1. Introduction

Optimization plays a crucial role in various domains such as smart homes [

1,

2], finance [

3,

4], transportation [

5,

6], and solar energy systems [

7,

8,

9]. Recently, learning models have shown promising abilities to solve complex optimization problems. Among them, Most recent studies in Federated Learning (FL) have been focusing on designing optimization algorithms with proven convergence guarantee for such a finite-sum objective

where

N is the number of clients in a network and

is the expected loss of prediction of client

i given the model parameter

and data distribution

[

10]. However, as [

11] pointed out, naively minimizing the aggregate loss function may create disparities of model performance (i.e. prediction accuracy) across different clients. For example, it could result in overfitting a model to one client at the cost of another. In that case, the prediction accuracy would be higher for some clients over the others because more data is contributed by those clients to train the model. To better describe the issue, [

11] define

fairness of performance distribution as the uniformity of model performance across devices. A trained model

w is

fairer than model

if the performance of model

w on the

N devices is more

uniform than that of model

.

Inspired by the

-fairness function in resource allocation of wireless networks, [

11] propose an optimization objective called

q-Fair Federated Learning (

q-

FFL) that addresses the fairness issues, i.e. the disproportional model performance across devices. Unlike the objective in

,

q-

FFL penalizes the loss functions of devices with a tunable parameter

q, so that the model performance across clients in the network is pushed to be uniform in any desired extent.

The authors mentioned that with q-FFL as the optimization objective, FedAvg is no longer applicable to solve the problem, as the newly defined expected loss for client i, and thus the local SGD update in FedAvg (where ) cannot be used in the q-FFL setting.

But if we also change the loss function from to , and do local update as (where ), the new objective could still be fit in the FedAvg framework. (Notice that the equality is not true in general, so we need find a proper that satisfy this equality to make it work).

Assume we can find a suitable

, then we are able to prove that the convergence rate of

FedAvg on

q-

FFL is comparable with using the same algorithm on the original finite-sum objective. Notice that following the standard assumptions on the objective function

,

12] have shown that

FedAvg for non-convex optimization can achieve

. In this work, we show that the

q-Fair Federated Learning objective with a

FedAvg-like algorithm can maintain the

convergence using almost the same assumptions on

(instead of assumptions on

).

2. q-Fair Federated Learning and Its Performance Analysis

For non-negative cost function

and parameter

, the objective of

q-

FFL is defined as:

where

denote

raised to the power of

.

is the tunable fairness parameter. Notice that similar to the

-fairness framework, when

, no fairness will be imposed and problem

is reduced to problem

. When

, it corresponds to max-min fairness.

Table 1.

Notation summary.

Table 1.

Notation summary.

| q |

Fairness parameter |

| N |

The number of clients |

|

Set of data at client i

|

|

Example drawn from

|

|

Loss on example at client i with model parameter

|

|

Expected loss at client i with model parameter , i.e.

|

|

Expected q-FFL loss at client i with model parameter , i.e.

|

|

Objective function of federated learning, i.e.,

|

|

Objective function of q-fair federated learning, i.e.,

|

|

Stochastic gradient of on with example , i.e.,

|

|

|

Throughout this paper, we assume problem satisfies the following assumption.

Assumption 1. We assume that satisfies:

Smoothness: Each is smooth with modulus L, i.e., for any , .

Bounded variances and second moments: Assume that stochastic gradient

has bounded variance and second moments: There exists constant

and

such that

Bounded loss function: There exist such that , where is a non-empty compact set.

We assume the data is independent and identically distributed (IID). Each worker can compute unbiased stochastic gradients (on the last iteration solution

and data sample

given by

For simplicity, we denote the expected loss for device i by , i.e., and the expectation of the stochastic gradient is where denotes all the random samples used to calculate stochastic gradients up to iteration .

The

FedAvg-like algorithm with

q-

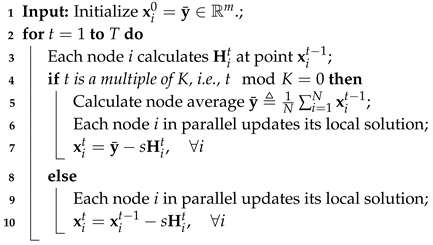

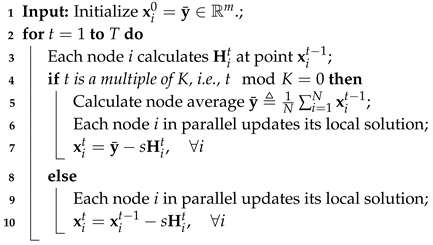

FFL objective is described in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1: FedAvg-like algorithm with q-Fairness. i is the client index, K is the number of local epochs and s is the learning rate. |

|

Algorithm 1 is essentially the same as

FedAvg described in [

13], except that the stochastic gradient

is computed on

, the expected loss for the newly defined

q-

FFL objective.

Fix iteration index

t, we define

as the average of local solution

over all

N nodes. It is immediate that

The proof starts from the descent lemma and the

L-smoothness assumption. Then we bound the generated quadratic term and cross term using the same technique from [

12]. And lastly, through a telescoping sum, we get an upper bound on the (average) expected square gradient norm. The following useful lemma relates client drift

and node synchronization interval

K.

Table 1 summarizes our notation.

Lemma 1: (Client drift) Under Assumption 1, the algorithm ensures

where

s is the constant stepsize,

are constant defined in Assumption 1, and

q is the fairness parameter.

Theorem 1. Under Assumption 1, if

in the Algorithm, then for all

, we have

where

is the minimum value of the problem.

Proof. From

L-smoothness and descent lemma:

Substituting

and

into

yields

Plugging

back into

and let

, we have

Dividing both sides of

by

and rearranging terms yields

Summing over

and dividing both sides by

T yields

□

The next corollary follows by substituting suitable values into Theorem 1.

Corollary 1. Consider the problem under Assumption 1. Let .

1. If we choose in the Algorithm, then we have .

2. If we further choose , then where is the minimum value of the problem.

With proper assumptions, FedAvg can achieve the same convergence rate on the objective of q-fair federated learning as the original objective.

3. Fair Incentive Mechanism Design Through Stackelberg Game Settings

Most of the studies in Federated Learning (FL) have been focused on convergence rate and stationary gap of optimization algorithms. However, designing mechanisms motivating local devices known as clients in terms of FL to collaborate in global model training has not received enough attention. [

14] devised an incentive mechanism in a Stackelberg game setting, and proved the existence of a unique Nash equilibrium.

In the first stage of a Stackelberg game, the parameter server (leader) strives to convince clients (followers) to participate in the training of a global model by declaring a total payment of

. Next in the second stage, participants decide about how much local data they are going to train. [

14] proved that for any

, the second-stage game has a unique Nash equilibrium, and furthermore, there exists a unique Stackelberg equilibrium for the game. The edge nodes also incur two costs, communication cost

and computation cost

given their training data set size

.

Based on works of [

14] and [

15], we add a fairness coefficient to the utility functions of clients in a federated learning incentive mechanism design with the hope that this additive term causes more fair allocation of resources to clients. [

15] argues that the global fairness of a model considers the full dataset across all clients while in local fairness performance measurement, data sets are typically non-iid. To address this issue, they propose a global and local fairness metric, i.e.,

Where

is a trained classifier and

A is a group, let’s say, gender group. The ideal amount of the above metric is zero meaning that the true positive rate of the above metric should be equal regardless of the gender, male or female. The local fairness metric is defined as:

Where C denotes the

client and for

,

clients data set and distribution have been considered [

15]. Furthermore, in FedAvg, [

13], we have weights when doing the conventional global updates, i.e.,

. Particularly, [

15] discusses that these naive aggregation weights disfavour clients with lower data set sizes and they propose the following modified version of aggregation weights to achieve global fairness as follows:

We adopted this approach and integrated it into the work of [

14]. Notations and proofs of the existence of Nash equilibrium in the modified version of this work have been demonstrated in what follows.

The utility of each client is modified by adding a fairness term to it, i.e.,

Where

. To maximize the utility of each client, we take the derivative of the utility function and put it equal to zero, i.e.,

To ensure that the answers to the above equation are not saddle points, we derive the second derivative w.r.t.

, i.e.,

This means that the utility function is strictly concave and the solutions are global optimal, i.e.,

However, there is a limitation on the amount of clients’ contributions, i.e., it cannot exceed

, and it depends also on the

, hence, we have:

Then, one can derive the best response from the followers, and clients, independent of other clients, as follows:

Then observe that,

Finally, considering the

client,

Observe that summing both sides of equations from 1 to M, yields:

implying that,

Finally, observe that:

So far, we have found the best responses of followers. At this point, the leader knows that whatever the payment is there exists a unique equilibrium, the leader strives to derive the maximum profit by best tuning

i.e.,

is the parameter serverer utility function as defined in [

14].

and we have that

And,

Hence, we have,

Given that

, we have,

Since

is a concave function and its value is equal to zero when

, then it has a unique maximize, and the proof is done.

4. Summary

In this project, we studied the fairness issue in federated learning. Two different notions of fairness were examined: fair (uniform) model performance across local clients and fair incentive mechanism. To achieve the first type of fairness, a novel optimization objective q-FFL was introduced. We tried to fit this federated learning task into the FedAvg framework and derived the convergence rate.

At first, we thought we had proven it by following a similar procedure from previous literature. However, after a careful examination of the new objective function, we realized that some parts in the proof procedure of [

12] cannot be used in this case due to the change of objective. For example, we do not know

when only knowing

. Therefore, we could not use SGD for a local update as in

FedAvg. Either we need more assumptions or find a suitable structure of

to make Theorem 1 hold.

As for the fairness in the incentive mechanism, we modeled the training process as a Stackelberg game where the server is treated as the leader and the clients are followers. Once the server announces a payment for training the global model, the followers decide the amount of data (and effort) they would like to contribute to the training task to maximize their payment. We have proven that the system could reach a unique Stackelberg equilibrium.

Appendix A

This part gives also an upper bound which is looser than the proved bounds above. The techniques used in this proof could be used whenever one would want to bind each loss function differently. Lipschitz coefficient is local and defined as follows at every point x:

[

11]. They further assume that step size is

for every local agent. Either considering such a dynamic Lipschitz coefficient or such a dynamic step size makes it super difficult to simplify all the above terms. What we assume is that we have a fixed stepsize s and Lipschitz constant defined at a point such as

Assumption 2. Let assume that the functions are bounded s.t. (This could be generalized to a specific bound on each loss function)

Due to the assumption 2, now we have client drift simplified as follows:

Previously, we showed that

We know that

Subsequently,

Observe that

Thereby,

Observe that now:

Now, we simplify

assuming that

. Since

, we have

, thus,

. Consequently, by removing the negative term, we obtain:

To simplify

, we use

. Observe that,

Due to the client drift, we have:

Rewriting

due to

and

, we obtain:

We rewrite

due to the above inequality, i.e.,

Then we know an upper bound for .

By iterating over t and dividing both sides by T we obtain the upper bound □

References

- Nematirad, R.; Ardehali, M.; Khorsandi, A.; Mahmoudian, A. Optimization of Residential Demand Response Program Cost with Consideration for Occupants Thermal Comfort and Privacy. IEEE Access 2024. [CrossRef]

- Talebi, A. A multi-objective mixed integer linear programming model for supply chain planning of 3D printing. 2024. arXiv:2408.05213.

- Varmaz, A.; Fieberg, C.; Poddig, T. Portfolio optimization for sustainable investments. Annals of Operations Research 2024, pp. 1–26.

- Talebi, A.; Haeri Boroujeni, S.P.; Razi, A. Integrating random regret minimization-based discrete choice models with mixed integer linear programming for revenue optimization. Iran Journal of Computer Science 2024, pp. 1–15.

- Archetti, C.; Peirano, L.; Speranza, M.G. Optimization in multimodal freight transportation problems: A Survey. European Journal of Operational Research 2022, 299, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Talebi, A. Simulation in discrete choice models evaluation: SDCM, a simulation tool for performance evaluation of DCMs. 2024. arXiv:2407.17014.

- Nematirad, R.; Pahwa, A.; Natarajan, B. A Novel Statistical Framework for Optimal Sizing of Grid-Connected Photovoltaic–Battery Systems for Peak Demand Reduction to Flatten Daily Load Profiles. Solar. MDPI, 2024, Vol. 4, pp. 179–208.

- Nematirad, R.; Pahwa, A.; Natarajan, B.; Wu, H. Optimal sizing of photovoltaic-battery system for peak demand reduction using statistical models. Frontiers in Energy Research 2023, 11, 1297356. [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, S.; Talebi, A. Forecasting solar irradiance with geographical considerations: integrating feature selection and learning algorithms. Asian Journal of Social Science 2024, 8, 5.

- Talebi, A. Convergence Rate Analysis of Non-I.I.D. SplitFed Learning with Partial Worker Participation and Auxiliary Networks. Preprints 2024. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sanjabi, M.; Beirami, A.; Smith, V. Fair Resource Allocation in Federated Learning. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2020.

- Yu, H.; Yang, S.; Zhu, S. Parallel Restarted SGD with Faster Convergence and Less Communication: Demystifying Why Model Averaging Works for Deep Learning. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2019, 33, 5693–5700. [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. Artificial intelligence and statistics. PMLR, 2017, pp. 1273–1282.

- Zhan, Y.; Li, P.; Qu, Z.; Zeng, D.; Guo, S. A Learning-Based Incentive Mechanism for Federated Learning. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 7, 6360–6368. [CrossRef]

- Ezzeldin, Y.H.; Yan, S.; He, C.; Ferrara, E.; Avestimehr, S. Fairfed: Enabling group fairness in federated learning. 2021. arXiv:2110.00857.

- Karimireddy, S.P.; Kale, S.; Mohri, M.; Reddi, S.; Stich, S.; Suresh, A.T. Scaffold: Stochastic controlled averaging for federated learning. International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2020, pp. 5132–5143.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).