Submitted:

04 September 2024

Posted:

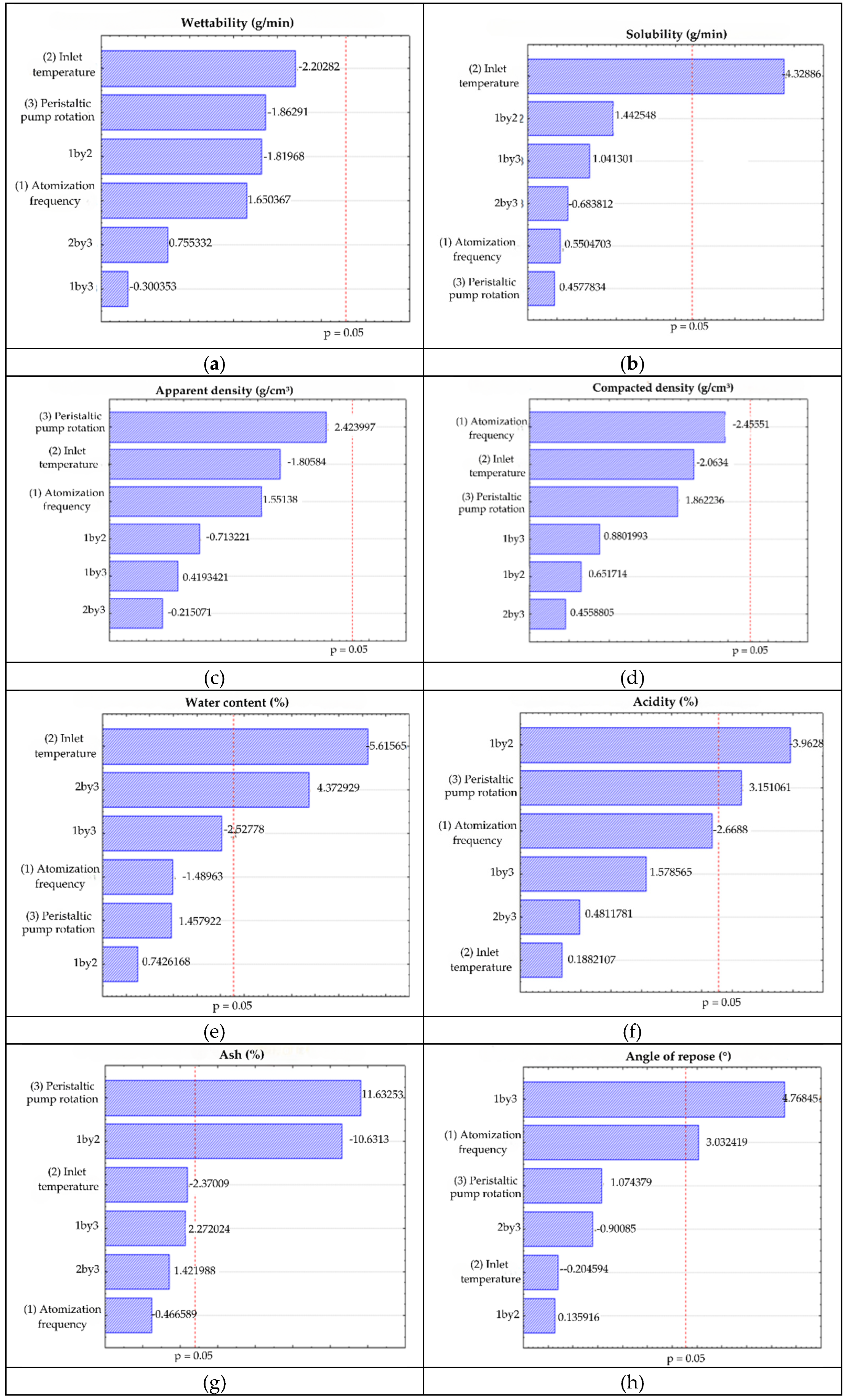

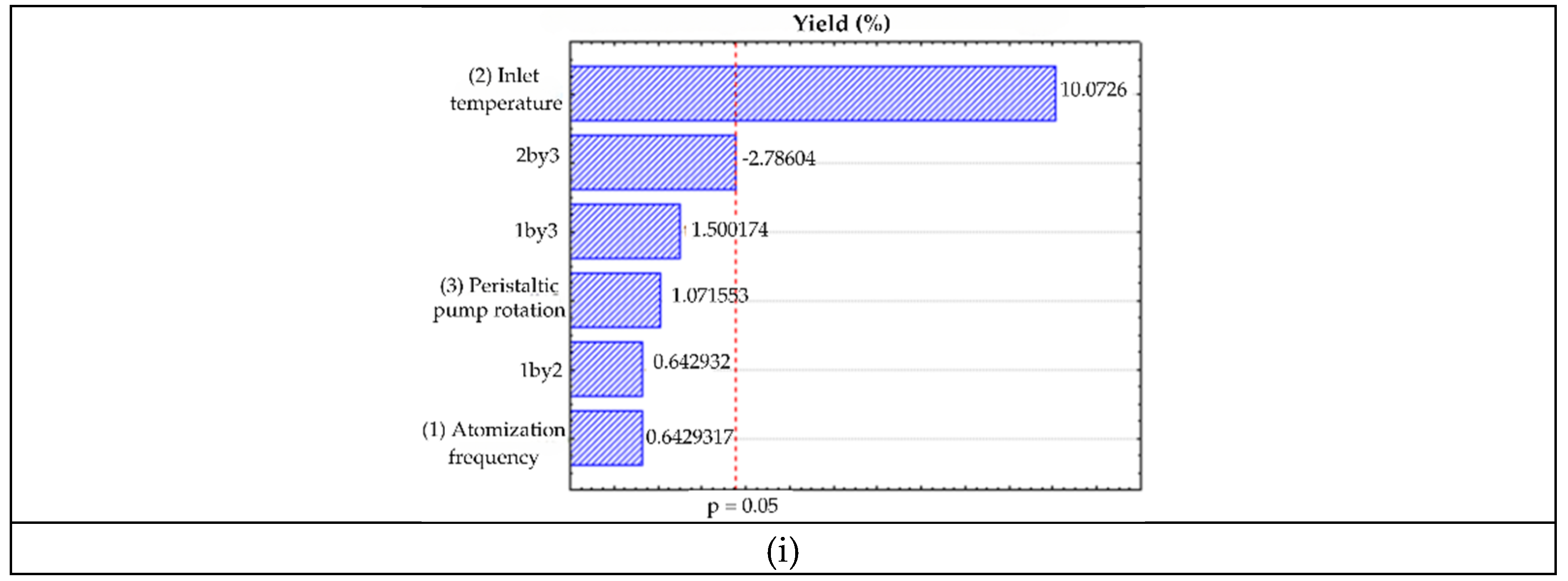

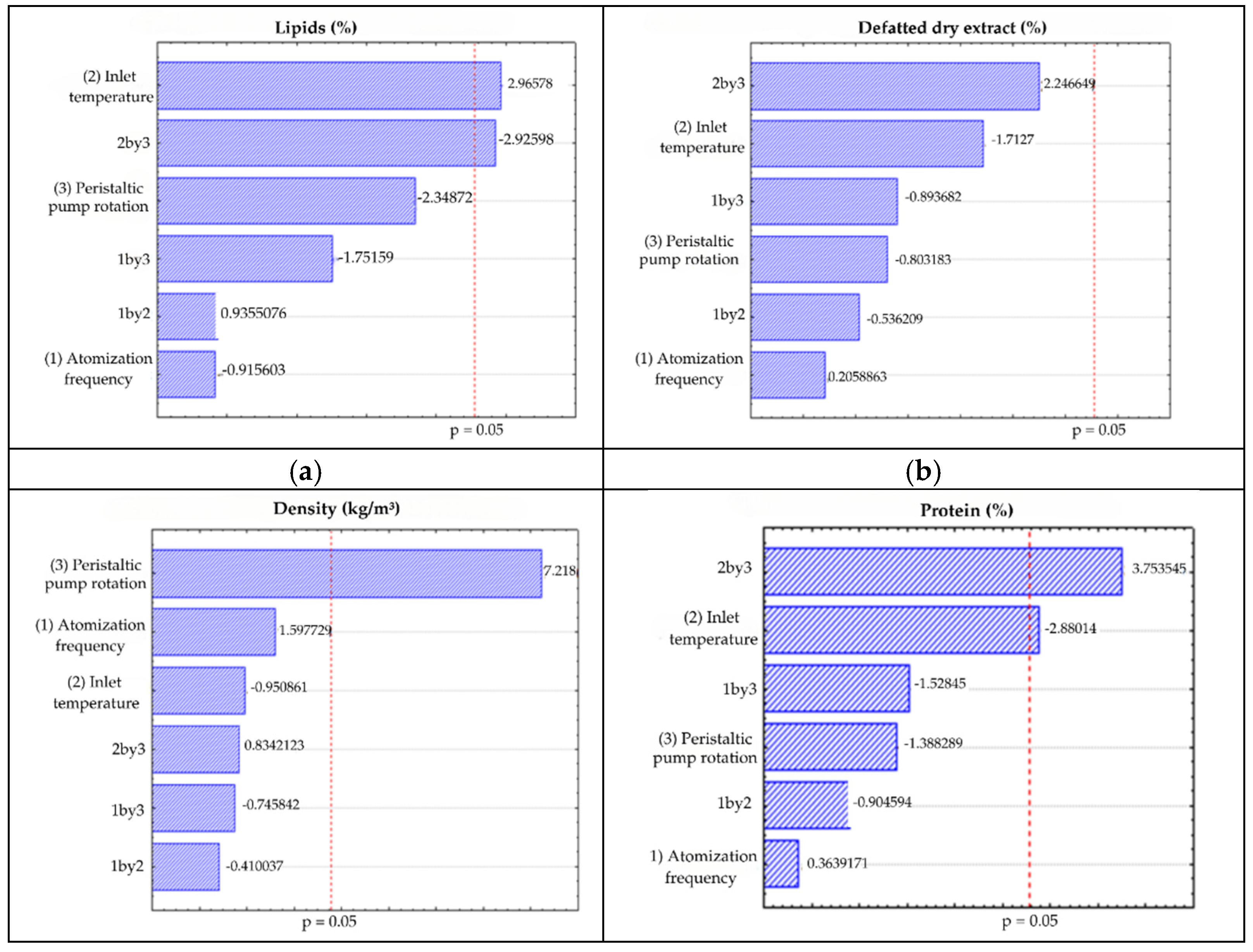

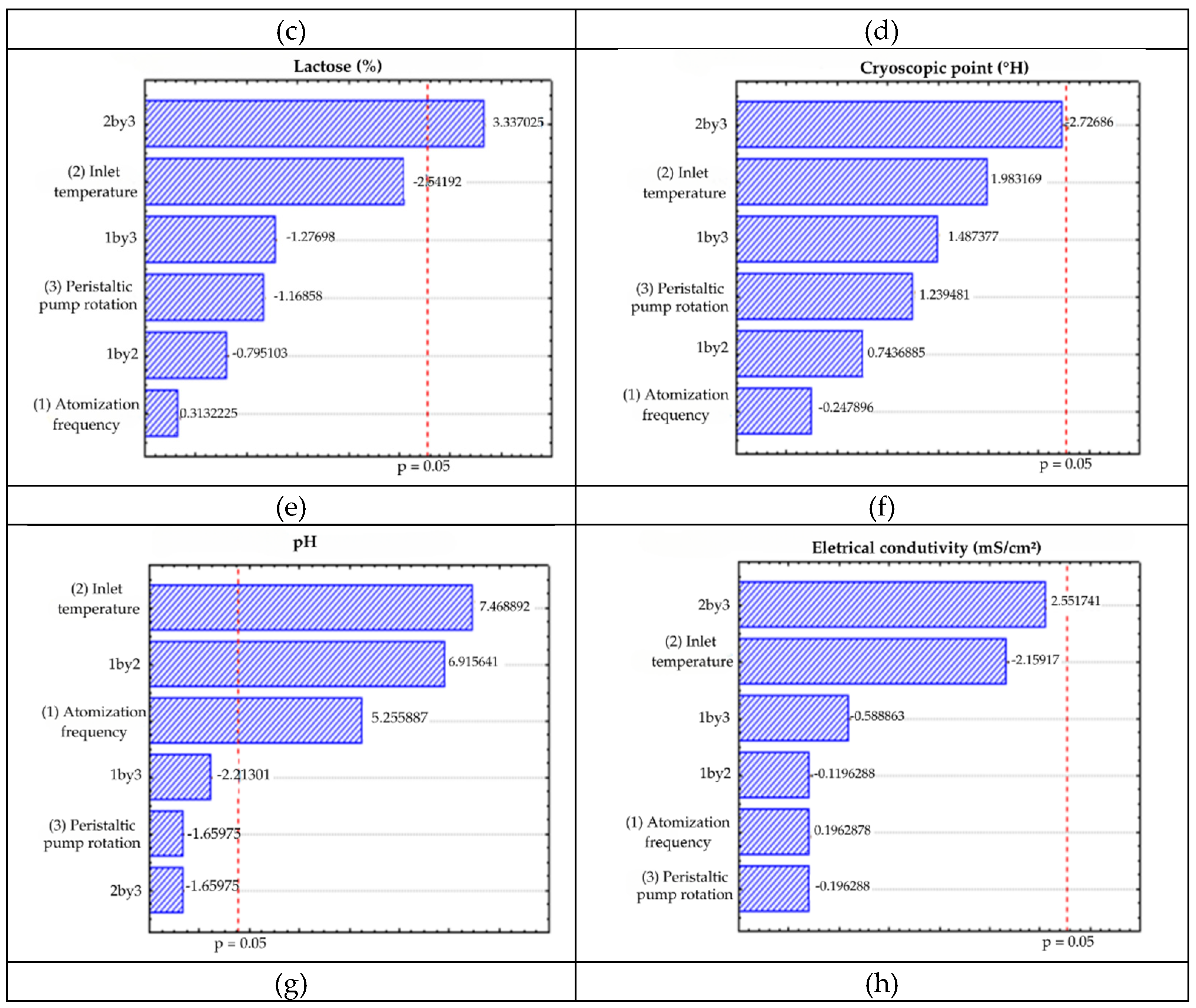

05 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Drying

2.3. Physicochemical Analyses

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- SEBRAE Mercado de Caprinos: Produtos e Serviços Demandados. Available online: https://respostas.sebrae.com.br/mercado-de-caprinos-produtos-e-servicosdemandados/ (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- IBGE -Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística Censo Agropecuário 2006 e 2017. Available online: https://sidra.ibge.gov.br (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Wang, L.; Ren, C.; You, J.; Fan, Y.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Huang, M. A Novel Fluorescence Reporter System for the Characterization of Dairy Goat Mammary Epithelial Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 458, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.V.Í.; Lima Junior, A.C.; Araújo, T.G.P.; Farias, B.J.P.; Lisboa, A.C.C. Avaliação Da Qualidade Do Leite de Cabra Em Uma Propriedade No Município de Monteiro - Pb. Rev. Craibeiras Agroecol. 2019, 4, e7682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, K.M.; Gomes, V.; Saraújo, W.P. Características Físico-Químicas e Celulares Do Leite de Cabras Saanen, Alpina e Toggenburg. Rev. Bras. Ciência Veterinária 2017, 24, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, E. de F.M.; Lopes, L. de L.; Alves, S.M. de F.; Campos, A.J. de Efeito Da Maltodextrina No Sumo Da Polpa de Abacaxi Pérola Atomizado. Rev. Ciências Agrárias 2019, 42, 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, W.E. da S.; Lira, E. da S.; Alves, A.J.L.; Cavalcante, J. de A.; Romão, T.D.; Moreira, M.F.; Ribeiro Neto, E.N. Estudo Da Distribuição de Ar Em Secador e Influência Na Qualidade Do Produto Seco. Brazilian J. Dev. 2020, 6, 49857–49864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys, W.L.; Verraes, C.; Cardoen, S.; De Block, J.; Huyghebaert, A.; Raes, K.; Dewettinck, K.; Herman, L. Consumption of Raw or Heated Milk from Different Species: An Evaluation of the Nutritional and Potential Health Benefits. Food Control 2014, 42, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, E.S.; Lopes Rezende, A.L.; Perrone, Í.T.; Francisquini, J. d. A.; Fernandes de Carvalho, A.; Germano Alves, N.M.; Cappa de Oliveira, L.F.; Stephani, R. Spray Drying and Characterization of Lactose-Free Goat Milk. LWT 2021, 147, 111516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.H.; Mata, M.E.R.M.C.; Fortes, M.; Duarte, M.E.M.; Pasquali, M.; Lisboa, H.M. Influence of Spray Drying Conditions on the Properties of Whole Goat Milk. Dry. Technol. 2021, 39, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Adolfo Lutz 1a Edição Digital. Métodos físicos-quimicos para análise Aliment. 2008.

- Furtado, M.M. Fabricação de Queijo de Leite de Cabra, 6th ed.; Nobel: São Paulo, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.W.; Haenlein, G.F.W. Handbook of Milk of Non-Bovine Mammals; 2008; ISBN 0813820510.

- Brasil Instrução Normativa No 37, de 31 de Outubro de 2000. Available online: https://sidago.agrodefesa.go.gov.br/site/adicionaisproprios/protocolo/arquivos/408781.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Amaral, D.S. do; Amaral, D.S. do; Neto, L.G. de M. Tendências de Consumo de Leite de Cabra: Enfoque Para a Melhoria Da Qualidade. Rev. verde Agroecol. e Desenvolv. sustentável 2011, 6, 39–42.

- Silva, M. da C.M. da; Santana,; Yânez André Gomes; Melo, S.S.; Leal, N.; R.G.F. Elaboração, Caracterização e Avaliação de Kefir à Base de Leite de Cabra. PUBVET 2012, 6, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, A.M.; da Cruz, G.R.B.; da Costa, R.G.; Ribeiro, N.L.; Beltrão Filho, E.M.; de Sousa, S.; Justino, E. da S.; Dos Santos, D.G. Physical-Chemical and Microbiological Quality of Milk and Cheese of Goats Fed with Bidestilated Glycerin. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 41, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, F.S.; Couto, E.P.; Nero, L.A.; De Aguiar Ferreira, M. Physical Chemical and Microbiological Quality of Goat Milkproduced in Distrito Federal. Cienc. Anim. Bras. 2019, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.W. da; F.; Sidnei A Importância Econômica Da Criação De Cabra Leiteira the Economic Importance of Dairy Goat Breeding for Rural Development. 2020, 22, 46–53.

- Oliveira, K.A.M.; Jardim, D.M.; Chaves, K.S.; Oliveira, G.V.; Vidigal, M.C.T.R. Avaliação Físico-Química, Microbiológica E Sensorial De Queijo Minas Frescal De Leite De Cabra Desenvolvido Por Acidificação Direta E Fermentação Lática. Rev. do Inst. Laticínios Cândido Tostes 2016, 71, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzzi, A.Z.; Monreal, A.C.D.; Caramalac, S.M.; Caramalac, S.M. Avaliação Da Produção Leiteira e Análise Centesimal Do Leite de Ovelhas Da Raça Santa Inês. Agrarian 2016, 9, 182–191. [Google Scholar]

| Levels | Atomization Frequency (Hz) | Inlet temperature (°C) | Peristaltic pump rotation (rpm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| -1 | 300 | 160 | 60 |

| 0 | 400 | 180 | 70 |

| +1 | 500 | 200 | 80 |

| Assays | Atomization Frequency (Hz) | Inlet temperature (°C) | Peristaltic pump rotation (rpm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (-1) 300 | (-1) 160 | (-1) 60 |

| 2 | (+1) 500 | (-1) 160 | (-1) 60 |

| 3 | (-1) 300 | (+1) 200 | (-1) 60 |

| 4 | (+1) 500 | (+1) 200 | (-1) 60 |

| 5 | (-1) 300 | (-1) 160 | (+1) 80 |

| 6 | (+1) 500 | (-1) 160 | (+1) 80 |

| 7 | (-1) 300 | (+1) 200 | (+1) 80 |

| 8 | (+1) 500 | (+1) 200 | (+1) 80 |

| 9 | (0) 400 | (0) 180 | (0) 70 |

| 10 | (0) 400 | (0) 180 | (0) 70 |

| 11 | (0) 400 | (0) 180 | (0) 70 |

| Parameters | Obtained values | Standard * |

|---|---|---|

| Water content (%) | 87.90 | 87.50 |

| Proteins (%) | 3.36 | Minimum 2.80 |

| Lipids (%) | 3.50 | Around 2.90 |

| Ash (%) | 0.71 | Minimum 0.70 |

| Carbohydrates (%) | 20.06 | --** |

| pH | 6.45 | 6.45 |

| Acidity (%) | 0.14 | 0.13 a 0.18 |

| Lactose (%) | 5.00 | Minimum 4.30 |

| Non-fat solids (%) | 8.39 | Minimum 8.20 |

| Specific mass (kg/m³) | 1028.82 | 1028-1034 |

| Eletrical conductivity (mS/cm²) | 5.32 | --** |

| Cryoscopic point (°H) | -0.570 | -0.550 a 0.585 |

| Assays | Wett. (g/min) |

Solub. (g/min) |

Apaar. Dens (g/cm³) |

Comp. Dens. (g/cm³) |

Water content (%) |

Acidity (%) | Ash (%) | Rest Angle (°) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.15 | 1.82 | 0.23 | 0.46 | 4.41 | 1.15 | 4.37 | 21.06 | 25 |

| 2 | 0.18 | 1.22 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 4.49 | 1.12 | 4.53 | 20.93 | 24 |

| 3 | 0.16 | 0.72 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 2.77 | 1.18 | 4.51 | 21.56 | 40 |

| 4 | 0.13 | 1.16 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 2.99 | 1.08 | 4.24 | 20.79 | 39 |

| 5 | 0.14 | 1.54 | 0.31 | 0.52 | 4.38 | 1.14 | 4.53 | 20.69 | 27 |

| 6 | 0.16 | 1.86 | 0.27 | 0.45 | 3.59 | 1.21 | 4.76 | 22.32 | 31 |

| 7 | 0.12 | 0.81 | 0.25 | 0.45 | 4.03 | 1.24 | 4.71 | 20.02 | 29 |

| 8 | 0.14 | 1.00 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 3.55 | 1.13 | 4.55 | 22.42 | 28 |

| 9 | 0.16 | 1.33 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 3.51 | 1.15 | 4.53 | 21.28 | 34 |

| 10 | 0.16 | 1.36 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 3.48 | 1.15 | 4.58 | 21.64 | 35 |

| 11 | 0.16 | 1.43 | 0.24 | 0.42 | 3.44 | 1.15 | 4.53 | 21.66 | 35 |

| Assays | Lipidis (%) | NFS (%) | Density (kg/m³) | Protein (%) | Lactose (%) | Cryoscopic point (°H) | pH | Eletrical condutivity (mS/cm²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.21 | 10.28 | 1031.98 | 3.79 | 5.64 | -0.68 | 6.26 | 5.07 |

| 2 | 3.05 | 10.64 | 1032.97 | 3.92 | 5.83 | -0.71 | 6.25 | 5.10 |

| 3 | 3.48 | 8.77 | 1031.03 | 3.24 | 4.80 | -0.58 | 6.27 | 4.87 |

| 4 | 3.78 | 9.23 | 1032.23 | 3.41 | 5.04 | -0.62 | 6.41 | 4.90 |

| 5 | 3.26 | 9.24 | 1035.04 | 3.41 | 5.06 | -0.61 | 6.27 | 4.97 |

| 6 | 3.11 | 9.43 | 1035.92 | 3.48 | 5.17 | -0.62 | 6.25 | 4.97 |

| 7 | 3.33 | 9.88 | 1035.47 | 3.64 | 5.41 | -0.66 | 6.27 | 5.00 |

| 8 | 3.04 | 9.18 | 1035.38 | 3.38 | 5.03 | -0.60 | 6.35 | 4.97 |

| 9 | 3.38 | 8.64 | 1034.61 | 3.52 | 5.06 | -0.60 | 6.28 | 4.90 |

| 10 | 3.27 | 9.88 | 1034.52 | 3.64 | 5.41 | -0.66 | 6.30 | 5.00 |

| 11 | 3.26 | 9.71 | 1034.69 | 3.70 | 5.49 | -0.66 | 6.29 | 5.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).