eng C. 2020;116(February):111225. [CrossRef]

- Nawrotek K, Tylman M, Adamus-Włodarczyk A, Rudnicka K, Gatkowska J, Wieczorek M, et al. Influence of chitosan average molecular weight on degradation and stability of electrodeposited conduits. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;244(May):116484.

- Korkuna O, Leboda R, Skubiszewska-Ziȩba J, Vrublevs’ka T, Gun’ko VM, Ryczkowski J. Structural and physicochemical properties of natural zeolites: Clinoptilolite and mordenite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006;87(3):243–54.

- Cerri G, Farina M, Brundu A, Daković A, Giunchedi P, Gavini E, et al. Natural zeolites for pharmaceutical formulations: Preparation and evaluation of a clinoptilolite-based material. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016;223:58–67.

- Favvas EP, Tsanaktsidis CG, Sapalidis AA, Tzilantonis GT, Papageorgiou SK, Mitropoulos AC. Clinoptilolite, a natural zeolite material: Structural characterization and performance evaluation on its dehydration properties of hydrocarbon-based fuels. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016;225:385–91. [CrossRef]

- Güngör D, Özen S. Development and characterization of clinoptilolite-, mordenite-, and analcime-based geopolymers: A comparative study. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2021;15(May).

- Manjunatha M, Kumar R, Anupama A V., Khopkar VB, Damle R, Ramesh KP, et al. XRD, internal field-NMR and Mössbauer spectroscopy study of composition, structure and magnetic properties of iron oxide phases in iron ores. J Mater Res Technol. 2019;8(2):2192–200. [CrossRef]

- Chandra Mohanta S, Saha A, Sujatha Devi P. PEGylated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for pH Responsive Drug Delivery Application. Mater Today Proc. 2018;5(3):9715–25. [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Rivas F, Rodríguez-Fuentes G, Berlier G, Rodríguez-Iznaga I, Petranovskii V, Zamorano-Ulloa R, et al. Evidence for controlled insertion of Fe ions in the framework of clinoptilolite natural zeolites. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013;167:76–81.

- Yilmaz S, Ucar S, Artok L, Gulec H. The kinetics of citral hydrogenation over Pd supported on clinoptilolite rich natural zeolite. Appl Catal A Gen. 2005;287(2):261–6.

- Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh A, Khorsandi S. Photocatalytic degradation of 4-nitrophenol with ZnO supported nano-clinoptilolite zeolite. J Ind Eng Chem. 2014;20(3):937–46. [CrossRef]

- Tadic M, Kralj S, Kopanja L. Synthesis, particle shape characterization, magnetic properties and surface modification of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanochains. Mater Charact. 2019;148(December 2018):123–33. [CrossRef]

- Yousefi T, Davarkhah R, Nozad Golikand A, Hossein Mashhadizadeh M, Abhari A. Facile cathodic electrosynthesis and characterization of iron oxide nano-particles. Prog Nat Sci Mater Int. 2013;23(1):51–4. [CrossRef]

- Velsankar V, Parvathy G, Mohandoss S, Ravi G, Sudhahar S. Echinochloa frumentacea grains extract mediated synthesis and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles: A greener nano drug for potential biomedical applications. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022;76(September):103799. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh H, Atyabi F, Dinarvand R, Ostad SN. Chitosan-Pluronic nanoparticles as oral delivery of anticancer gemcitabine: Preparation and in vitro study. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:1851–63.

- Yazdi F, Anbia M, Salehi S. Characterization of functionalized chitosan-clinoptilolite nanocomposites for nitrate removal from aqueous media. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;130:545–55. [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Triviño G, Burgos M, Plessing CVON. Microencapsulation of oxolinic acid with chitosan beads. J Chil Chem Soc. 2018;63(4):4229–38.

- Kazemi-Andalib F, Mohammadikish M, Divsalar A, Sahebi U. Hollow microcapsule with pH-sensitive chitosan/polymer shell for in vitro delivery of curcumin and gemcitabine. Eur Polym J. 2022;162(November 2021):110887. [CrossRef]

- Arias JL, Reddy LH, Couvreur P. Fe 3O 4/chitosan nanocomposite for magnetic drug targeting to cancer. J Mater Chem. 2012;22(15):7622–32.

- Paroha S, Verma J, Singh Chandel AK, Kumari S, Rani L, Dubey RD, et al. Augmented therapeutic efficacy of Gemcitabine conjugated self-assembled nanoparticles for cancer chemotherapy. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol [Internet]. 2022;76(July):103796. [CrossRef]

- Xia W, Wei XY, Xie YY, Zhou T. A novel chitosan oligosaccharide derivative: Synthesis, antioxidant and antibacterial properties. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;291:119608. [CrossRef]

- Guarín-González YA, Cabello-Guzmán G, Plessing C Von, Segura R, Barraza LF, Martin-Martín A, et al. Multifunctional nano-in-microparticles for targeted lung cancer cells: Synthesis, characterization and efficacy assessment. Mater Today Chem. 2024;38(December 2023).

- Cárdenas-Triviño G, Monsalve-Rozas S, Vergara-González L. Microencapsulation of Erlotinib and Nanomagnetite Supported in Chitosan as Potential Oncologic Carrier. Polymers (Basel). 2021;13(1244):22. [CrossRef]

- Demirbuken SE, Karaca GY, Kaya HK, Oksuz L, Garipcan B, Oksuz AU, et al. Paclitaxel-conjugated phenylboronic acid-enriched catalytic robots as smart drug delivery systems. Mater Today Chem. 2022;26.

- Bhadra D, Bhadra S, Jain S, Jain NK. A PEGylated dendritic nanoparticulate carrier of fluorouracil. Int J Pharm. 2003;257(1–2):111–24.

- Barraza LF, Jiménez VA, Alderete JB. Methotrexate Complexation with Native and PEGylated PAMAM-G4: Effect of the PEGylation Degree on the Drug Loading Capacity and Release Kinetics. Vol. 217, Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 2016. p. 605–13.

- European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Broth Dilution 2003. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(8):1–7.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).