1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI), once considered a distant dream, has now become a reality. This technology is seamlessly embedded in almost every field worldwide. The latest frontier of artificial intelligence applications is wearable artificial intelligence, which achieves the ultimate goal of the IT industry - miniaturization and enhanced intelligence. Wearable artificial intelligence or WAI (hereafter) is not only a technological trend, but also a lifestyle trend. It is a multifunctional tool that can meet a wide range of personal needs. Professionals from different industries such as healthcare, logistics, and manufacturing have found wearable artificial intelligence indispensable. Dedicated wearable devices have improved productivity and security, completely changing the way these industries handle tasks. Once a lightweight artificial intelligence device is magnetically attached to a user’s clothing, belt, or integrated into glasses or helmet, it becomes the user’s artificial intelligence personal assistant. These devices combine proprietary software and OpenAI’s GPT, allowing users to complete various operations, from answering complex questions to monitoring heart rate and blood pressure, all in an instant. If the user needs visual effects, the micro projector can directly project important information onto the customer’s outstretched palm. The courier industry is made up of couriers, goods, logistics chains, and many software systems. The application of WAI is significantly improving the efficiency of sending and receiving couriers, and also brings more convenience to the work of couriers. In the process of picking and leaving the warehouse, the AI glasses can automatically complete the scanning operation within the field of view. Wearable AI-assisted handling devices can help couriers handle bulky goods. The AI helmet is embedded with an intelligent detection module, which can not only detect the vital signs of the courier, but also integrate a collision detection system, self-sensing taillights, Bluetooth headsets, microphones, etc.

There are currently a wide variety of mature WAI products on the market, such as WHOOP X OpenAI, META Smart glass, Apple Vision Pro, Garmin Connect IQ, Wear-GPT, Petey-GPT, Humane Ai Pin, etc. For couriers, traditional wearable devices, such as smart bracelets, watches and glasses are not enough, because the main job of couriers is to drive or carry goods. Couriers often bend over and drive, which can easily lead to traffic accidents and muscle strains, so the WAI devices for couriers are more on the joints, waist of work clothes, glasses and helmets. Usually, the income of a courier is determined by the quantity of goods delivered, the number of items moved, or the length of driving time. Therefore, couriers always earn income through prolonged physical labor. Although many previous studies have made efforts to optimize the labor intensity of couriers, such as optimizing routing [

1,

2], traffic information sharing [

3,

4], and vehicle problem detection [

5,

6], there is few researches on how to protect the body of couriers through WAI. WAI can be fitted into couriers’ belts and hats to automatically detect when couriers are on the job in high-risk postures that can lead to repetitive strain injuries, such as stooping, hyperextending or twisting. When suspicious or dangerous behavior first occurs, the courier will receive real-time feedback through gentle vibrations; reminding them that they have assumed a high-risk posture and helping them adjust their behavior. The application of WAI can not only help improve the health of couriers by avoiding injuries, but also reduce the compensation costs and insurance expenses of express companies by reducing accidental injuries and accidents.

Although researches about couriers are plenty, most of them are about courier related information system [

7], courier’s traffic accident compensation [

8], courier service design [

9], financial benefits [

10], courier employment protection [

11] and courier work efficiency improvement design [

12,

13,

14]. Research on protecting couriers with WAI is still in the blank globally. While wearables can bring benefits such as workforce optimization and cost-cutting to couriers, there are barriers to adoption by couriers. First, the wearable device may affect the flexibility of movement. Second, in a hot work environment, couriers may be reluctant to wear these devices. In addition, some couriers may refuse to wear these devices due to privacy concerns. The best way to promote wearables is for them to be willing to make changes in their behavior, rather than being forced to wear them just at the direction of their supervisors.

Therefore, the motivation of the study is to investigate the factors that affect the acceptance of WAI by couriers to help express companies interact with employees through WAI to understand when, in what environment or where couriers are at risk, helping companies redesign workflows. Traditional research always provides suggestions for company development from the perspective of managers, while the objective of this study is to start from the perspective of couriers and discover factors that affect their acceptance of WAI through questionnaires, in order to better protect the mental and physical health of couriers. The traditional management model is that the company tells the courier what to do. Whereas by this research, it is supposed to help couriers use big data to tell the company what to do through WAI devices. The purpose of this study is to help couriers better accept WAI, reduce the risk of accidental injury, and thus reduce the high insurance costs that express companies spend on couriers every year.

2. Literature Review

With the continuous development of technology, smart wearable devices have become a common technology product in today’s society. These smart wearable devices include smart wristbands, smart watches, smart glasses, etc. They provide convenience and support for personal health management by integrating various sensors and health monitoring functions. More and more people choose to wear smart wearable devices to better manage their health. The main functions of smart wearable devices include health monitoring, exercise tracking, sleep monitoring, etc. The health monitoring function can monitor and record individual health data in real time, such as heart rate, blood pressure, blood oxygen, etc., through integrated sensors and data analysis technology. The exercise tracking function can track exercise related data such as step count and calorie expenditure, helping individuals to keep track of their exercise situation. The sleep monitoring function can monitor and analyze sleep quality by wearing smart wearable devices, providing suggestions for improving sleep quality.

The shortage of skilled couriers can lead to income losses caused by knowledge loss, decreased productivity, and equipment downtime. The operation of heavy equipment requires a combination of professional knowledge and skills, and requires a lot of time to learn. The WAI solution integrates a deep knowledge network that records key data used by senior couriers to make real-time decisions and enable new employees to quickly, effectively, and securely get started. Artificial intelligence is equipped with machine learning and deep learning algorithms, enabling transportation and wearable devices to make real-time decisions and autonomously execute tasks, which is particularly valuable in emergency situations that require rapid response. Predictive maintenance becomes possible through wearable devices that support intelligent real-time decision-making by couriers. Monitoring the performance of intelligent devices and vehicles can minimize the risk of unexpected failures. This improves device efficiency and eliminates the need for manual tracking and simplified operations. In summary, smart wearable devices have brought unprecedented convenience and benefits to personal health management, enabling real-time monitoring and recording of individual health data.

Many existing researches mainly focus on the acceptance of wearable devices by the elderly and the disabled;

Table 1 shows the details of those previous researches.

Although these previous studies help to increase the acceptance of wearable devices, unfortunately, they all ignore the importance of WAI devices to couriers. Compared with the general population, the professional population is less sensitive to the price of WAI devices, because the company will bear this cost in order to reduce injury compensation, improve labor efficiency and reduce insurance cost. More importantly, the functions of professional WAI devices are different from ordinary monitoring and detection devices. They are specially designed for the safety protection of specific types of work. Due to the lack of research on WAI devices by couriers, it is necessary to conduct research to discover what factors can affect the acceptance of wearable devices by couriers.

2.1. Affective Event Theory

Affective event theory is widely used in research on the acceptance of various techniques. Affective event theory is about how events change a person’s emotions to affect work behaviors over time. The theory has two core concepts. The first is an almost automatic emotional response resulting from affective-driven behavior. The second is about how cognition and attitudes can influence people’s judgmental behavior. Lam & Chen (2012) [

23] test hotel employee’s emotional labors based on affective event theory. Guenter et al. (2014) [

24] use affective event theory explore the information exchange delay’s negative impact among employee. Luo & Chea (2018) [

25] test factors that affect Web sites’ success and failure according to affective events theory. Sarker et al. (2019) [

26] apply affective event theory to explore factors related to affective reaction of transit systems. Mi et al. (2021a) [

27] introduce affective event theory to test factors affecting environmental citizenship behavior. Lee et al. (2021) [

28] apply affective event theory to find how tourists respond to service failure. Mi et al. (2021b) [

29] use affective event theory to test factors related to public environmental behavior. It is necessary to choose the appropriate theory to design a model of courier acceptance of WAI devices. Traditional research focuses on the impact of courier work environment characteristics on satisfaction, while affective event theory takes events that occur at work as the direct cause of emotional responses. Affective event theory does not ignore the role of work environment characteristics, but believes that these characteristics affect emotional experience more or less through work events. WAI devices are new and can be placed in a courier’s helmet, hat, clothing or shoes, which is likely to be uncomfortable for the courier. When couriers wear WAI devices, outsiders may also question these devices and may make positive or negative comments, which can affect the courier’s mood and thus affect the courier’s acceptance of WAI devices.

2.2. Push-Pull-Mooring Theory

Although affective event theory can well explain couriers’ emotional acceptance of wearable devices, it cannot explain which factors promote couriers’ acceptance of wearable devices, which hinder couriers’ acceptance of wearable devices, and which can moderate the acceptance behavior of the courier towards the wearable device. In the 60s of the 20th century, the American scholar E.S. Lee proposed a systematic theory of population migration-push-pull theory. For the first time, he divided the factors that affect migration and divided it into two aspects: pushing and pulling. In his view, pushing factors motivate migrants to leave their places of origin. Pulling factors attract migrants with a desire to improve their lives to move into new places of residence. Pushing, pulling and mooring theory was originally used to explain the influencing factors of migration from one geographic area to another. Pushing means factors that encourage people to abandon their current place, pulling refers to the attractiveness of a new choice, whereas mooring indicates factors that moderating pushing and pulling behaviors. As for couriers’ adoption to WAI devices, pushing means factors emotionally affects courier’s acceptance of WAI devices. Pulling indicates factors promoting and encouraging courier’s acceptance of WAI devices technically. Mooring means factors moderating those pushing and pulling factors. Lots of previous researches have applied pulling, pushing and mooring theory to test all kinds of acceptances in different research areas. Wang et al. (2020) [

30] apply push-pull-mooring theory to green transportation research. Tang & Chen (2020) [

31] explore factors related to un-following brand micro-blogs in a push-pull-mooring model. Al-Mashraie et al. (2020) [

32] apply push-pull-mooring theory to telecommunication industry research. Liu et al. (2021) [

33] explore users’ switching intention to paid social question-and-answer services. Zhang et al. (2021) [

34] use push-pull-mooring theory to understand users’ switching behavior to peer to peer accommodation. Frasquet & Miquel-Romero (2021) [

35] introduce push-pull-mooring theory to show-rooming research. Zeng et al. (2021) [

36] test factors related to adoption of land information system in a push-pull-mooring framework. Wang et al. (2021) [

37] use a push-pull-mooring view to test factors related to technology-dependent shopping behavior. Kim (2021) [

38] use qualitative method to find push-pull-mooring factors are useful in predicting users’ switch behavior in fitness. Ghufran et al. (2022) [

39] test factors affecting users’ adoption to organic food based on push-pull-mooring theory.

The advantage of the combination of the two theories is not only that they are considered to be inseparable from the behavior of couriers, but also that the two theories are widely applicable and can measure courier’s behavior from multiple perspectives. Although these two theories are often independently applied to research in various disciplines, this study believes that the application of WAI devices to couriers is a new way of improving productivity, and the application of this new scientific research requires the use of high-performance theory to measure.

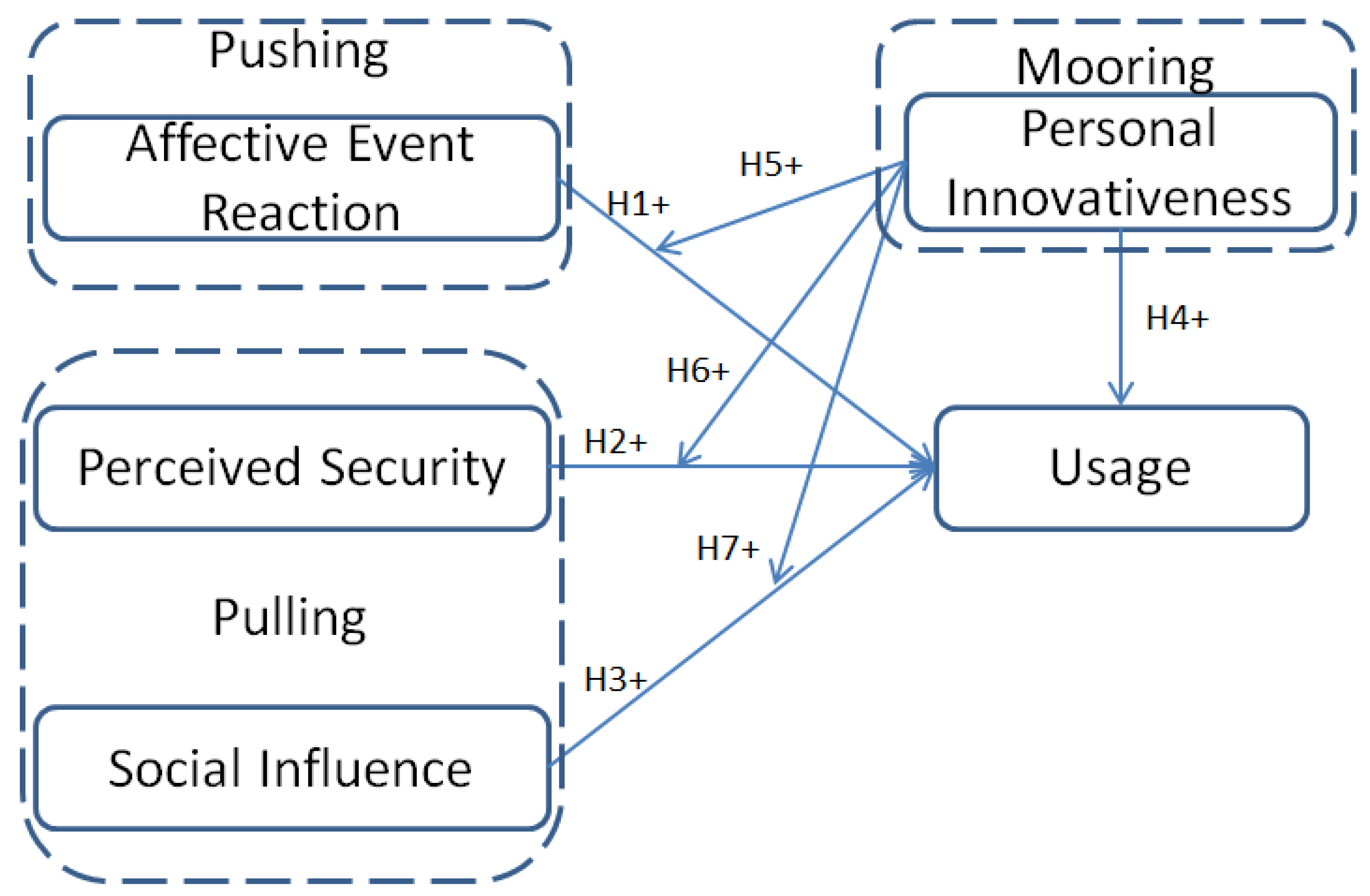

3. Hypothesis

Affective event theory indicates that an event that evaluates and responds to work-related events, goals, and events that stimulate short-lived or persistent stimuli is an affective event. Affective event reactions can be divided into two types: negative or positive affective events reactions. In the adoption progress to WAI devices, they may have relatively large emotional fluctuations and psychological imbalances. The excitement of couriers may be caused by positive emotional events, while emotions such as sadness, fear, and anger are usually caused by negative emotional events. Negative affective events could have a greater impact on individual emotions and a longer impact time than positive affective events, which may lead to counter work behavior or service failure [

23,

24,

28]. Most couriers are not highly educated, so learning how to use WAI devices properly can be difficult and time consuming. Because courier work is busy and tiring, most couriers may be opposed to unpaid WAI device training. In some cases, WAI devices are an additional burden for the courier, which may add weight to the garment or cause a certain degree of inconvenience to the daily work. Although WAI devices are helpful in protecting them from accidents, the invasion of personal privacy by wearable devices may also cause negative emotional responses from couriers. In conclusion, affective event reaction is a pushing factor that makes couriers have positive and negative emotional responses to wearable devices, and these responses push couriers to release their emotions and guide administrators to continuously improve the user experience. As long as the WAI device is designed to be convenient enough and the express company provides patient training to the courier, the couriers are likely to have a positive reaction towards accepting the WAI device. Quite a few researches have applied affective event reaction to different research models [

25,

26,

40]. According to the above discussion, the affective event reaction of the couriers may have a positively impact on the acceptance behavior, therefore:

H1: Affective event reaction positively affects couriers’ WAI devices usage.

Couriers often encounter dangerous situations due to long hours of driving, walking and carrying goods. WAI devices are specifically designed to inform couriers how to take precautions when faced with dangerous situations. WAI devices can automatically detect high-risk postures that lead to repetitive strain injury, unsafe driving behaviors, or physiological indicators including heart rate and blood pressure. When these data parameters are abnormal, first, couriers receive real-time feedback through gentle vibrations, alerting them to imminent danger. Also, the data is shipped to a cloud-based web dashboard that can be used by courier engineers and administrators to suggest improvements to high-frequency problems. When encountering difficulties, couriers can also communicate with Chat-GPT to receive timely advice. Because these measures are to ensure the safety of couriers, perceived security is a pulling factor which may pull couriers to use wearable devices. When the perceived security of couriers improves, they are more willing to accept WAI devices. Perceived security is a popular factor in different research fields, including health care (Colobran 2016), crime prevention [

41], aggressive behavior prevention [

42], city park construction [

43], transport policy [

44], mobile banking adoption [

45] and investment [

46]. Thus:

H2: Perceived security positively affects couriers’ WAI devices usage.

Nowadays, in the WAI device market, new AI products emerge in an endless stream, penetrating into every aspect of life. Among them, AI products that can be worn on the body have also appeared, such as sports bracelets, smart watches, Google project glassed and Microsoft’s Hololens, medical equipment, which not only bring fresh life experience, but also solve people’s actual needs and improve the quality of life. Relying on the development of Chat-GPT, WAI products have gradually entered people’s lives. WAI products are directly connected to the human body, which may test people’s personality, bone age, gender and taste. Since WAI devices are becoming emotional fashion items, social influence is also becoming a pulling factor which may pull couriers to adopt it. In the era of the Internet of Everything, it must be the trend of the future fashion industry. The huge social influence of WAI devices has also contributed to its acceptance by couriers. Social influence is a traditional factor in many research fields, including mobile banking payment [

47,

48], technology adoption [

49] and mobile shopping [

50]. Therefore:

H3: Social influence positively affects couriers’ WAI devices usage.

In the era of knowledge, personal innovativeness ability may change a person’s cultivation, thinking and destiny. Personal innovativeness ability is also one of the basic qualities of a modern outstanding talent. Personal innovativeness is often inseparable from a good professional foundation and experimental skills. Thus, having a good professional theory and knowledge level as the guarantee, and being good at learning and trying new things will better help couriers accept WAI devices. Usually, individuals with higher personal innovation are more receptive to new AI technologies such as Chat-GPT. Personal innovativeness is such a useful pulling factor that many previous researches have used personal innovativeness to test adoption behavior in various research fields, including mobile payment [

51], upscale restaurants development [

52], social commerce [

53] and artificial intelligence [

54]. Based on all the above discussion, it is concluded that:

H4: Personal innovativeness positively affects couriers’ WAI devices usage.

Shaw & Sergueeva (2018) [

55] apply personal innovativeness as a moderator to research of mobile commerce research. Sun et al. (2020) [

56] find personal innovativeness can effectively moderate the intention behavior in investment decision. Khazaer & Tareq (2021) [

57] use personal innovativeness as a moderator to test the intention to use of electric cars. All of these previous researches indicate that personal innovativeness may also moderate other relationships in this research, which making it a mooring factor that moderates pushing, pulling factors and usage. When couriers perceive more personal innovativeness, they will face affective event positively and optimistically, and may try a variety of ways to solve difficulties. Innovative couriers may actively cooperate with the company for their own job safety, and become proficient in using WAI devices while ensuring their own safety. Similarly, couriers with more innovativeness may be more receptive to external positive encouragement and influence, which contributes to the acceptance of WAI devices. Based on the above, it is concluded that:

H5: Personal innovativeness positively moderates the relationship between affective event reaction and couriers’ WAI devices usage.

H6: Personal innovativeness positively moderates the relationship between perceived security and couriers’ wearable WAI usage.

H7: Personal innovativeness positively moderates the relationship between social influence and couriers’ wearable WAI usage.

The affective event theory plays a key role in the research model by using the affective event reaction factor. Perceived security and social influence are workplace environment factors. Personal innovativeness is regarded as a kind of attitude factor. Behavior is a kind of usage factor. Push-pull-mooring theory gives a structure of this research, whereas affective event theory defines the factors of the research model.

4. Methods

4.1. Research Design and Data Collection

This survey is a marketing exercise that addresses couriers’ wearing preferences, so there is no medical information in this study. A compliant questionnaire must comply with legal procedures and ethical constraints. In all procedures of this research, relevant guidelines and regulations were well enforced. Anyang Institute of Technology ethics committee has approved all questionnaire protocols, including those involving various ethical conduct and any relevant details. Informed consent was obtained from all participating couriers.

We conducted a pre-test survey of 51 courier volunteers to improve the reliability and validity of the survey. Based on the results of the pre-test, we made minor adjustments to the content of the questionnaire in preparation for large-scale questionnaire distribution. Then, with the help of ZTO Express Company, the questionnaires were distributed in 4 capital cities (Zhengzhou, Wuhan, Hefei and Jinan) in different provinces of China. Because couriers participated anonymously, the researchers did not have access to any personal information about the participants. The questionnaire is filled out online, and the courier enters the questionnaire filling system by scanning the QR code. Each fully filled courier received a movie coupon. The questionnaire survey starts on May 8, 2023 and ends on May 22, 2023. A total of 316 questionnaires were received, out of which incomplete questionnaires and invalid questionnaires were issued, 263 valid questionnaires remained.

4.2. Measurement

The effect and extent of social influence are conditioned by the communicator. The communicator’s trustworthiness, charisma, communication skills, and status in the courier’s mind will affect how well the courier interprets. The subjective state of the courier, such as intelligence level and personality characteristics, also has a certain impact on the degree of acceptance. According to this idea, three items are used to measure social influence according to Grob (2018) [

50]. Perceived security is the process of courier cognition and judgment of safety or unsafe factors in the use of WAI. It involves the judgment and assessment of the degree of danger, safety status and potential risks of the environment in which the courier is located in the use of WAI. Perceived security is a subjective feeling of the courier and is influenced by individual differences, experience, and knowledge. Based on this idea, Three items are used to measure perceived security according to Sun et al. (2021) [

58]. Rational use of WAI may bring couriers more autonomy in their work, opportunities for promotion, and high income, among other things. Couriers can experience both hassles and negative incidents by using the use of WAI as well as uplifting events. Therefore,three items are used to measure affective event reaction according to Luo & Chea (2018) [

25]. In the process of using WAI, couriers find and try new skills through observation, experience, association, thinking, and so on to improve their acceptance of WAI. The application of WAI is a new challenge for couriers, and those who are willing to try new things may have an easier time mastering the skills of using WAI. Thus, three items are used to measure personal innovativeness according to Gansser et al. (2021) [

54]. Three items are used to measure usage according to Wu et al. (2022) [

59]. All the items are scored by 7-Likert.

Smart-PLS is statistical analysis software for partial least squares structural equation modeling, which is flexible and easy to use [

60]. It is generally used in management, organizational behavior, and information systems. It has the following advantages: it helps users to create a good path model; it is easy to create adjustment variables; it can quickly generate path coefficients based on data, and it generates system data reports completely and accurately; it performs better when the sample size is small or the data does not follow a multivariate normal distribution, as it has looser requirements for data and is more robust [

61]. Therefore, Smart-PLS is used as the main tool to test research data. Demographic statistics table is in

Table 1.

Table 2 indicates that most couriers are male and only 24.8% are female. Most of them have high school or bachelor degree and only few have master degree. Most of couriers are young and their yearly incomes are mainly lower than twenty thousand dollars. All of them have the experience of using WAI devices.

5. Results

In structural equation model testing, the reliability and validity of the model should be tested first. Cronbach’s alpha is a statistic for testing reliability, which refers to the average of the half-half reliability coefficients obtained by all possible item division methods of the scale, and is the most commonly used reliability measurement method. Composite Reliability refers to the consistency of the internal variables of the facet. Generally, both Cronbach’s alpha value and composite reliability value should be greater than 0.7 [

62,

63]. Average variance extracted (AVE) is used to test discriminant validity. Usually, the AVE value should be greater than 0.5 [

62]. In

Table 3, both of their values are higher than 0.7, therefore the model’s reliability is supported. Also, all the AVE values are higher than 0.5. The Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) is the ratio between and within traits used to test the discriminant validity of research models [

64].

Table 4 and

Table 5 present the progress of discriminant validity testing. All values in

Table 3 are less than the threshold of 0.85, while all values in

Table 4 are less than the threshold of 1.0. Therefore, the discriminant validity of the model is supported. After the validity and reliability of the research model are supported, related empirical test results are shown in

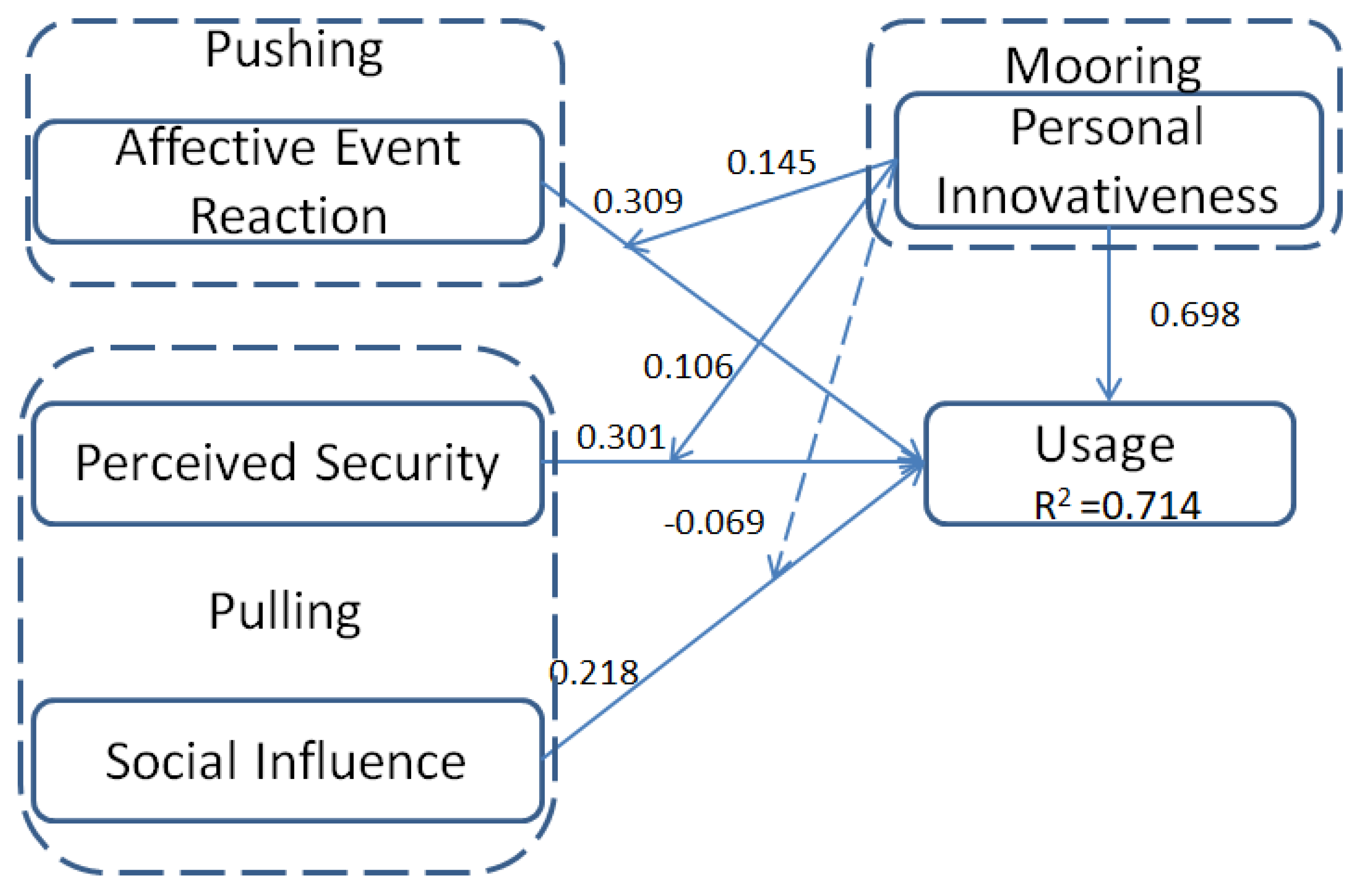

Figure 2. It gives that H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6 are all supported with P value less than 0.05. Unfortunately, H7 is not supported with P value greater than 0.05 [

65]. The path coefficient between personal innovativeness and usage is 0.698, which is the highest path coefficient of all. Affective event reaction positively affects usage with path coefficient 0.309. The path coefficient between perceived security and usage is 0.301. Social influence positively affects usage with path coefficient 0.218. Personal innovativeness positively moderates the relationship between affective event reaction and usage with path coefficient 0.145. Personal innovativeness positively moderates the relationship between perceived security and usage with path coefficient 0.106. Personal innovativeness doesn’t moderate the relationship between social influence and usage. All the structural results are indicated in

Figure 2. When couriers’ personal innovativeness is high, both affective event reaction and perceived security associated with higher level of usage, whereas social influence makes no difference. R-squared is the coefficient of determination. It reflects the proportion of the total variance of the dependent variable that can be explained by the independent variable through the regression relationship. The R-squared value in this model is 0.714, which means that the regression relationship can explain 71.4% of the variance of the dependent variable.

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The PPM theory comes from demography, while the AET theory comes from psychology. This study innovatively designed a research model using the two theories. The model results show that two theories can effectively explain the level of acceptance of WAI devices by couriers. The courier chooses a certain WAI device service because of inherent needs, which is a profit driven performance. When the WAI device service cannot satisfy the courier in certain aspects, the courier may inevitably abandon it and look for alternatives. The research results show that most WAI services can meet the main needs of couriers, including emotional event reaction, innovation needs, security needs, and social influence. This fully demonstrates that when a single theory is difficult to measure people’s acceptance of the latest technology, the combination of the two theories can not only compensate for this deficiency, but may also enhance the reliability and validity of the research model. The results of this study provide a new attempt for future interdisciplinary research, which combines various theories from different disciplines to explain the latest social phenomena, products, and technologies.

Traditional theoretical integration generally adds some new research variables to the original model to better explain the behavior of the research object, but rarely classifies the research variables. In this research, we first combined personal innovativeness, perceived security and social influence with AET theory as the basic research model, and then classified each variable according to the PPM theory. In other words, the AET theory is the basis for variable selection, while the PPM theory is the basis for model structure shaping. This kind of theoretical integration thought breaks through the tradition and makes a new successful attempt. This idea may encourage more exploration and innovation in the classification of variables in future research.

6.2. Practical Implications

Affective event reaction, as pushing factor, positively affects usage, which means both couriers’ positive and negative affective reactions should be carefully considered by couriers companies. Express delivery companies and WAI device manufacturers must collect couriers’ affective reactions and try to give proper response. When couriers give positive affective reaction, express delivery companies may encourage them and reward them. If couriers give negative affective reaction, express delivery companies and WAI device manufacturers should find a solution to the problem and implement it as soon as possible to avoid accidental injury to couriers. Express delivery companies could develop rehabilitation plans for different couriers based on feedback from WAI devices, such as waist training, shoulder massage, knee treatment, and psychological counseling. All these effort may bring better affective reactions from couriers, thereby, increase couriers’ acceptance of WAI devices. Although these behaviors seem to increase the cost of express delivery companies, but compared with high insurance investment and accident compensation, it is fairly reasonable and affordable.

Perceive security, as pulling factor, affects usage positively, which suggests that companies should focus more on the functionality of WAI devices that improve courier safety, rather than using WAI devices to monitor courier productivity. The express company should not only buy personal accident insurance for couriers, but also should negotiate with the insurance company to design insurance specifically for some specific high-frequency accidental injuries of courier based on feedback data from WAI devices. The feedback WAI data can help express delivery companies develop accurate insurance purchase plans and require insurance companies to customize insurance for different types of couriers. These measures that can improve the perceived safety of couriers may pull up their enthusiasm for work.

Since social influence, as pulling factor, has a positive impact on usage, express delivery companies could increase the promotion of the advanced nature of WAI devices, and combine social media to promote WAI devices among couriers as a fashionable, avant-garde and practical technology. While WAI devices may add weight or thickness to overalls, express delivery companies and WAI device manufacturers need to popularize the idea among couriers that WAI devices are used to protect couriers rather than supervise their work. Express delivery companies should reward grassroots employees who adopt a welcoming attitude towards WAI devices, as their behavior can influence more people around them. The managers or executives may wear WAI devices to work with ordinary employees, or invite celebrities to wear the same WAI devices as models for publicity.

Personal innovativeness, as mooring factor, not only has a positive effect on usage, but also has positive moderating effect on relationships between affective event, perceived security and usage. This indicates that increasing personal innovativeness can encourage couriers’ adoption to WAI devices greatly. According to AET theory, the use of WAI may bring both hassles and uplifts to couriers. For moderating effect between affective event reaction and usage, companies can strengthen rewards for couriers using WAI devices, such as shortening work hours or providing more holidays, in order to create a relaxed and innovative work atmosphere for couriers. With the help of WAI devices, managers can reduce traditional supervision of courier work, increase their enthusiasm and bring more uplifts on adoption of WAI. Considering moderating effect between perceived security and usage, managers can not only develop management systems and insurance premiums based on real-time feedback from WAI devices, but also discover high-quality couriers who use WAI and encourage them to share their experience, thereby improving couriers’ perceived security on adoption of WAI. Furthermore, couriers could determine their vacation, work intensity, physical examination items, and career planning based on feedback data from WAI, thereby increasing their acceptance of WAI. Last but not least, companies should give couriers sufficient autonomy to use WAI devices. While some innovative couriers may try new tricks on how to use the equipment, these beneficial attempts should be encouraged rather than punished, even if the performance of these devices may be challenging.

WAI is not only composed of AI glasses, helmets, watches, clothing, and external skeletons, but also a huge information management system as the management center. Therefore, the company should invest more manpower and financial resources to optimize the WAI management system, and design a humanized system by collecting the daily data of couriers, so as to reduce insurance costs while protecting the health of couriers and improving their work enjoyment. Although the purchase of WAI equipment and management system developing can greatly reduce insurance costs in the long run, the large short-term investment may lead to resistance from the company’s management. However, the reality is that with the rising labor and insurance costs, the application of AI equipment may be a key factor in the competition of express companies in the future.

When challenges and opportunities coexist, the large express companies can join forces to develop WAI industry standards and negotiate with insurance companies to obtain larger concessions. WAI industry standards should be able to enhance the personal innovativeness of the couriers, bring them a positive emotional experience, and give WAI a good reputation among the couriers.

7. Discussion

Traditional researches on express delivery services mainly includes the quality of express delivery services [

66], user satisfaction [

67], adoption of delivery apps [

68], improvement of express delivery technology [

69], service comparison [

70] and after service quality [

71]. With the continuous development of logistics and the popularization of online shopping, couriers send and receive a large number of parcels every day, running at the front line. The heavy workload and direct contact with a large number of goods make the safety research of couriers a very important new topic. Benefiting from years of technological accumulation in various fields such as the Internet of Things, cloud computing, big data, block-chain, and artificial intelligence, many express delivery companies are using wearable technology to protect their couriers, increase technological innovation and application pace, improve logistics timeliness, and reward couriers who deliver goods safely and efficiently for a long time. The currently popular wearable artificial intelligence terminals consist of smart watches, smart glasses, smart helmets, smart jackets, scanners, and Bluetooth earphones. Compared with traditional protection measures, WAI devices have the characteristics of high efficiency, small size, and portability. WAI devices not only have protective functions, but can also perform operations such as contacting customers, modifying information, and signing for customers through voice communication. The WAI device is also embedded with a logistics map, making path planning clear at a glance and visualizing the entire process of receiving and dispatching. The monitoring function of WAI can also serve as evidence to reward couriers who have made significant contributions in service quality, social responsibility, innovation, and development. WAI devices are also playing an increasingly important role in enhancing the job competitiveness of female and elderly couriers, as they can greatly reduce labor intensity, enable female and elderly employees to handle long-term sustainable heavy cargo transportation work, and reduce the occurrence of intentional injuries.

An increasing number of express delivery companies have found that data collected from WAI devices can predict diseases and accidents, and the use of wearable devices by couriers to improve their health beyond exercise will become a new trend. Express delivery companies can save a significant amount of insurance investment in a positive cycle between equipment, health promotion, rewards, and premium discounts, with WAI devices. The application of WAI devices is a win-win strategy for express delivery companies and insurance companies. As an indispensable link in the health management chain, insurance is making innovative predictions and guidance on the life behavior of the insured with the help of artificial intelligence, WAI devices and other technologies, taking prevention as the principle, reducing the incidence rate, and reducing the risk level of both the insured and the insurance company at the same time. The application of wearable devices, the addition of data and health management, and the two-way demand of insurance and express companies are an undeniable force in the future big health industry. From a longer-term perspective, the insurance industry in the future cannot only remain in the function of risk transfer. Only by endowing users with more value and significance can it go further, and only by more effectively helping its customers achieve healthier lives can it maintain sustained competitiveness.

8. Conclusions

Insurance costs are a significant part of the annual financial budget of express delivery companies. Every year, there are also some couriers who get injured or encounter traffic accidents during work. The emergence of WAI devices is aimed at reducing company insurance costs and the frequency of accidents for couriers. Express delivery companies can regularly train couriers on the use of WAI equipment to help them better understand how to avoid risks on the job. WAI devices not only support efficient information communication, map navigation, and artificial intelligence chat to help couriers improve work efficiency, but also can detect heart rate status, analyze labor intensity, identify incorrect handling postures, and provide risk behavior reminders in real-time. Through the analysis and pattern recognition of health and exercise data, WAI devices can provide more accurate and personalized work advice and labor intensity analysis, greatly reducing the insurance costs of express companies. In order to better promote WAI devices, it is recommended that the government provide tax exemptions or subsidies for companies that purchase WAI devices for couriers. The customization capability of WAI devices will become even more important. Designers should help couriers set up the features they need and filter and disable unnecessary features to save power and enhance their own safety. The personal privacy of couriers should also be respected and protected. Wearable devices should not monitor and record information that couriers believe should not be made public, such as personal phone numbers, resting behavior, religious behavior, and any information that assesses personal intelligence. Designers can also design more ergonomic garments and accessories that integrate smart sensors that are convenient for couriers to work with and monitor their biometrics and surroundings in real time. Designers can optimize the user interface and user experience to ensure that couriers can easily interact with WAI devices, receive timely alerts and health reminders, and reduce the additional risk of manipulation complexity.

9. Limitations and Future Research

While the questions discussed in this study attempt to cover all aspects of courier acceptance of WAI devices, there are still some limitations. First, the object of this study is limited to Chinese couriers, thus ignoring the preference of foreign couriers for WAI devices. Therefore, future research should be conducted with couriers in more countries around the world. Second, this study focuses on couriers at the grassroots level, ignoring the opinions of senior executives of express delivery companies. Since senior managers have the authority to purchase and manage WAI devices, future research should be conducted on them. Additionally, the insurance company’s database contains millions of courier compensation data, which can help designers create WAI devices that are more suitable for manual workers. Future research can conduct big data mining on various data of insurance companies to discover the most useful data for designers to develop better WAI devices for couriers. Furthermore, this research limits to the data of the express delivery industry, which does not fully reflect the application of WAI equipment to all companies, so future research can formulate effective rules for the exchange of data for different types of industries, so as to better promote the adoption of WAI equipment to other industries such as sports, medical and transportation industries. Finally, this study ignores the research on the universality of the operating system of WAI devices. In fact, the wide variety of WAI devices on the market should eventually move towards a consistent hardware and software design like AI phones, so as to facilitate users to choose the right WAI device according to their own needs, so future research can be dedicated to the development of an open operating system for WAI devices.

References

- Asghari, M., Deng, D., Shahabi, C., Demiryurek, U., & Li, Y. (2016). Price-aware Realtime Ride-sharing at Scale: An Auction-based Approach. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems. SIGSPACIAL ’16.

- Al-Kanj, L., Nascimento, J., & Powell, W. B. (2020). Approximate Dynamic Programming for Planning a Ride-Sharing System using Autonomous Fleets of Electric Vehicles. European Journal of Operational Research. ArXiv: 1810.08124.

- Ota, M., Vo, H., Silva, C., & Freire, J. (2015). A scalable approach for data-driven taxi ride-sharing simulation. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data) pp. 888–897.

- Jia, Y., Xu, W., & Liu, X. (2017). An Optimization Framework for Online Ride-Sharing Markets. In 2017 IEEE 37th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS) pp. 826–835.

- Masoud, N., & Jayakrishnan, R. (Dec. 2017). A real-time algorithm to solve the peer-topeer ride-matching problem in a flexible ridesharing system. Transportation Research. Part B: Methodological, 106, 218–236.

- Chen, Y., Qian, Y., Yao, Y., Wu, Z., Li, R., Zhou, Y., … Xu, Y. (2019). Can sophisticated dispatching strategy acquired by reinforcement learning?:. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and MultiAgent Systems (pp.1395–1403). Springer.

- Zhang, L., & Thompson, R. G. (2019). Understanding the benefits and limitations of occupancy information systems for couriers. Transportation research, 105(AUG.), 520-535. [CrossRef]

- Shin, G., Jarrahi, M. H., Fei, Y., Karami, A., Gafinowitz, N., & Byun, A., et al. (2019). Wearable activity trackers, accuracy, adoption, acceptance and health impact: a systematic literature review. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 93. [CrossRef]

- Lin, B., Zhao, Y., & Lin, R. (2020) Optimization for courier delivery service network design based on frequency delay. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 139(Jan.), 106144.1-106144.19. [CrossRef]

- Mcleod, F. N., Cherrett, T. J., Bektas, T., Allen, J., & Wise, S. (2020). Quantifying environmental and financial benefits of using porters and cycle couriers for last-mile parcel delivery. Transportation Research Part D Transport and Environment, 82, 102311. [CrossRef]

- Rolf, S., O’Reilly, J., & Meryon, M. (2022). Towards privatized social and employment protections in the platform economy? evidence from the uk courier sector. Research Policy, 51.

- Oliveira, L., Oliveira, I., Nascimento, C., Cordeiro, C., & Silva, F. (2021). Identification of factors to improve the productivity and working conditions of motorcycle couriers in belo horizonte, brazil. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Santos, A., Viana, A., Pedroso, J. (2022) 2-echelon lastmile delivery with lockers and occasional couriers. Transportation Research Part E 162, 102714. [CrossRef]

- Bozanta, A., Cevik, M., Kavaklioglu, C., Kavuk, E. M., Tosun, A., & Sonuc, S. B., et al. (2022). Courier routing and assignment for food delivery service using reinforcement learning. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 164, 107871. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Wu, J., Gao, Y., & Shi, Y. (2016). Examining individuals’ adoption of healthcare wearable devices: an empirical study from privacy calculus perspective. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 88, 8-17. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Luo, M., Nie, R., & Zhang, Y. (2017). Technical attributes, health attribute, consumer attributes and their roles in adoption intention of healthcare wearable technology. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 108(dec.), 97-109. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., & Park, E. (2019). Beyond coolness: predicting the technology adoption of interactive wearable devices. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 49(JUL.), 114-119. [CrossRef]

- Farivar, S., Abouzahra, M., & Ghasemaghaei, M. (2020). Wearable device adoption among older adults: a mixed-methods study. International Journal of Information Management, 55. [CrossRef]

- Ogbanufe, O., & Gerhart, N. (2022). Exploring smart wearables through the lens of reactance theory: linking values, social influence, and status quo. Computers in Human Behavior, 127, 107044. [CrossRef]

- Huarng, K. H., Yu, H. K., & Lee, C. F. (2022). Adoption model of healthcare wearable devices. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Xie, W., Ali, A., Brem, A., & Wang, S. (2022) How do individual characteristics and social capital shape users’ continuance intentions of smart wearable products? Technology in Society, 68. [CrossRef]

- Hayat, N., Salameh, A., Malik, H., & Yaacob, M. (2022) Exploring the adoption of wearable healthcare devices among the Pakistani adults with dual analysis techniques. Technology in Society 70, 102015. [CrossRef]

- Lam, W., & Chen, Z. (2012). When I put on my service mask: determinants and outcomes of emotional labor among hotel service providers according to affective event theory. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31( 1), 3-11. [CrossRef]

- Guenter, H., Emmerik, I., & Schreurs, B. (2014). The negative effects of delays in information exchange: looking at workplace relationships from an affective events perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 24(4), 283-298. [CrossRef]

- Luo, M. M., & Chea, S. (2018). Cognitive appraisal of incident handling, affects, and post-adoption behaviors: a test of affective events theory. International Journal of Information Management, 40(JUN.), 120-131. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, R. I., Kaplan, S., Mailer, M., & Timmermans, H. (2019). Applying affective event theory to explain transit users’ reactions to service disruptions. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 130, 593-605. [CrossRef]

- Mi, L., Zhao, J., Xu, T., Yang, H., & Zhang, Z. (2021a). How does covid-19 emergency cognition influence public pro-environmental behavioral intentions? an affective event perspective. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 168, 105467. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B., An, S., & Suh, J. (2021). How do tourists with disabilities respond to service failure? an application of affective events theory. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38(3), 100806. [CrossRef]

- Mi, L., Sun, Y., Gan, X., Yang, Y. A., Jia, T., & Wang, B. (2021b). Predicting environmental citizenship behavior in the workplace: a new perspective of environmental affective event. Sustainable Production and Consumption. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Wang, J., & Yang, F. (2020). From willingness to action: do push-pull-mooring factors matter for shifting to green transportation?. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 79, 102242. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z., & Chen, L. (2020) An empirical study of brand microblog users’ unfollowing motivations: the perspective of push-pull-mooring model. International Journal of Information Management, 52. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mashraie, M., Chung, S., & Jeon, H. (2020) Customer switching behavior analysis in the telecommunication industry via push-pull-mooring framework: a machine learning approach. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 144. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., et al. (2021) Exploring askers’ switching from free to paid social q&a services: a perspective on the push-pull-mooring framework. Information Processing & Management, 58(1). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Oh, H. K., & Lee, C. H. (2021). Understanding consumer switching intention of peer-to-peer accommodation: A push-pull-mooring framework. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 49, 321–330. [CrossRef]

- Frasquet, M., & Miquel-Romero, M. J. (2021). Competitive (versus loyal) showrooming: an application of the push-pull-mooring framework. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 62(3), 102639. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z., Li, S., Lian, J. W., Li, J., & Li, Y. (2021). Switching behavior in the adoption of a land information system in china: a perspective of the push–pull–mooring framework. Land Use Policy, 109(2), 105629. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Wong, Y. D., Liu, F., & Yuen, K. F. (2021). A push–pull–mooring view on technology-dependent shopping under social distancing: when technology needs meet health concerns. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. (2021). Conceptualization and Examination of the Push-Pull-Mooring Framework in Predicting Fitness Consumer Switching Behavior. Journal of Global Sport Management. [CrossRef]

- Ghufran, M., et al. (2022) Impact of COVID-19 to customers switching intention in the food segments: The push, pull and mooring effects in consumer migration towards organic food. Food Quality and Preference 99, 104561. [CrossRef]

- Shapoval, V. (2019). Organizational injustice and emotional labor in the hospitality industry: a theoretical review. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 83, 56-64. [CrossRef]

- Paydar, M., Kamani-Fard, A., & Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R. (2017). Perceived security of women in relation to their path choice toward sustainable neighborhood in santiago, chile. Cities, 60(PT.A), 289-300. [CrossRef]

- Guedes, M,. et al. (2018) Perceived attachment security to parents and peer victimization:Does adolescent’s aggressive behavior make a difference? Journal of Adolescence 65,196–206. [CrossRef]

- Mahrous, A., Moustafa, M., & EL-Ela, M. (2018). Physical characteristics and perceived security in urban parks: investigation in the egyptian context - sciencedirect. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 9( 4), 3055-3066. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Phuoc, D. et al. (2021). Investigating the complexity of perceived service quality and perceived safety and security in building loyalty among bus passengers in Vietnam – a pls-sem approach. Transport Policy, 101, 162-173. [CrossRef]

- Hanif, Y., & Lallie, H. S. (2021). Security factors on the intention to use mobile banking applications in the UK older generation (55+). a mixed-method study using modified UTAUT and MTAM - with perceived cyber security, risk, and trust. Technology in Society, 67. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. R., & Dhakal, S. (2022) Do experts and stakeholders perceive energy security issues differently in Bangladesh?. Energy Strategy Reviews 42, 100887. [CrossRef]

- Morosan, C., & Defranco, A. (2016). It’s about time: revisiting utaut2 to examine consumers’ intentions to use NFC mobile payments in hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, 17-29. [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A. A., Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., & Algharabat, R. (2017). Examining factors influencing Jordanian customers’ intentions and adoption of internet banking: extending utaut2 with risk. Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services, 40, 125-138. 10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.08.026.

- Macedo, I. M. (2017). Predicting the acceptance and use of information and communication technology by older adults: an empirical examination of the revised utaut2. Computers in Human Behavior, 75(oct.), 935-948. [CrossRef]

- Grob, M. (2018). Heterogeneity in consumers’ mobile shopping acceptance: a finite mixture partial least squares modeling approach for exploring and characterizing different shopper segments. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 40(JAN.), 8-18. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T., Thomas, M., Baptista, G., & Campos, F. (2016). Mobile payment: understanding the determinants of customer adoption and intention to recommend the technology. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 404-414. [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R., Assaker, G., O’Connor, P., & Lee, C. (2018). Firm performance in the upscale restaurant sector: the effects of resilience, creative self-efficacy, innovation and industry experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 40(JAN.), 229-240. [CrossRef]

- Doha, A., Elnahla, N., & Mcshane, L. (2019). Social commerce as social networking. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 47, 307-321. [CrossRef]

- Gansser, O. A., & Reich, C. S. (2021). A new acceptance model for artificial intelligence with extensions to utaut2: an empirical study in three segments of application. Technology in Society, 65. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, N., & Sergueeva, K. (2018). The non-monetary benefits of mobile commerce: extending utaut2 with perceived value. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 44-55. [CrossRef]

- Sun W, Dedahanov AT, Shin HY, Kim KS. (2020) Switching intention to crypto-currency market: Factors predisposing some individuals to risky investment. PLoS ONE 15(6): e0234155. [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, H., & Tareq, M. A. (2021). Moderating effects of personal innovativeness and driving experience on factors influencing adoption of BVES in malaysia: an integrated sem–bsem approach. Heliyon, 7(9), e08072. [CrossRef]

- Sun W, Dedahanov AT, Shin HY, Li WP. (2021) Using extended complexity theory to test SMEs’ adoption of Blockchain-based loan system. PLoS ONE 16(2): e0245964. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B., An, X., Wang, C., & Shin, H. Y. (2022) Extending UTAUT with national identity and fairness to understand user adoption of DCEP in China. Scientific Reports. [CrossRef]

- Sun W, Dedahanov AT, Shin HY, Kim KS. (2019) Extending UTAUT Theory to Compare South Korean and Chinese Institutional Investors’ Investment Decision Behavior in Cambodia: A Risk and Asset Model. Symmetry, 11, 1524. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing, in Advances in International Marketing, R. R. Sinkovics and P. N. Ghauri (eds.), Emerald: Bingley, pp. 277-320. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. R., Black, W. C., Babinand, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th Edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Zhou R & Tong L. (2022) A Study on the Influencing Factors of Consumers’ Purchase Intention During Live streaming e-Commerce: The Mediating Effect of Emotion. Front. Psychol. 13:903023. [CrossRef]

- Henseler J., Ringle C, M., Sarstedt M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. (2015) 43:115–135. [CrossRef]

- Sun W, Dedahanov AT, Fayzullaev AKU and Abdurazzakov OS. (2022) Abusive supervision and employee voice: The roles of positive reappraisal and employee cynicism. Front. Psychol. 13:927948. [CrossRef]

- Melian-Gonzalez S. (2022). Gig economy delivery services versus professional service companies: Consumers’ perceptions of food-delivery services. Technology in Society, 69, 101969. [CrossRef]

- Zenelabden, N., & Dikgang, J. (2022). Satisfaction with water services delivery in South Africa: the effects of social comparison. World Development, 156, 105861. [CrossRef]

- Sun W, Shin HY, Wu HY, Chang X. (2023) Extending UTAUT2 with knowledge to test Chinese consumers’ adoption of imported spirits flash delivery applications. Heliyon, 9, e16346. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J., Kim, J, J., & Lee, KW. (2021). Investigating consumer innovativeness in the context of drone food delivery services: Its impact on attitude and behavioral intentions. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 163, 120433. [CrossRef]

- Vakulenko, Y., Arsenovic, J., Hellstrom, D., & Shams, P. (2022). Does delivery service differentiation matter? Comparing rural to urban e-consumer satisfaction and retention. Journal of Business Research, 142, 476–484. [CrossRef]

- Javed, MK., & Wu, M. (2020). Effects of online retailer after delivery services on repurchase intention: An empirical analysis of customers’ past experience and future confidence with the retailer. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 54, 101942. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).