Submitted:

03 September 2024

Posted:

04 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Subjects and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Ethical Considerations

2.2. Measurement Tools

a) The Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS)

b) Dimensions of Anger Reactions-5 (DAR-5)

c) The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS)

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Denckla, C. A., Cicchetti, D., Kubzansky, L. D., Seedat, S., Teicher, M. H., Williams, D. R., & Koenen, K. C. (2020). Psychological resilience: An update on definitions, a critical appraisal, and research recommendations. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1822064.

- Ungar, M., & Theron, L. (2020). Resilience and mental health: How multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(5), 441-448.

- Tselebis, A.; Pachi, A. Primary Mental Health Care in a New Era. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, A., & Ghosh, T. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic and stress: coping with the new normal. Journal of Prevention and Health Promotion, 3(1), 30-52.

- ittzen-Brown C, Dolan H, Norton A, Bethel C, May J, Rainbow J. Unbearable suffering while working as a nurse during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative descriptive study. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2023 Dec;5:100127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2023.100127. Epub 2023 Apr 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahroum, N., Seida, I., Esirgün, S. N., & Bragazzi, N. L. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic–How many times were we warned before? European Journal of Internal Medicine, 105, 8-14.

- Cohen, J., & van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. (2020). Contributing factors to personal protective equipment shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Preventive medicine, 141, 106263.

- World Health Organization, 2. (2020). Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages: interim guidance, 6 April 2020 (No. WHO/2019-nCov/IPC_PPE_use/2020.3). World Health Organization.

- Sen-Crowe, B., Sutherland, M., McKenney, M., & Elkbuli, A. (2021). A closer look into global hospital beds capacity and resource shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Surgical Research, 260, 56-63.

- McCabe, R., Schmit, N., Christen, P., D’Aeth, J. C., Løchen, A., Rizmie, D., … & Hauck, K. (2020). Adapting hospital capacity to meet changing demands during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC medicine, 18, 1-12.

- Khubchandani, J.; Bustos, E.; Chowdhury, S.; Biswas, N.; Keller, T. COVID-19 Vaccine Refusal among Nurses Worldwide: Review of Trends and Predictors. Vaccines 2022, 10, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferland, L.; Carvalho, C.; Dias, J.G.; Lamb, F.; Adlhoch, C.; Suetens, C.; Beauté, J.; Kinross, P.; Plachouras, D.; Hannila-Handelberg, T.; et al. Risk of hospitalization and death for healthcare workers with COVID-19 in nine European countries, January 2020–January 2021. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roozenbeek, J., Schneider, C. R., Dryhurst, S., Kerr, J., Freeman, A. L., Recchia, G., … & Van Der Linden, S. (2020). Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. Royal Society open science, 7(10), 201199.

- Milionis, C.; Ilias, I.; Tselebis, A.; Pachi, A. Psychological and Social Aspects of Vaccination Hesitancy—Implications for Travel Medicine in the Aftermath of the COVID-19 Crisis: A Narrative Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couarraze S, Delamarre L, Marhar F, Quach B, Jiao J, Avilés Dorlhiac R, Saadaoui F, Liu AS, Dubuis B, Antunes S, Andant N, Pereira B, Ugbolue UC, Baker JS; COVISTRESS network; Clinchamps M, Dutheil F. The major worldwide stress of healthcare professionals during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic - the international COVISTRESS survey. PLoS One. 2021 Oct 6;16(10):e0257840. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, H., Liu, Y., Hu, K., Zhang, M., Du, M., Huang, H., & Yue, X. (2020). Healthcare workers’ stress when caring for COVID-19 patients: An altruistic perspective. Nurs Ethics. 2020 Nov;27(7):1490-1500. Epub 2020 Jul 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikaras C, Ilias I, Tselebis A, Pachi A, Zyga S, Tsironi M, Gil APR, Panagiotou A. Nursing staff fatigue and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. AIMS Public Health. 2021 Nov 23;9(1):94-105. [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S., Ntella, V., Giannakas, T., Giannakoulis, V. G., Papoutsi, E., & Katsaounou, P. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 88, 901-907.

- Tselebis A, Lekka D, Sikaras C, Tsomaka E, Tassopoulos A, Ilias I, Bratis D, Pachi A. Insomnia, Perceived Stress, and Family Support among Nursing Staff during the Pandemic Crisis. Healthcare. 2020; 8(4):434. [CrossRef]

- Pachi, A., Tselebis, A., Sikaras, C., Sideri, E. P., Ivanidou, M., Baras, S., … & Ilias, I. (2024). Nightmare distress, insomnia and resilience of nursing staff in the post-pandemic era. AIMS Public Health, 11(1), 36-57.

- Tucker, M. A. (2020). The value of sleep for optimizing health. Nutrition, Fitness, and Mindfulness: An Evidence-Based Guide for Clinicians, 203-215.

- Chaput, J.-P.; McNeil, J.; Després, J.-P.; Bouchard, C.; Tremblay, A. Seven to Eight Hours of Sleep a Night Is Associated with a Lower Prevalence of the Metabolic Syndrome and Reduced Overall Cardiometabolic Risk in Adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, S., Herrick, J. E., Collins, J. P., Aldhahi, M., & Baattaiah, B. (2017). Physical functioning and risk for sleep disorders in US adults: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2014. Public Health, 152, 123-128.

- Berk, M. Sleep and depression—theory and practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2009;38: 302–304. [PubMed]

- Faulkner, S., & Bee, P. (2016). Perspectives on sleep, sleep problems, and their treatment, in people with serious mental illnesses: a systematic review. PLoS One, 11(9), e0163486.

- Pachi A, Anagnostopoulou M, Antoniou A, Papageorgiou SM, Tsomaka E, Sikaras C, Ilias I, Tselebis A. Family support, anger and aggression in health workers during the first wave of the pandemic. AIMS Public Health. 2023 Jun 15;10(3):524-537. [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. Anger as a Basic Emotion and Its Role in Personality Building and Pathological Growth: The Neuroscientific, Developmental and Clinical Perspectives. Front Psychol. 2017 Nov 7;8:1950. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition & emotion, 6(3-4), 169-200.

- Ekman, P. (1999). Basic emotions. Handbook of cognition and emotion, 98(45-60), 16.

- Berkowitz, L., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2004). Toward an understanding of the determinants of anger. Emotion, 4(2), 107–130. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Moore GA, Beekman C, Pérez-Edgar KE, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Ganiban JM, Natsuaki MN, Reiss D, Neiderhiser JM. Developmental patterns of anger from infancy to middle childhood predict problem behaviors at age 8. Dev Psychol. 2018 Nov;54(11):2090-2100. Epub 2018 Sep 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Izard, C. E., Fantauzzo, C. A., Castle, J. M., Haynes, O. M., Rayias, M. F., & Putnam, P. H. (1995). The ontogeny and significance of infants’ facial expressions in the first 9 months of life. Developmental psychology, 31(6), 997 –1013.

- Lewis, M., Ramsay, D. S., & Sullivan, M. W. (2006). The relation of ANS and HPA activation to infant anger and sadness response to goal blockage. Developmental Psychobiology: The Journal of the International Society for Developmental Psychobiology, 48(5), 397-405.

- Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., & Chung, J. (2010). The expression of anger across cultures. In M. Potegal, G. Stemmler, & C. Spielberger (Eds.), International handbook of anger: Constituent and concomitant biological, psychological, and social processes (pp. 125–137). Springer Science + Business Media. [CrossRef]

- Söğütlü, Y., Söğütlü, L., & Göktaş, S. Ş. (2021). Relationship of COVID-19 pandemic with anxiety, anger, sleep and emotion regulation in healthcare professionals. Journal of Contemporary Medicine, 11(1), 41-49.

- Shin, C., Kim, J., Yi, H., Lee, H., Lee, J., & Shin, K. (2005). Relationship between trait-anger and sleep disturbances in middle-aged men and women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58(2), 183-189.

- Sisman, F. N., Basakci, D., & Ergun, A. (2021). The relationship between insomnia and trait anger and anger expression among adolescents. Journal of child and adolescent psychiatric nursing, 34(1), 50-56.

- Sevgi Aldemir & Gülay Taşdemır Yiğitoğlu. The Relation Between Sleep Quality and Anger Expression That Occur in Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Radiology Nursing 43 (2024) 60-67.

- Kahn M, Sheppes G, Sadeh A. Sleep and emotions: bidirectional links and underlying mechanisms. Int J Psychophysiol. 2013 Aug;89(2):218-28. Epub 2013 May 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Brink M, Dietch JR, Tutek J, Suh SA, Gross JJ, Manber R. Sleep and affect: A conceptual review. Sleep Med Rev. 2022 Oct;65:101670. Epub 2022 Aug 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Z Krizan, A Miller, G Hisler, 0276 Does Losing Sleep Unleash Anger?, Sleep, Volume 43, Issue Supplement_1, April 2020, Page A105. [CrossRef]

- Saghir Z, Syeda JN, Muhammad AS, Balla Abdalla TH. The Amygdala, Sleep Debt, Sleep Deprivation, and the Emotion of Anger: A Possible Connection? Cureus. 2018 Jul 2;10(7):e2912. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jichul Kim, Chang Woo Lee, Sehyun Jeon, Bum Joon Seok, and Seog Ju Kim. Anger Associated with Insomnia and Recent Stressful Life Events in Community-Dwelling Adults. Chronobiol Med 2019;1(4):163-167.

- Miles SR, Pruiksma KE, Slavish D, Dietch JR, Wardle-Pinkston S, Litz BT, Rodgers M, Nicholson KL, Young-McCaughan S, Dondanville KA, Nakase-Richardson R, Mintz J, Keane TM, Peterson AL, Resick PA, Taylor DJ; Consortium to Alleviate PTSD. Sleep disorder symptoms are associated with greater posttraumatic stress and anger symptoms in US Army service members seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022 Jun 1;18(6):1617-1627. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hisler, G., & Krizan, Z. (2017). Anger tendencies and sleep: Poor anger control is associated with objectively measured sleep disruption. Journal of Research in Personality, 71, 17–26. [CrossRef]

- Krizan Z, Hisler G. Sleepy anger: Restricted sleep amplifies angry feelings. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2019 Jul;148(7):1239-1250. Epub 2018 Oct 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise J (2023) Covid-19: WHO declares end of global health emergency. BMJ 2023;381:p1041. [CrossRef]

- Harris E (2023) WHO declares end of COVID-19 global health emergency. JAMA 329: 1817. [CrossRef]

- Preti E, Di Mattei V, Perego G, et al. The Psychological Impact of Epidemic and Pandemic Outbreaks on Healthcare Workers: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22:43.

- Tselebis A, Sikaras C, Milionis C, Sideri EP, Fytsilis K, Papageorgiou SM, Ilias I, Pachi A. A Moderated Mediation Model of the Influence of Cynical Distrust, Medical Distrust, and Anger on Vaccination Hesitancy in Nursing Staff. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2023; 13(11):2373-2387. [CrossRef]

- Soldatos, C.R.; Dikeos, D.G.; Paparrigopoulos, T.J. Athens Insomnia Scale: Validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J. Psychosom. Res. 2000, 48, 555–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatos, C.R.; Dikeos, D.G.; Paparrigopoulos, T.J. The diagnostic validity of the Athens Insomnia Scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 55, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriou, A., Rokou, A., Arvaniti, A., Nena, E., & Steiropoulos, P. (2021). Sleep quality and mental health of medical students in Greece during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in public health, 9, 775374.

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, J.H.; Kang, S.-E. Validation of the Dimensions of Anger Reactions Scale (the DAR-5) in non-clinical South Korean adults. BMC Psychol 11, 74 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Forbes, D.; Alkemade, N.; Hopcraft, D.; Hawthorne, G.; O’halloran, P.; Elhai, J.D.; McHugh, T.; Bates, G.; Novaco, R.W.; Bryant, R.; et al. Evaluation of the Dimensions of Anger Reactions-5 (DAR-5) Scale in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. International journal of behavioral medicine, 15, 194-200.

- Kyriazos TA, Stalikas A, Prassa K, et al. (2018) Psychometric evidence of the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) and modeling distinctiveness of resilience from depression and stress. Psychology 9: 1828-1857.

- Pachi, A.; Kavourgia, E.; Bratis, D.; Fytsilis, K.; Papageorgiou, S.M.; Lekka, D.; Sikaras, C.; Tselebis, A. Anger and Aggression in Relation to Psychological Resilience and Alcohol Abuse among Health Professionals during the First Pandemic Wave. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziallas D, Goutzias E, Konstantinidou E, et al. Quantitative and qualitative assessment of nurse staffing indicators across NHS public hospitals in Greece. Hell J Nurs. 2018;57:420–449.

- Hayes A F, Rockwood N J (2020) Conditional process analysis: Concepts, computation, and advances in the modeling of the contingencies of mechanisms. Am Behav Sci 64: 19-54. [CrossRef]

- Hayes AF (2015) An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behav Res 50: 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Sikaras, C., Tsironi, M., Zyga, S., & Panagiotou, A. (2023). Anxiety, insomnia and family support in nurses, two years after the onset of the pandemic crisis. AIMS Public Health, 10(2), 252.

- Cheung, T., & Yip, P. S. (2015). Depression, anxiety and symptoms of stress among Hong Kong nurses: a cross-sectional study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 12(9), 11072-11100.

- Tselebis, A., Gournas, G., Tzitzanidou, G., Panagiotou, A., & Ilias, I. (2006). Anxiety and depression in Greek nursing and medical personnel. Psychological Reports, 99(1), 93-96.

- Shen, Y., Zhan, Y., Zheng, H., Liu, H., Wan, Y., & Zhou, W. (2021). Anxiety and its association with perceived stress and insomnia among nurses fighting against COVID-19 in Wuhan: a cross-sectional survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30(17-18), 2654-2664.

- Lu, M. Y., Ahorsu, D. K., Kukreti, S., Strong, C., Lin, Y. H., Kuo, Y. J., … & Ko, W. C. (2021). The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, sleep problems, and psychological distress among COVID-19 frontline healthcare workers in Taiwan. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 705657.

- McLay RN, Klam WP, Volkert SL. Insomnia is the most commonly reported symptom and predicts other symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in U.S. service members returning from military deployments. Mil Med. 2010 Oct;175(10):759-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox CL. ‘Healthcare Heroes’: problems with media focus on heroism from healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Ethics Aug. 2020;46:510–513. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, N., Zhang, L., Gong, M., & Geng, F. (2024). Clinical correlates of irritability, anger, hostility, and aggression in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 16(6), 1055–1062. [CrossRef]

- McFall ME, Wright PW, Donovan DM, Raskind M. Multidimensional assessment of anger in Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1999 May-Jun;40(3):216-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, D. Forbes, D., Metcalf, O., Lawrence-Wood, E. et al. Problematic Anger in the Military: Focusing on the Forgotten Emotion. Curr Psychiatry Rep 24, 789–797 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Sills L, Kautz JD, Choi KW, et al. Effects of prior deployments and perceived resilience on anger trajectories of combat-deployed soldiers. Psychological Medicine. 2023;53(5):2031-2040. [CrossRef]

- Marey-Sarwan I, Hamama-Raz Y, Asadi A, Nakad B, Hamama L. “It’s like we’re at war”: Nurses’ resilience and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Inq. 2022 Jul;29(3):e12472. doi: 10.1111/nin.12472. Epub 2021 Nov 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manchia M, Gathier AW, Yapici-Eser H, Schmidt MV, de Quervain D, van Amelsvoort T, Bisson JI, Cryan JF, Howes OD, Pinto L, van der Wee NJ, Domschke K, Branchi I, Vinkers CH. The impact of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic on stress resilience and mental health: A critical review across waves. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022 Feb;55:22-83. Epub 2021 Oct 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolotira EA. Trauma, Compassion Fatigue, and Burnout in Nurses: The Nurse Leader’s Response. Nurse Lead. 2023 Apr;21(2):202-206. Epub 2022 May 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smid, G. E., Kleber, R. J., Rademaker, A. R., van Zuiden, M., & Vermetten, E. (2013). The role of stress sensitization in progression of posttraumatic distress following deployment. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(11), 1743–1754. [CrossRef]

- Russo JE, Dhruve DM, Oliveros AD. Coping with COVID-19: Testing the stress sensitization hypothesis among adults with and without a history of adverse childhood experiences. J Affect Disord Rep. 2022 Dec;10:100379. Epub 2022 Jul 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, A. B., Brossart, D. F., & Toblin, R. L. (2017). Can anger be helpful?: Soldier perceptions of the utility of anger. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 205(9), 692–698. [CrossRef]

- Lee HY, Jang MH, Jeong YM, Sok SR, Kim AS. Mediating Effects of Anger Expression in the Relationship of Work Stress with Burnout among Hospital Nurses Depending on Career Experience. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2021 Mar;53(2):227-236. Epub 2021 Feb 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La IS, Yun EK. Effects of Trait Anger and Anger Expression on Job Satisfaction and Burnout in Preceptor Nurses and Newly Graduated Nurses: A Dyadic Analysis. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2019 Oct;13(4):242-248. Epub 2019 Sep 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkowski BM, Robinson MD. The anatomy of anger: an integrative cognitive model of trait anger and reactive aggression. J Pers. 2010 Feb;78(1):9-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palagini L, Moretto U, Dell’Osso L, Carney C, Sleep-related cognitive processes, arousal, and emotion dysregulation in insomnia disorder: the role of insomnia-specific rumination, Sleep Medicine, Volume 30, 2017, Pages 97-104, ISSN 1389-9457. [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach DA, Buysse DJ, Cheng P, Roth T, Yang A, Drake CL. Nocturnal cognitive arousal is associated with objective sleep disturbance and indicators of physiologic hyperarousal in good sleepers and individuals with insomnia disorder. Sleep Med. 2020 Jul;71:151-160. Epub 2019 Nov 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandekerckhove M, Weiss R, Schotte C, Exadaktylos V, Haex B, Verbraecken J, Cluydts R. The role of presleep negative emotion in sleep physiology. Psychophysiology. 2011 Dec;48(12):1738-44. Epub 2011 Sep 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norell-Clarke A, Hagström M and Jansson-Fröjmark M (2021) Sleep-Related Cognitive Processes and the Incidence of Insomnia Over Time: Does Anxiety and Depression Impact the Relationship? Front. Psychol. 12:677538. [CrossRef]

- Ham EM, You MJ. Role of Irrational Beliefs and Anger Rumination on Nurses’ Anger Expression Styles. Workplace Health Saf. 2018 May;66(5):223-232. Epub 2017 Nov 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalf O, Little J, Cowlishaw S, Varker T, Arjmand HA, O’Donnell M, Phelps A, Hinton M, Bryant R, Hopwood M, McFarlane A, Forbes D. Modelling the relationship between poor sleep and problem anger in veterans: A dynamic structural equation modelling approach. J Psychosom Res. 2021 Nov;150:110615. Epub 2021 Sep 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hruska B, Anderson L, Barduhn MS. Multilevel analysis of sleep quality and anger in emergency medical service workers. Sleep Health. 2022 Jun;8(3):303-310. Epub 2022 Apr 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizan, Z., & Herlache, A. D. (2016). Sleep disruption and aggression: Implications for violence and its prevention. Psychology of Violence, 6, 542-552.

- Kamphuis, J., Meerlo, P., Koolhaas, J. M., & Lancel, M. (2012). Poor sleep as a potential causal factor in aggression and violence. Sleep Medicine, 13, 327-334.

- Dressle RJ, Riemann D. Hyperarousal in insomnia disorder: Current evidence and potential mechanisms. J Sleep Res. 2023 Dec;32(6):e13928. Epub 2023 May 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tselebis A, Zoumakis E, Ilias I. Dream Recall/Affect and the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis. Clocks & Sleep. 2021; 3(3):403-408.

- Kalmbach DA, Cuamatzi-Castelan AS, Tonnu CV, Tran KM, Anderson JR, Roth T, Drake CL. Hyperarousal and sleep reactivity in insomnia: current insights. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018 Jul 17;10:193-201. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altena E, Chen IY, Daviaux Y, Ivers H, Philip P, Morin CM. How Hyperarousal and Sleep Reactivity Are Represented in Different Adult Age Groups: Results from a Large Cohort Study on Insomnia. Brain Sci. 2017 Apr 14;7(4):41. 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hailey Meaklim, Flora Le, Sean P A Drummond, Sukhjit K Bains, Prerna Varma, Moira F Junge, Melinda L Jackson, Insomnia is more likely to persist than remit after a time of stress and uncertainty: a longitudinal cohort study examining trajectories and predictors of insomnia symptoms, Sleep, Volume 47, Issue 4, April 2024, zsae028. [CrossRef]

- Demichelis OP, Grainger SA, Burr L, Henry JD. Emotion regulation mediates the effects of sleep on stress and aggression. J Sleep Res. 2023 Jun;32(3):e13787. Epub 2022 Nov 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson J, Bjureberg J, Zhao X, Hesser H. The inner workings of anger: A network analysis of anger and emotion regulation. J Clin Psychol. 2024 Feb;80(2):437-455. Epub 2023 Nov 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reffi AN, Kalmbach DA, Cheng P, Drake CL. The sleep response to stress: how sleep reactivity can help us prevent insomnia and promote resilience to trauma. J Sleep Res. 2023 Dec;32(6):e13892. Epub 2023 Apr 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassing R, Benjamins JS, Dekker K, Moens S, Spiegelhalder K, Feige B, Riemann D, van der Sluis S, Van Der Werf YD, Talamini LM, Walker MP, Schalkwijk F, Van Someren EJ. Slow dissolving of emotional distress contributes to hyperarousal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016 Mar 1;113(9):2538-43. Epub 2016 Feb 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Gu S, Wang Z, Li H, Xu X, Zhu H, Deng S, Ma X, Feng G, Wang F, Huang JH. Relationship Between Stressful Life Events and Sleep Quality: Rumination as a Mediator and Resilience as a Moderator. Front Psychiatry. 2019 May 27;10:348. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Martire, V., Berteotti, C., Zoccoli, G. et al. Improving Sleep to Improve Stress Resilience. Curr Sleep Medicine Rep 10, 23–33 (2024). [CrossRef]

- L Palagini, B Olivia, E Petri, G Cipollone, U Moretto, G Perugi, 0294 Resilience, Emotion and Arousal Regulation in Insomnia Disorder, Sleep, Volume 40, Issue suppl_1, 28 April 2017, Pages A108–A109. [CrossRef]

- Palagini L, Moretto U, Novi M, Masci I, Caruso D, Drake CL, Riemann D. Lack of resilience is related to stress-related sleep reactivity, hyperarousal, and emotion dysregulation in insomnia disorder. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(5):759–766.

- Zhan N, Xu Y, Pu J, Wang W, Xie Zand Huang H (2024). The interaction between mental resilience and insomnia disorder on negative emotions in nurses in Guangdong Province, China. Front. Psychiatry 15:1396417. [CrossRef]

- Basta M, Chrousos GP, Vela-Bueno A, Vgontzas AN. CHRONIC INSOMNIA AND STRESS SYSTEM. Sleep Med Clin. 2007 Jun;2(2):279-291. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng-Yin Cheng, Meng-Jia Wang, Ming-Yu Chang, Rui-Xing Zhang, Chao-Fan Gu & Yu-Hua Zhao (2020): Relationship between resilience and insomnia among the middleaged and elderly: mediating role of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, Psychology, Health & Medicine. [CrossRef]

- de Almondes KM, Marín Agudelo HA, Jiménez-Correa U. Impact of Sleep Deprivation on Emotional Regulation and the Immune System of Healthcare Workers as a Risk Factor for COVID 19: Practical Recommendations From a Task Force of the Latin American Association of Sleep Psychology. Front Psychol. 2021 May 20;12:564227. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir G, Karadag G. The Relationship Between Nurses’ Sleep Quality and Their Tendency to Commit Medical Errors. Sleep Sci. 2023 Nov 30;17(1):e7-e15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng P, Kalmbach DA, Hsieh H-F, Castelan AC, Sagong C, Drake CL. Improved resilience following digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia protects against insomnia and depression one year later. Psychological Medicine. 2023;53(9):3826-3836. [CrossRef]

- Philip Cheng, Melynda D Casement, David A Kalmbach, Andrea Cuamatzi Castelan, Christopher L Drake, Digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia promotes later health resilience during the coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic, Sleep, Volume 44, Issue 4, April 2021, zsaa258. [CrossRef]

- Landry CA, McCall HC, Beahm JD, Titov N, Dear B, Carleton RN, Hadjistavropoulos HD. Web-Based Mindfulness Meditation as an Adjunct to Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Public Safety Personnel: Mixed Methods Feasibility Evaluation Study. JMIR Form Res. 2024 Jan 30;8:e54132. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen B, Preisman M, Read H, Chaukos D, Greenberg RA, Jeffs L, Maunder R, Wiesenfeld L. Resilience coaching for healthcare workers: Experiences of receiving collegial support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2022 Mar-Apr;75:83-87. Epub 2022 Feb 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C. Y., Chen, H. C., Tseng, M. C. M., Lee, H. C., & Huang, L. H. (2015). The relationships among sleep quality and chronotype, emotional disturbance, and insomnia vulnerability in shift nurses. Journal of Nursing Research, 23(3), 225-235.

- Chan, M. F. (2009). Factors associated with perceived sleep quality of nurses working on rotating shifts. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(2), 285-293.

- Pachi A, Tselebis A, Ilias I, Tsomaka E, Papageorgiou SM, Baras S, Kavouria E, Giotakis K. Aggression, Alexithymia and Sense of Coherence in a Sample of Schizophrenic Outpatients. Healthcare. 2022; 10(6):1078. [CrossRef]

- Tselebis, A.; Bratis, D.; Pachi, A.; Moussas, G.; Karkanias, A.; Harikiopoulou, M.; Theodorakopoulou, E.; Kosmas, E.; Ilias, I.; Siafakas, N.; et al. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Sense of Coherence and Family Support Versus Anxiety and Depression. Psychiatriki 2013, 24, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jarrin, D. C., Chen, I. Y., Ivers, H., & Morin, C. M. (2014). The role of vulnerability in stress-related insomnia, social support and coping styles on incidence and persistence of insomnia. Journal of sleep research, 23(6), 681-688.

- Tselebis, A., Anagnostopoulou, T., Bratis, D., Moulou, A., Maria, A., Sikaras, C., … & Tzanakis, N. (2011). The 13 item Family Support Scale: Reliability and validity of the Greek translation in a sample of Greek health care professionals. Asia Pacific family medicine, 10, 1-4.

- Ellison, C. G., Deangelis, R. T., Hill, T. D., & Froese, P. (2019). Sleep quality and the stress-buffering role of religious involvement: a mediated moderation analysis. Journal for the scientific study of religion, 58(1), 251-268.

| Age | Work Experience (in Years) | Dimensions of Anger Reactions-5 (DAR-5) |

Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) |

Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Mean | 46.620* | 20.063 | 9.848** | 6.051** | 3.599* |

| N | 79 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 79 | |

| Std. Deviation | 10.564 | 11.613 | 3.146 | 3.958 | 0.779 | |

| Female | Mean | 43.149* | 17.845 | 11.541** | 7.602** | 3.357* |

| N | 362 | 362 | 362 | 362 | 362 | |

| Std. Deviation | 10.838 | 11.916 | 3.923 | 4.139 | 0.776 | |

| Hedges’ g | 0.322 | 0.446 | 0.378 | 0.312 | ||

| Total | Mean | 43.771 | 18.243 | 11.238 | 7.324 | 3.400 |

| N | 441 | 441 | 441 | 441 | 441 | |

| Std. Deviation | 10.859 | 11.880 | 3.848 | 4.146 | 0.781 | |

| Age | Work Experience (in Years) | AIS | DAR-5 | ||

|

Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) |

r | -0.105* | -0.077 | ||

| p | 0.028 | 0.108 | |||

| N | 441 | 441 | |||

| Dimensions of Anger Reactions-5 (DAR-5) | r | -0.056 | -0.040 | 0.485** | |

| p | 0.238 | 0.406 | 0.001 | ||

| N | 441 | 441 | 441 | ||

| The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) | r | 0.217** | 0.185** | -0.418** | -0.405** |

| p | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| N | 441 | 441 | 441 | 441 | |

| Dependent Variable: Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) |

R Square | R Square Change | Beta | t | p | VIF | Durbin- Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions of Anger Reactions (DAR-5) |

0.235 | 0.235 | 0.378 | 8.609 | 0.001* | 1.197 | 1.937 |

| Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) | 0.294 | 0.058 | −0.264 | −6.019 | 0.001* | 1.197 |

| Variables | b | SE | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

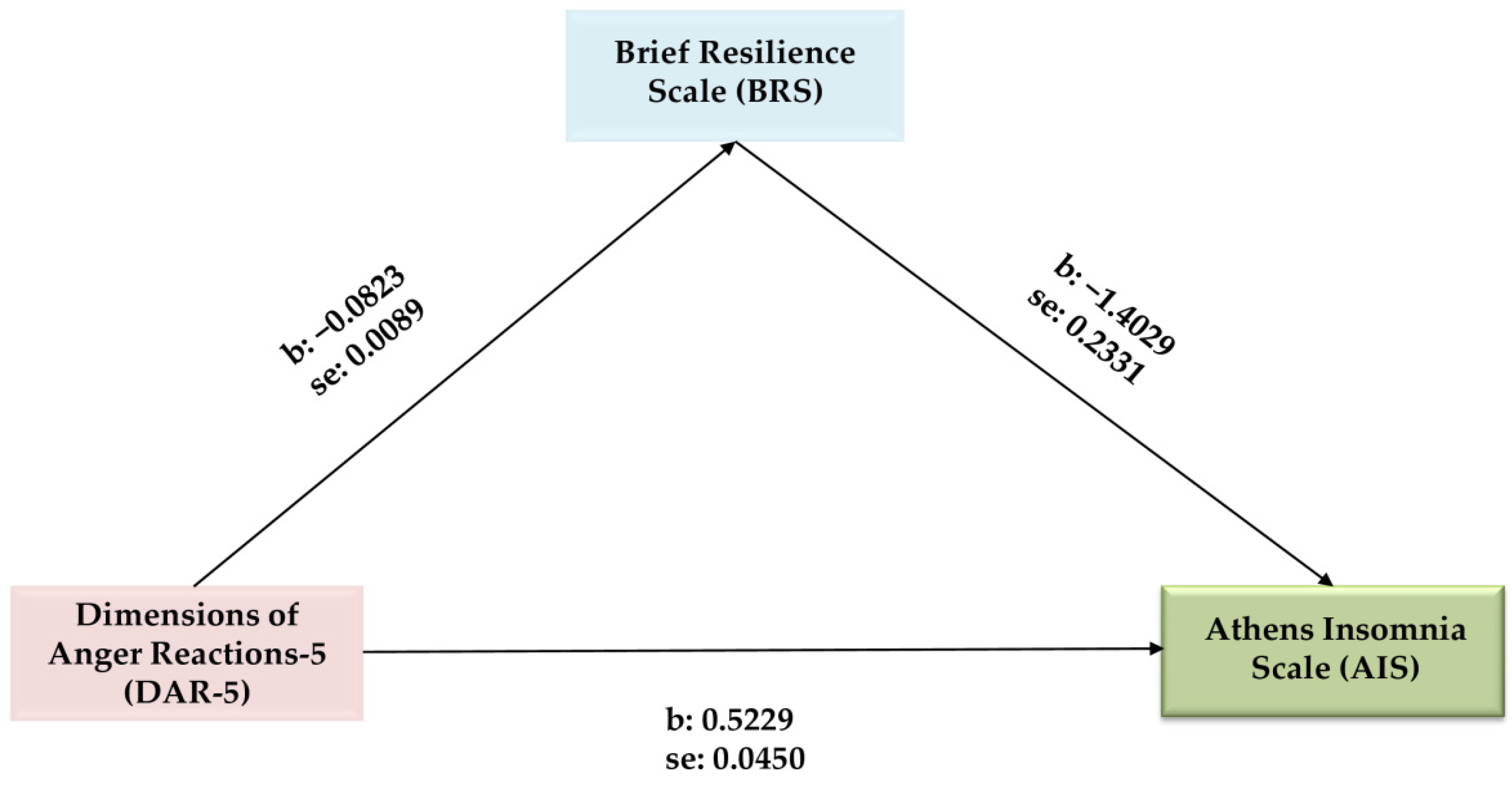

| DAR-5 → BRS | −0.0823 | 0.0089 | −9.2896 | 0.001 | −0. 0997 | −0.0649 |

| DAR-5 → AIS | 0.5229 | 0.0450 | 11.6283 | 0.001 | 0.4345 | 0.6112 |

| DAR-5 → BRS → AIS | −1.4029 | 0.2331 | −6.0185 | 0.001 | −1.8610 | −0.9448 |

| Effects | ||||||

| Direct | 0.4074 | 0.0473 | 8.6092 | 0.001 | 0.3144 | 0.5004 |

| Indirect * | 0.1154 | 0.0244 | 0.0712 | 0.1669 | ||

| Total | 0.5229 | 0.0450 | 11.6283 | 0.001 | 0.4345 | 0.6112 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).