Submitted:

04 September 2024

Posted:

05 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

2.2. Electrodeposition of ZnO Nanostructures on ITO

2.3. Samples Characterisation

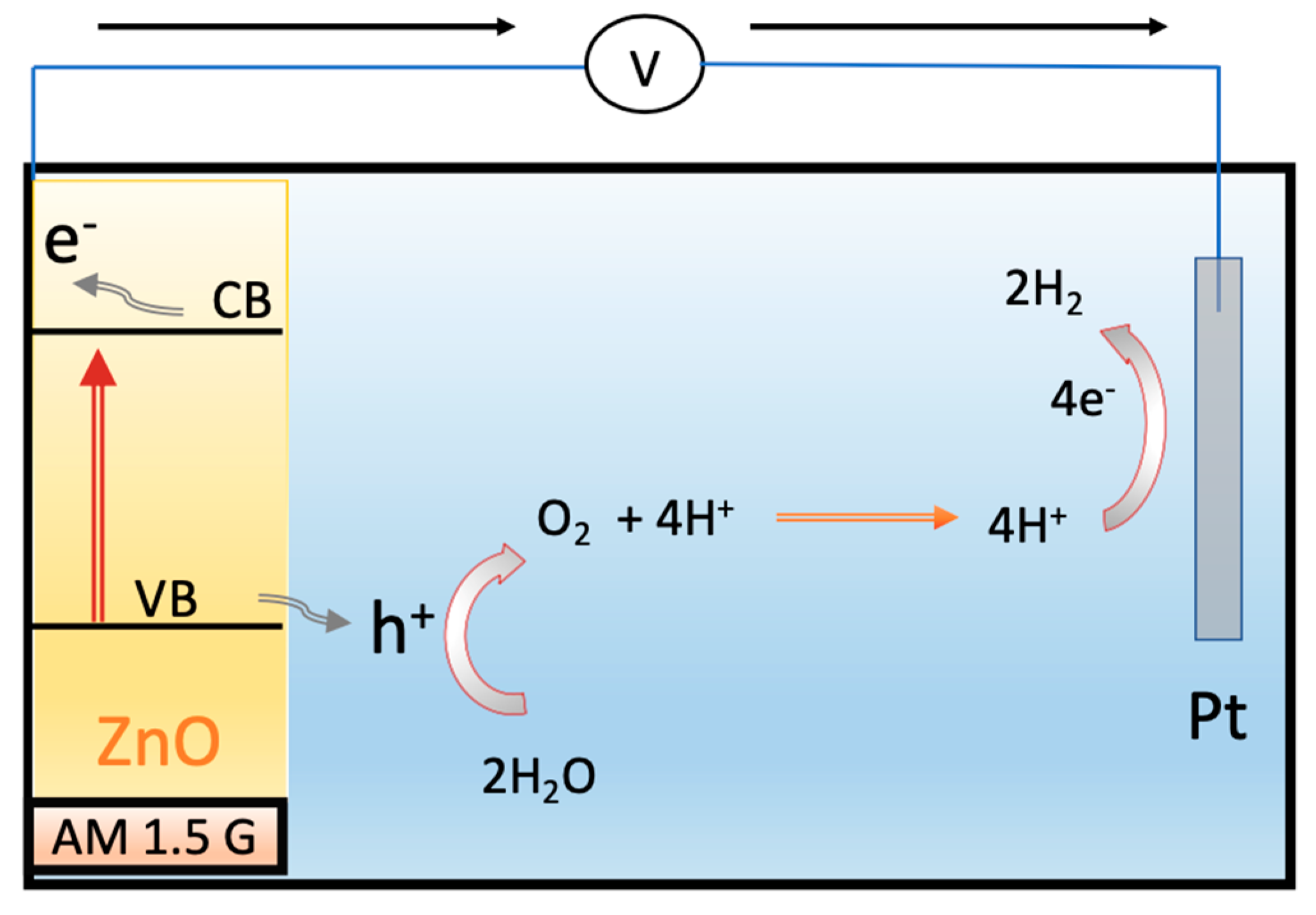

2.4. Photoelectrochemical Measurements (PEC)

3. Results and Discussion

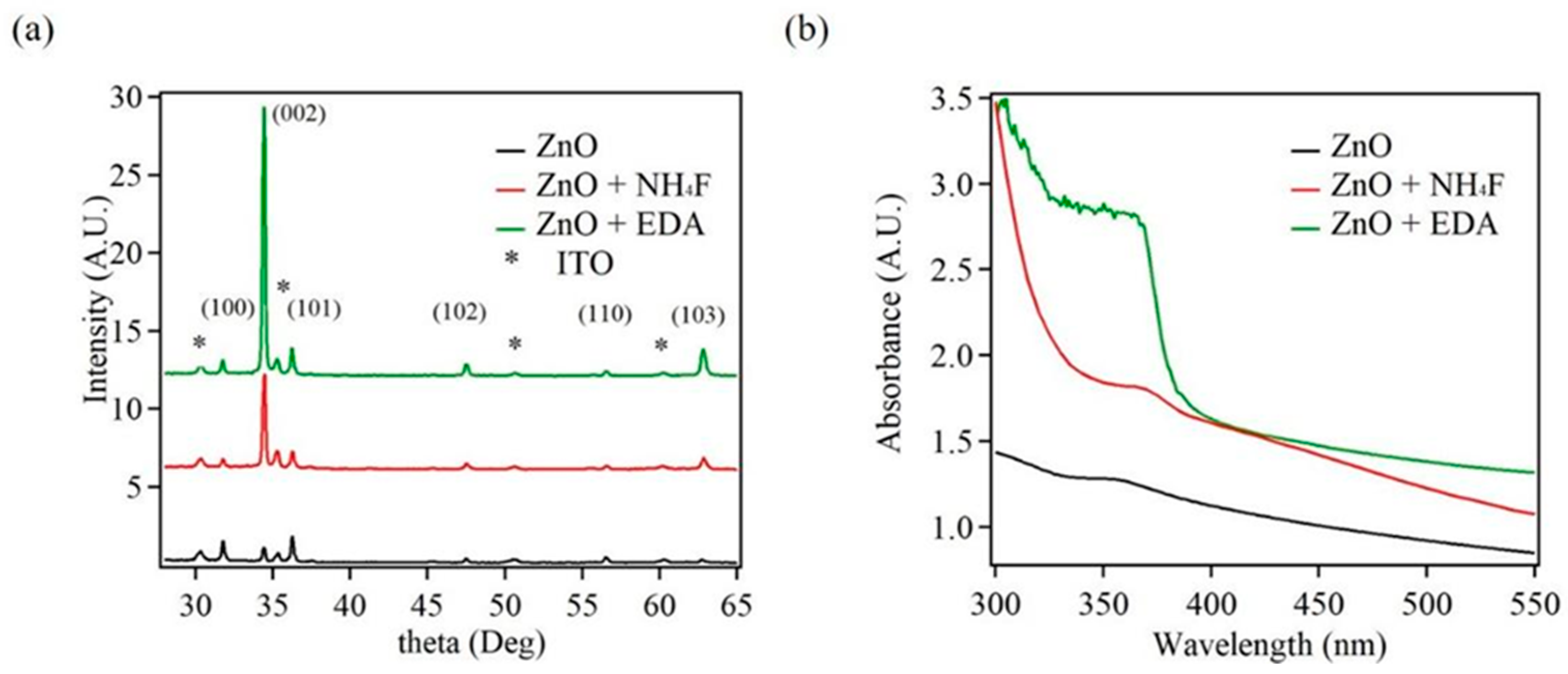

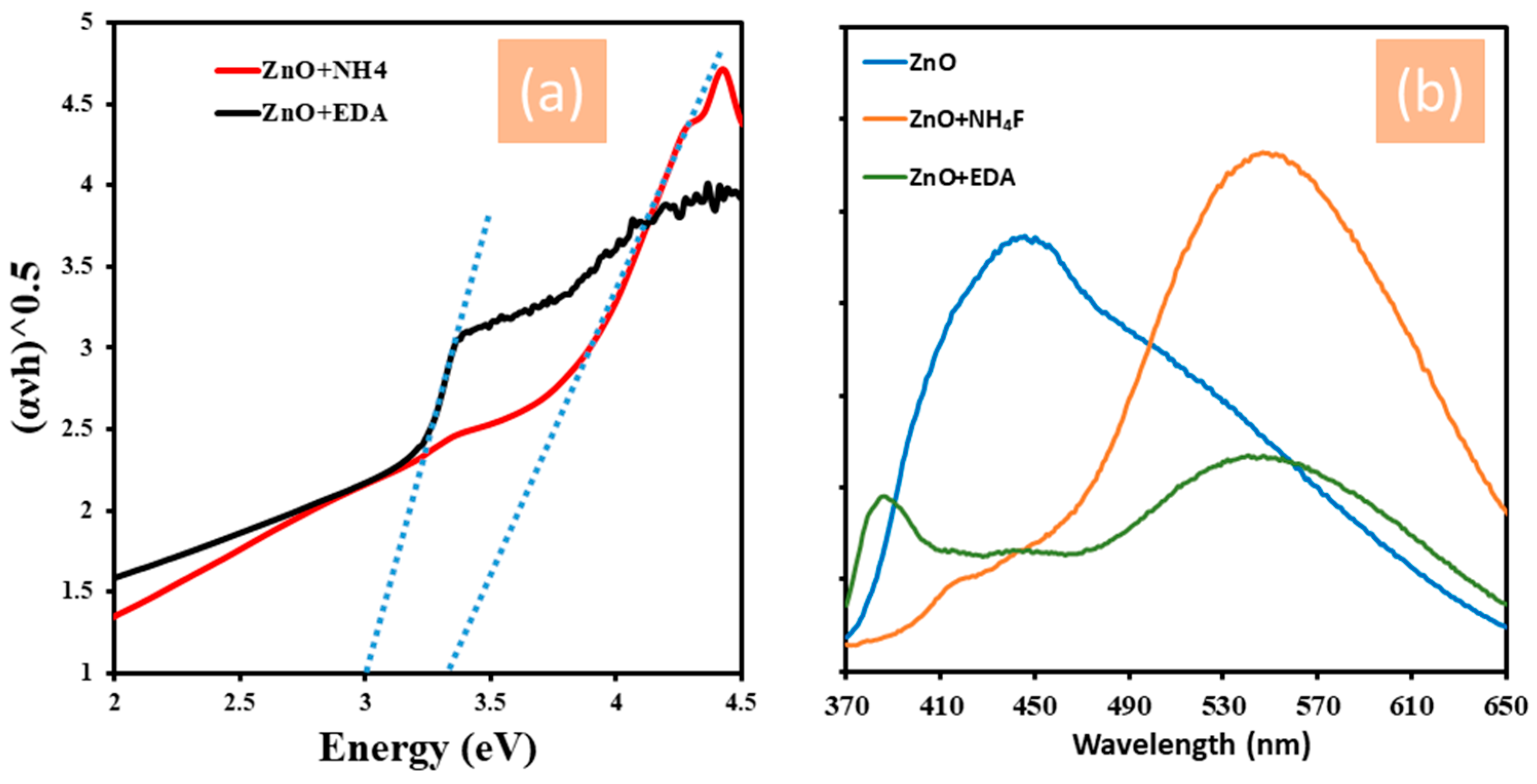

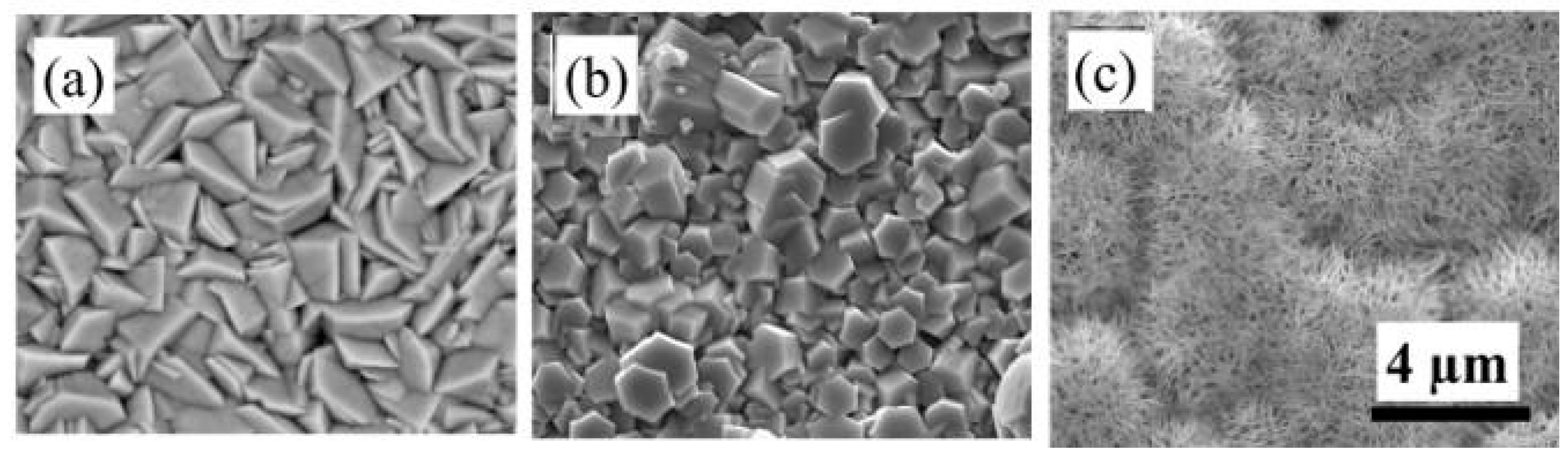

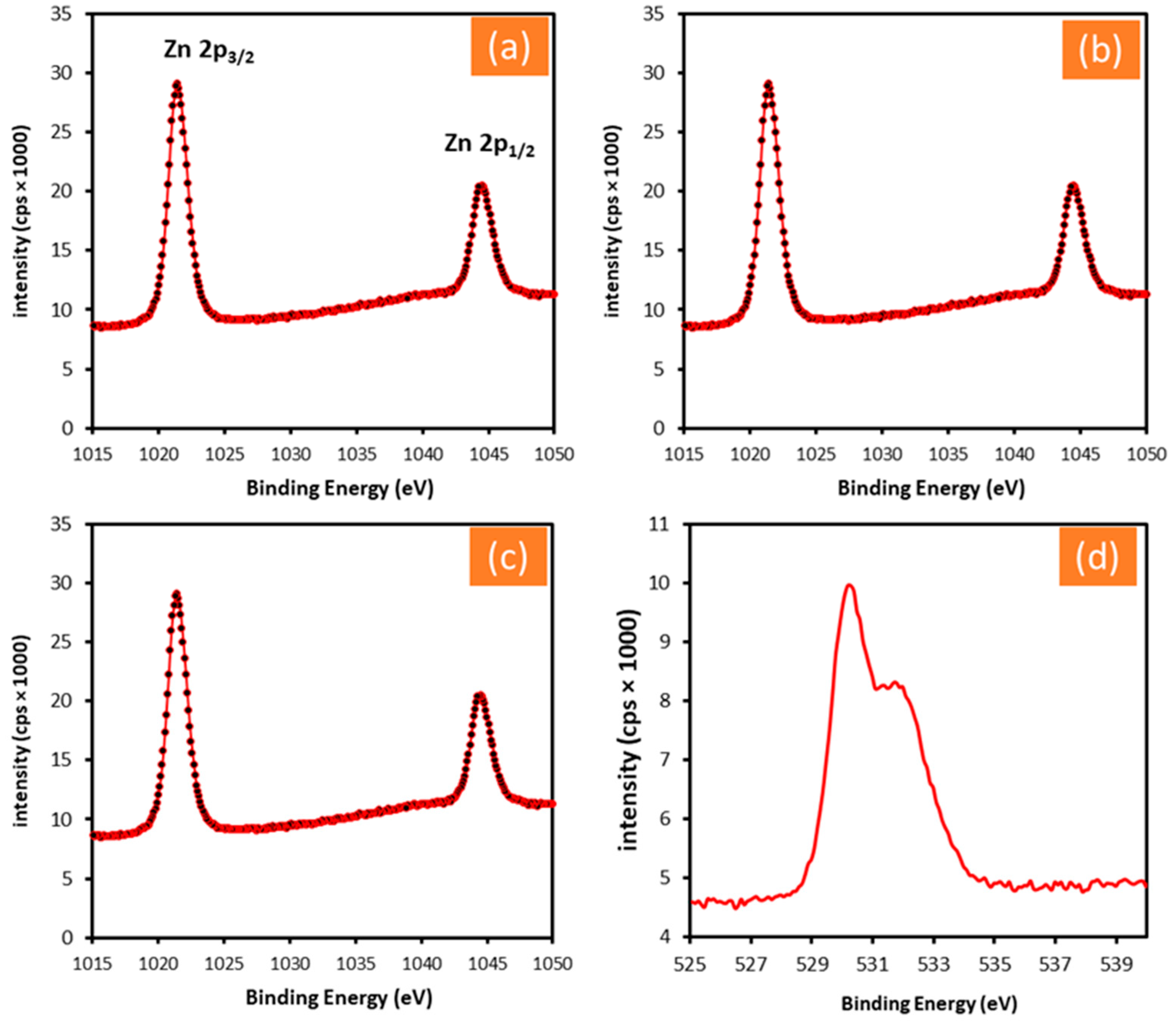

3.1. Characterization of the Fabricated ZnO Nanostructures

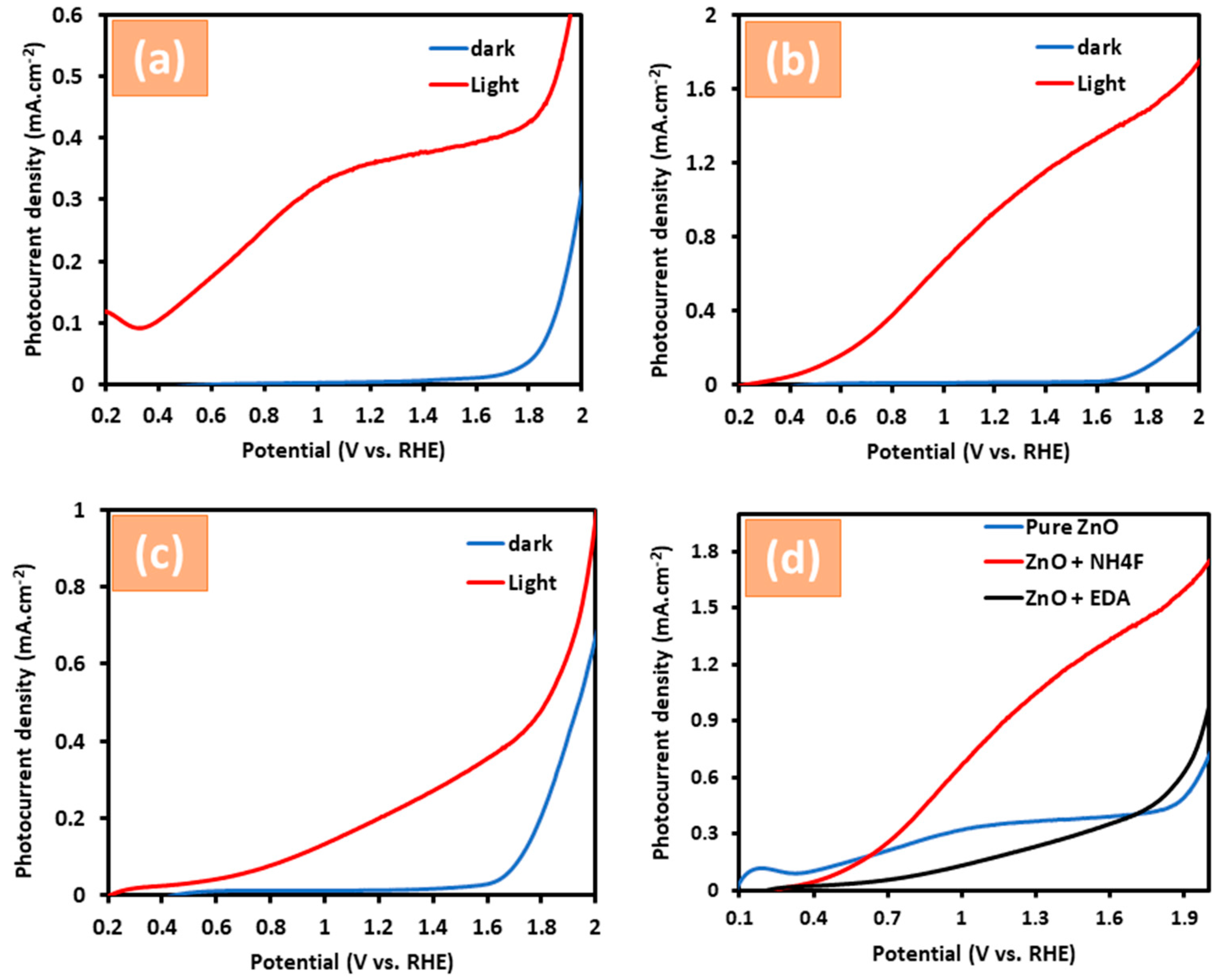

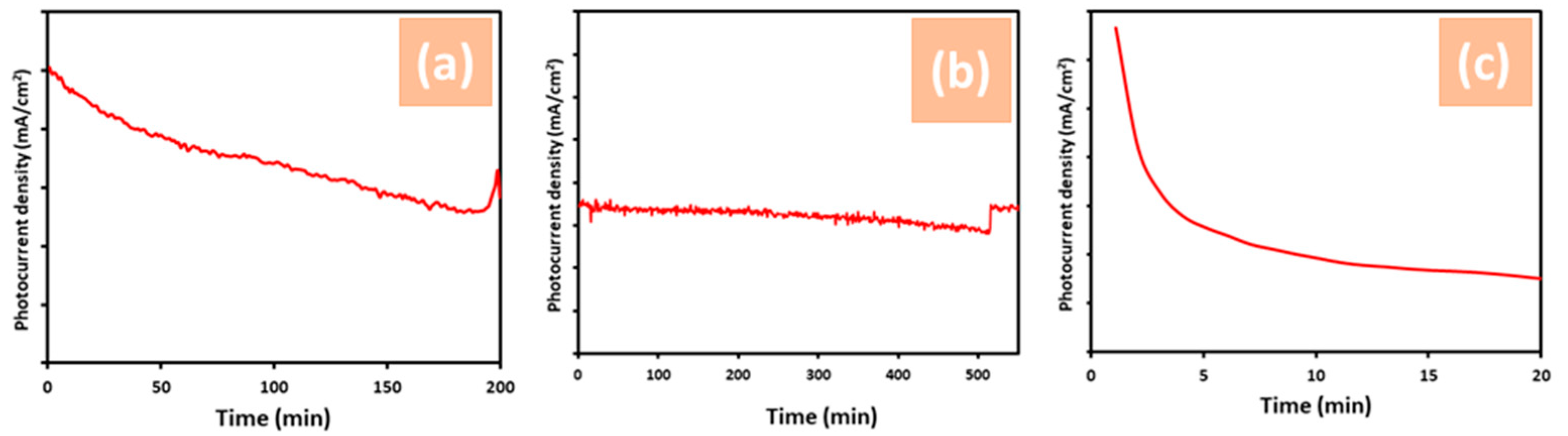

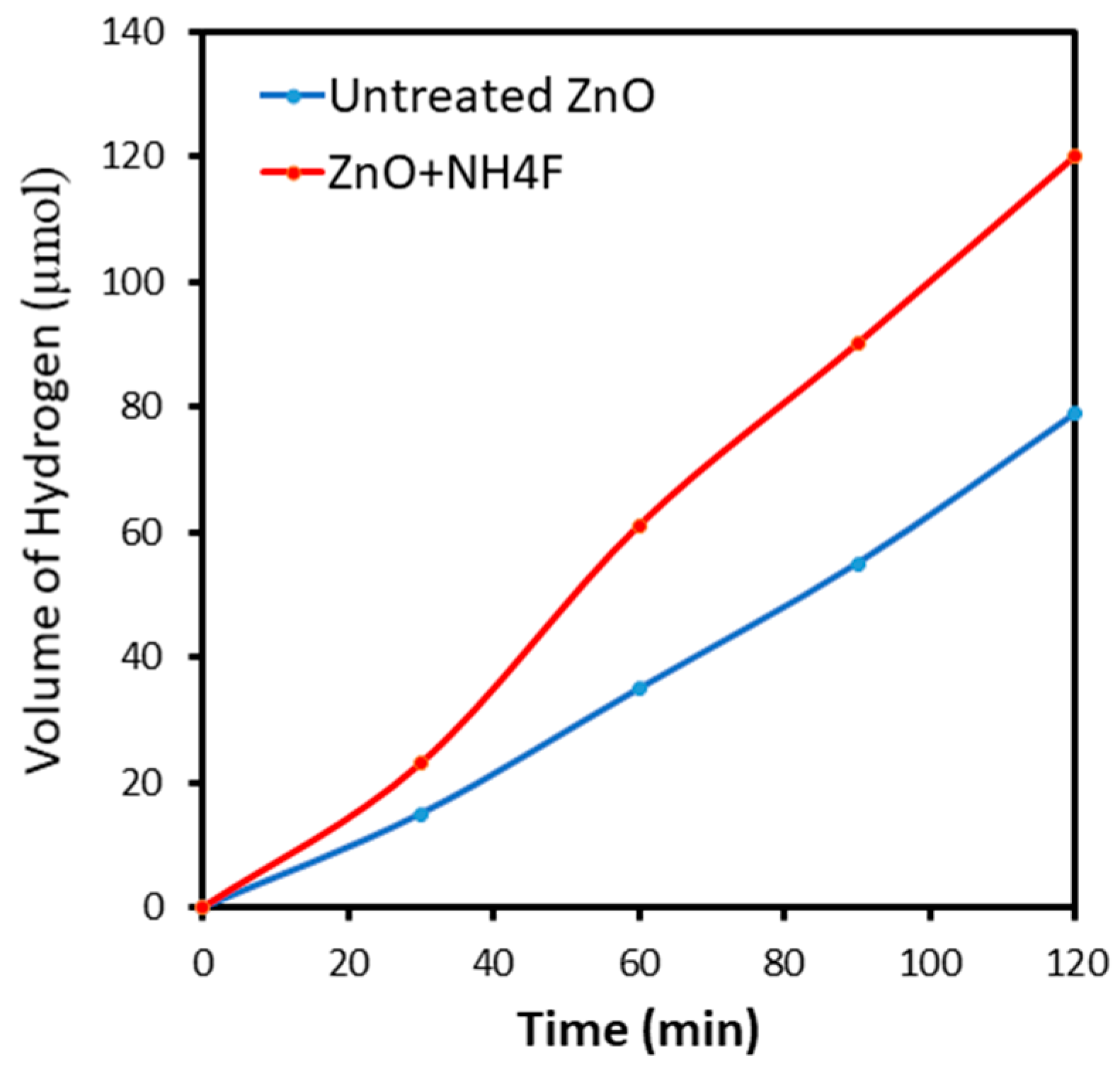

3.2. Photoelectrochemical Measurements of ZnO Nanostructures

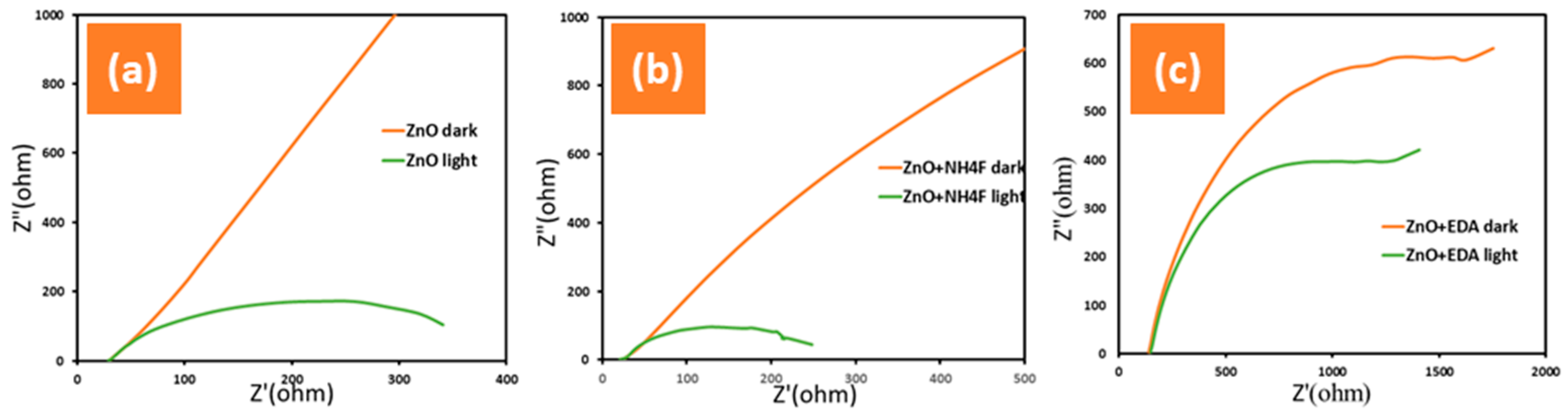

3.3. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Laufkötter, C.; Zscheischler, J.; Frölicher, T.L. High-impact marine heatwaves attributable to human-induced global warming. Science 2020, 369, 1621–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balch, J.K.; et al. Warming weakens the night-time barrier to global fire. Nature 2022, 602, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, T.; et al. Emergence of changing central-pacific and eastern-pacific El Niño-Southern Oscillation in a warming climate. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 6616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; et al. Challenges and opportunities for carbon neutrality in China. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2022, 3, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Lutkenhaus, J.L. Hydrogen power gets a boost. Science 2022, 378, 138–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; et al. Breaking the hard-to-abate bottleneck in China’s path to carbon neutrality with clean hydrogen. Nature Energy 2022, 7, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.J.; et al. Net-zero emissions energy systems. Science 2018, 360, eaas9793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Rajput, J.K. Nanostructured materials for the visible-light driven hydrogen evolution by water splitting: A review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 17544–17582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, K.; et al. Photocatalytic water splitting: advantages and challenges. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2021, 5, 4560–4569. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Bismuth-based complex oxides for photocatalytic applications in environmental remediation and water splitting: A review. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 804, 150215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, T.; et al. A perspective on possible amendments in semiconductors for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen generation by water splitting. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 39036–39057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallatah, A.; et al. Sensitive biosensor based on shape-controlled ZnO nanostructures grown on flexible porous substrate for pesticide detection. Sensors 2022, 22, 3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallatah, A.; et al. Influence of Morphology Change on Photoelectrochemical Activity of Cerium Oxide Nanostructures. Current Nanoscience 2023, 19, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; et al. Photocatalytic enhancement of hydrogen production in water splitting under simulated solar light by band gap engineering and localized surface plasmon resonance of ZnxCd1-xS nanowires decorated by Au nanoparticles. Nano Energy 2020, 67, 104225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameta, R.; Ameta, S.C. Photocatalysis: principles and applications. CRC Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tentu, R.D.; Basu, S. Photocatalytic water splitting for hydrogen production. Current Opinion in Electrochemistry 2017, 5, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; et al. A review and recent developments in photocatalytic water-splitting using TiO2 for hydrogen production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2007, 11, 401–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-F.; Muckerman, J.T.; Fujita, E. Recent developments in transition metal carbides and nitrides as hydrogen evolution electrocatalysts. Chemical Communications 2013, 49, 8896–8909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merki, D.; et al. Amorphous molybdenum sulfide films as catalysts for electrochemical hydrogen production in water. Chemical Science 2011, 2, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhundi, A.; et al. Graphitic carbon nitride-based photocatalysts: toward efficient organic transformation for value-added chemicals production. Molecular Catalysis 2020, 488, 110902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; et al. Efficient nonsacrificial water splitting through two-step photoexcitation by visible light using a modified oxynitride as a hydrogen evolution photocatalyst. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2010, 132, 5858–5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarello, G.L.; Dozzi, M.V.; Selli, E. TiO2-based materials for photocatalytic hydrogen production. Journal of energy Chemistry 2017, 26, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, M.; et al. Recent progress on doped ZnO nanostructures for visible-light photocatalysis. Thin Solid Films 2016, 605, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. Novel nanostructures and nanodevices of ZnO, in Zinc oxide bulk, thin films and nanostructures. Elsevier, 2006; pp. 339–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.-F.; et al. Vertically aligned one-dimensional ZnO/V2O5 core–shell hetero-nanostructure for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2020, 49, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayah, N.A.; et al. High electron mobility and low carrier concentration of hydrothermally grown ZnO thin films on seeded a-plane sapphire at low temperature. Nanoscale Research Letters 2015, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Guo, L. Metal sulphide semiconductors for photocatalytic hydrogen production. Catalysis Science & Technology 2013, 3, 1672–1690. [Google Scholar]

- Rokade, A.; et al. Electrochemical synthesis of 1D ZnO nanoarchitectures and their role in efficient photoelectrochemical splitting of water. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry 2017, 21, 2639–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallatah, A.; et al. Influence of Zinc Oxide Nanostructure Morphology on its Photocatalytic Properties. Current Nanoscience 2023, 19, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; et al. Band-structure tunability via the modulation of excitons in semiconductor nanostructures: manifestation in photocatalytic fuel generation. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 10939–10974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, E.; Paganini, M.C.; Giamello, E. Photoactivity under visible light of defective ZnO investigated by EPR spectroscopy and photoluminescence. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2020, 397, 112531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, A.; Sarswat, P.K.; Free, M.L. Minimizing electron-hole pair recombination through band-gap engineering in novel ZnO-CeO2-rGO ternary nanocomposite for photoelectrochemical and photocatalytic applications. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 25042–25056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; et al. Defect passivation scheme toward high-performance halide perovskite solar cells. Polymers 2023, 15, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahai, A.; Goswami, N. Probing the dominance of interstitial oxygen defects in ZnO nanoparticles through structural and optical characterizations. Ceramics International 2014, 40, 14569–14578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; et al. Effect of growth temperature on structural, electrical and optical properties of dual ion beam sputtered ZnO thin films. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2013, 24, 2541–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerathunga, H.; et al. Nanostructure shape-effects in ZnO heterogeneous photocatalysis. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2022, 606, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; et al. Synergetic effects of defects and acid sites of 2D-ZnO photocatalysts on the photocatalytic performance. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 385, 121527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, N.L.; et al. Superior solar-to-hydrogen energy conversion efficiency by visible light-driven hydrogen production via highly reduced Ti2+/Ti3+ states in a blue titanium dioxide photocatalyst. Catalysis Science & Technology 2018, 8, 4657–4664. [Google Scholar]

- Haritha, A.H.; et al. Sol–gel derived ZnO thin film as a transparent counter electrode for WO3 based electrochromic devices. Boletín de la Sociedad Española de Cerámica y Vidrio 2024, 63, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S. Impedance Spectroscopy for Electroceramics and Electrochemical System. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.15467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivula, K. Mott–Schottky analysis of photoelectrodes: sanity checks are needed. ACS Publications, 2021; pp. 2549–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravishankar, S.; Bisquert, J.; Kirchartz, T. Interpretation of Mott–Schottky plots of photoanodes for water splitting. Chemical Science 2022, 13, 4828–4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usler, A.L.; De Souza, R.A. A critical examination of the Mott–Schottky model of grain-boundary space-charge layers in oxide-ion conductors. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2021, 168, 056504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, R.E. Synthesis and Characterization of Some Nanostructured Materials for Visible Light-driven Photo Processes. Linköping University Electronic Press, 2020; Vol. 2059. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.-F.; Lu, Y.-J.; Hu, C.-C. Effects of anions and pH on the stability of ZnO nanorods for photoelectrochemical water splitting. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 3429–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, R.E.; et al. Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles by co-precipitation method for solar driven photodegradation of Congo red dye at different pH. Photonics and Nanostructures-Fundamentals and Applications 2018, 32, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. A short review on heterojunction photocatalysts: Carrier transfer behavior and photocatalytic mechanisms. Materials Research Bulletin 2021, 142, 111406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; et al. Defect engineering of nanostructures: Insights into photoelectrochemical water splitting. Materials Today 2022, 52, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Guo, L.; He, T. Influence of Vacancy Defects on the Interfacial Structural and Optoelectronic Properties of ZnO/ZnS Heterostructures for Photocatalysis. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process parameters | ZnO | ZnO + NH4F | ZnO + EDA |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Zn(NO3)2 (mM) | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| NH4F (mM) | 0.0 | 15 | 0.0 |

| EDA (mM) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10 |

| Temp (°C) | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Time (min) | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Potential (V) | -1.0 | -1.0 | -1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).