1. Introduction

Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is the fastest-growing and the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s Disease. An estimated number of 10 million people suffered globally from PD in 2020 [

1,

2]. By 2040, likely more than 17 million people will live with PD [

3,

4]. PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disease presenting motor and non-motor symptoms [

5,

6], and its prevalence increases with age and has both genetic as well as environmental underlying causes [

7,

8,

9].

The main line of treatment for PD currently involves levodopa administration to relieve symptoms, mainly slowness of movement and loss of movement spontaneity. In the early stages of PD, levodopa (LD) therapy is highly effective in alleviating symptoms. However, as the disease progresses, fluctuations in medication efficacy—commonly termed “on-off” fluctuations—become more pronounced, especially in response to LD. These fluctuations result in alternating phases of symptom relief and exacerbation. During “on” phases, the medication effectively improves motor function, allowing relatively normal mobility. In contrast, “off” phases are characterized by significant motor impairments, including muscle stiffness, uncontrollable twitching, and restricted movement. Additionally, dosing may cause excessive response, leading to involuntary hyper-mobility, known as dyskinesia [

10,

11,

12,

13].

These fluctuations arise due to the brain’s declining capacity to process and store dopamine uniformly as PD advances, complicating consistent dopamine delivery with oral medications like LD. With each dose of LD, a new “levodopa cycle” is initiated: Absorption in the small intestine occurs rapidly, and the peak plasma concentration is typically reached within 0.5-2 hours after administration. After passing the blood-brain barrier, LD gets metabolised to dopamine, activating postsynaptic dopaminergic receptors. After reaching peak plasma concentration, LD plasma concentrations begin to decline, resulting in significantly lower levels around 4-5 hours post-administration [

14,

15]. Factors contributing to these fluctuations include irregular gastrointestinal absorption, often slowed in PwPDs, and diminished dopamine storage, which accelerates the reduction of dopamine levels in the central nervous system (CNS). Consequently, these fluctuations compromise patients’ quality of life by introducing unpredictability and diminishing control over bodily movements [

10,

11,

12].

Pharmacokinetics of orally administered LD are likely to cause motor fluctuations: When peak LD blood concentration is reached, patients might experience a dyskinetic (DYS) motor state, whereas a low in LD blood concentration might result in an OFF state [

16,

17,

18]. The goal of PD treatment is to reduce OFF and DYS phases and keep the patient symptom free for as long as possible.

To achieve this goal, the current standard of care for patients with PD (PwPD) in Germany includes standardized short but regular clinical visits every 3-12 months to adjust the treatment according to disease progression. It is, however, a challenge to obtain a comprehensive picture of a patient’s disease and symptom state during the short time window of consultation since the nature of PD is highly individualized and varying in symptom severity and dependent on multiple factors such as arousal, daytime, medication effects, or diet among others [

19,

20,

21]. Thus, current medical guidelines suggest a regular monitoring of motor- and non-motor symptoms of patients to enable personalised treatment adjustment [

22,

23].

Wearable sensor technologies, combined with artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms that translate raw data into clinically relevant insights on PD symptoms, hold significant promise in this context. While numerous algorithms have recently been developed to explore this potential [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29], there are already systems on the market that are approved as medical devices and suitable for routine clinical use [

24,

30,

31].

To address the need for continuous monitoring of PwPD, we developed a high-resolution motor state assessment algorithm using data collected from a wrist-worn IMU sensor which is transformed by a fully convolutional neural network [

32,

33]. Algorithmically transformed data are shown as a continuous motor state graph in a symptom severity scale called PD9

TM including information about the motor state (dyskinesia, ON, OFF/bradykinesia; and their severity). PD9

TM is based on a combination of the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson Disease Severity Scale (MDS-UPDRS) [

34] global bradykinesia item and the modified Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (mAIMS) upper limb dyskinesia item [

35]. The continuous and long-term monitoring of the motor state gives insights into the varying motor states of PwPDs per minute throughout the day [

36], which is a prerequisite, to enable optimized treatment adjustment (unpublished results).

The aim of this study is to understand if our continuous monitoring and machine learning techniques can capture motor fluctuations of PwPDs treated with LD and identify ways of improving treatment adjustments.

2. Materials and Methods

Ethical Vote and Patient Consent

The ethical board of the Technical University of Munich (TUM) approved this clinical investigation (No. 234/16S) on June 30, 2016. With their written consent, all patients included in the study agreed to the recording and analysis of their anonymized data. The authors confirm that all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study Cohort

The entire available patient cohort consisted of 95 patients diagnosed with PD according to UK Brain Bank criteria [

20]. There were 60,712 minutes of algorithmic motor symptom data available. For this investigation, 67 patients with at least one full LD cycle were included, leading to a study cohort with 55,482 minutes of algorithmic motor symptom data.

Algorithm

The PD9TM algorithm is a proprietary algorithm which is part of the software as a medical device (SaMD) called Neptune™ (Orbit Health GmbH, Munich, Germany). Neptune is a CE-marked medical device under the current European medical device regulation (Regulation (EU) 2017/745). Its algorithm enables continuous monitoring of motor symptoms and treatment responses of PwPD. This continuous information is intended to support healthcare professionals in treatment adjustment and personalization.

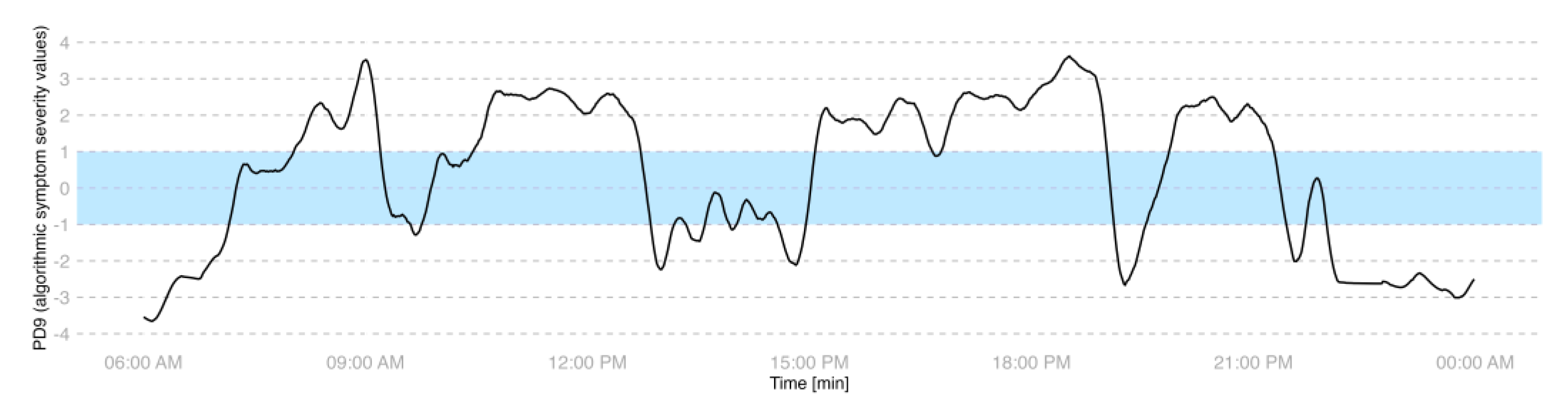

The PD9

TM algorithm is a deep learning model that converts raw accelerometer and gyroscope data from an IMU sensor into minute-by-minute values on a scale known as PD9

TM. This scale continuously measures Parkinson’s symptom severity, ranging from -4 to +4. Values from -1 to -4 represent increasing levels of bradykinesia/OFF states, while values from +1 to +4 indicate increasing severity of dyskinesia. The ON state is represented by the range from -1 to +1 (excluding +1 and -1). By integrating bradykinesia/OFF, ON, and dyskinesia into a single scale, PD9

TM enables comprehensive visualization of motor states, detection of subtle changes in motor function, and identification of motor fluctuations (see

Figure 1).

The algorithm is built on a fully convolutional network (FCN) architecture, trained using data collected from individuals with Parkinson’s disease who wore a smartwatch during daily activities. Simultaneously, a movement disorder expert observed the patients in both free-living and hospital environments, rating their motor symptoms every minute using items from validated scales, namely MDS-UPDRS item III.14 and item 5 of mAIMS. This experimental setup [

10] generated a comprehensive, clinically labeled dataset, enabling the supervised training of the FCN model and ultimately resulting in the development of the PD9

TM algorithm. Detailed descriptions of the algorithm, training, and validation have been published previously [

2].

Statistics

Levodopa Cycles

To assess single LD cycles, algorithmic motor symptom data windows starting from about 20 minutes before time of medication (t=0) intake until 90 minutes after medication intake were extracted. This allowed the assessment of the motor state at time of medication intake and the motor symptom response to medication intake.

For this analysis, only complete data windows were utilized.

Motor State at Time of Medication Intake

From the LD cycles, the motor states (ON, OFF, DYS) at time of medication intake were deduced using the value of the PD9TM at t=0 as follows:

Motor state is classified as

OFF if PD9TM ≤ -1

ON if -1 < PD9TM < +1

DYS if PD9TM ≥ 1

Motor symptom response to medication was analyzed using descriptive statistics, including boxplots, as well as the mean and standard error of the mean at 5-minute intervals after medication intake. This analysis was conducted across all medication cycles and separately based on the patient’s motor state at the time of intake.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Data Collected

Data from 67 patients (30 females and 37 males) included in the clinical study are represented here with clinical characteristics described in

Table 1.

A total of 55,482 minutes of algorithm-transformed motor state data was analyzed from patients having at least one full LD cycle. On average, 828±1364 minutes of data per patient were collected (minimum: 152 minutes, maximum: 5,907 minutes).

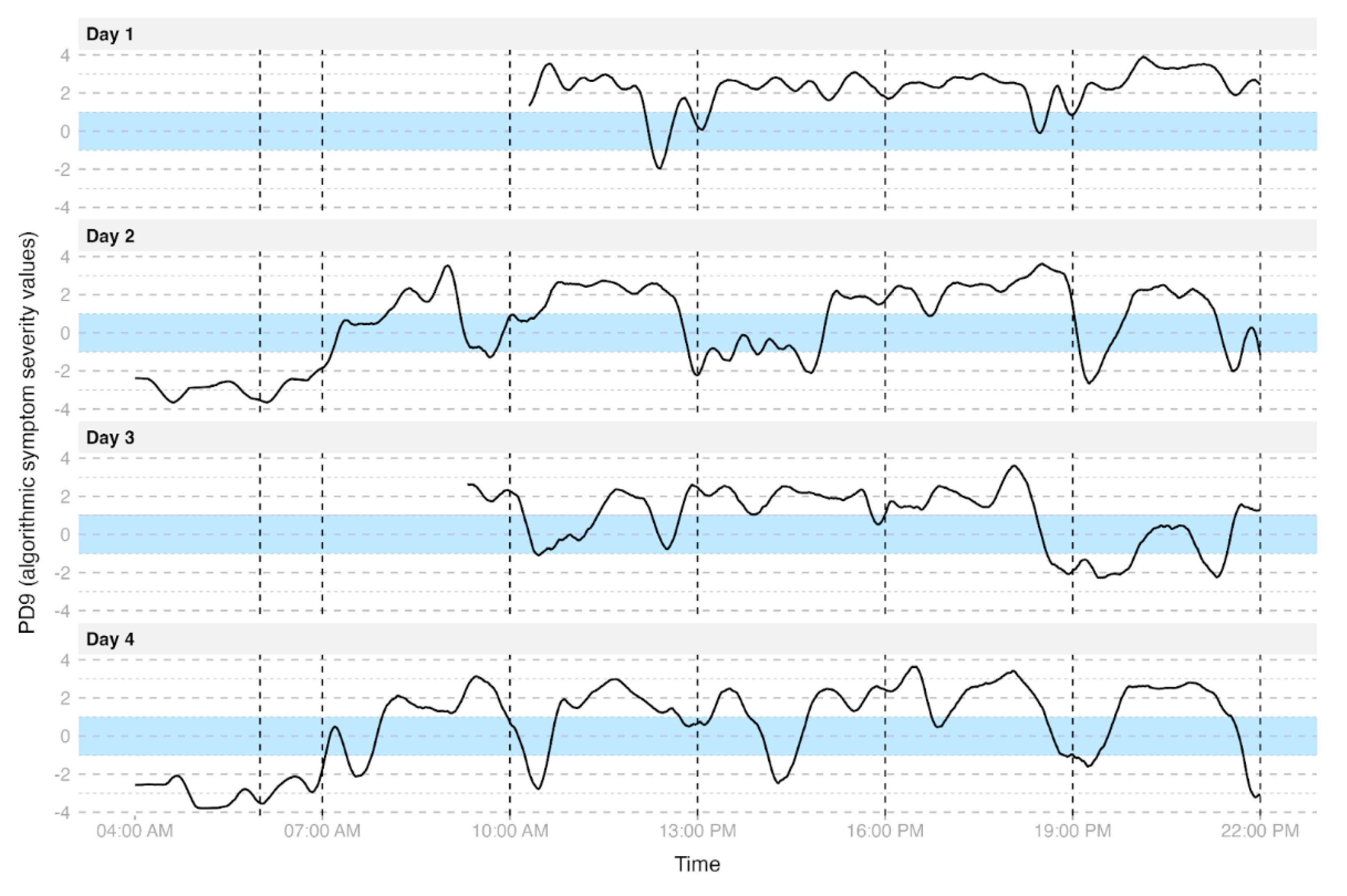

3.2. Visualisation of Motor Symptom Severity

Figure 2 provides insights from four continuous days of motor state data collected from a 64-year-old female patient diagnosed with PD 12 years prior. The patient presented symptoms including morning akinesia, sudden ON/OFF fluctuations, and wearing-off episodes. The graph displays the PD9

TM rating for each minute on a continuous scale from -4 to +4 (detailed in Materials and Methods). In this example, daily curves illustrate motor state fluctuations over the course of each day. After the initial morning medication intake (indicated by dashed lines), the patient transitions from an OFF state (characterized by morning akinesia) to an ON state, eventually reaching a dyskinetic phase. Throughout the day, abrupt motor state shifts from dyskinesia back to the OFF state are evident, notably around 10:00 and 19:00. This motor state graph effectively reflects the morning akinesia, as well as wearing-off and sudden ON/OFF fluctuations, which is also in agreement with what is observed and reported by the treating physician.

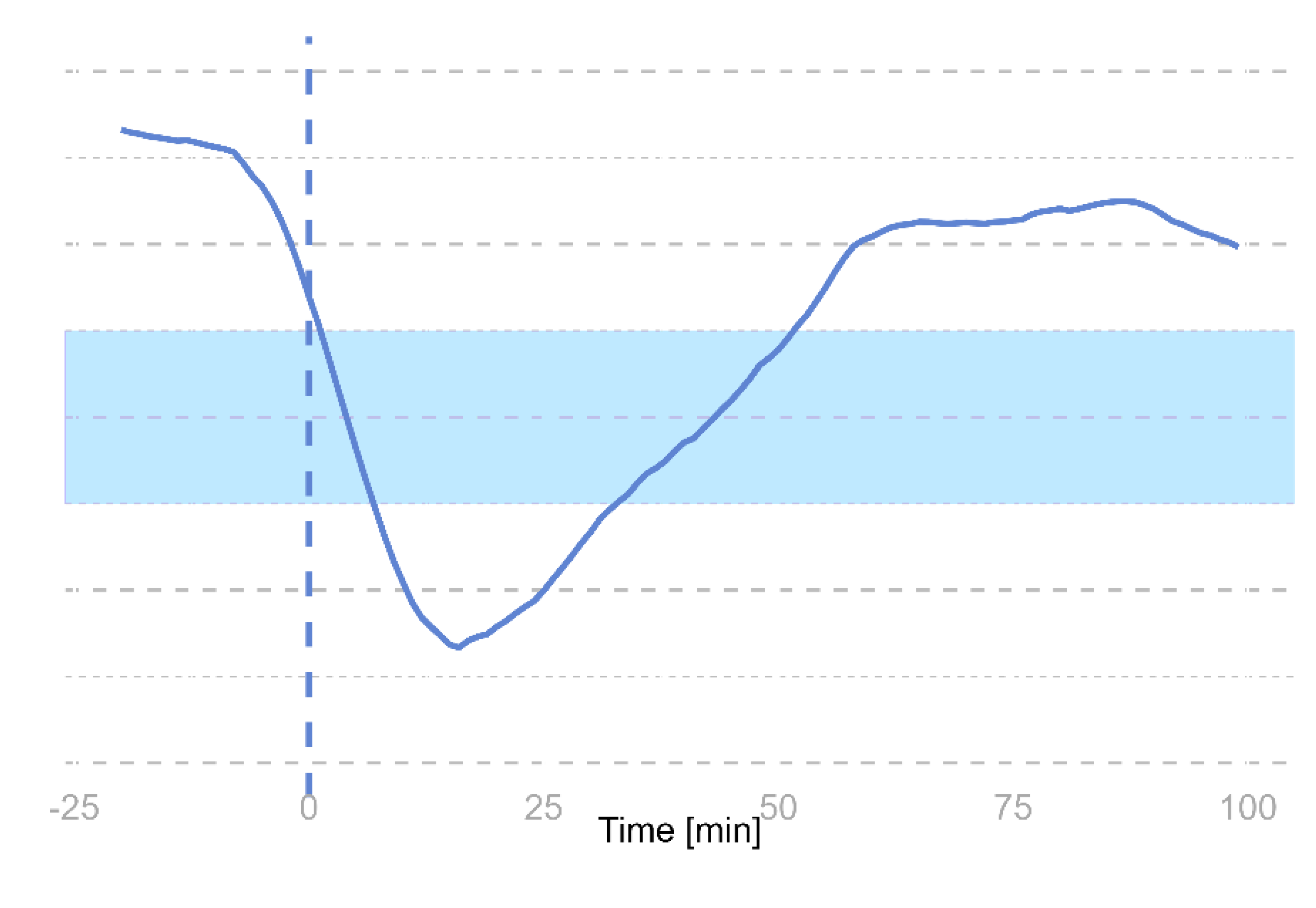

3.3. Identification of Single L-DOPA Cycles

In the daily motor state patterns of the patient shown in

Figure 2, an observable effect of LD intake on motor state is evident. A magnified view of a single medication effect on Day 2 is presented in

Figure 3. After experiencing a wearing-off period, the patient takes a new dose of Levodopa. Initially, the motor state curve shows a continuous decline into the OFF state followed by a shift towards the ON state approximately 20 minutes post-medication, reflecting the onset of the LD action. The motor state then stabilizes in a mildly dyskinetic state, further illustrating the temporal effects of LD on motor state regulation.

218 L-DOPA cycles are extracted and analyzed from the available motor state and medication intake times data as described in Materials and Methods. Tracking the motor states at the time of Levodopa intake for all patients in the study revealed an intriguing finding: Levodopa was administered predominantly in the OFF state but also during the ON and dyskinetic states. Although the majority of Levodopa doses were administered during the OFF state, nearly a quarter of administrations occurred during the dyskinetic state (see

Table 2).

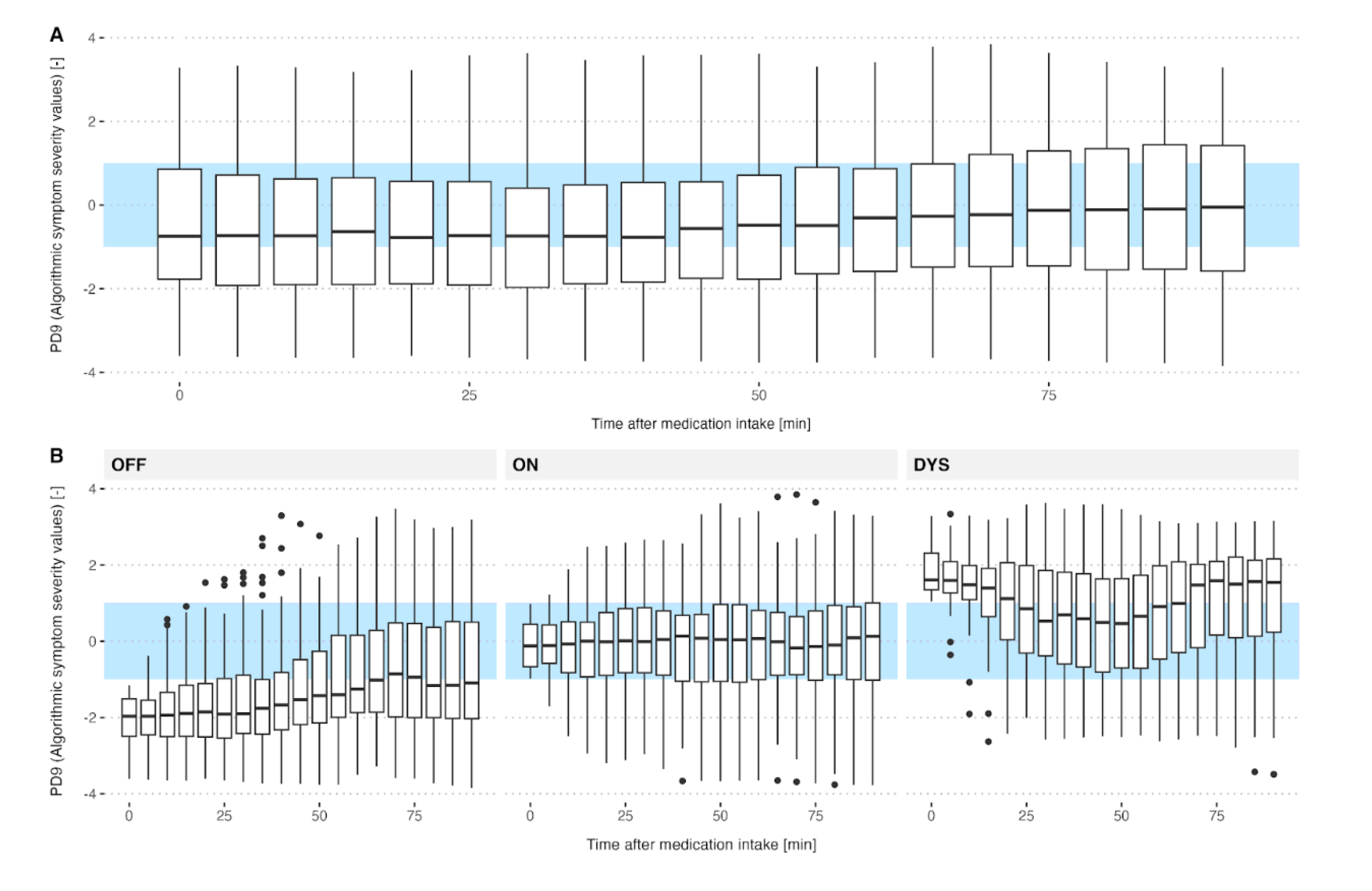

3.3. Motor States as an Effect of Levodopa Cycle

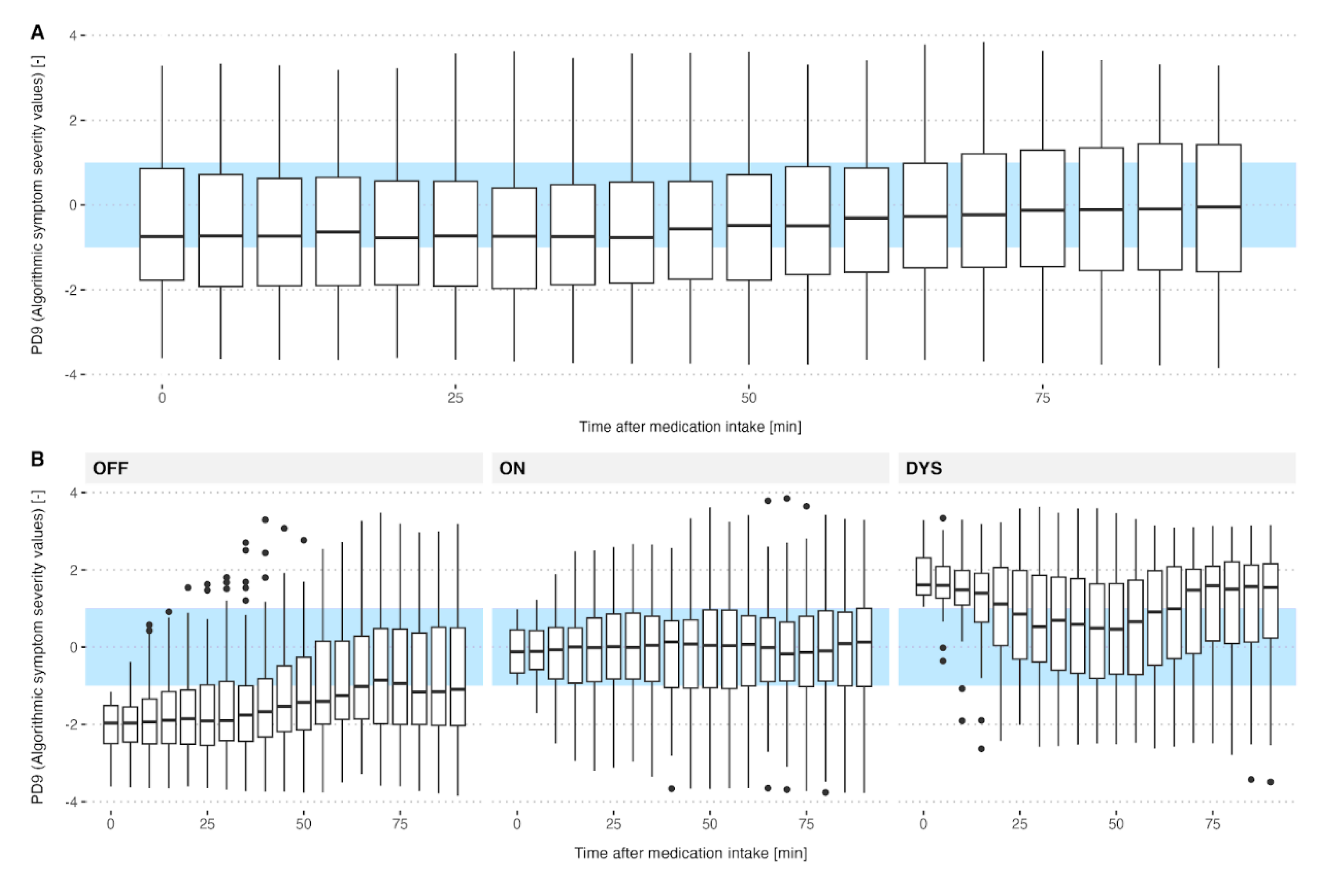

To assess how motor state at the time of LD administration influences subsequent motor response, we analyzed symptom severity scores at 5-minute intervals over a 100-minute post-administration period.

Our findings (

Figure 4) revealed distinct response patterns based on the initial motor state. When Levodopa was taken in the ON state, motor symptom severity remained relatively stable. In contrast, doses taken during the dyskinetic state were marked by an initial symptom reduction over 40–50 minutes (from ~1.5 to 0.75), followed by a return to baseline dyskinetic severity.

The most pronounced changes were observed when LD was administered in the OFF state, with symptom severity decreasing from -2 to -1 over 70 minutes.

Normalization of the curves from

Figure 4 reveals that LD intake during the OFF state has the greatest impact on reducing symptom severity (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The presented results provide evidence supporting the use of AI-powered continuous motor symptom monitoring via wearable sensors to individualize Levodopa (LD) therapy in Parkinson’s disease (PD). Using the PD9™ algorithm, which processes inertial data from a wrist-worn sensor, we analyzed 218 LD cycles across 67 patients and demonstrated that individual treatment responses can be monitored effectively.

LD intake during the OFF state resulted in the most significant symptom improvement as expected. However, this benefit also implies that the medication was taken too late, after motor deterioration had already occurred. As the clinical goal is to prevent OFF states and maintain stable motor function in the ON state, such patterns indicate suboptimal medication timing. Conversely, LD intake during the ON state led to minimal change in symptom severity, suggesting successful symptom control. However, nearly one-quarter of LD doses were taken during dyskinetic states, raising concern for potential overdosing or overly aggressive titration. These findings underscore the importance of individual, motor-state-informed dosing and highlight the limitations of fixed, empirically set schedules [

37,

38,

39,

40].

Our results are consistent with a growing body of research demonstrating the clinical potential of wearable sensor systems for PD monitoring. Devices such as the Personal KinetiGraph (PKG

®), STAT-ON™, and PDMonitor

® provide continuous, objective symptom tracking, enabling identification of OFF periods, dyskinesias, and treatment response patterns [

41,

42,

43,

44]. PKG use in routine care has led to treatment changes in up to one-third of clinic visits and improved symptom control [

43]. STAT-ON has shown ON/OFF state classification sensitivity and specificity exceeding 90%, outperforming subjective diaries in sensitivity and agreement with clinical assessments [

44]. These findings support the clinical impact of wearable-guided symptom awareness and treatment adjustments.

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have improved the interpretation of wearable raw motion data significantly. Machine learning models such as support vector machines, convolutional neural networks, and other deep learning approaches have been applied to enable classification of PD motor states and predict treatment responses [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Studies using AI-driven scales have shown strong correlation with clinical assessments and enabled real-time monitoring of therapeutic windows [

41].

Importantly, several proof-of-concept systems have demonstrated the feasibility of algorithmic LD dose [

45,

46] or DBS settings [

47] optimization. Sensor-based dosing systems have used wearable data and pharmacokinetic modeling to simulate and recommend personalized schedules, achieving close agreement with expert clinician decisions [

45]. Reinforcement learning approaches have also been applied to develop optimized medication regimens [

48,

49]. While still emerging, these AI-based frameworks suggest a path toward semi-automated or closed-loop PD management.

The PD9™ algorithm utilized in this study contributes to this evolving landscape by providing continuous, minute-by-minute assessments of motor state severity on a unified scale. This high temporal resolution allows for precise characterization of symptom patterns and LD effects in naturalistic settings. Our findings emphasize the variability in LD response between individuals and across motor states, reinforcing the need for adaptive treatment paradigms.

This study has several limitations. The design was observational, without real-time dose adjustments based on sensor feedback. External confounding factors such as diet, sleep, or stress were not explicitly accounted for. Additionally, while the PD9

TM algorithm has been validated against clinical rating scales [

32,

33], broader comparative studies with other systems and in larger populations are warranted.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the critical role of continuous, algorithm-driven monitoring in addressing the challenges of individualized PD care. The PD9™ algorithm, through its ability to capture motor state fluctuations in real-time, provides actionable insights into the impact of Levodopa administration on symptom severity. Our findings revealed the necessity of optimizing the timing of medication intake on an individual level to maximize sustained symptom relief. They further suggest that motor-state-informed timing and dosage adjustments could enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing side effects. This approach not only supports more personalized treatment adjustments but also represents a step toward closing the loop in PD management. Future work should focus on integrating these tools into clinical workflows and exploring the relationship between motor states and LD pharmacokinetics through simultaneous biomarker analysis.

Ultimately, the combination of wearable technology and machine learning holds the promise to transform care for patients with Parkinson’s Disease, enabling more effective and precise interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., FMJ.P. and U.F.; methodology, M.S.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, U.F, FMJ.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and S.K.; writing—review and editing, UM.F., MR.M, M.S and S.K; visualization, M.S.; supervision, UM.F.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

“This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Technical University Munich (code 234/16S on June 30, 2016).”

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

MS and SK are permanent employees of Orbit Health GmbH, Munich, Germany. Orbit Health developed a software as a medical device based on the algorithm investigated in this publication. FMJ.P. is a shareholder in Orbit Health GmbH. UM.F has received travel support from Orbit Health; has received honoraria for speeches from Child&Brain, Ipsen, and Abbvie.

References

- Dorsey, E.R.; Constantinescu, R.; Thompson, J.P.; Biglan, K.M.; Holloway, R.G.; Kieburtz, K.; Marshall, F.J.; Ravina, B.M.; Schifitto, G.; Siderowf, A.; et al. Projected Number of People with Parkinson Disease in the Most Populous Nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology 2007, 68, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Maserejian, L. N. Maserejian, L. Vinikoor-Imler, A. Dilley. Estimation of the 2020 Global Population of Parkinson’s Disease (PD) [abstract]. Mov Disord. 2020; 35 (suppl 1). https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/estimation-of-the-2020-global-population-of-parkinsons-disease-pd/. Accessed 16th 25. 20 July.

- Dorsey ER, Sherer T, Okun MS, et al. The Emerging Evidence of the Parkinson Pandemic. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. 2018, 8, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D. , Cui, Y., He, C., Yin, P., Bai, R., Zhu, J., Lam, J. S. T., Zhang, J., Yan, R., Zheng, X., Wu, J., Zhao, D., Wang, A., Zhou, M., & Feng, T. Projections for prevalence of Parkinson’s disease and its driving factors in 195 countries and territories to 2050: modelling study of Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2025, 388, e080952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouli, A.; Torsney, K.M.; Kuan, W.-L. Parkinson’s Disease: Etiology, Neuropathology, and Pathogenesis. In Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects; Stoker, T.B., Greenland, J.C., Eds.; Codon Publications: Brisbane (AU), 2018 ISBN 978-0-9944381-6-4.

- Armstrong MJ, Okun MS. Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Review. JAMA. 2020, 323, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrino R, Schapira AHV. Parkinson disease. Eur J Neurol. 2020, 27, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Shlomo Y, Darweesh S, Llibre-Guerra J, Marras C, San Luciano M, Tanner C. The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2024, 403, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, C. M. , & Ostrem, J. L. Parkinson’s Disease. The New England journal of medicine 2024, 391, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrino, R. , & Schapira, A. H. V. Parkinson disease. European Journal of Neurology 2020, 27, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloem, B. R. , Okun, M. S., & Klein, C. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet (London, England) 2021, 397, 2284–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, F. C. Treatment Options for Motor and Non-Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, S. , Williams, L., Morales-Briceño, H., & Fung, V. S. The initial diagnosis and management of Parkinson’s disease. Australian Journal of General Practice 2021, 50, 793–800. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, A.A.; Rosebraugh, M.; Chatamra, K.; Locke, C.; Dutta, S. Levodopa-Carbidopa Intestinal Gel Pharmacokinetics: Lower Variability than Oral Levodopa-Carbidopa. J. Park. Dis. 2017, 7, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyholm, D.; Odin, P.; Johansson, A.; Chatamra, K.; Locke, C.; Dutta, S.; Othman, A.A. Pharmacokinetics of Levodopa, Carbidopa, and 3-O-Methyldopa Following 16-Hour Jejunal Infusion of Levodopa-Carbidopa Intestinal Gel in Advanced Parkinson’s Disease Patients. AAPS J. 2012, 15, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeWitt, P.A.; Fahn, S. Levodopa Therapy for Parkinson Disease: A Look Backward and Forward. Neurology 2016, 86, S3–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsden, C.D.; Parkes, J.D. “On-off” Effects in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease on Chronic Levodopa Therapy. Lancet Lond. Engl. 1976, 1, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeso, J.A.; Grandas, F.; Vaamonde, J.; Luquin, M.R.; Artieda, J.; Lera, G.; Rodriguez, M.E.; Martinez-Lage, J.M. Motor Complications Associated with Chronic Levodopa Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurology 1989, 39, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agnieszka, W. , Paweł, P., & Małgorzata, K. How to Optimize the Effectiveness and Safety of Parkinson’s Disease Therapy? - A Systematic Review of Drugs Interactions with Food and Dietary Supplements. Current Neuropharmacology 2022, 20, 1427–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J.; Tan, E.K. Parkinson’s Disease: Etiopathogenesis and Treatment. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2020, 91, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamzadeh, F.N.; Surguchov, A. Parkinson’s Disease: Biomarkers, Treatment, and Risk Factors. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höglinger, G.; Bähr, M.; Becktepe, J.; Berg, D.; Brockmann, K.; Buhmann, C.; Ceballos-Baumann, A.; Claßen, J.; Deuschl, C.; Deuschl, G.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease (Guideline of the German Society for Neurology). Neurol. Res. Pract. 2024, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tönges, L.; Buhmann, C.; Eggers, C.; Lorenzl, S.; Warnecke, T.; Bähr, M.; Becktepe, J.; Berg, D.; Brockmann, K.; Ceballos-Baumann, A.; et al. Guideline “Parkinson’s Disease” of the German Society of Neurology (Deutsche Gesellschaft Für Neurologie): Concepts of Care. J. Neurol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ancona, S. , Faraci, F. D., Khatab, E., Fiorillo, L., Gnarra, O., Nef, T., Bassetti, C. L. A., & Bargiotas, P. Wearables in the home-based assessment of abnormal movements in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Neurology 2022, 269, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Din, S. , Kirk, C., Yarnall, A. J., Rochester, L., & Hausdorff, J. M. Body-Worn Sensors for Remote Monitoring of Parkinson’s Disease Motor Symptoms: Vision, State of the Art, and Challenges Ahead. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease 2021, 11, S35–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espay, A. J. , Bonato, P., Nahab, F. B., Maetzler, W., Dean, J. M., Klucken, J., Eskofier, B. M., Merola, A., Horak, F., Lang, A. E., Reilmann, R., Giuffrida, J., Nieuwboer, A., Horne, M., Little, M. A., Litvan, I., Simuni, T., Dorsey, E. R., Burack, M. A., … on behalf of the Movement Disorders Society Task Force on Technology. Technology in Parkinson’s disease: Challenges and opportunities: Technology in PD. Movement Disorders. 2016, 31, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulou, K.-M. , Roussaki, I., & Demestichas, K. Internet of Things Technologies and Machine Learning Methods for Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis, Monitoring and Management: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje, M. H. G. , Foffani, G., Obeso, J., & Sánchez-Ferro, Á. New Sensor and Wearable Technologies to Aid in the Diagnosis and Treatment Monitoring of Parkinson’s Disease. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 2019, 21, 111–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossig, C. , Antonini, A., Buhmann, C., Classen, J., Csoti, I., Falkenburger, B., Schwarz, M., Winkler, J., & Storch, A. Wearable sensor-based objective assessment of motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neural Transmission (Vienna, Austria: 1996) 2016, 123, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2023). NICE Guideline: Devices for remote monitoring of Parkinson’s disease. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg51/resources/devices-for-remote-monitoring-of-parkinsons-disease-pdf-1053866615749. 20 July.

- Dominey, T. , Kehagia, A. A., Gorst, T., Pearson, E., Murphy, F., King, E., & Carroll, C. Introducing the Parkinson’s KinetiGraph into Routine Parkinson’s Disease Care: A 3-Year Single Centre Experience. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease 2020, 10, 1827–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, F.M.J.; Um, T.T.; Pichler, D.C.; Goschenhofer, J.; Abedinpour, K.; Lang, M.; Endo, S.; Ceballos-Baumann, A.O.; Hirche, S.; Bischl, B.; et al. High-Resolution Motor State Detection in Parkinson’s Disease Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goschenhofer, J. , Pfister, F. M. J., Yuksel, K. A., Bischl, B., Fietzek, U., & Thomas, J. (2020). Wearable-Based Parkinson’s Disease Severity Monitoring Using Deep Learning. In U. Brefeld, E. Fromont, A. Hotho, A. Knobbe, M. Maathuis, & C. Robardet (Hrsg.), Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases (Bd. 11908, S. 400–415). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Poewe, W.; Sampaio, C.; Stern, M.B.; Dodel, R.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Scale Presentation and Clinimetric Testing Results. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 2129–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, R.D.; Glazer, W.M.; Hansen, T.E.; Berman, W.H.; Kramer, S.I. Assessment of Tardive Dyskinesia Using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1985, 173, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fietzek, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Closing the Loop mit NeptuneTM – Erste Erfahrungen mit der KI-Sensorlösung zur Erfassung des motorischen Zustandes bei Menschen mit Parkinson. Neuro aktuell 4/2024, Available online:. Available online: https://neuroaktuell.de/2024/04/22/closing-the-loop-mit-neptunetm-erste-erfahrungen-mit-der-ki-sensorloesung-zur-erfassung-des-motorischen-zustandes-bei-menschen-mit-parkinson/ (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Nyholm, D. , & Stepien, V. Levodopa fractionation in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Parkinson’s disease 2014, 4, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabreira, V. , Soares-da-Silva, P., & Massano, J. Contemporary Options for the Management of Motor Complications in Parkinson’s Disease: Updated Clinical Review. Drugs 2019, 79, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahwa, R. , Pagan, F.L., Kremens, D.E. et al. Clinical Use of On-Demand Therapies for Patients with Parkinson’s Disease and OFF Periods. Neurol Ther 2023, 12, 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacson SH, Pagan FL, Lew MF, Pahwa R. Should “on-demand” treatments for Parkinson’s disease OFF episodes be used earlier? Clin Park Relat Disord. 2022, 7, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moreau, C. , Rouaud, T., Grabli, D. et al. Overview on wearable sensors for the management of Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2023, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald JJ, Lu Z, Jareonsettasin P, Antoniades CA. Quantifying Motor Impairment in Movement Disorders. Front Neurosci. 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundgren, M. , Andréasson, M., Svenningsson, P., Noori, R. M., & Johansson, A. Does Information from the Parkinson KinetiGraph™ (PKG) Influence the Neurologist’s Treatment Decisions?-An Observational Study in Routine Clinical Care of People with Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of personalized medicine 2021, 11, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Molinero A, Samà A, Pérez-López C, Rodríguez-Martín D, Alcaine S, Mestre B, Quispe P, Giuliani B, Vainstein G, Browne P, Sweeney D, Quinlan LR, Moreno Arostegui JM, Bayes À, Lewy H, Costa A, Annicchiarico R, Counihan T, Laighin GÒ and Cabestany J. Analysis of Correlation between an Accelerometer-Based Algorithm for Detecting Parkinsonian Gait and UPDRS Subscales. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, I. , Alam, M., Bergquist, F. et al. Sensor-based algorithmic dosing suggestions for oral administration of levodopa/carbidopa microtablets for Parkinson’s disease: a first experience. J Neurol 2019, 266, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, J. , Khojandi, A., Vasudevan, R., Nahab, F. B., & Ramdhani, R. A. Improving Medication Regimen Recommendation for Parkinson’s Disease Using Sensor Technology. Sensors 2021, 21, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulliam, C. L. , Heldman, D. A., Orcutt, T. H., Mera, T. O., Giuffrida, J. P., & Vitek, J. L. Motion sensor strategies for automated optimization of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2015, 21, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. , Suescun, J., Schiess, M. C., & Jiang, X. Computational medication regimen for Parkinson’s disease using reinforcement learning. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 9313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Shuqair, J. Jimenez-Shahed and B. Ghoraani. Reinforcement Learning-Based Adaptive Classification for Medication State Monitoring in Parkinson’s Disease. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2024, 28, 6168–6179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).