1. Introduction

The increase in greenhouse gas emissions fosters the transport sector towards new technological perspectives on personal mobility [

1]. In the last few years, the major strategy adopted to achieve the decrease of pollutants, and the adoption of more sustainable and active mobility lifestyles is electric micromobility. This term frames light and active vehicles, human-powered and electrically assisted, that weigh up to 350 kg and can reach a maximum speed between 25 and 45 km/h [

2], according to the country's regulations.

The emerging interest in these convenient and efficient alternative means of transport has led to the exploration of the role of design and engineering researchers and practitioners in cross-disciplinary contexts. The paper, therefore, reports the design research results of the research project “MicrovehicLE fOr staNd-Alone and shaReD mObility – LEONARDO”, funded by the European Commission under the Horizon 2020 framework. In this research context, the project aims to define a new microvehicle enhancing existing micromobility technologies to foster the actual paradigm shift in urban mobility [

3] through designing a climate-and-environmentally-friendly and safe mobility solution. Moreover, the objective is to do an extensive demonstration test in a real environment, within Europe, for a revision and re-design process allowing to reach the TRL 8-9 [

4]. The initial phases led the researchers to identify the potentials, opportunities, and sources of value creation offered by interdisciplinary collaboration between the Industrial Engineering and Design scientific disciplinary sectors. Therefore, the research team was enlarged to support the design of this attractive, affordable, resource-efficient, safe, and seamless new alternative of transport.

Through this systemic vision, the research team identified the development of an “interdisciplinary design model for urban transport product innovation” as an overarching goal. The specific research objectives are: (i) to define a scalable and replicable design model; (ii) to correlate mixed methods from different scientific disciplinary sectors; (iii) to highlight the hierarchical structure of the design research phases and the corresponding research tasks to be undertaken; and (iv) to evaluate the design model, developing and prototyping the “Leonardo” microvehicle. Therefore, the questions orienting the research are: (i) what are the main design frameworks for innovation capable of supporting the development of new products in the mobility sector; (ii) which design research tools and methods enable product development; and (iii) which tools and methods, proper of the Industrial Engineering disciplinary sector, enable the product development.

The paper is organized, as follows. The second section critically reviews the current literature on the existing frameworks for innovation. Then, the third section is about the methodological approach, the design research strategy adopted, how the research tasks have been structured into Work Packages (WPs), and which tools and methods have been employed. Following this, the fourth section is about the “Leonardo Project” developing and prototyping results. Lastly, the fifth section discusses how the research team defined the design model.

2. Design Framework for Innovation

The design research team frames the Design thinking approach as a user-centered and iterative driver of “innovation and creative problem-solving” [

5,

6] capable of defining micromobility solutions valued by testing end-users. This section provides an overview of the present “Double-diamond” design thinking framework for innovation, highlighting its hierarchy, attributes, and related tools. Therefore, the research team sets the basis for delineating the design journey and accurately structuring WPs, research tasks, and activities, starting from dividing the process into problem and solution space.

The authors consider “design thinking” a visionary, inspiring, disruptive, creative, and organizational model that bridges the two disciplinary sectors and fosters the expected outcomes across working groups. In recent years, many researchers extended the design domain to the engineering field discussing the potential of “design thinking” and how it can broaden engineering skills [

7]. This approach is envisioned as a problem-oriented, socially positive, and high-performance approach to foster empathy, creativity, and innovation in engineering design [

8,

9,

10]. The literature also highlights how Design thinking could be supportive in a communicative way facilitating interactions within interdisciplinary and informal social team environments, capable of achieving the complexity of the research challenges [

9,

11,

12]. Panke [

13] discussed how fruitful and effective is to apply “design thinking” in a varied scientific field in higher education and listed the following positive traits and effects: (i) encouraging tacit experiences; (ii) increasing empathy; (iii) reducing cognitive bias; (iv) promoting playful learning; (v) creating flow/verve; (vi) fostering inter/meta-disciplinary collaboration; (vii) inducing productive failure/increasing resilience; (viii) producing surprising and delightful solutions; and (ix) nurturing creative confidence. These multifaceted features highlight the reasons for integrating Design Thinking in higher education among different disciplines and describe the possible emerging outputs. Similarly, Micheli et al. [

5] provided further insights into “design thinking” by discussing the general attributes, to better understand what constitutes it: (i) creativity and innovation; (ii) user-centeredness and involvement; (iii) problem-solving; (iv) iteration and experimentation; (v) interdisciplinary collaboration; (vi) ability to visualize; (vii) gestalt view; (viii) abductive reasoning; (ix) tolerance of ambiguity and failure; (x) blending rationality and intuition; and (xi) design tools and methods. The last feature refers to strategies capable of enabling the other characteristics. The development of personalized human-centered, co-creative, and innovative novel ideas is, therefore, determined by tools and methods through balancing analytical and intuitive thinking [

14], understanding relationships, environmental factors, trends, backgrounds and user needs [

15], accepting and embracing uncertainty [

16], integrating diverse research perspectives [

17], adopting a nonlinear, iterative and alternative approach, and developing or prototyping visual insights.

Researchers frame tools and methods within design models and phases to better solve “wicked problems” (see [

18]). The following subsection delves into the existing design thinking model and, notably, the authors explore the “Double-diamond design thinking model” in more detail.

2.1. Double-Diamond Design Thinking Model

Design philosophers, design companies, and councils have published many design thinking models since the design thinking perspective was theorized [

19]. The literature presents about 15 similar models, that slightly differentiate one another for addressing different challenges in varying research contexts and areas [

19,

20], among which the most known are: (i) Collective Action Toolkit [

21]; (ii) Design Thinking [

22]; (iii) Design thinking Bootleg [

23]; (iv) Human Centred Design Toolkit [

24,

25]; (v) The Double Diamond [

26]; and (vi) Service Design [

27].

The correlation between the design thinking models presented shows five clear correspondences and Kueh and Thom [

19] framed into the following phases: (i) the context or problem framing phase; (ii) the idea generation phase; (iii) the prototyping phase; (iv) the implementation phase; (v) the reframing phase. These similarities enable every model to approach the research challenges. Notably, the authors explore the Double-Diamond as the model visually capable of highlighting divergent and convergent thinking in the design process.

The straightforward Double Diamond design thinking process, originally developed by the British Design Council [

26], foresees four consequential, explorative (divergent), and exploitative (convergent) key phases: (i) discover; (ii) define; (iii) develop; and (iv) deliver [

28].

The “Discover” and “Define” phases refer to the “Context or problem framing phase”. The “Develop” phase refers to the “idea generation” phase. The “Deliver” phase refers to the “Prototyping” and “Implementation” phases.

In the first diamond, the “Discover” divergent phase is about “broadening our horizons” through research. This is the inspiring fuzzy starting point on the topic, the products or services constraints, and the related complex problems users are facing. The aim is to understand the context of the problem, identify the macro trends and the related technological advancements, empathize, and engage whoever is affected by the issues of the research to perceive the end-user perspective, motivations, and latent needs and uncover disruptive ideas. Moreover, the literature provides much research on which tools and methods it could entail [

5,

13,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]: (i) systematic literature review; (ii) secondary research; (iii) case study research; (iv) ethnographic design methods; (v) identify stakeholder; (vi) interview; (vii) survey; (viii) questionnaires; (ix) card sorting; (x) field study; (xi) user observation; (xii) user shadowing; (xiii) empathy maps; (ixv) focus group; (xv) hierarchical task analysis; (xvi) benchmarking (see

Figure 1).

The “Define” convergent phase is about “heading towards the core problem” and actionable tasks. This is a reflective phase on the previously collected knowledge resource and design insights. The aim is to analyze, synthesize, co-design insights and organize the inputs, that emerged from the “Discover” phase, to define the strategic brief: a technical document reporting systematically the findings into opportunities and objectives [

35]. Going on, as the literature stated [

5,

13,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34], it could entail the following tools and methods: (i) thematic analysis (see [

36]); (ii) content analysis (see [

37]); (iii) personas; (iv) stakeholder analysis; (v) stakeholder map; (vi) task mapping; (vii) experience map; (viii) scenarios of use; (ix) user journey map; (x) service blueprint map; (xi) affinity mapping; (xii) mind maps; (xiii) miro.com (see [

38]); (ixv) SWOT analysis; (xv) Kano model; (xvi) brainstorming; (xvii) “How might we” question; (xviii) focus group; (xix) co-design workshop; (xx) design brief (see

Figure 1).

In the second diamond, the “Develop” divergent phase is about “co-expressing and developing disruptive ideas in a free-thinking environment”. This is a collaborative design phase of the strategic brief. The aim is to generate an iterative co-dialogue with involved stakeholders, researchers, designers, and experts on the data gathered to design the outcome's desirability, feasibility, and viability. Moving forward, as the literature stated [

5,

13,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34], it entails the following tools and methods: (i) brainstorming; (ii) “How might we” question; (iii) focus group; (iv) co-design workshops; (v) mind maps; (vi) miro.com; (vii) concept maps; (viii) design guidelines and standards; (ix) sketching; (x) crazy eights; (xi) design-by-drawing method; (xii) sprint and design sprint (see [

39,

40,

41]); (xiii) storyboard; (ixv) visual storytelling; (xv) scenario building; (xvi) AI assistive tools (see

Figure 1).

The “Deliver” convergent phase is about “transforming insights into real outputs”. This is about prototyping and testing promising emerging insights. The aim is to enable the designers to explore the idea selected, whether in low or high fidelity, select valuable ones, and get feedback about the users' perception, usability, affordance, or accessibility of the outcome. Lastly, as the literature stated [

5,

13,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34], it entails the following tools and methods: (i) storyboard; (ii) LEGO Serious Play (see [

42]); (iii) scenario building; (iv) 3D modeling with parametric software (e.g. Fusion360 or SolidWorks); (v) rendering software using Keyshot or Lumion; (vi) wireframes using AutoCAD or Adobe Illustrator; (vii) virtual prototyping (e.g. Meta Quest); (viii) AI assistive tools; (ix) physical prototype; (x) mock-ups; (xi) rapid prototyping; (xii) 3D printing; (xiii) field experiments; (ixv) usability testing; (xv) user testing; (xvi) A/B test (see

Figure 1).

In conclusion, the present section sets the basis for framing the methodological approach of the research project “Leonardo” through a critical literature review of the “Design thinking” attributes, process, models, phases, and tools. The authors, therefore, identified the “Design thinking” process as a framework for innovation and organized the research through the “Double diamond design thinking model”.

3. Materials and Methods

The research strategy adopted is “research through design” (see [

43]) and aims to produce knowledge to guide interdisciplinary design research, practice, and education in defining urban transport product innovation.

The Design Framework for Innovation, framed in

Figure 1, is used as an interdisciplinary design research model for organizing data gathered from the initial brief, structuring the research phases, selecting specific mixed methods, developing research materials, and designing research activities. This model enables the research team to understand the context, opportunities, and insights to explore formal, technological, and functional microvehicle innovation ideas and define a scalable interdisciplinary design model for urban transport product innovation. Notably, the model was used for organizing the research design process in 4 WPs, aligning with 3 specific research objectives for each research direction, and encompassing 14 research macro-tasks, and 24 corresponding micro-tasks. The research tasks were addressed by employing quantitative and qualitative research methods, from different disciplinary sectors.

3.1. WP1: Discover Phase

During the initial “Discover” phase, the team organized the research phase into 4 macro tasks, presented in

Figure 1: (i) identify macro trends; (ii) understand the context of the problem; (iii) empathize; and (iv) in-depth analysis of the technological advancements. The first macro task was addressed by the design research team and aimed at deepening analysis of the topic proposed, that is the research project “Leonardo”. The engineering research team presented their initial brief, the challenges, the research objectives, the expected outcomes, and the deadlines. Thus, the design research team employed the critical literature review and case study research methods to delve into the mobility field and electric micromobility strategy, to quickly achieve sustainable goals. The second macro task is about understanding the context of the research project and the research team organized the work into the following micro research tasks (i) an in-depth analysis of the brief; (ii) an in-depth analysis of the project partner; (iii) an in-depth analysis of the disruptive micromobility product to define; (iv) the mapping of the research areas; and (v) the framing of the research methods. Firstly, the research team re-analyzed the project priorities and constraints, included in the Grant Agreement. Going on, they designed the first participatory activities, with the principal investigator, project experts, research partners, partner company, and design and engineering researchers through the use of focus groups, and semi-structured interviews to identify the corresponding stakeholders and relevant implicit factors. The research team also made comparable benchmarks of the kick scooters and monowheels, as product-related market segments. The aim was to analyze the competitors, similar to the blended microvehicle proposed by the research project, and identify formal emerging trends, technological advancements, manufacturing processes adopted, materials employed, user needs, and user evaluations. Finally, brainstorming and workshops with the principal investigator, project experts, and design and engineering researchers were organized to map the research areas and directions to follow for defining the expected outcomes. The research team also framed the research methods into a graphic visualization that was highly iterated during the process and reported in the Discussion section (

Figure 14 and

Figure 15). Moving forward, the third macro research task is about empathizing with the users and doing (i) an in-depth analysis of the stakeholders; and (ii) an in-depth analysis of the user interactions. The research team adopted ethnographic design methods, from the design research literature review, and undertook semi-structured interviews, hierarchical task analysis, user shadowing, and user observation tools to identify how users interact with kick scooters and monowheels. These qualitative methods set the basis for identifying new design insights, regarding the positioning of the feet, and the need to delve into anthropometric data. Particularly, the research team sized the components according to the anthropometric parameters for the European population (see [

44]). Lastly, the research team deepened into technological advancements, through secondary research. Some previous tasks were iterated, doing benchmarks, critical academic literature review, and case study research on materials and manufacturing processes adopted by companies in the mobility sector. The researchers also delved into patent research and technical literature review through comfort, mechanical strength, safety, and rigidity regulations, to examine which materials could fulfill the project requirements fully. The team deepened the analysis of safety regulations, requirements, and framework conditions to let these vehicles circulate on public roads through accident databases and international literature. Going on, they address the safety analysis on (i) investigation of kick scooter-related regulations, active in the European Countries; (ii) mapping of kick scooter accidents in Germany; and (iii) a survey on the use of kick scooters. They addressed legal and technical frameworks and municipal regulations of the microvehicles, and accident analysis. The latter investigation was carried out through the analysis and mapping of the (i) conflict and collision situations and constellations; (ii) data information on personal injuries; and (iii) related accident parameters, regarding the location, the use of helmets and protective clothing.

3.2. WP2: Define Phase

The “Define” phase was about synthesizing the data collected in the previous stage of development. The team structured the work package into 4 macro tasks, presented in

Figure 1: (i) analyze the data gathered; (ii) synthesize data; (iii) co-design insights; and (iv) design a strategic brief into a technical document. The first macro task aimed to deepen the data collected through the use of thematic analysis and content analysis in a participative environment, with the principal investigator, project experts, and design and engineering researchers. Going on, the research team synthesized the knowledge resources through the use of SWOT analysis, brainstorming, and participatory affinity mapping. Coherently, they defined an overview of the product components framing the entire assembly, through a task mapping tool, to identify which were the main elements and the research directions to focus on during the “Develop” and “Deliver” work packages. After defining the strengths, opportunities, weaknesses, and threats, the third macro task fostered co-design activities, through brainstorming, focus groups, and co-design workshops, to define insights. Lastly, the team organized the work in (i) opportunity areas mapping, and (ii) defining the correct research question to orient the second diamond. These two micro tasks were supported by affinity mapping, HMW questions, and brainstorming tools in a co-design context to design the strategic brief.

3.3. WP3: Develop Phase

The third diverging phase aimed to develop disruptive and innovative ideas in a participatory context. This stage of development is organized as follows: (i) developing the strategic brief; (ii) co-designing disruptive ideas; and (iii) iterating the results that emerged from the previous macro tasks. Initially, the research team structured the latter two work packages framing the research methods to be employed. HMW question and a focus group with the principal investigator, the project experts, and design and engineering researchers oriented the following research phases, organizing and structuring the subsequent research tasks. Moving forward, the next research activity aimed to explore new formal solutions. The technological advancements, materials, and manufacturing processes identified in the strategic brief guided this formal exploration, and the researchers employed both design-by-drawing and design sprint methods, and the crazy eight, sketching and visual storytelling tools. The research team organized and designed a “1-day” design sprint (see [

41]), incorporating all the tools cited in the previous paragraph. The design sprint adapted foresees the following phases, tools, and methods: (i) the idea generation through the definition of disruptive and individual HMW questions, in 10 minutes; (ii) the sharing of the HMW questions generated and the categorization in theme through the use of affinity diagram tool, in 20 minutes; (iii) the voting of the most coherent, compelling and important HMW question, that could orient the next research phases, in 5 minutes; (iv) the individual fast sketching exercise through crazy eight tools, in 8 minutes; (v) the sharing and voting of the emerged ideas and sketches, in 20 minutes; (vi) the re-elaboration of the selected sketch, in 20 minutes; (vii) the definition of storyboard and storytelling about how the user should interact with the final product through the use of rendering, 3D modeling, and wireframes software, in 40 minutes; and (viii) a brief presentation of the output, in 30 minutes. In the end, the team iterated the previous tasks as long as they identified a coherent idea.

3.4. WP4: Deliver Phase

The fourth converging phase brought to the exploration and successive implementation of the selected idea. The team organized this work package into 3 macro tasks, presented in

Figure 1: (i) exploring the selected idea; (ii) product prototyping; and (iii) product testing. As already done in the previous stage, the researchers iterated the framing of the research methods through HMW questions and focus groups. The second macro task aimed at prototyping the idea selected. The team divided the tasks into three different approaches: (i) prototyping in a virtual environment; (ii) rapid prototyping; and (iii) physical prototyping. Firstly, the team explored the product output through wireframes and 3D modeling with AutoCAD and the parametric software Solidworks. Subsequently, they explained how the users have to interact with the product through renderings, storyboards, and visual storytelling, defined with Lumion, Adobe Illustrator, and Photoshop. The last macro task is about testing and was structured in parallel as the prototyping one as follows: (i) remote quantitative testing; and (ii) testing following regulations. Before possibly testing the product in person, the research team performed a usability test with Google Forms. The objective was to understand how attractive, perspicuous, efficient, dependable, stimulative, and innovative appear to define the product. Therefore, the team grouped 27 people at which they presented the Leonardo microvehicle and they submitted a questionnaire, asking the following questions: (i) “An overall impression of the product. Do users like or dislike it?”; (ii) “Is it easy to get familiar with the product and learn how to use it?”; (iii) “Can users solve their tasks without unnecessary effort? Does it react fast?”; (iv) “Does the user feel in control of the interaction? Is it secure and predictable?”; (v) "Is it exciting and motivating to use the product? Is it fun to use?”; and (vi) “Is the design of the product creative? Does it catch the interest of users?”. The researchers identified the Likert scale, as a coherent question type to express the level of agreement or disagreement of the samples, to analyze quantitatively the responses.

The first tangible prototypes were singular components of the assembly and were created through additive manufacturing for doing preliminary testing. Later, the research team developed different types of component prototypes for each research direction to be re-assembled into one product prototype, in collaboration with the partner company. The aim was to test, following regulations, safety, comfort, mechanical strengths, and rigidity of the materials identified in the research phase [

45].

4. Results

As discussed in the first section, the overarching research objectives are: (i) developing a new silent, clean, energy-efficient, and safe microvehicle; (ii) doing an extensive demonstration; and (iii) doing the re-design activity. Notably, the “Leonardo” research project aims to enhance the features of monowheel and scooter concepts for defining a blended stand-alone microvehicle, that is attractive and affordable to a wider market segment. The project also provides a battery-sharing mode, enabled by a system already developed by the University of Florence, and an auxiliary battery as a touchpoint of the service system. Moreover, the project foresees testing a fleet of microvehicles in a real environment in 5 European cities, including Rome, Palermo, and Bruxelles.

The revision of the main objectives led to delving into the research challenges. This further in-depth analysis of the brief set the basis for dividing the design process into 3 main research directions to address simultaneously: (i) deck designing; (ii) steering column designing; and (iii) auxiliary and fixed battery case designing. Moving forward, the analysis of the Grant Agreement highlighted relevant factors and priorities for every research direction, concerning: (i) costs; (ii) lightness; (iii) compactness; and (iv) ease of transport.

In the following, the research team presents in detail every aspect of the final work performed, dividing each subsection into (i) a strategic design brief, including the collection of all information relating to technical/functional requirements and project constraints useful for defining the needs and problems that the product intends to solve; (ii) the embodiment and detailed design, where the set of elaborated ideas are structured, the layouts, and the preliminary drawings of the various components are visually depicted and the considerations made on the production processes are listed, in technical-economic terms; and (iii) prototype design, that foresees the various tangible output produced.

4.1. Deck Designing

4.1.1. Deck Strategic Design Brief

The benchmark lets us compare similar products available on the market, such as kick scooters and monowheels. This method laid the foreground for defining four specific deck objectives: (i) providing flexibility to the deck, replacing the suspensions of traditional microvehicles for increased lightness; (ii) minimizing the weight of the entire vehicle; (iii) improving the user comfort; and (iv) supporting the “trolley mode”, that is the transportation when the microvehicle is folded, avoiding the deck to collide with any other part in the folding process.

The first specific research objective referred to the evaluation of the materials to be employed, among which the research team identified: (i) aluminium sheets; (ii) fiber-reinforced composites; and (iii) bamboo.

The second research objective referred to the ergonomic design of the deck. Notably, the research team focused their output on one relevant deck constraint: to be jointed to the front wheel and hinged a few centimeters below the center of the wheel. The highlighted characteristic showed that the platform should have been wider than those commercially available and the ideal rotation angle for adequate maneuverability and driving comfort has to be set to a value of 25 degrees in both directions.

4.1.2. Deck Embodiment and Detailed Design

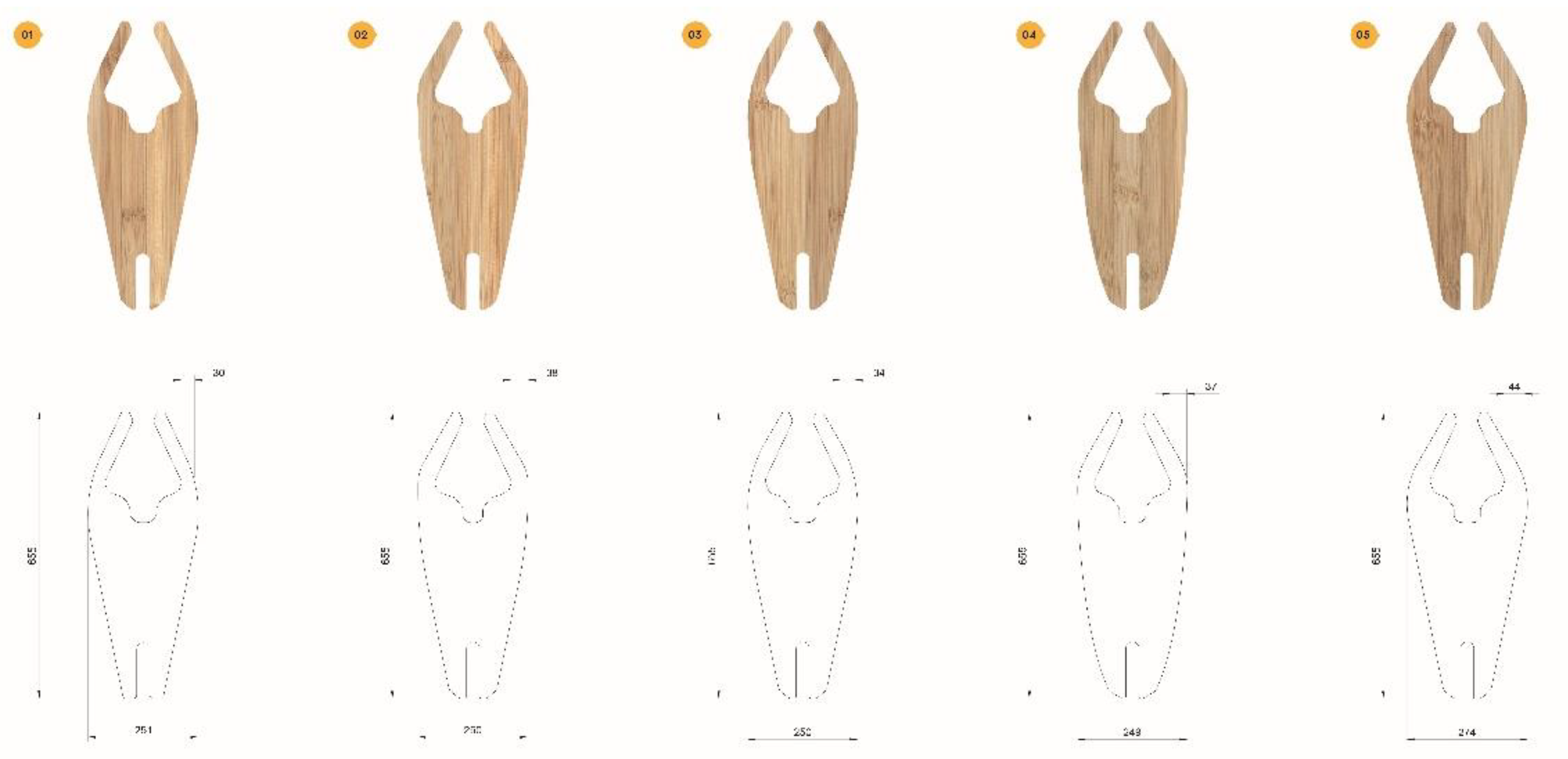

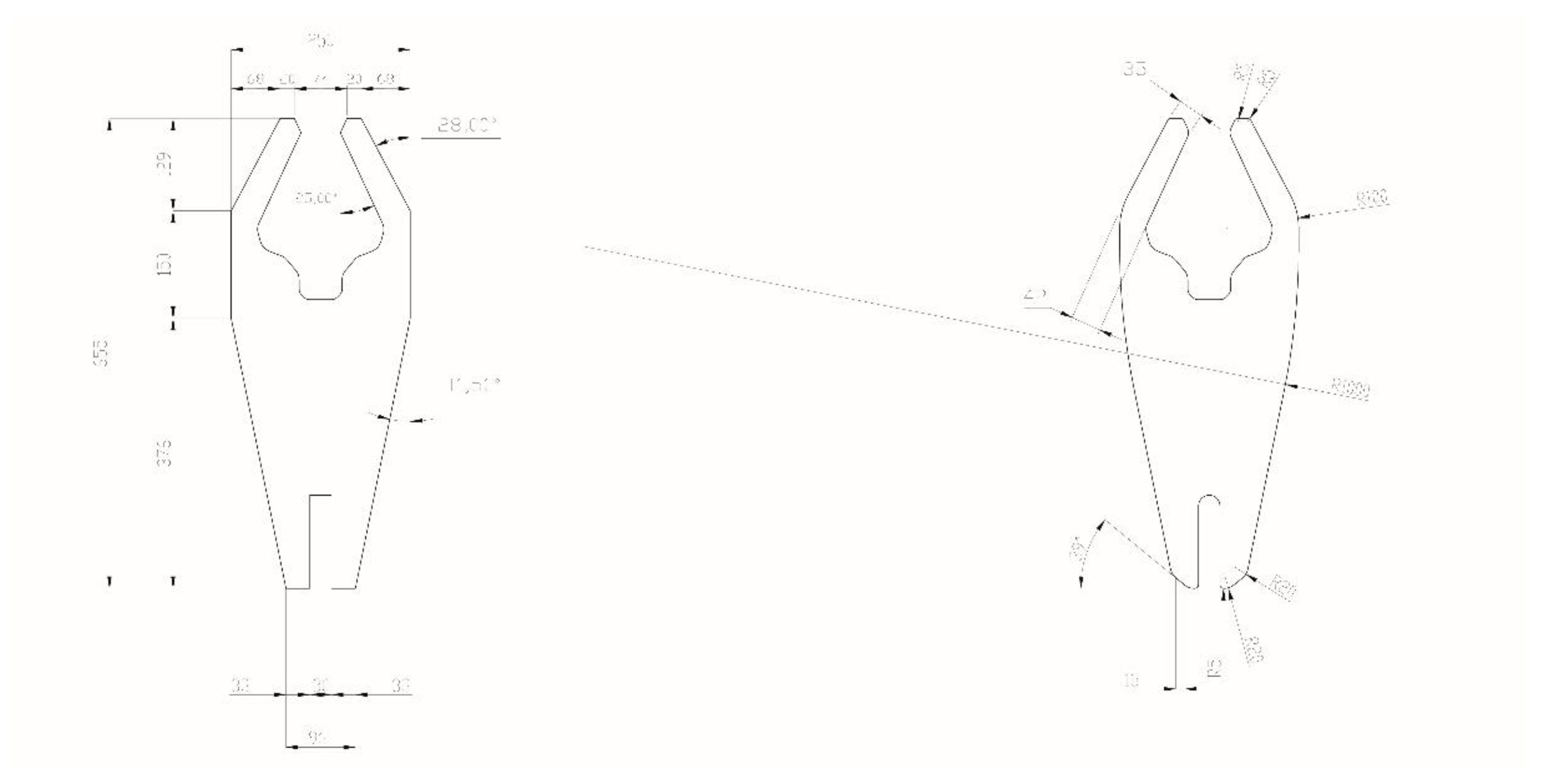

The minimum width of the platform in correspondence with the hinge is 190 mm. This measure is based on the front wheel encumbering and kinematics, consisting respectively of a 14 inches diameter and a total steering angle of 50 degrees. Starting from these dimensions, the research team defined the minimum width of the overall platform profile, which is 250 mm (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). This correspondence and anthropometric data set the basis for identifying a new design insight: users can stand on the platform placing their feet next to the other. This foot position enhances the comfort, and allows assuming an upright, stable and natural position for the body; compared to typical kick scooters, in which the platform size obliges to place the feet one in front of the other.

The research team was motivated towards a renovated formal exploration, through the design sprint method in the development of this innovative microvehicle. Therefore, they drew inspiration from the lines of the automotive sector and developed the first fast sketching aiming at conveying dynamism, innovativeness, and propensity to the future, to capture the attention of the public and define the image of the product. The selected details have been inserted in each acute and protruding intersection point, respecting the symmetry and balancing the proportions.

Regarding the selection of materials and processes, the research team examined three light and structurally valid solution possibilities, including (i) a sandwich of fiberglass with PVC core with inserts in wood at the height of the hinges; (ii) layers of bamboo, with diverse thicknesses, glued together with epoxy, with lower aluminum support; and (iii) aluminum sheets of minimum thickness with aluminum ribs. These three possible alternatives have been conceptualized physically prototyped, tested, to be inserted inside the overall LEONARDO vehicle model. The best solution to adopt was identified following the mechanical evaluations and following the partner company.

4.2. Steering Column Designing

4.2.1. Steering Column Strategic Design Brief

The focus on the Grant Agreement highlighted one of the main objectives regarding the insertion of two battery packs: an unmovable and an auxiliary one, to increase the space traveled by the vehicle. Notably, the research team defined 4 specific steering column objectives: (i) enhance the ease of use; (ii) widen the volume and size of the steering column to insert the auxiliary battery in its profile; (iii) minimize the weight through the analysis of materials and formal exploration; and (iv) supporting the “trolley mode”.

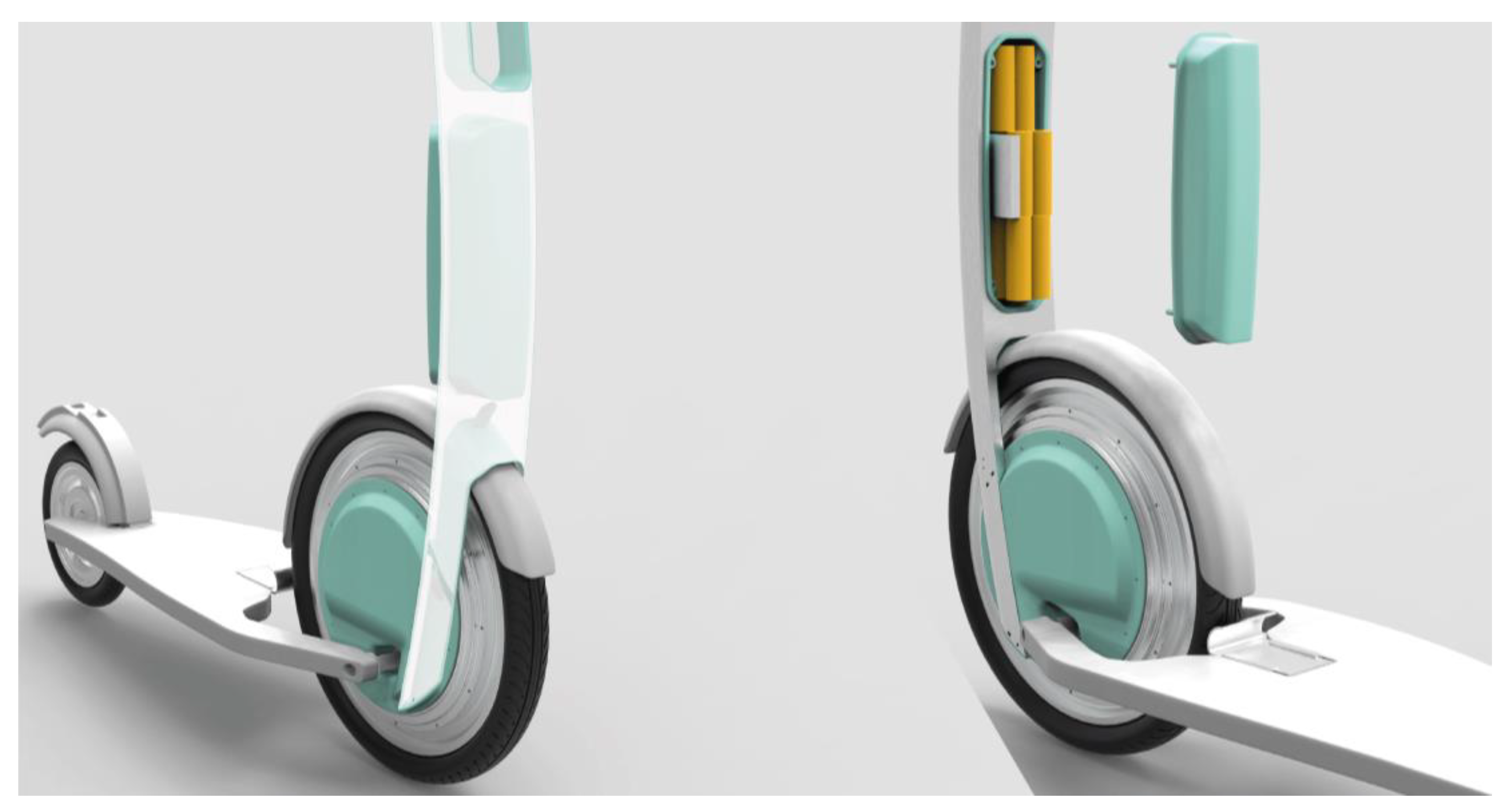

The first research objective is about improving the users' comfort, so, the research team decided to position the auxiliary battery inside the steering column for greater ease of assembly and disassembly. The second objective is about the steering column dimensioning which was designed at the height, following the standards measures commercially agreed, and at the extended section, providing enough space for the accommodation of the auxiliary and interchangeable battery case. Going on, the research phase highlighted that the hub is the only stable point on which the column can be fixed. As applicable to the whole assembly, the weight objective reflected on the research regarding suitable materials and manufacturing solutions for large-scale production. Furthermore, the research team highlighted the need to enable "trolley mode" by folding the vehicle coupling the platform and the column. So, they identified the need to seek the rear wheel appropriate position along the column, to not impact the overall aesthetics and define a compact output.

4.2.2. Steering Column Embodiment and Detailed Design

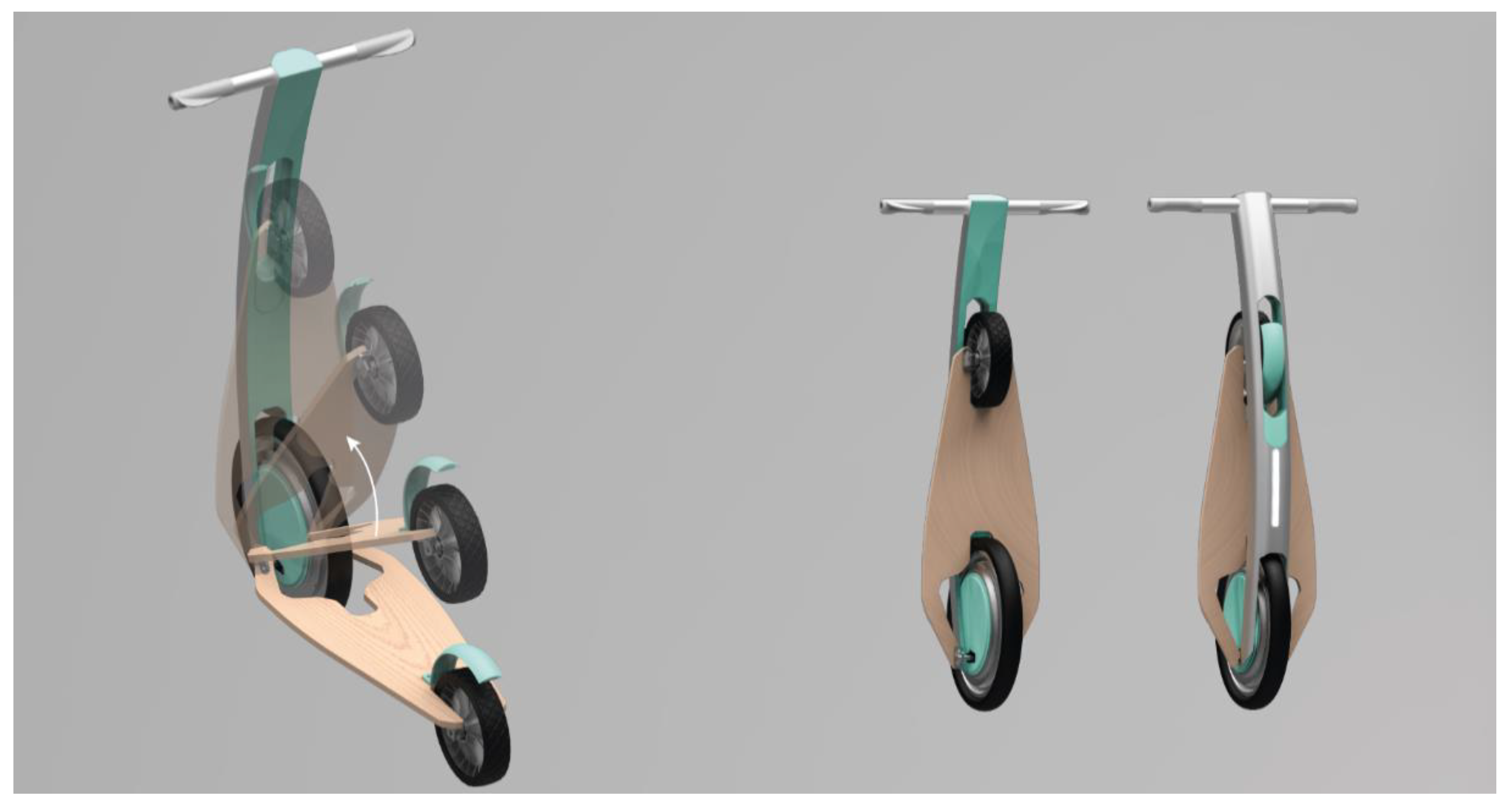

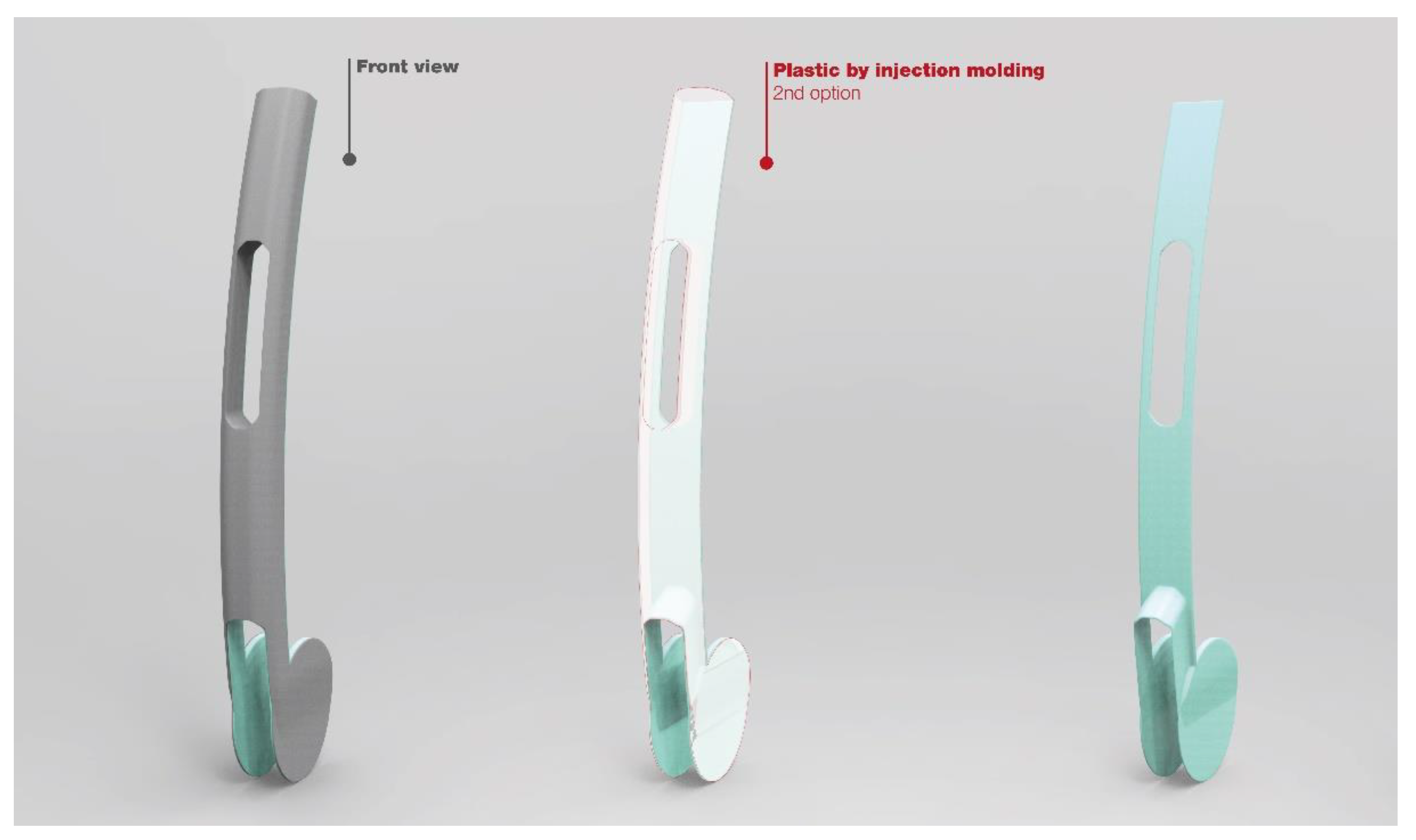

The research team dimensioned in height the steering column following the kick scooter standards. It extends by 1000 mm concerning the platform level. These measures set the basis to start formal exploration through design sprint methods, fast sketching, and disruptive co-designed ideas. The focus group with the project experts pointed out the necessity to shape and conform the aesthetic details, explored in the first research direction, into every designed component. Therefore, an aesthetic recognizable visual element was created between the platform and the steering column through the use of the parametric software Solidworks and the fillet and chamfer function on the edges. In parallel, the research team evaluated and developed the idea of creating a slot at half the height of the column. This accommodates the rear wheel inside the steering column profile and compacts the folded position of the system while minimizing the overall volume. The overall selected formal idea is harmonious with the geometry of the platform defined in the previous research direction. The design process led to the development of an innovative, minimal, dynamic concept, whose curvature invites movement and maintains a homogeneous profile, organic with the shape of the platform and the other components. These concepts are displayed and illustrated in

Figure 4.

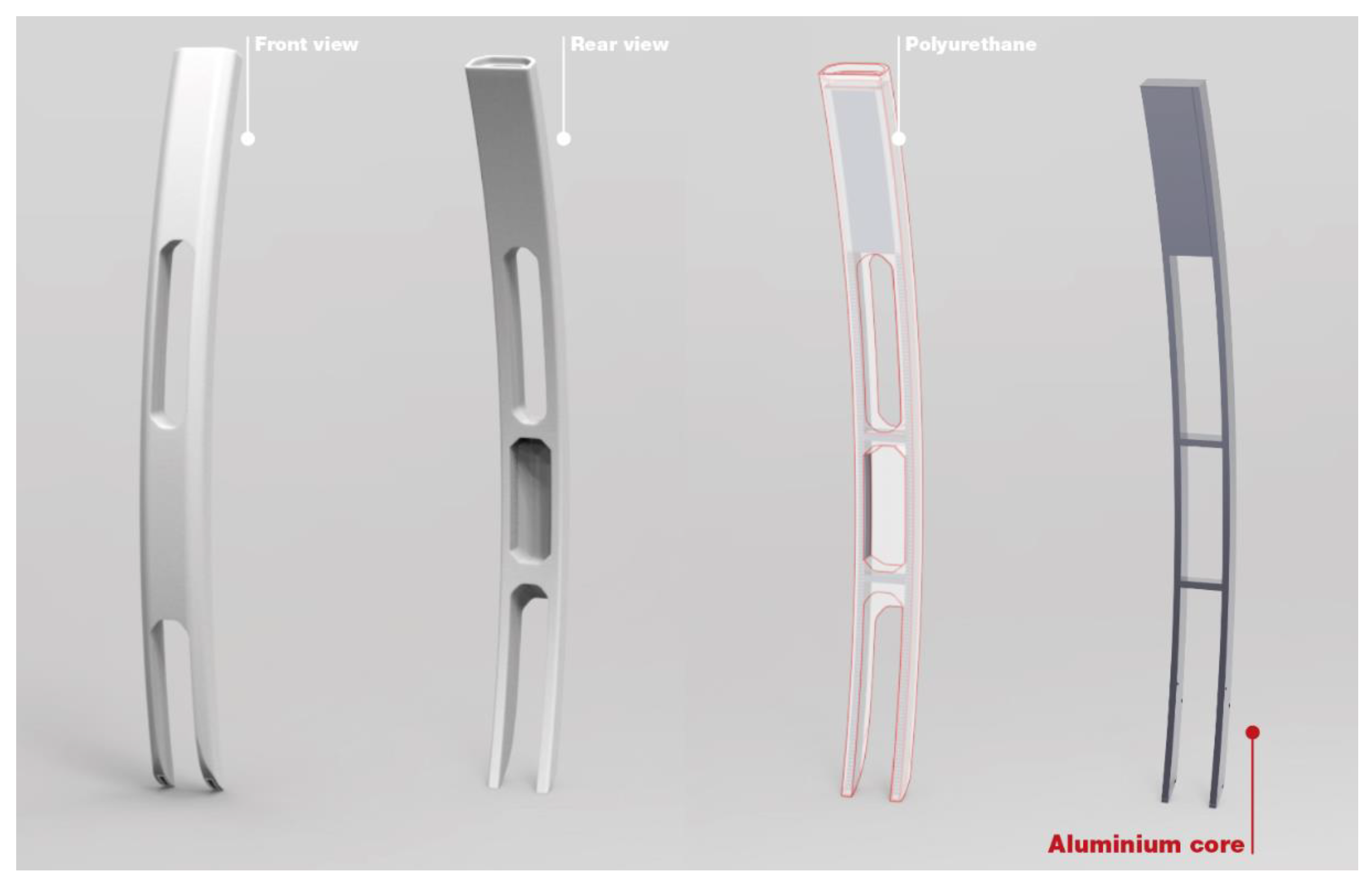

The aesthetics of the column profile section has been designed to be easily reproducible with low-cost technological processes, established within the panorama of manufacturers operating in Europe. Starting from these assumptions, 3 possible implementation solutions were analyzed. The first involves the use of polyurethane, inside which an aluminum core is co-molded, and consists of 8 components welded together (

Figure 5). The second involves the use of reinforced nylon through the injection moulding process (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). The last involves the creation of a customized extruded aluminium profile, the calendaring of the piece according to the radius of curvature considered, the laser cutting to form the central slot, the lower holes for bolts, and the housing slot for the auxiliary battery (

Figure 8). In conclusion, the research team identified the aluminum solution as the cheapest, and the polyurethane alternative as the most appealing choice from an aesthetical standpoint.

4.3. Auxiliary and Fixed Battery Case Designing

4.3.1. Auxiliary and Fixed Battery Case Strategic Design Brief

The development of the auxiliary battery case required the dimensioning of the storage on the steering column. On the other, for the fixed one, the research team needed to measure the storage on the hub. The researchers defined four specific auxiliary and fixed battery case objectives, relating: (i) the costs of the materials employed; (ii) the user comfort in inserting the case in the storage; (ii) the compactness of the case profile, to support the “trolley mode”; and (iv) ease of transport.

The design of the battery case depends on (i) the total volume occupied by the cells; (ii) the BMS; (iii) the connectors; and (iv) the adoption of the formal, recognizable, aesthetic characteristic determined in the previous subsections.

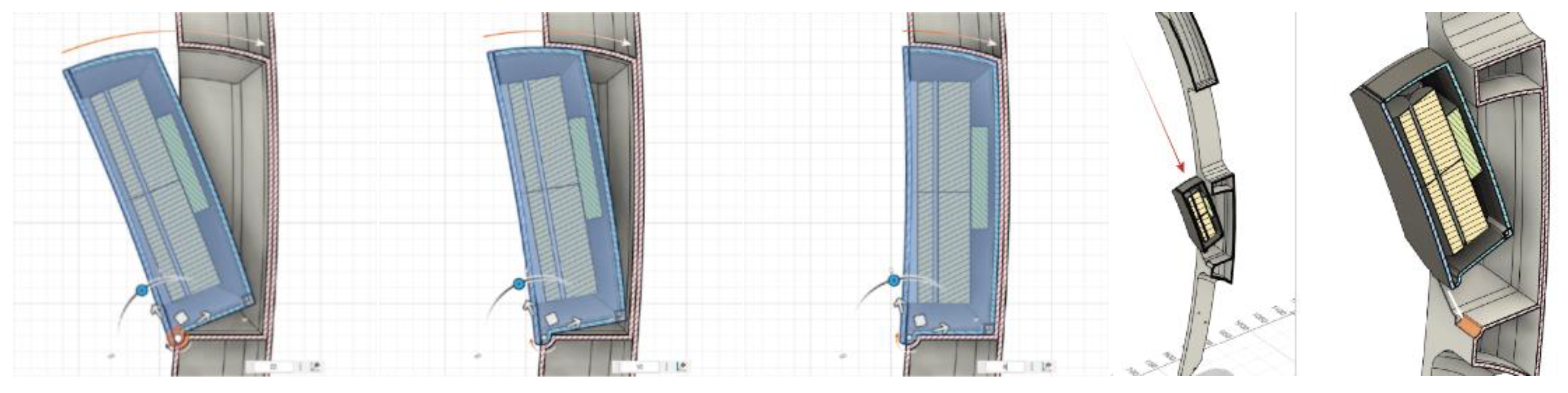

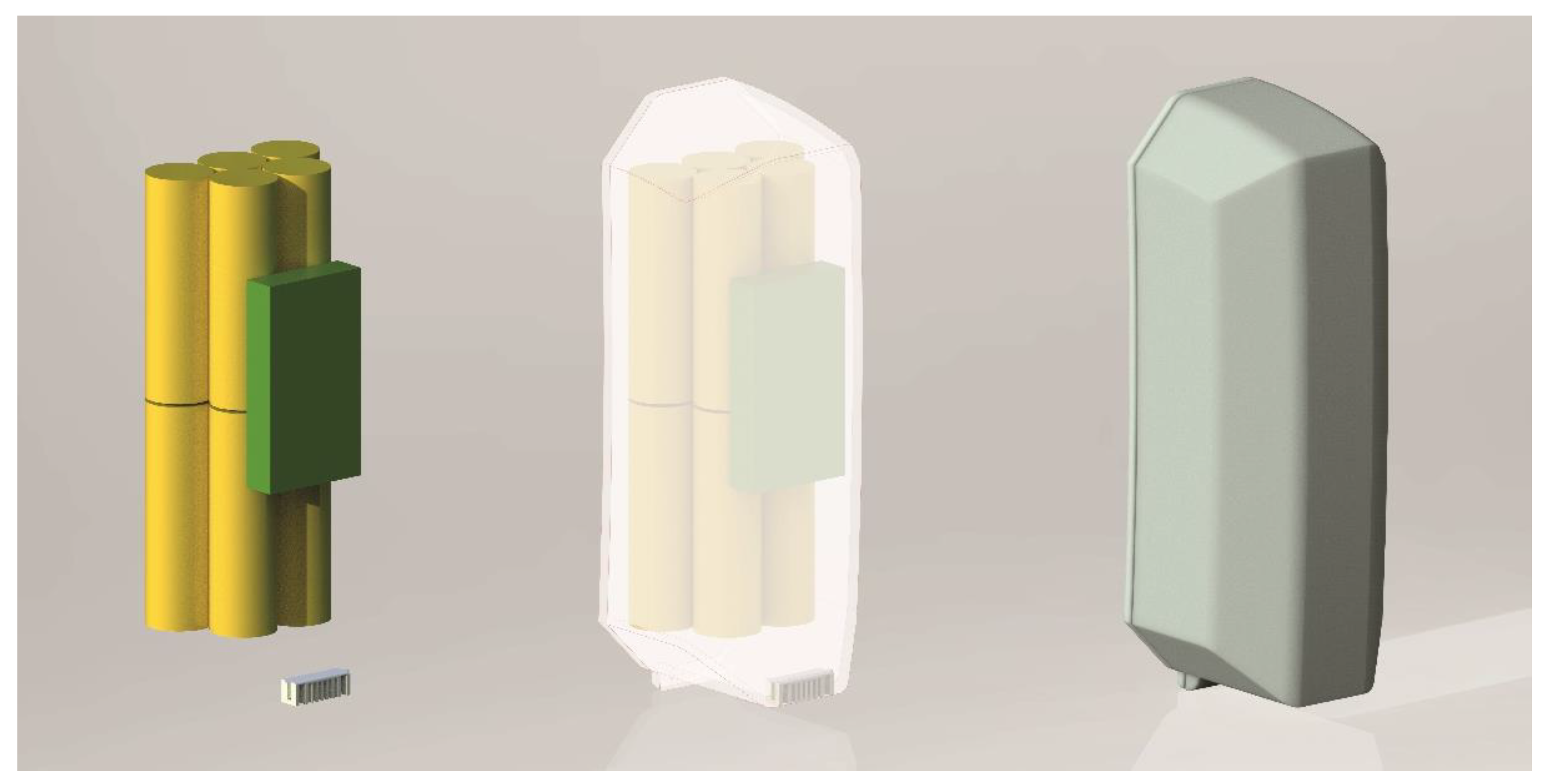

4.3.2. Auxiliary and Fixed Battery Case Embodiment and Detailed Design

The research team summarized the information acquired in the strategic brief and identified the following constraints: (i) the auxiliary battery needs at least 10 batteries that measure 18.5x69 mm each; (ii) the fixed one needs at least 20 batteries that measure 18.5x69 mm each; (ii) the BMS measurements are 69x56x15 mm; and (iii) the connector is 23.85x8.6x7 mm. In a preliminary dimensioning, the team explored the possible alternative configurations of the main auxiliary and fixed battery components, as shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. This set the basis for pointing out the steering column had no sufficient space to insert a case containing more than 10 batteries. Moreover, the research team started exploring the initial concepts by using graphical two/three-dimensional tools to better represent the inscribed auxiliary battery case. The peculiarity of the idea selected is the upper part of the case side profile, which describes the arc of a circle. The team designed this detail to foster ease of use in performing the downward movement for inserting the case and improve the user-product interaction. As depicted in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, its centre coincides with the lower end of the case housing, inside the steering column. This point was identified as the case’s pivot for insertion. The 3D models, of both the auxiliary and fixed battery case, were designed to define a preliminary 3D printing prototype. Anyway, the team selected the reinforced nylon and the injection molding process as a manufacturing process. Therefore, the model was designed to be extracted from the mold during production.

4.4. Assembly Designing

4.2.1. Assembly Prototyping and Testing

The closing of the research process, in correspondence to the end of the second diamond, combined the research directions findings in a single product assembly: the newly silent, clean, energy-efficient, and safe microvehicle. This blended version of the existing personal light electric vehicle employs a control mechanism where, similarly to the monowheel mechanisms, the users should push the steering column to accelerate and pull it for decelerating. This highly improved the perceived user experience. The remote quantitative usability testing, indeed, highlighted presented a positive response to the question “Perspicuity. Is it easy to get familiar with the product and to learn how to use it?”, with the following results: 14,8% voted 4/7; 33,3% voted 5/7; 37% voted 6/7; 14,8% voted 7/7.

Going on, following the partner company, the research team developed the first generation of the scooter prototype (presented in

Figure 13), which consisted of (i) the location of the main axle at the lower part of the front wheel; (ii) the steering column; (iii) the presence of the fixed battery compartment and the corresponding 3D printed case; and (iv) the deck, made of a sandwich structure.

5. Discussion

The paper's introduction highlights how an interdisciplinary collaboration in the design of urban mobility products could be a source of value creation. The researchers, therefore, structured a critical literature review on Design thinking and highlighted the coherent Design Framework for Innovation, the Double-Diamond design thinking model, to adopt for achieving research challenges and defining disruptive and novel outputs in a transdisciplinary way. Hence, the cross-disciplinary research team evaluated the findings in the context of the H2020 LEONARDO project, which addresses the limitations of current micromobility solutions.

As discussed in the last two sections, the results of the present research context confirmed the assumption and set the basis for re-elaborating the design model, presented in

Figure 1. Notably, the application of the methods and tools relating to the first diamond widened the opportunities to conceptualize the overall model. The analysis and synthesis of the data gathered in the research phase, indeed, provided the researchers with different inquiry directions to be addressed for supporting the development of the electric microvehicle. These findings set the basis for splitting the current strategic design brief into 3 research directions, relating 3 different product components, that fall under the mutual objective of designing an innovative micromobility vehicle based on the smart fusion of the monowheel and kick scooter concepts. Moreover, the research tasks of the second diamond were addressed 3 times, as to how many inquiry directions the research team identified, and one additional time for merging the final results in the product assembly. These results were fundamental in clarifying the design research process to apply for the innovative development of urban transport products.

Figure 14 presents a summary graphic representation of the discussions. In other words, the research team framed “an interdisciplinary double-diamond design thinking model for urban transport product innovation” characterized by (i) guidelines for organizing and structuring the research process, in

Figure 15; (ii) macro and micro design research tasks to address, in

Figure 15; (iii) interdisciplinary methods and tools to be undertaken, in

Figure 15; and (iv) a novel interpretation of the second diamond, in

Figure 14. The last feature of the design model highlights the actual diversification, compared to the Double-Diamond presented in

Figure 1. Notably, it emphasizes the parallel development process of the product components, the recurring adoption of the research activities, proper of the “Develop” and “Deliver” phases, for each of them, and how these research directions are inscribed in the second diamond, that is in the development of the product assembly.

Therefore, the research team widens the vision of the second diamond, explaining that foresees a constant and repetitive adoption of the research tasks for every research direction the design practitioners identify, in the initial process phase. The researchers highlight and support the need to identify and map the components of the mobility product assembly, for delineating a wider variety of design potentials and giving design experts more opportunities to visualize insights for interventions.

Figure 14.

Interdisciplinary Double-Diamond Design Thinking model for urban transport product innovation. Figure presents the novelty of the design model and the corresponding research macro tasks. Re-elaboration of the ‘Double-diamond design thinking model’ [

26].

Figure 14.

Interdisciplinary Double-Diamond Design Thinking model for urban transport product innovation. Figure presents the novelty of the design model and the corresponding research macro tasks. Re-elaboration of the ‘Double-diamond design thinking model’ [

26].

Figure 15.

Interdisciplinary Double-Diamond Design Thinking model for urban transport product innovation. The Figure presents the design research macro and micro tasks and tools and methods to employ for mobility product innovation. Re-elaboration of the ‘Double-diamond design thinking model’ [

26].

Figure 15.

Interdisciplinary Double-Diamond Design Thinking model for urban transport product innovation. The Figure presents the design research macro and micro tasks and tools and methods to employ for mobility product innovation. Re-elaboration of the ‘Double-diamond design thinking model’ [

26].

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the research team adopted the Double-Diamond Design Thinking Model in a transdisciplinary context for developing an innovative micromobility vehicle. Notably, they designed the hierarchical research process, the four stages of development, and the macro and micro tasks to undertake an innovative micromobility solution, tools, and methods to employ in the four stages of development. The project research context of “Leonardo” is an exploratory case study in which the team sought to answer the research questions through the application of the Double-Diamond model. During the process, the team correlated and employed mixed methods in both the design and engineering disciplinary sectors, involving stakeholders, project experts, design and engineering researchers, and practitioners through the design of participative research activities. The researchers obtained both qualitative and quantitative data. Consequently, the emerging findings set the basis for the iteration of the graphic representation of the design model and led to the framing of the “Interdisciplinary Double-Diamond Design Thinking model for urban transport product innovation”. This design model aims to let design and engineering researchers and practitioners adopt, replicate, and scale the process the team developed. Finally, the research team argues this novel design model has the potential, as a design research instrument, to be capable of addressing sustainable mobility and guiding interdisciplinary design research, design practice, and education in the Industrial Engineering and Design disciplinary sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.V., A.R., and D.V.; methodology, S.V.; investigation, M.S.G., and D.V.; data curation, S.V., and M.S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.V. and A.R.; writing—review and editing, M.S.G. and D.V.; visualization, S.V. and M.S.G.; supervision, A.R. and D.V.; project administration, D.V.; funding acquisition, D.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Commission, grant number 101006687. The APC was funded by the European Commission, grant number 101074307. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Data Availability Statement

No processed data is associated with the present work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the other partners of the LEONARDO research team for their valuable work and contribution to the development of material included in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rohilla, K., Desai, A. & Patel, C.R. A Cutting-Edge Examination of the Dichotomy of Electric Vehicles as a Symbol of “Sustainable Mobility” and “Clean Energy”. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. A, 2024, 105, 209–227. [CrossRef]

- Santacre A., Yannis, G., de Saint Leon, O., Crist, P. Safe micromobility. 2020, from https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/safe-micromobility_1.pdf.

- Khamis, A. Smart Mobility: Exploring Foundational Technologies and Wider Impacts; Publisher: Apress Berkeley, CA, 2021.

- Cordis. MicrovehicLE fOr staNd-Alone and shaReD mObility – LEONARDO. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101006687 (accessed on 08/08/2024).

- Micheli, P., Wilner, S. J. S., Bhatti, S. H., Mura, M., & Beverland, M. B. Doing design thinking: Conceptual review, synthesis, and research agenda. JPIM 2019 Journal of Product Innovation Management, 36(2), 124–148. [CrossRef]

- Verganti, R., Dell’Era, C., & Swan, K. S. Design thinking: Critical analysis and future evolution. JPIM 2021 Journal of Product Innovation Management, 38(6), 603-622. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Liu W. How to develop engineering students as design thinkers: A systematic review of design thinking implementations in engineering education. In ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Baltimora, Maryland, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Alok, G.; Pothupogu, S.; Reddy, M. S.; Sai Priya P.; Devi V., R. D. Trenchant Pathway to bring Innovation through Foundations to Product Design in Engineering Education. In IEEE 6th International Conference on MOOCs, Innovation and Technology in Education (MITE), Hyderabad, India, 2018, pp. 43-47. [CrossRef]

- Kaygan, P. From forming to performing: team development for enhancing interdisciplinary collaboration between design and engineering students using design thinking. International Journal of Technology and Design Education 2023, 33, 457–478. [CrossRef]

- Turcios-Esquivel, A. M. L.; Avilés-Rabanales E. G.; Hernández-Rodriguez, F. Enhancing Empathy and Innovation in Engineering Education Through Design Thinking and Design of Experiments. In IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Kos Island, Greece, 2024, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Leem, S., & Lee, S. W. Fostering collaboration and interactions: Unveiling the design thinking process in interdisciplinary education. Thinking Skills and Creativity 2024, 52, 101520. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Using design thinking for interdisciplinary curriculum design and teaching: a case study in higher education. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, 307. [CrossRef]

- Panke, S. Design Thinking in Education: Perspectives, Opportunities and Challenges. Open Education Studies 2019, 1, 281-306. [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. Design thinking: achieving insights via the “knowledge funnel”. Strategy & Leadership 2010, 38, 37-41. [CrossRef]

- Rösch, N., Tiberius, V. and Kraus, S. Design thinking for innovation: context factors, process, and outcomes. European Journal of Innovation Management 2023, Volume 26 N. 7, 160-176. [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M. G. A brief introduction to design thinking. In Design thinking: New product development essentials from the PDMA; Luchs, M. G., Swan, S., Griffin, A.; Publisher: Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey, U.S., 2016; pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Carlgren, L., Rauth, I., Elmquist, M. Framing design thinking: The concept in idea and enactment. Creativity and Innovation Management 2016, 25, 38-57. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, R. Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Design Issues 1992, 8(2), 5–21. [CrossRef]

- Kueh, C. & Thom, R. (2018). Visualising Empathy: A Framework to Teach User-Based Innovation in Design. In Visual Tools for Developing Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Capacity; Griffith, S., Carruthers, K., & Bliemel, M. Eds.; Champaign, IL: Common Ground Research Networks; pp. 177-196. [CrossRef]

- Peng, F. (2022). Design Thinking: From Empathy to Evaluation. In: Foundations of Robotics, Herath, D., St-Onge, D., Eds.; Springer, Singapore; pp. 63-81. [CrossRef]

- Frog. Empowering communities with Design-thinking. Available online: https://www.frog.co/designmind/collective-action-toolkit-empowering-communities (accessed 08/08/2024).

- Cross, N. Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work, 2nd ed.; Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, London, 2023.

- d.School. Design Thinking Bootleg. Available online: https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources/design-thinking-bootleg (accessed 08/08/2024).

- IDEO. Design KIT: The Human-Centered Design Toolkit. Available online: https://www.ideo.com/journal/design-kit-the-human-centered-design-toolkit (accessed 08/08/2024).

- DESIGN KIT. The Field Guide To Human-Centered Design. Available online: https://www.designkit.org/resources/1.html (accessed 08/08/2024).

- Design Council. The Double Diamond. Available online: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/the-double-diamond/ (accessed on 08/08/2024).

- Stickdorn, M.; Schneider, J. This is Service Design Thinking: Basics, Tools, Cases; Publisher: Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey, U.S., 2012.

- Kochanowska, M., Gagliardi, W.R., with reference to Jonathan Ball. The Double Diamond Model: In Pursuit of Simplicity and Flexibility. In: Perspectives on Design II, Raposo, D., Neves, J., Silva, J. (eds); Springer Series in Design and Innovation, vol 16. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Design Council. Design methods for developing services. Available online: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/fileadmin/uploads/dc/Documents/DesignCouncil_Design%2520methods%2520for%2520developing%2520services.pdf (accessed 08/08/2024).

- Tosi, F. Design for ergonomics; Publisher: Springer Cham, 2020; pp. 111-128. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Chao, CJ., Fu, Z. (2020). Research on Intelligent Design Tools to Stimulate Creative Thinking. HCII 2020, vol 12192.

- Cross, N. Engineering design methods. Strategies for product design, 5th ed.; Publisher: Wiley, Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey, U.S., 2021.

- Guaman-Quintanilla, S.; Everaert, P.; Chiluiza, K.; Valcke, M. Fostering Teamwork through Design Thinking: Evidence from a Multi-Actor Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 279. [CrossRef]

- Bordegoni, M.; Carulli, M.; Spadoni, E. User experience and user experience design. In Prototyping user experience in extended reality; Bordegoni, M., Carulli, M., Spadoni, E.; Publisher: Springer, Cham, 2023; pp. 11-28. [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, A. Innovare attraverso il design e la tecnologia; Publisher: FrancoAngeli, Milano, 2020; pp. 49-69.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Heidi, J. Content analysis. In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Given, L.M., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 120–122.

- Miro. Available online: https://miro.com/it/ (accessed 08/08/2024).

- Knapp J, Zeratsky J, Kowitz B. Sprint: how to solve big problems and test new ideas in just five days. Publisher: Simon and Schuster, New York, 2016.

- Magistretti, S.; Dell’Era, C.; Doppio, N. Design sprint for SMEs: an organizational taxonomy based on configuration theory. Manag Decis 2020, 58(9), 1803–1817. [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, A., Busciantella-Ricci, D., Viviani, S. (2024). Design for Movability: A New Design Research Challenge for Sustainable Design Scenarios in Urban Mobility. In For Nature/With Nature: New Sustainable Design Scenarios; Gambardella, C. (eds); Publisher: Springer, Cham, 2024; Volume 38, pp. 929-949. [CrossRef]

- Primus, D. J., & Sonnenburg, S. Flow Experience in Design Thinking and Practical Synergies with Lego Serious Play. Creativity Research Journal 2018, 30(1), 104–112. [CrossRef]

- Godin, D., and Zahedi, M. Aspects of Research through Design: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of Design's Big Debates - DRS International Conference 2014, Umeå, Sweden, 16-19 June 2014.

- Pheasant, S., Haslegrave, C.M. Bodyspace. Anthropometry, Ergonomics and the Design of Work, 3rd ed.; Publisher: CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2006.

- Gulino, S. M., Vichi, G., Zonfrillo, G., Vangi, D. Comfort assessment for electric kick scooter decks. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1214, 012043. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).