Submitted:

01 September 2024

Posted:

05 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Emotional Intelligence

2.2.2. Emotional Labor

2.2.3. Burnout

2.3. Statistics and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Common Method Bias Test

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.4. Associations of EI and Emotional Labor Strategies with Burnout

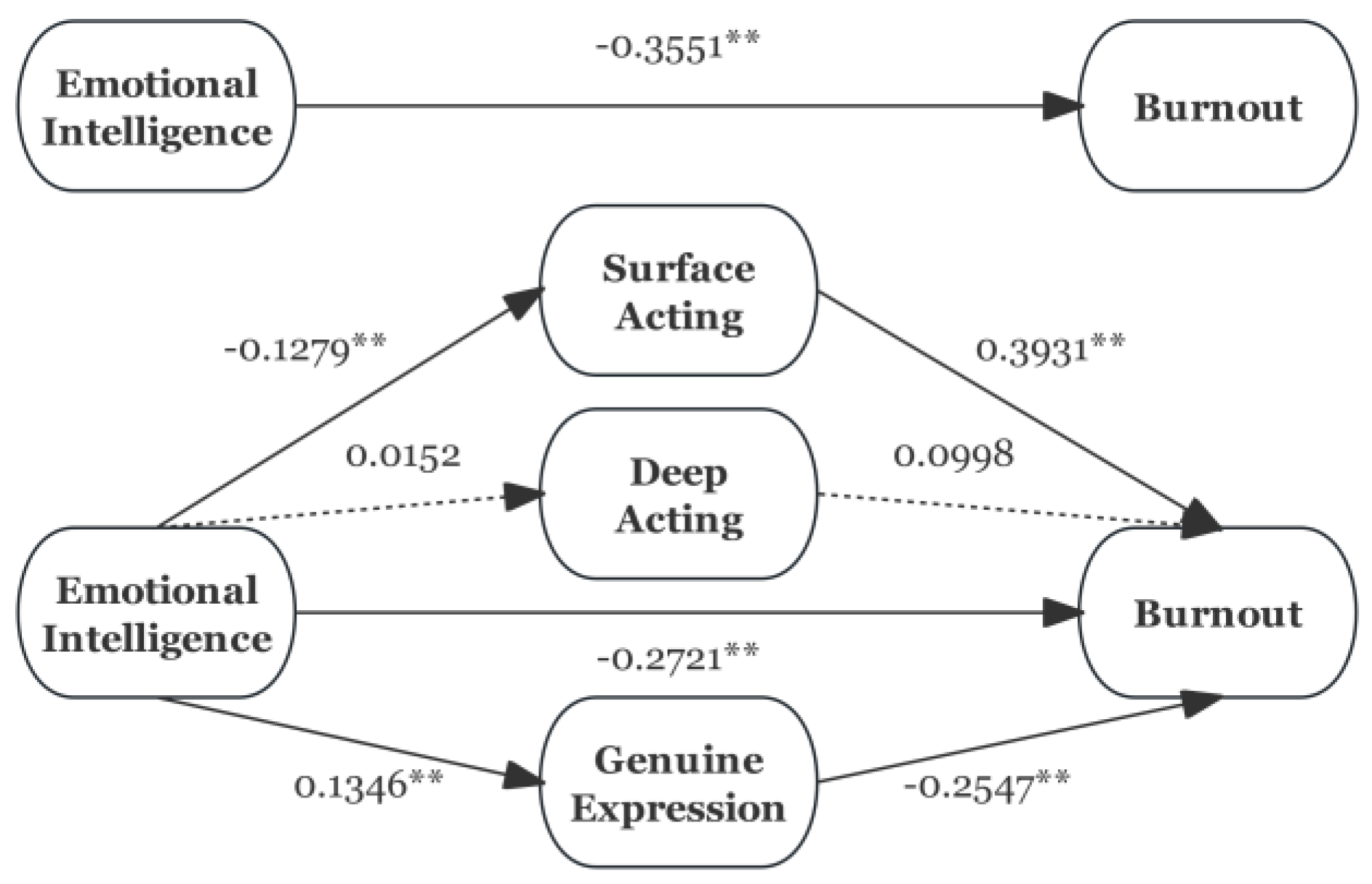

3.5. Mediating Effect of Emotional Labor

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raedeke, T.D.; Smith, A.L. Development and Preliminary Validation of an Athlete Burnout Measure. J Sport Exerc Psychol 2001, 23, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eklund1, R.C.; DeFreese, J.D. Athlete Burnout. In Handbook of Sport Psychology; 2020; pp. 1220–1240.

- Seehusen, C.N.; Howell, D.R.; Potter, M.N.; Walker, G.A.; Provance, A.J. Athlete Burnout Is Associated With Perceived Likelihood of Future Injury Among Healthy Adolescent Athletes. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2023, 62, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, J.S.; Watson, A. Overuse Injuries, Overtraining, and Burnout in Young Athletes. Pediatrics 2024, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laborde, S.; Dosseville, F.; Allen, M.S. Emotional intelligence in sport and exercise: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2016, 26, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.B.; Fletcher, T.B. Emotional Intelligence: A Theoretical Overview and Implications for Research and Professional Practice in Sport Psychology. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 2007, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional Intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Roberts, R.D.; Barsade, S.G. Human Abilities: Emotional Intelligence. Annual Review of Psychology 2008, 59, 507–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R.; Sitarenios, G. Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion 2003, 3, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercader-Rubio, I.; Ángel, N.G. The Importance of Emotional Intelligence in University Athletes: Analysis of Its Relationship with Anxiety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; González-Valero, G.; Puertas-Molero, P.; García-Martínez, I. Development of Emotional Intelligence through Physical Activity and Sport Practice. A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences 2019, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, A.; Jekauc, D. The Influence of Emotional Intelligence on Performance in Competitive Sports: A Meta-Analytical Investigation. Sports 2018, 6, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lott, G.H.; Turner, B.A. Collegiate Sport Participation and Student-Athlete Development through the Lens of Emotional Intelligence. Journal of Amateur Sport 2019, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefendorff, J.M.; Croyle, M.H.; Gosserand, R.H. The dimensionality and antecedents of emotional labor strategies. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2005, 66, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Chelladurai, P. Affectivity, Emotional Labor, Emotional Exhaustion, and Emotional Intelligence in Coaching. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 2016, 28, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A. Emotion regulation in the workplace: a new way to conceptualize emotional labor. J Occup Health Psychol 2000, 5, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J. The Emerging Field of Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Review of General Psychology 1998, 2, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Humphrey, R.H. Emotional Labor in Service Roles: The Influence of Identity. Academy of Management Review 1993, 18, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanyu, G.; Jizu, L. The effect of emotional intelligence on unsafe behavior of miners: the role of emotional labor strategies and perceived organizational support. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics 2023, 29, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psilopanagioti, A.; Anagnostopoulos, F.; Mourtou, E.; Niakas, D. Emotional intelligence, emotional labor, and job satisfaction among physicians in Greece. BMC Health Services Research 2012, 12, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.-b.; Lee, J.C.K.; Zhang, Z.-h.; Jin, Y.-l. Exploring the relationship among teachers' emotional intelligence, emotional labor strategies and teaching satisfaction. Teaching and Teacher Education 2013, 35, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, M.; Chen, Y.; Withrow, S.; Sliter, K. Older and (Emotionally) Smarter? Emotional Intelligence as a Mediator in the Relationship between Age and Emotional Labor Strategies in Service Employees. Experimental Aging Research 2013, 39, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Xu, P.; Zhou, K.; Xue, J.; Wu, H. Mediating role of emotional labor in the association between emotional intelligence and fatigue among Chinese doctors: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeung, D.Y.; Kim, C.; Chang, S.J. Emotional Labor and Burnout: A Review of the Literature. Yonsei Med J 2018, 59, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagil, D. The mediating role of engagement and burnout in the relationship between employees' emotion regulation strategies and customer outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2012, 21, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariou, A.; Koutsimani, P.; Montgomery, A.; Lainidi, O. Emotional Labor and Burnout among Teachers: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 12760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S. Emotional Labor Strategies, Stress, and Burnout Among Hospital Nurses: A Path Analysis. J Nurs Scholarsh 2020, 52, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeung, D.Y.; Lee, H.O.; Chung, W.G.; Yoon, J.H.; Koh, S.B.; Back, C.Y.; Hyun, D.S.; Chang, S.J. Association of Emotional Labor, Self-efficacy, and Type A Personality with Burnout in Korean Dental Hygienists. J Korean Med Sci 2017, 32, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeung, D.Y.; Chang, S.J. Moderating Effects of Organizational Climate on the Relationship between Emotional Labor and Burnout among Korean Firefighters. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.S.; Wong, C.S.; Song, L.J. The construct and criterion validity of emotional intelligence and its potential utility for management studies. J Appl Psychol 2004, 89, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.-C.; Hung, C.-M.; Liu, Y.-T.; Cheng, Y.-J.; Yen, C.-Y.; Chang, C.-C.; Huang, C.-K. Associations between emotional intelligence and doctor burnout, job satisfaction and patient satisfaction. Medical Education 2011, 45, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.-S.; Law, K.S. The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. The Leadership Quarterly 2002, 13, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, M.; Deng, X.; Zhao, J.; Kong, F. Psychometric Properties and Measurement Invariance Across Sex of the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale in Chinese adolescents. Psychological Reports 2022, 125, 599–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Peng, W.; Pan, J. Investigation into the correlation between humanistic care ability and emotional intelligence of hospital staff. BMC Health Services Research 2022, 22, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Lee, R.T. Testing a conservation of resources model of the dynamics of emotional labor. J Occup Health Psychol 2002, 7, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Zou, S.; Fan, R.; Wang, B.; Ye, L. The influence of athletes' gratitude on burnout: the sequential mediating roles of the coach-athlete relationship and hope. Front Psychol 2024, 15, 1358799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saarinen, M.; Phipps, D.J.; Bjørndal, C.T. Mental health in student-athletes in Norwegian lower secondary sport schools. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2024, 10, e001955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grugan, M.C.; Olsson, L.F.; Vaughan, R.S.; Madigan, D.J.; Hill, A.P. Factorial validity and measurement invariance of the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ). Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2024, 73, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeneessier, A.S.; Azer, S.A. Exploring the relationship between burnout and emotional intelligence among academics and clinicians at King Saud University. BMC Med Educ 2023, 23, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero Jurado, M.D.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Martos Martínez, Á.; Barragán Martín, A.B.; Simón Márquez, M.D.M.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. Emotional intelligence as a mediator in the relationship between academic performance and burnout in high school students. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0253552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, N.M.; Pryce, N. The Role of Mindful Self-Care in the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Burnout in University Students. J Psychol 2022, 156, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, C.; Kravets, V.; Schenker, M.; Moore, T., Jr. Emotional intelligence, burnout, and professional fulfillment in clinical year medical students. Med Teach 2021, 43, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleason, F.; Baker, S.J.; Wood, T.; Wood, L.; Hollis, R.H.; Chu, D.I.; Lindeman, B. Emotional Intelligence and Burnout in Surgical Residents: A 5-Year Study. J Surg Educ 2020, 77, e63–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercader-Rubio, I.; Ángel, N.G.; Ruiz, N.F.O.; Carrión-Martínez, J.J. Emotional intelligence as a predictor of identified regulation, introjected regulation, and external regulation in athletes. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 1003596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson, H.; Sagar, S.S.; Stenling, A. Fear of failure, psychological stress, and burnout among adolescent athletes competing in high level sport. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2017, 27, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarrochi, J.; Deane, F.P.; Anderson, S. Emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between stress and mental health. Personality and individual differences 2002, 32, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Stress, culture, and community: The psychology and philosophy of stress; Springer Science & Business Media: 2004.

- Deng, H.; Wu, H.; Qi, X.; Jin, C.; Li, J. Stress Reactivity Influences the Relationship between Emotional Labor Strategies and Job Burnouts among Chinese Hospital Nurses. Neural Plast 2020, 2020, 8837024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liu, F.; Li, X.; Qu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Yao, J. The Effect of Emotional Labor on Presenteeism of Chinese Nurses in Tertiary-Level Hospitals: The Mediating Role of Job Burnout. Front Public Health 2021, 9, 733458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n (N=260) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 70(26.9%) |

| Female | 190(73.1%) |

| Age | 15.10±1.95 |

| YoT | 3.93±2.48 |

| Level | |

| First-class | 65(25.0%) |

| Second-class | 44(16.9%) |

| None | 151(58.1%) |

| Gender | Age | YoT | Level | EI | SA | DA | GE | Burnout | |

| Gender | 1 | ||||||||

| Age | 0.11 | 1 | |||||||

| YoT | 0.207** | 0.558** | 1 | ||||||

| Level | 0.376** | 0.620** | 0.563** | 1 | |||||

| EI | -0.254** | -0.051 | 0.097 | -0.072 | 1 | ||||

| SA | 0.352** | 0.228** | 0.246** | 0.340** | -0.169** | 1 | |||

| DA | 0.298** | 0.143* | 0.170** | 0.193** | 0.019 | 0.614** | 1 | ||

| GE | 0.098 | 0.045 | 0.068 | 0.061 | 0.168** | 0.420** | 0.506** | 1 | |

| Burnout | 0.281** | 0.302** | 0.282** | 0.418** | -0.499** | 0.430** | 0.215** | -0.118 | 1 |

| Model | Variables | β | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | VIF | R2 | ΔR2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 15.932 | |||||||

| Gender | 0.157 | 2.559 | 0.011 | 0.055 | 0.421 | 1.202 | ||||

| Age | 0.086 | 1.127 | 0.261 | -0.022 | 0.082 | 1.873 | ||||

| YoT | 0.044 | 0.611 | 0.542 | -0.026 | 0.05 | 1.638 | ||||

| Level | -0.281 | -3.454 | 0.001 | -0.348 | -0.095 | 2.103 | ||||

| Model 2 | 0.414 | 0.214 | 35.94 | |||||||

| Gender | 0.018 | 0.328 | 0.743 | -0.136 | 0.19 | 1.293 | ||||

| Age | 0.013 | 0.197 | 0.844 | -0.04 | 0.049 | 1.898 | ||||

| YoT | 0.164 | 2.614 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.078 | 1.705 | ||||

| Level | -0.276 | -3.957 | 0 | -0.326 | -0.109 | 2.103 | ||||

| EI | -0.489 | -9.643 | 0 | -0.42 | -0.277 | 1.117 | ||||

| Model 3 | 0.509 | 0.095 | 32.54 | |||||||

| Gender | -0.052 | -0.994 | 0.321 | -0.235 | 0.077 | 1.405 | ||||

| Age | 0.001 | 0.023 | 0.982 | -0.041 | 0.042 | 1.906 | ||||

| YoT | 0.13 | 2.236 | 0.026 | 0.004 | 0.066 | 1.718 | ||||

| Level | -0.223 | -3.435 | 0.001 | -0.277 | -0.075 | 2.154 | ||||

| EI | -0.416 | -8.477 | 0 | -0.365 | -0.228 | 1.232 | ||||

| SA | 0.307 | 4.957 | 0 | 0.174 | 0.404 | 1.965 | ||||

| DA | 0.112 | 1.844 | 0.066 | -0.007 | 0.209 | 1.89 | ||||

| GE | -0.252 | -4.684 | 0 | -0.319 | -0.13 | 1.474 |

| Outcome variable |

Predictive variable |

Fitting indicators | Coefficients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | R2 | F | β | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| Burnout | 0.4985 | 0.2485 | 85.3155 | |||||||

| EI | -0.3551 | 0.0384 | -9.2366 | 0 | -0.4308 | -0.2794 | ||||

| SA | 0.1689 | 0.0285 | 7.5736 | |||||||

| EI | -0.1279 | 0.0465 | -2.752 | 0.0063 | -0.2195 | -0.0364 | ||||

| DA | 0.0193 | 0.0004 | 0.0963 | |||||||

| EI | 0.0152 | 0.0491 | 0.3104 | 0.7565 | -0.0815 | 0.1119 | ||||

| GE | 0.1684 | 0.0284 | 7.5328 | |||||||

| EI | 0.1346 | 0.049 | 2.7446 | 0.0065 | 0.038 | 0.2311 | ||||

| Burnout | 0.6542 | 0.4279 | 47.6911 | |||||||

| EI | -0.2721 | 0.0356 | -7.6379 | 0 | -0.3422 | -0.2019 | ||||

| SA | 0.3931 | 0.0593 | 6.6267 | 0 | 0.2763 | 0.5099 | ||||

| DA | 0.0998 | 0.0579 | 1.7234 | 0.086 | -0.0142 | 0.2139 | ||||

| GE | -0.2547 | 0.051 | -4.9964 | 0 | -0.3551 | -0.1543 | ||||

| Path | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct(c') | -0.2721 | 0.0356 | -0.3422 | -0.2019 | 76.63% | |

| Indirect | EL(a*b) | -0.083 | 0.0231 | -0.1266 | -0.0387 | 23.37% |

| SA(a1*b1) | -0.0503 | 0.0205 | -0.0918 | -0.0101 | 14.17% | |

| DA(a2*b2) | 0.0015 | 0.0067 | -0.0128 | 0.0159 | -0.42% | |

| GE(a3*b3) | -0.0343 | 0.0161 | -0.069 | -0.0058 | 9.66% | |

| Total(c) | -0.3551 | 0.0384 | -0.4308 | -0.2794 | 100% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).