Submitted:

03 September 2024

Posted:

04 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Review Objectives

2. Background

2.1. Wearable Devices

2.2. Digital Biomarkers

3. Methods

3.1. Research Questions

- RQ-1 What type of wearables is commonly used to capture DB-MS-PD?

- RQ-2 Are there specific digital biomarkers that are commonly measured or tracked using wearables in PD?

- RQ-3 How reliable and accurate are the digital biomarkers captured by these wearables?

- RQ-4 What are the main challenges or limitations associated with using wearables for capturing DB-MS-PD?

3.2. Search Strategy

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Papers without peer review, books, book chapters, or published as “letter”, “comments”, "perspective" “case reports”, "surveys" or "reviews".

- Literature not written in English.

- Studies related to diseases other than PD.

- Studies that did not use any wearable devices or portable sensors for data acquisition.

- Studies showing the results of a challenge, competition or programme.

- Studies primarily focused on activities not related to motor symptoms in PD.

- Studies that do not include humans.

3.4. Data Extraction

- Identification of study data, including authors, title and citation.

- Type of test performed.

- Characteristics of the participants in the study.

- Type, number, and location of the wearable sensors and devices used for data acquisition.

- Objective of the study.

- End points.

4. Results

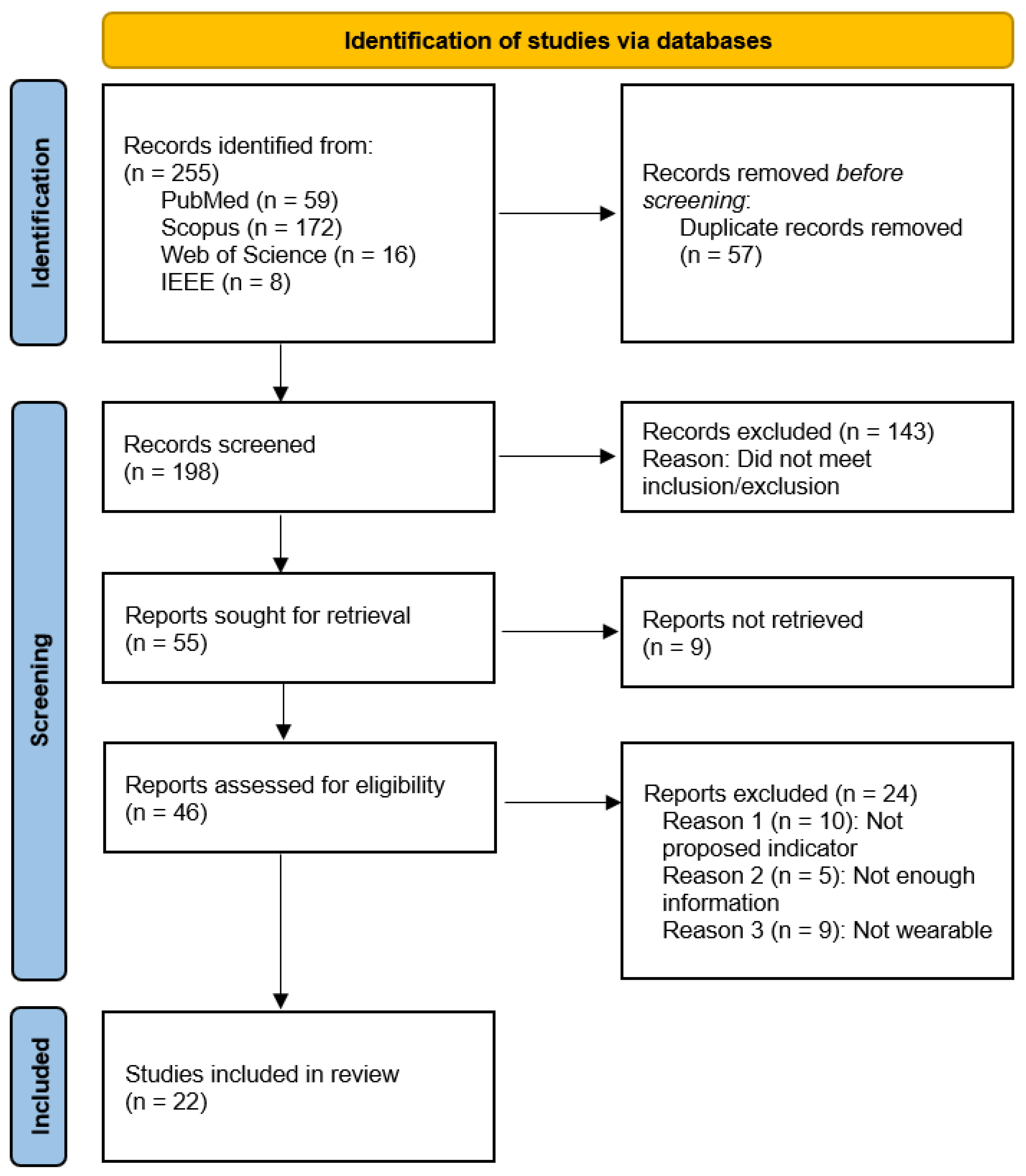

4.1. Systematic Review

4.2. Study Characteristics

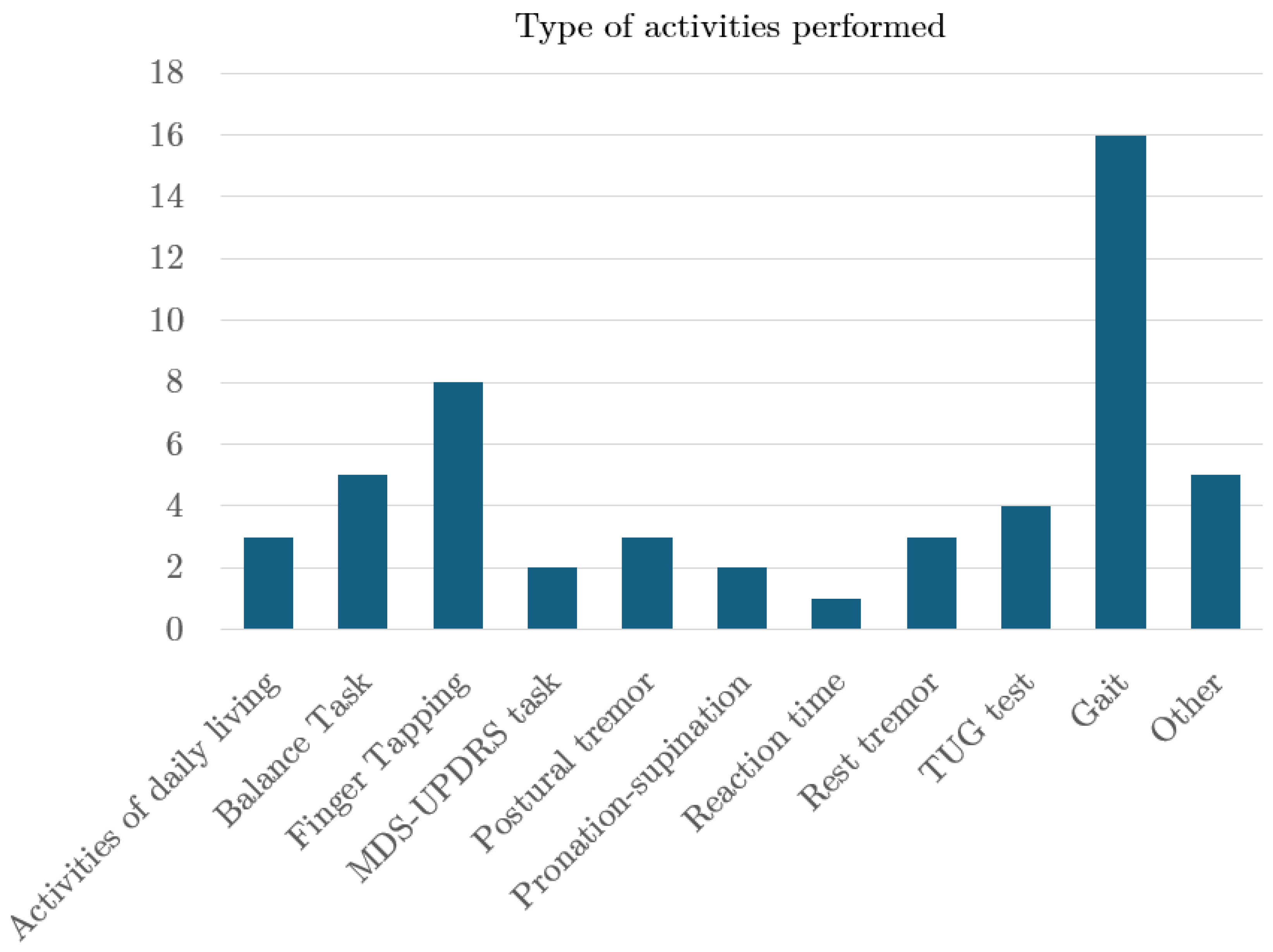

4.3. Study Design

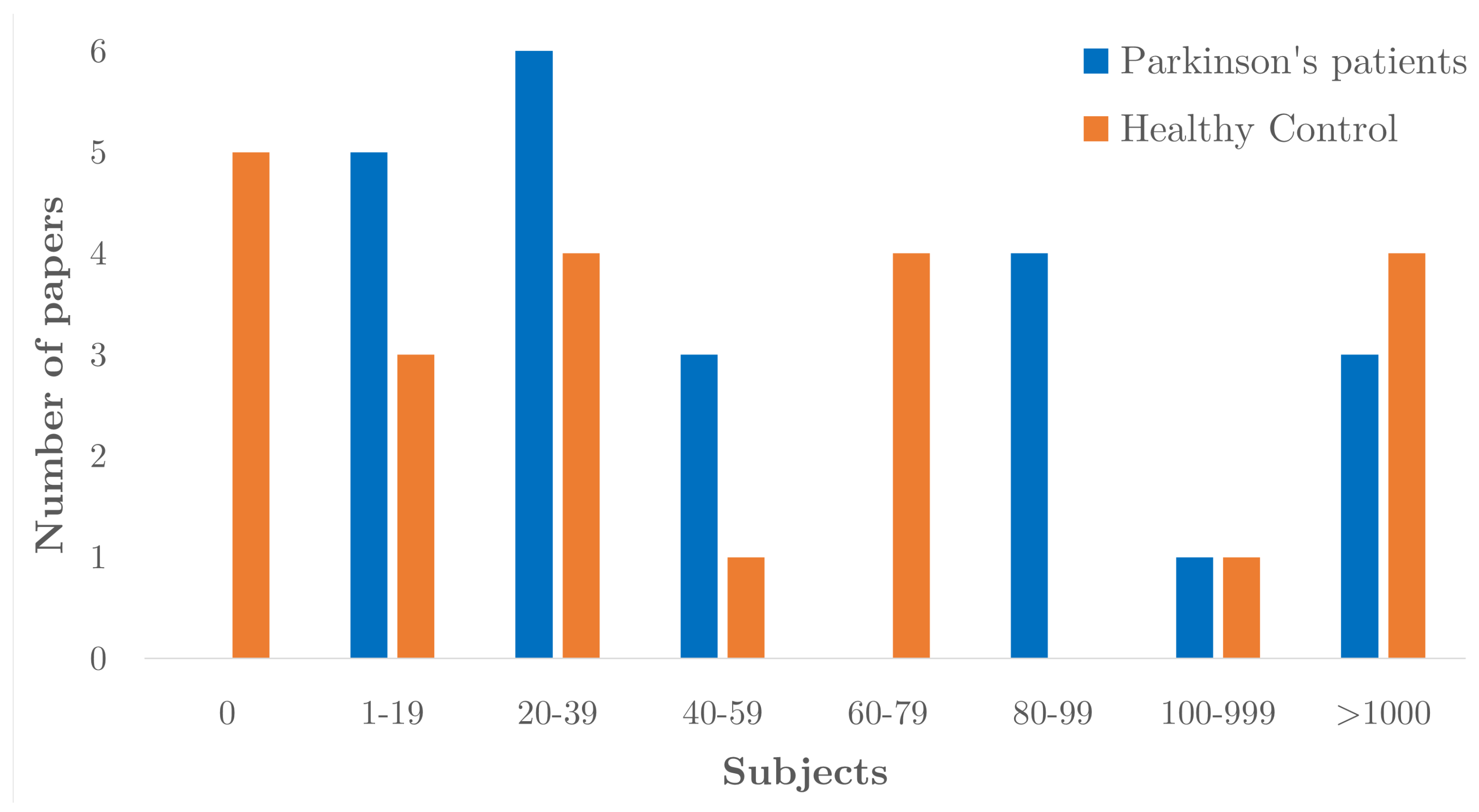

4.4. Participant Characteristics

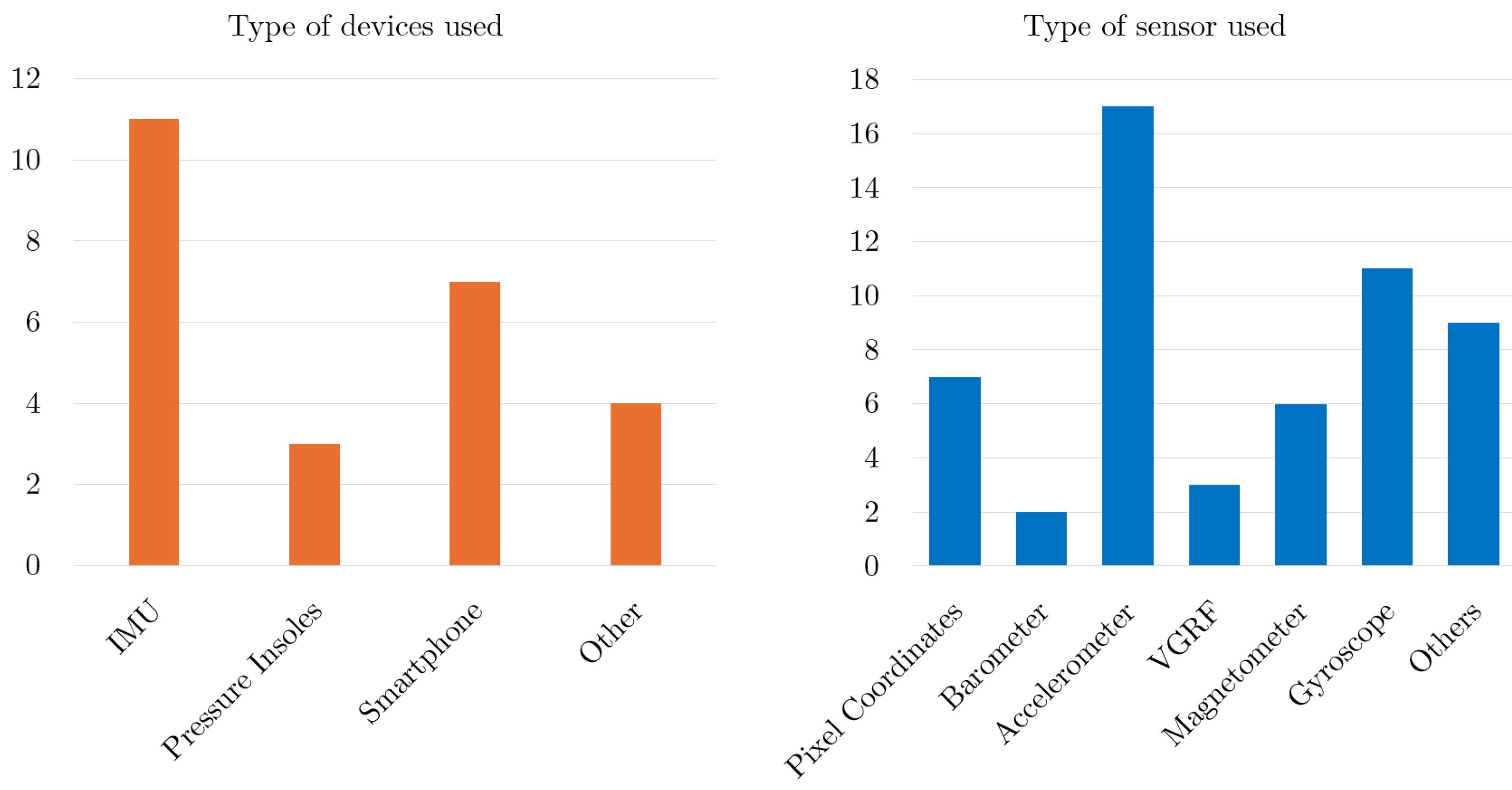

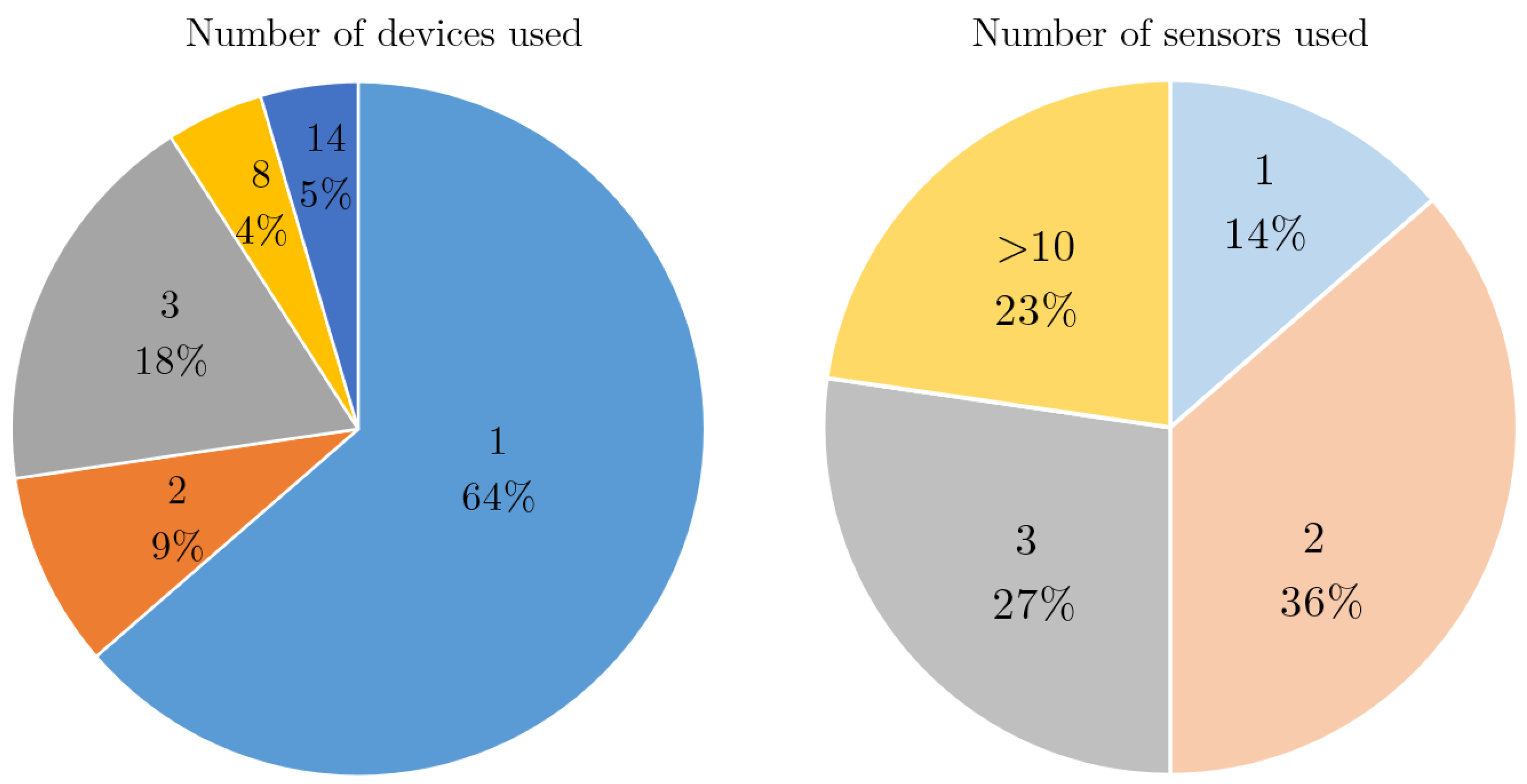

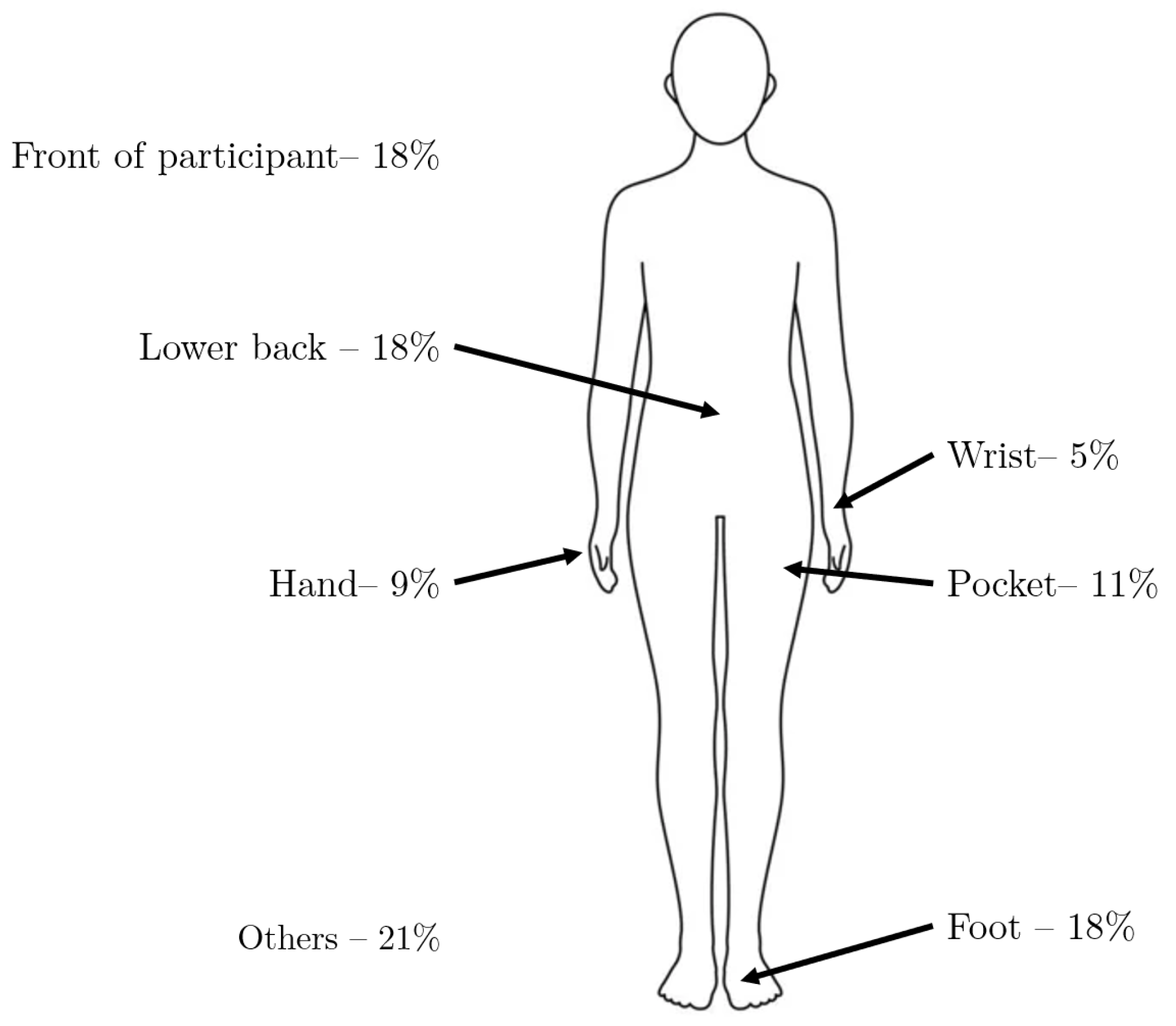

4.5. Device, Sensor and Body Location

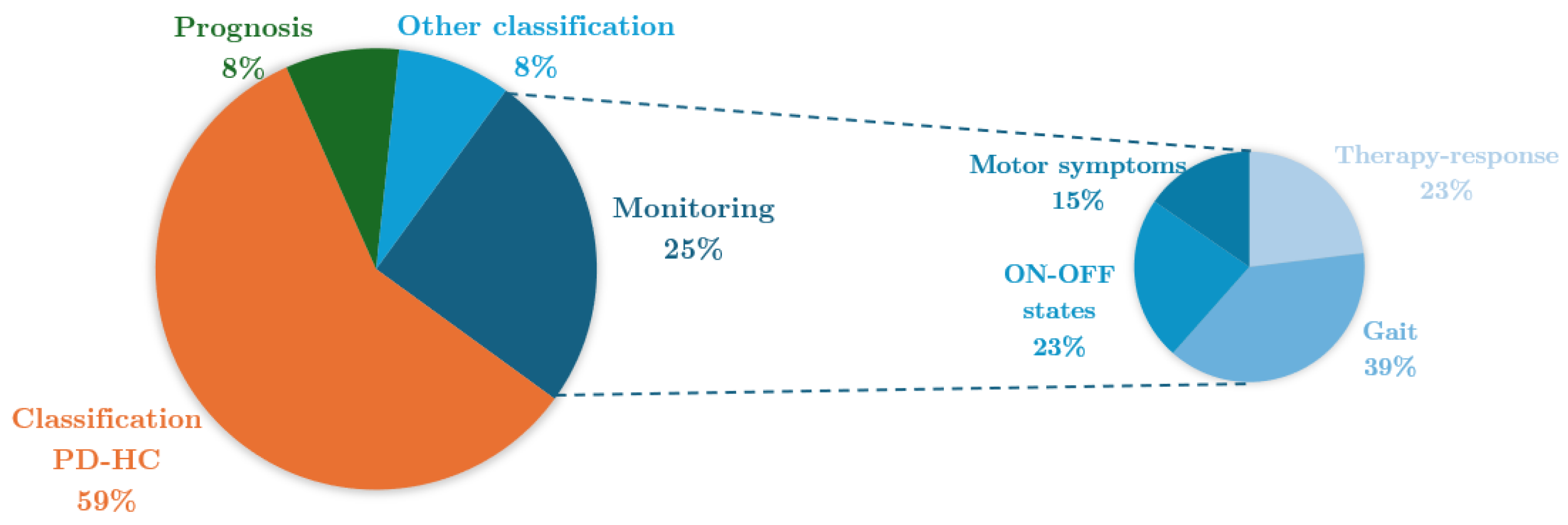

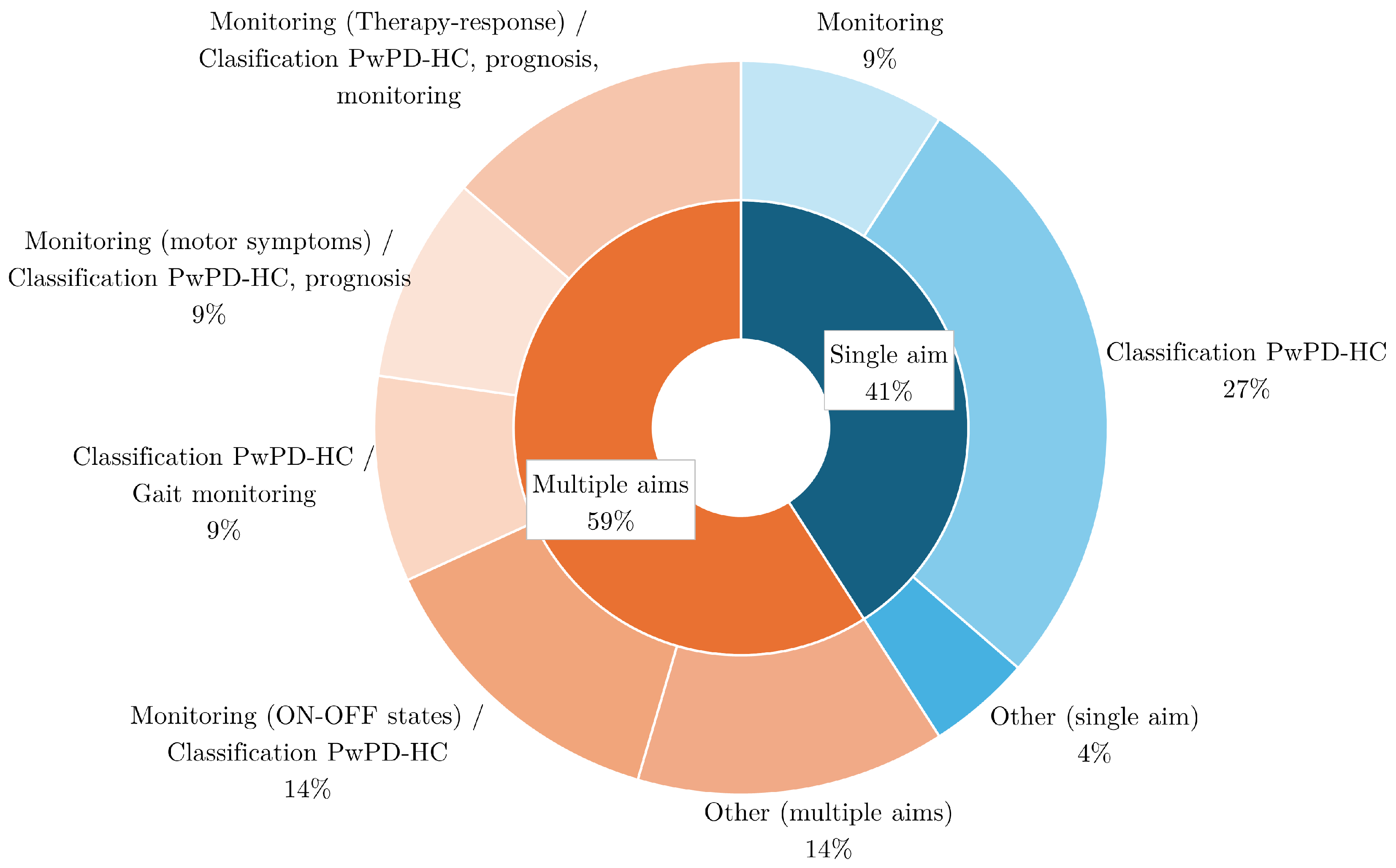

4.6. Aim

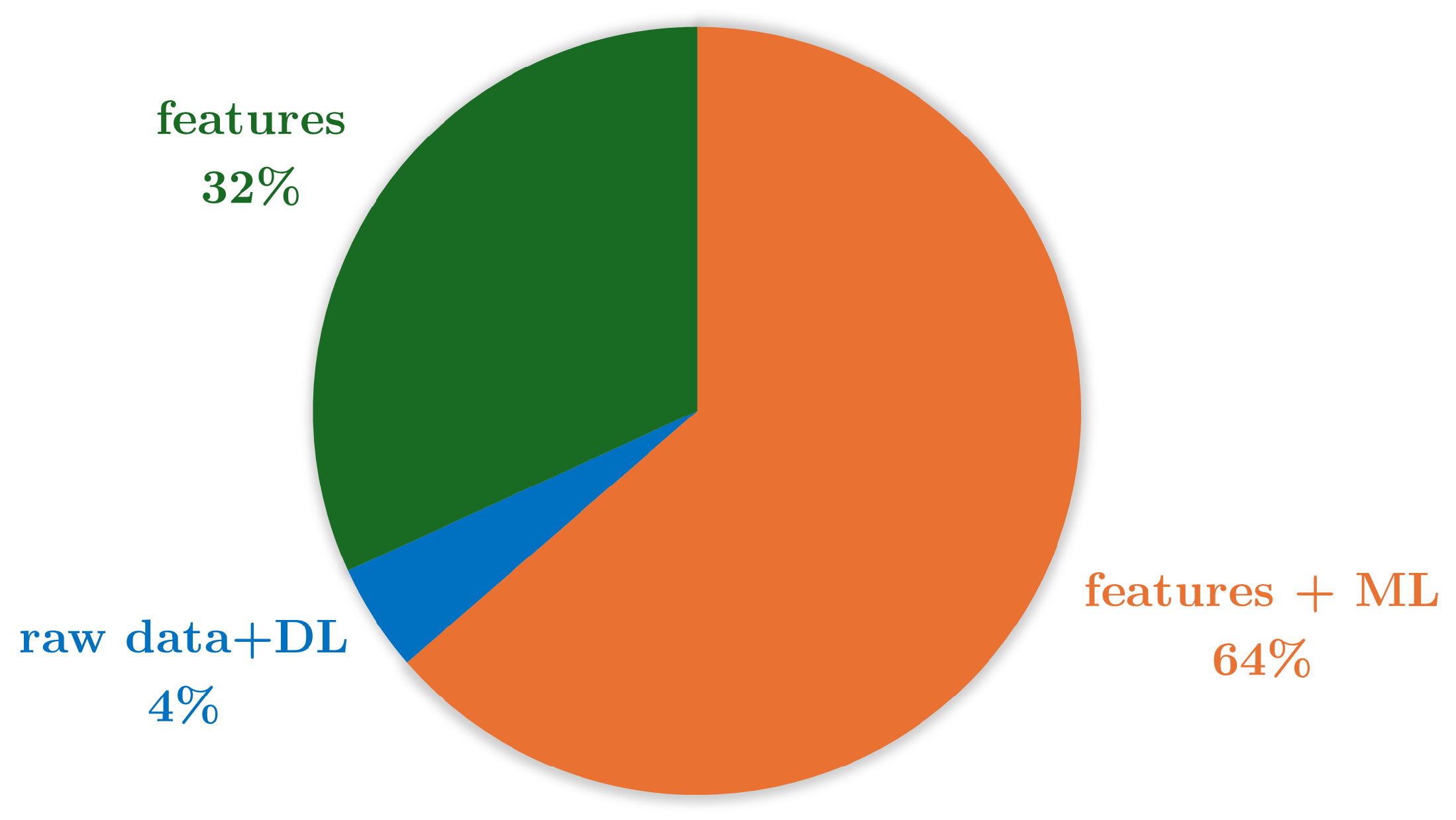

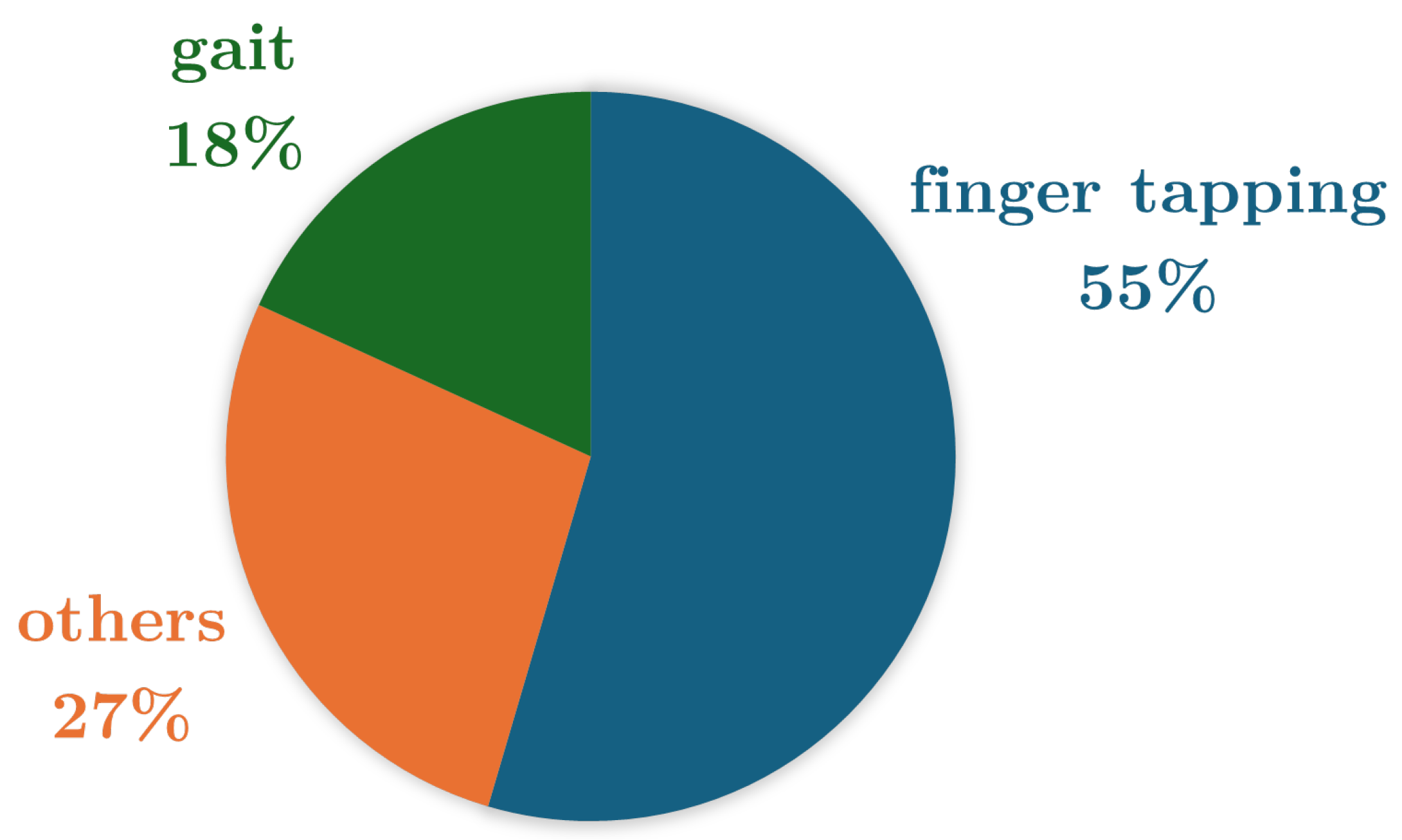

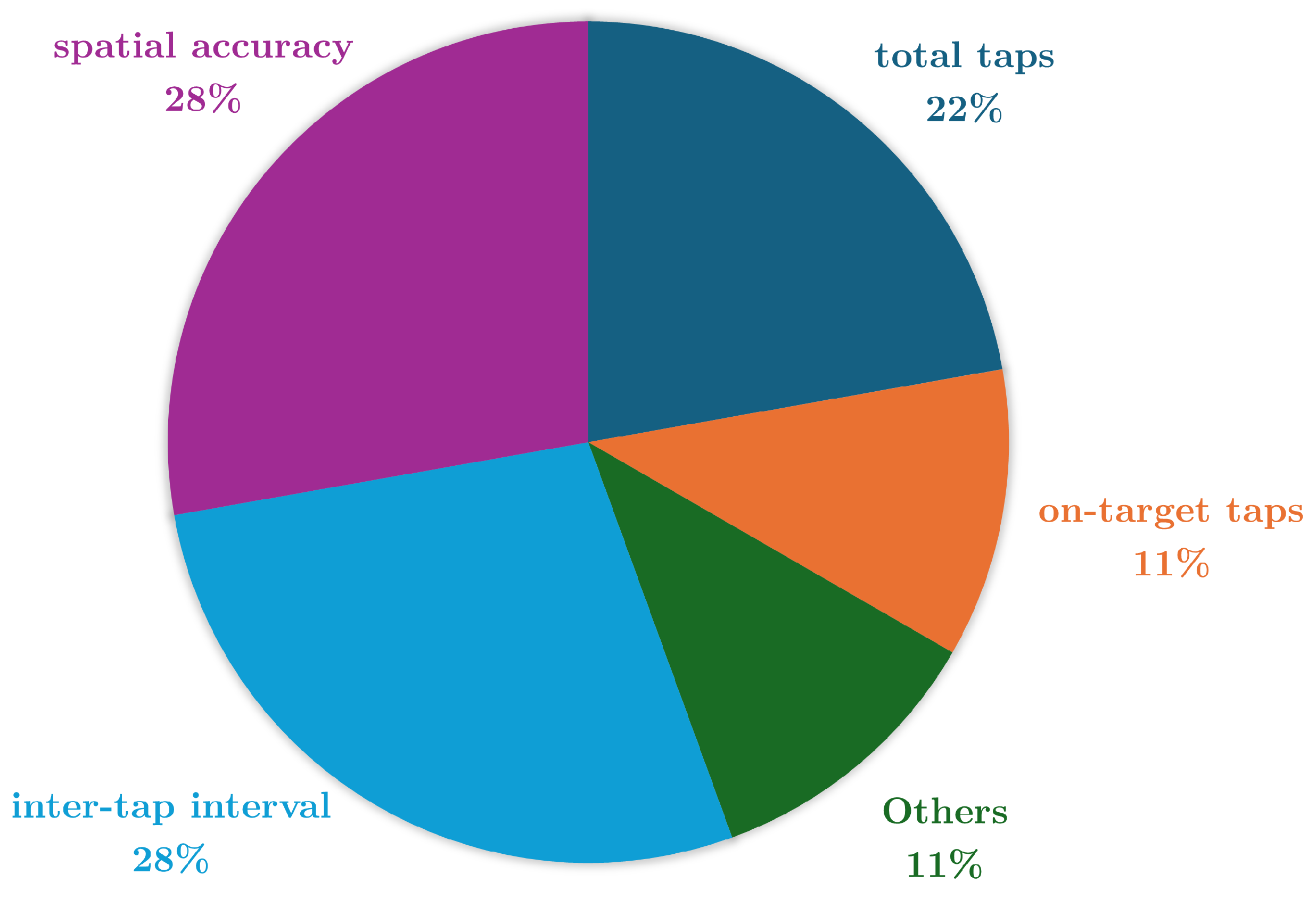

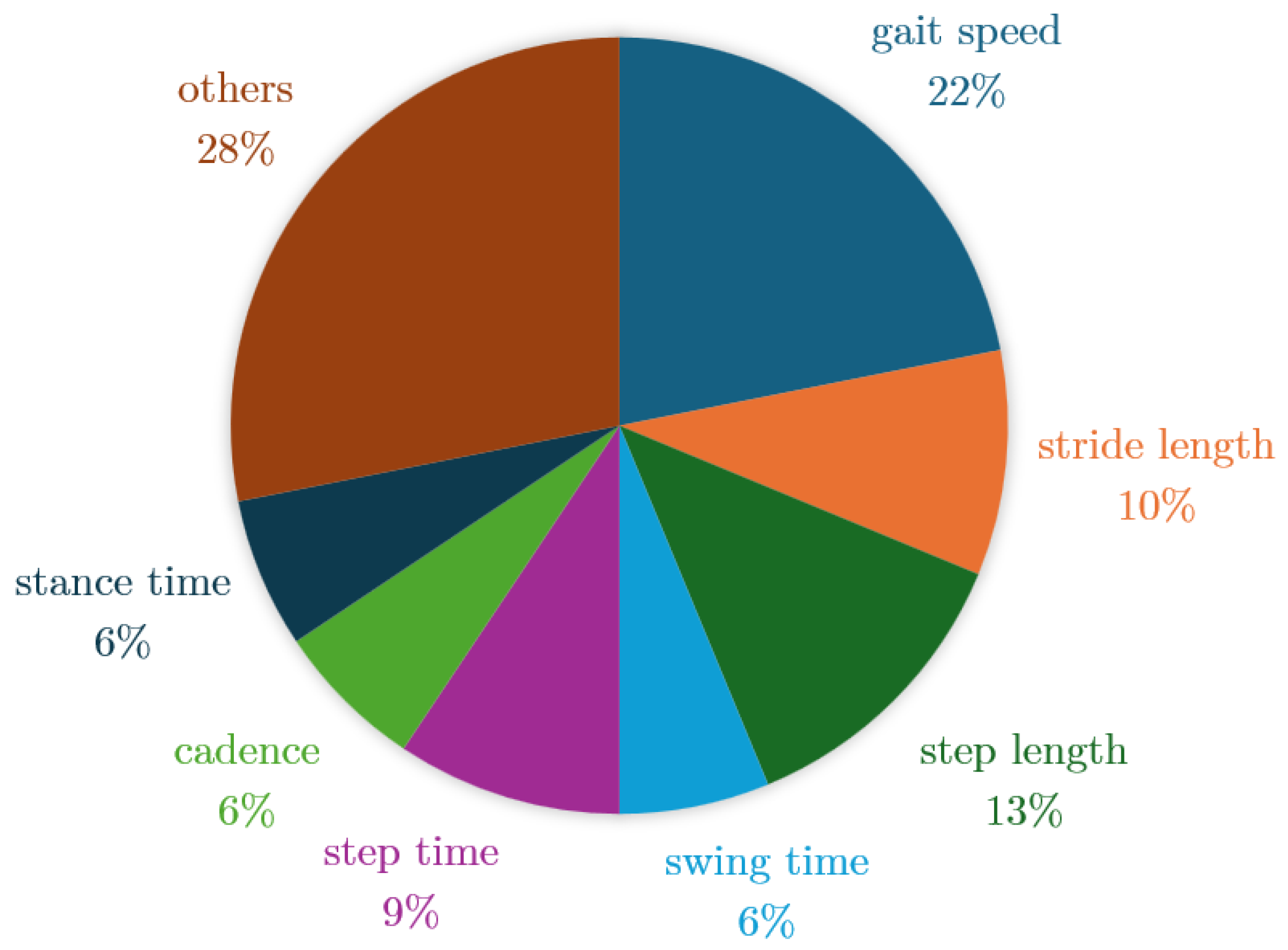

4.7. Endpoints

5. Discussion

5.1. Challenges

5.2. Limitations of this Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DB-MS-PD | Digital Biomarkers for Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| PwPD | Patients with Parkinson’s Disease |

| HC | Healthy Control |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Value |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| VGRF | Vertical Ground Reaction Force |

| TUG | Timed Up and Go |

| MDS-UPDRS | Movement Disorder Society-Sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale |

References

- Goetz, C.G. The history of Parkinson’s disease: early clinical descriptions and neurological therapies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2011, 1, a008862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, M.J.; Okun, M.S. Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Review. JAMA 2020, 323, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. Parkinson disease. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/parkinson-disease, 2022.

- Dorsey, E.R.; Sherer, T.; Okun, M.S.; Bloem, B.R. The Emerging Evidence of the Parkinson Pandemic. J Parkinsons Dis 2018, 8, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveinbjornsdottir, S. The clinical symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry 2016, 139, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, K.R.; Healy, D.G.; Schapira, A.H. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis and management. The Lancet Neurology 2006, 5, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, E.; Wenning, G.; Poewe, W. The diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet Neurology 2006, 5, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Mao, Z.H. Progression of motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience Bulletin 2012, 28, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Balbuena, L.; Ungvari, G.S.; Zang, Y.F.; Xiang, Y.T. Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. CNS Neurosci Ther 2021, 27, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankovic, J. Parkinson’s disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008, 79, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J. The Evolution of Diagnosis in Early Parkinson Disease. Archives of Neurology 2000, 57, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Pillay, V.; Choonara, Y.E. Advances in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Progress in Neurobiology 2007, 81, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levodopa and the Progression of Parkinson’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2004, 351, 2498–2508. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankovic, J. Motor fluctuations and dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease: clinical manifestations. Movement disorders: official journal of the Movement Disorder Society 2005, 20, S11–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord 2008, 23, 2129–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrag, A. How valid is the clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease in the community? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2002, 73, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A. Standard strategies for diagnosis and treatment of patients with newly diagnosed Parkinson disease: ITALY. Neurol Clin Pract 2013, 3, 476–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.B.; McGhee, D.J.; Counsell, C.E. Comparison of patient rated treatment response with measured improvement in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012, 83, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis-Martínez, R.; Monje, M.H.G.; Antonini, A.; Sánchez-Ferro, Á.; Mestre, T.A. Technology-Enabled Care: Integrating Multidisciplinary Care in Parkinson’s Disease Through Digital Technology. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 575975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigcha, L.; Borzì, L.; Amato, F.; Rechichi, I.; Ramos-Romero, C.; Cárdenas, A.; Gascó, L.; Olmo, G. Deep learning and wearable sensors for the diagnosis and monitoring of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 120541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.V.; McNames, J.; Mancini, M.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Nutt, J.G.; El-Gohary, M.; Lapidus, J.A.; Horak, F.B.; Curtze, C. Digital biomarkers of mobility in Parkinson’s disease during daily living. Journal of Parkinson’s disease 2020, 10, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, H.; Bontridder, N.; Petrovska-Delacréta, D.; Glaab, E.; et al. Leveraging the Potential of Digital Technology for Better Individualized Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Frontiers in Neurology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chudzik, A.; Śledzianowski, A.; Przybyszewski, A.W. Machine Learning and Digital Biomarkers Can Detect Early Stages of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Sensors 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonato, P. Wearable sensors and systems. From enabling technology to clinical applications. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag 2010, 29, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ometov, A.; Shubina, V.; Klus, L.; Skibińska, J.; Saafi, S.; Pascacio, P.; Flueratoru, L.; Gaibor, D.Q.; Chukhno, N.; Chukhno, O.; et al. A Survey on Wearable Technology: History, State-of-the-Art and Current Challenges. Computer Networks 2021, 193, 108074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.M.A.; Mahgoub, I.; Du, E.; Leavitt, M.A.; Asghar, W. Advances in healthcare wearable devices. npj Flexible Electronics 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Runge, R.; Snyder, M. Wearables and the medical revolution. Per Med 2018, 15, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.; Healey, J. 2006’s Wearable Computing Advances and Fashions. IEEE Pervasive Computing 2007, 6, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Yin, Z. Human Activity Recognition Using Wearable Sensors by Deep Convolutional Neural Networks 2015. p. 1307–1310.

- Borzì, L.; Sigcha, L.; Olmo, G. Context Recognition Algorithms for Energy-Efficient Freezing-of-Gait Detection in Parkinsons Disease. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, D.; Lee, J.; Qiao, S.; Ghaffari, R.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.E.; Song, C.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, D.J.; Jun, S.W.; et al. Multifunctional wearable devices for diagnosis and therapy of movement disorders. Nature Nanotechnology 2014, 9, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, S.D.; Godfrey, A.; Mazzà, C.; Lord, S.; Rochester, L. Free-living monitoring of Parkinson’s disease: Lessons from the field. Movement Disorders 2016, 31, 1293–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Lei, J. Evaluating the Consistency of Current Mainstream Wearable Devices in Health Monitoring: A Comparison Under Free-Living Conditions. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2017, 19, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guk, K.; Han, G.; Lim, J.; Jeong, K.; Kang, T.; Lim, E.K.; Jung, J. Evolution of Wearable Devices with Real-Time Disease Monitoring for Personalized Healthcare. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdmier, C.; Hatcher, J.; Lee, M. Wearable device implications in the healthcare industry. Journal of Medical Engineering & Technology 2016, 40, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.S.; Asch, D.A.; Volpp, K.G. Wearable Devices as Facilitators, Not Drivers, of Health Behavior Change. JAMA 2015, 313, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, C.; Rouaud, T.; Grabli, D.; Benatru, I.; Remy, P.; Marques, A.R.; Drapier, S.; Mariani, L.L.; Roze, E.; Devos, D.; et al. Overview on wearable sensors for the management of Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinson’s Disease 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, W.; Alajlani, M.; Abd-alrazaq, A. An Exploration of Wearable Device Features Used in UK Hospital Parkinson Disease Care: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2023, 25, e42950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovini, E.; Maremmani, C.; Cavallo, F. How Wearable Sensors Can Support Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis and Treatment: A Systematic Review. Front Neurosci 2017, 11, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Din, S.; Kirk, C.; Yarnall, A.J.; Rochester, L.; Hausdorff, J.M. Body-Worn Sensors for Remote Monitoring of Parkinson’s Disease Motor Symptoms: Vision, State of the Art, and Challenges Ahead. J Parkinsons Dis 2021, 11, S35–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strimbu, K.; Tavel, J.A. What are biomarkers? Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010, 5, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2001, 69, 89–95. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Gunasekaran, T.I.; Cho, Y.H.; Choi, S.M.; Song, M.K.; Cho, S.H.; Kim, J.; Song, H.C.; Choi, K.Y.; Lee, J.J.; et al. Diagnostic Blood Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patient-Focused Drug Development: Collecting Comprehensive and Representative Input. NPJ Digit Med 2020, 46.

- Vasudevan, S.; Saha, A.; Tarver, M.E.; Patel, B. Digital biomarkers: Convergence of digital health technologies and biomarkers. NPJ Digit Med 2022, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manta, C.; Patrick-Lake, B.; Goldsack, J.C. Digital Measures That Matter to Patients: A Framework to Guide the Selection and Development of Digital Measures of Health. Digit Biomark 2020, 4, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insel, T.R. Digital Phenotyping: Technology for a New Science of Behavior. JAMA 2017, 318, 1215–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babrak, L.M.; Menetski, J.; Rebhan, M.; Nisato, G.; Zinggeler, M.; Brasier, N.; Baerenfaller, K.; Brenzikofer, T.; Baltzer, L.; Vogler, C.; et al. Traditional and Digital Biomarkers: Two Worlds Apart? Digit Biomark 2019, 3, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Califf, R.M. Biomarker definitions and their applications. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2018, 243, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. International journal of surgery (London, England) 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Yamada, Y.; Rogers, J.L.; Shinakwa, K.; Nemoto, M.; Nemoto, K.; Arai, T. An Automated Digital Biomarker of Mobility. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Digital Health (ICDH); IEEE, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.V.; McNames, J.; Mancini, M.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Nutt, J.G.; El-Gohary, M.; Lapidus, J.A.; Horak, F.B.; Curtze, C. Digital Biomarkers of Mobility in Parkinson’s Disease During Daily Living. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease 2020, 10, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZhuParris, A.; Thijssen, E.; Elzinga, W.O.; Makai-Bölöni, S.; Kraaij, W.; Groeneveld, G.J.; Doll, R.J. Treatment Detection and Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, Part III Estimation Using Finger Tapping Tasks. Movement Disorders 2023, 38, 1795–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.V.; McNames, J.; Harker, G.; Mancini, M.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Nutt, J.G.; El-Gohary, M.; Curtze, C.; Horak, F.B. Effect of Bout Length on Gait Measures in People with and without Parkinson’s Disease during Daily Life. Sensors 2020, 20, 5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atrsaei, A.; Corrà, M.F.; Dadashi, F.; Vila-Chã, N.; Maia, L.; Mariani, B.; Maetzler, W.; Aminian, K. Gait speed in clinical and daily living assessments in Parkinson’s disease patients: performance versus capacity. npj Parkinson’s Disease 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, L.; Shi, J.; Rochester, L.; Del Din, S.; Pantall, A. Entropy of Real-World Gait in Parkinson’s Disease Determined from Wearable Sensors as a Digital Marker of Altered Ambulatory Behavior. Sensors 2020, 20, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Albin, R.L.; Guan, Y. Heterogeneous digital biomarker integration out-performs patient self-reports in predicting Parkinson’s disease. Communications Biology 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidya, B.; P, S. Gait based Parkinson’s disease diagnosis and severity rating using multi-class support vector machine. Applied Soft Computing 2021, 113, 107939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, P.; Kumar, N. Novel machine learning-based hybrid strategy for severity assessment of Parkinson’s disorders. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing 2022, 60, 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goni, M.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Far, M.S.; Patil, K.R.; Dukart, J. Smartphone-Based Digital Biomarkers for Parkinson’s Disease in a Remotely-Administered Setting. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 28361–28384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissel, B.D.; Mitsi, G.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Papapetropoulos, S.; Larkin, S.; López Castellanos, J.R.; Shanks, E.; Duker, A.P.; Rodriguez-Porcel, F.; Vaughan, J.E.; et al. Tablet-Based Application for Objective Measurement of Motor Fluctuations in Parkinson Disease. Digital Biomarkers 2018, 1, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lazzaro, G.; Ricci, M.; Saggio, G.; Costantini, G.; Schirinzi, T.; Alwardat, M.; Pietrosanti, L.; Patera, M.; Scalise, S.; Giannini, F.; et al. Technology-based therapy-response and prognostic biomarkers in a prospective study of a de novo Parkinson’s disease cohort. npj Parkinson’s Disease 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Baig, F.; Lo, C.; Barber, T.R.; Lawton, M.A.; Zhan, A.; Rolinski, M.; Ruffmann, C.; Klein, J.C.; Rumbold, J.; et al. Smartphone motor testing to distinguish idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder, controls, and PD. Neurology 2018, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, B.R.; Premoli, I.; McManus, K.; McGrath, D.; Caulfield, B. Predicting Fall Counts Using Wearable Sensors: A Novel Digital Biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease. Sensors 2021, 22, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, R.Z.U.; Buckley, C.; Mico-Amigo, M.E.; Kirk, C.; Dunne-Willows, M.; Mazza, C.; Shi, J.Q.; Alcock, L.; Rochester, L.; Del Din, S. Accelerometry-Based Digital Gait Characteristics for Classification of Parkinson’s Disease: What Counts? IEEE Open Journal of Engineering in Medicine and Biology 2020, 1, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Mishra, R.k.; Hall, A.J.; Casado, J.; Cole, R.; Nunes, A.S.; Barchard, G.; Vaziri, A.; Pantelyat, A.; Wills, A.M. Remote at-home wearable-based gait assessments in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy compared to Parkinson’s Disease. BMC Neurology 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahadevan, N.; Demanuele, C.; Zhang, H.; Volfson, D.; Ho, B.; Erb, M.K.; Patel, S. Development of digital biomarkers for resting tremor and bradykinesia using a wrist-worn wearable device. NPJ digital medicine 2020, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, H.R.; Branquinho, A.; Pinto, J.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Santos, C.P. Digital biomarkers of mobility and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease based on a wearable motion analysis LAB. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2024, 244, 107967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, L.J.; Raykov, Y.P.; Krijthe, J.H.; Silva de Lima, A.L.; Badawy, R.; Claes, K.; Heskes, T.M.; Little, M.A.; Meinders, M.J.; Bloem, B.R. Real-Life Gait Performance as a Digital Biomarker for Motor Fluctuations: The Parkinson@Home Validation Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020, 22, e19068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoulos, I.G.; Mitsi, G.; Stavrakoudis, A.; Papapetropoulos, S. Application of Machine Learning in a Parkinson’s Disease Digital Biomarker Dataset Using Neural Network Construction (NNC) Methodology Discriminates Patient Motor Status. Frontiers in ICT 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsmeier, F.; Taylor, K.I.; Kilchenmann, T.; Wolf, D.; Scotland, A.; Schjodt-Eriksen, J.; Cheng, W.; Fernandez-Garcia, I.; Siebourg-Polster, J.; Jin, L.; et al. Evaluation of smartphone-based testing to generate exploratory outcome measures in a phase 1 Parkinson’s disease clinical trial. Movement Disorders 2018, 33, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahandi Far, M.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Goni, M.; Dukart, J. Exploring Test-Retest Reliability and Longitudinal Stability of Digital Biomarkers for Parkinson Disease in the m-Power Data Set: Cohort Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2021, 23, e26608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- mPower Public Researcher Portal. Mobile Parkinson Disease Study, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Hausdorff, J.M. Gait in Parkinson’s Disease, 2008.

- Adams, J.; Kangarloo, T.; Gong, Y.; et al. Using a smartwatch and smartphone to assess early Parkinson’s disease in the WATCH-PD study over 12 months. npj Parkinson’s Disease 2024, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzì, L.; Varrecchia, M.; Sibille, S.; Olmo, G.; Artusi, C.A.; Fabbri, M.; Rizzone, M.G.; Romagnolo, A.; Zibetti, M.; Lopiano, L. Smartphone-Based Estimation of Item 3.8 of the MDS-UPDRS-III for Assessing Leg Agility in People With Parkinson’s Disease. IEEE Open Journal of Engineering in Medicine and Biology 2020, 1, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, C.R.; Bernstein, M.A.; Fox, N.C.; Thompson, P.; Alexander, G.; Harvey, D.; Borowski, B.; Britson, P.J.; L. Whitwell, J.; Ward, C.; et al. The Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI): MRI methods. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2008, 27, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siirtola, P.; Koskimäki, H.; Röning, J. OpenHAR: A Matlab Toolbox for Easy Access to Publicly Open Human Activity Data Sets. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 ACM International Joint Conference and 2018 International Symposium on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Wearable Computers. ACM, 2018, UbiComp ’18. [CrossRef]

| Reference | Study Design | Participants | Device, sensors, Number (device, sensor), Body location | Aim | End point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [51] | Gait (Physionet database) | PwPD: N = 90 (34F; 56M) HC: N = 62 (34F; 28M) | Pressure insoles VGRF sensors N = (1,16) Foot (8 each) | Gait monitoring | Gait features that impact the predicted TUG scores are gait speed-based features (percentiles, mean, and kurtosis), with 84,8% accuracy. |

| [52] | Gait | PwPD: N = 29 (12F; 17M) HC: N = 27 (14F; 13M) | IMU (Opals by APDM) 3-axial accelerometer, 3-axial gyroscope and 3-axial magnetometer N=(3,3) Foot (1 each) and lower back | Classification PwPD-HC | Turning and gait indicators discriminate PwPD from HC (Turn angle, swing time variability adn stride length with AUC = 0,87 - 0,89). |

| [53] | Finger Tapping - Index and middle finger tapping (IMFT) - Alternate index finger tapping (IFT) - Thumb index finger tapping (TIFT) | PwPD: N = 20 (6F; 14M) | Tablet (IMFT and IFT) and Biometrics (TIFT) Pixel Coordinates (IMFT and IFT) and Goniometer (TIFT) N = (2,2) Front of participant (IMFT and IFT) and hand (TIFT) | Therapy response monitoring and Classification of subjects with therapy and placebo | The IFT features (total taps, bivariate contour ellipse area, spatial error, velocity changes, intertap intervals) provides the best performance in estimating MDS-UPDRS III, with p <0,001. |

| [54] | Gait | PwPD: N = 29 (12F; 17M) HC: N = 20 (8F; 2M) | IMU (Opals by APDM) 3-axial accelerometer, 3-axial gyroscope and 3-axial magnetometer N=(3,3) Foot (1 each) and lower back. | Classification PwPD-HC | Gait measures (gait speed, stride length) could be used to classify PwPD from HC, with AUC > 0,8. |

| [55] | Gait Activities of daily living | PwPD: N = 27 (11F; 16M) | IMU (RehaGait) (clinical assessment) and IMU (Physilog® 5) (home assessment) 3-axial accelerometer and 3-axial gyroscope (clinical assessment), and 3-axial accelerometer, 3-axial gyroscope, and barometrer (home assessment) N=(3,3) Foot (1 each in clinical assessment) (only 1 in home assessment) | Gait monitoring and treatment detection | Gait speed could be used to control of medication intake in PD. |

| [56] | Gait | PwPD: N = 5 HC: N = 5 | IMU (Axivity AX3) 3-axial accelerometer N=(1,1) Lower back | Classification PwPD-HC | The sample entropy of the gait signal of PwPD are higher than HC participants. |

| [57] | Gait Balance Task Finger Tapping (Mpower database) | PwPD: N = 1057 (359F; 698M)HC:N = 5343 (1014F; 4329M) | Smartphone 3-axial accelerometer (gait and balance) and pixel coordinates (tapping)N=(1,2) Pocket (gait and balance) and front of participant (tapping) | Classification PwPD-HC | Tapping positions (Centered tapping coordinates) are the most relevant data (AUC = 0,935) for PD detection. |

| [58] | Gait (Physionet database) | PwPD: N = 93 (35F; 58M) HC: N = 73 (33F; 40M) | Pressure insoles VGRF sensors N=(1,16) Foot (8 each) | Gait monitoring and classification PwPD-HC | Gait parameters (stride time, step time, stance time, swing time, cadence, step length, stride length, gait speed) differentiate PD severity and HC with 98,65% accuracy. |

| [59] | Gait (Physionet database) | PwPD: N = 93 (35F; 58M) HC: N = 72 (32F; 40M) | Pressure insoles VGRF sensors N=(1,16) Foot (8 each) | Gait monitoring and classification PwPD-HC | Gait parameters (step length, force variations at heel strike, centre of pressure variability, swing stance ratio, and double support phase) are able to detect PwPD with 99,9% accuracy and its severity shows = 98,7%. |

| [60] | Gait Balance Task Finger Tapping (Mpower database) | PwPD: N = 610 (211F; 399M) (gait), 612 (211F; 401M) (balance), 970 (340F; 630M) (tapping) HC: N = 787 (147F; 640M) (gait), 803 (150F; 653M) (balance), 1257 (239F; 1018M) (tapping) | Smartphone 3-axial accelerometer (gait and balance) and pixel coordinates (tapping)N=(1,2) Pocket (gait and balance) and front of participant (tapping) | Classification PwPD-HC | Tapping features (inter-tap interval (range, maximum value and Teager-Kaiser energy operator) detect PwPD with AUC = 0,74. |

| [61] | Finger Tapping Pronation-supination | PwPD: N = 11 (3F; 8M) HC: N = 11 (6F; 5M) | Smartphone Pixel coordinates N=(1,1) Front of participant | Classification PwPD-HC and ON-OFF states monitoring | Tapping features (total taps, tap interval, and tap accuracy) can detect PwPD with p <0,0005 and detect ON/OFF state with AUC 0,82 |

| [62] | Pronation-supination Leg Agility Toe Tapping TUG test Postural stability Postural Tremor Rest Tremor | PwPD: N = 36 (9F; 27M) | IMU (Movit G1) 3-axial accelerometer and 3-axial gyroscope N=(14,2) Lower back, upper back, forearm (1 each), arm (1 each), upper leg (1 each), lower leg (1 each), hand (1 each), foot (1 each) | Prognosis (motor symptoms) and therapy response monitoring | A correlation was found between motor symptoms progression and some features (toe tapping amplitude decrement, velocity of arms and legs, sit-to-stand time, p <0,01). |

| [63] | Balance Task Gait Finger tapping Reaction time Rest tremor Postural tremor | PwPD: N = 334 (125F; 209M) HC: N = 84 (17F; 67M) iRBD (idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder): N = 104 (88F; 16M) | Smartphone 3-axial accelerometer (Balance, gait, rest tremor and postural tremor) and pixel coordinates (Tapping and reaction time) N=(1,2) Pocket (balance and gait), front of participant (tapping and reaction time) and hand (postural and rest tremor) | Clasification PwPD-HC and clasification PwPD- iRBD | Postural tremor (mean squared energy, azimuth, 25th quartile, mode, radius) and rest tremor (entropy, root mean square) were the most discriminatory task between PD-HC-iRBD, with 85-88% of sensitivity. |

| [64] | TUG test | PwPD dataset 1: N = 15 (5F; 10M) PwPD dataset 2: N = 27 (9F; 17M) HC: N = 1015 (671F; 344M) | IMU (Kinesis QTUG) 3-axial accelerometer and 3-axial gyroscope N=(1,2) Shin | Fall risk prognosis and gait monitoring | The mobility parameters (speed, turn, transfers, symmetry, variability) could be used to predict number of fall counts of PwPD ( = 43%) |

| [65] | Gait | PwPD: N = 81 (28F; 53M) HC: N = 61 (27F; 34M) | IMU (Axivity AX3)3-axial accelerometer N=(1,1) Lower Back | Clasification PwPD-HC | Gait features (root mean square values, power spectral density, gait speed velocity, step length, step time and age) classify PwPD with AUC = 0,94. |

| [66] | Gait TUG test Sit-to-tand test | PwPD: N = 10 (4F; 6M) PSP (Progressive Supranuclear Palsy): N = 10 (4F; 6M) | IMU (LEGSys)3-axial accelerometer, 3-axial gyroscope, 3-axial magnetometer N=(3,3) Shin (1 each) and lower Back | Classification PwPD-PSP | Gait speed was significantly slower in PSP (p <0,001). |

| [67] | Activities of daily living MDS-UPDRS task | PwPD: N = 31 (11F; 20M) HC: N = 50 (27F; 23M) | IMU (Opals by APDM) 3-axial accelerometer, 3-axial gyroscope and 3-axial magnetometer N=(1,3) Wrist | Motor symptoms monitoring; Therapy-response monitoring | RMS (amplitude) of the magnitude vector for resting tremor (p <0,0004) and RMS (amplitude) and jerk (smoothness) of the magnitude vector forbradykinesia (p <0,0001) achieve agreement with clinical assessment of symptom severity and treatment-related changes in motor states. |

| [68] | Gait | PwPD: N=40 (19F; 21M) | IMU (+sMotion ) 3-axial accelerometer and 3-axial gyroscope N=(1,2) Lower back | Classification motor condition and Quality of Life. | Gait Features (velocity pace, SD swing time variability, Antero-posterior center of mass angle of postural control) classify UPDRS-III severity with p <0,001. Gait Features (gait speed, step time rhythm, stance time, step length) correlated with PDQ39 with p <0,001 |

| [69] | Activities of daily living TUG test Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale MDS-UPDRS task Gait | PwPD: N = 18 (7F; 11M) HC: N = 24 (11F; 13M) | IMU (Physilog® 4), Android smartwatch, Android smartphone, Empatica E4 smartwatch 3-axial accelerometer, 3-axial gyroscope, 3-axial magnetometer, and barometer (IMU), 3-axial accelerometer, 3-axial gyroscope, barometer, and light (Android smartwatch), 3-axial accelerometer, 3-axial magnetometer, light, proximity, GPS, WiFi, and cellular networks (Android smartphone), and Galvanic skin response, photoplethysmogram, skin temperature, 3-axial accelerometer (Empatica) N = (8,12) Ankles (1 each), wrist (1 each), lower back (IMU), wrist (Android smartwatch), pocket (Android smartphone), and wrist (Empatica) | Classification of PwPD-HC; ON-OFF states monitoring | The total power in the 0.5- to 10-Hz band was most discriminate feature to classify PwPD-HC (AUC = 0,76) and ON-OFF detection (AUC = 0,84). |

| [70] | Finger Tapping - Two-target finger tapping test - Reaction time - Pronation- supination | PwPD: N = 19 HC: N = 17 | Tablet Pixel coordinates N=(1,1) Front of participant | Classification of PwPD-HC and ON-OFF states monitoring | All test combined classify PwPD-HC with 93.11% accuracy. Most differentiating test is reaction time (inter-tap interval, tap accuracy) with 83.90% accuracy. ON-OFF state classifies with 76,50% accuracy. |

| [71] | Activities of Daily Living Rest tremor Postural tremor Finger tapping Balance task Gait | PwPD: N = 43 (8F; 35M) HC: N = 35 (8F; 27M) | Smartphone 3-axial accelerometer, 3-axial gyroscope and 3-axial magnetometer N=(1,3) Waist (balance and gait), hand (tremor) and front of participant (tapping) | Classification PwPD-HC and Motor symptoms monitoring | Tapping (inter-tap variability), rest tremor (acceleration skewness), postural tremor (total power of accelerometer), balance (mean velocity), gait (turn speed) differentiated HC from PwPD and PD abnormalities (p<0.005). |

| [72] | Gait Balance Task Finger Tapping (Mpower database) | PwPD: N = 610 (211F; 399M) (gait), 612 (211F; 401M) (balance), 970 (340F; 630M) (tapping) HC: N = 807 (152F; 655M) (gait), 823 (155F; 668M) (balance), 1674 (304F; 1370M) (tapping) | Smartphone 3-axial accelerometer (gait and balance) and pixel coordinates (tapping) N=(1,2) Pocket (gait and balance) and front of participant (tapping) | Classification PwPD-HC and therapy response monitoring | Tapping features (total taps, inter-tap intervals, median/standard deviation absolute deviations, correlation X-Y tap) displayed the best performance in classify PwPD-HC (p<0,05). |

| Task | Diagnosis | Treatment | Severity | UPDRS–III |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finger tapping | AUC 0.74–0.95 | Acc 0.75–0.84 | - | r = 0.51–0.69, MAE=8 |

| Gait | AUC 0.76–0.98 | AUC 0.82 | AUC 0.85–0.98 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).