1. Introduction

Since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in 2019, global awareness of infectious disease control has increased, leading to increased demand for disinfectants in medical, nursing, and daily use. This has raised concerns regarding the potential side effects of disinfectants and the environmental impact of the waste liquid after use [

1,

2]. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), international goals for the period 2016–2030, as outlined in the "2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development" adopted at the United Nations Summit in September 2015, consist of 17 goals and 169 targets aimed at creating a sustainable world [

3]. Despite the development of advanced projects in various fields to meet these goals, the increasing demand for disinfectants for infection control is a negative factor for the realization of the SDGs in terms of potential environmental impact [

1,

2]. To align with the SDG concept, it is crucial to develop disinfectants that are both cost-effective and environmentally friendly while maintaining high microbicidal efficacy without concern for environmental impact to achieve a sustainable society.

Hypochlorous acid water, also known as electrolyzed water, mainly containing hypochlorous acid (HOCl), has gained considerable attention in recent years because of its broad antimicrobial spectrum, and a high microbicidal effect in a short period [

4,

5], and eco-friendly nature [

6] compared with disinfectants used for the same purpose [

7,

8]. Electrolyzed water produced by electrolyzing a dilute sodium chloride (NaCl) solution contains several tens of mg/L of free available chlorine concentration (ACC) and exhibits a broad antimicrobial spectrum, including efficacy against the novel coronavirus. Depending on pH, electrolyzed water for disinfection, mainly containing HOCl as a sterilizing ingredient, is classified as strongly acidic, weakly acidic, slightly acidic, and neutral types. These electrolyzed waters have been used in various fields such as medical care, nursing care, food, and agriculture for sanitation and disinfection because of their high microbicidal efficacy, biosafety [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], and low running cost. Each type of electrolyzed water for disinfection offers promise as a potential infection control measure that can contribute to achieving the SDGs.

The authors have been working to expand the application of these electrolyzed waters for disinfection, especially a neutral electrolyzed water (NW) by two-stage electrolysis, in dentistry. We have reported that NW has the highest storage stability [

12]. It has been reported that NW exhibits a high bactericidal effect comparable to that of the acidic type for cleaning dental instruments [

13], impressions (intraoral molds) [

14,

15,

16], resin denture base [

17,

18,

19], and root canals [

20]. Furthermore, we have also reported that NW, unlike the acidic type, does not affect human enamel because of its higher pH than the critical pH of human enamel demineralization, i.e. hydroxyapatite dissolution (generally around pH 5.5) [

21,

22], and that the elution of the component elements of dental metals immersed in NW is the lower than that of acidic electrolyzed waters [

23]. Then, we also verified that NW is highly effective in decontaminating dentures based on the results of two clinical trials on denture cleaning [

24,

25]. The usefulness of water jet cleaning using NW for fixed dental orthodontic appliances has been reported [

26].

In actual use, the handling of electrolyzed water including NW varies depending on its intended purpose and field, such as medicine, food hygiene, and agriculture. In facilities with their own electrolyzed water generator, large quantities of fresh electrolyzed water can be used for sterilization immediately after its preparation. However, even facilities with their own generators often store a certain amount of electrolyzed water in each section of the facility, for use during home visits and for usage by patients at home. In addition, when a facility does not have a generator but purchases commercially prepared electrolyzed water for disinfection, electrolyzed water sold in a stored state is used instead of the freshly prepared electrolyzed water.

In this study, assuming both cases of direct use without dilution on the object to be treated and use after dilution to the desired concentration, long-term storage stability of standard- and high-concentration NWs was evaluated. Changes in pH, oxidation-reduction potential (ORP), and ACC during and after storage for 126 days (18 weeks, approximately 4 months) under three different conditions were monitored. Based on the results, optimal storage conditions, specifically the initial ACC, temperature, and light shielding, were determined to expand the application of NW in intraoral treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of NWs

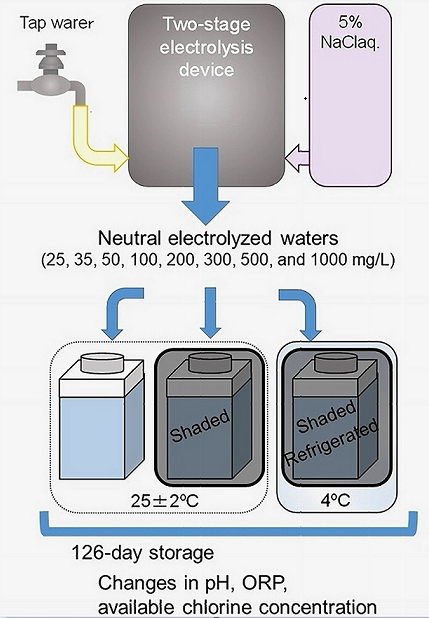

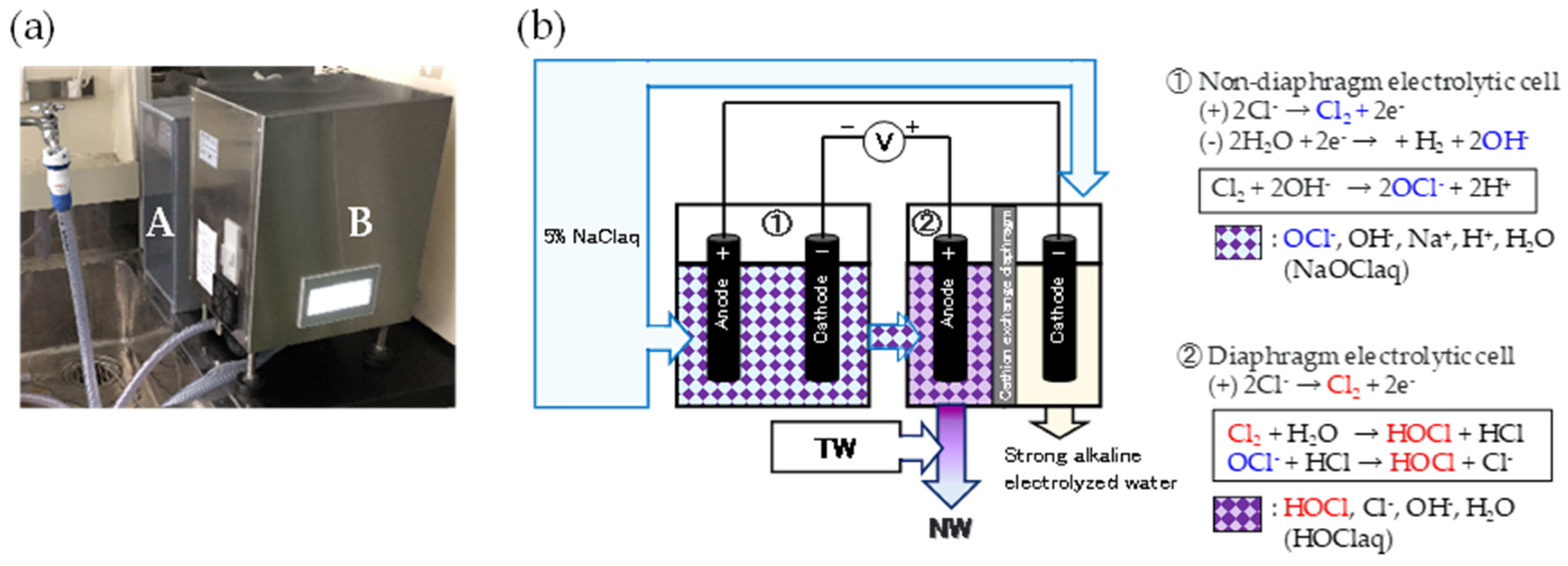

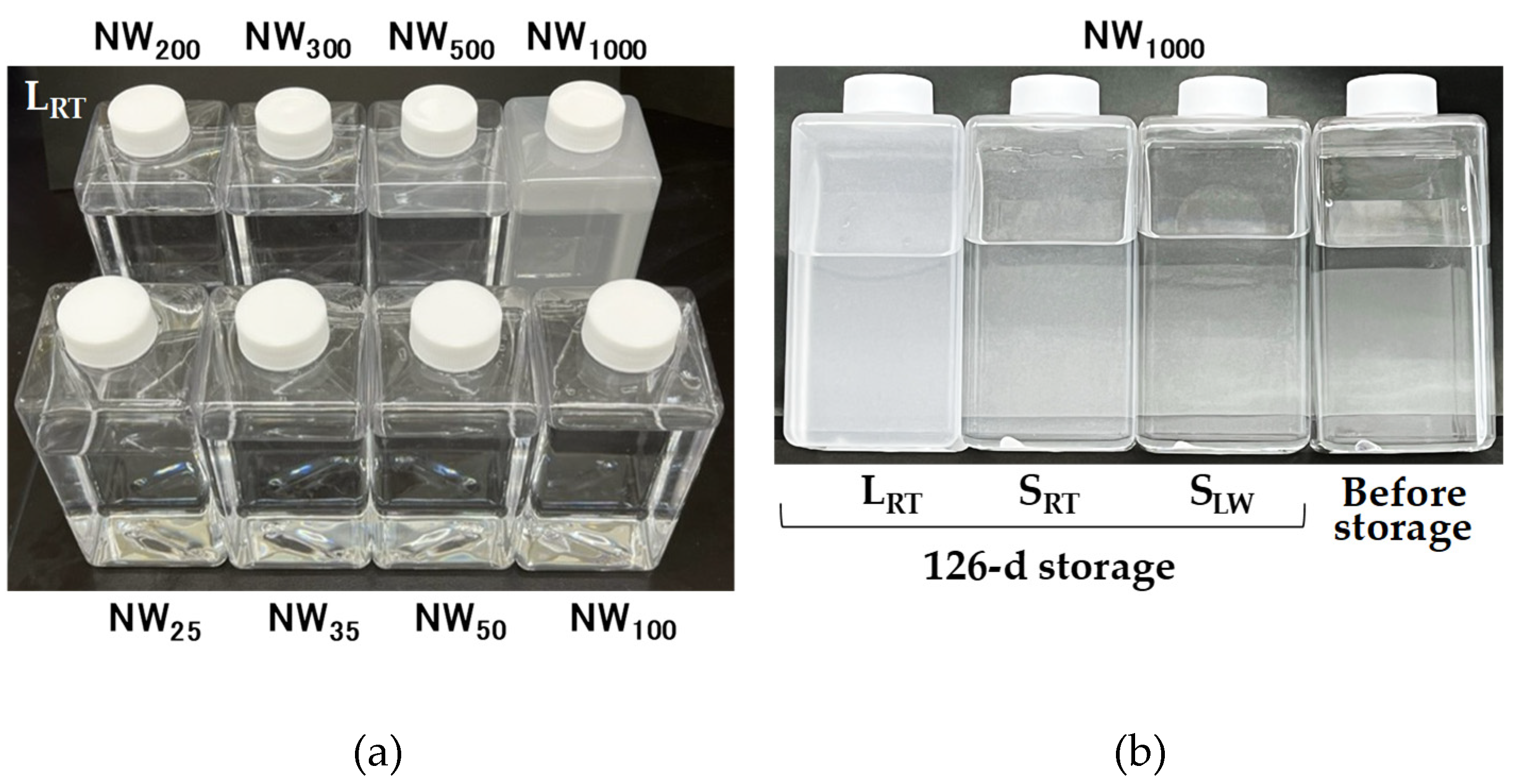

Eight test NWs were automatically prepared using tap water (TW) and a 5% NaCl aqueous solution (electrolysis auxiliary liquid) using an NW generator (Meau MS-1; Medist Sanite, Wakayama, Japan). The generator was partially modified by the manufacturer to prepare NW within the desired pH range of 6.0–7.5 and ACC of approximately 20–10000 mg/L (

Figure 1 [a]). The test NWs were obtained through two-stage electrolysis (initial diaphragm-less electrolysis followed by diaphragm electrolysis) in the generator (

Figure 1 [b]).

The properties of the test NW immediately after preparation within 1 h and after TW are listed in

Table 1.

2.2. Measurement of properties for NWs during the 126-day storage period

For each test NW, changes in pH, ORP and ACC were examined during the 126-d storage, as shown below.

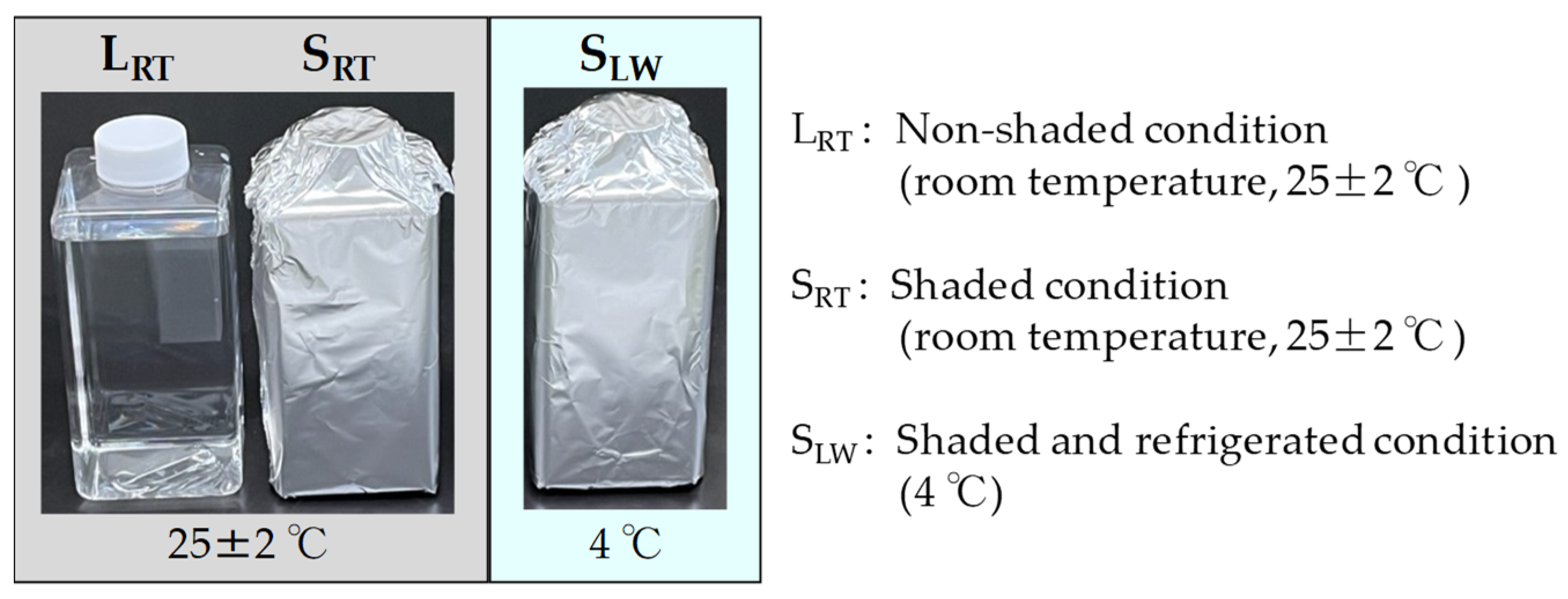

2.2.1. Storage conditions

After preparation, 500 mL of each NW was immediately transferred to a polyethyleneterephthalate (PET) container (Tetragonal Type, AS ONE, Osaka, Japan) and stored for up to 126 days (18 weeks, approximately 4 months) under one of the following storage conditions: non-shaded at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) condition (L

RT), shaded at room temperature condition (S

RT), shaded and refrigerated (4 °C) condition (S

LW) as shown in

Figure 2.

Each of the eight NW was stored in a container under three different conditions, i.e., 24 types of samples were prepared. Five samples of each type were stored, and storage stability was examined. Each container stored at room temperature (LRT/ SRT) was placed 2–2.5 m from a transparent glass window in an experimental room. The room was continuously illuminated with an LED light throughout the storage period. Each container stored at 4 °C (SLW) was placed in a refrigerator in the experimental room.

2.2.2. Measurement of properties for NWs

The pH and ORP of each NW were measured using a pH meter (PHL-20, DKK-TOA, Tokyo, Japan) connected to dedicated electrodes. ACC, which is an indicator of bactericidal activity, was measured using a chlorine comparator (Chlorine Comparator for Free Chlorine in Water; Sibata Scientific Technology, Saitama, Japan) and N, N-diethyl-p-phenylenediamine (Sibata Scientific Technology, Saitama, Japan). The change rates of pH, ORP, and ACC were calculated from these results using the following equations:

where V

126d is the value of NW after the 126-day storage period and V

0d is the initial value before storage.

All measurements were repeated five times for each sample type (n = 5).

2.3. Observation of PET container after 126 days

The appearance of each PET container storing NWs under the three different conditions was observed with the naked eye after 126 days.

2.4. Bactericidal effect test for NWs stored for 126 days

After the 126-day storage period, the bactericidal effect of each test NW was examined, as shown below.

The presence of Streptococcus mutans (NBRC13955, S. mutans), a major causative bacterium of dental caries, was analyzed to examine the bactericidal effects of the test NWs. A bacterial suspension was obtained from single colony isolation on an agar plate and inoculated in overnight broth cultures at 37 °C. S. mutans was cultured in brain-heart infusion broth (BHI; Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) under aerobic conditions. The bacteria were collected, washed twice with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; AS ONE, Osaka, Japan), centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 min, and then resuspended in fresh sterile PBS to prepare approximately 1.6×107 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL.

Each test NW (9.0 mL) was added to 1.0 mL of the bacterial suspension by repetitive pipetting using a sterile glass pipette and vortexed for 3 min using a vortex mixer (Thermolyne Maxi Mix II Vortexer, Barnstead Thermolyne, Dubuque, IA, USA) to examine its bactericidal effect. After treatment, 0.1 or 1.0 mL of each test NW mixed with the bacterial suspension was appropriately diluted with fresh sterile PBS, with repetitive pipetting using a sterile glass pipette. The diluted solution was then added to each agar culture medium and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The BHI agar medium (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used. After incubation, the total number of surviving bacteria in the test NW was calculated from the CFU in the agar medium. The bacterial removal rates were calculated using the following equation:

where N

surviving is the number of surviving bacteria and N

initial is the initial number of bacteria in contact with test NW (1.6×10

7).

Bactericidal tests were repeated five times for each sample type (n = 5).

2.5. Statistical analysis

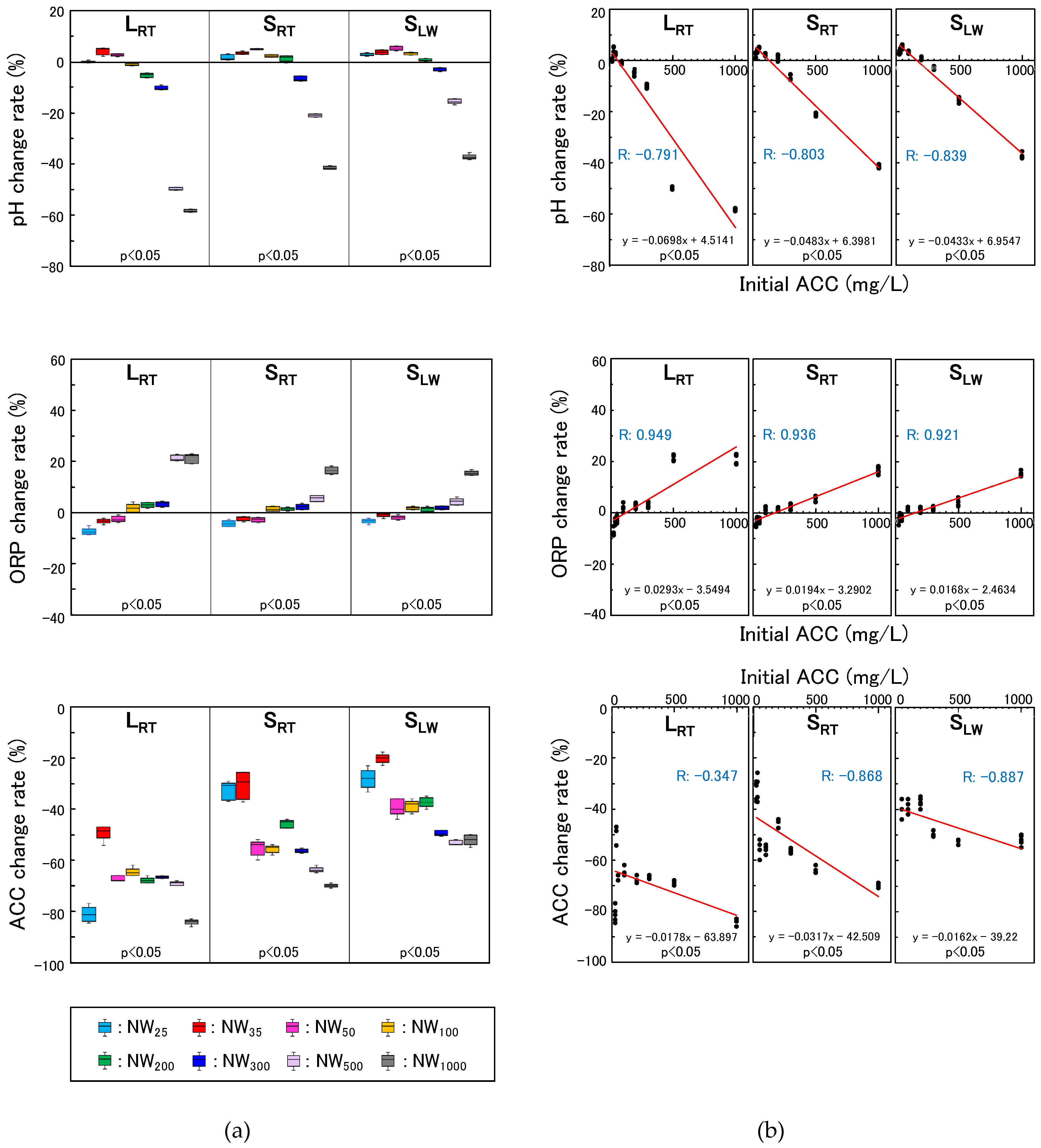

To analyze the three properties, pH, ORP, and ACC, of each test NW stored for 126 days under different conditions, the normality of data distribution for each property was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

In addition, the rate of change in pH, ORP, and ACC after the 126-day storage period was analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare the eight initial ACCs of NWs for each storage condition after testing for normality, as previously described. Subsequently, Spearman's correlation analysis was conducted to examine the correlation between initial ACC and the rate of change in each property under different storage conditions.

All statistical analyses were performed using EZR statistical software (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

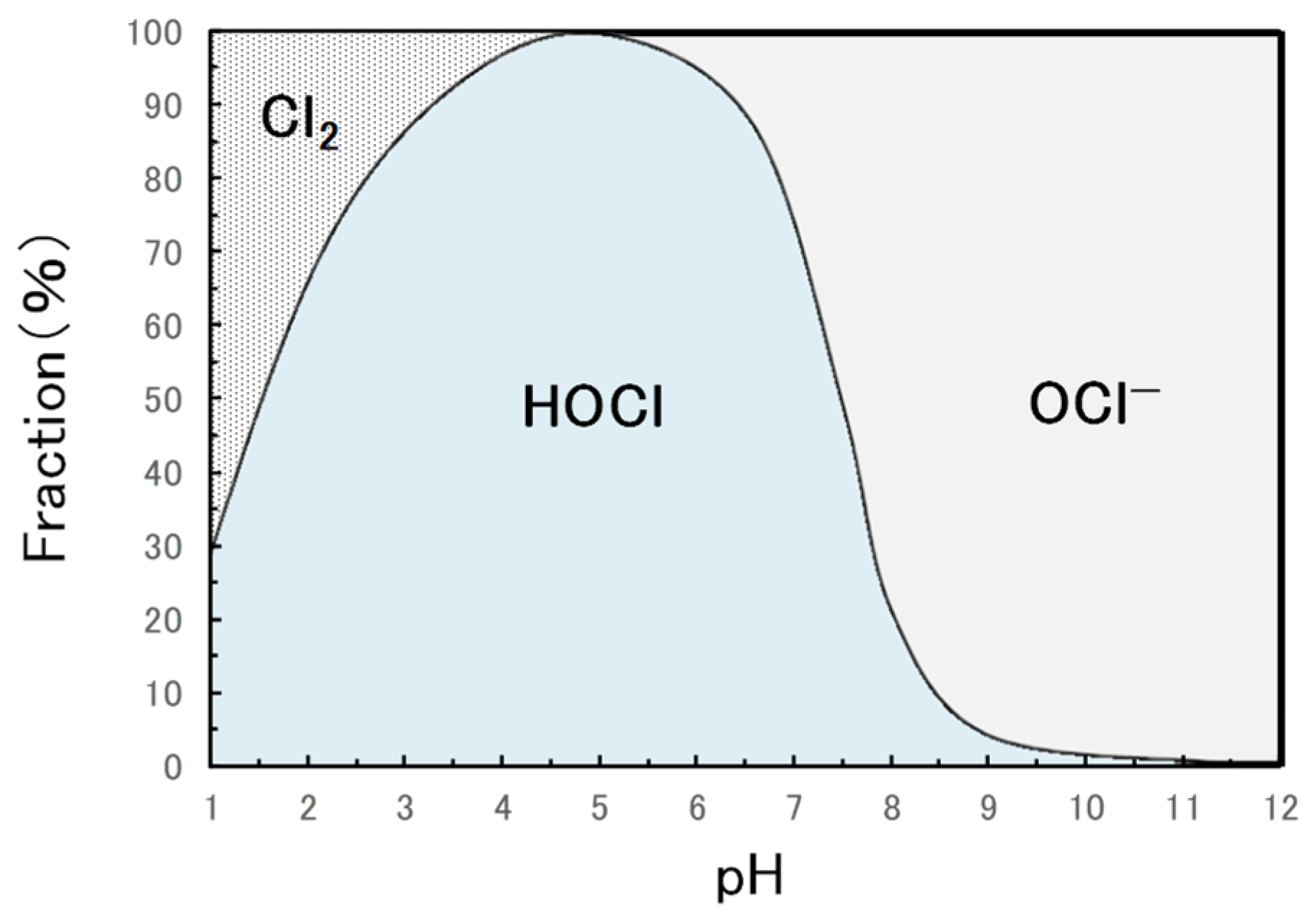

In electrolyzed water for disinfection, the fraction of free available chlorine (Cl

2, HOCl, and OCl

−) as a sterilization component varies depending on the pH (Figure A) [

27,

28]. The free available chlorine in NW is mainly HOCl and secondarily hypochlorite ion (OCl

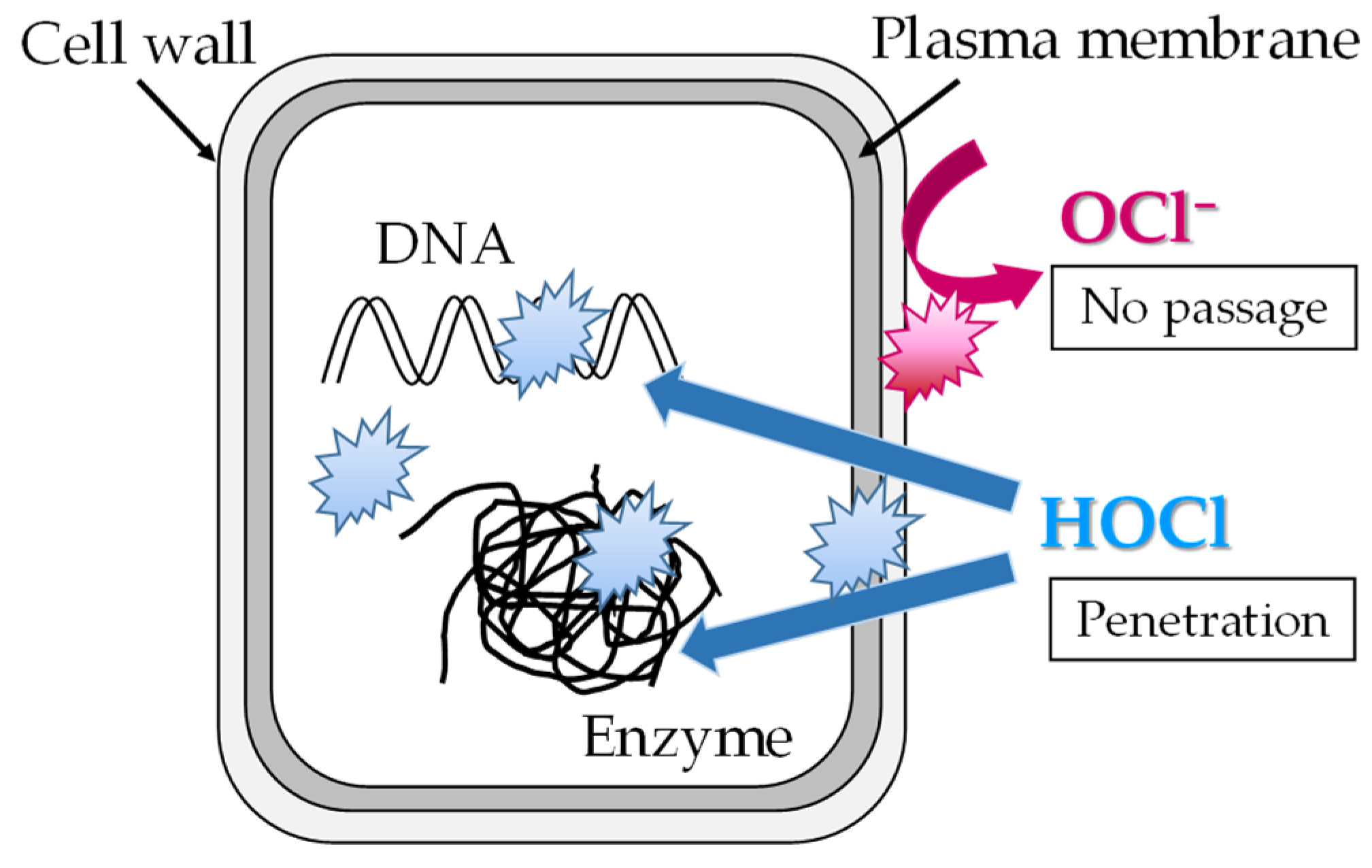

−). After penetrating the cell wall and biological membrane and entering the inside of the bacterial cells, HOCl has the potential to permeate membranes into the interior of microorganisms and has an oxidizing impact on vital tissues (Figure B) [

28,

29]. In contrast, OCl

− does not have membrane permeability and only oxidizes the cell membrane (plasma membrane) and cell periphery (Figure B) [

28,

29]. Therefore, HOCl has a higher bactericidal effect at lower concentrations than OCl

−. The dissociation constant (Ka) of HOCl at 25 °C is 2.95 × 10

-8 mol/L (pKa: 7.53), and at pH 7.5, the ratio of HOCl and OCl

− is approximately 1:1 [

28,

29]. Consequently, HOCl concentration decreases in alkaline environments, reducing its bactericidal efficacy. To maximize antimicrobial activity for oral applications, the pH of NW should be less than 7.5. At a pH lower than 7.5, the bactericidal efficacy of HOCl increases. However, excessive acidity can lead to chlorine gas formation, causing odor and property deterioration. Acidic environment increases the risk of tooth tissue demineralization and corrosion of metal restorations [

21,

23]. To achieve a high microbicidal effect without acid influence on tooth and metal restorations for intraoral treatment, referring to the critical pH of human enamel and dentin (5.5 and 6.0–6.2, respectively), NW should be prepared and used with a pH in the range of 6.2–7.5 for standard-concentration type without dilution and in the range of 5.5–7.5 for high-concentration type with dilution.

Regarding ACC, we considered that NW should be at least 15 mg/L at the time of use to obtain a bacterial removal rate of 99.999% or higher, based on the results of previous studies that used similar test methods using the same bacteria [

30].

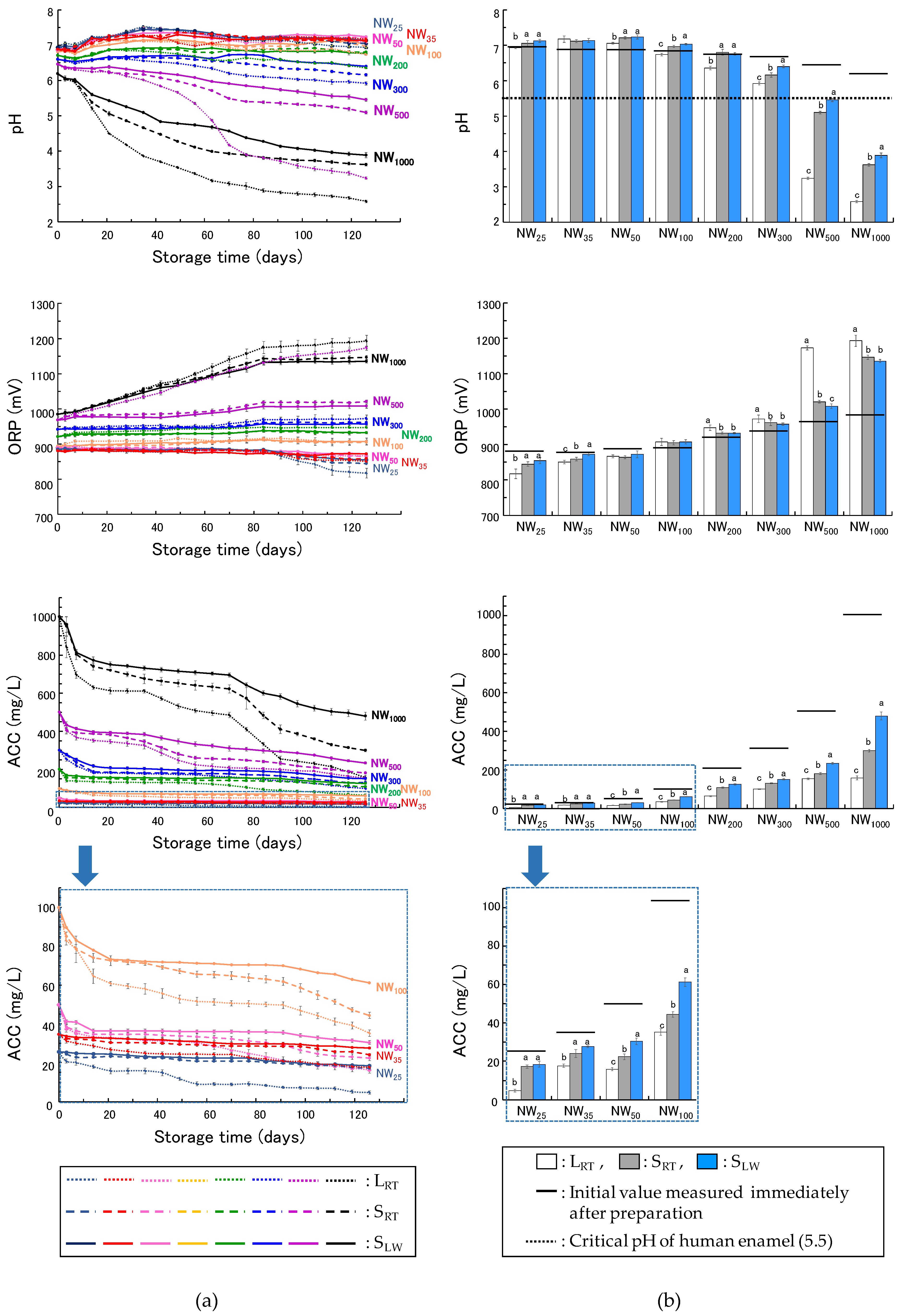

The standard-concentration NWs (NW25, NW35, and NW50) maintained a neutral pH range (6.9–7.3) during the 126-day storage period. This result indicates that the standard-concentration NWs were mainly composed of HOCl after storage. NW25 should be stored in a shaded container or in a dark place, as the ACC decreased to 5 mg/L in non-shaded at room temperature storage (LRT), leading to a decrease in its bactericidal efficacy. NW35 and NW50 showed high bactericidal effects even after 126 days during storage in non-shaded conditions at room temperature (LRT); however, shaded storage (SRT, SLW) was superior to LRT because of slower ACC reduction. In this study, the UV light reaching indoors through the transparent window glass may have affected the ACC during storage under LRT because it was not completely blocked from outdoor sunlight. LRT is not an appropriate condition if longer storage is desired, as ACC decreases faster than in shaded storage (SRT, SLW). Because these NWs stored in shaded and refrigerated containers resulted in the least reduction in ACC, shaded and refrigerated storage (SLW) is highly recommended for NW35 and NW50. The standard-concentration NWs are typically used without dilution. Because NW50 has an ACC equivalent to that of NW25 at a 2-fold dilution at the time of preparation, it is anticipated that some cases will be used with dilution. However, if the same dilution ratio was used after 126 days of storage, the ACC of NW50 would be 8 mg/L under LRT, 11 mg/L under SRT, and 15 mg/L under SLW, which may decrease its bactericidal efficacy. To maintain high microbicidal effectiveness, it is advisable to dilute stored standard-concentration NWs appropriately, considering the reduction in ACC during storage.

High-concentration NWs with an ACC of 300 mg/L or lower (NW

100, NW

200, and NW

300) have a pH of 6.6–6.8 at the time of preparation and are used in the neutral range by dilution with tap water at the time of use. After 126 days of storage, NW

300 stored under L

RT had a pH of 5.9 ± 0.0, whereas the other NWs ranged from slightly acidic to neutral, with a pH range of 6.2–7.0, fluctuating by approximately 0.5. The pH values of these NWs exceeded the critical pH of human enamel (5.5) during storage, suggesting that their use in the oral cavity does not affect human enamel, regardless of the storage conditions [

21]. Assuming that these NWs were diluted to 25–100 mg/L, no dilution or a maximum of 4-fold dilution (25 mg/L) was made in NW

100 before storage. Our results indicate that NW

100 stored for 126 days under L

RT had an ACC of 35 mg/L, demonstrating high bactericidal efficacy. In the case of the use of 4-fold dilution (25 mg/L at fresh before storage), if the same dilution is made after storage, the ACC will be less than 15 mg/L after more than 28 days of storage under L

RT or 98 days under S

RT, which may affect the bactericidal effect. If stored in S

LW, the negative effect of storage on bactericidal activity can be minimized because an ACC of more than 15 mg/L is maintained even if NW

100 is diluted 4-fold (25 mg/L at fresh). Therefore, this is the preferred storage method. However, if refrigeration is not possible and the sample can only be stored at room temperature, it should be less than 2-fold (> 50 mg/L at fresh) under L

RT and 2.5-fold (> 40 mg/L at fresh) under S

RT for NW

100 for use of the same dilution rate during storage at room temperature or should not be diluted. Similarly, in the case of NW

200 after the 126-day storage period at the same dilution rate as before storage, if shaded and refrigerated storage is not possible, the dilution rate should be set to no more than 4-fold (> 50 mg/L at fresh) under L

RT and no more than 7-fold (> 29 mg/L at fresh) under S

RT. After 126 days of storage, NW

300 showed an approximately 50% decrease in ACC, even under shaded and refrigerated condition, S

LW. If the same dilution rate is used during storage for 126 days, the dilution rate should be set to less than 6.5-fold (> 46 mg/L at fresh) under L

RT, less than 8.5-fold (> 35 mg/L at fresh) under S

RT, and less than 10-fold (> 30 mg/L at fresh) under S

LW.

The high-concentration NWs with an ACC of 500 mg/L or higher (NW

500 and NW

1000) have a pH of 6.2–6.5 at the time of preparation and are used in the neutral range by dilution with tap water at the time of use. All the measured properties of these NWs changed significantly with storage time, and even after shaded and refrigerated storage (S

LW), the NWs lost more than 50% of their free chlorine concentration, making them less stable for storage than the other NWs. In addition, room temperature storage (L

RT, S

RT) of NW

500 resulted in a pH below 5.5 after 14 days of storage and 3.2–5.1 at the end of the 126-day storage period. In S

LW, the pH was only 5.5 after 119 days of storage and less than 5.5 after 126 days. NW

500 stored in a shaded and refrigerated container could be used in the oral cavity for up to 3 months by dilution at a rate of less than 16-fold (>31 mg/L at fresh). However, for NW

1000, even in S

LW, the pH falls below 5.5 after 14 days and below 4 at the end of storage, suggesting that acid effects on human enamel may occur for NW

1000 stored for more than 14 days. In addition, NW

1000 is considered inappropriate for long-term storage because of its noticeable and unpleasant chlorine odor, which is slight and unnoticeable at standard concentrations. Furthermore, the PET containers storing NW

1000 at room temperature showed slight whitening if shaded or lost transparency and turned cloudy white inside if not shaded. PET can be degraded by physical, chemical, or biological methods. Under certain acidic conditions, it can be degraded to ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid via hydrolysis [

31,

32]. Hirota et al. (2020) [

31] have reported that immersion tests of biodegradable PET at pH 3.0 to 10.5 for up to 4 weeks at 80 °C revealed significant differences in decomposition behavior in alkaline and acidic solutions, with a significant decrease in molecular weight observed in dilute sulfuric acid (pH 3.0). In the PET containers used to store the test NWs in our study, the interaction of prolonged contact with high concentrations of free available chlorine, increased acidity of NW

1000 during storage (pH < 3 in the 126-day storage period under L

RT), and lack of light shielding may have exceeded the limits of the chemical and weather resistance of PET. The change in appearance inside the PET container is inferred to be mainly due to acid hydrolysis on the PET surface caused by contact with the remarkably increased acidity of NW

1000 during storage.

HOCl molecules, which are the main microbicidal components of electrolyzed water, are not chemically stable. We previously reported the storage stability of three different types (strongly acidic, slightly acidic, and neutral) of electrolyzed water at standard concentrations [

12]. Even the neutral type (NW), which had the highest storage stability, was affected by differences in storage environment, causing a significant decrease in its properties when stored at room temperature without light shielding when the bottle was open [

12]. As previously reported [

12], test NWs from the same two-stage electrolysis were used in this study. We standardized the sealing of all storage containers for eight NWs with different ACCs containing standard concentrations and examined the effects of the initial ACC, light shielding, and temperature during storage on long-term storage stability. Consistent with previous findings [

12,

33,

34], our findings confirmed the effectiveness of shaded and refrigerated storage conditions. As previously mentioned, the pH and ACC of NW during actual use change in a complex manner depending on the initial ACC at the time of preparation and the storage conditions. High-concentration NWs are particularly susceptible to a significant reduction in ACC during storage. Consequently, an inappropriately diluted NW (i.e., diluted with insufficiently effective ACC) may be used for disinfection of the oral cavity, potentially resulting in insufficient microbicidal activity. Therefore, when using stored high-concentration NW, it is necessary to measure ACC and dilute it appropriately before use.

Neutral electrolyzed water containing HOCl as the main ingredient has a pH equivalent to that of the oral cavity at rest, which holds promise for potential applications in dental practice. By accurately assessing bactericidal components based on properties such as pH and ACC at the time of use and maximizing the effectiveness of NW, it is possible to replace traditional disinfectants and contribute to SDG's by preventing the overuse of chemical substances. Future research will focus on evaluating the biological safety of NWs and gels containing NW [

35] for intraoral treatment using cytotoxicity tests on oral mucosa cells. Additionally, we plan to specify the optimal usage conditions (concentration, form, treatment and time) of NWs for each intraoral procedure and further evaluate their efficacy and biocompatibility through clinical trials.