1. Introduction

Uruguay is a country located in South America, between 30° and 35° South latitude and meridians 53° and 58° West longitude, in the temperate zone of the Southern Hemisphere [

1]. With a land area of 176,215 km², it borders Brazil to the north and northeast, to the west with Argentina, and to the south and southeast, it has coasts on the Río de la Plata and the Atlantic Ocean [

2]. According to the 2023 Census, the preliminary estimated population is 3,444,263 people, with an estimated intercensal growth rate of 1% [

3].

The country advances its energy transition towards a more efficient and sustainable economy, positioning itself on top of other countries in electricity generation based on renewable sources, a model to follow globally [

3,

4]. As a result, the country has practically decarbonized its electricity matrix, complementing the traditional participation of hydroelectric energy with the incorporation of wind, solar, and biomass energy [

5].

At the end of 2023, the total installed capacity was 1538 MW of hydraulic origin, 1517 MW of wind power, 1177 MW of fossil thermal, 731 MW of biomass thermal, and 301 MW of solar photovoltaic generators. Considering the installed capacity by source, 78% corresponded to renewable energy (hydro, biomass, wind, and solar), while the remaining 22% was non-renewable energy (diesel, fuel oil, and natural gas).

Considering the country’s situation, with a practically decarbonized electricity matrix, Uruguay is ready for new challenges. One of them was presented in 2022 by the government: hydrogen production. In onshore territory, they considered the complementarity of wind and solar resources or offshore territory by offshore wind farms. The excellent offshore wind resource and a broad continental shelf with low water depths make it attractive for producing hydrogen and derivatives from offshore wind energy [

6]. By 2040, hydrogen production on its coast could reach up to one million tons annually [

5]. Considering some criteria such as protected areas and nautical routes, the National Administration of Fuels, Alcohol and Portland (ANCAP), the representative of the Uruguayan government, selected a particular zone divided into four regions for the initial round of offshore H2U bids.

The offshore green hydrogen production and transportation concepts are entirely new, and even the methodology for a comprehensive sustainability assessment is mainly undeveloped [

7]. The conversion of offshore wind energy into hydrogen (or one of its derivatives, like ammonia) gives flexibility to the electrical system. It facilitates the management of the variability of the wind energy source [

8]. Even though offshore wind farms are a little more advanced than hydrogen production, they are still a novelty in many countries worldwide, with no established environmental regulations. This article aims to review Uruguay’s situation in this area.

A comprehensive literature review was done, including journal and review papers, documents from offshore wind farms in operation, books, and scientific reports to understand the environmental and social impacts of wind farms installed worldwide. Additionally, the ecological characteristics of the current state of the Uruguayan coast and its regulations related to installing wind farms onshore are examined.

2. Background Context

2.1. Offshore Wind Farms

In the last decades, growing efforts have been made to reduce CO2 emissions and other pollutants that increase global warming effects [

9]. The offshore wind energy industry now plays a central role in the long and short-term international energy strategies. Future power scenarios and roadmaps promote offshore wind farms as an alternative and additional power generation source [

10]. For this, developers look into wind, wave, and sea bed conditions, availability of foundation and turbine types and installation ships, and the wind farm layout, considering cabling and projected operation and maintenance costs [

11]. Up to 2023, fourteen countries were part of the Global Offshore Wind Alliance; the more mature European markets included countries like Denmark, the UK, and the Netherlands [

12].

Most offshore wind farms built thus far are based on waters below 30 m deep, using big-diameter steel monopiles or a gravity base. Considering water depths beyond 50 m, there is a new line of investigation focused on the usage of floating structures; TLP (tension leg platform), Spar (large deep craft cylindrical floating caisson), and semi-submersible are the most studied [

13].

During the first stage of the design, several different exclusion zones have to be managed, such as nature reserves, shipping lanes, oil exploration areas, risks of unexploded ordnance, or the chances for finding archaeological remains [

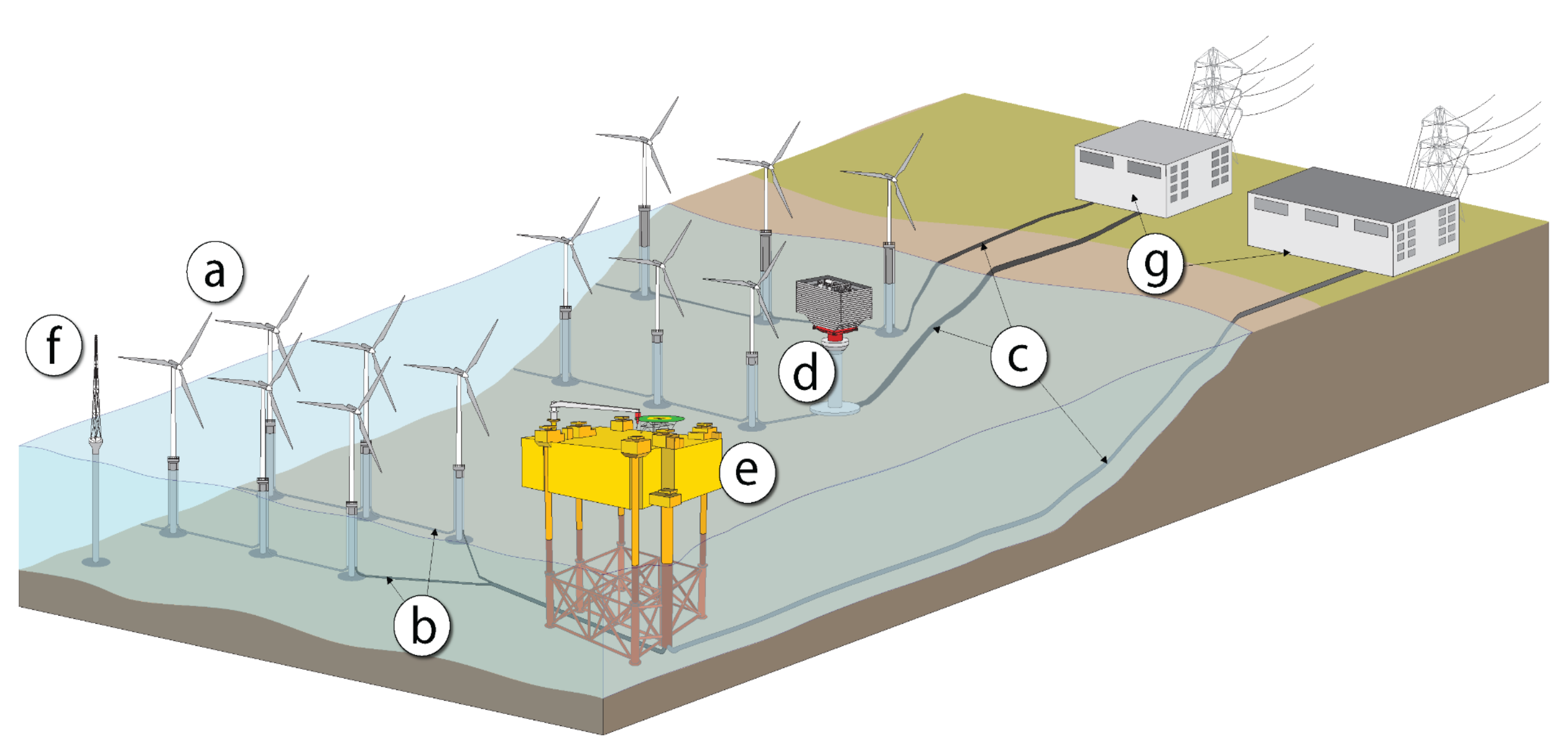

11]. As shown in

Figure 1 [

14], an offshore wind farm comprises different components that can cause environmental and social impacts.

2.2. Global Overview of Offshore Wind Energy

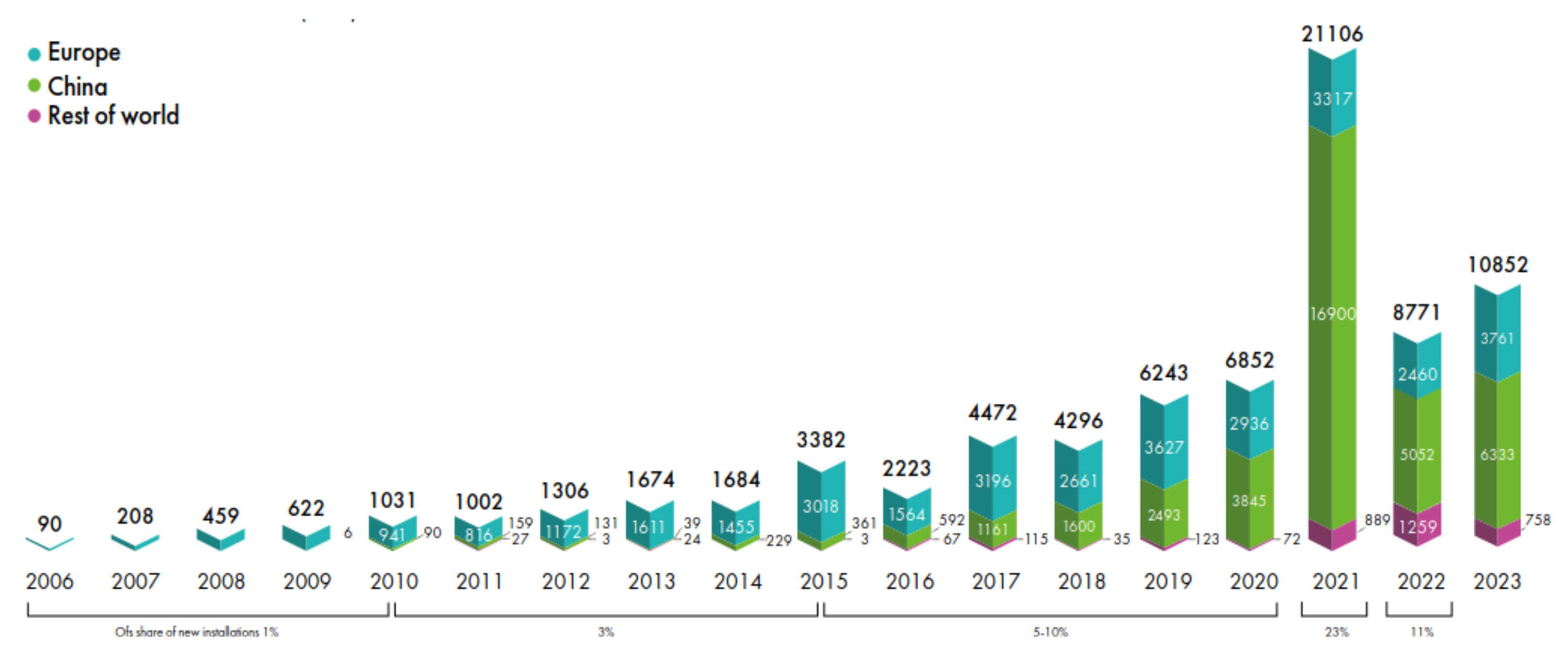

By the end of 2023, the installed capacity of offshore wind farms worldwide was 72.5 GW, corresponding to approximately 7.3% of the total installed wind power capacity (onshore+offshore) worldwide [

15]. Of this installed offshore wind capacity, China owns 50.3%, followed by the United Kingdom with 19.6% and Germany with 11.1%.

By region, Europe stands out with 45.3%, Asia-Pacific with 54.6%, and North America with 0.1% of the total installed capacity worldwide [

16].

Figure 2 shows the evolution of new offshore wind installations worldwide.

One of the main technological advances has been in the manufacturing characteristics of offshore wind turbines, which have had increasing values of rated power (MW), rotor diameter (m), and hub height (m). Due to technological development, the global weighted average Levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) of offshore wind power has gone from 0.197 USD/KWh in 2010 to 0.081 USD/KWh in 2022, a reduction of 59% [

17]. In the given context of decreasing costs due to the advancement of technology and in search of mitigating CO2 emissions in the earth’s atmosphere, the trend is that the installed capacity of offshore wind farms will continue to increase in the coming years.

Wind energy, a relatively recent energy source in terms of participation in electricity generation worldwide, still faces significant challenges in achieving greater efficiency in its integration into electricity systems. Among these challenges are issues specifically related to offshore wind, such as deepwater foundation technologies, resource characterization in the marine atmospheric boundary layer [

18,

19], environmental aspects, and socio-economic impacts [

20,

21].

The primary differences between offshore and onshore wind farm projects can be observed in the construction, operation, maintenance (O&M), and decommissioning processes. During the construction phase, offshore projects require using platforms, cables and networks, substations, dredging, and other construction elements unique to the offshore environment. Operations and maintenance (O&M) activities include the transportation of personnel by ship or helicopter and occasional modifications to equipment [

22]. The potential for these activities to generate noise that could affect underwater fauna has been the subject of recent investigations and will be a primary focus of this study.

3. Literature Analysis

Social and Environmental Impacts

The collected data is mainly from the North Sea, Denmark, Germany, and the United States coasts. The main effects caused by implementing offshore plants in these places and their causes are listed in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4. It is essential to mention the biological differences between these coasts and the Uruguayan ones so that the impacts, although helpful in obtaining an initial perception, could vary widely.

4. Characterization of the Uruguayan Coastline

4.1. Environmental Condition

At the marine level, the Uruguayan Exclusive Economic Zone (UEEZ) constitutes a particularly relevant area for biodiversity on a global and regional scale [

23]. It is subject to the variability presented by the confluence of the warm Brazilian current with the cold Malvinas current and the discharge of fresh water from the Río de la Plata, constituting a highly productive and dynamic region [

23]. It has a significant impact on fishing and the availability of food for commercial fish and other marine animals [

24].

In particular, this marine region has been globally recognized for its richness in various biological groups, including pelagic species such as cetaceans and sharks. It is also a breeding, feeding, and/or reproduction habitat for turtles, birds, and sea lions [

23].

Bird species, such as the royal tern (Thalasseus maximus) and the kelp gull (Larus dominicanus), nest on the coastal islands of Uruguay and feed in the adjacent sea. Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) use the area to feed while they migrate to reproduce. Regarding marine mammals, along the Uruguayan coast and islands, there are settlements of sea lions (Arctocephalus australis, Otaria flavescens) who search for food in the area [

24].

Additionally, several species of whales and dolphins are found depending on their migratory patterns. Furthermore, several populations of bony fish, such as croakers (Micropogonias furnieri) and tunas (Thunnus spp.) and cartilaginous fish—sharks and rays—feed, reproduce, migrate and breed in Uruguayan ocean waters [

24].

It is known that for many species of birds, turtles, marine mammals, and sharks, the interaction with fishing activity constitutes one of the main threats to their survival, along with pollution of the marine environment, habitat degradation, and the relationship with introduced species [

24].

4.2. Social Aspect

The coastal zone of Uruguay on the Río de la Plata and the Atlantic Ocean is approximately 714 km long (of which 478 km correspond to the Río de la Plata and 236 km to the Atlantic Ocean). It consists of a strip of land and sea space of variable width where sea-land interactions occur. This area generates 75% of the national GDP and houses 70% of the population. Montevideo has the most significant maritime commercial exchange port in Uruguay, and the surrounding area is active in industrial and artisanal fishing [

23]. The fishing industry in Uruguay is based on extracting croaker, hake, and fish, which landed mainly through the port of Montevideo (FAO United Nations, 2019). It contributes to the national economy by creating employment in the commercial balance and as part of the national food supply.

The species that landed the most in 2016–2018 were shad, croaker, and menhaden, totaling between 74 and 76% of the total artisanal catches [

25]. Industrially, hake is the main fished species. On the other hand, the croaker is the second-fished species. Although it has decreased recently, it has remained much more stable.

Regarding tourism, statistical data from the Ministry of Tourism issued on April 21, 2023, on the number of visitors was revised. Of the areas tourists chose in 2023, 48% are characterized by their coasts, including destinations such as Punta del Este, Costa de Oro, Rocha, and Piriápolis. On the other hand, cities such as Montevideo or Colonia represent 24% of tourist reception during the year. Regarding total spending, the Ministry of Tourism estimates that 75% of the expenditure of all tourists in the country is made in the coastal areas mentioned above.

4.3. Onshore Wind Farms Regulation in Uruguay

Regulations already applied in the local terrestrial environment are a possible consideration for those carried out in marine plant activities. These must meet a balance of requirements and obligations, depending on the differences in the regulatory framework between the two. The Ocean Renewable Energy Action Coalition indicates that it is essential that policies and regulations are synchronized with clear objectives, contributing to the reduction of risk and stimulating investment [

26].

In Uruguay, three key environmental authorizations are required to implement the installation of wind farms: the Environmental Feasibility of the Site (VAL), the Prior Environmental Authorization (AAP), and the Environmental Authorization of Operation (AAO). The National Directorate of the Environment (DINAMA), belonging to the Ministry of the Environment, is responsible for issuing these authorizations [

27].

Implementing power generation plants with a capacity greater than 10 MW in Uruguay requires obtaining the Environmental Feasibility of the Site (VAL), as established by the Regulation of Environmental Impact Assessment and Environmental Authorizations, approved by Decree 349/2005. This regulation requires that the location and description of the plant’s influence area include an analysis of possible alternatives. Also, plants exceeding 10 MW need a Prior Environmental Authorization (AAP), which must comply with the territorial planning criteria established in the Territorial Planning and Sustainable Development Law. Finally, once the AAP is obtained, it is necessary to get the Environmental Operating Authorization (AAO) renewed every three years to continue operating legally [

27].

5. Studies Required for Offshore Licensing in Uruguay

To mitigate the impacts of offshore wind farms and strengthen the resilience of coastal ecosystems, it is crucial to adopt approaches that conserve biodiversity, promote habitat restoration, and consider the interaction between urbanization and climate change. Protecting and effectively managing coastal areas are essential to guarantee the continuous provision of ecosystem services and the sustainability of Uruguay’s coastal ecosystem [

23].

Strategic planning at a regional or national level allows wind farm developers to identify the areas that are likely to encounter serious objections regarding these impacts [

22]. However, some effects may be inevitable or even unpredicted, and therefore, mitigation during construction, operation, and decommissioning is very valuable.

The selection of the site for a wind farm is a very critical issue that determines to a great extent its success from a technical, economic, social, and environmental perspective [

22]. In the beginning, the polygonal security area of the project must be represented, presenting possible navigation routes and options for location adjustments in the distribution of towers and in the protection of cables/moorings [

28]. Concerning the protection of birds, some areas have to be avoided since they are known to be migratory routes for many birds. Even in cases where birds or even mammals avoid wind farms, the result is that they spend much more energy, meaning that there is a high probability of population reduction [

22]. To control and mitigate the environmental impacts and recurring use conflicts in this type of undertaking (mainly those related to tourist activities, impacts to the landscape, shorebirds, corals, greater environmental sensitivity of shallow areas, and creation of regions excluding fishing), the evaluation of the distance from the coast is recommended [

28].

Any potential developer of an offshore wind farm must also undertake a seascape and visual impact evaluation as part of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process. The main purpose of EIA is to ensure that the impacts of a development or activity are identified and mitigated where possible [

22]. They are used globally to manage the environmental impacts of human activities, identify project risks to avoid adverse effects, and adopt mitigation and compensation measures [

21].

In this EIA, the compatibility of the undertaking with the applicable legislation, plans, government programs, and zoning, proposed or in execution, as well as possible legal prohibitions regarding the implementation and operation of the undertaking or activity, must be analyzed [

28], considering technical standards that address maximum parameters of negative externalities for noise, water quality, and navigation safety.

For Uruguay, this refers mainly to compatibility with current environmental regulations, such as those established by the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulation of the National Directorate of the Environment.

In this context, identifying the public attitude before initiating a project idea contributes to the site selection procedure and the whole design, which is supported by planning and simulation tools. Thus, the visual impact assessment is analyzed using appropriately designed software platforms that can simulate various views and evaluate public reactions before the project is implemented [

22].

Furthermore, the area designated for the construction site should be characterized, including the layout and description of its units, mechanical workshops, and supply stations, presenting the estimate of road, port, and maritime traffic [

28]. Evaluation of technological alternatives taking into account the technical, economic, and environmental aspects have to be studied to minimize ecological impacts in wind energy generation projects, considering the type of cement, the height of towers, rotation speed, the color of structures, lighting, and identification of the risk of bird collision [

28].

Included in the EIA must be the spatial and temporal identification of areas of concentration, reproduction, feeding, and migratory routes by species [

28], as well as the description of the structure of the populations through indicators (diversity, distribution, and abundance), identifying potentially sensitive species based on their auditory perception spectra and modeling of noise emission, by frequency.

In the preliminary process, Uruguay must consider possible activities in the area, such as fishing, tourism, migratory routes, and environmentally protected zones to delimit the areas. It must characterize in depth the sea lion islands, the migratory patterns of marine mammals and coastal birds, and the fish species found in the region, which are essential for its economy and habitat conservation.

In the specific field, one should consider the involvement of various types of scientists originating from different subject areas, such as communication, sociology, psychology, biology, and strategic planning; the interaction of all these other experts promotes the understanding and comprehension of the opinion of local societies [

22].

Updated, integrative, and systematic scientific information on the risk of each potential interaction between OWFs and different ecosystem elements is needed to inform managers and decision-makers during planning [

21]. Still, we must acknowledge significant scientific discrepancies regarding the magnitude of OWF impacts, as highlighted by the lack of evidence on assessing ecological risks associated with OWF projects [

21].

6. Discussion

Uruguay finds itself able to advance in the next stage of decarbonizing its energy matrix. Its ambitious initiative to develop offshore wind energy farms off its coasts represents an opportunity to diversify and strengthen energy security while leading efforts to mitigate climate change in its region. The possible effects of wind energy on the coasts must be studied before its development in the country, taking as reference previous studies in the world relating it to characteristics of the country’s coasts.

The specific biological effects must be studied, considering the area’s fish, marine mammals, and birds, which necessarily requires a prior study of the characterizing the fauna that inhabits, visits, or feeds in the area. Regarding these species, the investigation of effects such as the release of sediments, introduction of hard substrates, accumulation of construction and operation noises, and electromagnetic fields is crucial.

Furthermore, the areas chosen for energy generation due to their wind potential must be considered protected and sensitive areas and, in turn, balanced with possible conflicts of interest in the areas mentioned in

Table 4. The prohibition of fishing in the park or in surrounding exclusion zones is a point to discuss if these technologies are implemented on the coasts. Mitigation measures for the effects on fishing must be considered, such as the possibility of the static fishery or the passage of certain boats through the area. Concerning a possible conflict with tourism, areas should be considered as least noticeable as possible for their operation, coordinating construction in seasons with low tourism.

Regarding environmental impacts, more published works could be found related to their studies and mitigations, which highlights the need to delve deeper into the area of social effects and how these conflicts of interest can affect them.

Uruguay has the opportunity to demonstrate the possibility of advancing a low-carbon economy in a committed and equitable way for local populations and the present ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, F.M. and G.R.; writing—review and editing, F.M., G.R., A.E. W.F. and J.C.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Council of Andalucía (Junta de Andalucía. Consejería de Transformación Económica, Industria, Conocimiento y Universidades, Secretaría General de Universidades, Investigación y Tecnología) through project ProyExcel 00381.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support provided by the Thematic Network 723RT0150 ‘‘Red para la integración a gran escala de energías renovables en sistemas eléctricos (RIBIERSE-CYTED)’’ financed by the call for Thematic Networks of the CYTED (Ibero-American Program of Science and Technology for Development) for 2022.

References

- Instituto Geográfico Militar. Situación geográfica de Uruguay. Available online: https://igm.gub.uy/situacion-geografica/.

- Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas. Ubicación geográfica de Uruguay. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-economia-finanzas/institucional/uruguay/ubicacion-geografica.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Población preliminar: 3.444.263 habitantes. n.d. Available online: https://www.gub.uy/instituto-nacional-estadistica/comunicacion/noticias/poblacion-preliminar-3444263-habitantes.

- Ministerio de Industria, Energía y Minería; Proyecto Movés: Hacia la movilidad eficiente y sostenible en Uruguay. 2022. MIEMMA-MVOT-AUCI-PNUD-GEF. Uruguay.

- Ministerio de Industria, Energía y Minería de Uruguay. Hoja de Ruta del Hidrógeno Verde en Uruguay. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-industria-energia-mineria/sites/ministerio-industria-energia-mineria/files/documentos/noticias/Hoja%20de%20ruta%20H2%20Uruguay_final.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- ANCAP. Ronda H2U Offshore. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.ancap.com.uy/17065/5/ronda-h2u-offshore.html (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Fredershausen, S., Meyer-Larsen, N., Klumpp, M. Comprehensive Sustainability Evaluation Concept for Offshore Green Hydrogen from Wind Farms. 2024. In: Freitag, M., Kinra, A., Kotzab, H., Megow, N. (eds) Dynamics in Logistics. LDIC 2024. Lecture Notes in Logistics. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Motta, A., Díaz-González, F., Villa-Arrieta, M. Energy sustainability assessment of offshore wind-powered ammonia. 2023. Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 420. ISSN 0959-6526. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, H. Díaz, H., Guedes Soares, C. Review of the current status, technology and future trends of offshore wind farms. 2020. Ocean Engineering, Volume 209, 107381. ISSN 0029-8018. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guillamón, A., Das, K., Cutululis, N., Molina-Garcia, A. Offshore Wind Power Integration into Future Power Systems: Overview and Trends. 2019. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 7, 399. [CrossRef]

- Giebel, G., Hasager, C. An Overview of Offshore Wind Farm Design. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Global Wind Energy Council. Global offshore wind report 2023. 2023. Global Wind Energy Council. Available online: https://gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/GWEC-Global-Offshore-Wind-Report-2023.pdf.

- Manzano-Agugliaro, F., Sánchez-Calero, M., Alcayde, A., San-Antonio-Gómez, C., Perea-Moreno, A.-J., Salmeron-Manzano, E. Wind Turbines Offshore Foundations and Connections to Grid. 2020. Inventions, 5, 8. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S., Restrepo, C., Katsouris, G., Teixeira Pinto, R., Soleimanzadeh, M., Bosman, P., Bauer, P. A Multi-Objective Optimization Framework for Offshore Wind Farm Layouts and Electric Infrastructures. 2016. Energies, 9, 216. [CrossRef]

- Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC). Global Wind Report. 2024.

- Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC). Global Offshore Wind Report. 2024.

- IRENA. Renewable power generation costs in 2022. 2023. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi.

- Shaw, W. J., Berg, L. K., Debnath, M., Deskos, G., Draxl, C., Ghate, V. P., Hasager, C. B., Kotamarthi, R., Mirocha, J. D., Muradyan, P., Pringle, W. J., Turner, D. D., Wilczak, J. M. Scientific challenges to characterizing the wind resource in the marine atmospheric boundary layer. 2022. Wind Energy Science, 7, 2307–2334. [CrossRef]

- Veers, P., Dykes, K., Basu, S., Bianchini, A., Clifton, A., Green, P., Holttinen, H., Kitzing, L., Kosovic, B., Lundquist, J. K., Meyers, J., O’Malley, M., Shaw, W. J., Straw, B. Grand Challenges: wind energy research needs for a global energy transition. 2022. Wind Energy Science, 7, 2491–2496. [CrossRef]

- Glasson, J., Durning, B., Welch, K., Olorundami, T. The local socio-economic impacts of offshore wind farms. 2022. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, Volume 95, 106783. ISSN 0195-9255. [CrossRef]

- Galparsoro, I.; Menchaca, I.; Garmendia, J.M.; Borja, Á.; Maldonado, A.D.; Iglesias, G.; Bald, J. Reviewing the ecological impacts of offshore wind farms. 2022. npj Ocean Sustainability, 1, 1. [CrossRef]

- Kaldellis, J.K., Apostolou, D., Kapsali, M., Kondili, E. Environmental and social footprint of offshore wind energy. Comparison with onshore counterpart. 2016. Renewable Energy, Volume 92, 543–556. ISSN 0960-1481. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Ambiente. Informe del Estado del Ambiente 2024. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.ambiente.gub.uy/oan/documentos/INFORME-DEL-ESTADO-DEL-AMBIENTE-2024-1.21.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- ANCAP (2014). Uruguay margen continental. Zona Editorial.

- Uruguay. Dirección Nacional de Recursos Acuáticos. Boletín Estadístico Pesquero 2018. 2019. MGAP-DINARA: Montevideo, Uruguay, pp. 1–52. ISSN 0797-194X.

- Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC). The Power of Our Ocean. 2020. Global Wind Energy Council: Brussels, Belgium, pp. 1–24. Available online: https://gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/OREAC-The-Power-of-Our-Ocean-Dec-2020-2.pdf.

- Uruguay, Ministry of Environment. Guidelines for Environmental Impact Assessment of Wind Farms. 2015. Uruguay, Ministry of Environment: Montevideo, Uruguay, pp. 1–100. Available online: https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-ambiente/sites/ministerio-ambiente/files/documentos/publicaciones/GU-EIA-006-00_20150701_Guia_EIA_Parques_Eolicos_Version_Final-para_aprobacion.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Instituto Brasileño de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales Renováveis—Ibama. Direção de Licenças Ambientais—Dilic. Estudo de Impacto Ambiental e Relatório de Impacto Ambiental (EIA/Rima). Processo nº 02007.003499/2019-9.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).