Submitted:

16 August 2024

Posted:

16 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rhizosphere Soil Samples Collection

2.2. Isolation and Identification of Fungi

2.3. Fermentation and Extraction

2.4. Antibacterial Bioassay

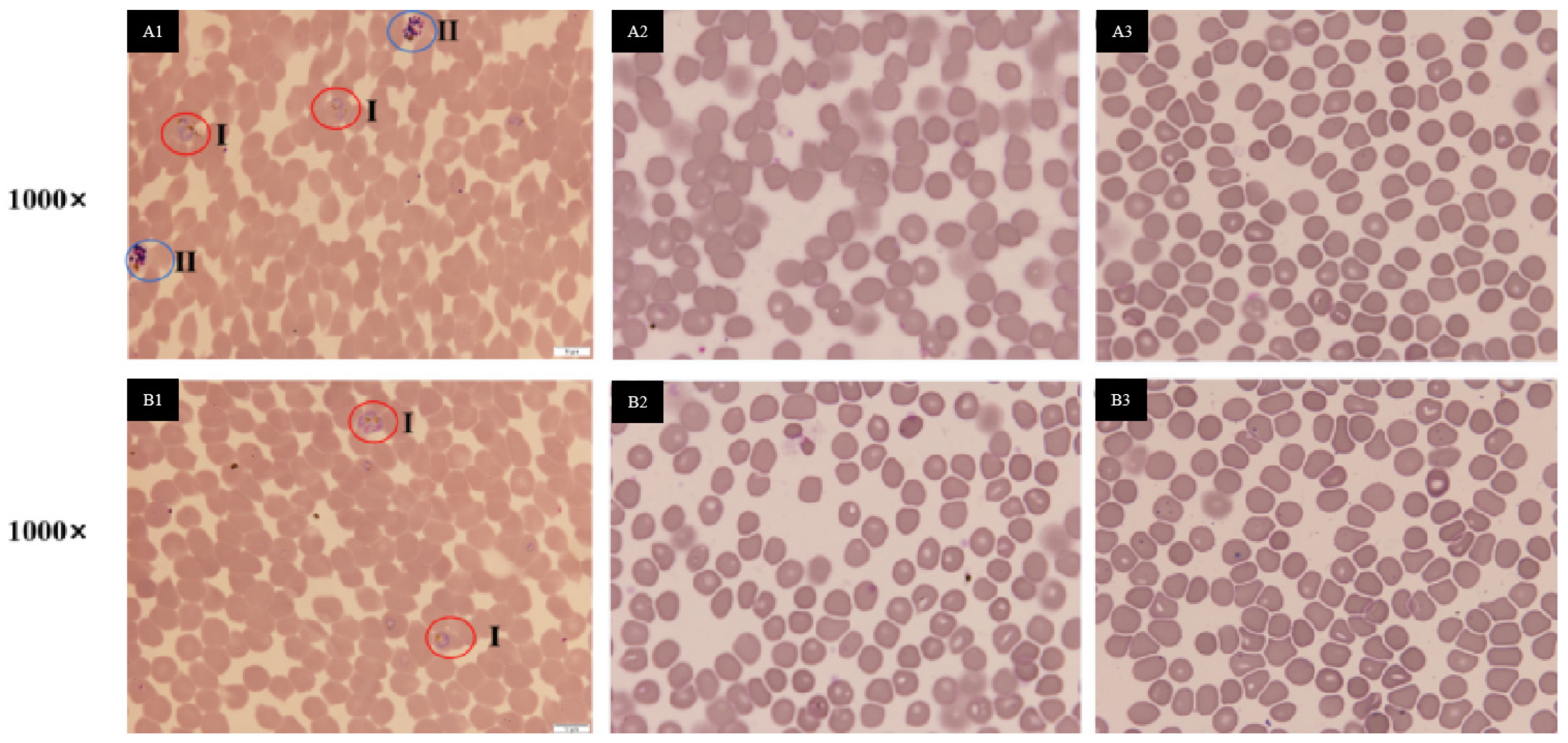

2.5. Antimalarial Bioassay (In Vitro)

2.6. Isolation and Structural Elucidation of Secondary Metabolites from Aspergillus calidoustus AA12

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopic (SEM) Observation

2.8. Nucleotide Sequence Accession Number

3. Results

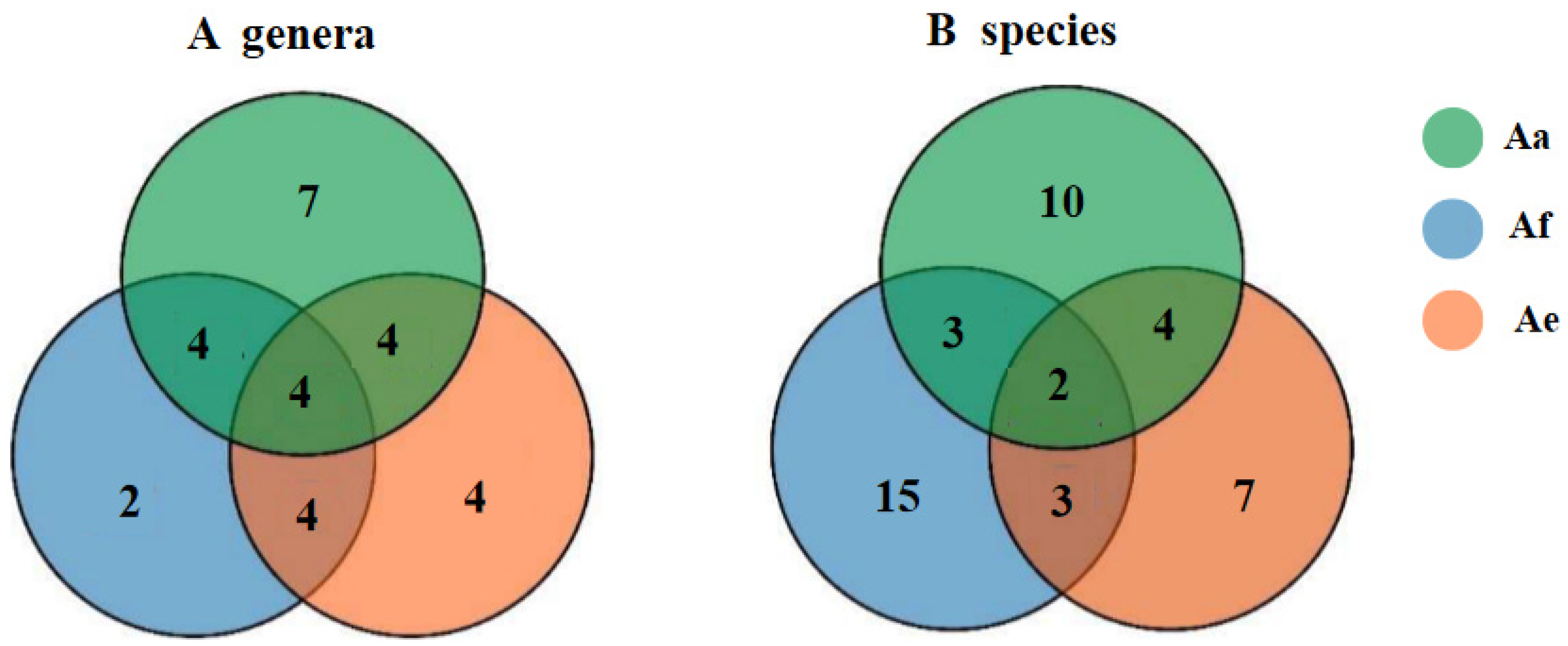

3.1. Diversity of Cultivable Fungi in the Rhizosphere Communities of Three Species of Astragalus Plants

3.2. Anti-Infectious Potential of Isolated Fungi

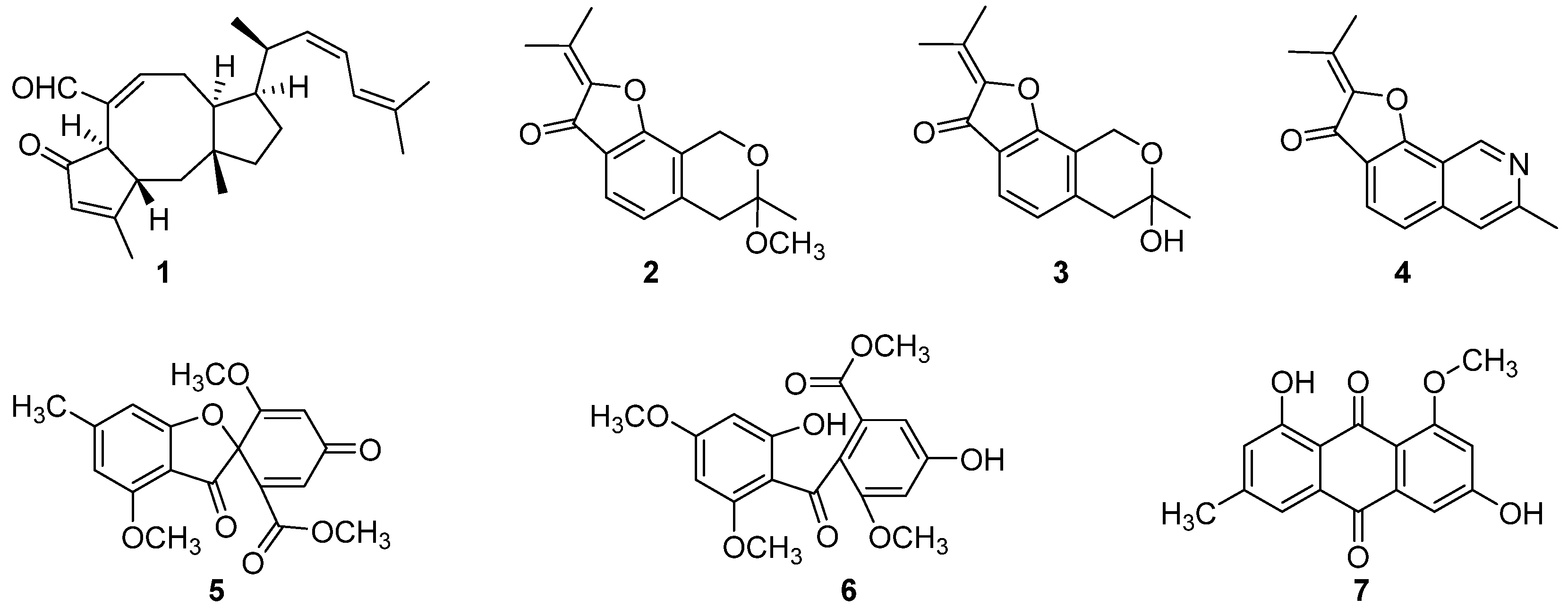

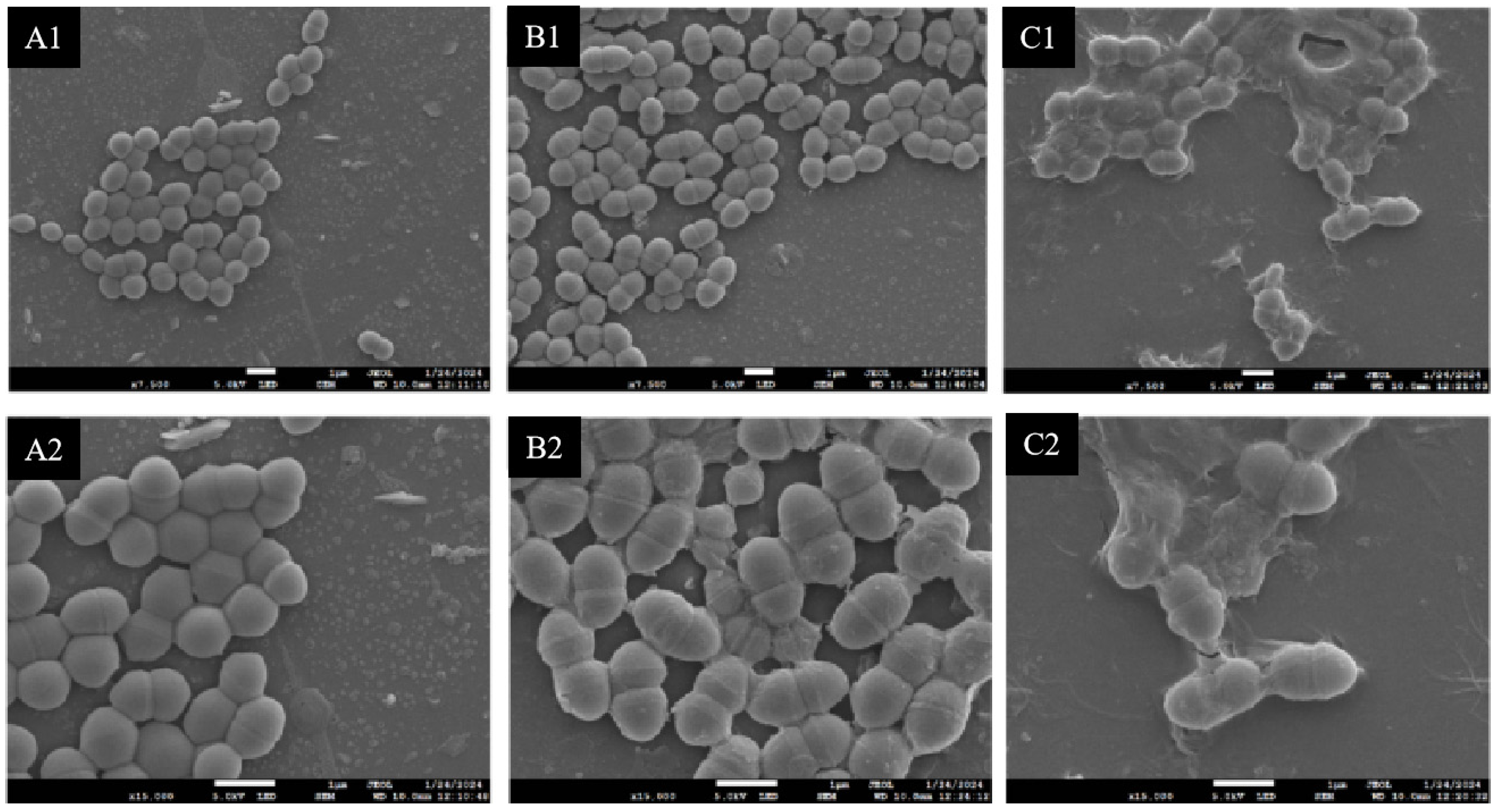

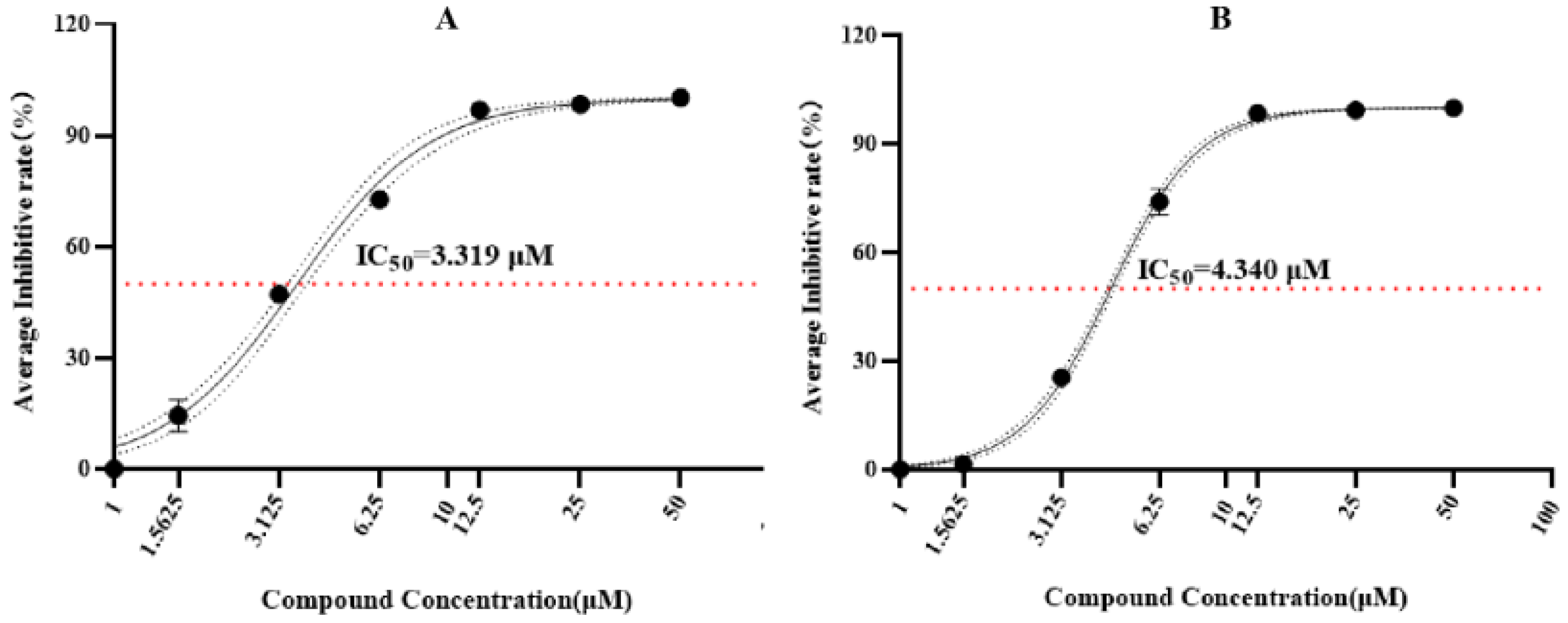

3.3. Structural Elucidation and Anti-Infective Activity of the Isolated Natural Products

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Philippot, L.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Lemanceau, P.; van der Putten, W.H. Going back to the roots: the microbial ecology of the rhizosphere. Nat Rev Microbiol 2013, 11, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zeng, J.; Wan, X.; Wang, Y.; Lan, S.; Zou, S.; Qian, X. Variation in community structure of the root-associated fungi of Cinnamomum camphora forest. J Fungi 2022, 8, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Yang, W.; Wang, R.; Zhang, H.; Meng, J.; Jing, H.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J.; Guo, L.; Gao, W. ZnO-S.cerevisiae: an effective growth promoter of Astragalus memeranaceus and nano-antifungal agent against Fusarium oxysporum. Chem Eng J 2024, 486, 149958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, F.X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, M.; Sun, F.; Yang, L.; Bi, X.; Lin, Y.; Gao, Y.; Hao, H.X.; Yi, W.; Li, M.; Xie, Y. Advances in metagenomics and its application in environmental microorganisms. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 766364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaborators, A.R. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019; Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; Ouellette, M.; Outterson, K.; Patel, J.; Cavaleri, M.; Cox, E.M.; Houchens, C.R.; Grayson, M.L.; Hansen, P.; Singh, N.; Theuretzbacher, U.; Magrini, N. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, F.; Zeng, Y. Novel bioactive natural products from marine-derived Penicillium fungi: A Review (2021-2023). Mar Drugs 2024, 22, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.L.; Dou, Z.R.; Gong, G.F; Li, H.F.; Jiang, B.; Xu, Y. Anti-larval and anti-algal natural products from marine microorganisms as sources of anti-biofilm agents. Mar Drugs 2022, 20, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ji, G.; Cun, J.; Xu, P.; Wang, X.; Ren, G.; Li, W. Screening of insecticidal and antifungal activities of the culturable fungi isolated from the intertidal zones of Qingdao, China. J Fungi 2022, 8, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yu, H.; Ren, J.; Cai, L.; Xu, L.; Liu, L. Sulfoxide-containing bisabolane sesquiterpenoids with antimicrobial and nematicidal activities from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus sydowii LW09. J Fungi 2023, 9, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, L.; Gao, C.; Chen, W.; Vong, C.; Yao, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Astragali Radix (Huangqi): a promising edible immunomodulatory herbal medicine. J Ethnopharmacol 2020, 258, 112895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.J.; Zhou, G.J.; Chen, X.J.; Xu, W.; Gao, X.M.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Jiang, B.; Li, H.F.; Wang, K.L. Analysis of microbial diversity and community structure of rhizosphere soil of three Astragalus species grown in special high-cold environment of northwestern Yunnan, China. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, Z.R.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, G.J.; Gong, G.F.; Ding, J.J.; Fan, X.H.; Jiang, B.; Wang, K.L. Varicosporellopsis shangrilaensis sp. nov. (Nectriaceae, Hypocreales), a new terricolous species isolated from the rhizosphere soil of Astragalus polycladus in northwestern Yunnan. Phytotaxa, 2023; 600, 230–238. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, J.; Li, Y.; Lei, Y.; Sun, Y. Analysis of microbial diversity and community structure of rhizosphere soil of Cistanche salsa from different host plants. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 971228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.M.; Zhang, J.L.; Zhou, K.; Yue, L.M; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.Y.; Wang, K.L.; Xu, Y. Anthraquinones as potential antibiofilm agents against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 709826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudla, C.S.; Selvam, V.; Selvaraj, S.S.; Tripathi, R.; Joshi, P.; Shaham, S.H.; Singh, M.; Shandil, R.K.; Habib, S.; Narayanan, S. Novel baicalein-derived inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Liang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Z.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y. Butenolide, a marine derived broad-spectrum antibiofilm agent against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria. Mar Biotechnol 2019, 21: 88–98.

- Krijgsheld, P.; Bleichrodt, R.; Veluw, G.J.; Wang, F.; Müller, W.H.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Wösten, H.A.B. Development in Aspergillus. Stud Mycol 2012, 74, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, F.T.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Jeffries, T.C.; Eldridge, D.J.; Ochoa, V.; Gozaloa, B.; Quero, J.L.; García-Gómez, M.; Gallardof, A.; Ulrichg, W.; Bowkerh, M.A.; Arredondoi, T.; Barraza-Zepedaj, C.; Brank, D.; Florentinol, A.; Gaitánm, J; Gutiérrezj, J.R.; Huber-Sannwaldi, E.; Jankjup, M.; Mauq, R.L.; Miritir, M.; Naserip, K.; Ospinal, A.; Stavis, I.; Wangt, D.; Woodsr, N.N.; Yuant, X.; Zaadyu, E.; Brajesh K. Singhb, BK. Increasing aridity reduces soil microbial diversity and abundance in global drylands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015, 112, 15684–15689.

- Zhao, D.L.; Han, X.B.; Wang, M.; Zeng, Y.T.; Li, Y.Q.; Ma, G.Y.; Liu, J.; Zheng, C.J.; Wen, M.X.; Zhang, Z.F; Zhang, P.; Zhang, C.S. Herbicidal and antifungal xanthone derivatives from the alga-derived fungus Aspergillus versicolor D5. J Agric Food Chem 2020, 68, 11207–11214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Mei, J.; Jiang, R.; Tu, S.; Deng, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Li, J. Origins, structures, and bioactivities of secondary metabolites from marine-derived Penicillium fungi. Mini Rev Med Chem 2021, 21, 2000–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.H.; Pu-BU, R.C.; Lv, M.L.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.Y. Species diversity of Zygomycotan fungi in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Microbiology China 2018, 45, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, M.L.; Liu, Z.; Song, Z.; Wang, Y.N.; Liu, X.Y. Diversity and distribution of culturable Mucoromycota fungi in the Greater Khinggan Mountains, China. Biodiversity Science 2019, 27, 821–837. [Google Scholar]

- Minnis, A.M.; Lindner, D.L. Phylogenetic evaluation of geomyces and allies reveals no close relatives of Pseudogymnoascus destructans, comb. nov., in bat hibernacula of eastern North America. Fungal Biol 2013, 117, 638–649.

- Meng, Y,; Tang, H. Y.; Shi, J.D.; Wang, D. Three fungal strains isolated from stroma of Ophiocordyceps sinensis and their culture conditions. Mycosystema 2021, 40, 1991–2007.

- Zhang, L.L. Species diversity and drought resistance of dark septate endophytes in the rhizospheres of different plants in Anxi extreme arid desert. Master’s dissertation, Hebei university, Hebei, Baoding, June 9, 2018.

- Varga, J.; Houbraken, J.; Van-Der-Lee, H.A.; Verweij, P.E.; Samson, R.A. Aspergillus calidoustus sp. nov., causative agent of human infections previously assigned to Aspergillus ustus. Eukaryot Cell 2008, 7, 630–638.

- Valiante, V.; Mattern, D.J.; Schüffler, A.; Horn, F.; Walther, G.; Scherlach, K.; Petzke, L.; Dickhaut, J.; Guthke, R.; Hertweck, C.; Nett, M.; Thines, E.; Brakhage, A.A. Discovery of an extended austinoid biosynthetic pathway in Aspergillus calidoustus. ACS Chem Biol 2017, 12, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, S.; Yin, J.; Ye, Z.; Li, F.; Lin, S.; Zhang, S.; Yang, B.; Yao, J.; Wang, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Asperanstinoids A-E: undescribed 3,5-dimethylorsellinic acid-based meroterpenoids from Aspergillus calidoustus. Phytochemistry 2021, 190, 112892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Mo, S.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Drimane sesquiterpenoids from a wetland soil-derived fungus Aspergillus calidoustus TJ403-EL05. Nat Prod Bioprospect 2022, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.L.; Chen, C.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Gao, C.H.; Wang, R.P.; Zhang, W.F.; Bai, M. Austin-Type Meroterpenoids from fungi reported in the last five decades: a review. J Fungi 2024, 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, W.; Uvarani, C.; Wang, F.; Xue, Y.; Wu, N.; He, L.; Tian, D.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hong. K.; Tang, J. New Ophiobolins from the deep-sea derived fungus Aspergillus sp. WHU0154 and their anti-inflammatory effects. Mar Drugs 2020, 18, 575.

- Trisuwan, K, Rukachaisiriku, V.; Sukpondma, Y.; Phongpaichit, S.; Preedanon, S.; Sakayaroj, J. Furo[3,2-h]isochroman, furo[3,2-h]isoquinoline, isochroman, phenol, pyranone,and pyrone derivatives from the sea fan-derived fungus Penicillium sp. PSU-F40. Tetrahedron 2010, 4484–4489.

- Kuramochi, K.; Tsubaki, K. Synthesis and structural characterization of natural benzofuranoids. J Nat Prod 2015, 78, 1056–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, A.; Murakami, C.; Kamisuki, S.; Kuriyama, I.; Yoshida, H.; Sugawara, F.; Mizushina, Y. Pseudodeflectusin, a novel isochroman derivative from Aspergillus pseudodeflectus a parasite of the sea weed, Sargassum fusiform, as a selective human cancer cytotoxin. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2004, 14, 3539–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Guo, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Guo, L. Bioassay-guided isolation and characterization of antibacterial compound from Aspergillus fumigatus HX-1 associated with Clam. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newaz, A.W.; Yong, K.; Yi, W.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Z. Antimicrobial metabolites from the indonesian mangrove sediment-derived fungus Penicillium chrysogenum sp. ZZ1151. Nat Prod Res 2023, 37, 1702–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Xu, X.; Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, W.; Xu, F.; Li, F. Enhanced production of questin by marine-derived Aspergillus flavipes HN4-13. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paveenkittiporn, W.; Ungcharoen, R.; Kerdsin, A. Streptococcus agalactiae infections and clinical relevance in adults, Thailand. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2020, 97, 15005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Moreno, M.; Trampuz, A.; Di-Luca, M. Synergistic antibiotic activity against planktonic and biofilm-embedded Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus oralis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017, 72, 3085–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.H.; Miao, F.P.; Ming-Feng Qiao, M.F.; Robert, H.; Ji, N.Y. Terretonin, ophiobolin, and drimane terpenes with absolute configurations from an algiconus Aspergillus ustus. RSC Advances 2013, 3, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, M.; Niikawa, H.; Kobayashi, M. Marine-derived fungal sesterterpenes, ophiobolins, inhibit biofilm formation of Mycobacterium species. J Nat Med 2013, 67, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Jiang, H.; Mo, Y.; Guo, H.; Li, C.; Long, Y.; Zang, Z.; She, Z. Ophiobolin-type sesterterpenoids from the mangrove endophytic fungus Aspergillus sp. ZJ-68. J Nat Prod. 2019, 82, 2268–2278.

- Wei, H.; Itoh, T.; Kinoshita, M.; Nakai, Y.; Kurotaki, M.; Kobayashi, M. Cytotoxic sesterterpenes, 6-epi-ophiobolin G and 6-epi-ophiobolin N, from marine derived fungus Emericella variecolor GF10. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 6015–6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Representative Isolates (Accession Number in GenBank |

Similarity | Number of Fungal Isolates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aa | Af | Ae | |||

| Penicillium wellingtonense | AA3(JN617713) | 100.00% | 2 | ||

| P. polonicum | AA17(OK510248) | 99.19% | 1 | 2 | |

| P. glabrum | AE3-1(OP179016) | 99.49% | 1 | 2 | |

| brevicompactum | AE7(MT558924) | 100.00% | 1 | ||

| P. vasconiae | AF5(OQ870819) | 98.86% | 8 | ||

| P. suaveolens | AF6(MH864249) | 99.48% | 1 | ||

| P. thomii | AF19(OR574374) | 99.58% | 1 | ||

| Aspergillus calidoustus | AA12(MZ267040) | 100.00% | 3 | ||

| A. fumigatus | AA15(MG991598) | 100.00% | 2 | 9 | 2 |

| A. niger | AE10(OM841707) | 99.74% | 1 | ||

| A. versicolor | AF2-1(MT582751) | 100.00% | 1 | ||

| A. tabacinus | AF16(OK011797) | 98.68% | 2 | ||

| Mortierella alpina | AA10(MT366045) | 100.00% | 8 | 2 | 3 |

| M.clonocystis | AA2(LC515184) | 100.00% | 3 | ||

| M. minutissima | AF9(MT072066) | 98.93% | 1 | ||

| M. verticillata | AF20(MT028128) | 99.50% | 1 | ||

| Truncatella angustata | AA1-1(MT514384) | 100.00% | 3 | ||

| Cordyceps farinosa | AA8(MF494607) | 99.82% | 3 | ||

| Exophiala tremulae | AA21(NR159874) | 98.84% | 1 | ||

| Beauveria pseudobassiana | AA4-1(KT368174) | 100/00% | 1 | ||

| Samsoniella hepiali | AA16(OL684609) | 98.91% | 2 | ||

| Cladosporium cladosporioides | AA2-1(ON970159) | 100.00% | 1 | 2 | |

| Neonectria radicicola | AA1(AJ875331) | 100.00% | 1 | ||

| Trichoderma atroviride | AA14(KX379158) | 99.63% | 1 | 3 | |

| T. paraviridescens | AF8(MN900599) | 100.00% | 1 | ||

| T. koningiopsis | AF23(KU645324) | 99.83% | 2 | ||

| T. viride | AF29(KU202222) | 98.71% | 1 | ||

| T. longipile | AF30(AY737763) | 100.00% | 2 | ||

| longibrachiatum | AE8(KU945846) | 99.71% | 1 | ||

| Pseudogymnoascus roseus | AA4(KJ755524) | 100.00% | 2 | ||

| Leptosphaeria sclerotioides | AE3(OR782803) | 99.76% | 2 | ||

| Fusarium solani | AE4-1(KT192216) | 98.98% | 1 | ||

| Nemania diffusa | AE4(MK336457) | 99.21% | 1 | ||

| Aporospora terricola | AE1(KC292841) | 98.47% | 1 | ||

| Lecanicillium aphanocladii | AF15(OR752316) | 99.32% | 1 | ||

| Umbelopsis vinacea | AF14(KT354998) | 99.34% | 1 | ||

| U. ramanniana | AF26 (GU934569) | 98.21% | 1 | ||

| U. nana | AF31(OR724064) | 100.00% | 1 | ||

| Fungal Strain | ATCC 43300 | ATCC 25923 | ATCC 12228 | ATCC 51299 | ATCC 29212 | ATCC 35667 | ATCC 13813 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus calidoustus AA12 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 6.25 | 12.5 | 25 |

| A. fumigatus AA15 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 25 |

| A. tabacinus AF16 | 50 | 25 | 25 | - | - | - | 50 |

| Penicillium glabrum AE3-1 | 50 | 50 | 12.5 | - | - | - | 50 |

| P. polonicum AA17 | 50 | 50 | 50 | - | - | - | 50 |

| P. brevicompactum AE7 | 10 | 50 | 25 | - | - | - | 50 |

| P. vasconiae AF5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 50 |

| Cordyceps farinosa AA8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | - | - | - | 50 |

| Lecanicillium aphanocladii AF15 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | - | 50 |

| Umbelopsis nana AF31 | 50 | 50 | 25 | 50 | 50 | - | 50 |

| Positive control: vancomycin | 2 | 2 | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Fungal strain | Test concentration (µg/mL) | Inhibitory rates (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus calidoustus AA12 | 100 | 99.78 |

| 50 | 99.60 | |

| A. fumigatus AA15 | 100 | 81.81 |

| 50 | 14.31 | |

| A. tabacinus AF16 | 100 | 95.60 |

| 50 | 91.19 | |

| Penicillium glabrum AE3-1 | 100 | 29.57 |

| 50 | 0.93 | |

| P. polonicum AA17 | 100 | -51.88 |

| 50 | -32.53 | |

| P. brevicompactum AE7 | 100 | 87/95 |

| 50 | 81.91 | |

| Cordyceps farinosa AA8 | 100 | -45.30 |

| 50 | -15.46 | |

| Positive control: chloroquine | 0.16 | 99.88 |

| Compounds | ATCC 43300 | ATCC 25923 | ATCC 12228 | ATCC 51299 | ATCC 29212 | ATCC 35667 | ATCC 13813 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | 12.25 | 12.5 | 50 | 12.5 | 25 | 6.25 |

| 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 80 |

| 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 80 |

| 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 50 |

| 5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 100 |

| 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 7 | 100 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Vancomycin | 2 | 2 | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).