1. Introduction

The toxic plants containing swainsonine (SW) from the genera

Oxytropis and

Astragalus are referred to as locoweed, internationally [

1,

2]. Locoweeds are mainly distributed in Asia, North America, and Australia [

3,

4,

5]. Continuous consumption of locoweeds by livestock results in locoism, with symptoms including neurological dysfunction, infertility, abortion, and even death in severe cases [

6,

7,

8]. Significant economic losses to the grassland livestock industry are caused by locoweeds spreading [

3]. The toxic component causing locoism is swainsonine (SW), an indolizidine alkaloid whose chemical structure is similar to mannose [

4]. SW inhibits the activities of lysosomal α-mannosidase I and Golgi mannosidase II, leading to disruptions in protein synthesis and processing, which in turn causes cellular vacuolation [

3,

4,

9]. SW in locoweeds is produced by endophytic fungi isolated and identified in various locoweeds species, belonging to

Alternaria oxytropis [

2,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

We previously knocked out the saccharopine reductases gene (

sac) in

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 isolated from

Oxytropis glabra. Compared to OW 7.8, the knockout mutant M1 exhibited decreased levels of SW and saccharopine, while the level of

L-lysine did not change significantly [

18]. The SW level is higher in the

sac gene complementation strain C1 than in OW 7.8 and M1, suggesting that the function of

sac gene promotes SW synthesis in fungi. A comparative genomic analysis was conducted on

Metarhizium robertsii,

Ipomoea carnea endophyte,

Arthroderma otea,

Trichophyton equinum,

A. oxytropis, and

Pseudogymnoascus sp., suggesting the presence of a "SWN gene clusters" closely related to SW synthesis in these fungi [

19]. The SWN gene clusters consist of

swnA,

swnH1,

swnH2,

swnK,

swnN,

swnR, and

swnT (

Table 1). However, 5 SWN genes including

swnR,

swnK,

swnN,

swnH1, and

swnH2 exist in

A. oxytropis genome, while swnA gene and

swnT gene are absent [

19,

20].

The

swnK gene encodes a multifunctional protein that contains 7 functional domains: A, T, KS, AT, KR, ACP, and R (

Table 2) [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. SW is undetectable when the

swnK-T is knocked out in

M. robertsii. However, SW is determined again in the

swnK gene complementation strain, indicating that the SwnK protein plays an important role in SW synthesis. The SwnK protein is hypothesized to catalyze the production of 1-oxoindolizidine (or 1-hydroxyindolizine) from

L-pipecolic acid (

L-PA) [

19,

20].

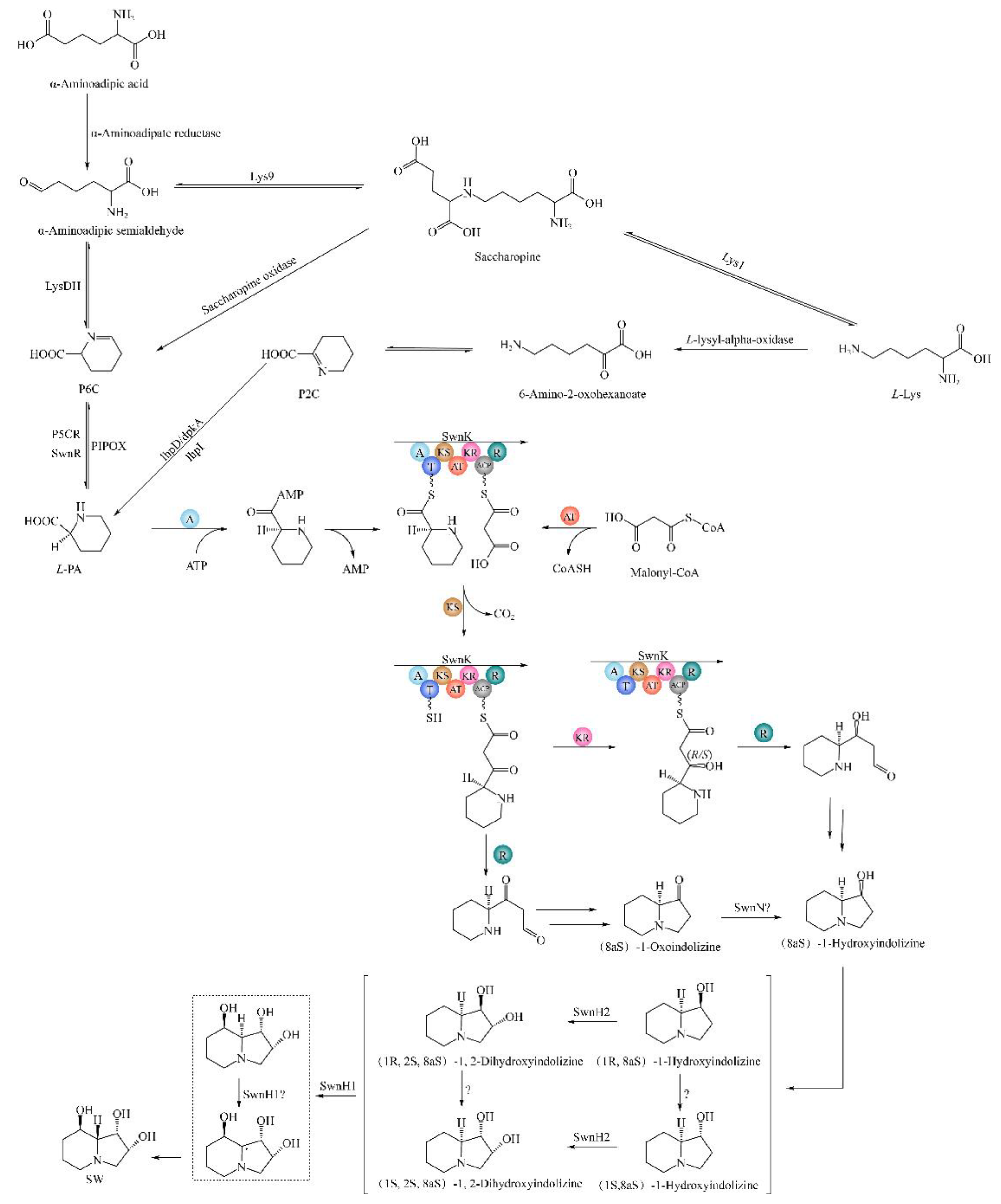

Research on SW biosynthesis pathway in fungi began with

Rhizoctonia leguminicola, followed by in

M. robertsii and

A. oxytropis [

19,

20,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. The predicted SW biosynthesis pathway in

R. leguminicola is as follows:

L-lysine → saccharopine → α-aminoadipic semialdehyde → P6C →

L-PA → 1-oxoindolizidine → 1-hydroxyindolizine → 1,2-dihydroxyindolizine → SW (

Figure 1A) [

25]. The predicted SW biosynthesis pathway from

L-lysine to L-PA has 2 branches in

M. robertsii:

L-lysine →

L-PA and

L-lysine → P6C →

L-PA. From

L-PA to SW, there are also 2 branches:

L-PA → 1-oxoindolizidine → 1-hydroxyindolizine → 1,2-dihydroxyindolizine → SW and

L-PA → 1-hydroxyindolizine → 1,2-dihydroxyindolizine → SW (

Figure 1B) [

19]. The predicted SW biosynthesis pathway has 2 branches in

A. oxytropis:

L-lysine ↔ saccharopine → α-aminoadipic semialdehyde → P6C →

L-PA → 1-hydroxyindolizine → SW and

L-lysine → 6-amino-2-oxohexanoate → P2C →

L-PA→ 1-hydroxyindolizine → SW [

26].

In this study, the whole-genome sequencing of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 was conducted, and the swnK gene was cloned and knocked out to identify the gene function impacting on SW biosynthesis. Multi-omics analyses were performed on ∆swnK-ACP and OW 7.8 to predict the SW biosynthesis pathway in A. oxytropis OW 7.8. Our findings lay the foundation of in-depth analysis of the molecular mechanisms and metabolic pathway of SW synthesis in fungi. Thus, providing reference for future control of SW in locoweed, and ultimately benefit the develop-ment of grassland animal husbandry and sustain the use of grassland ecosystem.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 was isolated by our research group from

Oxytropis glabra collected in Wushen banner, Ordos city, Inner Mongolia, China (108°52′E, 38°36′N, elevation 1291 m) [

29]. The mycelia were cultured on PDA media at 25°C for further use.

2.2. Whole Genome Sequencing of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 Strain

Mycelia of

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 cultured for 20 days were used to extract genomic DNA (Plant Genomic DNA Extraction Kit, Takara). A 350 bp Illumina library and a 20 Kb SMRT Bell library were separately constructed and sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq PE150 platform and the PacBio Sequel platform, respectively (Novogene). Genome assembly was performed using SMRT Link software. 3 methods were used for gene prediction: de novo prediction (Augustus [

30]), homology prediction (Genewise software [

31],

A. alternata genomes), and transcriptome-based prediction (Cufflinks software [

32], transcriptome of

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 [

26]). The final set of coding genes in

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 were obtained by integrating the above using EVidenceModeler software [

33]. Functional annotation of the coding genes was performed by using the Gene Ontology (GO) [

34] and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [

35] databases, and secondary metabolic gene cluster analysis was conducted (antiSMASH [

36]).

2.3. The Construction of the Phylogenetic Tree for the swnK Protein.

The intergenic regions of the SwnK proteins for 15 SW-producing fungi were obtained from NCBI for Pyrenophora seminiperda (RMZ73569), Slafractonia leguminicola (AQV04236), Alternaria oxytropis Raft River (AQV04230), Alternaria oxytropis OW 7.8 (ON520900), Nannizzia gypsea (XP_003176907), Trichophyton benhamiae (XP_003014124), Trichophyton rubrum (XP_003238870), Trichophyton equinum (EGE01982), Trichophyton interdigitale (EZF30502), Metarhizium brunneum (XP_014543166), Metarhizium guizhouense (KID83603), Metarhizium majus (KID96318), Metarhizium robertsii (XP_007824811), Chaetothyriaceae sp. (AQV04224), and Ilyonectria destructans (KAH7007558.1) as the outgroup. The amino acid sequences were aligned by using the ClustalW algorithm, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed by using the neighbor-joining method in the MEGA11 software.

2.4. Extraction of Genomic DNA and Identification of swnK Gene from A. oxytropis OW 7.8

The genomic DNA of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 was extracted (Plant Genomic DNA Kit, TIANGEN). The quality of the DNA was verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Primers swnK-F (5’-ATGCTGACCCCAGCCGTGT-3’) and swnK-R (5’-TTACGCCTGTGCTTTAGCAGC-3’) were designed based on the genomic data of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 to amplify the swnK gene. The PCR program was as follows: 98°C for 1 min; 98°C for 7 s, 63°C for 25 s, 72°C for 5 min, repeated for 30 cycles; and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were detected using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, purified (SanPrep Column PCR Product Purification Kit, Sangon Biotech), and then sequenced (Sangon Biotech).

2.5. Construction of the swnK-ACP Gene Knockout Vector

The upstream and downstream homologous sequences of the swnK-ACP were amplified using the genomic DNA of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 as a template. The hygromycin phosphotransferase gene (hpt) was amplified using the pCT74 plasmid (MiaoLingBio) as a template. The upstream and downstream homologous sequences of the swnK-ACP were linked to the hpt gene on both sides using overlapping PCR to construct the swnK-ACP gene knockout cassette, and this cassette was then ligated into the pMD-19T vector (Takara) using TA cloning to make up the swnK-ACP gene knockout vector.

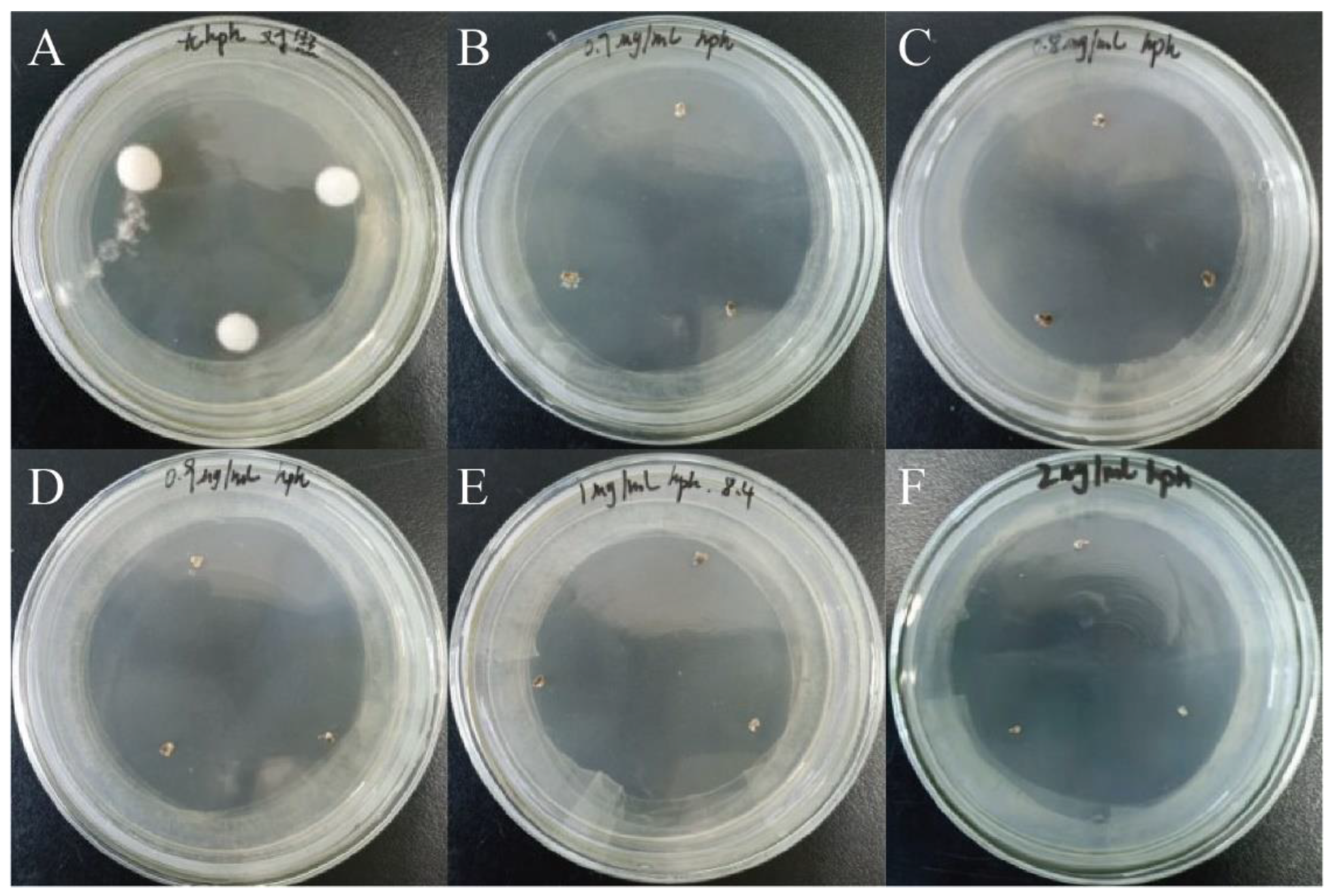

2.6. Sensitivity Test of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 to Hygromycin B

The mycelia of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 were inoculated on PDA media containing 0 μg/mL, 0.7 μg/mL, 0.8 μg/mL, 0.9 μg/mL, 1.0 μg/mL, and 2.0 μg/mL of hygromycin B (Hyg B), respectively. The fungi were incubated at 25°C for 30 days. The growth of colonies was observed, and an appropriate concentration of Hyg B was chosen to add the media for transformants screening.

2.7. Preparation and Transformation of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 Protoplasts

Preparation and transformation of protoplasts was done as described by Hu et al. [

37]. The mycelia of

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 grown on PDA medias were transferred into each 150 mL flask of PDB liquid culture medias, and incubated at 25℃, 180 rpm for 5 days. The resulting mycelia were filtered through sterile miracloth. To the collected hyphae were added different concentrations of enzymatic hydrolysate (3% Driselase, 1% Lysing enzyme, 0.04% Chitinase) prepared with 1.2 mol/L MgSO

4(pH5.8), and hydrolyzed at 30℃, 80 rpm 4 h. The enzymatically digested mixtures were filtered through a layer of sterile miracloth into a sterile 50 mL centrifuge tube, and the protoplasts were washed extensively with 1.2 mol/L MgSO

4 and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature. After discarding the supernatant, 5mL of STC Buffer (1 mol/L Sorbitol; 100 mmol/L Tris–HCl; 100 mmol/L CaCl

2) were added and the protoplasts were gently resuspended. The mixture was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. After discarding the supernatant, 1 mL of STC Buffer was added. Finally, protoplasts were adjusted to 2–5 × 10

6/mL for subsequent experiments.

Approximately 5–10 μg of the linearized swnk knockout vector was added to 15 mL centrifuge tube containing 2–5 × 106/mL protoplasts, and incubated at Ice bath for 30 min without shaking. Then 1 mL of SPTC (40% PEG 8000 dissolved in STC Buffer) were added to the tube (mixed thoroughly by inversion) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min without shaking. The protoplasts were added to 10 mL of Bottom Agar (0.3% Yeast Extract, 0.3% acid hydrolyzed casein, 20% sucrose, 1% Agar) containing 50 μg/mL ampicillin. After incubation at 25℃ for 12 h, Top Agar (0.3% Yeast Extract, 0.3% acid hydrolyzed casein, 20% sucrose, 1.5% Agar) containing 50 μg/mL ampicillin and 2 μg/mL Hygromycin B was added. After 7-10 days, a single colony transformant grown on the plate was transferred to PDA medium containing 2 μg/mL Hygromycin B.

2.8. Screening and Identification of Transformants

Transformants resistant to Hyg B were screened and subjected to PCR analysis. The sequence of upstream homologous to swnK-ACP and hpt was amplified with primers ACPUF/ACPHR (5’-ATTGCGTCTGCGTTTGA-3’, 5’-GTTGTATCATCATCTAAGGCAC-3’). The sequence of hpt and downstream homologous to swnK-ACP was amplified with primers ACPHF/ACPDR (5’-TGGCTTGGCTGGAGCTAGTGGAGGTCAA-3’; 5’-CAGTAGAAGCAGCAACGAA-3’). The sequence of hpt was amplified with primers ACPHF/ACPHR (5’-TGGCTTGGCTGGAGCTAGTGGAGGTCAA-3’; 5’-GTTGTATCATCATCTAAGGCAC-3’). All PCR products were sequenced for verification (Sangon Biotech).

2.9. Extraction and Detection of SW in A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP Mycelia

Mycelia of

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and Δ

swnK-ACP cultured for 20 days were used for SW extraction by acetic acid-chloroform solution, purification by cation exchange resin and elution with 1 mol/L ammonia solution. The SW levels in the mycelia were determined by HPLC-MS, with three replicates for each sample [

38]. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA in GraphPad Prism software.

2.10. Transcriptome Analysis of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP

Mycelia of

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and Δ

swnK-ACP strains were cultured for 20 days, rapidly frozen with liquid nitrogen in cryovials, and then delivered in dry ice, with three replicates for each sample. Transcriptome sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Novogene). The data was analyzed using DESeq2 [

39] and clusterProfiler [

40] package in R. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs, |log

2(Fold Change)| ≥ 1 and padj ≤ 0.05 [

39,

41]) were subjected to functional enrichment analysis with KEGG and GO.

2.11. Metabolome Detection and Analysis of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP

Mycelia of

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and Δ

swnK-ACP strains were cultured for 20 days, rapidly frozen with liquid nitrogen in cryovials, and then delivered in dry ice, with five replicates for each sample. Metabolome was performed using HPLC-MS

2 (Novogene). The data was analyzed using Compound Discoverer [

42] package in R. The differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs, VIP > 1, |log

2(Fold Change)| ≥ 0.59 and P-value < 0.05 [

43,

44]) were subjected to functional enrichment analysis with KEGG.

3. Results

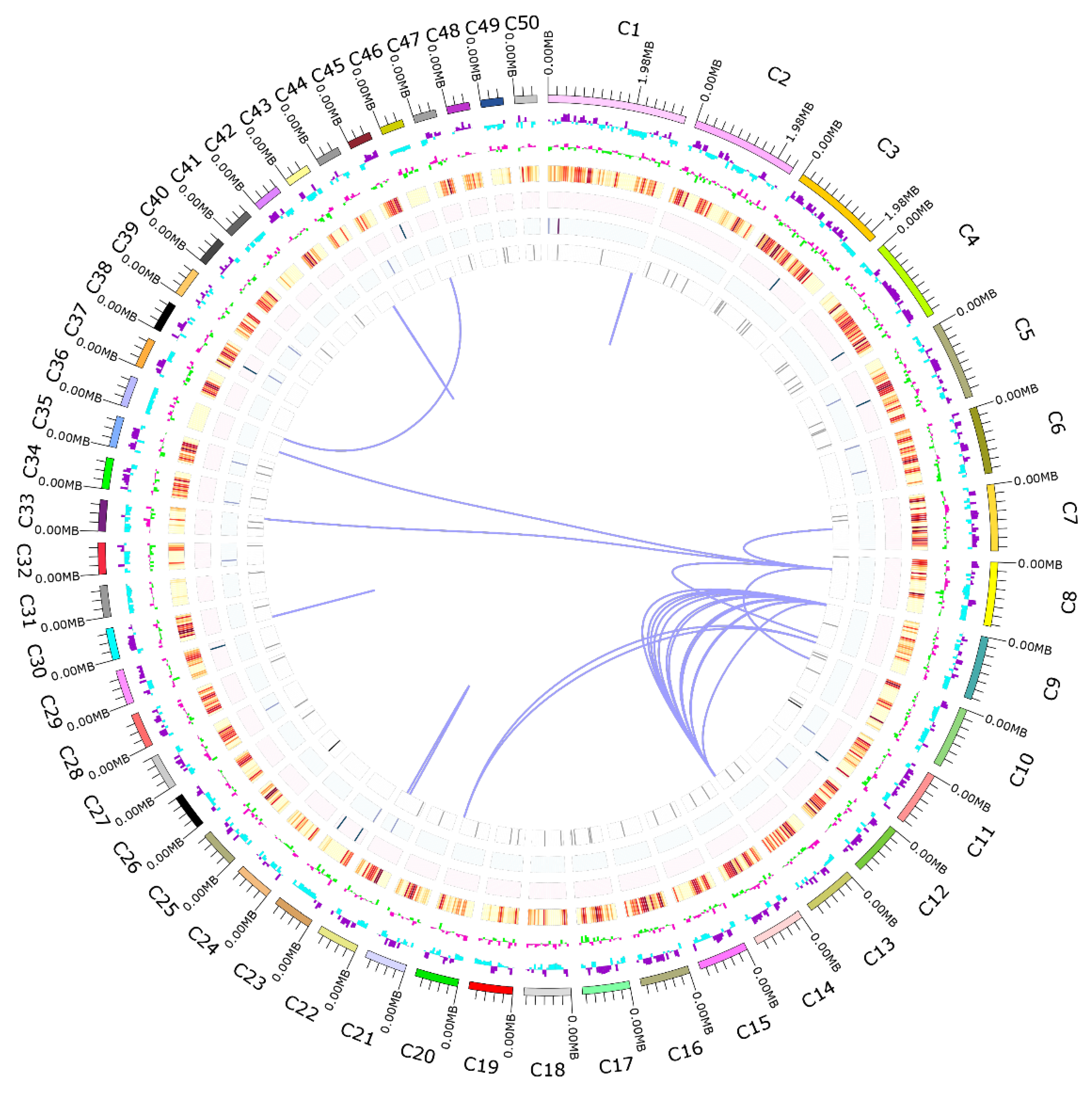

3.1. Genome Analysis of A. oxytropis OW 7.8

After filtering low quality and adapter contamination reads, the genome of

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 was sequenced and produced 6.94 Gb clean data, comprising 2,159,068 reads with an average read length of 3,215 bp and an N50 read length of 4,057 bp. The genome size was approximately 76.08 Mb, assembled into 210 contigs, with the longest contig being 3,106,266 bp and a contig N50 length of 712,767 bp. The GC content was approximately 39.86% (

Table 3). A total of 7,985 coding genes were annotated, with a total length of 10,928,077 bp and an average gene length of 1,369 bp. An overview of the genome was shown in

Figure 2.

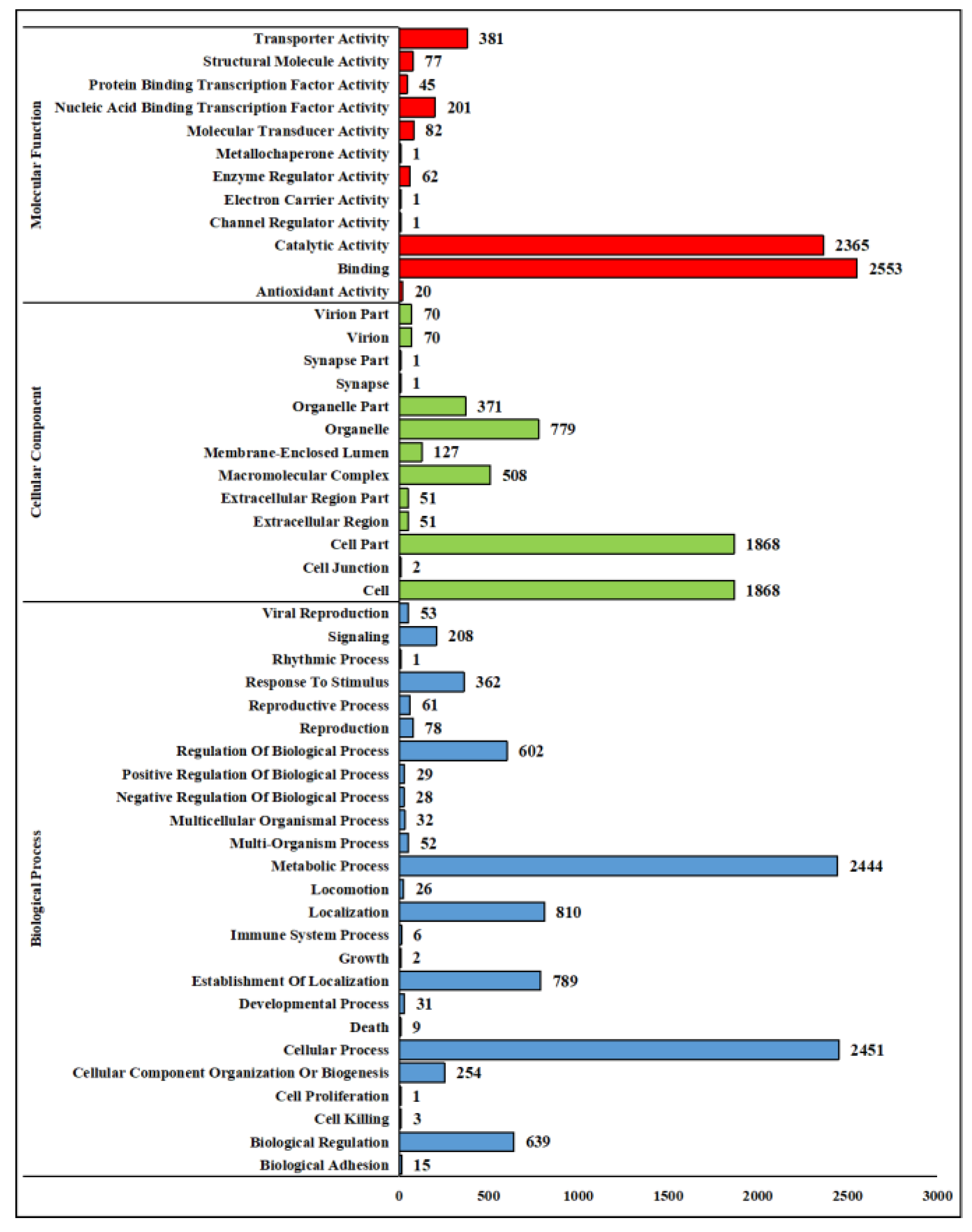

4,747 genes (59.45%) were annotated from the

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 genome in the GO database, covering 50 functional terms across 3 categories: Biological Process, Cellular Component, and Molecular Function. In the molecular functions category, the top 3 were binding (2,553 genes), catalytic activity (2,365 genes), and transporter activity (381 genes). In the Cellular Component category, the top 3 were cell (1,868 genes), cell part (779 genes), and organelle (779 genes). In the Biological Process category, the top 3 were cellular process (2,451 genes), metabolic process (2,444 genes), and localization (810 genes) (

Figure 3).

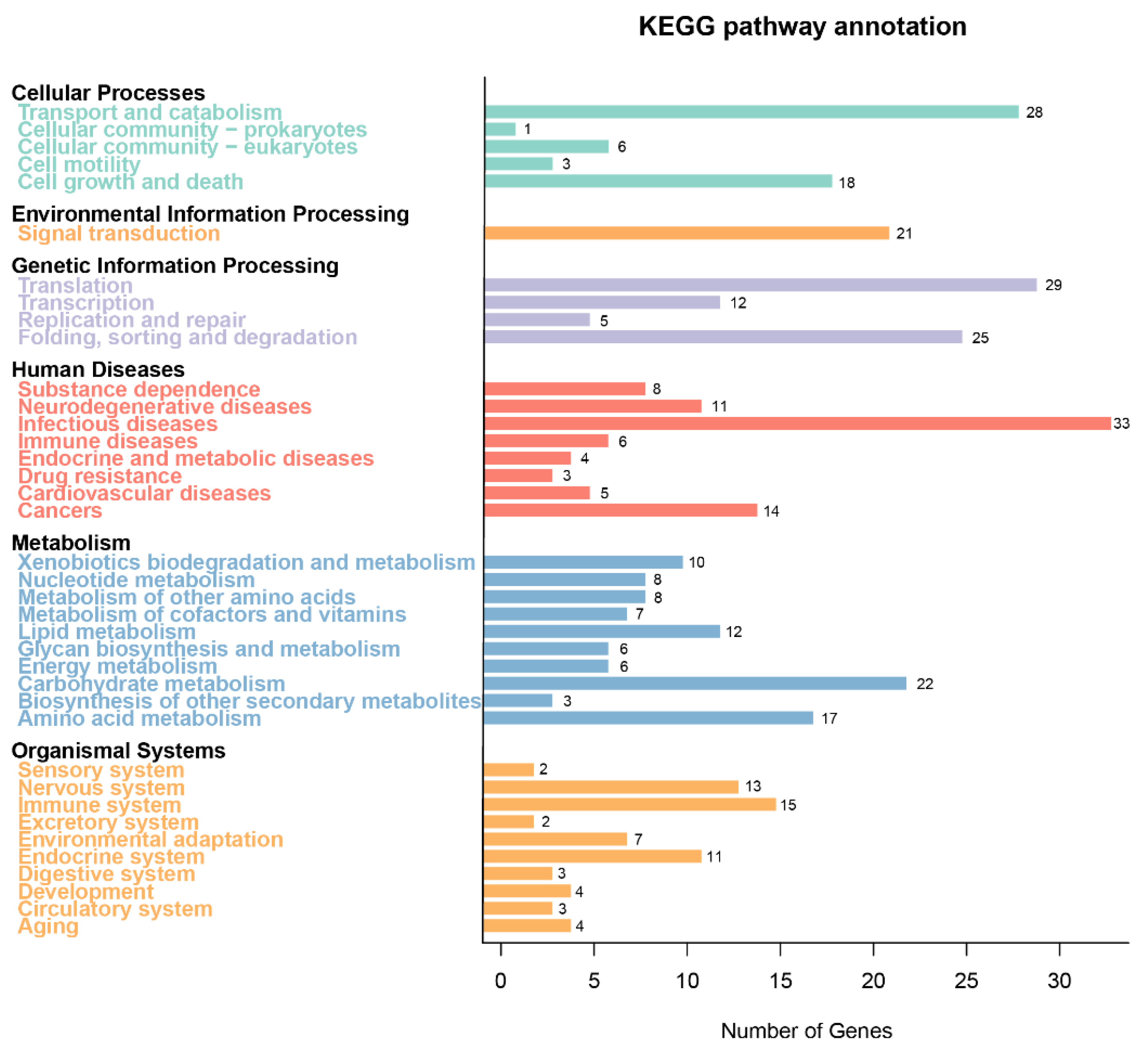

6,792 genes (85.06%) were annotated in the KEGG database, classified into 233 maps. The top 3 categories were Human Diseases, Metabolism, and Organismal Systems, followed by Cellular Processes, Environmental Information Processing, and Genetic Information Processing (

Figure 4).

27 secondary metabolism gene clusters comprising 209 genes were predicted in Secondary metabolism gene cluster analysis, which included 10 polyketide-related gene clusters containing 86 genes (2 t1 PKS-NRPS gene clusters with 22 genes; 7 t1 PKS gene clusters with 55 genes; 1 t3 PKS gene cluster with 9 genes). 5 members (

swnR,

swnK,

swnN,

swnH1,

swnH2) were identified in

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 by comparison with the SWN gene cluster sequence (KY365741.1) in

A. oxytopis Raft River [

19]. Genes closely related to SW biosynthesis, such as

LysDH,

LYS1,

LYS9,

P5CR, and

PIPOX, were also identified in the genome as well.

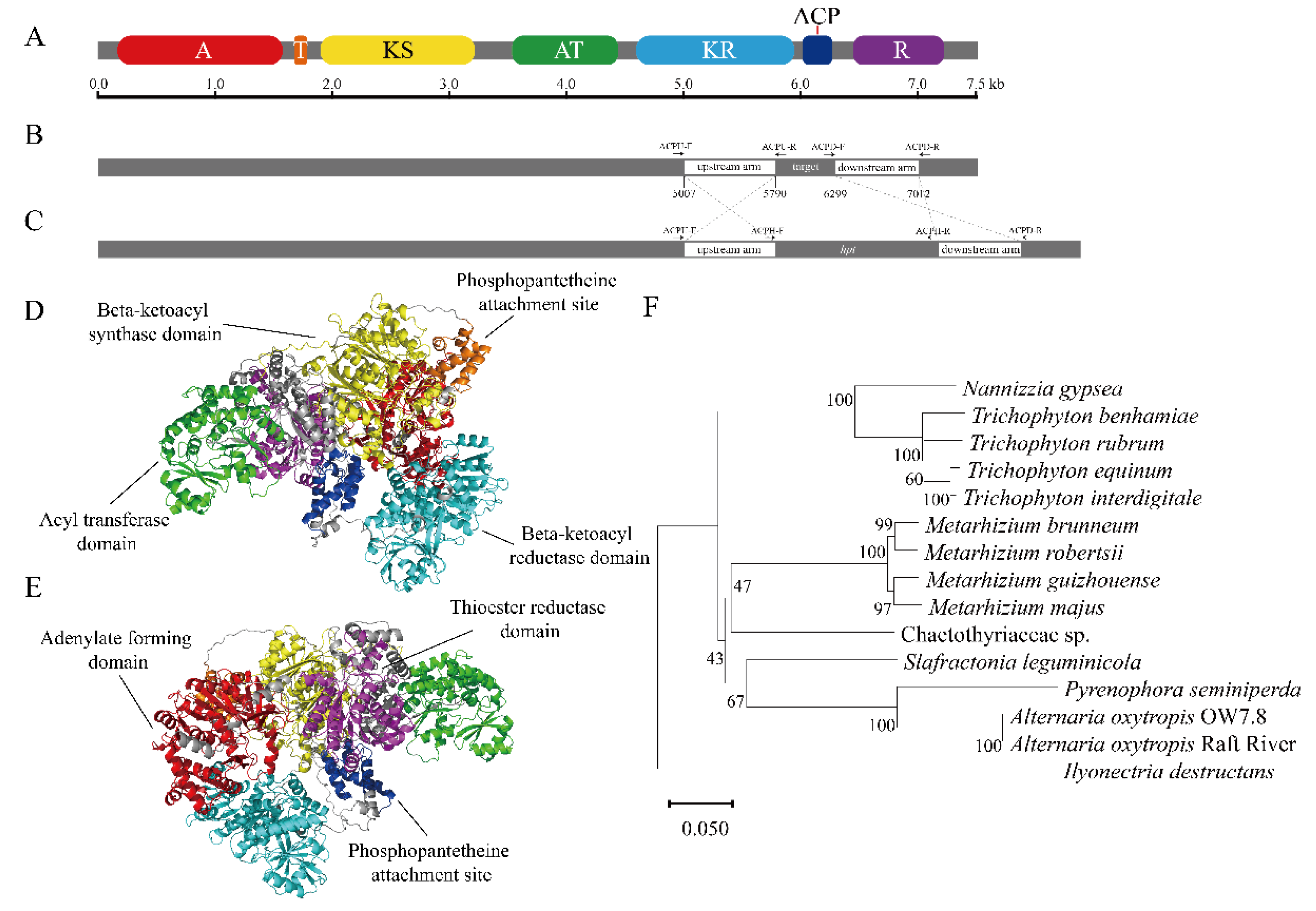

3.2. Identification and Bioinformatics Analysis of the swnK Gene in A. Oxytropis OW 7.8

The

swnK gene (GenBank: ON520900) in

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 was identified, with a length of 7,515 bp (ATG-TAG) and no introns. A multifunctional SwnK protein was predicted to encode 2,504 amino acids. The molecular formula of this protein was C

12080H

19145N

3345O

3626S

92, with an isoelectric point (pI) of 5.95 and a molecular weight of 272.20 kDa. The protein was hydrophilic, with no transmembrane domains and no signal peptides. 7 domains were predicted in the SwnK protein using the SMART online tool (

http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) (

Figure 5A). The advanced structure of the SwnK protein was predicted using the AlphaFold3 model (

Figure 5B,C) [

45].

A phylogenetic tree of SwnK proteins from 15 SW-producing fungi was constructed using the neighbor-joining method (

Figure 5D) with 2 branches: One branch consisted of 4 species of the genus

Trichophyton and one species of the genus

Nannizzia. Another branch was divided into upper and lower branches. The upper branch includes 4 species of the genus

Metarhizium and a separated branch of the Chaetothyriaceae fungi. In the lower branch, 2 fungi from

A. oxytropis clustered firstly, then they clustered with

Pyrenophora semeniperda, and finally clustered with the separately branched

Slafractonia leguminicola.

The amino acid sequence alignment of SwnK proteins shows that the highest sequence identity was 99.9% between A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and A. oxytropis Raft River. The sequence identities with Pyrenophora seminiperda, S. leguminicola, Chaetothyriaceae sp., and Nannizzia gypsea were 80.7%, 72.6%, 69.0%, and 65.6%, respectively. The sequence identities with the 4 Metarhizium species were approximately 68%, and with the 4 Trichophyton species were approximately 63%.

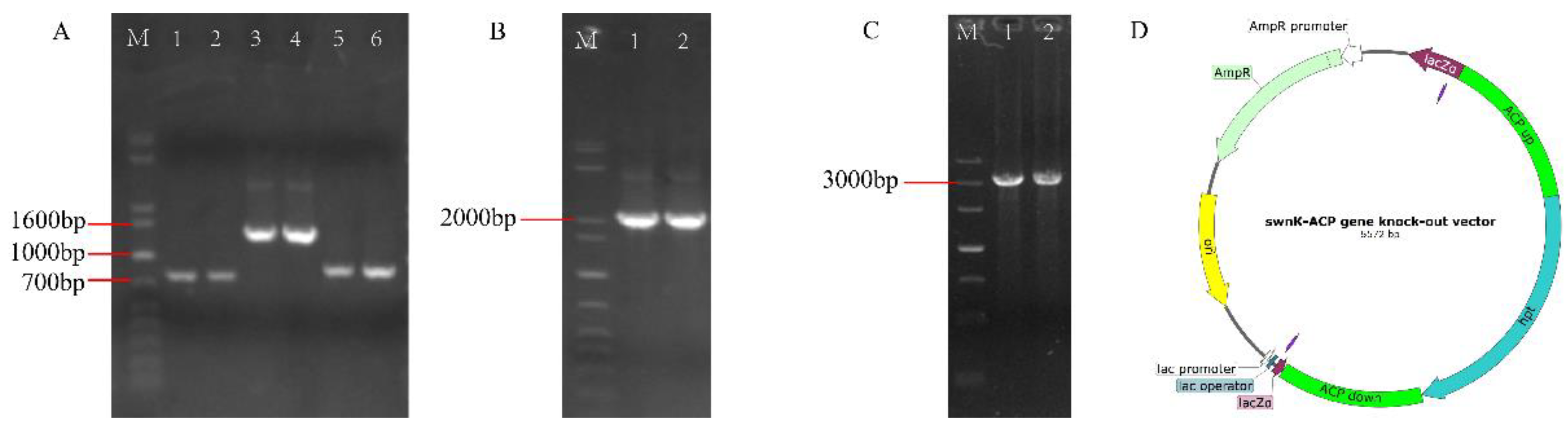

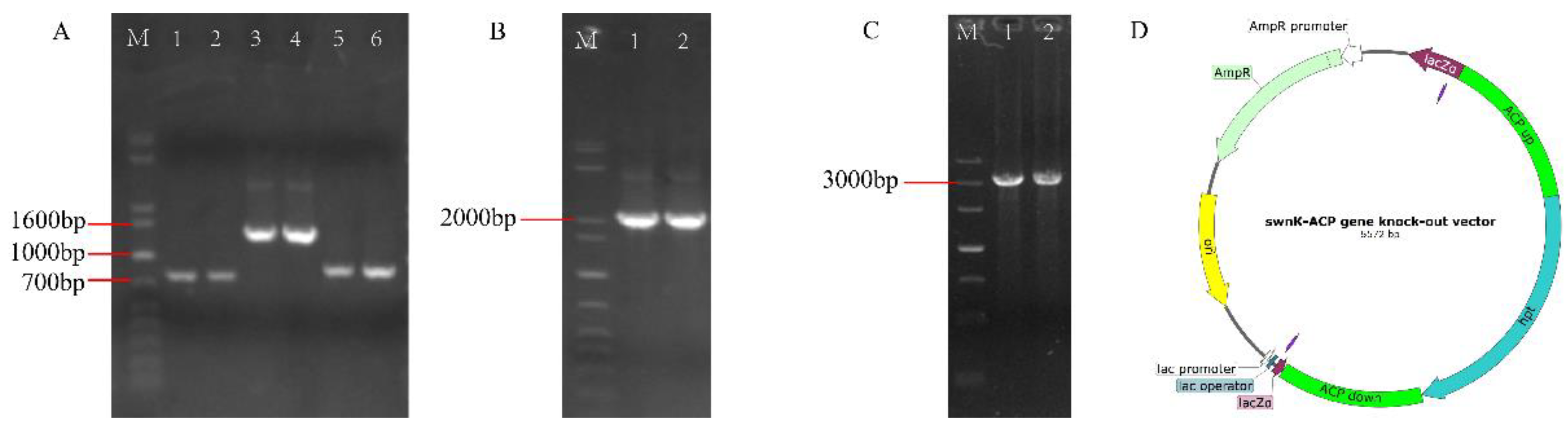

3.3. Construction of the swnK-ACP Gene Knockout Vector

The sequences of upstream and downstream homologous to the

swnK-ACP, along with the

hpt gene, were amplified (

Figure 6A). These 3 segments were then ligated to form the

swnK-ACP knockout cassette (

Figure 6B,C). This cassette was subsequently ligated with the pMD19-T vector to construct the

swnK-ACP gene knockout vector (

Figure 6D).

3.4. Sensitivity Testing of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 to Hyg B

After incubation in darkness at 25°C for 30 days, the growth of colonies of

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 on PDA media containing different concentrations of Hyg B was shown in

Figure 7, which indicated that the fungus was sensitive to ≥1 μg/mL of Hyg B.

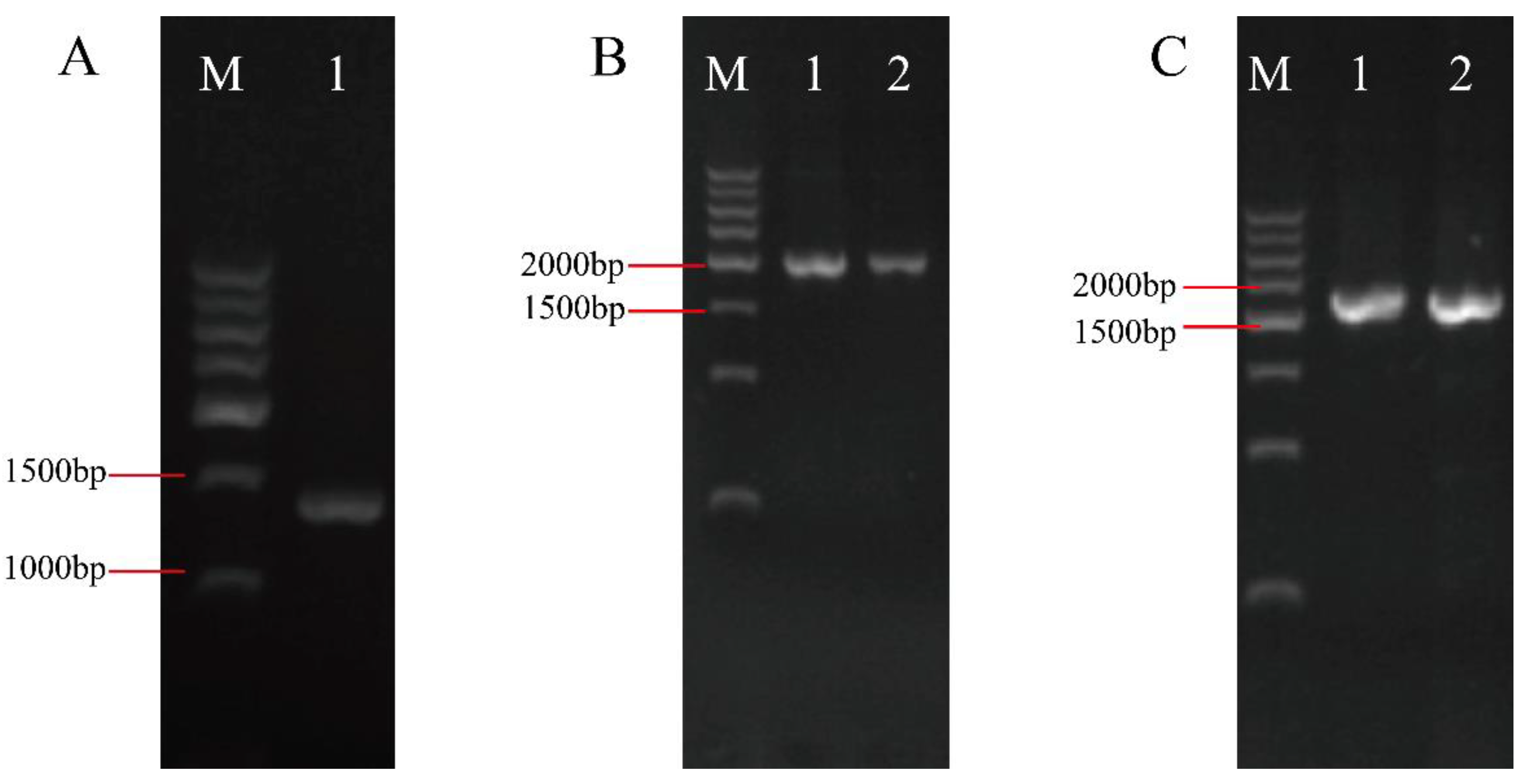

3.5. Identification of Transformants and Morphological Characteristics of ΔswnK-ACP Colonies

A few transformants gradually appeared on PDA media containing 2 μg/mL Hyg B one week after transformation. PCR results showed that the band of

hpt gene, the band of upstream homologous sequence to the

swnK-ACP and

hpt gene, the band of

hpt gene and downstream homologous sequence to the

swnK-ACP in the knockout strain ∆

swnK-ACP were amplified (

Figure 8). The sequencing of the products confirmed their accuracy, resulting in the identification of the gene knockout mutant strain ∆

swnK-ACP.

The colonies of

A. oxytropis OW7.8 displayed soft white velvety patches, round, raised, with uniform margin and radial growth colonies which grew slowly. Later a dark brown pigment was secreted in each colony [

17]. In contrast, the colonies of Δ

swnK-ACP appeared milky white or light yellow, with irregular shapes and slow growth. The colonies were loose and granular, with no pigment accumulation. In the later stages of growth, the colonies turned gray-black, with black pigment accumulating on both sides, forming a loose, stacked appearance.

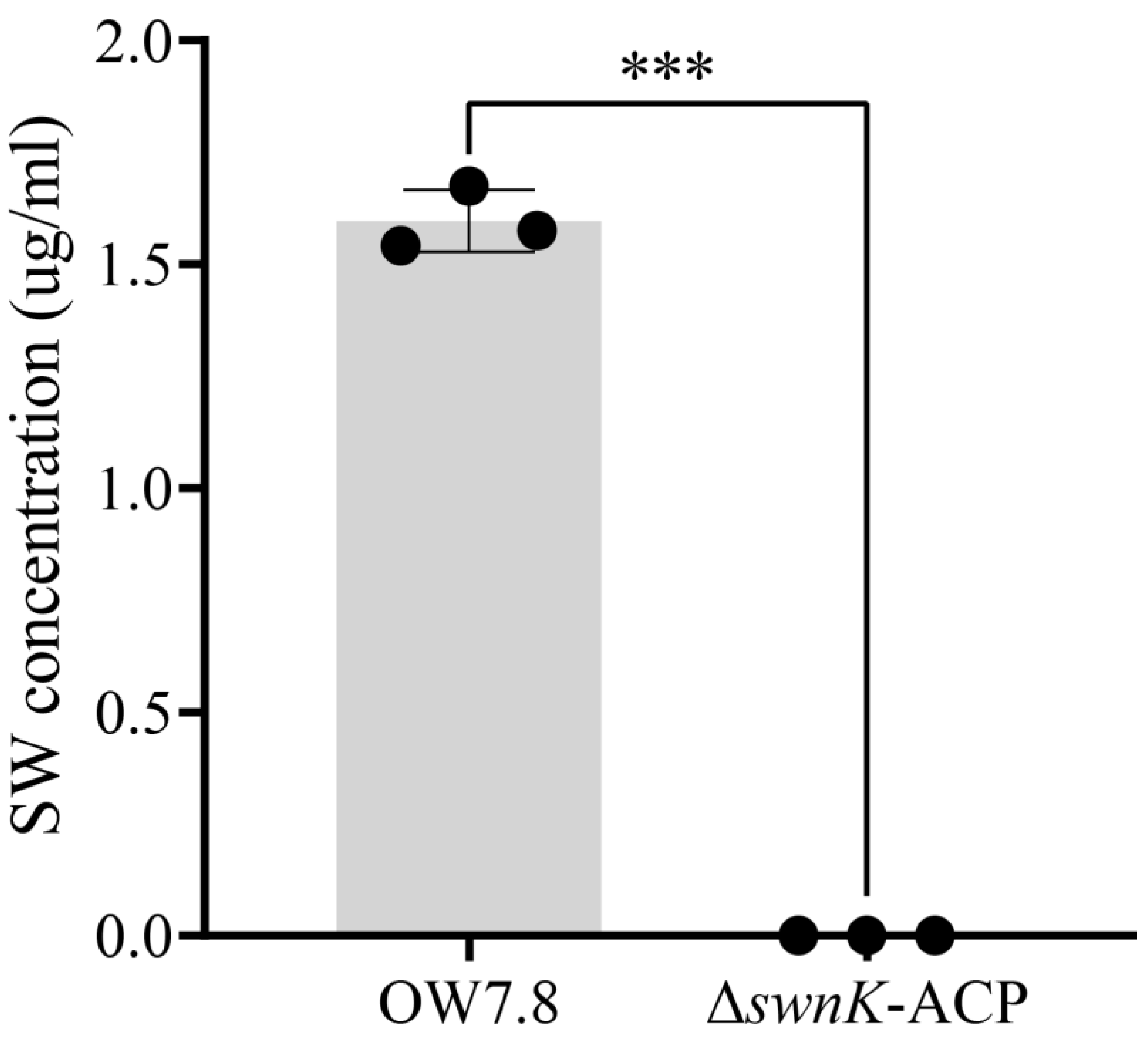

3.6. SW Levels in the Mycelia of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP

The regression equation for the SW standard curve was Y=0.3547X+0.0274 (R²=0.9936). SW was not detected in the mycelia of Δ

swnK-ACP, whereas the SW level in the mycelia of

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 was 1.15970±0.0402 μg/mL (

Figure 9) after 20 days of cultivation.

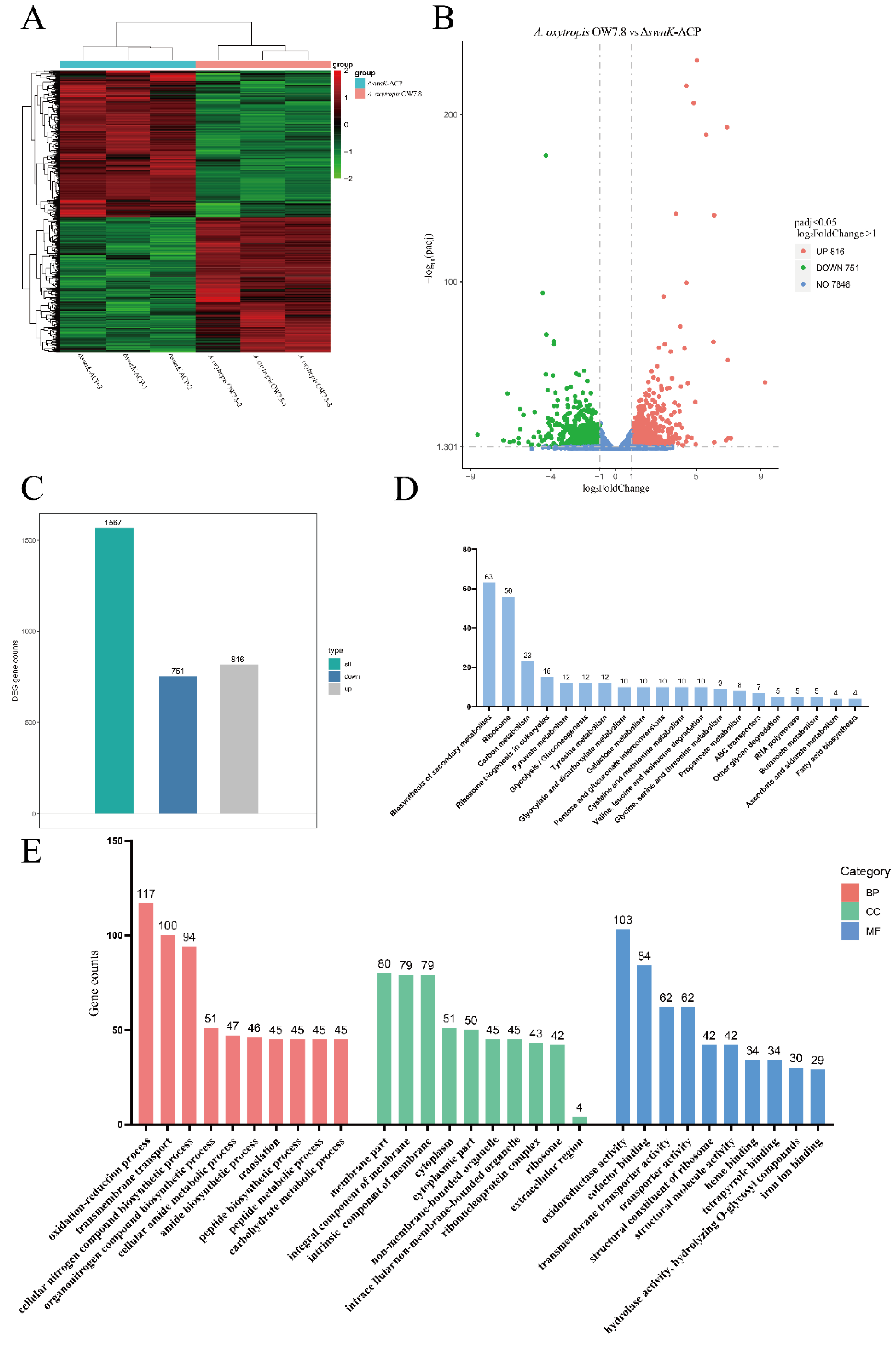

3.7. Transcriptome Analysis between A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP

Transcriptome sequencing of

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and Δ

swnK-ACP produced a total of 256,326,298 clean reads, amounting to 38.46 G. Differential expression of genes were shown between OW 7.8 and Δ

swnK-ACP (

Figure 10A). A total of 1,567 DEGs were identified, of which 816 (52.07%) were up-regulated and 751 (47.93%) were down-regulated (

Figure 10B,C). KEGG enrichment results indicated that the top two proportions of DEGs were related to secondary metabolism and ribosome biogenesis, followed by ribosome, carbon metabolism, ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes, biosynthesis of amino acids, and biosynthesis of cofactors, a total of 80 metabolic pathways (

Figure 10D) were obtained. 21 DEGs involved in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites were up-regulated and 42 were down-regulated; 56 DEGs involved in ribosomes were up-regulated; 6 DEGs involved in carbon metabolism were up-regulated and 17 were down-regulated; 15 DEGs involved in ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes were up-regulated; 6 DEGs involved in amino acid biosynthesis were up-regulated and 9 were down-regulated; 7 DEGs involved in cofactor biosynthesis were up-regulated and 6 were down-regulated.

The GO enrichment results indicated that the DEGs were involved in 225 biological processes, 47 cellular components, and 155 molecular functions. Processes with relatively great differences included oxidation-reduction process, transmembrane transport, membrane part, intrinsic component of membrane, oxidoreductase activity, and cofactor binding (

Figure 10E). Specifically, 45 DEGs were up-regulated and 72 were down-regulated for the oxidation-reduction process, 36 DEGs were up-regulated and 64 were down-regulated for transmembrane transport; 27 DEGs were up-regulated and 53 were down-regulated for membrane part; 26 DEGs were up-regulated and 53 were down-regulated for intrinsic component of membrane; 41 DEGs were up-regulated and 62 were down-regulated for oxidoreductase activity; 36 DEGs were up-regulated and 48 were down-regulated for cofactor binding.

8 DEGs closely related to SW synthesis were identified, among which the genes of LysDH, LYS1, LYS9, P5CR, and PIPOX were up-regulated, while the genes of swnN, swnH1, and swnR were down-regulated. There was no swnK transcripts detected from ΔswnK-ACP transcriptomics.

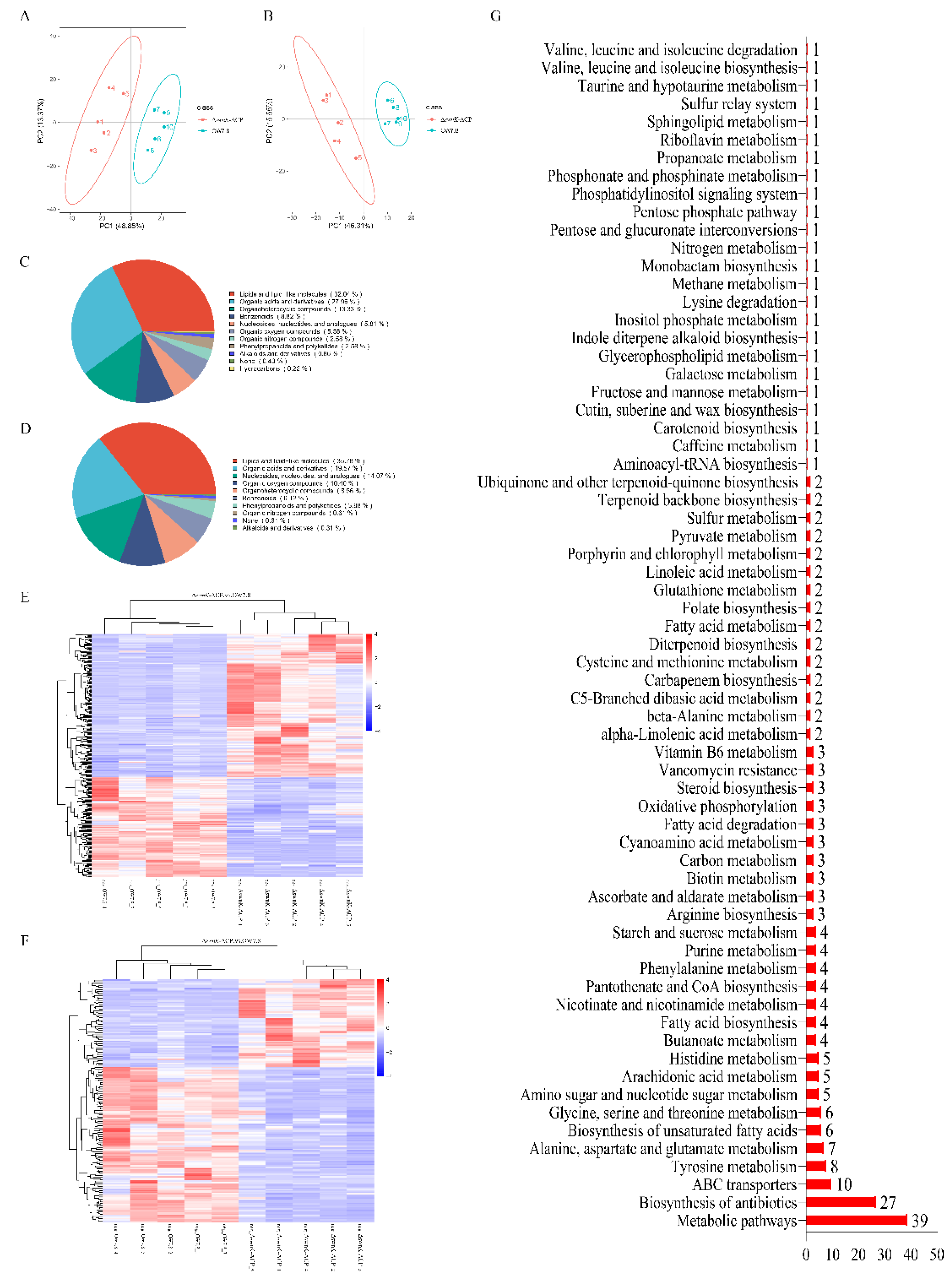

3.8. Metabolome Analysis between A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP

The principal component analysis (PCA) of the metabolome data for

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and Δ

swnK-ACP was shown in

Figure 11A,B, indicating differences in metabolites between Δ

swnK-ACP and OW 7.8. In positive ion mode, the most abundant metabolites were lipids and lipid-like molecules (32.04%), followed by phenylpropanoids and polyketides (2.58%), and alkaloids and derivatives (0.86%). In negative ion mode, the most abundant metabolites were lipids and lipid-like molecules (35.78%), followed by organic heterocyclic compounds (8.56%), phenylpropanoids and polyketides (3.98%), and alkaloids and derivatives (0.31%) (

Figure 11C,D). In positive ion mode, 345 DEMs were identified, with 203 up-regulated and 142 down-regulated. In negative ion mode, 175 DEMs were identified, with 63 up-regulated and 112 down-regulated (

Table 4).

KEGG enrichment analysis was performed on 520 DEMs, with a total of 90 DEMs annotated and enriched into 66 metabolic groups, including 39 DEMs for metabolic pathways, 27 DEMs for antibiotic biosynthesis, 10 DEMs for ABC transporter, 8 DEMs for tyrosine metabolism, 7 DEMs for alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, (

Figure 11G). 7 DEMs involved in SW synthesis were identified with

L-PA,

L-Lysine,

L-Stachydrine,

L-Proline,

L-Glutamate, α-Aminoadipic Semialdehyde, and Saccharopine all up-regulating.

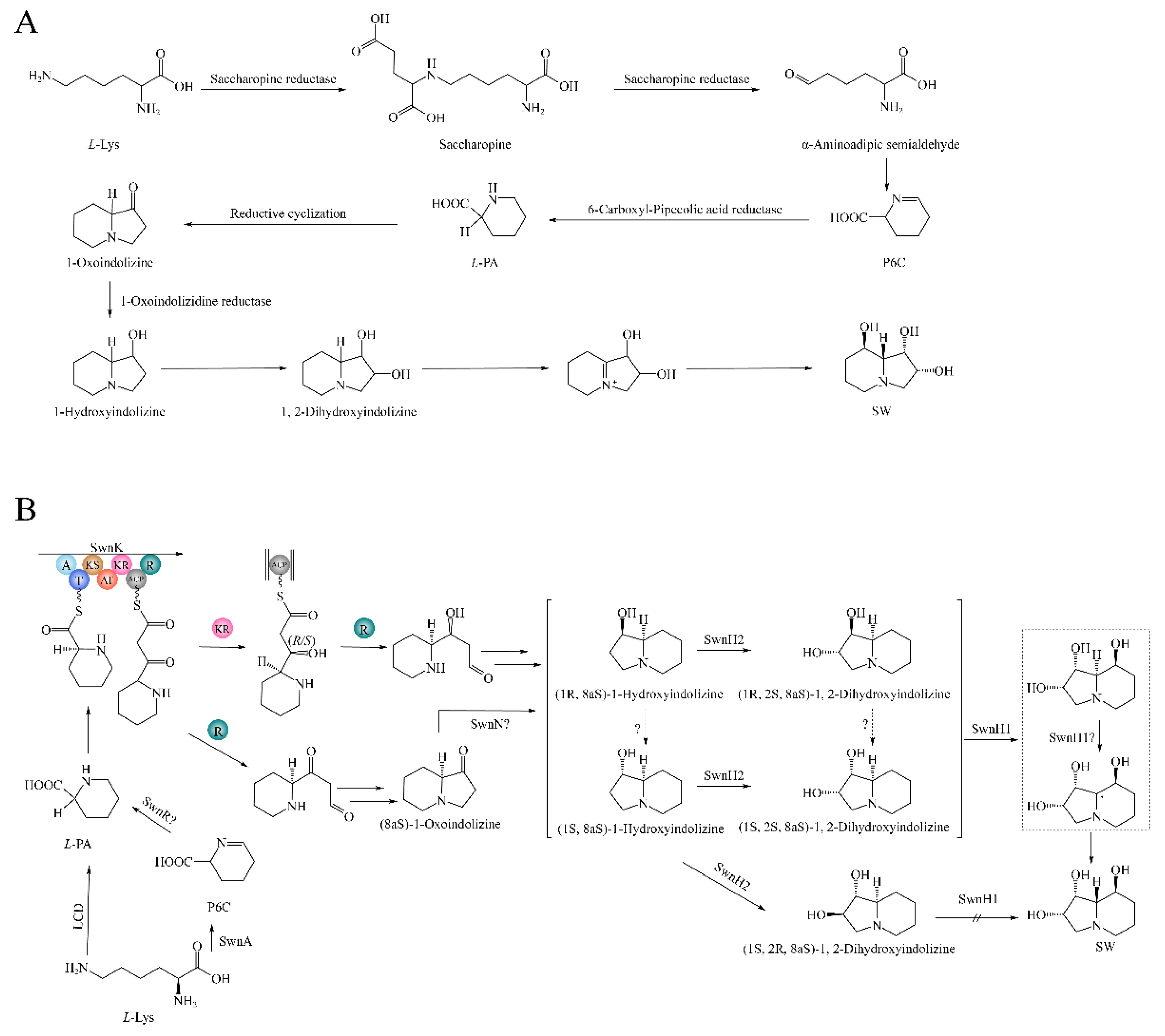

3.9. Hypothesized SW Biosynthesis Pathway in A. oxytropis OW 7.8

The predicted SW biosynthesis pathway in

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 was shown in

Figure 12, starting from

L-lysine artificially. The Sac enzyme catalyzes the synthesis of saccharopine from

L-lysine. Saccharopine was reduced to α-aminoadipic semialdehyde (α-aminoadipic semialdehyde was also formed from α-aminoadipic acid catalyzed by α-aminoadipate reductase). α-Aminoadipic semialdehyde cyclizes to form P6C (P6C was also formed from saccharopine catalyzed by saccharopine oxidase). P6C was then catalyzed to form

L-PA by the P5CR enzyme or SwnR enzyme. There might be an alternative pathway synthesizing

L-PA, in which

L-lysine was converted to 6-amino-2-oxohexanoate catalyzed by

L-lysyl-alpha-oxidase. 6-Amino-2-oxohexanoate isomerizes to form P2C, which was subsequently catalyzed by the enzymes lhpD/dpkA (delta-1-piperideine-2-carboxylate reductase) and lhpI (1-piperideine-2-carboxylate reductase) to produce

L-PA.

L-PA was converted to (8aS)-1-oxoindolizine, (1R,8aS)-1-hydroxyindolizine, or (1S,8aS)-1-hydroxyindolizine by the action of multifunctional SwnK protein. Subsequently, (8aS)-1-hydroxyindolizine was synthesized form (8aS)-1-oxoindolizine by the SwnN enzyme. (1R,2S,8aS)-1,2-dihydroxyindolizine was synthesized from (1R,8aS)-1-hydroxyindolizine by the action of the SwnH2 enzyme. (1S,2S,8aS)-1,2-dihydroxyindolizine was synthesized from (1S,8aS)-1-hydroxyindolizine by the action of the SwnH2 enzyme. Finally, (1S,2S,8R,8aR)-1,2,8-octahydroindolizinetriol (SW) was synthesized from (1R,2S,8aS)-1,2-dihydroxyindolizine or (1S,2S,8aS)-1,2-dihydroxyindolizine synthesized, by the action of the SwnH1 enzyme.

4. Discussion

The genome size of

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 (76.08 Mb) was larger than that of

Undifilum oxytropis OK3UNF (70.05 Mb) [

46] and an

A. oxytropis strain (74.48 Mb) [

47]. The GC content in

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 (39.86%) genome was lower than that in

U. oxytropis OK3UNF (40.37%) [

46] and

A. oxytropis (40.01%) [

47]. The identities of amino acid sequences of the protein SwnK, SwnN, SwnR, SwnH1, and SwnH2 between

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and

A. oxytropis Raft River [

19] were 99.9%, 99.7%, 100.0%, 100.0%, and 99.70%, respectively. In contrast, the identities of amino acid sequences between

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and

M. anisopliae ARSEF 549 [

19] were 67.35%, 71.30%, 69.18%, 77.52%, and 77.95%, respectively. The nucleotide sequence identity of

swnK gene between

A. oxytropis OW7.8 and

A. oxytropis Raft River [

19] was 99.9% indicating a close phylogenetic relationship with 3 differential sites. There were 2 missense mutations (at 1396, C in OW 7.8 encoding cysteine, T in Raft River encoding arginine; at 4885, G in OW 7.8 encoding alanine, T in Raft River encoding serine) and 1 synonymous mutation (at 6235, T in OW 7.8 and C in Raft River, both encoding leucine). No SW was detected in our Δ

swnK-ACP, consistent with results in

M. anisopliae and

M. robertsii with undetectable SW level in the

swnK gene knockout strains [

19,

20,

48], suggesting that the function of

swnK gene promotes SW synthesis in these fungi. The endophytic fungus

A. oxytropis OW7.8 exhibits a very slow growth rate and long growing cycle in vitro, with a very low homologous recombination rate, resulting in few transformants after long-term exploration.

Compared to A. oxytropis OW 7.8, the ΔswnK-ACP strain showed up-regulation of the genes of LysDH, LYS1, LYS9, P5CR, and PIPOX, and down-regulation of swnN, swnH1, and swnR. The genes of LysDH, LYS1, LYS9, and P5CR encode enzymes involved in L-PA synthesis, and PIPOX encodes an enzyme involved in L-PA degradation. The above reactions occur upstream of the reactions catalyzed by SwnK protein. The inability of ΔswnK-ACP converting L-PA into 1-hydroxyindolizine results in L-PA accumulation. Increased L-PA levels was also detected in metabolome analysis. However, the reactions catalyzed by the gene products of swnN, swnH1, and swnR occur downstream of the SwnK multifunctional protein-catalyzed reactions, resulting in their down-regulation.

In ΔswnK-ACP, levels of L-PA, L-lysine, L-stachydrine, L-proline, L-glutamate, α-aminoadipic Semialdehyde, and saccharopine were all up-regulated compared to A. oxytropis OW 7.8. α-Aminoadipic semialdehyde, saccharopine, L-PA, and L-lysine were important precursors in the SW biosynthesis pathway. The multifunctional SwnK protein in A. oxytropis OW 7.8 catalyzes the production 1-hydroxyindolizine from L-PA. In ΔswnK-ACP, 1-hydroxyindolizine cannot be synthesized, and upstream metabolites, such as L-PA, α-aminoadipic semialdehyde, saccharopine, and L-lysine were up-regulated. Other metabolic pathways related to these metabolites were also affected. Specifically, L-PA and L-glutamate synthesize L-proline, and L-stachydrine was a derivative of L-proline.

The previously predicted SW biosynthesis pathway in

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 included P6C and P2C branches [

26]. In this study, the P6C branch in

A. oxytropis OW 7.8 was refined, predicting that α-aminoadipic semialdehyde can also be produced from α-aminoadipic acid catalyzed by α-aminoadipate reductase, and P6C can also be formed from saccharopine catalyzed by saccharopine oxidase. The pathway from

L-PA to SW was also refined, including the production of

L-PA to (8aS)-1-indolizidinone, (1R,8aS)-1-hydroxyindolizine or (1S,8aS)-1-hydroxyindolizine by action of the SwnK protein, the production of (8aS)-1-hydroxyindolizine catalyzed from (8aS)-1-oxoindolizine catalyzed by the SwnN enzyme, the production of (1R,2S,8aS)-1,2-dihydroxyindolizine or (1S,2S,8aS)-1,2-dihydroxyindolizine from (1R,8aS)-1-hydroxyindolizine or (1S,8aS)-1-hydroxyindolizine catalyzed by the SwnH2 enzyme and the production of SW from (1R,2S,8aS)-1,2-dihydroxyindolizine or (1S,2S,8aS)-1,2-dihydroxyindolizine catalyzed by the SwnH1 enzyme.

No SW was detected, and

L-PA level was up-regulated in Δ

swnK-ACP. It has been reported that

L-PA synthesized by

M. robertsii induces systemic acquired resistance (SAR) in

Arabidopsis thaliana in symbiosis of

Arabidopsis thaliana and

M. robertsii [

49,

50,

51], which provides a new possibility for future to remove SW and enhance SAR from

Oxytropis glabra by use of Δ

swnK-ACP and to make better forage germplasm of

Oxytropis glabra.

5. Conclusions

Genomic sequencing of Alternaria oxytropis OW 7.8 isolated from Oxytropis glabra was performed, the swnK gene was cloned and knocked out firstly. The colony morphology of ΔswnK-ACP differed from that of A. oxytropis OW 7.8, appearing milky white or pale yellow, with irregular shape and a slower growth rate. SW was not detected in ΔswnK-ACP, indicating that the swnK gene promotes SW synthesis in A. oxytropis OW 7.8. 8 DEGs closely associated with SW biosynthesis were identified in the transcriptome analysis between A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP with the genes of LysDH, LYS1, LYS9, P5CR, and PIPOX up-regulating, the genes of swnN, swnH1, and swnR down-regulating. 7 DEMs closely related to SW synthesis were identified in the metabolome analysis between A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP with L-PA, L-lysine, L-sachydrine, L-proline, L-glutamate, α-aminoadipic semialdehyde, and saccharopine all up-regulating. The SW biosynthesis pathway in A. oxytropis OW 7.8 was hypothesized and refined.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L.; methodology, P.L. Y.L. and F.Y.; investigation, P.L., Y.L., F.Y., W.W., L.Z., L.K. and L.B.; data curation, Y.L., F.Y., P.L., W.W., L.Z., L.K. and L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and F.Y.; writing—review and editing, P.L., Y.L. and F.Y visualization, Y.L., F.Y., W.W., L.Z., L.K. and L.B.; supervision, P.L.; project administration, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31460235; 31960130; 30860049), Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China (2020MS03014), Fundamental Research Funds for the Inner Mongolia Normal University (2022JBTD010).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the confidentiality of our current genomic data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Molyneux, R.J.; McKenzie, R.A.; O’Sullivan, B.M.; Elbein, A.D. Identification of the Glycosidase Inhibitors Swainsonine and Calystegine B2 in Weir Vine (Ipomoea Sp. Q6 {AFF. CALOBRA}) and Correlation with Toxicity. J. Nat. Prod. 1995, 58, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.T.; Zhao, Q.M.; Wang, J.N.; Wang, J.H.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y.M.; Geng, G.X.; Li, Q. Swainsonine-Producing Fungal Endophytes from Major Locoweed Species in China. Toxicon 2010, 56, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.; Ralphs, M.H.; Welch, K.D.; Stegelmeier, B.L. Locoweed Poisoning in Livestock. Rangelands 2009, 31, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C.; Wang, W.L.; Liu, X.X.; Ma, F.; Cao, D.D.; Yang, X.W.; Wang, S.S.; Geng, P.S.; Lu, H.; Zhao, B.Y. Pathogenesis and Preventive Treatment for Animal Disease Due to Locoweed Poisoning. Elsevier B.V. 2014, 37, 336–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, L.; Han, X.G.; Zhang, Z.B.; Sun, O.J. Grassland Ecosystems in China: Review of Current Knowledge and Research Advancement. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2007, 362, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Gardner, D.R.; Lee, S.T.; Pfister, J.A.; Stonecipher, C.A.; Welsh, S.L. A Swainsonine Survey of North American Astragalus and Oxytropis Taxa Implicated as Locoweeds. Toxicon 2016, 118, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.J.; Guo, Y.Z.; Huang, W.Y.; Guo, R.; Lu, H.; Wu, C.C.; Zhao, B.Y. The Distribution of Locoweed in Natural Grassland in the United States and the Current Status and Prospects of Research on Animal Poisoning. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2019, 27, 519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Q.Q.; Beckmann, M.; Phillips, H.; Meng, H.Z.; Mo, C.H.; Mur, L.A.J.; He, W. Host-Species Variation and Environment Influence Endophyte Symbiosis and Mycotoxin Levels in Chinese Oxytropis Species. Toxins 2022, 14, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulsiani, D.R.P.; Broquist, H.P.; James, L.F.; Touster, O. The Similar Effects of Swainsonine and Locoweed on Tissue Glycosidases and Oligosaccharides of the Pig Indicate That the Alkaloid Is the Principal Toxin Responsible for the Induction of Locoism. Elsevier B.V. 1984, 232, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Gardner, D.R.; Pfister, J.A. Swainsonine-Containing Plants and Their Relationship to Endophytic Fungi. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 7326–7334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, Q.N.; Clay, K.; Lee, S.T.; Gardner, D.R.; Cook, D. Phylogenetic Patterns of Bioactive Secondary Metabolites Produced by Fungal Endosymbionts in Morning Glories (Ipomoeeae, Convolvulaceae). New Phytol. 2023, 238, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, C.A.; Hume, D.E.; McCulley, R.L. FORAGES AND PASTURES SYMPOSIUM: Fungal Endophytes of Tall Fescue and Perennial Ryegrass: Pasture Friend or Foe? J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 2379–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.R.; Liu, X.; Mur, L.A.J.; Fu, Y.P.; Wei, Y.H.; Wang, J.; He, W. Rethinking of the Roles of Endophyte Symbiosis and Mycotoxin in Oxytropis Plants. JoF 2021, 7, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, K.; Romero, J.; Liddell, C.; Creamer, R. Production of Swainsonine by Fungal Endophytes of Locoweed. Mycol. Res. 2003, 107, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Nagao, H.; Li, Y.L.; Wang, H.S.; Kakishima, M. Embellisia Oxytropis, a New Species Isolated from Oxytropis Kansuensis in China. Mycotaxon 2006, 95, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor, B.M.; Creamer, R.; Shoemaker, R.A.; McLain-Romero, J.; Hambleton, S. Undifilum, a New Genus for Endophytic Embellisia Oxytropis and Parasitic Helminthosporium Bornmuelleri on Legumes. Botany 2009, 87, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Child, D.; Zhao, M.L.; Gardener, D.R.; Lv, G.F.; Han, G.D. Culture and Identification of Endophytic Fungi from Oxytropis Glabra DC. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2009, 29, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.; Li, X.; Wang, S.Y.; Gao, F.; Yuan, B.; Xi, L.J.; Du, L.; Hu, J.Y.; Zhao, L.N. Saccharopine Reductase Influences Production of Swainsonine in Alternaria oxytropis. Sydowia 2021, 73, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, D.; Donzelli, B.G.G.; Creamer, R.; Baucom, D.L.; Gardner, D.R.; Pan, J.; Moore, N.; Krasnoff, S.B.; Jaromczyk, J.W.; Schardl, C.L. Swainsonine Biosynthesis Genes in Diverse Symbiotic and Pathogenic Fungi. G3 Genes, Genomes, Genet. 2017, 7, 1791–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.F.; Hong, S.; Chen, B.; Yin, Y.; Tang, G.R.; Hu, F.L.; Zhang, H.Z.; Wang, C.S. Unveiling of Swainsonine Biosynthesis via a Multibranched Pathway in Fungi. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15, 2476–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyaz, M.; Das, S.; Cook, D.; Creamer, R. Phylogenetic Comparison of Swainsonine Biosynthetic Gene Clusters among Fungi. JoF 2022, 8, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.Q.; Zhang, H.D.; Zhao, Q.M.; Cui, S.W.; Yu, K.; Sun, R.H.; Yu, Y.T. Construction of Yeast One-Hybrid Library of Alternaria Oxytropis and Screening of Transcription Factors Regulating Swnk Gene Expression. JoF 2023, 9, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creamer, R.; Hille, D.B.; Neyaz, M.; Nusayr, T.; Schardl, C.L.; Cook, D. Genetic Relationships in the Toxin-Producing Fungal Endophyte, Alternaria Oxytropis Using Polyketide Synthase and Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthase Genes. JoF 2021, 7, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, K.L.; Perry, D. Analysis of Swainsonine and Its Early Metabolic Precursors in Cultures of Metarhizium Anisopliae. Glycoconjugate J. 1997, 14, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, T.M.; Harris, C.M.; Hill, J.E.; Ungemach, F.S.; Broquist, H.P.; Wickwire, B.M. (1S,2R,8aS)-1,2-Dihydroxyindolizidine Formation by Rhizoctonia Leguminicola, the Fungus That Produces Slaframine and Swainsonine. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 3094–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, P. Transcriptome Profiles of Alternaria Oxytropis Provides Insights into Swainsonine Biosynthesis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.N.; Yang, Z.; Hao, B.C.; Cheng, F.; Song, X.D.; Shang, X.F.; Zhao, H.X.; Shang, R.F.; Wang, X.H.; Liang, J.P.; et al. Screening of Endophytic Fungi in Locoweed Induced by Heavy-Ion Irradiation and Study on Swainsonine Biosynthesis Pathway. JoF 2022, 8, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Zhao, Q.; Yu, K.; Gao, Y.; Ma, Z.; Li, H.; Yu, Y. Transcriptomic Screening of Alternaria Oxytropis Isolated from Locoweed Plants for Genes Involved in Mycotoxin Swaisonine Production. JoF 2024, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.F.; Qian, Y.G.; Lu, P.; He, S.; Du, L.; Li, Y.L.; Gao, F. The Relationship between Swainsonine and Endophytic Fungi in Different Populations of Oxytropis Glabra from Inner Mongolia Chin. J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2022, 53, 304–314. [Google Scholar]

- Stanke, M.; Waack, S. Gene Prediction with a Hidden Markov Model and a New Intron Submodel. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, ii215–ii225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birney, E.; Clamp, M.; Durbin, R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapnell, C.; Roberts, A.; Goff, L.; Pertea, G.; Kim, D.; Kelley, D.R.; Pimentel, H.; Salzberg, S.L.; Rinn, J.L.; Pachter, L. Differential Gene and Transcript Expression Analysis of RNA-Seq Experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc 2012, 7, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, B.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Zhu, W.; Pertea, M.; Allen, J.E.; Orvis, J.; White, O.; Buell, C.R.; Wortman, J.R. Automated Eukaryotic Gene Structure Annotation Using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 2008, 9, R7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimmer, E.C.; Huntley, R.P.; Alam-Faruque, Y.; Sawford, T.; O’Donovan, C.; Martin, M.J.; Bely, B.; Browne, P.; Chan, W.M.; Eberhardt, R.; et al. The UniProt-GO Annotation Database in 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D565–D570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Kawashima, S.; Nakaya, A. The KEGG Databases at GenomeNet. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blin, K.; Medema, M.H.; Kazempour, D.; Fischbach, M.A.; Breitling, R.; Takano, E.; Weber, T. antiSMASH 2.0—a Versatile Platform for Genome Mining of Secondary Metabolite Producers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, W204–W212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.Y.; Lu, P.; Niu, Y.F. Preparation and Regeneration of Protoplasts Isolated from Embellisia Fungal Endophyte of Oxytropis Glabra. Biotechnol. Bull. 2015, 31, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Sarula, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Xi, L.J.; Lu, P.; Gao, F.; Du, L. The Influence of Different Additives on the Swainsonine Biosynthesis in Saccharopine Reductase Gene Disruption Mutant M1 of an Endophytic Fungus from Oxytropis Glabra. Life Sci. Res. 2018, 22, 298–304. [Google Scholar]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.C.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.Y.; He, Q.Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS: J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.D.; Wakefield, M.J.; Smyth, G.K.; Oshlack, A. Gene Ontology Analysis for RNA-Seq: Accounting for Selection Bias. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, B.; Yang, R.H. An Assessment of AcquireX and Compound Discoverer Software 3.3 for Non-Targeted Metabolomics. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreekumar, A.; Poisson, L.M.; Rajendiran, T.M.; Khan, A.P.; Cao, Q.; Yu, J.D.; Laxman, B.; Mehra, R.; Lonigro, R.J.; Li, Y.; et al. Metabolomic Profiles Delineate Potential Role for Sarcosine in Prostate Cancer Progression. Nature 2009, 457, 910–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haspel, J.A.; Chettimada, S.; Shaik, R.S.; Chu, J.H.; Raby, B.A.; Cernadas, M.; Carey, V.; Process, V.; Hunninghake, G.M.; Ifedigbo, E.; et al. Circadian Rhythm Reprogramming during Lung Inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Quan, H.Y.; Ren, Z.H.; Wang, S.; Xue, R.X.; Zhao, B.Y. The Genome of Undifilum Oxytropis Provides Insights into Swainsonine Biosynthesis and Locoism. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, R.L.; Mur, L.A.J.; Guo, C.C.; Zhao, X.; Meng, H.Z.; Yan, D.; Zhang, X.H.; Guan, H.R.; Han, G.D.; et al. Assembly of High-quality Genomes of the Locoweed Oxytropis Ochrocephala and Its Endophyte Alternaria Oxytropis Provides New Evidence for Their Symbiotic Relationship and Swainsonine Biosynthesis. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2023, 23, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, E.X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhu, Y.R.; Tang, S.Y.; Mo, C.H.; Zhao, B.Y.; Lu, H. Swnk Plays an Important Role in the Biosynthesis of Swainsonine in Metarhizium Anisopliae. Biotechnol. Lett. 2023, 45, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.F.; Tang, G.R.; Hong, S.; Gong, T.Y.; Xin, X.F.; Wang, CS. Promotion of Arabidopsis Immune Responses by a Rhizosphere Fungus via Supply of Pipecolic Acid to Plants and Selective Augment of Phytoalexins. Sci. China Life Sci. 2023, 66, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.X.; Liu, R.Y.; Lim, G.H.; De Lorenzo, L.; Yu, K.S.; Zhang, K.; Hunt, A.G.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. Pipecolic Acid Confers Systemic Immunity by Regulating Free Radicals. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaar4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.Q.; Dong, X.N. Systemic Acquired Resistance: Turning Local Infection into Global Defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 839–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

SW biosynthetic pathways in two fungi. (A)

R. leguminicola. (B)

M. robertsii. [

19,

26].

Figure 1.

SW biosynthetic pathways in two fungi. (A)

R. leguminicola. (B)

M. robertsii. [

19,

26].

Figure 2.

Overview of the whole genome of A. oxytropis OW 7.8. From the outside to the inside, the outermost circle represents the coordinates of the genome sequence positions. The second circle represents the genome GC content with the inward blue part indicating lower than the average GC content of the genome, the outward purple part indicating the opposite. The higher peaks indicate greater differences from the average GC content. The third circle represents GC skew value with inward green part indicating lower G content than the C content, the outward pink part indicating the opposite. The cycles from 4 to 7 represent gene densities of coding genes, rRNA, snRNA, and tRNA respectively, and the inner lines represent chromosomal duplications.

Figure 2.

Overview of the whole genome of A. oxytropis OW 7.8. From the outside to the inside, the outermost circle represents the coordinates of the genome sequence positions. The second circle represents the genome GC content with the inward blue part indicating lower than the average GC content of the genome, the outward purple part indicating the opposite. The higher peaks indicate greater differences from the average GC content. The third circle represents GC skew value with inward green part indicating lower G content than the C content, the outward pink part indicating the opposite. The cycles from 4 to 7 represent gene densities of coding genes, rRNA, snRNA, and tRNA respectively, and the inner lines represent chromosomal duplications.

Figure 3.

GO functional annotation of the A. oxytropis OW 7.8 genome.

Figure 3.

GO functional annotation of the A. oxytropis OW 7.8 genome.

Figure 4.

KEGG functional annotation of the A. oxytropis OW 7.8 genome.

Figure 4.

KEGG functional annotation of the A. oxytropis OW 7.8 genome.

Figure 5.

Bioinformatics analysis of the swnK gene. (A) Domain structure of SwnK mapped over the length of the gene. (B) Scale map of sequences cloned into the double crossover gene replacement construct (white), which flank the segment targeted for replacement. (C) Map of the ΔswnK-ACP mutation in which the target region is replaced with the hpt gene. Labeled arrows indicate primers used for PCR screens. (D,E) The predicted advanced structure of the SwnK protein: the red part represents the A domain, the orange part the T domain, the yellow part the KS domain, the green part the AT domain, the cyan part the KR domain, the blue part the ACP domain, and the purple part the R domain. (F) The phylogenetic tree of the SwnK protein.

Figure 5.

Bioinformatics analysis of the swnK gene. (A) Domain structure of SwnK mapped over the length of the gene. (B) Scale map of sequences cloned into the double crossover gene replacement construct (white), which flank the segment targeted for replacement. (C) Map of the ΔswnK-ACP mutation in which the target region is replaced with the hpt gene. Labeled arrows indicate primers used for PCR screens. (D,E) The predicted advanced structure of the SwnK protein: the red part represents the A domain, the orange part the T domain, the yellow part the KS domain, the green part the AT domain, the cyan part the KR domain, the blue part the ACP domain, and the purple part the R domain. (F) The phylogenetic tree of the SwnK protein.

Figure 6.

Construction of the swnK-ACP gene knockout vector. (A) PCR products of upstream and downstream homologous to the swnK-ACP and the hpt gene by electrophoresis: Marker: 1 kb plus DNA ladder. Lanes 1 and 2 show bands of the upstream homologous sequence of swnK-ACP, with the expected product being 885 bp; lanes 3 and 4 show bands of the hpt, with the expected product being 1376 bp; lanes 5 and 6 show bands of the downstream homologous sequence of swnK-ACP, with the expected product being 783 bp. (B) PCR products of the upper and lower arms to the swnK-ACP knockout cassette by electrophoresis: Marker: 1 kb plus DNA ladder. Lane 1 shows band of the upper arm of the knockout cassette, with the expected product being 2261 bp; Lane 2 shows the band of lower arm of the knockout cassette, with the expected product being 2159 bp. (C) PCR products of the swnK-ACP knockout cassette by electrophoresis: Marker: 500 bp DNA Ladder. Lanes 1 and 2 show bands of the knockout cassette, with the expected product being 3044 bp. (D) Diagram of the swnK-ACP gene knockout vector structure.

Figure 6.

Construction of the swnK-ACP gene knockout vector. (A) PCR products of upstream and downstream homologous to the swnK-ACP and the hpt gene by electrophoresis: Marker: 1 kb plus DNA ladder. Lanes 1 and 2 show bands of the upstream homologous sequence of swnK-ACP, with the expected product being 885 bp; lanes 3 and 4 show bands of the hpt, with the expected product being 1376 bp; lanes 5 and 6 show bands of the downstream homologous sequence of swnK-ACP, with the expected product being 783 bp. (B) PCR products of the upper and lower arms to the swnK-ACP knockout cassette by electrophoresis: Marker: 1 kb plus DNA ladder. Lane 1 shows band of the upper arm of the knockout cassette, with the expected product being 2261 bp; Lane 2 shows the band of lower arm of the knockout cassette, with the expected product being 2159 bp. (C) PCR products of the swnK-ACP knockout cassette by electrophoresis: Marker: 500 bp DNA Ladder. Lanes 1 and 2 show bands of the knockout cassette, with the expected product being 3044 bp. (D) Diagram of the swnK-ACP gene knockout vector structure.

Figure 7.

Colonies of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 on PDA media containing different concentrations of Hyg B after 30 days of incubation. (A) 0 μg/mL. (B) 0.7 μg/mL. (C) 0.8 μg/mL. (D) 0.9 μg/mL. (E) 1.0 μg/mL. (F) 2.0 μg/mL.

Figure 7.

Colonies of A. oxytropis OW 7.8 on PDA media containing different concentrations of Hyg B after 30 days of incubation. (A) 0 μg/mL. (B) 0.7 μg/mL. (C) 0.8 μg/mL. (D) 0.9 μg/mL. (E) 1.0 μg/mL. (F) 2.0 μg/mL.

Figure 8.

Electrophoresis analysis of PCR products of transformant DNA. Marker: 500 bp DNA Ladder. (A) Lane 1 shows band of the hpt gene, with the expected product being 1388 bp. (B) Lanes 1 and 2 show bands of the upstream homologous sequence of swnK-ACP + hpt gene, with the expected product being 2261 bp. (C) Lanes 1 and 2 show bands of the hpt gene + downstream homologous sequence of the swnK-ACP, with the expected product being 2159 bp.

Figure 8.

Electrophoresis analysis of PCR products of transformant DNA. Marker: 500 bp DNA Ladder. (A) Lane 1 shows band of the hpt gene, with the expected product being 1388 bp. (B) Lanes 1 and 2 show bands of the upstream homologous sequence of swnK-ACP + hpt gene, with the expected product being 2261 bp. (C) Lanes 1 and 2 show bands of the hpt gene + downstream homologous sequence of the swnK-ACP, with the expected product being 2159 bp.

Figure 9.

SW levels in mycelia from A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP.

Figure 9.

SW levels in mycelia from A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP.

Figure 10.

Transcriptome analysis between A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP. (A) Heatmap of DEGs clustering analysis between the two groups. (B) Volcano plot for differential comparison. (C) Bar chart of the number of DEGs. (D) KEGG enrichment analysis (E) GO functional classification annotation.

Figure 10.

Transcriptome analysis between A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP. (A) Heatmap of DEGs clustering analysis between the two groups. (B) Volcano plot for differential comparison. (C) Bar chart of the number of DEGs. (D) KEGG enrichment analysis (E) GO functional classification annotation.

Figure 11.

Metabolome analysis between A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP. (A) Principal component analysis in positive ion mode. (B) Principal component analysis in negative ion mode. (C) Pie chart of metabolite classification in positive ion mode. (D) Pie chart of metabolite classification in negative ion mode. (E) Heatmap of clustering analysis of DEMs in positive ion mode. (F) Heatmap of clustering analysis of DEMs in negative ion mode. (G) KEGG enrichment analysis of DEMs.

Figure 11.

Metabolome analysis between A. oxytropis OW 7.8 and ΔswnK-ACP. (A) Principal component analysis in positive ion mode. (B) Principal component analysis in negative ion mode. (C) Pie chart of metabolite classification in positive ion mode. (D) Pie chart of metabolite classification in negative ion mode. (E) Heatmap of clustering analysis of DEMs in positive ion mode. (F) Heatmap of clustering analysis of DEMs in negative ion mode. (G) KEGG enrichment analysis of DEMs.

Figure 12.

SW biosynthesis pathway in A. oxytropis OW 7.8. LysDH, LYS1, and LYS9: saccharopine reductases; lhpD/dpkA: delta-1-piperideine-2-carboxylate reductase; lhpI: 1-piperideine-2-carboxylate reductase; P5CR: pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase; PIPOX: pipecolic acid oxidase.

Figure 12.

SW biosynthesis pathway in A. oxytropis OW 7.8. LysDH, LYS1, and LYS9: saccharopine reductases; lhpD/dpkA: delta-1-piperideine-2-carboxylate reductase; lhpI: 1-piperideine-2-carboxylate reductase; P5CR: pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase; PIPOX: pipecolic acid oxidase.

Table 1.

Members of the SWN gene clusters and their predicted functions [

19,

20].

Table 1.

Members of the SWN gene clusters and their predicted functions [

19,

20].

| Gene |

Encoding product |

Function prediction |

| swnA |

Aminotransferase |

Catalyzing the synthesis of pyrroline-6-carboxylate (P6C) from L-lysine |

| swnR |

Dehydrogenase or reductase |

Catalyzing the synthesis of L-PA from P6C |

| swnK |

Multifunctional protein |

Catalyzing the synthesis of 1-oxoindolizidine (or 1-hydroxyindolizine) from L-PA |

| swnN |

Dehydrogenase or reductase |

Catalyzing the synthesis of 1-hydroxyindolizine from 1-oxoindolizidine |

| swnH1 |

Fe(II)/α-Ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase |

Catalyzing the synthesis of SW from 1,2-dihydroxyindolizine |

| swnH2 |

Fe(II)/α-Ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase |

Catalyzing the synthesis of 1,2-dihydroxyindolizine form 1-hydroxyindolizine |

| swnT |

Transmembrane transporter |

Transport of SW |

Table 2.

Predicted functions of SwnK protein domains [

19,

20].

Table 2.

Predicted functions of SwnK protein domains [

19,

20].

| Domain |

Function prediction |

Specific functions |

| A |

Adenylation |

Adenylation of L-PA to facilitate anchoring to the T domain |

| T |

Phosphopantetheinylation |

Phosphopantetheinylation anchoring of L-PA |

| KS |

β-Ketoacyl Synthase |

Catalyzing the condensation of the piperidinyl group bound to the T domain with the acetyl group bound to the ACP domain |

| AT |

Acyltransferase |

Catalyzing the binding of malonyl-CoA to the ACP domain |

| KR |

β-Ketoacyl Reductase |

Catalyzing the reduction of the keto group of the piperidinyl-acetyl-ACP compound to a hydroxyl group |

| ACP |

Acyl Carrier Protein |

After binding with malonyl-CoA, it condenses with the piperidinyl group attached to the T domain |

| R |

Reductase |

Catalyzing the reduction of the thioester bond to release the intermediate aldehyde |

Table 3.

Statistics of genome sequencing results for A. oxytropis OW 7.8.

Table 3.

Statistics of genome sequencing results for A. oxytropis OW 7.8.

| Categories |

Data |

| Sequencing |

|

| Number of Bases(bp) |

6,940,798,828 |

| Average Read Length(bp) |

3,215 |

| N50 Read Length(bp) |

4,057 |

| Genome assembly |

|

| Genome Size(bp) |

76,087,302 |

| Contig Max Length(bp) |

3,106,266 |

| Contig N50 Length(bp) |

712,767 |

| GC Content of genome(%) |

39.86 |

| Annotation |

|

| Gene Number |

7,985 |

| Gene Length(bp) |

10,928,077 |

| Gene Average Length(bp) |

1,369 |

Table 4.

Screening of DEMs.

Table 4.

Screening of DEMs.

| Screening mode |

Total of metabolites |

Total of DEMs |

Up-regulated |

Down-regulated |

| Positive |

751 |

345 |

203 |

142 |

| Negative |

366 |

175 |

63 |

112 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).