The impact of electron screening on low-energy

fusion cross sections was first demonstrated in the late 1980s [2]. Despite extensive theoretical investigations

and numerous experiments done over the past few decades, a theory that can

account for the exceptionally high values of the screening potential required

to explain the experimental data has not been yet established. Various

experimental setups have been used, including different targets in the form of

atomic and molecular gases, differently prepared metallic targets, and the use

of both direct and inverse kinematics. A significant effort was put into eliminating

errors in the extrapolation of data to zero energy and in calculating energy

loss at ultra-low energies. However, current theoretical research in atomic

physics has not yet provided a solution to this problem. This review aims to

present a comprehensive overview of experimental studies of the electron

screening effect and some theoretical studies. The list of reviewed reactions

and corresponding screening potentials is given in Table 1.

2.1. d(d,p)t and d(d,n)3He Reactions

Electron screening in deuteron-deuteron fusion reactions has been extensively studied due to the low Coulomb barrier and comparatively high cross sections. The D(d,p)t fusion reactions have been studied at cms (center of mass) energies

E = 1.6 to 130 keV [

8]. Electron screening potential

Ue=15±5 eV was inferred. While the first D+d studies obtained using a gaseous target [

8] were compatible with the adiabatic limit (

Ue = 20 eV), screening energies obtained for various metal hosts differed among themselves and reached values of a few hundred eV.

The first study of the d(d,p)t reaction in Ti involved measuring thick target yields of protons emitted in the D(d,p)T reaction [

9]. The incident deuteron energies were between 2.5 and 6.5 keV. The measured yields were compared with those obtained by using the parameterization of cross sections at higher energies. It was found that the reaction rates in Ti are slightly enhanced over those of the bare D+D reaction for

Ed < 4.3 keV. The electron screening potential of

Ue=19 ± 12 eV was deduced.

The yields of protons produced during the D+D reaction in Pd, Au/Pd/PdO, Ti, and Au targets were measured at the incident energy ranging from 2.5 to 10 keV [

10]. The measured yields were compared to the anticipated yields obtained from an extrapolation of the cross section and stopping power at higher energies. It was found that the enhancement factor of the d(d,p)t reaction is comparable for Ti and Au targets. The screening potentials of

Ue = 250 ± 15 eV for the Pd target and 601 ± 23 eV for Au/Pd/PdO heterostructure target were measured. The variation of yields in different materials was explained by the diffusivity of deuterium in metals. Namely, the diffusivity of d in Pd and the Au/Pd/PdO heterostructure exhibited much higher values compared to Ti, and even more so when compared to Au. It was suggested that the high diffusivity in Au/Pd/PdO and Pd crystal lattice can lead to the development of a deuterium "fluidity" in the subsurface layer of the crystal lattice. It was also suggested that under the aforementioned conditions, this kind of environment could additionally promote the dynamic screening of deuteron-deuteron interactions, which arise from the coherent motion of the deuterons.

The thorough studies of electron screening in d(d,p)t reaction have been performed by Raiola et al. [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The d(d,p)t reaction was studied for deuterated metals, insulators and semiconductors. The deuterated targets were produced via the implantation of low energy deuterons. It was observed that the cross section for the fusion of two deuterons increases by more than an order of magnitude when deuterium is implanted into a metal. In the first study, a total of 29 deuterated metals and 5 deuterated insulators/semiconductors were studied to investigate the electron screening effect in the d(d, p)t reaction [

11]. Significant differences have been observed in the metals V, Nb, and Ta (group 5), as well as in Cr, Mo, and W (group 6), Mn and Re (group 7), Fe and Ru (group 8), Co, Rh, and Ir (group 9), Ni, Pd, and Pt (group 10), Zn and Cd (group 12), and Sn and Pb (group 14) when compared to measurements conducted with a gaseous d

2 target. Conversely, a relatively small effect is observed in group 4 (Ti, Zr, Hf), group 11 (Cu, Ag, Au), and group 13 (B, Al), for the insulator BeO, and the semiconductors C, Si, and Ge. The absence of an elucidation of the seemingly novel characteristic of the periodic table was evident. Raiola et al. [

12] continued the studies of the d(d, p)t reaction using a deuterated Ta target. The electron screening potential energy of

Ue =309± 12 eV was obtained. The high

Ue value was ascribed to the influence of the environment of the deuterons in the Ta matrix. Certain challenges to these measurements were addressed that are still nowadays valid. The first addressed challenge is that the

Ue value is influenced by the energy dependence of the stopping power values of deuterium in Ta at energies significantly lower than the Bragg peak energy (

Ed=300 keV). At these energies, there was a lack of energy loss data, thus the values obtained from the compilation SRIM (Stopping and Range of Ions in Matter) [

15] are based on extrapolations at

Ed⩽100keV. Also, a notable distinction between a gas target and a solid target is that in the latter channelling effects can occur. This meant that the deuteron beam could be directed by the lattice structure towards specific planes or axes, resulting in a higher likelihood of colliding with an interstitial atom such as deuterium. The critical angle for channelling is inversely proportional to the square root of the incident energy. Hence, the channelled flux is inversely proportional to the incident energy. Therefore, there is anticipated to be an increase in the cross section due to channelling that is directly proportional to

1/E. However, this phenomenon was not observed. In addition, the Ta matrix in the experiment had a random orientation, and the crystalline structure was damaged by the powerful deuteron beam, resulting in significant dechanneling effects.

Bonomo et al. [

16] have stressed that a significant difference was noticed in d(d,p)t experiments conducted with a gaseous d

2 target as compared to measurements in all metals except for the studied noble ones Cu, Ag, and Au. Insulators and semiconductors exhibited a relatively small effect in comparison. It was suggested that the substantial effect in metals can be explained by applying the classical Debye plasma screening [

6] to the quasi-free metallic electrons. The cross section enhancement was attributed to the metallic valence electrons which may come closer to the deuteron and screen its charge more effectively than atomic electrons.

An even more extensive study of the d(d,p)t reaction was pursued by Raiola et al. [

13]. A total of 58 samples, including deuterated metals, insulators, and semiconductors, were studied to investigate the electron screening effect in the d(d,p)t reaction. In comparison to the results obtained using a gaseous d

2 target, a significant effect has been observed in most metals, whereas a small effect is observed when using a gas target as well as employed insulators, semiconductors, and lanthanides. It was suggested that the significant cross section enhancements observed in metals can potentially be clarified by the application of the classical Debye plasma screening to the quasi-free metallic electrons. The data also included information regarding the hydrogen solubility in the samples. Comparing the

Ue values with the periodic table revealed a constant pattern: for each group in the periodic table, the corresponding

Ue values were either low (corresponding to "gaseous" values) for groups 3 and 4 and the lanthanides, or high for groups 2, 5 to 12, and 15. Group 14 stood out as an apparent anomaly in this regard: the metals Sn and Pb had a high

Ue value, whilst the semiconductors C, Si, and Ge demonstrated a low

Ue value, suggesting that high

Ue values are characteristic of metals. Group 13 had a comparable scenario where B is an insulator, while Al and Tl are metals. The indication is further supported by the insulators BeO, Al

2O

3, and CaO

2. The metals in groups 3 and 4, as well as the lanthanides, exhibit a significant solubility in hydrogen, approximately equal to one. Consequently, they also functioned as insulators. Metals with measured high

Ue values were known to have low solubilities, although specific values at room temperature were only known for a limited number of cases. This study revealed that the average solubility was approximately 12% while maintaining the metallic properties of the sample. It was also stressed that obtaining more accurate measurements of the electron screening effects in deuterated materials necessitates the use of an Ultra High Vacuum system. Additionally, high-depth resolution analysis methods such as SIMS (Secondary-ion mass spectrometry), AES (Auger Electron Spectroscopy), and XPS (X-ray photoelectron Spectroscopy ) were suggested to be required in situ to characterize the environment of the deuterium atoms at the surface with high precision.

The electron screening in the d(d, p)t reaction has been studied for the deuterated Pt at broad sample temperatures T = 20°C–340°C and for Co at T = 20°C and 200°C [

14]. It was found that the enhanced electron screening decreases with increasing temperature. The data represented the first instance of temperature dependence of a nuclear cross section. The screening effect for the deuterated Ti was also measured for a broad range of temperatures at T = −10

°C–200

°C; above 5°C, the hydrogen solubility dropped to values far below 1 and a large screening effect became observable. The solubility decreased with temperature and all metals of groups 3 and 4 and the lanthanides showed a solubility of a few percent at a higher temperature. At this temperature (T=200°C) a large screening became observable.

Czerski et al. [

17] suggested the diffusion coefficients or conductivity of the Al, Zr, and Ta materials may provide insight into the significant cross section enhancements. On the contrary, Raiola et al. [

12] suggested that a clear pattern did not emerge, the arguments were that the diffusion coefficient for Zr is significantly smaller than that for Al and Ta, differing by at least three orders of magnitude. However, the reported

Ue values in Ref. [

17] did not demonstrate this same tendency. Similarly, the conductivity of Zr is at least three times smaller than that of Al and Ta. Furthermore, Raiola et al. [

13] observed a connection between electron screening potential and the Hall coefficient of the metallic host while Kasagi et al. [

18] suggested that screening potential decreases with increasing deuteron concentration.

At the approximately same period as Czerski et al. [

17] and Raiola et al. [

11,

12,

13,

14] Kasagi et al. [

18] measured excitation functions for proton yield in the d(d,p)T reaction in Ti, Fe, Pd, PdO, and Au targets. Incident energies were ranging from 2.5 to 10 keV. It was found that the reaction rate at lower energies significantly changes depending on the host materials. The most enhanced d+d reaction rates occurred in PdO. At an energy of 2.5 keV, the rate increased by a factor of fifty compared to the rate of bare nuclei, and the screening energy determined from the excitation function was 600 eV. It was concluded that the significant increase could not be solely attributed to electron screening but that indicates the presence of another crucial screening mechanism in solids. Furthermore, the reaction rate enhancement was found to be highly dependent on the type of host materials. The highest increase was observed in PdO, with Pd and Fe following the trend. The obtained screening energy values were 600 ±20± 75 eV for PdO, 310 ±20± 50 eV for Pd, 200 ±15± 40 eV for Fe, 70 ±10± 40 eV for Au, and 65 ±10± 40 eV for Ti (statistical and systematic errors are given). The significant screening energies observed in PdO, Pd, and Fe implied the presence of a novel mechanism that increases the reaction rate, despite the standard approach (adiabatic limit) which predicts that the low screening energy produced by electrons in metal should be only a few tens of eV. Also, a significant correlation has been identified between the screening energy and the deuteron density. A high screening energy was associated with a low density in the host material during the irradiation. It was suggested that the increased fluidity of the deuteron in the host is the reason for the higher values of electron screening potential, as density is connected to the mobility of deuterium atoms in the host, and greater mobility leads to lower density [

18].

To investigate the influence of the metallic environment on the electron screening, the angular distributions and thick target yields of the

2H(d,p)

3H and

2H(d,n)

3He reactions were measured [

19]. The deuterons were implanted in three metal targets (Al, Zr, and Ta), at a beam energy ranging from 5 to 60 keV. The screening potential energies

Ue of 190±15 eV for Al, 297±8 eV for Zr and 322±15 eV for Ta were obtained. The experimentally obtained results were one order of magnitude larger than the value

Ue = 25±5 eV determined from a gas target experiment. A clear correlation between the screening energy and the target material was established. Further research on the

2H(d,p)

3H reaction was performed by the same group [

17] by studying the electron screening effect in the

2H(d,p)

3H reaction using the previous three targets (Al, Zr, Ta) and two new targets (T, Pd). Targets were again implanted with deuterons. The electron screening potentials of 191±12 eV, 295±7 eV 302±3 eV, 296 ± 15 eV and -20 ±5 eV were obtained for AlD, ZrD

2, TaD and PdD

0.2 targets, respectively.

The studies of the

2H(d,p)

3H reaction were continued at very low energies in UHV conditions using deuteron-implanted Zr targets [

20], [

21]. It was reported that the increase in enhancement factors seen with decreasing deuteron energy could not be solely attributed to the electron screening effect. It was also suggested that by incorporating an additional contribution from a single-particle threshold resonance, one can accurately explain the energy dependence of the experimental reaction yield. The screening energy obtained for the

2H(d,p)

3H reaction and considering threshold resonance was significantly lower, namely

Ue= 105 eV ± 15 eV compared to prior results, and agreed more closely with the theoretical estimate of 80 eV.

A series of experiments were performed to explore how surface contamination influences screening energies. The

2H(d,p)

3H reaction cross section has been measured for deuteron energies below 25 keV in a deuterated Zr target under UHV conditions and controlled target surface contamination [

22], [

23]. The increase of enhancement factors at lower energies was much lower than that determined before and could result not only from the electron screening effect but also from a 0

+ threshold resonance in

4He. It was found that the enhancement factor increases noticeably in the first hours of the experiment, and then decreases until no screening effect is evident. It was also suggested that the cause of it might be a thick contamination that has covered the target surface. Initially, the target contamination was minimal (less than 1 atomic monolayer) and did not lead to energy losses of projectiles. However, it did create crystal lattice defects that locally alter the band structure of the target.

Further experimental efforts on d(d,p)t cross section were performed in Ultra High Vacuum (UHV) conditions. Total cross sections and angular distributions of the

2H(d,p)

3H and

2H(d,n)

3He reactions were measured using a deuteron beam with energies ranging from 8 to 30 keV [

24]. The cleanliness of the target surface has been confirmed by a combination of Ar sputtering and Auger spectroscopy. The online analysis method was also used to monitor the uniformity of the implanted deuteron densities. The screening energy for Zr obtained confirmed the high value obtained in a prior experiment of the same group [

17] conducted under less optimal vacuum conditions.

To investigate the interplay between condensed matter physics and nuclear physics Zirconium samples were exposed to different conditions and energy of deuteron beams in the accelerator system with a UHV at the eLBRUS laboratory, University of Szczecin [

25]. X-ray diffraction (XRD) and positron annihilation spectroscopy (PAS) were used to analyze both irradiated and non-irradiated samples. The first method provided data on changes in crystal lattice parameters and the potential formation of hydrides due to dislocations formed during sample irradiation. The second method could identify the depth distribution of crystal defects, with a particular sensitivity to vacancies. The studied Zr samples were implanted with carbon and oxygen ions to create similar conditions that occur in nuclear reaction experiments and study their impact on the production of vacancies. It was suggested that the increased electron screening effect in the deuteron fusion process at very low energy may be due to the creation of many vacancies when samples are irradiated with deuterons. Carbon and oxygen impurities can impact this process by altering the depth distribution of vacancies and their diffusion. However, it was concluded that their influence on the strength of the electron screening effect is minimal. The experimental results demonstrate that irradiating Zr targets with deuterons results in high vacancy density which in turn leads to an increase in effective electron mass and consequently to the observed high electron screening effect in d+d reactions at low deuteron energies. This also explained the increase of the reaction yield shortly after cleaning the Zr target using argon sputtering under UHV conditions.

Further theoretical research by Czerski et al. [

26] revealed a significant impact of the single-particle 0

+ threshold resonance in

4He. The resonance is supported by further considerations that are based on the weak coupling between the 2 + 2 and 3 + 1 clustering states of the compound nucleus

4He. These arguments also predicted a large partial width for the internal production of electron-positron pairs, which leads to an overestimation of the proton width.

Most recently [

27], electron emission in the d+d reaction supporting the existence of the single-particle threshold resonance in

4He has been observed for the first time. The measured electron energy spectrum and the electron-proton branching ratio agreed well with the assumed electron-positron pair creation decay of the 0

+ resonance state to the ground state. Additionally, the experimental energy spectrum was accurately reproduced by extensive Monte Carlo simulations [

27]. The electron screening effect was studied in the d(d,n)

3He reaction in the ultralow deuteron collision energy range in the deuterated metals (ZrD

2, TiD

2 and TaD

0.5) [

28]. The targets were made via magnetron sputtering of titanium, zirconium and tantalum in a gas (deuterium) environment. The detection of neutrons with an energy of 2.5 MeV from the d(d,p)t reaction was done with plastic scintillator detectors. The energy dependence of the astrophysical

S factor for the d+d reaction in the deuteron collision energy range of 2 to 7 keV was measured. The electron screening potential

Ue of the interacting deuterons has been measured for the ZrD

2 (

Ue=205 ± 35 eV), TiD

2 target (

Ue= 125 ± 34 eV), and TaD

0.5 target (

Ue = 313 ± 58 eV).

2.2.3. He(d,p)4He Reaction

The

3He(d,p)

4He reaction plays an important role in primordial nucleosynthesis of the light elements D,

3He,

4He, and

7Li [

4].

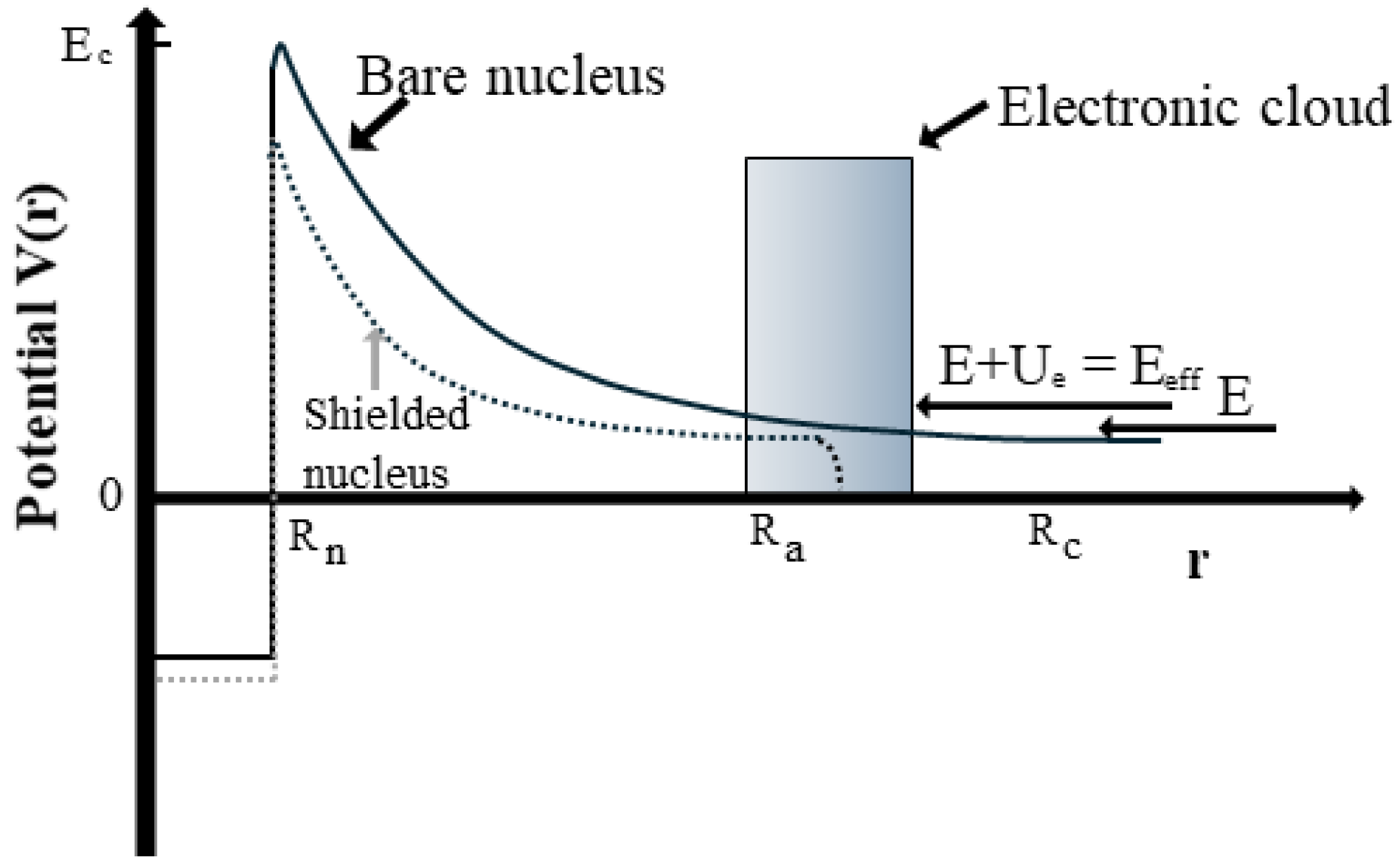

The reaction

3He(d, p)

4He has been studied in the energy range of 5.9 to 41.6 keV using deuterium (d) projectiles and

3He atomic gas target nuclei, as well as using

3He projectiles and d

2 molecular gas target nuclei [

2]. The results demonstrated a significant increase in cross sections, which may be described as almost exponential, as compared to the case where nuclei were not surrounded by electrons (bare nuclei). The electron cloud around the target nucleus, whether atomic or molecular, acts as a screening potential. As a result, the projectile effectively encounters a decreased Coulomb barrier for d projectiles and

3He (atomic) target nuclei. An electron screening potential of

Ue= 120±10 eV was obtained. The increase was about halved for the D(

3He, p)

4He reaction where a screening potential of

Ue = 66±4 eV was obtained. The screening energy was expected to occur at lower energies due to the electron cloud in the d

2 molecule being at factor two greater distances than in the d atom.

The cross section measurements of the D(

3He,p)

4He reaction have been extended to include energy as low as

Ecm = 5.4 keV [

29]. The data had higher precision in comparison to prior research and validated the presence of electron screening. The combined analysis of the obtained dataset and past data [

2,

30] yielded an electron screening potential of

Ue = 123 ± 9 eV (A similar analysis of previous data for

3He(d,p)

4He leads to

Ue= 186 ± 9 eV). The fusion reaction

3He(

4He,2p)

4He was studied at very low energy (for the first time the measurements were performed below the Gamow peak energy) at the Laboratory for Underground Nuclear Astrophysics (LUNA) accelerator facility located at the Gran Sasso National Laboratory (LNGS) [

31], [

32]. It was concluded that enhancements at low energies are due to the electron screening effect. The measured screening potential

Ue=294±47 eV was close to the one from the adiabatic limit (

Ue=240 eV).

Angular distributions of cross sections and complete sets of analyzing powers for the

3He(d,p)

4He reaction have been measured at five energies between

Ed=60 and 641 keV. The bare-nuclear cross section derived from the

R-matrix parametrization was used to obtain the electron screening potential [

33]. A screening potential of 177±29 eV was reported.

Although the first 15 years of studies of electron screening were quite fruitful, the beginning of 2000 marked the start of the increased interest of the scientific community in this effect. One of the first performed measurements in the 2000s was of the D(

3He,p)

4He cross section in the energy range of 4.2 to 13.8 keV at the LUNA underground accelerator facility [

34]. An electron screening potential energy

Ue of 132 ± 9 eV, notably higher than the anticipated 65 eV value from an atomic physics model was obtained. In addition, it was concluded that the measured stopping power of the

3He ions in the d

2 target (gaseous) agrees well with the standard compilation [

35].

The cross section of the reactions

3He(d,p)

4He and D(

3He,p)

4He has been experimentally determined for cms energies ranging from 5 to 60 keV and 10 to 40 keV, respectively. The experiments were conducted to measure the magnitude of the electron screening effect, resulting in the electron-screening potential energy values of

Ue=219±7 eV and 109±9 eV [

36]. These values are considerably larger than the corresponding values predicted by the adiabatic limit which results in

Ue=120 eV and 65 eV, respectively.

One of the sources of uncertainty is the bare nuclear cross sections required to deduce the experimental screening value. To eliminate this uncertainty the Trojan Horse Method (THM) has been developed [

37], which allows for an indirect determination of the bare nuclear cross sections at very low energies.

The cross sections of the 2H(d,p)3H

and 2H(d,n)3He reactions have been measured via the

THM that was applied to the quasi-free (QF)

2H(

3He,p

3H)

1H and

2H(

3He,n

3He)

1H reactions at 18 MeV off the proton in

3He [

38]. The value of

Ue=13.4 ± 0.6 eV was extracted for

2H(d,p)

3H while a value of

Ue=11.7 ± 1.6 eV (below the adiabatic limit

Ue=14 eV for a molecular deuteron gas target) was extracted for

2H(d,n)

3He reaction.

The fusion process between protons and deuterons has been studied by employing a proton beam with an energy of 260 keV and a graphite target implanted with deuterium [

39]. The resulting product of the reaction,

3He, mostly deexcites through the emission of γ-rays. However, in contrast to an γ ray,

3He can also emit an electron with a discrete energy of 5.6 MeV. It was suggested that the probability of emission could be enhanced as a result of electron screening in graphite. Specifically, the internal conversion coefficient for a 5.6 MeV dipole transition in a helium nucleus is approximately 10

-8. In contrast, the measured coefficient was 10

4 times greater. Enhanced emission of 5.6 MeV electrons was ascribed to the electron screening, more specifically, to the electrons coming into the proximity of the nuclei and actively participating in the reaction.

The d(

3He,p)

4He reaction [

40] was investigated in the

3He

+ ion energy range from 16 keV to 34 keV using TiD targets with Miller indices of [111] and [100]. It was shown that the target crystal structure had a significant influence on the reaction enhancement factor, namely the enhancement factor for

Eeff=6.51 keV was as twice as high for the TiD target with Miller indices [111]. It was concluded that dependence of the enhancement factor for the reaction d(

3He, p)

4He as a function of energy is mostly influenced by solid-state effects, in particular by channelling. It was reported that high enhancement factors for the d(

3He, p)

4He reaction in the 16 to 22 keV energy range most likely point to the appearance of a novel mechanism that enhances the reaction's yield at lower energies. It was suggested that one of these effects is the aforementioned channelling of particles in crystalline structures.

The same group reported similar measurements of d(

3He,p)

4He reaction enhancement factor using targets ZrD with Miller indices [111] and [100], [

41]. The measured enhancement factors of the d(

3He,p)

4He reaction were also higher for the ZrD target with a crystal structure characterized by the Miller index [100] than for the target with the Miller index [111], which was attributed to the contribution of channelling. In addition, a non-proportional increase of the enhancement factors for the d(

3He,p)

4He reaction in the energy range from 16 to 22 keV was explained with a low-lying resonance effect in

5Li.

2.3.6. Li(p,α)3He, 6Li(d,α)4He, and 7Li(p,α)4He Reactions

The 7Li(p,α)

4He reaction is one of the thermonuclear reactions involved in the stellar cycle of fusion of heavy elements in the universe [

4].

The

6Li(p,α)

3He and

7Li(p, α)

4He reactions were investigated at energies from 10 to 65 keV using solid LiF targets [

42]. The screening potential of

Ue = 210 eV was measured in the case of

6Li(p,α)

3He, which is slightly lower than the adiabatic limit of 240 eV, while

Ue = 300 eV was measured in the case of

6Li(p,α)

3He being somewhat higher. The results showed a significant increase caused by electron screening effects, following an exponential trend.

Shortly afterwards the first electron screening studies reported in Ref. [

2] and Ref. [

42], at the beginning of the 1990s, reactions

6Li(p,α)

3He,

6Li(d,α)

4He, and

7Li(p,α)

4He were investigated [

30], [

43] in the cms energy range of 10 to 1004 keV. Each studied reaction employed hydrogen projectiles and solid LiF targets, as well as Li projectiles and molecular hydrogen gas targets. Electron screening had exponential effects on low-energy fusion cross sections in all studied cases. The impact of electron screening was slightly more pronounced when atomic target projectiles were used, as opposed to molecular H

2 or d

2 gas targets. Namely, for the

6Li(p,α)

3He reaction electron screening potential of

Ue=440±150 eV was obtained for the molecular hydrogen target and

Ue=470±150 eV was obtained for the LiF target. For the

6Li(d,α)

4He reaction electron screening potential of

Ue=330±120 eV was obtained for the molecular deuterium target and

Ue=380±250 eV was obtained for the LiF target. Last but not least, for the

7Li(p,α)

4He reaction electron screening potential of

Ue=300±160 eV was obtained for the molecular hydrogen target and

Ue=300±280 eV was obtained for LiF target. The possible impact of the isotope effect was also studied [

43]. If the isotopic effect on electron screening is insignificant, all three reactions

6Li(p,α)

3He,

6Li(d,α)

4He, and

7Li(p, α)

4He should have demonstrated equal enhancement for each set of experimental data. The measurements fully confirmed this expectation since the deduced values of the screening potential energy

Ue for all three reactions were equal within experimental error. For the

6Li(p,α)

3He reaction an electron screening potential

Ue=470±150 eV was inferred for atomic and

Ue=440 ± 150 eV for the molecular hydrogen target. For the

6Li(d,α)

4He reaction

Ue=380 ± 250 eV was inferred for atomic and

Ue=330 ± 120 eV for molecular deuterium target. For the

7Li(p, α)

4He reaction

Ue=300±280 eV was inferred for atomic hydrogen and

Ue=300±160 eV for molecular hydrogen target. The obtained

Ue was consistent with the results on the

3He(d,p)

4He reaction [

2], [

29]. Moreover, the

Ue values for atomic targets were considerably larger than the expected value of

Ue=240 eV from the adiabatic model. It should be stressed that the adiabatic approximation, compared to other electron screening models, provides the largest screening potential theoretical estimates.

The

2H(

6Li,

α)

4He reaction was studied by applying the THM to the

6Li(

6Li,

αα)

4He three-body reaction [

44]. The astrophysical

S(

E) factor has been extracted in the energy range between 10–800 keV for the two cases of target and projectile quasifree break-up. The electron screening potential energy

Ue=320±50 eV has been extracted in a model-independent way by comparing direct and THM data.

The cross section of the

6Li(d,α)

4He reaction was measured for deuteron energies ranging from 50 to 180 keV [

45]. The angular distributions and excitation function up to 1 MeV were analyzed using a distorted-wave Born approximation to assess the strength of a subthreshold resonance. At subcoulomb energy, this resonance significantly increases the astrophysical S factor by dominating the cross section. The reported electron screening energy of 130±20 eV was significantly lower than the value reported in prior studies [

30]. It was concluded that the difference may result from the fitting procedure, specifically from the polynomial fit of the measured cross section, used to determine the experimental value for the screening energy.

Kasagi et al. measured the α particle yields emitted in the

6,7Li(d,α)

4,5He reactions in PdLi

x and AuLi

x targets. [

46]. The yields were measured as a function of the incident energy that was ranging from 30 to 75 keV. It was found that the reaction rate in Pd at lower energies is significantly increased compared to the rate anticipated for the cross section for the reaction involving bare nuclei. However, no such increase was observed in Au. A screening mechanism was implemented to accurately replicate the excitation function of the thick target yield for each of the metals. The inferred value of

Ue for Pd was 1500±310 eV, while for Au was just 60±150 eV. It was again concluded that the observed improvements in the Pd example cannot be solely attributed to electron screening, indicating the presence of an additional and significant screening mechanism that occurs in metals (similar to [

18]).

The electron screening effect was also studied in proton induced reactions in

6,7Li for different environments: Li

2WO

4 insulator, Li metal and PdLi

x alloy [

47,

48]. The incident proton energies were between 30 and 100 keV. Large electron screening was found for Li metal (

Ue=1280±60 eV) and PdLi

1% alloy

(Ue = 3790±330 eV) while a small effect, consistent with the adiabatic limit was observed for Li

2WO

4 insulator (

Ue = 185±150 eV) [

48]. Similar results have been found for the

6Li(p,α)

3He reaction (

Ue = 320 ± 110, 1320 ± 70, and 3760 ±260 eV for Li

2WO

4, Li, and PdLi

1%, respectively) supporting the hypothesis of the isotopic independence of the electron screening effect. These high values of

Ue were again explained with the Debye plasma model applied to the quasi-free metallic electrons present in these materials. It was suggested that the results above together with prior studies of d(d,p)t [

11,

12,

13,

14] and

9Be(p,α)

6Li in metals [

49], confirm the Debye model scaling, where

Ue is proportional to Z

t (the charge number of the target). The results were reanalyzed in Ref. [

47] using the

R-matrix and polynomial fits which were used to verify the bare astrophysical

S factor with greater accuracy compared to earlier studies [

48]. Using the newly obtained

Sb(E) data, a reassessment of the low energy data for various targets, including Li

2WO

4 insulator, Li metal, and PdLix alloys, verified that the significant electron screening effects can be accounted for by applying the Debye plasma model to the quasi-free electrons in the metallic samples. The reanalysis also revealed that for the

7Li(p,α)

4He reaction, the electron screening energies are 1180 ± 60 eV for Li metal and 3680 ± 330 eV for Pd

94.1%Li

5.9%. The electron screening energy obtained for the

6Li(p,α)

3He reaction was

Ue = 1280 ± 70 eV for Li metal, and

Ue = 3710 ± 185 eV for Pd

94.1%Li

5.9%. The reanalyzed

Ue values were around 100 eV lower, but they were within the error margin compared to the values stated in the reference [

48].

The

1H(

7Li,α)

4He reaction was studied in the energy range of 0.34 to 1.05 MeV using lithium beams. Hydrogen was diffused into Pd and PdAg alloy foils [

50]. A significant electron screening effect was detected only when foils were subjected to tensile stress. There was no correlation found between the screening potential and the hydrogen content or Hall coefficient of the metallic host. The assertions by Kasagi et al. [

46] that the screening potential decreases as the hydrogen concentration in metal increases could not be confirmed as the used concentrations were at least five times higher than the ones used by Kasagi et al. [

46] and still, a greater screening potential was observed. Electron screening has been further studied in the fusion reaction

1H(

7Li,α)

4He using hydrogen-implanted Pd, Pt, Zn, and Ni targets at lithium beam energies ranging from 0.34 to 2.07MeV [

51]. A significant electron screening effect has been detected in all the targets.

2.4.10. B(p,α)7Be and 11B(p,α)8Be and 9Be(p,α)6Li and 9Be(p,d)8Be Reactions

The

11B(p,α)

8Be reaction is the main destruction channel for the most abundant boron isotope in stars [

4].

The fusion reactions

10B(p,α)

7Be and

11B(p,α)

8Be were investigated in a cms range of 17 to 134 keV by employing intensive proton beams and thick solid targets [

52]. The low-energy data for the

11B(p, α)

8Be reaction exhibited an exponential increase (up to 1.9 times) in the astrophysical

S(E) factor which was attributed to electron screening effects. The low-energy data for the reaction

10B(p,α)

7Be showed an enhancement factor larger than 200, which could not be attributed solely to electron screening effects. The enhancement stems from the high-energy tail of an anticipated s-wave resonance at

ER=10 keV. Regarding the electron screening potential, the deduced value was

Ue = 430 ± 80 eV, obtained from the direct measurement of the

11B(p,α)

8Be

S(E) factor under the hypothesis of no isotopic dependence of

Ue. The adiabatic limit yields a theoretical value of 340 eV. The THM was used to measure the

11B(p,α

0)

8Be reaction [

53]. This was achieved by inducing the QF reaction

2H(

11B,α

08Be)n at a laboratory energy of 27 MeV. An enhanced data analysis technique has been utilized to derive the astrophysical

S(E) factor from about 600 keV to zero energy. Electron screening potential of

Ue = 472 ±160 eV was reported

The

10B(p,α

0)

7Be reaction has been measured for the first time at the Gamow peak using the THM applied to the

2H(

10B,α

07Be)n QF reaction [

54]. The electron screening potential value has been determined to be 240 ± 200 eV using the measured bare-nucleus THM S(E) factor. The substantial error accounts for the uncertainties associated with the THM S(E) factor

The excitation functions and angular distributions of the

9Be(p,α)

6Li and

9Be(p,d)

8Be reactions were measured within the

Ep =16 to 390 keV energy range [

49]. The data parametrization, especially at low energies, resulted in an electron screening potential energy of

Ue = 900 ±50 eV, which was significantly larger than the expected value of 240 eV based on the adiabatic limit.

Thick target α-yields from the

9Be(p, α)

6Li reaction were measured in the ultra-low energy range, between 18 and 100 keV [

55]. It was obtained that the screening potential energy of beryllium is

Ue=545 ±98 eV, which is significantly higher than the expectation from the adiabatic model of 264 eV. Nevertheless, when looking at it from an experimental standpoint, the value is substantially less than other direct measurements (Zahnow et al., 900 ±50eV [

49]).

Romano et al. [

56] and Wen et al. [

57] have examined the

9Be(p,α)

6Li reaction by employing the THM on the

2H(

9Be,

6Liα)n reaction. Wen et al. [

57], for example, reported electron screening potential of

Ue = 676 ±86 eV. The result has been extracted in a model-independent way by comparing the direct and THM data; Romano et al. [

56] reported only two points below the resonance region with poor resolution, so the results from Wen et al. [

57], were used as representative of the THM results for comparison.

2.5. Reactions with Heavier Targets or Incident Nuclei

Electron screening in the

50V(p,n)

50Cr reaction was investigated at

Ep = 0.75 to 1.55 MeV in several environments: VO

2 insulator, V metal, and PdV

10%alloy. The reported screening energy for the metal and alloy were 27±9 keV and 34±11 keV, respectively, in comparison to the insulator. The reaction

176Lu(p,n)

176Hf was also studied at comparable proton energies for a Lu

2O

3 insulator, Lu metal, and PdLu

10% alloy [

58]. A narrow resonance was detected at

Epr = 0.81 MeV with a noticeable Lewis peak. The proton resonance energy shifted by 32 ± 2 keV and 33 ± 2 keV for the metal and alloy, respectively, compared to the insulator. The authors concluded that the electron screening effect happens throughout the periodic table and is not limited to reactions involving light nuclides that have been examined previously. Furthermore, it was concluded that two reactions involving neutrons in the exit channel show that electron screening affects the entry channel of the reaction and is not influenced by the charged particles in the exit channel. The

Ue values were explained by applying Debye's plasma model to the quasi-free electrons in the metallic samples. The Debye model predicts a temperature dependence of the screening proportional to

T1/2 which was tentatively observed in [

14]. The aforementioned observations, along with prior research on fusion reactions (d+d, Li+p and Be+p in metals) involving different nuclei, supported the Debye model's prediction that the electron screening potential scales with the nuclear charge of the target atoms. Moreover, it was anticipated using the same model, that the α and β

+ decay rates would increase when radioactive sources are placed in metals at low temperatures [

13,

14]. Although Debye screening cannot be used for strongly coupled electron plasmas like metals at moderate temperatures, the idea has sparked significant interest [

59]. The predictions based on the Debye-Hückel hypothesis about the temperature impact on the radioactive decay of implanted nuclei were not confirmed by the experiments. The measured values significantly deviated from their predicted values. Furthermore, their claims were in direct opposition to all other tests, especially the LTNO (Low-Temperature Nuclear Orientation) observations from the last decades. A material dependence would likely have been identified before, considering that nuclei crucial for nuclear technology have been studied in various chemical compounds, including pure metals, for many years. Most recently, the decay of

19O(

β−) and

19Ne(

β+) implanted in niobium in its superconducting and metallic phases was measured using purified radioactive beams produced by the SPIRAL (The Système de Production d’Ions Radioactifs en Ligne) facility [

60]. Half-lives and branching ratios measured in the two phases were consistent within a 1

σ error bar.

No significant electron screening has been seen in the following proton-induced reactions:

55Mn(p,γ)

56Fe,

55Mn(p,n)

55Fe,

113Cd(p,n)

113In,

115In(p,n)

115Sn,

50V(p,n)

50Cr, and

51V(p,γ)

52Cr [

51]. No change in the resonance energy between the metallic and insulator environments was seen in the examined (p,n) and (p,γ) reactions within the experimental error. The results disagreed with the data in Ref. [

58] that indicated significant electron screening potentials and resonance energy shifts in nuclear reactions with high-Z targets. It was suggested that the significant electron screening effect observed when hydrogen and deuterium nuclei are implanted into a metallic environment, or when hydrogen nuclei are absorbed from the gas phase and subjected to stress, may indicate that electron screening is influenced by the location of the target nuclei within a crystal lattice. The radiation damage from ion implantation creates crystal vacancies where hydrogen nuclei can be captured. Mechanical stress can lead to the movement of protons from regular interstitial positions to displaced interstitial positions in the crystal, where the hydrogen nuclei are once again captured.

Physically[

61]The electron screening was investigated in the nuclear reactions

1H(

7Li,α)

4He,

1H(

19F,αγ)

16O, and

2H(

19F,p)

20F using a metallic environment as a probe, namely Pd foils that contained hydrogen [

62]. A significant enhancement in the cross section due to electron screening in the first target (soft Pd foil) was not observed. However, in the second target (hard Pd foil), a high electron screening potential for all three reactions was found, surpassing the theoretical predictions by an order of magnitude compared to the adiabatic limit. The data indicated that the discrepancy can be attributed to the influence of the host's crystal lattice structure and the location of the target nuclei in the metallic lattice on the electron screening potential. It was suggested that the different electron densities result in different screening potentials, as evidenced by the significant differences in Knight shifts measured in the targets. This suggested that the screening effect is not linked with the static electron concentrations around interacting nuclei, contrary to what the existing theory predicts.

Table 1.

The list of studied reactions, corresponding adiabatic limits and experimentally deduced electron screening potentials.

Table 1.

The list of studied reactions, corresponding adiabatic limits and experimentally deduced electron screening potentials.

| |

Reaction |

Uead |

Ueexp |

Remark |

Reference |

| 1. |

D(d,p)T |

20 eV |

15 ± 5 eV |

molecular target |

[8] |

| 2. |

D(d,p)T |

20 eV |

19 ± 12 eV |

Ti |

[9] |

| 3. |

D(d,p)T |

20 eV |

250 ± 15 eV

601 ± 23 eV |

Pd

Au/Pd/PdO heterostructure target |

[10] |

| 4. |

d(d,p)t |

39 eV |

309± 12 eV |

Ta |

[12] |

| 5. |

d(d,p)t |

39 eV |

440 ± 40 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽30 eV

350 ± 30 eV

220 ± 20 eV

350 ± 40 eV

450 ± 50 eV

200 ± 20 eV

450 ± 80 eV

43 ± 20 eV

140 ± 20 eV

320 ± 40 eV

83 ± 20 eV

400 ± 40 eV

220 ± 20 eV

220 ± 30 eV

840 ± 70 eV

800 ± 70 eV

23 ± 10 eV

390 ± 60 eV

200 ± 20 eV

87 ± 20 eV

340 ± 14 eV

220 ± 20 eV

700 ± 70 eV

330 ± 30 eV

40 ± 50 eV

61 ± 20 eV

440 ± 50 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽30 eV

52 ± 20 eV

45 ± 20 eV

60 ± 20 eV |

Mg

Al

Ti

V

Cr

Mn

Fe

Co

Ni

Cu

Zn

Y

Zr

Nb

Mo

Ru

Rh

Pd

Ag

Cd

Sn

Hf

Ta

W

Re

Ir

Pt

Au

Pb

BeO

B

C

Si

Ge |

[11] |

| 6. |

d(d,p)t |

39 eV |

180±40 eV

440±40 eV

520±50 eV

480±60 eV

320±70 eV

390±50 eV

460±60 eV

640±70 eV

380±40 eV

470±50 eV

480±50 eV

210±30 eV

470±60 eV

420±50 eV

215±30 eV

230±40 eV

800±90 eV

330±40 eV

360±40 eV

520±50 eV

130±20 eV

720±70 eV

490±70 eV

270±30 eV

250±30 eV

230±30 eV

200±40 eV

670±50 eV

280±50 eV

550±90 eV

480±50 eV

540±60 eV

⩽60 eV

⩽60 eV

⩽80 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽50 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽70 eV

⩽40 eV

⩽40 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽60 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽70 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽50 eV

⩽50 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽30 eV

⩽70 eV

⩽50 eV

⩽70 eV

⩽40 eV |

Be

Mg

Al

V

Cr

Mn

Fe

Co

Ni

Cu

Zn

Sr

Nb

Mo

Ru

Rh

Pd

Ag

Cd

In

Sn

Sb

Ba

Ta

W

Re

Ir

Pt

Au

Tl

Pb

Bi

C

Si

Ge

BeO

B

Al2O3

CaO2

Sc

Ti

Y

Zr

Lu

Hf

La

Ce

Pr

Nd

Sm

Eu

Gd

Tb

Dy

Ho

Er

Tm

Yb |

[13] |

| 7. |

d(d,p)t |

39 eV |

675 ± 70 eV

530 ± 40 eV

530 ± 40 eV

465 ± 38 eV

480 ± 70 eV

640 ± 70 eV

480 ± 60 eV

≤30 eV

≤50 eV

250 ± 40 eV

295 ± 40 eV

290 ± 65 eV

320 ± 50 eV

270 ± 75 eV

205 ± 70 eV

265 ± 70 eV

370 ± 70 eV

245 ± 70 eV

200 ± 50 eV

190 ± 50 eV

314 ± 60 eV

120 ± 60 eV

340 ± 85 eV

340 ± 80 eV

340 ± 70 eV

165 ± 50 eV

360 ± 80 eV

260 ± 80 eV

110 ± 40 eV

≤50 eV |

Pt 20 °C

Pt 100 °C

Pt 200 °C

Pt 300 °C

Pt 340 °C

Co 20 °C

Co 200 °C

Ti -10 °C

Ti 50 °C

Ti 100 °C

Ti 150 °C

Ti 200°C

Sc 200°C

Y 200°C

Zr 200°C

Lu 200°C

Hf 200°C

La 200°C

Ce 200°C

Nd 200°C

Sm 200°C

Eu 200°C

Gd 200°C

Tb 200°C

Dy 200°C

Ho 200°C

Er 200°C

Tm 200°C

Yb 200°C

C 200°C |

[14] |

| 8. |

2H(d,p)3H |

80 eV |

191±12 eV

295±7 eV

302±3 eV

296 ± 15 eV

-20 ±5 eV |

AlD

ZrD2

TaD

PdD0.2

CD |

[17]

|

| 9. |

d(d,p)t |

39 eV |

600 ±20± 75 eV

310 ±20± 50 eV 200 ±15± 40 eV

70 ±10± 40 eV

65 ±10± 40 eV |

PdO

Pd

Fe

Au

Ti |

[18] |

| 10. |

d(d,p)t, 2H(d,n)3He |

80 eV |

190±15 eV

297±8 eV

322±15 eV |

Al

Zr

Ta |

[19] |

| 11. |

2H(d,p)3H |

80 eV |

105 ± 15 eV |

|

[20], [21] |

| 12. |

d(d,n)3He |

80 eV |

205 ± 35 eV

125 ± 34 eV

313 ± 58 eV |

ZrD2

TiD2

TaD0.5

|

[28] |

| 13. |

D(3He,p)4He

3He(d,p)4He

|

65 eV |

123 ± 9 eV

186± 9 eV |

combined analysis, including [2,30] |

[29] |

| 14. |

3He(d,p)4He |

65 eV |

120±10 eV |

d2 gas target |

[2] |

| 15. |

3He(d,p)4He |

120 eV |

66±4 eV |

|

[2] |

| 16. |

3He(3He,2p)4He |

240 eV |

294±47 eV |

|

[31], [32] |

| 17. |

3He(d,p)4He |

120 eV |

177 ± 29 eV |

|

[33] |

| 18. |

D(3He,p)4He |

65 eV |

132±9 eV |

|

[34] |

| 19. |

3He(d,p)4He |

120 eV |

219±7 eV |

|

[36] |

| 20. |

D(3He,p)4He |

65 eV |

109±9 eV |

|

[36] |

| 21. |

2H(d,p)3H |

14 eV |

13.4 ± 0.6 eV |

THM |

[38] |

| 22. |

2H(d,n)3He |

14 eV |

11.7 ± 1.6 eV |

THM |

[38] |

| 23. |

6Li(p,α)3He 7Li(p,α)4He |

240 eV |

300 eV

210 eV |

LiF |

[42] |

| 24. |

6Li(p,α)3He |

240 eV |

440±150 eV

470±150 eV |

molecular target

LiF |

[30] |

| 25. |

6Li(d,α)4He |

240 eV |

330±120 eV

380±250 eV |

molecular target

LiF |

[30] |

| 26. |

7Li(p,α)4He |

240 eV |

300±160 eV

300±280 eV |

molecular target

LiF |

[30] |

| 27. |

6Li(p,α)3He |

240 eV |

470 ± 150 eV

440 ± 150 eV |

atomic target

molecular target |

[43] |

| 28. |

6Li(d,α)4He |

240 eV |

380 ± 250 eV

330 ± 120 eV |

atomic target

molecular target |

[43] |

| 29. |

7Li(p, α)4He |

240 eV |

300± 280 eV

300 ± 160 eV |

atomic target

molecular target |

[43] |

| 30. |

2H(6Li,α)4He

|

240 eV |

320±50 eV |

THM |

[44] |

| 31. |

6Li(d,α)4He

|

240 eV |

130±20 eV |

|

[45] |

| 32. |

6,7Li(d,α)4,5He |

240 eV |

1500± 310 eV

60± 150 eV |

PdLix

AuLix

|

[46] |

| 33. |

7Li(p,α)4He |

240 eV |

1280±60 eV

3790±330 eV

185±150 eV |

Li

PdLi1%

Li2WO4

|

[48] |

| 34. |

6Li(p,α)3He |

240 eV |

320 ± 110

1320 ± 70

3760 ±260 |

Li2WO4

Li

PdLi1%

|

[48] |

| 35. |

7Li(p,α)4He,

reanalysis |

240 eV |

3680 ± 330 eV

1180 ± 60 eV |

Pd94.1%Li5.9%.

Li |

[47] |

| 36. |

6Li(p,α)3He,

reanalysis |

240 eV |

3710 ± 185 eV

1280 ± 70 eV |

Pd94.1%Li5.9%

Li |

[47] |

| 37. |

1H( 7Li, α)4He |

240 eV |

< 600 eV

< 300 eV

1900 ± 600 eV

2800 ± 700 eV |

Kapton

Pd (no tensile stress)

Pd (tensile stress applied)

Pd77Ag23(tensile stress applied) |

[50] |

| 38. |

1H(7Li,α) 4He |

240 eV |

4100 ± 100 eV

2400 ± 100 eV

2300 ± 500 eV

2800 ± 1300 eV |

Ni

Zn

Pd

Pt |

[51] |

| 39. |

11B(p,α)8Be |

340 eV |

430 ± 80 eV |

|

[52] |

| 40. |

11B(p,α0)8Be |

340 eV |

472 ±160 eV |

THM |

[53] |

| 41. |

10B(p,α0)7Be |

340 eV |

240 ± 200 eV |

THM |

[54] |

| 42. |

9Be(p,α)6Li, 9Be(p,d)8Be |

240 eV |

900 ±50 eV |

|

[49] |

| 43. |

9Be(p,α)6Li |

240 eV |

545 ±98 eV |

|

[55] |

| 44. |

9Be(p,α)6Li |

240 eV |

676 ±86 eV |

THM |

[56], [57] |

| 45. |

50V(p,n)50Cr |

11 ± 2 keV*

17 ± 2 keV*

*Debye model |

27 ± 9 keV (relative to VO2)

34 ± 11 keV(relative to VO2) |

V

PdV10%

|

[58] |

| 46. |

176Lu(p,n)176Hf |

*A shift in Lewis peak was observed |

32±2 keV(relative to VO2)

33±2 keV (relative to VO2)

|

V

PdV10%

|

[58] |

| 47. |

55Mn(p, γ)56Fe, 55Mn(p, n)55Fe, 113Cd(p, n)113In,

115In(p, n)115Sn 50V(p, n)50Cr

51V(p, γ)52Cr |

*no shift in resonance energy |

|

/

/

/

/

/

|

[51] |

| 48. |

1H( 7Li,α)4He |

240 eV |

2.86±0.19 keV |

hard Pd foil |

[62] |

| 49. |

1H(19F,αγ)16O |

2.19 keV |

18.7±1.5 keV |

hard Pd foil |

[62] |

| 50. |

2H(19F,p)20F |

2.19 keV |

18.2±3.3 keV

3.2 ±1.9 keV |

hard Pd foil

soft Pd foil |

[62] |