1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was the most significant public health concern faced in this century, with millions of cases and deaths reported that overwhelmed the health system all over the world.[

1] Lethality from COVID-19 is higher in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and, especially in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs).[

2,

3] Despite the overall reduction in lethality after the Omicron variant circulation, this disadvantage remained among KTRs.[

4] Yet, CKD patients experience immune system dysfunction due to T and B lymphocyte inhibition, reducing the immune response to vaccines, which is progressively lower according to the CKD stage than the general population.[

5,

6] This effect is further exacerbated in solid organ transplant recipients by continued use of immunosuppressive drugs.[

7]

Long-term immunosuppression used in kidney transplantation is a predictor of lower immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, an effect also known with other vaccines, such as those against hepatitis B, Influenza, and Pneumococcus.[

7,

8,

9,

10] However, few data evaluated the effect of

de novo immunosuppression on the kinetics of immune response after SARS-CoV-2 immunization in CKD patients undergoing kidney transplantation.

This study evaluated the impact of de novo immunosuppression prescribed for CKD patients receiving a kidney transplant over the kinetics of the humoral immune response generated by SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in seroconverted individuals without previously COVID-19 over 12 months of follow-up.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This is a prospective, non-randomized, real-world study evaluating the effect of the immunosuppression prescribed to de novo KTRs in the kinetics of the humoral immune response assessed by the seroreversion rate of SARS-CoV-2 IgG, IgG titers and neutralizing antibodies in fully vaccinated patients who had never been diagnosed with COVID-19 compared to CKD patients remaining on dialysis.

We included fully vaccinated and seroconverted stage 5 CKD patients or those on dialysis who had never been diagnosed with COVID-19. All patients were on the waiting list for kidney transplantation, and both groups were included simultaneously during the study period. The patients called for transplantation were included in the transplant group, and those who remained on dialysis were included in the dialysis group (

Figure S1). We included patients undergoing living or deceased donor kidney transplantation. We excluded patients with negative SARS-CoV-2 IgG on inclusion, patients living with HIV, and those currently undergoing cancer treatment.

The eligible population signed an informed consent form. The study was conducted in compliance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee. All patients were followed up to 12 months from the date of inclusion and had a blood sample collected shortly after enrollment and then at months 1, 3, 6, and 12 for SARS-CoV-2 for immunological analysis. In the transplant group, the first blood sample was collected before receiving any immunosuppression.

This study did not propose any intervention in the routine prescription of immunosuppressive drugs used in transplantation. This study did not indicate or contraindicate vaccination, nor did it guide on the ideal time for additional booster doses. All patients received doses of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 through the public health system and followed the recommendations of the Ministry of Health. Our center performed all kidney transplants and followed up all dialysis patients in this study.

2.2. Primary Endpoint

The primary endpoint was the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 IgG seroreversion in patients undergoing kidney transplantation and those remaining on dialysis during 12 months of follow-up. Intermediate endpoints were evaluated after 1, 3 and 6 months. Seroreversion was defined as the absence of detection of specific antibodies in individuals with prior documentation of the presence of these antibodies.[

11]

2.3. Secondary Endpoints

The secondary endpoints included (1) kinetics of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG titers; (2) kinetics of anti-SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies rates; (3) incidence of COVID-19, death, and hospitalization; and (4) number, type, and time of additional vaccine doses. These outcomes were evaluated and compared between the groups at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months.

2.4. Immunogenicity Assessment

For the assessment of IgG antibodies against the S1, S2 and RBD peptides of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein, we used the AdviseDx SARS-CoV-2 IgG II test (Abbott Laboratories; lower limit of positivity 50 AU/mL).[

12] For neutralizing activity of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, we used the cPass™ SARS-CoV-2 test (GenScript Laboratory; positivity limit 30%).[

13]

2.5. Vaccines and Vaccination Strategy

The National Immunization Program organized the acquisition, storage, distribution, and application of millions of doses of vaccines, prioritizing the most vulnerable populations according to criteria of age and presence of comorbidities. The CKD patients and KTRs have been on the priority list for receiving booster vaccine doses since May 2021. This program had approved immunization with four vaccines at the time of inclusion of this study: (1) CoronaVac, an inactive whole-virus vaccine, applied in two shots four weeks apart; (2) ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, a non-human adenovirus vector vaccine, applied in two doses four to twelve weeks apart; (3) BNT162b2, a m-RNA-based vaccine, applied in two doses twelve weeks apart; (4) Ad26.COV2.S, a non-human adenovirus vector vaccine, is applied in a single dose as the primary immunization schedule.[

14]

2.6. Immunosuppressive Therapy

According to the routine institutional protocol, all kidney transplant recipients receive intravenous induction therapy with methylprednisolone 1g intraoperatively and a 3 mg/kg single-dose of rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (rATG) on the first postoperative day. This study did not propose intervention or change in the immunosuppressive regimen. Maintenance therapy consists of prednisone, tacrolimus, and a third drug (mycophenolate sodium, azathioprine, sirolimus, or everolimus) prescribed according to donor characteristics and recipient immunological risk.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For the primary endpoint, the sample size was calculated based on an assumed 16% difference in the incidence of seroreversion between groups during one year of follow-up. Based on data from interim analyses of effectiveness and immunogenicity studies with the CoronaVac vaccine in KTRs performed at our center, we considered an estimated seroreversion rate of 21% for the transplant group and 5% for the dialysis group.[

15] Assuming that difference, a 90% power, and a two-tailed significance margin of 5%, the calculated number of patients for each group was 91. Considering a dropout rate of 20%, the final sample size was 114 patients per group, 228 in total.

Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Numerical variables were evaluated for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Quantitative variables were presented as a median and interquartile range for non-parametric variables and as a mean and standard deviation for parametric variables. Differences between groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test.

For the primary outcome, due to the reduced incidence of seroreversion, the analyses within each group and between the groups at each study visit were performed using Cochran’s Q test and Fisher’s exact test, respectively. We used a linear regression model adjusted by random effects to evaluate the group effect on anti-SARS-CoV IgG titers over time.[

16] We used a logistic model adjusted by random effects for the neutralizing antibodies. Due to the small number of negative and indeterminate results, neutralizing antibody data were dichotomized into positive and non-positive. The regression model adjusted by random effects incorporates the effect of each patient in the form of a random effect, accommodating a possible dependence between the observations of the same patient evaluated on different occasions. The linear model adjusted by random effects assumes normality in the data. However, Gelman and Hill pointed out that escaping normality does not lead to bias in the estimates.[

17] Ad hoc Wald tests were performed with Bonferroni correction to maintain the global significance level.

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package SPSS version 29 (IBM Corp. Released 2022. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) and STATA 17 (StataCorp. 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC). We considered a p<0.05 as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

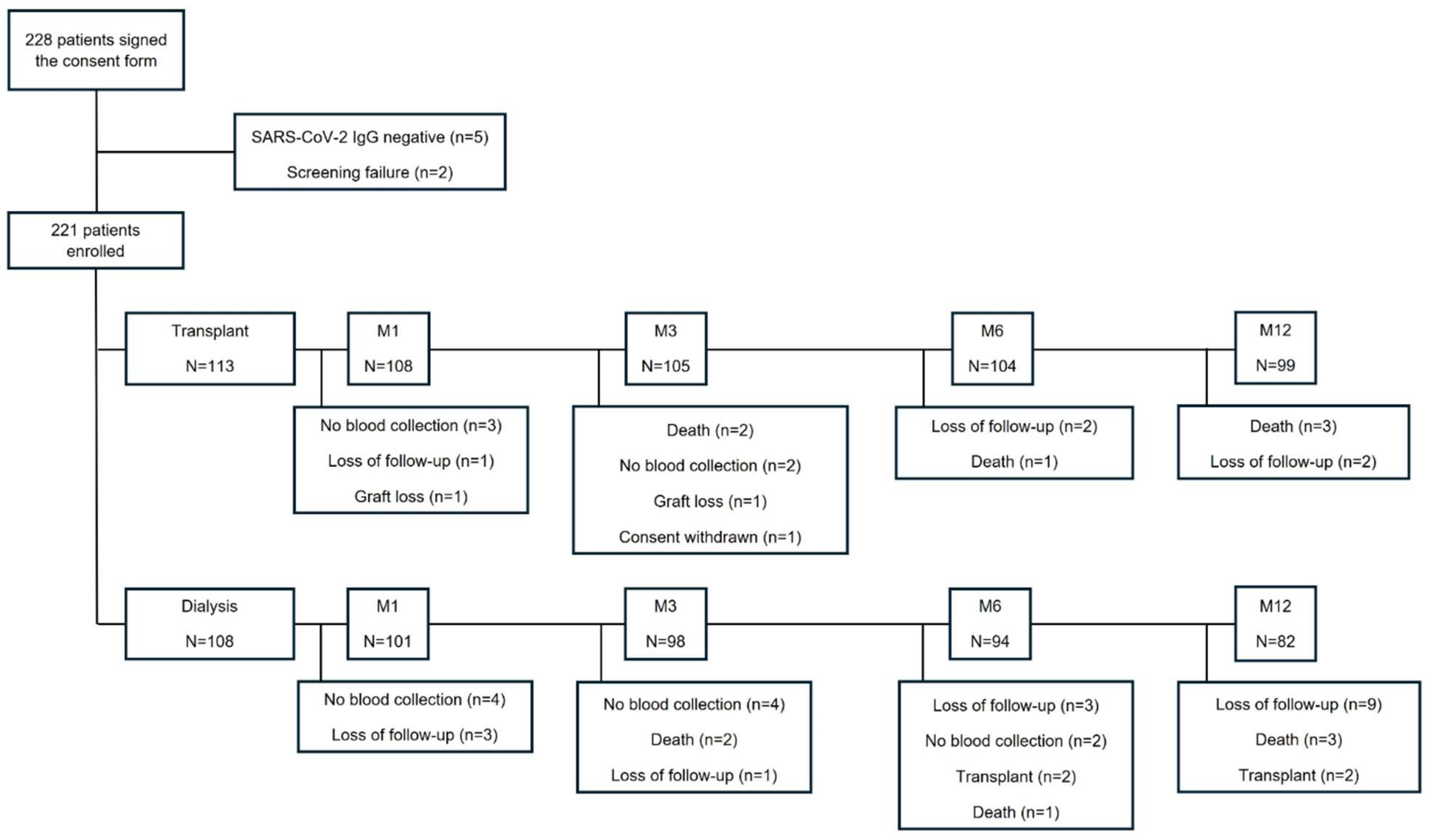

Between December, 13 2021 and July, 3 2022, 228 patients were enrolled. Five patients were excluded due to negative anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG, and two patients were excluded due to screening failure, resulting in 221 patients, 113 of whom were in the transplant group and 108 in the dialysis group.

Figure 1 summarizes the detailed flowchart of the study population. The Omicron variant was the dominant virus in circulation throughout the study period.

In baseline characteristics, the median age (45.4 vs. 54.0 years; p<0.001) and time on dialysis (25.1 vs. 51.9 months; p<0.001) were higher in the dialysis group. Hemodialysis was the predominant renal replacement therapy modality. The other baseline characteristics were similar in both groups (

Table 1).

The transplant group had two mismatches in HLA A, B, and DR loci, 18.6% presented detectable panel reactive antibodies (PRA), 80.5% received a deceased donor kidney transplant (39.6% were expanded criteria kidneys), with a median KDPI of 56% and a median cold ischemia time (CIT) of 22.7 hours (

Table S1). In this group, all patients received a 3 mg/kg single dose of rATG and maintenance therapy with prednisone and tacrolimus. Yet, 58.4% received mycophenolate as maintenance therapy, followed by 39.8% receiving azathioprine and 1.8% an mTOR inhibitor (

Table 1).

3.2. Primary Endpoint

For this analysis, we excluded 12 patients with the outcome of death. SARS-CoV-2 IgG seroreversion occurred in one KTR on M1 and in three dialysis patients on M1, M3, and M6. All patients finished the 12-month follow-up with IgG positive. Over time, no difference in the incidence of seroreversion was observed within each group (transplant, p=0.406; dialysis, p=0.663) or between the groups at each study visit (

Table 2).

3.3. Secondary Endpoints

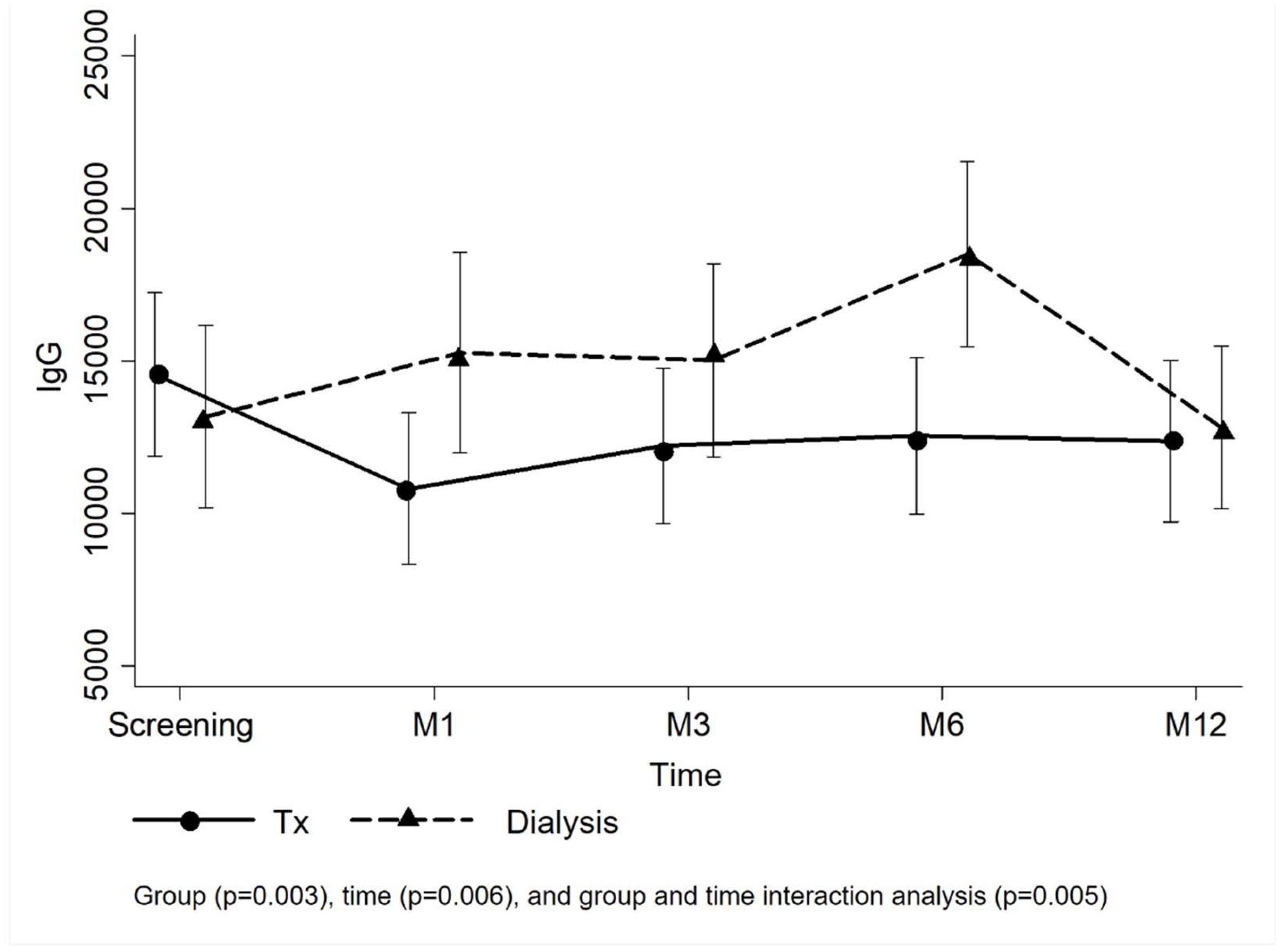

Figure 2 presents the means and confidence interval of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG titers per group. Analyzing the group and time effect of the entire study population, the KTRs had lower IgG titers than the dialysis group over time (p=0.005). In the transplant group, the mean IgG titer reduced from 14,554.2±13,972.9 IU/mL at the screening to 10,809.3±12,621.7 IU/mL at M1 visit and remained similar at the following visits (M3: 12,215.5±12,885.8 IU/mL; M6: 12,540.4±13,010.7 IU/mL; M12: 12,369.1±13,189.9 IU/mL), but IgG titers were not affected by time effect during the follow-up (p=0.148). In the dialysis group, however, the mean IgG titer at M6 (18,503.5±14,581.0 IU/mL) was superior to those at screening (13,164.0±15,174.7 IU/mL) and M12 visits (12,818.2±12,171.6 IU/mL) (p=0.005). Comparing the groups at each visit, IgG titers from patients on dialysis were higher at M1 and M6 (

Figure 2;

Table S2). The linear model adjusted by random effects (number of vaccine doses at screening) confirmed higher mean IgG titers in the dialysis group at M1 and M6 (

Table 3).

We compared the seroreversion incidence between the groups in each study visit using Fisher’s exact test – M1: p=1.000; M3: p=0.479; M6: p=0.474; M12: no event.

3.4. Neutralizing Antibodies

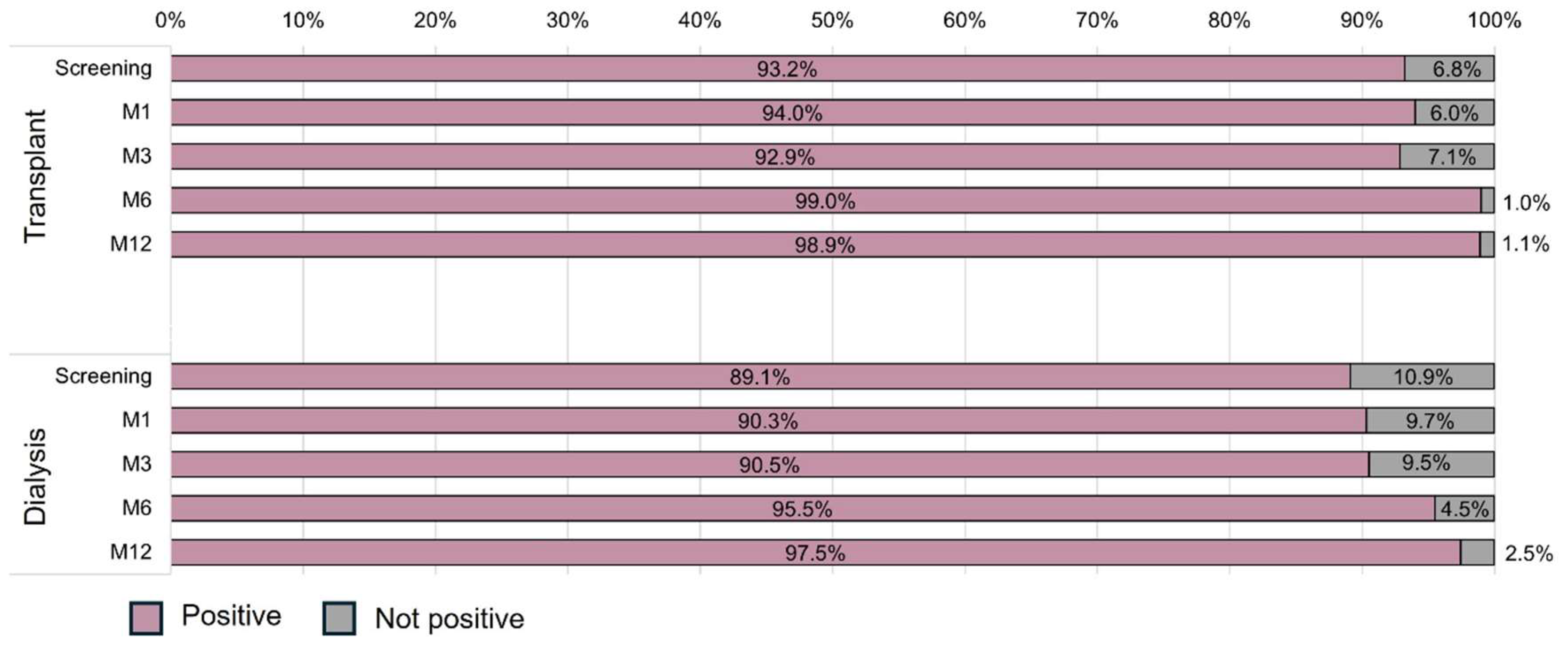

Neutralizing antibodies were highly detectable in both groups during the study (

Figure 3). There was no interaction effect between time and group (p=0.831), indicating that the evolution of the incidence of neutralizing antibodies was similar between the groups. Additionally, a time effect was observed (p=0.013) in both groups, with similar positive results at screening, M1 and M3 and an increase at M6 (99.0% vs. 95.5%) and M12 (98.9% vs. 97.5%) but not a group effect (p=0.780). The logistic model adjusted by the number of vaccine doses at screening confirmed that the prevalence of neutralizing antibodies was similar in both groups in the adjusted and unadjusted models. Additionally, the odds ratio for positive neutralizing antibodies in both groups in relation to screening was 6.98 (95%CI 1.29-39.71; p=0.024) at M6 and 22.38 (95%CI 2.56-195.35; p=0.005) at M12 (

Table 4).

3.5. Vaccines

At screening, all patients had received the complete primary vaccine schedule of an anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine approved by national health authorities. Of these, 112 (50.7%) received two doses of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine, 94 (42.5%) patients received two doses of the CoronaVac vaccine, 10 (4.5%) patients received two doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine, 3 (1.4%) patients received a heterologous regimen of one dose of BNT162b2 vaccine followed by ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine and 2 (0.9%) patients received a single dose of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine (

Table S3). In the transplant group, 90 (79.6%) patients received the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine as the primary vaccination schedule, while in the dialysis group, 81 (75.0%) patients initially received the CoronaVac vaccine (

Table S3).

As highly recommended by health authorities at that time, 181 (81.9%) patients had the opportunity to receive one or two booster doses. Of them, 151 (68.3%) patients received three doses, with a similar proportion between groups (69.0 vs. 67.6%), and 30 (13.6%) patients had already received four doses, with a higher proportion in the dialysis group (7.1 vs. 20.4%). The time elapsed since the last vaccine dose received to the screening was shorter in the transplant group (90 vs. 161 days; p=0.005), with the BNT162b2 vaccine being preferentially applied to KTRs and the CoronaVac vaccine to dialysis patients (

Table S4).

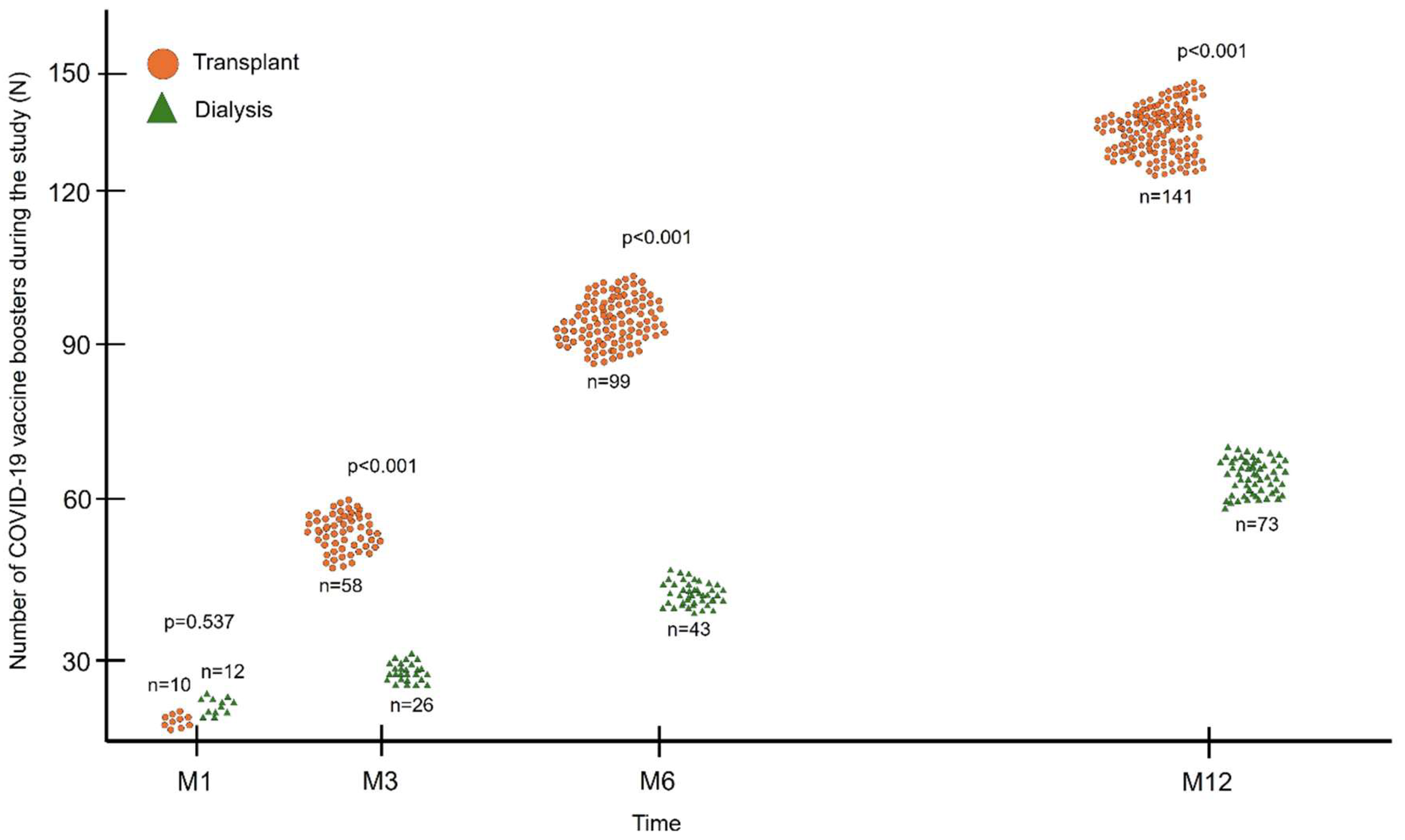

After inclusion, patients continued to receive new doses of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine during follow-up, as also recommended by health authorities. Between screening and the M1 visit, 22 patients received an additional dose of vaccine, 10 (9.3%) in the transplant group and 12 (11.9%) in the dialysis group, with no significant difference between the groups (p=0.537;

Figure 4). At the other study visits (M3, M6 and M12), the accumulated number of vaccines received by KTRs was higher than that by dialysis patients (141 vs. 74; p<0.001) (

Figure 4). The preferred booster vaccine was BNT162b2 in both groups (57.4% and 47.3%), followed by Ad26.COV2.S vaccine (16.3% vs. 27.0%), ChAdOx1 (12.8% vs. 13.5%) and CoronaVac (13.5% vs. 12.2%).

3.6. Clinical Outcomes

The incidence of COVID-19 was 24.0% among all patients but higher in the transplant group (32.7% vs. 14.8%; p=0.002). During the follow-up, there were 12 deaths, 6 in each group (p=0.936), with infections other than COVID-19 as the main etiology, followed by cardiovascular causes. There were two deaths due to COVID-19 that occurred in the transplant group. During the study follow-up, KTRs required hospitalization for any reason more frequently than dialysis patients (51.3% vs. 25.0%, p<0.001;

Table 5). During the study follow-up, 12 (10.6%) patients in the transplant group presented acute cellular rejection, adequately treated with methylprednisolone. No patient required additional treatment with rATG or plasmapheresis.

4. Discussion

This prospective, non-randomized, real-world study demonstrated that CKD patients undergoing kidney transplantation, fully vaccinated, and without a previous diagnosis of COVID-19 had low and similar seroreversion rates of SARS-CoV-2 IgG compared to dialysis patients over 12 months. Furthermore, antibody titers were lower in KTRs during the follow-up, but the incidence of neutralizing antibodies was high and similar in both groups, increasing over time. In this study, the immunosuppressive therapy used by KTRs negatively impacted the kinetics of the humoral response after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, even though this group received more vaccine boosters and had more COVID-19 diagnoses. Furthermore, age and dialysis vintage, variables associated of lower immunogenicity, were lower in KTRs and favored this group.[

7,

18] The present study was carried out during the predominance of the Omicron variant in the context of high vaccination coverage, justifying the high incidence of COVID-19 and the lower lethality.[

19]

In fully vaccinated individuals, the reduction in antibody titers is an expected and documented phenomenon.[

20] A systematic review evaluating the kinetics of anti-Spike IgG antibodies up to 6 months after the application of mRNA vaccines demonstrated a significant drop of up to 95%.[

21] Despite this, effectiveness reduction against infection and unfavorable outcomes is not relevant, as demonstrated by Feikin et al. in a systematic review evaluating four SARS-CoV-2 vaccine platforms (BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, Ad26.COV2.S and ChAdOx1), maintaining the efficacy above 70% in the general population during the pre-Omicron scenario.[

20] Once this efficacy reduction is also expected, independently of SARS-CoV-2 variant or vaccine platform, the same result was observed after Omicron, increasing the clinical relevance of applying additional doses throughout the pandemic.[

22]

In our analyses, antibody titers were numerically lower among KTRs during most of the study follow-up, with a more relevant reduction early after transplantation attributed to the lymphocyte depletion caused by induction therapy with anti-thymocyte antibody. However, the rate of detectable neutralizing antibodies was high and similar between groups since the screening, with even an increase at 6 and 12 months. Our high-risk population was prioritized early for vaccination and received additional doses; some individuals with up to 6 doses accumulated. Thereby, the boosters contributed to the low incidence of seroreversion and the maintenance of IgG titers throughout the study. However, the lower mean IgG antibody titers in the transplant group was clinically relevant, since the greater number of additional doses of vaccines received by this group did not prevent a higher incidence of COVID-19 compared to dialysis patients. Besides that, our population needs frequent visits to hospitals or clinics, where they undergo dialysis or medical care, increasing exposure and the risk of getting COVID-19. The immunogenicity generated by infection is known to be greater when compared to vaccination and provides higher protection against reinfection, hospitalization, and severe disease.[

23] Natural infection induces a broader immune response to viral antigens due to contact with the entire virus and not just the Spike protein, as occurs in immunity developed through vaccines. Even vaccines developed with the entire inactivated virus, such as CoronaVac, induce lower immunological activation than the infection.[

24]

Although there were subtle differences in immunogenicity between the vaccines, the proportion of additional doses for each vaccine was similar between the groups. A comparison between the BNT162b2, ChAdOx1, and CoronaVac vaccines also showed superiority of the first two in the seroconversion of anti-Spike IgG antibodies and a higher rate of antibody decline among those immunized with CoronaVac.[

25] In a multicenter study comparing immunogenicity in KTRs after two doses of CoronaVac or BNT162b2, the seroconversion rate was similar, however the antibody titer was lower in the group that received CoronaVac.[

26] In KTRs fully vaccinated with CoronaVac, the application of a heterologous third dose with BNT162b2 resulted in a higher seroconversion rate and antibody titers compared to a third homologous dose, with similar seroprevalence of neutralizing antibodies.[

27]

Our study was conducted during the predominance of Omicron circulation, with periods of high transmission rates and several patients diagnosed, even in vaccinated ones. However, the overall lethality was lower than historical rates,[

4] due to Omicron characteristics and high immunization coverage.[

19]

This clinical study has some limitations. First, we could not control the timing of vaccination with the study visits or the number/type of boosters once these strategies would be unsafe and unethical for a high-risk population observational study during the pandemic. Second, the effect of immunosuppression may have been attenuated by the greater number of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and the greater number of additional doses in the transplant group. Third, we did not evaluate cellular immunity, which could provide additional information about waning immunity among kidney transplant recipients and dialysis patients. Finally, the groups showed demographic differences relevant to immunogenicity, such as age and time on dialysis, both risk factors for lower vaccine response, disfavoring the dialysis group.

This study took an unprecedented approach to evaluating the initial and most intense effect of the immunosuppressive regimen on the kinetics of the humoral response after the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Although the negative impact of immunosuppression was mitigated in absolute terms of seroreversion of IgG antibodies or reduction of neutralizing antibodies by the frequent vaccine boosters and by the incidence of COVID-19, the effect of induction therapy and initial immunosuppressive therapy on the kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced humoral response was shown as lower SARS-CoV-2 IgG titers in KTRs compared to patients on dialysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Author Contributions

RDF: Participated in the research design, in the performance of the research, in data analysis, and in the writing of the paper. RMS: Participated in the performance of the research, in data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. GRA: Participated in the performance of the research, in data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. MRN: Participated in the performance of the research and reviewed the manuscript. HSG: Participated in the performance of the research and reviewed the manuscript. RS: Participated in the performance of the research and reviewed the manuscript. EFM: Participated in the performance of the research and reviewed the manuscript. EFL: Participated in the performance of the research and reviewed the manuscript. MPC: Participated in the research design and reviewed the manuscript. HTSJ: Participated in the research design, in the performance of the research, in data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. LRRM: Participated in the research design, in the performance of the research, in data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. JMP: Participated in the research design, in the performance of the research, in data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study had received grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), under register number 2021/13680-6, and from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in compliance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (Protocol code 5.156.043, approved on December 09, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Abbreviations

| CKD |

Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CIT |

Cold Ischemia Time |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| ECD |

Expanded Criteria Donor |

| HLA |

Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| KDPI |

Kidney Donor Profile Index |

| KDRI |

Kidney Donor Risk Index |

| KTR |

Kidney Transplant Recipient |

| IgG |

Immunoglobulin G |

| M |

Month |

| mTORi |

Mammalian Target Of Rapamycin Inhibitor |

| PRA |

Panel-reactive Antibody |

| rATG |

Rabbit Anti-thymocyte Globulin |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

References

- Miyah Y, Benjelloun M, Lairini S, Lahrichi A. COVID-19 Impact on Public Health, Environment, Human Psychology, Global Socioeconomy, and Education. ScientificWorldJournal. 2022;2022:5578284. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Pestana J, Cristelli MP, Foresto RD, Tedesco-Silva H, Requiao-Moura LR. The Higher COVID-19 Fatality Rate Among Kidney Transplant Recipients Calls for Further Action. Transplantation. 2022;106(5):908-10. [CrossRef]

- de Sandes-Freitas TV, de Andrade LGM, Moura LRR, Cristelli MP, Medina-Pestana JO, Lugon JR, et al. Comparison of 30-day case-fatality rate between dialysis and transplant Covid-19 patients: a propensity score matched cohort study. J Nephrol. 2022;35(1):131-41. [CrossRef]

- Pestana JM, Cristelli MP, Tedesco Silva H, Jr. The Challenges of Risk Aversion in Kidney Transplantation: Lessons From the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Brazil. Transplantation. 2024;108(4):813-8. [CrossRef]

- Syed-Ahmed M, Narayanan M. Immune Dysfunction and Risk of Infection in Chronic Kidney Disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019;26(1):8-15. [CrossRef]

- Sanders JF, Messchendorp AL, de Vries RD, Baan CC, van Baarle D, van Binnendijk R, et al. Antibody and T-Cell Responses 6 Months After Coronavirus Disease 2019 Messenger RNA-1273 Vaccination in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease, on Dialysis, or Living With a Kidney Transplant. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(3):e188-e99. [CrossRef]

- Zong K, Peng D, Yang H, Huang Z, Luo Y, Wang Y, et al. Risk Factors for Weak Antibody Response of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Adult Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:888385. [CrossRef]

- L’Huillier AG, Ferreira VH, Hirzel C, Nellimarla S, Ku T, Natori Y, et al. T-cell responses following Natural Influenza Infection or Vaccination in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):10104. [CrossRef]

- Loinaz C, de Juanes JR, Gonzalez EM, Lopez A, Lumbreras C, Gomez R, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination results in 140 liver transplant recipients. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44(13):235-8.

- Dendle C, Stuart RL, Mulley WR, Holdsworth SR. Pneumococcal vaccination in adult solid organ transplant recipients: A review of current evidence. Vaccine. 2018;36(42):6253-61. [CrossRef]

- Zinszer K, Charland K, Pierce L, Saucier A, McKinnon B, Hamelin ME, et al. Pre-Omicron seroprevalence, seroconversion, and seroreversion of infection-induced SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among a cohort of children and teenagers in Montreal, Canada. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;131:119-26. [CrossRef]

- Abbott. AdviseDx SARS-CoV-2 IgG II instructions for use 2021 [Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/146371/download.

- Tan CW, Chia WN, Qin X, Liu P, Chen MI, Tiu C, et al. A SARS-CoV-2 surrogate virus neutralization test based on antibody-mediated blockage of ACE2-spike protein-protein interaction. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(9):1073-8.

- Cerqueira-Silva T, Andrews JR, Boaventura VS, Ranzani OT, de Araujo Oliveira V, Paixao ES, et al. Effectiveness of CoronaVac, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, BNT162b2, and Ad26.COV2.S among individuals with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection in Brazil: a test-negative, case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(6):791-801.

- Medina-Pestana J, Covas DT, Viana LA, Dreige YC, Nakamura MR, Lucena EF, et al. Inactivated Whole-virus Vaccine Triggers Low Response Against SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Renal Transplant Patients: Prospective Phase 4 Study Results. Transplantation. 2022;106(4):853-61. [CrossRef]

- Skrondal AaR-H, S. Generalized Latent Variable Modeling: Multilevel, Longitudinal and Structural Equation Models. Boca Raton, FL2004.

- Gelman A, Hill, J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 2007.

- Van Praet J, Reynders M, De Bacquer D, Viaene L, Schoutteten MK, Caluwe R, et al. Predictors and Dynamics of the Humoral and Cellular Immune Response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccines in Hemodialysis Patients: A Multicenter Observational Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(12):3208-20. [CrossRef]

- Markov PV, Ghafari M, Beer M, Lythgoe K, Simmonds P, Stilianakis NI, et al. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21(6):361-79. [CrossRef]

- Feikin DR, Higdon MM, Abu-Raddad LJ, Andrews N, Araos R, Goldberg Y, et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet. 2022;399(10328):924-44. [CrossRef]

- Notarte KI, Guerrero-Arguero I, Velasco JV, Ver AT, Santos de Oliveira MH, Catahay JA, et al. Characterization of the significant decline in humoral immune response six months post-SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination: A systematic review. J Med Virol. 2022;94(7):2939-61. [CrossRef]

- Andrews N, Stowe J, Kirsebom F, Toffa S, Rickeard T, Gallagher E, et al. Covid-19 Vaccine Effectiveness against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) Variant. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(16):1532-46. [CrossRef]

- Gazit S, Shlezinger R, Perez G, Lotan R, Peretz A, Ben-Tov A, et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Naturally Acquired Immunity versus Vaccine-induced Immunity, Reinfections versus Breakthrough Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(1):e545-e51. [CrossRef]

- Ozkaya E, Yazici M, Baran I, Cetin NS, Tosun I, Buruk CK, et al. Neutralization of Wild-Type and Alpha SARS-CoV-2 Variant by CoronaVac(R) Vaccine and Natural Infection- Induced Antibodies. Curr Microbiol. 2023;80(5):162. [CrossRef]

- Barin B, Kasap U, Selcuk F, Volkan E, Uluckan O. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike receptor binding domain IgG antibody responses after CoronaVac, BNT162b2, ChAdOx1 COVID-19 vaccines, and a single booster dose: a prospective, longitudinal population-based study. Lancet Microbe. 2022;3(4):e274-e83.

- Seija M, Rammauro F, Santiago J, Orihuela N, Zulberti C, Machado D, et al. Comparison of antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 after two doses of inactivated virus and BNT162b2 mRNA vaccines in kidney transplant. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(3):527-33. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Pestana J, Almeida Viana L, Nakamura MR, Lucena EF, Granato CFH, Dreige YC, et al. Immunogenicity After a Heterologous BNT262b2 Versus Homologous Booster in Kidney Transplant Recipients Receiving 2 Doses of CoronaVac Vaccine: A Prospective Cohort Study. Transplantation. 2022;106(10):2076-84. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).