The study commenced with an initial phase that involved a comprehensive review of specialized literature. The methodology entailed the examination of previously conducted and published research and studies. The data compiled in this study were meticulously selected from various international databases, including PubMed, Google Academic, and ScienceDirect and from resources available in university library collections. The search process was carried out using specific keywords like “Alzheimer”, “etiopathology”, “β-amyloid plaques”, “neurofibrillary tangles”, and “Tau” with the application of relevant, appropriate filters. The selection criteria prioritized the type of material (such as books, review articles, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and original research).

Literature Review

Pathologically, AD is distinguished by the presence of intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles composed of phosphorylated Tau proteins, extracellular β-amyloid plaques, and amyloid cerebral angiopathies. These manifestations result from the accumulation of peptides within the medium and large blood vessels of the brain and leptomeninges. [

9,

10,

11]

Neuritic plaques, also known as “senile plaques”, are microscopically identifiable (via cryo-EM) by their spherical shape and unique, distinctive structure. They consist of a central core of beta-amyloid peptides, surrounded by a margin of numerous abnormal axonal endings.

At this level, the responses of endothelial cells, microglia, pericytes, astrocytes, and neurons, influenced by the present biomarkers, will either dictate the resistance to the cascade of pathological alterations or result in the disruption and collapse of homeostasis. Consequently, the patient will experience the manifestation of specific symptoms.[

12]

The APP gene, located on chromosome 21 and comprising 18 exons, encodes the amyloid precursor protein type I (APP) with a length of 770 amino acids. Within this protein, the E1 domain, which includes the GFLD (growth factor-like domain) and CuBD (copper-binding domain) subdomains, is linked to the E2 domain through the AcD (acidic domain). APP is regarded as the initiating point for the myriad processes described by the “amyloid cascade hypothesis”. [

13]

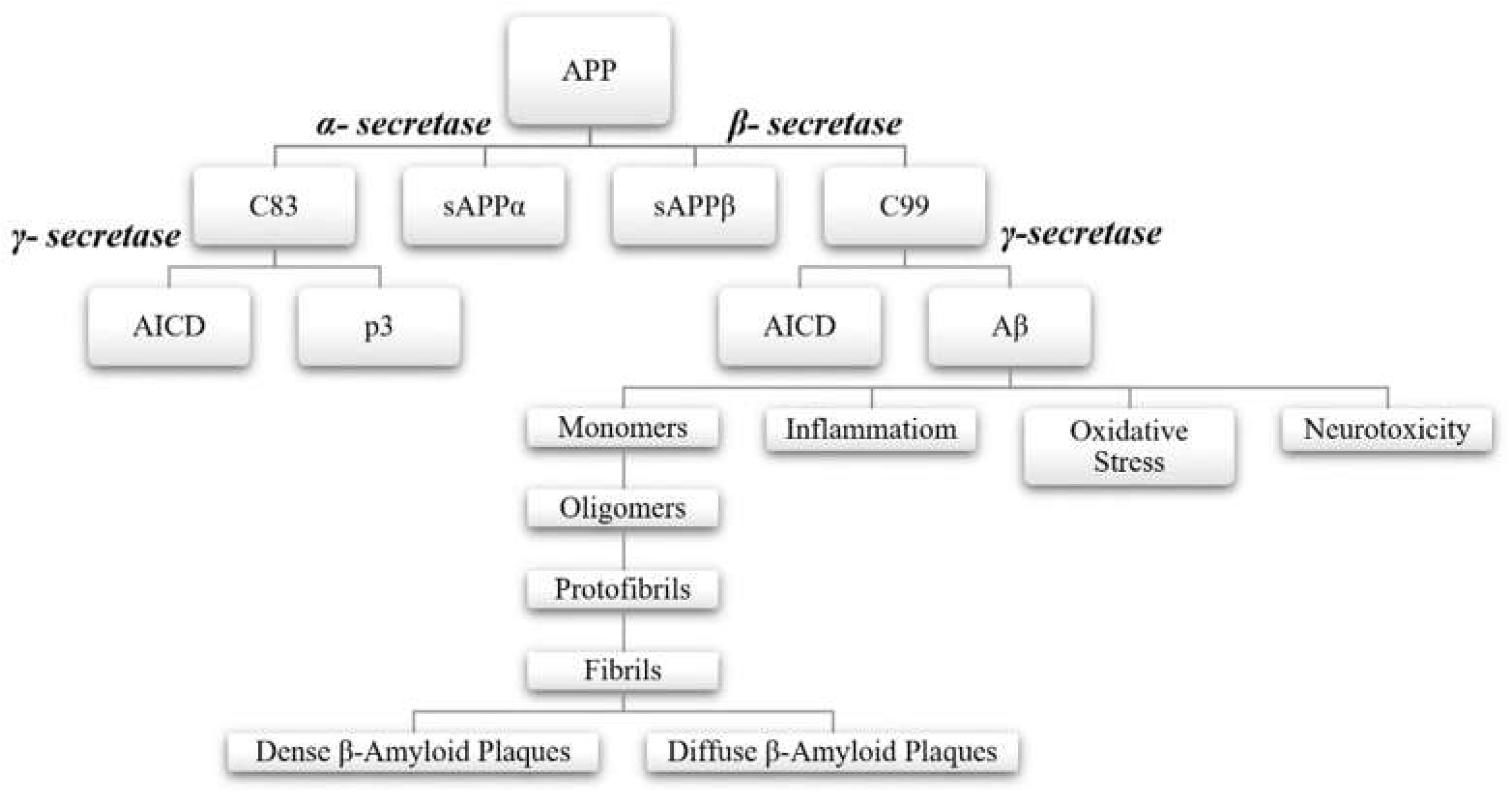

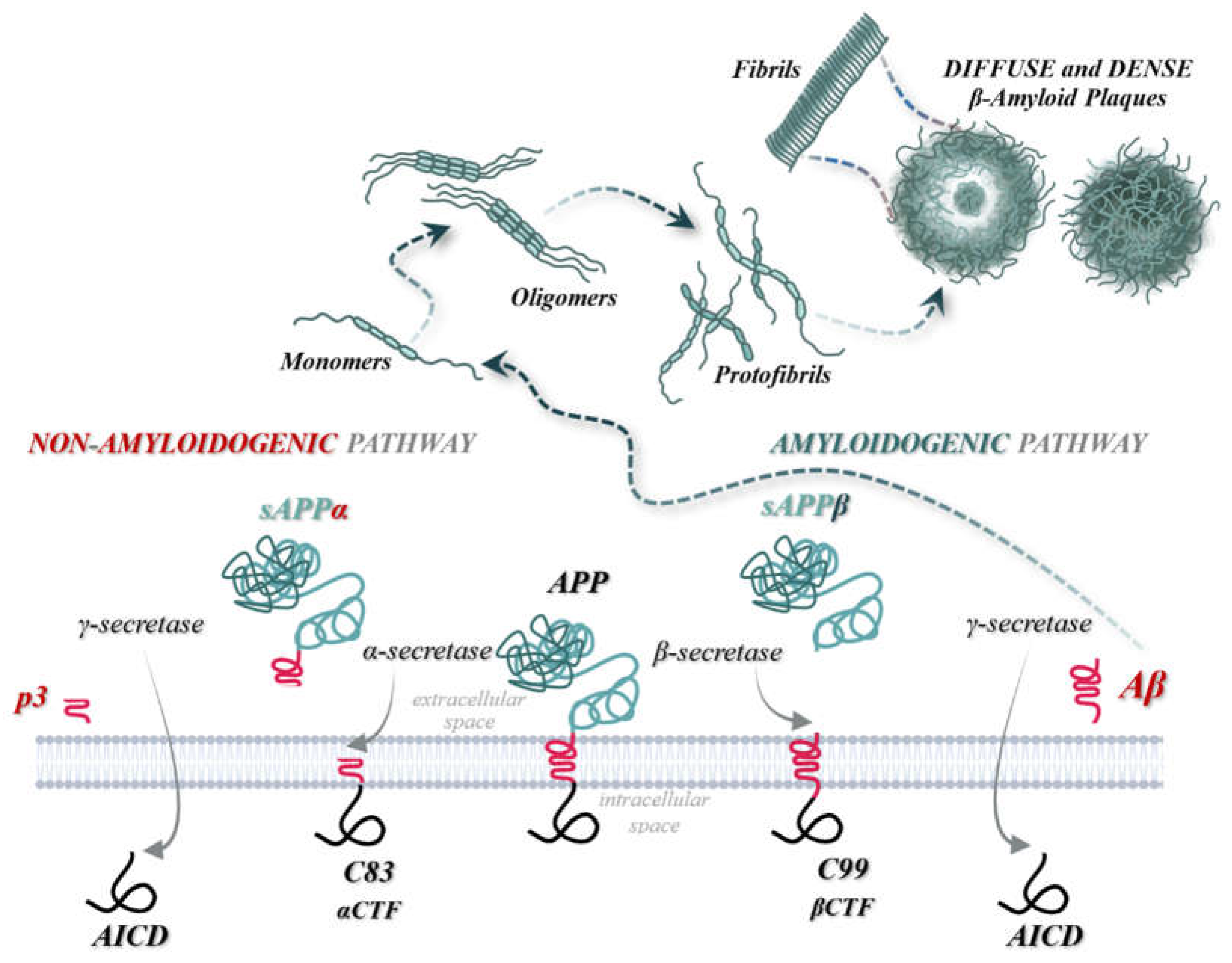

In healthy individuals, within the central nervous system, the amyloid precursor protein (APP) undergoes initial cleavage by the enzyme α-secretase, following the “non-amyloidogenic pathway”. This process prevents the formation of Aβ peptides and β-amyloid plaques. APP is then further cleaved by γ-secretase. Conversely, in patients with neurodegenerative diseases, APP follows the “amyloidogenic pathway”, where the initial cleavage is performed by β-secretase. This cleavage results in the formation, separation, and release of the sAPPβ fragment into the extracellular space. Subsequent sequential cleavages by β-secretase and γ-secretase enzymes then leads to the cutting of the C99 fragment and the production of AICD, Aβ42, and Aβ40 peptides. γ-secretase generates various forms of Aβ peptides, with lengths ranging from 37 to 46 amino acids, thereby increasing the Aβ42 to Aβ40 ratio. This phenomenon is observed in patients with familial AD due to mutations in the APP gene near the γ-secretase cleavage site, as well as in those with mutations in Presenilin 1 or 2 (PSEN1, PSEN2).[

8,

12,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]

Figure 1.

The amyloid cascade hypothesis: “the non-amyloidogenic pathway” and “the amyloidogenic pathway”.

Figure 1.

The amyloid cascade hypothesis: “the non-amyloidogenic pathway” and “the amyloidogenic pathway”.

In the “non-amyloidogenic pathway”, the enzymes α-secretase and γ-secretase are involved, whereas the “amyloidogenic pathway" involves β-secretase and γ-secretase. During the “non-amyloidogenic pathway”, the initial cleavage by α-secretase generates the ectodomain sAPPα and a membrane-attached C-terminal fragment, C83, which is composed of 83 amino acids. Subsequent cleavage at the 117th amino acid residue releases the soluble peptide p3, leaving the intracellular AICD domain. Conversely, in the “amyloidogenic pathway”, the initial cleavage by β-secretase produces sAPPβ and a membrane-bound C-terminal fragment, C99, consisting of 99 amino acids. The final cleavage by γ-secretase results in the formation of the AICD domain and the release of insoluble Aβ peptides into the extracellular space. [

3,

8,

19]

Neurotoxic effects are manifested through the overaccumulation of Aβ42 peptides. The resulting monomers and oligomers deposit in the gray matter or around cerebral blood vessels. The final formations, consisting of protofibrils and subsequently fibrils, are known as β-amyloid plaques, and are structurally classified as either dense or diffuse. Histopathology reports reveal that these extracellular aggregates initially accumulate in the basal, temporal, and orbitofrontal neocortex, and later extend to the hippocampus, diencephalon, amygdala, and basal ganglia regions. In advanced stages, these aggregates are also found in the cerebellar cortex, midbrain, and lower brainstem. [

3,

15,

20]

Figure 2.

The processing of APP via two distinct pathways and the pathogenesis β-amyloid plaques.

Figure 2.

The processing of APP via two distinct pathways and the pathogenesis β-amyloid plaques.

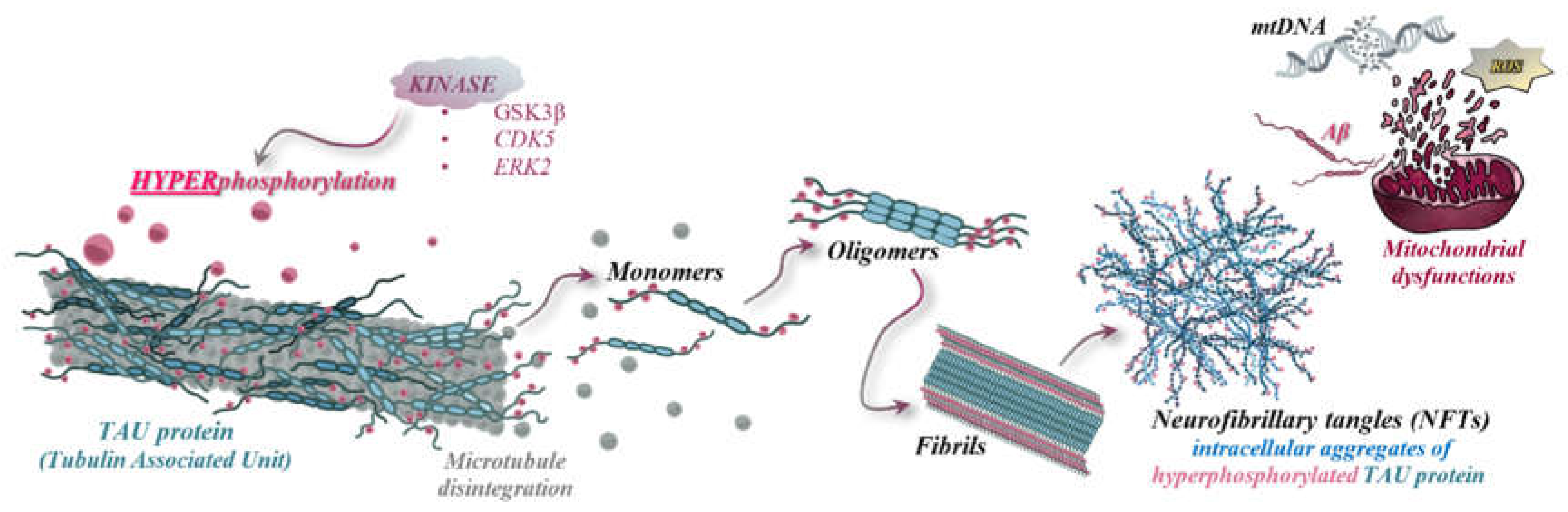

Tau protein, comprising six distinct isoforms with high solubility and abundant in the central nervous system, especially in the cortex, is produced through the alternative splicing of the MAPT gene. Physiologically, Tau stabilizes microtubules within axons. Its pathological significance arises from hyperphosphorylation, mediated by kinases such as serine-threonine kinase (PKN), leading to microtubule disassembly and subsequent aggregation. The insoluble neurofibrillary aggregates induce neurotoxicity in the central nervous system, a toxicity further amplified/exacerbated by the activation of microglia and the initiation of local inflammatory responses.[

3,

11]

The initiation of these processes occurs through the activation of the "amyloidogenic pathway". In this pathway, Aβ peptide oligomers diffuse at the synaptic level, disrupting signaling and polymerizing into insoluble fibrils, ultimately forming "senile" plaques. Polymerization is a crucial step, involving the activation of kinases that not only facilitate this process but also act on Tau proteins associated with microtubules, leading to their hyperphosphorylation. This hyperphosphorylation then initiates the polymerization process, mediated by GSK3β (glycogen synthase kinase 3β), ERK2 (extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2), CDK5 (cyclin-dependent kinase 5), and MARK4 (microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 4), culminating in the formation of insoluble neurofibrillary aggregates. [

3]

Neurofibrillary tangles, which are intracellular aggregates composed of hyperphosphorylated Tau proteins resulting from disrupted phosphorylation mechanisms, detachment from microtubules, and pairing of helical filaments, can be identified post-mortem in anatomopathology laboratories. Histopathological studies of these aggregates have revealed the following morphological, molecular, and anatomical characteristics: Tau aggregates are associated with projection neurons that have thin, long axons and elevated levels of neurofilaments. Formation of these tangles initiates in the transentorhinal cortex and, in severe stages of AD, they disseminate throughout the entire cortex. In intermediate stages of AD, these aggregates also spread to the hippocampus. [

15,

21]

Tau proteins are predominantly localized in the axonal or synaptic regions and accumulate within the somatodendritic compartment. An increase in phosphorylated forms of Tau proteins leads to the loss of neuroplasticity. [

22]

The evaluations have highlighted that the formation of intraneuronal neurofibrillary aggregates can also be influenced by increased extracellular concentrations of β-amyloid. Hyperphosphorylated Tau deposits initially occur in the entorhinal and transentorhinal areas, as well as in the locus coeruleus, and later spread to the neocortex and hippocampus.[

3,

20]

Figure 3.

The pathogenesis of NFTs, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and mtDNA degradation.

Figure 3.

The pathogenesis of NFTs, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and mtDNA degradation.

Granulovacuolar degeneration, identifiable histopathologically in the frontal cortex, the nucleus basalis of Meynert, and the hippocampus, leads to progressive neuronal death, degeneration, and irreversible cognitive decline.

According to published studies, these processes are characteristic of AD in the pyramidal cells of the hippocampus. Consequently, a reduction in the bouton density of pyramidal presynaptic neurons in layers IV and III will lead to vascular damage. This risk is particularly elevated in patients who have experienced subcortical infarcts or are diagnosed with cerebrovascular diseases, as this association exacerbates the degree of cognitive and functional decline. [

15,

23]

Cognitive and functional decline in the central nervous system is marked by the loss of synapses, a significant and drastic reduction of postsynaptic receptors, and the disappearance of neuronal structural and functional plasticity. Although there is a selective decrease in postsynaptic receptors, which are essential for short-term memory formation and the maintenance of plasticity, long-term memory remains largely unaffected until the later stages of the disease, as observed clinically. [

8]

Biochemical studies demonstrate that AD is also induced by mitochondrial dysfunctions, which result from interactions with neurofibrillary aggregates. These dysfunctions involve disruptions in the electron transport chains and the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to the damage of neural structures, neuronal degeneration, and apoptosis of nerve cells. Additionally, these processes contribute to protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation. [

11,

15]

The correlations between mitochondrial dysfunctions and AD are rooted in genetic and molecular factors, particularly in late-onset variants(LOAD). The tendency for genetic predisposition to be maternally inherited, along with the observed lower risk in descendants with paternally inherited genetic factors, has prompted research into the involvement of mitochondrial DNA(mtDNA) genes in the development of neurodegenerative diseases. Studies have shown that age is directly related to mtDNA integrity, with aging leading to the gradual degradation of mitochondrial genetic material, thereby affecting multiple brain regions, including those responsible for sensory processing and cognitive functions such as learning and memory.

The hypothesis, known as the "mitochondrial cascade", illustrates how genes encoding the components of the electron transport chain, alongside mtDNA polymorphisms, influence the rate of ROS accumulation and the efficiency of mitochondrial energy production. The rate of ROS accumulation is directly proportional to the degree of mtDNA damage and inversely proportional to the amount of energy produced (impairing complexes I-IV). Within mitochondria, ROS enhance the expression of complexes I-IV through bidirectional signaling between mitochondria and nuclear components, leading to three types of responses:

- ❖

pro-apoptotic cascade: cytochrome C is released into the cytosol in response to an apoptotic stimulus;

- ❖

formation of Aβ from amyloid precursor protein(APP): this step further exacerbates ROS accumulation;

- ❖

hypoxic signaling cascade: re-initiation of mitotic cycles generates signals that are not properly received at the neuronal level, leading to Tau hyperphosphorylation, the emergence of aneuploidies and neurofibrillary tangles, and increased mitochondrial fragmentation. Phosphorylated protein forms elevate the level of DRP1 (Dynamin-related protein 1);

It is concluded that altered mitochondrial processes and the accumulation of ROS are pivotal among the biochemical factors contributing to AD. In early-onset AD (EOAD), the condition is strictly attributed to the toxicity caused by the overproduction of Aβ. Conversely, in late-onset AD (LOAD), mitochondrial pathology is the primary cause, with Aβ peptide formation being a secondary, compensatory event. Consequently, the scientific community has introduced the concepts of "primary mitochondrial cascade" (induced by mitochondrial dysfunction) and "secondary mitochondrial cascade" (resulting from Aβ accumulation). [

15]

Another crucial element in these biochemical and molecular processes is the blood-brain barrier (BBB), whose integrity is compromised in AD, especially in mixed forms associated with vascular pathology. Alongside the glymphatic system, clearance systems, peripheral immune system, cerebral vessels, and gastrointestinal microbiome, the BBB significantly influences the clinical progression of AD. [

24]